Abstract

In a p–n junction, the separation of positive and negative charges leads to diode transport, in which charge flows in only one direction. Non-centrosymmetric polar conductors are intrinsic diodes that could be of use in the development of nonlinear applications. Such systems have recently been extended to non-centrosymmetric superconductors, and the superconducting diode effect has been observed. Here, we report an antiferromagnetic diode effect in a centrosymmetric crystal without directional charge separation. We observed large second-harmonic transport in a nonlinear electronic device enabled by the compensated antiferromagnetic state of even-layered MnBi2Te4. We show that this antiferromagnetic diode effect can be used to create in-plane field-effect transistors and microwave-energy-harvesting devices. We also show that electrical sum-frequency generation can be used as a tool to detect nonlinear responses in quantum materials.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. Further data related to this work are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

The computer code used in this study is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Lee, P. A., Nagaosa, N. & Wen, X.-G. Doping a Mott insulator: physics of high-temperature superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1, 17–84 (2006).

Mong, R. S., Essin, A. M. & Moore, J. E. Antiferromagnetic topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 81, 245209 (2010).

Tang, P., Zhou, Q., Xu, G. & Zhang, S.-C. Dirac fermions in an antiferromagnetic semimetal. Nat. Phys. 12, 1100–1104 (2016).

Essin, A. M., Moore, J. E. & Vanderbilt, D. Magnetoelectric polarizability and axion electrodynamics in crystalline insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 146805 (2009).

Jungwirth, T., Marti, X., Wadley, P. & Wunderlich, J. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 231–241 (2016).

Rikken, G., Fölling, J. & Wyder, P. Electrical magnetochiral anisotropy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 236602 (2001).

Tokura, Y. & Nagaosa, N. Nonreciprocal responses from non-centrosymmetric quantum materials. Nat. Commun. 9, 3740 (2018).

Orenstein, J. et al. Topology and symmetry of quantum materials via nonlinear optical responses. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 12, 247–272 (2021).

Sodemann, I. & Fu, L. Quantum nonlinear Hall effect induced by Berry curvature dipole in time-reversal invariant materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 216806 (2015).

Ideue, T. et al. Bulk rectification effect in a polar semiconductor. Nat. Phys. 13, 578–583 (2017).

Yasuda, K. et al. Large unidirectional magnetoresistance in a magnetic topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 127202 (2016).

Godinho, J. et al. Electrically induced and detected Néel vector reversal in a collinear antiferromagnet. Nat. Commun. 9, 4686 (2018).

Ma, Q. et al. Observation of the nonlinear Hall effect under time-reversal-symmetric conditions. Nature 565, 337–342 (2019).

Kang, K., Li, T., Sohn, E., Shan, J. & Mak, K. F. Nonlinear anomalous Hall effect in few-layer WTe2. Nat. Mater. 18, 324–328 (2019).

Kumar, D. et al. Room-temperature nonlinear Hall effect and wireless radiofrequency rectification in Weyl semimetal TaIrTe4. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 421–425 (2021).

Isobe, H., Xu, S.-Y. & Fu, L. High-frequency rectification via chiral Bloch electrons. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay2497 (2020).

Zhao, W. et al. Magnetic proximity and nonreciprocal current switching in a monolayer WTe2 helical edge. Nat. Mater. 19, 503–507 (2020).

Tsirkin, S. & Souza, I. On the separation of Hall and ohmic nonlinear responses. SciPost Phys. Core 5, 039 (2022).

He, P. et al. Graphene moiré superlattices with giant quantum nonlinearity of chiral Bloch electrons. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 378–383 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Non-reciprocal charge transport in an intrinsic magnetic topological insulator MnBi2Te4. Nat. Commun. 13, 6191 (2022).

Wu, H. et al. The field-free Josephson diode in a van der Waals heterostructure. Nature 604, 653–656 (2022).

Gao, A. et al. Quantum metric nonlinear Hall effect in a topological antiferromagnetic heterostructure. Science 381, 181–186 (2023).

Wang, N. et al. Quantum-metric-induced nonlinear transport in a topological antiferromagnet. Nature 621, 487–492 (2023).

Zhang, C.-P., Gao, X.-J., Xie, Y.-M., Po, H. C. & Law, K. T. Higher-order nonlinear anomalous Hall effects induced by Berry curvature multipoles. Phys. Rev. B 107, 115142 (2023).

Wang, C., Gao, Y. & Xiao, D. Intrinsic nonlinear Hall effect in antiferromagnetic tetragonal CuMnAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 277201 (2021).

Liu, H. et al. Intrinsic second-order anomalous Hall effect and its application in compensated anti-ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 277202 (2021).

Holder, T., Kaplan, D., Ilan, R. & Yan, B. Mixed axial-gravitational anomaly from emergent curved spacetime in nonlinear charge transport. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2111.07780 (2021).

Lahiri, S., Das, K., Culcer, D. & Agarwal, A. Intrinsic nonlinear conductivity induced by the quantum metric dipole. Phys. Rev. B 108, L201405 (2023).

Smith, T. B., Pullasseri, L. & Srivastava, A. Momentum-space gravity from the quantum geometry and entropy of Bloch electrons. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 013217 (2022).

Ma, D., Arora, A., Vignale, G. & Song, J. C. Anomalous skew-scattering nonlinear Hall effect and chiral photocurrents in \({{{\mathcal{PT}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 076601 (2023).

Zhang, N. J. et al. Angle-resolved transport non-reciprocity and spontaneous symmetry breaking in twisted trilayer graphene. Nat. Mater. 23, 356–362 (2024).

Kaplan, D., Holder, T. & Yan, B. Unification of nonlinear anomalous Hall effect and nonreciprocal magnetoresistance in metals by the quantum geometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 026301 (2024).

Huang, Y.-X. et al. Nonlinear current response of two-dimensional systems under in-plane magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 108, 075155 (2023).

Huang, Y.-X., Xiao, C., Yang, S. & Li, X. Scaling law for time-reversal-odd nonlinear transport. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.01219 (2023).

Atencia, R. B., Xiao, D. & Culcer, D. Disorder in the non-linear anomalous Hall effect of \({{{\mathcal{PT}}}}\)-symmetric Dirac fermions. Phys. Rev. B 108, L201115 (2023).

Kaplan, D., Holder, T. & Yan, B. General nonlinear Hall current in magnetic insulators beyond the quantum anomalous Hall effect. Nat. Commun. 14, 3053 (2023).

Otrokov, M. M. et al. Prediction and observation of an antiferromagnetic topological insulator. Nature 576, 416–422 (2019).

Deng, Y. et al. Quantum anomalous Hall effect in intrinsic magnetic topological insulator MnBi2Te4. Science 367, 895–900 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. Robust axion insulator and Chern insulator phases in a two-dimensional antiferromagnetic topological insulator. Nat. Mater. 19, 522–527 (2020).

Trang, C. X. et al. Crossover from 2D ferromagnetic insulator to wide bandgap quantum anomalous Hall insulator in ultra-thin MnBi2Te4. ACS Nano 15, 13444–13452 (2021).

Deng, H. et al. High-temperature quantum anomalous Hall regime in a MnBi2Te4/Bi2Te3 superlattice. Nat. Phys. 17, 36–42 (2021).

Gao, A. et al. Layer Hall effect in a 2D topological axion antiferromagnet. Nature 595, 521–525 (2021).

Cai, J. et al. Electric control of a canted-antiferromagnetic Chern insulator. Nat. Commun. 13, 1668 (2022).

Beidenkopf, H. et al. Spatial fluctuations of helical Dirac fermions on the surface of topological insulators. Nat. Phys. 7, 939–943 (2011).

Qiu, J.-X. et al. Axion optical induction of antiferromagnetic order. Nat. Mater. 22, 583–590 (2023).

Iyama, A. & Kimura, T. Magnetoelectric hysteresis loops in Cr2O3 at room temperature. Phys. Rev. B 87, 180408 (2013).

Ahn, J., Xu, S.-Y. & Vishwanath, A. Theory of optical axion electrodynamics and application to the Kerr effect in topological antiferromagnets. Nat. Commun. 13, 7615 (2022).

Fujimoto, T. et al. Observation of terahertz spin Hall conductivity spectrum in GaAs with optical spin injection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 016301 (2023).

Orenstein, J. Optical nonreciprocity in magnetic structures related to high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 067002 (2011).

Varma, C. Gyrotropic birefringence in the underdoped cuprates. Europhys. Lett. 106, 27001 (2014).

Yan, J.-Q. et al. Crystal growth and magnetic structure of MnBi2Te4. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 064202 (2019).

Hsieh, D. et al. Selective probing of photoinduced charge and spin dynamics in the bulk and surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 077401 (2011).

Vool, U. et al. Imaging phonon-mediated hydrodynamic flow in WTe2. Nat. Phys. 17, 1216–1220 (2021).

Thiel, L. et al. Probing magnetism in 2D materials at the nanoscale with single-spin microscopy. Science 364, 973–976 (2019).

Steiner, S., Khmelevskyi, S., Marsmann, M. & Kresse, G. Calculation of the magnetic anisotropy with projected-augmented-wave methodology and the case study of disordered Fe1−xCox alloys. Phys. Rev. B 93, 224425 (2016).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Pizzi, G. et al. Wannier90 as a community code: new features and applications. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 32, 165902 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Y. Gao, C. Xiao, A. Agarwal, J. Ahn, S. Yang, F. de Juan and I. Sodemann for helpful discussions. The work in S.Y.X.’s group was partly supported through the Center for the Advancement of Topological Semimetals, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science (fabrication and measurements), through the Ames National Laboratory (Contract No. DE-AC-0207CH11358) and partly through the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (Grant No. FA9550-23-1-0040 for data analysis and manuscript writing). S.Y.X. acknowledges the Corning Fund for Faculty Development and support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. S.Y.X. and D.B. were supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF; Career Grant No. DMR-2143177). C.T. and Z.S. acknowledge support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (Project Nos. P2EZP2 191801 and P500PT 206914, respectively). Y.F.L., S.Y.X., D.C.B., Y.O. and L.F. were supported by the Science and Technology Center for Integrated Quantum Materials (NSF Grant No. DMR-1231319). This work was performed in part at the Center for Nanoscale Systems, Harvard University, a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Network, which is supported by the NSF (Award No. ECCS-2025158). Bulk single-crystal growth and characterization of MnBi2Te4 were performed at the University of California, Los Angeles, and were supported by the DOE, Office of Science (Award No. DE-SC0021117). The work at Northeastern University was supported by the NSF through NSF-ExpandQISE (Award No. 2329067), and it benefited from the resources of Northeastern University’s Advanced Scientific Computation Center and the Discovery Cluster and of the Quantum Materials and Sensing Institute. The work in Q.M.’s group was supported through the Center for the Advancement of Topological Semimetals, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the DOE, Office of Science, through the Ames National Laboratory (Contract No. DE-AC02-07CH11358 for sample fabrication) and was partly supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (Grant No. FA9550-22-1-0270 for manuscript writing) and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. L.F. and Q.M. also acknowledge support from the NSF Convergence programme (NSF ITE-2345084) and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. T.R.C. was supported by the 2030 Cross-Generation Young Scholars Programme from the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (Programme No. MOST111-2628-M-006-003-MY3), National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan, and the National Center for Theoretical Sciences, Taiwan. T.R.C. thanks the National Center for High-performance Computing of the National Applied Research Laboratories, Taiwan, for providing computational and storage resources. This research was supported, in part, by the Higher Education Sprout Project, Ministry of Education, to the Headquarters of University Advancement at National Cheng Kung University. H.L. acknowledges the support of the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (Grant No. MOST 111-2112-M-001-057-MY3). The work at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, was supported by the Department of Atomic Energy of the Government of India (Project No. 12-R&D-TFR-5.10-0100) and benefited from the computational resources of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai. K.W. and T.T. acknowledge support from the JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Nos. 21H05233 and 23H02052) and World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI), MEXT, Japan. S.W.C. acknowledges partial support from the Harvard Quantum Initiative in Science and Engineering.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y.X. conceived and supervised the project. A.G. fabricated the devices and performed the transport measurements with help from Y.F.L., J.X.Q., D.B., T.D., H.C.L., C.T., Z.S., S.C.H., T.H., D.C.B. and Q.M. A.G., S.W.C. and S.P. performed the microwave rectification and NV experiments with help from A.Y. A.G. and J.X.Q. performed the optical CD measurement. A.G. performed the SHG measurements with help from C.T., H.C.L., J.X.Q. and Y.F.L. C.H., T.Q. and N.N. grew the bulk MnBi2Te4 single crystals. B.G. completed the theoretical studies including first-principles calculations with help from Y.O. and under the guidance of B.S., A.B., H.L., L.F. and T.R.C. K.W. and T.T. grew the bulk h-BN single crystals. S.Y.X., A.G. and Q.M. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Electronics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

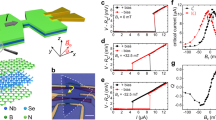

Extended Data Fig. 1 The asymmetric band contours induced by AFM spins in 6SL MnBi2Te4 at Fermi energy Ef = 0.2 eV.

a, The band contours of the Dirac surface states without AFM order. The band contour is symmetric for momentum ± k. ± kx and ± ky are the momentum along x and y direction. b, The band contours of the Dirac surface states for opposite AFM states. The AFM spins make the band to be ± ky asymmetric. This AFM spin-induced asymmetry is opposite for opposite AFM states. This explains the observation that the AFM diode effect signal is opposite for opposite AFM states shown in Figs. 2e–f, 4f and Extended Data Fig. 4.

Extended Data Fig. 2 The fully compensated antiferromagnetism for 6SL MnBi2Te4.

a, b, NV center magnetometry measurement for even- and odd-layered MnBi2Te4 (outlined by blue and red dashed lines in the optical image of the sample in (a)). The magnetization is only observed in odd-layered MnBi2Te4 and negligible in even-layered MnBi2Te4. The cyan dotted line denotes the line cut data shown in Fig. 1e.

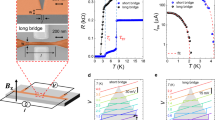

Extended Data Fig. 3 The linear and nonlinear signals for opposite AFM states in a 6SL MnBi2Te4.

a, c, At a finite external magnetic field μ0Hz field, AFM-I state can be prepared by sweeping μ0Hz from -8 T to 0 T (panel a); AFM-II state can be prepared by sweeping μ0Hz from +8 T to 0 T (panel c). b, The linear longitudinal voltage \({{{{\rm{V}}}}}_{\parallel }^{\omega }\) as a function of injection current for AFM-I. d, Same as (panel b) but for AFM-II. For different AFM states, the linear signal is the same. These data were taken from Device A and the current was along 30∘ in Fig. 2g.

Extended Data Fig. 4 AFM order determined nonlinear signal.

a, Nonlinear voltage V2ω as a function of z-direction external magnetic field μ0Hz. V2ω is opposite for two AFM orders (∣μ0H∣ < 2 T). The red and blue circles denote the two opposite V2ω at μ0H = 0 T. b, The nonlinear voltage difference \(({{{{\rm{diff}}}}}_{{V}^{2\omega }}=\frac{1}{2}({V}_{{{{\rm{AFM}}}}-{{{\rm{I}}}}}^{2\omega }-{V}_{{{{\rm{AFM}}}}-{{{\rm{II}}}}}^{2\omega }))\) between two AFM orders as a function of μ0H.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The temperature dependence of the nonlinear signal.

a, b, Nonlinear conductivity \({V}_{yxx}^{2\omega }\) and square of linear conductivity \({({\sigma }_{xx}^{\;\omega })}^{2}\) as a function of temperature. \({\sigma }_{yxx}^{2\omega }\) and \({({\sigma }_{xx}^{\;\omega })}^{2}\) show a similar temperature dependence.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Nonlinear voltage versus current direction.

a, b, Longitudinal and transverse nonlinear voltage when the current is injected along x (panel a) and along y (panel b). A crystalline axes is along x in Device A (Fig. 2g,h).

Extended Data Fig. 7 DFT calculated band structure of 6SL MnBi2Te4.

a, Band structure of 6SL MnBi2Te4 in ky direction. b, DFT calculated band contours at specific energies (0.05 eV and 0.10 eV), marked with dashed lines in panel (a). The low energy Dirac bands show dramatic asymmetry between + ky and − ky. c, DFT calculated nonlinear conductivity σ2ω as a function of Fermi level Ef. We obtained the relaxation time τ = 2.1 × 10−14 s based on the Drude conductivity. We note that our calculations are based on the DFT band structure of 6SL MnBi2Te4, which predicts a magnetic gap ~ 50 meV. However, experimentally, the gap size is not settled37,40. In particular, spatial inhomogeneity can smear out the magnetic gap44. Moreover, the antisite defects could suppress the band gap and can increase the quantum metric effect, as predicted in Ref. 32.

Extended Data Fig. 8 The exchange property of transverse conductance.

a, b, Schematics of two different types of linear transverse conductance, the Hall effect (panel a) and the anisotropy induced transverse signal (panel b). The Hall effect occurs due to external magnetic field or internal magnetization. The anisotropy induced transverse signal occurs due to crystalline anisotropy (for example orthorhombic or monoclinic). These two different mechanisms can be distinguished by their exchange properties. The Hall effect is antisymmetric (σxy = − σyx), whereas the anisotropy induce transverse signal is symmetric (σxy = σyx). c, d, Schematic of nonlinear Hall signal (panel c) and the transverse component of the AFM diode signal (panel d). The nonlinear Hall signal is antisymmetric (σyxx = − σxyx), while the AFM diode signal is symmetric (σyxx = σxyx).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Electrical sum-frequency generation (SFG) measurement for 6SL MnBi2Te4.

a, b, Schematic for \({V}_{yxx}^{\;{\omega }_{1}+{\omega }_{2}}\) and \({V}_{xyx}^{\;{\omega }_{1}+{\omega }_{2}}\) measurements, respectively. ω1 = 547.1 Hz and ω2 = 1.77 Hz were used in the measurement. The capacitor and inductor were used to define the current trajectory for \({I}^{{\omega }_{1}}\) and \({I}^{{\omega }_{2}}\) (see Methods for more details).

Extended Data Fig. 10 In-plane field effect in another 6SL MnBi2Te4 device.

a, Measured change of resistance \({R}_{xx}(\Delta {R}_{xx}={V}_{x}^{\;{\omega }_{1}}/{I}_{x}^{\;{\omega }_{1}})\) as a function of an electric field bias along \({V}_{y}^{{{\;{\rm{DC}}}}}\). b, Temperature dependence of ΔRxx.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 and Discussion.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Source data for Fig. 1.

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data for Fig. 2.

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data for Fig. 3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Source data for Fig. 4.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, A., Chen, SW., Ghosh, B. et al. An antiferromagnetic diode effect in even-layered MnBi2Te4. Nat Electron 7, 751–759 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-024-01219-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-024-01219-8

This article is cited by

-

Systematic cRPA study of two-dimensional MA2Z4 materials: from unconventional screening to correlation-driven instabilities

npj Computational Materials (2025)

-

Intrinsic magnetic topological insulators of the MnBi2Te4 family

Communications Materials (2025)

-

Configurable antiferromagnetic domains and lateral exchange bias in atomically thin CrPS4

Nature Materials (2025)

-

Nonlinear transport in non-centrosymmetric systems

Nature Materials (2025)

-

Nonvolatile electrical switching of nonreciprocal transport in ferroelectric polar metal WTe2

Nature Communications (2025)