Abstract

Early identification of cerebral small vessel disease related cognitive impairment (CSVD-CI) is crucial for timely clinical intervention. We developed a Transformer-based deep learning model using white matter hyperintensity (WMH) radiomics features from T2-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images to detect CSVD-CI. A total of 783 subjects (161 longitudinally followed) were enrolled from three centres for model development and external validation, using a domain adaptation strategy. The model achieved AUCs of 0.841 (training) and 0.859/0.749 (validation cohorts), outperforming conventional machine learning models. The gradient-weighted class activation mapping approach highlighted WMH textural features, particularly the logarithm-transformed gray level size zone matrix features, as key contributors. These features were significantly correlated with CSVD macro- and microstructural changes, mediated age-cognition relationships and predicted longitudinal cognitive decline. Our findings indicate that WMH radiomics features, reflecting CI-related biological changes in CSVD, combined with a Transformer-based deep learning model, constitute a feasible, automated, and non-invasive tool for CSVD-CI detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cognitive impairment (CI) or even dementia is one of the final major outcomes of cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD)1,2,3. Early identification of CSVD-CI is crucial for timely clinical intervention. Nevertheless, early detection is frequently overlooked owing to limited awareness of cognitive assessments among patients and healthcare providers, the reliance on specialized professionals, and inadequate patient compliance4. Objective detection tools are particularly important. White matter hyperintensity (WMH) is the most common image representation of CSVD5, known to double the risk of incident dementia and connect with dementia-related pathological processes5,6,7,8. Given its high prevalence, affecting over 70% of the Chinese population aged 35 to 80 years9, WMH-based imaging biomarkers offer significant potential for early detection and warning of CSVD-related cognitive decline. However, effective characterization of WMH lesions remains a challenge. The visual assessment is inherently subjective and the relationship between WMH volume quantification and CI was nonlinear6,7,10. WMH shape descriptors were still crude proxies for heterogeneous changes underlying CSVD11. WMH lesions undergo a spectrum of pathological changes, from mild extracellular matrix destruction to varying degrees of demyelination and axonal loss12. Thus, non-invasive MRI features capable of capturing subtle changes can be beneficial, such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) or perfusion weighted imaging8,11,13, which had been reported to identify WMH-related CI with an accuracy of 78.8% to 86.11%14,15,16. But their limited availability in routine clinical settings hinders broader clinical application.

Radiomic features (RFs) of WMH on T2-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (T2-FLAIR) sequence, including size, histogram, shape and high-order textural features17,18, enable the extraction of above advanced features using routine clinical sequences19. RFs can quantify intensity variations and capture information imperceptible to human vision20. White matter textural features have also been identified as independent predictors of CI at the group level19. However, the automated detection or prediction of CSVD related CI based on RFs at the individual level is still under exploration. Besides, the ‘black-box’ algorithms21 of previous radiomics models had an opaque decision-making framework that cannot be decomposed into individually intuitive components, limiting interpretability. It remains unclear which RFs types contribute most to the identification or prediction of CI, and their clinical relevance in relation to neurobiological and neuropsychological measures is yet to be elucidated. Model generalization and robustness are also critical, both in specific subgroups and different institutions21. Nonetheless, previous radiomics models often lacked external validation22.

In this study, we aimed to establish an automated cognitive detection and prediction model in multisite CSVD patients based on WMH RFs extracted from T2-FLAIR images, and to investigate the contribution of WMH RFs to CSVD-CI. Specially, we employed an interpretable Transformer-based model to leverage all extracted RFs and embedded domain adaptation to address cross-centre variability. Conventional machine learning models were also constructed for comparative performance evaluation. Gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) approach was adopted to visualize the importance of RFs classes. Additionally, we assessed the model from two other independent external cohorts, DTI microstructure and plasma axonal injury biomarkers. And we verified the predictive effect of key textural features in a longitudinal cohort, demonstrating that key texture features detected by this model might be early predictive biomarkers of future cognitive decline in CSVD patients.

Results

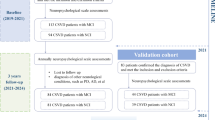

Patient enrolment and baseline characteristics

A total of 783 subjects from three cohorts were included (Fig. S1) and the clinical characteristics at baseline were shown in Table 1. The mean ages, educations and gender ratios were significantly different among cohorts. Overall, the datasets from the three cohorts were significantly distinct, and the composition of the subjects significantly differed in demographic information, cognitive assessments and imaging CSVD burden. All the subjects in three cohorts were classified into CSVD without cognitive impairment (CSVD-nonCI) group and the CSVD-CI group. The clinical information of the training cohort was shown in Table S1. The CSVD-CI group (n = 226) had higher age, lower education levels and higher proportion of hypertension history (all P < 0.05) compared to CSVD-nonCI group. CSVD-CI patients also displayed significantly decreased cognitive domain scores than the normal cognition group (all P < 0.001). The detailed clinical information of patients with different cognitive statuses in another two validation datasets showed similar trends and was summarized in Table S2, 3.

WMH radiomic features on T2-FLAIR

After WMH from T2-FLAIR was segmented (Fig. 1a), the RFs of WMH were extracted using Pyradiomics23 (Fig. 1b). On the original images of each WMH, 7 classes of RFs were extracted, including shape descriptors (14 features), first-order statistics (18 features), gray level co-occurrence matrix (glcm) (24 features), gray level dependence matrix (gldm) (14 features), gray level run length matrix (glrlm) (16 features), gray level size zone matrix (glszm) (16 features), and neighbouring gray tone difference matrix (ngtdm) (5 features). In total, there are 107 features per original image. (detailed RFs extracted from original images are listed in Table S4). At the same time, enabled 13 filters were applied to the original images, including wavelet, Laplacian of Gaussian (log), square, square root, logarithm, exponential, gradient, and local binary pattern filters23 (Fig. S2). For each filtered image, we extracted 6 above classes of RFs except for shape descriptors, which are independent of intensity values and can only be extracted from unfiltered images. In total, 85 classes and 1316 features were obtained per subject for developing the detection model (Fig. S2). Every RF is identified by a unique name, which consists of the applied filter, the feature class and the feature name.

A The training process of the model. This deep learning training process includes two branches: supervised training using data with expert diagnosis results and unsupervised training using data from other centres without expert diagnosis results. a ROI extraction. LST toolbox was used to automatically segment WMH. Two senior neurologists corrected manually. b RFs extraction: Engineered RFs were extracted first, and then a transformer architecture was used to extract DL RFs. The blue bar represents the extracted engineered RFs. The grey bar represents the zero paddings. The green bar represents the positional embeddings. The red bar represents the DL RFs. c CI prediction: DL RFs were used to predict CI. d Domain adaptation. The domain discriminator was used to discriminate DL RFs from the source and the target domains, which enables the transformer models to learned to extract DL RFs that are both discriminative and invariant to the change of domains. B The external verification process of the model. Two independent cohorts from the Zheer and Xianlin communities were verified in the above model in a supervised manner. The output classification results were compared to expert annotations. e Grad-CAM. Grad-CAM uses the gradient information flowing into the Norm layer of the penultimate Transformer block to produce a heatmap highlighting the important RFs that correspond to the decision of the model. CI cognitive impairment, DL deep learning, Grad-CAM gradient-weighted class activation mapping, RFs radiomic features, ROI area of interest, WMH white matter hyperintensity. The figure was created using Microsoft PowerPoint.

The construction and the training of the Transformer-based model

WMH RFs on T2-FLAIR of each subject from the training cohort (n = 572, with corresponding expert diagnostic label of CSVD-CI or CSVD-nonCI) were used for deep learning using a hierarchical Transformer architecture (Fig. 1b). Five-fold cross-validation was performed during the training process. The number of images in each fold was detailed in Table S5. In all folds, the model could detect those with CSVD related CI with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.841 ± 0.016 (Fig. 2A). The classification of CSVD-CI versus CSVD-nonCI achieved an accuracy of 0.798 ± 0.021, sensitivity of 0.793 ± 0.108, specificity of 0.800 ± 0.065, precision of 0.716 ± 0.055 and recall of 0.793 ± 0.108 (Table 2).

A ROC curves of five-fold cross-validation results for diagnosing cognitive impairment in CSVD patients from the training cohort. B The validation datasets of the training cohort were stratified into different subgroups, and there was no significant difference in the detection efficacy of the model between different age levels, different education levels, different genders, different severities of WMH or patients with and without CMBs (DeLong’s test, all P > 0.05). The AUC value for cognitive impairment was significantly higher in CSVD patients without LI than in CSVD patients with LI (DeLong’s test, P < 0.001). C ROC curve for detecting cognitive impairment in CSVD patients from the hospital-based external validation cohort. D ROC curve for detecting cognitive impairment in CSVD patients from the community cohort. **p < 0.001. AUC area under the curve, CMBs cerebral microbleeds, CSVD cerebral small vessel disease, edu education, LI lacunar infarction, ROC receiver operating characteristic, WMH white matter hyperintensity. Figure 2A, C and D were created using Python (v3.11); Fig. 2B was created using GraphPad Prism 8.

Subgroup analysis showed that there was no significant difference in the AUC values of the model among different sexes, different age levels or different education levels (DeLong’s test, all P > 0.05). In addition, the model’s performance was not affected by WMH severity or the presence of cerebral microbleeds (CMBs). However, the presence of lacunar infarction (LI) significantly impacted model efficacy (AUC = 0.865 in CSVD patients without LI vs AUC = 0.674 in those with LI; DeLong’s test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B).

Furthermore, the correlation analysis between the output values and clinical indicators revealed that the classification outputs were positively correlated with age (P < 0.001, r = 0.403; Fig. S3A) and homocysteine quantification (P = 0.017, r = 0.214; Fig. S3C) but were negatively correlated with years of education (P < 0.001, r = −0.147; Fig. S3B). Interestingly, the correlations between classification outputs and cognitive domain function scores were all significant (all P values were <0.001; Fig. S3D–H).

Comparison with conventional machine learning models

We constructed three conventional machine learning models using the same training cohort. As shown in Table 2, the Transformer-based deep learning model achieved a higher AUC (0.841) than the Random Forest (AUC = 0.820), Support Vector Machine (SVM) (AUC = 0.770) and XGBoost (AUC = 0.813) models. Also, it outperformed these three conventional machine learning models in terms of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision and recall.

External validation of the Transformer-based model with domain adaptation

To enhance the generalization capability of this Transformer-based model, the external cohorts were utilized in an unsupervised manner during the training process, ensuring that the feature extractor captured latent feature representations with a consistent distribution between the training cohorts and the external cohorts, just termed domain adaption. Using this strategy, two independent cohorts from another independent hospital and a community were verified. The results indicated that the former had a slightly better performance: the AUC was 0.859 (95% CI, 0.781–0.935) (Fig. 2C), the accuracy was 0.833 (95% CI, 0.743–0.902), the sensitivity was 0.938 (95% CI, 0.828–0.987), the specificity was 0.729 (95% CI, 0.582–0.847), the precision was 0.776 (95% CI, 0.684–0.847) and the recall was 0.938 (95% CI, 0.828–0.987). The latter also suggested that the model is valid. The AUC was 0.749 (95% CI, 0.657–0.841, Fig. 2D), accuracy was 0.714 (95% CI, 0.621–0.796), sensitivity was 0.683 (95% CI, 0.550–0.797), specificity was 0.750 (95% CI, 0.611–0.860), precision was 0.759 (95% CI, 0.656–0.839), and recall was 0.683 (95% CI, 0.550–0.797).

External validation performance without domain adaptation

To validate the value of domain adaptation, we conducted an ablation experiment excluding the unsupervised domain adaptation branch. Results demonstrated significantly lower AUC values in the model without domain adaptation compared to adapted model across both cohorts: Independent hospital cohort: 0.821 vs 0.859 (P = 0.026 by DeLong’s test); Community cohort: 0.668 vs 0.749 (P = 0.0002 by DeLong’s test). The detailed model performance was shown in Table S6.

Visualization and clinical interpretability of key radiomic features

Visualization of key RFs class by Grad-CAM

The visualization of the model in two external validation datasets was generated by Grad-CAM heatmaps. As shown in Fig. 3A, B, the importance of 85 classes of RFs was normalized to 0 to 1, the heatmaps illustrated the contribution of each RFs class to the classification of patients predicted as CSVD-CI. The salient features highlighted by Grad-CAM were largely consistent across the datasets, suggesting robustness in the model’s learned feature importance and its generalization capability. Forty RFs categories contributed to the classification performance of the model (importance>0). The top ten most important feature classes were shown in Fig. 3C. The most important RF type was glszm features based on logarithm filtered images (logarithm_glszm) in both cohorts, and the mean importance was 0.996. The logarithm_glszm category contains 16 specific RFs. Next, we would conduct clinical correlation analyses of these features to enhance the interpretability of the model.

A, B Grad-CAM of engineered radiomics features in two independent external validation datasets. The heatmap shows the contribution of each RF class to the prediction. The abscissa of the heatmap showed the cases identified as CSVD-CI by this model in each dataset, and the ordinate showed 85 RFs classes. C Comparisons of the top 10 most important radiomics features classes identified in the two validation cohorts. D Comparisons of key radiomics features between groups of CSVD-CI and CSVD-nonCI showed that all RFs of logarithm_glszm were significantly different between the two groups (P all <0.001). **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001, ****p < 0.00001. CI cognitive impairment, RFs radiomic features, glszm grey-level size zone matrix, WMH white matter hyperintensity. Figure 3A–C were created using Python (v3.11); Fig. 3D was created using R (v4.2.2).

The logarithm_glszm features differed significantly between groups of CI and nonCI

We compared the difference in values of the key RFs between the CI group and the nonCI group and found that all RFs of logarithm_glszm were significantly different between the two groups (P all <0.001, Fig. 3D). Among which, the values of logarithm_glszm_ GreyLevelNonUniformity, logarithm_glszm_GrayLevelVariance, logarithm_glszm_HighGrayLevelZoneEmphasis, logarithm_glszm_LargeAreaEmphasis, logarithm_glszm_LargeAreaHighGrayLevelEmphasis, logarithm_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity, logarithm_glszm_SmallAreaHighGrayLevelEmphasis, logarithm_glszm_ZoneEntropy and logarithm_glszm_ZoneVariance in CSVD-CI group were larger than those in CSVD-nonCI group; while the values of logarithm_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformityNormalized, logarithm_glszm_LargeAreaLowGrayLevelEmphasis, logarithm_glszm_LowGrayLevelZoneEmphasis, logarithm_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformityNormalized, logarithm_glszm_SmallAreaEmphasis, logarithm_glszm_SmallAreaLowGrayLevelEmphasis and logarithm_glszm_ZonePercentage in CSVD-CI group were significantly smaller than those in CSVD-nonCI group.

The logarithm_glszm features of WMH mediated the relationship between age and cognitive domain scores

Next, the relationships between logarithm_glszm RFs and the cognitive scores of CSVD-CI patients were analyzed. The results showed that GreyLevelNonUniformity, LargeAreaEmphasis, LargeAreaHighGrayLevelEmphasis, SizeZoneNonUniformity, ZoneEntropy and ZoneVariance features based on logarithm transformed images were negatively correlated with all cognitive domain scores (P < 0.05); LowGrayLevelZoneEmphasis, SizeZoneNonUniformityNormalized, SmallAreaEmphasis, SmallAreaLowGrayLevelEmphasisa and ZonePercentage features based on logarithm transformed images were positively related to cognitive domain scores (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A).

A Heatmaps of correlations between the most important class of radiomic features and clinical cognitive scores. The blue circle represents the positive correlation, the red circle represents the negative correlation, the larger the diameter of the circle, the larger the absolute value of the correlation coefficient. B, C The mediation analyses suggested that the logarithm_glszm_ZoneEntropy feature of WMH mediated the effect of age on general cognitive function and language function. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. RFs radiomic features, glszm grey-level size zone matrix, WMH white matter hyperintensity.Fig. 4A was created using R (v4.2.2); Fig. 4B, C were created using Microsoft PowerPoint.

Then, mediation analyses were performed to further elucidate the role of WMH RFs in age-related cognitive decline. Notably, the results suggested that logarithm_glszm_ZoneEntropy values slightly but significantly mediated the relationship between age and general cognition (indirect effect: −0.1035, 95% CI: [−0.1399, −0.0723], Fig. 4B) as well as the correlation between age and language function (indirect effect: −0.0721, 95% CI: [−0.1073, −0.0425], Fig. 4C).

The logarithm_glszm features were significantly related to other CSVD macro-and microstructural markers

We further investigated the biological annotations of key textural features in relation to macro- and microstructural damages. As shown in Table S7, all the RFs of logarithm_glszm were significantly related to the WMH volumes, numbers of LIs and numbers of CMBs.

WMH is myelin or axonal damage that can be detected by MRI/DTI, which provides detailed information on the microstructure and integrity of white matter fibre tracts. Among all subjects in the training dataset, DTI sequences were collected in 501 patients. As shown in Table S8 and S9, a total of 40 diffusion features were extracted, including fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD) metrics of 20 atlas-based tracts (detailed in Appendix E5). Feature selection was conducted among the above 40 diffusion features by the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) with 10-fold cross-validation. The selection of the lambda values was shown in Fig. 5A, B, and 12 important DTI metrics (i.e., those with non-zero weights, Fig. 5C) were selected as inputs to train an SVM classifier then. The SVM model achieved a mean AUC of 0.813 in five-fold cross-validation (Fig. 5D), which was slightly lower than the AUC of the Transformer-based model.

A, B The hyperparameter (Lambda value) of LASSO regression was selected with the minimum MSE value (Lambda = 0.0115). C Twelve important DTI features were selected and their weight was listed. D The ROC curve of SVM model with five-fold cross-validation. E Heatmaps of correlations between the most important class of radiomic features and important DTI features. The blue circle represents the positive correlation, the red circle represents the negative correlation, the larger the diameter of the circle, the larger the absolute value of the correlation coefficient. The RF1 to RF16 refers to the 16 features of logarithm_glszm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Abbreviations: DTI diffusion tensor imaging, LASSO Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator, MSE mean square error, ROC receiver operating characteristic, SVM support vector machine. Figure 5A–D were created using Python (v3.11); Fig. 5E was created using R (v4.2.2).

To further support the clinical interpretability of this model, we examined the correlations between selected DTI parameters and key RFs. Most logarithm_glszm features showed significant correlations with FA or MD values in CSVD patients (Fig. 5E), suggesting that texture features can partially reflect the microstructural feature of white matter lesions.

Besides, we collected plasma neurofilament light chain (NFL) from subjects of the community cohort, which may reflect axonal damage24 and compared the correlation between plasma NFL and key RFs. The results showed that the NFL was positively associated with the value of logarithm_glszm_ZoneEntropy (P = 0.002, r = 0.292), logarithm_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity (P = 0.030, r = 0.211), logarithm_glszm_LargeAreaHighGrayLevelEmphasis (P = 0.029, r = 0.213) and logarithm_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity (P = 0.043, r = 0.197) (Details were shown in Fig. S4).

The key texture feature was a potential predictor of future cognitive progress in the longitudinal CSVD cohort

Finally, we assessed the ability of key textural features to predict cognitive outcomes in a longitudinal cohort. When comparing the correlations between the annual rate of changes in cognitive assessment and RFs, we found that a significant correlation existed only in the CSVD-CI group (Fig. 6A–H). Besides, the significant correlations between annual rate of change in the Beijing version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score and logarithm_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity (P < 0.001, r = −0.419), logarithm_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity(P = 0.021, r = −0.282), logarithm_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformityNormalized (P = 0.032, r = 0.263), logarithm_glszm_SmallAreaEmphasis(P = 0.039, r = 0.253) logarithm_glszm_ZonePercentage (P = 0.015, r = 0.297) remained when correcting potential covariates (age, sex, education and baseline cognitive state).

The red dots represent subjects in the CSVD-CI group and the blue triangles represent subjects in the CSVD-nonCI group. The annual rate of changes in the MoCA was significantly related to the values of logarithm_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity (A), logarithm_glszm_LargeAreaEmphasis(B), logarithm_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity (C), logarithm_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformityNormalized(D), logarithm_glszm_SmallAreaEmphasis (E), logarithm_glszm_ZoneEntropy(F), logarithm_glszm_ZoneVariance (G) and logarithm_glszm_ZonePercentage(H) in the CSVD-CI group. CSVD-CI cerebral small vessel disease patients with cognitive impairment, CSVD-nonCI cerebral small vessel disease patients without cognitive impairment, MoCA Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Figure 6A–H were created using GraphPad Prism 8.

Then we investigated the independent predictors of future cognitive progress. Fifty-five patients experienced a decline in cognitive scores during follow-up. On univariate Cox regression, only logarithm_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity (P = 0.043, hazard ratio [HR], 1.272) was a significant predictor of cognitive decline. In the multivariate regression, the logarithm_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity retained significance (P = 0.004, HR = 1.466). While the traditional CSVD biomarkers, including WMH volumes did not have a significant predictive effect on the decline of cognitive scores during follow-up.

Discussion

In this large-scale, multi-site analysis, we developed a hierarchical Transformer architecture with a fully attention-based network to generate an accurate and interpretable diagnostic and forecasting model for CSVD-CI using WMH RFs extracted from T2-FLAIR images. The consistently high performance of the model—demonstrated by an AUC of 0.841 in the training dataset, 0.859 in an external hospital-based validation cohort, and 0.749 in a community-based validation cohort—along with its stable performance across subgroup analyses, supports the robustness and generalizability of this deep learning model. The results of Grad-CAM confirmed the critical contribution of WMH textural features. The enrichment analyses linking key textural features to macroscopical CSVD markers, DTI-derived microstructure, plasma NFL, cognitive domain scores, and longitudinal cognitive changes further highlight the importance of WMH RFs as solid neurobiological substrates of CSVD-related cognitive decline.

We pioneered the use of WMH RFs as an automated diagnostic and prediction tool for CSVD-CI, which could complement and assist the traditional diagnostic process dependent on clinical expertise, cognitive assessments and visual interpretation of imaging findings1,25. The imaging-based model is more objective and avoids the influence of the learning effect on repeated neuropsychological tests26. Currently, only a limited number of studies have modelled the automated identification of CSVD-related CI using raw imaging data as input27,28, but the “black box” could not provide interpretable features for brain-behaviour analysis29. Here, our model based on extracted RFs showed comparable performance while restraining redundant features in original images30, thereby enhancing interpretability and improving ease-of-implementation31. Compared to other studies that employed DTI or functional MRI brain network indicators to identify CSVD-related CI15,16, our approach leveraged T2-FLAIR sequences, which are more widely available across medical institutions as part of routine clinical imaging. Therefore, this model could serve as a widely generalizable automated tool for CSVD-CI detection. If the model identifies a patient with CSVD-CI, we would recommend comprehensive neuropsychological assessments to confirm the diagnosis, along with implementation of regular follow-ups and personalized intervention strategies to prevent or mitigate progression to dementia.

This Transformer-based model outperformed three conventional machine learning models and demonstrated acceptable generalization across different centres. Several notable strengths of model construction merit attention. In contrast to extracting features directly from raw images30,32, our method first extracted engineered, hard-coded features, followed by a Transformer architecture for further deep learning feature extraction. The Transformers are a class of deep learning models originally applied for natural language processing33, which have been shown to be suitable for handling sequential data, like genomics data34, and result in better training time and performance35. The large receptive field of the Transformers34 allows many RFs without feature selection and avoids the loss of important information. In our model, 85 RFs class-level embeddings formed the input sequence to our Transformer encoder, enabling the network to learn structured relationships between feature groups—modelled as semantic tokens—via self-attention mechanisms. These hierarchical tokenization strategy offers several advantages:(1) Semantic coherence: Grouping features by class preserves interpretability and reduces noise from mixing heterogeneous feature types; (2) Efficient learning: Reducing the input length enhances computational efficiency and mitigates overfitting risks in Transformers; (3) Better generalization: By capturing class-wise interactions, this approach can uncover biologically meaningful dependencies in disease characterization.

It is also worth noting that the domain adaptation strategy36,37 was adopted to mitigate the harmful effects of domain shifts in this study. The goal of domain adaptation is to make the network unable to distinguish between the distributions of its training and test domain examples. One possible method is to map the deep learning features of the two domains into a common feature space. Adversarial adaptation methods have become an increasingly popular implementation of this type of approach, seeking to minimize the approximate domain discrepancy distance through an adversarial objective with respect to a domain discriminator38,39. As in generative adversarial learning, which pits two networks (a generator and a discriminator) against each other, we jointly optimized the feature extractor, label classifier, and domain discriminator. The domain discriminator works adversarially with the domain classifier, allowing the final classification decisions to be made based on features that are both discriminative and invariant to the change in domains, and the trained network can be applied to the target domain without being hindered by the shift between the two domains.

Nonetheless, the model exhibited performance variability between internal and external validation sets, most notably in the community-based cohort. Discrepancies likely stem from inter-site heterogeneity in imaging protocols, scanner specifications, disease severity (e.g., WMH grade ≥2 and LI prevalence), and demographic profiles (e.g., age distribution). RFs are sensitive to changes in image acquisition22. The internal dataset used for training and initial validation generally demonstrated balanced sensitivity and specificity, likely owing to its more homogeneous samples and better alignment with the model’s training distribution. In contrast, the external validation set—particularly the community-based cohort—exhibited relatively lower model performance, which may reflect its inherently greater population complexity and heterogeneity, including wider age ranges. We also observed that the model exhibited higher sensitivity but lower specificity in the hospital-based cohort, whereas the opposite pattern was found in the community-based cohort. These discrepancies may be attributable to the model’s focus on WMH radiomics. The hospital cohort demonstrated significantly more severe WMH (WMH grade 2 or higher) and a higher prevalence of concurrent LIs (Table 1), which likely enhanced sensitivity but reduced specificity due to confounding comorbidities. Conversely, the community cohort predominantly presented with mild or atypical white matter lesions, leading to lower model sensitivity. Although the three centres achieved acceptable model performance, it remained insufficient to fully bridge the gap between the source and target domains. Future work will explore more advanced adaptive techniques, including the incorporation of larger and more diverse multicenter datasets, to further improve the model’s robustness.

An additional strength of our model in accurately detecting CSVD-CI is its in-depth exploration of WMH lesion characteristics through RFs. Our longitudinal cohort verification revealed that key RFs, rather than conventional volumetric WMH measures, predict cognitive progress, which aligns with prior studies suggesting RFs provide additional information compared to volumetric quantification13. In cerebral white matter, the FLAIR contrast is determined indirectly by the attenuation of lipid protons within myelin40. WMH radiomics on FLAIR describe the intensity of individual voxels and their relationship to neighbouring voxels17, which are associated with underlying tissue properties13 including demyelination, myelin reparation and axonal loss12. These heterogeneous tissue damages within WMH caused cortico-subcortical disconnection, which is the theoretical basis of WMH’s contribution to CI.1 Technically, many RFs are derived from statistical-based methods that are invariant to the direction and size of the object and are also robust to noise41, making them suitable for irregular texture patterns of WMH lesions. In addition, robustness and generalizability are essential for clinical biomarkers. Previous studies have reported inconsistent associations between WMH burden and cognition across populations differing in age, sex, and lesion severity10,42,43,44. In contrast, WMH RFs demonstrated improved stability across subgroups in our multisite validation and stratified analyses, supporting their potential utility in heterogeneous clinical settings.

Furthermore, we adjusted Grad-CAM45, a visualization tool applied to computer vision tasks, to highlight the RFs that contribute most to the detections. Grad-CAM showed a consistent pattern of key RFs classes in different validation sets, and textural features, particularly the logarithm_glszm, was undoubtedly the most important feature class of CSVD-CI, whose clinical interpretability was then verified. Textural features captured the spatial variation in signal intensity and its relationship with adjacent intensity17,46. Glszm quantifies zones of voxels with identical grey levels and shows high stability across varying slice thickness47, potentially contributing to its significance in our model. Subsequent correlation analyses demonstrated significant associations between logarithm_glszm features and CSVD macrostructural markers, diffusion metrics from DTI, as well as plasma levels of NFL. DTI metrics reflect the integrity of the fibre microstructure48, NFL is a cytoskeletal component of large myelinated axons, and might be released into the blood upon axonal damage24. Collectively, these results indicate that key WMH textural features capture neuropathological alterations, thereby offering strong neurobiological support for the CSVD-CI prediction model based on WMH radiomic features.

When the features were correlated with behavioural scores, significant associations emerged between glszm features and cognitive scores, in accordance with the strong associations between the myelin density index and cognitive scores49. Mediation analyses revealed that WMH logarithm_glszm_ZoneEntropy mediated the relationship between age and both general cognition and language function, providing new insights into the potential mechanism of WMH on cognitive ageing. Glszm quantifies grey level zones, and ZoneEntropy measures the randomness and uncertainty of zone sizes and grey levels. Higher glszm_ZoneEntropy values indicate greater tissue heterogeneity, which reflects disruption of the organized structure of white matter due to myelin damage50—common in aging40. Longitudinal analysis found several textural features associated with the annual rate of cognitive decline, notably logarithm_glszm_Gray Level NonUniformity, which remained significant in the multivariate Cox regression. The logarithm_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity indicated tissue inhomogeneity51, and contributed to the both diagnosis and prediction of CSVD-CI. In contrast, WMH volume and shape provided limited information, underscoring the insufficiency of single-parameter metrics in reflecting cognitive impact. Besides, preprocessing steps such as logarithmic transformation seemed to improve the performance of the lesion detection52, potentially due to the combined effects of filtering and subsequent data augmentation.

This study had some limitations and further improvement may enhance the clinical applicability of the model. Firstly, we only studied WMH for CSVD and did not compare WMH to other diseases, like multiple sclerosis. We would like to expand the size and heterogeneity of the cohort to expand the clinical application and add the differential diagnosis in the next version of the model. Secondly, the subgroup analysis showed that the model performed significantly better in WMH without LI than with LI. The occurrence of infarction in key sites might directly cause CI53, so RFs of LI could be added to next model, too. Thirdly, in some high-level medical institutions, the availability of advanced imaging sequences such as DTI or fMRI and clinical data such as fluid biomarker information can certainly improve the detection performance of the model. Functional connectivity analysis based on fMRI may also contribute to a deeper understanding of the underlying neuropathological mechanisms. Based on the idea of stratified diagnosis and treatment, we will build a corresponding more optimized detection model according to hospital types and patient types in a later version. Fourthly, while our analysis prioritized the highest-ranked radiomic features (logarithm_glszm) to validate biological plausibility, the model’s performance derives from the collective contribution of all feature types. Future studies will delineate the unique and shared variance of these biomarkers in predicting CSVD-CI progression. Lastly, the images in longitudinal analysis were all part of the training set and multi-centre longitudinal data with larger samples are needed to develop a model to predict future cognitive decline at the individual level.

In conclusion, this interpretable deep learning model enabled the acquisition of high-accuracy signatures of the cognitive status of CSVD patients from routinely collected T2-FLAIR sequences, which was validated both on data from the other two independent centres and on subgroups. WMH textural features possessed accessibility, accuracy, generalizability and robustness as potential neuroimaging biomarkers for detection and prediction of CSVD-CI. Our approach can expand the scope of explainable artificial intelligence research on CSVD-CI. We believe that this automated, high-accuracy, routine sequence-dependent and universal framework can potentially serve as an auxiliary detection tool in future clinical practice.

Methods

Study populations and data collection

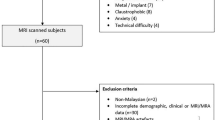

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (reference number: 2017-079-04) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. In the cross-sectional analysis, a total of 1142 candidate CSVD patients with varying degrees of WMH on T2-FLAIR were consecutively enroled between January 2017 and January 2022 from three independent centres (Registration number: ChiCTR-OOC-17,010,562). The inclusion criteria for CSVD: (1) aged 50 to 85 years, with or without the following symptoms: cognitive complaint, gait disorder, abnormal urination, personality/emotion changes, dizziness; (2) can be accompanied by a history of vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and a history of lacunar; (3) MRI: mild to severe WMH with or without LIs, CMBs or cerebral atrophy; (4) right-handedness. The exclusion criteria included (1) a history of ischaemic stroke with infarctions larger than 1.5 cm in diameter; (2) WMH mimics of origins other than small vessel disease (e.g., multiple sclerosis); (3) extracranial or intracranial large artery stenosis >50%; (4) intracranial haemorrhage; (5) Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease or other psychiatric disorders that may interfere with neuropsychological tests; and (6) MRI contraindications or claustrophobia. The patient recruitment workflow was shown in Fig. S1. Finally, 572 CSVD patients from Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (training cohort), 96 patients from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University (Zheer, Hospital-based external validation cohort) and 115 physical examination patients in the Xianlin community (Xianlin, Community-based external validation cohort) were enrolled in this study. Among those in the training cohort, 161 patients were re-evaluated for cognition during a follow-up of 1–6 years.

Cognitive profiling of CSVD patients was conducted through standardized neuropsychological assessments, including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the MoCA, and domain-specific cognitive evaluations (Appendix E3). Cognitive impairment (CI) was diagnosed if any of the following criteria were met: (1)MMSE score ≤ education-stratified thresholds (illiterate: ≤17; 1–6 years: ≤20; >7 years: ≤24);(2) MoCA score ≤ education-stratified thresholds (illiterate: ≤13; 1–6 years: ≤19; 7–12 years: ≤24; >12 years: <26);(3) Domain-specific deficit: ≥1.5 standard deviations below gender-adjusted means in any cognitive domain. Based on these criteria, patients were divided into the CSVD-CI group and the CSVD-nonCI group.

Demographic information, MRI and neuropsychological evaluation were collected for each subject. We simultaneously collected the homocysteine level of the patients in the training cohort, as it is also a common vascular risk factor for CSVD54. We also obtained quantitative results of NFL in subjects of Xianlin cohort, using a single-molecule array technology. CSVD markers including WMH volumes, number of LIs and CMBs were identified by two neurologists to avoid bias. Details about MRI configuration, CSVD markers and neuropsychological evaluations were shown in the Appendix E1-E3.

Radiomics analysis

The workflow of the radiomics analysis included WMH segmentation and RFs extraction. In the training cohort, three-dimensional segmentation of entire WMH lesions on T2-FLAIR (NIFTI format) was implemented using the LST toolbox version 3.0.0 (www.statistical-modelling.de/lst.html) for SPM12, generating individual WMH masks. Two senior neurologists blind to clinical information corrected the WMH mask manually by consensus via ITK-SNAP software (Fig. 1a). Then, a UNETR-based model (UNEt TRansformers)55 for WMH segmentation was subsequently trained on the manually curated annotations. The UNETR is specifically designed for 3D medical image segmentation and combines a Transformer-based encoder with a CNN-based decoder. Instead of traditional convolutional feature extraction, the encoder utilizes a pure Transformer to model long-range dependencies and capture contextual information from input volumes. The decoder employs skip connections to fuse multi-scale features and generate the final segmentation output. The model was optimized using a hybrid loss function combining cross-entropy loss and Dice loss. Training was conducted using the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, betas of (0.9, 0.999), and a weight decay of 0.00001. The model was trained for a maximum of 500 epochs, with early stopping applied if no performance improvement was observed over 50 consecutive epochs. This WMH segmentation model achieved a Dice coefficient of 0.74 in the validation set. This optimized model was then deployed for automated WMH segmentation in another two independent external validation cohorts. Feature extraction was performed using Pyradiomics23, with 1316 quantitative features encompassing 85 feature classes extracted per case. Detailed image preprocessing, specific feature classes and feature names were shown in Appendix E4 and Table S4.

Algorithm development and network architecture of the Transformer-based model

The study workflow was shown in Fig. 1. The overall network architecture was composed of a feature extractor, a label classifier, and a domain discriminator. The feature extractor contained an element padding block and a Transformer encoder. We first grouped the 1316 scalar radiomic features into 85 semantically meaningful feature classes (e.g., glcm, glrlm, shape, etc.). These 85 classes were treated analogously to patches in a Vision Transformer (ViT), where each class corresponds to one “token”. These input features may vary in dimension (5, 14, 16, 17, 18, 24, or 68). Therefore, for each feature class, a learnable linear projection layer was applied to map the set of scalar features into a fixed-dimensional embedding, producing one embedding vector per class. A learnable classification token of dimension 24 is prepended to the sequence. The final size of each token used as input to the Transformer encoder is 24 dimensions. These 85 embeddings were then fed into a Transformer encoder block consisting of eight stacked multi-head self-attention (MSA) layers and multilayer perceptrons (MLPs), with layer normalization and residual connections applied before and after each sublayer. Each self-attention module contained 12 heads with a total attention dimension of 768, and the MLPs consisted of two fully connected layers with Gaussian error linear unit (GELU) activations. This design enables the model to learn both intra-class feature structure (via the initial embedding projection) and inter-class dependencies (via self-attention), thereby forming a hierarchical abstraction pipeline. The final latent features extracted by the Transformer encoder were passed to an MLP-based classifier to predict cognitive function status. The domain discriminator for building consistency across multicentre data was composed of five convolutional blocks. A leaky ReLU was applied after the first four convolutional blocks.

To make the deep learning-based model more transparent and explainable, we adopted the Grad-CAM45 approach to understand which class of features played the most important roles in identifying cognitive dysfunction. The code was obtained from ‘https://github.com/jacobgil/pytorch-grad-cam’. Grad-CAM was originally intended to improve the explainability of artificial intelligence for computer vision tasks. We extended this approach by treating the input RFs as a one-dimensional image. Here, Grad-CAM used the gradient information flowing into the Norm layer of the penultimate Transformer block to produce a heatmap highlighting the important RFs that corresponded to the decision of the model. We generated Grad-CAM heatmaps respectively in two independent external validation sets. Heatmaps were only generated for samples with predicted labels of 1 (i.e., those predicted to have cognitive impairment). This focused approach ensures that visualizations highlight the features the model relied on when making clinically significant decisions, thereby avoiding noise from negative cases.

Training and verification process of the Transformer-based model

During the training process, the RFs of both the training cohort and the external validation cohort were separately fed into the feature extractor to acquire latent feature representations for each RF. Subsequently, the data flow was divided into two branches, namely a supervised branch and an unsupervised branch. In the supervised branch, the acquired latent features from the training cohort were input into the label predictor to learn the classification of cognitive impairment. The cross-entropy loss function was employed to measure the discrepancy between the predicted outcomes and expert diagnosis. A five-fold cross-validation strategy was adopted, wherein each iteration involved training the model on 4/5 of the data and validating it on the remaining 1/5 of the data. Due to the variations in data distribution across different centres, a detection model trained on one centre may not perform effectively on another. To enhance the generalization capability of the model, an unsupervised branch was introduced. In this branch, the latent features obtained from both the training cohort and the external validation cohort were fed into the domain discriminator. Through adversarial learning, the model acquired features that combine (i) discriminative value for identifying cognitive impairment and (ii) domain invariance across different centres. As a result, the features extracted from data originating from different centres exhibited the same distribution, enabling the supervised branch trained on the training cohort to generalize more effectively to the external validation cohort. The total loss used in our model was a weighted combination of supervised and unsupervised components. The supervised loss, derived from the binary classification task distinguishing CSVD patients with CI from those without CI, was calculated using the standard cross-entropy (CE) loss. The unsupervised loss, which supports the domain adaptation process, was computed using binary cross-entropy (BCE) with logits and applied to train a domain discriminator that distinguishes between source and target domains. These losses were not equally weighted; based on empirical evaluation, we set the weight of the unsupervised loss to 0.1 to balance effective domain alignment with classification stability. The model was trained for 200 epochs, and the checkpoint achieving the best performance on the validation set was selected for final testing. We used a learning rate of 1e-3 for the classifier and 5e-5 for the discriminator, with AdamW and Adam optimizers, respectively. Training was conducted on an NVIDIA V100 GPU with a peak memory usage of approximately 2621 MiB.

During external verification, the RFs of the external data were input into the model to obtain predictive results, which were then compared to expert annotations.

To further validate the impact of the domain adaptation strategy on model generalizability, we conducted additional model construction by discarding the unsupervised domain adaptation branch. The model was then externally validated on the identical independent external validation datasets, with their performance compared against validation results from the model incorporating the unsupervised domain adaptation branch.

The performance metrics of the model

Model evaluation indicators

To evaluate the performance of the model, for each fold during the five-fold cross-validation and each independent verification cohort, we generated the receiver operating curve (ROC) curve on the validation dataset and computed the AUC. Additionally, we calculated other model evaluation metrics, such as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision and recall.

Subgroup analysis

The datasets of the training cohort were dichotomized by age or education level according to the cut-off values in previous studies: age ≥ 60 years had a significant influence on the association between WMH and cognitive impairment10, and WMH was correlated with reduced performance in all cognitive domains in patients with < 11 years of education56. We assessed the detection performance of the model on the stratified data. In addition, since WMH is often accompanied by LIs and CMBs, which can also cause cognitive impairment, the detection efficacy was also compared between mild WMH (Fazekas grade 1) and moderate to severe WMH (Fazekas grade 2–3), with or without LIs and with or without CMBs.

Relationship of classification output with clinical risk factors and cognitive ability

To further verify the clinical relevance of this detection model, we analysed the correlations between the output probability of cognitive impairment and clinical risk factors (age and homocysteine) or cognitive domain scores.

Construction of conventional machine learning models using radiomic features

Using RFs from the training dataset, we developed three conventional machine learning models—Random Forest, SVM, and XGBoost—and compared their performance against our Transformer-based model. All algorithms were implemented using Python (version 3.11) with scikit-learn (version 1.6.1) and XGBoost (version 2.1.1) libraries. Standard scaling was used to normalize the radiomics features using the StandardScaler from scikit-learn, transforming each feature to have zero mean and unit variance. The Random Forest classifier was implemented using the RandomForestClassifier class from scikit-learn with the following hyperparameters: n_estimators=200 (number of trees), max_depth=10 (maximum tree depth), min_samples_split=5 (minimum samples required to split an internal node), min_samples_leaf=2 (minimum samples required in a leaf node), and random_state=42 (for reproducibility). The SVM classifier was constructed using the SVC class from scikit-learn, configured with a radial basis function (RBF) kernel to capture non-linear relationships in the data. The regularization parameter C was set to 10 to control the trade-off between achieving a low error on the training data and minimizing the model complexity. The gamma parameter, which defines the influence radius of samples selected by the model as support vectors, was set to ‘scale’, corresponding to 1/(n_features × X.var()). Additionally, probability=True was specified to enable probability estimates for ROC analysis. The XGBoost classifier was implemented using the XGBClassifier from the xgboost library with the following parameters: n_estimators=200 (number of gradient boosted trees), max_depth=6 (maximum tree depth), learning_rate=0.1 (step size shrinkage used to prevent overfitting), subsample=0.8 (fraction of samples used for fitting the individual trees), colsample_bytree=0.8 (fraction of features used for fitting the individual trees), and random_state=42 (for reproducibility).

DTI analyses

The atlas-based segmentation strategy was applied to investigate diffusion abnormalities in CSVD patients using DTI57. The DTI processing was detailed in Appendix E5 and we obtained 40 diffusion features, including both FA and MD metrics of 20 fibres based on JHU WM Tractography Atlas. Then, the LASSO regression method with 10-fold cross-validation was used to reduce the feature dimension and select significant fibre diffusion metrics. The Mean Squared Error (MSE) was calculated using the LassoCV function from the scikit-learn package (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.linear_model.LassoCV.html). The lambda value was selected with the minimum MSE value (Lambda = 0.0115). The SVM was conducted with five-fold cross-validation to validate the classification effect of the selected DTI metrics. The relationships between key RFs and significant fibre diffusion metrics were analysed.

Longitudinal data validation

A total of 161 subjects in the training cohort were followed up for 1–6 years (mean time of follow-up was 2.27 years). The MMSE and MoCA were re-evaluated on these subjects at follow-up. We calculated the value of the changes in the cognitive scale after follow-up for each subject, described as Δ MMSE and Δ MoCA; as well as the annual rate of changes in cognitive scale, described as ΔMMSE/year and Δ MoCA/year. The subjects with Δ MoCA/year >0 were stratified as cognitive progress group and those with Δ MoCA/year≤0 were stratified as cognitive score stable group. The calculation formulas were as follows:

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses and plotting were performed using SPSS software (v22.0, IBM), MedCalc, R (v4.2.2), Python (v3.11) and GraphPad Prism 8. Continuous variables normally distributed are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparison between/among groups. Continuous variables are expressed as median (25% quantile, 75% quantile) if non-normally distributed and Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis H test was performed. The chi-square test was used for categorical variables. When comparing the FA and MD values of 20 tracts, Bonferroni correction was executed to adjust the false-positive rate (P < 0.05/20). During the subgroup analyses, DeLong’s test using MedCalc was adopted to compare the AUC values of each subgroup.

Spearman correlation analysis was used to evaluate the correlation between the output probability of cognitive impairment and clinical data. The Spearman correlation coefficient test was also used to analyse the direction (positive or negative) and strength of the relationship between cognitive domain scores/DTI metrics/NFL and key RFs values. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Mediation analysis was conducted to explore whether WMH RFs mediated the relationship between age and cognitive scores. It was performed by Model 4 of PROCESS (V3.4.1), an extensive application for the SPSS framework, and the bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the mediating effect were also calculated with bootstrapping (k = 5000). If the 95% CI does not contain zero, the mediating effect is considered statistically significant. The detailed process of mediation analysis was shown in the Appendix E6. The variables for the mediation analysis were z-normalized to increase comparability.

When analysing the longitudinal data, both Spearman correlation analysis and partial correlation analysis adjusting for age, sex, education, baseline cognitive scores were performed to verify the relationship between key RFs and annual rate of changes in cognitive scale. The above analyses were performed separately in all follow-up cohorts, CSVD-nonCI group, and CSVD-CI group. Then, the ability of key RFs to distinguish subjects whose cognitive scales were declined during follow-up was determined. We initially conducted univariate Cox regression using CSVD markers and key WMH RFs, and those with significant differences were then included in multivariate Cox regression (corrected for age, sex, education and baseline cognitive state).

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author Y.X. on reasonable request.

Code availability

The underlying codes for this model have been deposited at github (https://github.com/iLifeSciences/CSVD-CI-Tr), which can only be used for non-commercial research purposes.

References

Inoue, Y., Shue, F., Bu, G. & Kanekiyo, T. Pathophysiology and probable etiology of cerebral small vessel disease in vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 18, 46 (2023).

Zanon Zotin, M. C., Sveikata, L., Viswanathan, A. & Yilmaz, P. Cerebral small vessel disease and vascular cognitive impairment: from diagnosis to management. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 34, 246–257 (2021).

González-Quevedo, A. et al. Incidental covert cerebral small vessel disease: Detection and management. Adv. Neurol. 0, https://doi.org/10.36922/an.4841 (2025).

Qiu, S. et al. Multimodal deep learning for Alzheimer’s disease dementia assessment. Nat. Commun. 13, 3404, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31037-5 (2022).

Duering, M. et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease-advances since 2013. Lancet Neurol. 22, 602–618 (2023).

Hu, H. Y. et al. White matter hyperintensities and risks of cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 36 prospective studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 120, 16–27 (2021).

Kloppenborg, R. P., Nederkoorn, P. J., Geerlings, M. I. & van den Berg, E. Presence and progression of white matter hyperintensities and cognition: a meta-analysis. Neurology 82, 2127–2138 (2014).

de Luca, A. & Biessels, G. J. Towards multicentre diffusion MRI studies in cerebral small vessel disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 93, 5 (2022).

Han, F. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of cerebral small vessel disease in a Chinese population-based sample. J. Stroke 20, 239–246 (2018).

Debette, S. et al. Association of MRI markers of vascular brain injury with incident stroke, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and mortality: the Framingham Offspring Study. Stroke 41, 600–606 (2010).

Ghaznawi, R., Geerlings, M. I., Jaarsma-Coes, M., Hendrikse, J. & de Bresser, J. Association of white matter hyperintensity markers on MRI and long-term risk of mortality and ischemic stroke: The SMART-MR Study. Neurology 96, e2172–e2183 (2021).

Prins, N. D. & Scheltens, P. White matter hyperintensities, cognitive impairment and dementia: an update. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 11, 157–165 (2015).

Dounavi, M. E. et al. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery magnetic resonance imaging textural features as sensitive markers of white matter damage in midlife adults. Brain Commun. 4, fcac116 (2022).

Zhu, W. et al. Dysfunctional architecture underlies white matter hyperintensities with and without cognitive impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 71, 461–476 (2019).

Chen, H. F. et al. Microstructural disruption of the right inferior fronto-occipital and inferior longitudinal fasciculus contributes to WMH-related cognitive impairment. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 26, 576–588 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Nodal global efficiency in front-parietal lobe mediated Periventricular White Matter Hyperintensity (PWMH)-related cognitive impairment. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11, 347 (2019).

Gillies, R. J., Kinahan, P. E. & Hricak, H. Radiomics: Images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology 278, 563–577 (2016).

Limkin, E. J. et al. Promises and challenges for the implementation of computational medical imaging (radiomics) in oncology. Ann. Oncol. 28, 1191–1206 (2017).

Tozer, D. J., Zeestraten, E., Lawrence, A. J., Barrick, T. R. & Markus, H. S. Texture Analysis of T1-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images detects abnormalities that correlate with cognitive decline in small vessel disease. Stroke 49, 1656–1661 (2018).

Zhao, K. et al. Independent and reproducible hippocampal radiomic biomarkers for multisite Alzheimer’s disease: diagnosis, longitudinal progress and biological basis. Sci. Bull. 65, 1103–1113 (2020).

Qiu, S. et al. Development and validation of an interpretable deep learning framework for Alzheimer’s disease classification. Brain 143, 1920–1933 (2020).

Won, S. Y. et al. Quality reporting of radiomics analysis in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: a roadmap for moving forward. Korean J. Radiol. 21, 1345–1354 (2020).

Van Griethuysen, J. J. et al. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res. 77, e104–e107 (2017).

van Gennip, A. C. E. et al. Associations of plasma NfL, GFAP, and t-tau with cerebral small vessel disease and incident dementia: longitudinal data of the AGES-Reykjavik Study. Geroscience; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-00888-1 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Cerebral small vessel disease: neuroimaging markers and clinical implication. J. Neurol. 266, 2347–2362 (2019).

Feng, J. et al. Automatic detection of cognitive impairment in patients with white matter hyperintensity and causal analysis of related factors using artificial intelligence of MRI. Comput. Biol. Med. 178, 108684 (2024).

Chen, Q. et al. A deep learning-based model for classification of different subtypes of subcortical vascular cognitive impairment with FLAIR. Front. Neurosci. 14, 557 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Classification of subcortical vascular cognitive impairment using single MRI sequence and deep learning convolutional neural networks. Front. Neurosci. 13, 627 (2019).

Liu, M. et al. Multiscale functional connectome abnormality predicts cognitive outcomes in subcortical ischemic vascular disease. Cereb. Cortex, https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhab507 (2022).

Zheng, X. et al. Deep learning radiomics can predict axillary lymph node status in early-stage breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 11, 1236 (2020).

Warkentin, M. T. et al. Radiomics analysis to predict pulmonary nodule malignancy using machine learning approaches. Thorax 79, 307-315 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. Deep learning Radiomics of shear wave elastography significantly improved diagnostic performance for assessing liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B: a prospective multicentre study. Gut 68, 729–741 (2019).

Ji, Y., Zhou, Z., Liu, H. & Davuluri, R. V. DNABERT: pre-trained Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers model for DNA-language in genome. Bioinformatics, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btab083 (2021).

Avsec, Ž. et al. Effective gene expression prediction from sequence by integrating long-range interactions. Nat. Methods 18, 1196–1203 (2021).

Clauwaert, J., Menschaert, G. & Waegeman, W. Explainability in transformer models for functional genomics. Brief. Bioinform. 22, bbab060 (2021).

Xie, Q. et al. Unsupervised domain adaptation for medical image segmentation by disentanglement learning and self-training. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 43, 4–14 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Deep learning-based unsupervised domain adaptation via a unified model for prostate lesion detection using multisite biparametric MRI datasets. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 6, e230521 (2024).

Ganin, Y. et al. Domain-adversarial training of neural networks. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 17, 2096–2030 (2016).

Tzeng, E., Hoffman, J., Saenko, K. & Darrell, T. Adversarial discriminative domain adaptation. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 7167–7176 (2017).

Maillard, P. et al. FLAIR and diffusion MRI signals are independent predictors of white matter hyperintensities. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 34, 54–61 (2013).

Gwo, C. Y., Zhu, D. C. & Zhang, R. Brain white matter hyperintensity lesion characterization in T(2) fluid-attenuated inversion recovery magnetic resonance images: shape, texture, and potential growth. Front. Neurosci. 13, 353 (2019).

Dufouil, C. et al. Severe cerebral white matter hyperintensities predict severe cognitive decline in patients with cerebrovascular disease history. Stroke 40, 2219–2221 (2009).

Huang, K. et al. A multipredictor model to predict the conversion of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease by using a predictive nomogram. Neuropsychopharmacology 45, 358–366 (2020).

Ter Telgte, A. et al. Cerebral small vessel disease: from a focal to a global perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 14, 387–398 (2018).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. 618–626 (2017).

Shao, Y., Ruan, J., Xu, Y., Shu, Z. & He, X. Comparing the performance of two radiomic models to predict progression and progression speed of white matter hyperintensities. Front. Neuroinform. 15, 789295 (2021).

Larue, R. et al. Influence of gray level discretization on radiomic feature stability for different CT scanners, tube currents and slice thicknesses: a comprehensive phantom study. Acta Oncol. 56, 1544–1553 (2017).

Huang, L. et al. Early Segmental white matter fascicle microstructural damage predicts the corresponding cognitive domain impairment in cerebral small vessel disease patients by automated fiber quantification. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 598242 (2020).

Hase, Y., Horsburgh, K., Ihara, M. & Kalaria, R. N. White matter degeneration in vascular and other ageing-related dementias. J. Neurochem. 144, 617–633 (2018).

Shao, Y. et al. Predicting the development of normal-appearing white matter with radiomics in the aging brain: a longitudinal clinical study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10, 393 (2018).

Baessler, B. et al. Cardiac MRI and texture analysis of myocardial T1 and T2 maps in myocarditis with acute versus chronic symptoms of heart failure. Radiology 292, 608–617 (2019).

Magnuska, Z. A. et al. Influence of the computer-aided decision support system design on ultrasound-based breast cancer classification. Cancers 14, 277 (2022).

Biesbroek, J. M., Weaver, N. A. & Biessels, G. J. Lesion location and cognitive impact of cerebral small vessel disease. Clin. Sci.131, 715–728 (2017).

Low, A., Mak, E., Rowe, J. B., Markus, H. S. & O’Brien, J. T. Inflammation and cerebral small vessel disease: A systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 53, 100916 (2019).

Hatamizadeh, A. et al. UNETR: Transformers for 3D medical image segmentation. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 574–584 (2022).

Dufouil, C., Alpérovitch, A. & Tzourio, C. Influence of education on the relationship between white matter lesions and cognition. Neurology 60, 831–836 (2003).

Luo, C. et al. White matter microstructural damage as an early sign of subjective cognitive decline. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11, 378 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82130036 [Y.X.], 81920108017 [Y.X.], 62476122 [L.K.H], 62106101 [L.K.H]), the STI2030-Major Projects (2022ZD0211800 [Y.X.]), Jiangsu Provincial Medical Key Discipline (ZDXK202216 [Y.X.]), Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project (2023ZD0504902 [L.X.Z]), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20210180 [L.K.H]). We acknowledge Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital Biobank of Jiangsu Provincial Science and Technology Resources (Clinical Resources) Coordination Service Platform. We gratefully acknowledge all participants and patients involved in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X., K.H. and M.L. contributed to the conception and design of the work, took responsibility for the integrity of the data and analysis as co-corresponding authors. L.H., Z.L., X.Z. contributed equally as co-first authors. L.H. and Z.L. collected, cleaned the data and verified the quality of the data. L.H., Z.L., X.Z. analyzed the data, constructed deep learning and machine learning models, and drafted the original manuscript. H.Z., C.M., Z.K., Y.M. and D.Y. contributed to the acquisition and preprocessing of imaging data. Dr. Yue Cheng contributed to the analysis of data. R.Q., Z.H., P.S. and Dr. Ying Chen contributed to the acquisition of imaging and clinical data. Y.X., K.H. and M.L. contributed to the interpretation of data and revised the manuscript. All authors critically read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, L., Li, Z., Zhu, X. et al. Deep adaptive learning predicts and diagnoses CSVD-related cognitive decline using radiomics from T2-FLAIR: a multi-centre study. npj Digit. Med. 8, 444 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01813-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01813-w