Abstract

The negative membrane potential within bacterial cells is crucial in various essential cellular processes. Sustaining a hyperpolarised membrane could offer a novel strategy to combat antimicrobial resistance. However, it remains uncertain which molecules are responsible for inducing hyperpolarization and what the underlying molecular mechanisms are. Here, we demonstrate that chemically diverse antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) trigger hyperpolarization of the bacterial cytosolic membrane when applied at subinhibitory concentrations. Specifically, these AMPs adopt a membrane-induced amphipathic structure and, thereby, generate hyperpolarization in Escherichia coli without damaging the cell membrane. These AMPs act as selective ionophores for K+ (over Na+) or Cl− (over H2PO4− and NO3−) ions, generating diffusion potential across the membrane. At lower dosages of AMPs, a quasi-steady-state membrane polarisation value is achieved. Our findings highlight the potential of AMPs as a valuable tool for chemically hyperpolarising bacteria, with implications for antimicrobial research and bacterial electrophysiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mitigating the effects of antimicrobial resistance is a constant medical need and one of the most significant challenges1. Efforts are devoted to introducing faster methodologies for antibiotic development2,3,4, but the new compounds rarely show a lower propensity for resistance5,6,7. Therefore, adjuvant strategies to preserve or improve the efficacy of existing antibiotic drugs are attractive approaches8,9, and new adjuvant mechanisms are in demand10.

Several previous observations point to hyperpolarization as a potentially useful adjuvant approach. A linear relationship was found between the probability of hyperpolarization and cell death11,12. A direct connection has been demonstrated between bacterial hyperpolarization and the killing efficacy of an aminoglycoside has been demonstrated13, where the elevated membrane potential was induced by ATP accumulation due to disrupted ribosomal protein synthesis. The increased polarisation of the membrane caused by the loss of control exerted by the PhoP regulator on the energised membrane decreased bacterial virulence14. The direct antimicrobial effect of bacterial hyperpolarization was also suggested when polarisation was generated with nanoporous gold without membrane damage15. ATP synthesis and bacterial metabolic rate are directly related to membrane potential16,17. Bacterial metabolic rate, in turn, plays a determining role in antibiotic lethality18. Stimulated cellular metabolism with increased ATP production is sufficient to improve antibiotic efficacy without increased growth. This finding connects hyperpolarization and faster metabolism with reduced antimicrobial resistance, pointing to a general sensitisation and adjuvant strategy. As a proof of principle, we recently showed that designer peptides that hyperpolarise the bacterial membrane act as in vivo adjuvants that restore and improve the sensitivity of resistant and wild-type strains to small-molecule antibiotics19. Inhibitory concentrations of nalidixic acid and ampicillin decreased markedly in vivo with sublethal doses of hyperpolarising sequences derived from the antimicrobial peptide PGLa (AMP). The hyperpolarization was caused by selective cross-membrane ion transport, generating a stable diffusion potential without rupturing the membrane.

A mechanistic understanding of direct chemical-biophysical hyperpolarization is required to elaborate further on this emerging antibacterial adjuvant strategy. Revealing the structural determinants of the hyperpolarization effect at the molecular level is essential. To this end, we aimed to systematically enlarge the pool of the hyperpolarising compounds to reach a reasonable chemical diversity that facilitates structure-activity relationship investigations. Because our first serendipitous hits belong to or are analogous with antimicrobial peptides of natural origin, we set out to search for bacterial hyperpolarization effects in the class of AMPs. The following facts justify our approach. First, bacterial membrane-specific ion transport phenomena were detected among cationic AMPs20 without membrane rupture. Second, bacterial membrane hyperpolarization effects were observed sporadically for AMPs21. Third, AMPs rarely induce antimicrobial resistance, showing widespread collateral sensitivity and reduced cross-resistance to small molecule antibiotics, decreasing the risk of adjuvant-induced antimicrobial resistance8,22.

After testing a structurally diverse panel of AMPs, we found that this class of materials is a rich source of hyperpolarising agents on E. coli when applied at subinhibitory (sub-MIC) concentrations. Selective ion transport-induced diffusion potential generation is frequent among cationic AMPs in a single bilayer model. In contrast, bacterial hyperpolarization is likely only for sequences that can environment-dependently fold and unfold while diffusing across the complex bacterial cell wall to reach the cytoplasmic membrane.

Results

Selection of a structurally diverse panel of AMPs

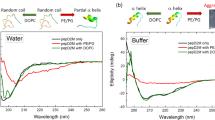

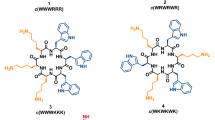

In search of the bacterial hyperpolarization effects, we chose 17 AMP sequences (Table 1). The selection was based on the secondary structure, including α-helix, polyproline helix, disulfide-stabilised β-sheet, and disordered sequences. The folding of AMPs is often dynamic and environment-dependent23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33, where the negatively charged membrane induces the structure. Therefore, we specifically focused on sampling cationic AMPs with membrane-induced secondary structures (Figs. 1 and 2). The inducibilities reported in the literature (see citations in Figs. 1 and 2) were confirmed by our CD measurements at 0.5 MIC and under identical conditions for all AMPs studied. Disulphide-stabilised AMPs were oxidised to their native structure, confirmed by enzyme digestion and HPLC-MS analysis (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Thus, the panel of AMP sequences samples the conformational space in two dimensions: the type of the bioactive secondary structure and its membrane inducibility. It is also important that AMPs can have specific targets in addition to lytic effects on the membrane, which can modulate the net effect on bacterial electrophysiology34.

We recorded CD curves under identical conditions (100 mM peptide without and with 1 mM DOPC/DOPG large unilamellar vesicles (LUV) in 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.2) to ensure the reproducibility of structural characteristics in this study. The coordinates of the secondary structures in the membrane were obtained by molecular modelling using the experimental restrictions reported in the relevant citations23,24,25,26,27.

We recorded CD curves under identical conditions (100 mM peptide without and with 1 mM DOPC/DOPG large unilamellar vesicles (LUV) in 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.2) to ensure the reproducibility of structural characteristics in this study. The coordinates of the secondary structures in the membrane were obtained by molecular modelling using the experimental restrictions reported in the relevant citations28,29,30,31,32,33.

Membrane-induced AMP structures generate bacterial hyperpolarization in E. coli at sublethal concentrations

We measured changes in the polarisation of the cytosolic membrane potential of E. coli cells in response to AMPs. We applied subinhibitory concentrations, uniformly 0.5 MIC (Supplementary Table 1), to avoid total membrane rupturing. Polarisation was monitored by flow cytometric analysis using the membrane potential sensitive dye DiOC2(3) (Fig. 3a–c and Supplementary Figs. 3–6)35. We performed all measurements after 15 min of incubation. The sublethal concentrations of MAG2a, MAG2, BAC5, BUF2, CP1, and GUA2 switched the whole population of bacteria into a hyperpolarised state. For PGL, PGLa, PGRLa, R8, INDa, LL37, and IND, a bimodal distribution of membrane polarisation was observed with a significant amount of hyperpolarised cells. The rest of the population remained unperturbed or slightly depolarised. Sequences TP2, TP2K, and PROT1 perturbed the polarisation level and strongly sharpened the distribution, but significant hyperpolarization could not be detected. For AP, no effect on membrane polarisation was observed.

The flow cytometric membrane polarisation assay (BacLight) was carried out in E. coli using the fluorescent membrane potential indicator dye DiOC2(3). Representative histograms of the log ratio calculated from the red and green channels for LL37 (a) MAG2 (b) and AP (c) (yellow untreated, blue AMP treated). Population means of the red/green fluorescence ratios normalised to the values obtained for the untreated cells (d). Data are based on three biological replicates measured at 0.5 MIC AMP concentrations. Ratios below one correspond to depolarisation, and values above one indicate hyperpolarization. Values are displayed against the inducibility of the secondary structure. AMP-induced bacterial hyperpolarization detected for hyperpolarising sequences at concentrations of MIC of 0.25 (green), 0.5 (grey) and 0.75 (brown), n = 3 (e).

These findings revealed that many of the AMPs studied here can induce hyperpolarization at a sequence-dependent level. We calculated the averaged hyperpolarization effect for the biological replicates (Supplementary Fig. 7) and compared the readout with the structural features of the sequences (Fig. 3d). AMPs with membrane-induced helical structures tend to generate hyperpolarization at a subinhibitory concentration without depolarisation of the bacteria. In contrast, sequences having membrane-insensitive conformations cannot shift the bacterial population to a dominantly hyperpolarised state. Structurally, the lack of disulphide bond(s) and the membrane-induced dynamic helical structure characterise the hyperpolarising sequences. In principle, the overall hydrophobic surface area and the net charge can be associated with the AMP-membrane interactions, but these descriptors do not explain the membrane-inducibility (Supplementary Fig. 8). A specific side chain pattern is needed, which shapes the separate hydrophobic and ionic faces of the helices without self-aggregation and sufficient residual flexibility. We found no correlation with the existence of the published non-membrane lytic targets.

We tested whether these AMPs can hyperpolarise the membranes of a Gram-positive organism and experimented with the Gram-positive Staphylococcus epidermidis. First, we determined the MICs for a selected panel of AMPs, and we found considerably elevated values compared with the E. coli MICs (Supplementary Table 2). For AMPs that show decent antibiotic effects against S. epidermidis, we performed membrane potential assays at subinhibitory concentrations (0.5 MIC). Under these circumstances, we found depolarisation for the studied AMPs (Supplementary Fig. 9). Due to the relatively high MICs, the antibiotic concentrations used in this experiment were higher for S. epidermidis than for E. coli. These observations suggest that the sub-MIC AMP-induced hyperpolarization can not be generated in the Gram-negative S. epidermidis.

To assess whether AMPs could generate nonspecific currents through the membrane of eukaryotic cells, we have measured the membrane potential of activated human peripheral lymphocytes using the patch clamp technique in I = 0 current clamp mode. We exposed human cells to PGLa and CP1. To suppress unwanted peptidase effects, PGLb119, a foldameric analogue of PGLa, was measured. The perfusion of high-concentration potassium solution (HK) was used as a positive control, which caused a reversible shift of the membrane potential close to 0 mV, which was followed by the application of PGLa (Supplementary Fig. 10a), PGLb1 (Supplementary Fig. 10b) or CP1 (Supplementary Fig. 10c). Each compound was dissolved in control bath solution at 0.5 MIC concentrations separately. In our measurements, we did not observe any relevant changes in the resting membrane potential in response to long-term exposure to any of these materials, as shown by representative traces (Supplementary Fig. 10a–c). Quantitative analysis of the data determined the relative changes in membrane potential due to exposure compared to the initial resting potential of the given cell (ΔEm = Emexposed – EmNR) (Supplementary Fig. 10d). PGLa, PGLb1 and CP1 induced negligible changes in membrane potential (−0.81 ± 0.77, 0.49 ± 0.41 and −0.17 ± 0.82, respectively) suggesting that these compounds do not induce nonspecific conductance of ionic currents in eukaryotic cells. We note that the AMPs were unlikely to internalise into the cytosol and organelles within the time scale of the experiments excluding the potential intracellular effects.

The concentration dependence of the hyperpolarization suggests an AMP-induced diffusion potential

We suggested in our earlier publication19 that AMP-induced hyperpolarization is due to the diffusion potential, which is caused by the different relative ion permeabilities facilitated by the peptide-mediated cross-membrane ion transport. As long as the AMPs’ concentration is sufficient for binding to the membrane and forming the necessary ionophoric structure, the relative ion permeabilities facilitated by the AMPs are expected to remain approximately constant. This hypothesis predicts that the diffusion potential does not decrease upon lowering the AMP concentration while above the critical limit. In contrast, the AMPs’ direct killing effect is based on membrane destruction around and above the MIC, which is concentration-dependent. Getting closer to the MIC value, the probability of nonselective pore formation and depolarisation increases36,37. This effect can compete with the diffusion potential, which causes a decreasing polarisation as the AMP concentration is increased toward the MIC. To test this hypothesis, we performed measurements in the range of 0.25 – 0.75 MIC. We observed increasing hyperpolarization with the lowered AMP concentrations, corroborating the presence of the diffusion potential as the underlying mechanism of the hyperpolarization (Fig. 3e).

AMPs induce diffusion potential in large unilamellar vesicles

AMPs studied here, except for AP, perturb bacterial electrophysiology at subinhibitory concentrations without general cell depolarisation. Hyperpolarization observed for the bacterial membrane excludes extensive cytosolic membrane damage or non-selective pore formation. This contrasts starkly with the established membrane rupturing mechanism for cationic AMPs at lethal doses38, raising the question of the possible hyperpolarization mechanism. In addition to the bacterial lipid membrane, no cell target is known for MAG2, GUA, R8, and PGLa at inhibitory concentrations. Therefore, we hypothesised that the perturbation of the polarisation in bacteria is also caused by direct membrane–AMP interactions. To test this phenomenon, we set up a cytosolic bacterial membrane mimetic DOPG:DOPC large unilamellar vesicle (LUV) system, where the AMP-induced membrane potential changes can be monitored with the voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye oxonol VI19,39,40. The LUV samples were prepared with different ion gradients at constant pH 7.2 to facilitate the detection of any dynamic polarisation effect. For cations, 100 mM NaCl (inside) and 100 mM KCl (outside) were applied. The anion gradient was established with 100 mM NaCl (inside) and 100 mM NaH2PO4 or NaNO3 (outside).

The fluorescence change of oxonol VI upon membrane polarisation depends on the specific membrane system, wavelength, and dye concentration41. We probed the response of oxonol VI with the K+-selective ionophore valinomycin and the cation gradient. We found that the inside positive polarisation induced with valinomycin and the K+-outside cation gradient caused fluorescence to decrease at the emission wavelength of 640 nm (Supplementary Fig. 11). The validating K+-inside experiment led to increasing fluorescence intensity, establishing the fluorescence probe’s sensitivity to the membrane voltage polarity in this setup42.

Next, we recorded the membrane potential changes generated by AMPs at 0.5 MIC in the presence of the cation gradient. The ion gradient-dependent fluorescence intensity curves revealed that most of the AMPs (PROT1, TP2K, TP2, IND, LL37, INDa, R8, PGRLa, PGLa, PGL, GUA2, BUF2, BAC5, MAG2 and MAG2a) induced inside positive diffusion potential (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13). This finding indicates that AMPs facilitate higher cross-membrane permeability for K+ in comparison to Na + ; that is, AMPs are K+ selective ionophores at sublethal concentrations. For AP and CP1, no diffusion potential appeared in the cation gradient LUV model. Measurements with inside Cl− anion gradients against H2PO4− also caused inside positive diffusion potential in general (Supplementary Figs. 12c and 13c). This points to a higher cross-membrane permeability for Cl− relative to H2PO4−, leading to a Cl− selective anion transport. The phenomenon appeared uniformly except for AP. We also carried out these measurements with NaCl inside and NaNO3 outside gradient to eliminate potential osmotic stress due to acid-base equilibrium of the phosphate species (Supplementary Figs. 12d and 13d). The diffusion potential generated by Cl− selectivity was observed against NO3−.

We concluded that the AMPs studied induced diffusion potential in the LUV model in a sequence-dependent manner (Fig. 4). The fluorescence intensity change demonstrated that the AMPs generate diffusion potential through K+- or Cl−-selective (over Na+ and H2PO4−, respectively) cross-membrane ion transport or both. These findings support that direct membrane–AMP interactions at subinhibitory concentrations can shape the diffusion potential across a lipid bilayer. However, the membrane-induced structure was not a determining factor in generating the diffusion potential in the LUV bilayer model. This observation strongly suggests that the components of the cell wall outside the cytosolic membrane modulate the bacterial hyperpolarization effect.

Scheme of the Na+/K+ gradient model with oxonol VI in the membrane (lilac circles) (a). Representative fluorescence change of oxonol VI upon adding PGLa (at t = 0) to the Na+/K+ gradient system. The negative change indicates a positive inside potential (b). AMP-induced fluorescence intensity decreases, implying the diffusion potential for the K+/Na+ gradient model (red), n = 40 (c). Schematic of the Cl−/H2PO4− gradient model with oxonol VI in the membrane (lilac circles) (d). Representative fluorescence change of oxonol VI upon adding PGLa (at t = 0) to the Cl−/H2PO4− gradient system (e). AMP-induced fluorescence intensity decreases, indicating the diffusion potential for the Cl−/H2PO4− gradient model (blue), n = 40 (f).

AMPs maintain a quasi-steady state ion gradient

The kinetics of the potential change revealed that the diffusion potential is rapidly built up after adding the AMPs. After 15 min, the polarisation converged to a stable non-zero value or drifted slowly. Since a constant diffusion potential requires a steady-state cross-membrane ion gradient43, we hypothesised that AMPs facilitate the voltage-generating infinitesimal electrogenic transport but do not fully dissipate the ion concentration gradients across the membrane. Levelling of intra- and extravesicular concentrations at a macroscopic level would require an effective electroneutral ion exchange (e.g., Na+/K+ and Cl−/H2PO4−) activity. We directly measured the time-dependent ion concentration levels in LUVs using NMR spectroscopy to test the extent of the macroscopic ion exchange across the bilayer. Na+, Cl−, and H2PO4− were monitored by detecting 23Na, 35Cl, and 31P NMR signals in LUVs19. We established the same ion gradients as those applied in membrane potential measurements for the Na+/K+ and Cl−/NO3− setups. The Cl−/H2PO4− gradient was constructed with H2PO4− in the intravesicular lumen, facilitating the NMR experiment. Dy(PPP)27− and Co2+ were used as NMR shift reagents to distinguish between internal and external Na+ and Cl− resonances, respectively. External and internal phosphate signals could be determined without a shift reagent. Most AMPs showed time-dependent but limited cross-membrane ion exchange (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15). The ion exchange stopped or slowed after 20 min (Fig. 5), leading to a stable, steady-state ion gradient or a slow drift. This observation confirms that the AMPs do not dissipate the ion gradient rapidly, helping a quasi-steady-state sustained membrane potential. The rate-determining step in the exchange is the slow transport of the less favoured ion.

The non-electrogenic Na+/K+ exchange model (a). Validation of the NMR measurements at different internal and external 23Na+ concentrations. For 23Na, 1 mM Dy(PPP)27− chemical shift reagent was added (b). Initial exchange rates observed for AMPs in the Na+/K+ gradient model (c). The initial exchange rate is estimated by the slope of the linear regression to the first four data points. The error bars indicate the standard error of slope. Representative time-dependent exchange curve for PGLa in the Na+/K+ gradient model (d). The non-electrogenic Cl−/H2PO4− exchange model (e). Validation of the NMR measurements at different internal and external 31P concentrations, no shift reagent was needed for 31P (f). Initial exchange rates observed for AMPs in the Cl−/H2PO4− gradient model (g). The initial exchange rate is estimated by the slope of the linear regression to the first three data points. The error bars indicate the standard error of slope. Representative time-dependent exchange curve for BUF2 in the Cl−/H2PO4− gradient model (h).

Discussion

In this work, we found that the class of AMPs is a rich source of substances that can switch on bacterial hyperpolarization. Structure-activity relationship analysis revealed that AMPs with membrane-induced amphipathic structures can elicit hyperpolarization in E. coli at sub-MIC concentrations. The lowered concentration prevented membrane rupture, while AMP-mediated selective ion transport facilitated shaping a diffusion potential. To describe the extent of the membrane polarisation as a function of the relative permeabilities and ion concentrations, the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz model is an adequate framework, and in future work, we plan to explore the exact quantitative relationship. Our results strongly suggest that the environment-dependent structure is essential to cross the bacterial cell wall without damaging the membrane. The bacterial cell wall is a formidable barrier for antibacterial compounds due to the multiple hydrophilic layers with lipophilic and negatively charged layers3. Crossing such a complex shield without a rupturing effect requires a flexible structure adapting to its actual environment. Thus, generating the diffusion potential at the inner cytosolic membrane is possible (Fig. 6). We note that bacteria can, in principle, counteract the AMPs’ hyperpolarization effect, but these mechanisms were not studied in this work.

AMPs with membrane-induced bioactive structure and limited hydrophobicity can escape the membrane interior and diffuse across the pores of the bacterial cell wall. When reaching the cytoplasmic membrane, diffusion potential generation becomes possible (a). Folded structures with dominantly hydrophobic side chains display limited diffusion across the cell wall, effectively decreasing the AMP’s ionophore activity at the cytoplasmic membrane (b). (Created with BioRender.com).

In the LUV model, AMPs could not dissipate the ion gradient beyond an initial cross-membrane exchange phenomenon during the build-up of membrane polarisation. This observation suggests that the early transient exchange is blocked by the potential-coupled insertion geometry of the peptidic structure into the membrane44, which may contribute to the ion selectivity.

AMPs have been studied for their ion transport activity, focusing on cation leakage. There are various mechanisms of action for peptides with ionophore activity. For example, Gramicidin A can transport ions when two monomers fuse at the opposite end to form a dimer ion channel4,17. Conversely, valinomycin, a cyclic peptide, traps K+ in its hydrophilic core and ferries across the lipid membrane bilayer45. Recent studies about the mechanism of valinomycin suggest binding to anion while trapping K+46. However, little was known about how AMPs affect the transport of physiologically relevant ions without membrane disruption47. PGLa19, TP448, and guavanin 230 have been found to induce hyperpolarization at sub-MIC concentrations. For PGLa and its β-peptidic analogues, we noticed a connection between the hyperpolarization phenomenon and synergism with conventional antibiotics. We discovered that these peptides hyperpolarise bacterial membranes by selective ion transport at sub-MIC levels19. Our study indicates that selective ion transport is a generic feature for cationic AMPs with few exceptions.

The general phenomenon of unusual K+ selectivity of ion channels and ionophores has been repeatedly discussed in the literature, and our understanding is still incomplete. Multiple factors can contribute to this tendency. The first filter element is the difference between the hydration shells of K+ and Na+. Na+ interacts more strongly with its first hydration shell than K+, giving K+ a more flexible structure49. Thus, K+ dehydration activation energy is lower. It has also been pointed out that the low dielectric environment in the membrane interior contributes to the K+ selectivity50, and other pores/ionophores containing a different number/chemical type of coordinating groups from those observed in potassium channels could also select K+ over Na+. Experimental and theoretical investigations revealed that the higher surface charge density of Na+ can lead to trapping in and hindered disengagement from the pore51. Our results align with the ubiquitous nature of the K+-selective cross-membrane ion transport. Concerning the anion transport, the requirements of Cl− selectivity have been studied in the literature52. The authors conclude that Cl− selectivity is less dependent on the specific side chain pattern. It is connected to the interactions with the amide backbone. The AMPs studied here possess this feature. A recent study on an artificial Cl− channel indicated that an organic structure that is relatively simple compared with a channel protein could display Cl− selectivity53.

It is established that electrostatic interactions between cationic AMPs and the negatively charged bacterial membrane surface lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are essential in the lethal effect at and above the MIC dose. At the inhibitory level, the membrane-acting AMPs compromise the membrane integrity by dysfunction of the associated subsystems, ultimately leading to cell lysis and cell content release36,38. Still, these peptides are often produced naturally in a diluted environment, where reaching MIC level may not be possible54. Hence, it is compelling to focus on their action at sub-MIC as the recent studies show several effects, such as inhibition of biofilm formation55,56, inhibition of secretion of SpeB cysteine protease57, inhibition of production of toxins58, synergism with antibiotics19,59. Studies suggest that peptides may translocate through the membrane into the cytoplasm at sub-MIC concentration and can manipulate cell permeability by ion transport60. Our findings add a new aspect to the sub-MIC effects because hyperpolarization is coupled to many metabolic and signalling processes. Thus, already subinhibitory levels of AMPs are likely to reduce bacteria’s survival ability under antibacterial attacks of the host.

We conclude that AMPs with membrane-induced bioactive structures have an intrinsic sub-lethal effect on bacterial electrophysiology, which must be considered in studies with these materials.

Methods

Peptides

CP1, LL37, R8, and AP were purchased from ProteoGenix. The rest of the peptides were synthesised in the lab.

Synthesis and purification

Peptides were synthesised by SPPS using the automatic synthesiser Liberty Blue. Tentagel R RAM (0.19 mmol/g loading) and Wang resin were used for the synthesis of peptides with amidated C-terminal and free C-terminal, respectively. Loading was set manually for the Wang resin with the first amino acid of each peptide. 10% Piperazine in N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) as deprotection solution; N,N’-Diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) as an activator and Ethyl cyanohydroxyimino acetate (Oxyma) as activator base were used. Cleavage reagent containing a mixer of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/water/DL-dithiothreitol (DTT)/triisopropylsilane (TIS) (90 : 5 : 2.5 : 2.5) was used to cleave the peptides at room temperature for 3 h. TFA was removed with vacuum drying and precipitated in ice-cold diethyl ether. The resin was washed with acetic acid and water and then filtered. The filtered solution was lyophilised to get peptides in powder form. The peptides were purified with RP-HPLC on a C18 column (Phenomenex Luna, 250 × 10 mm) using water (containing 0.1% TFA) and Acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) as eluent A and B, respectively. A gradient of 0% to 60% over 80 min, at a flow rate of 4 ml min−1 was used. Purity was confirmed by analytical RP-HPLC and ESI-MS measurements using a C18 column (3.6 µm Aries peptide, 250 × 4.6 mm) water (containing 0.1% HCOOH) and Acetonitrile (0.1% HCOOH) as eluent A and B respectively. A gradient of 5% to 80% over 15 min was used at a flow rate of 0.7 ml min−1.

Oxidation of peptides with beta-sheet secondary structure (TP2, PROT1)

Purified powder peptide (reduced form) was dissolved in 20 mM ammonium acetate solution at 100 µg/mL concentration, and the pH was set to 7.4 with NaOH. The solution was kept in a glass vial with a lid open for 48 hours to oxidise in air. Completion of the oxidation process was confirmed with HPLC-MS. The peptide was then purified and lyophilised. The desired disulfide bond formation was identified with trypsin and chymotrypsin digestion methods.

Digestion by trypsin and chymotrypsin

The peptide was dissolved in 100 mM Tris HCl containing 10 mM CaCl2, pH 7.8. 1 mg/mL of enzyme stock was made in 1 mM HCl having 2 mM CaCl2. An appropriate amount of enzyme solution was added to the peptide to make the ratio of trypsin to peptide 1:20 and chymotrypsin to peptide 1:60. Solution was kept in a glass vial in a shaker for 24 hours at 25 °C. Sample taken at different time points. Digestion of the sample terminated by adjusting the pH to 2.0 with 10% trifluoroacetic acid.

Circular dichroism measurements

CD spectra of all the peptides were measured using Jasco J-1100 CD-spectrometer. Spectra were recorded using a 1 mm quartz cuvette, from 260 to 190 nm, at a scanning speed of 100 nm min-1 with 5 accumulations. 100 μM peptide stock solutions were prepared in Na-phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.2). LUVs were prepared with the same method described in the LUVs preparation section but in Na-phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.2) and without NaCl. Spectra were collected with and without 1 mM LUVs. The solvent baseline was subtracted in each case.

Preparation of large unilamellar vesicles

20 mM LUVs were prepared by mixing 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1’-rac-glycerol) (DOPG) in a molar ratio of 7:3 from chloroform stock in a round bottom flask. A thin lipid film was obtained by purging nitrogen gas for 20 min, and it was dried subsequently for 5 min with hot air to remove residual solvents from the film. The film was hydrated with 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.2, containing 100 mM NaCl/NaH2PO4 on a shaker for 1 hour and kept at 4 °C overnight to get a suspension of multilamellar vesicles. This was followed by 12 cycles of the freeze-thaw cycle. Vesicles were then extruded 12 times through an extruder (Albet Lifesciences) with a pore size of 200 nm. Unencapsulated NaCl/NaH2PO4 was removed by dialysis with 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.2, containing 100 mM KCl/NaH2PO4/NaNO3 using Slide-A-Lyzer Dialysis Cassette. The final volume was adjusted with a similar buffer used for dialysis.

Particle size, polydispersity index

LUVs were evaluated for mean particle size (Z-average), and polydispersity index analysis by the dynamic light scattering (DLS) method (Zetasizer, Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK) at 37 °C. 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.2, containing 100 mM NaNO3 or KCl was used to dilute the 20 mM liposome suspension to 1:14 for scanning in 1 cm disposable cuvettes. Data were analysed using the Zetasizer software.

NMR measurements

NMR spectra for ion transport study were recorded on a Bruker Ascend 500 spectrometer with a 5 mm BBO Prodigy Probe at 310 K. For 23Na NMR, 0.5 µL 1 M Dy(PPP)27- was added to 500 µL of 20 mM LUVs [NaCl (inside) KCl (outside)] as shift reagent. 23Na NMR: operating at 132.3124 MHz, spectral width 9 091 Hz, 64 data points, relaxation delay 0.1 s, Ninety-degree pulse 10 µs. For 31P NMR 500 µL of 20 mM LUVs [NaH2PO4 (inside) NaCl (outside)] was used. 31P NMR: operating at 202.474 MHz, spectral width 81 967 Hz, 65536 data points, relaxation delay 2 s, Ninety-degree pulse 12 µs. 35Cl NMR: operating at 49.0091 MHz, spectral width 10 000 Hz, 3000 data points, relaxation delay 0.1 s, ninety-degree pulse 20 μs. 2 μL 1 M Co(NO3)2 were added to 500 μL LUV suspension as a shift reagent in each sample.

Fluorescence measurements

Fluorescent measurements were done by using an Optima Fluostar plate reader. 0.2 mM LUVs containing 100 mM NaCl (inside) and 100 mM NaCl or KCl or NaH2PO4 (outside) were used for the measurements. 0.45 µM oxonol VI dye concentration was maintained in the final plate diluted freshly by the same 1 mg/mL ethanol stock buffer. The excitation wavelength was set to 580 nm (slit width 10 nm) and the emission wavelength to 640 nm (slit width 10 nm). From a mixture of LUVs and oxonol VI dye, 290 µl aliquots were added into Nunc 96-well transparent flat-bottom plates with 3 parallels. After the fluorescence flatlined, 10 µl of peptide stock solutions were added to the wells with a multi-channel pipette. The fluorescence response of buffer addition was used as background. All the measurements were done at 37 °C. The fluorescence intensity was normalised by (F−F0)/F0, where F is the average intensity of the peptides, and F0 is the average intensity of the buffer cells.

MIC measurements

MICs were determined using a standard serial broth dilution technique. Escherichia coli K-12 BW25113 and Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 51625 strains were used in this study. MIC measurements used two times serial dilution of antibiotic and an inoculum of 5 × 105 bacteria per ml as suggested by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines. Müller-Hinton II Broth medium was used. To avoid possible edge effects, rows A and H contained only media devoid of cells. The environment during incubation was also set to minimise evaporation and, hence, edge effects. After 18 h of incubation at 37 °C, raw A600 nm values were measured in a Biotek Synergy microplate reader. MIC was defined by a cut-off A600 nm value (mean + 2 s.d. of A600 nm values of bacteria-free wells containing only growth medium). Representative dose-response curves are given for AP, PROT1, GUA2, BUF2, and MAG2 in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 16).

Membrane potential assay

The BacLight bacterial membrane potential kit (Invitrogen, B34950) provides a fluorescent membrane potential indicator dye, DiOC2(3), along with CCCP and premixed buffer. At low concentrations, DiOC2(3) exhibits green fluorescence in all bacterial cells; however, as it becomes more concentrated in healthy cells that are maintaining a membrane potential, it causes the dye to self-associate and the fluorescence emission to shift to red (Supplementary Fig. 17). The red and green fluorescent bacterial populations are easily distinguished by using a flow cytometer. CCCP (10 μl of a 500 μM stock) is included in the kit for use as a control because it eradicates the proton gradient, eliminating the bacterial membrane potential. Bacterial cells were grown overnight in minimal salts medium optimised for AMPs at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. The overnight grown cultures were diluted into fresh MHB medium and grown further until cell density reached OD600 0.5.

The grown cultures were diluted to 107 cells per mL in filtered PBS buffer and treated with drug and DiOC2(3) (10 μM) for 15 min at room temperature (the measurement was taken after 25 min). According to a previous study35, the dye and the drug were used simultaneously. Stained bacteria were assayed in a CytoFlex S flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, United States) with a laser emitting at 485 nm. FL1 (green channel) was fitted with a 530/30 band pass (BP) filter, and the FL3 (red channel) was fitted with a 670 LP filter. The live and dead cell populations were separated on the basis of forward and side scattering intensities. The green and red channel results were analysed ratiometrically, and normalisation was applied to the untreated samples. We note that the normal distribution of the fluorescence intensities is not ensured.

Cells

For membrane potential measurements human peripheral lymphocytes were isolated from anonymous healthy donors’ blood with Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation. Collected cells were washed twice with Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hanks’ solution containing 25 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4. Cells were cultured for 2 to 5 days in 24-well culture plates in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 μg/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine at a density of 5 × 105 cells per mL in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The culture medium also contained 5, 7.5 or 10 μg/ml phytohemagglutinin A (Sigma-Aldrich), to increase K+ channel expression.

Electrophysiology

The patch-clamp technique in current-clamp mode was used to measure membrane potential of human peripheral lymphocytes using Axopatch 200B amplifiers connected to a computer via Digidata 1550B digitizers (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Patch-clamp data were acquired with pClamp10 (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Pipettes were pulled from GC 150F-15 borosilicate glass capillaries (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) in four stages with tip diameters between 0.5 and 1 µm with 3–5 MΩ resistance. Cells were identified for recording by using a TE2000 fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Before the measurements, cells were placed in the recording petri dish in the control bath solution (i.e., normal ringer solution, NR) consisting of 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.35, titrated with NaOH. Internal solution (in the pipette) consisted of 105 mM KF, 35 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES and 10 mM EGTA and was titrated to pH 7.36–7.38 with KOH, with a final K+ concentration of 160–165 mM. As a positive control, a high-concentration potassium solution (HK) was applied, which contained 150 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 5.5 mM glucose, 2.5 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.35. PGLa, PGLb1 and CP1 were dissolved in the NR solution at 0.5 MIC, and the solution exchange was performed by using a gravity-driven perfusion system with the continuous removal of the excess fluid. To avoid changes in junction potentials during solution exchanges, the reference electrode, placed in a petri dish containing internal solution, was connected to the bath solution with an agar bridge. In general, currents were low-pass-filtered using the built-in analogue four-pole Bessel filters of the amplifiers and sampled at 20 kHz. Before analysis, membrane potential traces were digitally filtered (fivepoint boxcar smoothing). Experiments were done at room temperature ranging between 20 and 24 °C. Clampfit 10.7 (Molecular Devices, CA, USA) and Graphpad Prism 7 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA, USA) were used for data display and analysis.

Institutional review board statement

The use of human peripheral lymphocytes for electrophysiology was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Hungarian Medical Research Council (36255-6/2017/ EKU; date 20 September 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from each participant. The investigation conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistics and reproducibility

Sample sizes and numbers of replicates for each analysis are detailed in their respective sections. Data used in these analyses are all available in Supplementary Data.

Data availability

The numerical source data behind graphs displayed in Figs. 3e, 4c, 4f, and 5c, g can be found in datasets Figs. 3e, 4c, f, and 5c, g of the Supplementary Data. The numerical source data behind graphs displayed in Supplementary Figs. 7 and 9 can be found in datasets Supp_Figs. 7 and 9 of the Supplementary Data. All other data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Kaprou, G. D., Bergspica, I., Alexa, E. A., Alvarez-Ordóñez, A. & Prieto, M. Rapid methods for antimicrobial resistance diagnostics. Antibiotics 10, 209 (2021).

Ardal, C. et al. Antibiotic development - economic, regulatory and societal challenges. Nat. Rev. Micro Biol. 18, 267–274 (2020).

Lewis, K. The science of antibiotic discovery. Cell 181, 29–45 (2020).

Ahmed, S. et al. Recent approaches for downplaying antibiotic resistance: molecular mechanisms. Biomed. Res. Int. 2023, 5250040 (2023).

Jangir, P. K. et al. The evolution of colistin resistance increases bacterial resistance to host antimicrobial peptides and virulence. Elife 12, e84395 (2023).

Grézal, G. et al. Plasticity and stereotypic rewiring of the transcriptome upon bacterial evolution of antibiotic resistance. Mol. Biol. Evol. 40, msad020 (2023).

Spohn, R. et al. Integrated evolutionary analysis reveals antimicrobial peptides with limited resistance. Nat. Commun. 10, 4538 (2019).

Dhanda, G., Acharya, Y. & Haldar, J. Antibiotic adjuvants: a versatile approach to combat antibiotic resistance. ACS Omega 8, 10757–10783 (2023).

Melander, R. J. & Melander, C. The challenge of overcoming antibiotic resistance: an adjuvant approach? ACS Infect. Dis. 3, 559–563 (2017).

Sharma, N. et al. Antibiotic adjuvants: a promising approach to combat multidrug resistant bacteria. Curr. Drug Targets 22, 1334–1345 (2021).

Lee, D. Y. D. et al. Magnesium flux modulates ribosomes to increase bacterial survival. Cell 177, 352-+ (2019).

Du Toit, A. Pushing the eject button. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 334–335 (2019).

Bruni, G. N. & Kralj, J. M. Membrane voltage dysregulation driven by metabolic dysfunction underlies bactericidal activity of aminoglycosides. Elife 9, e58706 (2020).

Alteri, C. J., Lindner, J. R., Reiss, D. J., Smith, S. N. & Mobley, H. L. T. The broadly conserved regulator PhoP links pathogen virulence and membrane potential in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol 82, 145–163 (2011).

Miyazawa, N., Hakamada, M. & Mabuchi, M. Antimicrobial mechanisms due to hyperpolarization induced by nanoporous Au. Sci. Rep. -UK 8, 3870 (2018).

Kaim, G. & Dimroth, P. ATP synthesis by F-type ATP synthase is obligatorily dependent on the transmembrane voltage. EMBO J. 18, 4118–4127 (1999).

Dimroth, P., Kaim, G. & Matthey, U. Crucial role of the membrane potential for ATP synthesis by F F ATP synthases. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 51–59 (2000).

Lopatkin, A. J. et al. Bacterial metabolic state more accurately predicts antibiotic lethality than growth rate. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 2109–2117 (2019).

Bhaumik, K. N. et al. Rationally designed foldameric adjuvants enhance antibiotic efficacy promoting membrane hyperpolarization. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 7, 21–33 (2022).

Benarroch, J. M. & Asally, M. The microbiologist’s guide to membrane potential dynamics. Trends Microbiol. 28, 304–314 (2020).

Chen, K., Yu, Q., Liu, Y. & Yin, P. Bacterial hyperpolarization modulated by polyoxometalates for solutions of antibiotic resistance. J. Inorg. Biochem. 220, 111463 (2021).

Lazar, V. et al. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria show widespread collateral sensitivity to antimicrobial peptides. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 718–731 (2018).

Zhou, X. X., Li, W. F. & Pan, Y. J. Functional and structural characterization of apidaecin and its N-terminal and C-terminal fragments. J. Pept. Sci. 14, 697–707 (2008).

Tam, J. P., Wu, C. & Yang, J. L. Membranolytic selectivity of cystine-stabilized cyclic protegrins. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 3289–3300 (2000).

Vernen, F. et al. Characterization of tachyplesin peptides and their cyclized analogues to improve antimicrobial and anticancer properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4184 (2019).

Turner, J., Cho, Y., Dinh, N. N., Waring, A. J. & Lehrer, R. I. Activities of LL-37, a cathelin-associated antimicrobial peptide of human neutrophils. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42, 2206–2214 (1998).

Ladokhin, A. S., Selsted, M. E. & White, S. H. CD spectra of indolicidin antimicrobial peptides suggest turns, not polyproline helix. Biochemistry 38, 12313–12319 (1999).

Loose, C., Jensen, K., Rigoutsos, I. & Stephanopoulos, G. A linguistic model for the rational design of antimicrobial peptides. Nature 443, 867–869 (2006).

Strandberg, E., Wadhwani, P., Tremouilhac, P., Durr, U. H. N. & Ulrich, A. S. Solid-state NMR analysis of the PGLa peptide orientation in DMPC bilayers: Structural fidelity of H-2-labels versus high sensitivity of F-19-NMR. Biophys. J. 90, 1676–1686 (2006).

Porto, W. F. et al. In silico optimization of a guava antimicrobial peptide enables combinatorial exploration for peptide design. Nat. Commun. 9, 1490 (2018).

Avitabile, C., D’Andrea, L. D. & Romanelli, A. Circular Dichroism studies on the interactions of antimicrobial peptides with bacterial cells. Sci. Rep. 4, 4293 (2014).

Park, C. B., Yi, K. S., Matsuzaki, K., Kim, M. S. & Kim, S. C. Structure-activity analysis of buforin II, a histone H2A-derived antimicrobial peptide: The proline hinge is responsible for the cell-penetrating ability of buforin II. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 8245–8250 (2000).

Niidome, T. et al. Structure and property of model peptides of proline/arginine-rich region in bactenecin 5. J. Pept. Res. 51, 337–345 (1998).

Sneideris, T. et al. Targeting nucleic acid phase transitions as a mechanism of action for antimicrobial peptides. Nat. Commun. 14, 7170 (2023).

Chen, B. C. et al. New insights into the antibacterial mechanism of cryptotanshinone, a representative diterpenoid quinone from salvia miltiorrhiza bunge. Front .Microbiol. 12, 647289 (2021).

Chen, E. H. et al. Visualizing the membrane disruption action of antimicrobial peptides by cryo-electron tomography. Nat. Commun. 14, 5464 (2023).

Gong, H. N. et al. How do antimicrobial peptides disrupt the lipopolysaccharide membrane leaflet of Gram-negative bacteria? J. Colloid Interface Sci. 637, 182–192 (2023).

Zhang, Q. Y. et al. Antimicrobial peptides: mechanism of action, activity and clinical potential. Mil. Med. Res. 8, 48 (2021).

Apell, H. J. & Bersch, B. Oxonol-Vi as an optical indicator for membrane-potentials in lipid vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 903, 480–494 (1987).

Konrad, K. R. & Hedrich, R. The use of voltage-sensitive dyes to monitor signal-induced changes in membrane potential-ABA triggered membrane depolarisation in guard cells. Plant J. 55, 161–173 (2008).

Shiver, J. W. & Donovan, J. J. Interactions of diphtheria-toxin with lipid vesicles - determinants of ion channel formation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 903, 48–55 (1987).

Woolley, G. A., Kapral, M. K. & Deber, C. M. Potential-sensitive membrane association of a fluorescent dye. FEBS Lett. 224, 337–342 (1987).

Tamagawa, H. Mathematical expression of membrane potential based on Ling’s adsorption theory is approximately the same as the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation. J. Biol. Phys. 45, 13–30 (2019).

Németh, L. J., Martinek, T. A. & Jójárt, B. Tilted state population of antimicrobial peptide PGLa is coupled to the transmembrane potential. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62, 4963–4969 (2022).

Huang, S. H., Liu, Y. S., Liu, W. Q., Neubauer, P. & Li, J. The nonribosomal peptide valinomycin: from discovery to bioactivity and biosynthesis. Microorganisms 9, 780 (2021).

Su, Z. F., Leitch, J. J., Sek, S. & Lipkowski, J. Ion-pairing mechanism for the valinomycin-mediated transport of potassium ions across phospholipid bilayers. Langmuir 37, 9613–9621 (2021).

Preobraschenski, J. et al. Dual and direction-selective mechanisms of phosphate transport by the vesicular glutamate transporter. Cell Rep. 23, 535–545 (2018).

Chang, T. W. et al. Hydrophobic residues are critical for the helix-forming, hemolytic and bactericidal activities of amphipathic antimicrobial peptide TP4. PLoS ONE 12, e0186442 (2017).

Carrillo-Tripp, M., Saint-Martin, H. & Ortega-Blake, I. A comparative study of the hydration of Na+ and K+ with refined polarizable model potentials. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 7062–7073 (2003).

Dudev, T. & Lim, C. Determinants of K vs Na selectivity in potassium channels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 8092–8101 (2009).

Mita, K. et al. Conductance selectivity of Na across the K channel via Na trapped in a tortuous trajectory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2017168118 (2021).

Leisle, L. et al. Backbone amides are determinants of Cl(-) selectivity in CLC ion channels. Nat. Commun. 13, 7508 (2022).

Huang, W. L., Wang, X. D., Ao, Y. F., Wang, Q. Q. & Wang, D. X. An artificial single molecular channel showing high chloride transport selectivity and pH-responsive conductance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202302198 (2023).

Vasilchenko, A. S. & Rogozhin, E. A. Subinhibitory effects of antimicrobial peptides. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1160 (2019).

Dean, S. N., Bishop, B. M. & van Hoek, M. L. Natural and synthetic cathelicidin peptides with anti-microbial and anti-biofilm activity against Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 11, 114 (2011).

Mataraci, E. & Dosler, S. In vitro activities of antibiotics and antimicrobial cationic peptides alone and in combination against methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 6366–6371 (2012).

Vega, L. A. & Caparon, M. G. Cationic antimicrobial peptides disrupt the Streptococcus pyogenes ExPortal. Mol. Microbiol. 85, 1119–1132 (2012).

Schlievert, P. M. et al. alpha and beta chains of hemoglobin inhibit production of Staphylococcus aureus exotoxins. Biochemistry 46, 14349–14358 (2007).

Zharkova, M. S. et al. Application of antimicrobial peptides of the innate immune system in combination with conventional antibiotics-a novel way to combat antibiotic resistance? Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 9, 128 (2019).

Parvez, F., Alam, J. M., Dohra, H. & Yamazaki, M. Elementary processes of antimicrobial peptide PGLa-induced pore formation in lipid bilayers. Biochem. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1860, 2262–2271 (2018).

Shah, P., Hsiao, F. S. H., Ho, Y. H. & Chen, C. S. The proteome targets of intracellular targeting antimicrobial peptides. Proteomics 16, 1225–1237 (2016).

Xhindoli, D. et al. The human cathelicidin LL-37 A pore-forming antibacterial peptide and host-cell modulator. Biochem. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1858, 546–566 (2016).

Acknowledgements

T.A.M. acknowledges support from NKFI K134754, C.P. from The National Research Development and Innovation Office ‘Élvonal’ Programme KKP 126506 and The National Laboratory of Biotechnology Grant 2022-2.1.1-NL-2022-00008, R.S. from The Janos Bolyai Research Fellowship from the Hungarian Academy of Sciences BO/608/21. Support by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology of Hungary through the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund (TKP2021-EGA-32) is acknowledged. University of Szeged Open Access Fund, Grant ID: 7225.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.N.B. prepared LUV and carried out CD and fluorescence measurements. K.N.B. and G.O. synthesised the necessary materials studied. K.N.B. and A.H. designed experiment, analysed data, and carried out NMR measurements. L.D. performed MIC measurements. A.D. and R.S. carried out flow cytometric membrane polarisation assays. F.Z. measured patch-clamp experiments. A.H., C.P., and T.A.M conceived the study and wrote the manuscript with input from all co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Tobias Goris.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhaumik, K.N., Spohn, R., Dunai, A. et al. Chemically diverse antimicrobial peptides induce hyperpolarization of the E. coli membrane. Commun Biol 7, 1264 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06946-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06946-4