Abstract

The effectiveness of mHealth interventions to reduce child unintentional injuries in resource-limited areas like rural areas remains poorly understood. This study aims to assess the effectiveness of a theory-driven and culturally-adapted app intervention to reduce unintentional injury incidence among rural preschoolers. A 12-month single-blinded cluster randomized controlled trial (Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, ChiCTR2000037606, registered on August 29, 2020) was conducted among 3836 preschoolers and their caregivers from 24 preschools in rural China. Participating preschools were randomly allocated using a 1:1 ratio to the intervention or control group to receive app-based education including or excluding child injury prevention. Primary outcome was the 12-month preschooler unintentional injury incidence. Secondary outcomes included caregiver’s safety-related attitudes, supervision behaviors, and home environment scores. Of the 3836 enrolled participants, 3338 (87.0%) completed the study. Results demonstrated the intervention significantly reduced preschooler unintentional injury incidence (aRR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.86, 0.98) and improved caregivers’ safety-related attitudes (b = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.32, 0.73), supervision behaviors (b = 3.83, 95% CI: 3.15, 4.46), and home environment (b = 3.38, 95% CI: 2.51, 4.16). This trial suggests the app-based intervention effectively enhances child safety among rural preschoolers, and could be disseminated broadly in China and tailored to other resource-limited settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Child unintentional injuries have been a global health challenge for decades1. In 2021, approximately 188,000 children under age five years died from unintentional injuries globally, 84% of whom lived in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)2. There are disparities in child unintentional injury burden, with injury risk likelihoods greater among rural residents and underserved minority populations, even in high-income countries3. In China, where the current study was conducted, unintentional injury mortality was much higher among rural children ages under one year (20.1 vs. 15.0/100,000 population) and one to four years (12.2 vs. 7.7/100,000 population) than among urban children in 20214.

Disparities in rural areas are at least partially the result of a failure to identify strategies to deliver known and effective injury intervention programs to underserved populations5. Among the strategies recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) to deliver health-related education, educational interventions offer a low-cost and feasible strategy that can reach large numbers of people. In particular, interventions that leverage theory-driven strategies to achieve behavior change are recommended. In the domain of child injury prevention, these strategies should alter caregivers’ perceptions regarding children’s vulnerability to injury and promote adoption of low-cost and effective safety equipment and practices6.

Traditional education interventions such as posters, pamphlets, and lectures demonstrate mixed effectiveness in meta-analytic reviews and are difficult to implement in underdeveloped rural areas where trained injury prevention and public health professionals are uncommon and financial resources are limited5. Mobile health (mHealth) technologies offer a promising alternative to deliver accessible, theory-driven, and low-cost health-related education programs for underserved rural populations to promote health without geographic restrictions7.

Nine published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assess the effectiveness of mHealth educational interventions to reduce child unintentional injury risk. Of those, eight examined knowledge, attitudes, and/or behaviors as primary outcome measures rather than actual injury events8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. The only published study that considered injury incidence rate as the primary outcome assessed effectiveness of the mHealth intervention over a six-month follow-up period and was conducted with a sample of caregivers living in an urban area16. In addition, descriptions of previous mHealth intervention studies to reduce child injury risks reported multiple challenges that needed to be addressed in novel mHealth programs, including user fatigue, low engagement, non-compliance, and participant withdrawal10,13,14,16,17.

We developed a theory-driven, user-friendly, and culturally-adapted mHealth program that was delivered by smartphone app to prevent preschooler unintentional injuries in rural China. The program was guided based on the app development framework18 and aligned with the practical characteristics, needs, and contextual realities of rural Chinese caregivers to address major causes of unintentional injury risk among rural Chinese preschoolers19. This report describes our evaluation of the effectiveness of the app intervention to reduce the preschooler unintentional injury incidence rate in rural China through a 12-month cluster RCT.

Results

Sample characteristics and intervention engagement

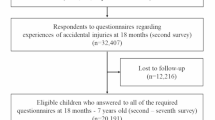

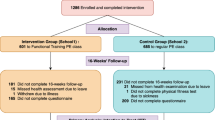

A total of 3836 eligible preschooler caregivers were recruited from 24 preschools in rural China, 12 from Changsha County, and 12 from Yang County. Caregivers were randomized into two groups in clusters based on preschool, with 1938 in the intervention group and 1898 in the control group (Fig. 1). For both groups combined, 3338 caregivers (1662 in the intervention group and 1676 in the control group) completed the 12-month follow-up, yielding a retention rate of 87.0%.

Socio-demographic characteristics among preschoolers and caregivers are presented in Table 1 by randomized group. During the 12-month follow-up period, the mean number of app logins was 44.7 (standard deviation (SD): 69.4) for the intervention group and 44.6 (SD: 73.9) for the control group (P = 0.98). The mean overall app-using time was 399.1 minutes (SD: 957.6 min) and 381.8 min (SD: 1005.3 min) for the two groups, respectively (P = 0.61).

During the 12-month follow-up period, both groups displayed highly similar injury epidemiological characteristics. For the two groups combined, falls (incidence: 33.9%, 95% CI: 32.3%, 35.6%) and blunt force injuries (incidence: 15.2%, 95% CI: 13.9%, 16.4%) were the two leading causes of unintentional injuries, together accounting for 86.5% of all injuries. 71.4% of injuries occurred at home; 77.9% happened while playing; and 58.9% were mild injuries that received no treatment but required stay-at-home rest for half a day or longer, or received simple treatment by non-medical personnel like a family member.

Unintentional injury incidence rate

At baseline, the 12-month unintentional injury incidence rate prior to the intervention was 37.9% (95% CI: 35.5%, 40.2%) in the intervention group and 36.0% (95% CI: 33.7%, 38.3%) in the control group, a difference of 1.9% (95% CI: −1.4%, 5.1%). During the 12-month follow-up period, the unintentional injury incidence rate was 52.7% (95% CI: 50.3%, 55.1%) in the intervention group and 53.5% (95% CI: 51.1%, 55.9%) in the control group, a difference of -0.8% (95% CI: −4.1%, 2.6%). The intra-cluster correlation coefficient at the preschool level was 0.08 for unintentional injury incidence.

After adjusting for socio-demographic variables, engagement variables, and baseline 12-month child injury incidence rates, the intervention group had a significantly lower 12-month unintentional injury incidence rate than the control group (aRR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.86, 0.98) (Fig. 2).

Subgroup analyses showed the significant reductions in unintentional injury incidence among caregivers with an education level of junior high school and below (aRR = 0.84, 95% CI: 0.80, 0.92), caregivers who used other parenting apps 3–6 times per week at baseline (aRR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.65, 0.93), and caregivers who had not learned about child injury prevention in the 3 months prior to baseline (aRR = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.83, 0.94) (Supplementary Table 1).

Cause-specific post-hoc analyses showed slightly higher incidence rate for falls (aRR = 1.17, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.30) but a much lower rate for blunt force injuries (aRR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.54, 0.77) in the intervention group compared to the control group after the 12-month intervention. Details are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Scores of attitudes, supervision behaviors, and home environment

At baseline, mean differences in the secondary outcome score across groups were all insignificant: attitudes (0.11, 95% CI: −0.07, 0.28), supervision behaviors (0.84, 95% CI: −0.05, 1.73), home environment (−0.11, 95% CI: −0.82, 0.61). At the 12-month follow-up, all differed significantly (0.27, 95% CI: 0.12, 0.42; 3.58, 95% CI: 2.94, 4.23; and 3.63, 95% CI: 2.94, 4.31, respectively) (Fig. 3). Descriptive data for the secondary outcome measures at baseline and the four follow-ups are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

After adjusting for socio-demographic variables, engagement variables, and baseline values of relevant secondary outcome variables, the mean scores of attitudes, supervision behaviors, and home environment at the 12-month follow-up were all significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group, with adjusted partial regression coefficients (b) of 0.51 (95% CI: 0.32, 0.73), 3.83 (95% CI: 3.15, 4.46), and 3.38 (95% CI: 2.51, 4.16), respectively. Item-level analyses showed significant differences in mean scores between the two groups for all three attitude items, 21 of the 22 supervision behavior items, and 15 of the 16 home environment items (Supplementary Figs. 1–11).

Sensitivity analyses

The prespecified sensitivity analyses demonstrated highly similar results for both primary and secondary outcomes, as presented in Supplementary Tables 3–4.

Discussion

This study conducted a cluster RCT to assess the effectiveness of a theory-driven and culturally-adapted app intervention to reduce injuries among rural preschoolers in China. Two primary findings emerged: (a) the app intervention reduced preschooler unintentional injury incidence throughout the 12-month follow-up period (aRR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.86, 0.98), and (b) the app intervention improved caregivers’ attitudes and supervision behaviors regarding child unintentional injury prevention (b = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.32, 0.73 and b = 3.83, 95% CI: 3.15, 4.46), as well as home environment safety (b = 3.38, 95% CI: 2.51, 4.16).

Previous mHealth RCTs on child injury prevention generally assessed intermediate outcomes (e.g., attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors)8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 rather than using actual injury events as an outcome. The most directly comparable trial, which we conducted in an urban setting16, reported an insignificant unintentional injury incidence reduction after a 6-month intervention in urban China. Accordingly, our results extend previous research8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 in two critical ways. First, we designed and implemented the mHealth intervention to reduce child unintentional injury risk among an underserved and at-risk population - preschoolers and their families in rural China. Second, we extended previous methodological evaluation strategies, which relied primarily on self-reported measures of attitudes or behaviors to evaluate effectiveness, by conducting a cluster RCT with injury incidence rate over a 12-month period as the primary outcome measure. The present results of our intervention, which was specifically tailored for rural Chinese caregivers, proved the effectiveness is remarkable, demonstrating the importance of tailoring interventions to the needs of the target population and representing a new revelation in this context.

The app intervention was successful in reducing child injury risk. One factor that likely contributed to its success was the development of the app to follow principles of effective health behavior interventions for injury prevention as recommended20, including being theory-driven, socio-culturally relevant, delivered appropriately, using varied and effective teaching methods, delivering a sufficient dosage of the intervention to convey information and keep users engaged, and having well-trained staff available to support implementation. Consistent with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), our app was designed to increase basic knowledge about safety, impact attitudes and behaviors (including improvements on both adult supervision and home environment safeguard), and consequently increase children’s safety and reduce injury incidence21.

The intervention was also likely successful because it incorporated use of external support strategies to increase intervention engagement. Building from lessons learned from last trial in urban China16 and recommendations from previous research22, preschool teachers and staff were engaged with participants to provide face-to-face assistance throughout the trial, for example by helping caregivers download and operate the app. As a result, along with our tailoring of the app to be culturally adaptative and user-friendly to the target population, app usage time was more than double that reported in a trial of the precursive app with urban preschoolers (390.4 vs. 150.5 min16) and attrition in this study was significantly lower than rates reported previously (13.0% vs. 51.0%10, 79.1%13, 34.3%14, and 32.2%16).

Although the study results suggest the intervention led to significant injury incidence rate differences between two groups, the effect size was modest. Multifaceted efforts are needed to reduce child injury risk1, and the intervention would be best used in conjunction with other efforts by caregivers as well as safer engineering of child-related products, governmental policies to promote child safety, and other empirically-supported strategies. It is also important to consider the significant public health impact of the app amidst the context of the number of rural preschoolers living in China. Approximately 44 million children aged 3 to 6 years old live in rural areas of China23. With an estimated annual incidence rate reduction of 0.8% from this study, if all rural caregivers used the app, it would create an estimated decrease of at least 352,000 unintentional injuries annually. This impact would create substantial emotional and economic benefit to children, their families, and society, including a reduction in lost school days for children, prevented lost wages for caregivers living with modest incomes, and reduced emotional burden of pediatric injuries. Furthermore, we envision extending public health significance and sustainability by tailoring the app to rural children living in other nations, and to children in other age groups. If the app was tailored to rural Chinese children across all ages, for example, it could annually prevent 1.51 million unintentional injuries to the 189 million rural Chinese children under 18 years old23.

Practical significance of the app was achieved by feasibly promoting changes at the individual caregiver level. Our app intervention represented a flexible, “anytime and anywhere” micro-learning approach for rural caregivers, requiring only about 3 min of daily engagement. This low-burden strategy of intervention facilitated consistent engagement and possessed high practicality for long-term use in daily routines, leading to meaningful improvement in safety-related attitudes, supervision behaviors, and home environment, which collectively are assumed to contribute to the observed reduction in injury incidence.

We can approximate the financial cost of the intervention at about $500 per prevented injury over the one-year study period, with costs including app modification, system maintenance, content production, participant incentives, and external supports. While this figure is specific to our research context, the cost-effectiveness would improve substantially with scalability and sustainability; as a digital platform, the initial development costs are fixed. Given the popularity of the wireless internet and the reusability of all educational materials, deploying the app to a larger population (e.g., 100,000 users) would be highly feasible through mobile health technology, and operational costs would not increase proportionally. This scalability potential enhances the intervention’s practical value from a public health perspective.

One surprising result from the study was that the 12-month unintentional injury incidence rates we observed for both groups during the follow-up period (52.7% and 53.5% for intervention and control groups, respectively) were much higher than those at the baseline survey (37.9% and 36.0%, respectively) and compared to previous research adopting a similar operational definition (15.6%24, 24.8%25, and 32.3%26). Notably, the increases in child unintentional injury incidence rate were consistent with reports by three previous studies completed during the COVID-19 pandemic27,28,29, but the result might be explained by a combination of three factors. First, the different recall period of injury rates reported at baseline versus after the intervention might primarily explain the result. The baseline survey was conducted over a 12-month recall period, a methodological strategy that may have led to greater recall bias compared to the post-intervention reporting, which was conducted based on 3-month recall period in each of four follow-up surveys. Self-report of injuries over longer time periods is documented to create more bias in reporting30,31,32.

Second, enforced strict social isolation measures during the COVID-19 pandemic may have created elevated incidence rates in both groups. During the COVID-19 pandemic, which overlapped with data collection, China implemented a strict social isolation policy that forced preschoolers and their caregivers to stay at home33. This requirement likely increased children’s time spent at home, where there might be greater injury risks compared to locations such as preschools due to insufficient child safety equipment at home and less safe home-playing environments among most rural families34,35. The situation that adult caregivers were also at home with children on a daily basis may also have allowed caregivers to detect minor child domestic injuries (such as indoor falls)27,28,36,37,38, which may be overlooked when they occurred under alternate supervision, such as in a preschool environment.

Third, participation in this program concerning child injury prevention may have improved caregivers’ awareness and perception about child health and safety in both groups, which created increased attention to children’s minor injury events during the 12-month follow-up period39, thus collecting more minor child injury events that were previously overlooked by the caregivers.

Despite the elevated unintentional injury incidence rates, our study design allows us to interpret the results meaningfully. The cluster RCT design also allowed us to control for potential contamination within-preschool of participants whose children were attending the same preschool40. Contamination between-preschools was possible but properly addressed to a certain extent. The enrolled preschools we chose were geographically separated with a minimum distance between preschools of at least 3 kilometers. It is less likely that many participants in one group interacted socially from participants in the other group. Also, we organized strict and standardized training for each participating preschool prior to the intervention, ensuring that preschool teachers and staff were masked to the identity of other participating preschools and were instructed not to disclose information about the app interventions. Finally, our research group intentionally used the back-end settings of the app to restrict disseminating any child injury prevention information to caregivers in the control group during the 12-month intervention period. Relevant information was disclosed to them when the trial ended.

The subgroup analyses demonstrated significant reductions in unintentional injury incidence specifically among two vulnerable populations: caregivers with the lowest education level and caregivers who had no experience learning about child injury prevention before the intervention. This suggests the intervention may be particularly effective for these populations with lower baseline safety literacy, who likely had greater room for improvement (a potential ceiling effect)41. They also may be among the most vulnerable populations from an equity perspective. Additionally, we detected effectiveness among frequent users of other parenting apps, a finding that may be attributed to their higher digital literacy prior to the intervention42, enabling proficient utilization and better access to health information with the app intervention. Although smartphone ownership is 80% in China43 and 86% for the world44, however, effective use of health applications can vary. To prevent the technology gap from widening health disparities, future scaling strategies should include modified app usability and user guides, as well as complementary offline support tailored for digitally vulnerable populations.

The cause-specific post-hoc analyses revealed one hard-to-interpret result. Because relevant data were absent, we cannot rigorously separate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. On the other hand, this exploratory result may be underpowered and offer a spurious finding, which needs to be further verified. And future research is strongly recommended to explore the promising use of mHealth technology in health monitoring and alerting45, such as age-specific notifications and developmental risk alerts, further enhancing the flexibility and utility of telehealth services for child unintentional injury prevention.

Our study demonstrates that a well-designed mHealth app intervention can significantly reduce preschooler unintentional injuries in rural China. The app intervention was scalable and could be disseminated broadly and conveniently via mHealth approaches, and therefore holds great potential for integration within multi-factorial interventions to decrease preschooler unintentional injuries in rural China and other areas where child injury prevention resources remain suboptimal5. For instance, this app intervention could be flexibly embedded in the Chinese National Basic Public Health Service Package program, which currently recognizes child unintentional injury prevention as a critical task but has not yet developed the organized or systematic implementation measures.

With the rapid penetration of the wireless internet globally, broad extension of app intervention is feasible according to the practical circumstance. The external support strategy in our study was intentionally designed to be low-intensity and replicable. For broader scalability, the manpower support could be easily and flexibly replaced by electronic instructions, video guides, and/or automated reminders to lower the cost and labor. Moreover, we propose integrating the promising app intervention into existing public service programs, such as school-based health education and national basic public health programs, where it can be supported by concise implementation guides to form a feasible, standardized, and multi-component intervention strategy and establish the cooperation mechanism. Looking forward, future iterations could incorporate AI-generated content (with human oversight) and AI-driven user support to reduce long-term personnel costs and sustain user engagement and retention46. The goal of integration is not to add burden but to empower educators and health workers by providing them with a standardized, empirically-supported, and ready-to-use tool with relevant guides that enhance their existing safety education efforts with evidence-based content, facilitating the delivery of specialized child injury prevention knowledge and skills.

One other aspect of dissemination should be considered: how can results be shared with caregivers and other stakeholders? We suggest three dissemination strategies. First, visual summaries of findings could be distributed to participants in the local language via established channels (e.g., WeChat groups) and community meetings. Second, policy recommendation reports could be submitted to relevant bodies (e.g., Health Commission and Education Bureau), integrating results into existing public services and publicly-available resources. Third, brief, standardized implementation guides, such as operation manuals, short videos, and illustrated instructions, could be provided for community health workers and preschool teachers to support adoption to enable future implementation. Furthermore, with appropriate cultural adaptations, this app intervention could be tailored and expanded to sustainably benefit more disadvantaged and underserved populations worldwide and children with diverse ages who face analogous child injury prevention challenges47.

We acknowledge five study limitations. First, children’s injuries were assessed relied on caregiver’s reports. Although this approach has been validated as a pragmatic alternative when physician-diagnosed records are unavailable48, it is susceptible to recall and social desirability biases. We adopted three measures to mitigate these potential biases, including use of four follow-up surveys and a short recall time period (three months) for each follow-up survey to improve recall accuracy49, using cluster randomization to assign preschools to the intervention and control groups50, and adoption of identical injury data collection strategy in both groups throughout the study. Second, we did not collect valid data about near-misses and prevented injuries, so we could not distinguish their contributions from the overall intervention effectiveness. According to the occurring mechanism of injury event51,52, such risky events likely occurred and future research is recommended to incorporate documentation of these incidents. Third, we did not quantify the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the elevated unintentional injury rates observed following the intervention. Although data were gathered concurrently in both randomized groups, minimizing likely effects, the pandemic context represents an atypical time period for evaluation. Fourth, we incorporated external support strategies and reward strategies to improve the viability of app comprehension, intervention compliance, and follow-up adherence. These strategies may differ somewhat from implementation in the practical settings. Considering the external support strategies are easily replicated via an electronic instruction, an online video, and/or a message reminder according to the realistic circumstances and thus would be less laborious with a scaled intervention, we recommend adopting these support strategies to implement the intervention in real-world public health practices. Fifth, a formal cost-effectiveness analysis (comparing costs to direct and indirect medical expenditures averted) was not performed. Most caregivers were either unwilling to report the actual costs they incurred, viewing it as sensitive and private information, or could not accurately recall the expenses related to their children’s injuries, especially indirect costs. Future research might consider ways to conduct a formal cost-benefit analysis.

In conclusion, the app intervention reduced preschooler unintentional injuries and improved caregiver’s attitudes, supervision behaviors, and home environment surrounding child unintentional injury prevention in rural China. Given its low cost and convenience, the app should be disseminated widely to underserved populations in rural China, where basic child injury prevention resources are currently inadequate. Chinese governmental bodies are the most likely entity to support and promote implementation. Further, the app intervention could be culturally tailored to benefit preschoolers and their families in other resource-limited and underserved locations globally.

Methods

Study design

A single-blind, parallel two-arm, 12-month cluster RCT was conducted in rural areas of Changsha County in Hunan Province and Yang County in Shaanxi Province, China. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University (approval number: XYGW-2020-56) and registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (registration number: ChiCTR2000037606) on August 29, 2020. Participants were recruited from December 2, 2021 to March 6, 2022. This report followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomized trials53.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated based on the following parameters: 12-month unintentional injury incidence rate of 30% among rural preschoolers54, effect size of 0.8055, cluster size of 150 children per preschool, intra-cluster correlation coefficient of 0.00556, and attrition rate of 15% over the 12-month follow-up. A minimum sample size of 3508 caregivers from 24 preschools (12 preschools per arm) was needed to achieve statistical power of 80% at the 0.05 significance level.

Participant recruitment

Study participants, all rural caregivers of preschoolers, were recruited through the preschools. To increase recruitment efficiency, the study limited eligible preschools to those having 150 students or more; our preliminary survey indicated that most rural preschools in both study counties met this criterion.

Eligible participants who met the following criteria were enrolled at each participating preschool: (1) preschooler and primary caregiver were local residents who had lived in the area for at least the past 12 months; (2) caregiver owned a smartphone and could operate apps independently; (3) caregiver signed informed consent to participate. Exclusion criteria included: (1) caregiver unable to read learning materials and text messages in Chinese without assistance; (2) family planned to move to another city during the subsequent 12 months.

Preschool teachers and staff in each enrolled preschool received standard training from the research team to coordinate recruitment and guided caregivers to download, register and login to the app. Specifically, they informed eligible caregivers basic information about the study (e.g., background, purpose, benefits and requests for participation) via multiple existing preschool-family communication channels such as WeChat and QQ (two popular social media software programs in China), printed brief descriptors of study materials, and orally notified children and their caregivers about the study. Eligible caregivers were provided with an invitation letter that described the benefits and responsibilities for participating in this study, as well as instructions about downloading and using the app. When needed, preschool teachers and staff helped to answer caregiver’s queries and offered assistance to enroll. No incentives were provided to caregivers for recruitment, thus reducing sample selection bias.

Upon first login, caregivers were invited to sign the informed consent electronically. Following consent, the baseline survey was completed online. Next, the app automatically sent app usage instructions and tutorial videos to the caregivers for repeatedly retrieving and reading. If caregivers experienced any problems, they could ask for help from preschool teachers or staff.

Randomization and masking

To avoid contamination between caregivers of preschoolers attending the same preschool, we randomized at the preschool level40. A total of 12 participating preschools from Changsha County and 12 from Yang County were allocated randomly to either the intervention group or the control group in a 1:1 ratio, with randomization determined by an independent, masked researcher using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute). Group allocation was concealed during data analysis.

Control group

Caregivers in the control group received an educational program via the app that taught parenting knowledge and skills concerning pediatric disease risks, childhood nutrition, childhood development, and child daily health care. It excluded any explicit child injury prevention knowledge and skills.

Intervention group

Caregivers in the intervention group received all education materials delivered to those in the control group using the same app, and were additionally exposed to educational components about child unintentional injury prevention (Fig. 4). Injury prevention training covered all major child injury causes in rural China, including road traffic injuries, falls, drowning, burning, scalding, poisoning, suffocation, electric burns, and injuries caused by animate or inanimate mechanical forces. The training was designed based on injury prevention and health behavior theories, including the Haddon Matrix, the TPB, and the Framework for the Rational Analysis of Mobile Education18.

A precursor version of the app was initially created for caregivers of urban preschoolers based on relevant theories and published development framework18. It consisted of four active modules: (1) content learning, including a series of educational materials to impart basic and practical knowledge and skills; (2) social interaction, comprising an online forum, online expert consultation, and locations for users to leave comments; (3) survey and feedback, used for online surveys, collection of user’s suggestions, and for experts to reply to users’ queries; and (4) customization, allowing users to customize the color scheme of their app and display their personal learning progress18. To meet the characteristics and needs of rural Chinese caregivers and their preschool-aged children (e.g., low levels of formal education; more grandparent caregivers than in urban areas; injury risks involved in raising children in rural areas) and overcome deficiencies of a previously-reported randomized trial among urban caregivers16,17, we modified the precursor version of the app to: (1) include major injury causes for preschoolers living in rural environments; (2) introduce more suitable education materials, such as audio recordings (30% vs. 0% in the current vs. precursor app version), interactive games (20% vs. 3%), cartoons (10% vs. 5%), and videos (10% vs. 6%), and also retain short essays with pictures (30% vs. 86%); (3) increase the frequency of releasing new educational material to seven times weekly; (4) limit the time required to learn each lesson to about three minutes; and (5) develop a concise app usage instruction document and an easy-to-understand online tutorial video.

In addition, we improved the previous user interface and functions to cater to user’s preferences and app usage habits. To enhance intervention compliance, we provided participants with small incentives after initiating the app intervention, which included redeeming reward points for phone credit or mobile data top-ups, gaining entries into a lottery, and offering monthly gifts for the top 30 active learners in each preschool. Last, we adopted external support strategies whereby local office staff from a charitable non-governmental organization and preschool teachers and staff at each participating school to assist caregivers with app usage and completion of surveys when required. Details of reward strategies and external support strategies appear in Supplementary Note 1.

Prior to the formal study, a one-week pilot test was performed with 42 rural caregivers of preschoolers who were not included in the final study. Usage experience, impressions and suggestions about the app’s content, functions, interface, usability, readability, and operability were collected. This information was used to refine the app prior to the formal study.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was unintentional injury incidence rate among preschoolers over a 12-month period. Following previous research16, an injury event was defined as meeting any of three criteria: (1) child received a medical diagnosis or treatment by a doctor or other medical professional following an injury; (2) child took any injury-related medication or received first aid, massage, or cold/hot compress by a non-medical individual (e.g., family member, preschool teacher, preschool staff member) following an injury; or (3) child was restricted from school or other activities, or was forced to stay in bed or rest for a half-day or longer following an injury.

Unintentional injury incidence rate was calculated as “number of preschoolers newly experiencing at least one injury during the 12-month period divided by total number of preschoolers × 100%”.

Secondary outcomes

-

(1)

Caregiver attitudes concerning the preventability of, self-efficacy for, and necessity of child unintentional injury prevention, measured via a three-item instrument16,57, with each item scored on a five-point scale (possible range three to fifteen), with higher scores representing better awareness of preventability, self-efficacy, and necessity for child injury prevention.

-

(2)

Caregiver supervision behaviors, assessed via a 22-item instrument16,57,58, with each item scored on a four-point scale (possible range from 22 to 88 points), with higher scores reflecting safer supervision.

-

(3)

Self-reported safety of the home environment, assessed via a 16-item instrument16,57,59, with each item scored on a five-point scale (possible range from 16 to 80), with higher scores reflecting safer home environment.

All three scales were previously reported to have good reliability and validity16,57,58,59.

Covariates

Socio-demographic variables concerning preschoolers (sex, age) and their caregivers (sex, age, relationship to child, level of education, household size, frequency of using other parenting apps, history of child injury prevention education), intervention engagement (number of app logins, overall app-using time), and baseline values of outcome variables (child injury history, caregiver’s attitudes, supervision behaviors, home environment) were included as covariates.

Data collection

Because no official government or hospital system routinely collects injury data for preschoolers in rural China, we followed strategies used in previous studies14,15,16 to retrospectively collect outcome data through four follow-up assessments conducted at the third, sixth, ninth, and twelfth months of the follow-up period. Frequent assessment was conducted to minimize recall bias for minor or moderate injuries. All quarterly assessments were provided to caregivers through both an app-based online survey system and an identical paper-based version, and caregivers completed the survey using the medium they preferred. Preschool teachers and staff assisted with data collection efforts by explaining the importance of follow-up surveys, reminding caregivers to complete the surveys, and checking for survey completeness. Injury incidence during the 12 months prior to the intervention initiation was assessed at baseline survey through caregiver self-report. We chose not to provide incentives to caregivers for reporting injury events during follow-up surveys, thus reducing injury information bias. Intervention engagement data were recorded automatically through an embedded tracking strategy and stored in the backend database.

Four follow-up surveys were conducted between March 2022 and March 2023, a period when strict COVID-19 pandemic control policies were still implemented intermittently in China, because the COVID-19 outbreaks occurred sporadically at that time. These restriction policies likely led to children and their caregivers spending more time at home and less time outdoors.

Statistical analysis

A modified intention-to-treat approach was employed for principal data analysis based on the full analysis set of participants who completed the follow-up. Descriptive statistics were calculated for socio-demographic variables and for primary and secondary outcomes. To handle model convergence problems for binary outcomes, generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) selecting the Poisson distribution within log link function60,61 and LMM performed by the glmmTMB package and the lme4 package, respectively, were used to assess the effectiveness of the app intervention for primary and secondary outcomes, adjusting for socio-demographic variables, engagement variables, and outcome variable baseline values and considering preschool as a random intercept effect. The intra-cluster correlation coefficient at the preschool level was reported. To address overdispersion, hierarchical data, and non-normality of residuals62, we used bootstrapped robust standard errors with 1000 replications to calculate adjusted risk ratio (aRR) and partial regression coefficient (b) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Specifically, 1000 replicate datasets were generated through random sampling with replacement from the original sample data. The distribution of the estimated sample statistic was constituted based on the replicate datasets, not relying on assumptions concerning the original sampling distribution of the standard errors62. Multiple imputation was performed to generate a total of five imputed datasets to impute missing values based on data from participants with complete values of involved variables, which used the predictive mean matching method to retain the natural variability in the data while avoiding implausible imputations63. Subgroup analyses were conducted to assess the intervention effectiveness on unintentional injury incidence rates across socio-demographic variables. Exploratory post-hoc analyses were conducted to examine the effectiveness of the intervention on unintentional injury incidence rates of two specific leading causes of injury, falls and blunt force injuries. Due to inadequate injury events, post-hoc analyses were not performed for other injury causes. Using the same analysis strategy, we conducted per-protocol sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of the intervention effectiveness. Included participants were those who logged into the app at least seven times and used the app for a total of at least 1260 s.

Core codes of the statistical methods are provided in Supplementary Note 2. Randomization was performed using SAS 9.4 software and statistical analyses were performed using R 4.3.2 software. Group allocation remained concealed throughout data analysis by using the blinded codes until all analyses were completed. All statistical tests were two-sided at the 0.05 statistical significance level.

Data availability

Deidentified data used in this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors via email, Peishan Ning (email: ningpeishan@csu.edu.cn) and Guoqing Hu (email: huguoqing009@gmail.com), after publication of the study. Specific data requests will require submission of a proposal with valuable research questions, as assessed by the study steering committee, and might require a signed data access agreement.

Code availability

The core codes of the statistical methods are provided in Supplementary Note 2. The complete codes are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors via email, Peishan Ning (email: ningpeishan@csu.edu.cn) and Guoqing Hu (email: huguoqing009@gmail.com).

References

World Health Organization, United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. World report on child injury prevention. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241563574/ (2008).

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington. GBD 2021 results. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (2025).

National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WISQARS Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. https://wisqars.cdc.gov/ (2025).

Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. In Chinese Cause of Death Surveillance Dataset 2021 (Science and technology of China press, 2022).

Hu, G., Baker, T. D., Li, G. & Baker, S. P. Injury control: an opportunity for China. Inj. Prev. 14, 129–130 (2008).

Li, L. & Yang, J. Injury prevention in China: government-supported initiatives on the leading causes of injury-related deaths. Am. J. Public Health 109, 557–558 (2019).

Free, C. et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technologies to improve health care service delivery processes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 10, e1001363 (2013).

Dixon, C. A. et al. A randomized controlled field trial of iBsafe-a novel child safety game app. Mhealth 5, 3 (2019).

Yan, S. et al. Assessing an app-based child restraint system use intervention in China: an RCT. Am. J. Prev. Med. 59, e141–e147 (2020).

Burgess, J., Watt, K., Kimble, R. M. & Cameron, C. M. Combining technology and research to prevent scald injuries (the Cool Runnings intervention): randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 20, e10361 (2018).

Choi, Y. & Ahn, H. Y. Developing and evaluating a mobile-based parental education program for preventing unintentional injuries in early childhood: a randomized controlled trial. Asian Nurs. Res. 15, 329–336 (2021).

Park, I. T., Oh, W. O., Jang, G. C. & Han, J. Effectiveness of mHealth-Safe Kids Hospital for the prevention of hospitalized children safety incidents: a randomized controlled trial. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 53, 623–633 (2021).

McKenzie, L. B. et al. Efficacy of a mobile technology-based intervention for increasing parents’ safety knowledge and actions: a randomized controlled trial. Inj. Epidemiol. 8, 56 (2021).

Gielen, A. C. et al. Results of an RCT in two pediatric emergency departments to evaluate the efficacy of an m-Health educational app on car seat use. Am. J. Prev. Med. 54, 746–755 (2018).

Wong, R. S. et al. Effect of a mobile game-based intervention to enhance child safety: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e51908 (2024).

Ning, P. et al. An app-based intervention for caregivers to prevent unintentional injury among preschoolers: cluster randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 7, e13519 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Factors associated with dropout of participants in an app-based child injury prevention study: secondary data analysis of a cluster randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e21636 (2021).

Ning, P. et al. Needs analysis for a parenting app to prevent unintentional injury in newborn babies and toddlers: focus group and survey study among Chinese caregivers. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 7, e11957 (2019).

He, J. et al. Assessing the effectiveness of an app-based child unintentional injury prevention intervention for caregivers of rural Chinese preschoolers: protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 21, 2137 (2021).

Doll, L. S., Bonzo, S. E., Sleet, D. A., Mercy, J. A. & Haas, E. N. Handbook of Injury and Violence Prevention (Springer, 2007).

Peng, Y., Wu, F., Yang, J. & Li, L. Child safety seat‒use behavior among parents of newborns: a trans-theoretical model‒guided intervention in Shantou, China, 2021. Am. J. Public Health 113, 1271–1275 (2023).

Vaart, R. V. D. et al. Blending online therapy into regular face-to-face therapy for depression: content, ratio and preconditions according to patients and therapists using a Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry 14, 355 (2014).

Office of the Leading Group of the State Council for the Seventh National Population Census. China Population Census Yearbook 2020 (China Statistics Press, 2022).

Li, S. et al. Epidemiologic features of child unintentional injury in rural Pucheng, China. J. Inj. Violence Res. 5, 89–94 (2013).

Liu, L. et al. Research on unintentional injuries and its affecting factors in preschool children at urban area of Guiyang City. China J. Child Health Care 9, 91–93 (2001).

Chen, G., Smith, G. A., Deng, S., Hostetler, S. G. & Xiang, H. Nonfatal injuries among middle-school and high-school students in Guangxi, China. Am. J. Public Health 95, 1989–1995 (2005).

Papachristou, E. et al. Is it safe to stay at home? Parents’ perceptions of child home injuries during the COVID-19 lockdown. Healthcare 10, 2056 (2022).

Côté-Corriveau, G. et al. Hospitalization for child maltreatment and other types of injury during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abus. Negl. 140, 106186 (2023).

Flynn-O’Brien, K. T. et al. Pediatric injury trends and relationships with social vulnerability during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-institutional analysis. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 94, 133–140 (2023).

Landen, D. D. & Hendricks, S. Effect of recall on reporting of at-work injuries. Public Health Rep. 110, 350–354 (1995).

Mock, C., Acheampong, F., Adjei, S. & Koepsell, T. The effect of recall on estimation of incidence rates for injury in Ghana. Int J. Epidemiol. 28, 750–755 (1999).

Warner, M., Schenker, N., Heinen, M. A. & Fingerhut, L. A. The effects of recall on reporting injury and poisoning episodes in the National Health Interview Survey. Inj. Prev. 11, 282–287 (2005).

Ning, P. et al. COVID-19-related rumor content, transmission, and clarification strategies in China: descriptive study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e27339 (2021).

Zhou, X. et al. Unintentional injury deaths among children under five in Hunan Province, China, 2015-2020. Sci. Rep. 13, 5530 (2023).

Shen, M. et al. Non-fatal injury rates among the “left-behind children” of rural China. Inj. Prev. 15, 244–247 (2009).

Tsang, J. T., Fung, A. C., Wong, H. H., Dai, W. C. & Wong, K. K. Epidemiological changes in the pattern of children’s traumatic injuries at Hong Kong emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective, single-institutional, serial and comparative study. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 40, 192 (2024).

Bressan, S., Gallo, E., Tirelli, F., Gregori, D. & Da Dalt, L. Lockdown: more domestic accidents than COVID-19 in children. Arch. Dis. Child 106, e3 (2021).

Palmer, C. S. & Teague, W. J. Childhood injury and injury prevention during COVID-19 lockdown - stay home, stay safe?. Injury 52, 1105–1107 (2021).

Kendrick, D. et al. Parenting interventions for the prevention of unintentional injuries in childhood. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, CD006020 (2013).

Turner, E. L., Li, F., Gallis, J. A., Prague, M. & Murray, D. M. Review of recent methodological developments in group-randomized trials: part 1-design. Am. J. Public Health 107, 907–915 (2017).

Saarinen, A. et al. Randomized controlled trials reporting patient-reported outcomes with no significant differences between study groups are potentially susceptible to unjustified conclusions-a systematic review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 169, 111308 (2024).

Kim, K., Shin, S., Kim, S. & Lee, E. The relation between eHealth literacy and health-related behaviors: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med Internet Res. 25, e40778 (2023).

China Internet Network Information Center. The 56th statistical report on China’s Internet development. Beijing: China Internet Network Information Center. https://www.cnnic.cn/NMediaFile/2025/0730/MAIN1753846666507QEK67ZS9DH.pdf (2025).

Klapper, L., Singer, D., Starita, L. & Norris, A. The global findex database 2025: connectivity and financial inclusion in the digital economy. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex (2025).

Steinhubl, S. R., Muse, E. D. & Topol, E. J. The emerging field of mobile health. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 283rv3 (2015).

Lu, X. et al. Artificial intelligence for optimizing recruitment and retention in clinical trials: a scoping review. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 31, 2749–2759 (2024).

Hofman, K., Primack, A., Keusch, G. & Hrynkow, S. Addressing the growing burden of trauma and injury in low- and middle-income countries. Am. J. Public Health 95, 13–17 (2005).

Pless, C. E. & Pless, I. B. How well they remember. The accuracy of parent reports. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 149, 553–558 (1995).

Harel, Y. et al. The effects of recall on estimating annual nonfatal injury rates for children and adolescents. Am. J. Public Health 84, 599–605 (1994).

Schulz, K. F. & Grimes, D. A. Case-control studies: research in reverse. Lancet 359, 431–434 (2002).

Kim, H., Kriebel, D., Quinn, M. M. & Davis, L. The Snowman: a model of injuries and near-misses for the prevention of sharps injuries. Am. J. Ind. Med. 53, 1119–1127 (2010).

Macaluso, M., Summerville, L. A., Tabangin, M. E. & Daraiseh, N. M. Enhancing the detection of injuries and near-misses among patient care staff in a large pediatric hospital. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 44, 377–384 (2018).

CONSORT Group. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 345, e5661 (2012).

Hu, Y., Yu, X. & Liao, Z. Incidence rate of unintentional-injury among leftover children in rural China: a meta-analysis. Mod. Prev. Med. 42, 4240–4243 (2015).

Li, L., Wang, G., Zhao, D. & Qu, J. Effectiveness evaluation for preschool children with health education to reduce unintentional injuries. Chin. J. Child Heath Care 19, 1056–1058 (2011).

Coupland, C. & DiGuiseppi, C. The design and use of cluster randomised controlled trials in evaluating injury prevention interventions: part 2. design effect, sample size calculations and methods for analysis. Inj. Prev. 16, 132–136 (2010).

King, W. J. et al. The effectiveness of a home visit to prevent childhood injury. Pediatrics 108, 382–388 (2001).

Mason, M., Christoffel, K. K. & Sinacore, J. Reliability and validity of the injury prevention project home safety survey. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 161, 759–765 (2007).

Odendaal, W., Niekerk, A. V., Jordaan, E. & Seedat, M. The impact of a home visitation programme on household hazards associated with unintentional childhood injuries: a randomised controlled trial. Accid. Anal. Prev. 41, 183–190 (2009).

Turner, E. L., Prague, M., Gallis, J. A., Li, F. & Murray, D. M. Review of recent methodological developments in group-randomized trials: part 2-analysis. Am. J. Public Health 107, 1078–1086 (2017).

Naimi, A. I. & Whitcomb, B. W. Estimating risk ratios and risk differences using regression. Am. J. Epidemiol. 189, 508–510 (2020).

Chernick, M. R. Bootstrap Methods: a Practitioner’s Guide (Wiley, 1999).

Morris, T. P., White, I. R. & Royston, P. Tuning multiple imputation by predictive mean matching and local residual draws. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 14, 75 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank the great support of the local government departments and the charitable non-governmental organization “World Vision” for coordinating participating preschools and preschooler caregivers to complete this study. This study received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H., P.N., and G.H. conceived and designed the study. J.H., M.Z., J.L., Y.F., W.W., W.L., H.H., S.Z., and R.P. assisted in the development of education materials, the delivery of intervention, and the implementation of trial. J.H. and M.Z. collected and analyzed the data. P.N. rechecked the data analysis. J.H. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. J.H., P.N., and G.H. mainly interpreted the findings. J.H., D.C.S., P.N., and G.H. critically revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final submitted version for publication. All authors also had unrestricted access to all aspects of the study data and took final responsibility for the manuscript. P.N. and G.H. supervised the study, verified the data, and gave administrative and material support.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, J., Zhao, M., Li, J. et al. App-based prevention of preschooler unintentional injury in rural China: a cluster randomized controlled trial. npj Digit. Med. 8, 760 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02134-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02134-8