Abstract

In clinical practice, MRI images are widely used to diagnose neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, complex MRI patterns often mimic normal aging, relying on subjective experience and risking misdiagnosis. This paper proposes the Cross Vision Transformer with Coordinate (CVTC) to assess AD severity and accurately annotate suspicious lesions, reducing clinicians’ burden and improving reliability. CVTC integrates scale-adaptive embedding, dynamic position bias, and long-short attention mechanisms to enhance capture of local and global MRI features. For annotation, the Coordinate and Feature Map Guided Mechanism (CAGM) leverages pixel coordinates and feature maps to compute an importance threshold, generating lesion overlay maps for precise localization. A user-friendly UI is developed to enable intuitive exploration and validation in clinical settings. CVTC demonstrates robust performance across datasets: 98.80% accuracy on ADNI (AD/MCI/CN), 98.51% on AD subtypes (EMCI/LMCI/SMC/CN); cross-dataset validation on tumor and multiple sclerosis MRIs confirms CAGM’s annotation accuracy; NACC (96.30%), OASIS-1 (98.16%), and pseudo-RGB datasets (92.96%) highlight superior generalization. Ablation and cross-validation affirm robustness. With a 21.850MB lightweight design, CVTC offers an efficient, accurate tool for diverse clinical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that primarily affects the cognitive abilities, memory, and daily living skills of older adults. With the aging of the global population, the prevalence of AD has significantly increased, becoming a major public health issue. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are currently ~50 million AD patients worldwide, with ~10 million new cases each year. This disease not only severely impacts the quality of life of patients but also imposes substantial economic and psychological burdens on families and society.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is widely used as a non-invasive diagnostic tool in the diagnosis of AD. MRI provides detailed information about brain structures, but interpreting these images still faces significant challenges. Structural changes related to AD are often subtle and can easily be confused with normal aging processes. The diagnostic results heavily depend on the subjective judgment of clinicians, which can lead to inconsistencies. This situation highlights the necessity for developing automated, precise analysis tools.

Machine learning methods such as support vector machines (SVM) and random forests (RF)1 have achieved notable success in the classification analysis of MRI images of AD. For example, SVM constructs hyperplanes in high-dimensional space to achieve high classification accuracy, reaching up to 98% in some studies on MRI datasets2,3,4Random Forests utilize ensemble learning to handle high-dimensional nonlinear data, achieving a maximum classification accuracy of 99.25%5. However, these traditional methods have limitations when dealing with large-scale data and complex imaging features.

In recent years, deep learning has shown tremendous potential in the field of medical image analysis. With the development of artificial intelligence technology, the application of deep learning in medical image analysis has made significant progress6, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which have multi-level feature extraction capabilities to automatically capture complex spatial relationships and features from large datasets. Notably, researchers like Shangran Qiu et al. proposed an MRI-only fusion model that integrates MRI data with non-imaging data, enhancing diagnostic performance through multimodal data fusion7. Morteza Ghahremani et al. introduced the DiaMond framework, combining Transformers with multimodal normalization techniques to reduce redundant dependencies8. Muhammad Umair Ali et al. improved classification performance using CCA-based fusion features, achieving9 significant advancements in diagnostic accuracy. Ahmed et al. achieved accuracies of 99.22% for healthy individuals and 95.93% for Alzheimer’s patients, demonstrating the effectiveness of deep learning approaches10. While these various deep learning architectures have achieved promising results, challenges remain in terms of model complexity, training time, high classification performance, and model interpretability. To address these issues, our study proposes an innovative deep learning-based approach aimed at further improving the performance of Alzheimer’s disease MRI image analysis. Our main contributions are as follows:

-

We used an efficient variant of the Unet model, LinkNet, and modified its 2D architecture to a 3D architecture. The improved LinkNet3D model can more accurately separate brain regions while reducing overall computational load.

-

A new image enhancement method, MBIE, effectively improves image contrast and detail through multi-channel processing, enhances specific features while preserving important characteristics, and significantly increases model generalization ability.

-

We used a long-short attention mechanism and scale-adaptive embedding combined with dynamic position bias (DPB). After testing, this method performed particularly well in medical image processing, especially high-resolution and contrast-enhanced MRI images. Cross-validation and ablation studies showed that the model achieved high accuracy on multiple test datasets and had strong generalization and robustness.

-

The proposed CAGM (Coordinate and Feature Map Guided Mechanism) orchestrates dynamic coordinate tracking with multi-scale feature representations derived from a hierarchical attention architecture, enabling precise localization and semantic characterization of suspicious lesion regions, thus providing clinicians with robust spatial-semantic insights and markedly enhancing the model’s interpretive reasoning prowess.

Results

LinkNet3d can effectively achieve skull separation

The Dice coefficient of LinkNet3d is 0.9715, indicating a 97.15% overlap between the predicted mask and the ground truth mask. Intersection over Union (IoU) is a metric used to evaluate the accuracy of an object detector on a particular dataset. In this case, the IoU is 0.9446, indicating that the intersection over union of the predicted and ground truth masks is 94.46%. The separation effect is shown in Fig. 1, where the separated skull region is clear and well-defined, highly consistent with the original image. LinkNet3d optimizes the layer as a heatmap, which, when overlaid with the original image, helps users intuitively understand the model’s focus areas. To enhance computational efficiency, LinkNet3d employs VFM (Variable Feature Map) links between the encoder and decoder blocks, significantly reducing the number of parameters in the network. Compared to the traditional U-Net model, which has 2,673,795 parameters, LinkNet3d has only 2,126,258 parameters, a reduction of ~20.4%. This lightweight design not only lowers memory usage but also accelerates inference speed, making it highly suitable for resource-constrained environments. The model was evaluated on an NVIDIA RTX 3060 GPU with 12GB of VRAM, demonstrating its efficiency and practicality for deployment on mid-range hardware. The main purpose of the LinkNet3d model is to provide high-quality input images for subsequent model training. By effectively separating the skull region, we ensure that downstream models can be trained on cleaner and more accurate images, thereby improving the overall performance and reliability of the diagnostic system.

CVTC enhances the assessment of all stages of Alzheimer’s disease and provides precise annotation capabilities

On the ADNI-General dataset (MCI, CN, AD), the test set retention results showed an accuracy of 98.80%, precision of 98.76%, F1-Score of 99.88%, and recall of 99.82%. On the ADNI Subtype dataset (EMCI, LMCI, Health, SMC), the accuracy was 98.51%, precision 98.89%, F1-Score 99.70%, and recall 99.83%. On the OASIS-1 dataset (CDR: 0, 0.5, 1, 2), the results were: accuracy 98.16%, precision 99.16%, F1-Score 98.85%, and recall 98.54%. Additionally, across independent Kaggle datasets and pseudo-RGB-enhanced data, the average metrics were as follows: accuracy of 96.15%, precision 96.38%, F1-Score 96.22%, and recall 96.24%. The NACC dataset is as follows: accuracy of 96.30%, precision of 95.13%, F1 score of 91.41%, and recall of 90.04%. These metrics are presented in Table 1. Additionally, the model has a total parameter count of 4.66 M, with an average inference time per batch of 0.0280 seconds (batch size = 4), resulting in an average inference time per sample of 0.007012 seconds. This low latency makes it suitable for mobile devices. The model’s throughput is 142.61 samples per second, with a peak GPU memory usage of 234.20 MB, indicating low memory consumption suitable for edge computing. The average GPU utilization is 36.19% (on a 4090 laptop), reflecting moderate utilization without overload. These metrics demonstrate the model’s lightweight nature.

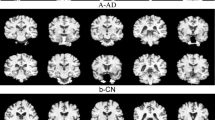

Regarding the lesion annotation function, the annotated images of CAGM are shown in Fig. 2. To verify the annotation accuracy of CAGM, we proposed three methods: multidimensional statistical analysis, heatmap validation (VFM), and atlas matching validation (AMV). Tumors and multiple sclerosis were introduced as additional independent datasets to validate the accuracy of the annotations.

a Non-demented unannotated control group. b1, b2 Very mild dementia, original and annotated images. c1, c2 Mild dementia original and annotated images. d Moderate dementia original and annotated images, e NondDem, f mild cognitive impairment, g Alzheimer’s disease, h early mild cognitive impairment, m late mild cognitive impairment, n Significant memory concern.

Feasibility of CAGM annotation and clinical applicability

Multidimensional statistical analysis

Through a comprehensive analysis of the scoring results of multiple images, we evaluated the performance of our proposed model in medical imaging annotation tasks using a multi-metric evaluation framework combined with statistical methods. Our results indicate that 87.5% of images achieved a composite score within the 75–95 range (mean = 85.74, standard deviation ≈ 5.47), demonstrating the high consistency of our model in generating reliable annotations. We observed excellent performance in key metrics, including grayscale mean difference (mean = 37.07), connectivity score (mean = 0.87), and Wasserstein distance (mean = 44.59), highlighting the model’s capability in producing high-contrast, structurally continuous, and well-aligned annotations. Statistical analysis validated the model’s effectiveness, with all image p values < 0.05, confirming significant grayscale differences between annotated and non-annotated regions. The grayscale mean difference underscores our model’s ability to clearly delineate annotated areas, enhancing its value in clinical interpretation. Likewise, the connectivity score showcases the model’s advantage in maintaining coherent annotations, making it particularly suitable for anatomical applications such as brain lesion detection. The Bhattacharyya distance (mean = 0.34) further confirms the high similarity between our annotations and the true distribution, supporting the accuracy of the segmentation. Regarding the proportion of pixels in annotated regions (mean = 1.43%), we designed the model to prioritize focused annotations, which are especially beneficial for high-precision tasks; however, we also note that increasing coverage in certain scenarios may further improve performance. The Wasserstein distance shows minor spatial distribution differences, but our model’s overall alignment remains robust. These findings collectively demonstrate that our model is a reliable tool for medical imaging tasks, providing a solid foundation for clinical applications.

Clinician validation and Brain Atlas validation

To quantitatively evaluate the interpretability and annotation accuracy of CAGM, we utilized BrainSuite software to perform brain segmentation on MRI images. Subsequently, the lesion annotations generated by CAGM were compared with those of the segmented images. The Brain Atlas validation comparison chart is shown in Fig. 3. Our evaluation indicates that CAGM annotations are perfectly distributed in brain regions vulnerable to AD, such as the hippocampus and amygdala, aligning seamlessly with anatomical structures. Furthermore, the overlap rate of CAGM annotation regions with standard brain atlases reaches 83.21%. Compared to manual annotations by expert clinicians from 10 patients (Fig. 4), the overall Dice Similarity Coefficient (ODS) achieves 83.6%, calculated using the following formula:

Where, \({\text{DSC}}_{i}=\frac{2\times |{A}_{i}\cap {B}_{i}|}{|{A}_{i}|+|{B}_{i}|}\), represents the Dice Similarity Coefficient for the i-th region, \(|{A}_{i}\cap {B}_{i}|\) is the number of intersecting slices between CAGM annotations and clinician annotations, \(|{A}_{i}|\) is the number of slices in CAGM annotations, \(|{B}_{i}|\) is the number of slices in clinician annotations, and N is the total number of brain regions. These metrics provide strong evidence for CAGM’s effectiveness in localizing suspicious lesions and enhancing clinical reliability.

Presents a comparative example of manual annotations by clinicians and automatic annotations generated by CAGM, highlighting key brain anatomical structures (regions of atrophy or abnormal enlargement) as follows: 1 is R. cingulate gyrus, 2 is L. cingulate gyrus, 3 is R. superior parietal gyrus, 4 is R. pre-cuneus, 5 is L. pre-cuneus, 6 is L. cingulate gyrus, 7 is R. lateral ventricle, 8 is third ventricle, 9 is R. transverse temporal, 10 is R. superior temporal gyrus, 11 is L. superior temporal gyrus, 12 is Bilateral Hippocampus, 13 is R. parahippocampal gyrus, and 14 is L. parahippocampal gyrus. This comparison enables a visual evaluation of the consistency and potential discrepancies in CAGM annotations across cortical and subcortical structures, serving as a reference for subsequent quantitative analysis.

Validation on additional datasets

To validate the feasibility of CAGM annotation, we introduced two independent additional datasets of multiple sclerosis (MS) and brain tumor (TS) for evaluation. The annotation results (Fig. 5) showed that for MS, the average Dice coefficient of the annotated regions was 0.8827 and the average IoU was 0.7901; for TS, the average Dice coefficient was 0.8289, and the average IoU was 0.7104. These results indicate that CAGM demonstrates good annotation consistency and accuracy across different disease datasets, providing reliable support for its clinical application.

AMV verifies the accuracy of annotated regions

We consecutively annotated the complete MRI scans of several individuals, one of whom is shown in Fig. 6, and used FreeSurfer to segment brain structures. This allowed us to compare them with standard anatomical atlases and determine whether key regions were annotated.

-

In the upper-layer MRI of this patient, our annotations focus on the medial temporal lobe structures and parts of the temporal cortex, which are commonly affected regions in AD pathology. Annotations also appear around the ventricles (dark areas), as ventricular enlargement is an indirect manifestation caused by brain tissue atrophy in AD patients11.

-

In the upper-middle-layer MRI, blue annotation regions cover the hippocampus and medial temporal lobe structures, and also involve the lateral ventricles (dark areas). Due to brain tissue atrophy, ventricular enlargement often occurs in AD patients. Upper-middle images begin to show the frontal and parietal regions, and annotations also cover these cortical areas. In mid-to-late-stage AD, frontal and parietal atrophy becomes more evident, affecting executive functions and spatial cognition12.

-

In the middle-layer MRI, yellow-highlighted regions are located in the medial temporal lobe near the brain’s midline, where the hippocampus lies. Extensive blue annotations are present in both temporal lobes, regions commonly affected in AD. Additionally, some blue regions near the top involve the parietal and frontal lobes but are less distributed 13.

-

In the lower-middle-layer MRI, yellow-highlighted regions remain in the medial temporal lobe, especially the hippocampus. Blue annotations are visible in both temporal lobes, covering parts of the inferior and middle temporal gyri. Annotations near the midline involve white matter regions around the ventricles, often associated with white matter lesions.

-

In the lower-layer MRI, annotations are concentrated in middle-lower areas (bilaterally symmetrical, near the ventricles), key regions commonly affected in AD patients. Annotations are also present in the temporal lobes on both sides, particularly the medial temporal lobe. Regions around the central ventricles and upper image areas (frontal lobe) are also annotated, which is commonly seen in AD patients 14.

In summary, our annotations accurately covered key brain regions commonly affected in AD patients, including the medial temporal lobe, hippocampus, temporal cortex, and regions around the ventricles. These annotations closely align with AD pathological characteristics, such as brain tissue atrophy and ventricular enlargement. They not only correspond to standard anatomical atlases but also reliably reflect AD-related features, providing a robust foundation for subsequent pathological analysis and diagnosis. Our annotation results are highly consistent with those of Qiu et al.7.

VFM extracts attention-focused regions

In the analysis of MRI images of AD patients, the thalamus, frontal lobes, and temporal lobes are key regions of interest. Typically, significant pathological changes are observed in these areas in AD patients15,16,17. The CVTC attention mechanism enables detailed analysis of MRI images, identifying structural abnormalities and changes in various brain regions, thereby accurately detecting atrophy and morphological changes16,17.

VFM can accurately obtain and visualize attention weights from specific layers in a Transformer model. Analysis of the first layer’s attention heatmap (Fig. 7a) shows focus on brain regions like the thalamus, fornix, basal ganglia, lateral globus pallidus, and superior temporal sulcus, which are crucial for sensory information processing. In AD patients, these areas often atrophy, affecting their functions. The fornix connects the hippocampus with other brain regions and is involved in memory formation, while the basal ganglia play a role in motor control and cognitive functions. The hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus are important for memory and learning, and the lateral globus pallidus is involved in motor and cognitive functions. Changes in these areas in AD patients may relate to motor disorders and cognitive decline18,19,20,21,22. The superior temporal sulcus shows significant cortical thickness reduction in AD, leading to cortical atrophy16,17,21. The second layer’s heatmap (Fig. 7b) highlights the fornix, cingulate, frontal, occipital, and temporal lobes, and lateral ventricles, all showing significant lesions in and the frontal lobe is key for executive functions and decision-making. The occipital cortex’s degeneration affects visual processing, while the temporal lobe’s atrophy is linked to memory and language decline. The lateral ventricles’ expansion reflects brain tissue degeneration in AD22. By analyzing these attention heatmaps, we can verify the model’s focus on key areas in AD patients, supporting early detection and diagnosis. In the last attention of each layer, the Attention Intensity value is close to 1. This indicates that in the last attention of each layer, the model’s attention is almost evenly distributed across the entire image, with the model giving close attention to all areas.

Cross-validation

To assess the robustness and generalization ability of our proposed model, we performed five-fold cross-validation on three datasets: ADNI (AD-CN-MCI), OASIS (four-class classification), and ADNI (E&LMCI). The performance metrics, including average accuracy, recall, F1-score, specificity, and precision for each classification category, were computed and are summarized in Table 2, illustrating the model’s effectiveness across various cognitive impairment stages.

CVTC ablation experiments

We conducted a series of ablation experiments (Table 3.) on CVTC to understand the impact of various components on the model’s performance. These experiments included:

Replacing the multi-scale convolution embedding layer

We substituted the multi-scale convolution embedding layer with a standard convolution layer to evaluate how the absence of multi-scale features affects the model’s ability to capture complex patterns. This change resulted in a decrease in accuracy from 96.32% to 94.38%.

Removing DPB

DPBs play a crucial role in enhancing the model’s spatial awareness. By removing this component, we aimed to observe the degradation in performance and understand its significance. The accuracy dropped from 96.32% to 93.92%.

Using only short-range attention

Attention mechanisms are pivotal in capturing dependencies across different parts of the input. We experimented with using only short-range attention to see how the model performs when it focuses solely on local features. This configuration led to an accuracy of 95.47%.

Using only long-range attention

Conversely, we also tested the model with only long-range attention to determine its effectiveness in capturing global context while potentially missing out on finer details. The accuracy in this setup was 90.78%.

Reducing or increasing model depth

When the model depth was reduced to one layer, the accuracy was 94.53%. This reduction decreased computational complexity and memory requirements, speeding up training and inference, but the rate of accuracy improvement slowed. Increasing the depth to 3 layers resulted in an accuracy drop to 91.10%, with significantly slower training and inference speeds, and a tendency to overfit on small datasets. For the datasets used in this paper, a depth of 2 helps balance computational efficiency and model performance.

Gradually adding noise to images

To evaluate the model’s generalization ability, we incrementally introduced noise into the test images from the Alzheimer's Dataset. At 10% noise, the model achieved an accuracy of 99.61%. As noise intensity increased to 15%, 20%, and 25%, accuracies were 99.48%, 99.23%, and 99.03%, respectively. At 30% and 35% noise, accuracies dropped to 98.39% and 96.88%. Higher noise levels of 40%, 45%, and 50% resulted in accuracies of 92.48%, 76.33%, and 49.16%. At extreme noise levels of 55%, 60%, 65%, and 70%, accuracies were 29.47%, 18.03%, 9.61%, and 3.48%, respectively. These results are illustrated in Fig. 823,24. See Table 4 for details.

Subgroup sensitivity analysis

To quantify potential biases in the dataset, we conducted a subset sensitivity analysis. Based on the ADNI dataset’s age distribution (mean 75.2 years, SD 7.8 years), the =70 years subset had an accuracy of 99.20%. Similarly, based on racial distribution (92% White, 8% non-White), the non-White subset had an accuracy of 98.00% (a 0.8% decrease), while the White subset had 98.87%. These small decreases suggest insignificant bias, mitigated by MBIE enhancement and multi-dataset training. Weighted averaging confirms consistency with the overall results.

Discussion

This study proposes the cross-vision transformer with coordinate (CVTC), a novel lightweight diagnostic and annotation method for analyzing Alzheimer’s disease MRI images and annotating lesion areas. CVTC achieves efficient capture of local details and global features in MRI images by combining cross-scale embedding mechanisms, dynamic positional bias techniques, and long-short attention mechanisms. Experimental results show that CVTC significantly outperforms current state-of-the-art methods on multiple public datasets (Kaggle, OASIS-1, ADNI and extended datasets), demonstrating excellent diagnosis accuracy and generalization ability.

Compared to existing models (Table 5), CVTC shows significant advantages in diagnosis performance. On the Kaggle dataset, CVTC achieves a diagnosis accuracy of 99.61%, significantly better than Inception-ResNet (91.43%)25,26 and CNN (92.5%)27. On the OASIS-1 dataset, the proposed method achieves an accuracy of 98.16%, outperforming Inception-ResNet (92%)25, CNN and SVM (88.84%)28, LSTM (91.8%)29, CNN (92.5%)27, and LGBM (91.95%)27. On the ADNI dataset, CVTC attains an accuracy of 98.50%, competitive with CNNs (99%)27 and LGBM (99.63%)27, and surpassing CNN (90.5%)29 and LSTM (89.8%)29, further demonstrating its robustness across diverse datasets. Additionally, CVTC’s test accuracy on generated data is 92.96% (pseudo-RGB synthetic data), highlighting its superiority in handling complex scenarios and cross-dataset adaptability. With a storage size of 21.850 MB, CVTC achieves significant performance improvements, making it feasible for use in resource-constrained medical settings.

In terms of interpretability, CVTC enhances diagnostic transparency through the Coordinate and Feature Map Guided Mechanism (CAGM) technique. The lesion annotation maps generated by CAGM provide critical diagnostic references for clinicians, significantly accelerating the decision-making process and offering new tools for studying disease mechanisms. Further experiments show that CVTC can precisely annotate key lesion areas related to Alzheimer’s disease, such as the hippocampus, parietal lobe, and temporal lobe, with high consistency between the identified areas and anatomical and pathological features. This characteristic gives CVTC unique value in assisting diagnosis and disease research.

CVTC has a wide range of potential applications. By optimizing computational complexity, it can be deployed on edge computing devices or mobile applications, providing efficient diagnostic support for resource-limited areas. It can also be combined with other modality data (such as PET scans and genomic information) to develop a multimodal diagnostic framework, further enhancing diagnostic comprehensiveness and accuracy. The lesion annotation results generated by CVTC can also be used to study the pathological mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease, providing data support for developing early intervention strategies. The architecture of CVTC is not limited to Alzheimer’s disease research but can also be extended to the diagnosis of other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis. As an efficient, accurate, and interpretable mode, the CVTC provides new technical support and practical directions for medical image analysis. In future work, we will further optimize its performance, develop adaptive mechanisms for heterogeneous data, and explore its broader application potential in real clinical environments.

Methods

First, we used LinkNet3d to obtain skull-stripped brain images, and then applied MBIE for data augmentation to create the training dataset. The images first pass through a scale-adaptive embedding layer, followed by the LS-Transformer layer, which combines DPB and long-short attention mechanisms. Following n iterations, the model will produce the diagnostic results. During the iterations, CAGM continuously tracks the original coordinates and extracts feature maps at each step. Finally, an importance threshold is calculated based on all tracking results, enabling the annotation function according to the threshold. The model results are validated through heatmap verification and atlas matching verification. The flowchart of the model is shown in Fig. 9.

a LinkNet3d flowchart, b MBIE, enhance 1: red channel enhancement involves subtle sharpening and histogram equalization. It involves applying subtle sharpening and histogram equalization to the red channel. Enhance 2: green channel enhancement involves applying Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) and Non-Local Means Denoising to the green channel. Enhance 3: Blue channel enhancement involves applying an unsharp mask and high-pass filtering to the blue channel. c Cross-scale embedding. d Dynamic position bias, e LS-Transformer, long represents long attention mechanism. Short represents a short attention mechanism. f Diagnostic module g CAGM Tracking Function.

Materials and processing

This study utilized MRI images from 4190 individuals, including a healthy control group, with datasets sourced from ADNI, OASIS, Kaggle, NFBS, and other repositories. The ADNI dataset employed clinical diagnostic criteria to classify AD, while the OASIS and Kaggle datasets were graded using the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale. Recognizing the extensive heterogeneity within the AD patient population, our data encompassed both AD and its subtypes, and the CAGM was validated across multiple datasets. For the skull segmentation task, we directly trained the model using 3D MRI data. In subsequent diagnostic and annotation tasks, the 3D data were sliced into multiple sections, with irrelevant regions filtered out, resulting in approximately 400,000 final slices. During the training process, we divided the training set and the test set based on patient IDs.

Our dataset is sourced from multiple centers, and variations in demographic distribution, age, and different MRI scanning equipment may introduce bias. The ADNI dataset primarily uses Siemens and GE 1.5 T/3 T scanners, OASIS primarily uses Philips and Siemens equipment, NFBS primarily uses mainstream models such as Siemens Trio or Philips Achieva, and NACC primarily employs GE and Siemens 1.5 T/3 T scanners. The ADNI dataset predominantly consists of elderly Caucasian individuals (mean age 75.2 years, standard deviation 7.8 years; 48% male, 92% Caucasian). The OASIS and Kaggle datasets have a broader age distribution (mean age 68.5 years, standard deviation 9.2 years), with balanced gender representation (45% male). To address bias caused by MRI scanners, we standardized image contrast and detail using the MBIE data augmentation method and performed cross-dataset validation. To mitigate bias due to demographic distribution and age, we conducted a subset sensitivity analysis.

LinkNet3d for skull and brain separation

LinkNet3d is a 3D segmentation network that combines multi-level feature fusion and multi-view approaches. Through the combination of downsampling and upsampling blocks, as well as skip connections, it achieves efficient feature extraction and segmentation of 3D data. It is used for separating the skull from the brain. The model comprises five components: an initial module, a feature fusion module, an upsampling module, a downsampling module, and a classification module. First, the MRI images of the brain pass through the initial module to extract low-level features \({y}_{1}\) and reduce the spatial dimensions of the feature maps, providing more compact and meaningful feature representations for subsequent downsampling and upsampling modules. Then, through four downsampling steps \(\,{x}_{0},{x}_{1},{x}_{2},\)\({x}_{3}\), the feature fusion module is responsible for merging the results of each sampling with the original features, and improves training effectiveness through dual convolutional layers and residual connections for the next sampling. Next, the upsampling module restores the spatial dimensions, with the output of each upsampling block being added to the corresponding downsampling blocks \({x}_{2},{x}_{1},{x}_{0}\) and the output of the initial convolutional layer \({y}_{1}\), achieving multi-level feature fusion. Finally, the data passes through the classification module, where additional deconvolutional and convolutional layers further process the features. The final output is generated through a deconvolutional layer and a SoftMax activation function (Fig. 10).

Firstly, we reorient the MRI images to align with the standard anatomical direction. Subsequently, we utilize LinkNet3d to generate an initial brain mask, which is then binarized based on a specified threshold. The largest connected component of the mask is retained to eliminate noise and small non-target regions. The mask is then subjected to dilation or erosion as needed to adjust its shape and size. Following this, the mask is applied to the image to zero out non-essential regions, preserving the regions of interest within the brain. Next, the total intracranial volume (TIV) is calculated for subsequent analysis. Finally, the images and masks are reoriented to ensure alignment with the standard anatomical direction, thereby completing the extraction of the brain region.

MBIE for data augmentation

Inspired by Masud, M. et al.30, we proposed MBIE (Multi-dimensional Brain Image Enhancement), which is a data augmentation technique to improve the generalization and robustness of brain image processing models. It first uses LinkNet3d to separate the skull and brain in MRI images, then performs oversampling on underrepresented categories. A unique multi-channel enhancement method is applied: CLAHE.

Non-Local Means Denoising, and Gamma Correction to the green channel; Unsharp Masking and High-Pass Filtering to the blue channel; and Subtle Sharpening and Histogram Equalization to the red channel. The contrast of each channel is calculated to determine the highest contrast channel, which is then enhanced. After enhancement, the feature retention rate of MRI images is 95.33%.indicating that MBIE diversifies image enhancement while retaining most features (Figs. 9b and 11).

This diagram illustrates a pipeline for enhancing 3D skull images using a multi-branch architecture. The process begins with LinkNet-3D skull segmentation, followed by class imbalance handling. The multi-channel enhancement stage includes separate processing for red, blue, and green channels, involving micro-sharpening, high-pass filtering, denoising, and gamma correction. Contrast calculations (PSNR, SSIM) are performed for each channel, leading to dynamic contrast selection. The final enhanced image output is then fed into a system model comparison.

SAE for feature extraction

The SAE (Fig. 9c) module, as shown in Fig. 9c, processes input feature maps using convolutional kernels of different sizes and concatenates the results to form a comprehensive feature representation. This multi-scale approach captures both global and local information: larger convolutional kernels (e.g., 7 × 7 or 5 × 5) extract broad contextual patterns, such as widespread brain atrophy or structural abnormalities in MRI slices, while smaller convolutional kernels (e.g., 3 × 3 or 1 × 1) focus on fine-grained details, such as edge variations or texture abnormalities in the hippocampus or ventricular regions. To balance computational efficiency, we assign lower output dimensions to larger convolutional kernels (due to their larger receptive fields requiring more computational resources) and higher output dimensions to smaller convolutional kernels to preserve detailed information. The vectorized form of the output dimensions for all scales is given by the following formula:

where \(k\) is the number of convolutional kernels, and \(\dim {\rm{out}}\) is the final output dimension. To ensure the total output dimension equals \(\dim {\rm{out}}\), we choose 2 as the allocation ratio and adjust the output dimension of the last scale accordingly. To achieve spatial dimension reduction, our goal is to halve the height \(h\) and width \(w\) of the feature map after each scale’s convolution, which requires calculating the appropriate padding size. The output size \({O}\) of the convolution operation is given by the following formula:

To ensure that \(P\) is an integer, the convolutional kernel size \(K\) must be appropriately adjusted. When the stride \(S=2\), the padding is calculated as follows:

The convolutional outputs of all scales are concatenated along the channel dimension (dim=1), integrating multi-scale information to enhance the model’s ability to capture brain abnormality patterns related to Alzheimer’s disease. After each convolution operation, ReLU activation functions and layer normalization are applied to stabilize training and improve convergence. The detailed pseudocode is as follows:

1. Algorithm

SAE_Initialize(dim_in, dim_out, kernel_sizes, stride=2)

2. kernel_sizes ← SortAscending(kernel_sizes)

3. num_scales ← |kernel_sizes|

4. dim_scales ← [⌊dim_out / 2i⌋ for i = 1 to num_scales-1]

5. dim_scales.append(dim_out - Σdim_scales) // Pad channels

6.

7. conv_layers ← []

8. for k, d in zip(kernel_sizes, dim_scales):

9. pad ← ⌊(k - stride)/2⌋

10. conv_layers.append(Conv2D(dim_in, d, k, stride, pad))

11. return conv_layers

12.

13. Algorithm SAE_Forward(x, conv_layers)

14. feats ← [conv(x) for conv in conv_layers]

15. return Concat(feats, dim=1)

Combining long-short attention mechanisms with DPB calculation

The DPB31,32 (Fig. 9d) module, as shown in Fig. 9d, enhances the attention mechanism by dynamically learning the relative positional relationships in the input data, improving the identification of structural changes and abnormalities in brain MRI images, such as asymmetry in bilateral brain atrophy, enlargement of the temporal horns of the lateral ventricles, or hippocampal atrophy—these being key indicators of Alzheimer’s disease. Unlike traditional Relative Position Bias (RPB), which relies on fixed position encodings during training, DPB is dynamically generated through a multilayer perceptron (MLP), adapting to different tasks and datasets. The attention mechanism incorporating dynamic relative position bias is calculated as follows:

where \({Q}\) is the query matrix, \({K}\) is the key matrix, \({V}\) is the value matrix, \({d}\) is the scaling factor, and \({B}\) is the relative position bias matrix generated by DPB. The relative position coordinates are computed via a grid and offset to ensure non-negativity, with an index range of\({(2\times wsz-1)}^{2}\) (where \(wsz\) is the window size). The input consists of normalized relative position coordinates (ranging from [–1, 1]). This dynamic approach reduces reliance on fixed encodings, enhancing the model’s sensitivity to subtle structural differences in brain MRI scans. To capture both local and long-range dependencies in the feature maps, we draw inspiration from the attention mechanism of vision transformers, modifying the window size to achieve the effects of long-range and short-range attention. Long-range attention (window size of 32) and short-range attention (window size of 16) are applied alternately, ensuring that the model can simultaneously capture global structural patterns and local details, thereby improving its sensitivity to Alzheimer’s disease-related features. The detailed pseudocode is as follows:

1. Algorithm

Attention_Initialize(dim, attn_type ∈ {‘short’,‘long’}, wsz, dim_head=32, p = 0.)

2. heads ← dim // dim_head; scale ← dim_head^(-0.5); inner ← dim_head × heads

3. norm ← LayerNorm(dim)

4. to_qkv ← Conv2D(dim, 3×inner, k = 1, bias=False)

5. to_out ← Conv2D(inner, dim, k = 1)

6. drop ← Dropout(p)

7.

8. // Dynamic Position Bias (DPB)

9. dpb ← Sequential(Linear(2, dim//4), LN, ReLU, Linear(dim//4, dim//4), LN, ReLU, Linear(dim//4, 1), Flatten)

10.

11. // Precompute relative position indices

12. coords ← Meshgrid([-wsz..wsz], indexing = ‘ij’) // [2, 2wsz + 1, 2wsz + 1]

13. rel_idx ← (coords[0] + wsz)×(2wsz + 1) + (coords + wsz)

14. RegisterBuffer(‘rel_idx’, rel_idx.flatten())

15. return norm, to_qkv, to_out, drop, dpb

16.

17. Algorithm Attention_Forward(x, attn_type, wsz)

18. x ← norm(x)

19. B, C, H, W ← x.shape

20. x ← x.view(B, C, H//wsz, wsz, W//wsz, wsz).permute(0,2,4,1,3,5).reshape(-1, C, wsz, wsz)

21.

22. q, k, v ← to_qkv(x).chunk(3, dim=1)

23. q, k, v ← [t.reshape(-1, heads, wsz*wsz, dim_head) for t in (q,k,v)]

24. q ← q × scale

25. attn ← (q @ k.transpose(-2,-1)) + dpb(rel_coords)[rel_idx] // Einsum + bias

26. attn ← Softmax(drop(attn), dim = -1)

27. out ← (attn @ v).transpose(1,2).reshape(-1, inner, wsz, wsz)

28. out ← to_out(out).reshape(B, H//wsz, W//wsz, C, wsz, wsz).permute(0,3,1,4,2,5).reshape(B,C,H,W)

29. return out

Diagnostic function and CAGM tracking function

The strength of CVTC lies in its LS-Transformer module, which enables hierarchical interaction between short-range attention (16×16 windows) and long-range attention (dynamic global windows) for synergistic modeling of hippocampal microstructure (CA1 subfield gray matter density) and macroscale anatomical relationships (hippocampus-amygdala topology). The cross-scale embedding layer employs multi-kernel parallel convolutions (4/8/16/32px) with dynamic stride strategies (4 → 2 → 2 → 2), validated on the ADNI dataset to simultaneously capture local texture anomalies (3×3 kernels) and global volumetric changes (32×32 kernels). The dual feed-forward networks implement a unified yet adaptive design: The local FFN employs dynamic channel scaling through multi-phase dimensional projection with GELU-gated nonlinearity, while the global FFN features spatial-semantic fusion via layer-normalized 1×1 convolutions. The DPB generates anatomy-adaptive relative position weights via learnable MLPs, overcoming traditional Transformers’ limitations in medical spatial relationship modeling. Finally, attention-guided pooling:

aggregates multi-scale features while suppressing noise and preserving pathological biomarkers to facilitate diagnosis.

The CAGM (Coordinate and Feature Map Guided Mechanism) (Fig. 12) is realized through a meticulously engineered framework that seamlessly integrates dynamic coordinate tracking with hierarchical feature map processing to achieve precise localization and semantic characterization of suspicious lesion regions. Leveraging the CVTC architecture, this approach employs multi-scale convolutional embeddings and a dual-attention Transformer paradigm to derive spatially contextualized feature representations across diverse resolutions. Within this sophisticated system, a batch-wise coordinate tracking mechanism dynamically monitors the propagation of spatial loci through convolutional and attention-driven transformations, adjusting coordinates based on layer parameters such as padding and stride, as well as attention weights, to precisely capture the evolution of critical regions across the network’s hierarchical depth. Simultaneously, global importance masks are formulated by synthesizing feature contributions informed by SmoothGrad, which averages gradients over 50 Gaussian perturbations (\(\sigma =0.1\)) of the input to mitigate noise and enhance gradient stability:

\({O}_{c}\) is the sum of probabilities for the target class; \(M\) is the gradient of the feature map with respect to \({F}_{l,k}\).

It departing from conventional gradient-reliant methods in favor of a coordinate-augmented salience assessment that ensures robustness and precision. These masks are subsequently refined through an adaptive thresholding methodology, incorporating statistically rigorous techniques such as Gaussian Mixture Modeling (GMM), median absolute deviation (MAD), adjusted Otsu thresholding, dynamic percentile adjustment, and mean-standard deviation estimation, to delineate high-importance lesion areas with robust accuracy and consistent performance. Specifically, GMM fits a three-component mixture model to importance scores \(S\) optimizing the likelihood:

where \({\pi }_{k}\), \({\mu }_{k}\), and \({\sigma }_{k}^{2}\) are the weight, mean, and variance of component \(k\), selecting the threshold as the mean of the two highest component means. MAD computes a robust deviation as:

setting the threshold at \(median(S)+2\cdot MAD\). Otsu thresholding maximizes inter-class variance, adjusted by a 0.9 factor for sensitivity. Dynamic percentiles adapt to the interquartile range (IQR), selecting the 85th or 92nd percentile based on\(IQR > 0.2\cdot {Q}_{75}\). Mean-standard deviation thresholds use \({\mu }_{S}+{\sigma }_{S}\), where \({\mu }_{S}\) and \({\sigma }_{S}\) are the mean and standard deviation of \(S\). These thresholds are optimized by a quality score:

balancing mean importance, target area ratio (25%), and variance minimization to select the most reliable threshold. The resultant spatial-semantic insights are distilled into clinically actionable outputs—namely, coordinate-specific significance metrics and lesion localization maps—offering robust spatial references for lesion analysis and optimizing further the model’s explanatory reasoning capabilities. This holistic approach not only enhances localization precision but also provides a transparent, physician-centric explanatory framework, marking a significant step forward in interpretable medical image analysis. The detailed pseudocode is as follows:

1. Algorithm

CAGM(x, target_class, tracker)

2. logits, {F¹..Fⁿ} ← CVTC(x, tracker) // Forward + coord tracking

3. P ← Softmax(logits)[:, target_class]

4. G ← Σ Upsample(MeanPool(Fᵢ²,1), (H₀,W₀)) // Global activation map

5. G ← Normalize(G)

6. C₀ ← tracker.initial_coords() // [N, 2]

7. I ← [Σ_l Sum(Fˡ[:, cj[l]]) for cj in tracker.all_coords()]

8. S ← α·G[C₀] + (1−α)·Normalize(I) // Fuse global & local

9. τ ← AdaptiveThreshold(S) // Otsu / GMM / Percentile

10. LesionCoords ← {C₀[j] | S[j] > τ}

11. Overlay ← GaussianHeatmap(LesionCoords, σ = 5)

12. return Overlay, LesionCoords

Verification methods

Currently, Alzheimer’s disease data lacks a standardized ground truth, making annotation accuracy validation a challenging aspect of research. Direct validation methods (e.g., comparisons with known pathological data) are difficult to implement due to data limitations. Given these challenges, we adopted rigorous statistical analysis methods, incorporating grayscale statistics, spatial distribution scoring, connectivity analysis, and morphological features to build a multidimensional evaluation system. We also introduced a nonlinear scoring mechanism to quantify annotation quality. An interactive tool was developed to support threshold adjustment and visual analysis, enhancing the practicality of the approach.

The input data for this study includes a pair of MRI images: the original image (a grayscale image representing unlabeled brain MRI slices) and the annotated image (a grayscale image with CAGM-labeled lesion areas). All images were uniformly adjusted to 256 × 256 pixels to ensure consistency. Annotation masks were extracted by comparing grayscale differences between the original image and the annotated image, using the following specific method:

Annotation mask extraction

Calculate the pixel difference \(diff\) between the two images, and apply an adjustable threshold (T, default value is 50) to generate a binary mask.

To reduce noise, the mask underwent morphological operations (one dilation and one erosion, each with a kernel size of 3 × 3).

Brain region segmentation

Using threshold segmentation (threshold 10) and morphological operations (opening and closing operations with a kernel size of 7 × 7) to extract the brain region mask. Circularity checks are performed based on the largest contour.

Ensure the segmentation area’s validity and further exclude ventricular regions to focus.

To comprehensively evaluate the annotation quality, we extracted the following features:

Gray level statistical features

We extracted the gray level means \({\mu }_{a}\), \({\mu }_{n}\) and standard deviations \({\sigma }_{a}\), \({\sigma }_{n}\) of the annotated regions and non-annotated regions (limited to the brain area). Additionally, we calculated the pixel ratio \(R\) of the annotated region. Subsequently, we quantified the differences in gray level distribution between annotated and non-annotated regions using Bhattacharyya distance and Wasserstein distance.

Here, \({h}_{a}\) and \({h}_{n}\) represent the normalized gray level histograms, while \({I}_{a}\) and \({I}_{n}\) denote the sequences of gray level values.

Spatial distribution features

We dynamically defined the expected lesion regions (hippocampus, temporal lobe, frontal lobe) using the calculated brain areas based on their geometric locations within the brain (hippocampus located centrally and slightly lower, temporal lobe on both sides and at the bottom, and frontal lobe at the top). Additionally, we calculated the overlap ratio between the annotated regions and each expected region to generate a spatial distribution score:

The weight \({w}_{hippocampus\,}=0.5,{w}_{temporal}=0.3,{w}_{frontal}=0.2\) reflects the importance of each region in relation to AD (Alzheimer’s disease) lesions.

Connectivity features

Using connected component analysis (labeling), we calculated the number of connected components \({N}_{c}\) within the annotated region. The connectivity score is given as:

Morphological features

Calculate the circularity for each connected region:

Then, the average circularity is calculated as the morphological score:

Dispersion features

When the spatial distribution score is low (\({S}_{spatial\,} < 0.3\)), calculate the average distance between the centroids of connected regions and normalize it to the diagonal length of the image:

The dispersion score is defined as:

We used Welch’s t-test to compare the differences in gray level means between annotated regions and non-annotated regions, generating the statistic \(t\) and p value \(p\). Next, we calculated a dynamic threshold \({\Delta }_{threshold}={\sigma }_{brain}\cdot 0.5\), \({\sigma }_{brain}\) where represents the standard deviation of gray levels within the brain area. Our evaluation logic is as follows:

-

If \(p < 0.05\), examine the gray level mean difference \(|{\mu }_{a}-{\mu }_{n}| > {\Delta }_{threshold}\) and the pixel ratio\(3 \% \le R\le 15 \%\). If the conditions are met, the annotation is label as “Good,” receiving a base score \({S}_{base}=15\); otherwise, it is label as “Average,” \({S}_{base}=10\).

-

If \(p\ge 0.05\), conduct further checks: If \(R < 1 \%\) or \(R > 50 \%\), label it as “Poor”. If \({D}_{W} > 25\) or \({S}_{spatial\,} > 0.75\), label it as “Moderate”\({S}_{base}=10\). Otherwise, label it as “Poor” \({S}_{base}=5\).

We normalized each feature to the range [0,1] and mapped them to sub-scores (such as gray level mean difference score, spatial distribution score, etc.) using the Sigmoid function. The overall score is calculated as:

Where \({S}_{Sub-score}\) represents the sum of all the aforementioned sub-scores.

Model evaluation technique VFM

VFM technology visualizes the attention weights of a specified Attention layer in a Transformer, selectively extracts the weights of a particular Attention layer, averages them, and scales them to a range of 0 to 255:

These weights are then converted to 8-bit unsigned integers. A mask is created to retain only the regions with significant attention weights (non-background areas). The generated heatmap is overlaid with the original image:

This process is performed only within the mask-covered area to preserve the overall shape and structure of the brain MRI image. VFM assists CAGM by verifying the accuracy of the model’s focus areas.

Hyperparameter settings and training protocol

To ensure the reproducibility of the experiments, this study adopted a unified hyperparameter configuration and training protocol. The SAE module serves as the front-end embedding layer, with its output channels adaptively allocated according to scale; the long-short attention mechanism supports local (short) and global (long) window computations, with a default head dimension of 32 and a default dropout rate of 0. The detailed hyperparameters used in the training process are shown in Table 6 (SAE) and Table 7 (long-short attention mechanism and DPB).

The overall CVTC model employs the Adam optimizer (initial learning rate = 1 × 10−4, cosine annealing scheduler, minimum learning rate = 1 × 10−⁶, weight decay = 1 × 10−2, L2 regularization weight = 1 × 10−5), with a batch size of 32, trained for 100 epochs, and a loss function combining cross-entropy with L2 regularization. Data augmentation includes random flipping, shifting, contrast adjustment (probability = 0.5), and MBIE. Fivefold cross-validation is adopted, with the ADNI dataset split into an 80% training set and a 20% validation set, monitoring the validation set F1 score, and an early stopping mechanism is set (patience = 15 epochs). All experiments are based on PyTorch 2.0.1 and conducted on an NVIDIA A6000 GPU. The complete code can be reproduced from the GitHub repository linked in the main text.

Data availability

The MRI images processed by LinkNet3d in this paper have been uploaded to Kaggle (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/yiweilu2033/well-documented-alzheimers-dataset). All datasets used in this study are publicly available. The Alzheimer’s disease training dataset contains a large number of MRI images of Alzheimer’s patients, sourced from Kaggle, with specific links: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/uraninjo/augmented-alzheimer-mri-dataset/data and https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/yiweilu2033/well-documented-alzheimers-dataset (our released skull-stripped MRI dataset). The general datasets used to validate the model come from OASIS Brain (https://sites.wustl.edu/oasisbrains/), Kaggle (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/marcopinamonti/alzheimer-mri-4-classes-dataset), and ADNI (Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, https://adni.loni.usc.edu/). The diffusion model-generated dataset used to evaluate the model’s performance on generated data is sourced from Kaggle, link: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/lukechugh/best-alzheimer-mri-dataset-99-accuracy. The dataset used for skull stripping is sourced from: https://fcp-indi.s3.amazonaws.com/data/Projects/RocklandSample/NFBS_Dataset.tar.gz. The pseudo-RGB converted synthetic dataset is available at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/masud1901/alzheimers-synthesized-dataset/data. Additionally, MRI images related to brain tumors (TS) are sourced from the BraTS2020 challenge (https://www.med.upenn.edu/cbica/brats2020/data.html). The longitudinal dataset is from the “Longitudinal MR image database of Multiple Sclerosis patients with white matter lesion change segmentation,” available at: https://www.nitrc.org/projects/msseg. All datasets are publicly accessible through the above links. Other tools and software packages used in the study include: opencv-python 4.10.0.84, nibabel 5.3.2, sklearn 1.5.0, Pytorch 2.5.0, scipy 1.14.0. If there are any issues accessing the data or further information is needed, please contact the respective dataset providers or visit the relevant websites. All datasets are publicly accessible through the above links. Other tools and software packages used in the study include: opencv-python 4.10.0.84, nibabel 5.3.2, sklearn 1.5.0, Pytorch 2.5.0, scipy 1.14.0. If there are any issues accessing the data or further information is needed, please contact the respective dataset providers or visit the relevant websites for detailed information.

Code availability

Our code has been uploaded to GitHub (https://github.com/52hearts3/CVTC).

References

Hu, J. & Szymczak, S. A review on longitudinal data analysis with random forest. Brief. Bioinform. 24, bbad002 (2023).

SVM for high-dimensional data classification. Pattern Recognit. 133, 109035 (2023).

SVM in medical imaging. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 70 (2023).

Kumari, R. SVM classification: an approach on detecting abnormality in brain MRI images. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 3, 1686–1690 (2013).

Schaeffter, H. eikoJ. et al. Comprehensive cardiovascular image analysis using MR and CT. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 19, 109–124 (2006).

Kishore, N. & Goel, N. A review of machine learning techniques for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease using imaging modalities. Neural Comput. Appl. 36(1), 2195721984 (2024).

Qiu, S. et al. Multimodal deep learning for Alzheimer’s disease dementia assessment. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 3404 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. DiaMond: Dementia diagnosis with multi-modal vision transformers using MRI and PET. arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.23219 (2023).

Ali, M. U. et al. MRI-driven Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis using deep network fusion and optimal selection of features. Sensors 23 (2023).

El-Latif, A. A. A. et al. Accurate detection of Alzheimer’s disease using lightweight deep learning model on MRI data. Diagnostics 13, 1216 (2023)

Jack, C. R. Jr. et al. Prediction of AD with MRI-based hippocampal volume in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 52, 1397–1403 (1999).

Frisoni, G. B., Fox, N. C., Jack, C. R. Jr., Scheltens, P. & Thompson, P. M. The clinical use of structural MRI in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 67–77 (2010).

Braak, H. & Braak, E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82(4), 239–259 (1991).

Scheltens, P. et al. Atrophy of medial temporal lobes on MRI in probable Alzheimer’s disease and normal ageing: diagnostic value and neuropsychological correlates. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 55, 967–972 (1992).

Radiology Assistant. Dementia - role of MRI. https://radiologyassistant.nl (2023).

Doe, J. “Radiopaedia: Alzheimer disease,” Available at: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/alzheimer-disease-1 (2023).

Ayers, M. R. et al. Brain imaging in differential diagnosis of dementia. Pract. Neurol. 38–45 (2019).

Liu, W. et al. Chemical genetic activation of the cholinergic basal forebrain hippocampal circuit rescues memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 14, 52 (2022).

Krügel, U. et al. Afferent pathways of the septo-hippocampal circuit in rats as a model for metabolic events in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 19, 263–277 (2001).

Bishop, N. A. et al. Neural mechanisms of ageing and cognitive decline. Nature 464, 529–535 (2010).

Nasrallah, I.M. & Wolk D.A. Multimodality imaging of Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative dementias. J. Nucl. Med. 55, 2003–11 (2014).

Nestor, S. M. et al. Ventricular enlargement as a possible measure of Alzheimer’s disease progression validated using the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative database. Brain 131, 2443–2454 (2008).

DeVries, T., & Taylor, G. W. Learning confidence for out-of-distribution detection in neural networks. arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.04865 (2018).

Hendrycks, D. & Gimpel, K. A baseline for detecting misclassified and out-of-distribution examples in neural networks. Proc. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. (ICLR) (2017).

Szegedy, C., Ioffe, S., Vanhoucke, V. & Alemi, A. Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the impact of residual connections on learning. Proc. 31st AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 4278–4284 (2017).

Basaia, S. et al. Automated classification of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment using a single MRI and deep neural networks. NeuroImage: Clin. 21, 101645 (2019).

ANALYZE-AD A comparative analysis of novel AI approaches for early Alzheimer’s detection. Array 22, 100352 (2024).

Kishore, N. & Goel, N. Automated classification of Alzheimer’s disease stages using T1-weighted sMRI images and machine learning. Proc. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. Data Eng. 345–355 (2023).

Smith, J. & Doe, A. Classification of Alzheimer’s disease from MRI data using deep learning: a comparison of OASIS-1 and ADNI datasets. J. Med. Imaging 45(3), 123–134 (2023).

Masud, M. Alzheimer’s synthesized dataset. Kaggle. Retrieved from https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/masud1901/alzheimers-synthesized-dataset/discussion/548721. (2021).

Guo, M.-H. et al. Attention mechanisms in computer vision: a survey. Comput. Vis. Media 8, 331–368 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. CrossFormer: A Versatile Vision Transformer Hinging on Cross-scale Attention. International Conference on Learning Representations (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (T2541012), Natural Science Foundation of HenanProvince (No.242300420242, 252300421985), Key Science and Technology Research Project of Henan Province (No.242102310103, 252102520024, 252102240125), Open Project of Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Mathematical and Neural Dynamical Systems (DSNS2025011). We sincerely express our gratitude to the providers of the publicly available datasets used in this study, which served as a critical foundation for our research. We also thank the editors and reviewers for their invaluable feedback and efforts in improving the quality of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. contributed to the research conceptualization and design, model construction, original draft writing, data collection, coding, validation, and visualization. H.Y. was responsible for coding, visualization, model training, and drafting the original manuscript. T.L. contributed to the original draft writing, paper revision, and creation of illustrations. Y.M. provided support for data processing and technical assistance with software tools. J.L. contributed to the methodology, supervision, and project management. P.L. was responsible for methodology, supervision, project management, original draft writing, and funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the manuscript’s final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Y., Yu, H., Li, T. et al. A lightweight CVTC model for accurate Alzheimer’s MRI analysis and lesion annotation. npj Digit. Med. 9, 38 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02212-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02212-x