Abstract

Current discussion surrounding the clinical capabilities of generative language models(GLMs) predominantly centers around multiple-choice question-answer(MCQA) benchmarks derived from clinical licensing examinations. While accepted for human examinees, characteristics unique to GLMs bring into question the validity of such benchmarks. Here, we validate five benchmarks using eight GLMs, ablating for parameter size and reasoning capabilities, validating via prompt permutation three key assumptions that underpin the generalizability of MCQA-based assessments: that knowledge is applied, not memorized, that semantic consistency will lead to consistent answers, and that situations with no answers can be recognized. While large models are more resilient to our perturbations compared to small models, we globally invalidate these assumptions, with implications for reasoning models. Additionally, despite retaining the knowledge, small models are prone to memorization. All models exhibit significant failure in null-answer scenarios. We then suggest several adaptations for more robust benchmark designs, more reflective of real-world conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent attention surrounding large language models(LLMs) has driven great interest in utilizing such models for clinical purposes1,2, particularly in the context of learning healthcare systems. A prerequisite to practical adoption is, however, evaluation: an open question when discussing LLMs that covers a multitude of dimensions and considerations3. Historically, the evaluation of artificial intelligence and machine learning (AIML) models for clinical tasks was done task-specifically due to implementation considerations and technical limitations of pre-LLM models. Specifically, such models generally required finetuning for adaptation for differing tasks4,5,6 and were cheap to train or fine-tune while requiring costly annotated datasets7,8. The incentives surrounding evaluating such models can thus be characterized as datasets being expensive, model inference being cheap, and model training being moderately costly, with model training to fit the dataset always being required.

LLMs represent a drastic shift, being computationally intensive and costly to run, requiring substantial hardware and time investment, and expensive to fine-tune. Concurrently, their popularity lies in generalizability across a wide range of tasks without the need for extensive fine-tuning. This shift is further driven by growing interest in small language models9,10,11 (SLMs) and multi-agent systems12,13,14,15, driven in large part by the high, vertically-scaling, resource requirements of large, widely generalizable, language models. Given the wide variety16 of models that exist today, each with its own specializations, and the fact that each model still represents a significant resource and time investment, it is helpful to have a general characterization of their clinical performance to subset viable candidates for further evaluation. Consequent to these incentives, there has been a shift towards using general-purpose benchmarks that aim to assess a model’s overall clinical competency and reasoning ability prior to engaging in task-specific fine-tuning and evaluation.

Among these general evaluation strategies, multiple-choice question answer (MCQA) benchmarks have emerged as the predominant methodology. Benchmarks such as the US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE)17 and datasets like MedQA18 and MMLU19 are frequently employed to assess model performance due to their wide availability, straightforward evaluation, obviating engagement of clinical domain expertise, and simple implementation. Additionally, these benchmarks align with human clinical licensure processes, further lending credence to claims on model clinical capability. As a result, much of the discussion surrounding LLMs centers on their competitive performance on these MCQA benchmarks, which has led to scrutiny regarding their validity and applicability20.

Beyond concerns21 on memorization and applicability to generation tasks, licensing examinations inherently assess general reasoning rather than disease-specific expertise, assuming that possession of requisite knowledge enables clinicians to arrive at accurate diagnoses and treatments through reasoning. Models, however, differ fundamentally from humans. Human strength lies in problem-solving, not in flawless knowledge retention, and we trust that if the requisite clinical knowledge is present, the human can consistently apply a reasoning process to arrive at the correct answer. Conversely, models excel at context matching but have shown limitations in reasoning fidelity22, particularly with reasoning models leveraging integrated chain-of-thought-based approaches23. Fundamentally, this difference therefore challenges the construct validity of MCQAs as an assessment method.

Nevertheless, MCQAs are still valuable: the straightforward evaluation and wide coverage remain one of the best ways to quickly capture a general sense of model clinical capabilities without significant time/effort investment, particularly as interest shifts to amalgamations of smaller specialized models. In this study, we therefore aim to assess the validity of the assumptions underpinning the generalizability of MCQA-style benchmarks across both model size and reasoning capabilities, highlight their limitations when used to infer real-world clinical competency, and determine the degree to which contextual cues provided by the MCQA format impact the generalizability of the model’s observed performance.

Results

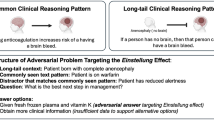

We test three baseline assumptions that underpin MCQA generalizability:1) that a successful answer implies that requisite knowledge is possessed, retrieved, and, in particular, applied to the problem, rather than just being memorized, 2) that the same semantic problem will lead to the same answer despite syntactic permutation, and 3) given the same knowledge, the examinee can identify when there is no correct answer presented in the options. Additionally, we assess the models’ dependence on the restricted search space afforded by the multiple-choice format by obfuscating or occluding context for each of the three assumptions. These assumptions are tested via prompt permutations (Fig. 1) on benchmark questions that models were able to answer correctly in their original form.

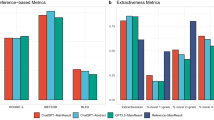

We show the baseline accuracy for our datasets of the various models assessed in this study in Table 1, and the answer consistency upon permutation of the respective MCQA assumptions (color), alongside the impact of context availability (hash) for each of our varying experimental settings in Fig. 2.

Generally, large models tend to perform well on Setting 1 (with the exception of GPT-OSS), although the expansion to 26 options does cause some consistency loss (\(\bar{{\Delta }_{{all},{opt}\_{expansion}}}=-0.071\pm 0.019\), \(p < 0.001\)). The drop in consistency is, however, generally much more pronounced for small models (denoted with a *) compared to larger models, in both the original (\({\Delta }_{{large}\_{vs}\_{small},{orig}\_{ctx}}=-0.131\pm 0.040,\) \(p < 0.001\)) and expanded (\({\Delta }_{{large}\_{vs}\_{small},{expanded}\_{ctx}}=-0.187\pm 0.056,p < 0.001\)) search space.

While strong consistency is maintained for most large models in Setting 2 when identifying truths with full context (R1-Llama-70B: \(\Delta =-0.012\pm \,0.013,{\rm{p}} < 0.001\), Llama-70B: \(\Delta =-0.037\pm 0.026,\,\) p < 0.001\(,\,{\rm{QwQ}}:\Delta =-0.041\pm 0.015,{p} < 0.001)\) as well as in the small reasoning model R1-Llama-8B (\(\Delta =-0.077\pm 0.053,{p} < 0.001\)), substantial drops are observed for GPT-OSS-120B (\(\Delta =-0.608\pm 0.043,{p} < 0.001)\,\) and Qwen-2.5-32B \((\Delta =-0.295\pm 0.050,{p} < 0.001)\), as well as in the other small models (GPT-OSS-20B: \(\Delta =-0.529\pm 0.038,{p} < 0.001;\) LLaMA-8B\(:\Delta =-0.218\pm 0.028,{p} < 0.001)\). The same largely holds true for the identifying falsehoods case, albeit with all small models performing poorly in terms of consistency and Qwen performing well. In both settings, the removal of the contextual hints provided by the other options being available in the prompt context had a significant effect on most model’s answer consistency (for identifying truths, GPT-OSS-120B \(p < 0.002\), R1-LLaMA-70B \(p < 0.001\), QwQ-32B \(p < 0.001\), Qwen2.5-32B \(p < 0.001\), LLaMA-8B \(p < 0.002\), LLaMA-70B, R1-LLaMA-8B, and GPT-OSS-20B not significant; for identifying falsehoods, GPT-OSS-120B \(p < 0.001\), GPT-OSS-20B \(p < 0.001\), LLaMA-8B \(p < 0.001\), all other models not significant), although not always negatively (both GPT-OSS models, and Qwen, for instance, generally seem to perform worse by having the other options in the context irrespective of subtask, and LLaMA-8B when identifying falsehoods).

All models show significant (\(\bar{{\Delta }_{{\rm{all}}}}=-0.475\pm 0.061,{p} < 0.001)\) inconsistency for setting 3 even if a “None of the Above” option is explicitly provided, and even greater (\(\bar{{\Delta }_{{\rm{all}}}}=-0.750\pm 0.057,\,p < 0.001\)) inconsistency for most models if the “None of the Above” option is instead supplied as a prompt instruction.

In Fig. 3, we show the impact of context availability on answer consistency as a function of reasoning models vs. their respective base models.

While we generally observe an improvement in consistency (irrespective of whether context is provided) with the addition of reasoning capabilities (\(\bar{{\Delta }_{{large}}}=0.034\pm 0.026,{p} < 0.001\)), this is not globally true. Specifically, we note that adding reasoning does not significantly affect consistency for small models in Setting 1 \(({\Delta }_{{\rm{LLaMA}}-8{\rm{B}}-{\rm{Base}}}=0.041\pm 0.036{;p} > 0.01)\), and the reasoning process hurts consistency in Setting 2 for R1-8B (\({\Delta }_{R1-8B}=-0.167\pm 0.067,{p} < 0.001)\) and 3 for QwQ/Qwen (\({\Delta }_{{QwQ}}=-0.201\pm 0.023,{p} < 0.001\)) when context is removed.

Finally, in Fig. 4 we show the impact of these individual experimental settings and context availability on the overall dataset performance as a function of the dataset’s difficulty to the individual model (i.e., their baseline performance on the model). Due to figure scale, small models are not included in this figure, although they follow the same trends. We observe a weak correlation between baseline performance and answer consistency (\(\rho =+0.786,{p} < 0.03\)) for all experimental settings, with the magnitude of inconsistency upon context obfuscation/occlusion being model dependent but baseline accuracy independent (\(\rho =+0.278,{p} > 0.1\)).

Discussion

MCQA is accepted as part of the clinical licensure process due to an expectation that, while it is impossible to comprehensively cover all clinical scenarios in any reasonable assessment, it is sufficient to test retained knowledge. The validity of this expectation is underpinned by the human ability to consistently apply knowledge in supporting reasoning. Our experimental settings aimed to systemically evaluate both the extent of retained knowledge, as well as the application of said retained knowledge to actual clinical problem solving.

All large generative language models meet the reported USMLE passing threshold of 60%24,25 for human examinees, although several small models do not. Such performance appears consistent with GLMs bearing a competitive level of clinical knowledge retention on par with human examinees. Our various experiments, however, show that such an appearance may be deceptive, as we surface several concerns that suggest that (a) a certain level of dataset memorization may be being relied on for successful solves, and that (b) such knowledge, even if truly retained, may not be being applied to problem solving. Here, we will discuss these concerns, as well as potential solutions to better adapt MCQA-based benchmarks to the era of data-driven models.

On the applicability of assumptions underlying MCQA as an assessment method for generative language models

The context-matching inherent to MCQA problems inherently tests knowledge retention, as correct responses require the model to generate appropriate statistical priors. While large models remain largely consistent in Setting 1 (although not universally, e.g., in the case of GPT-OSS-120B), small models do not, suggesting some reliance on data memorization for successful solves. Unlike LLMs, which can possess, retrieve, and apply the requisite knowledge, the SLMs skip the last step. The requisite knowledge is retained, but it is not applied: instead, the answer is directly parroted without adaptation to the shuffled option context. Consequently, this brings significant concerns to the generalizability of the evaluation performance on these benchmarks for SLMs. As small models are often distilled from large, this inconsistency/memorization also undermines these assessments on LLMs. While larger models appear capable of compensating for shuffled or perturbed answer structures, this does not eliminate the probability of prior exposure to the benchmark questions themselves. In fact, as small models are often distilled from large, the observed inconsistency suggests that both model classes are influenced by shared exposure to benchmark data. The observed robustness to such perturbations may thus reflect dataset familiarity rather than the ability to truly apply said knowledge in novel situations.

We generally observe SLM inconsistency for Setting 2, invalidating the underlying assumption that syntactic permutations of the same semantic content will lead to the same response. Interestingly, however, the consistency, despite dropping, remains higher than in Setting 1 for R1-LLaMA-8B. While data memorization is likely occurring for successful solves in the traditional multiple-choice context, this finding suggests that some small models do possess, and that the reasoning process can retrieve the requisite knowledge for successful solves, and variations in the prompt syntax are capable of “tricking” the language model to not leverage the memorized shortcut and instead apply the knowledge correctly.

Concerningly, all models, irrespective of big or small, but particularly pronounced in non-reasoning models, show substantial inconsistency in Setting 3, indicating models strongly prefer choosing an available option even when none apply. Such behavior contradicts the assumption that the model is truly applying the knowledge possessed, and is a dangerous limitation in clinical contexts, given the possibility for unexpected and messy inputs in real-world clinical data.

Human consistency is also not perfect. For example, we would expect that were we to add a “none of the above” option in a manner similar to Setting 3 without removing the correct answer, humans would have substantial inconsistency due to human learned MCQA testing strategies. While infeasible to completely control, we note that our adversarial perturbations challenge human strengths and model weaknesses. The “bottleneck” for humans is knowledge retention, which is the strength of data-driven algorithms. Conversely, while data-driven algorithms encode vast volumes of knowledge, said knowledge is not consistently applied in problem solving, which is generally an issue of much lesser magnitude for humans. We generally expect humans to perform well on our tested permutations, particularly where the original context space is provided.

Additionally, it should be noted that control for question-difficulty effects, our 100-question subsets were sampled from questions correctly answered by an intersection of models. This sampling approach biases toward “easier” questions, leading to inflated consistency (empirically confirmed during post-hoc merging of new models into the sample set). To ablate the influence of instruction format and obviate the need for expensive domain expertise, we have preserved a multiple-choice format throughout these experiments, instead of allowing for free-form generation. Fundamentally, due to these factors, the real-world consistency with MCQA-based results may be worse our results suggest, further highlighting the need for additional adaptation to be more reflective of real-world performance.

These observed inconsistencies therefore, call into question the validity of MCQAs as an assessment tool for language models, particularly when model parameter size is small. The likely influence of data contamination and memorization limits the generalizability of observed benchmark performance. For instance, despite GPT-OSS-120B outperforming Deepseek-R1-LLaMA-70B at a surface level on several benchmarks, its accuracy on said benchmarks would be worse than R1’s after application of any of our question format perturbations. Moderate inconsistency in responses with syntactic but without semantic variation challenges the assumption that possessed knowledge is consistently applied, and the strong preference for a positive answer highlights a major weakness of current models in option-selection settings. In a clinical context, these limitations have a direct impact on the very reason we accept multiple-choice questions as an assessment tool for generalized clinical competency, leading to inflated perceptions of model performance.

On the impact of contextual cues amid reasoning models

The removal of contextual cues generally exerts a negative impact on answer consistency (Fig. 2). This is itself concerning as real-world problems can have, depending on use-case, vastly expanded contexts. For instance, expanded contexts (as is the case in setting 1’s context expansion experiment) is a realistic use case as real-world decision making is not limited to a 4-option set. Similarly, it is not always realistic to have present a background listing of “what other items to consider” (which in and of themselves are often designed to contain hints to the correct answer) in the prompt itself in real-world scenarios as is the case in setting 2’s context occlusion experiment.

With respect to the impact of such occlusion and/or obfuscation on reasoning models, when ablated between reasoning/non-reasoning models within the same model family, reasoning models occasionally display greater inconsistency than their non-reasoning counterparts, particularly for models with smaller parameter sizes (Fig. 3), i.e., the reasoning process does not always help improve, but can rather hurt, consistency when context is removed. While this can partially be attributed to higher baseline performance, we posit that the internal chain-of-thought process inherent to reasoning models acts as self-reinforcement by serving as a statistical prior, potentially amplifying inconsistency with loss of context.

On improving model consistency and MCQA as an assessment method

Despite the limitations on their generalizability, MCQAs remain valuable for evaluation in the clinical field due to their unambiguous scoring, efficiency, and lower domain expertise requirements compared to generative methods. It would therefore be beneficial to identify strategies to mitigate the MCQA drawbacks identified in this study while still maintaining the MCQA format. We examine this problem through two lenses: improving the model itself to address these consistency issues, and improving MCQA as an assessment to better reflect real-world conditions.

With respect to the former, we note that consistency is roughly positively correlated with baseline performance. There is reasonable suspicion that some of these inconsistencies are caused by learned shortcuts causing regurgitation rather than a lack of knowledge (Setting 1 vs Setting 2). Given that our various settings are all permutations that can be autonomously generated via symbolic rulesets, it may be beneficial to introduce these symbolic permutations into the model training process itself within the respective training set to, in essence, unlearn the shortcuts and instead encourage the models to apply the knowledge correctly, improving model consistency and potentially generalizability.

In regards to mitigating the impact of context occlusion and obfuscation, it was observed (Fig. 4) that the magnitude of inconsistency increase across the various experimental settings upon context obfuscation/occlusion is independent of the baseline accuracy of the model on said benchmarks, suggesting that the magnitude of inconsistency and dependence on contextual cues is a function of training strategy rather than the data on which the model is trained on. It may be beneficial to further investigate the interplay between these two factors.

With respect to the latter, multiple-choice questions are written to be relatively unambiguous by design. Given the strong dependence on limited option space demonstrated by Setting 1 context removal, it may be beneficial to introduce red herring distractor options (that are close to, but are not, the correct answer). To break memorization, beyond option shuffling, synonymous representations for both individual options and clinical entities within the questions can be substituted via autonomous means (e.g., via named entity recognition/entity linking). Issues of syntactic permutation of the same semantic content (Setting 2) can be resolved by symbolically permuting the syntax of the question in various manners (much as we do here in Setting 2) and giving a weighted accuracy score instead based on the agreement/correctness across these multiple permuted prompts. False-positive/hallucination rate (Setting 3) should be explicitly measured via the introduction of null-answer variants of the questions as we present here.

Fundamentally, however, the opacity in the training process and the very nature of public datasets, particularly within the clinical domain, where the availability of such datasets is limited, inherently suggests that any publicly available clinical benchmark dataset is likely to have been seen as part of the model training process. One approach to solving this problem, beyond introducing our permutations, is localizing the MCQA problems into real-world clinical cases from local EHRs with local data representations. Such an approach would serve the dual purpose of both making the assessment more reflective of local performance and sufficiently permute the syntax of the question to prevent memorization-based solves.

Collectively, these adaptations would likely help mitigate the memorization issue and serve as a relatively straightforward adaptation towards testing the application of retained knowledge towards problem solving, rather than rote repetition. We leave such investigations to future work.

Methods

Baseline assessments, models, and datasets

We establish the baseline accuracy of eight different models, five with “reasoning” capabilities (defined as the inclusion of reasoning processes during model training26,27: GPT-OSS-120B28, GPT-OSS-20B28, DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-70B26, DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-8B26, QwQ-32B29) and three without (LLaMA-3.3-70B-Instruct30, LLaMA-3.1-8B-Instruct30, Qwen-2.5-32B-Instruct31), on six different multiple-choice clinical assessment benchmarks. These three non-reasoning models were specifically selected as they are the base models from which reasoning versions are tuned (DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-70B, DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-8B, and QwQ-32B, respectively), ablating the reasoning process. Further, we select the R1/LLaMA-8B and GPT-OSS-120B/-20B models to ablate the influence of parameter sizes in both reasoning and non-reasoning models.

The current landscape of open-weight reasoning models inherently constrains which models can be used to perform our experiments. Parameter size ablation requires that the different models be from the same model family to ensure the training process/datasets are comparable (QwQ is only available as 32B parameters). Similarly, direct non-reasoning counterparts are not available for every reasoning model family (e.g., GPT-OSS). For example, while paired reasoning and base models exist for the DeepSeek R1–LLaMA series, no such pairing is available for GPT-OSS. While these groupings allow us to examine how reasoning capability and parameter scale may influence consistency, our analysis therefore aims to illustrate potential effects and implications rather than to exhaustively quantify their impact.

Our dataset selection is designed to align with that of the MedMultiQA collection, which is intended to broadly represent diverse medical examination questions spanning varying levels of difficulty. Specifically, the datasets assessed were the test subsets of the MMLU professional medicine dataset19,32, MedQA (USMLE Step 2&3 subset)18, MedMCQA (validation dataset, as test dataset labels were not available on HuggingFace)33, MedBullets34, the JAMA clinical challenge dataset34,35, and PubMedQA36. While PubMedQA results are reported within the supplementary information for completeness, its simplified yes/no/maybe 3-option multiple choice format and the incorporation of related passages within the prompt context make it unsuitable for our experiments by introducing additional challenges for GLMs relative to the other datasets. We therefore have excluded PubMedQA from the main comparative analyses.

A temperature of 0.6 (recommended default) was used for all models supporting the parameter. Each model’s “final answer” to a question is determined by a majority vote across five independently generated outputs. Responses that extended beyond one character were manually normalized (we opted not to use constrained decoding37 to avoid confounding influences on output generation). Situations where the output returns multiple answers, e.g., “A, B, or D,” are marked incorrect. In cases where generation results in a tie, the response is counted as a multiple-answer response. All other models were served through vLLM38 in native precision using eight NVIDIA H100 80GB GPUs.

To test consistency amid assumption invalidation, a set of questions that models were able to answer correctly was sampled. To control for varying question difficulty, we sample 100 questions from the intersection set of correctly answered questions from all models for subsequent experiments (using oversampling to reach 100 in the case of one dataset (MedBullets) due to the intersection of correct answers being 56). While this approach limits the total number of models that could be compared jointly, as additional models will reduce the difficulty of the sampled questions, it ensures that question difficulty is consistent across our various ablations.

Assessing reasoning fidelity and semantic consistency

We categorize our experiments into three experimental settings, observing answer consistency when each of the tested baseline assumptions are invalidated. Each setting is further divided into two sub-experiments, one retaining and one obfuscating or occluding contextual cues. Please refer to Fig. 1 for prompts used.

Setting 1: Data leakage/memorization amid expanded context spaces

Answer memorization is not a concern for human examinees due to question volume, but it is a concern for data-driven algorithms. Opacity on the data used for model training purposes raises significant concerns about answer memorization39,40. To assess whether this is occurring, we shuffle the options41. To obfuscate the context, we expand the search space from the 4-5 options present in the benchmark to an expanded search space of exactly 26 options (A-Z, to ablate the influence of multiple-choice option binding). Additional options are sampled from the MedQA train set with subsequent random shuffling (to move correct answers out of A-E). Manual review of mismatches was done for answers not in the original option set.

Setting 2: Answer consistency despite syntactic perturbations amid context clue removal

MCQA assessments assume that an examinee’s answers will be consistent given the same semantic information even if the syntax by which the question is posed changes. In this setting, we aim to assess the validity of this assumption by providing the answer as part of the prompt itself (alongside other possible options in the option list), permuting the question into a true/false assessment. To occlude this context, we truncate the other possible options from the prompt.

Setting 3: Statistical predisposition to positive answer matching amid prompt-implied context loss

MCQAs assume that knowledge is globally applicable to reasoning processes. Unlike human examinees, however, models rely on statistical predisposition to select answers by matching highly probable terms within provided options. To assess whether this assumption generalizes, we remove the correct answer from the listed multiple-choice options and replace it with “E. None of the above.”. For context obfuscation, the prompt being in the form of a multiple-choice question inherently predisposes models to look for the answer within the context of the A-E option list. To hide the correct answer from this implied context, we remove the option “none of the above” and instead insert an instruction to respond as such if none of the listed options listed A-C/D are correct.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using python (SciPy and StatsModels) with bootstrap-based non-parametric inference methods to account for the small number of replicates (1 replicate per “vote”/generation output, resulting in five per model per dataset for each experimental setting). For each experimental setting, model accuracies were averaged across replicates. Comparison was done in one of three ways: within the same model (e.g., before/after context occlusion/obfuscation) or across matched model pairs (e.g., reasoning vs. non-reasoning base), or against an expected 0% consistency loss. Within-model comparison was done using two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank testing supplemented with 10,000 iterations of bootstrap resampling. Cross-pair comparisons were done via two-sided Mann-Whitney U tests with the same bootstrap resampling approach. Comparisons against 0% consistency loss were done via a one-sided bootstrap and Wilcoxon test. When paired non-reasoning baselines were available, within-family reasoning effects were tested using paired Wilcoxon and bootstrap tests of per-dataset mean accuracies. To examine relationships between baseline accuracy, consistency, and inconsistency magnitude (Δ under context removal), Spearman rank correlations were computed. As each analysis (e.g., context manipulation) involved multiple hypothesis tests, p-values were corrected within each group of related tests using the Benjamini–Hochberg FDR procedure (\(\alpha\) = 0.05).

Data availability

All benchmarks used in this study are sourced from publicly available benchmarks. Due to individual license restrictions, we do not distribute these benchmarks with the code but have left instructions on how to obtain/format said datasets within our GitHub repository’s README (https://github.com/OHNLP/ContextVsReasoningMCQA).

Code availability

Code used for the experiments presented in this study can be found on GitHub, at https://github.com/OHNLP/ContextVsReasoningMCQA Note that it is expected that users possess their own OpenAI and HuggingFace tokens authorizing access to the respective models used in this study.

References

Thirunavukarasu, A. J. et al. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 29, 1930–1940 (2023).

Bedi, S. et al. Testing and evaluation of health care applications of large language models: a systematic review. JAMA 333, 319–328 (2025).

Yuan, J., Zhang, J., Wen, A. & Hu, X. The science of evaluating foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:250209670 (2025).

Yosinski, J., Clune, J., Bengio, Y. & Lipson, H. How transferable are features in deep neural networks? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 27, (2014).

Wang, A. et al. GLUE: A multi-task benchmark and analysis platform for natural language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Learning Representations (2019).

Devlin, J., Chang M.-W., Lee K. & Toutanova K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, volume 1 (long and short papers) 4171–4186 (2019).

Wei, Q. et al. Cost-aware active learning for named entity recognition in clinical text. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 26, 1314–1322 (2019).

Liu, J. & Wong, Z. S. Y. Utilizing active learning strategies in machine-assisted annotation for clinical named entity recognition: a comprehensive analysis considering annotation costs and target effectiveness. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 31, 2632–2640 (2024).

Schick, T. & Schütze, H. It’s not just size that matters: Small language models are also few-shot learners. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (2021).

Wang F. et al. A comprehensive survey of small language models in the era of large language models: Techniques, enhancements, applications, collaboration with LLMs, and trustworthiness. arXiv preprint arXiv:241103350 (2024).

Kim, H. et al. Small language models learn enhanced reasoning skills from medical textbooks. NPJ Digit Med 8, 240 (2025).

Qiu, J. et al. LLM-based agentic systems in medicine and healthcare. Nat. Mach. Intell. 6, 1418–1420 (2024).

Chang, C.-Y. et al. MAIN-RAG: Multi-agent filtering retrieval-augmented generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:250100332 (2024).

Zou, J. & Topol, E. J. The rise of agentic AI teammates in medicine. Lancet 405, 457 (2025).

Suura S. R. Agentic AI systems in organ health management: early detection of rejection in transplant patients. J. Neonatal Surg. 14. (2025).

Yang, J. et al. Harnessing the power of LMS in practice: A survey on ChatGPT and beyond. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 18, 1–32 (2024).

Haist, S. A., Katsufrakis, P. J. & Dillon, G. F. The evolution of the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE): Enhancing assessment of practice-related competencies. JAMA 310, 2245–2246 (2013).

Jin, D. et al. What disease does this patient have? A large-scale open domain question answering dataset from medical exams. Appl. Sci. 11, 6421 (2021).

Hendrycks, D. et al. Measuring massive multitask language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Learning Representations (2021).

Raji, I. D., Daneshjou R., Alsentzer, E. In It’s time to bench the medical exam benchmark. NEJM AI 2. https://doi.org/10.1056/AIe2401235.(2025).

Li, W. et al. Can multiple-choice questions really be useful in detecting the abilities of LLMs? Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (2024).

Matton, K., Ness, R., Guttag, J. & Kiciman, E. Walk the Talk? Measuring the faithfulness of large language model explanations. In The 13th International Conference on Learning Representations (2025).

Lanham, T. et al. Measuring faithfulness in chain-of-thought reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:230713702 (2023).

Gilson, A. et al. How does ChatGPT perform on the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE)? The implications of large language models for medical education and knowledge assessment. JMIR Med Educ. 9, e45312 (2023).

Yaneva, V., Baldwin, P., Jurich, D. P., Swygert, K. & Clauser, B. E. Examining ChatGPT performance on USMLE sample items and implications for assessment. Acad. Med 99, 192–197 (2024).

Guo, D. et al. Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in LLMs via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:250112948 (2025).

Jaech, A. et al. OpenAI O1 system card. arXiv preprint arXiv:241216720 (2024).

Agarwal, S. et al. gpt-oss-120b & gpt-oss-20b model card. arXiv preprint arXiv:250810925 (2025).

Qwen Team. Qwq-32b: Embracing the power of reinforcement learning. https://qwenlm.github.io/blog/qwq-32b (2025).

Grattafiori, A. et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint arXiv:240721783 (2024).

Yang, A. et al. Qwen2. 5 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:241215115 (2024).

Gema, A. P. et al. Are We Done with MMLU? arXiv preprint arXiv:240604127 (2024).

Pal, A., Umapathi, L. K. & Sankarasubbu, M. Medmcqa: A large-scale multi-subject multi-choice dataset for medical domain question answering. In Conference on health, inference, and learning: PMLR. 248–260.(2022).

Chen, H., Fang, Z., Singla, Y. & Dredze, M. Benchmarking large language models on answering and explaining challenging medical questions. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Volume I (Long Papers) 3563-3599 (2025).

Chang, H. J. Fontanarosa PB. Introducing. JAMA Clin. Chall. JAMA 305, 1910–1910 (2011).

Jin, Q., Dhingra, B., Liu, Z., Cohen, W. & Lu, X. Pubmedqa: A dataset for biomedical research question answering. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference On Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP)2567–2577. (2019).

Beurer-Kellner, L., Fischer, M. & Vechev, M. Guiding LLMs the right way: Fast, non-invasive constrained generation. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, Vol. 235, 3658–3673 (PMLR, 2024).

Kwon, W. et al. Efficient memory management for large language model serving with paged attention. In Proceedings of the 29th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles. 611–626 (2023).

Dong, Y. et al. Generalization or memorization: Data contamination and trustworthy evaluation for large language models. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024 (2024).

Sainz, O. et al NLP evaluation in trouble: On the need to measure LLM data contamination for each benchmark. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023 (2023).

Zong, Y., Yu, T., Chavhan, R., Zhao, B. & Hospedales, T. Fool your (vision and) language model with embarrassingly simple permutations. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Machine Learning (2024).

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01LM011934 and R01LM014508, the National Human Genome Research Institute under award number R01HG012748, the National Institute of Aging under award number R01AG072799, and the Cancer Prevention Institute of Texas (CPRIT) under award number RR230020. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Library of Medicine, the National Human Genome Research Institute, the National Institutes of Health, or the State of Texas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.W.: Study Conceptualization, Experimental Design, Experimental Implementation, Result Analysis, Result Interpretation, and Visualization. Q.L., Y.C., G.W., J.Y., J.Z., K.E.R., H.L.: Experimental Design, Result Interpretation. L.W., S.F., K.D.M., H.J., S.D.B., W.R.H., K.E.R., H.L.: Result Interpretation and Visualization. X.H., H.L.: Study Conceptualization and Leadership. All authors have reviewed and contributed expertise to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Author HL is an Editorial Board Member of npj Digital Medicine. They played no role in the peer review or decision to publish this paper. Author HL declares no financial competing interests. All other authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wen, A., Lu, Q., Chuang, YN. et al. Context matching is not reasoning when performing generalized clinical evaluation of generative language models. npj Digit. Med. 9, 71 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02253-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02253-2