Abstract

Accurate characterization of atherosclerotic plaques in intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) imaging is essential for evaluating coronary artery disease and guiding clinical interventions. Traditional methods rely on handcrafted features and rule-based algorithms, which lack adaptability to diverse lesion morphologies and offer limited explainability. To address these challenges, this work introduces PlaqueCap, a lesion-centered captioning framework that generates clinically meaningful, natural language descriptions directly from IVUS images. A central challenge is ensuring the generated text is grounded in the specific pathology of the lesion. PlaqueCap solves this by performing high-fidelity segmentation to localize the plaque, then using a Lesion Prompt Injection (LPI) module to inject spatial information into a pre-trained vision-language model, focusing on pathological characteristics. Experimental results on a curated IVUS dataset show PlaqueCap achieves accurate lesion localization and classification, producing detailed, clinically interpretable descriptions surpassing baselines in quantitative metrics and expert evaluation. This offers a paradigm for explainable AI in intravascular imaging and automated reporting in interventional cardiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronary artery disease stands as one of the most significant public health challenges of our time, remaining a principal cause of mortality worldwide1. Central to the management of this condition is the timely and accurate assessment of atherosclerotic plaques, the pathological hallmarks of the disease2. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) has emerged as an indispensable imaging modality in this domain, offering clinicians an unparalleled, high-resolution cross-sectional view of the coronary arteries. This technology allows for the direct visualization of intricate details of the vessel wall, plaque burden, and composition, providing critical insights that guide clinical decision-making, from risk stratification to intervention planning3. Despite its profound clinical utility, the interpretation of IVUS imagery remains a significant bottleneck. The process is heavily reliant on the manual reading of expert physicians, a task that is not only time-consuming and labor-intensive but also susceptible to inter-observer variability4. Subtle textural differences that distinguish a stable fibrous plaque from a vulnerable lipid-rich one can be interpreted differently, and the semantic richness of a visual finding is often lost when condensed into simple measurements5.

Over the past decade, the field has witnessed numerous efforts to automate the analysis of IVUS images through computational methods. Early, traditional approaches sought to codify expert knowledge into algorithms, relying on handcrafted features such as echogenicity, texture descriptors, and geometric measurements6. These features were then fed into classical machine learning classifiers like support vector machines7,8. While pioneering, these methods were inherently brittle; their performance was constrained by a limited representation capacity, a high susceptibility to image noise and artifacts, and an inability to adapt to the vast heterogeneity of plaque morphologies. More recently, the advent of deep learning has ushered in a new era of automated analysis. Frameworks based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and attention mechanisms have demonstrated considerable success in end-to-end plaque classification9. However, these powerful models often operate as ”black boxes.” They produce discrete, categorical labels—such as ”fibrous” or ”calcified”—but offer little in the way of interpretability or contextual understanding10. A clinician is told *what* the model sees, but not *why*. Furthermore, these models typically operate at the image level, failing to address clinical scenarios where a single IVUS frame may contain multiple distinct plaques, each requiring its own specific assessment11.

A critical and largely underexplored gap in this field is the generation of human-interpretable, natural language descriptions that can accompany automated plaque analysis. In modern clinical practice, radiology and cardiology reports are the primary currency for communicating findings and articulating diagnostic reasoning12. These narrative documents are essential for integration with electronic health records13, for informing clinical decision support systems, and for maintaining a clear and unambiguous record of a patient’s condition. Existing automated IVUS analysis pipelines, by outputting only numerical data or discrete labels, fail to integrate into this narrative-driven workflow, creating a disconnect between the computational output and the language of clinical medicine14. To date, no prior work has successfully bridged the gap between raw visual plaque features and their corresponding linguistic representations in a fine-grained, lesion-centered manner.

The recent and transformative success of large-scale vision-language models (VLMs) represents a paradigm shift and offers a unique opportunity to address this challenge15,16. Architectures capable of jointly reasoning over images and text have shown remarkable capabilities in various medical imaging tasks17. However, the direct application of these general-purpose models to the specialized domain of IVUS captioning is fraught with substantial challenges. First, there is a significant domain gap; IVUS images, with their characteristic noise, artifacts, and grayscale circular structure, are fundamentally different from the natural images on which these models are pre-trained2,18,19. Second, clinically meaningful interpretation demands a sharp, lesion-level focus rather than a holistic image summary; a model must be guided to analyze the subtle pathology on the vessel wall, not the catheter artifact at the center. Third, the language output must be precise, domain-specific, and structured according to the rigorous standards of cardiology reporting20,21. A generic description like ”a bright area” is clinically useless; a diagnosis requires specific terminology like ”a hyperechoic region with strong posterior acoustic shadowing.”

To overcome these challenges, we propose PlaqueCap, a novel framework conceived specifically for lesion-centered caption generation in IVUS. PlaqueCap, meticulously designed as a cohesive pipeline of specialized modules, achieves this by synergistically integrating a high-performance segmentation network with a powerful pre-trained VLM. Our approach first employs a hierarchical transformer-based segmentation model to precisely delineate the plaque region, generating an explicit spatial mask. The cornerstone of our framework is the novel Lesion Prompt Injection (LPI) module. This module translates the spatial mask into a learnable prompt embedding and strategically injects it into the VLM’s attention mechanism. This injection mechanism explicitly guides the model to ground its textual generation in the visual features of the identified lesion, ensuring the resulting captions are both pathologically accurate and contextually relevant. By leveraging frozen, large-scale pre-trained encoders for feature extraction and language decoding, and only training the segmentation model and a small set of injection parameters, PlaqueCap achieves high performance with remarkable computational efficiency.

In summary, our primary contributions are fourfold. First, we propose PlaqueCap, the first vision-language framework designed for lesion-centered captioning in IVUS, capable of generating clinically meaningful and explainable natural language descriptions for atherosclerotic plaques. Second, we design a complete pipeline that integrates a hierarchical transformer-based segmentation module for automated, fine-grained extraction of individual plaque regions, setting the stage for localized analysis. Third, We introduce a novel Prompt Mixer and a LPI Module, which work in concert to fuse spatial and visual cues and dynamically guide the language generation process, ensuring the output is grounded in specific pathological evidence. Finally, we conduct extensive quantitative and qualitative evaluations on a curated IVUS dataset, demonstrating that PlaqueCap achieves superior performance compared to existing baselines in both captioning accuracy and clinical interpretability.

Related work has been conducted in several directions.

IVUS has long been considered a gold standard modality for assessing coronary artery disease, providing high-resolution cross-sectional views of arterial lumens and walls. Early computational efforts focused on plaque detection and classification using handcrafted features derived from echogenicity, texture, geometry, or morphological priors22,23. These methods often employed rule-based decision trees, support vector machines, or random forests trained on domain-specific heuristics, and were limited in generalizability due to rigid feature definitions and sensitivity to noise.

With the advent of deep learning, CNNs have been applied to IVUS plaque classification with notable success. For example, Lee et al.24 proposed an end-to-end CNN pipeline for differentiating plaque types in IVUS frames. Other studies explored multi-task architectures that simultaneously performed segmentation and classification24. Despite promising results, most models operated at the image or batch level and were designed to produce discrete labels (e.g., calcified vs. fibrous), lacking lesion-level granularity and interpretability.

Importantly, these methods fall short in clinical applicability due to their ”black-box” nature. They provide minimal justification for predictions, do not align with narrative clinical reports, and are not easily integrated into existing reporting systems.

In addition, generating textual descriptions from medical images has been actively studied as a means to increase explainability and support clinical reporting. Early works such as Jing et al.’s Show, Attend and Tell25 and CX-Report26 applied encoder-decoder architectures to generate radiology reports from chest X-rays. More recent efforts include MIMIC-CXR captioning benchmarks27, reinforcement learning for improved fluency28, and retrieval-augmented models29.

However, most prior work focused on whole-image captioning rather than lesion-centric descriptions. This is a critical limitation, especially in modalities like IVUS, where multiple plaques may coexist in a single image and each has unique clinical relevance. Moreover, existing approaches are often tailored to large-scale natural language corpora (e.g., chest radiograph reports) and do not generalize well to vascular imaging, where visual patterns are more subtle and domain-specific terminology is essential.

Furthermore, the emergence of large-scale VLMs has opened new avenues for cross-modal reasoning in medical contexts. BLIP-230, Flamingo31, and GIT32 are state-of-the-art VLMs that combine frozen visual encoders with powerful language decoders to perform tasks ranging from captioning to visual question answering (VQA). In the biomedical domain, ChatCAD33, and BiomedGPT34 have demonstrated the potential of adapting VLMs to radiology images by fine-tuning on paired image-report datasets or designing radiology-specific prompts.

Yet, these models typically treat the image as a holistic input, neglecting the fine-grained spatial context required for lesion-level understanding. Furthermore, the majority of current VLMs are evaluated on chest X-rays or pathology slides, with little attention given to cardiovascular imaging, and none applied to intravascular modalities. Our work is among the first to bring VLMs into IVUS interpretation, while addressing lesion granularity through modular prompt design.

Finally, Prompt-based learning has emerged as a lightweight and efficient strategy for adapting pre-trained models to downstream tasks35. In vision-language contexts, prompts can be textual, visual, or hybrid—guiding the model toward task-relevant content without fine-tuning all model parameters36. In medical imaging, Med-GRIM37 and Prosfda38 demonstrated improved sample efficiency and generalization by incorporating anatomical priors and clinical templates into prompt design.

Moreover, prompt injection serves as a powerful interpretability tool. By explicitly encoding lesion-level features into the language model’s input, one can observe how different visual attributes affect generated outputs. This aligns with the goals of explainable AI (XAI), as discussed in ref. 10, and opens pathways for transparent decision-making in clinical applications.

Our work builds upon these insights by introducing a novel LPI Module that bridges segmented IVUS plaques and language models. Unlike prior works that rely solely on global visual tokens or fixed text prompts, we dynamically inject lesion embeddings, enabling pathology-aware captioning and lesion-level explanation.

Results

Experimental setup

To rigorously evaluate the performance of our proposed PlaqueCap framework, we designed a comprehensive experimental protocol. Our evaluation is grounded in a publicly available dataset, which we have augmented with expert annotations to suit our specific tasks. We benchmark PlaqueCap against a suite of state-of-the-art VLMs, ensuring a fair comparison by enforcing strict equivalency in data preprocessing, prompt design, and computational budgets to minimize implementation bias.

Dataset

Our experimental foundation is the dataset from the MICCAI 2011 challenge18. This publicly available dataset originally contains 2175 IVUS images from 10 different subjects and includes corresponding ground-truth masks for plaque segmentation. To create a comprehensive benchmark for the nuanced task of lesion-level captioning, we partitioned this dataset into three distinct subsets: IVUS-Lesion-Caps, IVUS-CAD-Rad, and IVUSReportGen. For each of these subsets, we collaborated with experienced cardiologists who manually provided detailed annotations to serve as the gold standard. These annotations include short, descriptive lesion-level captions for the IVUS-Lesion-Caps subset, clinical coronary artery disease radiology (CAD-RADS) scores and semi-structured reports for the IVUS-CAD-Rad subset, and detailed, long-form narrative reports for the IVUSReportGen subset. This meticulous annotation process transformed the original segmentation dataset into a rich, multi-task resource for evaluating clinical report generation. For all experiments, a uniform preprocessing pipeline was applied: each image was resized to a resolution of 224 × 224 pixels and normalized using standard ImageNet statistics to ensure consistency across all models.

Baselines and fair comparison protocol

We compare PlaqueCap against ten representative baseline models that span general-purpose, instruction-tuned, and medical-specific vision-language architectures. The selected baselines include BLIP-230, GIT32, LLaVA39, MiniGPT-440, BioViL-T41, MedCLIP42, Caption-MedIC43, PMC-VQA44, PathoCap45, and GPT-4V46. To ensure that the performance differences are attributable to model architecture rather than implementation details, we established a strict protocol for fair comparison. All models were provided with the exact same preprocessed image inputs. For the captioning task, this meant using the lesion patches extracted via our segmentation module, thereby ensuring that all models focused on the same lesion-centric information. For models requiring a text prompt, such as LLaVA and GPT-4V, a standardized and neutral prompt, for instance, ”Describe the plaque in the IVUS image,” was used to eliminate prompt engineering as a confounding variable. Furthermore, we equalized the training budget across all models. Each baseline was finetuned on our datasets using the same AdamW optimizer, a comparable learning rate schedule, and for a similar number of epochs or until convergence was observed on a held-out validation set. This controlled computational budget prevents any model from gaining an advantage due to extended training. For architectures not natively designed for direct fine-tuning, we employed standard and efficient adaptation techniques like adapter tuning to ensure a fair and rigorous comparison.

Implementation details

Our PlaqueCap model was implemented using the PyTorch framework and trained on four NVIDIA A100 GPUs with 40 GB of memory. The framework is built upon a frozen BLIP-2 backbone, with only the lesion prompt encoder and the Q-former’s prompt injection layers being trainable. This parameter-efficient approach significantly reduces computational overhead. We utilized the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of 5 × 10−5 and a cosine annealing schedule. The model was trained with a batch size of 64 for 20 epochs, with an early stopping mechanism monitored on the validation set’s CIDEr score to prevent overfitting. To ensure the robustness and reproducibility of our results, all experiments, for both our model and the baselines, were conducted using three different random seeds, and we report the average performance metrics. The official open-source implementations were used for all baseline models, and they were adapted to the task following the fair comparison protocol described previously.

Quantitative evaluation against baselines

Captioning performance evaluation

To situate the performance of PlaqueCap within the current landscape of VLMs, we conducted a comprehensive quantitative comparison against ten strong baselines, which include general-purpose, instruction-tuned, and domain-adapted architectures. In adherence to a fair comparison protocol, all models were trained or adapted using identical lesion-centered image patches and were evaluated on four standard language generation metrics: BLEU-4, CIDEr, METEOR, and ROUGE-L. The performance assessment was carried out across our three curated datasets. On the IVUS-Lesion-Caps dataset, which features short, descriptive captions focused on specific lesion attributes, PlaqueCap demonstrates a commanding lead, achieving the highest scores across all four metrics with a BLEU-4 of 33.8, CIDEr of 82.4, METEOR of 24.6, and ROUGE-L of 50.5, as detailed in Table 1. This represents a significant margin over the strongest generalist baseline, GPT-4V, and even larger gains over other prominent models like BLIP-2 and LLaVA, underscoring its superior ability to capture the fine-grained lexical and stylistic nuances of clinical descriptions.

This strong performance is maintained on the more challenging datasets that require deeper clinical and contextual understanding. The IVUS-CAD-Rad dataset, containing clinically standardized labels and varied free-text summaries, saw PlaqueCap again leading all competitors with a BLEU-4 score of 30.9 and a CIDEr of 79.7 (Table 2 Best results are bold) Similarly, on the IVUSReportGen dataset, which consists of long-form narrative reports demanding high narrative coherence, PlaqueCap achieved top scores of 29.8 in BLEU-4 and 77.0 in CIDEr (Table 3). While many baseline models tended to produce generic or occasionally hallucinated phrases, PlaqueCap’s architecture, particularly its explicit lesion-token injection, ensures that the generated text remains firmly grounded in the visual pathology. These consistent results across diverse datasets validate the central hypothesis of this work. Generic VLMs, despite their power, underperform due to a lack of specific guidance, while existing medical-specific models, though helpful, lack the necessary architectural mechanism for lesion-centric reasoning. PlaqueCap’s integration of visual prompt tokens derived from lesion patches into the generation pipeline proves to be the critical factor in significantly improving the granularity, precision, and clinical coherence of the generated medical text.

Segmentation performance comparison

Beyond captioning, the accuracy of the underlying plaque segmentation is fundamental to the performance of our lesion-centered framework. We therefore conducted a dedicated evaluation of our hierarchical transformer-based segmentation module, comparing it against two widely recognized and powerful baselines in medical image segmentation: U-Net and the transformer-based UNETR. The comparison was performed on the test split of our dataset, using the dice similarity coefficient (DSC) and mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) as the standard metrics for evaluating spatial overlap and agreement with the ground-truth annotations.

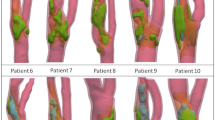

The quantitative results are summarized in Table 4. Our model achieves a DSC of 0.925 and a mIoU of 0.861, outperforming established baselines including U-Net, Attention U-Net, TransUNet, and UNETR. This indicates that our segmentation architecture is better suited for capturing the specific morphological features of atherosclerotic plaques in IVUS images. The superior performance can be attributed to the hierarchical encoder’s ability to effectively model both local texture and global context, which is critical for delineating the often ambiguous and irregular boundaries of plaques.

These quantitative findings are further substantiated by the visual evidence presented in Fig. 1. Across a diverse range of representative cases (Rows A-E), our model’s segmentation predictions (red overlay) demonstrate a consistently higher fidelity to the ground-truth (blue overlay) compared to the baseline methods. Notably, in cases with faint edges (Row A) or complex, non-convex shapes (Row C and E), our model produces smoother and more accurate contours, whereas the baseline models occasionally exhibit over- or under-segmentation. This visual superiority confirms our model’s enhanced robustness and precision in localizing plaque regions, providing a reliable foundation for the subsequent lesion-aware captioning task.

From left to right: original image (Image), ground-truth (GT), our model’s prediction (Ours), U-Net’s prediction, and UNETR's prediction. Our model’s segmentation (red overlay) aligns more closely with the ground-truth (blue overlay) across various plaque morphologies. Rows (A−E) show representative cases with different plaque morphologies.

Ablation studies

To systematically dissect the PlaqueCap framework and quantify the contribution of its core components, we performed a series of ablation studies on the IVUS-Lesion-Caps dataset. The results, summarized in Table 5 and Fig. 2, reveal the indispensable role of each architectural choice. The full PlaqueCap model serves as our performance ceiling, achieving a CIDEr score of 82.4. The most significant performance degradation was observed upon removing the segmentation guidance entirely, forcing the model to operate on the whole image without any spatial priors. This resulted in a CIDEr score of 70.3, a 12.1-point drop, which unequivocally demonstrates that a lesion-centered approach is paramount for generating accurate and relevant captions. Removing the LPI module, which prevents the Q-Former from being conditioned on any lesion-specific information, also caused a severe performance drop to a CIDEr of 74.1. This highlights the need for explicit guidance in the vision-language feature extraction process.

Further studies interrogated the more nuanced components of our design. Bypassing the Prompt Mixer module and instead feeding the raw spatial prompt embeddings directly to the LPI module resulted in a CIDEr of 77.0. This confirms the value of the mixer’s role in fusing spatial cues with global visual context to create a more informative and holistic prompt. We also tested an alternative to our prompt injection strategy by using a conventional global pooling baseline, where features within the lesion mask are averaged into a single vector. This approach yielded a CIDEr of 75.8, reinforcing that our token-level injection preserves critical spatial details that are lost during pooling. Finally, to validate our choice of the LoRA-based injection mechanism, we replaced it with a simpler additive method where the prompt embedding is directly added to the image feature tokens. This resulted in a CIDEr of 79.5, showing that while simpler methods are beneficial, the adaptive, multiplicative modulation offered by LoRA is more effective at integrating the prompt’s guidance. Collectively, these results confirm that the synergistic interplay between segmentation guidance, prompt fusion, and sophisticated injection is crucial to PlaqueCap’s success.

Qualitative analysis of generated captions

While quantitative metrics provide a measure of overall performance, a qualitative analysis is essential to assess the clinical relevance, descriptive accuracy, and interpretability of the captions generated by PlaqueCap. To this end, we present a series of case studies in Fig. 3, where the outputs of our model are juxtaposed with those from a representative baseline model across four distinct and common types of atherosclerotic plaques. This comparative visualization highlights the significant leap in descriptive power and clinical utility offered by our lesion-aware approach.

The analysis reveals a stark contrast in the quality and detail of the generated text. For the lipid-rich plaque, the baseline model produces a generic observation about ”thickening on the upper wall,” failing to identify the plaque type or its key sonographic features. In contrast, PlaqueCap generates a clinically precise report, correctly identifying it as a ”circumferential, lipid-rich plaque” and describing its ” homogeneous and distinctly hypoechoic appearance,” which are crucial diagnostic markers. A similar gap is evident in the mixed plaque example. The baseline offers a vague description of ”abnormal density,” whereas PlaqueCap provides a remarkably detailed and localized analysis, specifying the plaque’s position (”at 10-3 o’clock”), its heterogeneous composition (”bright speckled echoes... beside a darker, non-shadowing region”), and even inferring the constituent tissue types consistent with calcified and lipid/soft components.

This superior performance is further exemplified in the calcified and fibrous plaque cases. For the calcified plaque, the baseline’s description is rudimentary, merely noting ”bright white areas.” PlaqueCap, however, produces an expert-level interpretation, correctly identifying the ”circumferential” involvement and citing the two definitive radiological signs: a ”distinct hyperechoic signal” and ”strong posterior acoustic shadowing.” For the fibrous plaque, the baseline fails to provide any meaningful pathological insight. PlaqueCap, on the other hand, delivers a comprehensive diagnosis, including the location (”4–9 o’clock”), echotexture (”homogeneous intermediate echogenicity”), the critical negative finding of ”no posterior shadowing,” and the specific ”crescent-shaped, wall-adherent morphology.” These case studies collectively demonstrate that PlaqueCap does not merely describe an image in general terms; it interprets it, grounding its narrative in specific, clinically significant visual evidence and leveraging a deep, domain-specific vocabulary. This is a direct result of our LPI mechanism, which forces the language model to reason about localized pathologies, thereby bridging the gap between raw pixels and expert-level clinical reporting.

Comparison with human expert reports

While comparisons against other automated methods are informative, the ultimate benchmark for a clinical report generation system is its ability to approximate the gold standard: reports authored by human experts. To assess this clinical faithfulness, we conducted a rigorous two-part evaluation designed to measure both the linguistic similarity and the diagnostic accuracy of the reports generated by PlaqueCap against those written by experienced cardiologists for the same IVUS images. This dual-pronged approach allows us to quantify not only if the model’s output *sounds* like an expert report but also if it *conveys* the correct clinical meaning.

First, we evaluated the token-level and semantic similarity between the generated and expert reports using a suite of standard natural language processing metrics. As detailed in Table 6, PlaqueCap consistently and significantly outperforms all baseline models across every metric. It achieves the highest scores in n-gram-based metrics like BLEU-4 (0.396) and ROUGE-L (0.522), indicating a superior structural and lexical overlap with the expert reports. More importantly, its leading scores in semantically-aware metrics, such as a CIDEr of 1.33 and a BERTScore of 0.854, demonstrate that the generated text captures a deeper contextual and semantic alignment. This suggests that PlaqueCap has successfully learned the characteristic phrasing, vocabulary, and narrative structure that cardiologists employ, producing reports that are linguistically sophisticated and stylistically authentic.

Recognizing that linguistic fluency does not guarantee diagnostic accuracy, our second evaluation focused on clinical correctness. Standard NLP metrics can reward outputs that are plausible but medically imprecise. To address this, we curated a lexicon of critical, clinically relevant pathological terms (e.g., “luminal narrowing,” “fibrotic cap,” “calcified core”) based on established cardiology guidelines and computed the F1 score for their correct usage in the generated reports. As shown in Table 7, PlaqueCap achieves a pathology-term F1 score of 0.781, substantially surpassing all baselines. This result confirms the model’s enhanced capability to not only detect but also correctly name specific, diagnostically critical findings. To supplement this automated analysis, we engaged a panel of expert cardiologists to rate the generated reports on a 5-point Likert scale based on their overall accuracy, clarity, and completeness. PlaqueCap received an outstanding average expert alignment score of 4.4 out of 5. This high rating validates that domain experts perceive the reports as clinically reliable, coherent, and highly useful, confirming the effectiveness of our lesion-aware prompting and medical language modeling pipeline. Together, these findings affirm that PlaqueCap can produce reports that are not only textually aligned but are also medically faithful and readily interpretable by clinicians.

Discussion

Our quantitative and qualitative results demonstrate that PlaqueCap represents a significant advancement in the automated interpretation of IVUS imagery. By synergizing a high-fidelity segmentation module with a sophisticated lesion-aware language generation pipeline, our framework produces reports that are not only textually accurate but also clinically insightful. However, like any deep learning system, our model has limitations that warrant discussion and that illuminate promising avenues for future research.

While PlaqueCap’s segmentation module generally performs with high accuracy, we have identified specific scenarios where its predictions can deviate from the expert-annotated ground truth. Figure 4 illustrates two such representative cases. In these examples, the model correctly localizes the plaque and captures its general morphology, but the predicted mask (red) is smoother and slightly smaller than the ground truth (blue), particularly around the finest edges of the lesion. We hypothesize that these discrepancies stem from a combination of factors inherent to both the data and the model. IVUS images are often characterized by low contrast and imaging artifacts, which can render plaque boundaries, especially for soft or mixed types, inherently ambiguous. The model, in its effort to learn a generalizable representation, may develop a bias towards producing more regularized and smooth contours, causing it to miss the subtle, feathery edges that a human expert might trace. Furthermore, highly irregular or thin plaque morphologies may be underrepresented in the training corpus, leading the model to default to a more prototypical shape in such instances.

These limitations, rather than detracting from the model’s current utility, provide a clear roadmap for future enhancements. To address the challenge of ambiguous boundaries and rare morphologies, future work could focus on developing uncertainty-aware segmentation models. Such models could produce not only a segmentation mask but also a corresponding uncertainty map, which would highlight regions of low confidence for clinical review, thereby increasing trust and safety. Moreover, the integration of spatio-temporal information could significantly improve performance. Since IVUS is acquired as a continuous pullback sequence, a model that processes the entire video, rather than isolated frames, could leverage contextual information from adjacent slices to enforce consistency and improve boundary delineation. Finally, exploring advanced data augmentation techniques, such as generative adversarial networks (GANs) or diffusion models, could allow us to synthesize a greater diversity of realistic training data, particularly for rare plaque types, thus improving the model’s overall robustness and generalization capabilities. By addressing these areas, we can continue to advance the development of AI tools that are not only powerful but also reliable partners in clinical decision-making.

In this work, we addressed the critical need for interpretable and clinically aligned analysis of atherosclerotic plaques in IVUS imaging. Conventional computational methods often function as ”black boxes,” providing classifications without the nuanced, descriptive context required for robust clinical decision-making. To bridge this gap, we introduced PlaqueCap, a novel, lesion-centered vision-language framework designed to generate fine-grained, radiology-style narrative reports directly from IVUS images.

Our approach integrates a high-performance hierarchical transformer for precise plaque segmentation with a powerful, pre-trained VLM based on the BLIP-2 architecture. The core innovation of our framework is the LPI module, which dynamically infuses pathology-specific visual semantics into the language generation process. This mechanism ensures that the resulting descriptions are not only globally coherent but are also meticulously grounded in the specific features of the identified lesion. Through extensive experiments, we have demonstrated PlaqueCap’s superiority over a wide range of state-of-the-art baseline models. Our framework consistently achieved higher scores on all standard quantitative metrics across three distinct datasets and showed superior alignment with reports written by human experts, both in linguistic style and in the correct usage of critical pathological terminology. Furthermore, ablation studies systematically validated the significant contribution of each component, particularly the lesion-aware prompt injection design.

PlaqueCap represents a significant step toward developing more explainable, multimodal AI systems for cardiovascular imaging that can communicate findings in a language familiar to clinicians. Future work will focus on extending this framework to incorporate temporal context from IVUS pullback sequences, adapting it to other intravascular modalities such as optical coherence tomography (OCT), and ultimately, deploying it in clinical workflows to aid in automated reporting and decision support.

Methods

In this section, we present the detailed architecture of PlaqueCap, our proposed framework for lesion-centered captioning of atherosclerotic plaques in IVUS images. The overall architecture is designed to first precisely segment the plaque region and then generate a clinically relevant textual description by injecting lesion-specific information into a powerful VLM.

Overall architecture

The overall pipeline of PlaqueCap is illustrated in Fig. 5. The framework operates by processing an input IVUS image through two main parallel streams. The first stream utilizes a frozen image encoder, derived from the segment anything model (SAM), to extract a rich set of high-level visual features, denoted as ISAM. This leverages the powerful representation capabilities of SAM, which has been pre-trained on a massive dataset of diverse images. The second stream employs a trainable segmentation model, specifically designed for plaque localization, to predict a binary lesion mask UMask and its corresponding bounding box UBox. These spatial outputs from the segmentation model serve as explicit prompts that guide the subsequent caption generation process.

The generated spatial prompts, UMask and UBox, are then converted into embedding representations, PSAM, by a frozen prompt encoder, also from the SAM architecture. To effectively fuse the visual and spatial information, we introduce a trainable Prompt Mixer module. This module integrates the global visual features ISAM and the spatial prompt embeddings PSAM to produce a unified, lesion-aware prompt embedding, PMix. Finally, this mixed prompt PMix, along with other visual features, is fed into the core of our framework: the LPI module. The LPI module consists of a Prompt-Aware Querying Transformer (Q-Former) and a frozen Large Language Model (LLM) decoder. By injecting the lesion-specific prompt PMix into the Q-Former, the module generates a highly contextualized and accurate textual caption describing the plaque’s characteristics. This parameter-efficient design, with a mix of frozen and trainable components, allows PlaqueCap to effectively adapt large pre-trained models for the specific task of IVUS image captioning.

Hierarchical transformer for plaque segmentation

Accurate lesion segmentation is a critical prerequisite for generating precise captions. To this end, we employ a powerful segmentation network with a hierarchical transformer architecture, inspired by SegFormer, as depicted in Fig. 6. This model consists of a hierarchical transformer encoder and a lightweight MLP decoder head.

The encoder processes an input image \(I\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{H\times W\times C}\) by first dividing it into a sequence of non-overlapping patches. These patches are then linearly embedded to form patch embeddings. The sequence of embeddings is fed through a series of four transformer blocks. Each block is composed of an efficient self-attention layer and a Mix-FeedForward Network (Mix-FFN). A key feature of this architecture is its ability to produce a hierarchy of feature maps at different scales without requiring positional encodings. At each stage i ∈ {1, 2, 3, 4}, the transformer block outputs a feature map \({F}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{\frac{H}{{2}^{i+1}}\times \frac{W}{{2}^{i+1}}\times {C}_{i}}\). This multi-scale feature hierarchy allows the model to capture both fine-grained local details and broader contextual information, which is essential for identifying plaques with varying morphologies.

The lightweight decoder then aggregates these multi-scale features to generate the final segmentation mask. First, features from all four levels {F1, F2, F3, F4} are passed through separate MLP layers to unify their channel dimensions. Subsequently, they are upsampled to a uniform resolution (\(\frac{H}{4}\times \frac{W}{4}\)) and concatenated. The aggregated feature map, Fagg, is then processed by a final MLP layer to predict the segmentation mask \({U}_{Mask}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{H\times W\times 1}\). The process can be formulated as:

The bounding box UBox is then algorithmically derived from the contours of the predicted binary mask UMask.

LPI module

The core of our captioning pipeline is the LPI module, which is detailed in Fig. 7. This module is responsible for translating the lesion-focused visual features into a coherent natural language description. It comprises a novel Prompt-Aware Q-Former and a frozen LLM decoder.

The Q-Former serves as a bridge between the frozen image encoder and the frozen LLM decoder. It employs a set of N learnable query embeddings, Qlearn, which interact with the image features ISAM through a series of cross-attention layers to extract visual information pertinent to the captioning task. The central innovation of our work is the dynamic injection of lesion-specific guidance into this process. The mixed prompt embedding PMix, which encapsulates both spatial and semantic information about the plaque, is injected into each cross-attention block of the Q-Former.

Specifically, the injection is performed by modulating the Key (K) and Value (V) projection matrices within the cross-attention mechanism. We employ a parameter-efficient Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) technique for this purpose. For a given cross-attention layer, the Key and Value vectors are computed not only from the image features ISAM but are also influenced by the lesion prompt PMix. Let WK and WV be the original key and value projection weights, and let \({W}_{K}^{{{\rm{LoRA}}}}\) and \({W}_{V}^{{{\rm{LoRA}}}}\) be the trainable low-rank adaptation matrices. The modulated Key \({K}^{{\prime} }\) and Value \({V}^{{\prime} }\) are computed as:

The output of the cross-attention layer is then given by \(\,{\mbox{Attention}}\,({Q}_{learn}{W}_{Q},{K}^{{\prime} },{V}^{{\prime} })\). This injection mechanism forces the Q-Former to focus its attention on the visual features corresponding to the segmented lesion, guided by PMix. The resulting output from the Q-Former is a sequence of feature vectors that acts as a soft prompt prefix. This prefix is then passed to the frozen LLM decoder, which autoregressively generates the final caption, ensuring that the description is grounded in the specific pathology identified in the image.

Training objective

The PlaqueCap framework is trained in an end-to-end manner, optimizing both the segmentation and captioning tasks simultaneously. The total loss function Ltotal is a weighted sum of a segmentation loss Lseg and a captioning loss Lcap. The segmentation loss is a combination of binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss and Dice loss to effectively handle potential imbalances between foreground and background pixels.

where YMask is the ground-truth segmentation mask, and λbce and λdice are weighting coefficients. The captioning loss is the standard cross-entropy loss, which maximizes the likelihood of the ground-truth caption Ycap given the input image I.

where yt is the t-th token in the caption. The total loss is thus defined as:

where α is a hyperparameter balancing the two tasks. During training, only the segmentation model, the Prompt Mixer, the Q-Former, and the LoRA weights are updated, while the powerful SAM encoders and the LLM decoder remain frozen. This strategy ensures efficient adaptation of large models to the specific domain of IVUS plaque analysis.

Inference pipeline

During the inference phase, the fully trained PlaqueCap model generates a descriptive caption for a given unseen IVUS image in a sequential, feed-forward manner. The process begins with the input IVUS image being simultaneously fed into the trained hierarchical transformer-based segmentation model and the frozen SAM image encoder. The segmentation model predicts the lesion mask UMask and its corresponding bounding box UBox, precisely localizing the plaque. Concurrently, the SAM image encoder extracts the high-level visual feature representation ISAM. The predicted spatial prompts, UMask and UBox, are then processed by the frozen SAM prompt encoder to yield the prompt embeddings PSAM. Subsequently, the trainable Prompt Mixer module takes both ISAM and PSAM as input to compute the final lesion-aware mixed prompt, PMix. This prompt is then injected into the Prompt-Aware Q-Former within the LPI module. The Q-Former processes the image features, conditioned by the injected prompt, to produce a sequence of output embeddings that encapsulate the specific characteristics of the identified lesion. Finally, this sequence of embeddings is used as a soft prompt that is prepended to the input of the frozen LLM decoder. The decoder then autoregressively generates the final text caption token by token, often employing a decoding strategy such as beam search to enhance the fluency and coherence of the output. The entire process, from image input to text output, is fully automated and does not require any manual intervention.

This study was conducted using publicly available, fully anonymized IVUS datasets. No new data involving human participants were collected or processed; therefore, approval from an ethics committee and informed consent for publication were not required.

Data availability

This research does not involve any proprietary materials or clinical devices. All datasets used in this study are publicly available: https://github.com/Kulbear/ivus-segmentation-icsm2018. The implementation of PlaqueCap will be made available upon reasonable request or open-sourced on GitHub after publication. Code for lesion segmentation, prompt injection, and report generation is reproducible and based on standard PyTorch pipelines.

Code availability

The implementation of PlaqueCap will be made available upon reasonable request or open-sourced on GitHub after publication. Code for lesion segmentation, prompt injection, and report generation is reproducible and based on standard PyTorch pipelines.

References

Mensah, G. A. et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risks, 1990-2022. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 82, 2350–2473 (2023).

Nissen, S. E. & Yock, P. Intravascular ultrasound: novel pathophysiological insights and current clinical applications. Circulation 103, 604–616 (2001).

Otsuka, F., Joner, M., Prati, F., Virmani, R. & Narula, J. Clinical classification of plaque morphology in coronary disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 11, 379–389 (2014).

Loizou, C. P., Pattichis, C. S., Pantziaris, M., Kyriacou, E. & Nicolaides, A. Texture feature variability in ultrasound video of the atherosclerotic carotid plaque. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 5, 1–9 (2017).

Bai, W. et al. Automated cardiovascular magnetic resonance image analysis with fully convolutional networks. J. Cardiovas. Magn. Reson. 20, 65 (2018).

Hao, J. et al. PLUS: Plug-and-play enhanced liver lesion diagnosis model on non-contrast CT scans. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. 461-471 (2025).

O’Malley, S. M., Naghavi, M. & Kakadiaris, I. A. One-class acoustic characterization applied to blood detection in IVUS. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. 4791 LNCS, 202 – 209 (2007).

Alberti, M. et al. Automatic bifurcation detection in coronary ivus sequences. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 59, 1022–1031 (2012).

Ma, R., Hao, J., Ding, J., Yu, H. & Xia, S. Automatic measurement and reference values setting of intracranial cerebrospinal fluid volume: a large-scale analysis of computed tomography images. Quant. Imag. Med. Surg. 15, 6185 (2025).

Roscher, R., Bohn, B., Duarte, M. F. & Garcke, J. Explainable machine learning for scientific insights and discoveries. IEEE Access 8, 42200–42216 (2020).

Tian, C. et al. Multi-class plaque segmentation in intravascular ultrasound via inter-frame feature fusion and contrast feature extraction. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 96, 106610 (2024).

Wilcox, J. R. The written radiology report. Applied Radiology 35 https://geiselmed.dartmouth.edu/radiology/wp-content/uploads/sites/47/2021/07/The-written-radiology-report.pdf (2006).

Martínez-Salvador, B., Marcos, M., Mañas, A., Maldonado, J. A. & Robles, M. Using snomed ct expression constraints to bridge the gap between clinical decision-support systems and electronic health records. In Exploring Complexity in Health: An Interdisciplinary Systems Approach, 504–508 (2016).

Kumari, V. et al. Transformer and attention-based architectures for segmentation of coronary arterial walls in intravascular ultrasound: a narrative review. Diagnostics 15, 848 (2025).

Sun, Z. et al. Visual-language foundation models in medical imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical and empirical studies. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 268, 108870 (2025).

Tu, T. et al. Collaboration between clinicians and vision–language models in radiology report generation. Nat. Med. 31, 599–608 (2025).

Hartsock, I. & Rasool, G. Vision-language models for medical report generation and visual question answering: a review. Front. Artif. Intell. 7, 1430984 (2024).

Balocco, S. et al. Standardized evaluation methodology and reference database for evaluating IVUS image segmentation. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 38, 70–90 (2014).

Zacharatos, H., Hassan, A. E. & Qureshi, A. I. Intravascular ultrasound: principles and cerebrovascular applications. Ajnr. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 31, 586–597 (2010).

Mintz, G. S. et al. American college of cardiology clinical expert consensus document on standards for acquisition, measurement and reporting of intravascular ultrasound studies (ivus). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 37, 1478–1492 (2001).

Saito, Y. et al. Cvit 2025 clinical expert consensus document on intravascular ultrasound. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Ther. 40, 211–225 (2025).

Katouzian, A. et al. A state-of-the-art review on segmentation algorithms in intravascular ultrasound (ivus) images. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 16, 823–837 (2012).

Jun, T. J. et al. Automatic detection of vulnerable plaque in intravascular ultrasound using machine learning. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 57, 863–876 (2019).

Bajaj, R. et al. Examination of the performance of machine learning-based automated coronary plaque characterization by near-infrared spectroscopy–intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography with histology. Eur. Heart J. Digit. Health 6, 359–371 (2025).

Jing, B., Xie, P. & Xing, E. On the automatic generation of medical imaging reports. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the ACL. https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.08195 (2018).

Serra, F. D., Wang, C., Deligianni, F., Dalton, J. & O’Neil, A. Q. Controllable chest x-ray report generation from longitudinal representations. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.05881 (2023).

Boag, W. et al. Baselines for chest x-ray report generation. In Machine learning for health workshop, 126–140 (PMLR, 2020).

Xiong, Y., Du, B. & Yan, P. Reinforced transformer for medical image captioning. In International workshop on machine learning in medical imaging, 673–680 (Springer, 2019).

Liu, F., Ge, S., Wu, X. & Zou, Y. Competence-based multimodal curriculum learning for medical report generation. In Proceeding ACL/IJCNLP. 3028–3040 (2021).

Li, J., Li, D., Savarese, S. & Hoi, S. Blip-2: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training with frozen image encoders and large language models. In International conference on machine learning, 19730–19742 (PMLR, 2023).

Alayrac, J.-B. et al. Flamingo: a visual language model for few-shot learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 23716–23736 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Git: a generative image-to-text transformer for vision and language. In Proceeding International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Interactive computer-aided diagnosis on medical image using large language models. Commun. Eng. 3, 133 (2024).

Zhang, K. et al. Biomedgpt: a unified and generalist biomedical generative pre-trained transformer for vision, language, and multimodal tasks. arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.17100 (2023).

Yang, H. et al. Prompt mechanisms in medical imaging: a comprehensive survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.01055 (2025).

Zhao, Y., Prasad, M. & Braytee, A. Dualprompt-medcap: a dual-prompt enhanced approach for medical image captioning. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 205−215 (2025).

Madavan, R. R. et al. Med-grim: enhanced zero-shot medical vqa using prompt-embedded multimodal graph rag. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.06496 (2025).

Hu, S., Liao, Z. & Xia, Y. Prosfda: prompt learning based source-free domain adaptation for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.11514 (2022).

Liu, H., Li, C., Wu, Q. & Lee, Y. J. Visual instruction tuning. Adv. neural Inf. Process. Syst. 36, 34892–34916 (2023).

Zhu, D. et al. Minigpt-4: enhancing vision-language understanding with advanced large language models. In Proceeding International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2024).

Bannur, S. et al. Learning to exploit temporal structure for biomedical vision-language processing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 15016–15027 (2023).

Wang, Z., Wu, Z., Agarwal, D. & Sun, J. Medclip: contrastive learning from unpaired medical images and text. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Vol 2022, 3876 (2022).

Rückert, J. et al. Overview of imageclefmedical 2022–caption prediction and concept detection. In CEUR Workshop Proceedings, vol. 3180, 1294–1307 (CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Pmc-vqa: visual instruction tuning for medical visual question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.10415 (2023).

Zhang, R., Weber, C., Grossman, R. & Khan, A. A. Evaluating and interpreting caption prediction for histopathology images. In Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference, 418–435 (PMLR, 2020).

Achiam, J. et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 (2023).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015, vol. 9351 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 234–241 (Springer, Cham, 2015).

Chen, J. et al. Transunet: transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. In Proceeding. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) (2021).

Oktay, O. et al. Attention u-net: learning where to look for the pancreas. In Proceeding Medical Imaging with Deep Learning (MIDL) (2018).

Hatamizadeh, A. et al. Unetr: transformers for 3d medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 1748–1758 (IEEE, 2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M762614), the 2023-SZZ Key Specialized Construction Project in Cardiology Department of Zhejiang Province (2023-SZZ), the Ningbo Key Research and Development Program (2024Z232), the Medical and Health Science and Technology Projects of Zhejiang Province (2024KY281), and the Medical Science and Technology Innovation Project of Xuzhou Municipal Health Commission (XWKYHT2024112).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Y. and S.N. had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis (Validation, Formal analysis). S.N. and W.Z. contributed to the conception of the research and the development of the study design (Conceptualization, Methodology), and participated in acquiring funding to support the project (Funding acquisition). W.Z. and L.Y. were responsible for data acquisition, curation, and investigation of the research questions (Investigation, Data curation), and provided necessary materials, instruments, and technical resources (Resources). They also contributed to the development and implementation of analytical procedures, including the use and adaptation of relevant software tools (Software). W.J. prepared the initial draft of the manuscript and contributed to data visualization for the presentation of results (writing–original draft, visualization). Z.Y. and S.N. supervised the overall progress of the study and managed coordination among the research team (supervision and project administration). All authors participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript critically for important intellectual content (writing–review & editing) and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, G., Hou, M., Yang, X. et al. PlaqueCap: lesion-centered captioning of atherosclerotic plaques in intravascular ultrasound using vision-language models and prompt injection. npj Digit. Med. 8, 702 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02044-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02044-9