Abstract

Healthy diets are known for their co-benefits of reducing environmental impacts and enabling the same agricultural resources to feed a larger human population. The EAT-Lancet (healthy reference) diet allows for compound benefits to human health and the ecosystem. It is unclear, however, to what extent the requirements of the EAT-Lancet diet may be sustainably met at the global scale. Here we combine a spatially distributed agro-hydrological model with a linear optimization analysis to relocate crops, minimizing, at the country scale, the irrigation-water consumption while improving the worldwide achievement of the EAT-Lancet nutritional goals. To that end, we define six dietary scenarios based on country-specific dietary habits from religion-related traditions, and existing livestock production systems, maintaining the same agricultural trade patterns (import–export relations). Our results suggest that an optimized global cropland allocation, and an adjustment in trade flows, would allow the global population to be fed with the EAT-Lancet diet, with a global reduction of the cultivated area of 37–40%, irrigation-water consumption of 78% (±3%), and unsustainably irrigated areas of 22%. The adoption of the EAT-Lancet diet increases the global food trade share of global food production, measured in kilocalories, from 25% (baseline) to 36% (±2%).

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data supporting the study have been sourced from freely and publicly available sources, which are cited within the main text or Supplementary Information.

Code availability

The code for the optimization process is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13886864 (ref. 70).

References

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP & WHO The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021 (FAO, 2021); https://doi.org/10.4060/cb4474en

Tilman, D. & Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 515, 518–522 (2014).

Willett, W. et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 393, 447–492 (2019).

Godfray, H. C. J. et al. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327, 812–818 (2010).

Hendriks, S. L. et al. Global environmental climate change, COVID-19, and conflict threaten food security and nutrition. Brit. Med. J. 378, e071534 (2022).

Afshin, A. et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 393, 1958–1972 (2019).

Food Systems and Diets: Facing the Challenges of the 21st Century (Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition, 2016).

D’Odorico, P. et al. The global food–energy–water nexus. Rev. Geophys. 56, 456–531 (2018).

Davis, K. F., D’Odorico, P. & Rulli, M. C. Moderating diets to feed the future. Earths Future 2, 559–565 (2014).

Davis, K. F., Seveso, A., Rulli, M. C. & D'Odorico, P. Water savings of crop redistribution in the United States. Water 9, 83 (2017).

Rosa, L. et al. Potential for sustainable irrigation expansion in a 3 °C warmer climate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 29526–29534 (2020).

Rodell, M. et al. Emerging trends in global freshwater availability. Nature 557, 651–659 (2018).

Mueller, N. D. et al. Closing yield gaps through nutrient and water management. Nature 490, 254–257 (2012).

Rosa, L. et al. Closing the yield gap while ensuring water sustainability. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 104002 (2018).

Kummu, M. et al. Lost food, wasted resources: global food supply chain losses and their impacts on freshwater, cropland, and fertiliser use. Sci. Total Environ. 438, 477–489 (2012).

Gephart, J. A. et al. The environmental cost of subsistence: optimizing diets to minimize footprints. Sci. Total Environ. 553, 120–127 (2016).

Jalava, M., Kummu, M., Porkka, M., Siebert, S. & Varis, O. Diet change—a solution to reduce water use? Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 074016 (2014).

Tuninetti, M., Ridolfi, L. & Laio, F. Compliance with EAT–Lancet dietary guidelines would reduce global water footprint but increase it for 40% of the world population. Nat. Food 3, 143–151 (2022).

Vanham, D., Hoekstra, A. Y. & Bidoglio, G. Potential water saving through changes in European diets. Environ. Int. 61, 45–56 (2013).

Beyer, R. M., Hua, F., Martin, P. A., Manica, A. & Rademacher, T. Relocating croplands could drastically reduce the environmental impacts of global food production. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 49 (2022).

Davis, K. F. et al. Alternative cereals can improve water use and nutrient supply in India. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao1108 (2018).

Davis, K. F., Rulli, M. C., Seveso, A. & D’Odorico, P. Increased food production and reduced water use through optimized crop distribution. Nat. Geosci. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-017-0004-5 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Integrating crop redistribution and improved management towards meeting China’s food demand with lower environmental costs. Nat. Food 3, 1031–1039 (2022).

Richter, B. D. et al. Alleviating water scarcity by optimizing crop mixes. Nat. Water 1, 1035–1047 (2023).

Folberth, C. et al. The global cropland-sparing potential of high-yield farming. Nat. Sustain. 3, 281–289 (2020).

Damerau, K. et al. India has natural resource capacity to achieve nutrition security, reduce health risks and improve environmental sustainability. Nat. Food 1, 631–639 (2020).

Xie, W. et al. Crop switching can enhance environmental sustainability and farmer incomes in China. Nature 616, 300–305 (2023).

Chakraborti, R. et al. Crop switching for water sustainability in India’s food bowl yields co-benefits for food security and farmers’ profits. Nat. Water 1, 864–878 (2023).

Karavasiloglou, N. et al. Adherence to the EAT-Lancet reference diet is associated with a reduced risk of incident cancer and all-cause mortality in UK adults. One Earth 6, 1726–1734 (2023).

Ricciardi, L., D’Odorico, P., Chiarelli, D. D. & Rulli, M. C. To what extent can agriculture be reshaped to address healthy and sustainable diets by boosting pulse production locally? Glob. Food Sec. 40, 100734 (2024).

Hirvonen, K., Bai, Y., Headey, D. & Masters, W. A. Affordability of the EAT–Lancet reference diet: a global analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 8, e59–e66 (2020).

Kastner, T., Kastner, M. & Nonhebel, S. Tracing distant environmental impacts of agricultural products from a consumer perspective. Ecol. Econ. 70, 1032–1040 (2011).

Chiarelli, D. D. et al. The green and blue crop water requirement WATNEEDS model and its global gridded outputs. Sci. Data 7, 273 (2020).

Gaez Data Portal v.4 (FAO, 2021); https://gaez.fao.org/pages/data-viewer-theme-2

Moreira, L. C., Rosa, G. J. M. & Schaefer, D. M. Beef production from cull dairy cows: a review from culling to consumption. J. Anim. Sci. 99, skab192 (2021).

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 (GBD 2015) Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) 1980–2015 (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2016).

Siebert, S. & Döll, P. Quantifying blue and green virtual water contents in global crop production as well as potential production losses without irrigation. J. Hydrol. 384, 198–217 (2010).

Hoekstra, A. Y. & Mekonnen, M. M. The water footprint of humanity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 3232–3237 (2012).

Springmann, M. et al. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature 562, 519–525 (2018).

Springmann, M. in Environmental Nutrition (ed. Sabaté, J.) 197–227 (Academic Press, 2019).

The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets—Agricultural Trade, Climate Change and Food Security (FAO, 2018).

Sardo, M., Epifani, I., D’Odorico, P., Galli, N. & Rulli, M. C. Exploring the water–food nexus reveals the interlinkages with urban human conflicts in Central America. Nat. Water 1, 348–358 (2023).

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP & WHO The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022 (FAO, 2022).

Vanham, D. Water resources for sustainable healthy diets: state of the art and outlook. Water 12, 3224 (2020).

Crenna, E., Sinkko, T. & Sala, S. Biodiversity impacts due to food consumption in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 227, 378–391 (2019).

Pais, D. F., Marques, A. C. & Fuinhas, J. A. Drivers of a new dietary transition towards a sustainable and healthy future. Clean. Responsib. Consum. 3, 100025 (2021).

Clark, M. et al. The role of healthy diets in environmentally sustainable food systems. Food Nutr. Bull. 41, 31S–58S (2020).

Aguilar, J. et al. Crop species diversity changes in the United States: 1978–2012. PLoS ONE 10, e0136580 (2015).

Feliciano, D. A review on the contribution of crop diversification to Sustainable Development Goal 1 “No poverty” in different world regions. Sustain. Dev. 27, 795–808 (2019).

Volsi, B., Higashi, G. E., Bordin, I. & Telles, T. S. The diversification of species in crop rotation increases the profitability of grain production systems. Sci. Rep. 12, 19849 (2022).

Bianchi, F. J. J. A., Booij, C. J. H. & Tscharntke, T. Sustainable pest regulation in agricultural landscapes: a review on landscape composition, biodiversity and natural pest control. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 1715–1727 (2006).

Adjimoti, G. O., Kwadzo, G. T., Sarpong, D. B. & Onumah, E. E. Input policies and crop diversification: evidence from the Collines Region in Benin. Afr. Dev. Rev. 29, 512–523 (2017).

Barman, A., Saha, P., Patel, S. & Bera, A. in Sustainable Crop Production—Recent Advances (eds Singh Meena, V. et al.) Ch. 5 (IntechOpen, 2022); https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.102635

Karanja, A., Ickowitz, A., Stadlmayr, B. & McMullin, S. Understanding drivers of food choice in low- and middle-income countries: s systematic mapping study. Glob. Food Sec. 32, 100615 (2022).

Darmon, N. & Drewnowski, A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutr. Rev. 73, 643–660 (2015).

Springmann, M., Clark, M. A., Rayner, M., Scarborough, P. & Webb, P. The global and regional costs of healthy and sustainable dietary patterns: a modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health 5, e797–e807 (2021).

The EAT–Lancet 2.0 Commissioners and contributing authors. EAT–Lancet Commission 2.0: securing a just transition to healthy, environmentally sustainable diets for all. Lancet 402, 352–354 (2023).

Herforth, A., Holleman, C., Bai, Y. & Masters, W. A. The Cost and Affordability of a Healthy Diet (CoAHD) Indicators: Methods and Data Sources (FAO, 2023); https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/CAHD

Gatto, A., Kuiper, M. & van Meijl, H. Economic, social and environmental spillovers decrease the benefits of a global dietary shift. Nat. Food 4, 496–507 (2023).

Drewnowski, A. et al. Toward healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 4, nzaa083 (2020).

FAOSTAT: New Food Balances (FAO, 2023).

IFPRI: Global spatially-disaggregated crop production statistics data for 2010 Version 1.1. Harvard Dataverse V3 https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PRFF8V (2019).

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 – Financing to End Hunger, Food Insecurity and Malnutrition in All Its Forms (FAO, 2024).

Herforth, A. et al. Cost and Affordability of Healthy Diets Across and Within Countries. Background Paper for The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. FAO Agricultural Development Economics Technical Study No. 9 (FAO, 2020); https://doi.org/10.4060/cb2431en

Herforth, A. et al. Methods and Options to Monitor the Cost and Affordability of a Healthy Diet Globally: Background Paper for The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022 (FAO, 2022); https://doi.org/10.22004/AG.ECON.324075

Suite of Food Security Indicators (FAOSTAT, 2023).

Springmann, M. et al. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: a global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet. Health 2, e451 (2018).

The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010–2050 (Pew Research Center, 2015).

Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes and Prevention (FAO, 2011); https://www.fao.org/sustainable-food-value-chains/library/details/en/c/266053/

Sardo, M. et al. Core script related to: meeting the EAT-Lancet “healthy” diet target while protecting land and water resources. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13886864 (2024).

Acknowledgements

C.G., N.G.,D.D.C. and M.C.R. acknowledge support from EC-NextGeneration EU EP RETURN (CUP D43C22003030002). C.G., D.D.C., M.S. and M.C.R. acknowledge support from EC-H2020-PRIMA AG-WAMED (CUP D43C21000410001). N.G., L.R., D.D.C. and M.C.R. acknowledge support from EC-H2020-PRIMA NEXUS-NESS (CUP D49J21005050006). P.D. was funded by the USDA Hatch Multistate project no. W5190 capacity fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C.R. and P.D. have conceptualized and supervised the study. M.C.R., M.S., L.R., C.G., N.G., D.D.C., A.M.K. and P.D. contributed to the development of methodology, execution of formal analysis, writing, review and editing of the paper. A.M.K., N.G., C.G., L.R. and M.S. have contributed to the visuals.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Michalis Hadjikakou and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Soybean global trade flows in the Baseline (a) and in reallocation scenarios (b–g).

Figures S25–S31 show the ‘final trade’ of commodities for the crop macro-groups (tonnes), for the baseline and the EAT-Lancet diet scenarios, considering trade flows as reported by FAOSTAT’s trade matrix (FAO, 2020). The detailed final trade flows and imports and exports quantities for each country are reported respectively in Supplementary Tables 4–6, while final trade flows and imports and exports quantities, calculated using the method from Kastner et al.32, are reported respectively in Supplementary Tables 7–9.

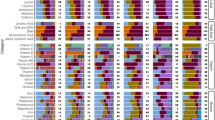

Extended Data Fig. 2 Resulting number of countries per each SP interval.

6 intervals of SP values have been considered (SP < 0.2; 0.2 ≤ SP < 0.5; 0.5 ≤ SP < 0.75; 0.75 ≤ SP < 0.85; 0.85 ≤ SP < 0.95; SP = 1)—and each diet scenario, compared with the current scenario In the small states or territories of Hong Kong, Lithuania and Macau and the islands of Comoros, Kiribati, Samoa and Maldives the algorithm allocated no harvested area (resulting in SP = 0), because of the low availability of cropland suitable for crop reallocation. SP is the degree of satisfaction of the EAT-Lancet diet requirement by relocated crop production, it has been assessed per country, scenario and crop by dividing the relocated domestic crop production by the crop production required by the EAT-Lancet diet (SI, Section S2).

Extended Data Fig. 3

Percentage of population satisfied by the EAT- Lancet diet in each country, by the new domestic food supply, in the diet scenario D40. Grey circle line indicates 100% of population satisfaction.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Food group’s share of diet cost in each dietary scenario by geographic region.

Food group’s share is calculated as the summation over all countries in a geographic region for a specific food group’s cost per person per day divided by the summation over all countries in a geographic region for the total diet cost per person per day.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–43, Tables 1–6, Methods and references.

Supplementary Data 1

Correction factors for SPAM yields.

Supplementary Data 2

Crop production demand required by the EAT-Lancet dietary guidelines (tonnes).

Supplementary Data 3

Percentage trade flow variations from the baseline.

Supplementary Data 4

Total exports (tonnes) per crop macro-group and country that are actually satisfied by crop reallocation.

Supplementary Data 5

Country variation in blue water consumption compared to the total BW consumed in the baseline (%).

Supplementary Data 6

Hectares of irrigated harvested area interested by water scarcity (WS).

Supplementary Data 7

Country variation in rainfed harvested area compared to the total irrigated area in the baseline (%).

Supplementary Data 8

Country variation in irrigated harvested area per crop-group, compared to the irrigated area in the baseline.

Supplementary Data 9

Country variation in rainfed harvested area per crop-group, compared to the irrigated area in the baseline.

Supplementary Data 10

Satisfied population percentage.

Supplementary Data 11

Simpson Index per country and scenario.

Supplementary Data 12

Shannon Index and Effective Number of Crop Species per country and scenario.

Supplementary Data 13

Country-specific cost (in $ purchasing power parity from 2017 per person per day) of dietary scenarios.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Rulli, M.C., Sardo, M., Ricciardi, L. et al. Meeting the EAT-Lancet ‘healthy’ diet target while protecting land and water resources. Nat Sustain 7, 1651–1661 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01457-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01457-w