Abstract

Brain and breathing activities are closely related. However, the exact neurophysiological mechanisms that couple the brain and breathing to stimuli in the external environment are not yet agreed upon. Our data support that synchronization and dynamic attunement are two key mechanisms that couple local brain activity and breathing to external periodic stimuli. First, we review the existing literature, which provides strong evidence for the synchronization of brain and breathing in terms of coherence, cross-frequency coupling and phase-based entrainment. Second, using EEG and breathing data, we show that both the lungs and localized brain activity at the Cz channel attune the temporal structure of their power spectra to the periodic structure of external auditory inputs. We highlight the role of dynamic attunement in playing a key role in coordinating the tripartite temporal alignment of localized brain activity, breathing and input dynamics across longer timescales like minutes. Overall, this perspective sheds light on potential mechanisms of brain-breathing coupling and its alignment to stimuli in the external environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oscillations in breathing are linked to oscillations in neural activity1,2,3,4,5,6, arousal7,8,9,10,11,12, and cognitive function13,14,15,16,17,18, although the exact mechanisms have not been agreed upon. Our perspective paper highlights two mechanisms in the coupling of the brain, breathing, and external inputs from the environmental context. First, reviewing recent literature, we show that synchronization is key in directly connecting brain and breathing activity across shorter timescales from milliseconds to seconds. This includes different facets of synchronization like coherence, cross-frequency coupling, and entrainment. Then, using breathing and EEG data recorded in a small sample of subjects (N = 21), we demonstrate a temporal alignment of EEG data at the Cz electrode and breathing to the speed and variability of external inputs across longer timescales like minutes. Specifically, the data show that the input temporal structure manifests in corresponding temporal changes in the power spectra of both brain and breathing leading to their increased synchronization at specifically the intertrial interval of the task.

We describe the phenomenon of specific power spectral adaptations as dynamic attunement which can be seen as a subset mechanism of the more general feature of temporospatial alignment19. Dynamic attunement, taken in the present context, describes the adaptation of the temporal structure of both neural and respiratory activities to the temporal structure of the input over longer periods of time like minutes. The tight link between the temporal structures of both brain activity at the Cz channel and breathing with one of the external inputs suggests that the dynamics themselves (i.e., the complex temporal properties of signals and inputs across shorter and longer timescales) may provide the direct connection between the brain, breathing, and the environment.

Results

Mechanism one—synchronization of brain and breathing

Emerging evidence suggests that breathing and brain activity may be synchronized with each other at relatively short timescales, for instance, at the level of the millisecond-to-second3,20,21. To underscore the robustness of these effects, we review evidence from the current literature in humans that aligns with data first discovered in animal models. Cross-species representation of these mechanisms is crucial as it implies the fundamental and intrinsic nature of the coupling between activity in the brain and lungs.

Oscillations in breathing activity are coupled to oscillations in neural activity within the same frequency range (see ref. 22 for a recent review). In 1942, Edgar Adrian was the first to show breathing-synchronous oscillations in the local field potential of the olfactory bulb in the hedgehog23. Further experiments have revealed that these oscillations are present in other species. For instance, coherence between breathing and neural time series was demonstrated by Ito et al., 2014. The authors mounted intracranial recording devices to the somatosensory whisker barrel cortices while simultaneously monitoring breathing. The authors reported that oscillations in the local field potential (LFP) within the delta band (1–4 Hz) were phase-locked to the breathing cycle24 (see ref. 25 for a review).

Research in this field has since made the jump to human models. For instance, Herrero et al.26 used intracranial recordings and cross-spectral analysis of resting-state breathing and brain data to demonstrate a high degree of brain-breathing coherence across a widespread network of cortical (i.e., prefrontal, parietal, cingulate) and limbic regions (i.e., amygdala, insula, hippocampus) in the slow cortical potential range (i.e., 0.1–1Hz). The authors indicated that the highest peak in the neuronal power spectrum in frequencies analyzed between 0-1 Hz occurred precisely at the breathing rate26. Collectively, these findings suggest that the lungs and the brain couple their activity across relatively short timescales (i.e., at the level of the second-to-millisecond) through the synchronization of their slow wave activities (see Fig. 1).

Given the direct coupling of breathing and brain activity in the same frequency range, a logical progression is to ask whether breathing’s slow frequency activity is also related to the activity of the brain in faster frequency ranges. In the context of breathing, it has been demonstrated that different breathing speeds (slow or fast) yield vastly different mental effects. For instance, periods of slow breathing have been demonstrated to promote feelings of general wellbeing27,28,29 while periods of faster breathing tend to increase feelings of anxiety29,30,31,32,33. The coupling of breathing speeds to a wide range of mental effects suggests that characteristics of the breathing waveform may be directly coupled to a multitude of frequencies in the brain34,35,36,37.

To examine the relationships between two oscillators at different speeds, researchers analyze how the phase of the slower oscillator relates to the phase, frequency, or amplitude of faster ones38,39,40. Ito et al.24 provided evidence using mice for cross-frequency coupling between breathing and brain time series. The authors demonstrated that the amplitude of local field potentials in the gamma frequency band (30 + Hz) changes in tandem with the breathing phase with bursts of activity occurring during the early part of breathing exhalation. Using similar cross-frequency models, Tort et al., 2021 showed that breathing rate strongly correlates with the neural peak frequency and amplitude of gamma oscillations (30+ Hz). The phase locking of breathing to higher-order frequency ranges in the brain has also been shown in work by Cavelli et al., 2018 who demonstrated in cats that the beginning of exhalation was associated with bursts of gamma activity within a widespread network of regions (i.e., olfactory bulb, prefrontal cortex, and parietal cortex; see ref. 41 and see Fig. 1).

Cross-frequency coupling between breathing and brain activity has been replicated in humans. For instance, Herrero et al.26 reported bursts of neural gamma activity in the hippocampus tended to occur during the early part of the breathing exhalation. Cross-frequency coupling between breathing and neuronal time series extends beyond the gamma band. For example, Kluger and Gross1 used magnetoencephalography (MEG) resting state brain data from human participants while breathing was simultaneously recorded—their goal was to investigate whether breathing in the frequency range of 0.1–0.3 Hz is related to the amplitudes of neuronal activity in the 2–150 Hz frequency range. Kluger and Gross’s results indicate the relationship between breathing and neural oscillations is significant across all commonly measured neural frequency ranges (i.e., delta, alpha, beta, and gamma) and is widely distributed across the brain. Collectively, these findings indicate that the brain and breathing coordinate their activities at relatively short timescales using synchronization as indexed by coherence and cross-frequency coupling.

Mechanism two—the dynamic attunement of brain and breathing to external input streams in a small dataset

The relationship between breathing and brain signals interacts across all frequencies (0–30+ Hz; see section 2.0). This leads us to wonder if external factors including their specific frequencies can influence the patterns of brain-breathing coupling for instance previously demonstrated with auditory42,43 and visual stimuli44,45. The influence of external factors on bodily rhythms has been described as ‘alignment’ which, roughly, refers to how the brain’s neural activity or the lungs’ respiratory activity adapts their temporal structure to one of the external input streams like their power spectra, speed and variability19.

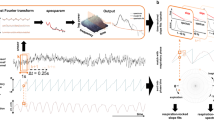

Alignment between systems and stimuli operates on multiple timescales, from shorter to longer ones19. Presupposing a very short timescale, a single external event can lead to a synchronized change in the wavelength and phase angle of an oscillating system at the moment the event occurs. However, without repeated input, the system will return to its intrinsic oscillatory activity, a process known as “resetting”45. Resetting has been observed in the brain and breathing in response to a variety of stimuli, including sensory, cognitive, and somatic stimuli44,45,46 (for a recent review see ref. 47). The alignment to a sequence of rhythmic stimuli (i.e., at a slightly longer timescale) is described as entrainment. Entrainment is described as when neural activity synchronizes its wavelength and phase with the timing of external stimuli45 (see Fig. 2). Entrainment, therefore, may indicate that dynamical features of the input itself may play a key role in shaping the activity within bodily oscillators such as the lungs or brain19,48,49,50. In essence, by examining the dynamic changes between bodily signal temporal characteristics (i.e., in the power spectra) and the corresponding attributes of the inputs like their respective frequency ranges, we can gain insight into the system’s overall adaptability and flexibility toward the inputs’ dynamics.

Entrainment results in stable wavelength, phase, and amplitude synchronization through a series of rhythmic phase resets. As entrainment is measured across a sequence of multiple external inputs, entrainment links breathing and brain activity to external inputs on a longer timescale than a phase reset.

The breathing rhythm has the remarkable capacity to adapt to different environmental contexts over shorter and longer timescales. For example, during the physical act of running fast, breathing also becomes fast51. Coupling between breathing and rhythmic inputs has also been shown in more complex situations, for instance when listening to music, dancing, or playing an instrument42,52,53. Here the coupling occurs over longer timescales lasting several minutes if not longer. The observed alignment of the breathing waveform and various internal and external rhythms raises the question of the neural mechanisms that enable the alignment of the lungs and brain to the environmental context over longer timescales. To distinguish such alignment on a longer timescale from the ones operating on shorter timescales (i.e., synchronization), we coin the term ‘dynamic attunement.’

Together, the remarkable adaptability and flexibility of both brain and breathing to their respective environmental context seem to operate over different timescales. These may include shorter ones as in phase reset in response to single stimuli, intermediate ones like in entrainment of the phase in response to multiple repeated stimuli, and longer timescales operating across several minutes if not hours (see ref. 54 in fMRI). Our focus here is on the last one, the longer timescales, namely dynamic attunement. The main question is how both the brain and lungs adapt the temporal structure of their activities to that of the inputs over longer periods. We now present breathing and EEG data supporting exactly this coupling of the brain, breathing, and inputs over a longer timescale, that is, dynamic attunement.

Twenty-one participants (N = 21) underwent 5 min of resting state and a go/no-go task where they were asked to respond to auditory inputs by pressing a key (see supplemental material for full details about the methods). Breathing data acquired using a pneumatic belt at the level of the diaphragm, and EEG activity at the Cz channel, due to its relevance for auditory processing55, were compared during rest and task states to quantify local brain-breathing coupling and its dynamic attunement to external stimuli. As indicated above, dynamic attunement refers to the adaptation of the temporal structures of both neural and respiratory activities to one of the inputs themselves over longer periods like multiple minutes entailing alignment over a longer timescale (as distinguished from the shorter timescales of entrainment and even shorter of a “reset”).

Using EEG data from the Cz electrode and corresponding breathing data, we explore how localized neural activity may align with breathing in response to rhythmic stimuli. Our data showed that both breathing and neural signals were dynamically attuned to the temporal structure of the external stimuli by both showing power spectra peaks in exactly that frequency range in which the external stimuli were presented. Accordingly, the findings support localized brain-breathing attunement to the longer-term temporal structure of the external stimuli as evidenced by specific changes in their power spectrum (PSD). This is supported by increases in the amount of coherence between breathing and EEG time series at the Cz electrode during the task relative to the resting state.

To quantify the effect of the task on breathing at the group level, we compared traditional breathing signal metrics such as breathing rate (breaths per minute; bpm), variability (standard deviation of the breath-to-breath intervals in milliseconds; SDBBI) and phase lengths (inspiration and expiration in seconds; s) between rest and task conditions. Significant changes in these signal characteristics would indicate adaptations of the breathing rhythm to the external input.

There was a significant increase in breaths per minute during the task (M = 20.28, SD = 3.55) as compared to the resting state with a large effect size. (M = 14.34, SD = 3.91; (z = 3.841, p = <0.001, matched rank biserial correlation = 0.957). Consequently, significant reductions in inspiration phase lengths were also observed during the task (M = 1.14, SD = 0.27) as compared to the resting state with a large effect size (M = 1.83, SD = 0.74, z = −3.841, p < 0.001, matched rank biserial correlation = −0.957). In a similar fashion, expiration phase lengths significantly decreased during the task (M = 1.73, SD = 0.31) as compared to resting conditions with a large effect size (M = 2.59, SD = 0.85, z = −3.702, p < 0.001, matched rank biserial correlation = −0.922); see Fig. 3).

Results indicate an overall faster (A) and less variable (B) breathing rhythm in the task relative to the resting state. In (C, D), the black dotted line indicates the exact intertrial interval of the task condition (1.3 seconds). Inspiration (C) and expiration times (D) tended to align themselves with these timings. Statistical measures above bar plots indicate results from F-tests. Results indicate significant decreases in the group variance of the SDBBI, inspiration, and expiration phase lengths during the task compared to resting conditions. A lower amount of intersubject variability during task states indicates that the breathing rhythm shapes itself to match the temporal structure of the external input. SDBBI = standard deviation of the breath-to-breath intervals. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

Given the correspondence in the temporal structure of breathing with that of the external input streams, we next investigated the effects of the task on breathing variability. If the breathing is indeed modulated by the durations of the external tones’ intertrial intervals, one would expect a decrease in breathing variability during task states. To quantify the effect of the task on breathing variability, we compared the average variability of the breath-to-breath intervals between rest and task conditions. Results indicated a significant reduction in the standard deviation of the breath-to-breath intervals during the task (M = 551.35, SD = 302.44) as compared to the resting state (M = 1429.78, SD = 781.27); z = −3.597, p < 0.001, matched rank biserial correlation = -0.896; see Fig. 3). Collectively, an increase in breathing speed and a simultaneous reduction in its variability indicates a temporally organizational effect of the task’s periodic structure on the breathing rhythm.

It is worth noting that inspiration and expiration phase lengths approached the intertrial interval of the task (1.3 s; see Fig. 3and Fig. 4). To illustrate the alignment of inspiration and expiration phase lengths to the intertrial interval of the task, we have included a visualization of the changes in the distribution of inspiration and expiration times across participants for each condition. Results indicate that participants’ inspiration and expiration phases approach 1.3 seconds in length during the task state (see Fig. 4).

Panels (A) and (B) represent the rest condition and panels (C) and (D) represent task conditions across participants (N = 21). Black dotted lines represent the intertrial interval of 1.3 s (0.769 Hz). Results indicate that participants’ inspiration and expiration times group themselves around the intertrial interval of the task (1.3 s). Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

In addition, F-tests revealed significant decreases in intersubject variability in the SDBBI (F(20,21) = 6.67, p < 0.001), inspiration (F(20,21) = 7.43, p < 0.001), and expiration times (F(20,21) = 7.46, p < 0.001) were observed in the task as compared to the rest conditions (see Figs. 3, 4). A decrease in the overall distance between subjects during the task compared to rest conditions further supports the temporal alignment of breathing to the external input.

We next raised the question of direct temporal correspondence of the breathing rhythm during the task state by investigating whether the intertrial interval of the task is directly reflected in an analogous temporal structure in the breathing pattern, e.g., in its power spectrum. For that, we recalculated the 1.3 s intertrial intervals as a frequency amounting to 0.769 Hz. To quantify the adaptation of specific temporal characteristics, we compared the size of the power peak at exactly the stimulus presentation frequency (1.3 s =0.769 Hz) in the breathing power spectrum between rest and task conditions. Results indicated a significant increase in the power peak at 0.769 Hz during the task (M = 0.029, SD = 0.077) as compared to the resting state (M = 0.002, SD = 0.002; z = 3.389, p < 0.001, matched rank biserial correlation = 0.844). This large effect size indicates a substantial difference between the two conditions.

Together, reductions in breathing variability and increases in the breathing power spectrum at exactly the stimulus presentation’s frequency indicate an overall dynamic attunement of the breathing’s temporal structure to the temporal structure of the external stimuli (i.e., input dynamics).

Given the tight link between breathing and brain activity, one may expect these systems to adapt similarly in their responses to external stimuli. To quantify if the brain adopts specific temporal characteristics of the task, we compared the size of the power peak at exactly the stimulus presentation frequency (1.3 seconds/0.769 Hz) in the neuronal power spectrum at the Cz channel between rest and task conditions.

Results indicated a significant increase in the power peak during the task (see Fig. 5; M = 0.480, SD = 0.367) as compared to the resting state with a large effect size (M = 0.016, SD = 0.031; z = 4.015, p < 0.001, matched rank biserial correlation = 1.00). To investigate this phenomenon further, we computed several additional analyses. First, we checked if the total power between rest and task changed. Indeed, the task state increased the total power for breathing with a large effect size (z = -2.242, p = 0.024, matched rank biserial correlation = 0.558) and brain (z = −3.458, p < 0.001, matched rank biserial correlation = 0.861) significantly. In this case, is the power peak observed during the task of relevance or could it stem simply from a general increase in power? To answer this question, we computed the ratio between the peak and the total power. Again, we can observe a clear increase in the ratio from rest to tasks in breathing (z = −2.597, p < 0.001, matched rank biserial correlation = −0.896) and brain with large effect sizes (z = −4.015, p < 0.001, matched rank biserial correlation = 1).

A Power spectrum of respiration and EEG signals averaged across participants (N = 21). For the breathing, we observe an overall shift from slower to faster frequencies in task versus resting state conditions. A zoom-in to the light blue shaded area for each subject can be found in the supplemental material. B In both breathing and brain, a larger peak is found at the rate of stimulus presentation (0.769 Hz, exact frequency indicated by red dotted line) during the task indicating the presence of task-dependent entrainment (i.e., task periodicity). C Total PSD and peak to total PSD ratio for breathing and brain. PSD = power spectral density. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

To make sure that the power increase observed during the task state is not due to increased motor activity, motor artifacts in all EEG recordings were removed via independent component analysis prior to analyses (see supplemental section 2.1.4 for details on data acquisition and preprocessing). Then, we plotted the response times for each subject over the total duration of the Go-NoGo task. We observed a high inter- and intra-subject variability in response times which do not add up to one specific frequency (see supplemental figure S1 for detailed results). These results suggest that the power peak increase at 0.769 Hz observed during the task in both the brain and breathing is likely to be induced by the dynamic attunement of the Cz channel and breathing to the temporal structure of the task rather than being related to some unspecific factor.

Finally, we investigated if the difference in the peak between rest and task is solely related to an increase in the mean or also via an increased intersubject variability. The F-test to compare two variances is significant for breathing (F(20,21) = 1001.5, p < .001) and EEG (F(20,21) = 146.5, p < 0.001), showing a higher intersubject variance of the peak during the task than rest.

We observe a statistically significant increase in the power spectra of both neural and respiratory activity at exactly the stimulus presentation frequency of the task. As both the Cz channel and breathing show this periodicity power peak at 0.769 Hz, we hypothesize that a higher degree of synchrony might exist between the Cz channel and breathing in the task than in the rest. To test for this, we computed the coherence between breathing and the Cz channel. A higher degree of coherence would indicate a higher degree of synchronization. Indeed, in Fig. 6, we observe a higher coherence at 0.769 Hz in the task (M = 0.256, SD = 0.150); than in rest (M = 0.098, SD = 0.097) with a large effect size (z = 3.08, p = 0.001, matched rank biserial correlation = 0.766).

Synchronization of brain and local breathing to the external temporal stimulus pattern (N = 21). A Increases in brain-breathing coupling during task conditions are indicated by the increase in coherence at precisely the intertrial interval of the task (i.e., 0.769 Hz). B Synchronization of the breathing activity with faster frequencies in the brain. Increases in brain-breathing coupling during task conditions are further supported by increases in the modulation index. Higher degrees of coherence and modulation indices between breathing and the Cz channel during task conditions suggest that the external task dynamics impact the brain-breathing coupling relationship. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

Finally, we calculated phase-amplitude coupling via the modulation index between breathing and the Cz channel using a previously validated approach56,57. The breathing activity was filtered between 0.5–1 Hz, which is exactly the range including the task’s frequency. The neural activity was filtered between 1–4.5 Hz (a higher frequency was not possible due to the low sampling rate of the breathing data—see Methods). A higher modulation index was found in the task (M = 0.458, SD = 0.253) than in rest (M = 0.318, SD = 0.200) with a large effect size (t (20) = 2.27, p = 0.034, d = 0.495; z = 2.033, p = 0.042, matched rank biserial correlation = 0.506) which suggests a higher degree of phase amplitude coupling between breathing and the brain during the task compared to the rest. Scaled values for the modulation index are presented in Fig. 6b and raw values can be found in the supplemental information (see supplemental information for a link to the Figshare repository).

Together, our analysis shows evidence of mutually shared information on breathing and localized brain activity patterns including their modulation by the external task periodicity. Hence, it may be the case that neural and respiratory systems adapt the dynamics of their activity in similar ways to the dynamics of inputs in their environment. This suggests that dynamics may provide the direct connection between the brain, breathing and environment over longer timescales, so-called “dynamic attunement”.

Discussion

Our main aim of this work was to assess the mechanisms that couple breathing and brain activity to the external environment over shorter and longer timescales. In addition, we sought to investigate whether their activities are coordinated with the input dynamics of external stimuli. Using existing literature in combination with our data set, our investigations have revealed two potential mechanisms (i.e., synchronization and dynamic attunement) in the coordination of brain activity at the Cz channel and breathing with the environment across shorter and longer timescales.

First, reviewing the literature, we reveal that the lungs and brain exhibit high degrees of coherence in the 0–1 Hz frequency band (see refs. 17,22 for recent reviews). In addition, breathing (0.1–0.3 Hz) shows a high degree of phase-amplitude coupling with faster frequencies in the brain for instance in the gamma band (see refs. 25,39 for reviews). We next asked the question of whether external factors can influence the patterns of brain-breathing coupling for instance as seen with music42. Our review of the data shows that the breathing and brain rhythms adapt their activities to the temporal structure of the external input. This can occur over shorter timescales as in phase reset in response to single stimuli as well as over slightly longer timescales with repeated external stimuli for instance as seen in the case of entrainment45. Together, these findings support that the brain and breathing may couple their activity together across shorter timescales using various facets of synchronization.

Our first mechanism, namely synchronization, facilitates alignment of the brain and breathing over shorter timescales at the level of the millisecond to a few seconds25,26,34,39,41,58. This, as we would say, reflects the alignment of the brain and breathing at a relatively short timescale, that is, the time point of their mutual synchronization with external stimuli. As described in the previous paragraph, with repeated input the data show that synchronization of brain and breathing can also occur across different timescales for instance seen in the case of entrainment45. The coordination of brain and breathing within and across multiple timescales suggests a key role of synchronization in the temporal alignment of brain and breathing over shorter timescales (i.e., milliseconds to several seconds). This suggests that their rhythmic activity does not occur in isolation but, rather, may be intrinsically connected.

We have so far focused on brain-breathing-environmental coupling at shorter timescales like milliseconds to seconds while leaving open the question of how the brain, breathing, and environmental coordination extend over longer durations like minutes or longer54. Our data show that participants’ physiological rhythms adopt specific temporal characteristics after several minutes of task engagement. Notably, spectral analysis of breathing and brain activity at the Cz channel demonstrates a significant increase in power peak precisely aligned with the intertrial interval of the task (1.3 s/0.769 Hz; see Fig. 5 and Supplemental Fig. S2 for individual subject results). The existence of a trilateral relationship in the temporal structures of localized brain activity, breathing, and the external inputs is further supported by the observed higher amounts of coherence between the Cz channel and breathing at 0.769 Hz during the task as compared to the resting state (see Fig. 6). The temporal alignment of neural signals and breathing after undergoing several minutes of the task suggests dynamic attunement facilitates coordination of the brain, breathing, and environment across longer timescales like minutes or potentially even longer.

The temporal alignment of brain activity at the Cz channel and breathing with external inputs over shorter and longer timescales suggests a potential bridge between the body and the environment. Such intricate temporal coordination may play a pivotal role in navigating complex environmental contexts over shorter and more extended periods of time, influencing behavioral outcomes (see Fig. 7). Our data support that dynamical features are shared among localized brain activity, breathing, and environmental stimuli. This allows crossing their internal-external divide by dynamics as their shared feature (i.e., as their “common currency”59,60).

Overall, our findings support two dynamic mechanisms of brain-breathing alignment. First, we show that the lungs and brain synchronize their activity with one another over shorter timescales like milliseconds or seconds as evidenced by coherence, cross-frequency coupling, and entrainment. Second, operating over longer timescales of minutes if not hours, our empirical data suggest that the temporal structure of the environmental inputs shapes the temporal structure of the activities within both lungs and brain activity at the Cz channel. This is indicated by the frequency-specific adaptations in their power spectrums to the exact frequency of the intertrial interval of the task (i.e., dynamic attunement). Dynamic attunement describes a form of alignment in which the lungs and brain adapt the temporal structure of their activities like in their power spectra to the specific temporal characteristics of the external environmental inputs. Brain-breathing dynamic attunement is further supported by the increase in coherence between the lungs and brain at 0.769 Hz during the task which indicates their common alignment to a shared third party (i.e., the input dynamics). Hence, the observed increases in the amounts of synchrony between the lung and local brain activity during task states, coupled with the increases in their power peak at the exact intertrial interval of the task, suggest that there is a threefold alignment of neural activity, breathing and environment through their timing with dynamics being shared among them as their “common currency”59,60.

While these data offer valuable insights, the modest sample size in the empirical section of the paper may limit the generalizability of our findings. In addition, we focused on neural activity at the Cz electrode due to its implication in auditory processing55. This approach captures localized brain responses that may not be reflective of broader neural dynamics across the entire brain. This limitation restricts our ability to generalize findings to other brain regions and functions. Moreover, while we have provided an overview of the interactions between breathing and local brain activity in response to external auditory inputs, a key feature missing in this work is a link to behavioral outcomes. Future investigations should aim to bridge the gap between the described neurophysiological mechanisms and observed behavior by comparing how the input (the stimulus) directly relates to the output (the behavior) as mediated by what is in between (the physiology).

More specifically, future studies should employ methods that relate how the dynamics of the behavior, e.g., the output, directly relate to the dynamics of the stimulus, e.g., the input, as mediated by the dynamics of the body’s physiology in a given frequency range, e.g., brain and breathing. The elucidation of these techniques may provide key insights into the exact mechanisms by which neurophysiological features of brain breathing coupling are related to behavior.

Conclusion

In conclusion, combining review and empirical data, we demonstrate two potential mechanisms operationalized across different timescales, in coordinating local brain activity at the Cz electrode and breathing as well as their alignment to external inputs. The first mechanism, operating on shorter timescales from milliseconds to seconds, concerns the synchronization of the brain and breathing in terms of coherence, cross-frequency coupling and entrainment. The second mechanism operates over longer timescales from several minutes or potentially even longer and thereby refers to what we describe as dynamic attunement.

Together, these observations attribute a key role of dynamical properties in directly connecting three systems (i.e., brain, lungs and the environment) that, in their timescales, are thought to be very different. Hence, albeit tentatively, we suppose that dynamics are shared by the brain, breathing and environment across shorter and longer timescales providing their “common currency”59,60. Our findings enhance the understanding of brain-breathing coupling in response to external inputs framing their mechanisms including their potential relevance for behavior in terms of “Spatiotemporal Neuroscience”59,60

Finally, if linked to behavior and cognition in the future, the mechanisms of brain-breathing environment coupling could carry major clinical implications for mental and cognitive disorders where the subjects’ alignment to their respective environmental contexts is severely compromised61. Hence, our proposed view of brain-breathing-environment coupling in terms of dynamics featured by and operating across different timescales may allow for novel diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities in the future.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw dataset used for analysis during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The source data underlying Figs. 3,4,5, and 6 can be found in the following Figshare repository https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25429780.v3

Code availability

The code used for analysis during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kluger, D. S. & Gross, J. Respiration modulates oscillatory neural network activity at rest. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001457 (2021).

Heck, D. H., Kozma, R. & Kay, L. M. The rhythm of memory: how breathing shapes memory function. J. Neurophysiol. 122, 563–571 (2019).

Varga, S. & Heck, D. H. Rhythms of the body, rhythms of the brain: Respiration, neural oscillations, and embodied cognition. Conscious. Cogn. 56, 77–90 (2017).

Heck, D. H. et al. Recent insights into respiratory modulation of brain activity offer new perspectives on cognition and emotion. Biol. Psychol. 170, 108316 (2022).

Del Negro, C. A., Funk, G. D. & Feldman, J. L. Breathing matters. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 351–367 (2018).

Noble, D. J. & Hochman, S. Hypothesis: pulmonary afferent activity patterns during slow, deep breathing contribute to the neural induction of physiological relaxation. Front. Physiol. 10, 1176 (2019).

Melnychuk, M. C. et al. Coupling of respiration and attention via the locus coeruleus: effects of meditation and pranayama. Psychophysiology 55, e13091 (2018).

Melnychuk, M. C., Murphy, P. R., Robertson, I. H., Balsters, J. H. & Dockree, P. M. Prediction of attentional focus from respiration with simple feed-forward and time delay neural networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 32, 14875–14884 (2020).

Melnychuk, M. C., Robertson, I. H., Plini, E. R. G. & Dockree, P. M. A bridge between the breath and the brain: synchronization of respiration, a pupillometric marker of the locus coeruleus, and an EEG marker of attentional control state. Brain Sci. 11, 1324 (2021).

Kluger, D. S., Gross, J. & Keitel, C. A dynamic link between respiration and arousal. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.06.561178 (2023).

Kluger, D. S. et al. Modulatory dynamics of periodic and aperiodic activity in respiration-brain coupling. Nat. Commun. 14, 4699 (2023).

Yackle, K. et al. Breathing control center neurons that promote arousal in mice. Science 355, 1411–1415 (2017).

Johannknecht, M. & Kayser, C. The influence of the respiratory cycle on reaction times in sensory-cognitive paradigms. Sci. Rep. 12, 2586 (2022).

Perl, O. et al. Human non-olfactory cognition phase-locked with inhalation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 501–512 (2019).

Nakamura, N. H., Fukunaga, M. & Oku, Y. Respiratory modulation of cognitive performance during the retrieval process. PLoS ONE 13, e0204021 (2018).

Zelano, C. et al. Nasal respiration entrains human limbic oscillations and modulates cognitive function. J. Neurosci. 36, 12448–12467 (2016).

Nakamura, N. H., Oku, Y. & Fukunaga, M. ‘Brain-breath’ interactions: respiration-timing-dependent impact on functional brain networks and beyond. Rev. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1515/revneuro-2023-0062 (2023).

Nakamura, N. H., Furue, H., Kobayashi, K. & Oku, Y. Hippocampal ensemble dynamics and memory performance are modulated by respiration during encoding. Nat. Commun. 14, 4391 (2023).

Northoff, G., Klar, P., Bein, M. & Safron, A. As without, so within: how the brain’s temporo-spatial alignment to the environment shapes consciousness. Interface Focus 13, 20220076 (2023).

Allen, M., Varga, S. & Heck, D. H. Respiratory rhythms of the predictive mind. Psychol. Rev. 130, 1066–1080 (2023).

Juventin, M. et al. Respiratory rhythm modulates membrane potential and spiking of nonolfactory neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 130, 1552–1566 (2023).

Brændholt, M. et al. Breathing in waves: understanding respiratory-brain coupling as a gradient of predictive oscillations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 152, 105262 (2023).

Adrian, E. D. Olfactory reactions in the brain of the Hedgehog. J. Physiol. 100, 459–473 (1942).

Ito, J. et al. Whisker barrel cortex delta oscillations and gamma power in the awake mouse are linked to respiration. Nat. Commun. 5, 3572 (2014).

Tort, A. B. L., Brankačk, J. & Draguhn, A. Respiration-entrained brain rhythms are global but often overlooked. Trends Neurosci. 41, 186–197 (2018).

Herrero, J. L., Khuvis, S., Yeagle, E., Cerf, M. & Mehta, A. D. Breathing above the brain stem: volitional control and attentional modulation in humans. J. Neurophysiol. 119, 145–159 (2018).

Goheen, J., Anderson, J. A. E., Zhang, J. & Northoff, G. From lung to brain: respiration modulates neural and mental activity. Neurosci. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-023-01070-5 (2023).

Fincham, G. W., Strauss, C., Montero-Marin, J. & Cavanagh, K. Effect of breathwork on stress and mental health: a meta-analysis of randomised-controlled trials. Sci. Rep. 13, 432 (2023).

Banushi, B. et al. Breathwork interventions for adults with clinically diagnosed anxiety disorders: a scoping review. Brain Sci. 13, 256 (2023).

Meuret, A. E., Ritz, T., Wilhelm, F. H. & Roth, W. T. Voluntary hyperventilation in the treatment of panic disorder-functions of hyperventilation, their implications for breathing training, and recommendations for standardization. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 25, 285–306 (2005).

Meuret, A. E. & Ritz, T. Hyperventilation in panic disorder and asthma: empirical evidence and clinical strategies. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 78, 68–79 (2010).

Blechert, J., Wilhelm, F. H., Meuret, A. E., Wilhelm, E. M. & Roth, W. T. Experiential, autonomic, and respiratory correlates of CO2 reactivity in individuals with high and low anxiety sensitivity. Psychiatry Res. 209, 566–573 (2013).

Asmundson, G. J., Norton, G. R., Wilson, K. G. & Sandler, L. S. Subjective symptoms and cardiac reactivity to brief hyperventilation in individuals with high anxiety sensitivity. Behav. Res. Ther. 32, 237–241 (1994).

Karavaev, A. S. et al. Synchronization of infra-slow oscillations of brain potentials with respiration. Chaos 28, 081102 (2018).

Hinterberger, T., Walter, N., Doliwa, C. & Loew, T. The brain’s resonance with breathing-decelerated breathing synchronizes heart rate and slow cortical potentials. J. Breath. Res. 13, 046003 (2019).

Sviderskaya, N. E. & Bykov, P. V. Spatial organization of EEG activity during active hyperventilation (cyclic breath) I. General patterns of changes in brain functional state and the effect of paroxysmal activity. Hum. Physiol. 32, 140–149 (2006).

Holper, L., Scholkmann, F. & Seifritz, E. Time-frequency dynamics of the sum of intra- and extracerebral hemodynamic functional connectivity during resting-state and respiratory challenges assessed by multimodal functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Neuroimage 120, 481–492 (2015).

Oku, Y. Temporal variations in the pattern of breathing: techniques, sources, and applications to translational sciences. J. Physiol. Sci. 72, 22 (2022).

González, J. et al. Breathing modulates gamma synchronization across species. Pflug. Arch. 475, 49–63 (2023).

Gonzalez, J., Torterolo, P. & Tort, A. B. L. Mechanisms and functions of respiration-driven gamma oscillations in the primary olfactory cortex. Elife 12, e83044 (2023).

Cavelli, M. et al. Nasal respiration entrains neocortical long-range gamma coherence during wakefulness. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/430579 (2018).

Kotz, S. A., Ravignani, A. & Fitch, W. T. The evolution of rhythm processing. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22, 896–910 (2018).

Rosso, M., Moens, B., Leman, M. & Moumdjian, L. Neural entrainment underpins sensorimotor synchronization to dynamic rhythmic stimuli. Neuroimage 277, 120226 (2023).

Lakatos, P., Karmos, G., Mehta, A. D., Ulbert, I. & Schroeder, C. E. Entrainment of neuronal oscillations as a mechanism of attentional selection. Science 320, 110–113 (2008).

Lakatos, P., Gross, J. & Thut, G. A new unifying account of the roles of neuronal entrainment. Curr. Biol. 29, R890–R905 (2019).

Calderone, D. J., Lakatos, P., Butler, P. D. & Castellanos, F. X. Entrainment of neural oscillations as a modifiable substrate of attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18, 300–309 (2014).

Criscuolo, A., Schwartze, M. & Kotz, S. A. Cognition through the lens of a body-brain dynamic system. Trends Neurosci. 45, 667–677 (2022).

Charalambous, E. & Djebbara, Z. On natural attunement: shared rhythms between the brain and the environment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 155, 105438 (2023).

Potts, J. T., Rybak, I. A. & Paton, J. F. R. Respiratory rhythm entrainment by somatic afferent stimulation. J. Neurosci. 25, 1965–1978 (2005).

Henry, M. J., Herrmann, B., Kunke, D. & Obleser, J. Aging affects the balance of neural entrainment and top-down neural modulation in the listening brain. Nat. Commun. 8, 15801 (2017).

Harbour, E., van Rheden, V., Schwameder, H. & Finkenzeller, T. Step-adaptive sound guidance enhances locomotor-respiratory coupling in novice female runners: a proof-of-concept study. Front. Sports Act. Living 5, 1112663 (2023).

Haas, F., Distenfeld, S. & Axen, K. Effects of perceived musical rhythm on respiratory pattern. J. Appl. Physiol. 61, 1185–1191 (1986).

Sakaguchi, Y. & Aiba, E. Relationship between musical characteristics and temporal breathing pattern in piano performance. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10, 381 (2016).

Klar, P., Çatal, Y., Langner, R., Huang, Z. & Northoff, G. Scale-free dynamics of core-periphery topography. Hum. Brain Mapp. 44, 1997–2017 (2023).

Vandewalle, G. et al. Blue light stimulates cognitive brain activity in visually blind individuals. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 25, 2072–2085 (2013).

Scherer, M., Wang, T., Guggenberger, R., Milosevic, L. & Gharabaghi, A. FiNN: a toolbox for neurophysiological network analysis. Netw. Neurosci. 6, 1205–1218 (2022).

Tort, A. B. L. et al. Dynamic cross-frequency couplings of local field potential oscillations in rat striatum and hippocampus during performance of a T-maze task. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 20517–20522 (2008).

González, J., Torterolo, P. & Tort, A. B. L. Mechanisms and functions of respiration-driven gamma oscillations in the primary olfactory cortex. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.24.489324.

Northoff, G., Wainio-Theberge, S. & Evers, K. Is temporo-spatial dynamics the ‘common currency’ of brain and mind? In Quest of ‘Spatiotemporal Neuroscience’. Phys. Life Rev. 33, 34–54 (2020).

Northoff, G., Wainio-Theberge, S. & Evers, K. Spatiotemporal neuroscience - what is it and why we need it. Phys. life Rev. 33, 78–87 (2020).

Northoff, G., Daub, J. & Hirjak, D. Overcoming the translational crisis of contemporary psychiatry—converging phenomenological and spatiotemporal psychopathology. Mol. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02245-2 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by an NSERC Discovery Grant (DGECR-2022-00309) and a Canada Research Chair (Tier II, CRC-2020-00174) to JAEA. This project was supplied with equipment for data acquisition by GN (European Union’s Horizon 2020 Framework Program for Research and Innovation No. 785907; Human Brain Project SGA2). GN is also grateful to CIHR, NSERC, and SSHRC for supporting his tri-council grant from the Canada–UK Artificial Intelligence (AI) Initiative The self as agent–environment nexus: crossing disciplinary boundaries to help human selves and anticipate artificial selves‘ (ES/T01279X/1) (together with Karl J. Friston from the UK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G.—Conceptualization, data acquisition, analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. A.W.—Conceptualization, data acquisition, analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. L.A.—Data acquisition. AWolff—Conceptualization. J.A.—Conceptualization, preparation of the manuscript, and funding G.N.—Conceptualization, preparation of the manuscript, and equipment.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Christian Beste and Manuel Breuer.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Goheen, J., Wolman, A., Angeletti, L.L. et al. Dynamic mechanisms that couple the brain and breathing to the external environment. Commun Biol 7, 938 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06642-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06642-3

This article is cited by

-

Central nervous system control of breathing in natural conversation turn-taking

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Using ECG-derived respiration for explaining BOLD-fMRI fluctuations during rest and respiratory modulations

Scientific Reports (2025)