Abstract

Excessive sodium intake is a major contributor to cardiovascular disease and mortality. Reducing daily sodium consumption to below 2 g (~5 g of salt) effectively lowers cardiovascular mortality rates. The growing reach of social media and short-form video content offers new opportunities to disseminate health information through scalable, digital interventions such as short, animated storytelling (SAS) videos. We evaluated the effect of a sodium-focused SAS video on knowledge and behavioral expectation to reduce dietary sodium, as well as measuring voluntary post-trial engagement. In this four-arm, parallel, randomized controlled trial, 8616 U.S. adults were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: (1) SAS video + survey, (2) survey only, (3) attention-placebo video + survey, or (4) no exposure. Participants completed follow-up surveys 2 weeks later. Single exposure to the SAS video significantly improved knowledge, both immediately and 2 weeks later, while increasing behavioral expectation to reduce sodium intake at both timepoints. Post-trial voluntary engagement with the intervention was high. These findings highlight the potential of scalable, digital storytelling interventions to enhance dietary knowledge and motivation for behavior change. Identifying demographic groups most likely to engage with SAS content may inform the design of targeted strategies to reduce cardiovascular risk. ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05735457, 02/21/23.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), including ischemic heart disease and stroke, remain among the five leading causes of morbidity and mortality in 190 countries in recent years1. Hypertension and unhealthy eating, including over-consumption of sodium, are among the most significant modifiable risk factors for CVD2,3,4. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified dietary sodium reduction as a critically important and cost-effective behavior change strategy for reducing CVDs and averting millions of preventable deaths globally5. In 2013, the WHO challenged its member states to reduce population sodium intake by 30%, by the year 20256. Well into 2025, the global average daily sodium intake was more than 4000 mg—twice the amount recommended by the WHO5.

Lack of public awareness about the major sources of sodium in the diet, and the dangers of excessive sodium intake, perpetuate this public health problem. Of note, many people are unaware of the disproportionately high contribution of processed foods to sodium intake. In a typical American diet, approximately 70% of daily sodium intake comes from processed foods, with only 5.6% originating from home-cooked meals7. Furthermore, while this is a long-standing problem in high-income countries, it is increasingly true in low- and middle-income countries as well5. Aggravating this lack of public awareness, a systematic review of global salt reduction initiatives, conducted as a midterm progress evaluation towards the WHO 2025 salt reduction target, documented a 30% decline in consumer sodium education programs across Europe, the Western Pacific, the Americas, the Eastern Mediterranean, Southeast Asia, and Africa6. This global drop off in national programs aimed at raising awareness about sodium intake, occurred in parallel with a global rise in strategies focusing on food reformulation, front-of-pack labeling, and taxation of high-sodium foods6.

Public health communication initiatives aimed at educating the public are often de-prioritized because they are considered resource- and time-intensive to create6. Historically, it has also been challenging to effectively disseminate public health messages and measure their impact in populations with low health literacy, low educational attainment, reduced access to healthcare and other risk-factors for poor dietary intake5.

While population-based sodium reduction initiatives have shown promise8, disseminating these equitably, to meet the public in ways that are accessible, engaging and readily scalable, has remained challenging. The rise of online health information-seeking opens new dissemination pathways, but even for some online distribution routes, social disparities have been observed9. Interestingly, health information disseminated via social media differs from health information-seeking driven by people’s intentions to seek information. Social media users are more likely to come across useful health information and share it with others, even without intentionally seeking that information10. This body of research culminates in calls to government and public health agencies to “produce and disseminate easy-to-understand educational programs on social media platforms so that even less educated people can benefit from them”9.

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed the emergence of an innovative approach to health communication that was both easy-to-understand and rapidly scalable. The approach uses short, animated storytelling (SAS) videos to disseminate accessible health information rapidly via social media11,12. Beyond pandemic-related messaging, recent trials have demonstrated the potential for SAS to increase health knowledge and behavioral intent to adopt health recommendations, enhance user satisfaction and promote voluntary engagement with health education interventions12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23.

In this study, we systematically evaluate the effect of a short (~3.5 min.) SAS video designed to convey essential knowledge about the major sources of sodium in the diet and the importance of limiting individual sodium consumption, on knowledge acquisition and behavioral intentions to reduce dietary sodium intake. This research will contribute to the existing literature on SAS video health education and inform future scalable, entertainment-education strategies aimed at delivering preventive health messages. Ultimately, the results of this study could guide the design and implementation of population-based initiatives focused on using scalable digital health interventions to boost knowledge and reduce dietary sodium consumption.

This study aimed to:

-

Measure the effect of an SAS video on knowledge about dietary sodium intake in both the short- and medium-term.

-

Measure the effect of an SAS video on behavioral expectation to reduce sodium consumption in both the short- and medium-term.

-

Measure voluntary engagement with the SAS video intervention.

We hypothesized that the SAS intervention video tested here would increase knowledge about dietary sodium in the short- and medium-term, with the expectation that knowledge may decrease during the 2-week follow-up phase. The protocol for this study was published before data collection began24.

Results

Study sample

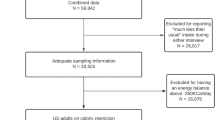

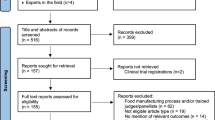

Through the Prolific Academic platform, 10,727 individuals were invited to participate in the study from June–July, 2024. Of those invited, 10,427 (97%) consented and were randomized into one of the four trial arms. Across the arms, 83% (N = 8612) returned after 2 weeks to complete the second part of the trial, which included follow-up surveys and post-trial voluntary access to the video interventions (81% in the SAS Sodium Intervention arm; 82% in the Attention Placebo Control [APC] arm; 85% in the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm; 83% in the Do-nothing Unexposed Control arm). These 8612 individuals were included in the analyses. Figure 1 shows the trial flow.

The participant characteristics, which are collected by Prolific when participants enroll, were balanced across the study arms (Table 1).

Study outcomes

At both the immediate and medium-term surveys, more than 99% of participants answered 4+ out of 5 attention check questions correctly, and these individuals were included in the analyses of the outcome scores. Accuracy in responding to attention checks is an important indicator of data quality in online human subjects research and inclusion of such checks is recommended in the literature25. The average study outcome scores by baseline participant characteristics are displayed in Supplementary Table 1, showing that the following demographic groups scored relatively higher on the baseline sodium knowledge survey: females, older age groups, participants identifying as white, and those in high education and income groups.

The immediate (T1) and follow-up (T2) scores across study arms for the primary outcome (sodium knowledge survey) and the secondary outcome (behavioral expectation to reduce sodium in the diet) are displayed in Fig. 2. The distributions show higher scores for these outcomes among people in the SAS Sodium Intervention arm at both time points, though slightly reduced at the follow-up time point (T2).

The unadjusted models for the effect of the SAS Sodium Intervention video on the primary outcome of sodium knowledge showed a 30.2% increase (95% CI: 29.2, 31.2) in the immediate survey score, and a 14.5% increase (95% CI: 13.6, 15.4) in the follow-up survey score, compared to the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm (Fig. 3). The APC arm scored the same as the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm at both the immediate and follow-up time points. As shown in Fig. 3, both of these control arms, which were exposed to the sodium questionnaire, without viewing the SAS Sodium Intervention video, had a slight (2%) up-tick in knowledge scores at T2 compared to T1 (2% increase [95% CI: 1.6, 2.7] for the APC arm and 2% increase [95% CI: 1.5, 2.5] for the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm).

Figure 3 also shows the observed effect of the SAS Sodium Intervention video on the secondary outcome of behavioral expectation to reduce sodium in the diet, revealing similar patterns to the primary outcome. Individuals in the SAS Sodium Intervention arm rated themselves higher on the scale of behavioral expectation to reduce sodium in their diet at the immediate survey (T1: 14.4% higher rating on scale; 95% CI: 11.9, 16.9) and at the follow-up survey (T2: 6.0% higher rating on scale; 95% CI: 3.7, 8.4) compared to individuals in the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm. The APC arm rated themselves the same as the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm at both the immediate and follow-up time points. As with the knowledge survey outcome, both of the control groups that were exposed to the sodium questionnaire, without having viewed the SAS Sodium Intervention video, had a slight (2–3%) boost in behavioral expectation scores at T2 compared to T1 (3% increase [95% CI: 1.6, 2.7] for the APC arm and 2% increase [95% CI: 1.5, 2.5] for the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm).

When examining scores on the sodium survey, by knowledge category, we found that individuals exposed to the SAS Sodium Intervention had a higher proportion of correct responses across the range of general knowledge questions (see Fig. 4).

Knowledge about health problems related to dietary sodium was already well-established at baseline for certain health problems, and therefore difficult to boost. For example, knowledge that sodium could contribute to high blood pressure was well-established across the study arms (99% correct in the SAS Sodium Intervention arm; 98% correct in the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm at T1). In contrast, the majority of participants, across study arms, falsely believed that dietary sodium was a significant contributor to elevated blood cholesterol levels, and this misconception was resistant to improvement, even after exposure to the intervention (with only 41% correct responses in the SAS Sodium Intervention arm and 37% correct responses in the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm at T1). We did observe a significant improvement in the intervention arm with regard to knowledge about the relationship between sodium and other unrelated health problems. For example, 80% of participants in the SAS Sodium Intervention arm correctly responded that sodium does not contribute to arthritis, compared with only 63% correct responses in the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm, at T1. Figure 4 shows percent correct responses by study arm for these knowledge areas.

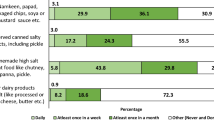

Regarding knowledge about the sodium content of foods, exposure to the intervention also resulted in significantly higher scores in the intervention group when compared with the control groups, especially for foods in which dietary sodium is a “hidden” component, such as frozen shrimp, breakfast cereals, breads and bagels. Respectively, the mean proportion of correct responses for these foods at T1 were: 88%, 94%, 95%, and 96% for the SAS Sodium Intervention arm, compared with 16%, 31%, 46%, and 49% in the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm (Fig. 5). In contrast, knowledge about the high sodium content of foods like “salty snacks” was already well-established at baseline (99% correct across arms at T1) so a ceiling effect was evident in the post-exposure scores. There was only one question for which the SAS Sodium Intervention arm scored worse than the Do-Nothing Exposed Control arm: correctly identifying frozen vegetables as a low sodium food (71% answered correctly in the SAS Sodium Intervention arm, compared with 89% in the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm, at T1). These findings are shown in Fig. 5.

In sensitivity analyses, modeling absolute effects of the study arms using linear regression and adjusting for participant demographics showed no difference in the direction or significance of the study outcomes. When we tested interaction effects for the impact of the SAS Sodium Intervention Video on sodium knowledge, we found the following trends: a positive interaction for younger age group, lower education group and independent/other political affiliation; a negative interaction for black ethnicity and being born outside the US.

Post-trial video engagement

Individuals in the APC and Do-nothing Unexposed Control arms were offered post-trial access to the SAS Sodium Intervention video after completing the final survey at T2. We define engagement as the length of time a participant chose to voluntarily watch the intervention video, from the first decision to click on the link. This data was collected directly on the Gorilla survey platform, where participants viewed the trial videos, allowing us to capture exact start and end times for each participant. In our sample, 64% began watching the video (watching 5 s or more), and 36% continued watching until the final scene (voluntarily watching 2 m:56 s or longer). Time spent voluntarily watching the SAS intervention is shown in Fig. 6.

Demographic characteristics associated with higher voluntary engagement included older age, non-white ethnicity, and lower income. In adjusted logistic regression models the odds ratios for watching the full video were: 2.32 (95% CI: 1.93, 2.77) for age 60+ vs. age 18–29; 1.48 (95% CI: 1.29, 1.69) for black vs. white ethnicity; and 0.74 (95% CI: 0.59, 0.94) for income of $150,000+ vs. <$20,000. There was no association between the sodium survey score at the immediate or the follow-up survey and the likelihood of watching the full sodium SAS video post-trial. However, individuals who rated themselves higher on their behavioral expectation to reduce dietary sodium were more likely to watch the SAS sodium video. Logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity and income showed that a one-point increase in the scale of expectation to reduce sodium consumption was associated with 7% higher odds (95% CI: 4, 9) of watching the video among study participants.

Discussion

This large-scale, online, parallel-arm, randomized controlled trial is the first of its kind to systematically measure the effect of a readily scalable, easy-to-understand, short, animated storytelling video on sodium knowledge and behavioral expectation to reduce sodium in the diet. Single exposure to this ~3 min intervention significantly increased sodium knowledge immediately after exposure and this effect remained significant 2 weeks later. Similarly, behavioral expectation to reduce sodium in the diet was significantly higher immediately after exposure to the SAS intervention and this effect also remained significant at the 2-week follow-up. In contrast to behavioral intention, behavioral expectation takes into account an individual’s informed expectations related to implementation barriers. As such, behavioral expectation has long been regarded as a better predictor of actual behavior change than behavioral intention26. Additionally, the absence of an observed effect in the APC arm and both of the other control arms, raises our confidence that the observed effect resulted directly from a single 3-min exposure to this accessible, scalable short video intervention.

Knowledge about certain health problems related to dietary sodium (like high blood pressure) as well as the high sodium content of obviously named foods (like “salty snacks”) were already well-established at baseline, so these scores were difficult to boost further through exposure to the intervention. However, the potential impact of the SAS approach to health communication was powerfully underscored by the substantial gains observed in knowledge about important, yet less widely known, sodium-related health facts (like the fact that processed foods constitute a significant source of dietary sodium). Related to this health message, we intentionally avoided the promotion of packaged foods marketed as “low sodium” due to documented concerns about the use of health claims to advertise some highly processed foods27. Instead, the intervention focused on gradually substituting packaged foods in the diet for foods cooked at home using mostly fresh ingredients. This approach aligns with recent research which has underscored the shortage of effective public health education interventions aimed at boosting North American consumers awareness about the high sodium content of processed foods. The same 2024 review emphasizes the need for novel strategies in this space, stating that these could have a profound impact on the health of Americans28.

Our results are consistent with prior randomized evaluations of SAS across health domains. In a UK online RCT targeting added sugars, exposure to a SAS video increased behavioral intent to reduce sugar intake23, supporting the capacity of SAS to shift proximal determinants of behavior. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a large online trial found that a wordless SAS video boosted knowledge and produced a measurable effect on one of five COVID-19 prevention behaviors12. Our engagement findings also align with prior SAS trials that measured voluntary, post-trial viewing. In the sugar reduction trial, ~66% of control-arm participants opted to watch the intervention video (mean view time ~116/222 s)19, and in the COVID-19 engagement study, ~72% opted in with an average view time of ~139/144 s18—patterns suggesting the capacity for SAS content to generate substantial voluntary engagement.

Importantly, low health literacy in certain US demographic groups, leaves them at greater risk for poor health outcomes. These groups are often the hardest to reach with traditional public health messages29,30,31. The positive interaction, observed in our study, among younger and less educated participant groups, as well as the observation that older and low-income adults were more likely to voluntarily watch the SAS video, suggest that accessible, readily scalable interventions, like SAS videos, may be especially beneficial for high-risk groups29,30,31. As older adults (aged 60+) increasingly frequent online platforms, tailored digital interventions for this age group could serve as important adjuncts to traditional health promotion efforts.

Interestingly, both of the control groups that were exposed to the sodium questionnaire at T1 showed slight increases (2–3%) in sodium knowledge at T2, despite that fact that they were not exposed to the SAS Sodium Intervention video. While these changes were not significant, the finding suggests that simply asking questions about dietary sodium can stimulate a degree of curiosity in the subject that supports independent exploration and small increases in knowledge. Future studies exploring the combination of SAS interventions and priming quizzes, could yield interesting findings.

The limitations of this study include the fact that the ProA participant population, while similar to the US population in terms of race and ethnicity, were skewed slightly more educated and slightly younger than the general US population. This is likely due to the fact that the ProA participant pool, by definition, is engaged online. However, because the intervention tested here is designed to be delivered online (to a target audience that already engages online) we feel that testing the intervention within the ProA population is appropriate. Among the major online participant recruitment platforms, ProA has been identified as a reliable recruitment platform, yielding high-quality data for online, academic research25. Secondly, the intervention was tested with an English-speaking, US-based population, so further studies are needed to test the approach in other geographies and other language groups.

Overall, the findings of this study highlight a promising, novel approach for the dissemination of accessible, easy-to-understand and readily scalable public health information about the relationship between dietary sodium and health. The high voluntary engagement and effectiveness of this digital health intervention, especially for high-risk, hard-to-reach groups, underscores the potential of short, animated storytelling to boost knowledge and health literacy about an important preventive health topic, especially given that CHD remains one of the leading causes of mortality. Additionally, the SAS approach could motivate behavior change, at scale, and future long-term studies are needed to rigorously test this prediction. As health policy-makers and public health advocates search for innovative ways to communicate important health messages to a public that is increasingly engaged online, consuming short-form video content, short, animated storytelling videos, focused on promoting health, could play a meaningful supporting role.

Methods

Study design

We designed a randomized controlled parallel-group trial that examined the effect of a short, animated storytelling (SAS) video on knowledge and behavioral expectation to reduce dietary sodium intake. We recruited 10,000 participants aged 18–59 years through the online academic research platform (Prolific Academic) and randomized them into four study arms.

Participants randomized to Arm 1 (SAS Sodium Intervention arm), viewed the 3.5 min SAS video intervention, focused on dietary sodium (see Supplementary Movies 1 and 2) and subsequently completed a survey designed to assess their knowledge of dietary sodium and their behavioral expectations to reduce sodium intake, reduce processed food consumption and cook more at home—all recommended strategies for the prevention of CVDs5.

Participants randomized to Arm 2 (Do-Nothing Exposed Control arm) completed the same knowledge and behavioral expectation survey as Arm 1, without prior exposure to the SAS video.

Participants randomized to Arm 3 (Attention Placebo Control [APC] arm), viewed an attention placebo control (APC) video, which was also a 2D animated film, but unrelated to the trial’s outcomes, before completing the knowledge and behavioral expectation survey.

Participants in randomized to Arm 4 (Do-nothing Unexposed Control arm) received no intervention and were not asked to complete the survey at the first data collection time point.

Two weeks later, all four arms were invited to return and complete the same knowledge and behavioral expectation survey.

Study setting, participants and eligibility

This study was conducted entirely online. Participants from the USA were recruited through the Prolific Academic platform (ProA; https://www.prolific.co). Eligible participants (all genders) were between the ages of 18 and 59 years and living in the US. No additional inclusion or exclusion criteria were applied. Random allocation, delivery of the video intervention and completion of the survey were all conducted on the secure online experiment-builder platform, Gorilla (www.gorilla.sc). The Gorilla platform is frequently used by academic researchers to conduct online behavioral research24.

Intervention description

The SAS intervention tested in this study is a short, 2D animated storytelling video following classical three-act structure, and incorporating the major “story beats” used in the entertainment industry to engage audiences32. Figure 7 illustrates these beats with corresponding scenes from the intervention mapped along the three-act story structure. The SAS intervention conveys a humorous story in which a sleeping protagonist (set-up) is awakened by his own heart (the inciting event), before being informed that his heart plans to quit because the heart is under too much pressure. The heart goes on to explain the origins of that pressure (rising action), culminating in a plea to his owner to avoid the consequences of excess sodium in the diet (midpoint). The protagonist, in despair, worries that there will be nothing left for him to eat (dark night of the soul) but the heart explains the concrete actions his owner can take to reduce dietary sodium, including reading labels, avoiding processed foods and cooking more at home. This leads to the protagonist promising to change if the heart promises not to quit (resolution). Finally, the heart reveals his dedication to the protagonist before the protagonist wakes up from this unsettling dream (high-tower surprise). At the end of the 3:09 min video, we see the protagonist cooking breakfast (new normal) as his partner watches with curiosity, taking in the seemingly overnight change (see Supplementary Movie 1).

The APC video was a 2D animated storytelling video which portrays a fantasy tale about a dragon who has forgotten to fly and must gather a team to help a special friend in need, before he once again finds his purpose and, with it, his wings. The video conveys general messages about hope, friendship and gratitude (see Supplementary Movie 2). As recommended in the selection of appropriate APCs, this video was of a similar length (3:29 min) and intended to stimulate participants’ engagement, without conveying information related to the main outcomes33.

Rationale for choice of comparators

Comparing primary and secondary outcomes between the three study arms that completed surveys (the SAS Sodium Intervention arm, the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm and the APC arm), at time point 1, allowed us to determine the immediate effect of the SAS intervention on knowledge and behavioral expectation to reduce sodium. Our primary comparison was between the intervention arm and the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm. We then compared these groups with the APC arm to exclude the possibility of a generalized attention-activation effect associated with viewing an animated short film of similar length, but with no references to sodium intake or dietary behaviors.

Comparing primary and secondary outcomes between the intervention arm and the Do-nothing Unexposed Control arm, at time point 2, allowed us to determine the medium-term effect of the SAS intervention on knowledge and behavioral expectation to reduce sodium intake. Because the Do-nothing Unexposed Control arm had seen neither videos nor surveys, comparing the outcomes of this arm with the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm allowed us to detect any potential priming effect that could have resulted just from exposure to the survey questions about sodium in various foods and behavioral expectation to adopt sodium-reducing dietary behaviors.

Outcomes and measurement tools

The primary outcome measured in our study was the effect of an SAS video intervention on knowledge about dietary sodium, measured immediately after exposure and in the medium term (2 weeks later). To date, the only validated sodium questionnaire was developed in 2014 and validated on a small sample of 41 nutrition experts, 32 nutrition students and 36 members of the general public34. The questionnaire is outdated and lacks adequate focus on contemporary processed foods, which are major contributors to dietary sodium. For this reason, we developed a sodium knowledge questionnaire, with input from cardiologists and nutrition science experts at Freiburg University Hospital and the Stanford University School of Medicine and used this survey (Supplementary Table 2) to measure knowledge about dietary sodium in this study, across study arms. The secondary outcome measured in our study was the effect of an SAS video intervention on behavioral expectation to reduce sodium intake, measured using a 10-point behavioral expectation scale, immediately after exposure and 2 weeks later. Behavioral expectation scales have been recommended in the literature, over self-reported behavioral intention scales, because they take into account individual barriers to adoption and are therefore considered to be superior predictors of self-reported performance26. Participants in this study were asked to respond to the following behavioral expectation prompt: “All things considered, how likely are you to reduce sodium in your diet in the next 2 weeks?” on a scale from 1–10.” Finally, voluntary engagement with the SAS video intervention was measured by calculating the percentage of participants who chose to engage with the video during the post-trial access phase. We also measured engagement at the participant-level by capturing the length of engagement time (total length of video viewing) for each individual participant.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the distribution of the participants’ demographic factors by study arm, which were available through the Prolific Academic platform and included the following: age, sex, education, ethnicity, country of birth, language, household income, political affiliation, student status, and presence of a long-term health condition or disability.

For the primary outcome, score on the 31-item sodium knowledge survey, we calculated the sum of correct responses for each participant. Individuals were only included in the analysis of the outcomes if they responded correctly to at least 4 out of 5 attention-check questions. Distributions and means of the scores for the primary and secondary outcome were examined by demographic characteristics, and compared between the SAS Sodium Intervention arm, the APC arm, and the Do-nothing Exposed Control arm at time point 1, as well as between all four study arms at time point 2.

The primary analysis used unadjusted regression to model relative effects of the intervention arm assignment on the outcome scores, comparing across arms at T1 (immediate), at T2 (2-week follow-up), and change within arms from T1 to T2. To obtain relative effects we used generalized linear models with a log link and Gaussian distribution to estimate the proportional difference in outcomes for each group relative to the reference group. For models examining change over time, we accounted for individual-level random effects with mixed models. In sensitivity analyses, we modeled the absolute effects of study arm on the outcomes using linear regression and linear mixed models, and we controlled for demographic characteristics. In a separate set of models, we included interaction terms to analyze if the impact of the intervention differed by demographic characteristics. Analyses were conducted using the STATA statistical software package (STATA 17.0).

Sample size calculation, recruitment and adherence strategies

The sample size necessary to compare mean outcomes between the four study arms was calculated independently for our primary and secondary outcomes. This calculation was based on the mean score of each survey and the most conservative sample size was selected. The highest possible score on the sodium knowledge survey was 31, if all questions were answered correctly. Because this was a new survey, we did not have prior data on mean scores and variability in similar populations, so we could not directly estimate effect size for this measurement tool. Since we were measuring the effect of a single exposure to a very short (~3 min) intervention, which would ideally be watched several times (in practice) to achieve consistent change, we aimed to capture a small change in mean scores, assuming that such small changes could be converted into larger changes through repeated exposure. Therefore, this study was powered to detect a small effect size in comparisons of mean scores between study arms, (d = 0.1), which is smaller than the general threshold for detecting an effect35. The sample size formula for one-tailed comparison of mean scores, with equal variance, and a type I error of 0.01, was used to account for multiple comparisons, and a power of 80% was used to detect changes in mean scores. These calculations yielded a sample size of 2009 participants per study arm. We anticipated an attrition rate of 20% (based on prior similar studies conducted on ProA)36,37,38 and this resulted in a sample size of 2410 participants per arm. As such, we aimed to recruit 2500 participants per arm (10,000 participants in total) allowing us to detect intervention effects with a power higher than 80%.

Using an online academic recruitment platform, (ProA), guaranteed adequate participant enrollment and allowed us to offer payment to participants ($3.95 per participant), as the main strategy for promoting adherence and retention. Sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, relevant concomitant care, criteria for discontinuing the trial, provisions for post-trial care, methods for handling protocol non-adherence, data management and our anticipated timeline are described in detail in the published protocol for this trial24.

Ethics

Ethical clearance for conducting this study was obtained from the Stanford University Institutional Review Board (IRB) on June 7, 2022 (protocol #65160), and a modification to this protocol was approved on February 6, 2023. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided informed electronic consent before enrollment. Trial registration: the trial was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05735457) on February 21, 2023.

Data availability

All data and the interventions developed for this study are available, in a fully anonymized format, upon request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Analysis scripts used for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ferrari, A. J. et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 403, 2133–2161 (2024).

Kim, B. S., Yu, M.-Y. & Shin, J. Effect of low sodium and high potassium diet on lowering blood pressure and cardiovascular events. Clin. Hypertens. 30, 2 (2024).

Ma, H., Wang, X., Li, X., Heianza, Y. & Qi, L. Adding salt to foods and risk of cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 80, 2157–2167 (2022).

Vaduganathan, M., Mensah, G. A., Turco, J. V., Fuster, V. & Roth, G. A. The global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk: a compass for future health. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 80, 2361–2371 (2022).

World Health Organization. WHO Global Report on Sodium Intake Reduction. Report No. 9240069984 (World Health Organization, 2023).

Santos, J. A. et al. A systematic review of salt reduction initiatives around the world: a midterm evaluation of progress towards the 2025 global non-communicable diseases salt reduction target. Adv. Nutr. 12, 1768–1780 (2021).

Harnack, L. J. et al. Sources of sodium in US adults from 3 geographic regions. Circulation 135, 1775–1783 (2017).

Barberio, A. M. et al. Population-level interventions in government jurisdictions for dietary sodium reduction: a Cochrane review. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 1551–1405 (2017).

Yang, S., Lee, C. -j & Beak, J. Social disparities in online health-related activities and social support: findings from health information national trends survey. Health Commun. 38, 1293–1304 (2023).

De Choudhury, M., Morris, M. R. & White, R. W. Seeking and sharing health information online: comparing search engines and social media. In Proc. SIGCHI Conf. Hum. Factors Comput. Syst. 14, 1365–1376 (ACM, 2014).

Adam, M., Bärnighausen, T. & McMahon, S. A. Design for extreme scalability: a wordless, globally scalable COVID-19 prevention animation for rapid public health communication. J. Glob. Health 10, 343 (2020).

Vandormael, A. et al. The effect of a wordless, animated, social media video intervention on COVID-19 prevention: online randomized controlled trial. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 7, e29060 (2021).

Adam, M. et al. Effect of short, animated storytelling, conveying the lived experiences of a mother vs a father of a trans child, on transphobia among US parents: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Transgender Health 26, 1–13 (2025).

Adam, M. et al. Short, animated storytelling video to reduce addiction stigma in 13,500 participants across multiple countries through an online approach: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 14, e73382 (2025).

Adam, M. et al. Effect of short, animated video storytelling on maternal knowledge and satisfaction in the perinatal period in South Africa: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e47266 (2023).

Amsalem, D., Greuel, M., Liu, S., Martin, A. & Adam, M. Effect of a short, animated storytelling video on transphobia among US parents: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 11, e66496 (2025).

Beleites, F. et al. Evaluating the impact of short animated videos on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: an online randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv. 35, 100694 (2024).

Favaretti, C. et al. Participant engagement with a short, wordless, animated video on COVID-19 prevention: a multi-site randomized trial. Health Promot. Int. 36, daab179 (2021).

Favaretti, C. et al. Participant engagement and reactance to a short, animated video about added sugars: web-based randomized controlled trial. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 8, e29669 (2022).

Greuel, M. et al. Parent engagement with a short, animated storytelling video aimed at reducing stigma towards transgender children and adolescents: a post-trial assessment of a randomized controlled. Trial SSM Ment. Health 7, 100410 (2025).

Liu, S. et al. Evidence-based health messages increase intention to cope with loneliness in Germany: a randomized controlled online trial. NPJ Digital Med. 7, 105 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. An entertainment-education video and written messages to alleviate loneliness in Germany: pilot randomized controlled study. JMIR Form. Res. 7, e43036 (2023).

Vandormael, A. et al. Effect of a story-based, animated video to reduce added sugar consumption: a web-based randomized controlled trial. J. Global Health 11, 04064 (2021).

Supady, A. et al. A short, animated storytelling video about sodium intake as a major cardiovascular risk factor and recommendations for a healthy diet: an online, randomized, controlled trial. Trials 24, 390 (2023).

Douglas, B. D., Ewell, P. J. & Brauer, M. Data quality in online human-subjects research: comparisons between MTurk, Prolific, CloudResearch, Qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS ONE 18, e0279720 (2023).

Warshaw, P. R. & Davis, F. D. Disentangling behavioral intention and behavioral expectation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 21, 213–228 (1985).

Monteiro, C. A. et al. Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 22, 936–941 (2019).

Trumbo, P. R. et al. North American considerations, strategies, and practices in reducing the sodium content in processed foods. J. Food Sci. 89, 6086–6097 (2024).

Fleary, S. A. & Ettienne, R. Social disparities in health literacy in the United States. Health Lit. Res. Pract. 3, e47–e52 (2019).

Patil, U. et al. Health literacy, digital health literacy, and COVID-19 pandemic attitudes and behaviors in US college students: implications for interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 3301 (2021).

Shahid, R. et al. Impact of low health literacy on patients’ health outcomes: a multicenter cohort study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22, 1148 (2022).

Zagalo, N., Oliveira, A. P., Cardoso, P. & Vairinhos, M. Beats & units: a story-game design framework. Int. J. Film. Media Arts 8, 52–67 (2023).

Popp, L. & Schneider, S. Attention placebo control in randomized controlled trials of psychosocial interventions: theory and practice. Trials 16, 1–3 (2015).

Sarmugam, R., Worsley, A. & Flood, V. Development and validation of a salt knowledge questionnaire. Public Health Nutr. 17, 1061–1068 (2014).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Routledge, 2013).

Amsalem, D., Halloran, J., Penque, B., Celentano, J. & Martin, A. Effect of a brief social contact video on transphobia and depression-related stigma among adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e220376 (2022).

Amsalem, D. et al. Selfie videos to reduce stigma and increase treatment seeking among youths: two noninferiority randomized controlled trials. Psychiatr. Serv. 74, 20220168 (2022).

Amsalem, D. et al. Sustained effect of a brief video in reducing public stigma toward individuals with psychosis: a randomized controlled trial of young adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 178, 635–642 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the creative team. David Makadi animated the SAS intervention video under the direction of M.A. Matt Torode animated the APC video, with scenes developed by CBA animation, led by Chaz Bottoms. We wish to thank Misha Seeff, the teenage musician who composed (APC) and arranged (Intervention) soundtracks for the videos tested here. We also wish to acknowledge our advisors, Michelle Williams, at the Stanford University School of Medicine, and Shekhar Saxena, at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health as well as the Stanford Medicine Communications Team. The study was funded by the Heidelberg Institute of Global Health at Heidelberg University Hospital in Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. created the intervention and APC videos, led the study design, obtained ethics approval from Stanford University, and led the writing of the final manuscript. J.K.R. led the data analysis, interpretation and presentation of results, as well as co-writing and editing the final manuscript. M.G. built the online experiment and implemented the study, helped to interpret the results, as well as editing the final manuscript. K.N. conducted the sample size calculation, led the building of the initial online surveys participated in the study design discussions and drafted the statistical analysis portions of the protocol together with co-author, M.A.E. M.A.E. conducted the sample size calculation, participated in the study design discussions, and drafted the statistical analysis portions of the protocol together with co-author, K.N. C.U. participated extensively in the study design phase, edited the protocol and participated in the testing of the online experiment. O.C. conducted the literature review, revised the study questionnaires, edited the protocol, and participated in the manuscript development. T.B. (co-senior author) supervised the study design, advised extensively on the intervention development and statistical analysis plan, and edited the paper. A.S. supervised the study design, registered the trial, advised extensively on the statistical analysis plan, and edited the paper. T.B. and A.S. contributed equally.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adam, M., Rohr, J.K., Greuel, M. et al. Digital storytelling boosts knowledge and behavioral expectation to reduce dietary sodium: a randomized controlled trial. npj Digit. Med. 9, 21 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02258-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02258-x