Abstract

To address the diversity of skin conditions and the low prevalence of skin cancers, we curated a large hospital dataset (National Information Society Agency, Seoul, Korea [NIA] dataset; 70 diseases, 152,443 images) and collected real-world webapp data (https://modelderm.com; 1,691,032 requests). We propose a conservative evaluation method by assessing sensitivity in hospitals and specificity in real-world use, assuming all malignancy predictions were false positives. Based on three differential diagnoses, skin cancer sensitivity in Korea was 78.2% (NIA) and specificity was 88.0% (webapp). Top-1 and Top-3 accuracies for 70 diseases (NIA) were 43.3% and 66.6%, respectively. Analysis of webapp data provides insights into disease prevalence and public interest across 228 countries. Malignancy predictions were highest in North America (2.6%) and lowest in Africa (0.9%), while benign tumors were most common in Asia (55.5%), and infectious diseases were most prevalent in Africa (17.1%). These findings suggest that AI can aid global dermatologic surveillance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has demonstrated remarkable performance in dermatology, often surpassing dermatologists in certain controlled conditions1. Those studies, mostly encompassing skin cancer and utilizing clinical photographs and dermoscopy images, have shown that AI can outperform dermatologists when diagnoses are based solely on image data2,3,4,5. The performance of various AI models has been validated using a variety of publicly available dermatology datasets6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

Unlike in radiology and ophthalmology, vision AI models in dermatology have not been yet clinically successful for several reasons. First, AI performance in dermatological conditions tends to be overestimated in the reader test when conducted with limited information. Unlike radiologists who detect specific findings from X-ray images or ophthalmologists who interpret fundus imaging to determine diabetic retinopathy, dermatologists rely on a variety of contextual and patient-specific information outside of imaging to make a diagnosis. Second, AI performance can decrease due to out-of-distribution (OOD) cases in real-world situations. While images utilized in radiology or ophthalmology are taken with specialized medical equipment or by medical staffs following DICOM standards, resulting in more standardized samples, most images used in dermatology outside research settings are taken with non-medical equipment such as non-professional consumer cameras or smartphone cameras in a non-standardized manner and are often acquired by non-medical personnel, resulting in frequent OOD scenarios15.

Consequently, while AI may outperform dermatologists in purely image-based diagnoses using preprocessed in-distribution datasets, clinicians in real practice tend to be more accurate16. Historical examples, such as the MelaFind algorithm, which received FDA approval but ultimately disappeared from the market due to high false-positive rates, highlight how AI algorithms that perform well under controlled conditions can struggle in real-world applications17. In addition, the results may be distorted because most test sets do not reflect disease prevalence, as the ratio of benign to malignant disease in most test datasets is lower than 10:1. Real-world data is also complicated and influenced by the wide variation in skin color and ethnic skin types which creates unique variations that creates specific challenges to AI algorithms. For these reasons, it is important to measure AI algorithms performance using real-world data, especially when evaluating specificity.

In a prior national validation study performed in Korea, we separately calculated the sensitivity and specificity. In order to precisely assess sensitivity, we created a dataset comparable to the annual number of skin cancer cases in Korea. To evaluate specificity, we analyzed the malignancy predictions made by the algorithm in actual use. Additionally, to assess multi-class performance, we analyzed 152,443 images across 70 diseases. Finally, to understand the implications of worldwide skin variation, we investigated global disease prediction patterns using the algorithm, aiming to get insights into user interests and disease prevalence.

Results

NIA and SNU dataset analysis

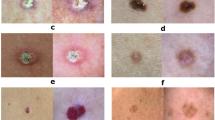

The NIA (National Information Society Agency) dataset consists of 152,443 clinical photographs, covering 70 distinct diseases. (Table 1) The SNU (Seoul National University Hospital) test dataset consists of 240 clinical photographs, covering 80 distinct diseases (Supplementary Table 1).

For binary classification of malignancy or not, the algorithm achieved an AUC of 0.946 (95% CI 0.942–0.950) in the NIA dataset, using the data on benign and malignant tumors (n = 51,038 images, 33 diseases). (Fig. 1a) The sensitivity and specificity of the algorithm were calculated through the three differential diagnoses suggested by the algorithm (Top-3), which is an established metric5. The sensitivity and specificity of the algorithm were 78.2% (95% CI 77.0–79.4%) and 93.0% (95% CI 92.8–93.3%) for the NIA dataset. For the SNU test dataset, the AUC was 0.958 (95% CI 0.919–0.997). (Fig. 1b) When calculated from the Top-3, sensitivity and specificity were 87.5% (95% CI 73.2–95.8%) and 91.0% (95% CI 86.1–94.6%) for the SNU test dataset (Supplementary Table 2).

The performance of the algorithm, calculated based on Top-1 or Top-3 predictions, is drawn separately in the figure. a TEST = Benign and malignant tumors in the NIA dataset (51,038 images, 33 diseases). b TEST = SNU Test Dataset (240 images, 80 diseases); The results from six continents are based on 61,066 assessments collected from 138 countries. Country-level results are presented only for the top 10 countries with the highest number of responses. Detailed data by country can be found in Supplementary Table 3. AF Africa, AS Asia, BR Brazil, DE Germany, ES Spain, EU Europe, FR France, HU Hungary, IT Italy, KR South Korea, NA North America, OC Oceania, PL Poland, RU Russia, SA South America, US United States.

For multi-class classification of matching exact diagnosis, the algorithm achieved micro-averaged mean Top-1 and Top-3 accuracies of 43.3% and 66.6% on the NIA dataset, respectively. (Table 1) The micro-averaged mean Top-1 and Top-3 accuracies showed 63.3% and 83.2% on the SNU test dataset, which were comparable to the 49.9% and 67.2% performance involving 2 dermatologists and 2 dermatology residents in the previous study4.

In the reader test (SNU test dataset), involving 61,066 assessments from 138 countries for determining malignancy or not, the mean sensitivity and specificity of global users were 55.2% (95% CI 54.2–56.2%) and 84.3% (95% CI 84.0–84.6%), respectively, which were significantly lower than the performance of the algorithm for the same 61,066 cases (86.8% [95% CI 86.2–87.5%] and 91.0% [95% CI 90.8–91.2%]) (both p < 0.0001, McNemar). (Supplementary Table 3) As shown in Fig. 1b, reader sensitivity was significantly higher in North America (64.0%), Oceania (62.6%), and Europe (59.2%) than in Asia (51.7%), South America (50.6%), and Africa (43.8%) (p < 0.0001, Chi-square with Bonferroni correction).

Global user performance

Global usage statistics from 1,691,032 requests showed notable regional variations. The distribution of requests by region was as follows: Europe (47.9%), Asia (31.5%), North America (10.1%), South America (5.7%), Africa (2.9%), and Oceania (1.9%). The top five countries by usage were Korea (22.6%), Italy (9.0%), United States (6.2%), Germany (5.9%), and France (4.0%) (Table 2, Supplementary Table 5).

The algorithm’s predictions showed distinct regional diagnostic trends. The highest proportion of the algorithm’s predictions were for benign tumors, which accounted for 65.2% in Korea. (Table 2) In terms of benign tumor predictions, the ranking by region was as follows (‘>’ indicates p < 0.0001 by Chi-Square with Bonferroni correction): Asia (55.5%) > Oceania (46.8%) > (p = 1.000) Europe (46.5%) > North America (38.0%) > South America (32.3%) > Africa (22.4%).

Regarding malignancy predictions using Top-1 diagnosis, the rate was 2.1% in Korea. (Table 2) The regional distribution of malignancy predictions was as follows (‘>’ indicates p < 0.0001 by Chi-Square with Bonferroni correction): North America (2.6%) > Europe (1.9%) ≈ (p = 0.5402) Asia (1.8%) ≈ (p = 0.9308) Oceania (1.7%) > (p = 0.0002) South America (1.4%) > Africa (0.9%).

Infectious conditions were predominantly predicted in Africa and South America than other regions, with higher frequencies observed in the Middle East and Northern Africa on the country map (Fig. 2c). The regional distribution was as follows (‘>’ indicates p < 0.0001 by Chi-Square with Bonferroni correction): Africa (17.1%) > South America (14.8%) > North America (12.9%) > Europe (11.5%) > Asia (10.0%) > Oceania (8.6%). Unlike other disease groups, allergic diseases showed relatively consistent trends across regions (Fig. 2d).

A worldwide map illustrating the differences in the algorithm’s predictions across various disease groups. This reflects both the interest in the disease and its prevalence. Interactive demo is available at https://whria78.github.io/nia/demoa Malignant tumors (countries with fewer than 1000 requests were excluded) b Benign tumors c Infectious diseases d Allergic diseases.

The ten most commonly predicted diseases were as follows: melanocytic nevus (20.9%), seborrheic keratosis (4.6%), cherry hemangioma (2.2%), dermatofibroma (2.1%), folliculitis (2.0%), wart (2.0%), lentigo (2.0%), hemangioma (2.0%), urticaria (1.9%), and actinic keratosis (1.9%). (Supplementary Table 6) Folliculitis was more prevalent in the Middle East and Southeast Asia on the map, while actinic keratosis was more common in North America and Australia (Fig. 3).

A worldwide map illustrating how the algorithm’s predictions and usages vary across common diseases. The selection of the 10 common diseases was based on algorithm usage as shown in Supplementary Table 6: a melanocytic nevus, b seborrheic keratosis, c cherry hemangioma, d dermatofibroma, e folliculitis, f wart, g lentigo, h hemangioma, i urticaria, and j actinic keratosis.

Regarding malignancy diagnosis using Top-3 predictions, the rate was 12.0% (95% CI 11.8–12.1%) in Korea and 10.0% (95% CI 9.9–10.0%) globally. (Supplementary Table 4) Assuming that all malignancy diagnoses by the algorithm were false positives, the estimated specificity using Top-3 in Korea was 88.0% (95% CI 87.9–88.2%), and 90.0% (95% CI 90.0–90.1%) globally. By continent, the malignancy predictions using Top-3 was as follows: North America (11.7%), Asia (10.9%), Europe (9.3%), Oceania (9.0%), South America (8.0%), and Africa (6.7%).

Discussion

Here, we present the worldwide study evaluating the real-clinical use of an open-access global dermatology AI service with 1.69 million assessments from 228 different countries. These large number of requests reflects strong user interest in dermatology AI apps and confirm the utility apps in daily clinical practice. However, evaluating the real-world performance of AI in dermatology is highly challenging because a continuous dataset linking AI results to biopsy outcomes is required. However, due to lack of population-based reference skin cancer datasets and the current lack of digitalization in clinical practice, obtaining large datasets with serial results is virtually impossible18. Furthermore, evaluating ‘specificity’ is problematic, as curated hospital datasets fail to capture the wide range of out-of-distribution conditions encountered in real-world settings.

A substantial discrepancy exists between the performance of diagnoses based on images alone and diagnosing in actual clinical practice. For the diagnosis of 43 tumor types, attending physicians achieved Top-1 and Top-3 accuracies of 68.1% and 77.3%, whereas physicians in the reader test achieved only 37.7% and 53.4% for the same cases, respectively16. Although AI has demonstrated exceptional performance in controlled settings, it must prove its effectiveness in real-world environments to be meaningful in clinical practice19,20. Despite the large number of retrospective studies, real-world evidence remains insufficient. As of 2024, only 86 medical AI algorithms have reported RCT-level evidence, and among these, 70 achieved successful outcomes, and of these, only 1 exists in the field of dermatology21,22.

We curated a large dataset representing cancer cases in Korea to estimate the sensitivity for cancer diagnosis. To assess specificity, we analyzed usage statistics under the assumption that all AI-determined malignancy predictions were false positives. This separated approach enabled us to estimate the algorithm’s real-world performance in terms of sensitivity and specificity.

First, regarding the sensitivity, the maximum sensitivity was estimated under the assumption that false negatives are minimal if using the national-scale hospital dataset. The NIA dataset is large enough to represent skin cancer cases in Korea. Therefore, the sensitivity of 78.2% (95% CI, 77.0–79.4%), predicted by three differentials, was presented as the ideal maximum value achievable in real-world settings. If users capture only low-quality images, the sensitivity could be lower15,23. Conversely, in practice, repeated testing of a lesion over days may increase sensitivity.

Next, regarding specificity, the minimum specificity was estimated under the assumption that there are no true negatives (= all false positives) in the usage data. The analysis of usage records in Korea showed that the algorithm predicted malignancy at a rate of 12.0% (95% CI, 11.8–12.1%) based on three differentials. Given the relatively low prevalence of cancer, if we assume all malignancy predictions by the algorithm are false positives, the specificity was estimated at 88.0% (95% CI, 87.9–88.2%). (Supplementary Table 4) This figure (88.0%) is lower than the specificity reported for the NIA dataset (93.0%; Table 1). At first glance, benign tumors requiring hospital visits may seem harder for AI to diagnose than various skin conditions seen in daily life. However, real-world use includes out-of-distribution scenarios, likely affecting the degradation of AI performance. On the other hand, actual specificity may be slightly higher than our 88.0% estimate, as users often confirm malignant results through repeated tests before hospital visits.

From the perspective of disease screening, WHO tuberculosis guidelines set minimal requirements of 90% sensitivity and 70% specificity24. Similarly, the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium benchmarks highlight 86.9% sensitivity and 88.9% specificity for breast cancer screening25. However, for skin cancer screening, no precise guidelines for the sensitivity and specificity currently exist26. Furthermore, concerns about overdiagnosis in dermatologist-led skin cancer screenings highlight the need to discuss using algorithms with lower real-world performance. As seen in Fig. 2a, the higher malignancy rate on the map may be related to greater algorithm usage for skin cancer, similar to how an increase in dermatology clinics is associated with a higher regional incidence of melanoma27,28. However, unlike human physicians, algorithms can be adjusted to operate with either very high specificity or low by modifying the threshold. For example, in scenarios where concerns about overdiagnosis, the threshold could be raised to identify only cancers with the highest diagnostic certainty, particularly in populations with limited access to healthcare. From this perspective, there should be an effort to find proper settings by each region and demonstrate the improvement of clinical outcomes (mortality, morbidity, and costs).

The usage statistics revealed significant regional differences in the types of diseases predicted by the algorithm. (Figs. 2, 3, Supplementary Table 3) Neoplastic disorders were more commonly predicted in Asia, Europe, and North America. (Fig. 2) Premalignant conditions such as actinic keratosis were observed at higher rates in Australia and North America. (Fig. 3) Interestingly, in line with these findings, users from the EU, North America, and Oceania showed higher sensitivity in the global reader test compared to those from other regions. (Fig. 1b) In contrast, infectious diseases were more frequently observed in regions such as Northern Africa and the Middle East. (Fig. 2c) These regional differences reflect variations in disease prevalence, the age demographics of users, and the diseases users are particularly concerned about in each region. For example, in South Korea, despite the low prevalence of skin cancer, high interest in skin cancer in the media may lead to a higher malignancy ratio as shown in Fig. 2a. These data, collected before patients even visit the clinic, can offer more accurate insights into the prevalence and interest in specific skin conditions. The global burden of disease study has been attempted, but only for certain disease groups, with no individual approach to dermatological diseases29,30,31. This indicates that AI-based big data analytics could significantly contribute to understanding skin disease trends globally.

Our study has several limitations. The first part of the study was limited to patients with skin types III and IV, which account for the vast majority of skin types in Korea. Therefore, we were unable to provide stratified data by race and skin type, especially in the population of dark skin tones32. Additional studies are required to evaluate the sensitivity for skin cancer in white and black populations.

Second, the NIA dataset does not include less common skin cancers beyond the four major types (e.g. Merkel cell carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma). According to 20 years of incidence statistics in Korea, these other types account for approximately 11.3% of all skin cancers33. In particular, early detection with AI can be beneficial for rare but very poor-prognosis skin cancers such as cutaneous angiosarcoma34. Therefore, rare cancers not represented in the NIA dataset should be collected and analyzed using appropriate statistical sample size considerations to ensure sufficient power and validity.

Third, the sensitivity and specificity calculated in this study needs to be re-evaluated through further digital transformation efforts, separately for each indication. The global study lacked a gold standard in order to calculate sensitivity and specificity. Ideally, users could provide feedback on final diagnosis based on clinical follow-up, laboratory work-up or final histopathological assessment. Further validation should be tried individually in each country, tailored to the healthcare environment35.

Fourth, in terms of multi-class results, the algorithm achieved Top-1 and Top-3 accuracies of 43.3% and 66.6% on the NIA dataset. Although the multi-class performance of the algorithm was validated using the large dataset, its real-world accuracy also needs to be reassessed in further studies.

Fifth, because of this being the study to evaluate real-use of global users of a single algorithm, it was challenging to determine the best approach. Since usage varies over time, it is displayed as the disease ratio within each country.

Sixth, although this was a global study, data from Africa, South America, and Oceania were relatively underrepresented, which may reflect regional differences in population size, access to digital healthcare, and overall engagement with digital health initiatives.

Finally, while the algorithm was designed to prioritize high specificity, it may be perceived as insufficient from the perspective of maximizing sensitivity. Although high sensitivity has been favored to avoid missing malignant cases, this approach often results in a high false-positive rate, as seen in the case of MelaFind17. In the context of AI tools that may be used frequently by laypersons without clinical oversight, insufficient specificity could amplify overdiagnosis27 and unnecessary anxiety. Therefore, our specificity-focused design aligns with concerns about overdiagnosis and false alarms, particularly in low-risk populations. However, it limits the algorithm’s ability to capture all true positives.

In conclusion, using a national-scale curated dataset and real-world usage data, the performance of AI in diagnosing skin cancer in Korea could be estimated at 78.2% (95% CI, 77.0–79.4%) sensitivity and 88.0% (95% CI, 87.9–88.2%) specificity. In multi-class classification, our algorithm achieved Top-1 and Top-3 accuracies of 43.3% and 66.6%, respectively, replicating the results obtained from the past small study4. Furthermore, this study highlights the potential of AI algorithms to provide a global perspective on skin diseases, offering a quantitative reflection of regional variations using AI-based big data analytics. Further research is needed to identify clinical settings where AI can effectively improve clinical outcomes. Additionally, the need for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and validation in underrepresented regions, such as Africa and South America, must be explicitly emphasized to ensure the algorithm’s effectiveness and generalizability across diverse populations.

Methods

This study adheres to the STARD 2015 guidelines and was approved by the Kangnam Sacred Hospital Institutional Review Board (2021-10-011, 2024-02-028-004) as a retrospective study.

Datasets for validation

-

1.

The NIA dataset consists of 152,443 clinical photographs (2001–2021) taken with professional DSLR cameras by dermatology residents or professional photographers from 92,004 random cases, covering 70 distinct skin diseases36. (Table 1) Among these, 4250 cases (4.6%) are malignancies, including 734 melanomas, 1804 basal cell carcinomas (BCC), 1601 invasive squamous cell carcinomas (SCC), and 111 in situ squamous cell carcinomas (Bowen’s disease) cases. The number of malignancies in the NIA dataset is comparable to Korea’s annual average number of skin cancer cases (4498) based on 20 years of statistics33. Assuming 80% sensitivity and a sample size of 4250, the 95% confidence interval for precision was ±1.18% (Wilson score method). Diagnoses were validated based on clinical diagnoses or pathology reports in cases of malignancy. The NIA dataset was compiled from 9 university hospitals in Korea. From each clinical image, the lesion of interest was manually cropped to generate standardized square images. These cropped images were then reviewed by two dermatologists, and only those deemed consistent with the diagnosis were included. Images that were blurry, poorly focused, diagnostically ambiguous, or not included in the predefined set of 70 diagnoses were excluded. A total of 52 board-certified dermatologists and 35 dermatology residents participated in data processing.

-

2.

The SNU test dataset consists of 240 clinical photographs, covering 80 distinct diseases. (Supplementary Table 1) The dataset includes 40 malignancy cases, comprising 7 Bowen’s disease, 3 keratoacanthoma, 8 BCC, 8 SCC, and 14 melanoma cases. Both malignant and benign tumors had histopathological confirmation, while other benign non-tumoral conditions were diagnosed clinically. This public dataset was compiled in a previous study that includes the reader test results from 21 dermatologists and 23 laypersons4. In this study, a global reader test was conducted using the same SNU test dataset in a mobile environment (https://www.modelderm.com/#quiz; Supplementary Note 1). The global reader test consists of image-based questions, randomly sorted and presented in a binary (yes/no) format, asking whether the condition is cancerous. To prevent cheating (e.g., using multiple devices to find the correct answers), each installation of the app presents a unique, shuffled order of questions.

Global usages study

We analyzed 1,691,032 requests submitted over 2.5 years (2022.7.7–2025.1.18) by 371,757 global users to the mobile app (https://modelderm.com). (Table 2, Supplementary Table 3) At no point were potentially identifiable data such as user registration information, device identifiers, or patient images collected or stored, and all data used for analysis remained at the level of de-identified server logs. As the submission was fully anonymized, informed consent was not required under current regulatory standards (U.S. Common Rule, 45 CFR §46.104[d][4]; European GDPR, Recital 26). All user-submitted images were included in the analysis, including those that received a low-quality warning from the app, which may have introduced variability in image quality and potentially affected diagnostic performance. Algorithm’s predictions were categorized into five groups: benign tumors, malignant tumors, infectious diseases, allergic diseases, and miscellaneous. (Table 1) Wart was counted under both benign tumors and infectious diseases because it should be distinguished from verrucous skin cancer.

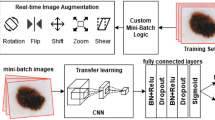

Algorithm

The NIA and SNU test dataset were tested using ModelDerm Build2024 (https://modelderm.com, Supplementary Note 1). For global usage statistics, Build2024 was used during 2024–2025, while Build202115 was used during 2022–2023. The architecture of the algorithm is an ensemble of ResNet variants. The algorithm was developed using an R-CNN-based approach, designed to incorporate out-of-distribution data as much as possible. This method involved manually annotating lesions from numerous R-CNN predictions, extracting them from a vast collection of internet and public images.

Statistical analysis

Model performance was evaluated using sensitivity, specificity, and top-n accuracy. Sensitivity and specificity for determining malignancy can be derived from one prediction (Top-1) or three predictions (Top-3) of the algorithm. The results of sensitivity and specificity were calculated using the Top-3. The ROC curve was drawn using the malignancy score which is composed of the output for malignant and premalignant diseases4. A 95% confidence interval (CI) was reported for all results using the binomial distribution method. When reporting the average, the macro-averaged mean is used unless otherwise indicated, and the micro-averaged mean is explicitly specified when applicable. The standard error for a proportion is the square root of the proportion times its complement, divided by the sample size, and the z-score of 1.96 is used to calculate the 95% confidence interval. To account for Type I error when performing Chi-square tests to sequentially compare values across six continents, we applied the Bonferroni correction by multiplying the p-value by 5. All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.3.3; https://www.r-project.org/). ROC curves were created using matplotlib (version 3.10.0; https://matplotlib.org/).

Data availability

ModelDerm Build2024 can be freely tested on mobile devices or PCs at: https://modelderm.com. Interactive demo showing the global distribution of skin disease predictions: https://whria78.github.io/nia/demo. The SQL dump of usage logs is available at: https://github.com/whria78/nia. The clinical images in the NIA dataset are a private collection from nine universities and cannot be publicly shared. The dataset was created with the support of the National Information Society Agency (NIA).

References

Salinas, M. P. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of artificial intelligence versus clinicians for skin cancer diagnosis. NPJ Digital Med. 7, 125 (2024).

Esteva, A. et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 542, 115–118 (2017).

Haenssle, H. A. et al. Man against machine reloaded: performance of a market-approved convolutional neural network in classifying a broad spectrum of skin lesions in comparison with 96 dermatologists working under less artificial conditions. Ann. Oncol. 31, 137–143 (2020).

Han, S. S. et al. Augmented intelligence dermatology: deep neural networks empower medical professionals in diagnosing skin cancer and predicting treatment options for 134 skin disorders. J. Investig. Dermatol. 140, 1753–1761 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. A deep learning system for differential diagnosis of skin diseases. Nat. Med. 26, 900–908 (2020).

Giotis, I. et al. MED-NODE: a computer-assisted melanoma diagnosis system using non-dermoscopic images. Expert Syst. Appl. 42, 6578–6585 (2015).

Kawahara, J., Daneshvar, S., Argenziano, G. & Hamarneh, G. Seven-point checklist and skin lesion classification using multitask multimodal neural nets. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 23, 538–546 (2018).

Tschandl, P., Rosendahl, C. & Kittler, H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Sci. Data 5, 1–9 (2018).

Daneshjou, R., Yuksekgonul, M., Cai, Z. R., Novoa, R. & Zou, J. Y. Skincon: a skin disease dataset densely annotated by domain experts for fine-grained debugging and analysis. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 18157–18167 (2022).

Ricci Lara, M. A. et al. A dataset of skin lesion images collected in Argentina for the evaluation of AI tools in this population. Sci. Data 10, 712 (2023).

Chiou, A. S. et al. Multimodal Image Dataset for AI-based Skin Cancer (MIDAS) Benchmarking. NEJM AI. 2, AIdbp2400732 (2024).

Gottfrois, P. et al. in International Conference on Medi cal Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. 703–712 (Springer, 2015).

Codella, N. C. et al. In 2018 IEEE 15th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI 2018). 168–172 (IEEE, 2018).

Brinker, T. J. et al. Comparing artificial intelligence algorithms to 157 German dermatologists: the melanoma classification benchmark. Eur. J. Cancer 111, 30–37 (2019).

Han, S. S. et al. The degradation of performance of a state-of-the-art skin image classifier when applied to patient-driven internet search. Sci. Rep. 12, 16260 (2022).

Han, S. S. et al. Assessment of deep neural networks for the diagnosis of benign and malignant skin neoplasms in comparison with dermatologists: a retrospective validation study. PLoS Med. 17, e1003381 (2020).

Venkatesh, K. P., Kadakia, K. T. & Gilbert, S. Learnings from the first AI-enabled skin cancer device for primary care authorized by FDA. npj Digital Med. 7, 156 (2024).

Hidalgo, L. et al. Creating a dermatologic database for artificial intelligence, a Chilean experience, and advice from ChatGPT. JEADV Clin Pract. 4, 296–298 (2025).

Navarrete-Dechent, C. et al. Automated dermatological diagnosis: hype or reality?. J. investi. Dermatol. 138, 2277 (2018).

Topol, E. J. Welcoming new guidelines for AI clinical research. Nat. Med. 26, 1318–1320 (2020).

Han, S. S. et al. Evaluation of artificial intelligence–assisted diagnosis of skin neoplasms: a single-center, paralleled, unmasked, randomized controlled trial. J. Investig. Dermatol. 142, 2353–2362. e2352 (2022).

Han, R. et al. Randomised controlled trials evaluating artificial intelligence in clinical practice: a scoping review. Lancet Digital Health 6, e367–e373 (2024).

Muñoz-López, C. et al. Performance of a deep neural network in teledermatology: a single-centre prospective diagnostic study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 35, 546–553 (2021).

Organization, W. H. High priority target product profiles for new tuberculosis diagnostics: report of a consensus meeting, 28-29 April 2014, Geneva, Switzerland. (World Health Organization, 2014).

Lehman, C. D. et al. National performance benchmarks for modern screening digital mammography: update from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Radiology 283, 49–58 (2017).

Sangers, T. E. et al. Position statement of the EADV Artificial Intelligence (AI) Task Force on AI-assisted smartphone apps and web-based services for skin disease. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 38, 22–30 (2024).

Welch, H. G., Mazer, B. L. & Adamson, A. S. The rapid rise in cutaneous melanoma diagnoses. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 72–79 (2021).

Navarrete-Dechent, C. & Lallas, A. Overdiagnosis of melanoma: is it a real problem? Dermatol. Pract. Conceptual 13, e2023246 (2023).

Flohr, C. & Hay, R. Putting the burden of skin diseases on the global map. Br J Dermatol. 184, 189–190 (2021).

Murray, C. J. The global burden of disease study at 30 years. Nat. Med. 28, 2019–2026 (2022).

Wyper, G. The global burden of disease study and Population Health Metrics. Popul. Health Metr. 22, 1–5 (2024).

Daneshjou, R. et al. Disparities in dermatology AI performance on a diverse, curated clinical image set. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq6147 (2022).

Kwon, S. H. et al. Incidence and survival rates of primary cutaneous malignancies in Korea, 1999–2019: a nationwide population-based study. J. Dermatol. 51, 532–538 (2024).

Cao, J., Wang, J., He, C. & Fang, M. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am. J. cancer Res. 9, 2303 (2019).

Smak Gregoor, A. M. et al. An artificial intelligence based app for skin cancer detection evaluated in a population based setting. NPJ digital Med. 6, 90 (2023).

Kim, D.-W., Jang, G. & Kim, H.-J. Development of CNN-based Semantic Segmentation Algorithm for Crop Classification of Korean Major Upland Crops Using NIA AI HUB (IEEE, 2025).

Acknowledgements

S.S. Han and S.I. Cho have full access to all the data used in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. Han, J.I. Na, and S.I. Cho designed the experiments.S.I. Cho, J. Na, S.H. Kim, and S.S. Han prepared the datasets and performed the experiments.S.S. Han, S.I. Cho, N. Cristian, J. Na, F. Gröger, A.A. Navarini, M.S. Kim, D.H. Lee, J.H. Lee, J. Kim, C.H. Won, K.N. Bae, J.B. Lee, H.S. Yoon, S.E. Chang, and S.H. Kim interpreted the results.S.S. Han, S.I. Cho, N. Cristian, J. Na, F. Gröger, A.A. Navarini, M.S. Kim, D.H. Lee, J.H. Lee, J. Kim, C.H. Won, K.N. Bae, J.B. Lee, H.S. Yoon, S.E. Chang, and S.H. Kim wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures.S.S. Han, J. Na, S.I. Cho, and N. Cristian supervised the entire experiment.All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.S. Han is the founder and CEO of IDerma, Inc.; S.I. CHo is an employee of Lunit. A.A.N. is a shareholder of Derma2Go AG and Derma.One GmbH. All other authors have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, S.S., Cho, S.I., Fabian, G. et al. Planet-wide performance of a skin disease AI algorithm validated in Korea. npj Digit. Med. 8, 603 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01980-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01980-w