Abstract

The performance of photodetectors can be significantly enhanced by incorporating a suitable transport layer, where the work function and density of states (DOS) are critical parameters in material selection. MXenes, with their tunable work functions, offer versatility for integrating diverse active materials in device architectures. In this work, we investigate the photodetection performance and piezophototronic effect of three tin monosulfide (SnS)-based device configurations, validated through band structure analysis. SnS was integrated with Ti₃C₂Tₓ and Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ MXenes and benchmarked against a reference SnS/Ag device. The fabricated devices—SnS, SnS/Ti₃C₂Tₓ, and SnS/Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ—exhibited responsivities of 7.67 A/W (5.86 A/W), 15.07 A/W (12.41 A/W), and 89.23 A/W (57.42 A/W) with (without) strain, respectively. Density functional theory calculations revealed enhanced DOS at the Fermi level for both MXenes, highlighting their bipolar transport nature. A comprehensive comparison is provided in terms of Schottky barrier height, DOS, and piezophototronic modulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The current research on transport-layer-based broadband photodetectors is increasing because of the prominent role played by the transport layer in the performance of any photodetector. The mobility of the carriers was greatly enhanced by introducing a transport layer in the photodetector device delivering instant photocurrent at shorter rise times1,2,3. The transport layer, apart from being conductive, allows the rapid charge migration to its respective electrodes at low carrier lifetime and less recombination, resulting in high responsivity in photodetector devices4,5. However, it is important to consider the work function of the transport layer that creates the desired barrier height, surface states, traps, etc., for feasible carrier transportation across the device interface to deliver high photocurrent6,7. Furthermore, the wide range tunability8 (~6.04 eV) of the work function makes the transport layer preferable to many active materials in having the desired properties at the interface for effective charge migration9,10. Thus, there is a need to modulate the work function of transport layers to make many active material systems adaptable in device fabrication for various optoelectronic applications in different fields.

MXenes, as transition-metal carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides, are one of the growing family of two-dimensional (2D) materials that have garnered interest due to their unique electronic properties, such as high mobility11, reliability (performance accuracy), better environmental stability, tunable work function (4.0–6.6 eV)12, and mechanical flexibility13. All these properties make MXene a promising transport layer material in optoelectronic applications, including light-emitting diodes, photovoltaics, phototransistors, and photodetectors14. MXenes’ (titanium carbide, Ti3C2Tx) work function is notably higher than (~1.3 times for SnS) many active materials (many semiconductor TMDs, including MoS2, ReS2, WS2)15,16,17,18, which helps in achieving many electronic properties, making effective charge migration at the interface. The work function of MXene can be modulated in many ways, which include selective doping, synthesis procedures, creating defects, etc.19,20,21. As the work function is the most distinguished parameter in deciding the barrier height, trap energy levels, and carrier migration across any interface, the wide range tunable work function makes MXene suitable in many transport-layered-based photodetectors22,23. Double transition-metal MXene (such as molybdenum titanium carbide, Mo2TiC2Tx) could be preferred over mono-metal MXenes (such as titanium carbide, Ti3C2Tx)24 as Mo2TiC2Tx has been predicted to be a semiconductor (and its semiconductor-like behavior25) when compared with metallic properties of Ti3C2Tx counterpart26,27. In addition, the photodetector performance can be greatly enhanced by the work function variation of the transport layer. The tuneable work function of Mo2TiC2Tx (transport layer) allows the barrier height to be considerably high, making effective charge migration at the interface. In addition, a higher density of states (DOS) of Mo2TiC2Tx makes it a suitable candidate as a transport layer in both photodetector and photovoltaic applications28,29,30,31.

Tin monosulfide (SnS), a most promising p-type 2D transition-metal monochalcogenide, has received more attention in recent years due to its large abundance with low cost, tunability in its bandgap, greater sensitivity, high absorption, and piezoelectricity32,33. In the past few years, researchers have reported various optoelectronic applications of SnS and its performance as a photodetector34,35, suggesting SnS is one of the best choices as an active material in transport layer-based photodetector devices. Because of the SnS considerable conversion efficiency (~40.5%36), a heterojunction is needed, as pristine SnS suffers from a recombination problem resulting in poor responsivity when subjected to external light/strain37,38. Apart from previously published works on transport-layer-based photodetector devices, extracting band structure and analyzing the piezophototronics effect were the least explored. The piezophototronic effect is a combination of the piezoelectric effect, semiconductor physics, and photoexcitation of carriers39,40,41. Accordingly, when piezoelectric semiconductor material (SnS) is subjected to external strain (compressive strain), its barrier height will increase, which increases depletion region width, and improves the internal electric field and photoresponsivity42.

In this study, SnS was incorporated with suitable transport materials like Ti3C2Tx and Mo2TiC2Tx to enhance carrier separation and transportation to improve responsivity. We used two isostructural MXenes with different compositions (Ti3C2Tx and Mo2TiC2Tx) and demonstrated the photodetection performance of SnS, SnS/Ti3C2Tx, and SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx device configurations and their band structure variations to understand the piezophototronic effect. The band structures of the SnS, Ti3C2Tx, and Mo2TiC2Tx were extracted by calculating their work functions using density functional theory (DFT) studies. Ti3C2Tx43,44 and Mo2TiC2Tx MXenes are selected as efficient transport layers due to their variable work functions as well as bipolar nature. The DFT calculations suggest the bipolar nature of the transport layer because of the higher DOS at the Fermi level. Hence, both the contacts for all the configurations were fabricated on MXenes. The carrier generation and migration, and the band alignment at the interface of all device configurations were studied upon subjecting devices to visible light with/without external strain. The fabricated photodetector devices SnS, SnS/Ti3C2Tx, and SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx exhibited responsivities of 7.67 A/W (5.86 A/W), 15.07 A/W (12.41 A/W), and 89.23 A/W (57.42 A/W) with (without) strain, respectively. Among all the device configurations, the highest responsivity was noted for the SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx device under external strain. This was due to the easy transport of photogenerated electrons and holes from SnS to Mo2TiC2Tx (in SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx device) compared to SnS to Ti3C2Tx (in SnS/Ti3C2Tx device). The Schottky barrier for photogenerated electrons created at the interface of the SnS/Ti3C2Tx device configuration is comparatively higher than SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx device. Due to this, the recombination in SnS/Ti3C2Tx configurations increases. The detailed analysis and study of the MXene transport layer pave the way for its use in optoelectronic systems, including photovoltaic.

Results

Characterization of SnS

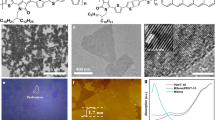

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to analyze the crystal structure and crystallinity of the synthesized SnS material. The peaks at 22.16°, 26.16°, 27.6°, 30.65°, 31.73°,39.17°, 42.68°, 45.62°, 48.68°, 51.45°, 53.31°, 56.8°, 64.3° and 66.7° are in the SnS XRD pattern shown in Fig. 1a. These XRD diffraction peaks correspond to the following orientations: (171), (212), (042), (231), (112), (211), (002), (210), (131), (111), (101), (021), (120), and (110), respectively, which are orthorhombic structures of SnS, JCPDS # 39-035445,46. The lattice parameters (a, b, c), crystallite size, micro strain, and dislocation density from the XRD data were estimated. The crystallite size was calculated using the Debye–Scherrer equation from the most intense diffraction peak, while the micro strain and dislocation density were derived. The obtained values indicate nanocrystalline domains with slight lattice distortions, consistent with the observed peak broadening. These structural constants further support that defects and strain-induced distortions play a role in tuning the optoelectronic properties of SnS and its heterostructures.

Further, XPS (X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy) measurements were carried out to confirm the chemical composition and oxidation state of the synthesized SnS. The survey spectra of XPS confirmation of the presence of Sn and S components are shown in Fig. S1a of SI (supplementary Information). Oxygen is present in the survey spectra due to the partial oxidation of SnS, and carbon is present due to the stub used during the XPS analysis. The two distinctive peaks in the high-resolution Sn 3d XPS spectrum, which are centered at binding energies of 495.2 eV and 486.5 eV, related to Sn2+ 3d3/2 and Sn2+ 3d5/2, respectively47,48, are shown in Fig. 1b. Two strong peaks, centered at 161.2 eV and 160.1 eV in the high-resolution spectra of S 2p, can be attributed to S2− 2p1/2 and S2− 2p3/2 shown in Fig. 1c. These characterization results are in agreement with the previously reported literature of SnS49. Raman spectrum analysis50 was used to examine the structural phases of the prepared SnS. Raman modes are seen at 214 cm−1, 184.7 cm−1, 156.6 cm−1, 95 cm−1, and 64 cm−1, as depicted in Fig. S1b of SI. These modes correspond to the various optical phonon modes of SnS. Ag longitudinal optical mode is represented by the peak at 184.7 cm−1, while Ag transverse optical mode is represented by the peak at 95 cm−1. The B3g mode is identified by the peak detected at 156.6 cm−1, while the B2g and Ag modes of SnS are represented by the peak observed at 64 cm−1. The Raman spectrum investigation verifies that SnS does not include any impurity phases, such as SnS2, Sn2S3, which typically exhibit strong peaks at 312 cm−1 and 308 cm−1 51.

The surface morphology of the SnS was observed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) analysis. Low magnification of the FESEM image of SnS (Fig. S1c) confirms the uniform deposition of SnS on ITO-coated PET substrate. Additional FESEM images are shown in Fig. S2 of the SI. We also conducted elemental mapping with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), which shows the presence of Sn and S, shown in Fig. S3 of SI.

Characterization of Ti3C2Tx MXene

Figure 1d shows the XRD pattern of the Ti3C2Tx film, which indicates the successful selective etching of its precursor with peaks at 6.25° (002), 12.3° (004), 19.05° (006), and 26.17° (008) and no sharp peaks of its precursor (Ti3AlC2). The XRD pattern of the corresponding MAX is shown in Fig. S4 of SI with all the peaks indexed after pre-HCl acid wash52,53. The XPS survey spectra of the Ti3C2Tx MXene film are shown in Fig. S1d where the binding energies of Ti 3p, Ti 3s, C 1s, Ti 2p, O 1s, and Ti 2s are expected to be 36.03 eV, 60.61 eV, 285.33 eV, 455.72 eV, 530.16 eV, and 562.70 eV, respectively. Two of the four doublet peaks of Ti 2p, namely Ti 2p1/2 and Ti 2p3/2, are fitted to the core level in Fig. 1e. The area ratio of Ti 2p1/2 and Ti 2p3/2 is 1:2, and the binding energy between each doublet is around 6 eV. Ti-X refers to titanium carbides or titanium oxy-carbides. Ti-C (Ti+), Ti-X (Ti2+), TixOy (Ti3+), and TiO2 (Ti4+) were identified as the components of Ti 2p3/2 at 455.37 eV, 456.49 eV, 457.58 eV, and 459.49 eV, respectively54. Minor oxidation of the Ti3C2Tx films after deposition is indicated by the existence of the TiO2 signal at 459.49 eV55. Figure 1f illustrates the core level fitting of C 1 s with 5 components, Ti–C, C–C, –CH2 and –CH3, C–O, and –COO, at 281.96 eV, 284.38 eV, 285.26 eV, 286.63 eV, and 289.19 eV, respectively56. The surface morphology of the MXene thin film was characterized by FESEM. Figure S1e shows FESEM images of the MXene film in its layered structure. Besides FESEM images indicating the thickness of Ti3C2Tx with SnS on top, the elements of the synthesized Ti3C2Tx MXene, EDX, and elemental mapping are shown in Fig. S5 of the SI.

Characterization of Mo2TiC2Tx MXenes

Figure 1g shows the XRD pattern of Mo2TiC2Tx with peaks at 5.9° (002), 11.9° (004), and 17.7° (006), indicating the successful formation of MXene47,48. In the XPS survey of Mo2TiC2Tx in Fig. S1f, the Mo 3d, C 1s, Ti 2p, and F 1s are assigned binding energies of 229.08 eV, 284.83 eV, 455.72 eV, and 685.08 eV, respectively. Carbon is present potentially due to the stub used during the XPS analysis. The two distinctive peaks in the high-resolution Mo 3d XPS spectrum, which are centered at binding energies of 231.88 eV and 228.78 eV are related to Mo 3d3/2 and Mo 3d5/2, respectively (Fig. 1h). Two strong peaks, centered at 460.58 eV and 454.68 eV in the high-resolution spectra of Ti 2p, can be attributed to Ti 2p1/2 and Ti 2p3/2 shown in Fig. 1i. These characterization results are similar with the previously reported literature of Mo2TiC2Tx57. The surface morphology of Mo2TiC2Tx MXene multilayered stacked flakes and single-to-few-layer flakes was observed by FESEM analysis (Fig. S6a, b of SI). To further ensure the elements of synthesized Mo2TiC2Tx MXene, EDX, and elemental mapping have been done, which confirms the presence of Mo, Ti, and C shown in Fig. S7 of SI. The quantitative EDAX results with atomic weight percentages of the constituent elements where shown in Fig. S8. EDAX analysis of Ti3C2Tx and Mo2Ti2Tx MXenes confirmed the expected presence of Ti, Mo, and C along with surface terminations (O/F), consistent with previously reported literature.

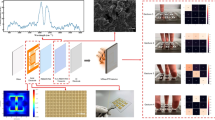

Photodetection measurements

The photodetection measurements were performed in a dark condition using a source meter (Keithley 2450) at room temperature. For the measurement, a 555 nm wavelength light beam was utilized, which was controlled by an LED Power meter (Holmarc Opto-Mechatronics Ltd, India) as shown in Fig. S9. We have fabricated all three device configurations with identical device dimensions (1.5 × 0.5 cm) with a biasing voltage of 1 V, as shown below in Fig. S10. Photodetection experiments were carried out by subjecting all the device configurations to external strain under visible light (555 nm) to estimate the performance parameters. We would like to state that the intention was to study the bipolar nature of the transport material with piezophototronic effect with only one wavelength (555 nm), where the absorption is higher, and the motive was not to demonstrate the broadband nature of the SnS, which is already well reported in the literature57. We took extra care to avoid interaction of the device with external light by keeping the device in the dark box prior to the experiment. Figure S11a–f shows the current–voltage (I–V) characteristics of devices SnS, SnS/Ti3C2Tx, and SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx (with and without strain), respectively. The I–Vs of all the devices resemble linear curves, which results in ohmic contact formation due to the work function difference of the materials used in respective device configurations58. The reason for fabricating the silver electrodes on MXene was decided based on the charge transport studied from the band diagram. When the electron–hole pair is generated in the active material (SnS), both the photogenerated electron and hole are transported to MXenes (both of them) because of the bipolar nature of the transport layer. This necessitates the need for having both the silver electrodes on the transport layer itself. It was noted that the device showed an increase in photocurrent with an increase in the intensity of incident light, indicating effective carrier generation. Also, the temporal response of all the device configurations (SnS, SnS/Ti3C2Tx, and SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx with and without strain) was carried out by constantly switching the light source ON and OFF. During the ON and OFF tests, when the light source was switched ON, an instant increase in device current was observed, and it reached the initial dark current value in a step manner when the light source was switched OFF. This reveals a promising response of the device upon external stimuli, as can be seen in Fig. 2a–c. Furthermore, the temporal response of all the device configurations SnS, SnS/Ti3C2Tx, and SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx (with and without strain) under variable light intensity was carried out by switching the light source ON and OFF with variable intensity. We observed an increase in photocurrent according to the increase in the intensity of incident light when the light source is ON and reaching the initial value when the light source is OFF, giving a staircase pattern as can be seen in Fig. 2d–f. In addition, the device behavior was examined with different increasing strains (under the constant intensity of light at 0.17 mW/cm2). We subjected the devices to different increasing strains from the pristine state (unstrain = 0%) to 5%, 7%, and 10% strains. The strain measurements were calculated based on the extracted formula and also published previously in one of our reports59. Accordingly, the percentages of strains were derived as 5%, 7%, and 10%. Also, the digital image of the tensile bending strain sensing setup is shown in Fig. S12. Also, the device repeatability for equal intervals of 5 days was examined and observed consistent results, as in Fig. S13b. Also, the measurements are conducted with increasing strain, and observed that as the strain (tensile) increases, the responsivity increases, which might be attributed to the increment in the barrier height, which increases the electric field. The barrier height would not have the opposite effect unless the strain applied is reversed (i.e., compressive). Similarly, the reproducibility of devices was also examined by making three devices of each configuration and measuring the responsivity with/without strain. Wherein the authors noticed consistent results all the time, as shown in Figs. 2 and S13c, d. Our results show an increase in photocurrent for all three device configurations with an increase in strain percentages, as shown in Fig. 2g–i, respectively.

a SnS unstrain and strain. b SnS/Ti3C2Tx unstrain and strain. c SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx unstrain and strain. Graphs showing the temporal response when subjected to varying light intensity. d SnS unstrain and strain. e SnS/Ti3C2Tx unstrain and strain. f SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx unstrain and strain. g–i Temporal response when subjected to constant light intensity 0.17 mW/cm2 and increasing strains of 0%, 5%, 7% and 10% for the devices SnS, SnS/Ti3C2Tx, and SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx, respectively.

Responsivity, external quantum efficiency, and detectivity, which determine the performance of any photodetector, are mathematically given as Eqs. 1–3 shown below60,61,

Where, I⋋, P⋋, A, \({I}_{\mathrm{dark}}\), e and ⋋ are photogenerated current, incident source power, active area of the device, dark current of the device, charge of an electron, wavelength, respectively.

The combined graphs of responsivity, EQE, and detectivity for all device configurations SnS, SnS/Ti3C2Tx, and SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx are shown in detail in Fig. 3a–c, respectively. The individual graphs of responsivity, EQE, and detectivity of SnS, SnS/Ti3C2Tx, and SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx device configurations were shown in Fig. S14 of SI as a–c, d–f, and g–i, respectively. To understand the effect of strain, the photodetection measurements were carried out to examine the piezophototronic effect on all three device configurations with/without the application of strain in parallel with external light. We found that the photoresponsivity of each device under external strain is higher when compared to the responsivity of the device without strain. The increase in responsivity under strain could be due to an increase in barrier height at the interface because of the piezophototronic effect. Furthermore, out of the three device configurations, the values of responsivity, EQE (%), and detectivity were measured to be high for SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx compared to other devices under strain, at 89.23 A/W (15.07 A/W for SnS/Ti3C2Tx and 7.67 A/W for SnS device), 199.74 (33.74 for SnS/Ti3C2Tx and 17.16 for SnS device), and 1.86 × 1013 Jones (6.41 × 1012 Jones for SnS/Ti3C2Tx and 3.26 × 1012 Jones for SnS device), respectively. This might be due to higher carrier lifetime and the existence of surface states (compared to other device configurations) for the SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx device, with the barrier height further increasing upon application of strain due to the piezophototronic effect.

Graphs showing a responsivity, b EQE, and c detectivity of SnS, SnS/Ti3C2Tx, SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx devices with and without strain, respectively. Graphs showing d–f temporal response and g responsivity, h EQE, and i detectivity of SnS, SnS/Ti3C2Tx, and SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx. devices, respectively. when subjected to constant light intensity 0.17 mW/cm2 and increasing strains of 0%, 5%, 7% and 10%. g Graph compares the responsivity of the proposed device configuration with other devices’ reported values in the literature.

At 10% strain, a considerable increase of 2.22%, 2.35%, and 2.5% in responsivity, EQE, and detectivity, respectively, were noticed for SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx as shown in Fig. 3d–f. The comparison study was done with the responsivity of the fabricated SnS/MXene devices with previously reported devices involving 2D materials such as graphene, MoS2, and Ti3C2Tx MXene as in Fig. 3g.

We compared the responsivity of the fabricated SnS/MXene devices here with previously reported devices with other 2D materials such as graphene, MoS2, and Ti3C2Tx MXene62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69 as shown in Fig. 3g and the table for the same can be found in supplementary information as Table S1. While numerous reports were observed on fabricating different transport layer-based photodetectors, utilizing MXenes (Ti3C2Tx and Mo2TiC2Tx) as a transport layer, and extracting the real band structure under piezophototronic effect was not explored. In addition, SnS devices with Mo2TiC2Tx MXene as a transport layer (SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx) delivered the highest responsivity compared to many transport layer-based device configurations reported earlier. The highest responsivity is attributed to the highest barrier height for holes at the interface of the SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx device, along with the action of the piezophototronic effect.

Photodetection mechanism with theory

To design any electronic and optoelectronic devices, a major parameter is the work function, which is the minimum energy required to free electrons from the Fermi level to the vacuum level58. DFT studies were performed to extract the band structures of SnS/Ti3C2Tx and SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx device configurations. In order to validate the experimental outcome of work function tunability of different MXene surfaces, we have theoretically performed a series of electronic structure calculations under the framework of DFT. All the geometry optimization and electronic structure calculations are carried out under the framework of spin-polarized DFT70,71 using Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package72,73. In order to describe the interactions between ion cores and electrons, the projector augmented wave method74 has been used, while the exchange correlation part has been approximated using Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof type75 generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functional. A kinetic energy cut-off of 500 eV for the plane-wave basis set has been maintained throughout all the calculations. The 2D Brillouin zone sampling during geometry optimization has been done using the Monkhorst-Pack76 scheme of k-points with 5 × 5 × 1 grids, and a higher k-mesh of 9 × 9 × 1 has been used during the DOS calculations for better accuracy. For all the total energy calculations, the self-consistency criterion has been maintained to 1 × 10−3 eV. On the other hand, to minimize the Hellman–Feynman forces using the conjugate-gradient method, the convergence threshold has been set to 0.01 eV/Å. Since GGA-type semi-local approximations cannot accurately describe the weak van der Waals interactions in the layered structure, we have implemented DFT-D3 type dispersion correction as explained by Grimme77,78. While making the slab model, a vacuum of more than ~20 Å has been used in order to avoid the spurious interaction between the adjacent images. Our method for calculating the work functions is mainly based on the electrostatic potential analysis along a certain direction (normal to the surface plane). The work function can be written as \(\varnothing ={E}_{{vacuum}}-{E}_{F}\), where \({E}_{{vacuum}}\) is the vacuum potential corresponding to the MXene surface and \({E}_{F}\) is the Fermi energy. The simulation cells for Ti3C2Tx and Mo2TiC2Tx MXene surfaces are depicted in Fig. S15. To mimic the experimentally synthesized structure, in our theory calculation, we have also considered two different terminations of Ti3C2Tx MXene with (X: F and OH). Figure S15c shows the relaxed geometry of the surfaces of Mo2TiC2Tx. The slab models are designed along the (001) plane, where a vacuum of more than ~15 Å is used to avoid the interaction between the periodic images. Accordingly, the work functions of both Ti3C2Tx and Mo2TiC2Tx were calculated as 6.75 eV and 6.18 eV, respectively, as shown in Fig. 4a, b. The extraction of work function for SnS (4.47 eV) by means of ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy plot and its detailed explanation was shown in Fig. S16. The schematic of the SnS device made by drop-casting of solution-processed SnS on ITO/PET substrate with both the silver (Ag) contacts taken on SnS (Fig. 4c–i). For configurations with MXenes, the MXene solution (Ti3C2Tx and Mo2TiC2Tx) was deposited on ITO/PET substrate, followed by drop-casting of SnS on MXene along with Ag contacts on MXene film areas (Fig. 4c-ii, iii).

a Ti3C2Tx, b Mo2TiC2Tx, and c schematics of all the device configurations. d Band structure of SnS with Ag contacts, both when isolated and contacted. e Band structure of SnS and Ti3C2Tx, both when isolated and contacted. f Band structure of SnS and Mo2TiC2Tx, both when isolated and contacted. g, h Atom-projected density of states plots for Ti3C2F and Mo2TiC2O surface. The black dashed line shows the Fermi level in each case.

The band structure of three device configurations was extracted by work function values calculated from DFT studies. The devices were subjected to external light in addition to with/without external strain applied. Figure 4d shows the band structure of the SnS device, when isolated and contacted with both the Ag contacts taken on SnS. As SnS is p-type, the majority of carriers will be holes that are in the valence band of SnS. When both contacts are taken on SnS, the valence band energy of SnS will decrease to align the Fermi level uniformly throughout the device. Therefore, for the SnS/Ag device configuration, the valence band energy of SnS is lower than that of Ag. The charge (holes) migration will happen from the valence band of SnS to Ag, giving considerable photocurrent. Furthermore, upon subjecting the SnS/Ag device to external strain, the piezophototronics effect takes place, which further decreases the valence band energy of SnS (as shown in the undotted line) and further improves hole migration, resulting in enhanced photocurrent. Figure 4e, f shows the band structure of the SnS/Ti3C2Tx (SnS /Mo2TiC2Tx) device, when isolated and contacted with both the Ag contacts taken on Ti3C2Tx (Mo2TiC2Tx) (acts as the transport layer).

Due to the work function difference between SnS and Ti3C2Tx, (Mo2TiC2Tx), the conduction and valence band energies of SnS will decrease to align the Fermi-level uniformly throughout the device. Therefore, for SnS/Ti3C2Tx (SnS /Mo2TiC2Tx) device configuration, as the valence band energy of SnS is lower than the energy of Ti3C2Tx (Mo2TiC2Tx), the charge (holes) migration will happen from the valence band of SnS to Ti3C2Tx (Mo2TiC2Tx). In this device configuration, Ti3C2Tx (Mo2TiC2Tx) acts as a transport layer in addition to both the contacts being taken on it for effective carrier collection, giving considerable photocurrent. Furthermore, upon subjecting the SnS/Ti3C2Tx (SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx) device to external strain, piezophototronics will take place, which will further decrease the valence band energy of SnS (as shown in undotted lines) to the transport layer (Ti3C2Tx, Mo2TiC2Tx) and further improve the transportation charge (holes), resulting in enhanced photocurrent.

To have a more profound understanding of the electronic properties, we have also calculated the atom-projected density of states for both surfaces under consideration, which shows the element-wise contribution near the Fermi level. All the surfaces are found to show metallic nature with major contributions either from Ti or Mo-d orbitals near the Fermi level. This suggests that both Ti3C2Tx and Mo2TiC2Tx are excellent electron and hole transport layers. And hence, the contacts were fabricated on Ti3C2Tx and Mo2TiC2Tx for all the configurations. Having considered Ti3C2X Mxene being (X: F), Mo2TiC2X being (X: OH), and comparing the DOS of pristine with doped surfaces, it has been observed that F-terminated pristine Ti3C2Tx have higher states at the Fermi level than the OH-terminated Mo2TiC2Tx surface, as in Fig. 4g, h.

Out of all the device configurations tested, the highest photocurrent and responsivity were noted for the SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx device, which is attributed to the following reasons. The work function difference between SnS and Ti3C2Tx is higher when compared to SnS and Mo2TiC2Tx, which creates a barrier for the photogenerated electron transport from SnS to Ti3C2Tx and comparatively easier for the photogenerated electrons to transport from SnS to Mo2TiC2Tx. This trapping of the photogenerated electrons in Ti3C2Tx leads to the recombination with the holes in the Ti3C2Tx (being p-type), which results in lower photocurrent in the SnS/Ti3C2Tx configuration. In contrast, Mo2TiC2Tx exhibits a moderate DOS near the Fermi level, with dominant contributions from Mo and Ti d orbitals. This moderation limits the formation of recombination centers and suppresses trap-assisted Shockley-Read-Hall recombination at the interface. Although Mo2TiC2Tx may have a slightly lower work function (6.18 eV), it still aligns well with the valence band maximum (VBM) of p-type SnS (~5.2–5.4 eV), particularly under interfacial dipole modulation or slight doping. Moreover, the reduced DOS mitigates Fermi level pinning, enabling better band alignment flexibility and lower effective Schottky barrier heights for holes under practical device operating conditions.

When p-type SnS is subjected to tensile bending strain, its barrier height increases, which then increases photoconductivity, resulting in responsivity increase. The responsivities of SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx, SnS/Ti3C2Tx, and SnS/Ag are noted as 89.23 A/W, 15.07 A/W, and 7.67 A/W, respectively, suggesting that under strained conditions, the responsivity of SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx is higher than SnS/Ti3C2Tx and SnS/Ti3C2Tx is greater than SnS. Also, electrical measurements were performed with increasing strain, and observed that as the strain (tensile) increases, the responsivity increases, which is attributed to the increment in the barrier height, which increases the electric field.

The piezophototronic effect in SnS arises from its intrinsic non-centrosymmetric orthorhombic crystal structure, which enables piezoelectric polarization under mechanical deformation. To demonstrate the piezoelectric nature of the synthesized SnS, piezoelectric force microscopy measurements were performed, and the same has been appended in the supplementary information as Fig. S18. Figure S18 depicts the amplitude versus bias voltage loop for SnS, which demonstrates a butterfly-shaped curve that is typical of an optimal strain-bias setup. This amplitude response directly reflects the local strain at the cantilever tip. The butterfly loop found in the SnS is caused by the opposite piezoelectric effect, and its retracing can be attributed to residual polarization. Local PFM switching spectroscopy loop further confirms the robust piezoelectricity of SnS. The piezoelectric coefficient (d33) was computed by evaluating the slope of the linear section of the butterfly loop under an applied electric field, and the value of d33 was calculated to be ~3.43 pm/V. This confirms that the synthesized SnS possesses piezoelectric properties. When tensile strain is applied, particularly along the in-plane polar axes, a strain-induced piezoelectric potential is generated that results in the decrement of the valence band maxima energy and carrier dynamics at the SnS/transport-layer interface. At the SnS/Ti3C2Tx interface, although the high work function of Ti3C2Tx supports favorable band alignment for hole injection, its inherently high DOS at the Fermi level results in strong free-carrier screening. This metallic behavior suppresses the penetration of the piezoelectric field into the contact region, thereby diminishing the effectiveness of piezophototronic modulation. In contrast, Mo2TiC2Tx exhibits a moderate DOS near the Fermi level and a slightly lower work function, which is compatible with the valence band maximum of p-type SnS. The reduced DOS in Mo2TiC2Tx leads to weaker screening of the piezoelectric potential, allowing strain-induced polarization fields to effectively modulate the interfacial band bending and enhance the internal electric field for charge separation. This results in improved hole selectivity, reduced recombination, and a more pronounced strain-tunable photocurrent response.

Discussion

Precisely, the reasons for the higher responsivity for SnS/ Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ are as follows

-

1.

Due to the lesser work function difference between the SnS and Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ compared to that of SnS/Ag and SnS and Ti3C2Tx, the photogenerated electrons experience less barrier height and are easily transported to Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ. This causes a larger number of electron–hole pairs to be easily transported to Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ, thereby increasing the photocurrent.

-

2.

The larger DOS in Ti3C2Tx at the Fermi level, when compared to Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ, acts as a recombination center for the photogenerated electron/hole pair, and hence a larger portion of the photogenerated electron/hole pair recombines when SnS is coupled with Ti3C2Tx, when compared to SnS being coupled to Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ.

-

3.

To verify point 2, the response time is calculated for each of the configurations as shown in Fig. S17. As observed response (SnS/Ag) > SnS/Ti3C2Tx > SnS/ Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ. The reason for the higher response time for SnS/Ti3C2Tx when compared to SnS/ Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ is due to the higher DOS, wherein those states act as recombination or trapping centers, which increases the time taken for the electron/charge carrier to reach the electrode. Also, the photogain = Recombination time/transit time. Lower transit time/response time increases the photogain, and since the response time of SnS/ Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ is the least among the other configurations, the responsivity is higher for SnS/ Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ. These combined reasons allow for the explanation of the improvement in the responsivity value for SnS/ Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ when compared to SnS/Ti3C2Tx.

The comparative study of SnS-based photodetectors with different transport layers—Ag, Ti₃C₂Tₓ, and Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ MXenes—clearly establishes the superior performance of the SnS/Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ device. The fabricated configurations exhibited responsivities of 7.67 A/W (5.86 A/W), 15.07 A/W (12.41 A/W), and 89.23 A/W (57.42 A/W) with (without) strain for SnS, SnS/Ti₃C₂Tₓ, and SnS/Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ, respectively. DFT calculations confirmed the bipolar nature of both MXenes due to the higher DOS at the Fermi level, which facilitates ambipolar carrier transport. However, the lower work function difference between SnS and Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ results in a reduced Schottky barrier, enabling efficient electron–hole pair separation and transport. In contrast, Ti₃C₂Tₓ, despite its high DOS, introduces significant recombination and trapping centers, thereby increasing response time and reducing photocurrent. The shorter response time and enhanced photogain in SnS/Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ ultimately lead to its markedly higher responsivity. These findings demonstrate that Mo₂TiC₂Tₓ serves as an efficient bipolar transport layer for SnS, offering a compelling route toward high-performance piezophototronic photodetectors.

Methods

Synthesis of SnS, Ti3C2Tx MXene and Mo2TiC2Tx MXene

To synthesize SnS, a similar procedure was followed as reported previously by our group. SnS was synthesized using the solvothermal method79. One millimole of stannous dichloride dihydrate (SnCl2.2H2O) and 2.5 mmol of sodium sulfide nonahydrate (Na2S.9H2O) were mixed with 30 ml of ethylene glycol to create a nutritional solution. Then the solution was vigorously stirred for 15 min using a magnetic stirrer at 700 rpm. Later, the solution was transferred to the 50 mL Teflon container and kept in a hot air oven for 20 h at 200 °C. Subsequently, the resultant solution was washed several times with IPA (isopropyl alcohol) and DI (deionized) water and finally dried in an oven for 12 h at 70 °C, as shown in Fig. 5a.

To synthesize Ti3C2Tx MXene80, 1 g of optimized Ti3AlC2 MAX was first washed using 9 M HCl for 18 h to remove intermetallic impurities and then mixed with an etchant solution (6:3:1 mixture (by volume) of 12 M HCl, deionized water (DI water), and 50 wt % Hydrofluoric acid (HF) (Across International)). The etching reaction was set up for 24 h at 35 °C with continuous stirring at 400 rpm. The etched Ti3C2Tx MXene was washed with deionized water via repeated centrifugation at 3234 RCF (4–5 cycles with ~200 mL of deionized water) until the supernatant reached pH ∼6. For delamination, the etched multilayered Ti3C2Tx MXene sediment was then added to a lithium chloride (LiCl) solution, typically 50 mL/per gram of starting etched powder. The mixture of LiCl and multilayer MXene was then stirred at 400 rpm for 1 h at 65 °C under constant argon gas flow. The mixture was then washed with deionized water via centrifugation at 3234 RCF for 5, 10, 15, and 20 min. Then, the final mixture was vortexed for 30 min followed by centrifugation at 2380 RCF for 30 min to ensure the Ti3C2Tx MXene solutions were single-to-few-layered flakes as shown in Fig. 5b.

To synthesize Mo2TiC2Tx MXene, 1 g of Mo2TiAlC2 MAX phase was mixed with 10 mL of hydrofluoric acid (HF, 49–51 wt%, Fisher Scientific) solution as an etchant in a high-density polyethylene bottle, and stirred at 300 rpm for 96 h at 55 °C. The etched multilayered Mo2TiC2Tx MXene flakes were washed with deionized water through repeated centrifugation and decantation in an Eppendorf centrifuge at 3234 RCF (4–5 cycles with ~200 mL of deionized water) until the supernatant reached pH∼6. To delaminate, the etched multilayer Mo2TiC2Tx MXene sediment was added to 5 mL of tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAOH) solution (25 wt% stock, Fisher Scientific) in 15 mL of deionized water per gram of MAX. The mixture of TMAOH and etched multilayered MXene was then stirred at 300 rpm for 4 h at 55 °C. After delamination, the Mo2TiC2Tx MXene solution was washed to neutral pH via repeated centrifugation and decantation in the Thermo Scientific centrifuge at 21,913 RCF (4 cycles with ~200 mL of deionized water). Thereafter, the final mixture was re-dispersed in 15 mL of deionized water and vortexed for 15 min. The suspension was then centrifuged in the Thermo Scientific centrifuge at 2795 RCF for 30 min to ensure the Mo2TiC2Tx MXene solutions were single-to-few-layered flakes, as shown in Fig. 5c.

Fabrication of SnS, SnS/Ti3C2Tx and SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx

The fabrication of the SnS device was done by simple drop-casting of SnS on the ITO/PET substrate by taking silver contacts on SnS, followed by the drying process. The fabrication of the SnS/Ti3C2Tx and SnS/Mo2TiC2Tx device was carried out by drop-casting Ti3C2Tx and Mo2TiC2Tx on ITO/PET substrate. We dissolved 2 wt% of Ti3C2Tx and Mo2TiC2Tx MXenes in DI water, followed by drying. Finally, SnS was drop cast on Ti3C2Tx and Mo2TiC2Tx after taking Ag contacts on Ti3C2Tx and Mo2TiC2Tx, as can be seen in Fig. 5d. The film thickness was controlled by optimizing the concentration of precursor solutions (2 wt.% MXene dispersion, ~5 mg/mL SnS suspension) and the drop-casting volume (~20–30 µL per deposition), followed by drying at 70 °C to ensure uniform films. The drop-casting was repeated to achieve a consistent film thickness of ~200–250 nm, confirmed by FESEM cross-sections. To ensure reproducibility, all devices were fabricated under identical conditions, and over ten devices were tested, which consistently exhibited similar I–V characteristics and responsivity values with <5% variation. Furthermore, the contacts on the devices were taken using silver paste. The reason for that is that for SnS/Ti3C2Tx and SnS/ Mo2TiC2Tx, MXene acts as a transport layer as well as a contact, and silver paste is utilized to have the connection to the external circuitry with copper wires.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are included in the paper. The corresponding author can also provide additional data upon reasonable request.

References

Qiu, Q. & Huang, Z. Photodetectors of 2D materials from ultraviolet to terahertz waves. Adv. Mater. 33, 1–19 (2021).

Guo, D. et al. Visible-blind ultraviolet narrowband photomultiplication-type organic photodetector with an ultrahigh external quantum efficiency of over 1 000 000%. Mater. Horiz. 8, 2293–2302 (2021).

Jiang, J. et al. Recent advances in 2D materials for photodetectors. Adv. Electron. Mater. 7, 1–27 (2021).

Sahatiya, P., Reddy, C. S. K. & Badhulika, S. Discretely distributed 1D V2O5 nanowires over 2D MoS2 nanoflakes for an enhanced broadband flexible photodetector covering the ultraviolet to near infrared region. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 5, 12728–12736 (2017).

Selamneni, V., Anand, P. P., Singh, A. & Sahatiya, P. Hybrid 0D-2D WS2-QDs (n)/SnS (p) as distributed heterojunctions for highly responsive flexible broad-band photodetectors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 3, 4105–4114 (2021).

Sunny, A. & Al Ahmed, S. R. Numerical simulation and performance evaluation of highly efficient Sb2Se3 solar cell with tin sulfide as hole transport layer. Phys. Status Solidi B Basic Res. 258, 1–14 (2021).

Baba, A., Onishi, K., Knoll, W. & Advincula, R. C. Investigating work function tunable hole-injection/transport layers of electrodeposited polycarbazole network thin films. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 18949–18955 (2004).

Adepu, V. et al. High-performance visible light photodetector based on 1D SnO2 nanofibers with a Ti3C2Tx(MXene) electron transport layer. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 6852–6863 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Electron-transport layers employing strongly bound ligands enhance stability in colloidal quantum dot infrared photodetectors. Adv. Mater. 34, 1–8 (2022).

Selamneni, V., Adepu, V., Raghavan, H. & Sahatiya, P. Ultra-high responsivity and enhanced trap assisted charge transfer by utilizing Ti3C2TX(MXene) as a transport layer for ReS2 based flexible broadband photodetector: a better alternative to graphene. FlatChem 33, 100363 (2022).

Polumati, G., Adepu, V., Kolli, C. S. R., Reji, J. & Sahatiya, P. Band alignment study of 2D-2D heterointerface of MoSe2 with Ti3C2Tx (transport layer) for flexible broadband photodetection. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 153, 107161 (2023).

Lei, J. C., Zhang, X. & Zhou, Z. Recent advances in MXene: Preparation, properties, and applications. Front. Phys. 10, 276–286 (2015).

Zhan, X., Si, C., Zhou, J. & Sun, Z. MXene and MXene-based composites: Synthesis, properties and environment-related applications. Nanoscale Horiz. 5, 235–258 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. Two-dimensional Ti3C2MXene-based nanostructures for emerging optoelectronic applications. Mater. Horiz. 8, 2929–2963 (2021).

Di Vito, A., Pecchia, A., Auf der Maur, M. & Di Carlo, A. Nonlinear work function tuning of lead-halide perovskites by MXenes with mixed terminations. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1–7 (2020).

Yu, Z. et al. MXenes with tunable work functions and their application as electron- and hole-transport materials in non-fullerene organic solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 7, 11160–11169 (2019).

Huang, C., Shi, S. & Yu, H. Work function adjustment of Nb2CTx nanoflakes as hole and electron transport layers in organic solar cells by controlling surface functional groups. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 3464–3472 (2021).

Agresti, A. et al. Titanium-carbide MXenes for work function and interface engineering In perovskite solar cells. Nat. Mater. 18, 1228–1234 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Work-function-tunable MXenes electrodes to optimize p-CsCu2I3/n-Ca2Nb3-xTaxO10 junction photodetectors for image sensing and logic electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 1–8 (2022).

El-Demellawi, J. K. et al. Tuning the work function of Ti3C2TxMXene by molecular doping without changing its surface functional groups. ACS Mater. Lett. 4, 2480–2490 (2022).

Roy, P., Rekhi, L., Koh, S. W., Li, H. & Choksi, T. S. Predicting the work function of 2D MXenes using machine-learning methods. J. Phys. Energy 5, 1–18 (2023).

Qamar, S. et al. Recent progress in use of MXene in perovskite solar cells: for interfacial modification, work-function tuning and additive engineering. Nanoscale 14, 13018–13039 (2022).

Hou, C., Huang, C., Yu, H. & Shi, S. Surface-engineered Ti3C2Tx with tunable work functions for highly efficient polymer solar cells. Small 18, 1–11 (2022).

Hong, W., Wyatt, B. C., Nemani, S. K. & Anasori, B. Double transition-metal MXenes: Atomistic design of two-dimensional carbides and nitrides. MRS Bull. 45, 850–861 (2020).

Anasori, B. et al. Control of electronic properties of 2D carbides (MXenes) by manipulating their transition metal layers. Nanoscale Horiz. 1, 227–234 (2016).

Tahir, R., Hakim, M. W., Murtaza, A., Khan, M. F. & Rizwan, S. First Observation of induced ferroelectric and magnetoelectric properties in pristine and Ni-Intercalated Mo2TiC2Tx double transition metal MXene. Adv. Electron Mater. 9, 1–7 (2023).

Khaledialidusti, R., Mishra, A. K. & Barnoush, A. Atomic defects in monolayer ordered double transition metal carbide (Mo2TiC2T: X) MXene and CO2 adsorption. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 8, 4771–4779 (2020).

Aftab, S. & Hegazy, H. H. Emerging trends in 2D TMDs photodetectors and piezo-phototronic devices. Small 19, 2205778 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. Piezo-photovoltaic effect in monolayer 2H-MoS2. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 3549–3553 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. Piezo-phototronic effect in 2D α-In2Se3/WSe2 van der Waals heterostructure for photodetector with enhanced photoresponse. Adv. Opt. Mater. 9, 2100864 (2021).

Ouyang, W., Geng, H. & Wang, J. Improved self-powered photoresponse of ZnO nanorods/SnS nanosheets/PEDOT:PSS heterostructure by pyro-phototronic effect. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 11, 2400430 (2024).

Sarkar, A. S. et al. Liquid phase isolation of SnS monolayers with enhanced optoelectronic properties. Adv. Sci. 10, 1–12 (2023).

Badawi, A. Engineering the optical properties of PVA/PVP polymeric blend in situ using tin sulfide for optoelectronics. Appl Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process 126, 1–12 (2020).

’t Hooft, G., Vandoren, S. & ’t Hooft, S. E. Chapter 45: 10−3. in Time in Powers of Ten 169–172. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789814494922_0045 (2014).

Norton, K. J., Alam, F. & Lewis, D. J. A review of the synthesis, properties, and applications of bulk and two-dimensional tin (II) sulfide (SnS). Appl. Sci. 11, 1–36 (2021).

Liu, G. et al. Vertically aligned two-dimensional SnS2 nanosheets with a strong photon capturing capability for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 5, 1989–1995 (2017).

Krishnamurthi, V. et al. Liquid-metal synthesized ultrathin SnS layers for high-performance broadband photodetectors. Adv. Mater. 32, 1–10 (2020).

Alagarasan, D. et al. Effect of annealing temperature on SnS thin films for photodetector applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 33, 4794–4805 (2022).

Aftab, S. & Hegazy, H. H. Emerging trends in 2D TMDs photodetectors and piezo-phototronic devices. Small 19, 1–24 (2023).

Dai, B. et al. Piezo-phototronic effect on photocatalysis, solar cells, photodetectors and light-emitting diodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 13646–13691 (2021).

Pan, L. et al. Advances in piezo-phototronic effect enhanced photocatalysis and photoelectrocatalysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1–25 (2020).

Selamneni, V., Sukruth, S. & Sahatiya, P. Performance Enhancement of Highly Flexible SnS(p)/MoS2(n) Heterostructure based Broadband Photodetector by Piezo-phototronic Effect. FlatChem 33, 100379 (2022).

Schultz, T. et al. Surface termination dependent work function and electronic properties of Ti3C2Tx MXene. Chem. Mater. 31, 6590–6597 (2019).

Fang, H. et al. Stabilizing Ti3C2Tx MXene flakes in air by removing confined water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2400084121 (2024).

Xia, J. et al. Physical vapor deposition synthesis of two-dimensional orthorhombic SnS flakes with strong angle/temperature-dependent Raman responses. Nanoscale 8, 2063–2070 (2016).

Devika, M. et al. The effect of substrate surface on the physical properties of SnS films. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 21, 1495–1501 (2006).

Yao, W. et al. ZnS-SnS@NC heterostructure as robust lithiophilicity and sulfiphilicity mediator toward high-rate and long-life lithium-sulfur batteries. ACS Nano 15, 7114–7130 (2021).

Jiang, Y. et al. Structural phase transformation from SnS2/reduced graphene oxide to SnS/sulfur-doped graphene and its lithium storage properties. Nanoscale 12, 1697–1706 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Ultrasmall SnS nanoparticles embedded in carbon spheres: a high-performance anode material for sodium ion batteries. RSC Adv. 6, 95805–95811 (2016).

Dar, M. A., Govindarajan, D. & Dar, G. N. Comparing the electrochemical performance of bare SnS and Cr-Doped SnS nanoparticles synthesized through solvothermal method. Phys. Solid State 63, 1343–1350 (2021).

Brent, J. R. et al. Tin(II) sulfide (SnS) nanosheets by liquid-phase exfoliation of herzenbergite: IV–VI main group two-dimensional atomic crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 12689–12696 (2015).

Mathis, T. S. et al. Modified MAX phase synthesis for environmentally stable and highly conductive Ti3C2 MXene. ACS Nano 15, 6420–6429 (2021).

Thakur, A. et al. Step-by-step guide for synthesis and delamination of Ti3C2Tx MXene. Small Methods 7, 2300030 (2023).

Halim, J. et al. Transparent conductive two-dimensional titanium carbide epitaxial thin films. Chem. Mater. 26, 2374–2381 (2014).

Kim, S. J. et al. Metallic Ti3C2Tx MXene gas sensors with ultrahigh signal-to-noise ratio. ACS Nano 12, 986–993 (2018).

Rozmysłowska-Wojciechowska, A. et al. Surface interactions between 2D Ti 3 C 2 /Ti 2 C MXenes and lysozyme. Appl Surf. Sci. 473, 409–418 (2019).

Kolli, C. S. R. et al. Broadband, ultra-high-responsive monolayer MoS2/SnS2 quantum-dot-based mixed-dimensional photodetector. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 15415–15425 (2022).

Polumati, G. et al. Modulation of Schottky barrier height by nitrogen doping and its influence on responsivity of monolayer MoS2 photodetector. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 10, 2202108 (2023).

Selamneni, V., Sukruth, S. & Sahatiya, P. Performance enhancement of highly flexible SnS(p)/MoS2(n) heterostructure-based broadband photodetector by piezo-phototronic effect. FlatChem 33, 100379 (2022).

Polumati, G. et al. Band type engineering using different stacking configurations of anisotropic and isotropic monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. 2D Mater. 10, 045032 (2023).

Polumati, G. et al. Mixed-dimensional van der Waals heterostructure (2D ReS2/0D MoS2 quantum dots)-based broad spectral range with ultrahigh-responsive photodetector. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c02295 (2024).

Schranghamer, T. F. et al. Ultra- scaled phototransistors based on monolayer MoS₂. Device 1, 100102 (2023).

Wu, J. et al. High-sensitivity, high-speed, broadband mid-infrared photodetector enabled by a van der Waals heterostructure with a vertical transport channel. Nat. Commun. 16, 564 (2025).

Liu, X. et al. Enhanced response speed in 2D perovskite oxides-based photodetectors for UV imaging through surface/interface carrier-transport modulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 48936–48947 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Scrolling bilayer WS₂/MoS₂ heterostructures for high-performance photo-detection. Nano Res. 13, 959–966 (2020).

Gomathi, P. T., Sahatiya, P. & Badhulika, S. Large-area, flexible broadband photodetector based on ZnS–MoS₂ hybrid on paper substrate. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1701611 (2017).

Chen, S. et al. Carrier recombination suppression and transport enhancement enable high-performance self-powered broadband Sb2Se3 photodetectors. InfoMat 5, e12400 (2023).

Adepu, V. et al. High-performance visible light photodetector based on 1D SnO2 nanofibers with a Ti3C2Tx (MXene) electron transport layer. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 6852–6863 (2022).

Hou, K. et al. A hydrothermally synthesized MoS₂(1−x)Se₂x alloy with deep-shallow level conversion for enhanced performance of photodetectors. Nanoscale Adv. 2, 2185–2191 (2020).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133–A1138 (1965).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H–Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Yu, Q. et al. Highly sensitive strain sensors based on piezotronic tunneling junction. Nat. Commun. 13, 778 (2022).

Adepu, V., Kunchur, A., Tathacharya, M., Mattela, V. & Sahatiya, P. SnS/Ti3C2Tx(MXene) nanohybrid-based wearable electromechanical sensors for sign-to-text translation and sitting posture analysis. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 4, 1756–1768 (2022).

Thakur, A. et al. Step-by-step guide for synthesis and delamination of Ti3C2Tx MXene. https://doi.org/10.1002/smtd.202300030 (2023).

Acknowledgements

T.D. and S.C. would like to acknowledge Harish-Chandra Research Institute (HRI), Prayagraj, for the infrastructure. Computational work for this study was carried out at the cluster computing facility at HRI Allahabad (http://www.hri.res.in/cluster). T.D. would like to acknowledge DST INSPIRE for funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.P. and A.T. wrote the main manuscript text, C.S.R.K. and S.S. contributed to data analysis, S.D.Y., M.S. and T.D. prepared figures, S.C. and B.A. provided theoretical insights and helped in result interpretation, P.S. supervised the project and finalized the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Polumati, G., Thakur, A., Das, T. et al. MXenes as bipolar transport layer on the performance of SnS-based piezophototronic photodetector. npj 2D Mater Appl 9, 101 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00620-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00620-x