Abstract

Renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, fluctuate on timescales of seconds to hours. Harnessing such intermittent energy to drive chemical synthesis represents a major challenge, as conventional 3d-block metal catalysts are prone to degradation even under small variations in operating potential. Here we report an electrochemical oxygen evolution reaction system that is tolerant to voltage fluctuations through the design of catalytic pathways. By leveraging the redox chemistry of manganese oxide, we integrated the Guyard reaction (4Mn2+ + Mn7+ → 5Mn3+) as a regeneration pathway into the catalytic cycle. Unlike other 3d-block metal catalysts, which rapidly degrade under fluctuating conditions, the constructed manganese oxide system shows resilience to voltage fluctuations by alternating between decomposition and regeneration. When the voltage is switched between 1.68 and 3.00 V repeatedly, the catalyst can maintain an oxygen evolution reaction at pH 2 for more than 2,000 h, highlighting the importance of pathway design for sustainable energy conversion from intermittent renewable sources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Electrolysis can convert renewable electricity into chemical fuels, such as hydrogen, ammonia and hydrocarbons, and is therefore expected to play a crucial role in promoting our sustainability1. However, because renewable energy sources such as wind, solar and geothermal energy fluctuate over time2,3, electrocatalytic devices powered by these sources must also be able to operate under intermittent conditions. While significant progress has been made to improve electrocatalytic materials in recent decades, most studies have focused on constant voltage or current conditions4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Consequently, the influence of environmental fluctuation on the activity and longevity of electrocatalysts has not been fully investigated, posing challenges for both material development17,18 and theoretical studies9,19. This issue is particularly important for electrocatalysts based on 3d-block metals, which are essential for large-scale deployment of electrolysis technology but suffer from rapid corrosion even with small variations in operation potential7,8,9,10,19,20. Strategies to enhance the resilience of electrocatalysts under fluctuating conditions are therefore crucial for realizing scalable electrosynthesis processes powered by renewable energy.

Among many electrochemical reactions, the electrochemical oxygen evolution reaction (OER) (2H2O → O2 + 4H+ + 4e−) poses a severe stability challenge, given that the OER catalysts are inherently exposed to high oxidation potentials. Previous studies of OER catalysts have shown that the high oxidation potential required for water oxidation leads to catalyst corrosion and marked losses in catalytic activity7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Such catalyst corrosion often produces metal ions in their highest oxidation states, including MnO4− (refs. 7,8,9,10,11,12), RuO4 (refs. 13,14,15) and IrO3 (refs. 15,16). While in situ electrodeposition of low-valence-state ions has been proved to be effective as a self-healing strategy of OER catalysts8,12, this approach cannot be used when the dissolved ions have higher oxidation states than the metal oxide.

Here we demonstrate a manganese-oxide-based OER system that is resilient to voltage fluctuations. The enhanced resilience arises from redox pathway design, in which the Guyard reaction (4Mn2+ + Mn7+ → 5Mn3+) is incorporated into the catalytic cycle to redeposit Mn7+ onto the catalyst. Unlike conventional 3d-block metal catalysts, which rapidly degrade irreversibly, the constructed system can regenerate itself after degradation via repeated oxidative pulses, allowing it to sustain a high current density of approximately 250 mA cm−2 under voltage fluctuation conditions in acidic media. These findings establish a self-healing principle for OER catalysis based on the redox pathway design, which is crucial for applications that require electrolysis at high current densities under fluctuating conditions.

Results

Catalytic cycle of the OER on MnO2

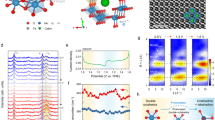

To construct an electrocatalytic water oxidation system that is resistant to voltage fluctuation, we focused on Mn oxide due to its rich redox chemistry and wide range of oxidation states ranging from 2+ to 7+ (refs. 7,8,9,10,11,12,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31). In addition to redox reactions that involve incremental changes in the oxidation state, manganese ions participate in charge comproportionation and disproportionation reactions32,33,34,35,36,37,38, which connect discrete redox states of Mn species (Fig. 1a). The redox states of Mn species involved during the OER on Mn oxides have been studied comprehensively using various spectroscopic techniques, including in situ electrochemical ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy7,8,9,10,11,22,23,24,25, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR)21,22,23 and in situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy6,23,26,27,28. These studies have shown that Mn oxide undergoes a sequential redox cycle of 2+, 3+ and 4+ (refs. 6,7,8,9,10,11,12,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28) at water oxidation potentials in an acidic electrolyte (Fig. 1b, OER on-cycle reactions). However, shifting the electrode potential even more positively activates an unfavourable reaction pathway. This pathway produces MnO4−, which is highly soluble and thus corrodes the electrode (Mn7+; Fig. 1c, OER off-cycle reaction). As Mn7+ is the highest oxidation state for Mn species, the dissolution of Mn7+ into the electrolyte leads to irreversible deactivation of the catalyst.

a, Representative redox reactions associated with manganese ions. b, Redox processes on MnO2 at potentials below 1.75 V vs. RHE in sulfuric acid7,8,9,10,11,12,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Under these conditions, Mn undergoes sequential oxidation from Mn2+ to Mn3+ and then Mn4+ during the OER cycle, but no Mn7+ is generated. c, Redox processes on MnO2 at potentials above 1.75 V vs. RHE. Mn7+ is generated, resulting in irreversible catalyst dissolution7,8,9,10. d, Target catalytic network of this study. Although MnO4− is formed during the OER, the charge comproportionation reaction between Mn7+ and Mn2+ forms Mn3+, which can be reincorporated into the OER cycle. CD, charge disproportionation; CC, charge comproportionation.

Addition of the Guyard reaction to the OER cycle

During the OER, the formation of MnO4− is initiated when the electrode potential exceeds a certain threshold at 1.8 V versus the reversible hydrogen electrode (vs. RHE) in acid. Therefore, when Mn oxides are subjected to voltage fluctuations (as is expected to be the case when solar and wind power are used to drive electrolysis), OER activity decreases with the dissolution of MnO2 in the electrolyte. To mitigate the susceptibility of Mn oxides to voltage fluctuations, we aimed to introduce a charge comproportionation reaction between Mn2+ and Mn7+ into the OER cycle. The comproportionation of Mn2+ and Mn7+ to form Mn3+ (Fig. 1d) is known as the Guyard reaction32,33,34,35,36,37,38 in homogeneous chemistry and is promoted by inorganic ions such as phosphate9,33,34,35 and oxalate35,36. When the Guyard reaction is incorporated into the OER cycle, the Mn7+ that dissolved from Mn oxide can react with the Mn2+ OER intermediate to generate Mn3+. This species can be electrochemically oxidized back to the bulk oxide, allowing the catalyst to be regenerated (Fig. 1d) and therefore making the Mn oxide system resistant to voltage fluctuations.

To investigate whether the Guyard reaction could be incorporated into the OER cycle, the charge comproportionation reaction between Mn2+ and Mn7+ was first conducted in acidic electrolyte (pH 2), and the species involved in the Guyard reaction were monitored using UV–Vis spectroscopy, continuous-wave EPR and X-ray absorption near edge structure spectroscopy (Fig. 2). When phosphate ions were added to the reaction mixture (pH 2) containing a 1:4 ratio of Mn7+ and Mn2+, the UV–Vis absorption band of Mn7+ disappeared (Fig. 2a), and a new band attributable to the d-d transition of Mn3+ was generated at 520 nm (refs. 24,37). This assignment was confirmed via continuous-wave EPR spectroscopy (Fig. 2b), in which six well-resolved hyperfine lines attributed to Mn3+ (d4, S = 2) were observed in parallel mode due to the charge comproportionation reaction between EPR-active Mn2+ (d5, S = 5/2) and EPR-silent Mn7+ (d0, S = 0). A linear relationship between the Mn oxidation state and X-ray absorption edge energy from standard samples further verified that the Guyard reaction product had an oxidation state of 3+ (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 1). The reaction was determined to be first-order with respect to Mn7+ and pseudo-first-order (~1.3) with respect to Mn2+ (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). These findings are consistent with previous studies, which suggested that the rate-determining step of the Guyard reaction is the reaction between Mn7+ and either monomeric or dimeric Mn2+ complexes bridged with phosphate. In contrast, no spectroscopic signatures of Mn3+ were detected when the reaction was conducted without phosphate ions (Supplementary Fig. 4), confirming that the Guyard reaction is accelerated in the presence of phosphate.

a–c, The charge comproportionation reaction between Mn7+ and Mn2+ in the presence of phosphate was investigated using UV–Vis spectroscopy (a), continuous-wave EPR (CW-EPR) (b) and Mn K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure spectroscopy (c). The reactions were performed at pH 2 with 1.0 M phosphate ions for 1 h at 25 °C, without applying electrochemical potentials. The formation of Mn3+ as the reaction product was subsequently confirmed via each spectroscopic technique.

OER under voltage fluctuation

Figures 3 and 4 show how the catalytic lifetime under voltage fluctuations is influenced by the Guyard reaction. In this experiment, MnO2 deposited on a fluorine doped tin oxide (FTO) substrate and a Pt wire were used as the working and counter electrodes, respectively, in a two-chamber electrochemical cell separated by a proton conductive membrane (Supplementary Fig. 5). A sulfuric acid solution (pH 2) was used as a base electrolyte (Fig. 3), and 1.0 M phosphate ions was added into the system to induce the Guyard reaction (Fig. 4). Programmed pulsed voltages were used to simulate voltage fluctuations, which may occur due to renewable energy being intermittent (Fig. 3a). When the voltage was alternated between 3.00 (8 min) and 1.68 V (180 min), the OER current from Mn oxide decreased by over 90% in less than 200 cycles from the initial current density of 280 mA cm−2 (Fig. 3b). This rapid degradation in catalytic activity was due to the dissolution of MnO2, as evidenced by the accumulation of Mn7+ in the electrolyte (Fig. 3c). The dissolution of Mn ions as the primary mechanism for the loss of OER activity was further confirmed using an electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance (QCM), which showed a significant decrease in the MnO2 electrode mass (−54.0 ± 1.5 ng s−1) at 3.00 V (Fig. 3d). The accumulation of Mn7+ after each voltage pulse results in the electrolyte showing an intense pink colour, as can be seen in the time-course images (Fig. 3e) and video (Supplementary Video 1).

a, To simulate voltage fluctuations, the cell voltage was alternated between 3.00 V (8 min) and 1.68 V (3 h). b–e, The stability of Mn oxide was evaluated by measuring current densities (b); the concentration of dissolved Mn7+ in the pH 2 sulfuric acid electrolyte (c), which was determined from the UV–Vis absorption intensity at 545 nm; mass changes (Δm) of the MnO2 electrode (d), which were quantified using a QCM; and colour changes of the electrolyte solution (e). For the QCM measurements, the 3.00 V pulse was applied for 20 s, and the baseline potential of 1.68 V was applied for 300 seconds. All measurements were performed in a two-electrode system equipped with platinum wire as the counter electrode.

a–e, The stability of Mn oxide under voltage fluctuation (the same conditions as those used in Fig. 3) was evaluated at pH 2 with 1.0 M phosphate ions on the basis of the concentration of Mn7+ dissolved in the electrolyte (a), the mass change of the MnO2 electrode (b), the colour change of the electrolyte (c) and the current density over time (d,e).

To incorporate the Guyard reaction into the catalytic cycle of the Mn oxide catalyst, 1.0 M phosphate ions at pH 2 was used as the electrolyte, and catalyst stability was evaluated using the same voltage protocol (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 6). In the presence of phosphate, the dissolution of the permanganate ion was no longer irreversible due to the charge comproportionation reaction being activated. Namely, the Mn7+ concentration decreased every time the voltage was returned to 1.68 V, as indicated by the disappearance of the characteristic MnO4− absorption bands within ~180 minutes (Fig. 4a). This is concurrent with the redeposition of Mn oxide, as shown in the mass increase of the MnO2 catalyst (Fig. 4b). Under the specific voltage protocol of this study, Mn oxide exhibited a mass loss rate of −36.6 ± 1.5 ng s−1 at 3.00 V and a mass gain rate of 1.0 ± 0.2 ng s−1 at 1.68 V. This indicates that the catalyst undergoes repeated dissolution and redeposition under these variable potential conditions. The recovery of the catalyst was also clearly visible from the colour of the electrolyte, which alternated between pink and colourless. The intensity of the pink colour increased immediately during each voltage pulse but gradually lessened over time when the voltage was returned to 1.68 V (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Video 2). These findings demonstrate that the charge comproportionation reaction indeed promoted the continuous recovery of the catalyst under fluctuating voltage conditions. The OER on MnO2 persisted for more than 600 cycles, corresponding to over 2,100 h of operation, with only a 10% loss in activity (Fig. 3d,e). The system operated at 1.68 V and 3.0 V for approximately 95.5% and 4.5% of the total run time, at current densities of ~5 mA cm−2 and ~250 mA cm−2, respectively. The stability number for one loop of the fluctuation (3.00 V for 8 min and 1.68 V for 180 min) is estimated to be 1.2 × 104, about 15 times higher than that without the presence of phosphate. The introduction of the charge comproportionation reaction markedly improved the stability of this electrocatalytic system, demonstrating the importance of controlling the catalytic cycle. The synchrotron radiation powder X-ray diffraction (Supplementary Fig. 7a) patterns of the catalyst after 50 h of electrolysis at pH 2 with 1.0 M phosphate ion confirmed that no new crystal phases were formed during electrolysis. Transmission electron microscopy (Supplementary Fig. 7b,c) also confirmed that there were no significant changes in the morphology of the catalyst. The minimal change in the oxidation state of Mn (less than +0.02) was observed via X-ray absorption spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, indicating that the redeposition process via the Guyard reaction can preserve the oxidation state of Mn species (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). The electrolyte pH remained stable at pH 2 ± 0.02 during electrolysis, eliminating pH fluctuation as a factor in catalyst stability (Supplementary Fig. 10).

The OER was also performed with Co3O4, Fe2O3 and NiO as catalysts, under the same conditions as those used for MnO2 (Fig. 5). In contrast to MnO2, none of these materials demonstrated sustained OER activity under voltage fluctuations even in the presence of phosphate. For example, cobalt oxide showed a higher initial OER current (330 mA cm−2) than MnO2 (280 mA cm−2), but the OER activity was completely diminished after only 20 voltage pulses. The lifetimes of iron and nickel oxides were even shorter, highlighting the unique resilience of MnO2 with respect to voltage fluctuations in acidic electrolytes.

Operando spectroscopic analysis of catalyst regeneration

To further confirm that the enhanced resilience of Mn oxide to voltage fluctuations was due to the incorporation of the charge comproportionation reaction in the OER cycle, we monitored the regeneration pathway using operando resonant Raman spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 11). In a sulfuric acid electrolyte, no changes in the Raman spectra of MnO2 were observed at potentials between open circuit potential and 1.73 V vs. RHE, indicating that Mn7+ is not produced from the MnO2 electrode at these potentials (Supplementary Fig. 11c). When the potential was increased to approximately 1.8 V vs. RHE, a new Raman peak assigned to Mn7+ was observed at 838 cm−1 after 15 min. However, this Raman peak disappeared completely within 30 min of adding phosphate even when the electrochemical potential was kept at 1.8 V vs. RHE. Concurrently, Mn3+ was detected via UV–Vis spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 12), confirming that the Guyard reaction was initiated by the addition of phosphate. Furthermore, the amount of Mn3+ in the electrolyte was fivefold lower than that expected if Mn7+ was completely converted to Mn3+, confirming that Mn3+ was reincorporated into the MnO2 electrode. This mechanism is fundamentally different from the self-healing materials proposed by Huynh et al.12, which operate via the anodic electrodeposition of lower-valence metal ions such as Mn2+ and Mn3+ (Supplementary Fig. 13). Unlike these ions, Mn7+ formed via oxidative dissolution has a higher oxidation state than the bulk oxide and thus cannot be regenerated through direct electrodeposition. Instead, Mn7+ regeneration occurs by reducing its high oxidation state through the Guyard reaction.

Discussion

The use of 3d-block metal catalysts for OER electrocatalysis is challenging due to the voltage fluctuations associated with renewable electricity, which lead to rapid catalyst deactivation. To address this issue, we incorporated the Guyard reaction into the redox cycle of MnO2 electrocatalysts. This enables Mn7+ ions to be redeposited on the electrode under anodic conditions, despite its oxidation state being higher than the bulk metal oxide. This strategy proved effective in enhancing catalyst longevity under fluctuating voltages, allowing the catalyst to sustain a high current density of 250 mA cm−2 in an acidic electrolyte due to repeated regeneration after every voltage pulse.

The rich redox chemistry of MnO2 is distinct from that of other metal oxides, such as cobalt, iron and nickel, whose stability could not be enhanced by the addition of phosphate (Fig. 5). Although Mn oxides have been considered insufficient as OER catalysts due to their lower activity than other 3d-block elements39,40, the exceptional resilience of MnO2 under fluctuating environments highlights its distinct advantage over other elements.

In particular, the voltage-fluctuation resilience of MnO2, along with recent advancements in acid-stable Mn-based catalysts for proton exchange membrane (PEM) water electrolysers, suggests its potential as a promising candidate for iridium-free or low-iridium-content OER catalysts for PEM electrolysers4,5,7,8. However, to date, the Guyard reaction has been demonstrated only at extremely low pH (6 M H2SO4)38 or in the presence of two inorganic ions, phosphate9,33,34,35 and oxalate35,36. Future research should therefore include the identification of stable additives capable of promoting the Guyard reaction. Such efforts are particularly important, as PEM electrolysers inherently experience voltage fluctuations when directly connected to intermittent power sources. The startup and shutdown cycles during industrial operation of PEM electrolysers are additional risks that may damage catalysts and other components. To enable the practical application of this self-healing concept in PEM systems, phosphate groups could be incorporated into the catalyst layer or partially substitute sulfonic acid groups in Nafion, potentially tuning the microenvironment to promote catalyst redeposition and durability.

The high resilience of Mn-based catalysts under fluctuating oxidative environments may also have been a deciding factor leading to its incorporation into the oxygen evolution complex of natural photosynthesis. The exclusive selection of manganese, despite the geological abundance of iron or the superior catalytic activity of cobalt39,40,41, has raised debates on the selection pressures that have favoured this element40,42,43,44,45,46,47. At least within the experimental scope of Fig. 5, Mn is more stable than other 3d elements by more than an order of magnitude due to the Guyard reaction, which induces unique feedback in the redox chemistry of Mn. As long as Mn oxide is active for the OER, there is a constant supply of Mn2+ (Fig. 1b), which allows dissolved Mn ions to be reincorporated into the catalytic centre. In particular, previous studies have proposed that nature has favoured stability over activity during the design of Photosystem II, such as the incorporation of regeneration mechanisms specific to the active site or the optimization of genetic structures to minimize the biosynthetic cost of the enzyme48. Although regeneration via the Guyard reaction is possible only when the oxide is active for the OER9, the possibility of repairing the OER catalyst would nonetheless have been a unique advantage for nature to choose Mn as the unique element over other 3d-block elements.

Methods

Electrode fabrication

MnO2 on an FTO substrate (7 Ω per sq surface resistivity, NPV-CFT2-7, AsOne) was synthesized via a thermal decomposition method. Briefly, 0.5 ml of 2 M Mn(NO3)2 was dropped onto a clean FTO-coated glass and then calcined on a hot plate at 250 °C in air for 6 h. The resulting electrode was rinsed with Milli-Q ultra-pure water (18.2 MΩ cm at 25 °C, Merck Millipore), sonicated for 10 s and then dried at 40 °C before measurements. A QCM electrode was prepared using a spray deposition method. Briefly, an Mn(NO3)2 solution (4 M) was sprayed onto clean QCM quartz crystals (platinum-coated, 10 MHz, Hokuto Denko Corp.), which were then heated at 250 °C for 12 h. MnO2 was deposited only within the platinum coated area (defined using a mask) of the QCM quartz crystal.

Kinetics analysis of the Guyard reaction

In situ UV–Vis absorption spectra were obtained in diffuse transmission mode using a UV–Vis spectrometer (UV-2550, Shimadzu) equipped with a multipurpose large-sample compartment with a built-in integrating sphere (MPC-2200, Shimadzu). The kinetics of the Guyard reaction (Mn7+ + 4 Mn2+ → 5 Mn3+) was studied spectrophotometrically by recording the time course of absorbance at 545 nm. For the in situ acquisition of spectra, the reactor was placed in front of the integrating sphere to collect the diffuse transmission light.

EPR measurement in parallel and perpendicular modes

EPR measurements were performed using a Bruker EMX/Plus spectrometer equipped with a parallel and perpendicular dual-mode cavity (ER 4116DM). The temperature was controlled using a liquid He quartz cryostat (Oxford Instruments ESR900) equipped with a temperature and gas flow controller (Oxford Instruments ITC503). The experimental conditions were as follows: microwave frequency, 9.64 GHz (perpendicular mode) and 9.38 GHz (parallel mode); modulation amplitude, 10 G; modulation frequency, 100 kHz; microwave power, 0.03 mW (perpendicular mode) and 5.2 mW (parallel mode); temperature, 4 K; and sweep time, 232 s (perpendicular mode) and 100 s (parallel mode). EPR spectra were collected for different Mn oxidation states using the following modes: Mn7+, [Ar]3d0, S = 0 (EPR silent in both modes); Mn2+ [Ar]3d5, S = 5/2 (EPR active in perpendicular mode); Mn3+, [Ar]3d4, S = 2 (EPR active in parallel mode).

X-ray absorption for oxidation state measurement

X-ray absorption spectra of the Mn K edge were recorded at the BL14B2 beamline of SPring-8. The analysis was performed on the Demeter software platform. The threshold energy (E0) was determined at the point where the corresponding normalized absorption was equal to 0.5 in an X-ray absorption near edge structure spectrum. The average valence state of Mn was calculated from the linear regression line obtained from standard samples, such as MnSO4, Mn2O3 and MnO2.

In situ resonance Raman measurement

Resonance Raman spectra were collected on a Raman microscopy system (Senterra, Bruker) using an excitation wavelength of 532 nm. The excitation light was focused on the sample using a microscope objective (Olympus LMPlanFL N ×50/0.5 BD long-focal length objective, 10.6 mm working distance) at a power of 0.5 mW to avoid damage induced by laser radiation. For the measurements, the laser was irradiated through an optical window and the electrolyte onto the working electrode surface.

Electrochemical measurements under fluctuation voltages

Current-versus-potential curves were obtained with a commercial potentiostat (HZ-5000, Hokuto Denko) at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C). MnO2 loaded on an FTO substrate (with a geometric surface area of 1 cm2) was used as the working electrode, and a Pt wire (99.98%, Nilaco) served as the counter electrode. The two electrodes were separated by a PEM (Nafion 117, Sigma-Aldrich), which effectively assists in transporting proton ions selectively from the anode to the cathode compartment. The anode chamber was equipped with two optical windows for in situ UV–Vis measurements and time-lapse recording. A sulfuric acid solution (pH 2, with 1.0 M K2SO4 as the supporting electrolyte) was used as a base electrolyte, and 1.0 M phosphate (pH 2, prepared using NaH2PO4 and H3PO4) was added to induce the Guyard reaction.

Cyclic voltammetry

Cyclic voltammetry measurements were conducted in a three-electrode cell. Ag/AgCl/KCl (saturated) was used as a reference electrode. Prior to every electrochemical experiment, the solution resistance was measured, and iR compensation was then performed manually. Electrode potentials after iR compensation were rescaled to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE).

QCM measurements

A set-up assembled with an HQ-601DK mass sensor (Hokuto Denko) was used for QCM measurements. The frequency changes (Δf) during OER were recorded. Mass changes (Δm) were calculated from Δf according to the Sauerbrey equation:

where f0 denotes the initial quartz crystal frequency (10 MHz), Apiezo is the area of the piezoelectrically active crystal (0.07 cm−2), μq is the shear modulus of quartz (2.947 × 1011 dyn cm−2) and ρq is the density of quartz (2.648 g cm−3). The mass sensitivity of the QCM was Δm/Δf = 0.31 ng Hz−1.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Verpoort, P. C., Gast, L., Hofmann, A. & Ueckerdt, F. Impact of global heterogeneity of renewable energy supply on heavy industrial production and green value chains. Nat. Energy 9, 491–503 (2024).

Kojima, H. et al. Influence of renewable energy power fluctuations on water electrolysis for green hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 4572–4593 (2023).

Alia, S. M., Stariha, S. & Borup, R. L. Electrolyzer durability at low catalyst loading and with dynamic operation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, F1164–F1172 (2019).

Li, A. et al. Atomically dispersed hexavalent iridium oxide from MnO2 reduction for oxygen evolution catalysis. Science 384, 666–670 (2024).

Hayashi, T., Bonnet-Mercier, N., Yamaguchi, A., Suetsugu, K. & Nakamura, R. Electrochemical characterization of manganese oxides as a water oxidation catalyst in proton exchange membrane electrolysers. R. Soc. Open Sci. 6, 190122 (2019).

Zhou, L. et al. Rutile alloys in the Mn–Sb–O system stabilize Mn3+ to enable oxygen evolution in strong acid. ACS Catal. 8, 10938–10948 (2018).

Kong, S. et al. Acid-stable manganese oxides for proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Nat. Catal. 7, 252–261 (2024).

Li, A. et al. Stable potential windows for long-term electrocatalysis by manganese oxides under acidic conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 5054–5058 (2019).

Ooka, H. et al. Microkinetic model to rationalize the lifetime of electrocatalysis: trade-off between activity and stability. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 10079–10085 (2024).

Speck, F. D., Santori, P. G., Jaouen, F. & Cherevko, S. Mechanisms of manganese oxide electrocatalysts degradation during oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution reactions. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 25267–25277 (2019).

Kong, S., Fushimi, K., Li, A. & Nakamura, R. Effects of dissolved 3d-block metal ions on PEM water electrolysis performance. Chem. Commun. 60, 14621–14624 (2024).

Huynh, M., Bediako, D. K. & Nocera, D. G. A functionally stable manganese oxide oxygen evolution catalyst in acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 6002–6010 (2014).

Deka, N. et al. On the operando structure of ruthenium oxides during the oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. ACS Catal. 13, 7488–7498 (2023).

Danilovic, N. et al. Activity–stability trends for the oxygen evolution reaction on monometallic oxides in acidic environments. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 2474–2478 (2014).

Cherevko, S. et al. Oxygen and hydrogen evolution reactions on Ru, RuO2, Ir, and IrO2 thin film electrodes in acidic and alkaline electrolytes: a comparative study on activity and stability. Catal. Today 262, 170–180 (2016).

Kasian, O., Grote, J.-P., Geiger, S., Cherevko, S. & Mayrhofer, K. J. J. The common intermediates of oxygen evolution and dissolution reactions during water electrolysis on iridium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 2488–2491 (2018).

Scott, S. L. A matter of life(time) and death. ACS Catal. 8, 8597–8599 (2018).

Spori, C., Kwan, J. T. H., Bonakdarpour, A., Wilkinson, D. P. & Strasser, P. The stability challenges of oxygen evolving catalysts: towards a common fundamental understanding and mitigation of catalyst degradation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 5994–6021 (2017).

Dam, A. P., Papakonstantinou, G. & Sundmacher, K. On the role of microkinetic network structure in the interplay between oxygen evolution reaction and catalyst dissolution. Sci. Rep. 10, 14140 (2020).

Priamushko, T. et al. Be aware of transient dissolution processes in Co3O4 acidic oxygen evolution reaction electrocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 3517–3528 (2025).

Park, S. et al. Spectroscopic capture of a low-spin Mn (IV)-oxo species in Ni–Mn3O4 nanoparticles during water oxidation catalysis. Nat. Commun. 11, 5230 (2020).

Jin, K. et al. Hydrated manganese (II) phosphate (Mn3(PO4)2·3H2O) as a water oxidation catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 7435–7443 (2014).

Jin, K. et al. Mechanistic investigation of water oxidation catalyzed by uniform, assembled MnO nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 2277–2285 (2017).

Takashima, T., Hashimoto, K. & Nakamura, R. Mechanisms of pH-dependent activity for water oxidation to molecular oxygen by MnO2 electrocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 1519–1527 (2012).

Takashima, T., Hashimoto, K. & Nakamura, R. Inhibition of charge disproportionation of MnO2 electrocatalysts for efficient water oxidation under neutral conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18153–18156 (2012).

Gorlin, Y. et al. In situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy investigation of a bifunctional manganese oxide catalyst with high activity for electrochemical water oxidation and oxygen reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 8525–8534 (2013).

Gorlin, Y. & Jaramillo, T. F. Investigation of surface oxidation processes on manganese oxide electrocatalysts using electrochemical methods and ex situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 159, H782 (2012).

Indra, A. et al. Active mixed-valent MnOx water oxidation catalysts through partial oxidation (corrosion) of nanostructured MnO particles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 13206–13210 (2013).

Bard, A. Standard Potentials in Aqueous Solution (Routledge, 2017).

Robinson, D. M. et al. Photochemical water oxidation by crystalline polymorphs of manganese oxides: structural requirements for catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 3494–3501 (2013).

Zhang, B. et al. Identifying MnVII-oxo species during electrochemical water oxidation by manganese oxide. iScience 4, 144–152 (2018).

Guyard, A. Of the direct determination of manganese, antimony and uranium by the volumetric method and of several compounds of these metals. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1, 89–95 (1864).

Orban, M. & Epstein, I. R. Systematic design of chemical oscillators. 59. Minimal permanganate oscillator: the Guyard reaction in a CSTR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111, 8543–8544 (1989).

Mrákavová, M. & Treindl, Ł Kinetics of Guyard’s reaction with regard to permanganate chemical oscillators. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 55, 2898–2903 (1990).

Powell, R. T., Oskin, T. & Ganapathisubramanian, N. Permanganate oxidation of Mn(II) in aqueous acidic solutions in the presence of oxalate and pyrophosphate. J. Phys. Chem. 93, 2718–2721 (1989).

Kovács, K. A., Gróf, P., Burai, L. & Riedel, M. Revising the mechanism of the permanganate/oxalate reaction. J. Phys. Chem. A 108, 11026–11031 (2004).

Adler, S. J. & Noyes, R. M. The mechanism of the permanganate-oxalate reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 77, 2036–2042 (1955).

Fenton, A. & Furman, N. Current and titration efficiencies of electrically generated manganic ion: ferric-manganous sulfate dual intermediate system. Anal. Chem. 32, 748–752 (1960).

Man, I. C. et al. Universality in oxygen evolution electrocatalysis on oxide surfaces. ChemCatChem 3, 1159–1165 (2011).

Gates, C. et al. Why did nature choose manganese over cobalt to make oxygen photosynthetically on the Earth?. J. Phys. Chem. B 126, 3257–3268 (2022).

Li, A. et al. Enhancing the stability of cobalt spinel oxide towards sustainable oxygen evolution in acid. Nat. Catal. 5, 109–118 (2022).

Armstrong, F. A. Why did Nature choose manganese to make oxygen? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 363, 1263–1270 (2008).

Hayashi, T., Yamaguchi, A., Hashimoto, K. & Nakamura, R. Stability of organic compounds on the oxygen-evolving center of photosystem II and manganese oxide water oxidation catalysts. Chem. Commun. 52, 13760–13763 (2016).

Chernev, P. et al. Light-driven formation of manganese oxide by today’s photosystem II supports evolutionarily ancient manganese-oxidizing photosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 11, 6110 (2020).

Shimada, Y. et al. Post-translational amino acid conversion in photosystem II as a possible origin of photosynthetic oxygen evolution. Nat. Commun. 13, 4211 (2022).

Sauer, K. & Yachandra, V. K. A possible evolutionary origin for the Mn4 cluster of the photosynthetic water oxidation complex from natural MnO2 precipitates in the early ocean. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 8631–8636 (2002).

Ooka, H., Takashima, T., Yamaguchi, A., Hayashi, T. & Nakamura, R. Element strategy of oxygen evolution electrocatalysis based on in situ spectroelectrochemistry. Chem. Commun. 53, 7149–7161 (2017).

Ooka, H., Hashimoto, K. & Nakamura, R. Design strategy of multi-electron transfer catalysts based on a bioinformatic analysis of oxygen evolution and reduction enzymes. Mol. Inform. 37, 1700139 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank H. Ofuchi for giving support in conducting the X-ray absorption fine structure measurements at BL14B2 (XAFS) of SPring-8 with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (proposal no. 2021B1856), K. Kato and K. Shigeta for their support with SR-PXRD experiments at BL44B2 of SPring-8 (proposal no. 20250032), and T. Kaneko and T. Uruga for their support with X-ray absorption fine structure measurements at BL36XU of SPring-8 (proposal no. 2025A1386). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy measurements were performed at BL17SU of SPring-8 (proposal no. 20250032). We also thank M. Arfaoui (Materials Characterization Support Team, CEMS, RIKEN) for conducting the transmission electron microscopy measurements. We acknowledge D. Shin for the EPR measurements. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Kakenhi Grant No. 22H00339), GteX Program Japan (grant no. JPMJGX23H2) and the MEXT Program: Data Creation and Utilization-Type Material Research and Development Project (grant no. JPMXP1122712807).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.L. and R.N. conceived and designed the experiments. A.L., S.K., K.A., Y.Z., K.F., S.H., M.O. and S.H.K. performed the experiments. A.L., H.O., S.K., K.A., D.H., S.H.K. and R.N. analysed the data. A.L., H.O. and R.N. wrote the paper. All the authors discussed the results and reviewed the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Tatiana Priamushko, Sergio Rojas and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–13.

Supplementary Video 1

OER without regeneration under fluctuation without phosphate.

Supplementary Video 2

OER with regeneration under fluctuation.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, A., Ooka, H., Kong, S. et al. Oxygen evolution electrocatalysis resilient to voltage fluctuations. Nat Sustain 8, 1533–1540 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01665-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01665-y

This article is cited by

-

Harvesting intermittent energy

Nature Sustainability (2025)