Abstract

Online health communities (OHCs) enhance personalized care by connecting patients, professionals and leveraging patient-reported outcomes. This study investigates how communication elements (emotions, patient-generated topics, appeals, and linguistic style) affect patient awareness (click-through-rate) and engagement (average engagement time and community subscriptions) in an atrial fibrillation (AF) OHC. A quasi-randomized online field experiment targeted Dutch adults via Facebook and Instagram with 12 communication concepts, directing them to the AF OHC. From May to June 2023, 795,812 users were reached, generating 18,426 visits, 478 subscriptions, and an average engagement time of 35 s. Communication elements significantly influenced awareness and engagement, with emotions and topics as strongest predictors. Fear was most effective for self-protection topics, love for affiliation and kin care. Expert appeals increased awareness, while testimonials boosted engagement. These findings offer novel insights into the role of communication strategies across patient journey stages, aiding health managers in optimizing patient engagement and OHC impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The health care landscape significantly changed over the past years through disruptive health instances entering the market, such as AI-driven robotic providers, patient influencers and medical technology companies1. Another emerging actor within the health care field is the online health community (OHC). OHCs facilitate connections among patients, physicians, hospitals, and other elements of the medical ecosystem via the internet2. They serve as dedicated platforms for information exchange between patients and physicians. OHCs are online platforms that fill needs of patients by offering peer-to-peer support, information on latest studies of a particular condition and ‘lived experiences’, which are often unfulfilled by traditional health care services3,4.

One area where patient platforms have shown significant promise is in the management of atrial fibrillation (AF), the most common cardiac arrhythmia that is lifestyle related and affects millions of people in the Western world5. Patient platforms for AF serve as online communities specifically tailored to the needs of individuals living with this condition. These platforms provide a range of valuable resources and support mechanisms that go beyond what traditional health care services can offer. Patients can connect with others who share similar experiences, providing an avenue for peer-to-peer support, understanding, and solidarity. This sense of community can be particularly beneficial for individuals with AF, as it helps combat feelings of isolation and empowers patients to actively participate in their own care. These platforms also serve as a hub for the latest research and studies related to AF. Patients can access information on advancements in treatment options, medications, and lifestyle modifications that can help manage their condition effectively. By staying informed about the latest developments, patients can engage in more informed discussions with their health care providers and make confident decisions regarding their treatment plans. The decision to study AF within the context of OHCs is because AF is highly prevalent, progressive, and episodic condition often associated with Western lifestyle-related co-morbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, and obesity6. Therefore, AF (self-)management via OHCs offer a promising avenue to support patient engagement and education and may play a critical role of co-morbidity identification and management in improving outcomes. Despite its widespread impact, awareness and understanding of AF remain suboptimal, making targeted, scalable communication especially important. Additionally, AF patients tend to be digitally engaged and often use wearable devices and tracking tools, making them an ideal group for studying real-world digital health communication7. The AFIP Foundation, a leading Dutch OHC established in 2016, provided a strong foundation for our research due to its active patient engagement, integration in the CIRCULAR consortium, and commitment to citizen science. This made it a uniquely relevant setting to investigate communication strategies that can enhance awareness and participation in OHCs. Furthermore, patient-reported outcome and experience measures (PROMs and PREMs)8 play a crucial role in the realm of AF5. PROMs and PREMs capture patient experiences and outcomes on well-being and care directly from the individuals themselves, rather than relying solely on clinical assessments. This patient-centered and citizen science-based approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of AF on individuals’ quality of life, but also helps researchers to develop tailored treatment plans accordingly. For instance, some patients may benefit from adopting a whole-food plant-based diet or rebalancing their electrolyte levels9. Although PROMS and PREMS originally are conducted in hospitals, clinics, or outpatient centers, the upcoming popularity of OHCs presents a new opportunity for collecting these insights, offering advantages such as increased availability, reduced costs, and greater data quantity. As such, OHCs enable a unique opportunity to personalize care that aligns with individual needs, ultimately improving patient health outcomes and satisfaction.

OHCs, like the AFIP foundation, do not gain traction instantly. Strategic communication directed towards stakeholders is crucial for individuals to participate in citizen science and patient-researcher collaboration. However, OHCs still face significant challenges related to low involvement and the quality of patient contributions10. Although scholars, in the field of OHCs, have studied patient opinions, interests, and the drivers of OHC adoption, acceptance, and motivation2,11,12, there is still a lack of empirical findings on how to attract and engage audiences in OHCs. In contrast, traditional health institutions such as hospitals, health centers, and pharmaceutical companies have increasingly invested in health marketing and communication, highlighting their growing importance in the health sector. As a result, direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertisement spending showed a steep increase from $542 million in 1997 to $2.9 billion in 201613. Previous studies have explored various communication approaches that could potentially influence behavior of individuals in and outside of health contexts. Especially the effect of positive (e.g., hopeful, loving)14,15,16,17 and negative (e.g., anger, fear) emotions14,16,17,18,19,20,21, message narratives and appeal18,22,23,24,25, and linguistic style18,26,27 on behavior of individuals received attention among scholars. However, the diverse outcomes of many of these studies make it difficult to identify consistent theoretical and practical implications on which health communication drives desired health behavior, and raises the question whether findings are applicable within the field of new health care actors, like OHCs. More importantly, despite ongoing efforts, outcomes only remain partially understood1.

Additionally, most previously studied communication variables, like emotion, source narrative, and linguistic style14,22,28 in isolation typically through survey or lab-based settings despite in real-life practices they are used in combination interacting with each other (e.g., Carey & Sarma20 found that fear in combination with self-efficacy was successful in reducing male’s driving speed, while fear alone did not seem to have an effect). Given the limited evidence on how communication variables interact in real-world online health campaigns, this study aims to answer the following questions:

-

1.

What is the effect of different communication variables (drawn from previous work) on awareness (click-through-rate) and engagement (average engagement time and community subscriptions) outcomes?

-

2.

Which individual communication elements (i.e., emotion, topic, appeal, or linguistic style) significantly influence awareness (click-through-rate) and engagement (average engagement time and community subscriptions) when modeled alongside other communication and control variables, and what is the relative impact of each element compared to each other?

-

3.

Are there interaction effects between communication variables (e.g., emotion and topic) that amplify or suppress awareness (click-through-rate) and engagement (average engagement time and community subscriptions outcomes? In practice this means: which combinations (of elements) in OHC communication would bring use the best engagement outcomes?

We conducted a quasi-randomized online field experiment using 12 communication concepts among a large Dutch population. In line with the approach of Lee et al.29, communication variables were selected from the literature with relevance to the health context of this study, namely AF (see the Methodology section for the full literature review and the description of the communication variables used in this study). The selected combinations were not arbitrarily chosen, rather, they were discussed and refined with a team of cardiologists and researchers within the CIRCULAR consortium and communication experts from an in kind contributing digital marketing agency to ensure that they reflected realistic, meaningful, and relevant messages within the AF context. See Fig. 1 for the communication variables used in this study. The online field experiment was conducted in two phases. In the first phase we used the Facebook and Instagram accounts of an OHC on AF (AF OHC) to collect awareness data (click-through rate, CTR)30 as these channels have been shown to be effective in raising awareness of health issues30,31,32. In this phase we reached 795,812 unique users. In the second phase, we measured the online behavior of visitors who entered through the first phase to gather engagement data (average time on site and community subscriptions) on the landing pages of the AF OHC website.

We investigated the influence of different emotions, patient-generated topics, appeals, and linguistic styles, as well as their combined effects with each other on both awareness and engagement. Online field experiments are one of the most efficient and accurate methods to collect real-time data with validity by incorporating real communication concepts and a real OHC33. With this in mind, we were able to analyze online clicks and website behavior of users. We built models using different multivariate regression methods, while controlling for time, device usage, demographics (i.e., age and gender), platform (i.e., Facebook and Instagram), and ad exposure frequency along with running robustness checks.

The findings of our online field experiment show that the ability of health campaigns to raise awareness and patient engagement largely depends on the interaction between emotions and the topics used in the communication. Additionally, this study provides valuable guidance for managers of health organizations aiming to grow their OHCs and in turn increase their impact on personalized health care. The insights enable strategic communication decisions to effectively reach and engage their target audience at specific stages of the patient journey.

Results

Communication concept performance

In total, 420,427 (52.9%) males, 374,227 (47.0%) females, and 1158 (0.1%) unknown (self-reported) users, of which the majority (65.4%) was 55 years or older, were reached on Facebook and Instagram between May 23, 2023, and June 23, 2023. Moreover, the communication concepts reached 795,812 users, with the website landing pages receiving 18,426 visitors. Every website landing page had at least N = 1000, with maximum N = 2787 and minimum N = 1043. The visitor distribution over the landing pages is presented in Supplementary Fig. 2. The average CTR of the communication concepts is 0.87% (SD = 3.01), which is slightly higher than the health industry average of 0.83%34 and in total 478 individuals subscribed to the OHC. On average, individuals spent 36 s (SD = 77.5) browsing the OHC (Table 1).

In addition to average engagement time and community subscriptions, we examined the ‘engaged session’ metric which is defined as “a session that meets any of the following criteria: lasts longer than 10 seconds, has a key event, as 2 or more screen or page views” (Google, 2025, https://support.google.com/analytics/answer/12195621). This binary metric offers insight into user activity and retention on the OHC platform. Across all website visits 37% (SD = 0.48) of the sessions were engaged. Considering that bounce rate is defined as the exact opposite of an engaged session, the amount of users that did not interact with the OHC is 63% which is in line with the benchmark of 60%–90% for campaign landing pages (CXL, 2025, https://cxl.com/guides/bounce-rate/benchmarks/).

Results on engagement outcomes

As previously stated, to ensure robustness, several models were developed with varying control variables and interactions. All regression models exhibited relatively low R² values, ranging from 0.02 to 0.05. Given the large sample size, the context of predicting human behavior, and the online field experiment setting, these figures are unsurprising and still deemed acceptable. With that said, the linear regression highlights the impact of the communication concepts on average engagement time which all show significant effects (see Table 2). Among the topics, kin care emerged as the most influential, leading to an average engagement time increase of 51 s compared to concepts involving self-protection (CI[45.23, 57.48], p < 0.001). Conversely, persuasive appeal has the most substantial negative effect, reducing engagement time by 16 s (CI[-18.96, -13.49], p < 0.001) compared to informative appeal. Another strong predictor of average engagement time is emotion, with fear resulting in 46 s (CI[39.85, 51.93], p < 0.001) more average engagement time than love. Moreover, from the control variables desktop as device also significantly influences engagement time, with desktop users viewing the website 21 s longer than mobile users (CI[14.13, 27.75], p < 0.001). Furthermore, plausible interactions between the main variables within our context were tested. As such, the interaction between the strongest predictors (i.e., emotion and topic) were further analyzed. While the emotion fear alone yields 33 s higher average engagement time than when the emotion love is present, the use of fear in combination with the topics kin care and affiliation results in a decrease of average engagement time. When combined with fear, the average engagement time of affiliation and kin care decreases with affiliation resulting in 50 s less and kin care 46 s less respectively. Overall, the linear regression results indicate that the topics are the strongest predictors of average engagement time, while this effect is also dependent on emotion. The emotion fear seems to result in higher engagement time when combined with the topic self-protection instead of the topics kin care and affiliation.

Next, logistic regression models were performed to investigate the effects of the communication elements on the community subscriptions on the platform (see Table 3). All communication elements significantly influence community subscriptions, except for the persuasive vs. informational appeal. Like the model results of average engagement time, the topic of the communication concept is shown to be the strongest predictor of community subscriptions, with affiliation being 6.36 times (CI[3.40, 11.89], p < 0.001) more likely to result in community subscriptions compared to when the topic self-protection is used. The third-person linguistic style negatively affects community subscriptions and is 0.65 times (CI[0.53, 0.79], p < 0.001) less likely to result in community subscriptions compared to a first-person linguistic style, showing that a general tone in communication is less favorable than a personal story to generate subscriptions. Moreover, the odds of testimonial appeal resulting in community subscriptions is 1.38 times (CI[1.09, 1.76], p < 0.01) more than when the expert appeal is used. Considering the control variables, none of these has a significant impact on community subscriptions. However, like in the previous model, the topics do not yield the same positive impact on community subscriptions when combined with the emotion fear. In fact, the odds of affiliation resulting in community subscriptions is 0.16 times (CI[0.07, 0.35], p < 0.001) less than when combined with the emotion fear. For kin care the odds are 0.28 less (CI[0.13, 0.57], p < 0.001). Just like for average engagement time, fear yields the best results in community subscriptions when combined with the topic self-protection.

Results on awareness outcomes

Supportive models were specified and employed to analyze the effects of content elements on CTR, accounting for demographic, device, platform, and frequency variables (see Table 4). These models aimed to determine if the engagement model results also apply in the awareness context. Results showed that emotion, topic, and, appeal (testimonial vs. expert) significantly influenced CTR. Fear led to a 0.65% higher CTR than love (CI[0.45, 0.85], p < 0.001). While kin care and affiliation positively impacted average engagement time and community subscriptions, they reduced CTR on Facebook and Instagram. Affiliation led to a 0.93% lower CTR (CI[-1.19, -0.68], p < 0.001) than self-protection, and kin care resulted in a 0.78% decrease in CTR (CI[-1.00, -0.57]). Individuals of 65 years and older had a 0.59% higher CTR (CI[0.35, 0.83], p < 0.001) than the other age groups, and females as well as unknown genders had 0.32% (CI[-0.35, 0.83], p < 0.001) and 0.60% (CI[-0.35, 0.83], p < 0.001) higher CTRs, respectively, than males. The second model affirmed emotion and topic effects, while both appeals (i.e., testimonial vs. expert and informative vs. persuasive) were nonsignificant. Third-person linguistic style led to a 0.25% higher CTR. Instagram performed poorer than Facebook, and like Android tablets, iPads had higher CTRs, while desktop users had lower CTRs compared to Android smartphones. iPods, iPhones, and others were insignificant.

Discussion

We conducted a quasi-randomized online field experiment with the aim to investigate the individual and combined effects of the communication elements emotion, topics, appeal, and linguistic style on awareness (CTR) and engagement (average engagement time and community subscriptions) of AF patients in the setting of an OHC. The online field experiment, consisting of 12 communication concepts, was conducted from May 23 to June 23, 2023, on Facebook and Instagram in the Netherlands, reaching 795,812 users to measure awareness effects. Of these users, 18,426 visited the website of an AF OHC where their engagement with the OHC was measured. Results reveal that CTR, average engagement time, and community subscriptions are significantly affected by the communication elements used in this study, with emotions and topics producing the largest impact on patients’ awareness and engagement. Our study uncovers new findings, showing that the effectiveness of an emotion depends on the topic it accompanies. In both the awareness and engagement phases, fear works best when paired with self-protection, while love is most effective with affiliation and kin care topics. Additionally, expert narrative appeals perform better in the awareness phase, whereas testimonials are more effective for OHC engagement.

The findings regarding fear are consistent with previous work showing that fear stimuli activate attention and protection behavior19,21,32,35. For instance, one study found that besides hope, fear effectively led to immediate behavioral change of individuals when it comes to hygienic measures, local restaurant visits and conscious consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic19. Moreover, a large meta-analysis on health communication found that fear was effective in stimulating health behavior of audiences that are low involved in particular disease contexts18. Since our communication concepts were targeted at everyone above 18 years, the possibility of low involved audience inclusion arises and may have enhanced the effectiveness of fear appraisals in the communication concepts. Moreover, the emotion fear resulted in a higher CTR and engagement time than the emotion love, which is aligned with our expectations as recent studies found that fear increases attention of individuals17.

As mentioned, topics strongly influence CTR, average engagement time and community subscriptions as well. The results of our study uncover that especially the topics affiliation and kin care perform better than the topic self-protection in enhancing engagement of individuals. A possible explanation can be that elderly people, who are mostly the ones suffering from AF, are more inclined to be relationship seeking instead of information seeking36. Also, during the COVID-19 pandemic adults showed to be more willing to take a vaccine after being exposed to family-oriented messaging instead of threatful messages which may explain why kin care as a topic performed well for engagement37. However, the topic self-protection outperformed affiliation and kin care in CTR which indicates individuals are more inclined to respond to messages related to self-protection in the awareness phase. Considering that other peers in the health communication field found that message identification result in positive health attitudes38, one possible explanation for our findings is that individuals in our sample who are not diagnosed with AF are perhaps less able to identify with the topics affiliation and kin care potentially influencing CTR.

Another important finding is the interaction effect between emotions and topics. In all our models, the combination of the emotion fear and the topics affiliation and kin care yield negative results when considering CTR, average engagement time, and community subscriptions. This means that the emotion fear is most powerful when combined with the topic self-protection. The emotion love, on the other hand, enhances the positive effects of affiliation and kin care. Mixed findings on the use of emotions (love vs. fear) were presented in earlier work and our results demonstrate that the effectiveness of emotion is dependent on the topic portrayed in the communication context. Depending on the objectives of health instances, the emotion fear may be combined with the topic self-protection to attract awareness. However, when aiming for engagement, the emotion love should be combined with topics such as affiliation and kin care. More research is needed to investigate the effect of using both emotions (e.g., showing fear in messages on social media channels and using love on the concept landing page) in different phases of the patient journey and whether the effectiveness holds throughout a long-term OHC and patient relationship.

Furthermore, personal stories from patients (testimonials) performed better in generating engagement in terms of average engagement time and community subscriptions, while our supportive model showed that expert stories generated higher CTR. This result indicates that individuals are more inclined to navigate to an OHC when an expert message is shown, but directly act upon the message through active engagement when being exposed to patient messages. A possible explanation for this finding is that source credibility may improve response efficacy of an audience that is low involved in a certain health field, while this effect is less strong for a highly involved audience18. Moreover, research suggests that older adults experience increased self-efficacy, which is an important factor linked to improved health related outcome expectations, when they observe their peers successfully using mobile health services39. This could help explain why patient testimonials often lead to better engagement outcomes compared to the expert appeal.

Additionally, a first-person linguistic style was found to be more effective than a third-person linguistic style in driving engagement which is consistent with previous work showing that a first-person narrative makes a message compelling27. Linguistic style did not seem to have a significant effect on awareness when controlling for demographic characteristics of individuals. However, a third-person linguistic style positively influenced CTR while controlling for device characteristics. While some studies have shown that a first-person narrative enables the transmission ability and identification of individuals in a story which may perform better in the general public27 and that general third-person messages are more effective in high involved audiences18, there has also been a recent online field experiment on work-related stress which did not find a significant of first-person or third-person linguistic style on attitude towards stress-prevention strategies38. The authors argue that potentially the first-person or third-person linguistic style may not be as influential as characteristics similarities between individuals and the life situations depicted in messages. Our results confirm that the third-person or first-person linguistic style are less influential on awareness and engagement than other communication features such as emotion, topics, or testimonial vs. expert appeal.

Importantly, although this study was conducted within the context of AF, its objectives, methodology, and findings are relevant to a wider range of chronic disease focused OHCs as these audiences share similar needs (i.e., to feel whole as a person with valid experiences, (2) to receive information on how to live with the disease, (3) to connect with others that experience the same, and (4) to feel supported on the long-term)40. Many OHCs share similar challenges in promoting engagement and behavior change10 and we offer a replicable framework for testing communication strategies using real-world platform data. By aligning content with three of the fundamental human motives (i.e., self-protection, affiliation, and kin care) as outlined by Griskevicius & Kenrick35 the study provides insights that may generalize across conditions such as diabetes, neurodegenerative and other cardiovascular diseases. However, as motivational priorities vary across cultural and demographic groups41, the effect sizes of the communication variables on awareness and engagement metrics may differ accordingly. We therefore recommend future research to replicate and adapt this approach across diverse chronic illness communities, tailoring content to the dominant motivational profiles of their populations and validating message perception through pre-testing.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, it is necessary to acknowledge that additional factors beyond the scope of our study, such as the physical location of ad exposure or an individual’s mood, may have influenced the proportion of the variance of our experiment outcomes. The context in which individuals encounter health-related advertisements on social media platforms is inherently variable and may influence user behavior. Situational factors such as time of day, scrolling context, current activity, and transient mood states can all affect how users interpret and engage with content42,43,44. Although these contextual variables could not be directly measured in our field experiment, we attempted to partially mitigate their impact by distributing the message delivery across different time windows (i.e., work hours vs. non-work hours; morning, afternoon, and evening; and weekdays vs. weekend days) and control for device type (i.e., desktop, mobile, and tablet), thereby reducing potential time-of-day and device effects. To control for demographic variance in the awareness stage, we included device type, gender, and age as control variables in our analysis to account for structural demographic differences. Our campaign targeting strategy also stratified messages across gender and age groups to improve representation. Despite these precautions, we acknowledge that other unobserved variables, such as participants’ digital and health literacy, may have influenced behavior. Although our large sample size helps reduce the impact of such biases, it does not eliminate them entirely. We therefore interpret our findings with caution, recognizing the strengths and limitations of real-world online field experiments. While such designs enhance ecological validity, they inherently involve variability that may both enrich and complicate the interpretation of behavioral responses. Future studies could combine field-based experimentation with controlled lab studies to more precisely isolate the psychological mechanisms underlying message effectiveness in OHC engagement. Secondly, there is a likelihood that proactive participants with high health or digital literacy were primarily reached, potentially excluding vulnerable populations. Future research should consider experimenting with different levels of digital and health literacy by conducting experiments using different (online or offline) platforms, other message formats (e.g., videos or audio), and diverse baseline knowledge levels in the messaging. Thirdly, we followed a quasi-randomized experiment design. While this design enhances ecological validity, it inherently limits the strength of causal claims that can be made. As such, observed effects should be interpreted as indicative of real-world applicability rather than definitive evidence of theoretical mechanisms. Future researchers may build on these insights by testing the combined influence of communication variables in controlled laboratory environments to strengthen causal inference.

Methodology

Literature review

An overview of the literature is first provided to define the communication variables, before detailing the design of the online field experiment with its multiple communication concept variations. The review begins with an exploration of developments within OHCs, followed by insights from health and marketing communication literature. It then covers empirical work on the influence of emotions, topics, appeal, and linguistic style on (health) behavior. This comprehensive literature review served as the foundation for the development of the communication concepts and the design of the concept landing pages. Table 5 provides a summary of the literature review, outlining the communication elements and patient journey stages that informed the experimental setup.

Digital healthcare platforms & communities

OHCs are considered as “a special type of online social network in which members interact in health- or wellness-related virtual communities to seek information, help, emotional support, and communication opportunities”12. OHCs fulfill demands of health consumers who are unable to obtain all information they need from traditional health care providers. Health consumers typically aim to find peer-to-peer support, trustworthy information on advances within a specific health field or companions with “lived experience” of a particular health condition and its treatments. Platforms such as My Health Team offer chronically ill individuals social networks where they can interact with other companions on disease symptoms, management, and treatment while also learning more about their condition through availability of trusted information. Other than traditional communication lines, which include doctor-patient-interactions, direct-to-consumer marketing, and hospital-to-consumer marketing, patients nowadays interact with companions, caregivers, and other professionals directly1. This results in new information streams of which peer-to-peer influence (e.g., patients Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM)) and patient co-creation (e.g., patient and hospital collaboration on treatment processes) are common examples. Especially the latter may result in valuable outcomes as patients contribute to health service innovation and participate in research. A study done by Hodgkin et al.3 highlighted four ways OHCs create value, namely by (1) offering patients and caregivers new resources in the form of support, information, and solidarity, (2) providing non-patients with new insights, (3) challenging power dynamics between patients and health professionals, and (4) growing knowledge through data collection. Patients nowadays are more empowered, potentially offering incredible value to the health field when utilized correctly by all stakeholders involved.

Marketing and communication in digital health care management

Starting an OHC can be challenging, and these platforms have not been widely adopted yet2. As such, previous studies brought insights into which factors drive participation of members. The role of platform values and characteristics in platform adoption and engagement have priorly been investigated in particular. Multiple studies found that social support, relationship commitment, and an ethical and trusting environment are crucial for OHCs to grow engaging communities and produce value10,45,46. Unlike research on value creation and quantification of OHCs, knowledge on OHC marketing and communication approaches is less developed. Besides one study showing that Facebook is an effective platform for OHC membership promotion31 and another study which demonstrated that fear can result in perceived threat and may evoke cyberchondria, while coping appeals resulted in higher efficacy and impulsive purchasing behavior in OHCs47, research on marketing and communication approaches for OHC promotion remains scarce. Thus far, research in health marketing and communication is specifically fixated on business-to-business (B2B) and DTC advertising strategies1. More importantly, as previously mentioned, these practices are only partially understood. Existing work has incorporated multiple marketing and communication angles that potentially influence health attention behavior in the field of DTC. A widely studied segment is the influence of emotion on health behavior15,17,18,19,20,21,48, showing varying results. For instance, Carey & Sarma20, show that fearful and efficacy messages can positively affect driving behavior, while others found that loving and coping content activated individuals in charity and OHC purchasing contexts47,48. Besides, Kim et al.19 show that both love and fear inducing messages can benefit health behavior. Like in the field of emotion and health behavior, contradicting findings have been found in other marketing and communication fields as well. For example, message narratives have been studied in the form of information source narratives, such as expert statements versus patient or celebrity statements18,22,23,28. Keller & Lehmann18 conclude from their meta-analysis that patient testimonials stimulate health behavior while Hsu23 and Jebarajakirthy et al.28 found that the expert narrative positively influenced health behavior. However, Emmers-Sommer & Téran22 found that individuals tend to respond better to celebrity endorsements. Additionally, multiple authors have investigated the role of narratives within linguistic style and message appeal and also show different findings15,18,20,24,27,48,49,50. Carey & Sarma20 found that persuasive messages positively influence driving behavior, especially in the short term. However, Lütjens et al.50 uncovered that informative messages positively impact the attitude towards online advertising. Mixed findings were found in linguistic features on health behavior too. Chen & Bell27 state that a first-person linguistic narrative enhances the persuasiveness of a health message, however, their meta-analysis showed that this did not necessarily result in desired health behavior of the participants. Besides, Keller & Lehmann18 concluded that directly targeted messaging may yield positive health behavior outcomes in low involvement audiences, but that general messages were more effective in high involved audiences. These studies show different effects of communication variables on health behavior for diverse audiences which results in varying outcomes and recommendations. These outcomes make it challenging for health communication managers to choose appropriate marketing and communication strategies in practice.

It has become evident that previous work in the field of marketing and communication in OHCs is limited. Additionally, many studies rely on surveys, making it difficult to measure human behavior across various customer journey phases, such as impression and click behavior in the awareness phase, average time on page or sign-ups in the engagement phase, or information sharing and return rate in the activation and loyalty phase. Another crucial aspect missing is the consideration of the underlying evolutionary motives driving our behavior. Griskevicius & Kenrick35 outlined seven fundamental motives that underlie all human behavior, which may help to understand how these motives influence health behavior and inform marketing and communication strategies for OHC promotion. Moreover, previous research has primarily examined marketing and communication elements in isolation. Health marketers and managers could benefit from understanding the combined effects of these elements to create a greater impact in the field. Therefore, comprehending how these elements raise awareness of OHCs and drive engagement on the platforms can provide insights into when and how they are most effective.

Conceptual framework & components of the model

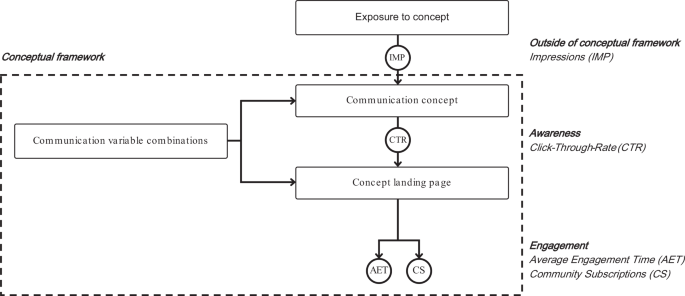

Before further elaborating on the marketing and communication elements that we include in our online field research, we first shed light our conceptual model. We investigate the influence of marketing and communication elements on patient’s awareness (i.e., CTR) of the OHC that is included in our study. Moreover, we investigate the effect of these communication elements on the engagement (i.e., community subscriptions and average engagement time) of patients in the OHC on AF.

Based on the existing literature, communication variables represent opposites of one another. For emotion, love and fear are included as these emotions are prominently studied. Additionally, considering that self-protection, affiliation, and kin care as evolutionary motives for human behavior are relevant to OHC, these have been selected into the framework. For message appeal we compare patient narratives (i.e., testimonial) against expert narratives and informative messaging against persuasive messaging. Finally, we include linguistic style in which we compare a first-person narrative with a third-person narrative.

It’s important to draw attention to the control variables of this field experiment. Considering the nature of our data and context, we include moments in time, device category, demographics (i.e., age and gender), platform (i.e., Facebook and Instagram), and ad exposure frequency as control variables in our framework.

Model components

Prior research in health marketing and communication primarily focuses on emotional appeals and diverse message framing strategies. These elements are defined before reviewing the literature on the specific marketing and communication components.

First of all, emotion can be described as “valenced responses to relevant stimuli that are directed toward specific targets (e.g., people, objects, or events), differentiated, and relatively short-lasting”51. Within the health marketing field, emotion has especially been applied to generate threatful, fearful or on the contrary, hopeful, coping, and loving messages. Second, message appeal is defined as the type of request conveyed by a message. In this study, expert and patient (i.e., testimonial) narratives are employed to communicate informational as well as persuasive appeals. Finally, we include linguistic style in our model which can be distinguished between linguistic content (i.e., nouns, verbs, adjectives that carry the content of a communication) and linguistic style (i.e., prepositions, conjunctions, auxiliary verbs which represent sentential meaning and style)52. Since the study centers on first-person and third-person communication perspectives, the emphasis is placed on the linguistic content rather than the stylistic features of language.

Fundamental motives of human behavior

The inclusion of the evolutionary human motives in the field of health behavior is relatively new and findings are scarce. Graham & Martin53 stress that studies on the effect of marketing communication variables on health behavior only partly explain why behavior occurs as in reality health behavior is often sudden, unexpected, and non-linear. Therefore, little is known about how marketing communication influence behavior. To improve our understanding of drivers of health behavior, we must consider the underlying motives for human motivations. Maslow’s classic hierarchy of needs that originally consists of (1) immediate physiological needs, (2) safety, (3) love, (4) esteem, and (5) self-actualization was modified by Kenrick et al.54 based on developments in the field of evolutionary biology, psychology, and anthropology which showed that mating and reproduction influence our motivation. Their updated hierarchy of fundamental human motives include (1) immediate physiological needs (self-protection), (2) self-protection (disease avoidance), (3) affiliation, (4) status/esteem, (5) mate acquisition, (6) mate retention, and (7) parenting (kin care).

Prior to elaborating on the activation cues underlying human behavior, it should be acknowledged that not all fundamental human motives are directly applicable to the context of OHCs. For example, individuals that are motivated by status, which is characterized by seeking products to signal prestige, will most likely not sign up to OHCs to fulfill this need. As a result, the motives and concerns of patients with AF were analyzed to refine and select the most relevant fundamental motives for inclusion in this study (see Supplementary Reference 1). The majority of outcomes are directly in line with self-protection, affiliation, and kin care. Patients specifically mention that they are concerned with their heath and therefore seek to understand how to live with AF, which fits the motive of self-protection. Some others find it important to share thoughts and experiences with other patients and want a feeling of belonging, which fits with affiliation. Finally, there is also a group that state that AF interferes with family care and that they are concerned their children may develop AF as well, which fits with kin care. Therefore self-protection, affiliation, and kin care have been included in this study's framework as patient-generated topics.

Each evolutionary motive can be activated through triggers and will result in specific behavior. Griskevicius & Kenrick35 reviewed the triggers, behavioral outcomes, and cues that activate fundamental motives and their associated behavioral tendencies. Overall, they found that self-protection (i.e., avoiding danger) is triggered by angry faces, darkness or loud noises, and threatening persons. Self-protection results in ‘increased tendency to conform’, ‘decreased risk-seeking’, and ‘increased aversion to losses’. Affiliation is activated by friendship-related threats or opportunities, leading to behaviors such as seeking socially connective products, relying on word-of-mouth, and consulting reviews for others’ opinions. Finally, kin care is triggered by visualization of family or vulnerable others and results ‘increased trust of others’, ‘increased nurturance’, and ‘increased giving without expectation of reciprocation’.

As briefly mentioned before, the implementation of evolutionary fundamental motives of human behavior (besides disease avoidance) in health behavior research remains scarce. Besides Okuhara et al.37 that demonstrated that kin care motives are just as effective as disease avoidance motives in generating a positive attitude towards the COVID-19 vaccine in Japan, studies on fundamental human motives in combination with other marketing communication elements are lacking.

Emotions: love and fear

Within the extant literature, the concepts of love and hope have been used within different contexts. Within the domain of marketing research, the term ‘love’ has been described as ‘emotions of compassion and desire’15. Just like Cavanaugh et al.15, this study does not address the emotion of love as romance. Instead, love encompasses fondness and genuine care for oneself as well as important individuals in one’s life (e.g., caregivers, family or friends).This study frames the emotion ‘love’ positively, based on evidence that positive emotional content increases message virality16,55 and attention of individuals17. Love is paired with hope in this study to make love a positive emotion. Hope is often defined as the anticipation of a favorable outcome in the future, providing a sense of motivation that one’s efforts can yield positive results and can shape how both individuals and others perceive hurdles56. Besides, Wrobleski & Snyder36 researched the role of hope and health outcomes in elderly people. One of their findings indicates that individuals with high levels of hope exhibit greater self-efficacy (defined as confidence in achieving goals) and show more engagement throughout the goal pursuit process compared to those with lower levels of hope.

Another commonly studied field within the health marketing literature is the emotion fear. Back in the 1950s, the belief was that fear evoking campaigns would result in desired health behavior of individuals57. Later, in the 1960s, researchers found inconsistent findings on the use of threat-appeal on health behavior which drove Higbee’s57 attempt to investigate variables that may interact with fear to make it less or more effective in health communication. Some of his findings show that (1) threat is superior to low threat in persuasion, (2) the specificness and ease of implementation of recommendations increases the effectiveness of fear, even more so than for efficacy, and (3) responses of fear differ among individuals where individuals with chronic anxiety seem to respond best to fear framing. The author also stresses that evidence on interest in fear messaging was inconsistent. Recent studies shed more light on the effectiveness of fear as the digitalization of content and health advertisements allowed academics to investigate online behavior after exposure with fearful messaging. Forbes et al.21 demonstrated in their fearful animal imaging experiment that fear triggers fundamental human instincts and facilitates rapid processing with minimal stimulus information which raises attention. In a recent study by Berger et al.17 the same effect was witnessed. The authors showed that anxiety, but also hope and excitement capture attention. Moreover, these results also seem to be valid in the virality of messages as both positive and negative laden messages seem to increase virality of a message16,55,58. Many findings on health behavior of individuals after health message exposure are in line with previous findings from Higbee57. For instance, Carey & Sarma20 found that fear in combination with efficacy in messaging significantly lowers driving speed of young male drivers. However, fear alone did not make an impact. Later, Ort & Fahr48 found similar results and confirmed that threat alone did not influence health behavior towards Ebola vaccination and that efficacy must be used in combination with threat to affect an individual’s attitude towards the vaccine. Fu et al.47, investigated the dynamics which determine success and failure of fearful messages and found that fearful messaging can result in cyberchondria. This means that individuals exposed to threatful content, may psychologically distance themselves from the message sender which may result in undesired health behavior. Both love and fear can result in either PFC or EFC coping strategies47. Where a PFC approach results in problem solving and an individual taking direct action, the EFC approach holds the opposite and makes threats perceived as less severe which in turn results in psychological distancing, wishful thinking, and denial. Considering the previous work on the emotion love and fear, it is expected that both the emotions of love and fear can positively influence patients’ awareness of OHCs and their engagement with the platform.

Appeal: expert and testimonial appeal

The influence of message narratives, particularly those coming from patients, experts, or celebrities, on health behavior have been previously investigated by scholars. Various studies have examined the effectiveness of different narrative sources in promoting health-related behaviors and attitudes. As such, Keller & Lehmann18 conducted a meta-analysis based on 60 studies, examining the impact of patient testimonials on health behavior. They concluded that case information (e.g., patient testimonials) stimulate health behavior, suggesting that narratives from individuals who have personal experience with a health issue can be effective in promoting behavior change. Furthermore, like previously mentioned, both Hsu23 and Jebarajakirthy et al.28, found that expert narratives positively influenced health behavior. Experts, such as healthcare professionals or researchers, are often perceived as credible sources of information, and their narratives may carry more weight in influencing health behavior. Besides work done on expert and patient narratives in health messaging, Emmers-Sommer & Terán22 explored the role of celebrity endorsements in health communication. They found that individuals tend to respond better to celebrity endorsements compared to other types of endorsements. However, it’s worth noting that while celebrities may be perceived as credible, consumers may not necessarily trust them as the only advocates for health issues. Previous work suggests that both patient testimonials and expert narratives can effectively influence health behavior, although in different ways. Patient testimonials may appeal to individuals on a more personal level, drawing from shared experiences and emotions, while expert narratives may provide authoritative and evidence-based information. However, it is unclear which of these narratives is more effective in generating awareness for OHCs and engagement of patients on these types of platforms. Considering the fact that Keller & Lehmann18 recommend strong source credibility to influence health behaviors among low-involvement audiences, it can be argued that expert narratives are more effective in enhancing awareness and engagement among newly reached audiences.

Appeal: informative and persuasive

In addition to the source of the message, the nature of the message itself is also considered a key component of its appeal.Within the health communication domain, authors used persuasive versus informative information in health messaging to influence health behavior, with studies exploring the effectiveness of different message types in driving health behavior. In this health context, we perceive informative information as factual information and persuasive information as an opinion or experience. Carey & Sarma20, conducted research on the impact of persuasive messages on driving behavior. They found that persuasive messages positively influenced driving behavior, particularly in the short term, suggesting that messages designed to persuade individuals to engage in specific behaviors can be effective in stimulating immediate action. In contrast, other work showed that informative messages positively influenced attitudes towards online advertising and can enhance perceived brand authenticity in the context of warm and competent brands49,50. These findings indicate that messages containing factual information can be effective in shaping perceptions and attitudes as well. However, Fu et al.47, noted that persuasive messages were perceived as counterproductive by marketers as they can potentially cause brand aversion. Whether this is also the case within the field of OHCs is unknown. Drawing upon the effectiveness of the emphasis of credibility in low audiences, we assume informative messaging will be more effective in generating awareness of and engagement in OHCs.

Linguistic style: first-person and third-person linguistic style

As previously mentioned, this study focuses on the linguistic content of messaging. This approach involves primarily using specific nouns, verbs, and adjectives to construct the message content in either a first-person or third-person narrative. There have been previous studies that considered the impact of first-person versus third-person linguistic style in health messaging on health behavior outcomes. Chen and Bell27 conducted research on the compelling nature of first-person linguistic narratives in health messaging. They found that first-person linguistic narratives enhanced the convincing power of health messages. However, their meta-analysis revealed that this did not necessarily result in desired health behavior changes among participants. This suggests that while first-person narratives may be effective in capturing attention and generating interest, they may not always lead to actual behavior change. In contrast, Keller & Lehmann18 concluded that directly targeted messaging may yield positive health behavior outcomes in low involvement audiences, but general messages were more effective in high involvement audiences. Their finding indicates that the effectiveness of linguistic style in health messaging may depend on the level of audience involvement and engagement with the message content. Considering these findings, we expect that a first-person narrative may be more effective in generating awareness, but that a third-person narrative is more effective in engagement of individuals in OHCs.

Designing the communication concepts

We designed and performed an online field experiment, namely a quasi-randomized study conducted in a real-world setting, that captures the online behavior of individuals after being exposed to various health related communication on AF. This online field experiment resulted in three datasets from Facebook, Instagram and the AF OHC website. On this website, members (i.e., patients and other stakeholders) can share experiences and insights on AF with the aim of co-creating new research pathways together with other patients and stakeholders on AF treatment and prevention. The dataset coming from Facebook and Instagram consists of 795,812 unique users that were reached, and the OHC dataset covers 18,426 website visitors in the Netherlands. Similar to the study conducted by Fritz et al.32 the online field experiment allowed us to measure individuals’ real-time behavior across multiple platforms. Therefore, the experiment is suitable to investigate not only the behavior of users towards health communication concepts upon the first encounter with the ad, but also the level of engagement after clicking. In total 12 communication concepts consisting of different combinations of communication elements (Table 6) were designed based on variable definitions from previous work on (health) behavior (Table 5) and AF patient experiences that were collected by the AFIP foundation (see Supplementary Table 1). Like Cavanaugh et al. and Fritz et al.15,32 we expressed communication elements through images and text while incorporating contexts of interest that were raised by AF patients. We then pre-tested the concepts (Supplementary Reference 3). The communication concepts are developed in collaboration with an in-kind contributing digital marketing agency with expertise in copywriting, website design and social advertising. After pre-testing, the final communication concepts were launched on Facebook and Instagram through paid advertising in the Netherlands. Figure 2 displays the structure of the online field experiment. For each communication concept, we developed a matching website landing page in the OHC of the AFIP foundation which included the same visual and similar textual elements as were displayed in the communication concept. Keeping in mind that self-efficacy is needed for individuals to act after processing health messages16, we included the message that something can be done about the situation in every communication concept and its’ matching landing page (Supplementary Reference 2).

In total, 12 different combinations (Table 6) of communication variables from the conceptual model (Fig. 1) fueled the communication concepts and concept landing pages on the website of the OHC. The online field experiment is conducted on Facebook and Instagram, where communication concepts are exposed to users, measured as impressions (IMP) which are not part of the conceptual model. The Click-Through Rate (CTR) of these concepts serves as a measure of awareness. After clicking on a concept, individuals are directed to the concept landing page of the OHC. During their visits to the OHC, Average Engagement Time (AET) and Community Subscription (CS) are tracked as indicators of user engagement. This design enables a comparison of how different communication elements impact both awareness and engagement.

Pre-testing the communication concepts

In April 2023, a pre-test was conducted among 165 atrial fibrillation (AF) patients to evaluate whether 12 communication concepts effectively reflected the intended communication variables. After removing incomplete responses, 118 participants remained. A digital marketing agency created two variations for each concept (e.g., 1.1 and 1.2), differing slightly in imagery and text. Participants were randomly shown two Facebook-style ads and asked to rate each using a matrix of 5-point Likert scales measuring emotional and content elements (e.g., “Terrifying,” “Loving,” “Representing expertise”). Following the approach of Cavanaugh et al.15, the highest-rated variation per concept was selected for the final experiment design. For instance, concept 2.1 (score: 20.4) was chosen over 2.2 (score: 17.9). Per concept, average ratings and standard deviations were documented. Based on these results, four concepts (i.e., 1, 3, 5, and 12) were revised to better align with the intended variables, using the framework of fundamental human motives by Griskevicius and Kenrick35. Supplementary Reference 3 provides the pre-test results.

The data and metrics

The online field experiment conducted in the Netherlands with an AF population target of at least 380 thousand patients in a time range of one month (May 23, 2023, until June 23, 2023). However, everyone above 18 years old was targeted to reach as many individuals as possible for a higher probability of substantial exposure of the communication concepts among caregivers and family members of patients. In total 795,812 unique Facebook and Instagram users were reached. The Facebook and Instagram dataset includes information on the online behaviors of users visiting these platforms while also providing demographic characteristics of the users which are self-reported of nature. As previously mentioned, CTR was measured as a signal of awareness. The OHC of the AFIP foundation on the other hand provided data on the user behavior that occurred on the website. Engagement of users was measured in two manners. First, average engagement time was measured with the premise that the more someone pays attention, the more someone learns about the subject59. Average engagement time is defined by Google as “the total length of time your website was in focus or your app was in the foreground across all sessions/the total number of active users” (Google, 2025, https://support.google.com/analytics/answer/11014767). Second, community subscriptions served as a measure of engagement, which was defined as the number of users that signed up to become a part of the community through a sign-up form that was provided on the website landing page.

A quasi-randomized design

While Meta provides an A/B testing framework that claims random ad delivery across conditions, recent research60 highlights the potential influence of platform-level optimization algorithms that adaptively adjust ad delivery to maximize engagement. Therefore, we do not claim strict randomization in the traditional RCT sense but rather followed a quasi-randomized design. Similar to Chopra et al.61, who describe their study as quasi-randomized due to staggered, externally imposed conditions at the cluster level, our ad campaigns were subject to stochastic delivery within fixed budgets and gender targeting. This quasi-randomized structure aims to create sufficient variation to estimate treatment effects under real-world conditions, particularly when also controlling for key covariates. To mitigate delivery bias and approximate random allocation as closely as possible within platform constraints, we: (1) structured campaigns with equal budgets and gender-based segmentation, (2) launched campaigns simultaneously to avoid time-based delivery bias, and (3) included key covariates (i.e., age, gender, device type, and time of day) as control variables in all regression analyses to account for potential confounding. Additionally, we included key demographic and contextual variables (age, gender, device type, platform, exposure frequency and time of day) as covariates in the regression models to control for potential confounding. Quasi-experimental online field experiments balance ecological validity with reasonable internal validity. As noted by Boegershausen et al.60 such designs are particularly useful for testing whether theoretically grounded interventions retain their effectiveness when deployed in real-world settings. While not suited for pure causal inference or theory testing, this approach allows for robust assessment of communication effectiveness under naturalistic conditions. Meta conducted the allocation of our communication concepts, targeting users aged 18 and older. To balance exposure between genders, we used restriction methods, splitting the experiment and managing the budget for men and women. Moreover, Meta’s auction system ranked communication concepts by a total value score, including bid amount, estimated user engagement, and quality of the communication concept. Their models predicted which concept each user was most likely to interact with based on behaviors on and off Facebook. Users were then directed to a specific concept landing page. Additionally, allocation concealment was ensured by Meta’s automated processes, preventing us and participants from influencing the assignment to the communication concepts. In the end, the sequence generation, enrollment, and assignment were fully managed by Meta. Anonymized data was accessed after finalization of the experiment, allowing for a blinded analysis. Facebook and Instagram served solely as distribution platforms and had no other role within the online field experiment.

Data analysis

To ensure enough power for this study, the online field experiment ran until each communication concept received at least 1000 visitors (i.e., participants the clicked on the communication concept) for its landing page. Everyone who interacted with the communication concepts were included in the study. By utilizing Python 3.10.12 Statsmodel and SPSS 29.0 linear regression models were trained, estimating the impact of communication elements on awareness and engagement metrics, namely CTR and average engagement time. Additionally, logistic regression was used to assess the effects on community subscriptions. A stepwise approach was used, starting with a basic model of the main communication elements’ effects on the outcome variables. More complete models were then iteratively constructed, incorporating control and interaction variables to examine their differential impact. This resulted in four models for engagement outcomes: the first assessing predictor variables, the second examining control variables, the third combining both, and the fourth including all variables and their interactions. For CTR, we constructed three models without interaction variables. The main models are based on engagement data (i.e., average engagement time and community subscriptions) of the OHC and is individual level of nature. Time (i.e., weekday vs. weekend, day vs. evening and work hours vs. non work hours) and device (i.e., mobile, desktop and tablet) were included as our control variables. Additionally, two supportive models based on the aggregated CTR performances of our communication concepts from Facebook and Instagram data were developed, to verify if the effects observed in the engagement model also hold in the awareness context. The analysis was divided into two parts: the first controlled for age, gender, and exposure frequency, while the second controlled for platform, device, and exposure frequency. There was no data monitoring committee. Supplementary Table 3 displays an overview of the variables used in our models.

Ethical approval and GDPR compliance

The research was approved by the Economics and Business Ethics Committee (EBEC) at the University of Amsterdam under reference number EB-9521. Participants accessing the AFIP foundation website provided informed consent prior to participation. For the advertisements conducted on Facebook, user engagement falls under the platform’s data use policy. All visuals used in the advertisements and on the AFIP foundation’s website were selected from the licensed Adobe stock image library. These images were chosen by the researchers and designers of the in-kind contributing agency and do not represent real patients, making additional consent unrequired. No personally identifiable information (PII) was collected at any stage of the study. The awareness dataset used in this study was established using aggregated and anonymized advertising performance data from Meta platforms (Facebook and Instagram). This dataset was generated within Meta’s Ads Manager, which provides summary-level (i.e., aggregated) metrics (e.g., impressions, click-through-rates, and reach) without any access to user-level data. The dataset does not contain personal data as defined under the GDPR, and is therefore not subject to its provisions (Recitals 26 EU GDPR, 2025, https://gdpr-info.eu/recitals/no-26/). Meta’s advertising tools function under the platform’s Terms of Service, to which users implicitly consent by creating and maintaining an account. For website behavior, we relied on pseudo anonymized data from Google Analytics 4 (GA4), which uses user_pseudo_ids rather than personal identifiers. To comply with GDPR, the OHC takes measures which include (1) obtaining explicit user consent for the use of analytics data for statistical and research purposes, (2) configuring GA4 with privacy-preserving settings, including the deactivation of Google Signals, (3) entering into a data processing agreement with Google in accordance with Article 28 of the GDPR (Art. 28 GDPR, https://gdpr-info.eu/art-28-gdpr/), and (4) applying strict organizational and technical controls to restrict access to GA4 data to authorized personnel only. Moreover, to improve transparency following the review process, a debrief page was published (Supplementary Reference 6) after the campaign concluded. This page outlines the purpose of the study, the nature of the data collected, and how privacy safeguards were upheld.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the data being website are proprietary and confidential, as they belong to the OHC, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. However, the code used for data preparation and statistical analyses is available on GitHub at https://github.com/mfkuipers.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is available in mfkuipers/AFPatientAwarenessEngagement and can be accessed via this link https://github.com/mfkuipers/AFPatientAwarenessEngagement.

References

Moorman, C., van Heerde, H. J., Moreau, C. P. & Palmatier, R. W. Marketing in the health care sector: disrupted exchanges and new research directions. J. Mark. 88, 1–14 (2024).

Zhang, Q., Zhang, R., Lu, X. & Zhang, X. What drives the adoption of online health communities? An empirical study from patient-centric perspective. BMC Health Serv. Res. 23, 524 (2023).

Hodgkin, P., Horsley, L., & Metz, B. The emerging world of online health communities (SSIR). Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. https://doi.org/10.48558/9JGH-H283 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Improving access to cardiovascular care for 1.4 billion people in China using telehealth. Npj Digit. Med. 7, 1–10 (2024).

Brundel, B. J. J. M. et al. Atrial fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 8, 1–23 (2022).

Van Gelder, I. C. et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): Developed by the task force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Endorsed by the European Stroke Organisation (ESO). Eur. Heart J. 45, 3314–3414 (2024).

Perez, M. V. et al. Large-scale assessment of a smartwatch to identify atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1909–1917 (2019).

Bull, C., Teede, H., Watson, D. & Callander, E. J. Selecting and implementing patient-reported outcome and experience measures to assess health system performance. JAMA Health Forum 3, e220326 (2022).

Kuipers, M. F. et al. Exploring diet-based treatments for atrial fibrillation: patient empowerment and citizen science as a model for quality-of-life-centered solutions. Nutrients 16, 2672 (2024).

Latif, M. S. & Wang, J.-J. The moderating role of face on value co-creation behavior and co-creation attitude in online health communities. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 77, 464–487 (2024).

Haag, C. et al. Blending citizen science with natural language processing and machine learning: Understanding the experience of living with multiple sclerosis. PLOS Digit. Health 2, e0000305 (2023).

Zhao, J., Wang, T. & Fan, X. Patient value co-creation in online health communities: Social identity effects on customer knowledge contributions and membership continuance intentions in online health communities. J. Serv. Manag. 26, 72–96 (2015).

Schwartz, L. M. & Woloshin, S. Medical Marketing in the United States, 1997-2016. JAMA 321, 80–96 (2019).

Krishen, A. S. & Bui, M. Fear advertisements: influencing consumers to make better health decisions. Int. J. Advert. 34, 533–548 (2015).

Cavanaugh, L. A., Bettman, J. R. & Luce, M. F. Feeling love and doing more for distant others: specific positive emotions differentially affect prosocial consumption. J. Mark. Res. 52, 657–673 (2015).

Berger, J. & Milkman, K. L. What Makes Online Content Viral? J. Mark. Res. (2012).

Berger, J., Moe, W. W. & Schweidel, D. A. What Holds Attention? Linguistic Drivers of Engagement. J. Mark. 87, 793–809 (2023).

Keller, P. A. & Lehmann, D. R. Designing Effective Health Communications: A Meta-Analysis. J. Public Policy Mark. 27, 117–130 (2008).

Kim, J., Yang, K., Min, J. & White, B. Hope, fear, and consumer behavioral change amid COVID-19: Application of protection motivation theory. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 46, 558–574 (2022).

Carey, R. N. & Sarma, K. M. Threat appeals in health communication: messages that elicit fear and enhance perceived efficacy positively impact on young male drivers. BMC Public Health 16, 645 (2016).

Forbes, S. J., Purkis, H. M. & Lipp, O. V. Better safe than sorry: simplistic fear-relevant stimuli capture attention. Cogn. Emot. 25, 794–804 (2011).

Emmers-Sommer, T. M. & Terán, L. The “Angelina Effect” and audience response to celebrity vs. medical expert health messages: an examination of source credibility, message elaboration, and behavioral intentions. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 17, 149–161 (2020).

Hsu, C.-W. Who and what messages are more suitable for health ads: the combined influence of endorsers and message framing on visual attention and ad effectiveness. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 76, 477–497 (2024).

Shen, F., Sheer, V. C. & Li, R. Impact of Narratives on Persuasion in Health Communication: A Meta-Analysis. J. Advert. 44, 105–113 (2015).

Arora, S., Debesay, J. & Eslen-Ziya, H. Persuasive narrative during the COVID-19 pandemic: Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg’s posts on Facebook. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 9, 1–10 (2022).

Chang, Y., Li, Y., Yan, J. & Kumar, V. Getting more likes: the impact of narrative person and brand image on customer-brand interactions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 47, 1027–1046 (2019).

Chen, M. & Bell, R. A. A meta-analysis of the impact of point of view on narrative processing and persuasion in health messaging. Psychol. Health 37, 1–18 (2022).

Jebarajakirthy, C., Das, M., Rundle-Thiele, S. & Ahmadi, H. Communication strategies: encouraging healthy diets for on-the-go consumption. J. Consum. Mark. 40, 27–43 (2022).

Lee, J., Kim, J. H., Choi, M. & Shin, J. A choice based conjoint analysis of mobile healthcare application preferences among physicians, patients, and individuals. Npj Digit. Med. 8, 1–9 (2025).

Jessup, D. L. et al. Implementation of digital awareness strategies to engage patients and providers in a lung cancer screening program: retrospective study. J. Med. Internet Res. 20, e8932 (2018).

Horrell, L. N. et al. Attracting users to online health communities: analysis of LungCancer.net’s facebook advertisement campaign data. J. Med. Internet Res. 21, e14421 (2019).

Fritz, M., Grimm, M., Weber, I., Yom-Tov, E. & Praditya, B. Can social media encourage diabetes self-screenings? A randomized controlled trial with Indonesian Facebook users. Npj Digit. Med. 7, 1–13 (2024).

Huang, S., Aral, S., Hu, Y. J. & Brynjolfsson, E. Social advertising effectiveness across products: a large-scale field experiment. Mark. Sci. 39, 1142–1165 (2020).

Gandolf, S. Healthcare Facebook Ads & Instagram Ads. Healthcare Success https://healthcaresuccess.com/blog/healthcare-marketing/four-reasons-facebook-instagram-advertising-are-essential-for-healthcare-marketing.html (2022).

Griskevicius, V. & Kenrick, D. T. Fundamental motives: How evolutionary needs influence consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 23, 372–386 (2013).

Wrobleski, K. K. & Snyder, C. R. Hopeful Thinking in Older Adults: Back to the Future. Exp. Aging Res. 31, 217–233 (2005).

Okuhara, T. et al. Encouraging COVID-19 vaccination via an evolutionary theoretical approach: A randomized controlled study in Japan. Patient Educ. Couns. 105, 2248–2255 (2022).

Siegenthaler, P. & Fahr, A. First-Person Versus Third-Person. Eur. J. Health Commun. 4, (2023).

Fang, Z., Liu, Y. & Peng, B. Empowering older adults: bridging the digital divide in online health information seeking. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11, 1–11 (2024).

Fayn, M.-G., des Garets, V. & Rivière, A. Collective empowerment of an online patient community: conceptualizing process dynamics using a multi-method qualitative approach. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21, 958 (2021).

Pick, C. M. et al. Fundamental social motives measured across forty-two cultures in two waves. Sci. Data 9, 499 (2022).

Wen, T. J., Wu, L., Dodoo, N. A. & Kim, E. The mood effect: How mood, disclosure language and ad skepticism influence the effectiveness of native advertising. J. Consum. Behav. 22, 1296–1308 (2023).

Pearson, G. D. H. & Cappella, J. N. Scrolling Past Public Health Campaigns: Information Context Collapse on Social Media and Its Effects on Tobacco Information Recall. (2024).

Noguti, V. & Waller, D. S. How the time of day impacts social media advertising outcomes on consumers. Mark. Intell. Amp Plan. 42, 418–437 (2024).

Green, B. M. et al. Assessment of adaptive engagement and support model for people with chronic health conditions in online health communities: combined content analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e17338 (2020).

Zhang, X. & Liu, S. Understanding relationship commitment and continuous knowledge sharing in online health communities: a social exchange perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 26, 592–614 (2021).

Fu, S., Zheng, X., Wang, H. & Luo, Y. Fear appeals and coping appeals for health product promotion: Impulsive purchasing or psychological distancing?. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 74, 103383 (2023).

Ort, A. & Fahr, A. Using efficacy cues in persuasive health communication is more effective than employing threats – An experimental study of a vaccination intervention against Ebola. Br. J. Health Psychol. 23, 665–684 (2018).

Eigenraam, A. W., Eelen, J. & Verlegh, P. W. J. Let Me Entertain You? The Importance of Authenticity in Online Customer Engagement. J. Interact. Mark. 54, 53–68 (2021).

Lütjens, H., Eisenbeiss, M., Fiedler, M. & Bijmolt, T. Determinants of consumers’ attitudes towards digital advertising – A meta-analytic comparison across time and touchpoints. J. Bus. Res. 153, 445–466 (2022).

Van Kleef, G. A. & Côté, S. The social effects of emotions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 73, 629–658 (2022).

Ludwig, S. et al. More than words: the influence of affective content and linguistic style matches in online reviews on conversion rates. J. Mark. 77, 87–103 (2013).

Graham, R. G. & Martin, G. I. Health behavior: a Darwinian reconceptualization. Am. J. Prev. Med. 43, 451–455 (2012).

Kenrick, D. T., Griskevicius, V., Neuberg, S. L. & Schaller, M. Renovating the pyramid of needs: contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 5, 292–314 (2010).

Heimbach, I. & Hinz, O. The impact of content sentiment and emotionality on content virality. Int. J. Res. Mark. 33, 695–701 (2016).

Snyder, C. R. Hope theory: rainbows in the mind. Psychol. Inq. 13, 249–275 (2002).

Higbee, K. L. Fifteen years of fear arousal: Research on threat appeals: 1953-1968. Psychol. Bull. 72, 426–444 (1969).

Herhausen, D., Ludwig, S., Grewal, D., Wulf, J. & Schoegel, M. Detecting, preventing, and mitigating online firestorms in brand communities. J. Mark. 83, 1–21 (2019).

Ward, A. F., Zheng, J.(F. rank) & Broniarczyk, S. M. I. share, therefore I know? Sharing online content - even without reading it - inflates subjective knowledge. J. Consum. Psychol. 33, 469–488 (2023).

Boegershausen, J., Cornil, Y., Yi, S. & Hardisty, D. J. On the persistent mischaracterization of Google and Facebook A/B tests: How to conduct and report online platform studies. Int. J. Res. Mark. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2024.12.004 (2025).