Abstract

The discovery of van der Waals intrinsic magnets has expanded the possibilities of realizing spintronics devices. We investigate the transmission, tunneling magnetoresistance ratio, and spin injection efficiency of bilayer LaI2 using a combination of first-principles calculations and the non-equilibrium Green’s function method. Multilayer graphene electrodes are employed to build a magnetic tunnel junction with bilayer LaI2 as ferromagnetic barrier. The magnetic tunnel junction turns out to be a perfect spin filter device with an outstanding tunneling magnetoresistance ratio of 653% under a bias of 0.1 V and a still excellent performance in a wide bias range. In combination with the obtained high spin injection efficiency this opens up great potential from the application point of view.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs)1,2 can be utilized in read heads3, sensors4, and nonvolatile magnetic random-access memories5, for example. A conventional MTJ consists of two ferromagnetic metallic electrodes separated by a thin insulating barrier6,7. There exist also alternative arrangements, using ferroelectric insulating barriers8, ferromagnetic insulating barriers9, and antiferromagnetic metallic electrodes10,11. Experimental and theoretical studies have applied Al2O312,13,14 and MgO15,16,17,18 as barriers, achieving tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR) ratios of up to 90% and 180%, respectively. However, these devices suffer from pinholes, defects, non-uniform thickness, and trapped charges, issues that can be resolved by using van der Waals materials19,20. For example, monolayer MoS2 as barrier with NiFe electrodes achieves a TMR ratio of 9%21, bilayer hexagonal boron nitride as barrier with Ni electrodes achieves a TMR ratio of 75%22, and a composite of graphene and monolayer MoS2 as barrier with Co electrodes achieves a TMR ratio of 1270%23. Composites of graphene and hexagonal boron nitride have been used as barriers with different electrodes, providing TMR ratios of up to 149%24.

The emergence of van der Waals intrinsic magnets25,26,27,28 has opened up an exciting avenue beyond the conventional MTJ design29,30. CrI3 in bilayer31 and multilayer32,33 form is one of the most studied van der Waals intrinsic magnets and is extensively used as spin filter material though it has several issues. Particularly, a large magnetic field of 0.65 T is required to switch the interlayer spin alignment between antiparallel (AP) and parallel (P)34. Bilayer CrCl3 and bilayer CoBr2 as barrier with graphene electrodes achieve TMR ratios of 35%35 and 2420%36, respectively. A composite of CrBr3 and hexagonal boron nitride as barrier with Au electrodes achieves a TMR ratio of 1328%37 and FeCl2 as barrier with MoS2 electrodes achieves a TMR ratio of 6300%38.

Ferrovalley materials, a class of van der Waals intrinsic magnets, are used in information processing and storage39. Various studies have demonstrated a large TMR ratio for MTJs based on ferrovalley materials. For example, the VSe2/MoS2/VSe2 MTJ achieves a TMR ratio of 846% at a bias of 0.5 V40 and the VSi2N4/MoSi2N4/VSi2N4 MTJ achieves a TMR ratio of 1000% at a bias of 0.1 V41. Recently, ferrovalley materials based on rare-earth elements have been discovered42. To assess their applicability in MTJs, we study in this work the van der Waals MTJ formed by bilayer LaI243 as ferromagnetic barrier sandwiched between multilayer graphene as metallic electrodes31,35,44. The emergence of outstanding TMR ratios in the vicinity of the Fermi energy results in great potential of ferrovalley materials based on rare-earth elements in MTJs.

Results

First-principles and quantum transport calculations

Spin-polarized first-principles calculations using density functional theory within the generalized gradient approximation of Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof for the exchange-correlation functional are performed using the SIESTA code45. The density matrix is converged to an accuracy of 10−5 and the structure is optimized until the Hellmann-Feynman forces stay below 0.01 eV/Å. A 700 Ry energy cutoff is used for the double-ζ polarized basis set and the Brillouin zone is sampled on a Monkhorst-Pack 17 × 17 × 1 k-mesh. Periodic boundary conditions are applied with a 15 Å vacuum slab to create a two-dimensional model.

Quantum transport calculations are performed in the framework of the non-equilibrium Green’s function method implemented in the TranSIESTA code based on the non-equilibrium density matrix46,47. The specific crystal structures are considered for both the semi-infinite electrodes (employing a Monkhorst-Pack 8 × 8 × 100 k-mesh) and scattering region (employing a Monkhorst-Pack 8 × 8 × 1 k-mesh). The spin-dependent transmission function of electrons with energy E subject to a bias V between the electrodes is calculated as48

where Gσ(E, V) is the retarded Green’s function of the scattering region, \({\Sigma }_{L/R}^{\sigma }(E,V)\) is the self-energy of the left/right (L/R) electrode, and σ = ↑/↓ is the spin majority/minority channel. Moreover,

where \({G}_{L/R}^{\sigma }(E,V)\) is the surface Green’s function of the electrode and τL/R is the coupling between scattering region and electrode. The spin-dependent current is given by48

where f is the Fermi-Dirac distribution function, EF is the Fermi energy, and e is the elementary charge. The k-resolved transmission function is extracted using the SISL utility49. The TMR ratio at zero bias is calculated as

and the TMR ratio under bias is calculated as

where \({I}_{P/AP}^{\sigma }\) is the spin-dependent current.

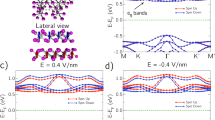

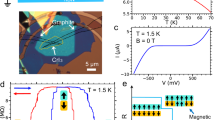

According to Fig. 1, monolayer LaI2 is found to be intrinsically ferromagnetic (magnetic moment of 1 μB per formula unit) with a bandgap of 0.1 eV, consistent with Ref. 43. The valence and conduction band edges are dominated by the spin majority and minority La states, respectively. Figure 2a, b shows a schematic representation of the two-terminal device with bilayer LaI2 sandwiched between multilayer graphene. Multilayer graphene is adopted as electrode material, as standard electrode materials suffer from large lattice mismatch with bilayer LaI2. We find that the multilayer graphene electrodes do not develop spin polarization (C magnetic moments < 0.001 μB). AB-stacked bilayer LaI2 is found to be energetically favorable over AA-stacked bilayer LaI2 by 88 meV per formula unit and therefore is adopted for the barrier. While without bias applied to the two-terminal device the P interlayer spin alignment in bilayer LaI2 is energetically favorable over the AP interlayer spin alignment by 3 meV, the AP interlayer spin alignment quickly becomes favorable under bias (for example, by 38, 14, 4, and 52 meV under biases of −0.01, −0.005, 0.005, and 0.01 V, respectively). Therefore, the interlayer spin alignment can be switched between the AP and P configurations by an external magnetic field, following the working principle of CrCl335 and CrI331 MTJs. The lattice constant of bilayer LaI2 matches with that of a 0.3% compressed \(\sqrt{3}\times \sqrt{3}\times 1\) supercell of graphene. The two-terminal device is periodic in the y direction, while the transport is in the z direction. The optimized interface distance between bilayer LaI2 and multilayer graphene is obtained as 3.53 Å, demonstrating weak coupling and indicating that the transport properties of the MTJ depend mainly on the interface geometry between the constituents. The differential charge density plot in Fig. 2c reveals a minor charge redistribution at the interface (black arrows).

a Side and b top views of the two-terminal device with bilayer LaI2 barrier and multilayer graphene electrodes. Red arrows indicate the spin alignment (AP configuration) and grey color marks the electrodes. c Differential charge density in the two-terminal device (without electrodes). Brown, purple, and green spheres represent the C, I, and La atoms, respectively. Orange and cyan isosurfaces represent accumulation and depletion of electrons, respectively (isosurface value = 0.0002 e/Å3).

We plot the spin-resolved transmission spectra of the AP and P configurations at V = 0 V in Fig. 3a, b, respectively. The results for the AP configuration do not differ between the two spin channels in contrast to those for the P configuration. This is due to the fact that in the AP configuration the bilayer LaI2 barrier affects the spin majority and minority electrons equally because of the antiparallel spin alignment of the two LaI2 layers, while in the P configuration they are not affected equally because of the parallel spin alignment of the two LaI2 layers, resulting in spin filtering. The TMR ratio at EF, see Fig. 3c, is found to be 94%, similar to the values achieved by the 1T-VSe2/1H-VSe2/1T-VSe2 (484%) and 1T-VSe2/1H-MoS2/1T-VSe2 (22%) MTJs (both based on ferrovalley materials)40. Interestingly, at EF − 0.03 eV the much higher spin majority transmission in the P configuration as compared to the AP configuration results in a very high TMR ratio of 350000%.

Figure 4a–d shows for the AP and P configurations, respectively, the k-resolved transmission at EF for V = 0 V within the region of the hexagonal Brillouin zone mark as black square in Fig. 4k. In all other regions the values are negligible, i.e., the transmission is strongly concentrated around the Γ point. Due to the periodicity in the ab-plane, the components of the wave vector in this plane are conserved during tunneling. The transmission distributions reflect the six-fold rotational symmetry of the device. We obtain for the AP configuration similar spin majority and minority transmission distributions, which is consistent with Fig. 3a. In contrast, for the P configuration the spin majority and minority transmission distributions differ strongly. While for the spin majority channel the result is similar to that of the AP configuration, except for the enhanced magnitude, we find for the spin minority channel almost no transmission, consistent with Fig. 3b. The transmission distributions are expected to change significantly at EF − 0.03 eV, as the TMR ratio is very different (pronounced maximum in Fig. 3c). In contrast to Fig. 4a–d, Fig. 4f–i indeed shows relevant transmission only for the P configuration and there only in the spin majority channel. Due to the fact that this transmission is ~104 times that obtained for the AP configuration (in both spin channels), the TMR ratio, according to Eq. (3), reaches unprecedented values. To clarify the role of the electrodes in the transport, we compare the k-resolved transmissions of bilayer graphene at EF and EF − 0.03 eV in Fig. 4e, j. The results resemble the shapes of the transmission distributions of Fig. 4a–d and f–i, respectively, demonstrating that those are determined by the electrodes.

Transmission distribution in the Brillouin zone for the a, b AP and c, d P configurations at EF for V = 0 V (spin-resolved), e bilayer graphene at EF for V = 0 V (non-magnetic), the f, g AP and h, i P configurations at EF − 0.03 eV for V = 0 V, and j bilayer graphene at EF − 0.03 eV for V = 0 V (non-magnetic). k Brillouin zone. The black square in the middle is the region for which the transmission distribution is plotted in displays a–j.

We plot the spin-resolved transmission spectra of the AP and P configurations under bias (V = 0.05 and 0.1 V) in Fig. 5a–d, respectively. While for the AP configuration the results are very similar in the spin majority and minority channels, large differences are observed for the P configuration at most energies, which demonstrates excellent spin filtering. The TMR ratio varies under bias, see Fig. 5e, as EF is shifted. The obtained values are excellent from an application point of view. The TMR ratio of 653% clearly surpasses the value reported for the common Fe/MgO/Fe MTJ (180%)17 and is more than 1.5 times that of the 1T-VSe2/1H-MoS2/1T-VSe2 MTJ (~400%)40 under the same bias of 0.1 eV. For the spin injection efficiency, (I↑ − I↓)/(I↑ + I↓), where I↑ is the spin majority current and I↓ is the spin minority current, we obtain for the P configuration values of 0.99, 0.99, 0.99, 0.98, 0.98, 0.99, 0.99, and 0.99 under biases of −0.2, −0.15, −0.1, −0.05, 0.05, 0.01, 0.15, and 0.2 V, respectively (AP configuration: 0.18, 0.08, 0.02, 0.17, 0.01, 0.09, 0.13, and 0.18), confirming excellent spin selectivity. The origin of this property is the much higher spin majority transmission as compared to the spin minority transmission in the P configuration, see Fig. 3b, which translates into a much higher I↑ than I↓. On the other hand, the spin majority and minority transmissions are similar in the AP configuration, see Fig. 3a, leading to similar currents under bias.

Spin-resolved transmission as a function of energy for the AP configuration at a V = 0.05 V and c V = 0.1 V and for the P configuration at b V = 0.05 V and d V = 0.1 V. e TMR ratio as a function of bias at EF. The black dot at V = 0 V is identical to that in Fig. 3c.

Discussion

First-principles calculations combined with the non-equilibrium Green’s function method are used to study the transport properties of the MTJ formed by bilayer LaI2 as barrier and multilayer graphene as electrodes. Monolayer LaI2 is intrinsically ferromagnetic with a magnetic moment of 1 μB per formula unit. The TMR ratio of the MTJ is found to show a strong energy dependence, which can be explained by the obtained spin-resolved transmission distributions in the Brillouin zone. An outstanding TMR ratio of 653% is found under a bias of 0.1 V and the performance remains excellent in a wide bias range. In addition, the spin injection efficiency turns out to be very high for the P configuration, pointing to excellent potential of the MTJ as spin filter device. Overall, our results call for prompt experimental exploration of MTJs based on rare-earth ferrovalley materials.

Data availability

The data are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Wolf, S. A. et al. Spintronics: A spin-based electronics vision for the future. Science 294, 1488–1495 (2001).

Zhang, L., Zhou, J., Li, H., Shen, L. & Feng, Y. P. Recent progress and challenges in magnetic tunnel junctions with 2D materials for spintronic applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 8, 021308 (2021).

Mao, S. et al. Commercial TMR heads for hard disk drives: Characterization and extendibility at 300 Gbit/in2. IEEE Trans. Magn. 42, 97–102 (2006).

Maciel, N., Marques, E., Naviner, L., Zhou, Y. & Cai, H. Magnetic tunnel junction applications. Sensors 20, 121 (2019).

Grimaldi, E. et al. Single-shot dynamics of spin-orbit torque and spin transfer torque switching in three-terminal magnetic tunnel junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 111–117 (2020).

Gregg, J. F., Petej, I., Jouguelet, E. & Dennis, C. Spin electronics - A review. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 35, R121 (2002).

Zhu, J.-G. J. & Park, C. Magnetic tunnel junctions. Mater. Today 9, 36–45 (2006).

Yang, Q. et al. Ferroelectric tunnel junctions enhanced by a polar oxide barrier layer. Nano Lett. 19, 7385–7393 (2019).

Zhang, X., Yang, B., Guo, X., Han, X. & Yan, Y. Ferromagnetic barrier induced large enhancement of tunneling magnetoresistance in van der Waals perpendicular magnetic tunnel junctions. Nanoscale 13, 19993–20001 (2021).

Shao, D.-F., Zhang, S.-H., Li, M., Eom, C.-B. & Tsymbal, E. Y. Spin-neutral currents for spintronics. Nat. Commun. 12, 7061 (2021).

Qin, P. et al. Room-temperature magnetoresistance in an all-antiferromagnetic tunnel junction. Nature 613, 485–489 (2023).

Miyazaki, T., Yaoi, T. & Ishio, S. Large magnetoresistance effect in 82Ni-Fe/Al-Al2O3/Co magnetic tunneling junction. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 98, L7–L9 (1991).

Moodera, J. S., Kinder, L. R., Wong, T. M. & Meservey, R. Large magnetoresistance at room temperature in ferromagnetic thin film tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 3273–3276 (1995).

Acharya, J., Goul, R. & Wu, J. High tunneling magnetoresistance in magnetic tunnel junctions with subnanometer thick Al2O3 tunnel barriers fabricated using atomic layer deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 15738–15745 (2020).

Meyerheim, H. L. et al. Geometrical and compositional structure at metal-oxide interfaces: MgO on Fe (001). Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 076102 (2001).

Bowen, M. et al. Large magnetoresistance in Fe/MgO/FeCo (001) epitaxial tunnel junctions on GaAs (001). Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 1655–1657 (2001).

Yuasa, S., Nagahama, T., Fukushima, A., Suzuki, Y. & Ando, K. Giant room-temperature magnetoresistance in single-crystal Fe/MgO/Fe magnetic tunnel junctions. Nat. Mater. 3, 868–871 (2004).

Ikeda, S. et al. A perpendicular-anisotropy CoFeB-MgO magnetic tunnel junction. Nat. Mater. 9, 721–724 (2010).

Dankert, A., Venkata Kamalakar, M., Wajid, A., Patel, R. S. & Dash, S. P. Tunnel magnetoresistance with atomically thin two-dimensional hexagonal boron nitride barriers. Nano Res. 8, 1357–1364 (2015).

Liao, L., Kovalska, E., Regner, J., Song, Q. & Sofer, Z. Two-dimensional van der Waals thin film and device. Small 20, 2303638 (2024).

Wang, W. et al. Spin-valve effect in NiFe/MoS2/NiFe junctions. Nano Lett. 15, 5261–5267 (2015).

Harfah, H., Wicaksono, Y., Sunnardianto, G. K., Majidi, M. A. & Kusakabe, K. High magnetoresistance of a hexagonal boron nitride-graphene heterostructure-based MTJ through excited-electron transmission. Nanoscale Adv. 4, 117–124 (2022).

Devaraj, N. & Tarafder, K. Large magnetoresistance in a Co/MoS2/graphene/MoS2/Co magnetic tunnel junction. Phys. Rev. B 103, 165407 (2021).

Yazyev, O. V. & Pasquarello, A. Magnetoresistive junctions based on epitaxial graphene and hexagonal boron nitride. Phys. Rev. B 80, 035408 (2009).

Gong, C. et al. Discovery of intrinsic ferromagnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals crystals. Nature 546, 265–269 (2017).

Deng, Y. et al. Gate-tunable room-temperature ferromagnetism in two-dimensional Fe3GeTe2. Nature 563, 94–99 (2018).

Fei, Z. et al. Two-dimensional itinerant ferromagnetism in atomically thin Fe3GeTe2. Nat. Mater. 17, 778–782 (2018).

Bonilla, M. et al. Strong room-temperature ferromagnetism in VSe2 monolayers on van der Waals substrates. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 289–293 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Tunneling spin valves based on Fe3GeTe2/hBN/Fe3GeTe2 van der Waals heterostructures. Nano Lett. 18, 4303–4308 (2018).

Yang, J. et al. Rationally designed high-performance spin filter based on two-dimensional half-metal Cr2NO2. Matter 1, 1304–1315 (2019).

Song, T. et al. Giant tunneling magnetoresistance in spin-filter van der Waals heterostructures. Science 360, 1214–1218 (2018).

Kim, H. H. et al. One million percent tunnel magnetoresistance in a magnetic van der Waals heterostructure. Nano Lett. 18, 4885–4890 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Very large tunneling magnetoresistance in layered magnetic semiconductor CrI3. Nat. Commun. 9, 2516 (2018).

Paudel, T. R. & Tsymbal, E. Y. Spin filtering in CrI3 tunnel junctions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 15781–15787 (2019).

Cai, X. et al. Atomically thin CrCl3: an in-plane layered antiferromagnetic insulator. Nano Lett. 19, 3993–3998 (2019).

Zhu, Y. et al. Giant tunneling magnetoresistance in van der Waals magnetic tunnel junctions formed by interlayer antiferromagnetic bilayer CoBr2. Phys. Rev. B 103, 134437 (2021).

Pan, L. et al. Large tunneling magnetoresistance in magnetic tunneling junctions based on two-dimensional CrX3 (X = Br, I) monolayers. Nanoscale 10, 22196–22202 (2018).

Feng, Y., Wu, X., Hu, L. & Gao, G. FeCl2/MoS2/FeCl2 van der Waals junction for spintronic applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 14353–14359 (2020).

Chu, J. et al. 2D polarized materials: ferromagnetic, ferrovalley, ferroelectric materials, and related heterostructures. Adv. Mater. 33, 2004469 (2021).

Zhou, J. et al. Large tunneling magnetoresistance in VSe2/MoS2 magnetic tunnel junction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 17647–17653 (2019).

Wu, Q. & Ang, L. K. Giant tunneling magnetoresistance in atomically thin VSi2N4/MoSi2N4/VSi2N4 magnetic tunnel junction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 120, 022401 (2022).

Sharan, A., Lany, S. & Singh, N. Computational discovery of two-dimensional rare-earth iodides: promising ferrovalley materials for valleytronics. 2D Mater. 10, 015021 (2022).

Sharan, A. & Singh, N. Intrinsic valley polarization in computationally discovered two-dimensional ferrovalley materials: LaI2 and PrI2 monolayers. Adv. Theory Simul. 5, 2100476 (2022).

Lu, H. et al. Ferroelectric tunnel junctions with graphene electrodes. Nat. Commun. 5, 5518 (2014).

Soler, J. M. et al. The SIESTA method for ab initio order-N materials simulation. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14, 2745–2779 (2002).

Brandbyge, M., Mozos, J. L., Ordejón, P., Taylor, J. & Stokbro, K. Density-functional method for nonequilibrium electron transport. Phys. Rev. B 65, 165401 (2002).

Papior, N., Lorente, N., Frederiksen, T., García, A. & Brandbyge, M. Improvements on non-equilibrium and transport Green function techniques: the next-generation TRANSIESTA. Comput. Phys. Commun. 212, 8–24 (2017).

Datta, S. Quantum transport: Atom to transistor (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2005).

Papior, N. sisl: v0.11.0 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this publication was supported by funding from the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). The authors gratefully acknowledge the KAUST supercomputing laboratory for providing computational resources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T. has conducted the calculations. A.R., N.S., and U.S. have contributed to the data analysis. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial or non-financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tyagi, S., Ray, A., Singh, N. et al. Magnetic tunnel junction based on bilayer LaI2 as perfect spin filter device. npj 2D Mater Appl 8, 57 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-024-00493-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-024-00493-6