Abstract

Synthetic fuels are promising candidates for achieving carbon neutrality and lowering soot formation. However, their combustion leads to notable amounts of formaldehyde and other oxygenates. These emissions further affect the selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NOx and cause secondary HCN emissions due to their reaction with NH3. This study focuses on elucidating the structural features of Cu-SSZ-13—a widely applied NH3-SCR catalyst—that lead to high formaldehyde conversion while minimizing HCN emissions. Complementary in situ/operando characterization techniques supported by density functional theory calculations are systematically applied for a series of Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts with different Cu loadings and Si/Al ratios. The obtained results demonstrate that the decrease in SCR activity due to the presence of HCHO correlates with the formation of mobile Cu–CN species, whereas low HCN emissions at >350 °C are associated with the presence of ZCuOH species in the catalyst structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Synthetic fuels generated via the conversion of CO2 with renewable hydrogen are promising contributors to attaining carbon neutrality and high-density energy storage1,2. Furthermore, their combustion leads to the same efficiency as that obtained with state-of-the-art diesel engines, and less soot formation is observed3. Biomethane obtained from biomass and synthetic methane obtained by CO2 hydrogenation with green hydrogen are also considered important, since about 20% less CO2 is emitted during the combustion of CH4 compared with that of conventional fuels. Nevertheless, a catalytic after-treatment system is still required in both cases (for example, for hydrocarbon oxidation and NOx removal)3,4. Due to the incomplete combustion of alternative fuels such as biomethane and oxymethylene ethers, emissions of hazardous oxygenates besides CO and NOx are expected5. Herein, formaldehyde (HCHO) is a problematic pollutant6,7,8 since its complete suppression over standard oxidation catalysts is unlikely due to external diffusion limitations9 and catalyst inhibition in complex gas mixtures10,11. Additionally, secondary emissions such as HCHO can be generated directly over a deteriorated catalytic system by partial oxidation of hydrocarbons9,11,12,13.

Recent studies have shown that HCHO strongly influences the activity of all typical catalysts used for the selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NOx with NH3, leading to their deactivation and the formation of high emissions of toxic HCN14,15,16. Whereas most investigations on HCN formation agree that this process involves a reaction between HCHO and NH3 on the catalyst surface14,15,16,17,18,19, further mechanistic details are still debated, especially considering the different classes of catalysts. For Fe-exchanged ZSM-5 zeolites, a reaction pathway via formates towards formamide was proposed at low temperatures14. Furthermore, the formation of HCN by formamide decomposition was reported by Kröcher et al.16,20 over V2O5/WO3–TiO2 catalysts when this compound was tested as an NH3 precursor.

An alternative path without previous formation of formates was suggested more recently by the same group18. Their diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) investigations showed the formation of amide species through the reaction of gas-phase formaldehyde with pre-adsorbed NH3, which eventually decomposed to HCN. Based on in situ Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) measurements, Ngo et al.15,17 further suggested that the generation of HCN emissions over the V2O5/WO3–TiO2 catalyst involves the formation of HCONH2 via a Mars–van Krevelen mechanism, followed by its decomposition. At low temperatures, vibrational bands associated with hexamethylenetetramine formation were detected, which were linked to the appearance of HCN emissions as well15. Similar vibrational bands were later detected for commercial Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts and were connected to the mechanism for HCN formation over this system19. Whereas a decrease in NOx removal activity due to the presence of formaldehyde was observed for the VWTi and Fe-exchanged zeolite catalysts at higher temperatures, HCN emissions were detected over a wider temperature range. In contrast, the catalytic activity of Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts seems to only be affected at temperatures below 350 °C (refs. 14,19). Furthermore, HCN emissions diminish with increasing temperature, making this catalytic system particularly interesting for avoiding these undesired emissions14.

Cu-exchanged small-pore zeolites such as Cu-SSZ-13 are generally the system of choice for NOx removal if their application requires both high low-temperature activity and thermal stability. Such catalysts are also known for the characteristic seagull-shaped activity profile21,22, which is assumed to be caused by two different reaction mechanisms occurring within different temperature ranges23. At temperatures below 350 °C, the reduction of Cu2+ to Cu+ occurs readily in the SCR mixture, but re-oxidation of Cu+ is slow and thought to be the rate-limiting step. Under these conditions, the copper ions are expected to be solvated by NH3 (refs. 24,25,26). This process promotes their removal from the ion exchange sites and makes them mobile within the zeolite framework. Such mobile species are thought to be able to activate O2 molecules by the formation of µ-η2:η2-peroxodiamino di-copper complexes23,27,28. However, at temperatures above 350 °C these species are not stable and the copper ions are rebound to the exchange sites of the zeolite framework29,30. In this temperature range, activation of the O2 molecules is also possible on copper single sites31,32,33.

Depending on the copper loading and the Si/Al ratio in the zeolite framework, different Cu sites can be formed. The thermodynamically favoured copper sites (Z2Cu) are generated at low copper loadings and/or low Si/Al ratios34,35. In this case, Cu2+ ions are linked to six-membered rings containing two framework Al centres. In this way, complete charge compensation is achieved by the framework. Once all six-membered rings containing two framework Al centres are saturated by copper ions, another Cu species forms in the eight-membered rings containing one Al centre. This is preferentially formed at high copper loadings and high Si/Al ratios. Since only one Al centre is available, the remaining charge of a Cu2+ ion is compensated by the addition of an OH− group, resulting in the formation of ZCuOH sites36. Although both sites are active in NH3-SCR at high temperatures, it has been shown that ZCuOH sites are more likely to be reduced and tend to be more active in the oxidation of NH337,38.

In this context, this study focuses on understanding the impact of HCHO presence on the activity of the different copper sites and associated HCN emissions during the SCR of NOx over a series of Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts. The experimental results show significant differences in terms of activity and selectivity depending on the Cu loading and Si/Al ratio in the zeolite framework. Using operando X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), in situ DRIFTS, diffuse reflectance ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy and density functional theory (DFT) calculations, the necessary structural characteristics of Cu species for low HCN emissions were identified, which are essential for the future application of Cu-SSZ-13 as an emission control catalyst for synthetic fuel or biomethane combustion engines.

Results

Influence of catalyst composition

Six Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts with an Si/Al ratio of either 7 or 14 and a Cu loading of 0.5, 1.3 or 1.8 wt.% (hereafter referred to as Cu-SSZ-13 followed by parentheses containing the Si/Al ratio and the Cu loading, separated by a forward solidus) were prepared to evaluate the role of different Cu species during HCHO conversion and HCN formation. 27Al magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR investigations of the commercial zeolites (Supplementary Fig. 1) indicated the absence of extra-framework Al for both samples. The spectra of the as-received zeolites showed a sharp peak at 54 ppm corresponding to tetrahedrally coordinated Al (framework), whereas the fingerprint of octahedrally coordinated Al (the extra framework) was missing at 0 ppm39. No changes in the zeolite structure and the absence of CuOx reflexes were observed in the corresponding X-ray diffraction patterns after the ion exchange step (Supplementary Fig. 2). The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDXS) maps of the as-prepared samples confirmed the homogeneous distribution of Cu species (Supplementary Fig. 3). According to the Fourier transform extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS) data collected for Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) catalysts after dehydration at 500 °C in 10% O2/He (Supplementary Fig. 5), Cu is present as small entities mostly located at the ion exchange sites in the zeolite framework, which is in line with previous literature on similar catalyst compositions22,40,41. This was indicated by the rather low intensity of the second coordination sphere around 2.6 Å. Additional N2 physisorption measurements using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller isotherm showed a surface area of ∼730 m2 g−1 (±20 m2 g−1) and a pore volume of ∼0.3 cm3 g−1 for all prepared catalysts (Supplementary Table 2). This similarity was corroborated by the accessible inner surface and the absence of CuOx clusters inside the zeolite pores.

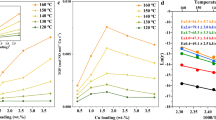

Steady-state experiments during NO SCR by NH3 in the presence or absence of HCHO were conducted for the entire catalyst series (Fig. 1) between 200 and 500 °C. In the absence of HCHO, the SCR activity increased with increased Cu loading, whereas a slightly higher low-temperature activity was observed for the catalysts with an Si/Al ratio of 7. With the exception of the samples with the lowest Cu loading (Cu-SSZ-13 (7/0.5) (Fig. 1a) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/0.5) (Fig. 1b)) all catalysts showed high NO conversion (>80%) above 200 °C. The different activity of these samples below and above 350 °C can be attributed to the high average Cu–Cu distance and therefore low probability of oxygen-bridged Cu dimer formation22,27. Particularly at low temperatures, the formation of O2−[CuI(NH3)2]+ during the oxidation half-cycle of the SCR cycle23 is slow for isolated Cu sites. This was also visible in the decrease of the normalized reaction rate with lower Cu loadings (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4). In addition to the Cu loading, variation in the Si/Al ratio has been shown to affect the fraction of Lewis and Brønsted acid sites, which have different NH3 adsorption properties and activity contributions in the low- and high-temperature SCR windows42. Accordingly, a poor low-temperature activity with an inflection point around 350 °C was noticed for the 0.5 wt.% Cu samples tested in this study, with a lower activity exhibited by the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/0.5) catalyst that is expected to contain a smaller number of Brønsted acid sites.

a–f, Conversion of NOx (black lines) and NH3 (red lines) in the absence (dashed lines) and presence (solid lines) of formaldehyde over the catalysts Cu-SSZ-13 (7/0.5) (a), Cu-SSZ-13 (14/0.5) (b), Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) (c), Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) (d), Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.8) (e) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.8) (f) at various temperatures. The grey bars represent the emission of HCN during SCR in the presence of HCHO (right y axis). The gas composition was 350 ppm NO, 350 ppm NH3, 0–100 ppm HCHO, 0.5% H2O and 10% O2 in He.

For the intermediate (Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) (Fig. 1c) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) (Fig. 1d)) and highest Cu loadings (Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.8) (Fig. 1e) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.8) (Fig. 1f)), a high NOx conversion was already reached at 250 °C. This was maintained at elevated temperatures, after a small inflection point around 350 °C for the samples containing 1.3 wt.% Cu. At the same time, only the samples with an Si/Al ratio of 14 (Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) (Fig. 1d) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.8) (Fig. 1f)) exhibited slight NH3 overconsumption due to oxidation at high temperatures (>450 °C).

During HCHO dosing, distinct effects were observed for the two SCR regions below and above 350 °C, formerly assigned to the seagull inflection point21,22,43. All investigated catalysts showed a pronounced decrease of the low-temperature SCR activity, leading to an NO conversion below 40%. Above 350 °C, the SCR activity seemed to be regained, but high NH3 overconsumption was observed for the catalysts with an Si/Al ratio of 7. A general increase in HCN formation was observed for all catalysts up to 350 °C, which correlates with the similar state of Cu species due to solvation by NH3 and H2O25,26. At higher temperatures, the solvation extent decreases as NH3 and H2O gradually desorb26,44, and the fingerprint of the different Cu structures at the ion exchange positions of the zeolite becomes visible. Consequently, for the two selected Si/Al ratios of the Cu-SSZ-13 samples, a clear variation in HCN emissions was noticed. For the catalysts with the Si/Al ratio of 7 (Fig. 1a,c,e), HCN emissions above 350 °C seemed to stagnate at rather high values with the increase in temperature. In contrast, the catalysts with an Si/Al ratio of 14 (Fig. 1b,d,f) showed a strong decrease in HCN concentration above 350 °C, with no detectable emissions for the two highly loaded catalysts (Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) (Fig. 1d) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.8) (Fig. 1f)). Theoretically, this behaviour could stem from either a lower concentration of HCN emissions formed over the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.8) catalysts or their ability to convert the formed HCN. Ultimately, both possibilities probably originate in the different local structures of Cu species compared with that present in the catalysts with an Si/Al ratio of 7. Although the distribution of Al in the zeolite framework could not be confirmed since the preparation method for the commercial supports used in this study is unknown, the probability of finding adjacent Al atoms in the zeolite framework should increase with the decrease in Si/Al ratio, irrespective of the preparation method. Hence, two possible structures (that is, Z2Cu and ZCuOH) could be present in different percentages in the catalysts with an Si/Al ratio of 7 versus those with an Si/Al ratio of 14 (ref. 29). Nevertheless, the fingerprint of these species is more pronounced at higher temperatures due to NH3 desorption and decreased mobility of the Cu species22.

Considering the influence of the Si/Al ratio on HCN emissions at high temperatures, as well as the general decrease in the SCR activity at low temperatures, a better understanding of the evolution of Cu species under reaction conditions is necessary to clarify their role during HCHO conversion and in minimizing HCN emissions. For this purpose, two representative catalysts with intermediate Cu loadings—Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3)—were investigated in detail.

Nature of active sites

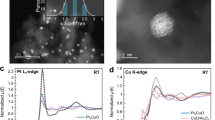

In a first step, the interaction of Cu ions with the zeolite framework was evaluated by XAS measurements at 150 °C after catalyst pre-treatment in 10% O2/He at 500 °C. This procedure leads to sample dehydration and migration of Cu to the ion exchange positions40,45. The FT-EXAFS data reported in Supplementary Fig. 5 uncovered the presence of two well-defined coordination shells at ∼1.8 and ∼2.6 Å for the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) sample, which were previously assigned to bonds with oxygen and bonds with Si/Al in the zeolite framework or with other Cu atoms, respectively22,40. Additionally, a small feature appeared around 3.4 Å, which was assigned previously by Pappas et al.41 to the Cu–Cu scattering path in multinuclear CuII species such as ZCuIIOCuIIZ. Such a behaviour during sample dehydration leading to the formation of dimeric species linked to opposite Al sites in the zeolite framework was also indicated by Fahami et al.22 based on electron paramagnetic resonance investigations of differently loaded Cu-SSZ-13 samples. Although this evolution of certain Cu species cannot be excluded, due to the rather short k range applied during data evaluation (2–12 Å−1) and the elevated temperature of the measurement, a clear assignment of the feature appearing at 3.4 Å would require further investigations. The profile of the first coordination shell is almost identical for Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3), however the second coordination sphere is substantially less pronounced.

To distinguish between overlapping contributions from different neighbouring atoms or scattering events, such as Si/Al and Cu in the second coordination sphere, wavelet transform analysis of the EXAFS spectra was additionally used (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Fig. 6)46,47,48,49,50. Despite equally high resolution in both k and R space being difficult to achieve via this data analysis approach47,51, the backscattering amplitude factor strongly depends on the atomic number. Thus, heavy atoms are typically observed at high wavenumbers, whereas light atoms contribute at low k values. For both Cu-SSZ-13 samples, a distinct first shell lobe at Δk = 1.5–9.0 Å−1 and ΔR = 1.00–1.75 Å (not corrected for phase shift) is visible that can be associated with the contribution of the oxygen atoms in the zeolite framework. In the second coordination sphere (R > 2 Å), multiple lobes are observed due to several contributions. Based on previous studies on similar systems,28,47,51,52 the first lobe appearing around Δk = 2.8–4.3 Å−1 and ΔR = 2.00–3.75 Å for the Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts can be assigned to the second oxygen shell, whereas the second lobe at Δk = 5.0–7.5 Å−1 and ΔR = 2.00–4.75 Å could be associated with backscattering of either Al or Si atoms of the framework. Even the third lobe, which is distinguished for Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) around Δk = 8–9 Å−1 and ΔR = 2.50–3.75 Å, can be assigned to Cu–Si and Cu–Al scattering paths according to DFT calculations of possible Cu structures after sample dehydration (Supplementary Table 4). Nevertheless, we cannot completely exclude the additional contribution of a Cu–Cu scattering path in this region caused by the formation of dimeric oxo/peroxo Cu species linked to the zeolite framework upon dehydration41. For both samples, another lobe was observed around Δk = 9–11 Å−1 and ΔR = 2–3 Å, which is usually an indicator of further Al, Si or Cu atoms. Overall, the WT-EXAFS features appearing in the second coordination shell were more intense for the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) catalyst, suggesting a stronger interaction between the Cu species and zeolite framework compared with that appearing for Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3), which is in line with the magnitude of the FT-EXAFS data. This is also consistent with the higher concentration of Z2Cu species that would be expected for this catalyst, whereas the formation of ZCuOH species is favoured for the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) sample53.

a,b, Experimental two-dimensional wavelet transform plots of EXAFS χ(k) spectra collected at the middle position of the catalyst bed at 150 °C after temperature-programmed oxidation up to 500 °C in 10% O2/He with a ramp rate of 5 °C min−1 for Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) (a) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) (b). c,d, XANES spectra collected during H2-TPR in 1,000 ppm H2/He with a ramp rate of 5 °C min−1 for Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) (c) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) (d). Inset, magnifications of the pre-edge regions between 8,970 and 8,980 eV.

To further support these findings, in situ DRIFTS measurements were conducted for the Cu-SSZ-13 samples after dehydration in 10% O2/Ar up to 350 °C, followed by NH3 adsorption at 100 °C. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8, a more pronounced negative band appeared around 3,656 cm−1 for the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) catalyst compared with the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) sample. Considering that this feature has been previously assigned to ZCuOH sites40 and should appear with negative intensity compared with the background upon NH3 adsorption, this aligns well with the higher concentration of these species in the SSZ-13 zeolite with an Si/Al ratio of 14.

For the same samples, temperature-programmed reduction (TPR) experiments were conducted under relatively mild reducing conditions in 1,000 ppm H2/He (Fig. 2c,d and Supplementary Fig. 7) or 350 ppm NH3/He after catalyst dehydration in 10% O2/He at 500 °C (Supplementary Fig. 9). For both experiments, X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra were continuously collected at the Cu K edge while heating the catalyst bed to 500 °C at a rate of 5 °C min−1. According to previous studies on Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts25,54,55,56, several characteristic features can be distinguished in the Cu K-edge XANES profile depending on the Cu oxidation state and coordination environment. For Cu2+ a pre-edge feature can be observed at 8,977.5 eV in the insets of Fig. 2c,d due to weak dipole-forbidden/quadrupole-allowed transitions (1s → 3d). This does not appear for Cu+ since this transition is not possible due to the different electronic configuration (4s13d10). Instead, the presence of Cu+ is indicated by the intense peak between 8,982 and 8,984 eV that is generated by a combination of 1s → 4p transition and asymmetric mixing with unoccupied ligand orbitals55. Although this transition is independent of the oxidation state of copper, its fingerprint is the most intense for a linear geometry involving the degeneration of both the 4px and 4py orbitals. Such a geometry is highly frequent for Cu+ species. An increase of the Cu coordination number causes the shift of this feature towards higher energies while decreasing its intensity. Additionally, a splitting of this feature can be observed since the double degeneration of 4px and 4py is lost by a transition from a linear geometry to a T-shaped one. Above 8,985 eV, the 1s → 4pz transition is expected, but due to possible overlap with the white line position, its contribution is only visible in the case of strong metal–ligand interactions.

At the start of the H2-TPR experiment, a shift of the Cu K-edge white line to 8,998 eV and the evolution of an edge feature at 8,987 eV could be observed for both samples (Fig. 2c,d). The latter feature was assigned to the 1s → 4px,y transition in Cu2+ and indicates the dehydration of the catalyst25. Upon further heating of the catalyst bed, the intensity of the white line feature at 8,998 eV continuously decreased during the reduction of both catalysts, and two small features at 8,989 and 8,983 eV evolved. At the same time, the pre-edge feature at 8,977.5 eV disappeared and an additional shoulder at 8,979 eV appeared. These increasing features were previously attributed to the 1s → 4px (8,979 eV), 1s → 4py (8,983 eV) and 1s → 4pz (8,990 eV) transitions in Cu+ species40,54. Therefore, a reduction of Cu2+ to Cu+ combined with a change in the local geometry of the copper sites is indicated. In line with previous literature data on similar samples, even at the highest measured temperature of 500 °C, no metallic copper could be detected due to the strongly stabilized local structures of Cu species inside the zeolite framework57. Although the overall trend during reduction of the two catalysts was similar, the extent of reducibility and the final state of Cu were different. Whereas for the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) catalyst at 210 °C, a 50% reduction to Cu+ was measured, for the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) sample this point was only reached at 320 °C (Supplementary Fig. 7). This variation in the reducibility of Cu sites for SSZ-13 catalysts with different Si:Al ratios has been reported previously in literature, and is often exploited to estimate the Z2Cu and ZCuOH fractions42,53. In general, it was observed that the reduction of Cu was promoted by an increase in the Si/Al ratio in the chabazite framework, which corresponds with the formation of ZCuOH as the predominant species. In line with these statements, the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) catalyst showed almost full reduction at 500 °C, with a Cu+ content of 93.5% according to linear combination fitting (Supplementary Fig. 7). In contrast, in the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) sample, only 85.5% of copper was present as Cu+ species at 500 °C.

Even more pronounced differences in the XANES profile were observed between the two Cu-SSZ-13 samples during the NH3-TPR experiment (Supplementary Fig. 9). In this case, the Cu2+ pre-edge feature typically observed at 8,977.5 eV almost completely disappeared as soon as the catalyst was exposed to the NH3-containing gas mixture (Supplementary Fig. 9). Although the characteristic feature of linearly coordinated Cu+(NH3)2 species was easily visible at ~8,982.5 eV on the Cu K edge for the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) sample, this fingerprint showed a notably lower intensity for the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) catalyst. Moreover, analogous to the behaviour noticed during H2-TPR, the structural evolution and final state of Cu at 500 °C were not the same in the two zeolite frameworks. This different behaviour could be caused by a stronger interaction of the Cu ions with the zeolite framework in the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) sample, leading to the formation of highly stable Z2Cu species. At the same time, ZCuOH sites are probably formed in Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3), which explains their higher reducibility53,58. These differences in local structure and reducibility are also supported by the redox response observed for Cu species during NH3 oxidation over the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) and Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 11). However, as mentioned previously, under reaction conditions, the solvation of Cu species by NH3 and H2O is expected to diminish these differences in the Cu state at low temperatures59, whereas the link to the zeolite framework becomes noticeable mostly above 350 °C25,26,44,58,60.

To elucidate the influence of HCHO on the structures of the different Cu species in Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) samples under reaction conditions, spatially resolved operando XAS measurements were conducted at the Cu K edge along the catalyst bed during the standard NH3-SCR reaction. The catalyst bed located in a capillary reactor was monitored at five different positions between the beginning and the end of the catalyst bed. To probe both temperature regimens, we selected two temperatures (one either side of 350 °C—the seagull inflection point): 300 °C, corresponding to <20% NO conversion; and 450 °C, corresponding >80% NO conversion. The NH3/H2O solvation extent of Cu species is already expected to decrease at 300 °C, leading to variation in the Cu structure26,44. However, it is likely that the presence of HCHO causes the formation of different Cu species with higher stability, which are responsible for the strong inhibition of the NH3-SCR process. Moreover, the highest HCN emissions were measured for both of the selected Cu-SSZ-13 samples at this temperature (∼50 ppm; Fig. 1), due to their very poor HCN conversion activity in this temperature range. Hence, 300 °C was considered a reasonable compromise to investigate the state of the active sites during NO, HCHO and HCN formation and conversion. Figure 3 depicts the XANES spectra collected at the Cu K edge during the NH3-SCR reaction at 300 and 450 °C for Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) samples in the presence or absence of formaldehyde. Under typical standard SCR conditions, a more reduced beginning of the catalyst bed was observed at 300 °C (Fig. 3a,b; black lines), as suggested by the intense edge feature appearing at 8,983 eV. This feature was previously associated with the formation of linear Cu+(NH3)2 species via solvation with NH3 (ref. 60), and is especially pronounced at low temperatures25. The intensity of this feature steadily decreased towards the end of the catalyst bed, pointing to the presence of more oxidized Cu species at these positions. This variation in the Cu oxidation state correlates with the consumption of NO/NH3 along the catalyst bed and the resulting decrease in available reducing agent22,61. This overall trend could be observed at both Si/Al ratios, but the intensity of the 8,983 eV feature was higher for the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) sample at all investigated catalyst bed positions. Therefore, a lower average oxidation state can be assumed under standard SCR reaction conditions for the catalyst containing ZCuOH species. This is probably due to their higher reducibility, as was already observed during the H2-TPR experiment (Fig. 2), combined with a lower re-oxidation rate. At the same time, during the solvation process26 a change in the local geometry towards a linear Cu–NH3 configuration is easier to achieve for the ZCuOH sites. When the temperature was increased to 450 °C (Fig. 3c,d; black lines), Cu species at the beginning of the catalyst bed remained in a reduced state, but to a lower extent compared with that observed at 300 °C, due to the higher reaction rate. Additionally, there was a strong decrease in the intensity of the 8,983 eV feature towards the end of the catalyst bed, accompanied by emerging shoulders at 8,986 and 8,992 eV. These indicated the presence of oxidized Cu2+ close to the end of the catalyst bed, probably due to the high or full conversion of NO and NH3 at the beginning of the catalyst bed61. Even though the trend was similar for both Si/Al ratios under the applied reaction conditions, in the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) catalyst, Cu species remained more oxidized at all of the investigated positions within the catalyst bed, in comparison with the corresponding state in the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) sample.

a–d, Spatially resolved XANES data collected at the Cu K edge for Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) (a and c) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) (b and d) catalysts under steady-state SCR conditions in the absence (black lines) and presence (red lines) of formaldehyde at 300 °C (a and b) and 450 °C (c and d). Position 1 (Pos 1) was towards the beginning of the catalyst bed in the quartz capillary microreactor and position 5 was towards the end of the catalyst bed. The gas composition was 350 ppm NO, 350 ppm NH3, 0–100 ppm HCHO, 0.5% H2O and 10% O2 in He.

Upon HCHO addition to the gas mixture at 300 °C (Fig. 3a,b; red lines), the catalyst bed remained in a more reduced state over its entire length, as indicated by the intense Cu K-edge feature at 8,983 eV that appeared at every single measured position. Additionally, a feature at 8,987 eV was visible in combination with the decrease in the white line intensity around 8,999 eV. Although incomplete conversion of the SCR mixture (Supplementary Fig. 10) could result in a more extended catalyst bed area containing reduced Cu+ species, this cannot explain the additional feature appearing at 8,987 eV. This feature has previously been attributed to the 1s → 4pz transition of Cu+ species with strong metal–ligand interaction54. Therefore, the adsorption of an unknown, strongly binding species can be assumed. Since this feature is only discernible if HCN emissions are detected (Supplementary Fig. 10), the formation of Cu–CN-like species could be predicted. After increasing the temperature to 450 °C, Cu species in the catalyst bed remained overall more reduced compared with the measurements conducted in the absence of HCHO. Intense features were recognized at 8,983 and 8,987 eV, but towards the end of the catalyst bed their intensity decreased due to the consumption of reducing agents at upstream positions.

When comparing the two investigated catalysts, a higher intensity of all edge features was noticed for the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) sample at this temperature, even though this catalyst demonstrated the lowest HCN emissions. Considering the rather complex gas mixture used during these tests, including the simultaneous presence of NO, NH3 and HCHO, together with reaction products and byproducts and intermediate species, a precise assignment of the observed spectral fingerprints to HCN formation or conversion is difficult. At the same time, the limited number of spatially resolved XANES spectra collected under steady-state conditions along the catalyst bed did not allow for multivariate curve resolution with alternating least squares fitting62 to be conducted in order to obtain further information on the variation in the Cu state due the change in reaction conditions. Hence, the catalyst structure was additionally investigated during the direct interaction with HCN under simplified or complex reaction atmospheres, including transient reaction conditions.

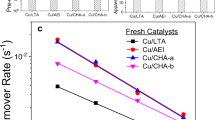

Effect of HCN on SCR activity

To clarify whether the decrease in activity at low temperatures occurs before or after HCN formation, SCR activity tests in the presence of HCN were conducted as a next step for the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) catalysts. As illustrated in Fig. 4a, both samples showed a strong diminishment in the SCR activity at temperatures below 350 °C and full recovery of NO conversion above 350 °C. The corresponding HCN conversions are reported in Supplementary Fig. 12.

a, Conversion of NOx (dashed lines) and NH3 (solid lines) in the presence of HCN for Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) (black lines) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) (red lines) during NH3-SCR of NOx. b, Spatially resolved operando XANES measurements at the Cu K edge for Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) (black lines) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) (red lines) during steady-state SCR conditions in the presence of HCN at 300 °C. Position 1 was towards the inlet of the capillary reactor and position 5 was towards the outlet. The gas composition was 350 ppm NO, 350 ppm NH3, 100 ppm HCN, 0.5% H2O and 10% O2 in He.

As had already been observed for the SCR measurements in the presence of formaldehyde (Fig. 1b,e), NOx conversion also in this case started at lower temperatures for Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) compared with Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3). Moreover, for both catalysts, the trend in conversion seemed to follow the corresponding activity profile observed during NH3-SCR in the presence of formaldehyde (Fig. 1b,e). Therefore, the decrease in the SCR activity at lower temperatures seemed to be caused by the formation of inactive Cu–CN species in the presence of HCN. At 300 °C, this process was confirmed by XANES measurements at the Cu K edge during SCR of NOx with NH3 in an HCN-containing gas feed (Fig. 4b). Under these conditions, a new edge feature was observed around 8,987 eV for both catalysts, and this was also noticed when HCHO was added to the standard SCR gas mixture. At the same time, a rather low HCN conversion was observed below 350 °C (Supplementary Fig. 12). Although some of the formed HCN via HCHO conversion might also be converted at low temperatures under NH3-SCR conditions, this reaction is not expected to occur at a high rate based on these results. In contrast, at higher temperatures, only Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) shows almost complete HCN conversion, whereas still only minor activity was measured for the catalyst containing predominantly Z2Cu species (Supplementary Fig. 12).

HCN interaction with Z2Cu and ZCuOH sites

To further evaluate the effect of HCN on the structure of Cu species, in situ XANES measurements were conducted at the Cu K edge in a model gas mixture containing only 100 ppm HCN and 10% O2/He (Fig. 5c) for both Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) catalysts. The resulting spectral profiles were compared with those obtained in 25 ppm HCHO and 10% O2/He (Fig. 5a). During the addition of formaldehyde at 300 °C, broad features were visible at 8,983 and 8,986 eV (Fig. 5a) and a shoulder was seen at 8,992 eV. The presence of these features and the slight decrease in the white line intensity can be assigned to a partial reduction of Cu2+ to Cu+. A higher intensity of both features and lower intensity of the edge maximum were observed for the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) sample compared with Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3), which once again indicated a more pronounced reduction of ZCuOH species that were present in this catalyst. When the catalyst was exposed to 100 ppm HCN and 10% O2/He, notably more prominent features were observed in the Cu K-edge XANES spectrum compared with those induced by the presence of HCHO. Additionally, the shoulders appearing on the edge step were slightly shifted to 8,982 and 8,986 eV (Fig. 5c). Moreover, in this case, their intensity was higher for the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) sample, with the exception of the white line region. Comparison of these measurements with the corresponding XANES profiles obtained during exposure to NH3/He or NH3/O2/He (Supplementary Figs 9 and 11, respectively) revealed an intermediate intensity and shift towards higher energy for the feature related to the 1s → 4py transition (8,982 eV in HCN/O2/He and 8,983 eV in NH3/He and NH3/O2/He). Although this trend could be explained by a slightly different degree of reduction to Cu+ in the presence of HCN/O2/He versus that occurring in the NH3/O2/He feed, this process is improbable due to comparable intensities and the position of the white line for the two experiments. Alternatively, in the presence of HCN, the Cu ions could adopt a different configuration compared with the expected linear geometry during NH3 solvation54,55,56. This was supported by the appearance of an additional feature at 8,986 eV, which could be assigned to the 1s → 4pz transition. Combined with the Cu K-edge white line at 9,006 eV, this feature, which also appears during the SCR of NO with NH3 in the presence of HCHO (Fig. 3) or HCN (Fig. 4), seems to be a characteristic of HCN bound to Cu+ sites.

a,c, In situ XANES measurements at the middle position of the catalyst bed under model gas conditions of 25 ppm HCHO and 10% O2 in He (a) and 100 ppm HCN and 10% O2 in He (c) for Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) (black lines) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) (red lines) at 300 °C. Corresponding FDMNES-calculated (calc.) XANES spectra are also depicted. b, XES spectra of Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) during steady-state SCR conditions in the presence (red line) and absence (black line) of formaldehyde at 300 °C. The gas composition was 350 ppm NO, 350 ppm NH3, 0–100 ppm HCHO, 0.5% H2O and 10% O2 in He. d, FDMNES-calculated XES spectra based on the the structures shown in a and c. e, Predicted structures of formate, cyanide and possible Cu–CN/NH3 species determined by DFT calculations (green, grey, red, yellow, cyan, dark blue and white represent Al, C, O, Si, Cu, N and H, respectively).

To confirm this assumption and further elucidate the structures of the measured reference states, DFT calculations of several predicted configurations were conducted. Since the adsorption of formaldehyde on Cu ions is expected to progress to formic acid63, the calculated structure during formaldehyde addition was assumed to be a formate species with a square planar geometry (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 4). A slight deviation of the planar structure is predicted with a torsion angle of 5.2° against the four oxygen ligands. Nevertheless, a rather symmetrical oxygen coordination is anticipated with an average Cu–O distance of 2.0 Å for the formate and framework oxygen atoms.

As illustrated in Supplementary Table 4, different structures representing possible Cu–CN species were calculated in the next step. Among the structures considered were: monomeric copper attached to the zeolite framework and interacting with H2O, NH3 or HCN; monomeric Cu solvated by both cyanide and NH3; and dimeric Cu species solvated by cyanide and/or NH3. Depending on the simulated structure, clear variations in the local geometry and bond distances were obtained. For instance, the predicted monomeric cyanide structure with copper bound to the zeolite framework showed a T-shaped geometry with C–Cu–O angles of 170.9° towards the trans-oxygen and 109.1° towards the cis-oxygen (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 4). A strong asymmetry in the Cu–O distances was observed for this structure. Although the distance of Cu–Ocis was calculated to be 2.01 Å, the presence of the cyanide ligand seemed to drive the Cu ion towards the framework, resulting in a shortened Cu–Otrans distance of 1.93 Å. This corresponds to a rather strong metal–ligand interaction considering the observed distance is shorter than that of the Cu–O bond in Z2Cu (1.95 Å) and ZCuOH (1.98 Å). At the same time, the Cu–C distance was calculated to be 1.84 Å for this structure. In contrast, the mobile dimeric cyanide species is predicted to have a linear geometry with a symmetric Cu–O bond with a distance of 1.73 Å (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 4). Compared with the monomeric species, a shorter Cu–C bond of 1.83 Å was calculated for the dimeric cyanide species. A linear geometry was also obtained for the solvated monomeric species with mixed ligands (NH3 and H2O), whereas a shorter distance was predicted for the Cu–C bond (1.82 Å), and a Cu–N bond distance of 1.94 Å is expected.

In addition to considering the desorption of NH3 and H2O as a function of temperature increase25, the finite difference method near-edge structure (FDMNES)64 code was used to simulate the XANES spectra based on the DFT-generated structures to identify the Cu configuration formed under reaction conditions. The simulated spectra of the formate species (Fig. 5a, blue line) predicted an edge feature at 8,988 eV and a shoulder at 8,992 eV. This is in agreement with the measurements of the Cu K edge in the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) catalyst (Fig. 5a, black line), which shows only a slight reduction. However, the simulated XANES profile does not align with the experimental data obtained for the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) sample (Fig. 5a, red line), where a higher degree of reduction is observed for the copper sites. Additionally, the predicted XANES profile overlaps with the common features of dehydrated Cu2+ species (Fig. 2); therefore, any assignment of formate formation needs to be further proved.

Among the calculated XANES spectra of the Cu–CN structures with and without NH3 co-adsorption, only a few were found to replicate the features of the experimental data, which are discussed below (Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Table 4). As shown in Fig. 5c, an intense feature at 8,984 eV and two shoulders at 8,988 and 8,991 eV appear in the theoretical XANES spectrum of the monomeric copper cyanide species still attached to the zeolite framework (ZCu+CN−). At the same time, the dimeric (NC–Cu)2O species is predicted to have edge features at 8,983 and 8,987 eV, with lower intensity compared with the monomeric species and a double-edge maximum with peaks at 8,993 and 8,998 eV. The solvated Cu monomeric species ([Cu(NH3)]+CN−) is expected to exhibit edge features at 8,986 eV, with comparable intensity to that of the HCN solvated dimeric species and the edge maximum at 8,994 eV. By weighting the shape and intensity of the features on the Cu K edge and white line for the calculated XANES spectra against the experimental data, it is evident that a perfect match is not achieved with singular species for the two Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts. Although a higher resemblance is noticed between the edge profile of the operando XANES spectra and the calculated one of the (NC–Cu)2O dimeric species, the additional presence of [Cu(NH3)]+CN− monomeric species cannot be excluded based on the corresponding shape of the Cu K-edge white line. Hence, although H2O is expected to have a weaker interaction with Cu species at intermediate and high temperatures25,65, the simultaneous adsorption of HCN and NH3 leading to the solvation of Cu is anticipated, especially below 350 °C. In this regard, the adsorption of ammonia and water on dimeric (NC–Cu)2O was studied using DFT by computing the adsorption free energies as a function of temperature. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 15 and 16, adsorption of NH3 to (NC–Cu)2O was favourable at all of the investigated temperatures up to 450 K and was furthermore more likely than adsorption of water, despite the higher partial pressure of water.

To further understand the nature of copper cyanide species, valence-to-core X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) was used in the next step due to its sensitivity when probing metal–ligand interactions33. In the standard NH3-SCR gas mixture, two intense peaks were visible at 8,973 and 8,975 eV in the Kβ2,5 region, accompanied by a shoulder at 8,982 eV and a minor peak at 8,990 eV (Fig. 5b, black line) for the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) catalyst. Although the peaks at 8,975, 8,982 and 8,990 eV did not change in intensity after the addition of formaldehyde to the gas mixture, the peak at 8,973 eV decreased in intensity (Fig. 5b, red line). Since a detailed interpretation of these variations is demanding due to the contribution of both ligand and transition metal orbitals40,66,67, the predicted DFT structures were also used in this case for the calculation of the XES spectra based on the FDMNES code (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Table 5). The calculated valence-to-core XES spectrum shows a high-intensity peak at 8,972 eV and a peak of lower intensity at 8,978 eV for (NH3–Cu)2O, whereas two peaks with a similar intensity appear at 8,972 and 8,976 eV for (NH3–Cu)2O2 dimers, which are assumed to be the active species for NH3-SCR below 350 °C (refs. 23,24,27). For the monomeric cyanide species linked to the zeolite framework (Fig. 5d, red line), a doublet with lower intensity is predicted at 8,974 and 8,976 eV, combined with a shoulder at 8,977 eV, whereas the corresponding formate species (Fig. 5d, black line) is expected to show a peak at 8,977 eV. For the dimeric (NC–Cu)2O species (Fig. 5d, cyan line), peaks at 8,973, 8,974 and 8,978 eV, with the highest intensity for the feature at 8,978 eV, are anticipated. The solvation of Cu species by both HCN and NH3 would result in the appearance of a single peak at 8,974 eV if the two Cu atoms were connected via an O2 peroxo group, whereas two peaks at 8,974 and 8,978 eV are expected if a single oxygen atom is present between the two Cu atoms (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Table 5). Visual comparison of the experimental data and the calculated Kβ2,5 region for the Cu species linked to the zeolite framework shows a certain resemblance with the ZCuOH sites upon NH3 or HCN adsorption. Considering that at 300 °C the formation of mobile species is highly probable, among the calculated spectra for the dimeric solvated Cu species, those of (NH3–Cu)2O2 and (NC–Cu)2O exhibit greater similarity. Herein, the decrease in intensity of the feature at 8,971 eV in the experimental data after formaldehyde addition suggests the replacement of (NH3–Cu)2O2 dimers with cyanide-solvated species. To further elucidate the variations in the spectral features, the Kβ′′ satellite region was investigated. As shown in Supplementary Table 5, the Kβ′′ position slightly shifted towards higher or lower energy relative to that of the ZCuOH site (8,958.8 eV) depending on the type of ligand. This high sensitivity of the Kβ′′ position has often been reported in the literature, which allows to probe a direct bond with N, C or O (refs. 66,67,68). Furthermore, as shown by Delgado-Jaime et al.69, the position and intensity of the Kβ′′ satellite are strongly influenced by the nature of the C ligand. Upon HCN adsorption, the Kβ′′ feature is predicted to emerge at 8,958.1 eV. In contrast, NH3 adsorption on an ZCuOH site would result in a Kβ” peak centred at 8,959.8 eV. The formation of (NH3–Cu)2O2 and (NC–Cu)2O dimeric species is anticipated to lead to a decrease in the Kβ′′ intensity and a further shift up to 8,960.7 and 8,961 eV, respectively. Finally, the position of the Kβ′′ satellite is expected to change only slightly if the Cu species are solvated by both HCN and NH3 (∼8,961 eV) while the intensity is significantly enhanced.

In the experimental data, a broad peak split into two main signals was detected in the Kβ′′ region after formaldehyde addition to the SCR mixture. The peak around 8,958 eV is typically assigned to Cu–N interaction33,70. The second feature of slightly lower intensity at 8,956 eV is commonly associated with a Cu–O interaction60,71. Although clear assignment is difficult considering all of the possible interactions expected in the presence of HCHO, the overall broadening of the Kβ′′ region and double-peak profile suggest the bonding of Cu with several ligands. The formation of Cu dimeric species solvated by NH3 under SCR conditions would result in direct bonds with both N and O, nevertheless the additional interaction with HCN and the formation of monomeric or dimeric species also imply links to O, C or N atoms, with C and N possibly linked via CN, NC or NCO groups. Based on the trends indicated by the calculated valence-to-core XES spectra for the Kβ′′ region, a shift towards lower energy is expected if HCHO is added to the NH3–SCR gas mixture. However, its magnitude and intensity depend not only on the type of ligand but also the final Cu structure (monomeric or dimeric or has Cu at the ion exchange position). In the experimental data, the intensity of the feature at 8,958 eV slightly decreases after HCHO addition, confirming the diminishment of the Cu–N interaction due to copper cyanide formation. However, owing to the excess of NH3 compared with HCHO/HCN concentrations (more than five times higher), identification of the Cu–C interaction fingerprint in the Kβ′′ region is challenging. Moreover, although beam attenuators were used during our experiments, the possibility of beam damage cannot be excluded considering the high flux of photons that is necessary for such measurements, which further limits the outcome of these investigations to a qualitative assessment.

To further elucidate these observations, EXAFS spectroscopy data were collected in the absence and presence of HCN (Fig. 6) for Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) samples at 300 and 450 °C. At first, a gas mixture containing only NO and HCN was applied (Fig. 6a,b), followed by the complete SCR gas mixture (Fig. 6c,d). Both catalysts showed an intense first coordination shell associated with the oxygen of the zeolite framework. A second shell was visible in NO + O2 (Fig. 6a) that is commonly assigned to framework Si or Al. At both investigated temperatures, this feature was more intense for the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) catalyst, again showing the stronger interaction of Cu with the zeolite framework in this sample. When HCN was added to the gas mixture at 300 °C, the intensity of both coordination shells decreased. Although this change was observed for both catalysts, the decrease was more severe for Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3), to a point that the second coordination shell—and thus the interaction with the zeolite framework—vanished. Although the formation of NH3 during HCN oxidation over Cu zeolites has been reported72, the withdrawal of Cu from the ion exchange positions by NH3 can be excluded at this temperature since no conversion of HCN was detected and possible traces of NH3 are eliminated in the presence of NO. Therefore, the drop in intensity for the second coordination shell was probably caused by a direct interaction with HCN, further showing the possible formation of mobile Cu–CN monomers or dimers. The formation of solvated species at 300 °C and the different interplay of Cu with the two zeolite frameworks in the presence of HCN is supported by the corresponding two-dimensional plots of the WT-EXAFS data (Supplementary Table 6). At 450 °C, the presence of HCN still decreased the intensity of both coordination shells, but only slightly for the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) sample, whereas the FT-EXAFS spectra of the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) sample showed comparable changes to those observed at 300 °C (Fig. 6b). Combined with the lower degree of Cu–zeolite interaction, as indicated by the previous XANES measurements (Fig. 4), and the lack of HCN conversion over Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3), the observed FT-EXAFS profile suggests the absence of an interplay between HCN and Z2Cu sites at 450 °C. This different interaction of HCN with Z2Cu compared with ZCuOH sites is probably at the origin of their distinct activity and selectivity profiles.

a–d, Fourier-transform (FT) k3-weighted EXAFS data of Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) (black lines) and Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) (red lines) recorded at the Cu K edge (k range: 3–15 Å−1). The measurements were conducted at 300 °C (a and c) and 450 °C (b and d) at the middle of the catalyst bed. The gas composition was 350 ppm NO, 0–100 ppm HCN, 0.5% H2O and 10% O2 in He (a and b) or 350 ppm NO, 350 ppm NH3, 0–100 ppm HCN, 0.5% H2O and 10% O2 in He (c and d).

Upon applying the SCR gas mixture at 300 °C (Fig. 6c), the FT-EXAFS data illustrated a small intensity for the second coordination shell due to the formation of mobile Cu–NH3 dimers. Whereas for the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) catalyst this feature was hardly noticeable at 450 °C (Fig. 6d), for the Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) sample the second coordination shell was clearly visible, in line with the stronger interaction of Cu with the zeolite framework. When HCN was added to the SCR gas mixture, overall the intensity of the Cu–O and Cu–O–Al/Si shells decreased again for both catalysts, following the same behaviour that was observed in the absence of NH3 (Fig. 6a,b). Also in this case, the HCN interaction with Z2Cu species was limited at 450 °C for Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3), as illustrated by the minor diminishment of the Cu–O–Al/Si shell (Fig. 6d). Since the mobility of Cu ions is anticipated under SCR reaction conditions at 300 °C, the additional decrease in the first coordination shell that was observed for both catalysts (Fig. 6c) either indicates a higher degree of Cu solvation due to the presence of HCN or the formation of Cu–CN mobile species with a lower coordination number. Although deconvolution of the second coordination shell in WT-EXAFS analysis is known to help to elucidate the exact nature of Cu species28, this approach was used only to evaluate the structural evolution of Cu under various reaction conditions (Supplementary Table 6). The clear assignment of individual scattering paths (for example, Cu–Cu in dimers) was avoided in our study due to the high sensitivity of EXAFS data to thermal vibrations73. In contrast with the less affected XANES region, the high temperatures used for the operando experiments is expected to influence the intensity of EXAFS features. Furthermore, Cu–CN mobile species are anticipated to interact with further gas molecules (that is, NH3), which also leads to a less defined structure and makes the separation of the different contributions difficult.

Further details on the low-temperature behaviour of Cu-SSZ-13 in the presence of formaldehyde were gathered by in situ DRIFTS measurements (Fig. 7a) at several temperatures up to 350 °C during catalyst exposure to the SCR gas mixture with or without HCHO. As expected, NH3 adsorption was observed in the absence of HCHO, as indicated by the broad band between 2,050 and 2,250 cm−1. After formaldehyde addition, NH3 remained the dominant surface species, but a slight decrease in the intensity of the characteristic adsorption band was noticed at 50 °C. At 100 °C, a new band appeared around 2,168 cm−1. This frequency was previously assigned to Cu–CN species74. Its intensity increases with an increase in temperature to 150 °C, in line with higher HCN emissions. Additionally, a shoulder is visible at 2,148 cm−1 that can also be assigned to cyanide species, whereas the NH3 adsorption band almost completely vanishes at 200 °C. Although NH4+ (or H+) cations are necessary to compensate for the charge of the zeolite framework during the formation of Cu–CN monomeric or dimeric species, the appearance of corresponding infrared bands40 is probably masked by the excess NH3 used during in situ DRIFTS measurements compared with the HCN concentration.

a, In situ DRIFTS measurements for Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) during NH3-SCR in the absence (dashed lines) and presence (solid lines) of formaldehyde in a temperature range of 50–200 °C. The pre-treatment was 1 h in 10% O2/Ar at 350 °C. The gas composition was 300 ppm NO, 300 ppm NH3, 0–25 ppm HCHO and 10% O2 in Ar. b, Ex situ diffuse reflectance UV–Vis spectroscopy after the treatment of Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) catalyst in 25 ppm HCHO and 10% O2 (black line), 300 ppm NO, 300 ppm NH3 and 10% O2 (red line), 300 ppm NO, 300 ppm NH3, 25 ppm HCHO and 10% O2 (green line) or 300 ppm NH3 (blue line) and Ar balance. c,d, Two-dimensional in situ XANES maps collected at the beginning of the catalyst bed for the Cu K edge in Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) during transient HCN addition during NH3-SCR at 300 °C (c) and 450 °C (d). The gas composition was 350 ppm NO, 350 ppm NH3, 0–100 ppm HCN, 0.5% H2O and 10% O2 in He.

After the in situ DRIFTS experiments, the pre-treated Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) catalyst was investigated with ex situ diffuse reflectance UV–Vis spectroscopy (Fig. 7b). Analogous to the XAS and XES measurements, similar main features were observed in the absence and presence of HCHO in the obtained diffuse reflectance UV–Vis spectra. Under both SCR conditions, a band between 512 and 800 nm was visible, which is typically associated with the d → d transition band of Cu2+ (refs. 75,76). In the region commonly assigned to ligand-to-metal charge transfer, a dominant band was visible at 225 nm when NH3 was present in the gas mixture. Previously, this band was associated with copper solvated by NH3 within the zeolite framework. By also considering the band at 350 nm, the formation of a µ-η2:η2-peroxodiamino di-copper complex is plausible during SCR in the presence and absence of formaldehyde77,78. Although these spectral features had similar intensities under both reaction conditions, a slight blue shift of the band at 350 nm was noticeable due to the presence of formaldehyde, which could have been caused by changes in the structure of the µ-η2:η2-peroxodiamino di-copper complex27,28,77.

HCN conversion at ZCuOH sites

Even though high emissions and similar HCN inhibiting effects were recorded at low temperatures for both Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) and Cu-SSZ-13 (7/1.3) catalysts, the observed difference in HCN conversion above 350 °C aligns well with the distinct structural characteristics of the ZCuOH and Z2Cu sites. At lower temperatures, coordination of HCN to the Cu sites was shown during the steady-state experiments reported in Figs. 5c and 4b. To confirm this assumption for the entire temperature range, further operando XAS investigations were conducted during the transient HCN dosage in the standard SCR gas mixture at 300 and 450 °C. For these measurements, 100 ppm HCN were periodically (∼6 min intervals) added to a gas stream containing 350 ppm NO, 350 ppm NH3, 0.5% H2O and 10% O2 in He and XANES spectra were continuously collected at the beginning of the catalyst bed. As illustrated in Fig. 7c,d, changes in the Cu K-edge XANES profile were observed immediately after HCN admission to the gas mixture at both of the investigated temperatures. The variations were particularly observed for the features between 8,982 and 8,986 eV around the absorption edge, whereas the white line decreased around 9,002 eV at both temperatures. Especially at 300 °C, the extent of detectable changes in the XANES profile was more pronounced, indicating substantial adsorption of HCN at these lower temperatures.

Nonetheless, the reversibility of this interaction was clearly demonstrated during the transient operando XANES measurements at 450 °C for the Cu-SSZ-13 (14/1.3) sample. According to the linear combination fitting analysis (Supplementary Fig. 15), around 49% of Cu sites formed Cu–CN species after 6 min exposure to HCN at 300 °C, versus only 24% at 450 °C. Once HCN was removed from the gas mixture, the intensity of the feature 8,982 eV increased again and the one at 8,986 eV decreased, without complete catalyst regeneration at 300 °C. Although there was a constant decrease in the content of HCN-associated species, after 6 min in the SCR gas feed, 25% of Cu species were still present as Cu–CN species. In contrast, HCN absence in the gas stream at 450 °C resulted in complete catalyst regeneration. This reversible behaviour was reproduced in several consecutive cycles of HCN exposure.

All of these observations on the implications of HCHO presence in the standard SCR gas mixture for NOx conversion and HCN formation are illustrated in a simplified scheme in Fig. 8 as a function of the type of Cu species. In spite of the fact that solvated and mobile monomeric and dimeric Cu species are formed at low temperatures in Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts due to the interaction with NH3 and HCN, which occurs irrespective of the Si/Al ratio and Cu loading (denoted as CuCN species), a distinct interaction was identified above 350 °C for ZCuOH versus Z2Cu species. The stronger interaction of Cu when linked to two framework Al centres (Z2Cu) influences the catalyst behaviour, especially at high temperatures, by preventing the adsorption and conversion of HCN. In contrast, ZCuOH sites that are formed at high Cu loadings and high Si/Al ratios in the SSZ-13 zeolite are accessible to interact with HCN (denoted as ZCuCN in Fig. 8) and catalyse its conversion, in this way restoring the initial catalyst structure. Although further investigations and kinetic studies would represent a great benefit for consolidating these mechanistic findings, the structure–activity–selectivity correlations derived in our study based on extensive in situ and operando characterizations and systematic activity tests provide the basis for understanding important aspects of the NH3–SCR reaction mechanism in the presence of HCHO, and facilitate the rational development of this class of catalysts for minimizing HCN emissions.

Conclusions

Systematic in situ and operando spectroscopic investigations combined with extensive catalytic tests and theoretical calculations allowed the identification of essential structural features in Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts for minimizing HCN emissions during SCR of NOx with NH3 in the presence of formaldehyde, which is a potential component in the exhaust of synthetic fuel or biomethane combustion engines. By screening the Si/Al ratio and Cu loading and thus varying the ratio of Z2Cu to ZCuOH species, valuable insights into the general SCR mechanism and complex behaviour of Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts were revealed. Whereas in the low-temperature range (<350 °C) a strong decrease in SCR activity and high HCN emissions were observed independent of the catalyst composition due to the equivalent Cu state after NH3/H2O solvation, at temperatures above 350 °C the NOx removal activity was less affected but HCN emissions were interconnected with the Si/Al ratio in the zeolite framework, as well as the nature of the Cu species.

Although the formation of HCN from HCHO and NH3 appears to be dominant over the entire temperature range of the SCR reaction, the subsequent interaction of HCN with copper sites seems to be site selective. Using complementary spectroscopic techniques supported by DFT calculations, it was possible to trace the pronounced decrease in SCR activity at low temperatures and observed HCN emissions to the formation of stable mobile cyanide species, which block the catalyst active sites. At higher temperatures, such mobile and/or zeolite-linked species are generated mainly via the reaction of HCN with ZCuOH sites, whereas the strong interaction with the zeolite framework prevents Z2Cu sites from converting HCN. Finally, the formed Cu cyanide species are converted at high temperatures, probably via NH3 formation, thus restoring the initial catalyst structure and circumventing HCN emissions.

Therefore, by adjusting the SSZ-13 zeolite composition and Cu loading, structural properties and the ability of Cu ions to convert HCN can be regulated. In this regard, the increase in the number of ZCuOH sites is expected to help minimize HCN emissions above 350 °C. Although further investigation of the detailed reaction mechanism for the formation of HCN from HCHO and NH3 and the subsequent conversion of HCN at ZCuOH sites is required, the outcome of this study offers guidance for the further development of Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts to minimize highly toxic HCN emissions and reduce the overall impact of HCHO from the exhausts of synthetic fuel and bio-fuel combustion engines.

Methods

Catalyst preparation

Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts with varying Si/Al ratios and different Cu loadings were prepared by ion exchange. Commercial NH4-SSZ-13 zeolites (Clariant) were stirred with an aqueous solution of Cu(CH3COO)2 at room temperature for 5 d, following a similar procedure to those described in previous studies61,76. The concentration of Cu(CH3COO)2 varied depending on the desired Cu loading (Supplementary Table 2). Subsequently, the samples were washed with deionized water and dried at 70 °C in static air. The resulting sample was calcined in static air at 550 °C for 4 h.

Catalyst activity tests

The SCR activities were evaluated using 7 mg granulated (100–200 µm) catalyst powder in a quartz capillary microreactor (inner diameter = 1.48 mm; outer diameter = 1.50 mm) heated using a hot air gas blower (XDS Oxford). To avoid bypass of the gas stream, the catalyst bed was fixed between two quartz wool plugs. Gases were dosed using mass flow controllers (Bronkhorst). The gas concentration in the product flow was monitored online after dilution with N2 to a flow of 300 ml min−1 using an FTIR spectrometer (MultiGas 2030 FTIR Continuous Gas Analyzer; MKS Instruments). To dose water and formaldehyde, either demineralized water or an aqueous solution of paraformaldehyde (16% solution, EM grade; Electron Microscopy Sciences) was used in a gas saturator. All gas tubes were heated to a temperature of 180 °C to prevent condensation before and after the catalyst bed.

Before each series of experiments, the fresh catalysts were conditioned for 1 h at 550 °C in a standard SCR gas mixture (350 ppm NO, 350 ppm NH3, 0.5% H2O, 10% O2 and He balance). Conditioning and the following activity tests were conducted under a total flow of ~100 ml min−1. The catalysts were tested at steady state in a stepwise manner between 550 and 150 °C, with 50 °C steps. All gas mixtures were dosed first without HCHO and afterwards in the presence of 80 ppm HCHO.

The conversion X of the different compounds was calculated using the following formula:

In this equation, cin stands for the inlet concentration, which was measured by bypassing the reactor. The concentration cout was measured at the outlet of the reactor.

Normalized reaction rates were obtained in a similar manner to those from previous studies based on a first-order kinetic equation on a per-mole-of-Cu basis79,80.

Ex situ characterization

Elemental compositions were identified by X-ray fluorescence analysis at the Institute for Applied Materials at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

Powder X-ray diffraction patters were collected for the as-prepared catalyst powders using a D8 ADVANCE X-ray diffractometer from Bruker with Cu Kα radiation. The scans were recorded a 2θ range of 8–60° with steps of 0.033°.

A BELSORP-mini II instrument (Bel Japan) was used to determine the surface area and pore volume of the catalysts. Before the analysis, approximately 80 mg of the sample was degassed at 300 °C under vacuum for 2 h. Afterwards, N2 adsorption and desorption isotherms were measured and evaluated using BELSORP data analysis software and the Brunauer–Emmet–Teller isotherm method81.

In situ and operando characterization

According to the selected spectroscopic method, but also due to the high number of samples and experimental conditions, several measurement campaigns were conducted at the SOLEIL (France), European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF; France) and PETRA III (Germany) synchrotrons to complete this study. In all cases, the same in situ and operando setup was used comprising a quartz capillary microreactor (inner diameter = 1.48 mm; outer diameter = 1.50 mm)82, a heating system (hot air gas blower), a gas dosage unit and gas analysers. To mimic a laboratory plug-flow reactor, the catalyst sample was used as granulated powder (100–200 µm) and fixed between two quartz wool plugs, which prevented bypass of the gas stream. For selected temperatures, five positions along the catalyst bed had been screened (the beginning, middle and end of a catalyst bed of 5 mm and two additional positions inbetween). In general, for reaction conditions under which minimal gradients along the catalyst bed were expected, the Cu state was probed at the middle position (position 3; for example, low conversion or during H2-TPR or NH3-TPR), whereas XES measurements were performed at the beginning of the catalyst bed (position 1). Gases were dosed using mass flow controllers (Bronkhorst). The gas concentration in the product flow was monitored online using an FTIR spectrometer (MultiGas 2030 FTIR Continuous Gas Analyzer; MKS Instruments). To dose water and formaldehyde, either demineralized water or an aqueous solution of paraformaldehyde (16% solution, EM grade; Electron Microscopy Sciences) was used in a gas saturator. All gas tubes were heated to a temperature of 180 °C to prevent condensation before and after the catalyst.

Conventional XAS in fluorescence mode was performed at the SAMBA beamline at the SOLEIL synchrotron. The incident energy (Cu K edge) of the X-ray beam was pitched by an Si(220) crystal with an energy resolution of 6.0 × 10−5. A 35-pixel HPGe fluorescence detector (Canberra) was used to detect and select the emitted radiation of the sample. The beam size was 0.3 mm in both vertical and horizontal dimensions. Scans were performed in step scanning mode. For transient measurements, X-ray absorption near-edge spectra were collected from 8,800–10,186 eV, resulting in a time resolution of 11 min per scan. These measurements included the H2- and NH3-TPR experiments displayed in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 9.

Further operando XAS measurements were performed at the ROCK beamline83,84 of the SOLEIL synchrotron. For these experiments, the quick-EXAFS85,86 acquisition mode was used with a time resolution of 2 Hz. Energies were selected using an Si(111) crystal monochromator. Under transient reaction conditions, the beginning of the catalyst bed was monitored with a beam size of ~0.432 nm × 0.223 nm (horizontal × vertical). For energy calibration, reference Cu metal foil was recorded together with each experimental spectrum. For initial data collection and merging, a graphical user interface developed at SOLEIL was used83,84. Further data evaluation was performed using Athena data analysis software87. The EXAFS spectra χ(k) were extracted, background subtracted and subsequently analysed in the k-space range of 3–15 Å−1. These measurements included the spatially resolved SCR experiments in the presence of HCN shown in Fig. 4, the reference states used for the WT-EXAFS analysis reported in Supplementary Table 6, the reference states shown in Fig. 5 and the transient measurements in Fig. 7.

Additional spatially resolved Cu K-edge (8,979 eV) XAS data were acquired at beamline P64 at PETRA III for selected reaction conditions using the same in situ and operando setup as described above. A liquid-nitrogen-cooled Si(111) channel-cut quick-EXAFS monochromator was used for fast data acquisition, together with fast-responding gridded ion chambers88. The monochromator oscillated at 2 Hz (8,610–10,038 eV), resulting in two spectra per second. The X-ray absorption spectrum of a Cu foil was recorded simultaneously throughout the entire experiment for energy calibration. During the XAS measurements reported in this study, no detectable changes in the sample due to exposure to the X-ray beam were observed. The results of these measurements are reported in Fig. 3.

Valence-to-core XES

Valence-to-core XES experiments were conducted at the ID26 beamline of the ESRF89. The incident X-ray beam was provided by three mechanically independent undulators and the higher harmonics were suppressed using Si-coated mirrors operated in total reflection mode. An Si (111) double-crystal monochromator was used to select the beam energy and the beam was focused both horizontally and vertically using a pair of mirrors. Fluorescence X-rays were collected using an X-ray spectrometer equipped with two spherically bent Ge crystals utilizing the (800) reflection and the photons were counted using an avalanche photodiode. A Cu foil was used in transmission mode for monochromator energy calibration. Energy calibration of the spectrometer was achieved by fixing the spectrometer energy at 8,903 eV while scanning the monochromator energy to record the elastic peak. For the valence-to-core XES measurements, the spectrometer scanned the X-rays emitted by the sample and the incident energy was kept constant above the Cu K absorption edge at 9,100.0 eV. In a first step, the valence-to-core spectra were normalized based on the area of the Kβ1,3 emission lines. Then, the background of the Kβ1,3 emission line was approximated using four pseudo-Voigt functions90. Finally, the valence-to-core data were subtracted. The gas flow dosing unit and capillary microreactor were identical to those used for the conventional XAS measurements. The X-ray beam size was 0.2 mm × 1 mm. To avoid beam damage of the sample due to the high photon flux, beam attenuators were used during the in situ and operando experiments. Additionally, during data acquisition, the position of the beam was changed continuously in a triangular motion to minimize the photon flux on a singular point and therefore decrease the beam damage of the samples.

Wavelet transform EXAFS analysis

For the wavelet transform, k3-weighted EXAFS spectra were used. A Morlet wavelet mother function for the wavelet transform of all spectra within the k range of 1–15 Å−1 was employed50. Wavelet transform was carried out using the MorletE software developed by M. Wang91.

Linear combination analysis

The linear combination analysis was conducted for the in situ and operando XANES data using the Athena data analysis software87 in the −20 to 30 eV energy range around E0. For the evaluation of the data collected during the H2-TPR measurement, internal references were used. These include the as-prepared sample after temperature-programmed oxidation at 500 °C in 10% O2/He to represent Cu2+ and the Cu state at 600 °C in 1,000 ppm H2/He as the Cu+ reference. For the transient HCN dosage experiment, the initial state of Cu (after 20 min of NH3-SCR) and its final state (after 20 min of NH3-SCR + HCN) were used as internal references. During the linear combination analysis, the sum of all contributions was forced to be one and individual weights were set to between zero and one.

DFT calculations

Geometry optimizations were carried out with periodic DFT calculations using the VASP program package92,93 with the projector-augmented wave method94. The PBE functional95 with Grimmes dispersion correction (D3)96 was used. The convergence criteria were set to a maximum force of 0.001 eV Å−1 with an energy cutoff of 400 eV and k-point sampling only at the Г-point. As in earlier studies97, the structural model of Cu-SSZ-13 was considered a periodic unit cell containing 36 tetrahedral atoms, from which one Si is substituted with Al, thus giving an Si/Al ratio of 35. The charge is balanced by a Cu+ ion, leading to isolated Cu monomers. The cyanide and ammonia dimers were calculated in the gas phase using a simulation cell of 18 Å.

Ab initio calculations of XANES spectra

Cu K-edge XANES and XES simulations were performed using the FDMNES code (revision 11/2022)64. Self-consistent calculations were executed using the finite difference method, which provided superior agreement with the experimental data compared with the full multiple scattering approach and muffin-tin approximation also available in the FDMNES software98,99. The real Hedin–Lundqvist exchange correlation potential was employed without core hole approximation. Parameters for the ab initio XANES simulations were optimized to achieve the best agreement with the experimental data. Calculations were conducted for a cluster radius of 7 Å.

DRIFTS and UV–Vis

DRIFTS was performed using a VERTEX 70 FTIR spectrometer (Bruker) equipped with Praying Mantis diffuse reflection optics (Harrick) and a liquid-nitrogen-cooled mercury cadmium telluride detector. Granulated catalyst samples (50 mg; 100–200 µm sieve fraction) were placed inside a high-temperature in situ cell (Harrick) fitted with a CaF2 window. Gas flow rates of 100 ml min−1 were applied using mass flow controllers (Brooks Instrument). After 1 h of oxidative treatment in 10% O2 in argon at 350 °C, the catalyst was cooled to 50 °C and exposed to the reaction mixture (300 ppm NH3, 300 ppm NO, 0–25 ppm HCHO, 10% O2 and Ar balance) for 30 min. After spectra were collected, the temperature was increased stepwise by 50 °C and additional spectra were collected until 200 °C was reached. For the NH3 adsorptions experiments, the catalyst was exposed to 500 ppm NH3 in Ar after oxidative treatment for 30 min at 100 °C and flushed in Ar for 30 min. After the DRIFTS experiment, the catalyst was cooled to room temperature in the reaction mixture and the Praying Mantis diffuse reflection optics (Harrick) were placed in the UV–Vis spectrometer (Agilent). Spectra were collected between the wavelengths of 200 and 800 nm. Spectralon was used as a reference.

Electron microscopy

A diluted aqueous suspension of the sample nanoparticles was deposited on a commercial holey ultrathin amorphous carbon film (3 nm) mounted on a 400-μm mesh Cu grid (Plano 01824). High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy measurements in combination with EDXS were conducted using an FEI Osiris ChemiSTEM microscope at an electron energy of 200 keV (using a Super-X EDXS system with four silicon drift detectors; Bruker). Cu K-edge EDXS spectra obtained during the scanning of specific sample areas were used to determine the overall distribution of Cu species with ESPRIT software (version 1.9; Bruker).

27Al MAS NMR experiments were conducted on an AVANCE NEO instrument. The probe was a MAS VTN 400 WB, which allows the rotation of 4-mm MAS rotors up to 15 kHz. The detailed experimental parameters are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The 27Al chemical shift was referenced to an aqueous solution of Al(NO3)3·9H2O.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the article and its Supplementary Information or available from the authors upon request. Source data for this article are available at KITopen (https://doi.org/10.35097/rhrwhbtxdme4emux).

References

Deutz, S. et al. Cleaner production of cleaner fuels: wind-to-wheel—environmental assessment of CO2-based oxymethylene ether as a drop-in fuel. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 331–343 (2018).

Burre, J. et al. Comparing pathways for electricity-based production of dimethoxymethane as a sustainable fuel. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 3686–3699 (2021).

Härtl, M., Seidenspinner, P., Jacob, E. & Wachtmeister, G. Oxygenate screening on a heavy-duty diesel engine and emission characteristics of highly oxygenated oxymethylene ether fuel OME1. Fuel 153, 328–335 (2015).

Rümmele, F., Susdorf, A., Haider, S. M. S. & Szolak, R. Light-off investigation of oxymethylene ether (OME) considering the presence of the exhaust components heptane, carbon, and nitrogen monoxide. Emiss. Control. Sci. Technol. 7, 348–358 (2021).