Abstract

This randomised controlled trial compared a 10-session chatbot intervention with 5 weekly brief support calls (STARS) to enhanced usual care (EUC) in distressed young adults in Jordan (N = 344). Primary outcome was change in anxiety and depression severity assessed at baseline by the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL), 1-week posttreatment, and 3 months after treatment (primary outcome timepoint), as well as secondary outcome measures of psychological distress, personally identified problems, functional impairment, wellbeing and perceived agency. At the 3-month assessment, relative to EUC participants enrolled in STARS reported greater reductions of anxiety (effect size, 0.70) and depression (size, 0.61), as well as greater reductions in psychological distress, personally identified problems, functional impairment and greater improvement in wellbeing and sense of agency. Similar levels of efficacy were retained even for those with more severe symptom levels. This guided chatbot offers a scalable psychological intervention that can be implemented to increase access to evidence-based mental health care. Trial Registration: The trial was prospectively registered on ISRCTN on 02/11/2022 (https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN19217696).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The estimated global prevalence of anxiety and depression in young people aged 20–24 years is 4.7% and 4.0%, respectively1. This represents a significant public health issue because half of all people with a mental disorder develop these conditions by the age of 20 years2. Most youth live in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs), where the majority of young people cannot access mental health care3. It is estimated that only 3% of people in LMICs with mental health needs receive minimal adequate care4. This treatment gap occurs because there are inadequate mental health budgets, insufficient mental health services, and too few mental health specialists5. Many young people also avoid mainstream mental health care because of concerns of stigma and discrimination perceived with mental health conditions6.

Digital interventions offer one potential solution to addressing the treatment gap in youth in LMICs where an increasing number of people have access to the internet. Whereas evidence indicates that digital programmes can reduce anxiety and depression in high-income settings7, evidence for the effectiveness of digital interventions in LMICs is less developed8. A stark limitation of current digital mental health interventions is that they often have high drop-out rates, which has been attributed in part to a lack of interaction with the user9. To overcome this problem of poor engagement, digital interventions have been developed using conversational agents that attempt to more closely simulate the interaction with a person, using either pre-programmed decision tree logic or, more recently, artificial intelligence. These ‘chatbots’ have been shown to be effective in reducing anxiety and depression10. However, generative AI chatbots are still a nascent technology and may also present a number of risks or potential issues, including improper or inaccurate responses11. Rule-based or decision tree chatbots can address these concerns, as they are pre-programmed to provide the same content to all users.

To improve access to evidence-based mental health care for young people in LMICs, the World Health Organisation has developed the Sustainable Technology for Adolescents and Youth to Reduce Stress (STARS) intervention, which comprises a rule-based chatbot designed to reduce psychological distress12. This intervention was developed following substantial human-centred design in five LMICs and territories, and resulted in an intervention based on a chatbot with whom the user interacts with and learns stress coping strategies. The chatbot includes multi-media content (e.g. videos), as well as storylines or ‘personas’ where the user interacts with fictional characters experiencing difficult life events. Because of some of the concerns related to generative AI and to ensure all users receive the same content, it was built using decision-tree logic while allowing for a degree of personalisation and choice in the user journey12. This trial represents the first controlled evaluation of the STARS intervention by testing its capacity to reduce anxiety and depression in psychologically distressed young adults in Jordan, when delivered with brief weekly support from trained non-specialist helpers (called e-helpers). This site was selected to conduct this initial evaluation of STARS because Jordan is a LMIC that has been challenged over the past decade by a huge influx of refugees since the Syrian war, economic difficulties, and marked psychological adversity as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Survey data indicate that more than half of young adults in Jordan experienced psychological distress since the COVID-19 pandemic13. We hypothesised that young adults in the STARS condition would have greater reductions in anxiety and depression, as measured by the Hopkins Symptom Checklist, than those in enhanced usual care (EUC).

Results

There were minimal missing values at baseline, and they were replaced using a single imputation; the listwise proportion of missing values at post and follow-up ranged from 51.2–55.8%; and across post and follow-up, the percentage of missing data was 36.6–43.3% (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Participant Characteristics

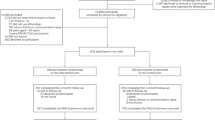

Between July 2023 and January 2024 (with final follow-up assessments completed in June 2024), 344 participants were enrolled into the study. Participants were randomised to either STARS (n = 171) or EUC (n = 173). Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Fig. 1 summarises the participant flow. Most participants completed the posttreatment (221, 64.2%) and 3-month assessment (220, 64.0%). Participants who were and were not retained at 3 months differed in terms of those who were retained were more likely to be non-Jordanian, married, or have basic education (see Supplementary Table S3). The mean number of STARS lessons attended was 7.4 ± 3.8, with 66.7% participants completing at least seven lessons. The mean number of e-helper sessions attended was 3.6 ± 1.8, with 105 (61.4%) participants attending at least four sessions. Forty-six e-helper calls were recorded and rated for fidelity; 89% of the call content was carried out adequately.

Primary outcome

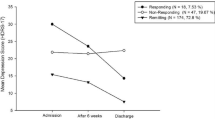

Table 2 shows the results based on MI for each outcome. The number of MI datasets per outcome ranged from 58 to 104 (Supplementary Table S1). For each outcome, we report the change from baseline within conditions, and the difference between conditions in that change. Relative to EUC, at the 3-month assessment, participants in STARS reported a greater reduction in HSCL total scores (mean difference 10.21 [95% CI, 6.04–14.39], P < 0.001), with a moderate effect size (0.68 [95% CI, 0.40–0.96]). Those in STARS also reported greater reduction in anxiety (mean difference 4.25 [95% CI, 2.53–5.97], P < 0.001), with a large effect size (0.70 [95% CI, 0.41–0.98]), and greater reduction in depression (mean difference 6.09 [95% CI, 3.16–9.02], P < .001), with a moderate effect size 0.61 [95% CI, 0.31–0.90]. The minimal clinically significant difference (MCID) for HSCL total score indicated that more participants in STARS (68.6%) achieved a good outcome relative to those in EUC (41.6%) (OR = 3.1, 95% CI 1.7–5.6), with a number needed to treat of 2.7 (95% CI 1.9–3.6). The minimal clinically significant difference for anxiety (defined by total scores on the HSCL Anxiety subscale scores) indicated that more participants in STARS (65.9%) achieved a good outcome relative to those in EUC (41.9%) (OR = 2.7, 95% CI 1.6–4.5). More participants in STARS (59.1%) than in EUC (39.8%) achieved a good outcome for depression (defined by HSCL Depression scale score) (OR = 2.2, 95% CI 1.3–3.6). The number needed to treat (NNT) for anxiety was 2.7 (95% CI 1.7–4.6) and for depression was 3.1 (95%CI 1.7–4.6).

Secondary outcomes

Relative to EUC, STARS resulted in greater reductions at the 3-month assessment in scores on the K10 (mean difference 5.33 [95% CI, 3.05–7.60], P = .001; effect size, 0.7 [95% CI, 0.4–0.9]), PSYCHLOPS (mean difference 2.26 [95% CI, 0.84–3.68], P = .002; effect size, 0.5 [95% CI, 0.2–0.8]), and WHODAS (mean difference 6.16 [95% CI, 3.86–8.45], P = .001; effect size, 0.7 [95% CI, 0.4–1.0]). There were also greater increases in STARS participants on scores on the WHO-5 (mean difference −1.69 [95% CI, −3.15 to −0.22], P = 0.02; effect size, −0.4 [95% CI, −0.6 to −0.1]) and SHS (mean difference −2.00 [95% CI, −3.44 to −0.56], P = 0.007; effect size, −0.4 [95% CI, −0.6 to −0.1]).

Secondary analyses

When analyses were limited to those who had both a probable anxiety and depressive disorder, all the significant differences observed in the intent-to-treat analyses were replicated, indicating that STARS was highly efficacious in those with more severe psychological distress (Supplementary Table S4). Similar findings were observed when analyses were restricted to those with observed data (Supplementary Table S5). The series of sensitivity analyses (see Supplementary Figs. S1–S8). embodied assumptions about the course of STARS participants with missing data relative to EUC participants. Three of these—JR, CR and CIR—assume they follow EUC in some way, while LMCF assumes that the STARS participants maintain their status. In each of these scenarios, the size of the change was reduced, however, it remained significant in almost all cases, in particular for the two primary outcomes. Furthermore, the tipping-point analyses showed that for all these scenarios, the size of the additional reduction in change for STARS required to shift to non-significance was non-trivial: at 3-month follow-up, it was at least 3 points for anxiety, and at least 4 points for depression, values close to 0.5× baseline SD indicating robust findings.

In terms of adverse events, two participants in the STARS condition reported prior self-harm attempts at baseline assessment.

Discussion

This trial represents the first large-scale randomised controlled trial of the WHO STARS intervention offered with brief guidance and support from trained non-specialist helpers. Encouragingly, it demonstrates that STARS reduced anxiety, depression, functional impairment and personally identified problems, and improved wellbeing and a sense of agency relative to EUC. Notably, each of these outcomes involved STARS achieving moderate to large effect sizes. These effects were retained even after sensitivity analyses that accounted for attrition. The capability for this chatbot to have clinical effectiveness was underscored by the NNT of 2.7 for anxiety and 3.1 for depression; the NNTs are impressive for STARS in the context of meta-analyses, suggesting that NNTs for anxiety and depressive disorders tend to be between 4 and 514.

A major goal of this study was to improve upon existing digital applications used in LMICs by adopting a chatbot to enhance acceptability and engagement. The observation that the average number of chatbot lessons attended was 7.4 out of 10 underscores the high level of engagement by users. This high level of engagement can be contrasted with another WHO digital intervention that used similar strategies in a large trial in Lebanon, in which participants only completed on average 1.7 out of 5 sessions15. High drop-out rates are a common problem in digital interventions16, and the major rationale for using a conversational agent in the current trial was the capacity of such an intervention to mimic aspects of human interaction, and thereby engage users more effectively. It should be noted that a substantial human-centred design approach occurred in the development of STARS, which included iterative design and prototyping of key elements, which arguably contributed to the intervention being acceptable to participants.

It is noteworthy that moderate to large effect sizes on all primary and secondary outcomes were observed for participants who met criteria for both probable anxiety and depressive disorder at baseline. This is a relevant finding because it indicates that the STARS intervention can assist young adults with probable common mental disorders. Although scalable mental health interventions are often conceptualised as being primarily for general psychological distress or subsyndromal disorders, the current findings show that even those with more severe mental health problems can be assisted with the guided STARS intervention. This is a significant finding because mental health services are limited in LMICs, and so the STARS chatbot offers a significant means to access evidence-based mental health assistance for young adults with anxiety or depressive disorders.

In terms of trial limitations, we note that 62% of participants were retained at the 3-month follow-up. Although this level of attrition does represent a threat to the integrity of the findings, it is common in digital interventions to have significant attrition both during the intervention and at follow-up. We estimated retention of only 50% at follow-up, and exceeded this by retaining 62% of the sample. We recognise that missing data did not occur completely at random because those who were retained were more likely to be of other nationalities, married, and to have a basic education. Accordingly, bias in attrition at follow-up may have influenced the modelled trajectories over time. Nonetheless, we employed very rigorous sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the multiple imputation approach, and each of these tests indicated confidence in our reported findings. Second, we recognise that because this intervention was a behavioural intervention, we could not blind participants from their assigned treatment condition, and so it is possible that expectancy effects impacted the outcomes. Third, the reliance on a 3-month follow-up reflects the impact of the STARS intervention in the medium term, and does not inform us about its longer-term efficacy. In the context of scalable interventions in LMICs potentially not maintaining their initial gains16, it is important for future studies to conduct longer-term follow-up assessments to determine the sustained benefits of STARS. Fourth, we acknowledge that the EUC arm does not represent an active digital intervention nor did it involve human support, and in this sense does not control for non-specific therapeutic factors such as app use or human interaction. Fifth, all outcomes were obtained from self-reports and so may be susceptible to social desirability or recall bias. Finally, this study’s conclusions are based on a 3-month follow-up, and there is a need to evaluate the longer-term sustainable effects of STARS.

In conclusion, STARS offers a highly promising approach to reduce anxiety and depression, as well as improve wellbeing, in young adults in LMICs. In the context of most young adults in LMICs not being able to access efficacious mental health care, this is an important advance because it represents a step towards a scalable intervention that overcomes several barriers to help-seeking to mainstream services that can be provided across a wide geographical area. By providing an intervention that can be accessed confidentially, it overcomes stigma about help-seeking, which is a key issue in Jordan and many other LMICs, where mental health problems are regarded negatively, incur significant social judgement, and can impede motivation to seek help from mainstream services, and also mitigates challenges of delivering services in remote or difficult regions that impede access to mental health services17. STARS also potentially aids scale-up through the use of remote delivery, where helpers can be centralised in one place, potentially overcoming common training and supervision barriers, and by reducing the amount of helper time required from an hour per session, over multiple sessions, as is often required in interventions, to five 15-min telephone calls. We recognise that the broader applicability of this programme requires replication in other cultural and language contexts, age groups, and potentially adaptation to settings with limited smartphone access.

Methods

Trial design

The trial was prospectively registered on ISRCTN on 02/11/2022 (https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN19217696). It was approved by the WHO Ethics Review Committee (ERC.0003729), and the University of Jordan (PF.22.9), and all participants provided informed consent prior to participation. No changes were made to the trial protocol (1). In this randomised, parallel, controlled trial, psychologically distressed young adults in Jordan were randomly assigned to either STARS or EUC on a 1:1 basis. Assessments were conducted via online assessments. The primary outcome was anxiety and depression symptoms, and the primary outcome timepoint was the 3-month assessment.

Participants

Participants were recruited in Jordan via online advertising and publicising the study in universities in Amman. Potential participants were screened via a website (Qualtrics software), and after completing digital informed consent, participants completed the screening measures.

Inclusion criteria included: (a) aged between 18–21 years, (b) residing in Jordan, (c) moderate/high psychological distress as operationalized by scores of ≥20 on the Kessler Distress Scale (K1018), and (d) access to a device for intervention delivery. Exclusion criteria included (a) imminent suicide risk as determined by questions to assess serious thoughts or a plan to end one’s life in the past month19. Eligible participants were contacted by telephone to explain the trial and answer any questions they had. Participants were then provided with a personalised link to complete the online baseline assessment.

Randomisation and masking

Following completion of the baseline assessment, participants were assigned to STARS or EUC by randomisation on a 1:1 ratio via Qualtrics software that stratified randomisation of Jordanian/Palestinian and other nationalities on a 1:1 basis. All assessments were conducted online without the assistance of research personnel, and in this sense, independence of assessments from treatment was assured. E-helpers and participants were not masked for treatment allocation because they were aware of the administered treatment.

Interventions

The STARS intervention, described in more detail elsewhere12, comprises 10 lessons that are intended to be completed over 5 weeks. The structure and length of the STAR programme were developed following considerable human-centred design with young people in five countries, and this was further refined with consultation with young adults in Jordan; this process contributed to the decision to structure the content spread over 10 sessions, as well as the design of the current trial12,20. STARS is a pre-programmed chatbot that uses decision-tree logic to deliver content that guides participants through stress coping strategies via messaging. The delivery mode of STARS utilises a conversational style from the chatbot with opportunities to hear from fictional characters who are portrayed as having different stress-related problems. Pilot adaptation work for this trial indicated that for this age group of urban Jordanians, the appropriate stressful experiences related to university, unemployment and financial difficulties, and romantic and family relationships20. The chatbot was designed to simulate a conversation between the participant and a person, despite initially being informed that the programme is an automated chatbot. The lessons ranged from 10–25 min, and included text, videos, audio clips, and activities to appeal to different preferences in learning styles (e.g. participants could choose to read the stories of different characters). Using a combination of pre-defined choice responses and limited free-text input, participants responded to the conversational text generated by the chatbot. Lesson 1 comprised an orientation to the chatbot and rationale for the intervention. Lesson 2 involved psychoeducation, explained via a character story about common emotional experiences to stressful events, as well as the participant setting their goals regarding the intervention (e.g. stress, relationship, or mood management). Lesson 3 taught controlled breathing as a stress management strategy. In Lesson 4, participants continued practising this technique, and also learnt ‘grounding’ (being aware of all five senses during stress) as an additional strategy. Via the character stories, in lessons 5 and 6, participants learn strategies to cope with stress, including identifying experiences of mastery, pleasure, and/or social connection. Lesson 7 introduced problem management techniques via the character stories, and lessons 8 and 9 explained self-talk as an alternate strategy to appraise situations adaptively. Lesson 10 focuses on relapse prevention and encourages the use of the strategies in planning for the management of future stressors. The STARS chatbot also provided a toolbox of video and audio resources, quizzes and an extra ‘helping’ lesson to support learning the strategies (see Fig. 2).

To support participants using the chatbot, non-specialist helpers (called ‘e-helpers’) were trained and supervised in a self-help support model devised by WHO and used previously with similar interventions15. This comprised of five weekly 15-min telephone calls with participants to provide support and motivation in using the chatbot. Participants were asked if they wanted to receive reminders prior to each scheduled call, and if appropriate, received prior reminders by text or phone call. If participants did not attend the phone call, they received two reminders to reschedule their next call. The e-helpers had at least a Bachelor’s degree but no formal mental health training. Training comprised of five days and covered an introduction to common mental health conditions, basic helping skills, structured call protocols to follow when providing support, an introduction to and practise with, the STARS intervention, and management of adverse events and referral pathways. E-helpers received weekly group supervision from a qualified clinical psychologist.

To assess treatment fidelity of support offered by e-helpers, a random sample of 5% of all planned e-helper sessions were audio-recorded, and were rated by the project manager using a checklist from the e-helper manual. The checklist included all the steps for e-helpers to deliver during each call (e.g. introducing e-helper support in the welcome call, reviewing practice of lessons in calls 2 to 4, reviewing action plan for relapse prevention in the final call). Adverse reactions were monitored and recorded by the e-helpers.

Participants in EUC accessed a website that contained information derived from lesson 2 of STARS, which comprised psychoeducation about anxiety and depression, a story about a fictional character who talks about their emotions, and a link to a list of psychosocial services in Jordan where participants could access mental health care. Provision of psychoeducation and explicit referral to psychological services is enhanced relative to usual care in Jordan because these services are not routinely offered. This list was also contained in the toolbox section of the STARS intervention.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was change in anxiety and depression severity, as measured by the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL21) total scores. The HSCL consists of 25 questions, with 10 questions related to anxiety (range, 10–40) and 15 questions related to depression (range, 15–60), with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety and depression, respectively. The HSCL has been validated across many cultures, including in Arabic contexts22. To determine probable caseness of anxiety and depression, an item mean score is calculated for each subscale, and on the Arabic version of the HSCL relative to structured clinical interview the cutoffs are 2.0 and 2.1, respectively22. The internal consistency of the HSCL in the current sample was robust for the anxiety (0.81) and depression (0.85) scales, respectively.

In terms of secondary outcomes, anxiety and depressive symptoms were assessed using the subscales of the HSCL. Psychological distress was assessed with the K1018, which is a 10-item self-report measure of psychological distress (range, 10-50; higher scores indicate more severe distress). Functional impairment was assessed with WHODAS 2.023, which is a 12-item self-report measure of disability in the past 30 days (range, 0–48; higher scores indicate more severe impairment). Personally identified problems were assessed with the Psychological Outcome Profiles (PSYCHLOPS24), which address personally identified problems, functioning, and wellbeing, with their impact being scored on a 6-point scale (range, 0–20; higher scores indicate more severe problems). Psychological wellbeing was assessed with the WHO-5, which is a 5-item scale of positive wellbeing (range, 0–25; higher scores indicate better wellbeing)25. A sense of agency was assessed with the agency subscale of the State Hope Scale, which is a 3-item scale (range, 3–24; higher scores indicate a greater sense of agency)26.

Statistical analyses

On the basis of previous trials in LMICs with digital interventions21, we projected that to achieve a between-condition effect size of 0.5 at the 3-month follow-up, 172 participants would be required, with 90% power and α = 0.5. Based on meta-analysis of drop-out rates in mental health digital application trials27, we estimated that 50% of the sample would not be retained at follow-up, thereby requiring enrolment of 344 participants to achieve the desired sample size.

Descriptive and other basic statistics were calculated using SPSS (Version 29). Analyses focused on intent-to-treat analyses. Across outcomes, mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) models were fitted using the R package mmrm28. The model included condition, time, and the condition × time interaction, with an unstructured covariance matrix, and Satterthwaite degrees of freedom. The R package emmeans29 was used to calculate contrasts comparing the difference between the conditions in the change from baseline to post, and baseline to follow-up, as well as the associated Cohen-like effect sizes (ES); we interpreted effect sizes as 0.2–0.4 as small, 0.5–0.07 as moderate, and >0.08 as large. Sensitivity analyses used the R package rbmi30.

The MMRM model fitted to available data provides valid inference if missing data is missing at random (MAR), however if some data is missing not at random (MNAR) or if there is a large proportion of missing data then potentially this validity is reduced. Multiple imputation (MI) can increase validity and enable sensitivity analyses. We report MI-based analyses for both the primary and sensitivity analyses. The MI for primary analyses used the R package mice, with the number of imputations chosen using a previously demonstrated approach31. For the sensitivity analyses, package-defined methods of MI were used. To help validate our results the robustness of the MI estimates was tested by a range of sensitivity analyses examining various assumptions for imputation, including tipping-point analyses to determine the worse-case bounds at which the MI-based findings are no longer significant (Supplementary Material p. 19, Tables S6, S7, and S8, pp 27–35).

We additionally examined the effect of the intervention on those who presented with probable anxiety or depression on the HSCL (defined as a mean item score ≥2 on anxiety or ≥2.1 on depression subscales). We also conducted non-planned analyses on the minimally important difference for the primary outcomes by comparing the proportions of participants in each treatment arm showing improvement of more than 0.5 SDs of total HSCL scores from baseline to 3-month follow-up32, and on this basis calculated the NNT.

An independent data monitoring committee reviewed adverse events occurring during the trial. No interim analyses were conducted.

Data availability

Deidentified data can be made available for individual patient data meta-analyses, and after approval of a proposal and signed data access agreement ([r.bryant@unsw.edu.au](mailto:r.bryant@unsw.edu.au)).

References

World Health Organization. World mental health report: transforming mental health for all. (WHO, 2022).

McGrath, J. J. et al. Age of onset and cumulative risk of mental disorders: a cross-national analysis of population surveys from 29 countries. Lancet Psychiatry 10, 668–681 (2023).

Patel, V. et al. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet 392, 1553–1598 (2018).

Moitra, M. et al. The global gap in treatment coverage for major depressive disorder in 84 countries from 2000-2019: a systematic review and Bayesian meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 19, e1003901 (2022).

Bryant, R. A. Scalable interventions for refugees. Glob. Ment. Health 10, e8 (2023).

Renwick, L. et al. Mental health literacy in children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: a mixed studies systematic review and narrative synthesis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 33, 961–985 (2024).

Linardon, J. et al. Current evidence on the efficacy of mental health smartphone apps for symptoms of depression and anxiety. A meta-analysis of 176 randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry 23, 139–149 (2024).

Chakrabarti, S. Digital psychiatry in low-and-middle-income countries: new developments and the way forward. World J. Psychiatry 14, 350–361 (2024).

Välimäki, M., Anttila, K., Anttila, M. & Lahti, M. Web-based interventions supporting adolescents and young people with depressive symptoms: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8, e180 (2017).

Zhong, W., Luo, J. & Zhang, H. The therapeutic effectiveness of artificial intelligence-based chatbots in alleviation of depressive and anxiety symptoms in short-course treatments: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 356, 459–469 (2024).

Malgaroli, M. et al. Large language models for the mental health community: framework for translating code to care. Lancet Digit. Health 7, e282–e285 (2025).

Hall, J. et al. Sustainable Technology for Adolescents and youth to Reduce Stress (STARS): a WHO transdiagnostic chatbot for distressed youth. World Psychiatry 21, 156–157 (2022).

Abuhamdah, S. M. A., Naser, A. Y., Abdelwahab, G. M. & AlQatawneh, A. The prevalence of mental distress and social support among university students in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 11622 (2021).

Cuijpers, P. et al. Absolute and relative outcomes of psychotherapies for eight mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 23, 267–275 (2024).

Cuijpers, P. et al. Guided digital health intervention for depression in Lebanon: randomised trial. Evid. Based Ment. Health 25, e34–e40 (2022).

Bryant, R. A. et al. Twelve-month follow-up of a randomised clinical trial of a brief group psychological intervention for common mental disorders in Syrian refugees in Jordan. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 31, e81 (2022).

Woodward, A. et al. Health system responsiveness to the mental health needs of Syrian refugees: mixed-methods rapid appraisals in eight host countries in Europe and the Middle East. Open Res. Eur. 3, 14 (2023).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 32, 959–976 (2002).

World Health Organization. Psychological interventions implementation manual: integrating evidence-based psychological interventions into existing services (World Health Organization, 2024).

Keyan, K. et al. The development of a World Health Organization transdiagnostic chatbot intervention for distressed adolescents and young adults. Front Digit Health. 7, 1528580 (2025).

Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., Rickels, K., Uhlenhuth, E. H. & Covi, L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav. Sci. 19, 1–15 (1974).

Mahfoud, Z. et al. The Arabic Validation of the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-25 against MINI in a Disadvantaged Suburb of Beirut, Lebanon. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Assess. 13, 17–33 (2013).

Ustun, T. B., Kostanjesek, N., Chatterji, S., Rehm, J. & World Health Organization. Measuring health and disability. Manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) (World Health Organization, 2010).

Ashworth, M. et al. A client-centred psychometric instrument: the development of ‘PSYCHLOPS’ (‘Psychological Outcome Profiles’). Couns. Psychother. Res. 4, 27–33 (2004).

Topp, C. W., Ostergaard, S. D., Sondergaard, S. & Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 84, 167–176 (2015).

Snyder, C. R. et al. Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 70, 321–335 (1996).

Torous, J., Lipschitz, J., Ng, M. & Firth, J. Dropout rates in clinical trials of smartphone apps for depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 263, 413–419 (2020).

Sabanes Bove, D. et al. mmrm: mixed models for repeated measures (R package version 0.3.14.9001, https://openpharma.github.io/mmrm (2024).

Lenth, R. V. emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means (R package version 1.10.5, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans) (2024).

Gower-Page, C., Noci, A. & Wolbers, M. rbmi: A R package for standard and reference-based multiple imputation methods. J. Open Source Software 7, 4251 (2022).

Nassiri, V., Molenberghs, G., Verbeke, G. & Barbosa-Breda, J. Iterative multiple imputation: a framework to determine the number of imputed datasets. Am. Stat. 74, 125–136 (2020).

Norman, G. R., Sloan, J. A. & Wyrwich, K. W. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med. Care 41, 582–592 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by an ELHRA Grant (research study reference #44860). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: Carswell, Bryant, de Graaff, Akhtar, Keyan, Aqel, Abualhaija, Habashneh, Fanatseh, Faroun and Dardas. Data management: Bryant and Habashneh. Analysis and interpretation of data: Bryant and Hadzi-Pavlovic. Drafting of manuscript: Bryant, Carswell, de Graaff, Akhtar, Keyan, Aqel, Abualhaija, Habashneh, Fanatseh, Faroun, Dardas, van Ommeren and Hadzi-Pavlovic. Critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content: Bryant, Carswell, de Graaff, Akhtar, Keyan, Aqel, Abualhaija, Habashneh, Fanatseh, Faroun, Dardas, van Ommeren and Hadzi-Pavlovic. Obtained funding: Carswell and van Ommeren. Study supervision: Carswell, de Graaff, Bryant, Aqel, Abualhaija, Habashneh, Fanatseh and Faroun.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bryant, R.A., de Graaff, A.M., Habashneh, R. et al. A guided chatbot-based psychological intervention for psychologically distressed older adolescents and young adults: a randomised clinical trial in Jordan. npj Digit. Med. 9, 57 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02142-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02142-8