Abstract

Isotope-enriched bulk hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) crystals have enhanced properties that improve the performance of nanophotonic and quantum technologies. Developing methods to deposit epitaxial layers on such crystals enables the exciting prospects of producing isotope-engineered hBN layers and heterostructures. Here, we demonstrate the homoepitaxial growth of hBN with phase-separated 10B and 11B isotopes by high-temperature molecular beam epitaxy (HT-MBE). Controlled nucleation, improved surface uniformity, and step-flow growth of an h10BN epilayer were achieved by etching the h11BN bulk crystals with molecular hydrogen. The alignment of the h10BN epilayer and host h11BN lattices was confirmed by lattice-resolved atomic force microscopy. Micro-Raman spectroscopy and scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscopy show that the bulk h11BN and h10BN epilayer have distinct phonon energies, with no intermixing of the van der Waals layers, thus enabling the different boron isotopes to be spatially separated in the heterostructure. This work demonstrates the potential of HT-MBE to produce isotopic heterostructures of hBN to advance future nanophotonic and quantum technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interest in hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) is rapidly increasing due to its unique electronic and optical properties, which have the potential to advance photonic and quantum technologies. As a wide bandgap semiconductor (~6 eV), it has potential as a deep-UV emitter1,2,3, and can host a variety of optically active defects that act as quantum emitters at room temperature4,5,6, some of which are magnetically addressable7,8,9. While the hexagonal polytype (AA’ stacked) is the most widely studied, sp2-hybridised BN can exist in metastable hexagonal (AA stacked), Bernal (AB stacked), or rhombohedral (ABC stacked) phases10,11,12. Such changes in the stacking order break the inversion symmetry present in AA’ hBN, altering its optical response (e.g., introducing nonlinearity)10,11,13, as well as separating the dipole moments of B-N pairs leading to piezoelectricity and ferroelectricity14,15,16,17.

Recently, isotope-enriched hBN crystals have proven beneficial for a variety of applications. For example, the high thermal neutron absorption cross-section of the 10B isotope and its transmutation to charge particles is useful for detecting neutrons18,19. The reduced masses of hBN change when enriched with 10B, 11B, 14N and 15N isotopes, which significantly impacts its phonon modes20,21, leads to improved thermal conductivity22,23,24, and enables hyperbolic phonon polariton dispersions engineered by isotope selection in van der Waals (vdW) structures25,26,27. Furthermore, the combination of 10B and 15N isotopes in h10B15N increases coherence times for the VB- spin defect compared to hBN with natural isotope abundances28,29. Despite these many recent advances, isotopically enriched hBN remains available primarily in the form of millimetre-sized bulk crystals20,30,31. Therefore, practically all engineered vdW isotopic heterostructures have been produced by mechanically stacking flakes exfoliated from hBN crystals enriched with different boron isotopes, where the monoisotopic building blocks are multilayers and thin slabs25. Developing scalable methods to deposit isotopically-enriched hBN layers to produce heterostructures and superlattices with tailorable and contamination-free isotope interfaces is imperative for practical device applications.

Several approaches to wafer-scale growth of hBN thin films have been developed in recent years, including chemical vapour deposition (CVD) on metals32,33,34,35,36, metal-organic vapour-phase epitaxy (MOVPE)11,12,37,38 and high-temperature molecular beam epitaxy (HT-MBE)39,40,41,42,43. In material systems with established bulk crystal growth, homoepitaxy is used to grow thin films with higher quality than their bulk counterparts. The homoepitaxial growth of hBN has remained largely unexplored due to the limited availability of bulk hBN crystals, but there have been recent demonstrations of homoepitaxial growth of hBN on exfoliated hBN flakes by MOVPE44, and polycrystalline sp2-hybridised BN growth on polished pyrolytic BN (pBN) by CVD45. Of the currently available epitaxial growth methods, HT-MBE is distinctly advantageous for growing monoisotopic hBN, due to the readily available isotope-enriched elemental boron and nitrogen precursors.

Here we demonstrate the growth of vdW and lateral structures containing hBN layers with phase-separated 10B and 11B isotopes by homoepitaxial HT-MBE of h10BN layers on h11BN flakes exfoliated from isotopically-enriched bulk crystals31. Through a comprehensive analysis of the growth using atomic force microscopy (AFM), we show that the homoepitaxy of hBN proceeds by step-flow growth, requiring pre-treatment of exfoliated hBN by H2-etching to create monolayer step edges and promote nucleation. Using micro-Raman spectroscopy (μ-RS) and scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscopy (s-SNOM), we confirm the epitaxy of phase-separated h10BN layers, which opens prospects for practical isotope-engineered infrared nanophotonic devices and quantum technologies requiring spatial separation of nuclear spins.

Results

Molecular beam epitaxy of isotopically enriched BN

To study 10B and 11B isotopically enriched epitaxy, we first separately grew BN layers on sapphire substrates by HT-MBE1,2,41 and explored the ratio of 10B to 11B using secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS). Figure 1 shows SIMS depth profiles of 10B and 11B of BN layers grown with a NatB source, comprising a naturally abundant boron isotope mixture (Fig. 1a), and isotopically enriched 10B and 11B sources (Fig. 1b and 1c, respectively). In the NatBN layers, the layers contained 78 ± 1% 11B and 22 ± 1% 10B, close to the naturally occurring abundance of 11B (80.1%) and 10B (19.9%). In the cases of the isotope-enriched B sources, we find isotope purities of 94.3 ± 0.8% and 99.3 ± 0.1% for layers grown from 10B and 11B sources, respectively, with no substantial variations as a function of the thickness of the layers. These values are broadly in line with the quoted isotope purity of the source material (see Experimental Details), noting that these values are subject to instrumental uncertainties due to the unavailability of a suitable calibration sample (see Supplementary Information for further discussion).

We demonstrated previously that during plasma-assisted MBE of AlGaN layers, there is unintentional doping of the layers with boron due to decomposition of the pBN parts of nitrogen RF plasma sources46. In order to check for any influence of such pBN decomposition on the isotopic purity of boron in our layers, we separately grew pure boron layers under similar MBE growth conditions in the absence of the nitrogen RF plasma source. SIMS studies demonstrate that the ratio of 10B and 11B isotopes in these layers remains practically the same with or without RF plasma source operation (see Fig. S1 and Table S1, Supplementary Information). Therefore, the influence of decomposition of pBN parts on the isotopic purity of our layers is negligible, and any isotopic impurities introduced from the RF plasma source can be considered in the doping regime and are below the sensitivity of the SIMS measurements. The ratio of 10B and 11B isotopes in the layers is controlled mainly by the isotopic purity of the initial boron source material.

Homoepitaxial growth of hBN

Next, we turn our attention to homoepitaxial growth of h10BN layers on h11BN crystals. Figure 2a–d shows atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of h10BN monolayers grown on exfoliated h11BN flakes mounted on sapphire as a function of growth time (1–6 h). The hBN flake morphology after growth is dominated by wrinkles formed during post-growth cooling (seen most clearly in Fig. 2d). These form due to the mismatch in thermal expansion coefficient between hBN and the sapphire substrate47. Because the structure of h10BN layers is nearly identical to h11BN, we search for the epilayers by identifying regions that are topographically atypical to exfoliated single crystal hBN flakes. Typically, the h10BN grows in small grains on the surface with mono- or few-layer thickness, and sometimes contains defects such as grain boundaries, or clusters of material on the surface, e.g., in Fig. 2e. Across numerous flakes and samples, there are occasionally hexagonal monolayer islands of h10BN nucleating on the surface, accompanied by a 3D defect in the centre of the island. An example of this is shown in Fig. 2f, with the tip height profile across the island shown in Fig. 2g, indicating monolayer thickness with 0.36 nm step height43. Precise identification of the object at the centre of the island is not possible by AFM; however, the height of the defect is 0.30 nm (less than the hBN layer thickness), suggesting it is some form of 3D cluster acting as a nucleation centre rather than the early growth of a second h10BN layer. After surveying multiple flakes on each sample, we frequently observed atomically flat surfaces of h11BN with a low density of structural defects, which limits the nucleation of the HT-MBE layer. Broadly, the growth of h10BN is both flake- and time-dependent, i.e., the nucleation, and hence coverage, of h10BN strongly depends on the initial flake topography. This is due to the nucleation being primarily at step edges on the surface, which are formed uncontrollably during hBN exfoliation. This effect is exemplified in Fig. 2d where, despite the longest growth time (6 h), the lack of steps or surface defects resulted in almost no h10BN growth.

Tapping mode AFM images of h10BN epilayers grown on exfoliated h11BN flakes for a 1 hr, b 2 hr, c 4 hr, d 6 hr. These images show the amplitude error signal, which improves step edge contrast against the flake morphology. e AFM topography of multilayer h10BN around defects. f AFM topography of an isolated h10BN island. The tip height profile from left to right along the dashed line is shown in (g). Scales bars are: a–c 500 nm, d 3 μm, e 400 nm, f 200 nm.

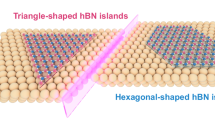

Next, we tested H2-etching the h11BN surfaces (see Experimental Methods) to increase the step edge density on the surface and thus the nucleation density. Representative AFM images of the h11BN surface after H2-etching are shown in Fig. 3a, b. The etching typically creates monolayer-deep pits in the surface with, occasionally, additional etching through subsequent hBN layers, shown in the tip height profile in Fig. 3c. The smallest pits have a sharp triangular shape with edges oriented along the zigzag lattice directions, as revealed by lattice-resolved contact-mode AFM imaging on the top layer. Previously, these have been proposed to be B-terminated edges when hBN monolayers on CuNi foils are etched in a H2/Ar atmosphere, and N-terminated edges when etched in H2 and N2, respectively48; however, this may differ in our work due to the use of bulk flakes and a non-catalytic substrate. Etching of the second layer also forms zigzag-oriented edges with the triangular pits rotated by 60° with respect to those in the first layer, reflecting the AA’ stacking in hBN (black dashed triangles in Fig. 3b). As the etching of the surface continues, the edges of the pits become rounded and do not follow any crystallographic orientation.

a, b Tapping mode AFM images showing the surface of a h11BN flake after H2-etching at 1000 °C for 8 h in flowing (0.15 slpm) 5% H2/Ar. The inset of (b) shows a lateral force microscopy (LFM) image of the hBN lattice on the top layer of the flake, and the black arrows indicate the h11BN lattice directions. The black dashed triangles reflect the 60° rotation between layers. c Tip height profile taken from left to right along the dashed line in (b). d–f AFM images of the surface of etched h11BN flakes after HT-MBE of h10BN for 2 hr, 4 hr and 6 hr, respectively. The inset in (d) shows a magnified view to highlight the faceted edges of the h10BN epilayer. Scale bars are a 4 μm, b 400 nm, d, e 1 μm, f 2 μm.

The evolution of non-faceted pits indicates that etching follows a non-equilibrium, dynamic process reminiscent of the growth of monolayer hBN islands by chemical vapour deposition (CVD) on metal surfaces. In the case of crystal growth under near-equilibrium conditions, the island shape will follow kinetic Wulff construction, resulting in triangular or truncated triangular islands depending on the boron and nitrogen precursor flux ratio36,49,50. At high precursor flux (non-equilibrium growth conditions), hBN islands grow with convex edges due to dynamic growth processes in which the attachment of adatoms to edge structures occurs at a comparable or higher rate than relaxation of the edge structure. We, therefore, propose that the H2-etching process seen here is also occurring under non-equilibrium conditions. Etch pits initially form a triangular shape with zigzag-oriented edges, as shown in Fig. 3b, and expand with convex edges due to the etch rate exceeding the relaxation of a zigzag edge. Importantly, the largest etch pits do not evolve into a hexagonal shape, nor form edges oriented along the armchair lattice directions. This supports the hypothesis of non-equilibrium etching conditions rather than an evolution towards armchair-terminated edges, which is typically the most favourable edge termination for hBN51.

Figure 3d–f show topographic AFM images of h10BN epilayers grown on the H2-etched h11BN flakes with increasing HT-MBE growth time. In contrast to growth on pristine h11BN flakes, HT-MBE of h10BN layers on the etched surface results in much more uniformly distributed growth, confirming that step edges play an important role in nucleation. Variations between flakes remain and reflect a flake-to-flake non-uniformity of the etched surfaces. For example, the nucleation density in Fig. 3d appears much higher than in Fig. 3f, although we cannot exclude the possibility that etched pits are completely over-grown after prolonged growth periods. In all instances, there are isolated hexagonal islands of monolayer thickness on the surface. As a function of time, the lateral size of isolated h10BN islands increases approximately linearly at a rate of ~130 ± 10 nm hr−1 (see Fig. S2, Supplementary Information).

Next, we examine the homoepitaxial growth modes and epitaxial relationship between the h10BN epilayer and h11BN substrate. Figures 4a and 4b shows tapping mode AFM phase contrast and topography, respectively, of a H2-etched surface after 4 h growth. Note that the boron isotope provides phase contrast to distinguish between 10B and 11B isotopes in hBN, which appear as smaller and larger phase shifts, respectively in Fig. 4a. This is probably due to the difference in the mechanical properties of the h10BN and h11BN layers52, although we note differences in the vdW interactions between the flake and grown layers may also contribute53. In addition to the growth of hexagonal h10BN islands nucleating at terrace defects, we also observe step-flow growth from the etched h11BN edges. This is consistent with previous observations of step-flow growth of hBN from monolayer step edges on HOPG42,43. h10BN islands also nucleate on the upper terrace of a h11BN step edge, as indicated by the white arrows in Fig. 4b. It is not clear whether these islands are h10BN bilayers formed where the step flow growth is pinned by a 3D defect (e.g., a boron aggregate), or monolayer growing on the upper terrace of a h11BN step edge.

a Tapping mode AFM phase and b topography of h10BN grown on H2-etched h11BN for 4 h. c–e Lateral force microscopy (LFM) images of the hBN lattice acquired at the blue, green and pink points, respectively, indicated in (a). The lattice contrast has been enhanced by 2D-FFT filtering. Note that the LFM images are scanned at a 90° angle relative to the tapping mode image in (a). This corresponds to a scan direction perpendicular to the length of the cantilever, which maximises the lateral force signal. Scale bars are a, b 1 μm, c–e 2 nm.

Close inspection of facetted h10BN edges shows that the majority of the grown islands and step-flow growth fronts share a common orientation, marked by the white dashed lines in Fig. 4b, indicating a homoepitaxial growth relation of the h10BN layer to h11BN. To determine the atomic registry of the grown layer with the underlying h11BN we have examined the local orientation of the hBN lattices by lateral force microscopy (LFM). Figure 4c–e shows lattice-resolved LFM images of the hBN surface at three locations marked by the coloured boxes in Fig. 4a. These correspond to h10BN layers grown on a terrace (blue) and step edge (green), and the exposed h11BN flake surface (pink). These images reveal that the hBN lattices are all aligned and therefore the dominant orientation of the epilayer is 0° with respect to the underlying h11BN growth template. By comparing the lattice directions (pink arrows) with the orientation of the grown hBN facets, it can also be deduced that faceted edges of the grown h10BN are armchair-terminated. This indicates that the edge termination of the h10BN is not determined by the orientation of the nucleating step edge, and instead the edges evolve into their most energetically favourable configuration51, as is the case for HT-MBE hBN grown on HOPG42,43.

Micro-Raman Spectroscopy (μ-RS) and Scattering-type Near-Field Optical Microscopy (s-SNOM) characterisations

The harmonic oscillator model informs us that the frequency of a given lattice vibration (ν) is inversely proportional to atomic mass (ν ~ √(k/µ)), where k is the force constant and µ the reduced mass). Consequently, vibrational spectroscopy analysis represents an ideal methodology to discriminate the different isotopes of B present in the MBE-grown flakes prepared. Belonging to the D6h point group and comprising an irreproducible representation containing zone-centre phonon modes of E1u + A2u + 2E2g + 2B1g symmetry, the E1u and E2g modes of hBN, both involving in-plane atomic displacements, are infrared and Raman active, respectively, appearing in both cases at ~1357, 1366 and 1393 cm−1 for h11BN, hNatBN and h10BN, respectively20,21. Figure. 5 shows μ-RS analysis of epitaxial h10BN on a ~10 nm thick h11BN flake after 4 hours growth. As expected, the spectrum is dominated by a peak at 1357.1 cm−1 corresponding to the h11BN flake; however, a second, weaker signal is also detected 1393.8 ± 0.4 cm−1 (uncertainty due to Lorentzian peak fitting), shown in the inset of Fig. 5, in good agreement with that expected for h10BN21,30. The h10BN:h11BN ratio of the peak areas is 0.024 ± 0.001, which would suggest just below a monolayer coverage of hBN within the laser spot, assuming the Raman scattering cross section is the same for the two isotopes, and minimal scattering losses from the lower layers. We note that very thin h11BN flakes are required to detect a signal from the h10BN epilayer due to the dominance of the h11BN signal. The FWHM of the h10BN peak is 12 ± 1 cm−1, which compares favourably with MOCVD-grown hBN layers (noting these contain natural isotope mixtures)37,54, but is broadened compared to isotopically purified bulk h10BN crystals (typically ~4 cm−1)21,30. We attribute the broadening to the small domain sizes (~200 nm) for the measured sample, which will result in grain boundaries and edges within the laser spot. A small degree of broadening is also expected due to the lower isotope purity of the 10B source compared to 11B source (see Experimental Details).

Since μ-RS is limited by optical diffraction and the h10BN domains are smaller than the limiting spatial resolution, it was not possible to spatially discriminate h10BN and h11BN by μ-RS. Instead, the h10BN and h11BN layers were spatially resolved in the heterostructure using s-SNOM at frequencies near the transverse optical (TO) phonon of the E1u mode in h11BN (Fig. 6). Since the TO resonances vary with different isotopes, the epitaxially grown h10BN monolayers show contrast in the s-SNOM amplitude images. At a representative frequency of 1345 cm−1, the hexagonally shaped h10BN monolayers exhibit lower contrast in the s-SNOM image (Fig. 6a) and its zoomed-in view (Fig. 6b). The extracted line profile (Fig. 6d) along the black dashed arrow in Fig. 6b reveals a ~3% reduction in s-SNOM amplitude for grown h10BN monolayers on h11BN compared to a pristine h10BN flake. This s-SNOM contrast of the grown h10BN is evident at frequencies (Fig. 6e) below the h11BN TO phonon (1357 cm−1) since these imaging frequencies are closer to the h11BN resonance rather than the h10BN TO resonance at 1393 cm−1. A systematic s-SNOM imaging study on the epitaxially grown h10BN/h11BN heterostructure shows the s-SNOM contrast—s-SNOM amplitude ratio between the grown monolayer h10BN/h11BN and pristine h11BN—varies with frequency. As the frequency increases, the contrast decreases, reaching a minimum at the h11BN TO phonon (1357 cm−1) before rising as it approaches the h10BN TO phonon (1393 cm−1). At another representative frequency of 1380 cm−1 (Fig. 6c), the s-SNOM contrast between the grown monolayer h10BN/h11BN and pristine h11BN becomes negligible, and phonon polariton standing wave fringes appear near the sample edge.

s-SNOM amplitude images of epitaxial h10BN grown on h11BN at 1345 cm−1 (a, b) and 1380 cm−1 (c). b is the zoom-in image of the rectangular region in (a). d Line profile of the near-field amplitude extracted along the dashed arrow in (b). e s-SNOM contrast—s-SNOM amplitude ratio between the grown h10BN monolayer on h11BN (blue circle in (b)) and the pristine h11BN flake (red circle in (b))—at various frequencies. The squares represent mean values, with error bars indicating standard deviations.

Discussion

In this work, we have elucidated the step-flow hBN homoepitaxial growth mechanism by examining the initial stages of growth in the presence and absence of steps on the hBN surface. These findings are in line with previous demonstrations of step-flow growth of hBN on graphene42,43 and vice versa55. We anticipate that our approach of H2-etching to improve nucleation of the hBN epilayer will be relevant for HT-MBE and MOVPE alike. Recent studies of hBN homoepitaxy by MOVPE showed growth of multilayer hBN primarily at the edges of exfoliated hBN flake edges44. Furthermore, nucleation from zigzag-oriented flake edges forced the growth of non-centrosymmetric BN layers with Bernal stacking (bBN). Thus, the formation of zigzag step edges by H2-etching, as demonstrated in this work, may provide a route to deterministic growth of bBN crystals. We have attempted to identify the layer stacking between the h10BN epilayer and h11BN flakes in this work by photoluminescence (PL) and second-harmonic generation (SHG)10; however, these measurements were not successful, likely due to the predominantly monolayer thickness of the epilayer. At present, the main limitation of HT-MBE growth is the slow growth rates on van der Waals surfaces, which limit the epilayer thickness to a few layers. Achieving higher growth rates by increasing the boron flux or reducing the substrate temperature (to reduce desorption of adatoms from the surface) comes at the expense of the structural quality of the layers, which contain more grain boundaries and 3D aggregates43. Faster growth rates can be achieved on sapphire substrates (~4 nm/h) under identical growth conditions, but also with reduced crystalline quality, producing polycrystalline layers with weak optical response1,41.

Developing HT-MBE growth of isotopically enriched hBN, as demonstrated in this work, expands the possibility of growing hBN layers with mixed or single isotopes at scales compatible with device fabrication. The use of elemental B and N sources in HT-MBE makes it a uniquely suitable and versatile tool to grow on hBN thin films and heterostructures with controlled isotope compositions. By contrast, vapour-based growth methods (e.g., CVD and MOCVD), which are the most widely used methods for growing hBN thin films, require specialised precursors that are not readily available in an isotopically purified form. Recent demonstrations of ultrafast heat transfer across solid-solid interfaces via phonon-polariton coupling56, and improved thermal conductivity in isotopically pure hBN (including at the monolayer limit)22,23,24, make this system highly appealing for thermal management in future 2D electronic systems57. Additionally, our results showing the growth of phase-separated h10BN and h11BN heterostructures are promising for emerging nanophotonic technologies that utilise hyperbolic phonon polaritons in isotope-engineered van der Waals and lateral heterostructure configurations. Overall, we expect this work to stimulate advances in isotope-controlled hBN synthesis using wafer-scale growth processes.

Methods

Growth of isotopically enriched Bulk h11BN crystals

The bulk monoisotope h11BN crystalline flakes were grown using an iron-chromium flux and elemental 11B-enriched boron (99.41 at%) as described in ref. 18. After evacuating and purging the furnace, powders of the source materials were placed in an alumina crucible, then heated to 1550 °C under flows of 700 sccm of N2 (natural isotope abundance, 99.6% 14N and 0.4% 15N) and 30 sccm of forming gas (95% Ar and 5% H2), at 820 Torr. The mixture was held at this temperature for 24 hours, to ensure the solution composition was well-mixed and uniform. To grow crystals, the solution was slowly (4 °C h−1) cooled to 1450 °C, then rapidly cooled (200 °C h−1) to room temperature. Freestanding h11BN crystals (10 to 20 µm thick) were produced by exfoliating them from the metal ingot using thermal release tape.

High-temperature molecular beam epitaxy

Epitaxial h10BN layers were grown by HT-MBE using a custom-designed Veeco GENxplor system capable of achieving substrate temperatures up to 1850 °C (measured by thermocouple)1,41. An active nitrogen flux was provided by a Veeco RF plasma source operated at a fixed RF power of 550 W and N2 (natural isotope abundance, 99.6% 14N and 0.4% 15N) gas flow rate of 2 sccm. The boron flux was produced by a Veeco high-temperature Knudsen effusion cell operating at 1875 °C. The cell was loaded with isotopically enriched 10B (purity >96%) or 11B (purity >98%). All samples studied in this work were grown at a substrate heater temperature of 1390 °C, with the growth time ranging from 1–6 h to achieve variable coverage.

Isotopically enriched h11BN flakes were mechanically exfoliated onto single-side polished sapphire wafers and soaked in toluene for 4 hours to remove tape residues. Prior to HT-MBE, samples were cleaned by annealing for 8 hours in a flowing H2/Ar (5%, 0.15 slpm) atmosphere at 600 °C to preserve the exfoliated surface, or at 1000 °C for H2-etching.

Atomic force microscopy

AFM measurements were conducted using an Asylum Research Cypher S microscope in ambient conditions. Tapping mode and lateral force microscopy images were acquired using Si cantilevers with a nominal spring constant of 2 Nm−1 (SCOUT 70 RAl, NuNano).

Secondary ion mass spectrometry

The chemical concentrations of B and N were studied as a function of depth using SIMS in two commercial systems, namely a Cameca IMS-3F and a Cameca IMS-7F. The 10B and 11B isotope analysis was carried out using O2+ primary ion bombardment and positive secondary ion detection to optimise sensitivity to boron. The data were not calibrated due to a lack of suitable reference calibration standards.

Scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscopy

The nano-imaging of epitaxially grown h10BN/h11BN was conducted using the scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscope (s-SNOM) from Attocube. The s-SNOM is based on a tapping-mode AFM. In the experiments, the PtIr-coated AFM tip with a radius of ~10 nm (Arrow-NCPt, NanoWorld AG, Switzerland) was illuminated by monochromatic Mid-IR quantum cascade lasers (QCLs, www.daylightsolutions.com) with frequency spanning 845 to 1800 cm−1. The s-SNOM images were recorded by a pseudoheterodyne interferometric detection module with a tapping frequency of 245–280 kHz and tapping amplitude of ~70 nm. The detected optical signal was demodulated at the fourth harmonics of the tapping frequency in order to obtain the pure near-field signal.

Micro Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy measurements were acquired with a HORIBA LabRAM Evolution Raman spectrometer using 532 nm laser excitation focused through a 100× objective (NA 0.9) and a 100 μm confocal pinhole. A rotatable diffraction grating with 1800 lines mm−1 and a Synapse CCD were used for detection, resulting in a pixel separation of <0.3 cm−1 (as measured at the low-energy cut-off). Raman spectra were calibrated using a polystyrene reference mounted on the instrument objective turret (SP-RCO).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the following URL/DOI: 10.17639/nott.7593.

References

Vuong, T. Q. P. et al. Deep ultraviolet emission in hexagonal boron nitride grown by high-temperature molecular beam epitaxy. 2D Mater. 4, 021023 (2017).

Elias, C. et al. Direct band-gap crossover in epitaxial monolayer boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 10, 2639 (2019).

Rousseau, A. et al. Spatially-resolved UV-C emission in epitaxial monolayer boron nitride. 2D Mater. 11, 025026 (2024).

Tran, T. T., Bray, K., Ford, M. J., Toth, M. & Aharonovich, I. Quantum emission from hexagonal boron nitride monolayers. Nat. Nano 11, 37–41 (2016).

Aharonovich, I., Tetienne, J.-P. & Toth, M. Quantum emitters in hexagonal boron nitride. Nano Lett. 22, 9227–9235 (2022).

Mendelson, N. et al. Identifying carbon as the source of visible single-photon emission from hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 20, 321–328 (2021).

Stern, H. L. et al. A quantum coherent spin in hexagonal boron nitride at ambient conditions. Nat. Mater. 23, 1379–1385 (2024).

Stern, H. L. et al. Room-temperature optically detected magnetic resonance of single defects in hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 13, 618 (2022).

Gao, X. et al. Nuclear spin polarization and control in hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 21(9 21), 1024–1028 (2022).

Rousseau, A. et al. Bernal Boron nitride crystals identified by deep-ultraviolet Cryomicroscopy. ACS Nano 16, 2756–2761 (2022).

Iwański, J. et al. Revealing polytypism in 2D boron nitride with UV photoluminescence. NPJ 2D Mater. Appl. 8, 72 (2024).

Moon, S. et al. Wafer-scale AA-stacked hexagonal boron nitride grown on a GaN substrate. Nat. Mater. 24, 843–851 (2025).

Rousseau, A. et al. Determination of the optical bandgap of the Bernal and rhombohedral boron nitride polymorphs. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 064602 (2021).

Yasuda, K., Wang, X., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Jarillo-Herrero, P. Stacking-engineered ferroelectricity in bilayer boron nitride. Science 372, 1458–1462 (2021).

Lv, M. et al. Spatially resolved polarization manipulation of ferroelectricity in twisted hBN. Adv. Mater. 34, 2203990 (2022).

Vizner Stern, M. et al. Interfacial ferroelectricity by van der Waals sliding. Science 372, 1462–1466 (2021).

Wong, S. et al. Epitaxial ferroelectric hexagonal boron nitride grown on graphene. Adv. Mater. 37, 2414442 (2025).

Alemoush, Z. et al. Status of h-BN quasi-bulk crystals and high efficiency neutron detectors. J. Appl. Phys. 135, 175704 (2024).

Li, J., Tingsuwatit, A., Alemoush, Z., Lin, J. Y. & Jiang, H. X. Ultrawide bandgap semiconductor h-BN for direct detection of fast neutrons. APL Mater. 13, 11101 (2025).

Janzen, E. et al. Boron and nitrogen isotope effects on hexagonal boron nitride properties. Adv. Mater. 36, 2306033 (2024).

Vuong, T. Q. P. et al. Isotope engineering of van der Waals interactions in hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 17, 152–158 (2018).

Mercado, E. et al. Isotopically enhanced thermal conductivity in few-layer hexagonal boron nitride: implications for thermal management. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 3, 12148–12156 (2020).

Yuan, C. et al. Modulating the thermal conductivity in hexagonal boron nitride via controlled boron isotope concentration. Commun. Phys. 2, 43 (2019).

Cai, Q. et al. Outstanding thermal conductivity of single atomic layer isotope-modified boron nitride. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 085902 (2020).

Chen, M. et al. Van der Waals isotope heterostructures for engineering phonon polariton dispersions. Nat. Commun. 14, 4782 (2023).

Giles, A. J. et al. Ultralow-loss polaritons in isotopically pure boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 17, 134–139 (2018).

Dai, S. et al. Tunable phonon polaritons in atomically thin van der Waals crystals of boron nitride. Science 343, 1125–1129 (2014).

Gong, R. et al. Isotope engineering for spin defects in van der Waals materials. Nat. Commun. 15, 104 (2024).

Haykal, A. et al. Decoherence of VB- spin defects in monoisotopic hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 13, 4347 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Single crystal growth of millimeter-sized monoisotopic hexagonal boron nitride. Chem. Mater. 30, 6222–6225 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Single crystal growth of monoisotopic hexagonal boron nitride from a Fe–Cr flux. J. Mater. Chem. C. Mater. 8, 9931–9935 (2020).

Sutter, P., Lahiri, J., Albrecht, P. & Sutter, E. Chemical vapor deposition and etching of high-quality monolayer hexagonal boron nitride films. ACS Nano 5, 7303–7309 (2011).

Ma, K. Y. et al. Epitaxial single-crystal hexagonal boron nitride multilayers on Ni (111). Nature 606, 88–93 (2022).

Wang, G. et al. Wafer-scale single crystal hexagonal boron nitride layers grown by submicron-spacing vapor deposition. Small 19, 2301086 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Epitaxial growth of a 100-square-centimetre single-crystal hexagonal boron nitride monolayer on copper. Nature 570, 91–95 (2019).

Wang, L. et al. Growth and etching of monolayer hexagonal boron nitride. Adv. Mater. 27, 4858–4864 (2015).

Bansal, A. et al. Substrate modification during chemical vapor deposition of hBN on sapphire. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 54516–54526 (2021).

Kim, J. et al. Conformal growth of hexagonal boron nitride on high-aspect-ratio silicon-based nanotrenches. Chem. Mater. 35, 2429–2438 (2023).

Summerfield, A. et al. Moiré-modulated conductance of hexagonal boron nitride tunnel barriers. Nano Lett. 18, 4241–4246 (2018).

Pierucci, D. et al. Van der Waals epitaxy of two-dimensional single-layer h-BN on graphite by molecular beam epitaxy: Electronic properties and band structure. Appl Phys. Lett. 112, 253102 (2018).

Cheng, T. S. et al. High-temperature molecular beam epitaxy of hexagonal boron nitride layers. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Nanotechnol. Microelectron.: Mater. Process. Meas. Phenom. 36, 02D103 (2018).

Thomas, J. et al. Step-flow growth of graphene-boron nitride lateral heterostructures by molecular beam epitaxy. 2D Mater. 7, 035014 (2020).

Wrigley, J. et al. Epitaxy of boron nitride monolayers for graphene-based lateral heterostructures. 2D Mater. 8, 034001 (2021).

Binder, J. et al. Homoepitaxy of boron nitride on exfoliated hexagonal boron nitride flakes. Nano Lett. 24, 6990–6996 (2024).

Jean-Remy, P. M., Cabral, M. J. & Davis, R. F. Chemical vapor deposition of sp2-boron nitride on mechanically polished pyrolytic boron nitride substrates. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 40, 42203 (2022).

Novikov, S. V. & Foxon, C. T. Unintentional boron incorporation in AlGaN layers grown by plasma-assisted MBE using highly efficient nitrogen RF plasma-sources. J. Cryst. Growth 477, 154–158 (2017).

Chen, L. et al. Direct observation of layer-stacking and oriented wrinkles in multilayer hexagonal boron nitride. 2D Mater. 8, 024001 (2021).

Stehle, Y. Y. et al. Anisotropic etching of hexagonal boron nitride and graphene: question of edge terminations. Nano Lett. 17, 7306–7314 (2017).

Liu, H. et al. Structure evolution of hBN grown on molten Cu by regulating precursor flux during chemical vapor deposition. 2D Mater. 9, 015004 (2021).

Stehle, Y. et al. Synthesis of hexagonal boron nitride monolayer: control of nucleation and crystal morphology. Chem. Mater. 27, 8041–8047 (2015).

Zhang, L. & Ding, F. The stable interfaces between various edges of hBN and step edges of Cu surface in hBN epitaxial growth: a comprehensive theoretical exploration. 2D Mater. 8, 034004 (2021).

Falin, A. et al. Anomalous isotope effect on the mechanical properties of a single atomic layer of Boron Nitride. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–9 (2023).

Chiodini, S. et al. Moiré modulation of Van der Waals potential in twisted hexagonal boron nitride. ACS Nano 16, (2021).

Mohammad, A. et al. Effective substrate for the growth of multilayer h-BN on sapphire—substrate off-cut, pre-growth, and post-growth conditions in metal-organic vapor phase epitaxy. 2D Mater. 10, 025010 (2023).

Bradford, J. et al. Graphene nanoribbons with hBN passivated edges grown by high-temperature molecular beam epitaxy. 2D Mater. 10, 035035 (2023).

Hutchins, W. et al. Ultrafast evanescent heat transfer across solid interfaces via hyperbolic phonon–polariton modes in hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 24, 698–706 (2025).

Brasington, A. et al. Phonon lifetimes in boron-isotope-enriched graphene-hexagonal boron nitride devices. Phys. Status Solidi (RRL) – Rapid Res. Lett. 16, 2200030 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Nanoscale and Microscale Research Centre (nmRC) and Prof. Mike George for providing access to micro-Raman instrumentation made available through funding from the Engineering and Physical Science Research Council (EPSRC) (Grant no. EP/V053884/1). We also acknowledge Loughborough Surface Analysis Ltd for SIMS measurements and discussions of results. The authors kindly acknowledge the efforts of Juliette Plo for attempting PL and SHG measurements. The work in Nottingham was supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (Grant no. EP/V05323X/1 and EP/W035510/1). Support for hBN crystal growth came from the Materials Engineering and Processing programme of the National Science Foundation, Award Number CMMI 1538127. S.D. acknowledges the support from the National Science Foundation under Grant No. DMR-2238691, DMR-2525882 and ACS PRF fund 66229-DNI6. J. S. acknowledges financial support from the Alabama Graduate Research Scholars Program (GRSP), funded through the Alabama Commission for Higher Education and administered by the Alabama EPSCoR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was conceptualised by J.H.E., G.C., and S.V.N. The bulk hBN crystals were grown by J.L. and J.H.E., and hBN epilayers were grown by T.S.C. J.B. performed the H2-etching experiments and conducted the AFM measurements and data analysis with assistance from A.F.M.C. J.S. and S.D. carried out s-SNOM measurements and data analysis. J.K. and G.R. conducted Raman spectroscopy measurements. Funding and supervision were provided by C.J.M., P.H.B., and S.V.N. J.B. drafted the original manuscript with input from all co-authors. All co-authors contributed to the review of the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bradford, J., Collins, A.F.M., Cheng, T.S. et al. Homoepitaxial growth of isotopically enriched h10BN layers on h11BN crystals by high-temperature molecular beam epitaxy. npj 2D Mater Appl 9, 98 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00619-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00619-4