Abstract

Strain engineering in two-dimensional (2D) materials enables control over topological states, carrier behaviour, and bandgap properties, opening new functionalities for nanodevices. A core need toward advanced applications is stable, atomically thin 2D structures which sustain large strains. Among various strained architectures, nanoscale non-uniform biaxially strained domes, which form when either gases, liquids, or contaminants are trapped beneath 2D crystals are a promising candidate. Domes manifest due to the interplay between elasticity, trapped matter, and van der Waals forces. This review summarises dome fabrication strategies, including top-down and bottom-up approaches, highlighting proton irradiation as a promising route for spatially patterned, highly pressurised domes with varying geometry and well-defined strain profiles. Domes exhibit constant height-to-radius ratios and stable strain profiles and serve as platforms for probing pseudomagnetic fields, exciton transport, adhesion mechanics, etc. Large non-uniform biaxial strain makes 2D domes promising candidates for next-generation nanodevices, which exhibit advanced material properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) materials research has undergone an extraordinary and notable expansion, driven largely by the increasing urgency and demand for the advancement of high-performance devices. Technological growth is primarily due to the pressing need for ultra-sensitive sensors1, emitters and computing elements, which are crucial for advancing modern hardware and ushering in a new technological era. To initiate technological evolution, there is a demand for materials that deliver highly tuneable and versatile modulation of carriers. Materials with superior electronic, optical, chemical and mechanical properties are of significant interest. For these reasons, 2D materials are continuously sought after due to their material-matter interactions and exotic material characteristics, which is of particular importance in quantum information science2.

The most commonly used methods for modulating carriers and altering 2D material properties include i) gating voltages by applying a biased electric field3; ii) optical excitation of carriers into higher states4; iii) chemical doping by introducing different atoms or molecules5; iv) applying mechanical strain using various methods6,7; v) temperature modification8; and vi) inducing magnetic fields9. Carrier modulation can lead to tuneable electronic properties, induce novel quantum phases and enhance sensitivity. 2D materials with advanced material properties due to their atomic thinness are highly anticipated to expand the scope of possible nanodevices in many different applications, including waveguides10, integrated circuits11,12,13, neuromorphic computing14,15, nanoantennae16,17, and mechanical resonators18,19,20.

2D materials include i) graphene21, a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice, which is known for its exceptional electrical conductivity, high mechanical strength and thermal properties22,23, ii) transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), which have the general formula MX2, where M is a transition metal (W and Mo), and X is a chalcogen atom (S, Se and Te), each different TMD exhibits exciting optical, electrical and mechanical properties24,25,26, iii) hexagonal Boron Nitride (hBN) consisting of alternating boron and nitrogen atoms, which is highly regarded due to its insulating properties and chemical stability27,28; and iv) MXenes, a family of 2D carbides and nitrides display a range of properties depending upon their composition and structure29,30,31.

The thickness of 2D materials is generally in the order of mono- to few-layers of basal planes (0.3 nm–several nm). 2D materials come in a variety of different crystal structures, including hexagonal, trigonal and tetragonal forms, and exist in a variety of different space groups, each possessing different physical and chemical properties32,33. Moreover, a different arrangement of atoms in the 2D crystal contribute to varying mechanical, electrical and optical properties. 2D materials also offer unprecedented opportunities in the exploration of advanced applications due to phase-transitions34.

The development of advanced 2D materials is always expanding, with many predicted compounds computationally analysed prior to synthesis for fast assessment35. The common techniques involved for computational screening of 2D materials generally encompass ab-initio calculations using density functional theory (DFT) for predicting electronic, mechanical and optical properties. Moreover, machine learning is playing a vital part in the field, by analysing large datasets and screening through literature, big data and prediction algorithms can be used to solve optimal growing conditions of 2D crystals.

Due to the large surface area to volume ratio in 2D materials, many exotic phenomena are accessible including reduced dielectric screening, enhanced Coulombic interactions, advanced electronic structures, significant toughness and carrier confinement. 2D materials exhibit exciting electronic, optical, optoelectronic, mechanical and magnetic properties, justifying 2D materials as suitable candidates in quantum photonics36, transistors37, and information processing and storage devices38. To access higher-order features or realise control, 2D materials generally need to be coupled with additional mechanisms to enhance carrier formations, such as heterostructures, variable fabrication methods, doping, or the application of mechanical strain to the crystal structure. Other types of engineered 2D material interactions include magic angle twisted graphene39,40, resulting in superconductivity due to correlated physics behaviours. Moreover, WSe2/WS2 hetero-bilayers encompassing twist angles have been shown to demonstrate tuneable, strong, long-range dipole-dipole interactions of interlayer excitons between the bilayers, which is due to quantum exchange correlation effects41. Heterostructure engineering provides a promising platform for the future synthesis of many 2D materials. Furthermore, different combinations of organic-inorganic heterostructures provide a substantial benefit for engineering and tailoring material properties42,43. The techniques selected to modulate carriers and 2D material properties should be simple, reliable and allow for easy integration into nanodevices.

Strain engineering is a relatively simplistic approach toward manipulating atomically thin crystals and their resulting properties. Mechanical strain is applied to either elongate or compress the crystal structure. Strain changes the dimensions of the lattice structure, modifying the electronic, optical, mechanical, and chemical properties44, and polarisation45. Moreover, strain can be applied in uniaxial or biaxial directions, enabling location-dependent strain engineering opportunities via mechanical design. The main mechanisms used for achieving strain engineering include substrate bending46, arcs47, wrinkling48,49, thermal expansion50, and patterning51. Each of these different techniques utilises localised blistering or external mechanisms to apply strain, meaning that a combination of strain-inducing devices can be used simultaneously to increase strain in the crystal. Many 2D materials can withstand significant deformation without breaking, and in some cases, result in strain values up to ~10%52. Such a large tolerance to strain facilitates modifying material properties, which is ideal in nanoscale devices. If large strain can be induced in the form of engineered structures (domes, wrinkles, etc.) without requiring constant stimulus to maintain strain, such structures will serve as important building blocks in future devices.

An innovative approach to achieving large strain in mono- to few-layer 2D materials, whilst maintaining crystal integrity and stability, involves trapping gases, liquids, or contaminants underneath the basal layers of layered materials, which leads to the formation of domes53,54,55,56. When gases, liquids, or other substances are trapped beneath a 2D material, they exert an outward pressure pushing on the material’s adjacent basal layers, manifesting in the formation of localised dome protrusions. Domes form due to the competing van der Waals (vdWs) forces and the elastic energy of the 2D material. Different species can be trapped underneath the 2D crystal, including molecular hydrogen, argon, water and gold nanoparticles. Domes formed by irradiation techniques are typically long-lasting, robust and exhibit large non-uniform biaxial strain fields across the dome's surface. In this review, we highlight advances in the containment of gases, liquids, or nanoparticles beneath the basal layers of 2D materials, resulting in the formation of domes. We provide a detailed review of the fabrication and formation of domes, dome mechanics, adhesion energy between interfaces, merging domes, material properties and future applications. An overview of this review is given in Fig. 1. The rest of this work is organised as follows: Section 2 discusses the different fabrication methods possible for generating nanoscale domes. Section 3 analyses the mechanics of domes based on their resulting geometric profiles. Section 4 reveals how domes act as sensing probes for measuring both 2D material-substrate adhesion energy and the interlayer adhesion energy between basal layers of 2D materials. Section 5 highlights the nature of matter transport using domes and the existence of merging domes. Section 6 reviews carrier modulation in domes, and material properties enabled in biaxially strained 2D domes. Section 7 discusses the use of domes in future applications and devices. Section 8 ends with concluding remarks.

2D dome fabrication techniques

In this section, we highlight the main fabrication techniques available in nanoengineering broadly characterised into top-down and bottom-up approaches. Both approaches are critical for understanding domes, since fabrication affects factors including size, reliability, yield density of domes, trapped matter and overall strain. As fabrication techniques continue to evolve, so does the ability to generate different 2D structures and devices.

Top-down fabrication involves physically or chemically breaking down larger pieces of material into smaller and thinner flakes57,58. Top-down approaches typically start with bulk materials, which are then reduced in size to achieve the desired nanostructures. For instance, in the case of 2D materials, top-down approaches often involve mechanical or chemical exfoliation. Mechanical exfoliation59 involves peeling off thin layers of a material from a bulk sample using adhesive tape; afterward, the resulting flakes are deposited onto a suitable substrate. Chemical exfoliation uses chemical processes to separate the layers of a material, often through the use of intercalating agents that insert themselves between the layers and force basal layers to separate60. Additionally, other top-down approaches include lithographic techniques61,62, where patterns are etched into thin films using various forms of radiation or particle beams.

Bottom-up approaches involve assembling smaller units, such as atoms or molecules into larger structures which grow with time during the fabrication procedure. A very common bottom-up approach is known as chemical vapour deposition63, where gaseous precursors react on a substrate to form thin layers of the desired material, normally having a thickness ranging from mono- to bulk depending on the growth conditions. Another method is molecular beam epitaxy64, which involves the deposition of molecular or atomic beams onto a substrate to form thin films with precise control over thickness and composition. Additional bottom-up approaches can include the direct exfoliation of basal planes from layered materials or the self-assembly of nanostructures through processes such as van der Waals (vdWs) interactions or chemical reactions.

Both top-down or bottom-up fabrication approaches offer distinct advantages and limitations. For instance, top-down methods are often simpler and more cost-effective for producing large quantities of materials, while bottom-up methods provide greater control over the material properties and can achieve higher levels of precision at the atomic scale. Understanding both approaches is essential for comparing domes when considering ease of fabrication (top-down) versus a large yield number (bottom-up), and the type of matter that can be trapped underneath the 2D material.

Perfect domes are considered to have a circular footprint with radius, R, and maximum height at the apex, hm. Generally, the most common approaches to forming domes include depositing monolayer flakes to trap contaminants in different states (solid, liquid); providing external stimuli; intercalating matter; and irradiation methods. Such fabrication techniques trigger the spontaneous or controlled growth of non-uniform biaxially strained domes. Next, we review the most common dome fabrication techniques.

The process of fabricating domes using bulged membranes begins with the deposition of 2D materials over pre-patterned cavities on a substrate (open-hole in the substrate), often referred to as drumheads65, as shown in Fig. 2a. Injecting a gas at the interface between the thin film and its substrate results in the 2D material’s outward expansion forming a dome, as illustrated in Fig. 2b. Cavities are essential for the bulging technique, since cavities enable the direct injection of gas molecules on the underside of the 2D material which creates a differential pressure66. Domes formed through bulging can be generated using either pressure-driven67, or electrically driven techniques68. The properties of many 2D materials, particularly their impermeability69, contribute to the stability of domes created through bulging. Once formed, dome geometries can be controlled based on the applied pressure from the nanocavity side, which is an advantage of the bulging technique. Slippage effects occur between the 2D material and substrate at the edge when the pressure is large and detachment between the 2D material and substrate occurs, creating a complex boundary condition. Larger pressures result in larger domes with greater strain distribution from the edge to the dome apex. A constant stimulus must be maintained for the domes to exist, and without this continuous stimulus, the structures will revert to their (near) original form. Controllable domes can be achieved through the fixed exertion of pressure, moreover, island structures can also be created by increasing the number of annular cavities70, demonstrating various possible nanoscale structures are possible via pressure bulging.

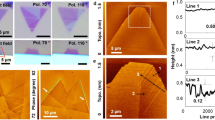

a Side view schematic of a 2D material sitting on top of a pre-patterned nanocavity with circular base footprint (R). b Pressure bulging method where monolayer 2D material membranes are deposited over etched holes. Gas (N2, Argon or Air) is inserted into the test chamber and a pressure is applied on the bottom surface of the membrane, generating a dome. Dome height (hm) can be manipulated via the applied pressure on the bottom surface. In (a) and (b), the 2D material thickness to substrate is not to scale. c Schematic illustration of graphene domes induced by an AFM tip (top). Outward radial pattern of domes created by an AFM tip at different tip voltages74. d Schematic diagram of a water droplet-assisted transfer process forming spontaneous blisters. The process is listed in 6 steps, whereby contaminants are trapped underneath a 2D material resulting in domes77. e Dome inflating/deflating process. i) Optical microscopy image of a proton irradiated (dH = 8 × 1016 protons/cm−2) WS2 sample at T = 300 K. ii) Same as (i) at T = 4 K, resulting in no dome formations. iii) Histogram of the transition temperature at which domes appear81. f Schematic formation of domes due to impinging protons penetrating 2D material basal layers81. g Proton irradiated MoS2 dome engineering using an 80 nm thick mask with opening size (S) when i) S = 3 μm, and ii) S = 1 μm. The diameter of the domes in this case is determined by S and engineered modulation of aspect ratios (hm/R) is possible82. Figure d adapted from Copyright (2022) Wiley. Used with permission from (Wang. W. et al., Mechanical Behaviour of Blisters Spontaneously Formed by Multilayer 2D Materials, Advanced Materials). Figures e and f adapted from Copyright (2019) Wiley. Used with permission from (Tedeschi. D. et al., Controlled Micro/Nanodome Formation in Proton-Irradiated Bulk Transition-Metal Dichalcogenides, Advanced Materials). Figure g adapted from Copyright (2020) Wiley. Used with permission from (Blundo. E. et al., Engineered Creation of Periodic Giant, Nonuniform Strains in MoS2 Monolayers, Advanced Materials Interfaces).

Trapped matter can also be used for the generation of domes via the process of electrical decomposition of molecules. Electrostatic gating and intercalation of matter within nanomaterials can be used for obtaining desired properties in materials54. There have been several attempts made for the formation of bubbles using a variety of different molecules including weakly absorbed ClF371, water splitting72, and radiolysis of interfacial water73, demonstrating the robustness of intercalating different molecules within 2D materials. Figure 2c illustrates the use of an atomic force microscopy (AFM) tip with excellent manoeuvrability for fabricating programmable arrays of 2D domes74. Dome formations can be engineered via AFM tip bias changes. Controllable engineering of domes resulting in uniform size and patterned distributions will be integral for device applications, since it will enable reliable design. Domes can be fabricated by nucleating or reducing intercalated water into hydrogen on Graphene/Mica interfaces during electrolysis75.

A popular top-down approach for fabricating domes is by depositing 2D material over liquids or contaminant molecules and trapping the contents underneath. The ability to encapsulate specific molecules or contaminants can result in various combinations of molecules trapped inside pressurised domes, which may provide interesting chemical and physical interactions. For example, the encapsulation of high-pressure liquids trapped by graphene domes on a diamond substrate provide impermeable sealed edges. Graphene domes have been demonstrated as effective anvil cells for high pressure investigations, and the polymerisation of buckminsterfullerene76. Figure 2d shows the systematic approach to trapping water droplets underneath graphene and MoS2 using a PDMS transfer sheet, known as a wetting transfer method, before depositing the graphene dome with water onto a hBN substrate. The spontaneous formation of multilayer 2D strained surfaces results in a large formation of meta-structures with circular, triangular, pyramidal, and ellipsoidal footprints77. Extensive atomistic molecular dynamics simulations and experiments have also been used to calculate the effect of different contaminants and their influence on the formation of domes. Helium, water, ethanol, hexadecane and NaCl were considered as the encapsulated molecules78, and it was found that material thickness, elastic properties and trapped molecules play a significant part in the resulting geometric profiles of a dome. An interesting approach to the formation of graphene domes was to encase liquid nitrogen with a laser source to engineer position-controllable structures. Interestingly, due to the high pressure of the liquid nitrogen underneath the graphene domes, molecular dynamics simulations reveal an interesting state of solid 2D nitrogen79.

A newer bottom-up approach to the fabrication of 2D domes is achieved through electron beam irradiation80, or proton irradiation of bulk flakes, leading to the manifestation of large numbers of randomly positioned domes as shown in Fig. 2e81. In the case of proton irradiation, domes exist at room temperature (Fig. 2e panel (i)) and disappear at low temperatures (Fig. 2e panel (ii)). Both protons and deuterons realise the formation of domes at the liquid-vapour transition point of molecular hydrogen at 32 K (Fig. 2e panel (iii)), confirming molecular hydrogen forming underneath the TMD layers. When fluctuating around this critical temperature, domes either exist or return to a flat surface. In proton irradiation, a bombardment of protons is accelerated at the surface of a bulk flake and impinge into the first few basal planes of the material as shown in Fig. 2f81. As protons combine with free floating electrons between the TMD layers, molecular hydrogen forms and accumulates, generating a localised internal pressure which pushes outward on the 2D layer(s) above, resulting in protruding domes. Proton irradiation results in a large yield of domes, which are stable over several years, and exhibit excellent mechanical and optical properties. Dome yield can be controlled by the proton source energy and growth conditions. Domes formed via proton irradiation exhibit a universal hm/R aspect ratio depending on material. Moreover, engineering aspect ratio and spatial modulation over the surface of a 2D flake using opaque masks with varying opening sizes (S) is possible, as shown in Fig. 2g82. The ability to predefine footprint radius as S = 3 μm (Fig. 2g panel (i)) or S = 1 μm (Fig. 2g panel (ii)) highlights significant robustness in the fabrication of domes. Since masks can be designed to incorporate various dome footprint radii. Domes fabricated with masks provide a positive route towards nanoscale engineering of large numbers of reliably controlled dome groupings on the surface of a 2D material flake. Along with protons, other noble gases have also been demonstrated for creating domes, including Ar83, He and Ne84. Intentionally created defect sites in graphene Moiré superlattices using ion-irradiation (500 eV, 0.5 μA) has also demonstrated the systematic growth of domes at defect sites85. Many domes form over the surface of graphene with large strain along the dome surface, each exhibiting a pseudomagnetic field (PMF). The density of domes coincides well with the available surface defects in the Ru (001) substrate, however, large temperatures were required > 550 K, compared to the room temperature existence of proton irradiated domes81. Plasma treatment of hBN isolates hydrogen underneath basal planes down to 23 layers, whilst exhibiting universal properties and long term (40 weeks) stability86. Irradiation fabrication techniques compared to other techniques offer significant advantages such as large quantities of domes, room temperature formation, site-specific formation, stimuli-free existence and long-term stability.

Low energy proton beams ( < 20 eV) can be used with the goal of removing defect formations81. However, for large-area or high-throughput production, broad-beam or scanned-beam implantation systems may be required to provide adequate uniform exposure across wafer-scale substrates to form proton irradiated domes over wider surface areas, compared to current laboratory setups. Bulk TMDs must first be integrated as large-area wafers or transferred onto existing substrates prior to proton irradiation, since the TMD substrate is essential for dome formation under irradiation. Other challenges still exist for integrating proton irradiated domes beyond laboratory measurements, particularly their integration with complimentary oxide semiconductor (CMOS) technologies and other common electronics manufacturing processes.

Depending on the required dome characteristics, their stability and the state of trapped matter, different fabrication techniques can be used, offering some design flexibility. For instance, top-down approaches using exfoliation can be used to contain liquids or solid contaminates, however, gases are unable to be trapped with top-down approaches (exfoliation method). On the other hand, gases can penetrate basal layers through irradiation and intercalation. In terms of long-term stability, domes fabricated through proton irradiation have demonstrated existence for several years as free-standing structures without any external stimulus, unlike those formed via pressure bulging. Liquid graphene bubbles have some stability but can merge with other bubbles in their vicinity, whereas gas domes formed through irradiation can exist in different layers. Another key aspect to consider for large scale dome production is the yield of domes that can be made in a single cycle. Most techniques only produce single to few domes; however, irradiation techniques have demonstrated large yields of dome formations (several hundreds) all with varying geometry which exist at room temperature.

Mechanics of biaxially strained 2D domes

In this section, the mechanics of 2D domes including geometric profile, resulting strain distribution and internal pressure is examined. Most experimental results demonstrate that domes exhibit a universal aspect ratio (hm/R), which is dependent upon the 2D modulus of the material, layer thickness, substrate and trapped matter. The universal aspect ratio has been demonstrated using different dome fabrication methods, except for the pressure bulging method, since the material is layered over a cavity and the external pressure stimuli generates a dome. For most 2D materials, including hBN, graphene and TMDs, the observed hm/R is in the range of 0.1 − 0.1881 (meaning the dome apex height is 10 − 18% of the footprint radius), which is measured over numerous samples and across different fabrication methods (i.e. trapped matter, irradiation and intercalation). A universal relationship between the apex height and dome footprint radius is important for potential strain engineering applications involving domes. Hencky’s solution gives the resulting strain at the dome apex, which is in the order of 1 – 2% for many spontaneously formed domes, as shown in Fig. 3a.

a hm versus R of different spontaneously formed MX2 domes. hm/R provides the biaxial tensile strain at the dome apex εm by the inset equation81. b Height profile comparison between an MoS2 dome and FEA. R and hm are 3.76 µm and 618 nm, respectively (left axis is the height coordinate). Strain tensor along the radial (εr), circumferential (εt), and perpendicular (εz) directions calculated from finite element analysis (FEA) (right axis)81. c Numerical calculations of the constant q versus the experimentally obtained region of q depicted by the shaded areas, which highlight the range of aspect ratios measured experimentally over many 2D material dome samples88. d Normalised centre strain comparison between FEA, analytical and experimentally determined strain from Raman experiments88. εr and εϑ refer to εrr and εϑϑ, given by Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively. e Aspect ratio of triangular footprint domes90. f Aspect ratio of pyramidal footprint domes90. g Dome pressure as a function of R for 1-3 L domes. The average hm/R values of 1 − 3 L domes are 0.18, 0.17 and 0.16, respectively97. h Stiffness as a function of R for 1–3 L domes97. i Stable plate to membrane transition mechanics of domes induced by SEM irradiation98. j Engineered domes using a mask with S = 1 μm. The strict boundary condition enable domes to increase in hm/R, enabling biaxial strains up to ~10% at the centre of the dome82. Figures a and b adapted from Copyright (2019) Wiley. Used with permission from (Tedeschi. D. et al., Controlled Micro/Nanodome Formation in Proton-Irradiated Bulk Transition-Metal Dichalcogenides, Advanced Materials). Figures c and d adapted from reprinted (figure) with permission from Blundo, Elena and Yildirim, Tanju and Pettinari, Giorgio and Polimeni, Antonio, Phys. Rev. Lett., 127, 046101, 2021.] Copyright (2021) by the American Physical Society. Figure j adapted from Copyright (2020) Wiley. Used with permission from (Blundo. E. et al., Engineered Creation of Periodic Giant, Nonuniform Strains in MoS2 Monolayers, Advanced Materials Interfaces).

For this review, we treat domes as having an ideal axisymmetric profile of radial coordinate (r) and a height coordinate (h). A shape factor q is applied to account for the different types of shapes that can manifest, including domes, pyramids and tents87. A dimensional dome height profile compared experimentally and using finite element analysis (FEA) is shown in Fig. 3b81. The height profile follows an analytical profile given by88:

Whilst domes exhibit a variety of different or non-ideal axisymmetric behaviour, due to fabrication techniques and slippage along the edges, Eq. (1) provides the most robust form for identifying and analysing domes. Ideally, domes can be considered as fully clamped pressurised membranes. To solve the in-plane displacement field, the equilibrium equations can be solved using the Foppl-von-Karman equation in the membrane regime given by:

where u is the in-plane displacement and v is Poisson’s ratio.

The membrane solution ignores the effect of bending stiffness, which is mostly the case for mono- to few-layer domes. Solving out Eq. (2) leads to the radial and circumferential strain fields along r, and in the strong shear region, the corresponding strain fields are given by88:

where εrr and εθθ are the radial and circumferential strain fields, respectively, and f(v,q) is a shape factor. The finite element analysis (FEA) strain profiles as a function along the radial coordinate is also shown Fig. 3b. The total in-plane strain is given by Eq. (6). Along the surface of a dome, the strain ranges from ~1 – 4%, from the edge to the apex of a dome, for the dome presented in Fig. 3b, respectively, calculated according to:

Whilst, traditional membrane theory uses a q value of 2 for the height prediction model as in Eq. (1), experimental observations and analysing many domes determined q was in the range of 2.1 – 2.25 as shown in Fig. 3c88. Experimental derivation of the strain through Raman spectroscopy, analytical solutions and FEA all validated the radial and circumferential strain as in Fig. 3d. It has also been noted that tents can be accurately represented using Eq. (1), when setting q = 2/387. Large strain in 2D materials and routes towards strain engineering will have significant impacts in future applications, since it can alter the topological and correlated states, bandgap energies, and 2D material properties. Domes exist at various conditions with long lasting stability. Domes may also be controlled or modified through other external factors including electric fields89, offering additional design flexibility of their geometry and modification of εtotal.

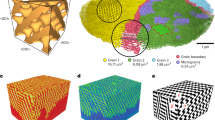

An extension of domes, described by a characteristic length, L instead of R, can come in the form of triangular and pyramidal dome structures, which have been observed in monolayer graphene and hBN containing trapped hydrocarbons. The ratio of hm/L for the triangular and pyramidal footprint domes is shown in Fig. 3e and f, respectively90. Whilst deviant from circular footprint radii, triangular and pyramidal footprint domes still maintain a constant aspect ratio, which is given by hm/L, as 0.07 ± 0.01 for triangular footprint domes, whilst pyramidal footprint domes showed deviations. Other dome footprints which have been observed include polygonal91 and ellipsoids92. Even though different shaped footprint dome structures exist, these protruding features trapping matter mostly exhibit a universal aspect ratio, representing a delicate balance of equilibrium between geometric and material parameters. Classifying the universal aspect ratios is important for strain engineering applications using domes, and dome offsets (referring to domes with non-circular footprints), as it reduces measurements and analysis.

As domes reduce in R, a breaking down of the universal scaling law is expected, leading to different dome mechanics, since bending stiffness begins to dominate and membrane theory no longer captures dome mechanics88. The universal scaling ratio has also been shown to breakdown as R approaches 1 nm, resulting in larger hm/R and pressures exceeding 30 GPa for the smallest domes84. Molecular dynamics simulations of trapped Ar underneath graphene sheets showed that for small footprint radii of 7 nm, pancake shaped domes are possible93. Atomistic approaches also convey a useful approach to solve adhesion energies and elastic energy in continuum media94, and will play an important part for understanding dome growth under different environmental conditions, and the impact on hm/R.

In the case of irradiated domes, the pressure inside a dome including bending stiffness is calculated according to88:

and,

where E2D is the 2D Modulus of the material. ζ(v,q), g(v,q) and μ(v,q) are definitions. D is the bending stiffness, and t is the thickness. From Eq. (11), D is negligible in most cases due to the reliance on t2.

AFM along with inferred methods have been used to determine different elastic properties and internal pressure of domes95. The extraction process is derived from the extensive indentation metrology of clamped ultrathin sheets96, which in the small indentation region relates the indentation stiffness and effective surface tension (stiffness across the dome surface) given in Eq. (12)

where F is the indentation force, δ is the indentation depth, Teff is the effective tension and ρin is the ratio of the radius of the indenter to the radius of the dome. Combining inferred methods with known material parameters such as v enables accurate determination of the resulting properties of domes, however, it is expected there can be some deviation as the internal bond lengths between atoms change due to the outward pressure pushing on the 2D material. To validate the accuracy of using inferred methods for dome properties, numerical simulations were compared against a variety of 1 – 3 L (layer) TMD domes formed from proton irradiation97. Accurate comparison between experimentally derived and FEA derived pressure and stiffness as shown in Fig. 3g and h97, respectively, were obtained between the two methods, whilst accounting for the ρin term. Both pressure and stiffness appear to follow a 1/R relationship with the pressure and stiffness increasing with increasing layer number. Moreover, the stiffness for different dome radii for WS2 domes range from 8 − 20 N/m from 1 L to 3 L. The results were obtained for AFM indentation at the centre with the AFM tip in contact with the dome apex for axisymmetric reasons. Whilst radial dependent comparisons were conducted, deviations between experimental results and FEA began to emerge as the curvature increases, which may be due to the effective area of the contact tip having non-uniform contact or other nonlinear effects. Using the combined experimental data, and inferred method, the 2D modulus of 1 L, 2 L and 3 L WS2 domes were experimentally obtained as E2D = 244.0 ± 35.7, 429.5 ± 37.7, 244.0 ± 35.7, 520.4 ± 49.2 N/m, respectively. The limits of strong shear and weak shear at the interface of domes and tents should also be considered in the mechanics of domes since it will affect slippage at the edge of a dome87. However, even despite slippage effects, most values aligned well, and the elastic parameters of 1 L, 2 L and 3 L WS2 and MoS2 domes were accurately extracted.

Additional mechanisms can also be used to modify dome geometry, which in turn, alters dome mechanics. For instance, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) irradiation can be used to influence the internal matter encapsulated by domes. By using different SEM energy from 1 to 10 kV, domes can transition from bending dominated shells into membranes98. Transitions between plates and membranes severely influences dome mechanics and shape profiles as shown in Fig. 3i. It is expected as the dome size reduces, hm/R reduces, and the influence of bending energy increases. A method for increasing the size of domes and the effective total in-plane strain was achieved with opaque masks with pre-defined S. As shown in Fig. 3j, a dome formed using S = 1 um revealed a potential in-plane strain of up to 10% at the dome apex, due to a larger hm/R value, with an average value of 0.27482, compared to spontaneously formed domes (hm/R = 0.18). Changes in hm can be achieved by increasing the pressure to graphene domes formed via pressure bulging, which alters the dome mechanics. Such a technique was applied in conjunction with Raman experimentation to verify the Grüneisen parameter of interatomic potential for the G, 2D, D and 2D’ peaks with good agreement from previous calculations99.

Understanding the mechanics of nanoscale domes and the inherent total in-plane strain is important for future investigations involving strain engineering of 2D materials and their integration into devices. Due to the relatively simple structure of a dome and the axisymmetric behaviour of ideal domes, the strain along the radial and circumferential coordinates can be calculated at any location. Moreover, optical measurements or AFM measurements for hm/R coupled with dome mechanics enables easy extraction of elastic parameters, strain field calculations, and the internal pressure to be determined, which is a significant advantage of biaxially strained domes, over other nanoscale structures. Whilst intrinsic defects, including vacancies, grain boundaries, and chemical impurities affect 2D materials100,101, and are expected to influence dome mechanics, there is a lack of thorough investigations into their presence and role within 2D domes. In terms of formation, such defects may either aid the nucleation of dome sites or act as local stress concentrators that perturb the curvature, potentially altering hm/R, the associated strain fields, and the resulting material properties.

Probing substrate and interlayer adhesion energy

Since the formation of domes is due to the balance of material properties, trapped matter and vdWs adhesion energy (γ), domes are a probe for experimentally resolving the interfacial adhesion required to maintain surfaces in equilibrium. Adhesion energy can be expressed in two ways as shown in Fig. 4a, such as the substrate adhesion energy (Fig. 4a panel (i)), which refers to the interaction between the 2D material and the substrate, typically formed through top-down fabrication methods, including trapping nanoparticles between graphene-silicon interfaces102. The other form is the interlayer adhesion energy, which is the energy needed to exfoliate layers from adjacent basal planes in a layered 2D material (Fig. 4a panel (ii)). Understanding both types of adhesion energy is important since it describes how 2D materials interact with substrates and how much energy is required to separate layered materials. Moreover, deriving γ is crucial for understanding the energy input required for exfoliating monolayers, which is especially important for the manufacturing of future semiconductors in electronics. Insights into γ directly impacts the efficiency of producing high-quality 2D materials for integration into next-generation electronic devices.

a Schematic of adhesion energy i) when a 2D material is above a substrate material and ii) the interlayer adhesion energy between 2D materials and adjacent basal planes. b i) AFM cross sections of a dome during inflation and deflation via the bulging technique. ii) hm versus R of different domes during inflation and deflation. The upper and lower dashed lines correspond to solutions for separation and adhesion, respectively. iii) A comparison between the works of separation and adhesion for different domes and SiO2 substrate65. c Interlayer adhesion energy of removing 1 L, 2 L or 3 L from the remaining bulk WS2 crystal formed by proton irradiated domes. Experimental and DFT calculations show a similar trend that interlayer adhesion increases with layer number97. d hm/R for different dome number (top) and hm versus R (bottom) of different proton irradiated domes formed on different substrates. For example, MoS2/WS2 refers to MoS2 domes grown on top of a WS2 substrate88. e Interlayer adhesion energy for homo- and hetero-structure domes formed by proton irradiated domes88. Figure b reprinted (adapted) from David Lloyd, Xinghui Liu, Narasimha Boddeti, Lauren Cantley, Rong Long, Martin L. Dunn, and J. Scott Bunch Nano Letters 2017 17 (9), 5329-5334. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society. Figures d and e reprinted (figure) with permission from Blundo, Elena and Yildirim, Tanju and Pettinari, Giorgio and Polimeni, Antonio, Phys. Rev. Lett., 127, 046101, 2021.] Copyright (2021) by the American Physical Society.

In addition to γ, the work of separation and adhesion can also be calculated for domes fabricated via bulging techniques, since membranes deposited over nanocavities exhibit a unique peeling behaviour at their edge boundaries. This process involves inflating and deflating the domes, which leads to complex interactions between the 2D material and the substrate. As pressure is introduced into the membrane, it creates a localised deformation at the membrane’s edges, causing the material to peel away from the substrate at the boundaries of the nanocavities. Peeling is critical because it reflects the dynamic balance of forces acting at the interface, including adhesion, compressive stress, and the mechanical properties of both the membrane and the underlying substrate. Inflating and deflating domes in this manner allows for a detailed investigation into the complex processes involved in separating and adhering a 2D material in contact with a substrate, as shown in Fig. 4b65. When the dome is inflated, the 2D material is pushed away from the surface, which reveals insights into the forces required to detach it from the substrate beyond a critical height, hc, (Fig. 4b panel (i)). Conversely, deflating the dome restores contact between the 2D material and the substrate, providing valuable information on the adhesion strength and the energy required to maintain the interface. Mapping out hm versus R demonstrates the instability with sharp transition points (Fig. 4b panel (ii)). Pressurised membranes (bulging technique) in the form of biaxially strained domes enable investigations into the work of separation and adhesion of 2D materials and substrates (Fig. 4b panel (iii)). Adhesion, stiffness and instability of MoS2 on SiOx substrates using the mechanical blister test derived the adhesion strength at the interface of the two materials as 220 ± 35 mJ/m2. Moreover, Edge-pinning and snap-in transitions were further investigated due to the transition of stable and bi-stable inflation and deflation behaviours65.

Khestanova et al.90 investigated the adhesion energy between MoS2, graphene and hBN domes with trapped hydrocarbons on top of MoS2 and hBN substrates. Different values of hm/R were observed for different material-substrate configurations, which is due to the competition between γ and elastic material properties. Since graphene is lipophilic, γ is expected to be less for graphene on hydrocarbons, resulting in γG = 3.8 ± 0.3 meV Å-2, compared to MoS2 as γMoS2 = 6.8 ± 0.6 meV Å-2.

In terms of interlayer adhesion energy, bottom-up approaches have enabled the experimental derivation of γ in 1 L, 2 L and 3 L TMDs97. Protons are accelerated in an electric field and penetrate several layers deep into the TMD material before interacting with free floating electrons within the basal planes. As a result of protons interacting with electrons, molecular hydrogen accumulates underneath the basal planes, leading to the creation of mono- to few-layer domes. In the case of 1 L, 2 L and 3 L WS2 domes, γ was experimentally obtained as 33.8 ± 3.0, 42.6 ± 2.5 and 45.0 ± 4.2 meV/Å2, all of which are in good agreement with the DFT results of 31.5, 40.3 and 43.5 meV/Å2, respectively as shown in Fig. 4c. This phenomenon highlights the process by which protons can selectively exfoliate different layers from the bulk crystal. There is an apparent increasing trend in the adhesion energy required to exfoliate layers from the bulk crystal as the number of layers increases from 1 L to 3 L. The increasing trend reflects the changing nature of the forces between adjacent layers in TMDs, as more layers are added. Initially, for 1 L materials, the adhesion energy is relatively lower, since the interactions between the single-layer material and the underlying substrate or bulk crystal are weaker. As the number of layers increases to 2 L and 3 L, the interlayer interactions strengthen, and thus more energy is required to separate the layers. Increasing interlayer vdWs forces bind the layers together more strongly with each additional layer.

Blundo et al.88 demonstrated a method for calculating the adhesion energy at interfaces of both biaxially strained 2D homo- and hetero-structure domes. The derivation of γ incorporating q was formulated as:

Equation (13) shows that γ is a function of geometric and elastic material parameters.

Hetero-structure domes also exhibit universal hm/R as shown in Fig. 4d, as confirmed through experiments. Using the experimentally determined hm/R values along with v and q, the resulting γ of both 2D homo- and hetero-structures can be determined as shown in Fig. 4e. Domes act as fast probes for measuring γ, and there are many different fabrication techniques for domes available along with analytical formulations.

Further developing models from the mechanics of domes for considering the interfacial energy of the dome material either on top of a substrate or the interlayer adhesion energy is an exceptional advantage of domes. The ability to determine γ accurately in both homo- and hetero-structures is crucial for designing and optimising 2D material systems. Future engineering of domes may utilise vdWs interactions to influence the formation of wrinkles around mono- and few-layer domes, which is due to slippage instabilities as a result of bending rigidity103.

Matter transport and coalescing states in 2D domes

As domes encapsulate highly pressurised liquids or gases, there is potential for stimulating domes to transport the trapped contents. For example, Shin et al.104 investigated the formation, evolution and vanishing of nanobubbles formed through a top-down approach, using water encapsulated by a graphene membrane, which is commonly referred to as a graphene liquid cell. Figure 5a shows the time evolution of different kinds of single and double liquid filled nanobubbles, demonstrating vanishing, stable, Ostwald ripening and coalescing nanobubbles. The analysis of a single nanobubble in terms of time, internal pressure and radius change is shown along with the Ostwald-ripening process is shown in Fig. 5b-e. The gas transport through ultrathin membranes was shown to be different from conventional gas transport mechanisms104. Domes in liquid graphene cells tend to merge in shapes having an elliptical footprint, and this shape distortion is induced by the driving force or the merging process105. Further studies into liquid transport using bubbles (domes) are still needed.

a Time evolution of different kinds of single and double liquid filled nanobubbles. Images obtained via TEM showing vanishing, stable, Ostwald ripening-like merging process and coalescing bubbles104. b, c Analysis of a single nanobubble showing the average radius and internal pressure changes of vanishing (b) and stable nanobubbles with time (c)104. d Time evolution of radius of growing (red), vanishing (blue) nanobubble and measured inter-bubble distance104. e Calculated internal pressure range of Ostwald ripening nanobubbles104. f Schematic illustration of a H2 filled joint bi-dome formation via proton irradiation97. g SHG mapping of joint bi-domes, the 1 L dome was deliberately burst using AFM indentation, whilst the 2 L and 3 L domes survived. After the bursting of the 1 L dome (right), a 2 L region and a 1 L region coexist over the 2 L dome’s surface, simultaneously97. h Side- and top-view schematic showing the configuration of the layers in a joint bi-dome after bursting. i Histogram of variant Plateau’s law in bi-dome gas filled WS2 domes97. j Histogram of variant Plateau’s law in tri-dome gas filled WS2 domes97. k AFM image of a WS2 tri-dome system, consisting of 1 L, 2 L and 3 L domes joint together97. l Stiffness mapping image of the tri-dome configuration given in (k)97.

Coalescing domes also occur in biaxially strained domes encapsulating gases. With the formation of gases using a bottom-up approach, molecular hydrogen in different layers form as shown in Fig. 5f. Dome networks formed in this manner grow over time and merge into a stable state with different layer number domes forming on top of each other. If domes grow in the same TMD layer, they will form one dome with larger dome R, due to energy minimisation. To confirm the layer number and domes growing on top of each other, second harmonic generation (SHG) images before and after bursting a 2 L dome in to a 1 L dome is shown in Fig. 5g, along with a side and top view schematic of the process as shown in Fig. 5h. SHG was used as only odd layer numbered non-centrosymmetric crystals exhibit SHG, which was visualised after bursting the 2 L dome. Considering the merging of domes, a variant Plateau’s law was observed for gas filled domes over long time periods due to the stable and long-lasting fabrication method of proton irradiation. Unlike soap bubbles, domes formed in the first few TMD layers exhibit discrete and varying surface tension values depending on which layer the dome manifests, which permits a variant to Plateau’s law for commonly observed bi-joint and tri-joint domes. An equivalent surface tension for gas-filled domes in the membrane regime is given by97:

Since the shared boundary can be seen as the exfoliation of a top single layer from a bilayer film, an adhesion energy model was proposed and used to calculate the equivalent Plateau’s angles. The analytical joint angles showed excellent agreement with the experimentally observed angles for bi-joint domes, as shown in Fig. 5i. A similar observation revealed a closer match to 120° for tri-joint domes as in Fig. 5j. Figures 5k and 5l show an AFM height and stiffness mapping of a typical tri-dome structure comprising of a stable merged 1 L, 2 L and 3 L dome, respectively. Clear evidence of varying stiffness in the domes demonstrate the formation of multilayer domes manifesting on top of one another.

Other transport mechanisms in 2D materials via domes appear in tiny angle twisted bilayer graphene (TBG) on WSe2 sheets106. Using scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) at 77 K, it was observed that the Moiré periodic network of corrugations in TBG plays a crucial role in governing the movement of domes. Specifically, when the domes size is comparable to the size of the AA-stacking regions within the TBG, the bubble tends to move along the domain boundaries defined by the Moiré pattern. However, when the bubble is smaller than the AA-stacking region, it becomes immobilised and fixed within that region, indicating a breakdown of the self-cleaning mechanism that is typically observed in larger domes. Such behaviour highlights the significant influence of the TBG’s structural features on the dynamics of nanoscale interfacial bubbles and suggests the importance of the Moiré pattern in determining bubble motion at different scales. AFM tips were also used to modify and engage merging domes. Transport of trapped contaminants underneath MoS2 on hBN substrates subjected to a moving AFM tip also resulted in the formation of a larger single dome, which is due to the increase in trapped contents107. Efficient transport of molecules was also demonstrated under graphene domes, demonstrating potential as a future proton exchange membrane108.

The ability to manipulate the contents inside domes and transport matter along the flake of a material may offer some engineering benefits in fabricating domes to required sizes and strain requirements. Merging two domes containing two different gases may be possible by initiating coalescence through an AFM tip, which may lead to new routes of strain engineering using domes. The ability to modify and transport matter is critical for achieving larger biaxial strain, which is beneficial for strain engineering of 2D materials.

Biaxial strain induced effects

In this section, we review the resulting strain induced modulation of carriers and material properties in domes. At the apex of a dome, both radial and circumferential strains are equal leading to maximum εtotal. However, beyond the apex, the strain components change, with the circumferential strain decreasing to zero at the edges, whilst the radial strain is still large (discussed in Section 3). As the trapped matter within domes pushes outward on the encapsulating 2D material, the two strain components generate εtotal > 10% at the apex in some cases82. Strain in 2D materials induces changes in the crystal structure and geometry, leading to favourable material properties (piezoelectricity, flexoelectricity etc.), and domes are suitable candidates as strained structures.

Bandgap engineering via strain results in either direct or indirect exciton transport. As the crystal structure of a 2D material is modified via strain, excitons exhibit different transport energies in the Brillouin zone. A sample bandgap energy diagram for varying biaxial strain conditions in a WS2 monolayer is shown in Fig. 6a9. A transition from direct to indirect exciton transport is observed at 3.2%, which highly supports domes as a prime candidate for achieving reliable strains in a stable structure at room temperature. Moreover, domes exhibit complex biaxial strain fields across the surface from the apex (largest strain) to the edge (smallest strain) without the need of external tuning mechanisms. The important bands that constitute the direct to indirect transitions is shown in Fig. 6b. Considering the strain across a domes surface as in Fig. 6c, micro-photoluminescence (micro-PL) experiments revealed the direct to indirect transition of excitons across the surface of a biaxially strained dome as shown in Fig. 6d109, which was mapped against the corresponding strain values calculated by finite element analysis (Fig. 5c). The emission spectra of the domes reveal the complex interplay between strain and bandgap behaviour along the r axis of a dome as shown in Fig. 6e. Transition behaviour was resolved for several 2D TMD domes. Figure 6f illustrates a micro-PL experiment (excitation + recombination) on a single WS2 dome, with the AFM image shown in shaded orange, wherein an exciton drifts over the dome strain distribution known as the funnel effect. The blue-red paraboloid highlights the direct-indirect transition of the dome from the spatial component (AFM image) and the exciton energy. The corresponding total in-plane strain versus the direct and indirect exciton transitions is shown in Fig. 6g, demonstrating a linear shift rate in peak energy versus the total in-plane strain. Such extensive experimental investigations for probing the nature of biaxially strained domes is possible in proton irradiated samples as the spherical dome structure exhibits large non-unform biaxial strain along with their room temperature stability and comprehensive analytical formulation of the mechanics. This general behaviour in 2D biaxial strained domes utilising 2D materials can be used for flexible optoelectronic devices along with long lived k-space indirect excitons110.

a Bandgap energy diagram of biaxially strained WS29. b Schematic of the important bands that constitute the A (CB+, VB+) and I (CB−, VBΓ) direct to indirect exciton transitions9. c Height and strain dependence along dome radius profile of a WS2 dome formed after proton irradiation109. d Micro-PL scan along the diameter of the same dome in (c) performed at 297 K109. e Normalised emission spectra of the dome as the laser spot is scanned from the dome’s left edge to its apex shown with the corresponding strain109, A refers to direct and I refers to indirect excitons. f Schematic illustration of exciton drift over the dome strain distribution via the funnelling effect transition from direct (A) to indirect excitons (I)109. g Measured shift for A and I excitons as a function of strain along a single dome109. h Contour map showing the evolution of SHG polar pattern regarding strain ratio (εh / εr) and principal strain orientation (θr/δ). P0 /(P0 + P60 + P120) represents the variation in the sizes of petals located at 0°, 60°, and 120°. Experimental SHG polar patterns are indicated by the spheres, and contour map is calculated analytically111. i Strain induced Zeeman splitting in WS2 domes (at zero magnetic field). With increasing strain, the A and I excitons hybridise with a distinct anti-crossing9. j Biaxial strain versus g factor. Different strains can be accessed in a single device due to the r strain dependence in domes. k 2D projection of a graphene dome obtained via STM with a R = 13.5 nm and hm = 1 nm74. l Three-fold symmetric pseudomagnetic field as a function of rotational angle of the dome given in (k)74. m Current - Voltage (I-V) characteristics of a monolayer MoS2 dome. Green dots are experimental data whilst the red line is a fitting function126. n Statistics of piezoelectric measurements of monolayer MoS2 domes measured via Kelvin probe force microscopy126. Figures m and n adapted from Copyright (2021) Wiley. Used with permission from (Wang. W. et al., Visualising Piezoelectricity on 2D Crystals Nanobubbles, Advanced Functional Materials).

The emission of biaxially strained domes should significantly enhance the second harmonic generation (SHG) emission compared to their flat counterparts. SHG only occurs in materials with broken inversion symmetry, meaning such crystals possess a non-vanishing second-order nonlinear susceptibility χ0(2), and in the presence of an optical pump, will give rise to SHG. SHG results in frequency doubling or parametric amplification of light waves. Odd-layer-number TMD crystals are prime candidates for applications involving SHG due to their excellent opto-mechanical properties, atomic thickness and confinement effects. Liu et al. 111 fabricated pressurised domes using proton irradiation and conducted comprehensive SHG measurements for different dome geometries and strain conditions. The slight evolution of lattice distortion induced by biaxial strain in different magnitudes and directions is clearly examined using polarisation-resolved SHG, with the corresponding anisotropic responses clearly illustrated in SHG polar plots. Interestingly, bright fringes are only observed for domes with heights exceeding 160 nm, which is linked to the biaxial strain exhibited at the apex. The diverging strain field in a dome also shows the change in SHG emission along the surface of a dome, which cannot be exhibited in flat counterparts. A contour map showing the evolution of SHG polar pattern regarding different strain orientations is shown in Fig. 6h111. When the biaxial strain approaches a uniaxial strain condition, it can lead to greater lattice distortion, as evidenced by an increased slope and amplitude of the wave. In contrast, when the biaxial strain is nearly isotropic, the polar plots exhibit a uniform sixfold symmetry, independent of the strain orientation, as reflected in the flattening of the curve. Overall, using biaxially strained domes, the SHG emission increases by 160-fold at room temperature and at least by one order of magnitude in low-temperature environments, demonstrating the vast robustness achieved in biaxially strained domes. Such inherent behaviour of strained domes yields promising potential in third-harmonic generation and four-wave mixing processes.

TMD domes offer design flexibility through engineering substrates to tune the optical emission energy. Trapped hydrocarbons on different substrates, including PtSe2, WS2, MoS2 and graphite, enable tuneable PL emission from 1.72 to 1.81 eV, which is further aided by strain112. Other optical effects exhibited in domes include optical constructive and destructive interference rings, which affect Raman oscillation modes113. ReS2/graphene heterostructure domes with trapped gas also display optical anisotropy due to large biaxial strains114. Other optical effects in strained domes can also result in enhanced responses; for instance, ultra-confined plasmonic hotspots were observed in graphene domes formed through CVD transfer trapping a mixture of air, water and hydrocarbon contaminants115. Theoretical calculations provided the reason for this ultra-confined enhancement due to the dome's significant increase in local plasmon wavelength, which results in strained domes. A highly effective surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy approach was established using a gold nanoparticle/ WS2 dome / graphene vdWs heterostructure. Each individual component of the heterostructure improved dipole-dipole interactions along with charge transfer triggering the superposition of the localised effects of individual components116. Such enhanced plasmonic features coincide with the strain from domes, demonstrating their wide use and integration for optical devices fabricated from 2D materials.

Biaxial strain in domes also leads to the formation of pseudo-magnetic gauge fields due to crossovers of the relevant conduction and valence bands in 2D atomic crystals. Magneto-PL emission experiments carried out on a WS2 dome found that the K wave vector could mediate the radiative recombination between conduction band and Γ valence band leading to Zeeman splitting of two oppositely circularly polarised components9. To describe the magnetic moment change, the term “g-factor” or the orbital angular momentum is coupled with the experimentally determined direct and indirect exciton transitions that can be observed, which is similar to other experiments conducted at cryogenic temperatures (~4.2 K)117,118,119, however, the unique probing capabilities of proton irradiated domes enable similar experimentation at RT conditions, indicating that temperature mildly affects g-factor. Coupling between excitons can be either even or odd with respect to time-reversal symmetry; the strain and magnetic field dependence of the coupled A and I excitons can be described by the upper (U) and lower (L) branches. Figures 6i, j demonstrate the strong coupling of the energy dependence between the U and L branches9, and g factors for the direct and indirect excitons versus the biaxial strain, respectively. Such strong coupling and interplay between different domains involving strain, magnetism, excitons and optical hybridisation between resonant exciton species will open new paths toward domain tuning approaches in 2D domes. Pseudomagnetic fields also form due to the strain induced in programmable graphene domes74. Figure 6k shows a 2D projection of a graphene dome with hm = 1.06 nm. Significant lattice deformation in the graphene leads to an inhomogeneous diverging strain field, which induces a PMF along the graphene dome surface. A PMF maximum of 125.7 T was observed in the graphene dome along with 6-fold symmetry behaviour as shown in Fig. 6l, which is similar to PMF observed in other graphene domes over 300 T120. The maxima of the field occur at angles approximately 60° apart, specifically at 30°, 90°, 150°, 210°, and 270°, both at the edge and the centre of the graphene dome. The field values decrease and eventually drop to zero at the intermediate angles between these maxima, such as 60° and 180°. A fitting of the experimental data resulted in a magnetic field relation of |Bs | = 121sin(3θ). Such large magnetic fields induced in domes demonstrate their capabilities as a device that exhibits large total in-plane strain due to biaxial tension along the surface. An oxygen plasma-assisted fabrication technique has also been used to observe PMF in graphene domes121, which showed longer-term stability compared to bulging devices. PMF can also naturally occur in vdWs materials, generating milli-Tesla fields122. Graphene domes are also promising for potential valley filters and beam splitters due to the induced PMF from biaxial strain across the surface of a dome. PMF leads to different real space trajectories of K and K’ electrons on the Brillouin zone, enabling individual manipulation and greater degrees of freedom in valley-dependent guiding of electrons in graphene123.

The effects of dome-induced strain on the magnetic properties of the vdWs ferromagnet CrBr3 have also been systematically investigated using Raman spectroscopy along with magneto-PL124. 6 L CrBr3 encapsulated in a few layers of graphene, low-temperature experiments reveal a nontrivial spin arrangement between unstrained and strained domes. Different magnetic hysteresis curves were observed between strained and unstrained samples, indicating that strain heavily influences the magnetic energy of the material. However, it was concluded that CrX3 crystals exhibit high sensitivity towards magnetism and slight changes can switch ferromagnetic and anti-ferromagnetic behaviour125, meaning enveloped strain in domes alters the crystal structure, influencing magnetism.

2D crystals with inherent non-centrosymmetric structures also exhibit piezoelectric properties making them ideal candidates for low-dimensional power applications and energy conversion materials. Wang et al.126 investigated the piezoelectric properties of odd-layer-numbered h-BN and MoS2 domes fabricated via mechanical exfoliation and transfer (top-down approach). Using Kelvin probe force microscopy, the piezoelectric effect could be mapped across the surface of a dome and the typical I-V characteristics and piezoelectric field of an MoS2 monolayer is shown in Fig. 6m, n, respectively. By calculating the stress in the dome and the electric field applied, the piezoelectric coefficient of h-BN and MoS2 were derived to be 3.4 ± 1.2 10-10 Cm-1 and 3.3 ± 0.2 × 10-10 Cm-1 for h-BN and MoS2, respectively, agreeing well with previous reports127,128. The piezoelectric properties were also investigated under light illumination, where photogenerated pairs of electron-holes can be separated, also demonstrating strong coupling between different physical domains, which can be attributed to the large total in-plane strain in biaxially strained domes. WS2 on a graphene substrate domes also show photogenerated electron-hole pairs due to biaxial strain in domes129. Non-uniform strain which is enhanced using biaxially strained domes facilitate piezoelectric behaviour, using a Hamiltonian expression, a closed analytical expression was formulated for the piezoelectric constant in terms of Valley-Chern number128. Domes exhibit giant piezoelectric effect and valley-Zeeman coupling, enabling piezo-induced dipole-dipole interactions leading to nonlinear exciton drift across the surface of a dome130. Exciton drift is tuneable based on the dome’s size and is linked to the piezoelectric-induced electric field, which is proportional to \(\frac{{h}_{m}^{2}}{{R}^{3}}\). Engineered electric fields are possible through the design of dome material and substrate enabling large variety of possible combinations with inherently large biaxial strain.

In addition to piezoelectricity, strain gradients induce a flexoelectric effect in materials. Whilst flexoelectric effects are normally rare to encounter in bulk materials, flexoelectricity in 2D materials can be prevalent. Flexoelectricity is a dielectric material property when coupling between a strain gradient and electrical polarisation exists, and this is enhanced as the material approaches atomic thinness and is enhanced due to the large stretching capabilities of 2D materials. Described by a fourth-order tensor, flexoelectricity generates an out-of-plane vertical polarisation. CVD-grown graphene domes with trapped contaminant residues on a SiO2/Si substrate were excited using a polarised field induced by piezo force microscopy (PFM) for determining the flexoelectric properties. Using phase-amplitude contrast imaging of different dome geometries, a d33eff constant was estimated to be ~0.13 nm/V and a quadratic dependence was observed when increasing bubble creation voltage131.

Ferroelectricity is another property that has emerged in cone structures, similar to domes. Out-of-plane ferroelectric and piezoelectric properties induced via interlayer twist or strain due to weak vdWs interactions can cause “sliding ferroelctricity” in 2D materials. Mao et al.132, transferred 2 L MoS2 onto a patterned cone substrate with approximately 60 nm height to induce localised strain in the material, which led to an interesting observation of the emergence of vertical ferroelectricity for both CVD-grown and mechanically exfoliated samples at room temperature conditions. Ferroelectricity was confirmed using AFM, PFM amplitude and phase testing. A prototype ferroelectric nanodevice in the form of a ferroelectric tunnel junction was fabricated and poled at different voltages, demonstrating potential for applications involving non-volatile and advanced electronics using vertical polarisation. A theoretical analysis also relates the observed ferroelectric behaviour with the strain inherent in the 2D crystal, further confirming the vast room temperature opportunities via domes or near equivalent 2D structures. Whilst, the device was fabricated via cones, domes should also exhibit similar behaviour for creating 2D dome ferroelectric field-effect transistors (FeFETs).

Future applications

2D domes exhibit a range of advantageous properties across optical, mechanical, and magnetic domains, and the coupling between these responses makes them attractive platforms for strain-engineered nanoscale devices. Their ability to sustain large, non-uniform biaxial strains extends their utility across diverse applications, including sensors, resonators, and optical bandgap metasurfaces, as shown in Fig. 7. In the following section, we highlight the role of domes as versatile building blocks for nanoscale devices, spanning both fundamental studies and applied technologies.

Domes integrated into metasurfaces represent an exciting frontier in materials science and photonics, offering a versatile platform for manipulating electromagnetic waves. Metasurfaces are periodically engineered 2D material structures that have properties that can control electromagnetic waves at a subwavelength scale, which can reflect or transmit plane waves133. Control over light waves can be in the form of amplitude, phase and polarisation modulation134. The use of domes in metasurfaces takes advantage of their unique geometries, vast material selection, patterned fabrication in the case of irradiation, and non-uniform biaxial strain, which can enable large design flexibility in engineering metasurfaces. Since dome geometry can be engineered and spatially separated using masks via irradiation, varying unit cells of different arrangements of domes with varying R can be fabricated. As a result, resonant frequencies and structural periodicity can be controlled to target specific wavelengths. Previously triangular, pyramidal, ellipsoid and polygonal dome footprints were realised. Patterning different footprint shapes will also enable various design opportunities. Therefore, if masks comprising of different sizes and footprint shape are used in conjunction with proton irradiation, many dome and dome offset possibilities exist. Moreover, many structures can be synthesised in a single process on top of a bulk flake, simplifying the fabrication process. Other benefits of this method include that 1 L metasurfaces can be achieved, and depending on the impinging proton source, potentially 2 L and 3 L metasurfaces may be possible.

The high refractive index of certain 2D materials used in domes further enhances the performance of metasurfaces, since domes are normally created in the first few basal planes of layered materials. Atomically thin TMDs enable strong light-matter interaction, which is of importance in metasurface design. Moreover, the direct bandgap in monolayer TMDs allows for efficient light absorption and emission, unlike conventional bulk counterparts. In the context of domes, strain depends on the radial coordinate of a dome, leading to regions of both direct and indirect band gaps, which may offer unique engineering possibilities for 2D metasurfaces based on biaxially strained domes.

Domes exhibit phenomena including piezoelectricity, flexoelectricity, PMF, sliding ferroelectricity, etc. Due to the existence of different physical phenomena observed, domes can act as unique 2D sensing probes. As discussed earlier, domes enable rapid measurements of γ, whether for material substrate adhesion or interlayer adhesion. Many different measurement tools work seamlessly with domes, and their out-of-plane formation enhances their optical detection along with the high refractive index of many 2D materials. Due to the large strain in domes, they offer an exciting avenue for a single device that can measure a wide variety of nanoscale phenomena simultaneously, at various temperatures. Domes also act as confined volumes with large internal pressures, and different states of matter can be trapped. Therefore, combining or merging different gases, contaminants, solids, and their combinations can serve as a high-pressure nano-chamber. Domes were also shown to be quite stable and robust to repeatable AFM measurements, for most fabrication techniques. Considering the long-term stability, robustness and various temperature existence (especially room temperature for proton irradiated samples), nanoscale sensors based on biaxially strained domes will serve as an important role in future sensing applications. Moreover, large quantities of domes of different geometries can be fabricated in a single process (proton irradiation), which is highly beneficial for repeat testing and investigating effects of size and strain regarding measurement sensitivity.

2D domes naturally encapsulate matter at high pressures within nanoconfined volumes, making them promising candidates for nanoscale storage and controlled release of solids, liquids, or gases. Such encapsulation could be harnessed for on-demand reactions, for example, by employing laser irradiation to rupture domes and trigger localised release. In the case of gas-filled domes, spatial control over size and distribution can be achieved through irradiation, masking, or other fabrication techniques, thereby enabling tunable volumes, pressures, and molecular content. With precise control of actuation stimuli, biaxially strained domes may offer opportunities in biomedical applications. Furthermore, the stability of domes at room and elevated temperatures provides distinct advantages for applications operating under ambient or fluctuating thermal conditions.

Domes can serve as a crucial platform for room-temperature mechanical resonating devices. Due to the large selection of available 2D materials from which domes can be formed, various combinations of material properties can be selected depending on need. For example, the figure of merit (resonance frequency multiplied by the quality factor) of an MoS2 resonator is larger than graphene, which is due to phonon-phonon scattering135. Phonons, the quantised vibrational modes of a lattice, play a central role in governing energy transfer and dissipation in resonant devices. The relatively low dissipation of MoS₂ provides a distinct advantage for resonator applications. Material choice is also critical for enhancing both sensing and actuation in dome resonators. Many transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) exhibit piezoelectricity in few-layer form, which can be exploited to amplify electrical sensing signals. Conversely, the same piezoelectric response offers a potential route for actuating dome structures, thereby integrating both transduction and actuation within a single material platform.

Strain engineering in resonators also serves as a promising platform for enhancing the quality factor (Q) which describes the ratio of the peak energy stored versus the energy lost per oscillation cycle. Strain engineering offers a material-independent route toward increasing the Q factor of resonators136,137. Since domes exhibit large biaxial strain across their surface, the Q factor may increase. Tensile-strained devices also exhibit larger resonance frequencies compared to their unstrained state, which will also aid in generating higher frequency resonators with larger Q compared to their flat counterparts; however, the effect of the pressurized confined matter also needs to be considered for its effect on the mechanical compliance of a dome resonator. Proton-irradiated domes produce room-temperature stable devices without the need for external tuning mechanisms. To further increase the strain exhibited by domes, complex strain field may be generated by encompassing a variety of different strain engineering techniques, which may aid increasing low Q factors at room temperature.

Domes in monolayer TMDs provide an effective route for generating quantum emitters. The large biaxial strain inherent to the dome structure creates localised potential wells that confine excitons, thereby giving rise to single-photon emission. This strain-engineering approach enables the controlled formation of stable and long-lived quantum emitters without introducing structural damage to the TMD lattice. In particular, WSe₂ dome quantum emitters exhibit significantly stronger oscillator strengths, which are enhanced by strain-induced quantum confinement138. When MoS2 monolayer is deposited on a hBN substrate, naturally occurring domes form, resulting in a local reduction of the band gap due to the strain induced by the domes. Using numerical simulations, strain-confined photogenerated pairs form a potential well leading to confined exciton states. Findings indicate that a single confined exciton state is optically active, suggesting that MoS2/hBN nanobubbles are promising candidates for single-photon source applications139. Multilayer hBN with intentional confinement of other materials within domes fabricated using various vdWs materials may induce local luminescence at different frequency ranges due to a combination of strain and mechanical deformation98. The unique optical properties of graphene domes facilitate strong nonlinear light–matter interactions, resulting in an optical bistability effect at cavity resonance. The distinctive optical response of graphene domes enables strong nonlinear light–matter interactions, giving rise to optical bistability at cavity resonance. Unlike planar graphene, dome geometries introduce vertical sidewalls that extend the interaction path for nonlinear dispersion, producing a π phase shift and an effective λ/2 modification of the optical path length140, which may open up pathways to optical logic memory and optical signal processing.