Abstract

Rare diseases (RD) affect 3.5–5.9% of the global population, yet patients often endure a diagnostic odyssey averaging around 5–6 years, navigating multiple specialties and referrals. This study investigates the use of information content (IC) as a screening tool to identify RD candidates using SNOMED CT, the clinical terminology standard for the electronic health record (EHR) in the Singapore health system. A longitudinal dataset of 1,274,199 patients (2018–2022) containing 35,898 unique SNOMED terms was analyzed. Rare disease patients (n = 17,575) were identified through SNOMED–Orphanet mappings. IC effectively distinguished RD patient profiles from the first clinical encounter by applying outcome-driven thresholds. The simplicity of implementing the proposed method enables a screening test that can achieve ~95% sensitivity, while maintaining the potential follow-up burden at a reasonable level (20% precision starting from 3 encounters, with an IC threshold of 8.17). This approach also surfaced 71 underdiagnosed rare diseases in the population (57 of genetic origin). To our knowledge, this is the first study to apply information-theoretic metrics to EHR for RD screening, demonstrating its potential as a screening tool at both hospital and health system levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rare diseases (RD) present unique challenges for patients and healthcare systems. Individuals with these conditions often endure a prolonged and uncertain diagnostic “odyssey”, frequently waiting years for an accurate diagnosis1. Studies have found that the average time to diagnosis for RD can be 4–5 years (and often much longer), with some patients waiting over 7 years to finally identify their rare condition, with an average of 30 clinical consultations2. This delay not only prolongs uncertainty and emotional distress but also postpones the initiation of appropriate care. Even after a diagnosis is secured, treatment options are extremely limited – only around 5% of RD have an approved treatment/therapy3—leaving most patients with no specific cure. Moreover, those living with RD often experience significant healthcare disparities4,5. Patients face unequal access to specialists and therapies across different regions and socioeconomic groups, and even in well-resourced countries, they struggle to navigate complex systems, leading to poorer quality of care and outcomes in marginalized communities6. Collectively, these factors underscore the high individual and societal burden borne by RD patients and their families, and the imperative for systemic health system-level improvements7,8.

However, identifying RD patients within health systems is notoriously difficult. Clinical data for these patients are often fragmented across multiple providers and institutions, as individuals tend to seek care from various specialists—resulting in incomplete and siloed health records9. This fragmentation means critical clues can be scattered in different clinics’ files, hindering recognition of the underlying rare condition. In addition, inconsistent coding and documentation practices pose a major barrier. Many RD lack unique or specific codes in traditional classification systems (e.g., ICD), so they may be misclassified or not captured at all. The limitations of ICD-10 in representing rare conditions are well documented10. While newer frameworks like ICD-11 have introduced thousands of RD entries, patients without a confirmed diagnosis remain effectively “invisible” in electronic health records (EHR)10. There is often no standardized flag or screening protocol to mark a patient as a potential rare disease case until a definitive diagnosis is made. As a result, many undiagnosed rare disease patients slip through the cracks of existing EHR systems, leading to delayed or missed diagnoses and suboptimal care planning. These gaps highlight the need for more comprehensive and intelligent approaches to surface rare disease candidates in EHR data.

SNOMED Clinical Terms (SNOMED-CT) is an extensive, multilingual clinical terminology designed to capture detailed information about patient health in a standardized way. Unlike ICD, which primarily serves statistical and billing purposes through a classification of diseases and related health problems, SNOMED-CT enables clinicians to document granular clinical concepts, such as symptoms, findings, and procedures, directly in the electronic health record (EHR). In practice, SNOMED-CT is embedded within EHR systems to support structured data entry and coding is typically done through templates and pick-lists integrated into clinical workflows. Health information managers and clinical coders may also review or map terms to ensure consistency and facilitate linkage to other coding systems, like ICD, for reporting and reimbursement.

Leveraging advanced clinical terminologies and novel analytics could help pinpoint unusual patterns suggestive of a rare disorder, and SNOMED-CT offers much greater granularity for RD than ICD coding. Research has shown that SNOMED-CT covers a far higher proportion of RD terms (over 40%) compared to ICD-10 (~20%), providing the specificity needed to reliably identify rare disease patients from electronic records11. Moreover, since 2021, SNOMED and Orphanet have released an official set of mappings that enables clinicians and researchers to bridge standardized health data with the Orphanet nomenclature for rare diseases12.

Harnessing such rich terminologies, combined with information-theoretic techniques (such as “entropy”-based measures of clinical data variability or “unusualness”), could, in principle, flag patients whose constellation of signs and symptoms is highly atypical. However, to date, there is a lack of established methods that integrate these approaches. Few, if any, current screening tools exploit SNOMED-CT for this purpose or apply entropy-based algorithms to detect out-of-pattern clinical profiles in patient data. Indeed, a recent review found no standardized framework in place for developing and evaluating RD diagnostic support systems9, underscoring a significant gap in our ability to systematically find undiagnosed RD cases from EHR.

This study aims to address this shortfall by exploring the use of information content (IC) and information entropy to identify RD patients in a large EHR dataset comprising ~1.2 million Singaporeans. IC, defined as the degree of specificity of a clinical term in the context of a given dataset, has been used widely in RD research as part of semantic similarity metrics such as Resnik or Lin 13 for patient matchmaking14,15 or disease and gene prioritization16,17,18,19,20. To date, however, IC was employed almost exclusively using the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) as the base ontology21,22 and resources like OMIM23 or the Monarch Initiative24 as knowledge bases. Our study is the first to investigate the potential application of IC as a routine retrospective screening test at both hospital and health system EHR levels using SNOMED-CT, without the need for a semantic similarity metric. We demonstrate that at the health system level, IC clearly differentiates the profiles of RD patients from the first clinical encounter when compared to non-RD controls. At the individual patient level, the proportion of patients that can be statistically stratified (distinguished from controls based on significantly higher IC in their profile) rises with each additional encounter—from ~20.65% of cases by the 3rd encounter to ~68.25% by the 20th encounter. Outcome-driven IC thresholds can be set to prioritize sensitivity or specificity in screening—e.g., achieving ~95% sensitivity, depending on the clinical need.

Results

Dataset stratification

Table 1 lists the demographics of the patient cohort used in this study. The dataset consisted of a total of 1,274,190 individuals tracked longitudinally over four years, 57% of whom were female and 42.7% male (3 individuals had no recorded sex at birth). The distribution of age at the first encounter was ~1% minors (≤18 years old, comprising 26% children and 5% adolescents) and 69% adults (of which 16% were older adults ≥65 years). A total of 3,021,129 clinical encounters were recorded, with a mean of 2.37 encounters per patient and a median of 2.0. The predominant ethnicity was Chinese (26%), followed by Malay (12%) and Indian (11%).

Using the officially validated SNOMED-to-Orphanet mappings, we stratified the EHR dataset into rare disease (RD) individuals and non-rare disease (Non-RD) individuals. As shown in Fig. 1A, 57,077 individuals out of the initial 1,274,190 had at least one SNOMED term corresponding to an Orphanet code in their record. This initial set accounted for 8.60% of the total number of clinical encounters (see Table 1 for context). Applying further stratification rules (as described in the Methods) yielded an observed cohort of 1,233,291 individuals, of whom 16,178 were identified as RD patients (this RD subset accounted for 3.53% of all clinical encounters, with a mean of 6.60 encounters per RD patient). The remaining Non-RD group was split into those with only a single encounter in the dataset (618,440 patients, comprising 50.81% of Non-RD individuals) and those with at least 2 encounters. This latter subgroup (Non-RD patients with ≥2 visits) accounted for 70.92% of all encounters (with a mean of 3.58 encounters per patient) and served as the primary control group for subsequent analyses.

A PRISMA flow diagram of the EHR dataset used in this study, with a focus on patients. B PRISMA flow diagram of the rare disease cohort with a focus on conditions and their classification into three major exclusive categories: Genetic, Neoplasms and Other. The letters “P” and “D” included in each group of diseases denote P—the number of patients and D—the number of distinct diagnoses associated with these patients.

Our aim was to gain deeper insight into the characteristics of RD patients by considering three major categories of RDs (as per the Orphanet classification): Genetic, Neoplastic and Other (i.e., non-genetic, non-neoplastic rare conditions), under the assumption that the underlying patient profiles would exhibit distinct patterns. We considered this grouping based on clinical relevance and on the anticipated subspecialist who might consult the patient. Our primary interest lies in Mendelian genetic diseases, and this grouping helps us differentiate them from rare neoplasms (managed by oncologists) and non-genetic rare diseases (managed by various subspecialists, such as rheumatologists, pulmonologists, etc.).

Figure 1B provides a detailed breakdown of the initial RD cohort (57,077 patients) across these major disease categories. From an initial set of 1496 Orphanet-defined conditions present in the data, 49.66% were genetic diseases (743 conditions), 13.5% were neoplasms (202 conditions), and the remaining ~36.8% were other RDs of non-genetic and non-neoplastic nature (551 conditions). The observed RD patient cohort (16,178 individuals) covered 948 of these conditions, while maintaining approximately the same proportional breakdown by class: 46.2% genetic, 14.4% neoplasms, and 39.4% other RDs. We performed a final refinement of the cohort by excluding individuals whose rare disease diagnosis was already present in their first recorded encounter in our dataset. This step reduced the RD cohort to 8643 patients (accounting for 2.34% of all encounters, with a mean of 8.2 encounters per patient) covering 913 conditions. This restriction was necessary to support our analyses using IC profiles from at least one encounter prior to the diagnosis, to identify RD candidates without the diagnosis being known from the start.

Prevalence analysis

A first analysis, building on the stratification above (and presented in Fig. 1B), was to compute the prevalence of rare disorders in our dataset and compare it to known reference values. Orphanet provides worldwide point prevalence data for 3199 rare conditions, as well as country-specific prevalence for several countries. Singapore, however, is very poorly represented in these data, with only 5 conditions listed (none of which were present in our observed cohort). Of the 948 rare conditions represented in our observed cohort (16,178 individuals), we were able to find 126 that have prevalence information in Orphanet.

Figure 2 provides a comparative overview of these 126 diseases, contrasting the prevalence class assigned by Orphanet with the prevalence class observed in our dataset. We found that 34.92% of the conditions in this subset matched the Orphanet prevalence class, 11.11% appeared overdiagnosed in our dataset (i.e., more frequent than expected), and the remaining 53.97% appeared underdiagnosed (with 23 conditions being significantly underdiagnosed based on our criteria). Examples of rare conditions that were markedly under-diagnosed in our dataset (relative to Orphanet expectations) include: Hereditary elliptocytosis [ORPHA:288; OMIM:611804]—prevalence class 1–9 per 1,000,000, Cystinuria [ORPHA:214; OMIM:220100]—1–9 per 1,000,000, Fragile X syndrome [ORPHA:908; OMIM:300624]—1–9 per 1,000,000, Retinitis pigmentosa [ORPHA:791; OMIM:268000]—1–9 per 1,000,000, and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1 [ORPHA:65753; OMIM:118220]—1–9 per 1,000,000. The complete list of computed prevalence across all conditions is provided in Supplementary Tables S1–S3 and the complete comparison of the 126 conditions with prevalence listed in Orphanet is provided in Supplementary Table S4.

Rows denote classes of prevalence retrieved from Orphanet, columns denote prevalence values computed from our dataset and aligned to the classes used by Orphanet. Cells under the main diagonal denote underdiagnosed conditions. Cells over the main diagonal represented overdiagnosed conditions in our dataset.

Health system-level stratification

Using patient profiles constructed at the level of each clinical encounter (and computing information content for the individual SNOMED terms in those profiles), we first tested our hypothesis at the health system level (i.e., considering the entire dataset in aggregate). Note: To avoid artificially inflating IC, any SNOMED codes corresponding to the rare disease diagnosis itself were excluded from these profiles (see Methods for details). Figure 3 depicts the median information content per clinical encounter alongside the information entropy per encounter, across the first 20 encounters for Genetic Diseases. The trajectory of the values for both median IC and entropy for genetic diseases are shown in contrast to the control population (Non-RD patients). The same comparisons are presented for Neoplasms and Other diseases in Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2.

Two key findings emerge from these charts. First, there is a clear difference in IC between the rare disease groups and the controls at each time point. Individuals in all three rare disease categories have higher median IC in their clinical profiles across the entire timeline of encounters. (Across all SNOMED terms in the dataset, IC values ranged from 0.005 to 15.17, with a mean of 10.58 and a median of 10.81 [interquartile range: 8.30–13.22].) In our analysis, the difference in median IC between RD patients and controls starts at about 0.7 points at Encounter 1 for the Genetic diseases and Neoplasms groups (and ~0.5 for Other RDs), and grows to over 1.0 for the former two and ~0.8 for the latter by the later encounters—i.e., an increase of roughly 7.5% over the overall mean IC of an average SNOMED term. All these differences were statistically significant. Second, a similar phenomenon is observed for information entropy. In early encounters, rare disease patients have notably higher entropy compared to controls. This can be interpreted as RD patients having a higher diversity in their clinical profiles at the beginning of their healthcare journey, likely due to the variability in symptom presentation, multiple specialist consultations, and several differential diagnoses being explored in the diagnostic process.

Across the three disease classes, the patterns in IC (and in entropy) are more similar between Genetic conditions and Neoplasms, whereas the Other RDs show a somewhat different trajectory. Unsurprisingly, the presentations of patients in the Other RDs group tend to be less specific (more analogous to complex or common diseases), although their profile diversity remains somewhat higher than controls over the first 5 encounters. Finally, the IC trend for the subset of underdiagnosed rare disease cases follows a trajectory closer to that of the Other RDs group (lower overall IC), whereas their entropy trend is more similar to the Genetic and Neoplasm groups (higher initial entropy)—see Supplementary Fig. S3 for details.

We performed two additional orthogonal stratifications of the data—by age and by gender. For an easier interpretation of the results, age-based stratification was implemented by collapsing the age groups into Child (categories Child and Adolescent in Table 1) and Adult (categories Young adult, Adult and Older adult in Table 1). The results are depicted in Supplementary Figs. S4–S6 across the 3 groups of disorders. Unsurprisingly, the trajectory of the median IC for Child profiles was markedly different from that of Adult profiles, in general, and significantly more pronounced in Neoplasms. Entropy, on the other hand, was either very closely related or lower, which can probably be justified by children presenting with a narrower, more specific set of early-onset phenotypes when compared to adults. The gender-based stratification (see Supplementary Figs. S7–S9) led to a surprising finding: both the trajectory of the median IC and of the entropy for Females is lower than that for Males. The only potential explanations we can assign to this phenomenon are that females are often underdiagnosed or diagnosed later, leading to fewer and less diverse coded clinical events. Alternatively, given that the difference is less pronounced than in the age-based analysis, this result could be an artifact of the time span covered by our dataset.

Individual-level stratification

At the level of the individual patient, our objective was to understand how well the distribution of median IC in a patient’s longitudinal profile can distinguish that patient from the control group. For this analysis, we excluded patients whose rare disease diagnosis was recorded in their very first encounter (as noted in Methods). Supplementary Fig. S10 presents the distribution of p-values obtained when comparing each RD patient’s profile to the control group (using a statistical test on the median IC distribution) as a function of how many encounters the patient had. In other words, for each patient we test whether their longitudinal profile’s median IC values differ significantly from those of Non-RD patients (with the same number of encounters), and we examine these p-value distributions for patients with different lengths of clinical history. Each boxplot in Fig. S10 represents the variability in p-values for patients with a given number of encounters at diagnosis, providing insight into the statistical significance of distinguishing these groups over time.

We observe that as the number of encounters increases, the median p-values tend to decrease (indicating stronger statistical separation between RD patients and controls with more data). Particularly, patients with neoplasms exhibit a broader spread of p-values at lower encounter numbers but show a more pronounced decrease in p-values as encounter count grows. The genetic RD and other RD groups also show a downward trend in median p-values, suggesting that accumulating more clinical interactions enhances the discriminatory power of IC-based screening methods. Notably, patients with very few encounters exhibit high variability in p-values; this likely reflects the challenge of early identification based on limited clinical data. Overall, these results highlight the importance of leveraging longitudinal patient data to refine screening strategies for rare diseases.

A deeper dive into the first 5 encounters for Genetic disease patients is presented in Fig. 4 as a representative example (for brevity, we focus on this single case; full results for all encounter counts and for all disease classes are provided in Supplementary Figs. S11–S15, including analysis of the underdiagnosed subset in Supplementary Fig. S16). Figure 4 showcases the ability of the distribution of median IC values to stratify rare disease patients based on the number of encounters at the time of diagnosis. Several observations can be made from this figure. First, the violin plots in the top panel suggest that as the number of encounters increases, the proportion of cases with statistically significant separation (p < 0.05, shown below the red threshold line) also increases—particularly from the group of patients with 4 encounters onward. Second, this improvement occurs without a significant increase in the number of distinct concepts captured in patient profiles over time. In other words, patients begin to exhibit distinct diagnostic patterns (higher IC values) after multiple encounters without simply accumulating more medical terms; they present more specific combinations of concepts, rather than just more concepts. Finally, the density plots in the bottom panel show that the distribution of IC values for significant cases is clearly distinguishable from that of normal control cases—patients flagged as significant have more complex problem lists with higher IC codes. This separation between significant and normal cases becomes more pronounced with increasing numbers of encounters, reinforcing the idea that patients who are diagnosed earlier exhibit distinct information patterns compared to those whose diagnosis comes only after many interactions with the healthcare system.

Fine-grained view over the distribution of the p-values obtained from performing a statistical significance test of the distribution of the median IC of a longitudinal profile against the control group at different numbers of encounters for Genetic disease patients. The top panel displays the distribution of p-values for each stratified group (ranging from 2 to 6 encounters), indicating the statistical significance of differences observed in the dataset. The middle panel provides histograms showing the normalized frequency of medical concepts across different stratification groups, with red bars representing the control population, blue bars the significant cases and green bars the non-significant cases. The bottom panel presents the distribution of IC values for each stratification group, comparing significant, non-significant, and normal cases.

In contrast to the previous analysis, where we noted, in some cases, significant differences, age-based and gender-based stratification at the individual level followed in principle the same patterns as the general grouping, as presented in Supplementary Figs. S17–S20. The signal discovered in gender-based stratification above is to some extent present in this analysis as well, with the distributions of the median IC values associated with Females being slightly less discriminative than in Males. The coverage of segregated profiles based on the statistical significance of their difference against controls increases with every encounter from 11.4% to 32.9% (from encounters 2 to 6) in Females and from 13.5% to 37.4% in Males.

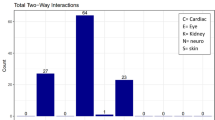

A different perspective on these data can be gained by considering the Orphanet disease categories of the patients. Each Orphanet-defined condition belongs to one or more high-level disease categories (of which Genetic and Neoplasms are included in our analysis). Supplementary Tables S2 and S3 list the percentage of patients achieving significant stratification (p-value < 0.05) by encounter count, broken down by disease category. At a high level, certain categories, such as immunological and bone disorders, show a relatively high stratification rate from the very first couple of encounters, while others, such as hematological, cardiac, dermatological (skin), developmental, or otorhinolaryngological disorders, exhibit a steadier increase, reaching roughly 30%–45% of patients stratified by around the 4th encounter. This suggests that some rare disease categories are inherently easier to flag early using IC-based profiles, whereas others may require more clinical data (more encounters) to differentiate from controls.

Information content as a screening test

The final phase of our analysis examined the diagnostic performance of information content as a potential screening test for rare disease patients. Figure 5 shows ROC curves stratified by the number of clinical encounters (at time of diagnosis) and further broken down by disease class. Across all subgroups, the area under the curve (AUC) improves as the number of encounters increases, suggesting that having more clinical history leads to better discriminatory ability. Specifically, the overall AUC ranges from 0.662 for patients with at least two encounters to 0.717 for those with five or more encounters, indicating progressively better classification performance with additional encounters. Among the disease categories, Neoplasms consistently show the highest AUC—exceeding 0.75 in patients with four or more encounters— whereas Other RDs and genetic conditions exhibit slightly lower performance. The Youden’s J statistic (which optimizes the sensitivity/specificity trade-off) also improves as the number of encounters increases.

While Fig. 5 provides a high-level perspective across all rare conditions, the screening performance of IC is dependent on the complexity and nature of the condition. For example, certain categories such as immunological, bone, and hematological disorders present a different performance profile (as shown in Supplementary Fig. S21), indicating that the effectiveness of IC-based screening can vary by disease category.

Overall, IC-based screening shows strong performance for many rare diseases, achieving higher AUCs and steeper ROC curves, especially when distinctive rare phenotypic “red flags” are present in the patient’s history. However, its effectiveness is notably lower for underdiagnosed rare diseases, which yield weaker AUCs and flatter ROC curves (see Supplementary Fig. S22 for comparison). The key difference lies in how distinct the disease’s phenotypic signature is: underdiagnosed conditions tend to lack high-IC features early in the patient’s journey, so the screening tool has difficulty separating these patients from controls. This suggests that while IC is a valuable metric for rare disease detection, additional strategies are needed to capture the under-diagnosed cases—for instance, combining multiple moderate-information features or incorporating longitudinal patterns (trends over time) to boost sensitivity without driving up false positives.

In essence, the ROC analysis warns that a one-size-fits-all IC threshold will catch many of the obvious rare disease cases but can leave the stealthier (underdiagnosed) ones behind. Tailoring the screening approach (for example, using a lower IC threshold coupled with a confirmatory follow-up test) would be necessary to improve early identification of underdiagnosed rare disease patients and thereby reduce the diagnostic odyssey for those cases. The takeaway is that IC-based screening works well as an initial filter for rare diseases in general, but for the subset of rare diseases that tend to be under-recognized, its performance gap highlights a need for more nuanced or intensive screening methods. This difference in screening efficacy must be accounted for when deploying IC-driven tools: they should be appropriately calibrated or augmented to ensure that underdiagnosed rare conditions are not consistently missed due to their inherently lower-IC profiles in the early stages.

Discussion

Our study set out to provide a data-driven, quantitative overview of the landscape of rare diseases (RD) in Singapore using an EHR dataset covering roughly 20% of the national population. We aimed to demonstrate that information-theoretic methods, in conjunction with SNOMED CT concepts applied to large-scale EHR, can help explain, stratify, and potentially identify RD candidates. Using information content (IC) to quantify the specificity of clinical terms, we analyzed median IC values at the level of patient encounters. While IC has been widely used with HPO-based phenotypes in RD research, this is the first study to apply it directly to clinical coding data in a large-scale EHR.

Using official SNOMED–Orphanet mappings, we estimated the prevalence of 126 rare conditions in the dataset and compared them to Orphanet’s reported figures, with nearly 60% appearing to be underdiagnosed. In practice, this finding could be associated with a variety of potential explanations. Firstly, the use of SNOMED codes could be underutilized, and some could be captured within the text of the clinical notes, which we did not have access to in our analysis. Secondly, our dataset covers only three of the hospitals in the largest health cluster in Singapore, and as such, additional data points on these patients could be present somewhere else. Thirdly, our comparison relies on the reference values provided by Orphanet, which are generalized at a ‘worldwide’ scope and hence do not capture localized geographical differences. We noted above that only five conditions had a Singapore prevalence listed in Orphanet.

We do, however, believe that most of these conditions are truly underdiagnosed, likely due to healthcare system limitations and population-specific factors, which could be genetic, phenotypic or environmental. Many of these conditions are genetic, and both general practitioners and specialists may lack familiarity with their presentation, leading to delays or misdiagnosis. Genetic conditions less expected in Asian populations, or in which the phenotypic presentation differs from non-Asian populations, may also be overlooked25,26,27,28, creating diagnostic gaps compared to better-characterized Western cohorts.

Neurodevelopmental and intellectual disabilities (e.g., Fragile X, Rett syndrome) are notable examples. Fragile X, the most common inherited cause of intellectual disability, is not routinely tested for unless specifically suspected. Rett syndrome can be mistaken for other developmental delays. In Singapore, genetic testing is not universally subsidized, making access difficult without a strong clinical suspicion. Similar patterns occur in rare neuromuscular or neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1, Usher syndrome), which are easily misattributed to more common conditions, such as diabetic neuropathy.

Our analysis showed that IC and entropy can effectively stratify RD patients. As seen in Fig. 3, patients exhibit high entropy early in care, reflecting uncertainty in diagnosis and management. Their IC remains higher than that of patients with complex common diseases, but entropy drops after several visits, suggesting stabilization of their clinical picture. The continued IC elevation suggests the need for ongoing specialized care.

At the individual level, genetic RDs showed stratification patterns similar to neoplasms, while the Other RDs group resembled controls. This temporal perspective helps explain underdiagnosis—many patients don’t exhibit a high-IC signature early on, so they may not be flagged until later. Supplementary Note 1 shows that underdiagnosed patients experience longer gaps between their first and second visits, consistent with broader RD literature1,2,29,30.

Our ROC analysis shows IC-based screening improves with more encounters (higher AUC over time). This supports using a dynamic IC threshold that adjusts based on encounter count—for example, a lower threshold for early encounters and a higher one as more data accumulates. This approach could better balance sensitivity and specificity.

While promising, the study has limitations. The dataset spans only four years and comes from a single healthcare cluster, limiting generalizability. Our findings depend on the quality of SNOMED-Orphanet mappings and Orphanet’s classification of rare diseases. Orphanet defines which conditions count as “rare” (and even includes some borderline uncommon conditions); any gaps or inconsistencies in its catalog could affect our stratification outcomes. The long-tailed distribution of RD in the dataset means many conditions are represented by only a few patients, limiting statistical power for some analyses.

From a methodological perspective, the size of the dataset could suggest that association rule mining or collaborative filtering techniques might uncover meaningful co-occurrence patterns among SNOMED codes to stratify rare disease patients, in contrast to relying solely on information content. However, in practice, applying the apriori algorithm to our dataset produced no significant association rules with support above 0.10—a threshold that is already low. This result is unsurprising given the extreme sparsity of the data: our cohort includes 35,898 unique SNOMED codes, with the distribution of both singletons and bigrams heavily skewed to the left, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S23. Specifically, 10,764 terms appear in a single encounter, 4702 in two encounters, and 2709 in three, with 21,245 terms appearing in at most five encounters overall. A similar phenomenon exists for bigrams: out of 695,040 total bigrams, 489,369 occur only once and 85,644 occur twice. This pronounced long-tail distribution severely constrains the generation of robust co-occurrence rules, illustrating why information content–based approaches remain better suited to capturing clinically relevant signals in such sparse, heterogeneous rare disease datasets.

Supervised machine learning models have been trained on labeled EHR cohorts to recognize rare diseases. Hersh et al.31 trained a classifier on 30 known cases of acute hepatic porphyria (AHP) as part of a corpus consisting of 200,000 cases and their associated EHR data. Their work was subsequently followed by a hybrid method to identify patients with aromatic L‑amino acid decarboxylase deficiency (AADCd) in EHR data32. The method begins by encoding expert clinical knowledge into a computable form—mapping signs, symptoms, lab results, and diagnostic codes relevant to AADCd. Natural language processing techniques are then employed to extract additional features from unstructured clinical notes. Finally, a machine learning model is trained—combining structured and NLP-derived features—to flag potential undiagnosed AADCd cases for further clinical review. Similarly, unsupervised techniques, and in particular clustering algorithms, have been used to group patients with similar phenotypic profiles. For example, collaborative filtering—a technique adopted from recommender systems—has been applied to patient-phenotype matrices to cluster patients with similar rare conditions. The work described in ref. 33 showed that by leveraging phenotypic similarity (including NLP-based features extracted from clinical notes), patients could be grouped such that those in the same cluster often shared a related rare disease.

Overall, we believe that information content-based screening approaches offer several distinct benefits in the context of rare diseases. More specifically, they are relatively easy to implement and can flag patients even when no prior cases are in the dataset, which is crucial for rare diseases where labeled training data are often nonexistent. They are also relatively transparent and interpretable, since the value of IC itself denotes a measure of rarity of each symptom, and hence a score using IC can provide an explanation for the contribution of each symptom to the final outcome.

On the other hand, our approach, and IC-based approaches in general, do have important limitations and differences when compared to data-driven ML techniques. A fundamental drawback is that, unlike ML algorithms (especially unsupervised ones), such methods cannot discover new patterns or atypical clusters. ML models can capture complex feature combinations or temporal patterns (e.g., a certain sequence of events in the EHR) that a simple weighted sum cannot. For instance, a deep model might learn that the co-occurrence of two moderately informative signs is highly predictive of a disease, even if each sign alone is not rare enough to have a big weight. Information content methods would undervalue such combinations. Moreover, supervised ML can sometimes infer a risk from surrogate markers in the data, even if direct evidence is missing, by learning associative patterns.

It is worth noting that our work builds on and complements efforts like OARD (Open Annotations for Rare Diseases)34, which demonstrated the value of leveraging relative frequencies and chi-square statistics to identify significant phenotype–disease associations within EHR data. While OARD focuses on quantifying how specific phenotypes are over- or underrepresented for particular rare diseases, our approach extends this by using information content and entropy to capture the overall complexity and diagnostic informativeness of a patient’s recorded health data. By screening patients based on these aggregate information measures, we aim to flag potentially undiagnosed or misclassified rare disease cases at scale. Together, these approaches highlight the power of statistical and information-theoretic methods to extract hidden diagnostic signals from routine clinical data.

In summary, to implement the IC-based screening across health systems, key requirements include mapping local coding systems to SNOMED CT or equivalent ontologies, access to longitudinal patient data, and integration into clinical workflows. Next steps include validating its utility through prospective deployment as decision support alerts in EHR systems like EPIC and adapting the approach for non-SNOMED environments via standardized crosswalks or concept harmonization.

Methods

Study setting and dataset

SingHealth is Singapore’s largest public healthcare cluster, providing comprehensive and integrated care across a wide range of specialties. Its network includes acute tertiary hospitals, national specialty centers, polyclinics, and community hospitals, collectively handling more than 4 million patient visits each year35. The dataset used for our analysis is a longitudinal extract of de-identified health records from three institutions within SingHealth: Singapore General Hospital, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, and the National Heart Centre. Problem lists coded as SNOMED CT terms were aggregated across all clinical encounters during the period January 2018 to April 2022 (a total of 17 quarters). In the context of an EHR, problem lists included structured components of the encounters—in particular diagnoses, significant symptoms and relevant findings—and are assigned manually by the consulting clinicians. The clinical encounters in our dataset were both inpatient and outpatient. The dataset did not, however, capture the type of encounter or the sub-specialty. The data was de-identified; for each patient, the extracted record included a random unique identifier (hash), sex, ethnicity, age at each clinical encounter, and a timestamped list of clinical encounters with their associated SNOMED CT codes. Given the nature of coding practices and the focus on rare diseases, the data included both patients with confirmed diagnoses and those potentially undiagnosed (i.e., patients who might later be found to have a rare disease).

Coding of rare diseases

Clinical coding of rare diseases presents significant challenges due to the lack of integrated terminology and specific codes. Orphanet was established in 1997 by the French National Institute for Health and Medical Research as a unique resource to gather and improve knowledge on rare diseases. Over time, Orphanet has become the gold standard for rare disease definitions and maintains the Orphanet rare disease nomenclature (ORPHA codes)12. In 2021, SNOMED CT and Orphanet released the first official cross-terminology mapping, enabling researchers and clinicians to directly connect SNOMED codes in health records with corresponding Orphanet rare disease identifiers. In our study, all SNOMED concepts were aligned to the SNOMED CT International Edition (version 2024-12-01), and rare diseases were identified using the official SNOMED CT–Orphanet map (Production Release, July 2024)36. Given the longitudinal yet incomplete nature of our dataset, we introduced a rule to increase confidence in identifying true rare disease patients: a patient was considered a true positive RD case only if a SNOMED code mapped to an ORPHAcode was recorded on at least two separate encounters (different dates).

Information content and entropy

Longitudinal patient profiles are at the core of the method we propose. A depiction of the process employed to create them and their use in the downstream analysis is provided in Fig. 6. The analysis comprises 3 steps:

-

1.

Creation of longitudinal profiles

-

2.

Analysis of IC’s ability to discriminate at the health system level—when considering patients part of a corresponding cohort (RD vs. normal)

-

3.

Analysis of the discriminatory effectiveness of IC at the individual patient level—when considering each patient’s profile individually in the RD vs normal context

Individual information content (IC) is computed for each SNOMED code present in the problem list associated with each clinical encounter. The median IC and the information entropy are then computed using the list of IC values. The temporal profile is assembled using all encounters up to the encounter that contains the rare disease diagnosis, which is explicitly removed from the profile to avoid an artificial increase of the median IC and information entropy. These values are then utilized to compute the Health System-level view across all patients, as well as the statistical significance of the profile at the individual level.

The longitudinal profiles were constructed by grouping SNOMED CT codes by encounter date—i.e., all concepts recorded on a given date comprised that patient’s “profile” for that date. Information content was computed for all SNOMED CT terms captured in the dataset using Eq. 1, and information entropy was computed for each timestamped profile using Eq. 2. (Our implementation utilized the entropy function from the scipy.stats Python package)

Equation 1 defines the information content of a term as the negative logarithm of the probability of that term appearing in a dataset (p(term)), which is subsequently denoted by the frequency of the term in the dataset divided by the total number of visits. Equation 2 defines the entropy of a profile as the negative sum across all terms in the profile of p(term) and the logarithm of p(term); where p(term) is defined as in Eq. 1.

It is important to note that, for the purposes of our analysis, SNOMED codes representing rare disease diagnoses were removed from the profiles to ensure we did not artificially inflate the IC or entropy values (since including the diagnosis code itself would trivially increase information content). We did retain the dates on which those diagnosis codes occurred and treated those as the dates of diagnosis for the corresponding conditions in our analyses.

Health system-level stratification

To achieve a more granular understanding of IC behavior in rare diseases, we imposed a mutually exclusive grouping on the top-level Orphanet classifications. Specifically, we grouped all Genetic rare diseases first, then grouped Neoplasms (that were not genetic), and classified any remaining rare diseases as Other RDs.

Health system-level stratification was performed by considering one encounter at a time and comparing the distribution of the median IC values of the profiles of each patient in the RD cohort to the same distribution of each patient in the control group (i.e., Non-RD patients with 2 or more encounters in Table 1) at that encounter. More concretely, we indexed chronologically all encounters (up to max. 20 encounters), iterated over this indexed list and for every step (or index i), we created 2 groups: (1) all RD patients who had at least i encounters; and (2) all control patients satisfying the same criteria. The distribution of the median IC across all profiles in the first group was then compared to the distribution of the median IC across all profiles in the second group. We did this separately for each RD category (Genetic, Neoplasms, Other RDs). A parallel analysis was done for information entropy at the encounter level. Statistical significance of differences between RD and Non-RD groups was assessed using an independent two-sample t-test.

Individual-level stratification

For the individual-level stratification (depicted in the lower part of Fig. 6), for each patient in the “Diagnosis not in first encounter” RD cohort (see Fig. 1B for cohort definition), we performed a non-parametric significance test to compare that patient’s profile against the control group. More concretely, for each individual patient in both the RD and control groups, we created the distribution of median IC values across each individual encounter. Subsequently, for each RD patient, we computed the Mann–Whitney U test to compare the patient’s distribution of median IC values against the distributions of all patients in the Non-RD control group (with ≥2 encounters). The underlying assumption was that if the coded trajectory of a rare disease patient is different from a non-rare disease patient, then this will be materialized in a significant difference of the distribution of the IC values of the rare disease patient’s profiles against the same distribution of a patient from the control group. The choice of the RD cohort (excluding those diagnosed in encounter 1) was driven by the need to have at least one pre-diagnosis encounter profile to compute a meaningful median IC for comparison.

Data availability

The data used in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and legal restrictions but are available from the senior author on reasonable request.

References

Phillips, C. et al. Time to diagnosis for a rare disease: managing medical uncertainty. A qualitative study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 19, 297 (2024).

Willmen, T. et al. Rare diseases: why is a rapid referral to an expert center so important?. BMC Health Serv. Res. 23, 904 (2023).

Fermaglich, L. J. & Miller, K. L. A comprehensive study of the rare diseases and conditions targeted by orphan drug designations and approvals over the forty years of the Orphan Drug Act. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 18, 163 (2023).

Jonker, A. H., Cavaller-Bellaubi, M., Nishimura, Y. & Pearce, D. A. Access in the rare diseases landscape. Lancet Glob. Health 12, e1587 (2024).

Baynam, G. et al. Global health for rare diseases through primary care. Lancet Glob. Health 12, e1192–e1199 (2024).

Adachi, T. et al. Enhancing equitable access to rare disease diagnosis and treatment around the world: a review of evidence, policies, and challenges. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 4732 (2023).

The Lancet Global Health The landscape for rare diseases in 2024. Lancet Glob. Health 12, e341 (2024).

Thygesen, J. H. et al. CVD-COVID-UK/COVID-IMPACT Consortium. Prevalence and demographics of 331 rare diseases and associated COVID-19-related mortality among 58 million individuals: a nationwide retrospective observational study. Lancet Digit. Health 7, e145–e156 (2025).

Tinker, R. J., Peterson, J. & Bastarache, L. Phenotypic presentation of Mendelian disease across the diagnostic trajectory in electronic health records. Genet. Med. 25, 100921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2023.100921 (2023).

Baxter, M. F., Hansen, M., Gration, D., Groza, T. & Baynam, G. Surfacing undiagnosed disease: consideration, counting and coding. Front Pediatr. 11, 1283880 (2023).

Fung, K. W., Richesson, R. & Bodenreider, O. Coverage of rare disease names in standard terminologies and implications for patients, providers, and research. AMIA Annu Symp. Proc. 2014, 564–572 (2014).

Pavan, S. et al. Clinical practice guidelines for rare diseases: the orphanet database. PLoS ONE 12, e0170365 (2017).

Sánchez, D. & Batet, M. Semantic similarity estimation in the biomedical domain: an ontology-based information-theoretic perspective. J. Biomed. Inf. 44, 749–759 (2011).

Rasi, C. et al. PatientMatcher: a customizable Python-based open-source tool for matching undiagnosed rare disease patients via the Matchmaker Exchange network. Hum. Mutat. 43, 708–716 (2022).

Sobreira, N. L. M. et al. Matchmaker exchange consortium. Matchmaker exchange. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 95, 9.31.1–9.31.15 (2017).

Deisseroth, C. A. et al. ClinPhen extracts and prioritizes patient phenotypes directly from medical records to expedite genetic disease diagnosis. Genet. Med. 21, 1585–1593 (2019).

Robinson, P. N. et al. Interpretable clinical genomics with a likelihood ratio paradigm. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 107, 403–417 (2020).

Zemojtel, T. et al. Effective diagnosis of genetic disease by computational phenotype analysis of the disease-associated genome. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 252ra123 (2014).

Son, J. H. et al. Deep phenotyping on electronic health records facilitates genetic diagnosis by clinical exomes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 103, 58–73 (2018).

Clark, M. M. et al. Meta-analysis of the diagnostic and clinical utility of genome and exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in children with suspected genetic diseases. NPJ Genom. Med. 3, 16 (2018).

Köhler, S. et al. Expansion of the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) knowledge base and resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D1018–D1027 (2019).

Gargano, M. A. et al. The Human Phenotype Ontology in 2024: phenotypes around the world. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D1333–D1346 (2024).

Amberger, J. S., Bocchini, C. A., Scott, A. F. & Hamosh, A. OMIM.org: leveraging knowledge across phenotype-gene relationships. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D1038–D1043 (2019).

Shefchek, K. A. et al. The Monarch Initiative in 2019: an integrative data and analytic platform connecting phenotypes to genotypes across species. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D704–D715 (2020).

Lieviant J. A. et al. Determinants of diagnostic yield in a multi-ethnic Asian inherited retinal disease cohort. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-025-01833-w (2025).

Chan, S. H. et al. Analysis of clinically relevant variants from ancestrally diverse Asian genomes. Nat. Commun. 13, 6694 (2022).

Pua, C. J. et al. Genetic studies of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Singaporeans identify variants in TNNI3 and TNNT2 that are common in Chinese patients. Circ. Genom. Precis Med 13, 424–434 (2020).

Bylstra, Y. et al. SS. Population genomics in South East Asia captures unexpectedly high carrier frequency for treatable inherited disorders. Genet Med 21, 207–212 (2019).

Chiu, A. T. G., Chung, C. C. Y., Wong, W. H. S., Lee, S. L. & Chung, B. H. Y. Healthcare burden of rare diseases in Hong Kong - adopting ORPHAcodes in ICD-10 based healthcare administrative datasets. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 13, 147 (2018).

Walker, C. E. et al. The collective impact of rare diseases in Western Australia: an estimate using a population-based cohort. Genet. Med. 19, 546–552 (2017).

Hersh, W. R., Cohen, A. M., Nguyen, M. M., Bensching, K. L. & Deloughery, T. G. Clinical study applying machine learning to detect a rare disease: results and lessons learned. JAMIA Open 5, ooac053 (2022).

Cohen, A. M., Kaner, J., Miller, R., Kopesky, J. W. & Hersh, W. Automatically pre-screening patients for the rare disease aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency using knowledge engineering, natural language processing, and machine learning on a large EHR population. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 31, 692–704 (2024).

Shen, F. et al. Leveraging collaborative filtering to accelerate rare disease diagnosis. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2017, 1554–1563 (2018).

Liu, C. et al. OARD: Open annotations for rare diseases and their phenotypes based on real-world data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 109, 1591–1604 (2022).

https://polyclinic.singhealth.com.sg/news/regional-health-system/distilling-the-data [Accessed 03.04.2025].

https://confluence.ihtsdotools.org/display/RMT/SNOMED+CT+to+Orphanet+Map+package+Production+Release+Notes+-+July+2024 [Accessed 03.04.2025].

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Mr Mark Heng (SingHealth Office of Insights and Analytics), Ms Wang Xin Yi and Ms Sim Ching Yee (KKH Data Analytics Office) for their support with data extraction. SSJ is supported by National Medical Research Council Clinician Scientist Award (NMRC/CSAINVJun21-0003), (NMRC/CSAINV24jul-0001) and SingHealth Duke-NUS AM Strategic Fund Award PRISM/FY2022/AMS(SL)/75-A137. TG is supported by NMRC/CSAINVJun21-0003 and by the National Medical Research Council (NMRC) Research, Innovation and Enterprise (RIE2025) Centre Grant seed funding [NMRC/CG1/006/2021-KKH]. WKL is supported by National Precision Medicine Program (NPM) PHASE II FUNDING (MOH-000588). Sanofi Aventis provided partial funding for the initial data extraction and carried no role in data analysis, results interpretatio or manuscript writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization of research aims and goals (T.G., P.N.R., W.K.L., T.T., T.Y.W., G.B., S.S.J.). Methodology development (T.G., P.N.R., T.T., G.B., S.S.J.). Validation and rigor (T.G., P.N.R., T.T., T.Y.W., N.K., G.B., S.S.J.). Analysis and interpretation (T.G., P.N.R., T.T., G.B., S.S.J.). Investigation and collection of data (T.G., K.N., J.H., K.K.Y., G.B.K., S.S.J.). Data curation (T.G., W.K.L., G.B.K.). Writing original draft (T.G., N.K., S.S.J.). All authors read and approved the final paper. Funding acquisition (S.S.J., G.B., N.K.).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Groza, T., Robinson, P.N., Lim, W.K. et al. Information content as a health system screening tool for rare diseases. npj Digit. Med. 8, 720 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02096-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02096-x