Abstract

Two-dimensional (2D) van der Waals (vdW) magnets have sparked widespread attention due to their potential in spintronic applications as well as in fundamental physics. Ferromagnetic vdW compound Fe3GeTe2 (FGT) and its Ga variants have garnered significant interest due to their itinerant magnetism, correlated states, and high magnetic transition temperature. Experimental studies have demonstrated the tunability of FGT’s Curie temperature, TC, through adjustments in quintuple layer numbers (QL) and carrier concentrations, n. However, the underlying mechanism remains elusive. In this study, we employ molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) to synthesize 2D FGT films down to 1 QL with precise layer control, facilitating an exploration of the band structure and the evolution of itinerant carrier density. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) reveals significant band structure changes at the ultra-thin limit, while first-principles calculations elucidate the band evolution from 1 QL to bulk, largely governed by interlayer coupling. Additionally, we find that n is intrinsically linked to the number of QL and temperature, with a critical value triggering the magnetic phase transition. Our findings underscore the pivotal role of band structure and itinerant electrons in governing magnetic phase transitions in such 2D vdW magnetic materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

2D vdW materials have emerged as a promising platform for studying the influence of dimensionality and environmental factors such as Moirè structures and gating on correlated phenomena. While magnetic materials were among the last classes of 2D vdW materials to be discovered and explored1,2, the ability to manipulate magnetic states through external perturbations offers vast opportunities in magnetically controlled devices and spintronic technologies. Through techniques that can be applied to 2D materials like doping, electronic gating, and interfacial effects in heterostructures, these materials offer unprecedented opportunities for a materials-by-design approach customized for specific applications. Fe3GeTe2 (FGT), with the simplest vdW layer structure among the FenGeTe2 group, was first isolated in 1 QL form in 20183, and since has showcased remarkable properties, including itinerant carriers3,4,5,6, substantial coercive fields7, tunable TC5, topological spin textures8,9 and the presence of heavy fermions10. Above room temperature ferromagnetism in FGT has been accomplished through diverse methods such as stoichiometric changes11, atomic substitution12, liquid ionic gating5, femtosecond laser pulses13, and heterostructure fabrication14,15,16,17. All of which demonstrate the manipulation of TC via carrier density n modulation, as well as through proximity effects with substrates and adjacent metal atoms, such as Pt and Fe. Furthermore, topological states emerge in FGT thin films beyond 2 QL18, arising from the chirality of the arrangement of Ge/Fe atoms in adjacent quintuple layers combined with spin-orbit coupling, while such topological nodal line remains absent in the 1 QL.

FGT, with a finite density of states at the Fermi energy, exhibits a coexistence of itinerant and localized electrons. In bulk, the intra-atomic Hund coupling (JH) has been shown to play an exceeding role over the on-site repulsion (U) in governing the material’s behavior. Thus, FGT is distinguished as a site-differentiated Hund’s metal due to the distinct contributions from its two, nearly isovalent19 Fe (Fe I and Fe II) sites20. This classification provides an analytical framework for resolving the apparent discrepancies between the effective masses in bulk FGT determined by ARPES and by specific heat measurements18,21,22,23. These discrepancies stem from variations in Fe site Hund correlation strengths and orbital-selective scattering rates indicated by the spin susceptibility calculations in which the Fe I site diverges at low temperatures and the Fe II site plateaus at ~100 K. These studies suggest that, in bulk FGT, the Fe II site likely dominates the itinerant electron behavior, while the Fe I site hosts local magnetic moments.

Studies of electronic structures of FGT in the ultra-thin limit remain scarce, primarily due to the lack of samples with precise layer control. Using MBE, we fabricate high-quality FGT thin films with precise layer number control, with or without a capping layer, allowing us to perform in situ and ex situ measurements on FGT of 1 QL and multiple layers. Transport studies yield crucial information on their magnetic hysteresis, phase transitions, and the evolution of carrier concentrations, scrutinizing variations with temperature and QL number. We are able to investigate the electronic structures of uncapped samples through ARPES. A systematic comparative analysis between experimental ARPES data with site-, spin-, and orbital-resolved DFT band structure calculations reveals emergent bands, particularly at the Γ point, attributed to interlayer coupling in multilayer systems, with distinct site and orbital characteristics. This research not only advances our comprehension of the fundamental properties of FGT and other itinerant vdW magnetic materials, but also guides the design of such materials for potential applications in devices.

Results

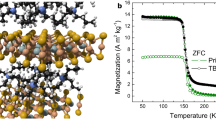

Structural characterization of FGT thin films

We utilize MBE to grow FGT thin films with the same method described in ref. 7. FGT has a quintuple layer structure with hexagonal symmetry belonging to the P63/mmc space group, with bulk lattice parameters a = b = 3.991 Å and c = 16.333 Å. As illustrated in Fig. 1a, a trilayer heterometallic slab of Fe (labeled Fe I and Fe II) and Ge is encapsulated by two Te layers, which are bonded to the adjacent FGT layers by the vdW force. We verify the single crystalline nature and thickness control of our films using scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) shown in Fig. 1b and c, respectively. STEM of a Ge substrate-1 QL FGT-Te cap heterostructure was performed as exemplified in Fig. 1b. High-angle annular dark-field cross-sectional images along the [010] direction distinctly reveal the presence of a well-oriented film without any discernible domains. The top layer of the Ge substrate, seemingly intermixed with Te, is attributed to averaging over the terraced Ge substrate configuration, where the 1 QL FGT rests on individual terraces. The XRD analysis reveals a singular phase in the FGT films, as illustrated in Fig. 1c, characterized by Laue oscillations. This serves as a confirmation of well-oriented and atomically smooth films. The extracted c-lattice parameter of 16.34 Å for the 10 QL aligns closely with the bulk c-lattice parameter of 16.33 Å6. Thickness fitting, validated by quartz crystal microbalance calibration during the growth, supports a film thickness of 10 QL. (See Supplementary Fig. 1 for XRD crystal truncation rod (CTR) measurements on a 3 QL FGT film and its analysis to confirm the crystal structure). Previous studies have indicated that the Fe content in FGT crystals can fluctuate up to 12% due to vacancies at the Fe II site effectively hole doping the FGT24,25,26. The presence of Fe vacancies in the films is inferred from deviations in XRD peak positions. Our scans reveal a remarkable agreement with bulk stoichiometric samples, aligning with a c parameter of 16.34 Å, indicating less than 3% Fe vacancies with respect to stoichiometric samples25. Temperature-dependent X-ray absorption (XAS) and X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) spectroscopy were conducted on 1 QL and 2 QL samples (see Supplementary Fig. 2). The line shapes of XAS are in good agreement with bulk samples. In the Fe L2 and L3 edge there does not exist much structure, this is likely due to metallic Fe states which are expected due to strong covalency. In the 1 QL Fe L3 edge, two peaks are identified: a main peak and shoulder toward higher binding energies located at 707.7 and 710.5 eV, respectively. Peak center analysis performed on the main L3 peak reveals a slight shift (~0.1 eV) toward lower binding energies in 2 QL samples. All characterization results collectively indicate that the grown FGT films are of high quality.

a Crystal structure of epitaxially grown FGT on Ge (111). The quintuple layer structure of FGT encompasses two non-equivalent Fe sites (Fe I and Fe II). b Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image depicting a 1 QL FGT film on Ge (111) substrate capped by Te with the structural model overlaid. c XRD 2θ/ω scan along the (00L) direction of an uncapped 10 QL FGT film on Ge (111). The figure indicates the (002L) family of Bragg peaks and the (111) and (333) Ge substrate peaks. Inset: Laue Oscillations of the (006) peak, and oscillation peak separation indicate a 10 QL FGT film and further reveal the atomic-level smoothness and the uniformity of the film.

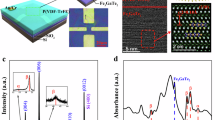

ARPES and DFT band structure

To explore the layer-dependent evolution and effects of interlayer coupling of the electronic structure, ARPES experiments were conducted on 1 and 2 QL samples using an unpolarized He 1α lamp at 21.2 eV and a temperature of 10 K. In Fig. 2a, the energy dispersion along the Γ to K high symmetry cut is presented, and Fig. 2c depicts the experimentally observed Fermi surfaces (FS). In both systems, a hexagonal Brillouin zone is observed, with spectral weight apparent near the Γ, K, and M points, marked in red. Note that previous literature reports an upturn of longitudinal resistivity at low temperatures, which is especially pronounced in the ultra-thin limit of FGT5,7. Our ARPES results and previous transport results7 provide direct evidence of the non-zero density of states at the Fermi energy in 1 and 2 QL samples. Thus, a band gap explanation of the insulating temperature dependence can be ruled out. As the thickness increases from 1 QL to 2 QL, we anticipate observing more bands within the Brillouin zone. Indeed, an evident increase in overall intensity is observed near the Γ point.

a ARPES data on 1 QL and 2 QL FGT, showing the energy dispersion between the Γ and K high symmetry points, as marked in red in c integrated over a 0.2 Å−1 window. b Calculated line cuts between the Γ and K high symmetry points for 1 and 2 QL, respectively. The spin-majority and minority bands are plotted in blue and red, respectively. The green arrow marks the emerging flat hole band in 2 QL. c Experimental Fermi surfaces for 1 and 2 QL films integrated over a 40 meV energy window. The first Brillouin zone is delineated in black. d Calculated Fermi surfaces of FGT at kz = 0 plane with spin-majority and minority bands plotted in blue and red, respectively. e, f Fe d-orbital-resolved DFT band structure along the high symmetry lines and corresponding projected DOS per Fe atom for the 1 QL (top) and 2 QL (bottom) systems projected on the Fe I (e) and Fe II (f) sites. The positive (negative) DOS denotes the majority (minority) spin part. The blue, red, and green colors represent the dyz/dxz, \({d}_{xy}/{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\), and \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) characters, respectively, and the symbol size shows the relative weight of the orbital contributions. In the lower panel of the f, the orange vertical arrow represents the splitting of the Fe II \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) band due to the interlayer coupling, and the red arrow marks the peak of Fe II \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) DOS of 2 QL FGT. The Fermi level (EF) is set to zero.

While the FS of the two systems share many features, notable distinctions are observed in the spectral weight at Γ. Specifically, the emerging intensity near the Γ point in the 2 QL system is attributed to a weakly dispersive, flat, hole band. Near the K and M points there exists some spectral weight, yet sharp, clearly dispersive bands are difficult to distinguish. This can be attributed to the small expected energy and momentum separation of the bands in line with previous reports10,21, as well as the broadening of the bands due to electron correlation20,27. DFT calculations indicate that no states should be populated near EF at M, with all bands positioned above the Fermi level in 1 QL, 2 QL, and bulk FGT. However, this contradicts the experimental findings where some intensity is observed at M in both 1 and 2 QL systems (Fig. 2d). This discrepancy may be rectified by a minor disagreement between the experimental and theoretical Fermi level positioning. A slight increase in the Fermi level would result in the bands at M becoming populated. As mentioned, the most prominent feature of 2 QL in our ARPES data is the enhanced spectral weight near Γ as a hole band. Our DFT calculation shows an additional flat band emerging at the corresponding energy just below EF, as indicated by a green arrow in Fig. 2b (lower panel). Further elucidation can be achieved by having the site- (Fe I and Fe II) and orbital-resolved band structure; see Fig. 2e, f. In 2 QL (lower panel), this Fe II \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) band is quite flat near Γ and located below EF, corresponding to the flat band identified in Fig. 2a, b. Consequently, it creates a sharp peak in the density of state (DOS) (indicated by a red arrow in the lower right panel of Fig. 2f). Our analysis uncovers that the inter-QL interaction is directly responsible for this emergent state. The band splitting caused by inter-QL coupling is ~0.5 eV, as indicated by an orange-colored vertical arrow (lower panel of Fig. 2f). The corresponding state in 1 QL located above EF (see the green-colored band at ~+0.15 eV in the upper panel of Fig. 2f), and therefore not probed in ARPES.

To further clarify the origin of this emergent flat band in 2 QL, we scrutinize the evolution of band structure by varying the inter-QL distance. As summarized in Supplementary Fig. 3, without interlayer interaction (when the interlayer distance is set to include an extra of 10 Å), this band is doubly degenerate and is located well above EF at ~+0.15 eV, which is in agreement with the case of 1 QL shown above. As the inter-QL distance is reduced, this Fe II \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) band splits into two parts with gradually increasing band splitting. Consequently, the Lifshitz transition occurs at the inter-QL distance between +2 and +3 Å, and the lower-lying band energy crosses below EF. At +0 Å (i.e., the actual equilibrium distance of 2 QL), the lower and upper band is found at − 0.05 and +0.47 eV, recovering the 2 QL band structure. It is interesting to note that, together with the greater band splitting, the dispersion of this band gets gradually flatter as the interlayer distance decreases, implying higher DOS, which yields stronger electron-electron interaction in this band. The thickness-dependent electronic structure evolution is also noticed in Fe I states. Fig. 2e shows that, in 1 QL, the \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) band is located at +0.3 eV near Γ. In 2 QL, on the other hand, it is split into the lower- and higher-lying bands at +0.1 eV and +0.6 eV, respectively. Again, this is attributed directly to the inter-QL interaction. Supplementary Fig. 3b shows that, by varying interlayer distance of 2 QL, the originally degenerate band at +0.3 eV progressively splits into two. In the case of Fe I, however, the lower-lying band energy is still higher than EF at the equilibrium distance, and, therefore, not visible in ARPES measurement. Thus the enhanced ARPES spectra in 2 QL around Γ mainly originated from Fe II sites. Here we note that the thickness-dependent evolution of electronic structure is more pronounced for the Fe II-derived states being comparable with those of Fe I. It is particularly interesting to recall that Fe II atoms form the innermost atomic layer of each QL while Fe I is positioned in the outer layer (see Fig. 1a). The analysis shows that the details of orbital hybridizations play an important role here (See Supplementary Fig. 4). As Te atoms lie above Fe II sites, well aligning along the c-axis, the Fe II \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital strongly hybridizes with anionic ligand pz. The presence or absence of the neighboring QLs can, therefore, significantly affect the electronic structure. For Fe I atoms, on the other hand, this strong σ bonding is not well defined along the out-of-plane direction owing to the deviated bond angles (from 180°) toward the outermost Te sites.

Another important difference in the band structure of 2 QL from 1 QL is the lifted degeneracy around the K point. Note that parabolic electron-like bands going across K in 1 QL are split into two and result in the double parabola in 2 QL; see, e.g., the dyz/xz (blue) and \({d}_{xy/{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) (red) bands while preserving the degeneracy at K point protected by C2y. They serve as the source of Berry curvature and are responsible for the anomalous Hall signal, as reported by Kim et al.18. Beyond 2 QL, interlayer coupling persists and further induces band structure evolution (see Supplementary Fig. 5). As for the \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) band split at Γ, it is noted that the Fe I band is also pushed down below EF in the case of bulk while it remains above EF in 3 QL. More dispersive bands around K also exhibit systematic evolution as the QL-thickness increases. Ultimately, the band structure of bulk FGT closely resembles that of 3 QL, suggesting that the most significant evolution occurs between 1 QL and 2 QL.

Transport measurements and Hall carrier densities

To complement our probe of electronic states using ARPES, we investigate itinerant carrier densities n in FGT samples with varying layer numbers and at different temperatures using magneto-transport measurements, as the carrier density n has been shown to play a critical role in controlling the magnetic transition temperature of FGT in various reports, such as the gating experiment by Deng et al.5. The itinerant density acts as a global indicator of the density of states within kBT of the Fermi energy, allowing for comparisons with our ARPES and DFT results as well as the previous studies21,28. The progression of the carrier density is intricately linked to that of the electronic band structure, offering insights into identifying itinerant bands among all the bands and, consequently, the magnetic properties, with a specific focus on the roles of itinerant carriers in FGT. The effects extend to changes to the effective mass, orbital character, and DOS near EF. A link between carrier density, magnetic phase transition, and band evolution has yet to be established. Transverse resistance Rxy measurements are used to probe the conventional Hall RH and anomalous Hall RAH behavior, as shown in Fig. 3a, c. The raw data was initially antisymmetrized to correct for deviations from ideal contact geometry following Deng et al.5. The resulting data contains contributions from RAH and RNH in the form Rxy = RAH + RNH, where the conventional linear Hall response RNH = RHH is a function of the applied magnetic field H and RAH = RSM, the anomalous Hall response, is a function of the magnetization M. RS and RH are coefficients which characterize the strength of RAH and RNH respectively. The data RAH presented in Fig. 3a has removed the RH component by globally subtracting a linear contribution (dashed lines in Fig. 3c) determined by the saturated high field region. Anomalous Hall RAH measurements reveal magnetic behavior through pronounced square shape hysteresis curves for all quintuple layers at low temperature (5 K), indicating robust ferromagnetism (Fig. 3a). The pronounced square shape of these hysteresis loops suggests a large anisotropy and single FGT domain in our high-quality films. Fe vacancy content can also be estimated with the shape of the loops, which will decrease the perpendicular magnetic anisotropy and lead to a decrease in the coercive field26, and round the hysteresis loops. In our samples, the square shape implies stoichiometry, and the resulting coercivities agree with or are greater than other MBE-grown films5,29. The dependence of coercive fields, remanent, and saturation resistance on temperature and QL number is consistent with the findings in the previous report7.

a Anomalous Hall resistance (RAH) as a function of applied magnetic field for 1–10 QL at 5 K. The magnetic field is applied out-of-plane to the substrate, parallel to the c-axis of FGT. All layer numbers display a ferromagnetic response with varying coercivity, remanent resistance, and saturation resistances. Coercive field values decrease from 1 QL sample and stabilize as thickness increases. b TC as a function of the number of layers. Arrott plot analysis is employed to extrapolate TC by fitting anomalous Hall data, allowing for a more precise determination of TC, which is identified to rise concurrently with sample thickness. Unfilled circles correspond to measurements taken on different samples that had identical thicknesses. From 1–10 QL TC rises by roughly 100 K. c Antisymmetrized Rxy data, incorporating contributions from both conventional and anomalous Hall responses emphasizing distinctions in linear contributions of the high-field region, marked by the dashed line.

An accurate determination of TC is achieved through Arrott plot analysis (See Supplementary Fig. 6). We utilize the equation \({R}_{AH}^{2}={\mu }_{0}H/{R}_{AH}\) and perform a linear fit for the data in the high-field region and extrapolate to the intercept of \({R}_{AH}^{2}\). This is done for all temperatures below TC and the resulting intercepts are again plotted and linearly fit. The intercept of the fit is then assumed to be TC. The magnetic phase transition is found to increase with the QL number shown in Fig. 3b. For 1 QL sample, TC is found to be roughly 75 K, and increases up to 175 K for 10 QL samples, as indicated by the relatively coarse (25 K) temperature sampling intervals.

Having determined the TC, we now focus on exploring the carrier densities n as a function of temperature for 1–10 QL samples using the conventional Hall coefficient. The Hall coefficient RH is extracted from the saturated region of the Hall resistance Rxy between μ0H = 2 and 4 T, where the hysteresis vanishes (Fig. 3c). When the anomalous Hall effect reaches saturation, indicating the magnetic response has stabilized, the slope of Rxy directly relates to the conventional Hall coefficient, RH, which reveals the carrier type and concentration. Above the saturation field, we observe a linear field dependence extending to B > 6 T of Rxy for all temperatures and thicknesses that implies single hole-type carriers, as shown in Fig. 3c for the 1 and 10 QL samples, where different coefficients for the linear term are evident. Despite the presence of multiple bands at the Fermi level, the observation of a single hole-type carrier concentration from the linear dependence of RH suggests that we are predominantly probing a majority carrier type as holes. Upon comparing the calculated band structures in Fig. 2, we can deduce that we are probing the holes residing in the bands centered at the Γ point, while the electrons in the bands near the K point (which are known to be mainly of Fe I character) appear to remain localized. This localization may stem from a large effective mass resulting from the stronger correlation of the Fe I20, although the precise cause remains undetermined at this juncture. This analysis unveils the hole-type carrier dominance in transport, as the itinerant carriers, which also coincides with the fact that our ARPES results show distinct bands and high intensity centered around the Γ point, while the electron bands near K and M points are not clearly shown in ARPES. As the QL number increases, the Hall coefficient RH decreases and saturates above 4 QL (Fig. 4a). Our DFT calculations of RH based on the Boltzmann transport theory are also displayed in Fig. 4a (magenta diamonds). The positive value of calculated RH indicates a dominant hole-type carrier, as experimentally observed. The calculation shows the same trend as the experimental results of decreasing RH with increasing thickness. This decrease in RH can be attributed to the band evolution, including the introduction of the emergent bands at Γ, in 2 QL and beyond. A quantitative comparison shows good agreement between the calculation and experiments roughly following the fitting line RH(N) = λ/N. The discrepancy in 1 QL may be attributed to the introduction of external electron carriers in the experimental Hall measurements, which thereby increases \({R}_{H}=\frac{1}{e({n}_{h}-{n}_{e})}\) at the high field limit (e: the charge of an electron, nh (ne): hole (electron) carrier density)30,31. Note that this deduction is also consistent with the slight increase in the Fermi level observed by our ARPES results.

a Conventional Hall coefficient, RH, vs QL number. Filled black circles and empty magenta diamonds represent experimentally measured RH of 1–10 QL FGT films at 5 K and calculated sheet Hall coefficient, respectively. Both results demonstrate a decreasing trend of RH with increasing thickness. The gray dashed line denotes the fitting of experimental RH of 2–10 QL films to RH(N) = λ/N (λ: fitting parameter, N: the number of QL). b 2D carrier density normalized by QL number, extracted from the conventional Hall response. c 2D carrier density at temperatures near, but below TC, determined by vanishing remnant resistance. The light green horizontal line is a guide to the eye. The values of the 2D carrier density are roughly constant at TC. Unfilled circles correspond to measurements taken on different samples that had the same thicknesses. d The calculated ID(EF) (solid line, filled markers) and magnetization m per Fe atom (dashed line, empty markers) as a function of thickness. The ∞ QL indicates bulk. The triangles (blue-colored), squares (red), and circles (green) show the Fe I, Fe II and their average values, respectively. The thick gray line for Fe II is a guide to the eye.

To access the information of itinerant hole densities in each QL in our samples, we plot carrier concentrations normalized by the number of QL n2D/QL as shown in Fig. 4b. The carrier concentration increases upon lowering the temperature for all QL numbers, although there is no monotonic dependence on the QL numbers at each temperature. This unusual temperature-dependent behavior can be influenced by various factors and is discussed in more detail in the Discussion Section. When examining the carrier density near the TC, we make an intriguing discovery: the normalized carrier density n2D/QL remains nearly constant, as depicted in Fig. 4c. This unexpected observation suggests that itinerant electrons play a pivotal role in the magnetic phase transitions of FGT, as discussed below.

Discussion

We established the full evolution of the FGT band structure from the ultra-thin limit to the bulk. In the 1 QL system, positive RH shown by our calculations and experiments indicate that the dominant carriers are of the hole type, possibly attributed to the bands near Γ forming hole pockets (Fig. 2b, d).

Moving to the 2 QL system from 1 QL, the observed increase in carrier density measured by transport is mirrored by the presence of more hole bands and the emergence of the Fe II \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) flat band. Both theoretical predictions and experimental observations demonstrate that the apex of the lower split band flattens as the thickness increases from 1 to 2 QL, suggesting that 2 QL FGT may possess holes with a larger effective mass and DOS at EF. DFT indicates the emergent flat hole band in the 2 QL system does not cross the Fermi level, thus precluding the formation of a hole ‘pocket’. Consequently, this band would not contribute to the transport properties of the material. However, it is worth noting that several factors may potentially alter the band’s position relative to EF, such as a Fermi level shifting, or band broadening effects, and effectively bring the band closer to EF, thereby enabling its participation in the transport properties of the system. Unveiling the possible contributions from the correlated states may be crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the material’s electronic structure and transport behavior.

The observed temperature evolution of n within the ferromagnetic phase (Fig. 4b) is not well reflected using our DFT-based calculation. We found that the calculated RH (thereby n by inversing RH) near EF shows no appreciable change by simply altering temperature for the Fermi-Dirac distribution function within the rigid-band approximation of the ferromagnetic band structure. Considering the well-known limitations of standard approximations adopted here, the correlated electronic behavior, as well as the quantum effect beyond semi-classical transport theory, missing from our current calculations, may be required. In fact, the temperature-dependent electronic structure change shows some low-energy features, indicating correlated-electron behaviors10,20,21,28.

Also, it may be crucial to consider the intricacies of the band structure near EF. One such scenario is based on the asymmetry shapes of the hole and electron around EF. As the temperature increases, thermal broadening effects come into play, potentially “populating” the electron bands situated right above EF, particularly in the vicinity of the K and M points in the Brillouin zone. This will explain the observed drop in the hole carrier density.

Despite varying carrier densities with QL number and temperature, we find the thickness normalized carrier density n2D/QL at TC is nearly constant as presented in Fig. 4c, further supporting the importance of itinerant electrons in determining the magnetic phase. Below the critical density identified to be n2D/QL ~4 × 1014 h+/cm2 (i.e., above TC), the indirect exchange interactions mediated by the itinerant carriers are not strong enough to magnetically order the local moments against perturbations such as thermal fluctuation.

To further elucidate the role of itinerant holes in magnetism, we investigate the detailed electronic structure with the Stoner model as a function of thickness (Fig. 4d). First, it shows that for all thicknesses, Stoner criterion of ferromagnetism is satisfied, ID(EF) > 1 (I refers to Stoner parameter and D(EF) non-spin-polarized DOS at EF). Further, its site dependence is quite intriguing. Note that ID(EF) of itinerant Fe II monotonically increases, whereas that of localized Fe I is much less changed and featureless. Combined with the monotonic increase of TC (see Fig. 3b), it indicates the role of itinerant-type carriers being in line with the aforementioned feature of constant n2D/QL at T = TC. In addition, as the FS shows Lifshitz transition with QL number (e.g., the emergence of the Fe II \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) flat band), it may, in turn, change the Stoner excitation due to the itinerant d electrons32. A detailed study on the thickness evolution of Stoner excitation may be an interesting future direction to deepen our understanding of FGT magnetism.

Summary

In summary, we have elucidated the evolution of the band structure and its relationship with carrier density in FGT as a function of thickness, through a combined analysis of ARPES experiments and DFT calculations. Our findings reveal the emergence of a hole-like band near the Γ point in 2 QL FGT, attributed to interlayer coupling, absent in the 1 QL FGT. Furthermore, we observed an inverse correlation between hole carrier density and temperature. Remarkably, the carrier density per layer remains consistent across all layer numbers near their respective TC, indicating the critical role of itinerant holes in mediating the magnetic exchange in FGT. Our study offers unique and valuable insights into the evolution of electronic structure and ferromagnetism in FGT thin films, shedding light on similar phenomena in other itinerant vdW ferromagnetic materials. These findings hold significant promise for future applications, as a deeper understanding of the mechanisms driving the magnetic state facilitates the design and development of innovative electronic and magnetic devices.

Methods

MBE growth

Single crystalline Ge (111) substrates were prepared ex situ by a hydrochloric acid (HCl) etching process. Substrates were etched in a 1:2 solution of deionized (DI) water to HCl for 30 min to remove organic materials from the surface. After treatment, substrates were subsequently rinsed and submerged into room temperature DI water for an inconsequential amount of time, and then loaded into a Veeco GENxplor MBE system with a base pressure of 5 × 10−11 Torr. Further substrate and sample preparation are in accordance with ref. 7. Ge was then deposited to improve the substrate surface. Ge buffer layers were grown at a rate of roughly 70 s per layer as determined by a quartz crystal microbalance (QCM). As a result, RHEED diffraction patterns were significantly improved7. Fe3GeTe2 films were synthesized using a Veeco GENxplor system. Standard effusion cells are mounted at the bottom of the chamber facing the same point at the center of the chamber where the substrate is facing downwards. Source materials of Fe (99.98%), Ge (99.999%), and Te (99.9999%) were evaporated from the effusion cells at 1170, 1120, and 365 °C, respectively. Elements were co-deposited on the substrate at 330 °C to grow FGT. The ratio of Fe:Ge:Te was set at 3:1:5.6 measured by QCM prior to growth. The deposition rate was 70 s per QL. RHEED oscillations confirmed layer-by-layer growth. After the growth of FGT, 15 nm of Te was deposited at room temperature as a capping layer. Without the capping layer, loss of RHEED pattern of FGT confirmed amorphous surface oxidation after exposure to the air for a few minutes. FGT samples are capped with a 15 nm Te crystalline layer which is found to protect against oxidation at timescales greater than the duration of the experiment33. In our samples, no exchange bias is present as the coercive field is symmetric about zero applied field pre-antisymmetrization. This serves as a check against oxidized samples in accordance with ref. 34, and a verification of single-phase samples where AFM oxidized FGT can couple to pristine FM FGT. Unoxidized films are further confirmed by the lack of an observed tail in the hysteresis curves35 in Fig. 3a. To rule out any Ge, Te, and GeTe structures contribution to RH and RAH test samples of Te capped Ge (111) were measured in the transverse geometry at low temperatures. The resulting data does not possess any hysteretic response and is extremely insulating. Thus, we are confident that the electronic channels that dominate the electronic response at low temperatures belong to FGT films.

X-ray diffraction, CTR, and XAS

X-ray diffraction was performed in a high-resolution Bruker system at room temperature. A parallel beam (PB) configuration was implemented with a copper anode where Kα1 and an emission channel was used. The voltage and current were set to 40 kV and 40 mA, respectively. CTR data was taken at the Advanced Photon Source, Beamline 33ID, at base temperature. The XAS curves of Fe L-edge were measured with a total electron mode, at 20, and 120 K, in the REIXS beamline of the Canadian Light source.

ARPES

The ARPES measurements were conducted at the UBC-Moore Center for Ultrafast Quantum Matter using a Scienta DA-30L hemispherical analyzer and the He 1α line at 21.2 eV. The measurements took place in ultra-high-vacuum with a base pressure lower than 6 × 10−11 Torr, at a temperature of 10K. The momentum and energy resolutions of the system are <0.003 Å−1, and 10 meV, respectively. High-resistivity samples were grounded using carbon paste. At these low temperatures, however, some charging effects were identified as a constant shift of the chemical potential to lower kinetic energies compared to an amorphous gold reference (<0.2 eV for all measured samples). To compensate for this, the real chemical potential was determined from a fit of the angle-integrated spectra to the Fermi-Dirac distribution, and the energies were shifted accordingly. Samples were grown in the aforementioned MBE on a “bullet” sample holder designed in-house and transferred from the MBE to the ARPES chamber on the same holder. Ultra-high vacuum (6 × 10−11 Torr) was maintained during transfer to protect the sensitive sample surfaces.

Electrical transport measurements

Transport measurements were carried out in a Quantum Design physical properties measurement system (PPMS), where van der Pauw geometry was used to measure Rxx and anomalous Hall response. Contacts were made via indium cold welding and attached via a gold wire. Hall resistance was measured as a function of the magnetic field at fixed temperatures.

Density functional theory

We performed first-principles DFT calculations based on the projector augmented-wave (PAW) method as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)36,37. We adopted generalized gradient approximation (GGA) for the exchange-correlation functional as parameterized by Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE)38. 18 × 18 × 4 and 18 × 18 × 1 k-grid were used for the bulk and N QL FGT (where N = 1–5), respectively, with an energy cutoff of 500 eV. Both lattice parameters and internal atomic positions were fully optimized with a force criterion of 0.01 eV/Å. The non-local optB86b-vdW functional39,40 was used for all the structure optimizations to account for the interlayer van der Waals interactions, which was proven to be reliable in our previous study41. For N QL FGT, a vacuum thickness of more than 18 Å and dipole correction were taken into account along the direction perpendicular to the layer to avoid any artificial interactions between the periodic images. We calculated RH using the BoltzTraP2 package based on Boltzmann transport theory42,43. We used a five times denser grid with BoltzTraP2 which is interpolated from 48 × 48 × 1 input k-grid. For the calculation of RH, constant relaxation time approximation (CRTA) is used. Under this condition, the RH is independent of the constant relaxation time τ, which is canceled out in RH42,43. The transport calculations are performed within rigid-band approximation (RBA) and an input temperature of 300 K. We also have checked that the choice of the input temperature turns out to have an insignificant effect on RH and does not qualitatively change the conclusion.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gong, C. et al. Discovery of intrinsic ferromagnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals crystals. Nature 546, 265–269 (2017).

Huang, B. et al. Layer-dependent ferromagnetism in a van der Waals crystal down to the monolayer limit. Nature 546, 270–273 (2017).

Fei, Z. et al. Two-dimensional itinerant ferromagnetism in atomically thin Fe3GeTe2. Nat. Mater. 17, 778–782 (2018).

Zhao, M. et al. Kondo holes in the two-dimensional itinerant ising ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2. Nano Lett. 21, 6117–6123 (2021).

Deng, Y. et al. Gate-tunable room-temperature ferromagnetism in two-dimensional Fe3GeTe2. Nature 563, 94–99 (2018).

Deiseroth, H. J., Aleksandrov, K., Reiner, C., Kienle, L. & Kremer, R. K. Fe3GeTe2 and Ni3GeTe2 - Two new layered transition-metal compounds: crystal structures, HRTEM investigations, and magnetic and electrical properties. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 8, 1561–1567 (2006).

Roemer, R., Liu, C. & Zou, K. Robust ferromagnetism in wafer-scale monolayer and multilayer Fe3GeTe2. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 4, 1–7 (2020).

Wu, Y. et al. Néel-type skyrmion in WTe2/Fe3GeTe2 van der Waals heterostructure. Nat. Commun. 11, 3860 (2020).

Birch, M. T. et al. History-dependent domain and skyrmion formation in 2D van der Waals magnet Fe3GeTe2. Nat. Commun. 13, 3035 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Emergence of kondo lattice behavior in a van der waals itinerant ferromagnet, Fe3GeTe2. Sci. Adv. 4, 1–9 (2018).

Ribeiro, M. et al. Large-scale epitaxy of two-dimensional van der Waals room-temperature ferromagnet Fe5GeTe2. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 6, 1–9 (2022).

Zhang, G. et al. Above-room-temperature strong intrinsic ferromagnetism in 2D van der Waals Fe3GaTe2 with large perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–8 (2022).

Liu, B. et al. Light-tunable ferromagnetism in atomically thin Fe3GeTe2 driven by femtosecond laser pulse. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 267205 (2020).

Li, G. et al. Temperature-induced self-decomposition doping of Fe3GeTe2 to achieve ultra-high Tc of 496 K for multispectral compatible strong electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 1–17 (2023).

Zhao, Q. et al. Proximity-induced interfacial room-temperature ferromagnetism in semiconducting Fe3GeTe2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 46520–46526 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Interfacial engineering of ferromagnetism in wafer-scale van der Waals Fe4GeTe2 far above room temperature. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–8 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Above room-temperature ferromagnetism in wafer-scale two-dimensional van der Waals Fe3GeTe2 tailored by a topological insulator. ACS Nano 14, 10045–10053 (2020).

Kim, K. et al. Large anomalous Hall current induced by topological nodal lines in a ferromagnetic van der Waals semimetal. Nat. Mater. 17, 794–799 (2018).

Bai, X. et al. Antiferromagnetic fluctuations and orbital-selective Mott transition in the van der Waals ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2. Phys. Rev. B 106, L180409 (2022).

Kim, T. J., Ryee, S. & Han, M. J. Fe3GeTe2: a site-differentiated Hund metal. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 1–6 (2022).

Xu, X. et al. Signature for non-Stoner ferromagnetism in the van der Waals ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2. Phys. Rev. B 101, 1–6 (2020).

Zhu, J. X. et al. Electronic correlation and magnetism in the ferromagnetic metal Fe3GeTe2. Phys. Rev. B 93, 1–6 (2016).

Chen, B. et al. Magnetic properties of layered itinerant electron ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 82, 1–7 (2013).

Liu, S. et al. Wafer-scale two-dimensional ferromagnetic Fe3GeTe2 thin films grown by molecular beam epitaxy. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 1, 1–6 (2017).

May, A. F., Calder, S., Cantoni, C., Cao, H. & McGuire, M. A. Magnetic structure and phase stability of the van der Waals bonded ferromagnet Fe3−xGeTe2. Phys. Rev. B 93, 014411 (2016).

Park, S. Y. et al. Controlling the magnetic anisotropy of the van der Waals ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2 through hole doping. Nano Lett. 20, 95–100 (2019).

Ghosh, S., Ershadrad, S., Borisov, V. & Sanyal, B. Unraveling effects of electron correlation in two-dimensional FenGeTe2 (n = 3, 4, 5) by dynamical mean field theory. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 86 (2023).

Corasaniti, M. et al. Electronic correlations in the van der Waals ferromagnet fe3gete2 revealed by its charge dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 102, 161109 (2020).

Tan, C. et al. Hard magnetic properties in nanoflake van der Waals Fe3GeTe2. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–7 (2018).

Kane, M. J., Apsley, N., Anderson, D. A., Taylor, L. L. & Kerr, T. Parallel conduction in GaAs/AlxGa1−xAs modulation doped heterojunctions. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 18, 5629 (1985).

Pippard, A. B. Magnetoresistance in Metals (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1989).

Bao, S. et al. Neutron spectroscopy evidence on the dual nature of magnetic excitations in a van der Waals metallic ferromagnet Fe2.72GeTe2. Phys. Rev. X 12, 011022 (2022).

Xie, W. et al. Air stability and composition evolution in van der Waals Fe3GeTe2. APL Mater. 12, 031102 (2024).

Gweon, H. K. et al. Exchange bias in weakly interlayer-coupled van der Waals magnet Fe3GeTe2. Nano Lett. 21, 1672–1678 (2021).

Kim, D. et al. Antiferromagnetic coupling of van der Waals ferromagnetic Fe3GeTe2. Nanotechnology 30, 245701 (2019).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Klimeš, J., Bowler, D. R. & Michaelides, A. Van der Waals density functionals applied to solids. Phys. Rev. B 83, 195131 (2011).

Dion, M., Rydberg, H., Schröder, E., Langreth, D. C. & Lundqvist, B. I. Van der Waals density functional for general geometries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 246401 (2004).

Jang, S. W. et al. Origin of ferromagnetism in Fe3GeTe2 and its manipulation. Nanoscale 12, 13501–13506 (2020).

Madsen, G. K. H. & Singh, D. J. BoltzTraP. A code for calculating band-structure dependent quantities. Comput. Phys. Commun. 175, 67–71 (2006).

Madsen, G. K. H., Carrete, J. & Verstraete, M. J. BoltzTraP2, a program for interpolating band structures and calculating semi-classical transport coefficients. Comput. Phys. Commun. 231, 140–145 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This research was undertaken thanks in part to funding from the Max Planck-UBC-UTokyo Center for Quantum Materials and the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, Quantum Materials and Future Technologies Program. The work at the University of British Columbia was also supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), the British Columbia Knowledge Development Fund (BCKDF), the Department of National Defence (DND), the Canada Research Chairs Program (A.D.), the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s EPiQS Initiative, Grant GMBF4779 (A.D.), and the CIFAR Quantum Materials Program (A.D.). R.J.G. acknowledges the support of NSERC. T.J. and J.L. acknowledge the support of the Mitacs Globalink Research Award. M.J.H. and D.H.D.L. were supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (Grant Nos. 2021R1A2C1009303 and RS-2023-00253716). The work at the Canadian Light Source was supported by CFI, NSERC, the National Research Council (NRC), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Government of Saskatchewan, and the University of Saskatchewan. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Electron microscopy at Cornell supported by the National Science Foundation materials innovation platform, PARADIM (Platform for the Accelerated Realization, Analysis, and Discovery of Interface Materials) under Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-2039380.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.R., C.K., and K.Z. conceived the experiments. D.H.D.L. and M.J.H. conducted DFT calculations. R.R., V.H., T.J., C.L., and J.L. grew the samples. R.R., Z.Z., and H.S. performed the CTR experiments. X.Z. and D.M. carried out STEM. R.R., S.S., G.L., M.M., and A.D. were responsible for ARPES measurement and analysis. R.R., R.G., and S.G. executed XAS. R.R. probed and analyzed transport results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roemer, R., Lee, D.H.D., Smit, S. et al. Unraveling the electronic structure and magnetic transition evolution across monolayer, bilayer, and multilayer ferromagnetic Fe3GeTe2. npj 2D Mater Appl 8, 63 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-024-00499-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-024-00499-0

This article is cited by

-

Orbitronics in two-dimensional materials

npj Spintronics (2025)