Abstract

Heterostructures between 2D and 3D electron systems remain critically important in developing novel and efficient optoelectronic and electronic devices. In this study, a vertical heterojunction between monolayer MoS2 and bulk InSe was developed. This heterojunction exhibits a type-I band alignment that facilitates rapid energy transfer from the wide bandgap MoS2 to the narrow bandgap InSe resulting in quenching of the MoS2 photoluminescence (PL) emission and enhancement of the A exciton emission in InSe. Temperature-dependent PL measurements of MoS2 on SiO2, MoS2 on InSe, and bare InSe revealed the critical role of defect trapping and electron-phonon coupling in the optical response of MoS2 on InSe. These results demonstrate that heterostructures combining monolayer MoS2 on bulk InSe, showing marked improvement relative to bare InSe, would be advantageous when incorporated into optoelectronic devices such as photodetectors, light emitters, and color converters and highlights the benefit of creating van der Waals (vdW) heterostructures with tailored properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

2D Heterostructures have become foundational in many electronic and optoelectronic devices including tunneling transistors, photodetectors, and solar cells1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Of the plethora of emerging heterostructures, combinations of 2D semiconducting materials have been heavily investigated due to relative atomic coordination and electronic energy scales between layers leading to unique Moiré patterns/potentials9,10,11, interlayer exciton formation12, and ultrafast charge transfer13. Heterostructures between 2D and 3D materials have also become incredibly important as materials such as transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) are integrated into more complex device architectures, necessitating control of interfacial properties between the 2D material and substrate, dielectric materials, contacts, and other semiconductors14. Electronic devices such as Schottky rectifiers between graphene and the wide bandgap semiconductor gallium nitride have shown excellent rectifying behavior, low leakage current and large barrier heights relative to devices with more conventional 3D semiconductors15. Highlighting the utility of combining the exquisite properties of 2D semiconductors with conventional bulk 3D materials, 2D/3D optoelectronic structures such as black phosphorous/silicon and graphene/silicon photodetectors have also demonstrated utility in creating high-speed and high-responsivity devices operating in the UV and IR regimes, respectively16,17. Understanding the fundamental interactions and energy transfer processes at the interfaces of these heterostructures is challenging as conventional 3D materials possess dangling bonds at the surface which lead to strong hybridization and atomically sharp scattering centers when coupled to 2D materials. Interfacing 2D and 3D electron systems through vdW bonding alone, that is atomically thin 2D materials with bulk-like 2D materials, provides a valuable opportunity to understand the emergent effects in 2D/3D heterostructures (from the interface between 2D layered materials and 3D materials with dangling bonds) without destroying the quantum delocalization and coherence of the 2D electron system.

Of the many semiconductors currently being explored for next-generation electronics and optoelectronics, semiconducting layered InSe has demonstrated an exceptional combination of properties including electron mobility exceeding 1000 cm2/Vs and a direct band gap from nm-scale to bulk thicknesses18. Recently, significant advancements have been made in InSe research with demonstration of wafer-scale growth19, tunneling transistors20, ballistic transistors21, and broadband photodetectors22,23, making it an attractive material for high performance and low-power electronic and optoelectronic devices with the potential to be tuned to specific applications. For example, the band gap can be tuned by layer number to access a photoresponse from infrared through the visible range18,24, enabling band-engineered light emitting and photodetector devices. Additionally, the valence band edge transitions from a wide parabolic dispersion to a “Mexican hat” dispersion as the material is reduced from bulk to monolayer, providing a platform to tune and probe flat band physics25,26. Further, a strong luminescent response and strong exciton-exciton and exciton-phonon interactions make InSe a prospective material for near-infrared lasing27,28. Already, bulk InSe has demonstrated high-performing device implementation in photodetectors29,30,31, field-effect transistors32,33, gas sensors34, neuromorphic memory35, and more36.

Despite the growing interest in InSe, heterostructures combining InSe with 2D semiconductors have been relatively sparse. From early examples, it is clear that semiconducting heterostructures, including InSe, exhibit enhanced performance as photoelectrochemical devices (BP/InSe37 and InSe/Ge-doped InSe38), photodetectors (MoS2/InSe39, InSe/GaSe40, InSe/WSe241,42), and electronic devices (InSe/GeSe43). As the research community continues to explore heterostructures beyond those of only monolayer TMDs, understanding the roles of differences in lattice structure, band structure, and interface defects becomes critically important towards the goal of developing heterostructure-based optoelectronics. In this work, we investigate the effect of interlayer electronic interactions on the photoluminescence response in a 2D MoS2/bulk InSe heterostructure. The results herein demonstrate ultrafast energy transfer within this Type I heterostructure leading to a suppression of PL emission from MoS2 excitons and a temperature-dependent enhancement of InSe PL. In this heterostructure, monolayer MoS2 is found to act as an efficient, light-absorbing passivation layer which enhances the optical output of InSe, enabling improved optoelectronic performance.

Results

MoS2 on InSe heterostructure

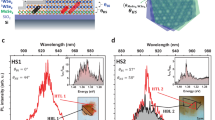

The MoS2/InSe heterostructures were fabricated by exfoliation of a monolayer MoS2 flake onto a PDMS stamp and transfer onto a freshly cleaved bulk piece of γ-InSe (schematically depicted in Fig. 1a) inside an argon-filled glove box (<1ppm O2 and H2O). Thick bulk crystals of InSe were chosen (>100 µm) as not only does InSe exhibit thickness-dependent optical properties due to quantum confinement, but also potential polariton effects for thicknesses up to 6 µm18,44,45. The room temperature Raman spectrum (collected with 514.5 nm excitation) from bare InSe (Fig. 1b, gray) shows sharp peaks corresponding to known vibrational modes of InSe and additional harmonics indicative of a high-quality crystal. With MoS2 on top (Fig. 1b, blue), additional peaks appear at 385.6 cm−1 and 407.7 cm−1 corresponding to the E2g and A1g Raman modes of monolayer MoS2, respectively (see Fig. 1b, inset). PL measurements (Fig. 1c, d) performed at 200 K (all PL measurements made between 4 K and 300 K are given in Supplementary Section 7) depict two major regions corresponding to excitonic emission from InSe around 1.28 eV and excitonic emission from MoS2 around 1.85 eV. The MoS2 PL emission energy confirms that the MoS2 used is monolayer, however, the spectral distance between E2g and A1g Raman modes for MoS2 on InSe (22.1 cm−1) is found to be larger than the typical value for MoS2 on SiO2 (19.5–20.5 cm−1). This separation has been shown to be influenced by interactions with the substrate including electronic doping and strain46. The Raman peak positions in the MoS2 on InSe are consistent with a small amount of strain (<0.1%) and significant p-type contact doping (~7 × 1012 cm−2)46. In the energy range pertaining to the InSe emission, two peaks corresponding to the excitonic transition and a P-band were observed in both the bulk InSe and MoS2/InSe heterostructure around 1.304 eV and 1.284 eV, respectively47. The excitonic transition in InSe has been named the “A” exciton of InSe in analogy with the “A” excitons observed in 2D TMDs (AInSe), which originates from emission between the valence and conduction bands at the Γ point. The P-band emission from InSe has been attributed to exciton–exciton scattering, as observed in other semiconductor systems48, and is also evidenced by super-linear power dependence of PL intensity (further information shown in Supplementary Fig. 4). The lower intensity AInSe arises from a transition between s-like conduction band to pz-like valence band state which is selectively excited by light polarized with \(\vec{E}\) ∥ \(\hat{c}\), where \(\hat{c}\) is the direction perpendicular to the InSe layers, leading to a smaller measured response in normal-incidence, confocal measurements49.

a Ball and stick model of a MoS2/InSe heterostructure with cartoon signifying the in-plane and out-of-plane excitons of MoS2 and InSe, respectively, (left) and optical image of one-few layer MoS2 on bulk InSe (right). Scale bar is 10 µm. b Room temperature Raman spectra of bare InSe (gray) and MoS2 on InSe (blue). Peaks corresponding to the Raman modes in InSe are labelled in black. Inset: Zoomed-in spectrum showing the MoS2 Raman modes (labelled in blue) among the second-order InSe Raman modes. c PL spectra of InSe with and without MoS2 (blue and gray, respectively), decomposed into two peaks (dotted lines) corresponding to the P-band and AInSe exciton. d PL emission of MoS2 on SiO2 and on InSe (green and blue, respectively), inset shows a rescaled MoS2/InSe PL spectrum. e Band structure for the heterostructure composed of a MoS2 monolayer and InSe (structure described in Supplementary Fig. 2) and projected density of states (PDOS) that differentiate contributions from MoS2 (black line) and InSe (red line).

The PL from 2D MoS2 is also observed at a much lower intensity than the InSe (shown in Fig. 1d). The PL response of exfoliated MoS2 on SiO2 is well documented and exhibits two excitonic features labeled AMoS2 and BMoS2 originating from the optical transitions at the K-point in the valence band, split by spin-orbit coupling, to the K-point in the conduction band50 with a contribution from defect-related emission at lower energy51,52. In this case, the integrated emission intensity of the AMoS2 excitons from the MoS2/InSe heterostructure is quenched by 92% relative to monolayer MoS2 on SiO2. PL quenching is commonly observed in both Type I and Type II band alignments and has been attributed to ultrafast energy or charge transfer between the heterostructure constituents12,53,54. As contact with InSe introduces a non-radiative charge/energy transfer channel in the MoS2/InSe heterostructure, the degree of quenching indicates that energy transfer must occur more than an order of magnitude faster than the lifetime of the AMoS2 exciton state (expected to be approximately 100 fs)55,56. The quenching mechanism is not apparent, however, due to the orthogonality of the dipole moments of MoS2 and InSe excitons (see Fig. 1a)49, direct, Förster-type resonant energy transfer is expected to be highly suppressed in this heterostructure. Other forms of energy or charge transfer likely dictate the optoelectronic properties of the MoS2/InSe heterostructure57.

While the PL from MoS2 becomes quenched, PL emission from InSe becomes enhanced by 80% in the MoS2/InSe heterostructure at 200 K (Fig. 1c). The simultaneous quenching of PL from MoS2 (the wider bandgap material in this structure) and enhancement of PL from InSe (the smaller bandgap material) is a characteristic signature of a Type I heterostructure. While a Type I band alignment in a monolayer MoS2/InSe heterostructure has been experimentally established, PL enhancement was not observed for InSe thicker than 50 nm purportedly due to variations in the band structure with thickness39. The heterostructure reported here utilizes InSe that is much thicker (>100 µm) yet still exhibits PL enhancement and the quenching/enhancement may be attributed to the rapid fabrication of a pristine heterostructure in an inert environment.

To better understand the interactions between MoS2 and InSe, a density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed utilizing a structural model that was constructed describing the 2D/bulk 2D heterostructure composed of a monolayer of MoS2 and a bilayer of InSe with the layer furthest from the MoS2 layer fixed to its bulk geometry spacings (additional information shown in Supplementary Fig. 2). As InSe exhibits a layer number-dependent band structure18,24, care must be taken to retain bulk-like InSe properties while also allowing the two atomic lattices (MoS2 and InSe) to relax at their interface. The resulting band structure and projected density of states (PDOS) for the MoS2-bilayer InSe heterostructure (see Fig. 1e) reveals that the conduction and valence states nearest the band gap are primarily composed of InSe orbitals (further details shown in Supplementary Fig. 5). Calculations also indicate weak interlayer coupling due to the interlayer distance of >3 Å between MoS2 and the bilayer of InSe, and little hybridization in the electronic orbitals at the valence (conduction) band maximum (minimum) (further information shown in Supplementary Fig. 5). A type I alignment is predicted between bulk InSe and monolayer MoS2 using accurate HSE calculations of the atomic band structure, with a transition between Types I and II as InSe thickness is reduced (additional information shown in Supplementary Fig. 6). Note that TMD/TMD heterostructures form mostly Type I heterostructures58.

Temperature-dependent photoluminescence

Photoluminescence characteristics of the heterostructure were further evaluated by temperature-dependent PL measurements performed from 300 K and 4 K. Figure 2a depicts the temperature-dependent PL emission between 1.5 and 1.9 eV with a general broad emission response between 1.5 eV and 1.8 eV due to defects within the MoS2, the AMoS2 emission around 1.9 eV, and a broad feature between 1.9 eV and 2.2 eV which comes from the InSe (additional information in Supplementary Section 8). In general, the A-exciton in MoS2 is highly quenched and blue-shifted in energy at lower temperatures in both the MoS2 on SiO2 and MoS2/InSe heterostructure, though at a very different rate. Changes in exciton peak energy can arise from differences in the electrostatic environment (electrostatic doping and screening), the lattice structure (built-in strain and thermal expansion), and electron-phonon coupling in MoS2 on different substrates. The effects of charge transfer and screening of the exciton binding energy are too small to be responsible for the large difference in AMoS2 exciton peak energy in the MoS2/InSe heterostructure and MoS2 on SiO2 (greater than 88 meV at 4 K) (additional information found in Supplementary Section 9). Thus, contact doping and screening cannot account for the large, measured difference between MoS2 PL peak energy on SiO2 and InSe. Similarly, the effect of the different thermal expansion coefficients of SiO2 and InSe can only account for 1.25% of the measured slope of \(\Delta E={E}_{\rm{InSe}}({A}_{{\rm{MoS}_2}})-{E}_{\rm{Si}{O}_{2}}({A}_{\rm{Mo}{S}_{2}})\) versus T shown in Fig. 2c (additional information found in Supplementary Section 10).

a Temperature-dependent PL spectra of MoS2/InSe (blue) and MoS2 on SiO2 (scaled by a factor of 0.025) (green). b Temperature dependence of AMoS2 peak energy (points) and FWHM (shaded area) for MoS2/InSe (blue) and MoS2/SiO2 (green). Dotted lines are fits to the O’Donnell-Chen model. c Peak energy difference between MoS2/InSe and MoS2/SiO2 plotted as a function of temperature and with a linear fit (red, dashed line) yielding a slope of −0.22 meV/K. d Quenching of AMoS2 PL intensity measured from MoS2 on InSe compared with MoS2 on SiO2.

The effect of electron-phonon coupling on semiconductor band gap size has been semi-empirically modelled by O’Donell and Chen which gives a metric for electron-phonon coupling strength and an effective phonon energy scale59. Fitting the temperature dependence of AMoS2 to this model (Fig. 2b, dotted lines) gives a larger electron-phonon coupling and smaller phonon energy scale for MoS2 on InSe than on SiO2 (additional information in Supplementary Section 11). These differences may arise because InSe provides an atomically smooth and electronically homogeneous substrate for MoS2, enhancing coherence and reducing scattering of phonons, or they can reflect the strong coupling of the MoS2 electrons to low energy phonons at the surface of InSe that modifies the MoS2 band gap.

In addition to the changes in band gap, temperature-dependent PL measurements also reveal a strong quenching of the AMoS2 exciton intensity relative to the MoS2 on SiO2 (Fig. 2d), from 92% at 300 K to 99% at 4 K, indicative of efficient charge and energy transfer due to an interface with minimal defects. The PL spectrum in the region of InSe emission (1.30–1.37 eV), shown in Fig. 3a, reveals several features associated with photoemission from InSe including the A exciton (1.346 eV), P-band (1.334 eV), and defect-related emission (1.315–1.33 eV), respectively18,47,60,61. The heterostructure emission peak location shows little difference between the InSe PL peak energies with and without 2D MoS2 on top. As this is a 2D/bulk material vdW junction, the electrostatic effects of the MoS2 layer on InSe are rapidly screened away from the vdW interface leading to only a small difference in AInSe emission energy (<1 meV) with MoS2 on top.

Defect trapping regime

Temperature-dependent PL shows defect peaks begin to emerge in the spectrum below the P-band energy at temperatures below 80 K (Fig. 3b and Fig. 4a). Below this temperature, AInSe excitons become captured by defects, reducing the bare PL intensity and increasing emission at lower energies62. Surprisingly, the bare AInSe exciton intensity increases with increasing temperature between 30 K and 80 K, that is, it exhibits negative thermal quenching (NTQ) (see Fig. 4b, inset). NTQ can be observed when defect-bound excitons or charges are thermally excited out of shallow defect-bound states63,64. Previous experimental studies of bulk InSe PL at low temperatures have analyzed these defect-bound states and have attributed them to several sources (oxygen defects, Se vacancies, stacking faults, surface-bound excitons, etc.) although these works do not report observations of NTQ65,66,67,68. Additionally, it has been argued that these defect states in bulk InSe form as a result of strong correlations and flat bands in InSe25,66,69.

a Integrated intensity for the P-band, AInSe, and all defect emission as a function of temperature with and without MoS2 (solid and hollow, respectively). Inset: Intensity ratio as a function of temperature of the AInSe intensity for MoS2/InSe compared to bare InSe. b Peak positions and c FWHM as a function of temperature for InSe emission with and without MoS2 (solid and hollow, respectively). d Energy level diagram of the excitonic states and transitions in the MoS2/InSe heterostructure. Colored arrows depict radiative decay pathways and hollow arrows depict non-radiative transition pathways.

Although NTQ of PL in InSe has not been observed before, Nicholas et al. also noted a defect-related transition in temperature-dependent cyclotron resonance measurements around 25 K70. Below 25 K an extended 2D defect state was observed, attributed to acceptor states at stacking faults, which transitions to a three dimensional state above this temperature. Additionally, a defect of selenium substituted with oxygen was chosen for investigation by DFT calculations due to its low formation energy. It is found that oxygen substitution does not induce significant band structure changes or mid-gap states (additional information found in Supplementary Fig. 10). This observation is corroborated experimentally by ARPES measurements before and after oxygen exposure71. Even though oxygen substituted selenium defects are found to not impact the electronic band structure, it is possible that isoelectronic defects induce large exciton-defect binding energies leading to exciton trapping as seen in similar semiconductor systems72. At this time the particular defect state(s) responsible for the observed behavior is not apparent from the experiments made in this work and further experimental and theoretical exploration is required.

Surprisingly, as the free exciton population varies rapidly below 80 K, there is no corresponding change in P-band intensity. As the P-band is typically attributed to exciton-exciton scattering, it is expected that the P-band emission intensity to be proportional to the free exciton concentration squared, as evidenced by power-dependence of peak intensity (see Supplementary Information)47,48. The insensitivity of the P-band intensity to the AInSe exciton density change with temperature and the decrease of P-band intensity with MoS2 on top suggests that the P-band in InSe is not solely due to exciton-exciton scattering within the InSe bulk.

Temperature-dependent PL enhancement

In the MoS2/InSe heterostructure, the AInSe exciton peak intensity is larger by 25–81% between 100 K and 250 K suggesting that the MoS2 enhances AInSe emission through charge and/or energy transfer. Below approximately 80 K, the effect of the MoS2/InSe heterostructure becomes more apparent. While the PL intensity of the AInSe state drops dramatically for the bare InSe surface, the AInSe intensity from the MoS2/InSe region remains significantly larger (as much as 44×) and the transition temperature between regular thermal quenching and NTQ regimes increases to higher temperature. The apparent enhancement in this temperature regime is coincident with the onset of defect-induced quenching of AInSe exciton emission and the emergence of defect-related PL at low temperatures (Figs. 3b and 4a). Not only does the NTQ effect correlate with the defects in InSe, the MoS2 appears to alleviate much of the defect-induced quenching of the AInSe emission. Below 30 K, the defect and P-band intensities are both smaller in the heterostructure region. The origins of the P-band and defect-bound exciton states are not yet understood, and more work is needed to investigate the interactions of excitons and defects in InSe. As such, it is difficult to speculate on how the addition of the MoS2 monolayer reduces the P-band intensity and defect emission below 30 K. It is probable that, as MoS2 is inert in ambient conditions, it protects the bare InSe surface from chemical interactions with the environment in the time between sample fabrication and measurement. Additionally, contact doping as well as photoinduced carriers or excitons may contribute to the passivation of defect centers in InSe. The ratio of integrated intensity of the AInSe peak with and without MoS2 (\({I}_{\rm{Mo}{S}_{2}}({A}_{\rm{InSe}})/{I}_{\rm{bare}}({A}_{\rm{InSe}})\)) is shown in the inset of Fig. 4a and summarizes the effect of the MoS2 in the heterostructure. Between 100 K and room temperature, the AInSe peak intensity is larger for the MoS2/InSe heterostructure with little variation with temperature, despite a large change in MoS2 bandgap size. As the temperature approaches the defect binding regime, the exciton intensity ratio fluctuates while below ~60 K, it rises to a peak value of 44 revealing the strong influence of MoS2 on enhancing AInSe emission.

Estimation of time scales

Fits of the Lorentzian linewidth of the AInSe exciton peak and P-band to a phenomenological phonon-coupling model reveal a very small effect of acoustic phonon scattering at low temperature. Excitonic relaxation in InSe is mediated by optical and zone-edge acoustic phonons both with and without MoS2. For MoS2 on InSe, AMoS2 emission linewidth is observed to be linear with temperature indicating that exciton interactions with acoustic phonons primarily dictate the linewidth broadening, in agreement with the peak energy analysis above. As the temperature approaches zero, the AInSe peak linewidth approaches \({\gamma }_{0}=1.45\,{\rm{meV}}\) corresponding to a coherence time of \({\tau }_{\rm{InSe}}=\frac{\hslash }{{\gamma }_{0}}=0.45\,{\rm{ps}}\), much smaller than the 9.5 ns value reported in the literature73. To confirm, time-resolved PL measurements at 4 K (further information in Supplementary Fig. 12) find that the AInSe lifetime is far less than this value while the lifetime of defect-bound excitons is comparable to 9.5 ns. This suggests that in bare InSe, AInSe excitons or charges are rapidly captured by defects (in less than 250 ps, see Supplementary Section 13) and that spectrally overlapping signals from AInSe exciton and defect-related photoemission at higher temperatures could lead to an overestimation of the AInSe exciton lifetime. Compared to bulk InSe, excitons in monolayer MoS2 have exceptionally large binding energies and ultrafast formation timescales74. Additionally, our DFT calculations show no interlayer potential which might separate charges. Thus, most AMoS2 excitons form on the order of tens of femtoseconds within the MoS2 layer. Upon transit to bulk InSe (<12 ps), the exciton then thermalizes through interactions with phonons into the AInSe state before either radiative recombination, phonon-assisted non-radiative recombination, or defect trapping (<1 ps)75. Thus, without defect trapping, we estimate that the entire process of energy funneling from MoS2 to InSe and the subsequent emission of light at the AInSe energy is ultrafast (<250 ps).

Discussion

Future optoelectronic devices harnessing the impressive versatility of 2D/2D and 2D/3D van der Waals heterostructures require an improved understanding of how defects, band structures, and excitons influence charge/energy transfer and resultant optical properties. In this work, a heterostructure of monolayer MoS2 and bulk InSe was fabricated and shown to be a Type I heterostructure with a large enhancement of InSe excitonic emission compared to monolayer MoS2/thinner InSe heterostructures. Temperature-dependent PL revealed that bulk InSe exciton emission intensity was highly sensitive to native defects which may accumulate due to exposure to the atmosphere. In the monolayer 2D MoS2/bulk InSe heterostructure, degradation of the InSe surface was minimal as MoS2 passivated the surface and prevented oxidation. This enhancement also resulted in a quenching of the MoS2 PL by more than 98% at 4 K. Interestingly, the A exciton in InSe was enhanced substantially at temperatures below 60 K, coinciding with the onset of defect-induced quenching of the AInSe exciton emission at low temperatures. Finally, we demonstrate ultrafast transport between the two layers, where the entire energy funneling occurs at sub 250 ps. This study suggests the use of 2D MoS2 as both a passivation layer and as a strong light-to-charge converter when combined into a Type I heterostructure with InSe, enabling utility for optoelectronic applications such as photodetectors, light emitters, and color converters.

Methods

InSe crystal growth

Nominally undoped γ-phase InSe single crystals were grown by the vertical Bridgman method using a non-stoichiometric polycrystalline In1.04Se0.96 charge. The InSe charge was vacuum-sealed in a graphitized quartz ampoule. The melt was equilibrated at 720 °C for several hours, and then the ampoule was translated across a temperature gradient at a rate of 0.5 mm/h. The γ-phase of InSe used in this study has been unambiguously confirmed by X-ray diffraction and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements and the stoichiometric composition of InSe crystals was confirmed by TEM/EDX and SEM/EDX measurements as reported in our previous paper24.

Heterostructure fabrication

MoS2 flakes are exfoliated from bulk (2D Semiconductors) onto a freshly prepared PDMS stamp (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning). Monolayers are first identified with optical contrast and later verified with PL and Raman measurements. Bulk pieces of γ-phase InSe (>100 μm thick), affixed to a substrate, are freshly cleaved with tape and the chosen MoS2 monolayer is quickly placed onto the InSe surface inside an Ar-filled glovebox (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for images). The vdW interactions between MoS2 are stronger than the PDMS-MoS2 bond and the MoS2 layer remains with the InSe crystal when PDMS is removed, resulting in a dry transfer. Optical images of several samples are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Only regions with optically smooth interfaces, fabricated in an Ar atmosphere, are reported here. MoS2 on SiO2 is fabricated by exfoliating a monolayer from bulk directly onto the 300 nm SiO2 on Si substrate using tape.

Raman and room temperature PL

Room temperature Raman and PL spectra were collected using a Renishaw inVia Raman spectrometer. The 514.5 nm excitation was focused on the heterostructures through a 100× objective lens, and Raman and PL spectra were collected by setting the laser power to a few hundred microwatts (to prevent burning by the laser) and using a collection time of 10 s for a minimum of 3 acquisitions.

Temperature-dependent PL

The sample was loaded into a Montana Instruments S200 Cryostation and cooled down to 4 K. Varying the temperature was performed via an agile temperature sample mount (ATSM, Montana Instruments) which contains a resistive heater and temperature sensor allowing for precise target temperatures to be achieved. The heterostructure was excited using a tunable 120 fs, 80 MHz Ti:Sapphire laser centered at 580 nm through a 0.75 NA in-situ objective. The resulting emission was collected and dispersed in a grating spectrometer (Princeton Instruments, SP-2750) and analyzed using a PyLoN BRX silicon CCD camera. For the time-resolved PL measurements, the emission was passed through a tunable short- and long-pass filter to select the wavelength range of interest prior to the spectrometer. The corresponding signal was sent to a single photon avalanche diode (MPD) for photon counting. The timing information was then obtained via a PicoQuant HydraHarp 400 event timer resulting in the time-resolved PL measurement. Additionally, TRPL measurements were performed using a Universal Streak Camera (Hamamatsu,C10910-04) providing an improved instrument response function allowing for the reduction of the upper bound for resolution-limited lifetime.

DFT calculation

DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package76,77,78. Core electrons are described using the projector-augmented wave method79,80. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)81 was employed, including a correction for van der Waals (vdW) interactions by the D3 parametrization (vdW-D3)82. The relaxation of each structure involves optimizing the lattice parameters and the internal positions of the atoms using conjugate-gradient algorithms83. To mimic the InSe bulk, the atomic positions of one of the InSe layers were fixed at the bulk geometry during the relaxation (additional information shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). The system’s total energy and lattice parameters were determined once the unit cell was fully relaxed. Total energy convergence during all self-consistent calculations was achieved when the difference in the total energy between steps was less than 0.01 meV. Memory constraints limited the energy cutoff and Monkhorst-Pack84 mesh of k-points to an energy cutoff of 300 eV and a k-point density of 14 points per Å for our heterostructure calculations. An energy cutoff of 400 eV was used for all monolayer calculations. Spin-orbit coupling was not used. For accurate band structure calculations, we utilized the Heyd-Scuderia-Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional85, using the relaxed PBE+vdW-D3 structure as a starting point.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Castellanos-Gomez, A. et al. Van Der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Rev. Methods Primer 2, 58 (2022).

Kanungo, S., Ahmad, G., Sahatiya, P., Mukhopadhyay, A. & Chattopadhyay, S. 2D materials-based nanoscale tunneling field effect transistors: current developments and future prospects. Npj 2D Mater. Appl. 6, 83 (2022).

Khan, S. et al. 2D heterostructures for highly efficient photodetectors: from advanced synthesis to characterizations, mechanisms, and device applications. Adv. Photonics Res. 3, 2100342 (2022).

Liu, R. et al. Band alignment engineering in two‐dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide‐based heterostructures for photodetectors. Small Struct 2, 2000136 (2021).

Parker, M. Heterostructures make light work of photodetection. Nat. Electron. 5, 257–257 (2022).

Idisi, D. O. & Mwakikunga, B. Two-dimensional layered metal dichalcogenides-based heterostructures for solar cells applications: a review. Sol. Energy 263, 111981 (2023).

Molaei, M. J., Younas, M. & Rezakazemi, M. Van Der Waals heterostructures in ultrathin 2D solar cells: state-of-the-art review. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 285, 115936 (2022).

Furchi, M. M. et al. Device physics of van Der Waals heterojunction solar cells. Npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2, 3 (2018).

Kennes, D. M. et al. Moiré heterostructures as a condensed-matter quantum simulator. Nat. Phys. 17, 155–163 (2021).

Regan, E. C. et al. Emerging exciton physics in transition metal dichalcogenide heterobilayers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 778–795 (2022).

Shabani, S. et al. Deep Moiré potentials in twisted transition metal dichalcogenide bilayers. Nat. Phys. 17, 720–725 (2021).

Ceballos, F., Bellus, M. Z., Chiu, H.-Y. & Zhao, H. Ultrafast charge separation and indirect exciton formation in a MoS2–MoSe2 van Der Waals heterostructure. ACS Nano 8, 12717–12724 (2014).

Jin, C. et al. Ultrafast dynamics in van Der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 994–1003 (2018).

Pham, P. V. et al. 2D heterostructures for ubiquitous electronics and optoelectronics: principles, opportunities, and challenges. Chem. Rev. 122, 6514–6613 (2022).

Kim, S. et al. Graphene-GaN Schottky diodes. Nano Res. 8, 1327–1338 (2015).

Yin, Y. et al. High‐speed and high‐responsivity hybrid silicon/black‐phosphorus waveguide photodetectors at 2 Μm. Laser Photonics Rev. 13, 1900032 (2019).

Wan, X. et al. A self-powered high-performance graphene/silicon ultraviolet photodetector with ultra-shallow junction: breaking the limit of silicon? Npj 2D Mater. Appl. 1, 4 (2017).

Bandurin, D. A. et al. High electron mobility, quantum hall effect and anomalous optical response in atomically thin InSe. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 223–227 (2017).

Song, S. et al. Wafer-scale growth of two-dimensional, phase-pure InSe. Matter 6, 3483–3498 (2023).

Miao, J. et al. Heterojunction tunnel triodes based on two-dimensional metal selenide and three-dimensional silicon. Nat. Electron. 5, 744–751 (2022).

Jiang, J., Xu, L., Qiu, C. & Peng, L.-M. Ballistic two-dimensional InSe transistors. Nature 616, 470–475 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Efficient carrier multiplication in self-powered near-ultraviolet γ-InSe/graphene heterostructure photodetector with external quantum efficiency exceeding 161. Nano Lett. 24, 7252–7260 (2024).

Liu, W. et al. Self-powered and broadband opto-sensor with bionic visual adaptation function based on multilayer γ-InSe flakes. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 180 (2023).

Pike, N. A. et al. Understanding the origin and implication of the indirect-to-direct bandgap transition in multilayer InSe. J. Phys. Chem. C 128, 7957–7967 (2024).

Pasquale, G. et al. Flat-band-induced many-body interactions and exciton complexes in a layered semiconductor. Nano Lett. 22, 8883–8891 (2022).

Pasquale, G. et al. Electrical detection of the flat-band dispersion in van der waals field-effect structures. Nat. Nanotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-023-01489-x (2023).

Liang, Y. et al. Strong exciton–exciton scattering of exfoliated van Der Waals InSe toward efficient continuous-wave near-infrared P-band emission. Nano Lett. 23, 4058–4065 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Room-temperature near-infrared excitonic lasing from mechanically exfoliated InSe microflake. ACS Nano 16, 1477–1485 (2022).

Yao, Y.-T. et al. High-responsivity photodetectors made of indium selenide with visible to near-infrared photodetection. Chin. J. Phys. 90, 839–845 (2024).

Tamalampudi, S. R. et al. High‐speed waveguide‐integrated InSe photodetector on SiN photonics for near‐infrared applications. Adv. Photonics Res. 4, 2300162 (2023).

Yang, H.-W. et al. Ultraefficient ultraviolet and visible light sensing and Ohmic contacts in high-mobility InSe nanoflake photodetectors fabricated by the focused ion beam technique. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 5740–5749 (2018).

Jiang, J. et al. Stable InSe transistors with high-field effect mobility for reliable nerve signal sensing. Npj 2D Mater. Appl. 3, 1–8 (2019).

Arora, H. et al. Effective hexagonal boron nitride passivation of few-layered InSe and GaSe to enhance their electronic and optical properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 43480–43487 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Optoelectronic gas sensor based on few-layered InSe nanosheets for NO2 detection with ultrahigh antihumidity ability. Anal. Chem. 92, 11277–11287 (2020).

Yang, F.-S. et al. Oxidation-boosted charge trapping in ultra-sensitive van Der Waals materials for artificial synaptic features. Nat. Commun. 11, 2972 (2020).

Dai, M. et al. Properties, synthesis, and device applications of 2D layered InSe. Adv. Mater. Technol. 7, 2200321 (2022).

Shu, Y. et al. 2D BP/InSe heterostructures as a nonlinear optical material for ultrafast photonics. Nanomaterials 12, 1809 (2022).

Liao, L. et al. InSe:Ge-doped InSe van Der Waals heterostructure to enhance photogenerated carrier separation for self-powered photoelectrochemical-type photodetectors. Nanoscale 14, 5412–5424 (2022).

Sun, Z. et al. Tailoring the energy funneling across the interface in InSe/MoS2 heterostructures by electrostatic gating and strain engineering. Adv. Opt. Mater. 9, 2100438 (2021).

Claro, M. S. et al. Van Der Waals heteroepitaxy of GaSe and InSe, quantum wells, and superlattices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2211871 (2023).

Xu, B. et al. Charge transfer at the hetero‐interface of WSe2/InSe induces efficient doping to achieve multi‐functional lateral homo‐junctions. Adv. Electron. Mater. 7, 2100584 (2021).

Lei, T. et al. Ambipolar photoresponsivity in an ultrasensitive photodetector based on a WSe 2/InSe heterostructure by a photogating effect. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 50213–50219 (2021).

Yan, Y. et al. Reversible half wave rectifier based on 2D InSe/GeSe heterostructure with near‐broken band alignment. Adv. Sci. 8, 1903252 (2021).

Nüsse, S. et al. Femtosecond coherent polariton dynamics in the layered III-VI semiconductor InSe. Phys. Rev. B 55, 4620–4627 (1997).

Bergeron, A., Gradziel, C., Leonelli, R. & Francoeur, S. Probing hyperbolic and surface phonon-polaritons in 2D materials using Raman spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 14, 4098 (2023).

Chae, W. H., Cain, J. D., Hanson, E. D., Murthy, A. A. & Dravid, V. P. Substrate-induced strain and charge doping in CVD-grown monolayer MoS2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 143106 (2017).

Shubina, T. V. et al. InSe as a case between 3D and 2D layered crystals for excitons. Nat. Commun. 10, 3479 (2019).

Klingshirn, C. The luminescence of ZnO under high one‐ and two‐quantum excitation. Phys. Status Solidi B 71, 547–556 (1975).

Brotons-Gisbert, M. et al. Out-of-plane orientation of luminescent excitons in two-dimensional indium selenide. Nat. Commun. 10, 3913 (2019).

Mak, K. F. & Shan, J. Photonics and optoelectronics of 2D semiconductor transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Photonics 10, 216–226 (2016).

Manzeli, S., Ovchinnikov, D., Pasquier, D., Yazyev, O. V. & Kis, A. 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17033 (2017).

Mueller, T. & Malic, E. Exciton physics and device application of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide semiconductors. Npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2, 29 (2018).

Hong, X. et al. Ultrafast charge transfer in atomically thin MoS2/WS2 heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 682–686 (2014).

Chen, H. et al. Ultrafast formation of interlayer hot excitons in atomically thin MoS2/WS2 heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 7, 12512 (2016).

Selig, M. et al. Excitonic linewidth and coherence lifetime in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 7, 13279 (2016).

Chan, Y. et al. Exciton lifetime and optical line width profile via exciton–phonon interactions: theory and first-principles calculations for monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 23, 3971–3977 (2023).

Hu, Z. et al. Interfacial charge and energy transfer in van Der Waals heterojunctions. InfoMat 4, e12290 (2022).

Özçelik, V. O., Azadani, J. G., Yang, C., Koester, S. J. & Low, T. Band alignment of two-dimensional semiconductors for designing heterostructures with momentum space matching. Phys. Rev. B 94, 035125 (2016).

O’Donnell, K. P. & Chen, X. Temperature dependence of semiconductor band gaps. Appl. Phys. Lett. 58, 2924–2926 (1991).

Camassel, J., Merle, P., Mathieu, H. & Chevy, A. Excitonic absorption edge of indium selenide. Phys. Rev. B 17, 4718–4725 (1978).

Balakrishnan, N. et al. Room temperature electroluminescence from mechanically formed van Der Waals III-VI homojunctions and heterojunctions. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2, 1064–1069 (2014).

Geng, J. et al. Unusually strong near‐infrared photoluminescence of highly transparent bulk InSe flakes. Adv. Funct. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202413672 (2024).

Shibata, H. Negative thermal quenching curves in photoluminescence of solids. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 37, 550 (1998).

Reshchikov, M. A. Mechanisms of thermal quenching of defect‐related luminescence in semiconductors. Phys. Status Solidi A 218, 2000101 (2021).

Gouskov, A., Camassel, J. & Gouskov, L. Growth and characterization of III–VI layered crystals like GaSe, GaTe, InSe, GaSe1-xTex and GaxIn1-xSe. Prog. Cryst. Growth Charact. 5, 323–413 (1982).

Kress-Rogers, E., Nicholas, R. J., Portal, J. C. & Chevy, A. Cyclotron resonance studies on bulk and two-dimensional conduction electrons in InSe. Solid State Commun. 44, 379–383 (1982).

Shi, L. et al. Oxidation mechanism and protection strategy of ultrathin indium selenide: insight from theory. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 4368–4373 (2017).

Wang, R. et al. Unveiling the stimulated robust carrier lifetime of surface‐bound excitons and their photoresponse in InSe. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 6, 1900171 (2019).

Abha & Warrier, A. V. R. Photoluminescence studies on the layer semiconductor InSe. J. Appl. Phys. 53, 5169–5171 (1982).

Nicholas, R. J., Kress-Rogers, E., Portal, J. C., Galibert, J. & Chevy, A. Two-dimensional behaviour due to electrons bound at defects in InSe. Surf. Sci. 113, 339–346 (1982).

Politano, A. et al. Indium selenide: an insight into electronic band structure and surface excitations. Sci. Rep. 7, 3445 (2017).

Baldereschi, A. & Hopfield, J. J. Binding to isoelectronic impurities in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 28, 171–174 (1972).

Manjón, F. J. et al. Band structure of indium selenide investigated by intrinsic photoluminescence under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 70, 125201 (2004).

Trovatello, C. et al. The ultrafast onset of exciton formation in 2D semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 11, 5277 (2020).

Zhong, C. et al. Hot carrier and surface recombination dynamics in layered InSe crystals. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 493–499 (2019).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 48, 13115–13118 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Freysoldt, C., Boeck, S. & Neugebauer, J. Direct minimization technique for metals in density functional theory. Phys. Rev. B 79, 241103 (2009).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-Zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Acknowledgements

M.A., M.S., and N.G. acknowledges support from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under award number FA9550-24RYCOR011. J.R.H. acknowledges support from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under award number FA9550-20RYCOR059 and FA9550-25RYCOR006. The research performed by C.E.S. at the Air Force Research Laboratory was supported by contract award FA807518D0015. D.J. acknowledges support for this work from the Asian Office of Aerospace Research and Development (AOARD) of the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) FA2386-21-1-4063 and from the AFOSR GHz-THz program FA9550-23-1-0391. Certain commercial equipment, instruments, software, or materials are identified in this paper in order to specify the experimental procedure adequately. Such identifications are not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by NIST nor it is intended to imply that the materials or equipment identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.A. performed sample fabrication, optical measurements, interpreted data and drafted manuscript. C.E.S. performed optical measurements and data analysis. N.A.P. performed DFT calculations and analysis. R.P. aided in the DFT analysis and interpretation. S.K. grew InSe crystals. A.V.D. grew and characterized InSe crystals. J.R.H. aided in the optical measurement analysis. R.R. aided in the PL measurements and analysis. D.J. interpreted the optical data. M.S. interpreted and analyzed data as well as finalized drafting manuscript. N.R.G. provided data analysis, project guidance, and paper review and editing. All authors have contributed to writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Altvater, M.A., Stevens, C.E., Pike, N.A. et al. Efficient energy transfer and photoluminescence enhancement in 2D MoS2/bulk InSe van der Waals heterostructures. npj 2D Mater Appl 9, 31 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00549-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00549-1