Abstract

Single atom catalysts (SACs) are frontier composites maximizing the active phase activity, but require stabilization. This study conducted a high-throughput analysis of 54 pristine MXenes as supports for the 30 3d, 4d, and 5d transition metals (TMs), exploring 1620 cases. First-principles calculations on MXene models showed patterns in the adsorption energies, Eads, of the TM single-atom (SA), revealing high Eads, except for d5 or d10 TM electronic configurations. The SA diffusion barriers, Eb, revealed easy diffusions, although in some cases high Eb inhibited aggregation or dispersion. Random forest regressor (RFR) machine learning predicted Eads with a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.25 eV, and a regression coefficient of 0.99, showing that the TM cohesive energy is key in Eads prediction. Here, the RFR model reported a MAE of 0.1 eV, with few MXene and SA properties being important. Our findings provide insights to use MXenes as support for SACs or TM clusters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides, known as MXenes, are emerging few-layered materials since the first isolation of Ti3C2Tx MXene1. Since then, MXenes have been the focus of many and diverse research, from technological fields such as water purification2, to energy storage3 and catalysis4, to name a few. MXenes were initially isolated by Naguib and colleagues1 through the selective chemical etching of A phase from MAX phase precursors5. These MAX phases, with general Mn+1AXn formula (n = 1–3), are a vast class of materials given their chemical diversity, featuring early d-transition metals (M), main group p-elements (A), and carbon and/or nitrogen (X)6, with diverse surface terminations such as Tx = –F, –OH, –H, and –O, specially present when using hydrofluoric acid (HF) as etching agent, even though other terminations can be gained using molten salts, like Tx = –S, –Cl, –Se, –Br, –Te, and –NH7. In addition, the thickness n can be a tuning factor, as well as the layer stacking8,9. The diversity of such components is the perfect sandbox for designing MXenes towards a broad spectrum of potential applications, including energy storage, catalysis, or batteries10,11,12.

Concerning single atom catalysts (SACs), one may wonder whether such MXenes would be suited substrates to hold such single atoms upon. Ideally, a proper SAC substrate would tightly bound the atom, avoiding the single atom clustering process, either thermodynamically; when the bond to the MXene would be stronger than the single atom element cohesive energy, or kinetically; with prohibitive single atom diffusion energy barriers13,14,15. When one of these (or both) are met, SAC/MXene compounds can become viable, plus, in principle, potentially susceptible of being employed as thermo- or electrocatalysts. Hence, recent studies showed e.g. that single Pt atoms covalently immobilized on double transition-metal MXene nanosheets —such as Mo2TiC2Tx— with Mo vacancies on the outer layers featured a key electrocatalytic activity towards the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER)16. Similarly, density functional theory (DFT) based calculations highlighted the efficacy of single Mo atoms anchored on Ti3C2 MXene for the electrochemical nitrogen reduction reaction (NRR) of N2 to NH3, exhibiting a low overpotential while facilitating a rapid NH3 desorption17. Aside, defect-containing SAC/Mo2Ti2NO2 layers —composed of Zr, Mo, Hf, Ta, W, Re, or Os single-atoms—were also highlighted for the NRR18. In a similar way, Zn/V2CO2 MXenes have been proposed as candidates for CO oxidation19, and in Cu/Mo2CTₓ MXene Cu single atoms were found to significantly enhance the CO2 hydrogenation to methanol by tuning the electronic structure and stabilizing key reaction intermediates20.

Given the large ocean of possible MXene materials that could exist when accounting different composition, layer order, stacking, width, and termination groups9, machine learning (ML) models trained on a sufficiently large set of quantum-mechanical calculations have emerged as an appealing alternative for a high-throughput, fast, yet reliable assessment of the MXene materials suitability towards given, desired applications. This is especially attractive when gaining predictions of the chemical stability, activity, or reactivity, approached utilizing either algorithm-derived features or elaborated ones21,22,23. In such ML models, the input atomic features are often accessible from the species the compound is made of, although others may require being estimated based e.g. on DFT optimizations24. So far, ML models have been employed to reach estimates of the adsorption energies of molecules or atoms on diverse substrates within the DFT inherent accuracy in a remarkably rapid fashion24,25,26, while e.g. reactivity steps or diffusion energy barriers still require further refinement25, plus normally the optimization target is frequently a single property; such as the d-band center27, the selectivity28, a limiting overpotential29, or a leveled bandgap30. Regardless of the case, supervised ML algorithms are at the frontier of the rational intensive mapping of large target data sets31.

The present work aims to provide a theoretical assessment of the SAC stability on MXene materials, by exploring, through ML means based on DFT estimates, the structural, bonding, energetic, and diffusive properties of 3d, 4d, and 5d transition metals (TMs) anchored on the basal, most stable (0001) MXene surface with Mn+1Xn stoichiometry (M = Ti, V, Cr, Zr, Nb, Mo, Hf, Ta, and W; X = C or N, and n = 1-3), encompassing a total of 54 different substrate MXene materials, 30 TMs, and, thus, 1620 distinct systems. Note in passing by that pristine MXenes, achievable by selective etching or special cleaning protocols7,32, have been pointed out as key for an optimal catalytic performance33, and pristine patches also found to be key in stabilizing SACs on them20. The study underscores the most important physicochemical features determining the TM adsorption strength and diffusion energy barriers, providing a solid model for future estimates, plus a meaningful rationale of the key aspects to be considered, which can be used as a compass for future computational or experimental works towards the synthesis, characterization, and catalytic test of SACs on MXenes.

Results

Density functional theory calculations

Shall we start this section by discussing the interaction strength of the 30 TMs on the 54 MXenes with different compositions, beginning with the first row 3d TMs atoms (TM = Sc, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, and Zn) supported over nine bare M2C MXenes (0001) surfaces (M = Ti, V, Cr, Zr, Nb, Mo, Hf, Ta, and W), see Fig. 1 and results in Table S2 of the Supporting Information (SI), as previously studied15. From the competitive adsorption on T, B, Hfcc, and Hhcp sites, the last two were found to be preferential ones regardless of both the SAs and the MXene substrate, with more than 90% of all studied cases in either of the two positions. Of the two, Hfcc seem to be the preferable site with the majority of the found minima, although the difference between the calculated adsorption energies in both H sites shows that they are in most cases quite competitive, with just few cases surpassing a difference of 0.2 eV, as found e.g. in Sc and Cu.

Green spheres represent the M atoms, while lavender spheres denote X (C or N) atoms. Labels T, B, Hfcc, and Hhcp denote top, bridge, hollow with a M atom underneath, and hollow with an X atom underneath, respectively. Different shades of green are used to better distinguish between the sampled metal layer and those underneath.

A comparison of the calculated DFT adsorption Eads with those found in a previous study15 is found in a parity plot shown in Fig. 2. From the 90 cases, the majority show very similar values, reflected in an R of 0.96, with a MAE of 0.22 eV, yet there is a systematic error when comparing V SAs in the nine MXene surfaces, with a mean difference in energy of 0.9 eV compared to what is found in literature15. After some careful evaluation, this difference seems to arise from the spin polarization and the found magnetic solution. When a non-magnetic solution is forced or found, as in the previous study15, the R and MAE increases to 0.98 and decreases to 0.16 eV, respectively. Still, though, the present ferromagnetic solutions are lower in energy, and used in the following analysis. Another source of difference is the employment of ZPE, which in average lowers the present Eads by 0.10 eV, and that partially explains the intersect at -0.34 eV. An outlier is Mn/Zr2C, with larger Eads compared to the literature. The difference arises due to only one minimum being reported in the literature, with an Eads of -1.9 eV as found here on Hfcc site. However, another lower minimum is also found on the Hhcp site, with an Eads of -3.1 eV, not found before. Still, apart from these differences, the gained trends are generally in line with those present in the literature15.

Parity plot between the present DFT Eads results and those in ref. 15. The linear regression \({E}_{{ads}}^{{DFT}}=0.90{E}_{{ads}}^{{Ref}}-0.34{\rm{eV}}\) is shown as a red line, while dashed black line would indicate the perfect parity plot.

As far as diffusion Eb are concerned —see Table S2 of the SI— the previous study did not carry out an exhaustive analysis, and only a handful of adatoms and MXenes were inspected; mostly for Zn and Sc SAs. Within this regard, the present values are extremely similar. For instance, the same Eb value of 0.09 eV is obtained for Zn/Ti2C, while for Sc/Cr2C the present Eb value is 0.34 eV, only 0.01 eV smaller than in the literature15. Thus, within this narrow comparison, the coincidence is remarkable. Finally, the trend along the 3d series is also observed here, with an inverse double hump feature (see example on Ti2C MXene in Fig. 3); where Eads strength weakens when moving along the period until d5 elements like Mn, to became again stronger, and weakening back until Zn d10 element15, a feature inherently linked with the TM atom stability in vacuum34, where partially or fully filled d orbitals in d5 and d10 electronic configurations have a special stability which makes them to interact with the substrate in a weaker fashion.

This trend is generally mirrored for all the 3d TM series regardless of X nor n MXene variables, i.e. irrespective of being carbide or nitride based, nor the MXene width (cf. Figure 4). Thus, the key for such 3d TMs to strengthen their adsorption is to have more unoccupied or singly-occupied d orbitals, without reaching the half- or full-filling of d orbitals plateaus of stability. Such a trend is kept for 4d and 5d TMS, but less clear. Actually, the weakest situation is given special on 4d4 and 5d4 elements, Mo and W, respectively. Indeed, upon adsorption Mo and W consistently gain electrons, with mean Q of –0.42 and –0.47 e , respectively, and so getting closer to the d5 half-filled configuration. This behavior is mirrored by Tc and Re, gaining 0.71 and 0.73 e , respectively, and so moving away from the d5 configuration. Affinity with the surface increases for d5 and d6 metals, up to the high affinity for TMs shown by d7 configuration (Rh, Ir), from which then on the Eads weakens to the d10 configuration bottom. Actually, Rh and Ir are among the SAs that consistently always present negative Q, thus gaining electrons, with values above –0.85 and –1.05 e , respectively, which could indicate the stronger adsorption. The general trends observed for M2C systems are replicated in M2N counterparts (see Fig. 4), even if the Eads of M2N MXenes are larger —by 0.50 eV to 1.0 eV— than their M2C counterparts. Clear examples of this statement are Ta2N and W2N MXenes.

Having analyzed trends along d series and depending on X composition, it is worth underscoring how 4d and 5d TMs have larger adsorption energies than the 3d counterparts. This is particularly appealing since some Pt-group TMs feature large Eads, like Ru and Rh, with the exception perhaps of Pd and some Cr-based MXenes. This trend is also observed for N-based MXenes, and, if any, more visible for 5d TMs, where Re, Os, Ir, and Pt Pt-group metals display large Eads values, which leaves open the question of whether such MXenes would be suited materials to host Pt SACs.

Finally, the MXene thickness is put under evaluation; this is, for example, on how Eads varies based on the MXene n (i.e., M2C, M3C2, and M4C3). C-based MXenes, increasing width tends to have a slight impact on adsorption strength, as observed in the past for magnetic properties or the adsorption of CO235,36. There are only few exceptions depending on the MXene M group; for group VI MXenes (V, Nb, Ta), and particularly for group XII TMs (Zn, Cd, Hg), a slight but nonetheless existent decrease in adsorption energies appears, but the dropping along the group is found to be at most of 0.40 eV (see Table S2 of the SI).

Another systematic decrease in Eads as when n increases for 3d TMs on Crn+1Cn MXenes, with drops by 0.2–0.5 eV. For example, the Eads of Fe and Co may decrease from ca. -5.5 to around -5.0 eV when going from Cr2C and Cr4C3, respectively, clearly seen when comparing Fig. 4 with Figures S1 and S2 of the SI. A small number of C-based MXenes (e.g. Hf2C to Hf4C3 with Fe, Mo2C to Mo4C3 with Ir, or V2C to V4C3 with Mo) also show a decrease in Eads, but not as drastic as the just commented Cr-based, reaching a maximum of 0.2 eV, while most cases show nearly identical Eads, with differences in the meV range. In contrast, N-based MXenes experience larger oscillations in the adsorption strength while increasing the width, for specific cases. For instance, SAs like Mo and Ir can have Eads close to -7.0 eV in both M2N and M4N3. When one pays attention to Nb- and N-based MXenes, and when moving from Nb2N to Nb3N2, the overall adsorption strength diminishes, later regained when increasing the width to Nb4N3. These changes are, however, not larger than 0.5 eV, so the overall significant bonding strength prevails36. Last but not least, since one is focusing on MXenes capable of sustaining SACs, two M4N3 MXenes particularly exhibit large adsorption strengths for many SAs, namely Ta4N3 and Cr4N3.

All in all, the above analysis shows how complex the adsorption on TMs SAs on MXenes can be, with different factors influencing the interaction strength, including i) the MXene TM, ii) the MXene X, iii) the width, n, iv) the d series of the SAC, v) the SAC TM electronic configuration, and vi) charge transfers between SA and the MXene. As far as some factors are concerned, a rationale can be withdrawn. For instance, N-based MXenes larger Eads adsorption strength, observed as well on molecular interactions37, may be due to a better overlap of the atomic orbitals when N is present38, being the electron density more diffuse. In the case of n, even if not being a key factor, can be linked to a more similar electronic structure of n = 1 and 336.

Actually, the electronic charge transfer between SA and the MXene substrate can be a determining factor. To further inspect this issue, a Bader charge analysis has been performed to see the effect of the MXene surface on the SA electron density39,40, plus its correlation with the adsorption energies, see Figure S3 of the SI, where, by definition, a positive value of charge means the loss of electrons of the SA (thus being positively charged), whereas a negative value implies a SA gain of electrons, and therefore, becoming negatively charged. In this latter case, an overall loss trend is found, in that the larger the absolute charge of the SA, |Q | , the stronger the Eads, although the trend is by no means linear, with an R of 0.44, and must be regarded as a general tendency. Actually, just qualitatively, one can see how the Eads is moderate when there is no charge transfer, and larger when the SA becomes a net acceptor or donor of electron density, following a volcano shape, see Figure S3 of the SI. Other than that, there is almost a 1:1 split on the tendency of SAs to either attract or donate charge. There is a clear tendency; while ∼60% of d1 to d5 metals show a tendency to have a negative charge, more than 75% of d6 to d10 TMs show a tendency to have a positive charge, still quite biased by the MXene support.

Late TMs actually tend to gain electron density, while early TMs, such as Sc, tend to lose it. Such trends are likely linked to the position on the Periodic Table, since middle elements have an ambivalent nature; they can gain or lose electrons, much dependent on the MXene substrate. Still, the main feature governing the electron donor/acceptor character of the TM SA is the number of d electrons, making extreme cases of the d series clearly donors (early TMs) or acceptors (late TMs) independent of the MXene substrate. Besides, the X component does not seem to have a big influence in the charge transfer, as derived from the parity plot between C- and N-based MXenes in Figure S4 of the SI, with only few outliers, like Re on Mo3C2 and Re on Mo3N2, with very different Q of 0.25 and -1.33 e, respectively, Mo on Zr4X3 MXenes, with Mo attracting 0.83 e when X = C, but -0.59 e when X = N, or Fe on Ta3X2 MXenes, with a difference of 0.69 e of charge between the carbide and the nitride. Still, the parity plot shows a slope near the unity, with a value of 1.03, and a very small intersect of -0.07 e.

Having analyzed the interaction of the SAs on the MXenes, the focus is now put on their clustering feasibility by estimating Ediff as in Eq. 3, vide supra, shown in Fig. 5, and values listed in Table S2 of the SI. From the 1,620 examined SA/MXene combinations examined, ∼68% exhibit negative values, indicating that the isolated configuration is thermodynamically more favorable. This trend bolds the potential of MXenes as stabilizing supports for SACs in the extensive use of the wording, a thermodynamic aspect key for avoiding the agglomeration of active sites and the SAC utilization. The SA TM element plays a pivotal role in determining the stability of the isolated configuration. For instance, groups III, IX, and X TMs tend to have negative Ediff values (cf. Figure 5 and Table S2 of the SI), although this is more evident for group III TMs (Sc, Y, La) on groups V and VI MXenes (V2X, Nb2X, Ta2X, Cr2X, Mo2X, and W2X) with no great distinction by X being N nor C. Clearly having a negative Ediff is the interplay of a strong Eads vs. a small Ecoh.

Other observable trends are that, generally, 3d TM SAs tend to feature small, yet negative Ediff values, especially for group III TMs, but also groups IX-XII. When going down to 4d and 5d series, the most relevant behavior change is that, particularly for Pt-group TMs Rh, Pd, Ir, and Pt, the SAC stability is quite clear; and to a lesser extent, are other metals used as active phases in catalysis, such as Co, Ni, Cu and even Ag and Au. For instance, Au exhibits a preference for dispersion on Cr2C —Ediff = –0.19 eV—, Nb2C —Ediff = –0.55 eV—, and Ta2C —Ediff = –0.71 eV—, reflecting its thermodynamic preference to stay as atomically dispersed atoms on such suitable supports. More acute are Pt-group cases, like Pt SA on the Ti-based MXenes surfaces, with Ediff values of ca. –1.5 eV, revealing an even stronger isolated adsorption preference. With this information at hand, MXenes pose themselves as one of the materials family with most potential in hosting SACs, especially those sought in catalysis.

Having a look to situations where clustering is favored, this happens mostly on groups IV, V, and VI TMs, specially Ti, Zr, Hf, V, Nb, Ta, Cr, Mo, and W, but also for Re. Indeed, W has the highest clustering index, with 96% of cases with positive Ediff, with values ranging from 0.20 to 0.30 eV on surfaces such as Mo2C and Ta2C. Examining the MXene supports, group IV MXenes (Ti-, Zr-, and Hf-based) show the highest preference for clustering, which would point for having clusters or nanoparticles on them. Nitrogen-based MXenes show a tendency to isolate better SAs, in line with their increased Eads, with the exception of Cr2N, Cr3N2, and Cr4N3 MXenes, that show a more pronounced trend towards clustering. As far as n is concerned, it follows the Eads trends, and so M3X2 and M4X3 show similar behavior, see Figures S5 and S6 of the SI, although is worth noting how Nb4N3 and Ta4N3 are especially suited MXenes to host SA, see Figure S6 of the SI. In any case, the understanding of Ediff allows for the strategic selection of MXene-metal combinations, so as to foster single-atom catalysts, or, at variance, supported cluster or nanoparticle phases. Still, the thermodynamic stability or preference is complemented with diffusion energy barriers, Eb, shown in Fig. 6. There, high Eb would prevent atomic diffusion, thus hindering clustering; making the SA situation stable by kinetic constraints.

At first glimpse, the Eb values are generally small, below 0.4 eV, for 77% of cases and especially small for early and late TMs, regardless of being C- nor N-based. Still, the TMs in the middle of the series tend to exhibit larger Eb, and, in some cases, the increase is gradual along the d-series, reaching a maximum in d5, and then dropping from there on; specially clear on 3d series with Mn; as a collateral crossing out the concept of, the stronger the bonding, the larger the Eb.

MXene width is also a factor to consider for the study of SAC Eb. The n = 1 MXenes have slightly lower diffusion energy barriers compared to n = 2 and 3, although the difference is negligible in most cases, see Figures S7 and S8 of the SI. This fact could suggest that an increased MXene thickness can lead to a stronger SA kinetic confinement, reducing atomic mobility, key in particular examples. For instance, Ni on Hf2C has a low diffusion energy barrier of 0.11 eV, while, in contrast, Ni on Hf3C2 shows a significantly higher Eb of 0.68 eV, suggesting a stronger kinetic single atom immobilization.

Note that, as seen in Fig. 6, but also in Figs. S7 and S8 of the SI, the energy barriers seem to be more case-specific, and so, it is not rare that trends along the d series, TM groups, and MXenes, get outliers. In some cases it is due to a change of the diffusion path. In fact, even if the more often found case is following the Hfcc → BTS→Hhcp → BTS→Hfcc path, where the bridge, B, in between Hfcc and Hhcp hollows is the TS, BTS, in some cases the preferred path is Hfcc → TTS→Hfcc, where is the top site, T, the TS, TTS. This change of path can generate trend anomalies, like in Ti/Mo3C2. Another key aspect is that by diffusing, the SA may require the change of its magnetic moment, especially when going through other minima; like when jumping from Hfcc to Hhcp, and then back to Hfcc. In such cases, keeping the initial state electron occupancy at the TS may lead to high energy barriers, likes 1.41 eV for Mn on Ta2N, see Fig. 7. However, when the TS is kept at the middle state, the Eb drops to 0.32 eV. In such cases, thus, the diffusion is allowed linked to a magnetization change, that, when induced by thermalization, can happen in the ps to ms timescale41. This also goes in line with previous studies showing that even reactive steps on magnetic systems may undergo through various spin states42.

To conclude the analysis, it is worth comparing Ediff with Eb values, see Table S2 of the SI; particularly paying attention to cases where Ediff is positive, while Eb has significantly large values, ca. 0.4 eV, which would imply diffusion rate constants of the order of 106 s-1 —assuming Arrhenius behavior at 300 K with a preexponential factor of 1013 s-1—. By doing so, 72 cases were found that, even in thermodynamically driven to cluster, could well be kinetically prevented to do so. A clear example of that would be Mn on Cr2N, with an Ediff of 0.19 eV, thus going for a SA clustering, but with a significant Eb of 0.49 eV, thus kinetically preventing it. On the other side of the mirror, there are cases with negative Ediff, and so, prompt to be dispersed in SAs, that feature as well relatively high Eb values. In such situations, if there would be a supported TM cluster, it would be thermodynamically driven to disperse, but the adatom diffusion would be inhibited, thus kinetically maintaining the cluster integrity, as opposed to the TM supported SA, where the high Eb and negative Ediff would indeed favor isolation. There are 167 of the former cases, and an exemplary one would be e.g. Ti on Cr2C, see Table S2 of the SI, with an Ediff of -1.08 eV, thus clearly favoring atomic dispersion, but with a high Eb value of 0.69 eV.

Machine learning analysis

Having analyzed the Eads and Eb values on 1,620 different and diverse cases, and detecting how such quantities depend on subtle factors that may play a key role, it is now worth analyzing and predicting them through ML tools, allowing for a fast assessment of such properties, e.g. by analyzing MXenes out of the present assessment, e.g. with n = 4 or group III MXenes43,44. To lower the computational load, the initial set of features for the ML tools was chosen to be all tabulated properties, thus avoiding any DFT estimate. Examples of such features are compositional tags, atomic weights (AW) and e.g. empirical radii (re), or TM bulks cohesive energies, Ecoh, to name a few. The complete dataset is given in Table S1 of the SI, all taken from publicly available sources45. Further complex features were added later, such as exfoliation energy of the MAX phase or the d-band center, which were taken from the literature22,46.

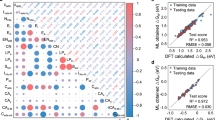

A Pearson correlation matrix was conducted to investigate potential relationships between those features that are numerical (i.e. not string-based), particularly to avoid overfitting, see Fig. 8, and also putting apart X related features, as there are only two values for them (C or N). Aside, at the start of the matrix the target features, Eads and Eb, are displayed, so as to have a first insight on which features could be more important in the ML process. Thus, Fig. 8 shows that Eads is quite inversely dependent from Ecoh, with an R of -0.87, so that TMs with smaller Ecoh have larger Eads, and this shows as well on the dependency of the TM melting temperature, Tm, and boiling temperature, Tb, related to Ecoh. Other key descriptors seem to be the TM calculated radius, rc, and electron affinity (EA), in that smaller metals with an affinity to welcome electron density would display stronger bonds. Eads also presents a correlation of –0.32 with Eb, demonstrating some relationship in that the stronger the Eads, the higher the Eb. Apart, Eb shows moderate correlation with a number of features, specially of 0.30 and 0.34 to TM Ecoh and Tm, respectively. Other than that, there is generally no large dependency among features, with R values being generally below 0.5, and values that are larger are kept under surveillance, especially in the descriptor dimensionality reduction process, see below, to avoid redundancies.

After assessing the non-co-dependency of the employed features, an initial screening with the above commented twelve different ML algorithms (including LR) was carried out, using their default hyperparameters47, and the average MAE and R results of the 30-fold cross-validation are shown in Table 1. Overall, as also often observed in the past22,25,48, the most consistent and accurate regressor is RFR, although closely followed by GBR, with MAE values of 0.21 and 0.22 eV, respectively, for Eads, and R values of 0.99. Actually, the accomplishment of both is notable, since their MAE approaches the DFT standard error of ∼0.20 eV when changing the exchange-correlation functional within the same Jacob’s Ladder level49, even when comparing to adsorptive experimental values50. Apart from that, RFR and GBR are also best performing in targeting Eb, with MAE values of 0.07 eV, and R values of 0.72. Note that actually, even if Eb MAE is quite reduced, it is affected by the aforementioned outliers; and when one actually takes into consideration Eb below 0.4 eV, the MAE drop to 0.05 eV for both RFR and GBR, and R increases to 0.73.

From that analysis, the RFR ML model was used for further improvement as seems to be the optimal choice. The RFR hyperparameters were optimized; essentially the maximum number of estimators (trees) of the algorithm, balancing robustness and speediness of the search, and the maximum number of features by split, with optimal hyperparameters of 70 trees and no maximum number of features in the split. With this, predictions for Eads from RFR are depicted in the parity plot depicted in Fig. 9, revealing a very good agreement, with just few N-based MXenes outliers, and no influence of 3d, 4d, or 5d supported TMs. Other than that, the RFR allows determining which descriptors are more influential. In the case of Eads, this is the Ecoh, as already forecasted by the Pearson matrix in Fig. 8. Still, we proceeded with further refinement, reducing the descriptors dimensionality without sacrificing the ML accuracy. This has been done in implies a recursive way, by eliminating features without impact on the predictions, followed by those with negligible impact, until examining the accuracy when removing certain features with little impact. This was based on the analysis of the importance of each of the features using the feature importance metric of the regressor. This led to five features being the most determining one, in particular the X composition, n, SA Ecoh, the SA number of d electrons, nd, and the MXene metal radius, rc, with importance values of 0.02, 0.01, 0.81, 0.10, and 0.06, respectively, with no dependencies between them (cf. Figure 8).

Based on solely these five features, the training set obtained an accuracy of 0.09 eV, meanwhile the test accuracy was slightly decreased to 0.25 eV. Note that, from a certain point on in the training data set, the data error lowers significantly, with very little deviations, and a slow yet constant decay of the MAE with the training set size. This happens here from ca. 600 cases on, and, if not reaching this point, the training error would have been of 0.12 eV with a test error of 0.32 eV (cf. Figure 10). Certainly, a significant number of data is needed to get accurate results, and actually if one extrapolates the data using the slight slope shown in the last 100 points of the training set in Fig. 10, the ML model test set would reach accuracies below 0.2 eV, when having ca. 2,000 different points.

Coming back to the key features, it is clear that the most important factor is the SA TM, with a dependence on Ecoh of 0.81, and on the SA TM nd. Indeed, the MXene substrate influence is lower, and depending essentially on X, n, and the metal rc. As above stated, the Ecoh is most determining, with larger Ecoh implying a more stable bulk, and concomitantly, a more active isolated TM SA, leading to a larger Eads. X, n, and rc do not seem to have a large importance, but necessary as they differentiate the different MXenes. In the case of rc, it seems that the smaller metal atoms facilitate a stronger local orbital overlap with the adsorbates, ultimately enhancing the Eads. Conversely, larger metal atoms may result in weaker interactions due to reduced orbital overlap13 The rc importance is greater than the combination of both n and X; and likely to be the main cause of different activity when changing the MXene.

Diffusion energy barriers were also modeled by ML RFR, following the same procedure used in Eads. Here the MAE is achieved at 0.07 eV, see Table 1, yet this smaller error has to be taken with a grain of salt, since the majority of Eb values are below 0.4 eV. Actually, the dispersion of values within the ML model is significant as seen in the parity plot (cf. Figure 11). We assumed that the dispersion is somewhat linked to the lack of a determining descriptor as it was Ecoh for Eads. Notice that the parity plot is impoverished because of the outliers with high Eb, even when there is only 239 cases of such.

By eliminating features, five key descriptors were found: the Eexf, ϕ, εd, the SAC Z, and the SAC rc, with little to negligible co-dependence among them (cf. Figure 8), and with prediction weights of 0.12, 0.16, 0.15, 0.30, and 0.27, respectively. There is a rationale behind the appearance of such descriptors. On one hand, the larger exfoliation energy of a given MXene from a MAX phase implies the MXene sheet being less stable, and so more active46, and the stronger bonding is linked to a more difficult diffusion, see Fig. 8. A larger ϕ may be an indicator of more difficulties of the MXene to transfer electron density to the SA, making the attachment more difficult or weaker, and concomitantly easing the diffusion. The εd, as in Eads, when higher in energy, implies a stronger attachment, and a concomitant smaller diffusion energy barrier51, while SA Z and rc define the attached SA.

Based on these five features, the training set received an accuracy of 0.03 eV and the testing set of 0.08 eV, with a smooth decay of both sets when increasing the training set size, see Fig. 12; with MAE converging rapidly up to 200 cases of training, to values of 0.03 and 0.09, respectively, and then featuring a smooth decay. Still, when removing the 239 outliers with high Eb —and so considering 85% of the data, 1,381 cases—, the model would better fit, with an R of 0.73, and a MAE of 0.05 eV.

Finally, having developed the ML tools, it is worth assessing their usefulness in making predictions. To this end, a set of MXenes out of the explored cases used in the training has been chosen, this is, MXenes with n = 4, i.e. M5X4, which have been recently isolated44. For this new set, we ML predicted 540 Eads, and 12 random cases were explicitly DFT calculated to deliver the parity plot shown in Fig. 13, showing an excellent correlation with an R of 0.994 and a useful MAE of 0.17 eV, which underscores the utility of the present ML model in accurately predicting e.g. Eads.

Discussion

The present study shows a high-throughput, thorough, and comprehensive analysis of MXenes as promising supports for 3d, 4d, and 5d TM SACs, providing detailed and valuable insights into the SA stability, adsorption strength, and dispersion vs. clustering tendencies, analyzing as well the main factors governing the adsorption strength and the diffusion of such SAs. The results reveal clear trends across the d series, where Eads minima are found for TM situations with half or fully-filled d orbitals. Aside, adsorption energies strengthen when going down to 4d and 5d TMs, particularly for Pt-group metals. N-based MXenes are shown to display slightly larger Eads compared to C-based ones, and a similarity for widths n = 1 and 3 is found. The comparison of Eads vs. the TM bulk Ecoh reveal that a preference towards SAs is clear for group III TMs, as well as for some Pt-group metals, with the concomitant interest in catalysis, since MXenes tend to be good supports to keep such SAs isolated.

The SACs stability is further examined by SA diffusion energy barriers, where, generally, such barriers are relatively low, below 0.4 eV, even if being key in hundreds of cases, either where TMs would tend to aggregate, but that they would be kinetically prevented for so given moderate or large Eb values, or conversely, with a tendency to become dispersed, but kinetically inhibited for. The collection of data over 1,620 different TM/MXene cases offers a clear compass to determine whether a given system would be suitable for having dispersed SAs or supported TM clusters.

Furthermore, given the large amount of diverse data, a RFR ML model was built in after testing other eleven ML type models, with hyperparameters refined. The RFR model for Eads is rather good with an R of 0.99 and a MAE of 0.21 eV, which slightly increases to 0.25 eV with a reduced dimensionality of descriptors, revealing that the most determining descriptor is the TM SA Ecoh, and with subtle influences of TM nd, and being X, n, and MXene metal rc the variables that best define the MXene support. In the case of Eb values, the ML RFR model is poorer, given the higher dispersion of values and trend outliers. Here, the R is of 0.73, and after reducing the descriptors to five variables, the MAE is of 0.03 eV, yet for 85% of the cases having Eb below 0.4 eV. For Eb the descriptors weights are more balanced, with Eexf, ϕ, and εd being key for the MXene substrate, and Z and rc the ones for the TM SA.

All in all, the present RFR tools are robust predictive models, reaching an inherent accuracy comparable to the DFT data. This predictive capability would enable the rapid screening of different TM/MXene combinations out of the sampled data, accelerating the selection process for stable SACs or viable supported clusters, offering valuable guidance for both theoreticians and experimentalists focusing on composites with the highest likelihood of success. Furthermore, the present ML tools can generally be adapted and applied to investigate SACs on other substrates such as bulk oxides, sulphides, carbides, or nitrides.

Methods

Computational Details

The atomic structure of pristine (0001) basal surface of the explored Mn+1Xn MXenes with ABC stacking was gained from a procedure firstly optimizing the corresponding MAX bulk phases, available in the literature46. The MXenes (cf. Figure 1) were constructed using p(3×3) supercell periodic models, isolated from periodic replicas in the direction normal to the basal plane by adding a vacuum space of 10 Å, enough to grant negligible interaction between replicated systems. The p(3×3) supercell dimensions are large enough to avoid lateral interactions between single atoms of adjacent cells, with a separation ca. 10 Å. The interaction of the single atoms (SAs) with MXene surfaces required exploring four high-symmetry adsorption sites over the (0001) MXene surface, including top (T), bridge (B), and two types of three-fold hollow (H) sites; one with a metal atom lying underneath (fcc), and another with a X atom lying underneath (hcp), see Fig. 1. This exploration resulted in studying circa 6,500 different adsorption configurations, yielding 1,620 adsorption minima after relaxations.

The DFT calculations were carried out using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)52, within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) framework by employing the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional53, including dispersive forces through Grimme’s D3 approach54, explicitly accounting for spin polarization; a suited approach for pristine MXenes and transition metals upon, being such systems inherently metallic9. Even if most of the SAs on the MXenes resulted in non-magnetic solutions, the spin polarized calculations revealed a strong ferromagnetic character on Cr-based MXenes, in line with previous assessments by some of us55. All calculations were carried out including spin polarization, specifying from scratch an initial on-site magnetic moment of 0.1 μB per system atom, and allowing the calculations to converge to a self-consistent solution. The PBE-D3 DFT level of calculation has been previously shown to be appropriate and accurate to investigate MXenes chemical activity, reactivity, even SA attachment on them15,56,57,58.

The projector augmented wave (PAW) method, as implemented in VASP by Kresse and Joubert, was employed to describe the effect of core electrons on the valence electron density59,60, which was in turn expanded in a plane-wave basis set with a maximum kinetic energy of 415 eV, following previous studies, granting a chemical convergence with respect to the basis set completeness to be below the chemical accuracy of 1 kcal·mol-1, ca. 0.04 eV9,12,61. To sample the reciprocal space, an optimal Γ-centered Monkhorst-Pack mesh of 5×5×1 dimensions was chosen62, again ensuring energy convergence to be below ~0.04 eV9,12. The electronic energy optimization convergence criterion was set to 10-6 eV, while geometry optimization steps were stopped when forces acting on atoms were below 0.01 eV·Å-1.

The adsorbed TM SA minima were further characterized through vibrational frequency calculations by construction and diagonalization of the Hessian matrix. The Hessian matrix elements were gained by numerical derivatives of the analytical gradients, using finite displacements of 0.03 Å in length, as commonly used in the past12, and regarding only the adsorbate related normal modes, i.e. assuming decoupling of materials phonons and the adsorbed species vibrational frequencies. The energy of the isolated TMs was obtained by placing them in a box with 9×10×11 Å3 dimensions, to break symmetry and force the due orbital electronic occupancy with a smearing width below 0.1 meV. Aside, atomic energies in the most stable bulk crystallographic structure were also gained, needed when addressing their cohesive energy, see below.

To quantify the interaction between SA and the MXene surface, the adsorption energy, Eads, was defined as;

where \({E}_{{\rm{M}}/{{\rm{M}}}_{n+1}{{\rm{X}}}_{n}}\), \({E}_{{{\rm{M}}}_{n+1}{{\rm{X}}}_{n}}\), and \({E}_{{\rm{M}}}\) correspond to the total energies of the adsorbed metal (M) SA on the Mn+1Xn (0001) surface, the pristine Mn+1Xn (0001) surface model, and the isolated M in vacuum, respectively. Thus defined, exothermic adsorptions imply Eads < 0 values. All values include zero-point energy (ZPE), EZPE, defined as:

where E is the energy of the system, h is the Planck’s constant, and νi are each of the normal modes of vibration (NMV). In the case of adsorptions, vibrations belonged only to the SA, and so correspond to the three frustrated translations due to the bond with the substrate.

Besides, the Eads has been compared to the aforementioned M cohesive energy, Ecoh, in its bulk crystallographic structure63, here optimized at the PBE-D3 level as previously done64, and defining the difference between these two, Ediff, so that;

where Ecoh is the cohesive energy of the transition metal bulk per metal atom, defined as:

where N is the number of metal atoms in the bulk structure. This way, positive Ediff > 0 would imply that the M atoms would be more stable in the bulk environment than being SACs on the MXene, and this quantity is taken as a signature of SAC thermodynamic stability15,38,56 Conversely, Ediff < 0 implies that the bond of the SAC to the MXene is stronger than on the metal bulk, and so, such metal atoms would be thermodynamically driven to be as dispersed adatoms15,38,56.

Furthermore, kinetic aspects were analyzed; in particular, the SA diffusion energy barriers, to assess whether they could be rather high to prevent metal clustering, even in cases where thermodynamics would drive the system to. To do so, diffusion transition states (TSs) were located using the climbing-image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method using four middle images65, and exploring diverse diffusion paths34. Most SAs presented the TS at the bridge position in between Hfcc and Hhcp, although for few cases, the preferred diffusion path went over the T site. All TSs were confirmed as saddle points by the presence of a sole imaginary frequency along the reaction path when calculating vibrational frequencies, and the below provided diffusion energy barriers, Eb = ETS - \({E}_{{\rm{M}}/{{\rm{M}}}_{n+1}{{\rm{X}}}_{n}}\), have been ZPE corrected. Thus, a total of 1,620 diffusion barriers were estimated.

The gained Eads and Eb have been used to train and test different ML algorithms. As input features, 26 different values were initially considered, which can be classified according to belonging to the adsorbed or substrate species, and in the latter case, belonging to M or X elements, including numerical and categorical values. Such features included electronic, structural, and atomic properties, such as the cohesive energy of the SA bulk, the number of d electrons of the SA, the exfoliation energy of the MAX bulk to MXene, and atomic radii of either the SA metal or the MXene metal, to name a few. For a full list of features and further details, we address the reader to Table S1 of the Supporting Information (SI).

Different ML scheme models were tested, with the aim of establishing a relationship between adsorption and diffusion energies with few predominating features. In particular, twelve ML algorithms were analyzed, including the AdaBoost regressor (ABR)66, the elastic net regressor (ENR)67, the gradient boosting regressor (GBR)68, the k-neighbors regressor (KNR)31,69, the kernel ridge regressor (KRR)70,71, the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regressor (LASSO)47, the partial least squares (PLS)72, the random forest regressor (RFR)47, the decision tree regressor (DTR)47, the support vector regression (SVR)47, the ridge regression (RR)47, for specific details of the different methods the reader is referred to the specialized literature. For comparison, the simple linear regression (LR) was also considered. The ML analysis was carried out using an open-source Python distribution platform to train the models via scikit-learn libraries47.

From the complete data set —1,620 Eads and Eb values—, 80% was randomly selected to train the ML models, while the remaining 20% was employed for validation. The selection was made using cross validation to avoid overfitting, with 30 splits to ensure that all data was being used at least once in either the training or testing sets. All features were properly standardized by removing the mean and scaling to unit variance using the standard scaler provided by scikit-learn. The stability and accuracy of all models were evaluated through the regression coefficient, R, and the mean absolute error (MAE). From an initial analysis using default scikit-learn ML model values, a more thorough analysis was carried out for the final selected model refining the default hyperparameters using an exhaustive grid search with five-fold cross validation, as implemented by scikit-learn GridSearchCV class47.

Supplementary information

The online version contains the features used in the ML models. Table with results of preferred adsorption site, Eads, Ediff, and Eb for all TM and MXenes considered. Eads, Ediff, and Eb heatmaps for MXenes with n = 2 and 3. Trends of Eads vs. Bader charges, and parity plot of Q of C-based vs. N-based MXenes. This is available at

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. Any additional data is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Naguib, M. et al. Two-dimensional nanocrystals produced by exfoliation of Ti3AlC2. Adv. Mater. 23, 4248–4253 (2011).

Ren, C. E. et al. Charge- and size-Selective ion sieving through Ti3C2Tx MXene membranes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 4026–4031 (2015).

Li, X. et al. MXene chemistry, electrochemistry and energy storage applications. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 389–404 (2022).

Meng, L., Yan, L. K., Viñes, F. & Illas, F. Effect of terminations on the hydrogen evolution reaction mechanism on Ti3C2 MXene. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 6886–6900 (2023).

Urbankowski, P. et al. Synthesis of two-dimensional titanium nitride Ti4N3 (MXene). Nanoscale 8, 11385–11391 (2016).

Anasori, B. & Gogotsi, Y. 2D Metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes). Springer 1, 1–534 (2019). .

Kamysbayev, V. et al. Covalent surface modifications and superconductivity of two-dimensional metal carbide MXenes. Science 369, 979–983 (2020).

Gouveia, J. D., Viñes, F., Illas, F. & Gomes, J. R. B. MXenes atomic layer stacking phase transitions and their chemical activity consequences. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 054003 (2020).

Ontiveros, D., Vela, S., Viñes, F. & Sousa, C. Tuning MXenes towards their use in photocatalytic water splitting. Energy Environ. Mater. 7, e12774 (2024).

Bhat, A., Anwer, S., Bhat, K. S., Mohideen, M. I. H. & Qurashi, A. Prospects, challenges and stability of 2D MXenes for clean energy conversion and storage applications. npj 2D Mater. Appl 5, 61 (2021).

An, Y. et al. Two‑dimensional MXenes for flexible energy storage devices. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 4191–4250 (2023).

Dolz, D. et al. Understanding the reverse water gas shift reaction over Mo2C MXene catalyst: A holistic computational analysis. ChemCatChem 16, e202400122 (2024).

Rocha, H., Gouveia, J. D. & Gomes, J. R. B. Transition metal atom adsorption on the titanium carbide MXene: Trends across the periodic table for the bare and O-terminated surfaces. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 105801 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Theoretical study on lithium storage performance of V-doped Ti2CO2 MXene. RSC Adv. 14, 19945–19952 (2024).

Oschinski, H., Morales-García, Á & Illas, F. Interaction of first-row transition metals with M2C (M = Ti, Zr, Hf, V, Nb, Ta, Cr, Mo, and W) MXenes: A quest for single-atom catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C 125, 2477–2484 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Single platinum atoms immobilized on an MXene as an efficient catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Catal 1, 985–992 (2018).

Cheng, Y., Dai, J., Song, Y. & Zhang, Y. Single molybdenum atom anchored on 2D Ti2NO2 MXene as a promising electrocatalyst for N2 fixation. Nanoscale 11, 18132–18141 (2019).

Li, L. et al. Theoretical screening of single transition metal atoms embedded in MXene defects as superior electrocatalyst of nitrogen reduction reaction. Small Methods 3, 1900337 (2019).

Yang, X. et al. Identification of efficient single-atom catalysts based on V2CO2 MXene by ab initio simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C 124, 4090–4100 (2020).

Zhou, H. et al. Engineering the Cu/Mo2CTx (MXene) interface to drive CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Nat. Catal. 4, 860–871 (2021).

Fung, V., Hu, G., Ganesh, P. & Sumpter, B. G. Machine learned features from density of states for accurate adsorption energy prediction. Nat. Commun. 12, 88 (2021).

Abraham, B. M. et al. Machine learning-driven discovery of key descriptors for CO2 activation over two-dimensional transition metal carbides and nitrides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 30117–30126 (2023).

Andersen, M., Levchenko, S. V., Scheffler, M. & Reuter, K. Beyond scaling relations for the description of catalytic materials. ACS Catal. 9, 2752–2759 (2019).

Abraham, B. M. et al. Catalysis in the digital age: Unlocking the power of data with machine learning. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 14, e1730 (2024).

Piqué, O. et al. Charting the atomic C interaction with transition metal surfaces. ACS Catal. 12, 9256–9269 (2022).

Praveen, C. S. & Comas-Vives, A. Design of an accurate machine learning algorithm to predict the binding energies of several adsorbates on multiple sites of metal surfaces. ChemCatChem. 12, 4611 (2020).

Hammer, B. & Nørskov, J. K. Theoretical surface science and catalysis—calculations and concepts. Adv. Catal. 45, 71–129 (2000).

Torres, D., López, N., Illas, F. & Lambert, R. M. Why copper is intrinsically more selective than silver in alkene epoxidation: Ethylene oxidation on Cu(111) versus Ag(111). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 10774–10775 (2005).

Allés, M., Meng, L., Beltrán, I., Fernández, F. & Viñes, F. Atomic hydrogen interaction with transition metal surfaces: A high-throughput computational study. J. Phys. Chem. C 128, 20129–20139 (2024).

Ontiveros, D., Viñes, F. & Sousa, C. Bandgap engineering of MXene compounds for water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 13754–13764 (2023).

Goldsmith, B. R., Esterhuizen, J., Liu, J. X., Bartel, C. J. & Sutton, C. Machine learning for heterogeneous catalyst design and discovery. AIChE J 64, 2311–2323 (2018).

Persson, I. et al. 2D transition metal carbides (MXenes) for carbon capture. Adv. Mater. 31, 1805472 (2019).

Zhou, H. et al. Two-dimensional molybdenum carbide 2D-Mo2C as a superior catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 12, 5510 (2021).

Manadé, M., Viñes, F. & Illas, F. Transition metal adatoms on graphene: A systematic density functional study. Carbon 95, 525–534 (2015).

García-Romeral, N., Morales-García, Á, Viñes, F., Moreira, I. P. R. & Illas, F. How does thickness affect magnetic coupling in Ti-based MXenes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 17116–17127 (2023).

Jurado, A., Ibarra, K., Morales-García, Á, Viñes, F. & Illas, F. Adsorption and activation of CO2 on nitride MXenes: Composition, temperature, and pressure effects. ChemPhysChem. 22, 1837–1846 (2021).

Gouveia, J. D., Morales-García, Á, Viñes, F., Gomes, J. R. B. & Illas, F. MXenes à la carte: Tailoring the epitaxial growth alternating nitrogen and transition metal layers. ACS Nano 16, 12541–12552 (2022).

Kim, S., Gamallo, P., Viñes, F., Lee, J. Y. & Illas, F. Substrate-mediated single-atom isolation: dispersion of Ni and La on γ-graphyne. Theor. Chem. Acc. 136, 80 (2017).

Henkelman, G., Arnaldsson, A. & Jónsson, H. A fast and robust algorithm for Bader decomposition of charge density. Comput. Mater. Sci. 36, 254–360 (2006).

Bader, R. F. W. A quantum theory of molecular structure and its applications. Chem. Rev. 91, 893–928 (1991).

Ridier, K. et al. Unprecedented switching endurance affords for high-resolution surface temperature mapping using a spin-crossover film. Nat. Commun. 11, 3611 (2020).

Jedidi, A. et al. Exploring CO dissociation on Fe nanoparticles by density functional theory-based methods: Fe13 as a case study. Theor. Chem. Acc. 133, 1430 (2014).

Niu, K., Björk, J. & Rosen, J. First-principles exploration of Sc- and Y-based MXenes with halogen terminations. npj 2D Mater. Appl 9, 69 (2025).

Downes, M. et al. M5X4: A family of MXenes. ACS Nano 17, 17158–17168 (2023).

James, A. M. & Lord, M. P. Macmillan’s chemical and physical data. London: Macmillan (1992).

Dolz, D., Morales-García, Á, Viñes, F. & Illas, F. Exfoliation energy as a descriptor of MXenes synthesizability and surface chemical activity. Nanomaterials 11, 127 (2021).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Ontiveros, D., Vela, S., Viñes, F. & Sousa, C. MXgap: A MXene learning tool for bandgap prediction. ACS Catal 15, 14403–14413 (2025).

Janthon, P., Viñes, F., Sirijaraensre, J., Limtrakul, J. & Illas, F. Carbon dissolution and segregation in platinum. Catal. Sci. Technol. 7, 807–816 (2017).

Araujo, R. B., Rodrigues, G. L. S., dos Santos, E. C. & Pettersson, L. G. M. Adsorption energies on transition metal surfaces: Towards an accurate and balanced description. Nat. Commun. 13, 6853 (2022).

Hu, J., Al-Salihy, A., Zhang, B., Li, S. & Xu, P. Mastering the d-band center of iron-series metal-based electrocatalysts for enhanced electrocatalytic water splitting. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 15405 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

García-Romeral, N., Morales-García, Á, Viñes, F., de Moreira, I. P. R. & Illas, F. The nature of the electronic ground state of M2C (M = Ti, V, Cr, Zr, Nb, Mo, Hf, Ta, and W) MXenes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 31153–31164 (2023).

Keyhanian, M., Farmanzadeh, D., Morales‑García, Á & Illas, F. Effect of oxygen termination on the interaction of first row transition metals with M2C MXenes and the feasibility of single‑atom catalysts. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 8846–8855 (2022).

Morales‑Salvador, R., Morales‑García, Á, Viñes, F. & Illas, F. Two‑dimensional nitrides as potential candidates for CO2 capture and activation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 17117–17124 (2018).

Athawale, A., Abraham, B. M., Jyothirmai, M. V. & Singh, J. K. MXene-based single-atom catalysts for electrochemical reduction of CO2 to hydrocarbon fuels. J. Phys. Chem. C 127, 24542–24551 (2023).

Joubert, D. & Kresse, G. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Gouveia, J. D., Morales-García, Á, Viñes, F., Illas, F. & Gomes, J. R. B. MXenes as promising catalysts for water dissociation. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 260, 118191 (2020).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 13, 5188 (1976).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater 1, 011002 (2013).

Vega, L. & Viñes, F. Generalized gradient approximation adjusted to transition metals properties: Key roles of exchange and local spin density. J. Comput. Chem. 41, 2598–2603 (2020).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Freund, Y. & Schapire, R. E. Experiments with a new boosting algorithm. In proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML'96). Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA, 148–156 (1996).

Lamoureux, P. S. et al. Machine learning for computational heterogeneous catalysis. ChemCatChem 11, 3581–3601 (2019).

Chen, C. et al. A critical review of machine learning of energy materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1903242 (2020).

Gu, G. H. et al. Progress in computational and machine-learning methods for heterogeneous small-molecule activation. Adv. Mater. 32, 1907865 (2020).

Rupp, M. Machine learning for quantum mechanics in a nutshell. Int. J. Quantum. Chem. 115, 1058 (2015).

Noh, J., Back, S., Kim, J. & Jung, Y. Active learning with non-ab initio input features toward efficient CO2 reduction catalysts. Chem. Sci. 9, 5152–5159 (2018).

Panapitiya, G. et al. Machine-learning prediction of CO adsorption in thiolated, Ag-alloyed Au nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 17508–17514 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MCIN) and Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and, as appropriate, by “European Union Next Generation EU/PRTR”, for grants PID2021-126076NB-I00, PID2020-115293RJ-I00, PID2024-159906NB-I00, TED2021-129506B-C22, and CNS2024-154493, funded partially by FEDER Una manera de hacer Europa, as well as for the Unidad de Excelencia María de Maeztu CEX2021-001202-M granted to the IQTCUB. The COST Action IG18234 is also acknowledged, as well as Generalitat de Catalunya funding through 2021SGR00079 grant. F.V. thanks the ICREA Academia Award 2023 Ref. Ac2216561, and D. D. thanks Generalitat de Catalunya for his FI predoctoral contract with Ref. BDNS 657443. Finally, we thank the Red Española de Supercomputación (RES) for the computational resources used to complete the project (QHS-2022-1-0006 and QHS-2021-3-0006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.V. conceived the project. A.M.G. and F.V. supervised the DFT calculations and ML tools creation. D.D. and S.P. did all DFT calculations, and D.D. carried out all the ML coding and analysis, including Tables and Figures preparation. D.D. wrote the initial draft, which was later revised with contributions from S.P., A.M.G., F.I. and. F.V. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dolz, D., Pibernat, S., Morales-García, Á. et al. Accurate Prediction of Adsorption and Diffusion Energies of Single Metal Atoms Supported on MXenes from Machine Learning. npj 2D Mater Appl 10, 2 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00638-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00638-1