Abstract

Colorectal cancer recurrence remains a major challenge after curative resection, and accurate tools for early risk assessment are essential to stratify patients and guide personalized therapeutic planning. We developed MPMRecNet, a dual-stream deep learning model for predicting recurrence using multiphoton microscopy imaging of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections from 1071 patients across two hospitals. MPMRecNet employs MaxViT-based encoders, cross-modal attention fusion, and classification under focal loss with mixed-precision optimization. It achieved strong external validation performance (ROC-AUC = 0.849, PR-AUC = 0.664), outperforming traditional clinical predictors. Multivariable analysis confirmed MPMRecNet as the most powerful independent predictor of recurrence (OR = 5.66, p < 0.001), and a combined nomogram incorporating clinical variables further improved stratification (ROC-AUC = 0.872). MPMRecNet offers a non-destructive tool for recurrence prediction from routine pathology slides, supporting precise risk assessment and postoperative surveillance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks as the third most common malignancy and second leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide1. Despite curative (R0) resection, tumor recurrence remains a major determinant of poor long-term survival, occurring in 6%–39% of stage I–III patients despite advances in surgical and adjuvant therapies2,3,4. Currently, risk stratification and treatment decisions largely rely on conventional clinicopathological features such as tumor stage, lymph node involvement, vascular invasion, and serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels5,6. However, substantial outcome heterogeneity persists among clinically similar patients7, revealing critical limitations in individualized recurrence prediction.

The rapid development of computational pathology has enabled deep learning models to extract prognostic features directly from whole-slide histopathology images. In colorectal cancer, multiple studies have applied convolutional or transformer-based architectures to hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stained slides for survival or recurrence prediction8,9,10. Beyond HE, deep learning studies in other cancers indicate that incorporating IHC signals can enhance performance on prognosis and recurrence predictions11,12,13. While promising, these methods depend on chemical staining, which introduces variability across laboratories and protocols and leads to domain shift14. IHC further suffers from assay-to-assay discordance and platform-specific differences, complicating analytic validation and cross-site deployment15. Stains and antigens also degrade with storage time, which reduces signal fidelity and undermines model generalizability and reproducibility16. HE and IHC primarily measure morphology and protein expression; they function as proxies rather than direct measurements of tumor microenvironment biophysics, so features such as collagen architecture and crosslinking are not well captured.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) drives recurrence through dynamic stromal interactions. The “seed and soil” hypothesis posits that metastasis requires permissive extracellular matrices alongside malignant cells17. Collagen architecture, particularly its deposition and crosslinking within tumor cores, facilitates invasion and independently predicts aggressive behavior18,19,20. Multiphoton microscopy (MPM) enables nondestructive, label-free interrogation of these critical features through two complementary modalities: two-photon excited fluorescence (TPEF), revealing cellular morphology via endogenous fluorophores, and second harmonic generation (SHG), specifically mapping collagen microstructure21. It achieves imaging contrast and spatial resolution comparable to conventional histopathology22. Accordingly, it complements conventional computational pathology by supplying label-free microstructural that augments morphology-based models. To date, studies have focused on quantitatively characterizing collagen microarchitecture in SHG images, and these features are associated with survival outcomes across multiple cancer types23,24,25. Our prior work also found that SHG-derived collagen features are associated with lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer26. However, most existing studies rely on manual annotation or automated pipelines to extract collagen features from SHG images, rather than learning directly from raw MPM images27,28. Moreover, the TPEF channel typically remains underutilized. By training end-to-end on dual-modality MPM, deep learning can fuse SHG captured collagen architecture with TPEF captured cellular cues, model multi-scale cell stroma interactions without hand-engineered features, and optimize directly for clinical endpoints. In the context of CRC recurrence prediction, studies on end-to-end dual-modality MPM remain limited.

To address this gap, we propose MPMRecNet, an end-to-end framework for colorectal cancer that combines dual-modality multiphoton microscopy, including TPEF and SHG, with deep learning for recurrence prediction. MPMRecNet employs modality-specific MaxViT encoders with cross-modal attention fusion to capture local-global, multi-scale features and explicitly integrate complementary metabolic and collagen structural information. Our aim is to determine whether the proposed model can accurately predict postoperative recurrence of colorectal cancer. We validate the model on independent external dataset; perform modality ablation experiments; and integrate the model output with clinical variables into a nomogram, evaluating calibration and decision curve analysis (DCA) to demonstrate potential clinical benefit (Fig. 1). The remainder of this paper presents the results, followed by a Discussion that examines the findings and limitations and summarizes the key contributions, and concludes with the Methods section.

Tumor FFPE sections are imaged with multiphoton microscopy to obtain paired TPEF/SHG images, which are preprocessed and used to train and then apply MPMRecNet for patient-level recurrence prediction; performance is evaluated, and the prediction is integrated with clinical variables to build a nomogram for clinical use.

Results

Dataset composition and model architecture

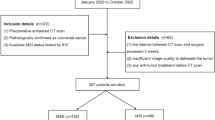

We enrolled 1071 patients with stage I–III CRC after applying exclusion criteria: 834 in the internal training cohort (The Affiliated Hospital of Xiangnan University) and 237 in the external validation cohort (The Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University) (Fig. 2a). The baseline clinicopathological characteristics exhibited no significant differences between the two cohorts (Table 1), enabling robust external evaluation of recurrence predictors.

a Patients diagnosed with stage I–III colorectal cancer were enrolled from the Affiliated Hospital of Xiangnan University and the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University between 2012 and 2019. Following eligibility assessment, 834 patients were assigned to the training cohort and 237 to the validation cohort. b Schematic overview of MPMRecNet.

MPMRecNet adopts a dual-modality design that integrates TPEF and SHG imaging for predicting recurrence in CRC. The model architecture incorporates modality-specific MaxViT encoders (A = TPEF and B = SHG), attention-based pooling, cross-modal attention fusion, and a classification head (Fig. 2b; detailed architecture in Fig. S1).

Training strategy and cross-validation performance

We trained MPMRecNet using a three-phase progressive unfreezing schedule to stabilize fine-tuning (Fig. 3a). Robustness was assessed via stratified 10-fold cross-validation on the internal cohort. Across folds, the model achieved ROC-AUC values ranging from 0.662 to 0.904 (Fig. 3b) and a mean accuracy of 75.1% (Fig. 3c). Despite class imbalance, performance remained balanced with macro-F1 = 0.710 and weighted-F1 = 0.766 on average (Fig. S2a). Precision-recall analysis further confirmed minority-class detectability, with internal PR-AUC values of 0.402–0.771 (Fig. S2b). Fold-wise confusion matrices indicate comparable behavior on recurrence vs. non-recurrence (Fig. S2c).

a Schematic of the 10-fold strategy. For each fold, one subset was designated as the internal validation set and the remaining nine subsets formed the training set, whereas the independent validation cohort was kept locked for final external testing. Model training proceeded through three sequential fine-tuning phases with selective freezing of blocks A and B. b ROC curves for the internal 10-fold cross-validation folds. c Bar plot of classification accuracy in internal validation: overall accuracy, accuracy for non-recurrence cases, and accuracy for recurrence cases across folds. d ROC curves for external validation cohort across all 10 folds. e Classification accuracy in external validation, including overall, non-recurrence, and recurrence-specific accuracy per fold. f Macro and weighted evaluation metrics (precision, recall, F1-score) computed on the external validation set across folds. g PR curves for external validation. PR-AUC is reported for each fold, evaluating the model’s ability to handle imbalanced outcomes.

As a non-informative consistency check, we also evaluated each fold’s checkpoint on the held-out external cohort. Consistent fold-wise performance was observed, with ROC-AUCs ranging from 0.802 to 0.845 (Fig. 3d) and 75.2% overall accuracy (Fig. 3e). Class-specific precision and recall remained stable, resulting in a macro F1-score of 0.706 and weighted F1-score of 0.765 (Fig. 3f). Confusion matrices indicated reliable recurrence prediction, with high-performing folds (e.g., Fold 2 and Fold 8) correctly classifying 45–46 of 58 recurrent cases (Fig. S2d). Precision-recall analysis showed robust minority-class detection capability with external PR-AUCs between 0.616 and 0.683 (Fig. 3g).

Final model evaluation

After retraining on the full internal cohort, we performed an evaluation on the held-out external validation cohort. Attention heatmaps highlighted distinct modality-specific focus areas: TPEF emphasized tumor-stroma interfaces and glandular peripheries, while SHG concentrated on collagen-rich stromal regions (Fig. 4a), indicating complementary extraction of microstructural features. For comparative benchmarking, we also implemented a widely used SHG collagen feature pipeline-based on CT-FIRE as a baseline and trained three conventional classifiers (Random Forest, SVM, and XGBoost) on the extracted features. The model exhibited strong discriminative power with ROC-AUC of 0.849, higher than baseline models (0.744–0.763, Fig. 4b). As summarized in Table S1, MPMRecNet outperforms all baselines on ROC-AUC, PR-AUC, and F1 score, highlighting the benefit of end-to-end dual-modality MPM learning over predefined SHG collagen-feature pipelines. Classification performance showed balanced results with an overall accuracy of 72.6%, accompanied by macro and weighted F1-scores of 0.696 and 0.745, respectively (Fig. 4c). Despite the limited number of recurrence cases (24.1%) in the external cohort, the model achieved a PR-AUC of 0.664 (Fig. 4d), outperforming baseline models (0.460–0.527) and indicating reasonable sensitivity and precision for minority class detection. Clinical reliability was confirmed through high sensitivity (84.5%) and acceptable specificity (68.7%) for recurrence detection, as shown in the confusion matrix (Fig. 4e). Collectively, the high-performance metrics validate MPMRecNet as a clinically applicable recurrence prediction tool.

a Attention visualization on TPEF and SHG image. b ROC curve of the final MPMRecNet model on the external validation cohort, compared with baseline models including Random Forest, SVM, and XGBoost. c Performance summary on the external cohort, including overall accuracy and macro/weighted precision, recall, and F1-scores. d PR curve on the external validation cohort, compared with baseline models including Random Forest, SVM, and XGBoost. e Confusion matrix showing prediction results on the external validation cohort.

Modality contribution and ablation studies

To assess modality-specific contributions, we analyzed attention weight distributions between correct and incorrect predictions (Fig. 5a). Correct classifications demonstrated significantly higher reliance on SHG features (72.3% attention weight), while misclassifications exhibited increased TPEF influence (37.6%), indicating that SHG features are more predictive. Ablation experiments (Fig. 5b) confirmed these findings: the SHG-only model achieved moderate performance (ROC-AUC = 0.744; PR-AUC = 0.485), whereas the TPEF-only model performed substantially worse (ROC-AUC = 0.541; PR-AUC = 0.295) (Fig. 5c, d). DeLong tests show that the dual-modality model significantly outperformed SHG-only and TPEF-only; SHG-only also exceeded TPEF-only (Table S2). Visualization techniques further validated modality complementarity: UMAP revealed enhanced class separation with dual-modality features (Fig. 5e), while Sankey diagrams demonstrated improved prediction concordance (Fig. 5f). Collectively, these results confirm that integrating collagen-rich SHG data with cellular TPEF features creates synergistic value for recurrence prediction.

a Attention weight distribution from Modality A (TPEF) and Modality B (SHG) in correctly and incorrectly predicted cases. b Schematic of the ablation setup, where the Modality A branch was removed to evaluate the independent contribution of SHG. c ROC curves comparing the full MPMRecNet model with single-modality variants. d PR curves for the same models. e UMAP-based dimensionality reduction of features from each model. f Sankey diagram comparing prediction outputs from Modality A, Modality B, and MPMRecNet with the ground truth labels.

Clinical integration and utility evaluation

Before integrating with clinical variables, we confirmed that model performance remained largely consistent across clinicopathological subgroups on the held-out external cohort, including ROC-AUC (Fig. S3), PR-AUC (Fig. S4), and recurrence-class recall (Fig. S5). Notably, the largest performance difference occurred in pN stage subgroups, which may reflect the strong association between lymph node metastasis and recurrence risk. We then performed univariable and multivariable logistic regression to quantify the incremental value of the MPMRecNet. Univariable analysis identified MPMRecNet score as the strongest recurrence predictor (OR = 5.691, 95% CI: 3.52–9.09; p < 0.001), surpassing all clinical variables (Fig. 6a). This dominance persisted in multivariable analysis, where MPMRecNet score remained the primary independent predictor (OR = 5.660, 95% CI: 3.50–9.12; p < 0.001; Fig. 6b). And we built a multivariable nomogram that combines the MPMRecNet score with key clinicopathological covariates (Fig. 6c). The nomogram was developed exclusively on the internal cohort. On this development set, logistic recalibration indicated excellent calibration (α = 3.85 × 10−14, slope = 1.00; Fig. 6d) and the model showed strong discrimination (C-index = 0.881, 95% CI 0.831–0.937). On the held-out external cohort, the nomogram achieved ROC-AUC of 0.872 (Fig. 6e), significantly exceeding individual clinical predictors and MPMRecNet alone as assessed by DeLong tests (Table S3). Decision curve analysis performed only on the external cohort (thresholds 0.01–0.99), with the nomogram and standalone MPMRecNet both showing substantially higher net benefit than traditional approaches across all risk thresholds (Fig. 6f).

a Univariable logistic regression analysis of clinical features and the MPMRecNet prediction score. b Multivariable logistic regression identifying independent predictors of recurrence. c Nomogram model constructed using independent predictors to estimate individualized recurrence risk. d Calibration curve of the nomogram model, showing agreement between predicted and observed recurrence rates. e ROC curve comparison of the nomogram, MPMRecNet, and individual clinical variables in the external validation cohort. f Decision curve analysis comparing the net clinical benefit of the nomogram, MPMRecNet, and individual predictors across varying threshold probabilities.

Discussion

In this study, we introduce MPMRecNet, a novel deep learning framework that leverages dual-modality multiphoton microscopy (TPEF and SHG) for recurrence risk stratification in stage I–III colorectal cancer. Traditionally, recurrence prediction has relied on clinicopathological indicators. But these markers provide only limited prognostic power6,29. More recent computational pathology approaches have advanced prediction using digital analysis of HE and IHC images10,12,13,30,31, yet they remain constrained to conventional staining modalities. In parallel, multiphoton microscopy (MPM) has emerged as a powerful, label-free imaging technique, though prior applications have primarily depended on manual or handcrafted feature extraction27,28,32. We applied an end-to-end deep learning model directly to dual-modality MPM imaging (TPEF and SHG), which outperformed both traditional clinicopathological indicators and feature-based MPM approaches. Since prior deep learning-based recurrence prediction studies were primarily developed on HE/IHC images, we conducted a literature-based comparison. Although heterogeneity in imaging modalities, study designs, and patient cohorts limits strict comparability, MPMRecNet demonstrated competitive or superior performance, with the greatest advantage observed in the independent external validation cohort (Table S4).

In MPMRecNet, the image encoder is a critical component. We adopted MaxViT because its hybrid design couples convolutional inductive bias with concurrent local window attention and sparse global grid attention, enabling joint modeling of high-frequency details and long-range spatial relations33. In contrast, non-hierarchical ViT/DeiT depend on global attention at a fixed resolution, which scales poorly for high-resolution inputs34,35. Hierarchical models such as Swin Transformer emphasize local window attention and pass global context mainly through depth, while Pyramid Vision Transformer introduces a hierarchical pyramid with spatial-reduction attention to control complexity, but does not pair explicit local window attention with an explicit global mechanism in the same block36,37. MaxViT’s concurrent local-global attention therefore preserves fine intra-patch details (e.g., collagen fiber orientation in SHG) and distant tissue context required by MPM images.

MPMRecNet leverages modality-specific MaxViT encoders and cross-modal attention fusion to extract complementary microstructural and cellular features from unstained tissue. The SHG modality focused predominantly on dense, uniformly aligned collagen fibers, aligning with established links between such structures and tumor invasiveness38,39,40. In contrast, the TPEF modality highlighted tumor margins and glandular regions associated with epithelial remodeling during cancer progression41,42. These distinct, biologically relevant attention patterns confirm the capacity of a model to capture complementary aspects of the tumor microenvironment.

Despite inherent class imbalance in recurrence data, MPMRecNet demonstrated robust performance across cohorts (external ROC-AUC = 0.849; PR-AUC = 0.664). Critically, recurrence recall consistently exceeded 75%, addressing the clinical imperative to avoid under-detection of high-risk patients43. Ablation studies confirmed the synergistic value of dual-modality fusion: while SHG-only input retained moderate predictive capacity, TPEF alone yielded substantially weaker results. Only the combined model achieved high discriminative performance and clear outcome clustering in latent space, underscoring the biological complementarity among modalities. Additionally, for the focal loss, following the original formulation and common practice, we fixed γ = 2.0 a priori per the original formulation and a sensitivity analysis showed only modest changes on the external cohort, with γ = 2.0 slightly superior (Table S5), implying that gains arise chiefly from dual-modality and cross-modal fusion.

CRC risk assessment has traditionally relied on clinicopathological features (e.g., TNM staging, tumor grade), yet these often fail to capture biological heterogeneity and true prognosis. Growing evidence highlights the TME, including immune infiltration and invasion patterns, as critical for outcome prediction44,45. Our work aligns with this direction, leveraging deep learning to decode high-dimensional prognostic signatures directly from multiphoton microscopy (MPM) images. Unlike traditional methods, this approach quantifies subtle but prognostically decisive features, including collagen architecture from SHG and cellular dynamics from TPEF, at submicron resolution, thereby uncovering latent prognostic information inaccessible to conventional microscopy. Clinically, MPMRecNet demonstrated transformative potential by surpassing established prognostic markers. In multivariable regression adjusting for all clinicopathologic covariates, MPMRecNet emerged as the strongest independent predictor of recurrence, outperforming even advanced-stage indicators. This robust association demonstrates that the model captures novel, biologically grounded prognostic signals beyond standard histopathological assessment.

To facilitate clinical implementation, we developed a prognostic nomogram integrating MPMRecNet outputs with key clinicopathological variables. This integrated tool demonstrated exceptional performance in external validation (ROC-AUC = 0.872; C-index = 0.881) and provided significant net clinical benefit across decision thresholds, outperforming all individual clinical factors while matching standalone MPMRecNet predictions. Critically, MPMRecNet remained the strongest independent predictor after multivariable adjustment, confirming its unique ability to capture prognostically decisive signals. These results establish MPMRecNet not as a research prototype but as a clinically actionable system for guiding postoperative surveillance intervals and adjuvant therapy selection.

Our current interpretability analysis is qualitative: attention heatmaps highlight modality-specific foci (TPEF at epithelial interfaces, SHG in collagen-rich stroma) but were not quantitatively validated against region-level ground truth. We are acquiring pathologist-annotated masks for tumor-stroma interfaces and SHG-defined collagen structures to compute overlap metrics (Dice, IoU) and localization faithfulness tests46, providing objective validation of model focus. In addition, we have not yet assessed whether attention patterns align with established histologic predictors of recurrence (tumor budding, perineural invasion, desmoplastic reaction)47,48,49; future analyses will quantify these features and evaluate their correlation and incremental value relative to model outputs. Although performance was comparable across various clinicopathological stratifications (Fig. S3), our dataset did not capture detailed histological subtypes such as mucinous vs. non-mucinous adenocarcinomas. And we did not stratify cases by stromal-rich vs. epithelial-rich architecture, as quantitative measurements of stromal composition were not available. We acknowledge that both histological subtype and stromal architecture may influence recurrence dynamics and model behavior. In future work, we plan to enlarge the cohorts, test interactions between model performance and subtype-specific features, and derive quantitative stromal metrics (e.g., SHG-based collagen fraction) to further evaluate whether stromal composition modulates the relative contribution of SHG features in recurrence prediction.

Our retrospective design and restriction to two centers within one national healthcare context necessitate prospective, multi-institutional studies. Robustness to inter-scanner and inter-center variability in MPM imaging (e.g., hardware, laser settings, acquisition protocols) remains to be established; we will expand data collection across heterogeneous systems, perform leave-one-scanner-out evaluation, monitor calibration drift, and explore domain-adaptation and intensity-normalization strategies to support clinical translation. Finally, using fixed-size tiles (224 × 224) without explicit inter-tile spatial modeling may underrepresent whole-slide context (e.g., margin continuity and architectural gradients); we plan to incorporate position-aware encodings, hierarchical MIL, slide-level transformer/graph modules, and multi-scale tiling to recover global context in our future work.

In conclusion, we developed MPMRecNet, a deep-learning framework that integrates dual-modality multiphoton microscopy (TPEF and SHG) with modality-specific encoders and cross-modal attention to predict colorectal cancer recurrence. The model achieved strong predictive accuracy and generalizability across internal and independent external cohorts, and its incorporation into a nomogram provided added clinical utility. Nonetheless, interpretability has yet to be quantitatively validated with pathologist-annotated masks, and our current pipeline does not model whole-slide spatial context. In future work, we will leverage annotations to derive quantitative stromal/ECM metrics to enhance interpretability, and we will further improve performance and robustness through multi-center expansion and the addition of position-aware and multi-scale modeling. Overall, MPMRecNet combines label-free multiphoton imaging and deep learning to leverage intrinsic tissue signals for recurrence risk stratification, with potential for further research and clinical translation.

Methods

Patient cohorts and study design

This retrospective study included patients diagnosed with stage I–III colorectal cancer underwent curative (R0) resection between 2012 and 2019 at two independent institutions in China: the Affiliated Hospital of Xiangnan University and the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University. Patients were excluded if they had multiple primary malignancies, received neoadjuvant therapy, or had incomplete clinical or follow-up data.

A total of 1753 patients were initially screened, 1302 from the Affiliated Hospital of Xiangnan University and 451 from the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University. After applying exclusion criteria, 834 patients from the Affiliated Hospital of Xiangnan University were assigned to the training cohort, and 237 patients from the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University were included in the external validation cohort. All patients were followed for up to 5 years postoperatively. Recurrence was defined as any radiologically or pathologically confirmed local or distant relapse occurring within this period. Patients who were lost to follow-up or died without documented evidence of recurrence were considered to have incomplete clinical data and were therefore excluded from the analysis. Based on this definition, 259 patients (24.2%) experienced recurrence.

To assess baseline comparability, the following key clinicopathological features were compared between the training and validation cohorts: age, sex, tumor size, T/N stage, CEA level, vascular or lymphatic invasion (VELIPI), tumor differentiation (TD), bowel obstruction or perforation (BOorBF), and recurrence rate (Table 1). No significant differences were observed, indicating good balance across groups.

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review boards of both the Affiliated Hospital of Xiangnan University (K/KYX2024-026-01) and the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University (JNUKY-2024-0060). Informed consent was waived due to the use of de-identified archival data and the minimal risk to participants. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Multiphoton imaging and dataset construction

MPM was conducted on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections using a commercial system (Prairie Ultima IV, Bruker, USA). Representative tumor regions were selected under the guidance of an experienced pathologist to ensure biological relevance. Two nonlinear optical imaging modalities (SHG and TPEF) were acquired simultaneously. Excitation was provided by a femtosecond Ti:sapphire laser tuned to 810 nm. Emission signals were filtered through narrow bandpass filters (394–416 nm for SHG; 430–759 nm for TPEF) to ensure spectral separation.

Because acquisition magnifications varied across scanning sessions (20×/40×), to remove scale inconsistencies and ensure cross-sample comparability we isotropically downsampled all images to a 20× reference resolution (0.8303 µm per pixel), native 20× images were unchanged. After scale normalization, images were tiled into non-overlapping 512 × 512 patches and each patch was resized to 224 × 224 via bilinear interpolation to match the ImageNet-pretrained MaxViT input. The distribution of patch numbers per case in both the training and validation cohorts is shown in Fig. S6.

Paired TPEF and SHG images from each patient were processed in parallel. Each imaging modality was preprocessed independently, and all patches were normalized prior to model input. The resulting dual-modality patches were saved as PyTorch-compatible tensors for downstream training and inference. Dataset composition, patient-level splits, and preprocessing steps are summarized in Table S6.

MPMRecNet architecture

MPMRecNet is a dual-stream, attention-based neural network designed to predict recurrence risk from MPM images using both SHG and TPEF modalities. As shown in Fig. S1, the architecture comprises three components: (1) modality-specific patch-level encoders based on MaxViT, (2) patch-level attention pooling, (3) cross-modal attention fusion with a classification head. Layer-wise configuration are summarized in Table S7 and complexity and runtime statistics are provided in Table S8.

To obtain a patient-level representation from variable numbers of patches, we adopt attention-based multiple-instance pooling within each modality. Specifically, each patch embedding is scored by a lightweight two-layer MLP, followed by softmax normalization across all patches from the same patient and modality. The normalized scores are then used to compute a weighted sum of patch embeddings, yielding a single modality-level feature vector. This permutation-invariant pooling naturally handles patients with different numbers of patches. The resulting TPEF and SHG embeddings are subsequently fused through a cross-modal attention block, and the fused representation is passed to a fully connected classification head to predict the recurrence probability.

For each patient, a set of paired SHG and TPEF patches (N × 224 × 224) is extracted and fed into two independent MaxViT encoders. We denote modality A = TPEF and modality B = SHG for consistency with the codebase. Each encoder transforms a variable-length sequence of image patches into a corresponding set of latent feature vectors:

where \({X}^{(A)}\) and \({X}^{(B)}\) denote feature sequences from TPEF and SHG modalities, respectively.

To aggregate the patch-level embeddings into a patient-level feature vector, we implemented a learnable attention mechanism50. For a modality-specific embedding matrix \(X\in {R}^{N\times D}\), attention weights are computed via:

Where \(W\in {R}^{D\times D}\),\(\,v\in {R}^{D}\) and \(f\in {R}^{D}\) is the attended feature vector representing the entire image for one modality. This mechanism enables the model to focus on the most informative regions across varying patch counts.

To effectively integrate complementary information from the two imaging modalities, we designed a unidirectional cross-modal attention module51. Given modality-specific embeddings \({\rm{a}},{\rm{b}}\in \,{R}^{N\times D},\) we treat the TPEF-derived features \(a\) as the query source and attend over both TPEF and SHG representations:

Here, \({W}_{q},{W}_{k},{W}_{v}\in {R}^{D\times D}\) are learnable projection matrices. The fused output \(\mathrm{fused}\) combines both intra and inter modal context, guided by the TPEF modality.

The fused representation \({f}^{\mathrm{fused}}\in {R}^{D}\) is passed through a multilayer perceptron (MLP) classifier to obtain the final logits:

Predictions are computed via softmax:

MPMRecNet training strategy

To ensure stable convergence and effective utilization of pretrained representations, we adopted a three-phase fine-tuning strategy inspired by Fastai52. Each phase progressively increased the trainable capacity of the model, allowing for modality-specific adaptation followed by joint optimization: (1) The encoder for modality B is set to be trainable, while encoder A is frozen; (2) The training roles are switched: encoder B is frozen, and encoder A is unfrozen and optimized; (3) All model parameters are unfrozen for joint end-to-end training. This progressive unfreezing schedule was designed to reduce gradient instability and prevent premature overwriting of pretrained knowledge.

The model was trained using the Adam optimizer in Phases 1 and 2, and Adam with cosine annealing learning rate scheduling in Phase 353. The initial learning rate was set to 1e−4 for modality-specific training and reduced to 7e−5 for the final joint fine-tuning stage. A cosine annealing scheduler with 10% warm-up steps was used to improve convergence during end-to-end training.

During training, we employed the focal loss to handle class imbalance. The focal loss is defined as:

where \({p}_{t}\) is the predicted probability of the true class and \({\alpha }_{t}\) is a class-balancing weight. Following the original focal loss formulation and common practice for imbalanced classification, we fixed the focusing parameter at γ = 2.0 a priori54.

We also utilized mixed-precision training via PyTorch’s Automatic Mixed Precision (AMP) and gradient scaling with GradScaler to accelerate training and reduce memory consumption without compromising numerical stability55. Given the variable number of image patches across patients, we implemented patch-wise feature extraction using sub-batches (patch batch size = 480) to manage GPU memory usage efficiently. This strategy allowed the model to handle per-patient patch heterogeneity while maintaining stable and consistent training behavior.

Model evaluation

To comprehensively evaluate MPMRecNet, we employed both internal cross-validation and external validation on independent data. Model performance was assessed using standard classification metrics, along with modality ablation and interpretability analyses to elucidate the contributions of individual components.

Internal validation employed stratified 10-fold cross-validation exclusively on the internal cohort56. The dataset was stratified to maintain class balance in each fold. For each fold, models were trained on 90% and evaluated on 10% of the internal data. Metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, macro and weighted F1 score, ROC-AUC, and PR-AUC were calculated for each fold57. The external cohort was held out in its entirety throughout training and cross-validation and was not used for training, internal validation, model selection, or hyperparameter tuning. Fold-wise predictions on the external cohort, when reported, are provided as descriptive sanity checks and did not influence any training or selection decisions.

After cross-validation, a single final model was retrained on the full internal cohort and evaluated once on the external cohort using the same metrics, including ROC-AUC and PR-AUC, as well as class-specific recall and overall confusion matrix analysis. The confusion matrix was used to visualize the distribution of true positives, false positives, and misclassified cases, providing insight into the model’s behavior across recurrence and non-recurrence classes.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our architecture, we conducted comparative benchmarking against a widely used SHG collagen feature pipeline based on CT-FIRE28,58. For each patient, SHG image features were extracted using the default CT-FIRE parameters, including fiber density (count per mm²), mean fiber length and standard deviation, mean orientation angle and standard deviation, circular variance of orientation, mean fiber width, and mean SHG intensity. These patient-level features were then used to train three conventional classifiers (Random Forest, SVM, and XGBoost) on the training folds, while the independent external cohort was reserved strictly for final testing. Evaluation followed the same external protocol as MPMRecNet, with results reported in terms of ROC-AUC, PR-AUC, F1-score, and class-specific accuracies.

To investigate the modality-specific contributions, we conducted ablation experiments59. Each variant was evaluated on the external validation set. The full model was trained once using the procedure described above. During ablation testing, either the SHG or TPEF branch was disabled by zeroing its global embedding before cross-modal fusion. This design ensures consistent optimization and avoids variability introduced by retraining.

Statistical analysis and clinical integration

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors associated with recurrence. The MPMRecNet predicted recurrence probability was included alongside standard clinical features such as age, sex, CEA level, tumor size, tumor location, T/N staging, VELIPI, TD, and presence of BOorBF. Variables with a p < 0.05 in univariable analysis were retained for inclusion in the multivariable model. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported for all predictors.

A nomogram was constructed based on the multivariable logistic regression model to enable individualized risk estimation of recurrence on the training cohort60. The nomogram integrated the MPMRecNet score and the selected independent clinical variables. Calibration of the nomogram was assessed using calibration curves, comparing predicted probabilities with observed outcomes61. Mean absolute error and visual alignment with the 45-degree reference line were used to evaluate model reliability. To quantify overall discriminative performance, we computed the concordance index (C-index), which measures the probability that the model correctly ranks a randomly selected pair of patients (one recurrent, one non-recurrent). Higher C-index values indicate better discriminative ability.

Finally, decision curve analysis (DCA) was performed to evaluate the net clinical benefit of using MPMRecNet and the nomogram across a range of decision thresholds62. The DCA curve illustrates the trade-off between true positive benefit and false positive harm, helping to assess the model’s utility in guiding postoperative clinical decisions such as adjuvant therapy or surveillance intensification.

Implementation details

All model development and training were conducted using Python 3.12 on Ubuntu 22.04, with PyTorch version 2.5.1 and CUDA 12.4 for GPU acceleration. The model architecture was implemented using PyTorch’s native modules, with additional utilities from the torchvision and transformers libraries (transformers version 4.36.2). Training was performed under automatic mixed-precision (AMP) to improve computational efficiency and reduce memory usage. Complexity and runtime statistics are reported in Table S8. All experiments were conducted on a single NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090D GPU (24 GB VRAM).

No data augmentation (e.g., rotation, flipping, color jittering) was applied during preprocessing. Given the nature of multiphoton microscopy and the need to preserve spatial and structural integrity across SHG and TPEF channels, raw image morphology was retained throughout training.

Logistic regression modeling, nomogram construction, calibration curve analysis, and decision curve analysis were conducted using R version 4.4.1. Pairwise AUC comparisons between ROC curves were performed on the external cohort using DeLong tests63.

Data availability

Original patient data from this study are not publicly available due to privacy constraints, but may be shared in de-identified form upon reasonable request and institutional approval.

Code availability

The source code for MPMRecNet used in this study is publicly available at https://github.com/yyb2020/MPMRecNet.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Snyder, R. A. et al. Association between intensity of posttreatment surveillance testing and detection of recurrence in patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA 319, 2104–2115 (2018).

Primrose, J. N. et al. Effect of 3 to 5 years of scheduled CEA and CT follow-up to detect recurrence of colorectal cancer: the FACS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 311, 263–270 (2014).

Nors, J., Iversen, L. H., Erichsen, R., Gotschalck, K. A. & Andersen, C. L. Incidence of recurrence and time to recurrence in stage I to III colorectal cancer: a Nationwide Danish Cohort Study. JAMA Oncol. 10, 54–62 (2024).

Weiser, M. R. et al. Clinical calculator based on molecular and clinicopathologic characteristics predicts recurrence following resection of stage I-III colon cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 911–919 (2021).

Dienstmann, R. et al. Prediction of overall survival in stage II and III colon cancer beyond TNM system: a retrospective, pooled biomarker study. Ann. Oncol. 28, 1023–1031 (2017).

Xu, W. et al. Risk factors and risk prediction models for colorectal cancer metastasis and recurrence: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. BMC Med. 18, 172 (2020).

Wulczyn, E. et al. Interpretable survival prediction for colorectal cancer using deep learning. NPJ Digital Med. 4, 71 (2021).

Jiang, X. et al. End-to-end prognostication in colorectal cancer by deep learning: a retrospective, multicentre study. Lancet Digital Health 6, e33–e43 (2024).

Xiao, H. et al. Predicting 5-year recurrence risk in colorectal cancer: development and validation of a histology-based deep learning approach. Br. J. Cancer 130, 951–960 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. IHCSurv: effective immunohistochemistry priors for cancer survival analysis in gigapixel multi-stain whole slide images. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention(MICCAI 2024), 211–221 (Springer, 2024).

Jiang, F. et al. Deep learning-based model for prediction of early recurrence and therapy response on whole slide images in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a retrospective, multicentre study. EClinicalMedicine 81, 103125 (2025).

Su, Z. et al. BCR-Net: a deep learning framework to predict breast cancer recurrence from histopathology images. PLoS ONE 18, e0283562 (2023).

Tellez, D. et al. Quantifying the effects of data augmentation and stain color normalization in convolutional neural networks for computational pathology. Med. Image Anal. 58, 101544 (2019).

Hirsch, F. R. et al. PD-L1 immunohistochemistry assays for lung cancer: results from phase 1 of the blueprint PD-L1 IHC Assay Comparison Project. J. Thorac. Oncol. 12, 208–222 (2017).

He, J. et al. Effect of storage time of paraffin sections on the expression of PD-L1 (SP142) in invasive breast cancer. Diagn. Pathol. 18, 131 (2023).

Gao, L. F. et al. Tumor bud-derived CCL5 recruits fibroblasts and promotes colorectal cancer progression via CCR5-SLC25A24 signaling. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 41, 81 (2022).

Jiang, Y. et al. Targeting extracellular matrix stiffness and mechanotransducers to improve cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 15, 34 (2022).

Yang, Z. et al. Lysyl hydroxylase LH1 promotes confined migration and metastasis of cancer cells by stabilizing Septin2 to enhance actin network. Mol. Cancer 22, 21 (2023).

Wei, S. C. et al. Matrix stiffness drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumour metastasis through a TWIST1-G3BP2 mechanotransduction pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 678–688 (2015).

Wang, S. et al. Towards next-generation diagnostic pathology: AI-empowered label-free multiphoton microscopy. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 254 (2024).

Yoshitake, T. et al. Direct comparison between confocal and multiphoton microscopy for rapid histopathological evaluation of unfixed human breast tissue. J. Biomed. Opt. 21, 126021 (2016).

Xi, G. et al. Large-scale tumor-associated collagen signatures identify high-risk breast cancer patients. Theranostics 11, 3229–3243 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Prognostic significance of collagen signatures in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma obtained from second-harmonic generation imaging. BMC Cancer 24, 652 (2024).

Dong, S. et al. Development and validation of a collagen signature to predict the prognosis of patients with stage II/III colorectal cancer. iScience 26, 106746 (2023).

Jiang, W. et al. Association of the pathomics-collagen signature with lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer: a retrospective multicenter study. J. Transl. Med. 22, 103 (2024).

Guimarães, P., Morgado, M. & Batista, A. On the quantitative analysis of lamellar collagen arrangement with second-harmonic generation imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express 15, 2666–2680 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Fibrillar collagen quantification with curvelet transform based computational methods. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 198 (2020).

Tran, D. et al. A comprehensive review of cancer survival prediction using multi-omics integration and clinical variables. Brief. Bioinform. 26, https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbaf150 (2025).

Kim, P. J. et al. A new model using deep learning to predict recurrence after surgical resection of lung adenocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 14, 6366 (2024).

Lu, M. Y. et al. AI-based pathology predicts origins for cancers of unknown primary. Nature 594, 106–110 (2021).

Zipfel, W. R. et al. Live tissue intrinsic emission microscopy using multiphoton-excited native fluorescence and second harmonic generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 7075–7080 (2003).

Tu, Z. et al. Maxvit: Multi-axis vision transformer. In European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2022), 459–479 (Springer, 2022).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2021) (OpenReview, 2021).

Touvron, H. et al. Training data-efficient image transformers & distillation through attention. In International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2021), PMLR 139, 10347–10357 (PMLR, 2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proc. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2021), 10012–10022 (IEEE, 2021).

Wang, W. et al. Pyramid vision transformer: a versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In Proc. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2021), 568–578 (IEEE, 2021).

Bredfeldt, J. S. et al. Computational segmentation of collagen fibers from second-harmonic generation images of breast cancer. J. Biomed. Opt. 19, 16007 (2014).

Alkmin, S. et al. Migration dynamics of ovarian epithelial cells on micro-fabricated image-based models of normal and malignant stroma. Acta Biomater. 100, 92–104 (2019).

Gole, L. et al. Quantitative stain-free imaging and digital profiling of collagen structure reveal diverse survival of triple negative breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 22, 42 (2020).

Li, L. H. et al. Multiphoton microscopy for tumor regression grading after neoadjuvant treatment for colorectal carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 21, 4210–4215 (2015).

Wu, X. et al. Label-free monitoring of endometrial cancer progression using multiphoton microscopy. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 52, 3113–3124 (2024).

Benson, A. B. et al. Colon Cancer, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 19, 329–359 (2021).

Dienstmann, R. et al. Relative contribution of clinicopathological variables, genomic markers, transcriptomic subtyping and microenvironment features for outcome prediction in stage II/III colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1622–1629 (2019).

Pai, R. K. et al. Quantitative pathologic analysis of digitized images of colorectal carcinoma improves prediction of recurrence-free survival. Gastroenterology 163, 1531–1546.e1538 (2022).

Maier-Hein, L. et al. Metrics reloaded: recommendations for image analysis validation. Nat. Methods 21, 195–212 (2024).

Al-Sukhni, E. et al. Lymphovascular and perineural invasion are associated with poor prognostic features and outcomes in colorectal cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 37, 42–49 (2017).

Lugli, A., Zlobec, I., Berger, M. D., Kirsch, R. & Nagtegaal, I. D. Tumour budding in solid cancers. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 101–115 (2021).

Ueno, H. et al. Desmoplastic pattern at the tumor front defines poor-prognosis subtypes of colorectal cancer. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 41, 1506–1512 (2017).

Ilse, M., Tomczak, J. & Welling, M. Attention-based deep multiple instance learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2018), PMLR 80, 2127–2136 (PMLR, 2018).

Tsai, Y. H. et al. Multimodal transformer for unaligned multimodal language sequences. Proc. Conf. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. Meet. 2019, 6558–6569 (2019).

Howard, J. & Gugger, S. J. I. Fastai: a layered API for deep learning. Information 11, 108 (2020).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. J. a. p. a. Sgdr: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2017) (OpenReview, 2017).

Lin, T. Y., Goyal, P., Girshick, R., He, K. & Dollar, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 42, 318–327 (2020).

Micikevicius, P. et al. Mixed precision training. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2018) (OpenReview, 2018).

Kohavi, R. A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. In International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI 1995), 1137–1145 (Morgan Kaufmann, 1995).

Saito, T. & Rehmsmeier, M. The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets. PLoS ONE 10, e0118432 (2015).

de Vries, J. J., Laan, D. M., Frey, F., Koenderink, G. H. & de Maat, M. P. M. A systematic review and comparison of automated tools for quantification of fibrous networks. Acta Biomater. 157, 263–274 (2023).

Xu, B. et al. Empirical evaluation of rectified activations in convolutional network. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1505.00853 (2015).

Iasonos, A., Schrag, D., Raj, G. V. & Panageas, K. S. How to build and interpret a nomogram for cancer prognosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 1364–1370 (2008).

Van Calster, B., McLernon, D. J., van Smeden, M., Wynants, L. & Steyerberg, E. W. Calibration: the Achilles heel of predictive analytics. BMC Med. 17, 230 (2019).

Vickers, A. J. & Elkin, E. B. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med. Decis. Making 26, 565–574 (2006).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinforma. 12, 77 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (T2341004); the Research Fund of Guangdong Second Provincial General Hospital (2024BSGZ04); National Natural Science Foundation of China (82503329 and 82472858); the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022B1515120043, 2023A1515140117, 2025A1515010448, 2024A1515012947, and 2025A1515011769); the Fellowship of CPSF (2023TQ0136, 2023M741379, and 2024M751321); the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20231069); the President Foundation of Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University (2023B016); the Open Research Project of the Key Laboratory of Viral Pathogenesis & Infection Prevention and Control of the Ministry of Education (2023VPPC-R08); The National Natural Science Cross disciplinary Major Research Program (92374203); and the Key R&D Program Key Special Projects for International Science and Technology Innovation Cooperation between Governments (2023YFE0118700).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: W.J. and O.J.L.; Methodology: Y.Y., D.Z., C.X., L.W., W.J., and G.C.; Data collection: T.L., G.C., R.Y., Y.Z., L.Z., Z.Z., S.Q., and S.L.; Data processing and analysis: Y.Y., D.Z., C.X., and L.W.; Multiphoton imaging: C.X., L.W., Y.Y., Z.Z., and Y.Z.; Model development and training: D.Z. and Y.Y.; Statistical analysis and interpretation: W.J., O.J.L., G.C., and T.L.; Manuscript writing: Y.Y., D.Z., C.X., L.W., W.J., O.J.L., G.C., and T.L.; Manuscript revision: W.J., O.J.L., G.C., T.L., R.H., W.S., Y.B., Y.Y., D.Z., C.X., and L.W.; Guarantor: W.J., G.C., O.J.L., and T.L.; Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Xiao, C., Zou, D. et al. Deep learning-enabled multiphoton microscopy predicts colorectal cancer recurrence from routine FFPE specimens. npj Digit. Med. 8, 689 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02058-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02058-3