Abstract

Vascular invasion assessment is critical for surgical planning in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Current CT-based assessments often rely on radiologists’ subjective 2D interpretations, which may not capture the continuous, three-dimensional tumor–vessel interactions and multiple vessel involvement, both essential for accurate preoperative evaluation. PAN-VIQ (Pancreatic Vascular Invasion Quantifier) is an automated deep learning framework to quantify tumor–vessel interactions from contrast-enhanced CT scans. It enables segmentation of pancreatic tumors and five critical vessels: celiac artery (CA), common hepatic artery (CHA), superior mesenteric artery (SMA), superior mesenteric vein (SMV), and portal vein (PV), quantifying vascular involvement through 3D encasement angles. PAN-VIQ was trained and internally validated on 2130 cases, and subsequently prospectively tested in 202 patients. External validation showed accuracies exceeding 90%. In prospective evaluation, the model outperformed junior radiologists and matched senior radiologists in accuracy and recall. These results underscore potential of PAN-VIQ to standardize vascular invasion assessment and reduce interobserver variability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the most lethal malignancies1, and despite recent advancements, survival rates have seen minimal improvement over the past few decades. As a result, PDAC is projected to become the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths within the next decade2. Surgical resection remains the only potentially curative intervention; however, only approximately 15–20% of patients are eligible for resection with curative intent at the time of diagnosis3,4,5. Assessment of vascular involvement, particularly the degree of tumor contact with critical arteries and veins, is pivotal for determining prognosis and guiding treatment strategies6. Preoperative knowledge of vascular invasion status allows for better surgical planning, helping reduce the risk of positive margins, anticipate the need for vascular reconstruction, and avoid intraoperative surprises that may necessitate unplanned or extended procedures7,8,9.

Despite the widespread use of contrast-enhanced CT and the availability of standardized assessment criteria, preoperative evaluation of vascular involvement in PDAC remains hindered by considerable interobserver variability10,11,12. Radiologists often rely on visual interpretation to assess tumor-vessel proximity and reference guideline-defined angular criteria, when characterizing vascular involvement13. However, in clinical practice, the application of these criteria is subject to individual interpretation, especially in anatomically ambiguous regions, leading to inconsistent assessments across observers. Moreover, fixed angle cutoffs may not fully account for the heterogeneous clinical implications associated with different vascular structures. For instance, arterial involvement, especially of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), may raise operative complexity even at lower degrees of encasement14, while venous invasion, including extensive wrapping of the portal vein or SMV, can often be managed surgically with reconstruction15. This heterogeneity challenges the validity of applying a uniform angle criterion across all vessels. Moreover, the absence of continuous, objective quantification contributes to substantial interobserver variability, particularly among less experienced radiologists and hampers precise treatment planning16,17. Studies have shown that vascular invasion probability rises steeply from 40% at <180° to over 80% at ≥180°, highlighting how rigid categories may obscure biologically meaningful transitions18,19,20. These limitations underscore the need for a quantitative, anatomically precise, and vessel-specific approach to vascular invasion assessment.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning and radiomics, have significantly improved diagnostic precision and preoperative evaluation in PDAC, enabling high-throughput CT analysis for more accurate staging, differential diagnosis, and lymph node assessment21,22,23,24,25. Building on this, recent studies6,26,27,28,29 have made important advances in applying artificial intelligence to assess vascular involvement in PDAC, demonstrating promising performance in segmenting anatomical structures and predicting vessel invasion. However, most existing models remain constrained in several important ways. First, many are limited to binary or ordinal classification of tumor–vessel contact (e.g., <180° vs. ≥180°), which cannot capture the continuous, three-dimensional nature of tumor encasement or its vessel-specific clinical implications26,27,28. Second, Prior studies have often concentrated on a single-vessel approach, most commonly focusing on the superior mesenteric artery or portal vein, without addressing the fact that PDAC frequently involves multiple major vessels. In clinical practice, multiple vessels may be simultaneously surrounded by the tumor, which adds significant complexity to surgical planning. As a result, relying on a single-vessel analysis overlooks this anatomical reality, potentially leading to an incomplete assessment of vascular involvement and affecting critical decisions regarding resectability and the need for vascular reconstruction6,26,29. Third, most models rely on manual segmentation or non-standardized definitions of invasion, and few support automated, reproducible, and anatomically grounded quantification of tumor–vessel geometry26,27,28. These limitations reduce the interpretability of model outputs and restrict their integration into preoperative planning or individualized treatment decision-making. A more comprehensive and objective framework is needed to support consistent assessment across vessels, patients, and institutions.

To address these limitations, we developed PAN-VIQ (Pancreatic Vascular Invasion Quantifier), a deep learning–enabled framework designed to automatically quantify the three-dimensional anatomical relationships between pancreatic tumors and major peripancreatic vessels from contrast-enhanced CT imaging. PAN-VIQ enables fully automated segmentation of pancreatic tumors and five key vascular structures: the celiac artery (CA), common hepatic artery (CHA), superior mesenteric artery (SMA), superior mesenteric vein (SMV), and portal vein (PV). This multi-vessel approach overcomes the limitations of single-vessel studies, offering a more comprehensive assessment of vascular involvement in clinical scenarios characterized by multi-vessel tumor encasement. The spatial relationship between tumor and each vessel is assessed from volumetric segmentation in the coronal plane, allowing precise computation of continuous three-dimensional encasement angles. These geometric metrics are quantitatively defined and interpretable as continuous anatomical measurements that can be contextualized relative to known clinical thresholds for tumor–vessel contact. By replacing subjective visual estimates with standardized, numerically grounded outputs, PAN-VIQ enhances the consistency and transparency of tumor–vessel anatomy evaluation across institutions. Trained and validated on a multicenter cohort exceeding 2,000 patients, the framework provides interpretable and anatomically accurate measurements that support standardized vascular assessment in diverse clinical environments.

Results

Patient characteristics

Figure 1 presents a schematic illustration of the overall study design. Data from 2130 patients across four hospitals were used for model development and internal validation. External validation included datasets from three additional hospitals: Dataset 1 (30 patients), Dataset 2 (85 patients), and Dataset 3 (54 patients). In the prospective phase (January–December 2024), 202 patients met inclusion criteria. Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1.

A Overall pipeline of PAN-VIQ: The model receives dual-phase (arterial and portal venous) CT images as input, performs tumor–vessel segmentation, and computes continuous encasement angles at tumor–vessel interfaces. Outputs include both continuous values (e.g., 38°) and categorical classifications (e.g., contact <180°). Model performance is benchmarked against intraoperative findings and radiologist interpretation. B Step 1: Training and validation of the three-stage segmentation model. The model was iteratively trained via a hybrid strategy comprising supervised pretraining, semi-supervised tuning, structural refinement, and post-processing. Manual review and correction by radiologists were performed after each stage to improve robustness and anatomical accuracy. C Step 2: Establishment of the vascular invasion quantification model. The vessel centerline (AB) was extracted. For each centerline point O, a local 2D plane CDEF orthogonal to the centerline tangent at O was generated, and the tumor/vessel masks were resampled onto this plane to obtain cross-sections. On CDEF, the boundary intersections between the tumor and vessel cross-sections were labeled b and c, and the centroid of the tumor cross-section was denoted a. The wrapping angle was defined as ∠bac, representing the degree of circumferential tumor involvement. D Step 3: Evaluation and validation of PAN-VIQ. Retrospective validation included 1759 internal cases and 164 external cases across three hospitals. Prospective validation was performed in 202 newly recruited patients, with model predictions compared to assessments by junior and senior radiologists, and benchmarked against surgical findings. E Patient cohort flowchart: The training, validation, and testing datasets were derived from 2130 patients with pathologically confirmed PDAC. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed for both internal and external cohorts.

For vascular invasion, 53 of 194 patients (27.3%) had SMA involvement in the training cohort. of these, 48 patients had tumor encasement angles ≤180°, while 5 patients had tumor encasement angles >180°. In the total external validation cohort of 169 patients, 52 patients (30.8%) demonstrated SMA involvement, with 46 patients showing tumor encasement angles ≤180° and 6 patients presenting tumor encasement angles >180°. A significant difference in the distribution of SMA invasion was observed when comparing the external validation cohort to the training set (p = 0.002). For the other vessels (CA, CHA, SMV, PV), no significant inter-cohort differences were observed in the distribution of vascular invasion (all p > 0.05; Table 1).

Among the 1961 patients, 311 (15.86%) exhibited vascular variations. The most common anomaly was the right hepatic artery arising from the SMA, observed in 93 cases. This was followed by 59 cases where the left hepatic artery originated from the left gastric artery, and 34 cases where the left hepatic artery also arose from the left gastric artery. Less common variations included 16 cases where the left gastric artery arose from the abdominal aorta, and 14 cases of the right hepatic artery originating from the celiac trunk. Rarer variations included co-dominance of the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery, the right hepatic artery arising from the common hepatic artery, and the right hepatic artery originating from the gastroduodenal artery or the bifurcation of the celiac trunk. The influence of vascular variations on the performance of PAN-VIQ was evaluated by comparing patients with and without vascular variations. For the SMA, dice similarity coefficient (DSC) was 0.858 (0.796–0.930) in the variation group and 0.878 (0.812–0.940) in the non-variation group (p = 0.284). For the CHA, DSC were 0.732 (0.646–0.821) versus 0.743 (0.660–0.830) (p = 0.420). In addition, comparison of predicted vascular invasion between patients with and without vascular variations revealed no statistically significant differences for either vessel (CHA, p = 0.417; SMA, p = 0.609; Fisher’s exact test).

PAN-VIQ segmentation performance

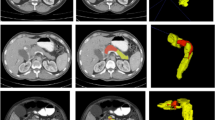

The PAN-VIQ segmentation model was developed using the adaptive segmentation framework, which automatically configures network architecture (Fig. S1) and training pipelines based on dataset-specific characteristics. To improve anatomical fidelity and ensure generalizability across diverse imaging conditions, we implemented a three-phase progressive training strategy, gradually expanding the dataset and incorporating expert refinements. Segmentation was conducted separately for arterial and portal venous phases to match vessel-specific enhancement patterns. Arteries (CA, CHA, SMA) were delineated from arterial-phase scans, and veins (SMV, PV) from portal venous-phase scans. Representative segmentation outputs across the three progressive training phases are shown in Fig. 2, demonstrating stepwise improvements in anatomical delineation of tumors and vessels. Typical deficiencies in Phases 1 and 2, such as incomplete tumor coverage, vessel mask discontinuity (as illustrated Figs. S2 and S3), and incorrect boundary attribution, were incrementally corrected following semi-supervised refinement and expert-guided annotation updates, culminating in improved anatomical coherence and spatial accuracy in Phase 3. Model performance, summarized in Table S2, demonstrated consistently high accuracy across internal and external cohorts. For tumor segmentation, Dice similarity coefficients (DSC) reached 0.853 (internal) and 0.789 (external); among vessels, the SMA achieved the highest accuracy (DSC 0.871, sensitivity 0.983). In the portal venous phase, SMV and PV segmentation yielded DSCs of 0.789 and 0.862 internally, and 0.741 and 0.756 externally.

Axial CT images from representative cases demonstrate segmentation performance across six anatomical structures: A pancreatic tumor (arterial phase), B celiac artery (CA), C common hepatic artery (CHA), D superior mesenteric artery (SMA), E pancreatic tumor (portal venous phase), F superior mesenteric vein (SMV), and G portal vein (PV). Each column shows the original CT image, outputs from Phase 1 (initial supervised model), Phase 2 (semi-supervised refinement), Phase 3 (final model with expert-guided correction), and the expert-annotated ground truth. Insets in the lower-left corners display corresponding 3D reconstructions. White boxes highlight segmentation deficiencies observed in early training phases, including incomplete tumor contouring (A, E), inclusion of adjacent non-target tissue (B), and topological discontinuities at vascular branching points or along the vessel course (C, D, F, G). In Panel E, arrows indicate false-positive regions incorrectly segmented outside the tumor boundary in the 3D view. These examples illustrate progressive improvements in boundary completeness, vascular continuity, and spatial accuracy following iterative training with expert-in-the-loop annotation.

Radiologists independently assessed segmentation quality, indicating strong reliability (Cohen’s Kappa ≥ 0.689). Tumor segmentation scored 4.32 ± 1.06 (arterial) and 4.56 ± 0.94 (venous), with Kappa of 0.754. CA and SMA had the highest consistency (Kappa 0.789 and 0.812, respectively). CHA segmentation showed moderate variability (score: 3.72 ± 1.37, Kappa: 0.654). SMV and PV showed good consistency (Kappa: 0.689 and 0.735). Full details are shown in Table S3.

Retrospective validation: vascular invasion quantification

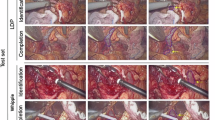

PAN-VIQ performed robustly in internal validation, notably in Class 1, achieving accuracies for CA (97.54%), CHA (95.87%), SMA (94.38%), SMV (93.30%), and PV (90.82%). Performance remained high in Classes 2 and 3, despite slightly lower accuracy (e.g., CA 74.29% in Class 3). External validation confirmed high generalizability, particularly for CA (95.93%) and SMA (97.01%). Precision, recall, and specificity remained consistently high across classes, affirming model robustness. As illustrated in Fig. 3, conventional assessments of tumor–vessel contact either rely on single-slice visual estimation or manual point placement in 3D space, both of which may introduce inconsistency. In contrast, PAN-VIQ provides fully automated, geometrically consistent angle calculations across reconstructed planes.

A Manual 2D estimation on a single axial CT slice (α = 121°), simulating conventional radiologic evaluation. Clinicians typically select the slice with maximal apparent tumor–vessel contact and visually estimate the angle of encasement. Tumor and vessel masks are shown in red and cyan, respectively. This method is constrained to a single imaging plane. B Semi-automated 3D measurement using conventional software (θ = 154.4°). Radiologists place three reference points (P0–P2) along the tumor–vessel interface to compute the encasement angle in three-dimensional space. Although this approach allows multi-planar assessment, the measurement relies on manually selected reference points, which may be influenced by user input variability. C Fully automated angle quantification using PAN-VIQ (β = 172.4°). The model automatically identifies the region of maximal tumor–vessel interaction and calculates the encasement angle on a reconstructed 3D plane. Two perspectives are shown to illustrate geometric consistency. Tumor is rendered in red, vessels in green.

To further visualize model classification performance, radar plots (Fig. 4) summarize key metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, specificity, and F1 score, across five major peripancreatic vessels in both internal and external validation cohorts. The model exhibited consistently high specificity across all vessels and settings, while minor declines in recall and F1 score were observed for CHA and SMV in external datasets. Corresponding confusion matrices are shown in Figs. S5 and S6, illustrating the distribution of predicted labels for each vessel category and further supporting the robust classification performance across variable imaging conditions.

This figure presents the classification performance of PAN-VIQ for five peripancreatic vessels, including the celiac artery (CA), common hepatic artery (CHA), superior mesenteric artery (SMA), superior mesenteric vein (SMV), and portal vein (PV), using radar plots to visualize five key evaluation metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and specificity. Panel A displays the results from the internal validation cohort comprising 2130 patients. Panel B illustrates performance across three independent external datasets with sample sizes of 169, respectively.

Prospective validation: vascular invasion quantification

Prospective validation further confirmed the clinical reliability of PAN-VIQ in a real-world setting, as illustrated in Fig. 5 and Table 2. Figure S4 shows the schematic illustration of tumor–vessel wrapping angle computation. This figure provides an example of how the model computes the wrapping angle based on the relative centroid position of the tumor and vessel. Confusion matrices for vascular invasion classifications by junior and senior radiologists were shown in Fig. S7. Among 202 consecutively enrolled patients, the model demonstrated high per-vessel accuracies for CA (87.78%), CHA (90.22%), SMA (87.43%), SMV (88.55%), and PV (87.36%). Notably, PAN-VIQ consistently outperformed junior radiologists across all five vessels (adjusted P < 0.01, Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons), with the largest performance gains observed in CHA (model: 90.22% vs. junior: 56.86%) and SMV (88.55% vs. 63.44%, respectively).

A Confusion matrices showing the detailed classification results of the PAN-VIQ model for five major vessels: CA, CHA, SMA, SMV, and PV. The heatmap colors represent the number of samples, ranging from red (higher sample counts) to blue (lower sample counts).Performance comparison among the PAN-VIQ model, senior radiologists, and junior radiologists across different evaluation metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and specificity. B The radar charts illustrate the overall performance distribution. C Bar graphs provide a detailed metric-by-metric comparison. The results indicate that the PAN-VIQ model outperforms junior radiologists in all metrics and achieves performance comparable to senior radiologists in certain aspects. Abbreviations: CA celiac artery, CHA common hepatic artery, SMA superior mesenteric artery, SMV superior mesenteric vein, PV portal vein.

Compared with senior radiologists, PAN-VIQ achieved non-inferior performance for both arterial (CA, SMA) and venous (SMV, PV) assessments. Non-inferiority was defined a priori as a maximum allowable difference of Δ < 5% in accuracy, with statistical comparisons showing P > 0.05 across all relevant vessel evaluations. This indicates that the model’s diagnostic accuracy did not fall outside the prespecified non-inferiority margin when benchmarked against expert performance, thus supporting its potential use in routine preoperative workflows. Model specificity remained exceptionally high across all vessels (e.g., CA: 96.54% [94.89–98.19]; CHA: 93.55% [91.32–95.78]), and false-positive rates were significantly lower than those of junior radiologists (P < 0.001), underscoring the model’s strength in minimizing overdiagnosis. Comprehensive comparative metrics between PAN-VIQ and radiologists with varying levels of experience are presented in Table 3.

Discussion

Preoperative vascular invasion assessment in PDAC is often limited by radiologist subjectivity and inter-institutional variability, leading to discrepancies between imaging interpretations and intraoperative findings. To address these challenges, we developed and validated PAN-VIQ, a deep learning framework that automatically quantifies three-dimensional anatomical relationships between pancreatic tumors and five major peripancreatic vessels (CA, CHA, SMA, SMV, PV) using dual-phase contrast-enhanced CT. By computing continuous tumor–vessel interaction metrics, PAN-VIQ enables precise anatomical quantification while producing outputs that align with clinical decision-making processes. To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically validate a continuous angle–based assessment framework through both retrospective multicenter and prospective clinical evaluations. As an auxiliary diagnostic tool, PAN-VIQ is designed to support both the radiology department and pancreatic surgery teams. It functions as a “second reader,” offering valuable assistance to junior radiologists, as well as to pancreatic surgeons with limited experience in image interpretation. Moreover, in hospitals with limited medical resources, PAN-VIQ can serve as a primary screening tool, helping to identify high-risk cases that require further clinical attention. The model demonstrated strong performance and generalizability across institutions and imaging protocols, offering a standardized and reproducible approach to support preoperative planning.

While conventional radiologic workflows rely on visual estimation of tumor–vessel contact from selected axial slices, PAN-VIQ automatically localizes regions of maximal tumor–vessel interaction through geometric analysis. This reduces dependence on operator input, minimizes interobserver variability, and provides spatially consistent measurements that more accurately reflect anatomical relationships, thereby enhancing the objectivity and reproducibility of preoperative evaluation. Rather than relying on fixed categorical classifications, continuous angle measurements capture the full spectrum of tumor–vessel interaction and delineate subtle anatomical transitions that may influence surgical feasibility, vascular reconstruction strategies, or neoadjuvant treatment planning. PAN-VIQ transforms these high-resolution metrics into structured outputs that align with established clinical workflows, supporting more individualized and consistent decision-making. This combined focus on geometric accuracy and clinical relevance highlights PAN-VIQ as a practical solution for enhancing preoperative assessment beyond conventional visual interpretation.

Beyond quantitative accuracy, practical implementation within clinical workflows is essential for translating PAN-VIQ into real-world use. In practice, the system can be integrated into the radiology workflow as a silent second reader, automatically analyzing contrast-enhanced CT scans and providing quantitative, vessel-specific encasement metrics. These structured outputs can be appended to radiologic reports or incorporated into multidisciplinary tumor board discussions, assisting radiologists and surgeons in evaluating surgical feasibility and planning vascular reconstruction when necessary. In non-expert or resource-limited centers, PAN-VIQ may also function as a primary screening tool to flag high-risk cases requiring further expert review, thereby promoting consistent and data-driven preoperative assessment across institutions.

To ensure accurate reference standards for model validation, this study included only patients who underwent surgery, allowing vascular involvement to be directly confirmed through intraoperative findings or pathological assessment. Future work is warranted to evaluate performance in non-surgical or biopsy-only cohorts, where objective confirmation may be limited. In this cohort, tumor-vessel contact was distributed as 79.7% with no contact, 14.7% with contact involving ≤180° of the vessel circumference, and 5.6% with contact exceeding 180° or associated with vascular occlusion, closely matching proportions reported in prior multi-center studies26,28, supporting the representativeness of our dataset. Model-based predictions aligned well with intraoperative findings, particularly for CA and SMA, where positive predictive values for contact >180° exceeded 85% and 76%, respectively. The difference in the positive rate of tumor involvement with SMA between the training cohort and the external validation cohort may be influenced by several factors. First, the external validation cohort had a smaller sample size compared to the training cohort, which may limit statistical power and contribute to increased variability in the results. Second, the inclusion of data from hospitals across different regions and varying levels of healthcare institutions in the external cohort strengthens the generalizability of the findings, reflecting the true diversity and complexity of clinical practice. This broad representation enhances the authenticity of the data, ensuring that the model’s performance is applicable to a wide range of real-world settings. Most prediction discrepancies occurred in cases with tumor contact involving vessel circumferences close to 180°, where radiologic interpretation is frequently challenged by anatomical ambiguity, peritumoral inflammation, or fibrotic distortion. Importantly, PAN-VIQ demonstrated greater consistency than radiologists in this intermediate range, particularly at the transition between contact ≤180° and >180°, underscoring its robustness in anatomically equivocal situations. In subgroup analyses, PAN-VIQ exhibited comparable accuracy for the SMA and CHA in patients with and without vascular anatomical variations, with no statistically significant differences in segmentation performance or tumor–vessel interface evaluation. This consistency supports the robustness and clinical applicability of the model in anatomically variant cases encountered during surgical planning.

In prospective validation, PAN-VIQ consistently outperformed junior radiologists and matched or exceeded senior radiologists in accuracy, precision, and recall across all five vessels. Notably, this performance improvement underscores the model’s utility in clinical settings where radiologists may have less experience, particularly in non-expert centers. By automating tumor–vessel interaction quantification and reducing reliance on subjective interpretation, PAN-VIQ standardizes vascular invasion assessments, minimizes interobserver variability, and provides a reliable, consistent decision-making tool in environments with limited radiological expertise. By providing anatomically grounded, vessel-specific angle continuity outputs, PAN-VIQ holds promise not only as a preoperative diagnosis model but also as a collaborative tool in multidisciplinary workflows, helping establish a common quantitative language for surgical planning in PDAC.

The reliability of PAN-VIQ is supported by a two-stage development framework that integrates accurate segmentation with robust spatial quantification. The segmentation module was developed using a three-phase progressive training pipeline combining supervised and semi-supervised learning. As illustrated in Fig. 2, this iterative strategy produced notable improvements in mask continuity and anatomical coherence across vessels and tumor margins. Early-stage segmentation inaccuracies, including discontinuous vascular contours, incorrect inclusion of adjacent structures, and incomplete tumor delineation, were progressively corrected through expert-guided refinement, providing a robust foundation for downstream angle quantification. While the segmentation of the five major vessels (CA, CHA, SMA, SMV, PV) demonstrated high accuracy, tumor segmentation presented unique challenges, particularly in the external validation cohort, where a DSC of 0.789 was observed. These differences can be attributed to several factors, including variations in imaging quality, differences in scanning protocols, and the inherent challenges in delineating tumor boundaries, particularly when tumors are small or located near complex anatomical structures. Such factors may contribute to variability in segmentation accuracy, highlighting the complexity of accurately delineating tumors in diverse clinical settings. In the first stage, the model was trained through a multi-phase learning pipeline incorporating fully supervised and semi-supervised strategies, followed by volume-based post-processing to reduce false positives and enhance anatomical plausibility across imaging modalities. The second stage incorporated an angle quantification module and occlusion detection algorithm, enabling the system to differentiate tumor-induced vessel interruptions from segmentation artifacts. This design improves spatial accuracy and interpretability, particularly in anatomically ambiguous or borderline scenarios, and contributes to the system’s generalizability across institutions.

This study had limitations. First, although multi-institutional CT datasets from hospitals of varying levels and scanning protocols were included to enhance generalizability, the model’s performance may still differ from real-world clinical settings. Its robustness across heterogeneous scanners and acquisition parameters warrants further validation. Second, while PAN-VIQ achieved accuracy comparable to experienced radiologists, its greater value may lie in providing standardized and reproducible assessments that reduce inter-observer variability. Future work will aim to refine workflow integration and improve interpretability to facilitate practical clinical adoption.

PAN-VIQ offers a reproducible and standardized framework for anatomical evaluation of vascular involvement in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. By automating tumor and vessel segmentation and quantifying three-dimensional tumor–vessel relationships, it generates continuous, interpretable metrics that may support consistent preoperative evaluation. This quantitative approach, grounded in anatomically precise measurement rather than fixed categorical staging, provides a scalable foundation for enhancing anatomical resolution. While this study focuses on standardized 3D quantification of tumor–vessel relationships, future efforts will seek to expand its clinical utility by enabling vessel-specific risk stratification and integrating multimodal data within routine imaging workflows to support personalized decision-making in PDAC.

Methods

Study design and patient data

Based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, we collected a total of 2130 patients with pathologically confirmed PDAC across four medical centers between 2018 and 2024. Retrospective data from Ruijin Hospital comprised 1759 cases, while external validation datasets were acquired from three additional centers: Center 1 (30 cases), Center 2 (85 cases), and Center 3 (54 cases). Additionally, a prospective dataset of 202 patients enrolled at our institution from January to December 2024 was used for further validation. Detailed patient demographics are presented in Table 1.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) patients undergoing exploratory laparotomy for PDAC with available intraoperative evaluation of vascular invasion; (2) pathologically confirmed PDAC; (3) availability of preoperative CT scans; (4) patients with or without neoadjuvant therapy (chemoradiotherapy or cytotoxic chemotherapy). Patients who did not undergo surgical exploration were excluded, as the absence of intraoperative or pathological reference standards precluded objective validation of vascular invasion. Exclusion criteria included: (1) contraindications to iodinated contrast (previous allergic reactions or serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL); (2) an interval exceeding 50 days between preoperative CT and surgery. All CT images were acquired from five scanners using a standardized protocol and stored in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format (Table S1).

PAN-VIQ framework design

The PAN-VIQ system integrates automated segmentation and 3D quantification to precisely evaluate vascular invasion in PDAC from CT images. Tumor regions of PDAC and five peripancreatic vessels (CA, CHA, SMA, SMV, PV) were segmented in the arterial and venous phases using a three-phase progressive training strategy, built upon the open-source nnU-Net architecture32. Separate models were trained for tumor segmentation in the arterial and venous phases, while vessel segmentation models were also phase-specific: the arterial phase focused on tumor, CA, SMA, and CHA, whereas the venous phase focused on tumor, SMV, and PV. The model was implemented using nnU-Net v2, built on PyTorch 1.13.1 and CUDA 11.6, and trained on NVIDIA A100 GPUs. This framework was chosen for its self-configuring nature, which allows automatic adaptation of architecture, preprocessing, and training parameters to the specific dataset, thereby enhancing reproducibility and facilitating deployment across institutions.

The segmentation module was trained via a three-phase progressive strategy involving supervised pretraining, semi-supervised refinement, and expert-guided tuning, as detailed in Fig. 1B. In Phase 1, a fully supervised training was conducted on 380 CT cases manually annotated by senior radiologists. In Phase 2, the preliminary model inferred masks on 500 additional cases, which were reviewed and corrected by radiologists to address boundary ambiguity and improve accuracy. In Phase 3, the dataset was expanded to 1200 cases, and the model was retrained after expert correction of newly generated masks to improve generalization. Separate models were trained for arterial and portal venous phases to accommodate vessel-specific enhancement characteristics. The models used a batch size of 2, a poly learning rate decay starting at 1e−3, and a combined Dice + cross-entropy loss. 5-fold cross-validation with stratified sampling by vascular involvement type was conducted to ensure robustness. Detailed implementation procedures, including software environment, training pipeline, data stratification, and evaluation metrics, are available in the Supplementary information. A schematic diagram of the three-phase segmentation workflow is shown in Supplementary information to facilitate reproducibility.

To minimize segmentation errors such as false positives or over-segmentation, we implemented a customized post-processing pipeline that applied empirically determined volume-based thresholds. Specifically, isolated masks with voxel counts below 415 for arterial phase, and 450 for venous phase were excluded, as they typically represented noise or false positives without anatomical correspondence. This step enhanced the specificity of vascular segmentation while preserving relevant structures. Details of threshold selection and validation are provided in the Supplementary information. Segmentation quality was objectively assessed via Dice coefficient (DSC), sensitivity, and specificity on internal and external datasets. Two radiologists independently evaluated segmentation reliability using a 5-point Likert scale, with inter-rater reliability assessed by ICC (stratified sampling detailed in Supplementary information).

Following segmentation, a vessel centerline extraction algorithm and spatial intersection computation were used to quantify 3D tumor–vessel wrapping angles, as depicted in Fig. 1C. As illustrated in Fig. S3, an occlusion detection step identified tumor-induced vascular occlusions by spatially aligning segmented occlusion regions with tumor locations. Areas overlapping with tumors were confirmed as true occlusions; otherwise, flagged for review, effectively reducing false positives. Further algorithmic details are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Vascular wrapping angles were derived by quantifying the maximum intersection between the segmented tumor and vessel centerlines in three-dimensional space, as detailed in the Supplementary Information. Complete encirclement was defined as 360°, while partial contact was measured continuously. Full encirclement was recorded as 360°, while partial intersections were measured at vessel-tumor intersection points, identifying the maximum wrapping angle. These quantitative metrics provided accurate assessments of vascular invasion severity (Fig. 2). For analysis purposes, continuous encasement angles were grouped into three categories: 0° (no contact), ≤180°, and >180° or occlusion. This stratification was used for comparison with radiologist interpretation and for downstream survival analysis, while the model output remained continuous.

Preoperative standard assessment

For comparative analysis, PAN-VIQ’s continuous circumferential contact angle outputs were grouped into three categories: Class 0 (no contact), Class 1 (≤180°), and Class 2 (>180° or occlusion). These categorical boundaries were applied consistently across model outputs and expert assessments. These categorical boundaries were also used in radiologic and intraoperative evaluations to ensure consistent interpretation and facilitate model performance comparison. Pre-treatment vascular involvement was prospectively assessed by a multidisciplinary team comprising abdominal radiologists (one senior radiologist with 20 years and two junior radiologists with 6 and 7 years of experience), surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, and gastroenterologists. The panel reviewed multiplanar CT reconstructions along with clinical data to establish vessel-specific tumor contact status for the CA, CHA, SMA, PV, and SMV. This consensus served as an expert reference for radiologic interpretation and preoperative preparation.

All patients underwent surgical exploration (with or without curative resection) performed by experienced pancreatic surgeons. Intraoperative observations of tumor–vessel relationships were used as the reference standard for vascular involvement. In resected cases, surgical margins were marked and assessed according to NCCN criteria13 to confirm the absence or presence of vascular invasion.

Validation

Model validation was conducted in two stages: retrospective validation and prospective validation. In the retrospective validation stage (January 2018 to December 2023), we evaluated PAN-VIQ’s performance against intraoperative vascular assessments using: an internal dataset comprising contrast-enhanced CT scans from our hospital and three external datasets totaling 169 patients from geographically distributed hospitals, as shown in Fig. 1D.

In all centers, both preoperative radiology reports and intraoperative surgical records documented tumor–vessel relationships, including the extent of involvement for the CA, CHA, SMA, PV, and SMV. Intraoperative findings were used as the reference standard for vascular invasion, whereas radiologist interpretations provided the clinical benchmark for assessing PAN-VIQ’s performance. To ensure direct comparability, radiologists classified vascular involvement using the same angle-based thresholds applied to model predictions: Class 0 (no contact), Class 1 (encasement ≤180°), and Class 2 (encasement >180° or occlusion), in accordance with NCCN resectability criteria. For patients who received neoadjuvant therapy, intraoperative findings may not accurately reflect the baseline extent of vascular involvement due to therapy-induced alterations in perivascular anatomy and tissue characteristics. Therefore, the reference standard in these cases was defined by multidisciplinary team (MDT) consensus based on pre-treatment contrast-enhanced CT imaging, reviewed prior to therapy initiation. PAN-VIQ-predicted vascular encasement angles (CA, SMA, CHA, SMV, PV) were compared to intraoperative findings. Performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and specificity, were computed individually for each vessel.

In the prospective validation stage (January–December 2024), we assessed PAN-VIQ’s generalizability in 202 consecutive patients. Model predictions were compared with blinded assessments by senior and junior radiologists, using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and specificity as performance metrics. For resectability classification, McNemar’s test was applied to evaluate discrepancies between PAN-VIQ and intraoperative reference standards based on matched evaluations from the same patients. Vessel-specific involvement was analyzed using chi-square tests, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

Segmentation performance was rigorously evaluated using Dice similarity coefficient (DSC), specificity, and sensitivity. Additionally, two radiologists independently rated segmentation quality on 400 randomly selected cases using a five-point Likert scale. Statistical analyses, including calculation of diagnostic metrics, 95% confidence intervals, and significance testing, were performed using SPSS (version 23.0) and Python (version 3.11.6). Visualizations were generated using R (version 4.3.1) and Seaborn (version 0.11.2).

Computational environment and reproducibility. Experiments were conducted on Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS (Jammy; kernel 6.8.0-59-generic) with 128 GB RAM, an Intel Core i7-14700K CPU, and a single NVIDIA A100-PCIE-40GB GPU (driver 550.144.03; CUDA runtime 12.4). The segmentation pipeline was implemented using the open-source nnU-Net (v1.7) on PyTorch 1.13.1 (CUDA 11.6 build).

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Ethics committee

This study fundamentally adhered to the STARD30 and TRIPOD31 guidelines, involving retrospective data collection from four hospitals. Ruijin Hospital served as the primary cohort (training/validation sets), while Hospitals 1–3 formed independent test sets 1–3. The study was approved by Hospital 1 Ethics Committee (KY-2025-294). For real-world prospective validation, January-December 2024, MR-31-25-044065. Independent IRB approvals for each participating institution were also obtained: external validation hospital 1: Ethics Committee of Tangshan People’s Hospital (Approval No. rmyyllks-2025310); external validation hospital 2: Ethics Committee of Wuxi No.2 People’s Hospital (Approval No. 2021-Y-42); external validation hospital 3: Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (Approval No. 2021–394). For the retrospective component, patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the data. For the prospective component, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All data supporting the findings of this study are included within the manuscript and its supplementary information files. All source code and pre-trained models used in this study are publicly available at: https://github.com/IMIT-PMCL/PDAC, ensuring full reproducibility of our results.

References

Siegel, R. L., Kratzer, T. B., Giaquinto, A. N., Sung, H. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 75, 10–45 (2025).

Rahib, L., Wehner, M. R., Matrisian, L. M. & Nead, K. T. Estimated projection of US cancer incidence and death to 2040. JAMA Netw. Open. 4, e214708 (2021).

Oettle, H. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA 310, 1473–1481 (2013).

Neoptolemos, J. P. et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 389, 1011–1024 (2017).

Conroy, T. et al. FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 2395–2406 (2018).

Rigiroli, F. et al. CT radiomic features of superior mesenteric artery involvement in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a pilot study. Radiology 301, 610–622 (2021).

Giovinazzo, F., Turri, G., Katz, M. H., Heaton, N. & Ahmed, I. Meta-analysis of benefits of portal–superior mesenteric vein resection in pancreatic resection for ductal adenocarcinoma. Br. J. Surg. 103, 179–191 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Venous resection during pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer: a systematic review. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 4, 46 (2019).

Delpero, J. R. & Sauvanet, A. Vascular resection for pancreatic cancer: 2019 French recommendations based on a literature review from 2008 to 6–2019. Front. Oncol. 10, 40 (2020).

Al-Hawary, M. M. et al. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma radiology reporting template: consensus statement of the Society of Abdominal Radiology and the American Pancreatic Association. Radiology 270, 248–260 (2014).

Zamboni, G. A. et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: value of multidetector CT angiography in preoperative evaluation. Radiology 245, 770–778 (2007).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma (Version 2.2024) (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2024).

Miao, Y., Cai, B. & Lu, Z. Technical options in surgery for artery-involving pancreatic cancer: invasion depth matters. Surg. Open Sci. 12, 55–61 (2023).

Bockhorn, M. et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: a consensus statement by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 155, 977–988 (2014).

Brook, O. R. et al. Structured reporting of multiphasic CT for pancreatic cancer: potential effect on staging and surgical planning. Radiology. 274, 464–472 (2015).

Alemi, F., Rocha, F. G., Helton, W. S., Biehl, T. & Alseidi, A. Classification and techniques of en bloc venous reconstruction for pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB 18, 827–834 (2016).

Hong, S. B. et al. Pancreatic cancer CT: prediction of resectability according to NCCN criteria. Radiology 289, 710–719 (2018).

Ferrone, C. R. et al. Radiological and surgical implications of neoadjuvant treatment with FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann. Surg. 261, 12–17 (2015).

Michelakos, T. et al. Predictors of resectability and survival in patients with borderline and locally advanced pancreatic cancer who underwent neoadjuvant treatment with FOLFIRINOX. Ann. Surg. 269, 733–740 (2019).

Asbun, H. J. et al. The miami international evidence-based guidelines on minimally invasive pancreas resection. Ann. Surg. 271, 1–14 (2020).

Cao, K. et al. Large-scale pancreatic cancer detection via non-contrast CT and deep learning. Nat. Med. 29, 3033–3043 (2023).

Placido, D. et al. A deep learning algorithm to predict risk of pancreatic cancer from disease trajectories. Nat. Med. 29, 1113–1122 (2023).

Fu, N. et al. A deep-learning radiomics-based lymph node metastasis predictive model for pancreatic cancer: a diagnostic study. Int. J. Surg. 109, 2196–2203 (2023).

Antony, A. et al. AI-driven insights in pancreatic cancer imaging: from pre-diagnostic detection to prognostication. Abdom. Radiol. 50, 3214–3224 (2025).

Murray, K. et al. Biomarkers, omics and artificial intelligence for early detection of pancreatic cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 111, 76–88 (2025).

Bereska, J. I. et al. Artificial intelligence for assessment of vascular involvement and tumor resectability on CT in patients with pancreatic cancer. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 8, 18 (2024).

Vivier, C. et al. Segmentation-based assessment of tumor–vessel involvement for surgical resectability prediction of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. In Proc. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW) 2413–2423 (IEEE, 2023).

Bian, Y. et al. Performance of CT-based radiomics in diagnosis of superior mesenteric vein resection margin in patients with pancreatic head cancer. Abdom. Radiol. 45, 759–773 (2020).

Chen, F. et al. Radiomics-assisted presurgical prediction for surgical portal vein–superior mesenteric vein invasion in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 10, 523543 (2020).

Cohen, J. F. et al. STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open. 6, e012799 (2016).

Collins, G. S., Reitsma, J. B., Altman, D. G. & Moons, K. G. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ 350, g7594 (2015).

Isensee, F. et al. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods. 18, 203–211 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82472065, W2432049), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC2409501), the National Center for Translational Medicine (Shanghai) (NRCTM(SH)-2025-11), the Shanghai Explorer Program (24TS1414900), and the Shanghai Pujiang Program (2023PJD055). The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z., H.Z., and Y.Y. contributed equally to this work and share co–first authorship. F.Y., B.S., and N.W. contributed equally as senior and corresponding authors. Y.Z. designed the study framework, performed data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. H.Z. led the implementation of model development, image preprocessing, and validation analysis. Y.Y. was responsible for radiologic data curation, manual annotation coordination, and statistical evaluation. C.W. contributed to external data collection and validation from the Chongqing cohort. L.Z. and X.Zh. performed imaging quality assessment and segmentation audits for the Wuxi dataset. W.X. supported data harmonization and internal consistency checks. X.W. assisted in multi-site annotation standardization and reviewed segmentation quality. L.C. contributed to the external validation data preparation from Tangshan and coordinated site-level ethics. M.L. provided technical support for model training infrastructure and statistical validation. J.Z. reviewed histopathological findings and supported clinical endpoint verification. F.Y. supervised imaging methodology development and critically revised the manuscript. B.S. provided clinical surgical insights, confirmed intraoperative reference standards, and contributed to study design refinement. N.W. conceived and coordinated the overall project, supervised all analytical processes, and finalized the manuscript for submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Zhang, H., Yang, Y. et al. A clinically validated 3D deep learning approach for quantifying vascular invasion in pancreatic cancer. npj Digit. Med. 9, 79 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02260-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02260-3