Abstract

Sjögren’s disease (SjD) is a common systemic autoimmune disease that remains difficult to diagnose early due to non-specific symptoms and lack of definitive biomarkers. This multicentre retrospective cohort study analysed data from 34,958 patients across three hospitals in China to assess the diagnostic potential of routine laboratory tests and to develop a robust, low-cost artificial intelligence model, the Sjögren Multi-criterion Feature Integration Framework (SMFIF). This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06982482). The model was built using 16 optimal features selected through ensemble learning and SHAP analysis, and validated internally (n = 9329) and externally (n = 545). SMFIF achieved high diagnostic performance, with AUCs of 0.929, 0.934, and 0.964 in testing, internal, and external validation sets, respectively, outperforming conventional biomarkers such as anti-SSA/Ro and ANA. Calibration curves and confusion matrices confirmed its reliability. SMFIF is publicly available and provides probabilities of SjD based on laboratory data, offering a practical diagnostic tool for clinical use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sjögren disease (SjD) is one of the most common systemic autoimmune diseases, yet effective targeted therapies remain elusive1,2. The prevalence of SjD ranges from 0.01% to 0.05%, mostly affecting adult females3,4. The clinical course of SjD is characterised by significant heterogeneity, ranging from mild, gradually progressive exocrine dysfunction to severe systemic manifestations. Extra-glandular involvement is frequently observed and often precedes diagnosis in nearly half of all patients5. People with or without extra-glandular involvement have a lower quality of life compared to the general population3,6,7,8. A comprehensive epidemiological meta-analysis has highlighted an increased incidence of malignancies (excluding lymphoma), infections, and cardiovascular diseases among individuals with SjD9,10. However, diagnostic delay is common among patients with SjD11. In a substantial international cohort of SjD patients, 7–8% lacked ocular or oral symptoms at the time of diagnosis, resulting in frequent misdiagnoses12,13. A study of 524 individuals presenting with dry eyes and dry mouth revealed that 75.2% had initially been misdiagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), or systemic sclerosis (SSc). Of these, 46.5% were subsequently correctly identified as having SjD14. These findings emphasise the critical importance of early and accurate recognition of SjD in order to improve patient outcomes.

The clinical diagnosis of SjD relies on expert clinical assessment. While established classification criteria, such as those from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)-European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), are valuable research tools for defining standardized cohorts, they are not used for individual patient diagnosis2,15,16. These classification criteria prominently feature the presence of anti-SSA/Ro autoantibody as a key component. However, only 75% of patients with clinically diagnosed SjD test positive for these antibodies17. Clinicians often utilize several elements incorporated within these research criteria to support the diagnostic evaluation. These include positive findings on minor salivary gland biopsy demonstrating focal lymphocytic sialadenitis, reduced tear and salivary flow rates as assessed by Schirmer’s test, and abnormal findings on salivary gland imaging like delayed contrast elimination on sialography. Other commonly observed laboratory abnormalities in SjD include antinuclear antibodies (ANA), low complement 4 (C4) levels, rheumatoid factor (RF), and elevated immunoglobulin G (IgG)18,19,20,21,22,23. The lack of a single, highly specific and sensitive biomarker, combined with the high cost of certain tests and the invasiveness of some procedures (like biopsy), contributes significantly to the challenges in diagnosis, leading to underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis.

Advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and the growing availability of big data have opened new avenues for disease screening. The present retrospective multicentre study was conducted with the objective of developing a robust, cost-effective and generalisable Sjogren Multi-criterion Feature Integration Framework (SMFIF) that leverages routine laboratory tests to assist in the identification of SjD.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population and cohort composition

Between January 1, 2013, and January 1, 2023, a total of 34,958 individuals were finally included (Fig. 1). The DTH group (training set) included a total of 17,558 participants, of whom 9685 were in the Sjögren’s group and 7873 were in the control group. The DTH cohort (testing set) comprised 7526 participants, with 3429 in the Sjögren’s group and 4097 in the control group. The internal validation set included 9329 participants, of which 4203 were in the Sjögren’s group and 5126 in the control group. The external validation set, the SMH and HFPH cohort, consisted of 545 participants, with 139 in the Sjögren’s group and 406 in the control group. The baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized (Table 1). The baseline data results from the three datasets showed significant differences between the control and the SjD group in many haematological characteristics (Supplementary Table 2). The median age of the testing cohort was 52 years. Of these, 89.9% were female and 8.7% were smokers. In the internal validation cohort, the median age was 53 years, 94.7% were female, and 12.8% were smokers. In the external validation cohort, the median age was similar to the testing cohort at 56 years. 91.4% were female and 9.3% were smokers. The median symptom duration in SjD group was longer across all sets (testing: 3.5 years; internal validation: 4.0 years; external validation: 2.8 years) compared to controls (0.8 years, 0.6 years, 0.6 years). Organ involvement was elevated in SjD groups, with higher rates of liver (6.5–9.0% vs 3.0–5.0%), renal (14.4–17.0% vs 4.9–8.0%), lung (7.9–13.0% vs 3.0–5.0%), cardiovascular (18.0–25.5% vs 16.0–19.0%), and metabolic disorders (17.3–19.0% vs 13.5–15.0%) versus controls. Based on further tests, there were 21.6%, 19.7% and 23.0% with swollen parotid gland; 89.1%, 88.3% and 90.4% with dry eye syndrome; 60.8%, 55.9% and 29.6% with positive parotid sialography; 30.0%, 23.5% and 21.2% with positive minor salivary glands in the testing, internal validation and external validation cohorts, respectively.

NDT cohort = patients from Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, the affiliated hospital of Nanjing University Medical School. SMH cohort = patients from Suzhou Municipal Hospital, the affiliated Suzhou hospital of Nanjing Medical University. HFPH cohort = patients from the Huai’an First People’s Hospital, the affiliated Huai’an No. 1 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University.

Feature selection strategy and optimization outcomes

The construction of SMFIF model adopts the method of a multi-criterion feature integration framework (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 3). Initially, the optimal features and intersecting features were selected through feature selection algorithms for model construction. A detailed evaluation of the performance of the models and the SHAP dependence plots of the relevant features is provided in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Tables 5–11; Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). The SHAP values computed for the ML models built using all features are shown (Fig. 3A–G), while the performance of the seven models is summarized in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Table 4). Correlation analysis revealed significant relationships among most features (Fig. 3H). Through the above analysis (refer to the Methods section), 16 core features were identified and selected as the final input for SMFIF: Creatinine (Crea), γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT), Uric acid (UA), Total protein (TP), Apolipoprotein AI (apoAI), Alanine transaminase (ALT), Phosphorus (P), Adenosine deaminase (ADA), Glucose (Glu), Direct bilirubin (DBIL), Chloride ion (Cl−), Globulin (GLO), Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR), High density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and Complement 4 (C4). The SHAP dependence plots for these features are included in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Fig. 3).

The SMFIF model was developed using a systematic approach, involving meticulous preprocessing of clinical and laboratory data, feature selection with six methods, and the creation of 42 feature-model combinations. After refining feature subsets, a final set of 16 key features was identified and used to train seven classifiers. The top five models were selected for ensemble construction using a weighted approach, and the model’s performance was rigorously validated with internal and external datasets.

a Gaussian Naive Bayes, b K-Nearest Neighbors, c Light Gradient Boosting Machine, d Logistic Regression, e Random Forest, f Support Vector Machine, g Extreme Gradient Boosting, h Pearson correlation coefficients between the included features. Red represents a positive correlation between the two features. The redder the colour is, the higher the positive correlation coefficient is. Blue represents a negative correlation. The bluer the colour is, the higher the negative correlation coefficient is. All the features were clustered into two groups according to the correlation. TP Total protein, GLO Globulin, apoB Apolipoprotein B, TC Total cholesterol, LDL-C Low density lipoprotein cholesterol, apoA1 Apolipoprotein AI, HDL-C High density lipoprotein cholesterol, ALB Albumin, Ca2+ Calcium, A/G Albumin to globulin ratio, Cl− Chloride ion, Na+ Sodium ion, C3 Complement 3, C4 Complement 4, CysC Cystatin C, Cr Creatinine, Ur Urea, BUN Blood urea nitrogen, Mg2+ Magnesium ion, TG Triglycerides, K+ Potassium ion, P Phosphorus, UA Uric acid, eGFR Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate, ChE Cholinesterase, C1q Cholinesterase, IgM Immunoglobulin M, RF Rheumatoid factor, IgA Immunoglobulin A, IgG Immunoglobulin G, Ig E Immunoglobulin E, ALT Alanine transaminase, LDH Lactate dehydrogenase, AST Aspartate transaminase, CRP C-reactive protein, Glu Glucose, TBIL Total bilirubin, DBIL Direct bilirubin, ADA Adenosine deaminase, ALP Alkaline phosphatase, GGT γ-glutamyl transferase.

In our study, 16 features were finally used to calculate the comprehensive performance indicators of each classifier in all datasets. Compare and analyse the top five classifiers with the highest performance as base classification models, integrated into a stacked ensemble learning model (Supplementary Table 12). This ensemble model synthesises predictions from meta classifiers and ultimately constructs the SMFIF model. To rigorously evaluate the performance of the SMFIF model, five-fold and ten-fold cross-validation and 95% CI analysis were performed on all performance evaluation metrics of the model. SMFIF model has been made publicly available via GitHub.

Performance of the SMFIF model and multicenter validation results

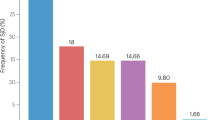

The SMFIF model showed exemplary predictive ability in discriminating patients with SjD from those with SjD-like manifestations without SjD. The AUC for the test set was 0.923 (95% CI, 0.923–0.935), for the internal validation set was 0.934 (95%CI, 0.929–0.939) and for the external validation set was 0.964 (95%CI, 0.943–0.986) (Table 2). The SMFIF model showed superior and more stable performance compared to all previously established models, especially in terms of AUC, accuracy and specificity. In addition, a comparative analysis was performed between 16 feature-based SMFIF and the independent conventional marker-based SMFIF. The results showed that 16 feature-based SMFIF outperformed those based on ANA (AUC: 0.709; 0.728–0.846), SSA (AUC: 0.705; 0.703–0.699), SSB (AUC: 0.575; 0.569–0.583), RF (AUC: 0.506; 0.506–0.529), GLO (AUC: 0.688; 0.690–0.592), IgG (AUC: 0.677; 0.685–0.740), C3 (AUC: 0.672; 0.682–0.736) and C4 (AUC: 0.671; 0.683–0.621) in testing, internal validation and external validation, respectively (Fig. 4).

The calibration curves for the testing set, internal validation set, and external validation set demonstrate a generally good agreement between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes, indicating that the SMFIF model is well-calibrated across different datasets. Notably, the calibration curves for the testing and internal validation sets show a high degree of consistency, suggesting strong generalizability of the model to unseen data. However, the calibration curve for the external validation set exhibits greater variability, indicating potential challenges in adapting to external data distributions. In terms of classification performance, the confusion matrices across the testing, internal validation and external validation data sets consistently show high sensitivity and specificity with minimal false classifications, highlighting the robust and reliable diagnostic performance of the model across all evaluation phases (Fig. 5).

Overall, these results indicate that the SMFIF model provides robust and reliable probabilistic predictions with strong diagnostic performance. Nevertheless, while the model generalizes well to internal validation and testing data, its performance on external validation data suggests that further refinement may be needed to enhance sensitivity when applied to different external conditions.

Discussion

In this multicenter retrospective study, we screened 70 features from 123 routine blood test results through data preprocessing. By multi-algorithm feature selection, SHAP value analysis, model performance evaluation, and ensemble learning strategies, we developed the SMFIF model based on 16 optimal features for accurate SjD diagnosis and prediction, the SMFIF achieved consistent and good performance both in the internal set and the external validation sets, and outperformed anti-SSA/Ro, anti-SSB/La, ANA in identifying SjD-like individuals with atypical symptoms. The model was developed into a user-friendly prediction tool, which is publicly available and provides an estimated probability of SjD based on routine laboratory test results. To our knowledge, this study presents the first AI machine learning model developed for diagnosing SjD using big data in clinical practice.

The prevalence of SjD varies widely in the population. Due to the lack of typical early symptoms and its slow progression, especially when combined with smoking, diabetes, menopausal syndrome, or infection, clinicians in primary care settings fail to identify the primary disease. As a result, patients may already have interstitial lung disease, arthritis, polyneuropathy or even malignancies when a SjD diagnosis is made, leading to delays in treatment of the primary disease in SjD. One advantage of the SMFIF model is that it provides clinicians with a tool that can help them identify patients who potentially have SjD, especially in primary care settings where routine physical examinations or clinical experience with rheumatological diseases is limited. Compared with SMFIFANA, SMFIFanti-SSA/Ro, SMFIFanti-SSB/La and SMFIFRF/Glo/IgG/C3/C4, the combination of laboratory tests and autoantibodies contained in SMFIF has improved predictive performance, as indicated by the increased AUC and sensitivity, with a much lower cost than conventional autoantibodies, labial gland biopsy, parotid sialography or ultrasonography, tear flow rate and corneal fluorescein staining.

One important factor in the generalisability and stability of our prediction model is the representativeness of the data. We first trained, tested, and internally validated the model using data from a large regional hospital, and selected two independent local mergers as primary care providers for external validation. In the three cohorts, the median age at diagnosis of SjD was 52–56 years, which is representative of the Chinese and other Asian populations24,25. Another important factor in improving the predictive performance of the model is our proposed multi-criterion feature integration strategy. The approach not only ensures the identification of the most relevant and robust features but also significantly enhances the model’s interpretability and generalizability. By systematically integrating the results from multiple feature selection algorithms and SHAP-based evaluations, we derived a final feature set comprising 16 key features. Such optimization effectively minimizes feature redundancy while maximizing the predictive power of the selected features. It is worth noting that our final 16-feature model—which primarily includes non-classical immune biomarkers of liver, kidney, and metabolic function—reflects both the data-driven feature selection process and the systemic pathophysiological characteristics of SjD. Although baseline analysis revealed significant differences between the control and the SjD group in terms of classical immune biomarkers, multivariate feature selection prioritised conventionally available and cost-effective indicators after rigorous multi-algorithm filtering and SHAP-based ranking. Most cases in the control group were clinically suspected of SjD but were ultimately diagnosed with various chronic diseases, ensuring the model could distinguish SjD from complex non-autoimmune diseases rather than healthy states. Additionally, the SjD group exhibited higher actual organ involvement (co-morbid conditions) compared to the control group, indicating that autoimmune disease-specific biochemical abnormalities play a critical role in disease progression, while the value of routine blood tests may be significantly underestimated.

Further, to enhance interpretability in ambiguous cases, we incorporated patient-level SHAP decision plots to illustrate how the SMFIF model makes predictions. We analysed all misclassified samples and visualized representative cases from the false negative (FN) and false positive (FP) groups (Supplementary Fig. 5). Notably, many of the FN cases exhibit atypical values for canonical SjD indicators, but these were overridden by strong negative contributions from renal or hepatic function markers, thereby leading to a non-SjD prediction. In contrast, some FP cases present borderline elevations in immune-related indicators, which could reasonably lead to model suspicion of SjD.

Given the development of big data in genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, imaging, therapeutics, and electronic health records (EHRs), machine learning models are extremely attractive in the field of rheumatic diseases such as SLE and RA26,27. A few studies have been already conducted in SjD. Dros et al. developed a classification model using primary care electronic health records (EHRs) data and hospital claims data (HCD) from 1411 SjD patients. The AUC of logistic regression (LR) and random forest (RF) was 0.82 and 0.84, respectively28. Troncoso et al. utilize an auto-machine learning (autoML) platform for the automated segmentation and quantification of Focus Score (FS) on histopathological slides, aiming to augment diagnostic precision and speed in SS29. Marlin et al. developed an AI-enabled algorithm that automatically identifies key histological features of the minor salivary gland of SS patients30. Wu et al. developed a graph-learning-based model named Cell-tissue-graph-based pathological image analysis model for automatic diagnosis of SS31. Marugán et al. applied ML methodologies to classify SLE and SjD patients and designed an analysis pipeline to train an eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) multiclass predictor for each type of data32. However, all published studies above were limited by the inclusion of only general basic information or a single pathological type, small cohort sizes, and lack of external validation. In contrast, our study was conducted on a large-scale multicentre dataset that included multiple routine laboratory tests, autoantibodies, minor salivary gland function assessments and pathological types of labial gland biopsies. The clinical utility of SMFIF depends on its ability to distinguish SjD not only from healthy individuals but, more importantly, from patients with other immune-mediated and chronic conditions. We additionally applied the 16-feature model to four comparator conditions using database from DTH. The results demonstrate that SMFIF effectively distinguishes SjD from RA (AUC = 0.8336), SLE (AUC = 0.8896), SSc (AUC = 0.8416), and osteoarthritis (AUC = 0.9149) (Supplementary Table 13 and Supplementary Fig. 4). We interpret the strong performance against RA, SLE, SSc, and osteoarthritis (OA) as evidence that SMFIF captures a signature relatively specific to SjD pathology compared to these distinct inflammatory and non-inflammatory (OA) rheumatic disorders, significantly enhancing its potential clinical utility for differential diagnosis. The SMFIF modelling process used multi-algorithm feature selection, SHAP value analysis, model performance evaluation, and ensemble learning strategies, which has advantages over traditional logistic regression models, and was validated by an independent external large cohort, making the results more reliable.

Our study has several limitations. First, SMFIF was not evaluated in a prospective cohort. Second, loss of data was inevitable in this real-world retrospective study. Third, due to data-sharing restrictions and annotation costs, the cohort was exclusively derived from three Chinese hospitals, representing a single-nation dataset. This necessitated reliance on a second independent external validation cohort within the same healthcare system. These constraints collectively limit the extrapolation of our findings to other ethnic populations or distinct healthcare settings. Furthermore, outpatient recruitment was confined to two local hospitals, resulting in imbalanced sample sizes between internal and external validation sets. The model’s generalizability across other countries and regions requires further investigation, including validation with more patients from primary care settings to confirm its broader utility. Future multinational studies are essential to establish the model’s global applicability. Fourth, multimodal features such as clinical symptoms, medical history characteristics, image characteristics, and genetic characteristics were not included. Finally, it must be acknowledged that the clinical application of the developed model still faces challenges due to practical considerations such as ethnic diversity, the attribution of clinical use, and full transparency of the decision-making process. Prospective cohorts, improved annotation of multimodal data, and more reasonable regulations for artificial intelligence are required to ensure better application of SMFIF.

In summary, SMFIF based on 16 key features of routine laboratory items achieved satisfactory and stable performance and was significantly better than the traditional markers SSA/Ro, SSB/La and ANA. This model provides a low-cost, accessible and accurate diagnostic tool for SjD. Prospective studies and data sets from other regions are needed to further confirm the feasibility and generalizability of SMFIF.

Methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective, multicentre study screened 198,922 laboratory examinations from three hospitals in China between Jan 1, 2013, and Jan 1, 2023. The 123 laboratory items were selected based on the tests’ universality in routine clinical use by rheumatologists (Supplementary Table 1). The training (testing) set was selected from a large-scale regional centre hospital, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (NDT cohort). The external validation set was selected from two local hospitals, Suzhou Municipal Hospital (SMH cohort) and Huai’an First People’s Hospital (HFPH cohort). All participants recruited were aged between 18 and 65 years and underwent pathological, haematological and imaging tests to confirm the presence of SjD. Laboratory tests were measured from one month before diagnosis to any treatment. Patients diagnosed with Sjögren’s disease were included in the SjD group, while the control group comprised sex- and age-matched individuals exhibiting similar or suspected Sjögren-like symptoms, such as dry mouth and eyes, fatigue, joint pain, and weight loss, but who were excluded on screening for SjD and other autoimmune diseases. The study excluded cases of combined pregnancy, breastfeeding, a clear diagnosis of other autoimmune diseases, infection and malignant tumours. The diagnosis of SjD is based on an assessment by at least two rheumatologists using the 2002 American-European Consensus Group (AECG) or 2016 ACR/EULAR classification criteria15,16. Meeting any one of the two classification criteria is considered a definite diagnosis.

Ethical statement

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (B2022-529-04), the Medical Ethics Committee of the First People’s Hospital of Huai’an City (YX-Z-2024-032-01), and the Medical Ethics Committee of the Suzhou Municipal Hospital (K-2022-074-K03). The study complied with the ethical principles of Declaration of Helsinki of 1975. All case data were anonymised, and the Institutional Review Board waived the requirement for written informed consent. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Registration number: NCT06982482, Date of registration: May 13, 2025, Registry name: Artificial Intelligence Based Models for Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome Diagnosis). A copy of the study protocol can be found in supplemental file.

Data preprocessing

Laboratory items with different units were unified. Characteristics of study cohorts in which more than 50% of missing data in each row were removed from analysis and more than 80% of missing data in each column after cleaning were removed. After data cleaning, missing values were imputed using the random forest imputation method, which leverages predictive modelling to estimate missing entries based on available features. To minimize institutional bias introduced by the multicenter nature of the dataset, we implemented a harmonization procedure prior to modeling. Laboratory items from the three centres were first aligned using a shared data dictionary, ensuring consistent variable naming, definitions, and measurement units33. Additionally, we visually inspected the distributions of key variables across cohorts and applied min-max normalization to reduce centre-specific variability34. Data imbalance was resolved via the adaptive synthetic sampling method with a balancing ratio of 0.535.

Predictive modelling

After data preprocessing, the 70 laboratory items were used as the candidate features for the model building. The predictive model for SjD diagnosis was developed using a structured, methodologically rigorous framework (Fig. 2). Six feature selection algorithms were first applied to identify optimal feature subsets, which were then input into seven machine learning classifiers to calculate SHAP values, quantifying feature importance. After the first step of screening, 41 candidate features were obtained. To strengthen model robustness, the intersection of features from six algorithms formed a core feature set. Meanwhile, the performance of all features was assessed by constructing models using the seven classifiers, followed by ranking features based on their SHAP values. By integrating all feature sets, optimal feature subsets and the core feature set with SHAP-based rankings, and a final set of 16 significant features was established. To enhance the reliability of the features incorporated into the final model, we computed the Pearson correlation matrix for all candidate features. No pair of features exceeded the commonly accepted threshold of r > 0.90. Additionally, we calculated the Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) for the features. Eleven features had a VIF of less than 5, and five features (apoA1, HDL, DBIL, TP and GLO) had a VIF between 5 and 10; the latter were retained due to their distinct clinical relevance. This achieves control over multicollinearity. The predictive model was then built using this curated set and trained with multiple classifiers. The top five performing models were selected as base classifiers and integrated into a stacking ensemble learning model, SMFIF, which employs a meta-classifier to further improve accuracy36. The model’s generalizability and accuracy were validated using both internal and external datasets, demonstrating its potential for clinical application. The model’s generalizability and accuracy were validated using both internal and external datasets, demonstrating its potential for clinical application.

Performance evaluation

The performance of the SMFIF model was assessed by using seven significant metrics: area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy (ACC), recall, F1-score, positive predicted value (PPV), specificity, and negative predictive value (NPV). Independent classification models were constructed using feature inputs derived from the anti-SSA/Ro antibodies, anti-SSB/La antibodies, ANA, RF, GLO, IgG, C3, and C4 datasets, and their performance was compared to that of the SMFIF model. The evaluation of the SMFIF model was further augmented with calibration curves and confusion matrices to assess its clinical utility and reliability.

Feature evaluation

The primary outcome was the prediction accuracy of the model in identifying SjD, based on an optimally selected feature set to ensure the best predictive performance. The SHAP method was used to analyse the contribution of each feature in order to quantify its relative importance. The diagnostic performance of the SMFIF was found to be heavily influenced by the selection of input features. To optimize the model, 16 significant features were identified and prioritized based on their frequency of selection and importance rankings across all classification models.

Statistical analysis

Patient data were analysed separately for continuous and categorical variables, with results reported as median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and frequency (%) for categorical variables. Comparisons of continuous variables between groups were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test, while categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. A P-value < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, X.Y. Please note that patient personal information and correspondence will not be shared, as they are protected by the corresponding authors’ institutions to ensure patient privacy.

Code availability

Data analysis was conducted using R software (Version 4.3.2) and Python (Version 3.7). The core code for the research can be found on the corresponding author’s GitHub page (https://github.com/guanhaowu123/SMFIF).

References

Mariette, X. & Criswell, L. A. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 931–939 (2018).

Ramos-Casals, M. et al. 2023 International Rome consensus for the nomenclature of Sjögren disease. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 21, 426–437 (2025).

Belenguer, R. et al. Influence of clinical and immunological parameters on the health-related quality of life of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 23, 351–356 (2005).

Beydon, M. et al. Epidemiology of Sjögren syndrome. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 20, 158–169 (2024).

Asmussen, K., Andersen, V., Bendixen, G., Schiødt, M. & Oxholm, P. A new model for classification of disease manifestations in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: evaluation in a retrospective long-term study. J. Intern. Med. 239, 475–482 (1996).

Huang, H., Xie, W., Geng, Y., Fan, Y. & Zhang, Z. Mortality in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology 60, 4029–4038 (2021).

Gairy, K., Knight, C., Anthony, P. & Hoskin, B. Burden of illness among subgroups of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome and systemic involvement. Rheumatology 60, 1871–1881 (2021).

Seror, R. et al. Outcome measures for primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a comprehensive review. J. Autoimmun. 51, 51–56 (2014).

Pego-Reigosa, J. M., Restrepo Vélez, J., Baldini, C. & Rúa-Figueroa Fernández de Larrinoa, Í. Comorbidities (excluding lymphoma) in Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatology 60, 2075–2084 (2021).

Chatzis, L. G. et al. Clinical picture, outcome and predictive factors of lymphoma in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: results from a harmonized dataset (1981-2021). Rheumatology 61, 3576–3585 (2022).

Wang, B. et al. Early diagnosis and treatment for Sjögren’s syndrome: current challenges, redefined disease stages and future prospects. J. Autoimmun. 117, 102590 (2021).

Abrol, E., González-Pulido, C., Praena-Fernández, J. M. & Isenberg, D. A. A retrospective study of long-term outcomes in 152 patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome: 25-year experience. Clin. Med. 14, 157–164 (2014).

Soret, P. et al. A new molecular classification to drive precision treatment strategies in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Nat. Commun. 12, 3523 (2021).

Rasmussen, A. et al. Previous diagnosis of Sjögren’s Syndrome as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 55, 1195–1201 (2016).

Shiboski, C. H. et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism classification criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a consensus and data-driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol. 69, 35–45 (2017).

Vitali, C. et al. Classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 61, 554–558 (2002).

Retamozo, S. et al. Influence of the age at diagnosis in the disease expression of primary Sjögren syndrome. Analysis of 12,753 patients from the Sjögren Big Data Consortium. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 39, 166–174 (2021).

Ramos-Casals, M. et al. Systemic involvement in primary Sjogren’s syndrome evaluated by the EULAR-SS disease activity index: analysis of 921 Spanish patients (GEAS-SS Registry). Rheumatology 53, 321–331 (2014).

Baldini, C. et al. Primary Sjogren’s syndrome as a multi-organ disease: impact of the serological profile on the clinical presentation of the disease in a large cohort of Italian patients. Rheumatology 53, 839–844 (2014).

Maślińska, M., Mańczak, M. & Kwiatkowska, B. Usefulness of rheumatoid factor as an immunological and prognostic marker in PSS patients. Clin. Rheumatol. 38, 1301–1307 (2019).

Scofield, R. H., Fayyaz, A., Kurien, B. T. & Koelsch, K. A. Prognostic value of Sjögren’s syndrome autoantibodies. J. Lab Precis. Med. 3, 10-21037 (2018).

Nocturne, G. et al. Rheumatoid factor and disease activity are independent predictors of lymphoma in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68, 977–985 (2016).

Tzioufas, A. G., Boumba, D. S., Skopouli, F. N. & Moutsopoulos, H. M. Mixed monoclonal cryoglobulinemia and monoclonal rheumatoid factor cross-reactive idiotypes as predictive factors for the development of lymphoma in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 39, 767–772 (1996).

Qin, B. et al. Epidemiology of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 1983–1989 (2015).

Ji, J., Sundquist, J. & Sundquist, K. Gender-specific incidence of autoimmune diseases from national registers. J. Autoimmun. 69, 102–106 (2016).

Munguía-Realpozo, P. et al. Current state and completeness of reporting clinical prediction models using machine learning in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Autoimmun. Rev. 22, 103294 (2023).

Danieli, M. G. et al. Machine learning application in autoimmune diseases: state of art and future prospectives. Autoimmun. Rev. 23, 103496 (2024).

Dros, J. T. et al. Detection of primary Sjögren’s syndrome in primary care: developing a classification model with the use of routine healthcare data and machine learning. BMC Prim. Care 23, 199 (2022).

Álvarez Troncoso, J. et al. Classification of salivary gland biopsies in Sjögren’s syndrome by a convolutional neural network using an auto-machine learning platform. BMC Rheumatol. 8, 60 (2024).

Marlin, M. C. et al. AB0802 AI-Enabled tissue classifier for Sjogren’s disease salivary gland identifies key histological features important for understanding disease manifestation. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 83, 1695 (2024).

Wu, R. et al. A graph-learning based model for automatic diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome on digital pathological images: a multicentre cohort study. J. Transl. Med. 22, 748 (2024).

Martorell-Marugán, J., Chierici, M., Jurman, G., Alarcón-Riquelme, M. E. & Carmona-Sáez, P. Differential diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome using machine learning and multi-omics data. Comput Biol. Med. 152, 106373 (2023).

Pezoulas, V. C. et al. Addressing the clinical unmet needs in primary Sjögren’s syndrome through the sharing, harmonization and federated analysis of 21 European cohorts. Comput Struct. Biotechnol. J. 20, 471–484 (2022).

Box, G. E. P. & Cox, D. R. An Analysis of Transformations. J. R. Stat. Soc.: Ser. B (Methodol.) 26, 211–243 (1964).

Haibo, H., Yang, B., Garcia, E. A. & Shutao, L. ADASYN: adaptive synthetic sampling approach for imbalanced learning. In 2008 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence); 1–8 June 2008, 1322–1328 (2008).

Pavlyshenko, B. Using stacking approaches for machine learning models. In 2018 IEEE Second International Conference on Data Stream Mining & Processing (DSMP); 21–25 Aug 2018, 255–258 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of Yidu Cloud Technology Company and the Hospital Information Management System platform for routine clinical data maintenance and export. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82572066, 81901649), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20251723, BK20250237), and Jiangsu Health International Exchange Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. and G.W. designed the study and wrote the main manuscript. M.P. collected the clinical data and loaded the data into the database. Q.S. and C.G. analysed and interpreted the data. X.L. and C.T. provided external validation data sets. X.Y. and L.S. checked all results and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Wu, G., Pan, M. et al. A multi-criterion feature integration framework for accurate diagnosis of Sjögren’s disease using routine laboratory tests. npj Digit. Med. 8, 729 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02110-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02110-2