Abstract

This study aimed to systematically review and meta-analyze the effectiveness of eHealth-based cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk communication and its impact on health-related outcomes. Twenty-three RCTs were included. The eHealth-based CVD risk communication showed significant improvements in controlling systolic blood pressure (P = 0.03), low-density lipoprotein (P = 0.02), physical activity (P = 0.003), smoking cessation (P = 0.004), disease awareness (P = 0.002), and quality of life (P = 0.03). No significant effects were found for other outcomes, including diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, and overall risk scores. These findings provide valuable insights into the potential role of eHealth-based risk communication in CVD prevention. In addition, existing risk communication interventions are multicomponent, and future research could standardize intervention components and optimize intervention elements using the Behavior Change Techniques Taxonomy and factorial designs, while developing targeted risk communication strategies for different populations to improve health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), including heart disease, cerebrovascular conditions, and disorders of the blood vessels, accounts for approximately one-third of global mortality and remains a major public health challenge worldwide1,2. A core strategy for CVD prevention is the management of modifiable risk factors3. Central to this strategy is the effective communication of individual risk factors and guidance on how to manage them, an approach known as ‘risk communication’. The World Health Organization defines risk communication as the real-time exchange of information, advice and opinions between experts or officials and people facing threats to their survival, health, or social wellbeing4. Risk communication generally includes risk assessment, the selection of appropriate communication strategies and tools, and the implementation of those strategies in clinical practice5. When implemented effectively, CVD risk communication can enhance patients’ understanding of their personal risk, improve awareness, promote informed decision-making, and enhance healthier lifestyle behaviors6. Importantly, mental health, both a known determinant of CVD outcomes and a critical enabler of health behavior change, is essential to consider in evaluating the broader impact of these communication strategies7,8.

Existing reviews have predominantly focused on the format of risk information presentation9,10, the effectiveness of communication strategies11, and the perceptions and experiences of both healthcare providers and patients regarding risk communication12. Although these reviews generally conclude that risk communication can reduce CVD risk factors, some scholars have noted that failing to distinguish between interventions focused solely on CVD risk communication and those integrating additional components may undermine the accuracy of these findings6,13. For example, Bakhit et al.6 included a broad range of both digital and non-digital interventions without clearly differentiating between them, which may have obscured the specific contribution of electronic health (eHealth)-based communication. Building on this observation, this study focuses specifically on the application of eHealth technologies for CVD risk communication. We seek to clearly define the technical modalities that underpin the intervention, thereby mitigating the potential bias introduced by their conflation. The focus on eHealth is further justified by increasing pressure on healthcare systems and limited resources, which underscore the increasing need to enhance the efficiency and reach of risk communication14. eHealth technologies refer to the secure and cost-effective use of digital tools and communication platforms to deliver health services and exchange medical information, presenting a promising solution15. Their growing value in patient education and CVD risk communication has attracted increasing attention from healthcare professionals16,17,18.

This review aims to systematically examine and quantify the effectiveness of eHealth technologies in CVD risk communication, and to assess their impact on patients’ health outcomes. Findings are expected to address existing research gaps and provide an evidence base for optimizing clinical practice and informing relevant policy development.

Results

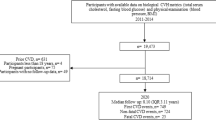

A total of 2992 records were identified initially from seven databases. After removing duplicates and undertaking screening, twenty-three trials were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. The literature screening process is detailed in Fig. 1. The excluded trials along with the reasons for exclusion are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

The twenty-three included trials, published between 2006 and 2024, covered data from thirteen countries. The United States contributed the most trials (n = 6). Among these trials, eleven focused on primary prevention of CVD, ten on secondary prevention, and two on both. The total sample size across the trials was 11,311 participants.

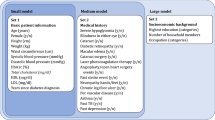

Seven types of eHealth technologies were used across the twenty-three trials, including smartphone applications (n = 9), websites (web-based tool, website, computer-based program) (n = 8), telephone calls (n = 4), email (n = 4), decision support systems (n = 2), electronic health records (n = 2), and short message service (SMS) (n = 1). In six trials, two or more types of eHealth technologies were combined. The functions of eHealth technologies in CVD risk communication included risk assessments, risk presentation, personalized suggestions, tracking or reminding. Further details of the interventions are presented in Table 1.

All trials were rated as having a low risk of bias for random sequence generation. Low risk of bias was also observed for allocation concealment in seventeen out of twenty-three trials (74%), blinding of participants and study personnel in seven trials (30%), and blinded outcome assessment in eighteen trials (78%). Sixteen trials were assessed as having a high risk of bias, primarily due to the absence or inadequacy of blinding procedures. Five trials were rated as having an unspecified risk of bias due to insufficient information. For incomplete outcome data and selective reporting, all trials were rated as low risk of bias. As no outcome included in the meta-analysis had data from more than ten trials, funnel plots were not used to assess potential publication bias, in line with current methodological recommendations19 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1).

Use of eHealth-based CVD risk communication showed a significant reduction (seven trials, SMD = −0.16, 95% CI: −0.30 to −0.02; I² = 39%; P = 0.03) in systolic blood pressure (SBP) (Fig. 3). Subgroup analysis revealed that the intervention showed a stronger effect in the primary prevention (SMD = −0.33, 95% CI: −0.61 to −0.05; I² = 0%; P = 0.02), compared to the secondary prevention (SMD = −0.21, 95% CI: −0.35 to −0.07; I² = 0%; P = 0.004) and combined group (incorporating both prevention levels) (SMD = 0.06, 95% CI: −0.09 to 0.21; P = 0.44). Both the short-term follow-up (≤3 months, SMD = −0.32, 95% CI: −0.69 to 0.05; I² = 0%; P = 0.09) and long-term follow-up (>3 months, SMD = −0.14, 95% CI: −0.30 to 0.02; I² = 52%; P = 0.08) subgroups showed a small reduction without statistically significant changes. Moreover, no significant difference was observed between these two subgroups (P = 0.38) (Supplementary Fig. S2).

a Presents the overall effect for systolic blood pressure; b presents the overall effect for diastolic blood pressure; c presents the overall effect for total cholesterol; d presents the overall effect for high-density lipoprotein; e presents the overall effect for low-density lipoprotein; f presents the overall effect for body mass index. SD standard deviation.Created using Review Manager 5.4.1.

The eHealth group showed a modest but non-significant reduction in diastolic blood pressure (DBP) compared to the control group (seven trials, SMD = −0.07, 95% CI: −0.17 to 0.03; I² = 0%; P = 0.18) (Fig. 3). Similarly, subgroup analysis revealed no significant differences in intervention effects across levels of prevention (primary prevention (SMD = −0.10, 95% CI: −0.38 to 0.18; I² = 0%; P = 0.48), secondary prevention (SMD = −0.05, 95% CI: −0.19 to 0.10; I² = 0%; P = 0.53), combined group (SMD = −0.08, 95% CI: −0.23 to 0.07; P = 0.31)) or follow-up time (≤3 months (SMD = −0.05, 95% CI: −0.41 to 0.30; I² = 0%; P = 0.76), >3 months (SMD = −0.07, 95% CI: −0.17 to 0.03; I² = 0%; P = 0.17)) (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Data from five trials were meta-analyzed to evaluate the impact of eHealth-based CVD risk communication on total cholesterol (TC). The results showed no significant difference between the intervention and control groups (SMD = 0.29, 95% CI: −0.62 to 1.19; I² = 99%; P = 0.53) (Fig. 3). Change in TC did not differ by the follow-up time (SMD = 0.29, 95% CI: −0.62 to 1.19; I² = 99%; P = 0.53). However, significant differences were observed among groups with different prevention subgroups. For the primary prevention subgroup, the intervention showed a trivial and non-significant trend toward a small reduction in risk (SMD = −0.04, 95% CI: −0.17 to 0.10; P = 0.60). In contrast, the secondary prevention subgroup exhibited a statistically significant reduction in risk (SMD = −0.19, 95% CI: −0.33 to −0.04; I² = 0%; P = 0.01). The combined group demonstrated a substantially larger and highly significant positive effect (SMD = 2.02, 95% CI: 1.83 to 2.21; P < 0.00001). (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Five trials evaluated the effect of eHealth-based CVD risk communication on high-density lipoprotein (HDL). Combined results showed that HDL did not significantly decline among those who received the interventions (SMD = 0.38, 95% CI: −0.50 to 1.26; I² = 99%; P = 0.40) (Fig. 3). For follow-up time subgroups (≤3 months vs. >3 months), both subgroups showed non-significant changes, and there was no inter-subgroup difference (P = 0.34). whereas significant differences were found across groups with different prevention levels. The combined group showed a significant improvement in HDL (SMD = 2.02, 95% CI: 1.83 to 2.21; P < 0.00001) compared to the primary prevention subgroup (SMD = −0.07, 95% CI: −0.20 to 0.06; P = 0.28) and the secondary prevention subgroup (SMD = −0.02, 95% CI: −0.16 to 0.13; I² = 0%; P = 0.80), neither of which showed significant changes. (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Meta-analysis results showed significant differences in the changes of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) between the two groups (five trials, SMD = −0.20, 95% CI: −0.36 to −0.03; I² = 62%; P = 0.02) (Fig. 3). Subgroup analysis results showed that significant reductions were observed in the secondary prevention subgroup (SMD = −0.27, 95% CI: −0.42 to −0.12; I² = 26%; P = 0.0005), while the primary prevention subgroup (SMD = −0.03, 95% CI: −0.17 to 0.10; P = 0.62) showed no significant change; by follow-up time, the subgroup with follow-up >3 months showed a significant reduction (SMD = −0.27, 95% CI: −0.42 to −0.12; I² = 26%; P = 0.0005), whereas the subgroup with follow-up ≤3 months showed no significant change (SMD = −0.03, 95% CI: −0.17 to 0.10; P = 0.62) (Supplementary Fig. S6).

There was no significant difference in body mass index (BMI) (four trials) between intervention and control groups (SMD = 0.05, 95% CI: −0.09 to 0.19; I² = 0%; P = 0.46). No significant differences were observed between the different subgroups either (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S7).

Meta-analysis of lifestyles, mental health outcomes, disease awareness and quality of life revealed that eHealth-based CVD risk communication was associated with significant improvements in physical activity, disease awareness, and quality of life (Table 2). However, it did not significantly change diet, medication adherence, depression, or anxiety.

Regarding the cardiovascular risk score (CRS), the eHealth group demonstrated a more substantial reduction compared to the control group. However, no significant overall effect was observed between the intervention and control groups (three trials, SMD = −0.18, 95% CI: −0.67 to 0.30; I² = 92%; P = 0.46). Subgroup analysis indicated significant differences in the intervention effects based on levels of prevention. The primary prevention group showed a significant reduction (SMD = −0.89, 95% CI: −1.30 to −0.48; P < 0.001), secondary prevention group showed no significant change (SMD = 0.00, 95% CI: −0.22 to 0.22; P = 1.00). For follow-up time subgroups, ≤3 months group showed a significant reduction (SMD = −0.89, 95% CI: −1.30 to −0.48; P < 0.0001), >3 months group showed no significant change (SMD = 0.12, 95% CI: −0.09 to 0.34; I² = 60%; P = 0.25) (Fig. 4).

a Shows the effects grouped by different levels of prevention, categorized as “primary prevention”, “secondary prevention”, “combined group” (incorporating both prevention levels); b shows the effects grouped by follow-up time, classified as “short-term ≤3 months” and “long-term >3 months”. SD standard deviation. Created using Review Manager 5.4.1.

Sensitivity analyses, conducted by sequentially removing individual trials, demonstrated that effect sizes for several outcomes remained within acceptable ranges, with confidence intervals (CIs) consistently crossing the null effect value. This suggests a degree of robustness in the overall findings, indicating that the results were not unduly influenced by any single study. However, not all outcomes demonstrated such stability. Measures such as LDL levels, dietary factors, and quality of life exhibited notable fluctuations in effect sizes, warranting cautious interpretation of these specific results. Full details of the sensitivity analysis are presented in Supplementary Fig. S16.

Three trials explored user experiences with eHealth technologies. Due to variations in evaluation methods and the limited number of trials, we conducted a descriptive analysis for this section. Cruz-Cobo et al.20 found that the intervention group showed significantly improved adherence to a healthy diet (P < 0.001) and increased physical activity (P < 0.001). Participants also reported high satisfaction (42.53 ± 6.38), rating the application’s usability as excellent (>80.3 points), and described it as a promising and innovative tool. Similarly, Bernal-Jiménez et al.21 found that participants in the intervention group reported significantly greater satisfaction and app usability compared to those receiving standard care (P = 0.002). In the trial by Athilingam et al.22, users of the HeartMapp application gave high ratings for ease of use, content accuracy, user-friendly design, problem-solving features, and their confidence in using the app, demonstrating an overall high level of satisfaction.

Discussion

The increasing global burden of CVD and its associated risk factors underscores the urgent need for more effective risk communication strategies. eHealth technologies have emerged as promising tools, complementing traditional face-to-face education. This systematic review and meta-analysis examined the effectiveness of eHealth-based CVD risk communication across a broad range of health-related outcomes. While several positive effects were identified, overall findings were mixed, with certain outcomes showing limited or no improvement.

Significant benefits were identified in key clinical and behavioral outcomes, particularly SBP, LDL levels, physical activity, smoking cessation, disease awareness, and quality of life. The positive effects on SBP, cholesterol control and disease awareness are consistent with prior meta-analyses6,23,24, emphasizing the clinical relevance of eHealth-based risk communication in managing modifiable CVD risk factors. Notably, smoking cessation, often regarded as one of the most difficult behavioral changes, demonstrated significant improvement in the long-term follow-up subgroup. This finding aligns with previous meta-analyses reporting the efficacy of SMS- or app-based interventions in promoting both short-term (3 months) and long-term (6 months) smoking cessation25. Similarly, improvements in physical activity reinforce the potential of eHealth technologies in driving lifestyle modifications among at-risk populations. In contrast, the findings regarding physical activity and smoking cessation differ from those reported in another meta-analysis on CVD risk communication6. These discrepancies may be attributed to the current review’s specific focus on eHealth-based CVD risk communication, where participants were primarily drawn from populations with lifestyle-related CVD risk and risk communication was an essential intervention component in the included trials. By comparison, the previous meta-analysis included broader forms of risk communication and incorporated additional intervention components beyond risk communication itself.

However, not all outcomes demonstrated significant improvement. Mental health, diet, and medication adherence showed limited or inconsistent changes. For example, medication adherence improved in the primary prevention subgroup, while dietary behavior improved in the secondary prevention subgroup, likely due to differences in intervention intensity and personalization. Patients under secondary prevention are typically monitored more closely and receive more intensive medical management, including lipid-lowering therapies26,27. Despite the well-established evidence linking mental health and poor CVD outcomes8, our results found no significant improvement in mental health measures, possibly because eHealth-based risk communication interventions often focus on health information and rather than psychological support23. It must be emphasized that cognitive and affective responses are key determinants in initiating and sustaining health behavior change7. Therefore, risk communication strategies must carefully consider their psychological impact on patients. Poorly framed risk information, such as notifications that induce excessive anxiety or feelings of helplessness, may increase psychological distress28. This can ultimately counteract the potential benefits of the intervention and undermine long-term behavior maintenance.

As eHealth interventions become increasingly integrated into clinical practice, understanding user experiences is essential29,30. Several studies have explored the experiences or insights of patients and providers regarding CVD risk communication12,31,32,33. As noted in prior research, isolated risk assessments are often perceived as meaningless by patients, particularly when the results conflict with their subjective perceptions of their own health status12. This highlights the challenge faced by healthcare providers in translating quantified risk data into meaningful, patient-centered communication34,35. eHealth technologies should therefore serve not merely as information transmitters but as active enablers of risk communication, optimizing information presentation, adapting to individual cognitive profiles, and enhancing the precision and impact of clinician-patient interactions. Furthermore, while quantitative studies excel at documenting objective intervention outcomes, their findings risk becoming “information silos” without complementary exploration of underlying mechanisms. Future research could adopt mixed-methods designs that systematically integrate assessments of usability, accessibility, and acceptability of eHealth technologies with traditional measures of behavioral and clinical efficacy to better understand the mechanisms underpinning intervention effects.

Of the 23 included trials, most eHealth-based CVD risk communication interventions incorporated core elements such as risk assessment, risk presentation, personalized advice, dynamic tracking, and follow-up reminders. Given their multi-component nature, positive effects likely resulted from the combined impact of personalized risk communication and accompanying behavior change techniques, such as self-monitoring, action planning, and reminders. Some trials have used factorial designs to identify “active components” from multi-component interventions36,37,38, while optimizing intervention protocols is an iterative process requiring further research. Future research should use standardized frameworks, such as the behavior change techniques taxonomy39 and optimization strategies (e.g., factorial designs40, Multiphase Optimization Strategy41), to isolate active components and refine intervention protocols for maximal effectiveness.

This systematic review has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, this review, constrained by its inclusion and exclusion criteria, only reflects eHealth-based CVD risk communication. However, risk communication is multidimensional, requiring evaluation across psychological, social, and cultural contexts. The findings of this review should be interpreted in conjunction with other relevant reviews on CVD risk communication5,6,12,42. Secondly, there was substantial heterogeneity was observed across the trials. Although subgroup analyses were conducted based on different levels of prevention and follow-up duration, significant heterogeneity in outcomes remained. This heterogeneity could be partly explained by differences in eHealth technologies used, intervention providers, intervention time, variations in study populations and settings (Supplementary Table S2). The inclusion of diverse CVD populations with differing baseline characteristics likely contributed to further clinical and methodological heterogeneity. Finally, the relatively small number of eligible trials limited the ability to assess publication bias. Specifically, the number of trials per outcome was insufficient to apply funnel plots or the Egger’s regression asymmetry test with confidence. As a result, the presence of potential publication bias cannot be ruled out.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplementary Table S3)43. The protocol has been registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024582906).

Seven electronic databases, including PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, EBSCOhost-MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO, were searched from inception to 1st October 2024. The search strategy was developed through initial discussions among some of the authors, and in consultation with an academic experienced in evidence-based nursing methods (JNY). Search terms included: “cardiovascular diseases,” “heart disease,” “hypertension,” “heart failure,” “stroke,” “arteriosclerosis,” “electronic health,” “eHealth,” “mobile health,” “telehealth,” “digital health,” “app,” “internet,” “website,” “web,” “phone,” “email,” “SMS,” “MMS,” “electronic health record,” “risk communication,” “risk assessment,” “risk score,” “risk representations,” “risk information/risk management,” “heart age,” “absolute risk,” “relative risk,” and “counseling”. Additionally, reference lists of included trials were manually searched, and authors of eligible trials were contacted to obtain further data. The complete search strategy is detailed in Supplementary Table S4.

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (a) Population: individuals aged ≥ 18 years with (secondary prevention) or without (primary prevention) established CVD, specifically this review was focused on the types of CVD events that have a high incidence and are closely related to healthy lifestyles, such as coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke; (b) Intervention: presenting risk score or the risk of CVD events, using eHealth technologies (e.g., web-based browsers, computers, smartphones, and electronic health records) for risk communication; (c) Comparison: blank control, usual care, or an alternate intervention not delivered via eHealth; (d) Outcome: changes in CVD health-related indicators (e.g., physiological health metrics, lifestyles, mental health); (e) Study design: randomized controlled trials; (f) Language: English. Conference abstracts, letters to the editor, and study protocols that lacked adequate data were excluded.

References identified from the databases were imported into EndNote X9.1 for management. Following the removal of duplicates, two independent reviewers (YJJ and BLL) performed an initial screening based on titles and abstracts, applying predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. A secondary screening of full-text articles followed. Disagreements arising during the screening process were resolved by consensus, with a third researcher (YJQ) consulted as necessary. Two reviewers (YJJ and BLL) independently extracted data by using a custom-designed data extraction form, which captured information, such as first author, publication year, country, groups, levels of prevention44, sample characteristics, eHealth technologies, intervention components, outcomes, and quantitative results. Three researchers (YJJ, BLL, and YJQ) independently evaluated the quality of the included RCTs in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 5.1.0)45. Discrepancies in quality assessment were addressed through consultation with a fourth researcher (QSZ).

Prior to formal data analysis, raw data extracted from the included studies were subjected to transformation. For example, when studies provided sample size alongside standard error (SE) or 95% confidence interval (CI), these values were converted to standard deviation (SD). Additionally, data from multiple subgroups were consolidated as part of this preprocessing. Review Manager 5.4.1 was used to analyze the extracted data46. In cases where measurement approaches for the indicators were inconsistent, data standardization was performed. For continuous data, the standard mean difference (SMD) with 95%CI was selected over the mean difference (MD), as SMD offers better generalizability and external applicability, making it more suitable for comparison across similar populations and less susceptible to over-or underestimation47. Dichotomous data were reported using odds ratios (OR) and CI. Heterogeneity among the included studies was assessed with I2 statistics, with substantial heterogeneity suggested where I2 is ≥50%. Considering potential heterogeneity between studies, a random-effects model was used to generate more robust results48. A p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant for meta-analyses. To enhance data availability and align with the characteristics of the studies, subgroup analyses were performed based on levels of prevention (e.g., primary prevention, secondary prevention, and both) and follow-up time (e.g., short-term ≤ 3 months vs. long-term > 3 months) to explore heterogeneity and compare effects across different subgroups. Sensitivity analysis was conducted using the leave-one-study-out method to evaluate the robustness and reliability of the pooled results49.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Vaduganathan, M., Mensah, G. A., Turco, J. V., Fuster, V. & Roth, G. A. The global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk: a compass for future health. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 80, 2361–2371 (2022).

World Health Organization. Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control (World Health Organization, 2011)

Xuan, F. & Wang, Z. Interpretation of the primary prevention guideline for cardiovascular diseases in China. Clin. J. Med. 50, 551–553 (2022).

World Health Organization. Risk Communication. https://www.who.int/emergencies/risk-communications (2024).

Chia, A. W., Teo, W. L., Acharyya, S., Munro, Y. L. & Dalan, R. Patient-physician communication of health and risk information in the management of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med. 23, 96 (2025).

Bakhit, M. et al. Cardiovascular disease risk communication and prevention: a meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 45, 998–1013 (2024).

Sharma, M. Multi-theory model (MTM) for health behavior change. WebmedCentral 6, WMC004982 (2015).

Civieri, G. et al. Anxiety and depression associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk through accelerated development of risk factors. JACC Adv. 3, 101208 (2024).

Bonner, C. et al. Interventions using heart age for cardiovascular disease risk communication: systematic review of psychological, behavioral, and clinical effects. JMIR Cardio 5, e31056 (2021).

Waldron, C. A., van der Weijden, T., Ludt, S., Gallacher, J. & Elwyn, G. What are effective strategies to communicate cardiovascular risk information to patients? a systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 82, 169–181 (2011).

Schulberg, S. D. et al. Cardiovascular risk communication strategies in primary prevention. A systematic review with narrative synthesis. J. Adv. Nurs. 78, 3116–3140 (2022).

Lorenc, T., Stokes, G., Fulbright, H., Sutcliffe, K. & Sowden, A. Communicating cardiovascular risk: systematic review of qualitative evidence. Patient Educ. Couns. 123, 108231 (2024).

Griffiths, S., McMillan, B., Bartlett, Y. K. & French, D. Cardiovascular disease risk communication alone is not enough: why a recent review may be misleading. Eur. Heart J. 45, 4239–4240 (2024).

Khan, S. U., Ali, A. K. & Nasir, K. The art of deciphering and communicating cardiovascular risk: getting it right. Eur. Heart J. 45, 1014–1016 (2024).

World Health Organization. eHealth. https://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/ehealth/ (2024).

Campbell, M., McEvoy, J. W., Calpin, G., Concannon, F. & Redfern, S. Perspectives of healthcare professionals on clinician-patient communication of cardiovascular disease risk. J. Patient Exp. 11, 23743735241257386 (2024).

Miao, Y. et al. Effectiveness of eHealth Interventions in improving medication adherence among patients with cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e58013 (2024).

Su, J. J., Lin, R., Batalik, L., Wong, A. K. C. & Grace, S. L. Psychological ehealth interventions for patients with cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 27, e57368 (2025).

Sterne, J. A. et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 343, d4002 (2011).

Cruz-Cobo, C. et al. Efficacy of a Mobile health app (eMOTIVA) regarding compliance with cardiac rehabilitation guidelines in patients with coronary artery disease: randomized controlled clinical trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 12, e55421 (2024).

Bernal-Jiménez, M. et al. Effectiveness of an interactive mhealth app (evite) in improving lifestyle after a coronary event: randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 12, e48756 (2024).

Athilingam, P., Jenkins, B., Johansson, M. & Labrador, M. A mobile health intervention to improve self-care in patients with heart failure: pilot randomized control trial. JMIR Cardio 1, e3 (2017).

Megat Kamaruddin, P. S. N., Mohammed Nawi, A., Abdul Manaf, M. R., Yaman, M. N. & Abd Malek, A. M. A Meta-analysis of ehealth interventions on ischaemic heart disease health outcomes. Glob. Heart 18, 12 (2023).

Su, J. J. et al. Long-term effects of e-health secondary prevention on cardiovascular health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 22, 562–574 (2023).

Fang, Y. E. et al. Effectiveness of ehealth smoking cessation interventions: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e45111 (2023).

Lee, Z. V. & Lam, H. Aggressive lipid-lowering therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention—for whom and how?: aggressive lipid-lowering therapy after PCI. AsiaInterv 8, 24–31 (2022).

Karunathilake, S. P. & Ganegoda, G. U. Secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases and application of technology for early diagnosis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 5767864 (2018).

Liu, K. & Chen, M. Disentangling the effects of cognitive, affective, and sociocultural factors on risk information avoidance: a meta-analysis. Commun. Res. 00, 1–35 (2024).

Wang, T., Giunti, G., Melles, M. & Goossens, R. Digital patient experience: umbrella systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 24, e37952 (2022).

Chute, C., French, T., Raman, S. & Bradley, J. User requirements for comanaged digital health and care: review. J. Med. Internet Res. 24, e35337 (2022).

Bonner, C. et al. Experiences of a national web-based heart age calculator for cardiovascular disease prevention: user characteristics, heart age results, and behavior change survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e19028 (2020).

Hawking, M. K. D., Timmis, A., Wilkins, F., Potter, J. L. & Robson, J. Improving cardiovascular disease risk communication in NHS health checks: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 9, e026058 (2019).

Jensen, A. E., Søndergaard, J., Kjær, N. K. & Nielsen, J. B. Patients’ views on usefulness and effects of a risk communication tool for cardiovascular disease: a qualitative analysis. BMC Prim. Care. 25, 50 (2024).

Kwame, A. & Petrucka, P. M. A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: barriers, facilitators, and the way forward. BMC Nurs. 20, 158 (2021).

Drossman, D. A. & Ruddy, J. Improving patient-provider relationships to improve health care. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 1417–1426 (2020).

Bonner, C. et al. The impact of health literacy-sensitive design and heart age in a cardiovascular disease prevention decision aid: randomized controlled trial and end-user testing. JMIR Cardio 6, e34142 (2022).

Muscat, D. M. et al. Benefits and harms of hypertension and high-normal labels: a randomized experiment. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 14, e007160 (2021).

Hovick, S. R., Wilkinson, A. V., Ashida, S., de Heer, H. D. & Koehly, L. M. The impact of personalized risk feedback on Mexican Americans’ perceived risk for heart disease and diabetes. Health Educ. Res. 29, 222–234 (2014).

Kapukotuwa, S., Nerida, T., Batra, K. & Sharma, M. Utilization of the multi-theory model (MTM) of health behavior change to explain health behaviors: a systematic review. Health Promot. Perspect. 14, 121–135 (2024).

Bangdiwala, S. I. Factorial experimental designs. Int. J. Inj. Contr. Saf. Promot. 23, 110–111 (2016).

Collins, L. M., Murphy, S. A. & Strecher, V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): new methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 32, S112–S118 (2007).

Sebastian, S. A. Cardiovascular disease risk communication: strategies, impact, and future directions. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 49, 102490 (2024).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 134, 178–189 (2021).

Institute for Work & Health. Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Prevention. https://www.iwh.on.ca/what-researchers-mean-by/primary-secondary-and-tertiary-prevention (2015).

Cochrane Training. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (2024).

Cochrane Collaboration. RevMan: systematic review and meta-analysis tool for researchers worldwide. https://revman.cochrane.org/info (2024).

Takeshima, N. et al. Which is more generalizable, powerful and interpretable in meta-analyses, mean difference or standardized mean difference?. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 14, 30 (2014).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. & Rothstein, H. R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 1, 97–111 (2010).

Higgins J. P. T. et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, Version 6.5. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (2024).

Persell, S. D. et al. Individualized risk communication and outreach for primary cardiovascular disease prevention in community health centers randomized trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 8, 560–566 (2015).

Persell, S. D., Lloyd-Jones, D. M., Friesema, E. M., Cooper, A. J. & Baker, D. W. Electronic health record-based patient identification and individualized mailed outreach for primary cardiovascular disease prevention: a cluster randomized trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 28, 554–560 (2013).

Sheridan, S. L., Shadle, J., Simpson, R. J. Jr & Pignone, M. P. The impact of a decision aid about heart disease prevention on patients’ discussions with their doctor and their plans for prevention: a pilot randomized trial. BMC Health Serv. Res 6, 121 (2006).

Sheridan, S. L. et al. A randomized trial of an intervention to improve use and adherence to effective coronary heart disease prevention strategies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 11, 331 (2011).

Ruffin, M. T. et al. Effect of preventive messages tailored to family history on health behaviors: the family healthware impact trial. Ann. Fam. Med. 9, 3–11 (2011).

Silarova, B. et al. Effect of communicating phenotypic and genetic risk of coronary heart disease alongside web-based lifestyle advice: the INFORM Randomised Controlled Trial. Heart 105, 982–989 (2019).

Soureti, A., Murray, P., Cobain, M., van Mechelen, W. & Hurling, R. Web-based risk communication and planning in an obese population: exploratory study. J. Med. Internet Res. 13, e100 (2011).

Sarfo, F. S. et al. Effect of an Educational intervention for primary stroke risk reduction in ghana and nigeria: pilot randomized controlled trial. Stroke 54, 1660–1664 (2023).

Lee, T. J., Cameron, L. D., Wünsche, B. & Stevens, C. A randomized trial of computer-based communications using imagery and text information to alter representations of heart disease risk and motivate protective behaviour. Br. J. Health Psychol. 16, 72–91 (2011).

Beratarrechea, A. et al. Using mhealth tools to improve access and coverage of people with public health insurance and high cardiovascular disease risk in Argentina: a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e011799 (2019).

Hussin, R. et al. Stroke riskometer application (SRA™) influence on lifestyle changes of home bound familial Malaysian stroke caregivers: a randomised controlled trial in a primary care based longer term stroke care facility. BMC Prim. Care 24, 181 (2023).

Jaspers, N. E. M. et al. Communicating personalised statin therapy-effects as 10-year CVD-risk or CVD-free life-expectancy: does it improve decisional conflict? Three-armed, blinded, randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 11, e041673 (2021).

Greving, J. P. et al. Cost-effectiveness of a nurse-led internet-based vascular risk factor management programme: economic evaluation alongside a randomised controlled clinical trial. BMJ Open 5, e007128 (2015).

Vernooij, J. W. et al. Internet based vascular risk factor management for patients with clinically manifest vascular disease: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 344, e3750 (2012).

Guo, Y. et al. Mobile health technology for atrial fibrillation management integrating decision support, education, and patient involvement: mAF app trial. Am. J. Med. 130, 1388–1396.e1386 (2017).

Su, J. J. et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of cardiac telerehabilitation for older adults with coronary heart disease: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 42, 101365 (2024).

Mirshahi, A. et al. The impact of an integrated early palliative care telehealth intervention on the quality of life of heart failure patients: a randomized controlled feasibility study. BMC Palliat. Care 23, 22 (2024).

Achury-Saldaña, D. M., Gonzalez, R. A., Garcia, A., Mariño, A. & Bohorquez, W. R. Efficacy of a telemonitoring system as a complementary strategy in the treatment of patients with heart failure: randomized clinical trial. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 42, 522–529 (2024).

Redfern, J. et al. A digital health intervention for cardiovascular disease management in primary care (CONNECT) randomized controlled trial. NPJ Digit. Med. 3, 117 (2020).

Nolan, R. P. et al. Therapeutic benefit of preventive telehealth counseling in the community outreach heart health and risk reduction trial. Am. J. Cardiol. 107, 690–696 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to statistician Professor Zhiguang Ping for his assistance and support in the data analysis; and to Jingna Yi for her help in modifying the search strategy. The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China to B.L. (grant number 72104221), National Natural Science Foundation of China to M.Y. (grant number 72304005), Research Projects of Colleges and Universities in Henan Province (grant number 25A320027) and Henan Province Higher Education Institutions Young Key Teacher Program (grant number 2024GGJS013) to B.L.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.J. contributed to Writing the Original Draft, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, and Visualization. Y.Q. was involved in Writing—Review and Editing and Data Curation. Q.Z. contributed to Methodology, Writing—Review and Editing, and Data Curation. L.P.A. participated in Writing—Review and Editing. K.B. was involved in Writing—Review and Editing. Z.G. contributed to Writing—Review and Editing. M.T.O. participated in Writing—Review and Editing. M.Y. was involved in Writing—Review and Editing and Funding acquisition. D.A.C. contributed to Methodology and Writing—Review and Editing. B.L. was responsible for Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Supervision, Writing the Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing, Project Administration, and Funding Acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, Y., Qiu, Y., Zhang, Q. et al. The effectiveness of eHealth-based cardiovascular disease risk communication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. npj Digit. Med. 9, 33 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02205-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02205-w