Abstract

Sensitive and accurate determination of margins between breast-conserving surgery (BCS) is challenging. This study provided a novel approach and biomarker for margin detection of BC through multi-modality imaging of femtosecond label-free imaging (FLI) microscopy and imaging mass spectrometry (IMS) plus machine learning (ML). The regions of interest (ROI) identified by FLI microscopy closely match tissue micro-regions diagnosed by pathologists. Additionally, a biomarker panel comprising taurine, threonate, and glutamate was established for classifying BC and tumor-adjacent noncancerous breast (TANB) tissues. Among these, taurine with higher abundance was confirmed as a potential biomarker to assess positive margins. Elevated level of taurine was associated with poor overall survival in BC patients. Functional analysis validated pro-tumorigenic effect of taurine in BC cell lines. Overall, the integration of FLI microscopy and IMS enables rapid visualization of cellular structures and metabolites in unlabeled tissues, with further analysis identifying taurine as a potential biomarker for margin evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is one of the most prevalent cancers worldwide1. Surgical management remains the cornerstone for treating and curing BC2. Breast-conserving surgery (BCS) followed by radiation therapy has been recommended as the standard therapy for early-stage BC3. Surgical margin status is the presence or absence of malignant cells on the edge or close to the edge of a partial mastectomy specimen4. Accurate assessment of surgical margins status with zero positive margin is crucial for successful BCS application5. Negative margin significantly reduced the need for unnecessary re-excision, thereby lowering the risk of local recurrence and metastasis6,7.

To this end, several intraoperative methods have been developed for margin assessment in BCS5. These methods include frozen section analysis, imprint cytology8, conventional specimen radiography9, intraoperative ultrasonography10, optical coherence tomography11, microcomputed tomography12 etc. Among these, intraoperative frozen section (IFS) examination stands out as the most promising method for guiding margin assessment13. IFS can significantly reduce the need for re-operation caused by residual tumor margins14. However, IFS examination relies on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and skilled pathologists. The tedious pathologic analysis, which takes nearly 30 min, limits its use in hospitals5.

Previous studies have indicated that ~20% to 40% of patients remain positive margins after BCS and require a second operation for tumor clearance15,16,17. Sensitive and accurate determination of margins is challenging due to the absence of reliable biomarkers and efficient platform18. Development of robust intraoperative techniques is essential to facilitate tailored resection and ultimately achieve negative margins, further to optimize the therapeutic outcome. In this context, there is a pressing need to stratify patients based on their molecular characteristics in real-time intraoperative period to offer the most effective therapeutic approach.

Multiphoton microscopy has gained attention for imaging biological tissues, offering significant potential for translational research19,20,21. This label-free and section-free nonlinear optical microscopy enables high-resolution imaging with deep penetration depth22. For instance, femtosecond label-free imaging (FLI) microscope can simultaneously analyze autofluorescence (AF), second harmonic generation (SHG) and third harmonic generation (THG) signals during a single scanning procedure23,24. By combining these multimodal imaging techniques, cellular morphology could be rapidly depicted. FLI microscope, which is performed on freshly resected tissue blocks, holds promise for providing real-time feedback on section margins intraoperatively within minutes25.

Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) is another valuable technique that can depict several molecular images in situ without the need for labeling26. MSI technology shows great potential for specimen characterization during excision surgery due to the high specificity of molecular profiles27, where different markers are separated based on their accurate mass28. Notably, previous research has explored the potential of desorption electrospray ionization MSI in assessing cancer margins, including BC29, pancreatic cancer30, and gastric cancer31. Livia S Eberlin’s work reported that MasSpec Pen enables intraoperative evaluation of surgical margins based on metabolic and lipid information32. While, there remains a lack of specific biomarker to reliably distinguish positive margins.

In this study, we explored a novel approach for BC margin detection by integrating FLI microscope and IMS with machine learning (ML) algorithms. This innovative integration allows for the rapid depiction of cellular structures and metabolites within contiguous unlabeled tissues. Ultimately, we aim to deliver the novel analytical platform and diagnostic biomarker that have potential to be measured intraoperatively for surgical margin assessment, thereby holding promise for enhanced patient management in the future.

Results

Investigating FLI microscope for accurate delineation of section margins

To investigate the ability of FLI to depict the microscopic features of BC and tumor-adjacent noncancerous breast (TANB) tissues without sectioning or staining, we firstly visualized the cell morphology of both tissues by traditional Immunofluorescence (IF) staining. As depicted in Fig. 1A, the terminal ducts lobular units (TDLU) represents a hollow, polarized epithelial structure characterized by bi-layer of CK14+ myoepithelial cells and CK19+ luminal cells. As exemplified by Fig. 1B, the epithelium structure in BC tissue is predominantly composed of CK19+ luminal cells. Given the morphological disparities between BC and TANB tissues33, our study explored the potential of FLI microscope for identifying BC and TANB regions further to assess the excision margins rapidly. Firstly, to expand FLI technology to different applied scene, such as using it in the operating room for fresh tissue detection and in the pathology department for detecting paraformaldehyde (PFA) fixed tissues, we evaluated the FLI microscope for imaging tissues preserved by various methods. Specifically, 4% PFA fixed specimens alongside fresh postoperative tissues were both imaged using FLI microscope. As shown in Fig. 1C, F, tissue blocks were transferred to confocal dishes and mounted onto the target for FLI analysis. Remarkably, FLI microscope allowed us to acquire images from three channels without the need for labeling or sectioning34. Representative images from two BC tissues demonstrated that label-free FLI microscopy accurately depicted cellular structures comparable to standard paraffin section stained with H&E (see Fig. 1D, E, G, H). Specifically, the composite image of three-photon auto-fluorescence (3PFE) (purple channel), SHG (green channel), and THG (yellow channel) channels showed the cellular structure, which could be confirmed by the standard H&E staining images35. 3PFE channel of the tissue is commonly composed of autofluorescence of intracellular molecules, such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide cofactor NAD (P) H, flavin adenine dinucleotide, and pigments, etc. Upon the BC tissue blocks, the 3FPE channel could clearly depict the neoplastic epithelial cells’ structure. THG signal occurs at inhomogeneous interfaces with changes in refractive index36. Thus, it could be used to image lipid droplets, cytomembrane, and karyotheca, etc. Similarly, upon BC tissue blocks, the boundary of lipid droplets was clearly visualized at THG channel. SHG signal was generated from non-centrosymmetric structure such as collagen fibers. As illustrated in Fig. 1D, tissue from the patient diagnosed as invasive carcinoma was mainly composed by tumor cell, adipose, and stroma region. The FLI microscope could clearly depict the morphology of adipose tissue, which shown as the purple irregular polygon outlined by THG channel. Furthermore, the morphology of tumor cytomembrane depicted by FLI microscope was present as the dark purple outline (3PFE channel).

A, B Immunofluorescent staining shows the cellular morphology of TANB (CK14+ myoepithelial cell, CK19+luminal cells) and BC (CK19+luminal cells). C The images of PFA fixed BC tissue block in FLI target. H&E staining of BC tissue section (D) and corresponding FLI images (E) of BC blocks from patient “No. 43” and 20x magnified H&E stain images of different BC cancer tissue regions. F The images of fresh prepared BC tissue block in FLI target. H&E staining of BC tissue section (G) and corresponding FLI images (H) of BC blocks from patient “No. 44” and 20x magnified H&E stain images of different BC cancer tissue regions. The dashed yellow line delineates the margins to discriminate BC and TANB regions. The blue, cyan, and red dashed line outlined the respective regions of mammary gland, tumor area, and stromal region, respectively.

Next, the fresh frozen tissue blocks were also analyzed by FLI microscope. Figure 1F demonstrated that the tissue acquired from patient diagnosed as mucinous carcinoma was composed of tumor cell clusters, stroma, and adjacent normal mammary gland. The normal mammary structure and tumor region could be visualized in a single tissue block by label-free FLI microscope and H&E staining (Fig. 1G, H). In addition, the stromal region which was mainly composed by collagen fibers showed clear signal at SHG channel. And the tumor boundary could be accurately delineated by both H&E staining and FLI microscope. To sum up, FLI microscope could image the tissue blocks without the limit of tissue preservation methods, holding promise of delineating the positive margins with high imaging depth and rapid speed.

Synergism of FLI microscope and MALDI MSI for the rapid identification of TANB and BC tissues

Afterward, we evaluated the potential of FLI microscope for imaging tissue sections. The BC and TANB tissue sections at 35 μm were imaged at three channels simultaneously within 15 min. As shown in Fig. 2, the cellular structure of fresh frozen tissue section imaged by FLI microscope is comparable to the H&E-stained histological images. The composite multimodal images clearly delineated the histological features of normal mammary gland in TANB tissue section and neoplastic epithelial cells in BC tissue section. And the stromal region (green channel) was mostly replaced by the neoplastic epithelial cells in BC tissue section, compared with TANB sections. The mammary mainly consists a mixture of adipose, glandular, and fibrous connective regions. Figure 2A displayed the TANB tissue section acquired from an 86-year-old male (No. 35) was mainly composed of adipose and fibrous connective tissue. The enlarged region showed that the glandular epithelium (3PFE channel) was surrounded by the stroma (SHG channel). While, in the BC tissue section from No. 22 patient, both FLI and H&E staining images showed that no gland-like or papillary structures formation (Fig. 2B). In summary, FLI microscope holds promise as a rapid and label-free technique for distinguishing BC from TANB tissue sections. Our findings pave the way for further clinical applications and diagnostic advancements.

A, B The H&E staining and FLI image of TANB tissue section from patient “No. 35” and BC tissue section from patient “No. 22”. C, D The H&E staining, FLI images of tissue section from patient “No. 6”. E Metabolite - driven tissue section segmentation based on the MALDI MSI data. F MS images of representative images of ions with specific spatial distribution.

In the continuous sections, H&E staining (Fig. 2C) and FLI microscopy (Fig. 2D) faithfully depict the morphological information of BC tissue. In the FLI microscope scanned image (Fig. 2D), 3PFE channel highlights tumor core regions outlined with broken blue line (Fig. 2C), while SHG channel represents the stroma region (Fig. 2D). Using MALDI IMS, molecules-driven tissue section segmentation map reveals the spatial heterogeneity of BC tissue. The tissue regions with similar metabolite and lipid signatures were clustered together, each represented by a specific color. Specifically, tumor cell enriched region almost exhibit red color, whereas, stroma region appears orange color (Fig. 2E). Additionally, to clearly present the heterogeneous distribution of single molecules, MS images of three representative metabolites were shown in Fig. 2F. In particular, metabolite at m/z 281.181 was predominantly distributed in the tumor region, while the metabolite at m/z 237.030 was more abundant in the stroma region compared to the tumor region. Overall, synergism FLI microscope and MALDI IMS platform shows great potential for distinguishing BC and TANB from both the morphological and molecular point of view.

Screening discriminating molecules for margin evaluation by machine learning

We investigated the molecular composition derived from 41 frozen tissue sections using MALDI MSI. The representative mass spectra of BC and TANB tissue sections were shown in Fig. 3A. An orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) analysis distinguished BC from TANB samples, indicating that BC metabolome undergoes remodeling (Fig. 3B). In total, 57 metabolites were statistically different in BC compared against TANB (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and fold change> 1.5 or <0.7) (Fig. 3C). Next, our focus was on constructing good model to differentiate BC from TANB through ML. To achieve this, a total of 276 features were incorporated for constructing four ML models, including Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and XGBoost. The classification efficiency was evaluated by accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, area under the curve (AUC), Kappa, F1-score and Recall, which are regarded as important parameters for the proficiency of the classifier (Fig. 3D). Remarkably, all four algorithms achieved a balanced accuracy of ≥80%, underscoring the promising diagnostic potential of molecules detected by MALDI MSI for BC. Specifically, XGBoost demonstrated the outstanding performance, achieving a balanced accuracy of 96.31% in the context of 205 micro-regions and 87.08% across 41 patients. In comparison, RF achieved 96.94% and 84.39%, DT achieved 93.42% and 83.91%, SVM achieved 96.16% and 82.05%, respectively (Fig. 3D, E). Subsequently, we employed RF and XGBoost-score-based methods for feature selection. The Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) value quantifies the contribution of each variable to the predictive probability of BC for individual specimens. Top 15 features were selected based on the highest SHAP values during XGBoost training (Fig. 3F). Afterward, the top 5 features with highest mean decrease in Gini index of RF model were identified in Fig. 3G. Figure 3H displayed the relative intensity of representative 5 features in BC and TANB tissues. The AUC of the representative 3 m/z values were visualized in Fig. 3I. These selected 3 metabolomic features were subsequently identified as taurine, threonate, glutamate using accurate Orbitrap MS and MetFrag website37 (Fig. 4E–G), and further were constructed as the biomarker panel. The constructed XGBoost model, utilizing these top 3 features, achieved an impressive AUC of 0.985 (95%CI: 0.963, 1.000) (Fig. 3I). To ensure the generalizability of our model, we incorporated external validation using an independent dataset from Terunuma, Putluri et al.’s work38, which includes 65 TANB and 67 BC samples (hereafter referred to as the JCI cohort). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2A and 2B, when the XGBoost model constructed with taurine, threonate and glutamate was applied to the independent JCI cohort, the model maintained discriminative ability with an AUC of 0.997 (95%CI: 0.978, 1.000). The consistency of this result across distinct cohorts underscores the robustness of the model.

A Average mass spectra of BC (n = 26) and TANB (n = 15) tissue sections. B OPLS-DA analysis of MALDI MSI-derived metabolites data from 205 microregions comparing TANB tissues (colored in purple) and BC tissues (colored in blue). C Volcano plot of the detected metabolites in 41 sections (BC tissue sections versus TANB tissue sections). Significantly differential metabolites are colored in purple (up-regulated) and blue (down-regulated).; the others are colored gray. D, E Model evaluation of 207 features from 205 micro-region and 41 tissue sections based on four ML algorithm, including Recall, F1-score, Kappa, AUC, Sensitivity, Specifity and balanced accuracy. F SHAP plot of top 15 features influencing XGB model’s prediction of BC. G Top 5 features influencing Random Forest model. H The violin plot showed the differential expression of 5 selected features in BC and TANB. The p-value was calculated by a two-tailed t-test (**** represented p < 0.0001). I ROC curves of the biomarker panel (purple line) and three potential biomarkers in discriminating BC and TANB.

Therein, taurine achieved the AUC of 0.975 (95% CI: 0.959, 0.992), threonate achieved the AUC of 0.970 (95%CI: 0.948, 0.992) and glutamate achieved the AUC of 0.971 (95% CI: 0.953, 0.989). Interestingly, these metabolites were all up-regulated in BC tissues. Figure 4A–C displays the MS images of the three metabolites in 26 BC and 14 TANB tissue sections. Although the distribution of three metabolites showed the spatial heterogeneity in BC tissues, the intensity was all higher than that in TANB. Furthermore, taurine levels were consistently elevated in BC compared to TANB in both our MSI cohort and the external JCI cohort (Supplementary Fig. 2C, D). And taurine alone achieved an AUC of 0.883 (95%CI: 0.826, 0.941) in the JCI cohort (Supplementary Fig. 2A). This finding further supports taurine’s potential as a discriminative biomarker for distinguishing BC from TANB.

Assessment of surgical margin status using taurine as a biomarker

Clinically, the practitioner not only need to discriminate BC and TANB tissues, precisely delineation the operative margins is equally important for BCS39. The tissue obtained from patient No. 42 with both positive and negative margins confirmed by the professional pathologist was further used to evaluate the potential of taurine for precise margin assessment in the real world. The margin status in the fresh frozen section was defined as: tumor core outlined by red line, positive margin (0–2 mm) outlined by pink line, close margin (2–3 mm) outlined by pink line, and negative margin (>2 cm) (Fig. 5D) outlined by orange line visualized in the typical H&E images (Fig. 5A, E). Figure 5B displays the FLI image of the continuous sections from patient No.42. FLI image faithfully reflects the morphological characterization depicted by H&E staining. Figure 5C showed that MSI based spatial segmentation could clearly depict the tumor margins. By analogy, we find that taurine was highly expressed in BC tissue compared with TANB tissue (Fig. 5F). Moreover, the intensity of taurine decreases gradually with the increase of edge distance (Fig. 5G). These results suggested taurine have the great potential for the discrimination of different margin status. Importantly, by analyzing the metabolomic and prognostic data published in Atsushi Terunuma’s work38, we firstly analyzed the data from 132 individuals using ROC curve to determine the optimal threshold of taurine for distinguishing between BC and TANB. Subsequently, 67 BC patients were categorized into two groups, a high taurine group, with taurine abundance above the threshold, and a low taurine group, with taurine abundance lower the threshold (Supplementary Table 2). We found that BC patients with high abundance of taurine showed poorer overall survival (OS) compared with the individuals with low abundance (Fig. 5H). Previous study has reported that taurine uptake promotes the malignant behaviors of tumor cells and transactivates immune checkpoint genes and then increase the efficacy of cancer therapies40. The above outcome signifies the potential clinical application of taurine as diagnosis biomarker.

A–C H&E staining, FLI, and MS segmentation map of BC tissue section from patient “No. 42”. D H&E staining of TANB away from the tumor core of 2 cm. E 40× magnified H&E stain image of different tissue regions. F MS image showing the distribution of taurine in BC tissue and TANB tissue sections. G The normalized intensity of taurine in different tissue regions. H Survivorships with Kaplan–Meir curve showed the overall survival (OS) of patients (n = 67) stratified by the intensity of taurine.

Functional validation of taurine in BC tumorigenesis

To verify in silico findings, we treated BC cell lines (MCF7, MDA-MB-231) with taurine. Taurine (200 μM) significantly promoted viability (Fig. 6A, B) and reduced apoptosis in BC cell lines (Fig. 6C, F). It also led to a significant increase in BC cells at synthesis (S) phase and a concomitant decrease in cells at G1 phase (Fig. 6G–J). Additionally, the proliferation of BC cells was markedly enhanced after taurine treatment (Fig. 6K, L). These results showed the pro-tumorigenic effects of taurine by promoting the growth and survival of BC cells.

Discussion

Accurate prediction of surgical margin in patients with BC is significant for patients’ prognosis41. Inadequate surgical margins may result in the increased recurrence rate or additional surgery16. Specifically, tumor margin wider than 2 mm in a specimen was associated with a decreased risk of recurrence than that within 2 mm42. So, effective and accurate surgical margin assessment is crucial for BCS. Our study revealed a relatively comprehensive investigation of multimodal imaging combined with ML for diagnosis of BC tissue at spatial scale. The multimodal imaging composed of FLI and MSI depict the microscopic image that comparable to classic H&E staining without labeling.

The normal mammary comprises grape-like clusters known as TDLU. These TDLU branched throughout the fatty tissues of the breast parenchyma43,44. Nevertheless, a hallmark of BC is the absence of this hollow lumen, primarily due to disruptions in luminal cell polarization45. Additionally, previous studies have revealed that various BC lesions exhibit a loss of acinar organization and filling of the luminal space46,47. The morphological discrepancy between BC and TANB tissue laid the foundation for FLI imaging. Our results revealed that FLI microscopy faithfully reveals morphological features of specimen with different preservation method (including fresh prepared or PFA fixed method) achieved comparable image quality of traditional H&E staining. Interestingly, FLI microscope with larger than 35 micron-thick penetration depth could clearly visualize the BC cells immersed in surrounding adipose area (Fig. 1D, E). However, H&E staining of four-micron-thick section of the same tissue block showed the clear boundary of adipose and tumor area. In addition, by gross observing, the boundary of tumor and adipose tissue showed faint yellow, which cannot be clearly discriminate by the naked eye (Fig. 1D, E). In this case, if the surgeon excised the specimen along the faint yellow boundary visualized by gross observing or along the boundary of adipose and tumor area visualized by the H&E staining, that may lead the positive margin left and re-excision. That demonstrated the advantage of FLI microscopy in identifying the positive margins. Furthermore, because FLI microscope could detected the autofluorescence of tissues based on the intrinsic signals by SHG, THG and 3PFE channels, largely avoiding additional reagents and operation, further to eliminate batch-to-batch variations. It is also worth emphasizing that FLI microscope could image tissue specimen with a large field-of-view, capturing 380 × 380 μm in just 1 s. Due to the high penetration depth and rapid imaging capability of FLI microscope, it could more accurately delineate the negative margin within 15 min (Fig. 1F). Furthermore, the multimodal imaging technology generated histochemical images could reflect the histomorphology of tissue micro-regions diagnosed by pathologists following surgery. That demonstrated that FLI microscope has the potential to be integrated into in operating room or pathology department to assist intraoperative or post-operation diagnostics in future clinical practice.

Despite FLI microscope reveals morphological features compared to traditional H&E staining, it cannot visualize molecular distribution which is helpful for precise diagnosis and treatment in the complex tissues. To address this limitation, MALDI MSI was applied to add additional dimensions to the morphological data, providing both molecular coverage and spatial resolution, which would contribute to precise diagnosis48. Notably, this approach allows label-free detection and rapid assessment (10 s/mm2 tissue), enabling high-throughput data acquisition (>20 tissue/slide). And from a molecular standpoint, we initially conformed taurine as a potential biomarker for the development and diagnosis of BC. In detail, the ions acquired from a total of 41 tissues containing 26 BC and 15 TANB fresh frozen sections were used for model construction and optimization. Notably, this proportion of BC to TANB tissues was not predetermined but arose naturally from the key aspects of our sample collection and processing protocol, designed to reflect clinical reality, technical feasibility, and maximize available resources. In addition, the inherent difficulty in cryo-sectioning adipose-rich TANB tissue was a primary technical contributor to the lower number of usable TANB samples compared to BC samples. Thus, to avoid the inaccuracy caused by small sample size and inherent biological heterogeneity, a total of 205 micro-regions with 77,814 pixels or mass spectra were also used for model evaluation. Importantly, the sample size for a study needs to be estimated at the time, and a sample that is smaller than necessary would have insufficient statistical power to answer our primary research question49. So, we performed a sample size calculation to ensure statistic power. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, When the total sample size is 205, Cohen’s d and statistical power reach 0.41 and 0.80197, respectively. Notably, any level of power ranging between 0.70 and 0.85 might generally be satisfactory. Cohen’s recommendation is that power should be at least 0.8050. Supplementary Fig. 3 demonstrated that when the sample size is 205 (the ratio of TANB and BC was 75:130), the statistical power was 0.80197, which larger than the generally accepted minimum level of power 0.8. That suggests that the current sample size is adequate to detect the observed effect with the desired power.

Given lack of consensus in the utilization of different algorithms, four ML algorithms, including RF, XGBoost, SVM, and DT classifier were explored to discover the most appropriate one for our dataset. Data extension improves the accuracy of the XGBoost model to 96.31% after threefold cross-validation for BC and TANB classification. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time to incorporate XGBoost model into MSI-based data analysis.

In addition, the SHAP values in XGBoost and feature importance in RF were extracted to find the potential biomarker with biological explainability. Interestingly, that taurine, threonate, and glutamate were among the top-ranking features across both SHAP and RF Gini index rankings. That demonstrated that all three metabolites have the potential to be biomarkers and warrant further investigation for their therapeutic potential. Our XGBoost model, constructed using these top three features (taurine, glutamate and threonate), first demonstrated good performance in the our MSI cohort, achieving an AUC of 0.985 (95%CI: 0.963, 1.000). When applied that to the external JCI cohort38, the model maintained discriminative ability with an AUC of 0.997 (95%CI: 0.978, 1.000). This consistent result across distinct cohorts underscores the model’s reliability. Despite the robust performance of our model, certain limitations should be acknowledged. Although SHAP analysis identified several additional m/z features beyond taurine, threonate, and glutamate that significantly contributed to the classification model, these features remain unannotated due to the lack of MS/MS validation. Consequently, we were unable to determine their biological relevance or incorporate them into further functional analyses.

Therefore, considering the easily detectable, quantifiable and promising for application in other analysis platform, taurine with highest abundance and AUC value compared with other two metabolites in BC tissues were chosen as a potential biomarker for further validation. First, the spatial gradient of taurine is consistent with the distance from the tumor margin. To be more specific, the intensity of taurine further decreased with the increasing distance away from tumor core. Taurine is a conditionally essential amino, that not only involve in protein synthesis, but exhibits multiple biological functions51. The increase in taurine in the tumor core might be related to cell proliferation52 or the necessary of protection in the center of the malignant area53. Sonali Sharma et al. proved that taurine, derived from tumor niche, could regulate leukemia growth by driving glycolysis54. Professor Li’s team55 observed that taurine could promote lung tumor growth, with the Azgpa/mTOR axis acting as a key mechanism. Thus, preliminary speculation suggests the increased concentration of taurine in tumor core of BC might be correlated with the cell proliferation of breast cancer cells. Further mechanistic validation will be undertaken to explore the related biological mechanisms about the spatial gradient of taurine in BC microenvironment. Second, we performed functional analysis in vitro further confirmed the pro-tumorigenic effects of taurine. Last, we observed that patients with high taurine levels exhibited a poor prognosis. Integrating the above evidence, we propose that taurine represents a functional biomarker for the assessment of positive margins in BC patients. And beyond that, the data from independent JCI cohort38 further validate that taurine alone achieved an AUC of 0.883 (95%CI: 0.826, 0.941). This finding further supports the taurine’s potential as a discriminative biomarker for distinguishing BC from TANB. Ultimately, the integration of FLI microscope and MSI platform, capable of rapidly visualizing cellular structures and metabolites in unlabeled tissue, could achieve gold-standard H&E quality, showed great potential for intraoperative margin assessment, promising improved patient management in the future.

While a key limitation of this study is the lack of true control tissue from healthy individuals or the contralateral breast of patients. Therefore, we cannot fully discount potential patient-specific systemic factors influencing metabolite levels. While we acknowledge that further external validation across more valid populations and clinical contexts would strengthen our conclusions, and that this is among our planned future work to enhance the translational potential of the study.

Methods

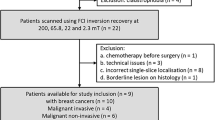

Patient enrollment and tissue collection criteria

BC tissues and TANB tissues (about 2 cm away from the cancer margin) were obtained from BC patients. The inclusion criteria of patients were as follows: (1) Imaging-guided core needle biopsy or postoperative pathology confirming BC; (2) received surgical treatment; (3) had no prior neoadjuvant therapy (NAT). (4) No distant metastasis (M0); (5) Availability of complete clinicopathological data. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Prior ipsilateral breast surgery; (2) Confirmed diagnoses of bilateral BC; (3) Presence of distant metastatic lesions or coexistence with other malignancies. Followed the above criteria and actual availability of qualifying tissues, in this retrospective study, data were collected from 36 patients with primary BC who underwent surgery at Department of General Surgery, Peking University Third Hospital between December 1, 2022, and February 28, 2024. These patients had complete clinicopathological data, no evidence of distant metastases, and had not received NAT. A total of forty-one tissues, including 26 BC and 15 TANB tissues collected from the 36 patients mentioned above. The collection was approved by the local Ethics Committee of National Research institute for Family Planning (Ethics Number: 2020024). Informed consents were obtained from the patients. The detailed clinical information of these patients was summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. Each tissue specimen was divided into 2 parts of which one part was analyzed by FLI microscope; the other part was cryo-sectioned for MALDI MSI analysis (Fig. 7A).

FLI imaging of tissue blocks and sections

For FLI imaging of tissue blocks, the tissue specimens were either immersed in 4% PFA for 18 h or prepared freshly. Afterward, the tissue blocks were transferred to a confocal dish, then ~200 μL of PBS or 4% PFA buffer was added to prevent tissue dryness, correspondingly. The tissue blocks in dish was used for subsequent FLI imaging analysis.

For FLI imaging of tissue sections, tissue blocks following FLI imaging analysis or fresh tissue specimen were cryo-sectioned into slices of 35 μm by Leica CM1860 cryostat (Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany). Then, the slice was mounted on microscope slide (CITOTEST). Subsequently, the tissue sections were fixed in 4% PFA solution, and excess buffer were removed. Then, 4% PFA buffer was added as the mounting medium, carefully covering the coverslip. Finally, nail polish was applied to glue the coverslip in place and prevent the leakage of mounting media.

After processing, the prepared tissue blocks plated in confocal dish or tissue sections mounted on slide were analyzed by FLI microscope system (FI-100, Femtosecond Applications & Research (Guangzhou) Co., Ltd, China) to capture image. The schematic of the system has been clearly illustrated in previous research23. A broad spectrum from 900 to 1200 nm with sub-10 fs pulses, was generated by a home-built femtosecond fiber laser operating at a pulse repetition rate of 12.5-MHz. The laser pulses were then compressed by a self-designed module of pulse shaper and focused by a high numerical aperture objective (UAPON 40XW340; Olympus NA1.15), providing an average power of 20 mW at the sample for high-quality imaging. The signals generated by the specimen were separated into multiple channels (THG 340–380 nm; 3PEF 415–526 nm; SHG 510–570 nm) and collected by corresponding photomultiplier tubes. A 2D galvo scanning system was applied to produce a frame with a size of 500 × 500 pixels in 1 s, displaying a field of view of 360 × 360 μm2. Larger images could be captured frame by frame by moving the motorized translational stage serially, followed by stitching of original frames with a 10% edge overlap to avoid artifacts. Composite images could be produced by combining the original images from all channels with different pseudo colors (THG: yellow; 3PEF: magenta; SHG: green) to demonstrate the abundant morphological information of the specimen.

Histopathological examination of tissues

For H&E staining of frozen sections, the parallel tissue section underwent standard staining protocols56. For immunofluorescence analysis, the fresh frozen tissues were stained with cytokeratin 14 (CK14) and cytokeratin 19 (CK19). The H&E staining of BC and TANB tissues were evaluated by two experienced pathologists under a microscope. When discrepancies arose between the two experienced pathologists in their assessment of BC and TANB tissues, the following steps were followed to ensure consistency and accuracy. First, the two pathologists reviewed their individual evaluations together to identify the specific points of disagreement. They then jointly re-examined the disputed tissue sections under multi-head microscopy, discussing the histological features, e.g., cellular morphology, staining intensity, or pathological grading that led to their differing conclusions. If a consensus could not be reached through this joint review, a third senior pathologist with expertise in BC was consulted. This third reviewer, who was blinded to the initial evaluations, independently assessed the tissues and provided a final evaluation. The majority opinion that agreement between at least two of the three pathologists was ultimately adopted as the definitive result.

MALDI MSI acquisition and preprocessing

Tissue specimens were sectioned at 10 μm thick and thaw mounted onto to an indium tin oxide (ITO) -coated glass slide. The tissue sections were then dehydrated under vacuum for ~15 min. Then, 1,5-Diaminonaphthalene (1,5-DAN) matrix solution (10 mg/mL in 80% acetonitrile) was sprayed onto the sections by electric field-assisted matrix coating method57. Rapiflex mass spectrometer equipped with a 355 nm Nd:YAG laser (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) was used for ion image acquisition. Spatial resolution was set to 100 μm. MSI analysis was performed in the negative ionization mode within a mass range of m/z 100–1000. The laser was irradiated at 100 shots/spectrum. A fresh suspension of red phosphorus (1 mg/mL in acetonitrile) is used for external calibration of MALDI MSI58. Imaging data was recorded by FlexImaging software v 5.1. The selected molecules were identified by atmospheric pressure (AP) MALDI-Orbitrap tandem MS (MS/MS). MetFrag website was used for MS/MS spectrum unfolding37. The signal intensity of each imaging datum in the figure is represented as the total ion current (TIC) normalized intensity59.

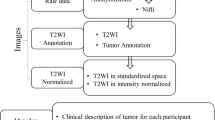

Feature extraction and normalization from MSI

All raw data was directly uploaded to SCiLS Lab MVS software (v. 2021a Pro, SCiLS Lab/Bruker Daltonics) with resample method set to “Auto” and without baseline removal. All data were normalized using TIC. To achieve the automatic and unbiased prediction of BC and TANB tissues at the micro-region or sample basis, we extracted peaks from 5 micro-regions of each BC and TANB specimen, resulting in a total of 205 micro-regions or 41 samples containing 77,814 pixels or mass spectra. Absolute intensity threshold was adjusted to generate a reduced-mass list of the most prominent 276 peaks in the csv format for further processing in R studio and segment the MSI data of the tissue sections. The schematic is shown in Fig. S1. K-means clustering (spatial segmentation) using the selected feature list obtained using the sliding window for thresholding above noise level was done to depict tissue heterogeneity. The average mass spectra of BC and TANB tissues were exported.

Diagnostic model construction using four ML algorithm

Multiple ML models including RF, SVM, XGBoost60, and DT were developed in this study. In total, 276 metabolites were selected as predictors to discriminate the BC and TANB. In the model-development stage, all the four ML classifiers were operated in parallel, independently predict input features. The models were constructed based on the misclassification error averaged from 200 times of threefold cross-validation to bolster model stability and alleviate overfitting. This involved randomly dividing the data set into three distinct subsets of the same size for iterative model training. RF, SVM, XGBoost and DT were performed via xgboost, randomForest (v.4.7.1.2), e1071, and rpart R packages. The performances of these predictive models were compared by means of confusion matrix. ROC curves were plotted by pROC R package61. The selected classifier provided the better classification performance when compared with other models for further verification. Subsequently, their output results were employed to find discriminate variables.

Model interpretability and feature selection

For model interpretability, we attempted to explain the model by conducting a feature importance analysis of classifiers. The individual contributions of features to the predictive capability of the model were identified and ranked by feature importance analysis. The analysis indicated the features with the most influence on the model’s prediction. The overall framework of feature selection is illustrated in Fig. 7B. As shown in Fig. 7B, there were three major steps. First, we analyzed and interpreted the feature effect with SHAP on XGBoost62, and then the most important features were selected. SHAP values showed information for an individual instance (see which feature pulls the outcome in which direction). SHAP is a game-theoretic approach that assigns each feature an importance value based on its marginal contribution to the model output63. XGBoost model prediction employed in this study was explained by SHAP values64. Specifically, SHAP values report the average contribution a feature has on the XGBoost model outcome, across all possible combination of inputs. SHAP values calculated externally from the XGBoost model by shapviz (v 0.9.7) package was used to explore what influence each feature has on the XGBoost model prediction. Second, to understand variable importance, we investigated varlmpPlot which shows mean decrease Gini by RandomForest (v.4.7.1.2). Notably, the mean decrease in Gini coefficient is a measure of how each variable contributes to the homogeneity of the nodes and leaves in the resulting random forest. Third, ROC curves generated by pROC (v. 1.18.5) package in R were used to assess the performance of selected features.

Cell-based functional validation of taurine

Enhanced Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) (Beyotime) was used for cell viability assay. 5000 cells per well were deeded into 96 well plated and treated with taurine at concentration of 200 μM. The taurine was dissolved in PBS. Cell viability was determined by measuring absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm (OD450) for 4 consecutive days. The experiments were conducted with 5 replicates per group.

Cell apoptosis was evaluated using Annexin V-FITC/7-AAD Apoptosis Detection Kit (YEASEN) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For cell cycle analysis, cells were fasted before treatment. After taurine treatment of 2 days, cells were collected and fixed in 70% ethanol at 4 °C for over 2 h, and then stained with 500 μL PI/RNase staining buffer (YEASEN) at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells at room temperature for 15 min in dark. Stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometer (BD FACS Celesta Flow Cytometer, BD Biosciences). FlowJo (version 10.8.1) was used for data analysis. The experiment was conducted with triplicates per group. Cell proliferation was analyzed using BeyoClick™ EdU Cell Proliferation Kit with Alexa Fluor 488 (Beyotime) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Olympus SpinSR SoRa microscope was used for confocal imaging.

Statistical analysis methods

To perform statistical power analysis, we specify the sample size of TANB and BC is 75 and 130, respectively. α-level was set as 0.05. Because it difficult to specify which effect size should be considered the minimum for biological significance. So, we reported power over a range of effect size65. In our practice, the range of effect size was set from 0.1 to 1.5, and generate 50 data points within this interval. Then the relationship between effect size, sample size and power could be calculated.

The resulting 276 peaks were utilized to perform OPLS-DA using ropls package in R (v 1.36.0)66. Differential metabolites were analyzed by a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test (FDR < 0.05 and fold change >1.5 or < 0.7). The volcano plot of Differential metabolites was draw by ggplot2 package (v 3.5.1) in R (v 1.36.0). Kaplan Meier curves for survival were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.5 software.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code for our developed model is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Lima, S. M., Kehm, R. D. & Terry, M. B. Global breast cancer incidence and mortality trends by region, age-groups, and fertility patterns. eClinicalMedicine 38, 100985 (2021).

Matsen, C. B. & Neumayer, L. A. Breast cancer. JAMA Surg. 148 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3393 (2013).

Kirova, Y. M. Radiation therapy (RT) after breast-conserving surgery (BCS) in 2015-The year of radiation therapy advances. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 42, 437–440 (2016).

Singletary, S. E. Surgical margins in patients with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast conservation therapy. Am. J. Surg. 184, 383–393 (2002).

Pradipta, A. R. et al. Emerging technologies for real-time intraoperative margin assessment in future breast-conserving surgery. Adv. Sci. 7, 1901519 (2020).

Schnitt, S. J., Moran, M. S. & Giuliano, A. E. Lumpectomy margins for invasive breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ: current guideline recommendations, their implications, and impact. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 2240–2245 (2020).

Pilewskie, M. & Morrow, M. Margins in breast cancer: how much is enough?. Cancer 124, 1335–1341 (2018).

Horváth, Z. et al. Is intraoperative touch imprint cytology indicated in the surgical treatment of early breast cancers?. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 43, 1252–1257 (2017).

Schaefgen, B. et al. Does conventional specimen radiography after neoadjuvant chemotherapy of breast cancer help to reduce the rate of second surgeries?. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 191, 589–598 (2022).

Kaufman, C. S., Jacobson, L., Bachman, B. & Kaufman, L. B. Intraoperative ultrasonography guidance is accurate and efficient according to results in 100 breast cancer patients. Am. J. Surg. 186, 378–382 (2003).

Cantisani, C. et al. Dynamic optical coherence tomography and reflectance confocal microscopy of basal cell carcinoma of the nipple-areola complex. Br. J. Dermatol. 190, 933 (2024).

Tang, R. et al. Micro-computed tomography (Micro-CT): a novel approach for intraoperative breast cancer specimen imaging. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 139, 311–316 (2013).

Dowling, G. P. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of intraoperative methods for margin assessment in breast cancer surgery: a systematic review & meta-analysis. Breast 76, 103749 (2024).

Long, S. M. et al. Use of intraoperative frozen section to assess final tumor margin status in patients undergoing surgery for oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 148, 911–917 (2022).

McCahill, L. E. et al. Variability in reexcision following breast conservation surgery. JAMA 307, 467–475 (2012).

Pleijhuis, R. G. et al. Obtaining adequate surgical margins in breast-conserving therapy for patients with early-stage breast cancer: current modalities and future directions. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 16, 2717–2730 (2009).

Chagpar, A. B. et al. A randomized, controlled trial of cavity shave margins in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 503–510 (2015).

Tsimberidou, A. M. et al. Molecular tumour boards - current and future considerations for precision oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 843–863 (2023).

Campagnola, P. J. & Loew, L. M. Second-harmonic imaging microscopy for visualizing biomolecular arrays in cells, tissues and organisms. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 1356–1360 (2003).

Parodi, V. et al. Nonlinear optical microscopy: from fundamentals to applications in live bioimaging. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 585363 (2020).

Cui, Y. et al. Evaluation of histopathological response to neoadjuvant therapy in rectal cancer using slide-free, stain-free multimodal multiphoton microscopy. J. Biophotonics 15, e202200079 (2022).

Tu, H. et al. Stain-free histopathology by programmable supercontinuum pulses. Nat. Photonics 10, 534–540 (2016).

Zhang, H. et al. Optical biopsy of laryngeal lesions using femtosecond multiphoton microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express 12, 1308–1319 (2021).

Chen, D. et al. Association of tumor-associated collagen signature with prognosis and adjuvant chemotherapy benefits in patients with gastric cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2136388 (2021).

Mehravar, S. et al. Label-free multi-photon imaging of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Biomed. Opt. Express 7, 148–157 (2016).

Buchberger, A. R., DeLaney, K., Johnson, J. & Li, L. Mass spectrometry imaging: a review of emerging advancements and future insights. Anal. Chem. 90, 240–265 (2018).

Balog, J. et al. Intraoperative tissue identification using rapid evaporative ionization mass spectrometry. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 194ra193 (2013).

Lan, C. et al. Absolute quantification of 2-hydroxyglutarate on tissue by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging for rapid and precise identification of isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations in human glioma. Int. J. Cancer 149, 2091–2098 (2021).

Calligaris, D. et al. Application of desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging in breast cancer margin analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15184–15189 (2014).

Eberlin, L. S. et al. Pancreatic cancer surgical resection margins: molecular assessment by mass spectrometry imaging. PLoS Med. 13, e1002108 (2016).

Eberlin, L. S. et al. Molecular assessment of surgical-resection margins of gastric cancer by mass-spectrometric imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 2436–2441 (2014).

Garza, K. Y. et al. Intraoperative evaluation of breast tissues during breast cancer operations using the MasSpec Pen. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e242684 (2024).

Gadaleta, E. et al. Characterization of four subtypes in morphologically normal tissue excised proximal and distal to breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 6, 38 (2020).

Marx, V. It’s free imaging - label-free, that is. Nat. Methods 16, 1209–1212 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. Quantitative third harmonic generation microscopy for assessment of glioma in human brain tissue. Adv. Sci. 6, 1900163 (2019).

Weigelin, B., Bakker, G. J. & Friedl, P. Third harmonic generation microscopy of cells and tissue organization. J. Cell Sci. 129, 245–255 (2016).

Ruttkies, C., Schymanski, E. L., Wolf, S., Hollender, J. & Neumann, S. MetFrag relaunched: incorporating strategies beyond in silico fragmentation. J. Cheminform. 8, 3 (2016).

Terunuma, A. et al. MYC-driven accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate is associated with breast cancer prognosis. J. Clin. Investig. 124, 398–412 (2014).

Wen, Y., Liu, R., Xie, Y. & Li, M. Targeted SERS imaging and intraoperative real-time elimination of microscopic tumors for improved breast-conserving surgery. Adv. Mater. e2405253 https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202405253 (2024).

Cao, T. et al. Cancer SLC6A6-mediated taurine uptake transactivates immune checkpoint genes and induces exhaustion in CD8(+) T cells. Cell 187, 2288–2304.e2227 (2024).

Kopicky, L., Fan, B. & Valente, S. A. Intraoperative evaluation of surgical margins in breast cancer. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 41, 293–300 (2024).

Bundred, J. R. et al. Margin status and survival outcomes after breast cancer conservation surgery: prospectively registered systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 378, e070346 (2022).

Rauner, G. et al. Breast tissue regeneration is driven by cell-matrix interactions coordinating multi-lineage stem cell differentiation through DDR1. Nat. Commun. 12, 7116 (2021).

Shams, A. Re-evaluation of the myoepithelial cells roles in the breast cancer progression. Cancer Cell Int. 22, 403 (2022).

Debnath, J. & Brugge, J. S. Modelling glandular epithelial cancers in three-dimensional cultures. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 675–688 (2005).

Badve, S. S. & Gökmen-Polar, Y. Ductal carcinoma in situ of breast: update 2019. Pathology 51, 563–569 (2019).

Fessart, D., Begueret, H. & Delom, F. Three-dimensional culture model to distinguish normal from malignant human bronchial epithelial cells. Eur. Respir. J. 42, 1345–1356 (2013).

Basu, S. S. et al. Rapid MALDI mass spectrometry imaging for surgical pathology. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 3, 17 (2019).

Andrade, C. Sample size and its importance in research. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 42, 102–103 (2020).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (L. Erlbaum Associates, 1988).

Liu, R. et al. Taurine and cancer: Biological properties and multifaceted roles in cancer progression. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Rev. Cancer 189403 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2025.189403 (2025).

Moreno, A., Rey, M., Montane, J. M., Alonso, J. & Arús, C. 1H NMR spectroscopy of colon tumors and normal mucosal biopsies; elevated taurine levels and reduced polyethyleneglycol absorption in tumors may have diagnostic significance. NMR Biomed. 6, 111–118 (1993).

Cubillos, S., Obregón, F., Vargas, M. F., Salazar, L. A. & Lima, L. Taurine concentration in human gliomas and meningiomas: tumoral, peritumoral, and extratumoral tissue. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 583, 419–422 (2006).

Sharma, S. et al. Taurine from tumour niche drives glycolysis to promote leukaemogenesis. Nature 644, 263–272 (2025).

Liang, T. L. et al. Taurine and proline promote lung tumour growth by co-regulating Azgp1/mTOR signalling pathway. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 9, 90 (2025).

Slaoui, M., Bauchet, A. L. & Fiette, L. Tissue sampling and processing for histopathology evaluation. Methods Mol. Biol. 1641, 101–114 (2017).

Guo, S., Wang, Y., Zhou, D. & Li, Z. Electric field-assisted matrix coating method enhances the detection of small molecule metabolites for mass spectrometry imaging. Anal. Chem. 87, 5860–5865 (2015).

Shariatgorji, R. et al. Spatial visualization of comprehensive brain neurotransmitter systems and neuroactive substances by selective in situ chemical derivatization mass spectrometry imaging. Nat. Protoc. 16, 3298–3321 (2021).

Fonville, J. M. et al. Robust data processing and normalization strategy for MALDI mass spectrometric imaging. Anal. Chem. 84, 1310–1319 (2012).

Bentéjac, C., Csörgő, A. & Martínez-Muñoz, G. A comparative analysis of gradient boosting algorithms. Artif. Intell. Rev. 54, 1937–1967 (2021).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 12, 77 (2011).

Li, M. et al. Machine learning for predicting risk and prognosis of acute kidney disease in critically ill elderly patients during hospitalization: internet-based and interpretable model study. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e51354 (2024).

Aas, K., Jullum, M. & Løland, A. Explaining individual predictions when features are dependent: more accurate approximations to Shapley values. Artif. Intell. 298, 103502 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2021.103502 (2021).

Roder, J., Maguire, L., Georgantas, R. 3rd & Roder, H. Explaining multivariate molecular diagnostic tests via Shapley values. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 21, 211 (2021).

Thomas, L. E. N. & Juanes, F. The importance of statistical power analysis: an example fromAnimal Behaviour. Anim. Behav. 52, 856–859 (1996).

Wang, Y. & Huang, J. Untargeted metabolomic analysis of metabolites related to body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). Funct. Integr. Genomics 23, 70 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Guangzhou Kapok Plan (No. HMJH-2019-0014) for their generous financial support. The authors also thank Jiamin He (Femtosecond Applications & Research (Guangzhou) Co., Ltd) for her assistance in collecting the FLI images in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y.L. and Y.P. contributed equally to this work. C.Y.L.: Methodology, Data collection, processing, Writing - Original Draft. Y.P.: Human sample preparation, Writing - Review & Editing. M.T.B.: Methodology, Data processing, Writing - Review. H.T.Z.: Methodology, Data processing, Writing - Original Draft. Y.L.: Investigation. T.Z.: Investigation. H.N.W.: Investigation. X.Z.: Investigation. J.H.: Investigation. D. G.: Data processing, validation, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. X.F.C.: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision. H.M.Z: Conceptualization. H.F.G.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lan, C., Peng, Y., Bai, M. et al. Fast multimodal imaging combined with machine learning identifying taurine as a potential marker for breast cancer margin assessment. npj Digit. Med. 9, 32 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02202-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02202-z