Abstract

The integration of two-dimensional (2D) materials into spintronic devices could enable unconventional computing paradigms, such as stochastic computing, that surpass CMOS in energy efficiency and device density. However, their implementation has faced unexpectedly high coercivity values, increasing the energy cost of magnetic switching. Here, we investigate the origin of this magnetic pinning at the interface between ferromagnetic NiFe and graphene. Vertical spin valves were fabricated using an Uninterrupted Contact Deposition (UCD) technique that prevents interfacial oxidation and contamination. The resulting near-pristine devices exhibit a 25-fold reduction in coercivity, approaching the intrinsic limit of NiFe, as confirmed by magneto-optical and Hanle effect measurements. The importance of suppressing antiferromagnetic exchange bias was highlighted through the introduction of a remote NiO interface that dominates the device’s magnetic anisotropy. These findings establish the intrinsic behavior of 2D spintronic interfaces and clarify the spin-transport mechanism in graphene, offering a platform for future low-power spin-based logic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The future of computation is facing significant challenges as conventional transistor architectures struggle to meet the growing demands of artificial intelligence (AI) applications, which is caused by the inefficiencies of traditional CMOS devices in dealing with complex and dynamic data. To overcome these limitations, stochastic or probabilistic computing has emerged as a powerful alternative1. By leveraging randomness to perform computations, stochastic circuits offer advantages in energy efficiency, fault tolerance, and reduced circuit complexity in encryption2, neuromorphic applications3, and pattern recognition4.

In stochastic circuits, streams of randomly distributed bits represent numerical values that are combined through logical and arithmetic operations, enabling efficient computation with simplified hardware. Spintronics represents a promising realization of stochastic circuit hardware due to its low power and high speed5. By exploiting thermal fluctuations in the magnetization directions, magnetoresistive devices generate bitstreams with probabilistic characteristics, making them ideal candidates for stochastic computing platforms. To maximize the integration density of magnetoresistive devices, vertical architectures are attractive but their large magnetic anisotropy has raised questions about their suitability in the envisioned applications.

The operation of vertical magnetoresistive devices (VMDs) such as magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs) and giant magnetoresistance (GMR) spin valves (SVs) both rely on spin-dependent charge transport between ferromagnetic contacts but differ in the energy required to switch between magnetic states, which controls their energy efficiency6 and switching speed7. MTJs offer high tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR) ratios because of coherent tunneling through crystalline MgO barriers. However, their performance strongly depends on lattice-matched epitaxy between the tunneling barrier and the ferromagnetic electrodes8,9,10. Soft-magnetic electrodes, such as NiFe, suffer from significant lattice mismatch with MgO, which limits coherent tunneling and increases magnetic anisotropy11,12.

Compared to MTJs, spin valves that employ metallic spacers are more compatible with soft magnetic materials and do not require strict lattice matching. This makes them attractive for low-field switching applications. However, similar to MTJs, SVs remain susceptible to interface-related problems including interdiffusion, oxidation, and structural disorder13,14,15,16,17,18,19.

2D materials, such as graphene20,21, transition metal dichalcogenides22,23and hexagonal boron nitride(h-BN)24, could overcome the issues of the traditional ferromagnet/spacer interface in both MTJs and SVs. The unique bonding structure in these atomically thin, layered structures minimizes interdiffusion into the ferromagnet. Moreover, the inert nature of 2D material surfaces limits the out-of-plane bonding character to van-der-Waals bonds with low strain and disorder transfer. This van der Waals integration also relaxes lattice matching requirements25, offering a key advantage over conventional VMD barriers. Finally, many 2D materials, such as graphene and phosphorene, exhibit only weak spin-orbit coupling, thus reducing the anticipated magnetic anisotropy26.

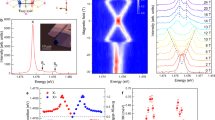

Despite their theoretical advantages, experimental demonstrations of magnetoresistive devices incorporating 2D materials have not yet achieved significantly lower coercivity27,28,29,30,31,32 compared to conventional devices12,13,14,15,17,18,33,34,35, as shown in Fig. 1(a). This discrepancy between experiments and theoretical predictions has been attributed to multiple factors. The coupling of ferromagnets to defects was predicted to enhance magnetic anisotropy36,37. Moreover, the electronic interaction between both materials was suggested to enhance this effect38,39. Finally, the introduction of adsorbates during 2D materials processing leads to oxide formation at the interface, which could cause magnetic pinning at the interface27,29,30,31,32,40.

a Comparison of coercivity values at room temperature for various VMDs extracted from the literature, along with the intrinsic coercivity of their respective ferromagnetic contacts. The coercivity of our device, determined by MOKE measurements, is highlighted in red. (inset) corresponding comparison at low temperatures, where the coercivity of our device is highlighted in red and extracted from magnetoresistance measurements conducted at 10 K. The numerical labels correspond to the reference numbers listed in Supplementary Table S1, which provides detailed information on each device and its measurement conditions. b schematic of the UCD deposition process, c illustration showing graphene in contact with both electrodes, d Raman mapping of suspended graphene, e representative Raman spectra of suspended and supported graphene, shown in blue and red, respectively, and f SEM image of suspended graphene covered by a NiFe thin film.

We here investigate the origin of magnetic anisotropy in 2D barrier-integrated vertical magnetoresistive devices and explore the limits of minimizing it. Using a recently developed Uninterrupted Contact Deposition (UCD) fabrication method, ultra-clean interfaces were realized between NiFe ferromagnet and a graphene spacer. Spintronic devices composed of such improved interfaces exhibit a 25-fold reduced coercivity compared to traditional devices, achieving values close to the limit imposed by the bulk magnetic properties of the contact19,41,42,43.

The realization of structures with near-intrinsic response44 allows us to explore the hypothesis that oxide-mediated interfacial exchange interactions27,29,31,45,46 are the origin of traditionally high coercivities of 2D spintronic devices. Using a remote NiO interface as a model system, we established the importance of magnetic pinning as the origin of previous limitations of 2D spintronic devices and also address the ambiguity in the operating mode of graphene-based spin-based devices.

Results

We have previously described a fabrication technique that is designed to achieve 2D materials integration with ultraclean interfaces44. This approach relies on the simultaneous deposition of two magnetic contacts on a suspended 2D material layer (Fig. 1(b)). For this purpose, a silicon nitride membrane was patterned onto a silicon substrate via plasma exposure, and holes were fabricated by sequential reactive ion etching and anisotropic wet etching. Then, CVD-grown graphene47 was transferred onto the holey substrate using established procedures39, followed by thermal annealing to remove residual PMMA48.

The suspended graphene is then attached to a rotating holder within the high-vacuum chamber of an e-beam evaporator system. This setup allows ferromagnetic electrodes to be deposited on both sides of the graphene simultaneously (Fig. 1(c)). This fabrication process ensures that the ferromagnetic contacts are formed entirely under vacuum conditions, thereby preventing any exposure of the interface to ambient air. Such an uninterrupted contact has previously been shown to yield atomically clean interfaces, which reduce spin accumulation and substantially enhance the operational efficiency of spintronic devices44.

Raman spectroscopic mapping confirmed the continuity of the suspended graphene by showing the presence of the G-band feature over the orifice areas. (Fig. 1(d)). A notable distinction was observed between the supported and suspended areas. Remarkably, the suspended graphene segment exhibits a downward shift in the G-band feature, suggesting the relaxation of transfer-induced tensile strain (Fig. 1(e))49. Scanning electron microscopy confirms that the suspended graphene is retained even after thermal evaporation deposition of metals. (Fig. 1(f)).

Utilizing UCD, we can avoid common issues in 2D materials-based spintronic devices, such as contamination, which have been suggested to cause high coercivity. We therefore term this device Pristine-SV, as it is expected to reveal the near-intrinsic response of the graphene/ferromagnet injector (Fig. 2(a)).

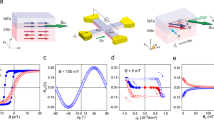

a Geometry of the electrical measurement setup for the pristine-SV, b cross-sectional SEM image of the pristine-SV, c geometry of the electrical measurement setup for the pinned-SV, d cross-sectional SEM image of the pinned-SV, e I-V characteristics of the pristine-SV demonstrating Ohmic contact with linear behavior; electrical properties at 10 K and 300 K are shown in blue and red, respectively, and f I-V characteristics of the pinned-SV, demonstrating Ohmic contact with linear behavior; electrical properties at 10 K and 300 K are shown in blue and red, respectively.

A second device structure is designed to test the hypothesis that oxide-mediated exchange interactions increase magnetic anisotropy and are responsible for the high coercivity27,29,30,31,40,45,46. For this purpose, we deliberately introduce a NiO pinning layer, as the material is known to produce in-plane antiferromagnetic domains50. While significant impact on the coercivity of adjacent ferromagnets was reported even in ultrathin NiO51, we chose to produce a thick NiO film to provide unambiguous evidence of antiferromagnetic pinning and termed the device “Pinned-SV52,53. To disentangle the pinning effect from interfacial contamination, we introduce a remote NiO interface behind the bottom contact without access to the actual device’s interface (Fig. 2(c)). Figures 2(b), (d) compare the cross-sectional SEM images of the pristine-SV and pinned-SV. The contrast of the graphene layer permits the distinction of the NiFe bottom and top layers. The thicknesses of the top NiFe and bottom NiFe contacts are 55 nm and 45 nm, respectively (Fig. 2(b)). For the pinned-SV, a layer of NiO of 21 nm can be discerned. (Fig. (2d))

To assess the interface contact quality within the junction, electrical measurements were conducted through the NiFe contact, circumventing the NiO pinning layer (Fig. 2(a,c)). The current-voltage characteristics for both devices demonstrate Ohmic contact at both room temperature and 10 K, indicating a metallic interfacial contact forms at the junction (Fig. 2(e, f))27. This electric behavior emphasizes efficient charge carrier injection and minimal resistance at the interface. Moreover, the absence of a tunneling barrier, together with the observed linear I–V characteristics, is consistent with the presence of giant magnetoresistance (GMR)-type transport. This result provides new evidence for a previously observed ambiguity in the application of 2D materials in spintronic devices. Some studies have reported that graphene behaves as an insulator due to the momentum mismatch of the Fermi spheres of graphene (which is centered around the K points) and the ferromagnet, resulting in tunneling transport54,55,56. Conversely, other studies suggest that this structure functions as a spin valve due to graphene’s inherent conductivity, and changes in the transport are due to the GMR effect27,29,40,45,57. Our results confirm that even in the absence of interfacial contamination or magnetic pinning, the GMR effect is dominant throughout the investigated temperature range.

Finally, the observed current density in both devices reaches the impressive level of 108 A/m2, which rivals the conductance of monolayer graphene reported by Debroy58 and meets the standards of high-quality electronic devices44, underscoring the exceptional performance of UCD deposition in achieving efficient carrier transport. The difference in resistance between the two devices is attributed to the interface pinning effect59 which is confirmed by the larger decrease in resistance for pristine devices upon cooling.

With the similarity of the ferromagnet/2D material interface established, we turn to investigate the magnetic properties of both pristine and pinned SVs. Magneto-optic Kerr effect (MOKE) measurements were employed to analyze the magnetic hysteresis by detecting the polarization of reflected light within a sample area. For the pinned-SV, a coercivity of 94 Gauss at room temperature is observed (Fig. 3(a)). The coercivity value is consistent with previous reports on exchange bias phenomena observed in NiO-NiFe films60. The comparable coercivity observed in the pinned-SV and previously reported devices suggests that the performance limitations of traditional structures stem from the antiferromagnetic–ferromagnetic (AFM–FM) exchange bias coupling between NiFe and NiO60,61,62. The MOKE characterization of the pristine interface, pristine-SV on the other hand, reveals near-zero coercivity ( < 6 Gauss), which confirms the potential of 2D material spintronic devices for low-power switching applications.

a MOKE measurement of pinned-SV at room temperature, showing 94 Gauss coercivity, b MOKE measurement of pristine-SV at room temperature, showing a significantly lower coercivity of 6 Gauss, c dotted data points represent the MR results of pinned-SV at 10 K under an in-plane magnetic field, with the Lorentz fitting curve shown in red. The vertical dashed line in the middle indicates the center position of the fitted curve, illustrating a 152.4 Gauss shift caused by coercivity, and d dotted data points represent the MR results of pristine-SV at 10 K under an in-plane magnetic field, with the Lorentz fitting curve shown in red. The vertical dashed line in the middle indicates the center position of the fitted curve, illustrating a 6 Gauss shift caused by coercivity.

MOKE characterization cannot resolve the location of the 2D material interface and instead averages over Si3N4 areas where graphene is not suspended and only in contact with one electrode. To provide a more localized picture, we conduct magneto-transport measurements since carrier transport is limited to the orifices where both metal electrodes are in direct contact with graphene. We extract an MR ratio of 2.3% for pinned-SV, which represents excellent performance compared to similar reports28,29,30,31,40 (See Table 1). The pristine-SV is expected to have a lower MR ratio due to the soft ferromagnetic nature of NiFe, but still outperforms (1.3%) previous graphene-based SV devices.

When analyzing the magnetoresistance in more detail, we observe an asymmetric shape (Fig. 3(c,d)). This behavior is due to the energy required to reorient the ferromagnetic contacts as the magnetic field is gradually changed from negative to positive values. The MR curve of the pristine-SV shows an 8% narrower FWHM compared to the pinned-SV, indicating a steeper slope of resistance with the application of a magnetic field. This analysis supports the conclusion that intrinsic 2D materials-based junctions can enhance sensor sensitivity through improvements in both coercivity and MR curve characteristics. Moreover, the pinned-SV exhibits a shift of 152.4 Gauss from the zero value, which is comparable to previous reports52 while pristine-SV only shows a -6.7 Gauss shift. The consistent trend of increased coercivity obtained from MOKE and magneto-transport measurements indicates that the coercivity is dominated by the exchange bias effect between ferromagnetic NiFe and antiferromagnetic NiO, rather than from any unexpected oxidation at the interface62,63.

Finally, the MR curves presented in Fig. 3(c), (d) display a smooth, gradual transition rather than a sharp, abrupt jump. This behavior is characteristic of current-perpendicular-to-plane giant magnetoresistance (CPP-GMR) systems64,65,66,which differ from tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR) devices that typically exhibit well-defined hysteresis19,67,68. The observed MR response aligns with the linear current-voltage characteristics shown in Fig. 2(e), (f), further supporting the presence of metallic transport along the out-of-plane direction.

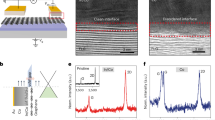

To increase the measurement precision of the coercivity values, we utilize the Hanle effect69,70. The application of a perpendicular magnetic field induces spin precession that causes an abrupt change in carrier injection and thus provides a measure of coercivity with high resolution71 (Fig. 4(a)). A comparison of the Hanle measurements (Fig. 4(b, c)) of pristine and pinned SV confirms our previous findings. An observed higher zero-field voltage in pinned-SV corroborates the aforementioned increased potential barrier due to the additional AFM layer. Moreover, a decrease in spin lifetime is evidenced by a higher FWHM upon magnetic field application, which is attributed to the exchange bias interaction between the pinned layer and the ferromagnetic layer72,73. This interaction increases spin dephasing and scattering. In contrast, the pristine-SV displays a sharper curve in the Hanle measurement (Fig. 4(b)), suggesting that the absence of the pinned layer improves spin lifetime.

a Illustration of the Hanle effect at the pristine and pinned interface. The top schematic (pinned-SV) shows increased spin accumulation from exchange bias induced by the underlying NiO layer, while the bottom (pristine-SV) illustrates more efficient spin transport without interfacial pinning. b Hanle measurement of the pristine-SV, showing a low voltage ( ~ 0.013 V) at zero field conditions. c Hanle measurement of the pinned-SV, with blue and red curves indicating field sweeps in opposite directions. The shift reflects enhanced coercivity and a fourfold higher voltage indicates greater spin accumulation than the pristine device. d Zoom-in of (c) showing anisotropic magnetoresistance (AMR) at high fields, offering an alternative estimate of coercivity of 207 Gauss.

To further validate the coercivity characteristics observed in the Hanle measurements, we employ anisotropic magnetoresistance (AMR) under higher magnetic fields. The pristine-SV remains nearly centered at zero magnetic field (Fig. 4(b)), indicating the absence of any additional coercivity shift. In contrast, the pinned-SV exhibits an increased coercivity of approximately 207 Gauss, estimated by the displacement between the forward and backward AMR curves (Fig. 4(d)). This result further supports our finding that the enhanced coercivity is solely due to the exchange bias coupling between NiO and NiFe, rather than the presence of unexpected oxides at the interface. Additionally, the pronounced AMR effect at higher magnetic fields reinforces the suitability of our devices for sensor applications across a broad range of magnetic fields.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that the performance of traditional spin valves based on 2D materials is significantly impacted by antiferromagnetic pinning of the contacts due to interfacial oxides. Eliminating these oxides results in near-zero coercivity, as evidenced by both global and local measurements. Our findings open up new possibilities for highly sensitive magnetic sensors with low-field detectivity, as well as novel strategies for optimizing energy-efficient magnetic storage solutions.

Methods

Graphene synthesis

Graphene growth followed established procedures as described in the previous study47. In short, a copper foil (99.8%, Alfa-Aesar, no. 13382) underwent pre-annealing at 1000 °C for 30 min in a mixture of Ar and H2 to promote grain growth. Subsequently, methane was introduced at a rate of 10 sccm to initiate graphene synthesis. Following a growth period of 6 h, the sample was allowed to cool naturally under H2 flow.

Characterization of graphene

Raman spectroscopy utilized a 532 nm excitation source within a Nanobase XPER RF setup. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was carried out in a FEI Nova NanoSEM 450 FEG-SEM with a combination of EDX for elemental analysis. To prevent sample curling during FIB etching, we deposited a sufficient amount of Pt thin film as a protective layer on the surface.

Graphene transfer process

Graphene was transferred onto the porous mechanical support via a wet transfer technique. Initially, a layer of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) was applied to the graphene-coated copper foil through spin-coating at 2500 rpm. Following this, the sample underwent immersion in ammonium persulfate to dissolve the copper foil, followed by several rinses in deionized water for cleanliness assurance. The resultant floating membrane was delicately lifted and positioned onto the porous mechanical support. To minimize PMMA residue, the sample underwent thermal decomposition at 400 °C48. This process entailed a flow of 200 sccm of hydrogen (H2) and 200 sccm of argon (Ar) for an hour. Lastly, the sample was allowed to naturally cool in the oven.

Deposition of NiFe and NiO Layers

UCD of NiFe was conducted in an e-beam evaporator (AST E-GUN PEVA-600I) with a rotational system at a pressure of 3 × 10−6 Torr, and a deposition rate of 0.1 Å per second. Similarly, the pinned layer’s NiO was deposited using the same e-beam evaporation process under identical conditions.

Magnetic characterization and transport measurements

To characterize the magnetic properties of NiFe and NiFe/NiO, we examine the hysteresis of optical responses from the surfaces of these metallic films. This investigation employs a custom-built longitudinal magneto-optical Kerr effect (MOKE) system, with an external in-plane magnetic field generated by a Helmholtz coil with negligible magnetic remanence, allowing precise measurement of the hysteresis shift in the samples74. The wide-field polar MOKE measurements were performed using a white-light LED source (broadband visible spectrum, 400–700 nm) under a Köhler illumination configuration integrated into an optical microscope (100× objective, working distance ≈ 1.5 cm). The incident light was linearly polarized by a polarizer, and the reflected beam passed through an analyzer before reaching a CCD camera. The polarizer–analyzer angle was fixed at approximately 80° to maximize the signal-to- noise ratio (ΔI/I ≈ 0.02). The Kerr rotation and depolarization factors were 8 × 10−4 rad and 4.2 × 10−3, respectively. The incident optical power was in the milliwatt range, sufficiently low to prevent sample heating. MR measurements are performed using an AC lock-in amplifier, with an external magnetic field applied to observe variations in resistance under a constant bias current at 10 K.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Daniel, J. et al. Experimental demonstration of an on-chip p-bit core based on stochastic magnetic tunnel junctions and 2D MoS2 transistors. Nat. Commun. 15, 4098 (2024).

Cheong, W. H., In, J. H., Jeon, J. B., Kim, G. & Kim, K. M. Stochastic switching and analog-state programmable memristor and its utilization for homomorphic encryption hardware. Nat. Commun. 15, 6318 (2024).

Yoon, K., Choi, S. & Shin, Y. In 2016 International SoC Design Conference (ISOCC). 73-74 (IEEE).

Canals, V., Morro, A. & Rosselló, J. L. Stochastic-based pattern-recognition analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 31, 2353–2356 (2010).

Zink, B. R., Lv, Y. & Wang, J.-P. Review of magnetic tunnel junctions for stochastic computing. IEEE J. Explor. Solid-State Comput. Devices Circuits 8, 173–184 (2022).

Srinivasan, G., Sengupta, A. & Roy, K. Magnetic tunnel junction based long-term short-term stochastic synapse for a spiking neural network with on-chip STDP learning. Sci. Rep. 6, 29545 (2016).

Han, L. et al. A mechanically strong and ductile soft magnet with extremely low coercivity. Nature 608, 310–316 (2022).

Mandziak, A. et al. Structure and magnetism of ultrathin nickel-iron oxides grown on Ru (0001) by high-temperature oxygen-assisted molecular beam epitaxy. Sci. Rep. 8, 17980 (2018).

Satō, M., Mukasa, K. & Maeda, M. Uniaxial magnetic anisotropy in nickel-iron thin films electrodeposited on scratched surfaces. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 8, 468 (1969).

Satō, M., Tokuda, M. & Maeda, M. Effect of average stress in films on uniaxial magnetic anisotropy in electrodeposited nickel-iron thin films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 9, 491 (1970).

Li, M. et al. Effect of a CoFeB layer on the anisotropic magnetoresistance of Ta/CoFeB/MgO/NiFe/MgO/CoFeB/Ta films. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 439, 17–21 (2017).

Rao, S. et al. Integration of epitaxial permalloy on Si (1 0 0) through domain matching epitaxy paradigm. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 18, 1–5 (2014).

Wang, S. et al. Temperature dependence of giant tunnel magnetoresistance in epitaxial Fe/MgO/Fe magnetic tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 78, 180411 (2008).

Shen, W. et al. Effect of film roughness in MgO-based magnetic tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 182508 (2006).

Yuasa, S., Nagahama, T., Fukushima, A., Suzuki, Y. & Ando, K. Giant room-temperature magnetoresistance in single-crystal Fe/MgO/Fe magnetic tunnel junctions. Nat. Mater. 3, 868–871 (2004).

Katayama, T. et al. Interlayer exchange coupling in Fe∕ MgO∕ Fe magnetic tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 112503 (2006).

Lee, S.-E., Takemura, Y. & Park, J.-G. Effect of double MgO tunneling barrier on thermal stability and TMR ratio for perpendicular MTJ spin-valve with tungsten layers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 182405 (2016).

Bonaedy, T., Choi, J. W., Jang, C., Min, B.-C. & Chang, J. Enhancement of electric-field-induced change of magnetic anisotropy by interface engineering of MgO magnetic tunnel junctions. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 48, 225002 (2015).

Tsunekawa, K. et al. Huge magnetoresistance and low junction resistance in magnetic tunnel junctions with crystalline MgO barrier. IEEE Trans. Magn. 42, 103–107 (2006).

Han, W., Kawakami, R. K., Gmitra, M. & Fabian, J. Graphene spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 794–807 (2014).

Zatko, V. et al. Artificial graphene spin polarized electrode for magnetic tunnel junctions. Nano Lett. 23, 34–41 (2022).

Van et al. Graphene and monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenides: properties and devices. J. Mater. Res. 31, 845–877 (2016).

Wang, W. et al. Spin-valve effect in NiFe/MoS2/NiFe junctions. Nano Lett. 15, 5261–5267 (2015).

Faleev, S. V., Parkin, S. S. & Mryasov, O. N. Brillouin zone spin filtering mechanism of enhanced tunneling magnetoresistance and correlation effects in a Co (0001)/h-BN/Co (0001) magnetic tunnel junction. Phys. Rev. B 92, 235118 (2015).

Vermeulen, P. A., Mulder, J., Momand, J. & Kooi, B. J. Strain engineering of van der Waals heterostructures. Nanoscale 10, 1474–1480 (2018).

Ahn, E. C. 2D materials for spintronic devices. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 4, 17 (2020).

Meng, J., Chen, J.-J., Yan, Y., Yu, D.-P. & Liao, Z.-M. Vertical graphene spin valve with Ohmic contacts. Nanoscale 5, 8894–8898 (2013).

Iqbal, M., Iqbal, M., Jin, X., Hwang, C. & Eom, J. Interlayer dependent polarity of magnetoresistance in graphene spin valves. J. Mater. Chem. C. 3, 298–302 (2015).

Iqbal, M. Z. et al. Spin valve effect of NiFe/graphene/NiFe junctions. Nano Res. 6, 373–380 (2013).

Li, P.-S. et al. Magnetoresistance effect in vertical NiFe/graphene/NiFe junctions. Chin. Phys. B 31, 038502 (2022).

Asshoff, P. et al. Magnetoresistance of vertical Co-graphene-NiFe junctions controlled by charge transfer and proximity-induced spin splitting in graphene. 2D Mater. 4, 031004 (2017).

Mohiuddin, T. M. et al. Graphene in multilayered CPP spin valves. IEEE Trans. Magn. 44, 2624–2627 (2008).

Rao, S. et al. Positive exchange bias in epitaxial permalloy/MgO integrated with Si (1 0 0). Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 18, 140–146 (2014).

Wang, L. et al. Effect of annealing on interfacial spin polarization and resistance in Permalloy/MgO/Ag lateral spin valves. Appl. Phys. Express 4, 093004 (2011).

Godel, F. et al. Epitaxy of MgO magnetic tunnel barriers on epitaxial graphene. Nanotechnology 24, 475708 (2013).

Sahoo, S., Khanna, S. N. & Entel, P. Controlling the magnetic anisotropy of Ni cluster supported on graphene flakes with topological defects. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 043102 (2015).

Bhandary, S., Eriksson, O. & Sanyal, B. Defect controlled magnetism in FeP/graphene/Ni (111). Sci. Rep. 3, 3405 (2013).

Donati, F. et al. Magnetic moment and anisotropy of individual Co atoms on graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 236801 (2013).

Schulz, N. et al. Proximity enhanced magnetism at NiFe2O4/Graphene interface. AIP Adv. 12, 035132 (2022).

Chen, J.-J. et al. Layer-by-layer assembly of vertically conducting graphene devices. Nat. Commun. 4, 1921 (2013).

Silva, E. F. D. et al. Thickness dependence of the magnetic anisotropy and dynamic magnetic response of ferromagnetic NiFe films. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 50, 185001 (2017).

Entani, S., Kiguchi, M., Ikeda, S. & Saiki, K. Magnetic properties of ultrathin cobalt films on SiO2 substrates. Thin Solid Films 493, 221–225 (2005).

Gräfe, J., Schütz, G. & Goering, E. J. Coercivity scaling in antidot lattices in Fe, Ni, and NiFe thin films. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 419, 517–520 (2016).

Huang, T.-C. et al. Realizing high-quality interfaces in two-dimensional material spin valves. ACS Mater. Lett. 6, 94–99 (2023).

Iqbal, M. Z. et al. Interlayer quality dependent graphene spin valve. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 422, 322–327 (2017).

Piquemal-Banci, M. et al. 2D-MTJs: introducing 2D materials in magnetic tunnel junctions. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 50, 203002 (2017).

Hsieh, Y.-P., Kuo, C.-L. & Hofmann, M. Ultrahigh mobility in polyolefin-supported graphene. Nanoscale 8, 1327–1331 (2016).

Ahn, Y., Kim, J., Ganorkar, S., Kim, Y.-H. & Kim, S.-I. Thermal annealing of graphene to remove polymer residues. Mater. Express 6, 69–76 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. The split-up of G band and 2D band in temperature-dependent Raman spectra of suspended graphene. Opt. Laser Technol. 139, 106960 (2021).

Spanke, D. et al. Evidence for in-plane antiferromagnetic domains in ultrathin NiO films. Phys. Rev. B 58, 5201 (1998).

Janus, W. et al. Tunable magnetic anisotropy of antiferromagnetic NiO in (Fe)/NiO/MgO/Cr/MgO (001) epitaxial multilayers. Sci. Rep. 13, 4824 (2023).

Hoshiya, H., Komuro, M., Mitsuoka, K. & Sugita, Y. Giant magnetoresistance of spin valve films with NiO antiferromagnetic films. IEEE Translation J. Magn. Jpn. 9, 236–241 (1994).

De Morais, A. & Petford-Long, A. Spin valve structures with artificial antiferromagnets. J. Appl. Phys. 87, 6977–6979 (2000).

Pan, M. et al. The anisotropic tunneling behavior of spin transport in graphene-based magnetic tunneling junction. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 453, 101–106 (2018).

Cobas, E., Friedman, A. L., van’t Erve, O. M., Robinson, J. T. & Jonker, B. T. Graphene as a tunnel barrier: graphene-based magnetic tunnel junctions. Nano Lett. 12, 3000–3004 (2012).

Piquemal-Banci, M. et al. Magnetic tunnel junctions with monolayer hexagonal boron nitride tunnel barriers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 102404 (2016).

Iqbal, M. Z., Hussain, G., Siddique, S. & Iqbal, M. W. Interlayer reliant magnetotransport in graphene spin valve. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 441, 39–42 (2017).

Debroy, S., Sivasubramani, S., Vaidya, G., Acharyya, S. G. & Acharyya, A. Temperature and size effect on the electrical properties of monolayer graphene based interconnects for next generation MQCA based nanoelectronics. Sci. Rep. 10, 6240 (2020).

Dieny, B., Li, M., Liao, S., Horng, C. & Ju, K. Quantitative interpretation of the magnetoresistive response (amplitude and shape) of spin valves with synthetic antiferromagnetic pinned layers. J. Appl. Phys. 87, 3415–3420 (2000).

Ni, J. et al. Electric control of NiFe/NiO exchange bias through resistive switching under zero magnetic field. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 34, 552 (2023).

Shen, J. & Kief, M. Exchange coupling between NiO and NiFe thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 79, 5008–5010 (1996).

Yu, G., Chai, C., Zhu, F., Xiao, J. & Lai, W. Interface reaction of NiO/NiFe and its influence on magnetic properties. Appl. Phys. Lett. 78, 1706–1708 (2001).

Han, D.-H., Zhu, J.-G. & Judy, J. H. NiFe/NiO bilayers with high exchange coupling and low coercive fields. J. Appl. Phys. 81, 4996–4998 (1997).

Baibich, M. N. et al. Giant magnetoresistance of (001) Fe/(001) Cr magnetic superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2472 (1988).

Diény, B. Giant magnetoresistance in spin-valve multilayers. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 136, 335–359 (1994).

Zahnd, G. et al. Observation of the Hanle effect in giant magnetoresistance measurements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 232405 (2018).

Feng, J., Feng, G., Coey, J., Han, X. & Zhan, W. High inverted tunneling magnetoresistance in MgO-based magnetic tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 102505 (2007).

Teixeira, J. et al. Tunneling processes in thin MgO magnetic junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 262506 (2010).

Wang, J. et al. Spin-optoelectronic devices based on hybrid organic-inorganic trihalide perovskites. Nat. Commun. 10, 129 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Tunable spin characteristic properties in spin valve devices based on hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites. Adv. Mater. 31, 1904059 (2019).

Jaffrès, H., George, J.-M. & Fert, A. Spin transport in multiterminal devices: large spin signals in devices with confined geometry. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 82, 140408 (2010).

Furis, M. et al. Local Hanle-effect studies of spin drift and diffusion in n: GaAs epilayers and spin-transport devices. N. J. Phys. 9, 347 (2007).

Guinea, F. Spin-flip scattering in magnetic junctions. Phys. Rev. B 58, 9212 (1998).

Tsai, T.-Y., Chen, T.-Y., Wu, C.-T., Chan, H.-I. & Pai, C.-F. Spin-orbit torque magnetometry by wide-field magneto-optical Kerr effect. Sci. Rep. 8, 5613 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work received financial support from Academia Sinica (AS-GCS-112-M04 (YH)) and the Ministry of Science and Technology (Taiwan) under grants 113-2112-M-033-013(CC), 112-2112-M-001-051-(YH) and 110-2628-M-002-005-MY3 (MH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ting-Chun Huang: conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, and project administration. Yu-Xin Chen: investigation. Chun-Yi Lin: investigation. Chiashain Chuang: resources and writing—review and editing. Chi-Feng Pai: resources. Ya-Ping Hsieh: resources, writing—review and editing. Mario Hofmann: resources, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, TC., Chen, YX., Lin, CY. et al. Unpinning the magnetic interface between 2D materials and NiFe for ultra-low coercivity spin valves. npj 2D Mater Appl 9, 104 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00624-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00624-7