Abstract

Digital pathology images from different hospitals often exhibit variations in color styles due to differences in staining processes, tissue handling, and scanning devices. Integrating data from multiple centers is essential for developing artificial intelligence-driven digital pathology (AIDP) models with improved generalization. However, privacy concerns complicate data sharing, hindering this integration. Here, we propose a self-supervised model, stain lookup table (StainLUT), that leverages the inherent structural similarity between pathology tissue samples of the same disease type across different medical centers and enables stain normalization without the need for cross-center data transfer. Applied to single-center AIDP models, we achieve cross-center tumor localization at the whole-slide level and tumor classification at the patch level, performing comparably to AIDP models trained on centralized or same-center data. StainLUT offers a privacy-preserving solution for stain normalization in unseen medical centers, and holds the potential to facilitate the future deployment of AIDP foundational models under privacy regulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The advent of whole slide scanner technology has facilitated the digitization, representation and archiving of tissue slides as whole slide images (WSIs) in hospital and laboratory settings, resulting in the accumulation of vast repositories of pathology data1,2,3. As a significant branch of medical image analysis, digital pathology (DP) plays a crucial role in cancer diagnosis, treatment planning, and disease research4. The integration of big data generated by DP with advanced artificial intelligence (AI) technologies has given rise to artificial intelligence-driven digital pathology (AIDP) models that exhibit remarkable potential in accurately analyzing tissue samples and identifying pathological abnormalities5,6,7,8,9. It can be asserted that AI-based auxiliary diagnostics are bringing about a revolutionary transformation in pathology. However, this innovation’s flourishing development is accompanied by an urgent question: how to ensure the privacy and security of patient data? It is well-known that the large volume of medical imaging data is the prerequisite for building strong AIDP models. Training data generally needs to be aggregated from multiple medical centers to achieve robust performance. Yet medical data involves patients’ personal information, and sharing data across institutions is strictly governed by legal regulations and ethical guidelines10,11,12,13,14,15. While strategies such as establishing cross-institutional partnerships and data-sharing agreements can be implemented in adherence to these requirements, they necessitate the formulation of stringent data usage and sharing policies. Consequently, even if researchers can access centralized data, ensuring its proper use and protection remains a prolonged process16.

In recent years, federated learning (FL)17 has emerged as a popular research topic for privacy protection in the healthcare domain due to its ability to train models locally without the need for centralized datasets18,19. However, it presents high coordination, management and computational costs across different medical centers20 and fails to transfer to centers not involved in the training robustly. Furthermore, existing studies indicate that FL is susceptible to attacks by malicious participants as an open system, which can significantly degrade the global model’s performance16,21,22,23. A direct and secure solution is to train customized AIDP models within an individual medical institution. This approach eliminates the need for multi-institutional data centralization or sharing, thereby providing more thorough protection of patient data privacy. Additionally, compared to FL, it does not require the establishment of complex cross-institutional data sharing and model collaboration systems, resulting in lower costs and technical barriers. Obviously, this approach first requires that the single medical center has a sufficient number of data samples for model training. Secondly, the trained model is hoped to possess cross-institutional generalization, which is significant for promoting healthcare equity24,25.

In DP, some large medical institutions have accumulated extensive pathological data over the years26,27, which can support model training. Additionally, these institutions can leverage their expertise to provide expert annotations that guide the training process. Histopathological examination is widely recognized as the gold standard for cancer diagnosis. There are general similarities in the histological features of the same tumor type across hospitals and patients. These features, including cell morphology, nuclear morphology and arrangement patterns, are important for diagnosis and analysis by pathologists, as well as key inputs for deep learning28,29. Therefore, it is possible to rely on pathology data from a single large medical center to train AIDP models. Unfortunately, the wide prevalence of staining variations between institutions hinders the scheme’s generalization.

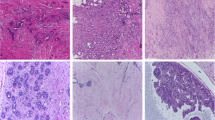

Staining serves as an indispensable procedure for histopathological analysis. Taking the commonly used hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining as an example, variations in sample preparation procedures and using different slide scanners among medical institutions can lead to color appearance discrepancies in WSIs30. As shown in Fig. 1A, there are significant differences in the color style of H&E stained WSIs between the two medical centers26. Many studies have indicated that such variability results in poor model generalization trained on WSIs from a single source23,31,32. The present solutions to tackle this issue mainly revolve around stain augmentation and stain normalization. Stain augmentation involves a series of operations on images during the training process, typically including random RGB transformations such as changes in brightness and contrast, as well as hue perturbations33,34, aiming to simulate histopathological images under different staining conditions in different medical centers. However, such techniques may introduce unrealistic color transformations, rendering them unable to compensate for the differences between training and testing domains effectively. Over the past decade, stain normalization has been widely utilized to mitigate staining variability. This encompasses both traditional methods, such as color deconvolution and stain separation30,35,36,37, and deep learning approaches like style transfer38,39,40,41,42,43. However, while these techniques can attend to predefined staining styles from specific medical centers, they often fail to generalize accurately to unknown institutions. Moreover, due to the necessity of involving images from the testing domain to some extent, these methods fall short of providing the required data privacy protection.

A Differences in sample preparation processes and microscopic imaging equipments can lead to variations in the color appearance of H& E stained WSIs between medical centers, and the sharing of these medical data across institutions can be limited by laws and regulations. B The self-supervised training of proposed StainLUT on pathological images of Center 1, does not require the participation of data from other medical centers and protects patient privacy thoroughly. C Testing of the StainLUT model. Upper panel: StainLUT can map the grayscale images corresponding to images not involved in training back to the target domain well during inference testing. Lower panel: StainLUT can normalize H& E images of a different style from another medical center to the style of the target domain.

Here, we demonstrate a novel self-supervised method, termed stain lookup table (StainLUT), which can theoretically normalize H&E stained pathology images of arbitrary medical centers toward the staining style of a specific medical center, thus eliminating the issue of patient data-privacy security due to the centralization of datasets. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the earliest works based on stain normalization scheme to achieve patient pathology privacy-preserving. Fig. 1B depicts the efficient self-supervised training framework we developed, which consists of two stages: two-step preprocessing and network learning. Through training, StainLUT can efficiently map from the grayscale domain to the target domain (Fig. 1C, upper panel), and then achieve the staining style transformation of other-centered pathology images (Fig. 1C, lower panel). Additionally, a significant breakthrough of StainLUT is that it can not only normalize staining towards a specific style, but also enables adaptive stain normalization based on the scene and content of pathology images. We also demonstrate that StainLUT can be successfully applied to the single-center AIDP model to improve cross-center performance while protecting patient data privacy, which is superior to the commonly adopted stain augmentation method. Moreover, StainLUT plays a role in the inference stage, does not conflict with the stain augmentation employed in the training phase, and thus can be used jointly. This capability presents a promising strategy for scaling AI applications in DP.

Results

StainLUT model development

To improve the cross-center generalization of AIDP models based on single-center data, the proposed stain normalization scheme is required not to violate the privacy protection principle, i.e., the fact that the pathology data of other centers are equally invisible, which constitutes the major problem. The traditional stain normalization methods depend highly on the selected cross-center reference images. Here we proceed directly from the perspective of self-supervised learning. Specifically, StainLUT is designed based on the assumption that the pathological structures or histological features of the same disease type are consistent across medical centers37,44. Therefore, we convert the input RGB pathology image into a public grayscale domain that can effectively characterize these features, presented in a two-step preprocessing (Fig. 1B and Fig. 2, top rows). The initial color randomization (CR) preprocessing is performed to improve the model’s adaptability to pathology images with different background intensities. Immediately following this, we perform grayscaling preprocessing to transform the CR results and complete the self-pairing of input images. Note that the obtained grayscale image is actually an RGB image composed with 3 identical grayscale channels. At this point, the key to our self-supervised scheme becomes how to map the 3-channel grayscale image back to the original color pathology image. This is essentially a transformation problem of RGB color space.

The input images are first preprocessed in two steps: color randomization (CR) and grayscaling. Then they are input to the Predictor and Encoder to obtain the parameter of the perceptual image scene and the context map (CM) of the perceptual image content, respectively. The former is used for weighted fusion of basis stainLUTs to obtain context-aware stainLUT, and the latter is cascaded with the corresponding three-channel grayscale images to obtain four-channel grayscale-context concatenated images. Finally, the four-channel images are fed into the context-aware stainLUT to obtain the output images by quadrilinear interpolation operations. The to-be-output and input images are trained under the guidance of the loss function to obtain the final StainLUT model for inference. More details regarding this scheme execution are provided in the Methods section.

As a fundamental model in digital image processing, the three-dimensional lookup table (3D LUT)45 is effective in achieving precise color value adjustments. Therefore, we innovatively adopt the learnable LUT scheme46,47,48 in the network learning stage. As shown in Fig. 1B, the input single-center WSI patches are used as the ground truth (GT) in the target domain, and the corresponding preprocessed grayscale images are used as the network input. It is well established that, for AIDP models employed in assisted diagnosis, most require dividing the WSI into numerous small patches due to their large size. Although the same-center WSIs usually have a consistent staining style, image patches extracted from different tissue regions may have color differences (Fig. 1B), which means that we need to be able to accomplish adaptive stain normalization based on the image scene. Additionally, there may be structures in pathology image patches that have similar shapes and grayscale values but have differences in color appearance (Fig. S4). Therefore, if the staining of such similar features can be distinguished from each other, more accurate self-supervised mapping can be achieved (Fig. S5).

As an efficient and highly accurate solution to train our self-supervised stain normalization model, the StainLUT framework is created, which combines a scene-aware Predictor network, a content-aware Encoder network and learnable lookup tables (LUTs), as shown in Fig. 2. Here, grayscale-context concatenated images are input into context-aware stainLUT, and output images are obtained through quadrilinear interpolation. The interpolation operation is differentiable, so the learnable parameters in basis stainLUTs can be updated in the end-to-end training process. The detailed definition of stainLUTs fusion and loss function can be found in the Methods section. The specific architecture of Predictor and Encoder can be found in Table S1 and Table S2. For stain normalization inference, only pathology images of the current center and the StainLUT model trained in the target center need to be required, as shown in Fig. 1C, which avoids cross-center transmission of patient data and ensures privacy security.

Stain normalization towards a specific style

Existing stain normalization methods often validate model performance by how well it transforms toward a selected staining style. We first follow this tradition by training the self-supervised StainLUT model on the TNBC dataset49,50. The training set consists the breast cancer pathology images with the same staining style, such as the target image shown in Fig. 3A. The corresponding staining style of the test set is shown in the source image in Fig. 3A.

A Source image and its grayscale image from the test domain and target image and its grayscale image from the training domain. Both express consistent structural information, but they differ in background intensity in the grayscale domain. B Achieve stain normalization from the source to the target image using four accepted methods. C StainLUT is used to implement stain normalization from the source to the target image. WithCR indicates that CR preprocessing is performed during training in the target domain, and NoCR is the opposite. Qualitative and quantitative results show that StainLUT can adapt to intensity differences in the grayscale domain to obtain results closer to the target image when WithCR. D Quantitative comparison of StainLUT and the four recognized methods using violin plot. E Visualize the color features of the source and target domain images using UMAP. The clustering effect (upper panel) exists in the data of the two coloring styles before the implementation of StainLUT, and this phenomenon is effectively eliminated after the implementation (lower panel).

We use the well-established metrics peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and structural similarity (SSIM)51 to evaluate the similarity between staining normalized source images and target images. Fig. 3C and Fig. S1 demonstrate the adaptability of StainLUT to the background intensity of different staining styles qualitatively and quantitatively, which also illustrates the effectiveness of the CR preprocessing strategy in the training framework. Moreover, we extract the color features of the source domain and target domain separately and visualize them by UMAP52, and the result is shown in the upper panel in Fig. 3E. It can be seen that both exhibit a distinct clustering phenomenon, with clear boundaries between clusters. We then apply the StainLUT model to stain normalize the source domain images and perform color feature visualization together with the target domain images again. The lower panel of Fig. 3E demonstrates the clustering effect of the two styles is eliminated, further proving the StainLUT’s effectiveness. Since UMAP visualizes the data structure through relative positions, we have omitted the axis labels, which do not have specific physical significance, to enhance the clarity of the visualization. We also perform comparison experiments with four commonly used stain normalization methods, Macenko53, Khan30, Vahadane37 and StainGAN39. The first three require at least one reference image to be selected in the target domain. The last one is a popular unsupervised learning method that does not require pixel-level image label correspondence for training, but reference images are still required. We perform these methods by pairing each source image with corresponding target image to obtain the respective best stain normalization. Among them, StainGAN’s results are closer to the target images, while the remaining three methods perform poorly (Figs. 3B, S2). This is also revealed in the quantitative results (Fig. 3D), StainGAN shows the best performance except for the proposed StainLUT. We further compare the detailed differences between StainGAN and StainLUT qualitatively (Fig. S3), artifacts and even corrupted tissue structures appear in the former results, but StainLUT does not suffer from these problems. In summary, the self-supervised StainLUT can eliminate the clustering effect between different staining styles. Compared to the four recognized stain normalization methods, it is not inferior in both qualitative and quantitative evaluations. Notably, it does not require the data involvement of other styles during model training (Table S3), which is a unique advantage.

Adaptive cross-center stain normalization

In the context of pathological diagnosis, clinicians rely heavily on their expertise and experience to discern subtle alterations in histological images. Within this framework, staining style extends beyond mere color and visual aesthetics, deeply influencing the pathologist’s sensitivity to, and judgment of, minute variations within the tissue. Here, based on the CAMELYON16 dataset54 with pathology data from two medical centers, we train the StainLUT model in the first medical center (Center 1) to identify the same-center differences between pathology images, and demonstrate its adaptive ability by achieving scene-based and content-based stain normalization in another medical center (Center 2). The source images in Fig. 4A are test images from the training domain, presented in both non-tumor (NT) and tumor (T) categories. Since they are patches extracted from different tissue regions of WSIs, they do not have strict color style uniformity and represent common images in Center 1. We first verify the self-supervised mapping effectiveness of StainLUT in the same center, and can see that it can adaptively output results that are visually highly consistent with the source images (Fig. 4A, bottom row), which lays the foundation for reaching stain normalization of the unknown center from the common grayscale domain. Fig. 4B shows the image patches extracted from WSIs of center 2, where the source image exhibits a significantly different stained appearance from the patches in center 1, but the scene and content of both NT and T images are similar. We input these images into the self-supervised StainLUT model trained in Center 1 and successfully obtained adaptive stain normalization results (Fig. 4B, bottom row). It can be seen that the normalized source image of Center 2 has the same style as the source image of Center 1. To more visually validate the effectiveness of StainLUT cross-center stain normalization, we randomly select 2000 pathology images from two medical centers, including 500 NT and T images from each medical center. Before and after executing the proposed method, we use UMAP to perform color feature visualization analysis, and the results show that the clustering effect between the two centers is eliminated (Fig. 4C). We also achieve WSI-level stain normalization by using the self-supervised model of Center 1 to gradually normalize the patch staining without overlapping on the WSI of Center 2 (Fig. S7A). Thanks to the powerful adaptive capability of StainLUT, the WSI of Center 2 is transformed into the WSI staining style of Center 1 (Fig. S7B), which can enable pathologists to work in a familiar visual environment even when they are in other medical centers. Other stain normalization methods are usually unable to solve this challenge. Although we verify the effectiveness of StainLUT based on the color features of pathological images visualized by UMAP, since there are no pixel-level corresponding pathological images in the two medical centers, it is impossible to perform the quantitative evaluation using full-reference indicators such as PSNR and SSIM as before. Reasonably, we plan to apply it to the auxiliary tasks of the downstream AIDP model for further elaboration.

A The StainLUT model trained in Center 1 infers the test source images in Center 1. B The StainLUT model trained in Center 1 adaptively converts the pathological images in Center 2 to the staining style of Center 1. C The UMAP is used to visualize the pathological color features of the two centers before and after executing StainLUT. Left panel: Tumor (T) and non-tumor (NT) images from the same center have similar color characteristics, with significant differences between centers. Right panel: After StainLUT normalizes the staining style of Center 2 to that of Center 1, their feature distributions become closer together and cannot be distinguished as clearly as before.

Enhancing generalization of single-center AIDP models

Large medical institutions typically adhere to consistent data acquisition standards, equipment configurations, and diagnostic protocols. Single-center AIDP models, trained on in-house resources and expertise, are not required to balance performance across other participating centers, as seen in FL, thus maximizing their utility while safeguarding data privacy. However, this approach often results in poor cross-center generalization. Without requiring any cross-center data involvement during training, we demonstrate that the self-supervised StainLUT can directly enhance the generalization of single-center AIDP models. We first train a single-center classification model based on a convolutional neural network (CNN)55, referred to as Raw CNN, to identify whether extracted patches from Center 1 in CAMELYON16 represent tumor regions. Simultaneously, we train the self-supervised StainLUT using the same data split. We evaluate WSI-level tumor detection from Center 2 in CAMELYON1756 using Raw CNN from Center 1. The predicted probability map illustrates that the model fails to localize any tumor regions (Fig. 5A, third column). Next, we apply the proposed stain normalization model as a preprocessing step to the cross-center classification. The resulting probability map demonstrates a significant improvement in generalization, with the majority of tumor areas correctly localized (Fig. 5A, fifth column). For comparison, we also evaluate HSV augmentation34, a widely recognized approach for enhancing model generalization through random stain perturbations during training. Although this method enables partial localization of tumor regions (Fig. 5A, fourth column), the model’s confidence is notably lower than that achieved with the proposed self-supervised approach. This observation is intuitive: while HSV augmentation applies random stain transformations, StainLUT addresses the color appearance discrepancies between training and testing domains in a targeted manner.

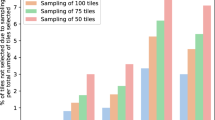

A WSI-level prediction probability maps of single-center pathology models for detecting metastatic cancer tissue across centers. Top row: The first two columns are the original WSI from Center 2 in CAMELYON17 and the corresponding expert-annotated mask. The third column shows the detection result of the raw patches classifier trained in Center 1 of CAMELYON16 using a CNN. The fourth column shows the detection probability map of the patches classifier with HSV augmentation when training. The fifth column shows the result of using the StainLUT trained in Center 1 of CAMELYON16 for real-time preprocessing and then detecting with the patches classifier. The last column shows the detection result with HSV augmentation added when training the patches classifier and StainLUT model stain normalization added when testing. Bottom row: Corresponding WSI of the red-boxed region at the top row. Where the probability maps of model detection and the original WSI image are fused and visualized. B Quantitative results of F1 Score and IoU for different schemes predicting cancerous tissue probability values greater than 0.5. C Quantitative AUC evaluation of different training schemes for binary classification of extracted image patches from WSI. Left: Model training in Center 2 of CAMELYON16 and same-center testing in Center 2 of CAMELYON17. Right: Model training in Center 1 of CAMELYON16 and cross-center testing in Center 2 of CAMELYON17. Experiments are repeated five times independently.

Moreover, HSV augmentation enhances generalization during the single-center classifier training phase, whereas StainLUT operates during cross-center testing, making the two methods complementary. We therefore combine both, resulting in further improvements in cross-center generalization (Fig. 5A, sixth column). We define all locations with predicted probability values greater than 0.5 as detected tumor regions and compare them against the expert-annotated mask (Fig. 5A, second column) to quantitatively evaluate performance using the F1 Score and intersection over union (IoU). Fig. 5B presents the results and trends for the different schemes. Notably, StainLUT significantly improves the cross-center performance of the single-center model, with the best result achieved when combined with HSV augmentation. Finally, we compare the performance of different classification models at the patch level. In addition to reporting the quantitative area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) of the cross-center classification approaches (Fig. 5C, right panel), we also train same-center classification models (Fig. 5C, left panel) and dual-center jointly trained models (Fig. S6B). It can be seen that the model trained with the same center has the high AUC during testing even without HSV augmentation during training. Cross-center patch-level classification tests reveal that StainLUT is more effective than HSV augmentation in enhancing the performance of single-center models (Table S5). When combined, their performance approaches that of the same-center and dual-center jointly trained classifiers with HSV augmentation. This suggests that single-center AIDP models developed by large medical institutions with sufficient data can achieve exceptional cross-center performance when supported by the proposed self-supervised StainLUT. Such an approach could benefit smaller hospitals with limited data and resources. This model facilitates the introduction of cutting-edge technology to smaller hospitals, narrowing the gap in medical services between large and small institutions, and promoting healthcare equity. Moreover, the hospital-centric approach avoids the need for multi-institutional data sharing with developers, mitigating the risk of patient data privacy breaches.

Discussion

In large healthcare institutions, pathology analysis and diagnostics benefit from specialized expertise and experience, which attract a larger patient base and provide access to extensive medical resources. Training AIDP models within a single-center framework, tailored to such institutions, not only circumvents the need to share data across multiple centers, but also reduces the risk of data breaches. It ensures compliance with privacy regulations and protection of patient privacy to the greatest extent possible. By exploiting the structural similarity of pathology images from the same disease type across different medical centers and applying classical color transformation LUTs, we introduce a grayscale-domain self-supervised method, StainLUT. This approach helps mitigate the impact of staining variations, a key obstacle in deploying single-center models across different pathology centers. We demonstrate that it can not only enable normalization toward a specific staining style (Fig. 3 and Figs. S1–S3), but also learn the disease staining characteristics of a single medical center. It adaptively normalizes data from unknown institutions to the current center’s style based on image scene and context (Fig. 4). Leveraging this capability, it can achieve WSI-level stain normalization (Fig. S7). StainLUT is further applied to the single-center AIDP models, demonstrating a significant improvement in cross-center generalization, with performance comparable to models trained on data from the same institution (Fig. 5).

Traditionally, developing robust AIDP models across multiple institutions has required sharing datasets with developers, risking patient privacy breaches. Even sharing non-identifying histology images may still jeopardize privacy because WSIs inherently contain biometric identifiers-unique tissue patterns can enable patient re-identification via cross-dataset linkage57. Moreover, AI models can exploit morphological features to match WSIs with high accuracy, undermining anonymity even in the absence of metadata58. Residual technical artifacts (e.g., scanner-specific signatures) and rare disease contexts further amplify re-identification risks, necessitating alternatives like FL that do not require centralized data. FL offers a trade-off between model performance and privacy protection, albeit often at the cost of reduced performance compared to models trained on centralized data. We demonstrate that, with sufficient single-center training data, the self-supervised StainLUT can enable AIDP models to achieve generalization comparable to that of centralized training models (Figs. 5C, S6B). Additionally, as shown in Table 1, we summarize the privacy protection capabilities of both approaches. Compared to FL, our self-supervised StainLUT framework provides a distinct privacy-preserving paradigm that is particularly advantageous in scenarios prioritizing operational simplicity, minimal communication overhead, and stringent data isolation, offering a practical alternative for model dissemination within a defined disease domain (Note S1).

Although StainLUT, developed for large medical institutions, can enhance the generalization of the center’s AIDP model and normalize the staining of unknown centers, like all data-driven approaches, its performance may degrade when test data significantly deviates from the training distribution. This limitation is particularly evident within our privacy-preserving framework. For instance, for sarcomas with significant intra-class variability and contain dozens of subtypes59, single-center training data often struggle to capture the full range of morphological variations in rare lesions. Therefore, we emphasize that the proposed method is more suitable for development within a single center that has a large data foundation for common cancer types with low intra-class variability. An ablation study on the MIDOG21 dataset60, which has low intra-class variability, revealed that StainLUT’s performance saturates at a small fraction of the training data (Fig. S11), demonstrating high data efficiency. This suggests that the data required for effective normalization is manageable and is likely tied to the complexity of the target center’s color space and the diversity of image content. The core value of StainLUT lies in providing privacy-compliant, cross-center solutions for common cancers or widely distributed pathology types, thereby enhancing the generalizability and accessibility of digital health innovations from large medical institutions.

In addition, our current work is primarily based on breast cancer data, the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women worldwide. While StainLUT demonstrates compelling performance in cross-center normalization for breast cancer, we acknowledge that its validation across a wider range of cancer types and imaging protocols is necessary to fully establish its generality. In the next phase, we anticipate StainLUT to play an adjuvant role across additional cancer types. Given its promising performance across classification, detection and localization tasks, exploring StainLUT’s utility in other areas such as tissue instance segmentation, weakly-supervised whole-slide analysis, and even prognosis prediction based on morphological features represents a highly compelling future research agenda. Furthermore, during the dataset preparation phase, the current quality control (QC) pipeline-such as excluding WSIs with intra-center staining anomalies-relies on manual inspection, which may not be scalable for extremely large datasets. Developing automated QC tools, for example deep learning-based methods for detecting staining abnormalities and artifacts, will be an important direction to facilitate the clinical adoption of StainLUT. Moreover, StainLUT is fundamentally a self-supervised stain mapping technique. Our additional experiments on the MIDOG21 dataset demonstrate that it can effectively normalize the imaging styles of different pathology scanners and assist downstream AIDP detection models (Fig. S8 and Fig. S9). Given the generality of the underlying methodology, we anticipate that StainLUT to contribute to areas such as fading restoration of historical slides, stain-to-stain transformation, and label-free virtual staining61.

Intuitively, converting H&E stained images into a public grayscale domain helps preserve key histological structures and features, offering a straightforward way to protect patient data privacy while standardizing image styles across different pathology centers. However, this is unacceptable because it compromises the gold standard for pathological diagnosis. Pathologists rely on a combination of color and morphology for accurate diagnosis, marking it impossible to discard color information in their workflow. Furthermore, AIDP models based on grayscale inputs may overly rely on suboptimal features like texture, potentially reducing sensitivity to true lesions. Fortunately, the stain normalization achieved by StainLUT based on the grayscale domain can effectively recover the diagnostic information that color provides (Fig. S6A and Fig. S10). Meanwhile, its powerful real-time processing offers the same convenience as grayscaling (Table S4). Additionally, a key theoretical consideration is the potential loss of diagnostically relevant information during the RGB-to-grayscale conversion. We posit that for many H&E stained tissues, particularly within the same disease type, color information is often correlated with underlying morphological structures (e.g., nuclear hematoxylin intensity, cytoplasmic eosinophilia), which are largely preserved in the grayscale domain. However, this assumption may not hold in scenarios where color itself is a primary diagnostic marker (e.g., certain pigmented lesions or special stains). Therefore, the generalizability of StainLUT to such applications remains an open question and a valuable direction for future research.

Overall, the self-supervised StainLUT framework enables stain normalization for data from the same disease type at previously unseen institutions during testing, eliminating inter-center stain variability. This approach reduces the risk of privacy breaches, offering a viable solution for safeguarding patient data, particularly in healthcare settings with stringent privacy regulations. Additionally, StainLUT enhances the generalizability of single-center AIDP models, allowing smaller hospitals to have an opportunity to benefit from high-quality diagnostic support comparable to that available in larger institutions. In today’s booming DP foundation models and increasing attention to data privacy, the self-supervised StainLUT contributes to facilitating the development of secure and trustworthy AI-assisted diagnosis.

Methods

Pathology datasets

We train single-center StainLUT models on two datasets, TNBC49,50 and CAMELYON1654, respectively. The former is used to verify the basic capability of shifting towards a certain fixed staining style and is compared qualitatively and quantitatively with existing recognized methods. The latter demonstrates the adaptive stain normalization capability of StainLUT for the pathological image scene and content, and further gives its utility to assist the WSI-level stain normalization and downstream AIDP model. Specifically, we apply the latter to the CAMELYON17 dataset56 and demonstrate that the AIDP model trained on Center 1 of CAMELYON16 can achieve tumor classification and localization for WSI patches on Center 2 of CAMELYON17. The WSI patches for CAMELYON16 and CAMELYON17 are extracted and divided as described in Note S2, and we refer to the previous extraction approach55. We also train the StainLUT model and the downstream AIDP detection model centered on single-scanner data on the MIDOG21 dataset60, demonstrating the ability of StainLUT to normalize different scanner imaging styles as well as enhance the detection model’s generalization of mitotic figures across other scanner data. The detection model is developed based on RetinaNet62. The single-scanner data is randomly divided into a training set and a validation set with a ratio of 8 to 2, while data from other scanners served as test data (Note S3). All images in the publicly available MIDOG21 dataset come from the same lab and have thus similar staining intensity, i.e., all visible differences in representation can be attributed to a different digital representation by the acquisition device.

StainLUT architecture

StainLUT is a novel stain normalization method, as in Fig. 2, and its non-preprocessing architecture mainly contains four related parts, namely Predictor, Encoder, the stainLUTs fusion, and quadrilinear interpolation, where the last is implicitly used to compute the transformation results of the grayscale-context concatenated images in context-aware stainLUT. The utility of Predictor and Encoder architectures (Table S1 and S2) has been clearly demonstrated in previous work47,48, and here we rationally use them to perceive the diverse scene and content of pathology images in different tissue regions.

Specifically, Predictor weights n predefined basis stainLUTs in the form of output parameters during model training to improve the adaptive stain normalization capability. These parameters are divided into two categories: weights \(W=\{{w}_{{r}_{1}},{w}_{{r}_{2}},...,{w}_{{r}_{3n}},{w}_{{g}_{1}},{w}_{{g}_{2}},...,{w}_{{g}_{3n}},{w}_{{b}_{1}},{w}_{{b}_{2}},...,{w}_{{b}_{3n}}\}\) and biases B = {β1, β2, . . . , βn}. Let the number of parameters output by Predictor is p, then p = 10n. Our Encoder functions based on the grayscale domain, and the visualized CM shows that it can distinguish different colors corresponding to similar content (Fig. S4), which helps StainLUT achieve more accurate self-supervised mapping (Fig. S5). Let the input pathology image be I, then the CM output by the Encoder is concatenated with its three-channel gray image Igray to form a four-channel grayscale-context concatenated image Igc. We denote this process as:

To generate the context-aware stainLUT Φ = (Φr, Φg, Φb) with stronger stain capability, we leverage the adaptive parameters output by Predictor to achieve the fusion of basis stainLUT \({\varphi }_{l}=({\varphi }_{l}^{r},{\varphi }_{l}^{g},{\varphi }_{l}^{b})\), where l = 1, 2, . . . , n. The fusion process is as follows:

where c ∈ {r, g, b} denotes one of the red, green and blue channels in RGB color space.

Based on the four-channel Igc and the fused Φ, quadrilinear interpolation is used to obtain the output image O. The basis stainLUT is based on the 4-dimensional LUT48 and is repeatedly extended once by pre-defined values to perform lookup operations in 4-dimensional space. Let the pixel value at any position (x, y) in Igc be Px,y = (Px,y,r, Px,y,g, Px,y,b, Px,y,cm), then for any Px,y mapped into Φ we first construct its input index \(({i}^{{\prime} },{j}^{{\prime} },{k}^{{\prime} },{h}^{{\prime} })\) and minimum sampling point coordinate (i, j, k, h), as follows:

where \(\varpi =\frac{255}{T-1}\), ⌊ ⋅ ⌋ is the floor function; i, j, k, h ∈ {0, 1, 2, . . . , T − 1} and T represents the number of discrete values along each color dimension of the basis stainLUTs. Then the output RGB values \({O}_{({i}^{{\prime} },{j}^{{\prime} },{k}^{{\prime} },{h}^{{\prime} })}=({P}_{out}^{x,y,r},{P}_{out}^{x,y,g},{P}_{out}^{x,y,b})\) can be obtained in the fused Φ by quadrilinear interpolation using the 16 nearest-neighbor coordinate points of \(({i}^{{\prime} },{j}^{{\prime} },{k}^{{\prime} },{h}^{{\prime} })\). Let \({d}_{i}^{r}={i}^{{\prime} }-i\), \({d}_{j}^{g}={j}^{{\prime} }-j\), \({d}_{k}^{b}={k}^{{\prime} }-k\), \({d}_{h}^{cm}={h}^{{\prime} }-h\,{d}_{i+1}^{r}=1-{d}_{i}^{r}\), \({d}_{j+1}^{g}=1-{d}_{j}^{g}\), \({d}_{k+1}^{b}=1-{d}_{k}^{b}\), \({d}_{h+1}^{cm}=1-{d}_{h}^{cm}\), then the interpolation process can be expressed as:

where c ∈ {r, g, b} and each \({O}_{(i+\hat{i},j+\hat{j},k+\hat{k},h+\hat{h})}^{c}\) is the determined value returned from the lookup in Φ. Thus we get the color transformation result of Igc at pixel position (x, y). Since all pixels can be looked up independently and in parallel in Φ, the output image O can be obtained in real time. It is worth noting that the interpolation operation is differentiable. During the self-supervised training, the elements in the basis stainLUTs can be updated by back-propagated gradient, as can the network parameters in the Predictor, Encoder.

StainLUT optimization

The goal of StainLUT is to learn the self-supervised mapping from the public grayscale domain image to the input pathology image I. Suppose the batch size in the training process is N, combined with the output image O obtained through the quadrilinear interpolation described above, we use the mean squared error (MSE) as the self-pairing loss function, which is defined as follows:

Moreover, to avoid extreme color conversion during training and enhance the model robustness, we use two regularization terms48 to control the learnable parameter changes, as follows:

where εs and εm are the weights to balance \({L}_{s}^{lut}\) and \({L}_{m}^{lut}\). The smooth regularization term \({L}_{s}^{lut}\) can ensure the local smoothing of the elements in basis stainLUTs and suppress the generation of artifacts. It is defined as follows:

The monotonicity regularization term \({L}_{m}^{lut}\) is used to maintain the robustness of the staining transformation and make the training model converge quickly, as follows:

where g( ⋅ ) is the ReLU activation function. Formally, the final loss function for optimizing StainLUT is defined by:

StainLUT training

We train the StainLUT stain normalization model from scratch using Adam optimizer63 with default parameter settings. The learning rate is set at 10−4 and the batch size of 1. We recommend setting the number n of basis stainLUTs to be 3 and the number T of discretized color values in RGB space to be 33. The CNN parameters in Predictor and Encoder are randomly initialized. All basis stainLUTs are initialized to be the identity mapping. The weight factors εs and εm in the loss function are 10−4 and 10 respectively. The pathological images input to the network are randomly rotated or mirrored during training. Due to the huge training data in Center 1 of CAMELYON16, we do not perform CR preprocessing for fast convergence. All training and testing experiments for StainLUT models are conducted using PyTorch on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 GPU.

Evaluation protocols

We use the common full-reference metrics PSNR and SSIM to quantitatively evaluate the style consistency between the stain-normalized image O and the target image I in the TNBC dataset experiments. The PSNR index is defined as:

where H and W represent the height and width of the target image. The SSIM index is defined as follows:

where C1 and C2 are two constants used to avoid zero denominators; \(\bar{I}\) and \(\bar{O}\) represent the means of I and O, respectively; σI and σO represent the standard deviations of I and O, respectively; and σIO represents the covariance of I and O. The specific calculation of SSIM follows the default settings51 and its value is usually between 0 and 1. Higher PSNR and SSIM scores indicate that the difference is smaller and the style is closer between the stain-normalized image and the target image.

UMAP is a dimensionality reduction method commonly used for visualization and feature learning of high-dimensional data52. It is based on the theory of manifold learning, which embeds high-dimensional data into a low-dimensional space, thus facilitating human observation and understanding of the structure of the data. We use UMAP to project the color features of the source and target domains into a two-dimensional space to evaluate their differences in staining styles as per previous work64. The F1 Score and IoU are used to quantitatively evaluate the WSI localization performance for tumor tissue. They are defined as follows:

where Precision = TP/(TP + FP) and Recall = TP/(TP + FN); TP is true positive, FP is false positive and FN is false negative. The F1 Score and IoU range is between 0 and 1, and the larger the value, the closer the prediction localization result is to the GT annotation. We use AUC to evaluate the binary classification performance of the AIDP model for tumor and non-tumor patches, with a score closer to 1 indicating a better model. AUC is a common indicator for measuring the performance of classification models65. It measures the ability of the model to distinguish between positive and negative classes by evaluating the model’s performance under all possible classification thresholds, and can comprehensively reflect the overall performance of the model.

Data availability

The CAMELYON datasets are available at https://camelyon17.grand-challenge.org/. The MIDOG21 dataset is available at https://zenodo.org/records/4643381. The data that support the findings of this study are also available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Example testing images and network models are available together with our code at: https://github.com/XuLabZJU/StainLUT.

Code availability

The code of StainLUT is available in XuLabZJU/StainLUT on GitHub and can be accessed via this link https://github.com/XuLabZJU/StainLUT.

References

Madabhushi, A. & Lee, G. Image analysis and machine learning in digital pathology: challenges and opportunities. Med. Image Anal. 33, 170–175 (2016).

Pantanowitz, L. et al. Twenty years of digital pathology: an overview of the road travelled, what is on the horizon, and the emergence of vendor-neutral archives. J. Pathol. Inform. 9, 40 (2018).

Hanna, M. G., Parwani, A. & Sirintrapun, S. J. Whole slide imaging: technology and applications. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 27, 251–259 (2020).

Schüffler, P. J. et al. Integrated digital pathology at scale: a solution for clinical diagnostics and cancer research at a large academic medical center. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 28, 1874–1884 (2021).

Campanella, G. et al. Clinical-grade computational pathology using weakly supervised deep learning on whole slide images. Nat. Med. 25, 1301–1309 (2019).

Shmatko, A., Ghaffari Laleh, N., Gerstung, M. & Kather, J. N. Artificial intelligence in histopathology: enhancing cancer research and clinical oncology. Nat. Cancer 3, 1026–1038 (2022).

Wen, Z. et al. Deep learning in digital pathology for personalized treatment plans of cancer patients. Semin. Diagnostic Pathol. 40, 109–119 (2023).

Luo, L. et al. Deep learning in breast cancer imaging: a decade of progress and future directions. IEEE Reviews in Biomedical Engineering 1–20 (IEEE, 2024).

Jiang, H., Yin, Y., Zhang, J., Deng, W. & Li, C. Deep learning for liver cancer histopathology image analysis: A comprehensive survey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 133, 108436 (2024).

Van Panhuis, W. G. et al. A systematic review of barriers to data sharing in public health. BMC Public Health 14, 1–9 (2014).

Cath, C. Governing artificial intelligence: ethical, legal and technical opportunities and challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 376, 20180080 (2018).

Jobin, A., Ienca, M. & Vayena, E. The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 389–399 (2019).

Theodorou, A. & Dignum, V. Towards ethical and socio-legal governance in AI. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 10–12 (2020).

Prictor, M. Data breach notification laws-momentum across the Asia-Pacific region. J. Bioethic. Inquiry 1–4 (2023).

Tovino, S. A. Patient privacy and health information confidentiality in the United States of America. In Privacy and Medical Confidentiality in Healthcare, 241–270 (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2023).

Jin, R. & Li, X. Backdoor attack and defense in federated generative adversarial network-based medical image synthesis. Med. Image Anal. 90, 102965 (2023).

Konecny, J. et al. Federated learning: Strategies for improving communication efficiency. arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.054928 (2016).

Rieke, N. et al. The future of digital health with federated learning. NPJ Digit. Med. 3, 1–7 (2020).

Nguyen, D. C. et al. Federated learning for smart healthcare: a survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 1–37 (2022).

Usynin, D., Klause, H., Paetzold, J. C., Rueckert, D. & Kaissis, G. Can collaborative learning be private, robust and scalable? In International Workshop on Distributed, Collaborative, and Federated Learning, 37–46 (Springer, 2022).

Usynin, D. et al. Adversarial interference and its mitigations in privacy-preserving collaborative machine learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 749–758 (2021).

Sun, G. et al. Data poisoning attacks on federated machine learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 9, 11365–11375 (2021).

Shen, Y. et al. A federated learning system for histopathology image analysis with an orchestral stain-normalization gan. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 42, 1969–1981 (2023).

Richardson, S., Lawrence, K., Schoenthaler, A. M. & Mann, D. A framework for digital health equity. NPJ Digital Med. 5, 119 (2022).

Bruce, C. et al. Transforming diagnostics: the implementation of digital pathology in clinical laboratories. Histopathology (2024).

Litjens, G. et al. 1399 H&E-stained sentinel lymph node sections of breast cancer patients: the CAMELYON dataset. GigaScience 7, giy065 (2018).

Weinstein, J. N. et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer Analysis Project. Nat. Genet. 45, 1113–1120 (2013).

Pena, G. P. & Andrade-Filho, J. S. How does a pathologist make a diagnosis? Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 133, 124–132 (2009).

De Matos, J., Ataky, S. T. M., de Souza Britto Jr, A., Soares de Oliveira, L. E. & Lameiras Koerich, A. Machine learning methods for histopathological image analysis: A review. Electronics 10, 562 (2021).

Khan, A. M., Rajpoot, N., Treanor, D. & Magee, D. A nonlinear mapping approach to stain normalization in digital histopathology images using image-specific color deconvolution. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 61, 1729–1738 (2014).

Ciompi, F. et al. The importance of stain normalization in colorectal tissue classification with convolutional networks. In IEEE 14th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging, 160–163 (IEEE, 2017).

Salvi, M., Michielli, N. & Molinari, F. Stain color adaptive normalization (scan) algorithm: separation and standardization of histological stains in digital pathology. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 193, 105506 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Detecting cancer metastases on gigapixel pathology images. arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.02442 (2017).

Tellez, D. et al. Quantifying the effects of data augmentation and stain color normalization in convolutional neural networks for computational pathology. Med. Image Anal. 58, 101544 (2019).

Ruifrok, A. C. & Johnston, D. A. et al. Quantification of histochemical staining by color deconvolution. Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol. 23, 291–299 (2001).

Zheng, Y. et al. Adaptive color deconvolution for histological wsi normalization. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 170, 107–120 (2019).

Vahadane, A. et al. Structure-preserving color normalization and sparse stain separation for histological images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 35, 1962–1971 (2016).

Zanjani, F. G., Zinger, S., Bejnordi, B. E., van der Laak, J. A. & de With, P. H. Stain normalization of histopathology images using generative adversarial networks. In IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging, 573–577 (IEEE, 2018).

Shaban, M. T., Baur, C., Navab, N. & Albarqouni, S. StainGAN: Stain style transfer for digital histological images. In IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging, 953–956 (IEEE, 2019).

Zhou, N., Cai, D., Han, X. & Yao, J. Enhanced cycle-consistent generative adversarial network for color normalization of H&E stained images. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention, 694–702 (Springer, 2019).

Cong, C. et al. Colour adaptive generative networks for stain normalisation of histopathology images. Med. Image Anal. 82, 102580 (2022).

Vasiljević, J., Nisar, Z., Feuerhake, F., Wemmert, C. & Lampert, T. Cyclegan for virtual stain transfer: Is seeing really believing? Artif. Intell. Med. 133, 102420 (2022).

Salvi, M., Branciforti, F., Molinari, F. & Meiburger, K. M. Generative models for color normalization in digital pathology and dermatology: Advancing the learning paradigm. Expert Syst. Appl. 245, 123105 (2024).

Salehi, P. & Chalechale, A. Pix2pix-based stain-to-stain translation: A solution for robust stain normalization in histopathology images analysis. In International Conference on Machine Vision and Image Processing, 1–7 (IEEE, 2020).

Selan, J. Using lookup tables to accelerate color transformations. GPU Gems 2, 381–392 (2005).

Zeng, H., Cai, J., Li, L., Cao, Z. & Zhang, L. Learning image-adaptive 3D lookup tables for high performance photo enhancement in real-time. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44, 2058–2073 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Prior visual-guided self-supervised learning enables color vignetting correction for high-throughput microscopic imaging. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 29, 2669–2682 (2025).

Liu, C., Yang, H., Fu, J. & Qian, X. 4D LUT: learnable context-aware 4D lookup table for image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 32, 4742–4756 (2023).

Naylor, P., Laé, M., Reyal, F. & Walter, T. Segmentation of nuclei in histopathology images by deep regression of the distance map. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 448–459 (2018).

Graham, S. et al. Hover-net: Simultaneous segmentation and classification of nuclei in multi-tissue histology images. Med. Image Anal. 58, 101563 (2019).

Wang, Z., Bovik, A. C., Sheikh, H. R. & Simoncelli, E. P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13, 600–612 (2004).

McInnes, L., Healy, J., Saul, N. & Großberger, L. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection. J. Open Source Softw. 3 (2018).

Macenko, M. et al. A method for normalizing histology slides for quantitative analysis. In IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging, 1107–1110 (IEEE, 2009).

Bejnordi, B. E. et al. Diagnostic assessment of deep learning algorithms for detection of lymph node metastases in women with breast cancer. JAMA 318, 2199–2210 (2017).

Li, Y. & Ping, W. Cancer metastasis detection with neural conditional random field. In Medical Imaging with Deep Learning (2018).

Bandi, P. et al. From detection of individual metastases to classification of lymph node status at the patient level: the CAMELYON17 challenge. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 550–560 (2018).

Holub, P. et al. Privacy risks of whole-slide image sharing in digital pathology. Nat. Commun. 14, 2577 (2023).

Ganz, J., Ammeling, J., Jabari, S., Breininger, K. & Aubreville, M. Re-identification from histopathology images. Med. Image Anal. 99, 103335 (2025).

Hayes, A. J. et al. Uk guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Br. J. Cancer 132, 11–31 (2025).

Aubreville, M. et al. Mitosis domain generalization in histopathology images-the midog challenge. Med. Image Anal. 84, 102699 (2023).

Bai, B. et al. Deep learning-enabled virtual histological staining of biological samples. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 57 (2023).

Lin, T.-Y., Goyal, P., Girshick, R., He, K. & Dollar, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 42, 318–327 (2020).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 1–15 (2015).

Wagner, S. J. et al. Structure-preserving multi-domain stain color augmentation using style-transfer with disentangled representations. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention, 257–266 (Springer, 2021).

Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 27, 861–874 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82572448), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LZ23H180002), Key R&D Program of Zhejiang (2024C03067 and 2024C03056), the Key Projects for Hangzhou Science and Technology Bureau (20231203A13), and Zhejiang University K.P.Chao’s High Technology Development Foundation (2022RC009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W., X.L. and Y.X. conceived the project. J.W. developed the method with the help of X.L., H.Y., Y.Z. and L.J. Data extraction was performed by J.W., Y.Z. and L.J. J.W., J.Y. and H.Y. performed experiments and formal analysis. J.W. wrote the original manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript. J.Y., X.L., J.Z. and Y.X. revised the manuscript. Y.X. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Yu, J., Yang, H. et al. Self-supervised stain normalization empowers privacy-preserving and model generalization in digital pathology. npj Digit. Med. 9, 22 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02196-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02196-8