Abstract

Delirium affects 50% of hospitalized older adults and 80% of ICU patients, yet detection rates are as low as 20–30% with traditional methods. Natural language processing (NLP) offers potential for automated detection from clinical notes. We systematically reviewed NLP techniques, searching eight databases through March 2025. From 912 records, 13 studies met inclusion criteria, analyzing over 450,000 patients. Studies employed rule-based methods (38%), machine learning (31%), deep learning (15%), topic modeling (8%), and semi-supervised learning (8%). Sensitivity ranged from 28.5% to 99.1%, with transformer models achieving the highest performance (AUROC 0.984). However, 61.5% of studies showed high risk of bias due to inadequate validation practices. Only one study conducted external validation, and none evaluated prospective implementation or patient outcomes. Critical reporting gaps included complete absence of fairness considerations, missing data handling procedures, and implementation guidance across all studies. While transformer-based models demonstrated superior performance, significant barriers remain before clinical deployment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Delirium represents a severe neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by acute onset and fluctuating disturbances in attention, awareness, and cognition, affecting up to 50% of hospitalized older adults and 80% of mechanically ventilated intensive care unit (ICU) patients1,2. Despite its high prevalence and association with adverse outcomes including increased mortality, prolonged hospitalization, functional decline, and long-term cognitive impairment, delirium remains significantly underdiagnosed in clinical practice, with detection rates as low as 20–30% using traditional assessment methods3,4.

The under recognition of delirium stems from multiple factors: its fluctuating nature, overlapping symptoms with dementia, variable clinical presentations, and the time-intensive nature of standardized assessment tools such as the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) or the Delirium Rating Scale5. While these validated instruments demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity when properly administered, their implementation requires trained personnel and dedicated assessment time, creating barriers to routine use in busy clinical environments6.

Electronic health records (EHRs) contain rich, unstructured clinical documentation that may capture subtle signs and symptoms of delirium not formally coded in structured data fields. Clinical notes from physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals often document behavioral disturbances, cognitive changes, and fluctuating mental status that could indicate delirium7. Natural language processing (NLP) techniques offer the potential to automatically extract and analyze these narrative descriptions, enabling scalable delirium detection without additional clinical burden8.

Recent studies have identified significant improvements in delirium detection methodologies, with advances in digital biomarkers and machine learning approaches showing promise for clinical implementation9,10. Contemporary studies utilizing standardized assessment protocols demonstrate that delirium prevalence may be higher than previously reported, particularly in acute care settings where comprehensive screening is systematically applied11.

Furthermore, recent advances in NLP, particularly deep learning approaches and transformer architectures, have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in clinical text analysis12. These techniques can process vast amounts of unstructured data, identify complex patterns, and adapt to varied clinical documentation styles.

Previous reviews have examined digital biomarkers for delirium or broader applications of NLP in psychiatry, but none have specifically synthesized the evidence on NLP techniques for delirium detection from clinical notes13,14,15. Chart-based review processes have been implemented to detect and label delirium for training models in various clinical contexts. Ida, et al.9 developed serum biomarker approaches for predicting postoperative delirium following abdominal surgery, while Oosterhoff et al.10 created clinical prediction models using machine learning algorithms for geriatric hip fracture patients. Nagata et al.11 demonstrated the development of postoperative delirium prediction models in cardiovascular surgery patients using machine learning algorithms. These studies highlight the potential of structured data approaches, but current detection tools face significant limitations including low sensitivity rates and reliance on time-intensive manual assessments.

NLP approaches offer superior performance potential compared to traditional structured data methods. NLP techniques can capture nuanced clinical descriptions that may be missed by formal coding systems, process vast amounts of unstructured documentation automatically, and identify subtle linguistic patterns indicative of delirium symptoms. The ability to analyze free-text clinical notes enables the detection of delirium cases that might not be formally coded, addressing the significant undercoding bias present in administrative data systems.

Given the substantial clinical burden of undetected delirium and the rapid advancement of NLP technologies, a comprehensive synthesis of current approaches is urgently needed to guide both researchers and clinicians toward evidence-based implementation strategies. While previous reviews have examined digital biomarkers for delirium prediction and broader applications of NLP in psychiatry16,17,18,19, none have specifically evaluated the technical performance, methodological quality, and clinical readiness of NLP systems designed to detect delirium from narrative clinical documentation. This gap is particularly critical as healthcare systems increasingly seek automated solutions to address workforce limitations and improve patient safety outcomes.

However, NLP in clinical contexts faces several fundamental challenges that are particularly pronounced in delirium detection. The heterogeneous terminology used to describe delirium symptoms, the need to capture temporal fluctuations, and the importance of distinguishing delirium from other neurocognitive conditions require specialized approaches20. Negation detection represents a critical technical hurdle, as clinical notes frequently document the absence of symptoms (e.g., “patient denies confusion,” “no agitation observed”), and failure to properly handle negated statements can substantially degrade model performance21. Temporal fluctuation poses another significant challenge, as delirium symptoms characteristically wax and wane throughout the day, requiring NLP systems to capture and interpret time-stamped documentation patterns rather than static symptom presence22. Additionally, semantic drift, which is the evolution of clinical terminology and documentation practices over time, can cause model performance degradation when systems trained on historical data are applied to contemporary clinical notes23.

This systematic review aims to: (1) comprehensively characterize NLP techniques and their technical specifications for delirium detection from clinical notes, (2) systematically assess diagnostic accuracy and validation methodologies across studies, (3) evaluate methodological quality and risk of bias using contemporary AI-specific assessment tools, (4) identify critical reporting gaps that limit reproducibility and clinical translation, and (5) provide evidence-based recommendations for future research priorities and clinical implementation pathways.

Results

Study Selection

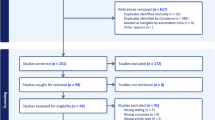

The systematic search yielded 859 records across eight databases, with an additional 53 records identified through other sources, totaling 912 records. After removing 377 duplicates, 535 unique records underwent title and abstract screening. Of these, 428 were excluded as clearly irrelevant, leaving 107 articles for full-text assessment. Following a detailed eligibility evaluation, 94 articles were excluded for the following reasons: conference abstracts without full text (n = 31), wrong outcomes not specific to delirium (n = 24), no NLP methodology described (n = 18), analysis of structured data only without clinical notes (n = 12), not focused on delirium detection (n = 9). Ultimately, 13 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. The study selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

The 13 included studies were published between 2015 and 2024, with 69% (9/13) published in 2022 or later, reflecting the recent growth in this field. Studies originated from four countries: United States (54%, 7/13), Australia (30%, 4/13), China (8%, 1/13), and Norway (8%, 1/13).

Clinical settings and populations

Studies were conducted predominantly in general ward settings (77%, 10/13), with two studies in ICU settings (15%, 2/13) and one in mixed settings (8%, 1/13). The total sample size across all studies exceeded 450,000 patients, though individual study sizes varied dramatically from 54 patients (Amjad et al.24) to 170,868 patients (Chen et al.25).

Patient populations were diverse: seven studies focused on older adults ( ≥ 65 years), while six included all adult patients ( ≥ 18 years). Specialized populations included post-operative surgical patients (Mikalsen et al.26), hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients (Amonoo et al.27), and COVID-19 patients (Pagali et al.28).

Data sources and clinical notes

All studies analyzed retrospective EHR data, with no prospective implementations identified. Clinical notes analyzed included physician progress notes (100%), nursing documentation (85%), and allied health notes (31%). The volume of clinical notes ranged from 942 notes in the smallest study to over 6.9 million in the largest. Five studies linked multiple institutions’ EHRs through research networks, enhancing generalizability.

Delirium definitions

Studies employed various reference standards for delirium identification:

-

CAM or CAM-ICU criteria (38%, 5/13)

-

DSM criteria (23%, 3/13)

-

ICD codes (31%, 4/13)

-

Clinical documentation or behavioral terms (23%, 3/13)

-

Expert annotation (23%, 3/13)

This heterogeneity in outcome definitions represents a significant challenge for comparing performance across studies. Details of study characteristics are presented in Table 1.

NLP methods and technical specifications

The 13 studies employed diverse NLP approaches, which we categorized into five main methodological families:

Rule-based methods (38%, 5/13)

Rule-based approaches relied on predefined keywords and patterns to identify delirium-related content. Fu et al.29 developed the NLP-CAM algorithm using the MedTaggerIE framework, mapping delirium-related keywords to CAM features with assertion detection for negation handling. Chen et al.30 employed a weighted keyword scoring system with 122 Chinese keywords across 27 delirium symptom categories. These methods demonstrated high specificity (85–100%) but variable sensitivity (64–92%).

Machine learning classifiers (31%, 4/13)

Traditional machine learning approaches included Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests, Logistic Regression, and XGBoost. Amjad et al.24 compared dictionary-based and all-tokens approaches, finding that dictionary-based methods with negation handling achieved the best balance (sensitivity 89.4%, specificity 89.4%). Feature engineering techniques included TF-IDF weighting, n-grams, and bag-of-words representations.

Deep learning approaches (15%, 2/13)

Modern neural network architectures showed superior performance. Ge et al.31 compared RNN-LSTM and transformer models, with the transformer achieving 99.1% sensitivity on internal testing. Chen et al.25 evaluated five transformer variants, finding GatorTron (a clinically-trained model) achieved the best F1-score (87.59%) under lenient evaluation criteria.

Topic modeling (8%, 1/13)

Shao et al.32 applied Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) and ICD-based topic modeling, though performance lagged behind other approaches (F1-score 46.8% for LDA).

Semi-supervised learning (8%, 1/13)

Mikalsen et al.26 developed a novel “learning with anchors” framework combining labeled and unlabeled data, achieving AUROC 0.962-0.964.

Technical specifications varied considerably across studies. Only one study (Amjad et al.24) explicitly addressed negation handling using the NegEx tool, while two others manually excluded negated terms. Preprocessing steps, when reported, included tokenization, stemming, and removal of stop words. Software implementations ranged from Python libraries (Scikit-Learn, Spacy, Huggingface) to specialized clinical NLP platforms (MedTaggerIE, ClinicalRegex). Complete technical details are summarized in Table 2.

Model performance

Performance metrics varied substantially across studies and methodologies. Sensitivity ranged from 28.5% for simple keyword searches (Shao et al.32) to 99.1% for transformer models (Ge et al.31). Specificity, when reported, ranged from 63.5% to 100%. The highest AUROC values were achieved by transformer-based models (0.984, Ge et al.31) and semi-supervised learning approaches (0.962–0.964, Mikalsen et al.26).

Dictionary-based methods generally showed balanced performance. Amjad et al.24 demonstrated that incorporating negation handling improved F1-scores from 87.5% to 88.8%. Among machine learning classifiers, Random Forests consistently outperformed other algorithms when applied to structured features derived from clinical notes (Veeranki et al.33, AUROC 0.880–0.886).

Several studies compared NLP performance to existing methods. Pagali et al.28 found that their NLP-CAM algorithm achieved 80% sensitivity compared to 55% for ICD codes and 43% for nursing flowsheets. However, reporting of performance metrics was inconsistent, with only 46% of studies reporting sensitivity, 23% reporting specificity, and 54% reporting AUROC values. Complete performance metrics are detailed in Table 3.

Risk of bias assessment

PROBAST + AI assessment revealed concerning methodological limitations across studies. For model development, 53.8% (7/13) demonstrated overall low risk of bias, 30.8% (4/13) showed unclear risk, and 15.4% (2/13) exhibited high risk. However, evaluation phase assessment was more problematic: only 30.8% (4/13) showed low risk, while 61.5% (8/13) demonstrated high risk of bias.

The primary source of bias was the analysis domain, particularly the lack of external validation. Only one study (Ge et al.31) conducted true external validation using an independent dataset. Most studies relied on random split-sample or cross-validation within a single institution, limiting generalizability assessment.

Outcome definition represented another concern, with 46.2% showing unclear risk due to inconsistent delirium diagnostic criteria. Studies using ICD codes as the reference standard may have suffered from undercoding bias, while those using clinical documentation might capture non-specific behavioral symptoms.

Strengths included appropriate participant selection (84.6% low risk) and well-defined predictors (92.3% low risk). Applicability concerns were minimal, with 84.6% showing low concern for overall applicability. Complete risk of bias assessments is presented in Table 4.

Reporting quality

TRIPOD + AI assessment revealed systematic deficiencies across all 13 studies, with the highest reporting completeness reaching only 43%. Universal gaps (100% non-compliance) were identified in critical areas including structured abstracts, fairness considerations, outcome assessor blinding, sample size justification, missing data handling, and ethics approval. No study provided code availability, data sharing statements, or implementation guidance. These omissions severely limit reproducibility, independent validation, and clinical translation of NLP-based delirium detection systems. Detailed reporting assessments are shown in Supplementary Information.

Discussion

This systematic review identified 13 studies applying NLP techniques to detect delirium from clinical notes, revealing a rapidly evolving field with substantial methodological diversity and performance variation. Modern deep learning approaches, particularly transformer-based models, demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional rule-based and machine learning methods, achieving sensitivity exceeding 99% in some implementations. However, significant gaps in external validation, standardized outcome definitions, and implementation guidance limit the clinical readiness of these approaches.

The evolution from simple keyword matching to sophisticated transformer architectures mirrors broader trends in clinical NLP, but delirium detection presents unique challenges. The fluctuating nature of delirium, the varied terminology used across disciplines, and need to distinguish from baseline cognitive impairment require more nuanced approaches than binary classification tasks.

While transformer models demonstrated impressive performance metrics in controlled research settings (AUROC 0.984), these results should be interpreted cautiously given the limited external validation and potential for overfitting in small datasets. The single study conducting external validation showed performance degradation from internal (99.1%) to external (98.5%) testing, suggesting that real-world generalization gaps may be more substantial than current literature indicates31. Furthermore, the computational requirements and interpretability limitations of transformer models present significant implementation barriers that may favor simpler, more transparent approaches in many clinical settings.

Dictionary-based approaches with negation handling offer a practical alternative, achieving reasonable performance (F1-score ~88%) while providing clinician-interpretable decision logic that facilitates clinical integration and trust-building among end users.

The performance advantage of transformer models (AUROC 0.984) over traditional methods suggests that contextual understanding is crucial for accurate delirium detection. These models can capture subtle linguistic patterns and long-range dependencies that rule-based systems miss. However, their computational requirements and “black box” nature may limit clinical deployment, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

Dictionary-based approaches with negation handling offer a practical middle ground, achieving reasonable performance (F1-score ~88%) with greater interpretability. Recent advances in transformer architectures specifically designed for delirium prediction demonstrate the potential for integrating NLP approaches with broader predictive modeling frameworks. Sheikhalishahi et al.21 developed interpretable deep learning models for time-series electronic health records in delirium prediction for critical care, while Bhattacharyya, et al.22 created delirium prediction tools for ICU screening applications. Giesa et al.23 showed that applying transformer architecture to intraoperative temporal dynamics significantly improves postoperative delirium prediction. These studies illustrate how NLP transformer approaches can be effectively combined with other machine learning methods: NLP can generate labels for training broader predictive models, perform retrospective clinical analysis for quality improvement, and identify vulnerable patients through early symptom detection before formal delirium manifestation. This multi-modal approach leverages the strengths of both unstructured text analysis and structured clinical data.

The improvement from incorporating negation detection highlights the importance of linguistic preprocessing – many delirium symptoms are documented as absent (e.g., “no confusion noted”), and failing to account for negation can substantially degrade performance.

NLP-based delirium detection can substantially improve patient care through multiple mechanisms. First, automated screening enables identification of patients for targeted interventions, particularly during high-risk periods such as overnight shifts when specialized assessment expertise may be limited. Second, NLP approaches facilitate retrospective analysis for quality improvement initiatives, allowing healthcare systems to identify patterns in documentation, assess care gaps, and evaluate intervention effectiveness. Third, early detection capabilities enable identification of vulnerable patients before full delirium syndrome manifestation, potentially allowing for preventive interventions. The scalability of NLP solutions addresses current workforce limitations, enabling comprehensive screening without additional staffing requirements while maintaining consistent detection standards across different clinical environments and time periods.

The heterogeneity in reference standards represents a fundamental challenge. Studies using ICD codes likely suffered from undercoding bias, as administrative codes capture only 20–30% of delirium cases34. Conversely, studies using behavioral disturbance terms may have included non-specific agitation not meeting formal delirium criteria. The most rigorous approaches used CAM criteria or expert annotation, but these were also the most resource-intensive.

The predominance of high risk of bias in model evaluation (61.5%) stems primarily from inadequate validation practices. Internal validation within single institutions fails to assess performance across different documentation styles, EHR systems, and patient populations. The single study conducting external validation (Ge et al.31) showed performance degradation from internal (99.1%) to external (98.5%) test sets – a relatively modest decline that may not reflect real-world generalization gaps.

The complete absence of prospective validation studies is particularly concerning. Retrospective analysis cannot capture the temporal dynamics of clinical documentation or assess integration with clinical workflows. Furthermore, no studies evaluated whether NLP-based detection improves patient outcomes – the ultimate measure of clinical utility.

Reporting quality deficiencies, while concerning, reflects the nascent state of AI reporting standards in medical research. TRIPOD + AI was published in 2024, after most included studies were conducted. However, fundamental omissions like sample size justification, missing data handling, and fairness considerations suggest broader methodological gaps beyond reporting alone.

The translation of NLP-based delirium detection from research to clinical practice faces multiple interconnected barriers that must be systematically addressed. Technical barriers include the lack of standardized delirium terminology across institutions, computational requirements for transformer models, and the absence of EHR integration APIs. Workflow challenges arise from the temporal nature of clinical documentation that complicates real-time detection and the risk of alert fatigue from false positives. Regulatory barriers encompass unclear pathways for AI diagnostic tools, liability concerns, and data governance challenges.

Despite these barriers, significant opportunities exist for improving delirium care through NLP implementation. The current baseline of 20–30% detection rates offers substantial improvement potential that could meaningfully impact patient outcomes. The scalability of NLP solutions enables screening every admitted patient without additional staffing requirements, particularly benefiting smaller hospitals and night shifts with limited specialized expertise. Additional opportunities include enhanced risk stratification, historical note analysis for identifying previous delirium episodes, quality improvement metrics, and medical education applications.

Real-world deployment of NLP-based delirium detection faces substantial generalizability challenges that extend beyond technical performance metrics. Documentation practices vary significantly across institutions, clinical specialties, and individual providers, potentially limiting model transferability even within similar healthcare systems35. Moreover, the temporal dynamics of clinical note creation, with critical information often documented hours after clinical observations, may introduce delays that reduce the clinical utility of automated detection systems26. Healthcare equity considerations represent another critical gap, as current models have not been evaluated for differential performance across demographic groups, potentially exacerbating existing disparities in delirium recognition and management34. Implementation strategies must therefore prioritize comprehensive validation across diverse populations and healthcare settings, with particular attention to ensuring equitable performance and clinical workflow integration.

Healthcare systems considering NLP-based delirium detection should adopt a phased implementation approach prioritizing safety and equity. Initial deployment should focus on retrospective quality improvement applications rather than real-time clinical decision support, allowing for comprehensive performance validation without patient safety risk. Data sharing initiatives should establish standardized, de-identified datasets that enable multi-institutional model validation while protecting patient privacy through differential privacy techniques and federated learning approaches36. Clinical usability requirements must be established through systematic user-centered design processes, ensuring that NLP outputs integrate seamlessly with existing clinical workflows and provide actionable information that enhances rather than disrupts patient care delivery.

The findings of this review illuminate several critical pathways for advancing NLP-based delirium detection toward clinical implementation. Multi-modal integration represents a promising frontier that should explore hybrid architectures combining NLP-extracted features with structured EHR data including laboratory values, vital signs, and medications using advanced fusion techniques. Temporal modeling deserves particular emphasis given delirium’s defining characteristic of fluctuation, requiring architectures explicitly designed for longitudinal clinical narratives that capture documentation patterns over time. Fairness and equity considerations require urgent attention given their complete absence in current literature, necessitating a systematic assessment of model performance across demographic groups and development of debiasing techniques for vulnerable populations.

Future research should systematically evaluate LLM approaches for delirium detection as a separate research question using specialized frameworks like TRIPOD-LLM guidelines37. As LLM applications emerge, systematic reviews should incorporate them with traditional NLP methods, since both use identical performance metrics (sensitivity, specificity, AUROC), enabling direct comparison. Recent studies like Contreras et al.38 suggest LLMs will likely become central to this field, potentially outperforming traditional methods while presenting unique implementation challenges. Key priorities include developing LLM-specific benchmark datasets, establishing cost-effectiveness frameworks for clinical deployment, and creating hybrid approaches that combine LLM capabilities with traditional NLP interpretability. Prospective validation studies with embedded implementation science frameworks are essential for moving beyond retrospective proof-of-concept demonstrations, involving randomized clinical units to measure detection rates, clinical outcomes, and cost-effectiveness. The development of federated learning approaches could address the critical need for multi-institutional validation while respecting patient privacy through differential privacy and secure computation methods. Additional methodological innovations should include synthetic clinical note generation for shareable datasets, privacy-preserving collaborative model development, and mixed-methods evaluation capturing both performance metrics and user experience.

This review’s strengths include comprehensive searching across multiple databases, duplicate independent screening and extraction, use of contemporary bias and reporting assessment tools, and detailed technical characterization of NLP methods. We included studies regardless of language or publication status, reducing selection bias.

Limitations include the inability to perform meta-analysis due to methodological heterogeneity, potential publication bias toward positive findings, and exclusion of studies analyzing structured data only. The rapid pace of NLP advancement means newer techniques may have emerged since our search date. Additionally, our focus on peer-reviewed publications may have missed innovative industry applications.

No LLM-based delirium detection studies were identified within our search timeframe (through March 2025), limiting our ability to compare emerging LLM approaches with traditional NLP methods. This absence likely reflects the recency of LLM applications to this specific clinical problem rather than a systematic exclusion. As demonstrated by recent work emerging after our search cutoff Contreras et al.38, LLMs represent a rapidly evolving area that future reviews should incorporate as a standard category alongside traditional approaches.

For healthcare systems considering NLP-based delirium detection, we recommend starting with validated approaches showing balanced performance, such as dictionary-based methods with negation handling. Initial implementation should augment rather than replace clinical assessment, with careful monitoring of real-world performance.

Policy implications include the need for regulatory frameworks addressing AI-based diagnostic tools, reimbursement models incentivizing improved delirium detection, and data governance structures enabling multi-institutional validation while protecting patient privacy.

Methods

Study design and registration

We conducted a systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines39. The review protocol was registered prospectively in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42025634871).

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed in consultation with a medical librarian and implemented across eight electronic databases: Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, PubMed, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and The Cochrane Library. Searches were conducted from database inception through March 2025 without language restrictions. The search strategy combined terms related to three key concepts: (1) delirium and related conditions (e.g., “acute confusional state,” “altered mental status”), (2) natural language processing techniques (e.g., “text mining,” “machine learning,” “deep learning”), and (3) clinical documentation (e.g., “clinical notes,” “electronic health records,” “narrative text”). The full search strategy for each database is provided in Supplementary Information, including all database-specific controlled vocabulary terms, field restrictions, and Boolean operators used. We specifically searched for LLM-based approaches using terms including “large language model,” “LLM,” “GPT,” “ChatGPT,” “Claude,” “BERT,” and “transformer language model” but identified no studies meeting inclusion criteria within our search timeframe, suggesting this application area is only now emerging.

Additional records were identified through citation searching of included studies and relevant reviews, grey literature searches including conference proceedings from major medical informatics conferences (AMIA, MedInfo, IEEE-EMBS), and consultation with domain experts.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

Population: hospitalized patients of any age in any clinical setting

The broad population criteria were designed to capture the diverse clinical contexts where delirium occurs, recognizing that detection challenges vary across settings. Clinical notes occur more frequently in intensive care units compared to operating theaters, and assessment frequency differs substantially (e.g., each shift in ICUs versus episodic documentation in surgical settings). Detection difficulty varies significantly between pediatric and elderly populations due to developmental differences in cognitive assessment and baseline cognitive status. Delirium presentations also differ substantially, with hypoactive delirium being more challenging to detect than hyperactive forms, requiring different NLP approaches for optimal identification.

-

1.

Intervention: Application of NLP techniques to analyze clinical notes or narrative text from EHRs

-

2.

Comparator: Any reference standard for delirium diagnosis (e.g., CAM, DSM criteria, ICD codes, clinical assessment)

-

3.

Outcome: Detection or identification of delirium

This outcome encompasses multiple validation approaches: NLP detection of formally diagnosed delirium (using standardized criteria such as CAM or DSM), NLP identification of suspected delirium based on clinical documentation, and NLP screening for delirium symptoms that may indicate undiagnosed cases. This broad definition was necessary to capture the range of clinical applications while acknowledging that reference standards vary considerably across healthcare settings.

Study design: any empirical study reporting original research

Studies were excluded if they: (1) analyzed only structured data without clinical notes, (2) focused on conditions other than delirium without specific delirium detection, (3) were reviews, editorials, or opinion pieces without original data, (4) described theoretical frameworks without implementation, or (5) analyzed non-clinical text sources.

During our systematic search (database inception through March 2025), no studies using large language models (LLMs) for delirium detection met our inclusion criteria. While LLMs represent an important emerging technology that uses identical performance metrics (sensitivity, specificity, F1-score) as traditional NLP methods, the absence of published or preprint LLM studies within our search timeframe reflects the nascent state of this application area rather than a methodological exclusion.

Study selection

All identified records were imported into Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) for deduplication and screening. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts, followed by full-text assessment of potentially eligible articles. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. Reasons for exclusion at the full-text stage were documented.

During the screening phase, disagreements between reviewers were initially resolved through discussion. When consensus could not be reached (occurring in <5% of cases), a third senior reviewer (XQ) provided final adjudication. For data extraction disagreements, discrepancies were catalogued and resolved through iterative discussion with reference to the original study publications. Quality assessment disagreements were resolved using the same consensus approach, with particular attention to ensuring consistent application of PROBAST + AI criteria across all studies.

Data extraction

A standardized data extraction form was developed and pilot-tested on three studies (details in Supplementary Information). Two reviewers independently extracted the following information:

-

Study characteristics: authors, year, country, study design, clinical setting, data sources

-

Population: sample size, patient demographics, inclusion/exclusion criteria

-

NLP methodology: approach (rule-based, machine learning, deep learning), specific algorithms, feature engineering, preprocessing steps, software/tools

-

Delirium definition: reference standard used, diagnostic criteria

-

Performance metrics: sensitivity, specificity, positive/negative predictive values, F1-score, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC)

-

Validation methods: internal/external validation, cross-validation approach

Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers independently assessed risk of bias using the Prediction model Risk of Bias Assessment Tool adapted for AI (PROBAST + AI)40. This tool evaluates four domains: participants, predictors, outcome, and analysis, with additional considerations for AI-specific concerns such as data leakage and algorithmic bias. Each domain was rated as low, high, or unclear risk of bias, with an overall judgment for each study.

High risk of bias for validation was defined according to PROBAST + AI criteria as studies lacking external validation on independent datasets, having inadequate sample sizes without statistical justification, demonstrating evidence of data leakage between training and testing sets, or using inappropriate validation methods such as random splits without temporal considerations. External validation requires testing on completely independent datasets from different institutions or time periods, while internal validation through cross-validation or train-test splits within the same dataset provides limited generalizability evidence.

Reporting quality assessment

Reporting quality was evaluated using the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis adapted for AI (TRIPOD + AI) statement41. This 27-item checklist assesses the completeness of reporting for prediction model studies, with additional items addressing AI-specific considerations such as code availability and algorithmic fairness.

Data synthesis

Due to substantial heterogeneity in NLP approaches, patient populations, and outcome definitions, meta-analysis was not appropriate. Instead, we conducted a narrative synthesis organized by NLP methodology, supplemented by tabular summaries of study characteristics, technical specifications, and performance metrics. Where multiple models were reported within a study, we prioritized the best-performing model for summary statistics.

Data availability

The search strategies, data extraction forms, and quality assessment tools used in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information. Individual study data were extracted from published literature and are presented in the tables within this manuscript. No custom code or scripts were developed for this systematic review. Data extraction and analysis were conducted using standard systematic review methodologies. Software used included Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) for study screening and data management, Microsoft Excel 2021 for data compilation, and R software version 4.3.0 for descriptive statistics and visualization.

References

Inouye, S. K., Westendorp, R. G. J. & Saczynski, J. S. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 383, 911–922 (2014).

Salluh, J. I. F. et al. Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ: Br. Med. J. 350, h2538 (2015).

Collins, N., Blanchard, M. R., Tookman, A. & Sampson, E. L. Detection of delirium in the acute hospital. Age Ageing 39, 131–135 (2010).

Inouye, S. K., Foreman, M. D., Mion, L. C., Katz, K. H. & Cooney, J. L. M. Nurses’ Recognition of Delirium and Its Symptoms: Comparison of Nurse and Researcher Ratings. Arch. Intern. Med. 161, 2467–2473 (2001).

Adamis, D., Naveen, S., Whelan, P. J. P. & Macdonald, A. J. D. Delirium scales: A review of current evidence. Aging Ment. Health 14, 543–555 (2010.

Wei, L. A., Fearing, M. A., Sternberg, E. J. & Inouye, S. K. The Confusion Assessment Method: A Systematic Review of Current Usage. J. Am. Geriatrics Soc. 56, 823–830 (2008).

Casey, P. et al. Hospital discharge data under-reports delirium occurrence: results from a point prevalence survey of delirium in a major Australian health service. Intern. Med. J. 49, 338–344 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Clinical information extraction applications: A literature review. J. Biomed. Inform. 77, 34–49 (2018).

Ida, M., Takeshita, Y. & Kawaguchi, M. Preoperative serum biomarkers in the prediction of postoperative delirium following abdominal surgery. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int 20, 1208–1212 (2020).

Oosterhoff, J. H. F. et al. Prediction of Postoperative Delirium in Geriatric Hip Fracture Patients: A Clinical Prediction Model Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 12, 21514593211062277 (2021).

Nagata, C. et al. Development of postoperative delirium prediction models in patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery using machine learning algorithms. Sci. Rep. 13, 21090 (2023).

Wu, S. et al. Deep learning in clinical natural language processing: a methodical review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 27, 457–470 (2020).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Info. Processing Syst. 30, 5998–6008 (2017).

Lindroth, H. et al. Systematic review of prediction models for delirium in the older adult inpatient. BMJ Open 8, e019223 (2018).

Shankar, R., Bundele, A. & Mukhopadhyay, A. Natural language processing of electronic health records for early detection of cognitive decline: a systematic review. npj Digital Med. 8, 133 (2025).

Lv, S., Li, J., He, H., Zhao, Q. & Jiang, Y. Artificial intelligence applications in delirium prediction, diagnosis, and management: a systematic review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 58, 269 (2025).

Lozano-Vicario, L. et al. Biomarkers of delirium risk in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 15, 1174644 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. A Systematic Review of Delirium Biomarkers and Their Alignment with the NIA-AA Research Framework. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 69, 255–263 (2021).

Malgaroli, M., Hull, T. D., Zech, J. M. & Althoff, T. Natural language processing for mental health interventions: a systematic review and research framework. Transl. Psychiatry 13, 309 (2023).

Jandu, J. S., Mohanaselvan, A. & Fang, X. In StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2025).

Sheikhalishahi, S., Bhattacharyya, A., Celi, L. A. & Osmani, V. An interpretable deep learning model for time-series electronic health records: Case study of delirium prediction in critical care. Artif. Intell. Med 144, 102659 (2023).

Bhattacharyya, A. et al. Delirium prediction in the ICU: designing a screening tool for preventive interventions. JAMIA Open 5, ooac048 (2022).

Giesa, N. et al. Applying a transformer architecture to intraoperative temporal dynamics improves the prediction of postoperative delirium. Commun. Med (Lond.) 4, 251 (2024).

Amjad, S. et al. Advancing delirium classification: A clinical notes-based natural language processing-supported machine learning model. Intell.-Based Med. 9, 100140 (2024).

Chen, A. et al. In IEEE 12th International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI). 305–311 (2024).

Mikalsen, K. Ø et al. Using anchors from free text in electronic health records to diagnose postoperative delirium. Computer Methods Prog. Biomedicine 152, 105–114 (2017).

Amonoo, H. L. et al. Delirium and Healthcare Utilization in Patients Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 29, 334.e331–334.e337 (2023).

Pagali, S. R., Kumar, R., Fu, S., Sohn, S. & Yousufuddin, M. Natural language processing CAM algorithm improves delirium detection compared with conventional methods. Am. J. Med. Qual. 38, 17–22 (2023).

Fu, S. et al. Ascertainment of Delirium Status Using Natural Language Processing From Electronic Health Records. J. Gerontology: Ser. A 77, 524–530 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. A novel semiautomatic Chinese keywords instrument screening delirium based on electronic medical records. BMC Geriatrics 22, 779 (2022).

Ge, W. et al. Identifying Patients With Delirium Based on Unstructured Clinical Notes: Observational Study. JMIR Form. Res 6, e33834 (2022).

Shao, Y., Weir, C., Zeng-Treitler, Q. & Estrada, N. In International Conference on Healthcare Informatics. 335–340 (2015).

Veeranki, S. P. K. et al. Is Regular Re-Training of a Predictive Delirium Model Necessary After Deployment in Routine Care?. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 260, 186–191 (2019).

Johnson, J. K., Lapin, B., Green, K. & Stilphen, M. Frequency of Physical Therapist Intervention Is Associated With Mobility Status and Disposition at Hospital Discharge for Patients With COVID-19. Phys. Ther. 101, pzaa181 (2021).

Young, M. et al. Natural language processing to assess the epidemiology of delirium-suggestive behavioural disturbances in critically ill patients. Crit. Care Resuscitation 23, 144–153 (2021).

Li, T., Talwalkar, A. & Smith, V. Federated Learning: Challenges, Methods, and Future Directions. (2019).

Gallifant, J. et al. The TRIPOD-LLM reporting guideline for studies using large language models. Nat. Med. 31, 60–69 (2025).

Contreras, M. et al. DeLLiriuM: A large language model for delirium prediction in the ICU using structured EHR. Res. Sq. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-7216692/v1 (2025).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71 (2021).

Moons, K. G. M. et al. PROBAST+AI: an updated quality, risk of bias, and applicability assessment tool for prediction models using regression or artificial intelligence methods. BMJ 388, e082505 (2025).

Collins, G. S. et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 385, e078378 (2024).

St. Sauver, J. et al. Identification of delirium from real-world electronic health record clinical notes. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 7, e187 (2023).

Young, M. et al. Natural language processing diagnosed behavioral disturbance vs confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit: prevalence, patient characteristics, overlap, and association with treatment and outcome. Intensive Care Med. 48, 559–569 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the medical librarian who assisted in developing the comprehensive search strategy across multiple databases. We thank the healthcare professionals and researchers whose work contributed to this systematic review. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.S. conceived and designed the study, performed the systematic review, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. J.K. performed the systematic review data extraction, quality assessment and edited the manuscript. Y.H.T. performed data extraction, quality assessment, validation, and edited the manuscript. Q.X. provided supervision, verified the extracted data, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shankar, R., Kannan, J., Tan, Y.H. et al. Natural language processing techniques to detect delirium in hospitalized patients from clinical notes: a systematic review. npj Digit. Med. 8, 701 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02051-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02051-w