Abstract

Social parasites employ diverse strategies to deceive and infiltrate their hosts in order to benefit from stable resources. Although escape behaviours are considered an important part of these multipronged strategies, little is known about the repertoire of potential escape behaviours and how they facilitate integration into the host colony. Here, we investigated the escape strategies of the parasitic ant cricket Myrmecophilus tetramorii Ichikawa (Orthoptera: Myrmecophilidae) toward its host and non-host ant workers. We identified two escape strategies with distinct trajectory characteristics by clustering analysis; distancing (defined by high-speed straight movement away from ants for emergency avoidance) and dodging (circular escape movement to get behind ants under low-threat conditions). Interestingly, dodging is dominantly elicited over distancing for host species. Furthermore, our simulations proposed that dodging contributes to efficient foraging while avoiding ants. These results demonstrate that switching to a host-adapted escape strategy facilitates integration of this parasitic cricket into ant nests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Host-parasite associations are ubiquitous in the animal kingdom, have independently evolved many times and probably encourage adaptive radiations1. Parasites benefit from rich energy resources and homeostatic environments, but also risk being attacked or eliminated by their hosts. Understanding the mechanisms by which parasites deceive their hosts could lead to insights into the processes producing host-parasite diversification. Parasitic strategies have therefore long attracted researchers to study a variety of interspecific interactions. Research into ant guests (organisms living within ant nests) have been of particular interest and has identified a large number of species across a wide range of invertebrate taxa2,3,4. Although a few species of ant guests have intimate mutualistic relationships with host ants, most ant guests are parasitic. Parasitic ant guests have evolved a variety of strategies for avoiding host detection in different traits to facilitate integration into the host colony2.

Ants recognize nestmates based on the unique blend of cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) shared within the colony, and try to eliminate any organisms considered intruders with deviating signatures5,6. Numerous previous studies have demonstrated that parasitic ant guests adopt various chemical strategies to exploit such nestmate recognition systems to dupe host ants. For example, in chemical mimicry, parasites synthesize their own host odour7; in chemical camouflage, parasites acquire the nest odour8,9; in chemical repellence, parasites secrete substances that the host avoids10. While chemical strategies are an effective way to deceive host ants, maintaining chemical resemblance also has various biological costs, such as the cost of biosynthesis or risks associated with the repeated acquisition of host odour via physical contact. Furthermore, it is considered that, in general, the more sophisticated the chemical strategy, the more limited the range of host species that can be parasitized11,12.

Perhaps because of these disadvantages, not all guests employ chemical strategies. Indeed, recent studies indicate that most ant guests are likely to use alternative strategies in combination with or entirely in place of chemical strategies. In particular, it has been proposed that some ant guests avoid antagonistic interactions with host ants by using behavioural rather than chemical strategies2,4,9,12. In parasitic ant guests that do not rely significantly on chemical strategies, behavioural strategies could be essential to avoid host attacks9,13. Although there is much accumulated knowledge on chemical strategies, behavioural strategies have yet to be well studied in parasitic ant guests. Unlike chemical strategies, behavioural strategies allow ant guests to form non-specific relationships with many host species. Such flexible behavioural adaptations are not only important for allowing guests with poor chemical adaptations to invade the colony, but also may have been influential in the early stages of the evolution of myrmecophilic traits. Elucidating the behavioural strategies by which ant guests integrate into their host colonies will thus provide insights into the mechanisms underlying ant–ant guest diversification.

Escape behaviour is critical for animal survival through avoidance of threats14,15. Animals have multiple escape strategies with qualitatively different characteristics and use them according to the degree of the immediate threat. Generally, those escape strategies involve a trade-off between benefits and costs, such as between speed and accuracy of direction16. The escape behaviour an animal develops through this trade-off depends on its natural history and the ecological niche in which it lives15. Ant guests live in a unique environment with limited space and many potential enemies, including the host ant workers11. Under such high-risk conditions, escape strategies would be critical to increase survival rates and facilitate integrations into ant colonies. However, a lack of quantitative studies makes it unclear what type of escape behaviours ant guests exhibit and how they are used depending on the situation.

Myrmecophilus ant crickets (Orthoptera: Myrmecophilidae) are typical parasitic ant guests. About 60 species have been described across the world17. Myrmecophilus species are generally believed to integrate into their host colony by chemical camouflage18. Despite their use of this deceptive strategy, however, several species of ant crickets have been observed to sustain frequent attacks by their host and to exhibit escape behaviours in response2,11. These observations suggest that chemical camouflage is insufficient to deceive the host ant in these inquiline crickets, and behavioural traits such as specialized escape behaviours might be crucial as an alternative strategy to avoid ant attacks. Although the importance of escape strategies has been discussed2,11,19, no studies have both quantitatively and qualitatively examined the behavioural repertoire of ant crickets and how they apply those strategies to infiltrate the host colony.

In this study, we investigated the escape behaviour of the ant cricket Myrmecophilus tetramorii Ichikawa. This species has high host-specificity to Tetramorium tsushimae Emery and spends nearly all of its life in the nests of this host ant species20. Despite high host-specificity, M. tetramorii do not attempt grooming of the host’s body surface to obtain hydrocarbons and often provoke attacks by host ants. This species is considered a brood predator (cleptoparasites), as it steals food such as dead insects and host ant larvae to feed in the host colony instead of engaging in mouth-to-mouth feeding as observed in other ant crickets with high chemical camouflage ability20. Considering their ecology, they may need to resort to behavioural strategies to integrate into the host colony. We first examining the CHC composition of M. tetramorii to see if they employ chemical mimicry. Subsequently, to identify the repertoire of escape strategies employed by ant crickets and how they adopt strategies in different situations, we focused on their behavioural reactions to the host and non-host ant species. We found that ant crickets have two distinct escape strategies, one of which is specifically adapted to allow coexistence with host ants. Our experimental and theoretical studies propose a new concept of parasitic infiltration in which social parasites facilitate their integration into the host colony by switching escape strategies depending on the situation.

Results

Comparison of cuticular hydrocarbon profiles

Previous studies have reported that M. tetramorii is attacked by its host20. Therefore, this species is not expected to be capable of chemical mimicry to synthesize host odours by its own. However, no previous studies have examined chemical strategy in this particular cricket species. Therefore, we first performed gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis on CHCs of this ant cricket species, its host ant species (T. tsushimae) and four non-host species (P. noda, P. chinensis, P. punctatus, and L. japonicus).

We detected a total of 123 CHCs from the n-hexane fractions of extracts of ant crickets and ant workers (42 compounds from M. tetramorii, 9 compounds from T. tsushimae, 21 compounds from P. punctatus, 24 compounds from L. japonicus, 39 compounds from P. chinensis, and 40 compounds from P. noda, see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 1). CHC profiles were completely different among an ant cricket and five ant species (Fig. 1), and there were significant differences among ant species (Pairwise PERMANOVA with Benjamini-Hochberg corrections, all combinations: P < 0.01, see Supplementary Table 1 for details). In addition, there was no difference in the CHC profile between female and male ant crickets (PERMANOVA, F = 1.2197, R2 = 0.2337, p = 0.50). These results indicate that this cricket species exhibits no endogenous chemical mimicry by synthesizing host CHCs on its own.

Axes are represented by principal coordinates. Different colour plots show different species. Sample sizes are as follows: n = 6 for M. tetramorii, n = 6 for P. noda, n = 8 for L. japonicus, n = 10 for P. punctatus and T. tsushimae. CHC profiles were significantly differed among species (Pairwise PERMANOVA with Benjamini-Hochberg corrections, all combinations: p < 0.01, see Supplementary Table 1 for details).

Identification of two distinct escape behaviours in ant crickets

To investigate the escape strategies adopted by ant crickets and how they are used in different situations, we examined their escape behaviours in the presence of host and non-host ant species. We observed the behavioural interactions of crickets to host ant species and four non-host species. Ant crickets obviously showed moving away behaviour from individuals during encounters with the host and two of four non-host ant species (P. noda and P. chinensis). In contrast, ant crickets showed dissimilar responses to the other two non-host ant species (P. punctatus and L. japonicus). We found that crickets did not display clear escape behaviour toward P. punctatus, to the extent they did not show any antagonistic interactions even when their bodies physically contacted each other. On the other hand, L. japonicus was often aggressive, and crickets were frequently bitten or otherwise attacked before they engaged in escape behaviour (Supplementary Video 1). Based on these observations, three ant species (T. tsushimae, P. noda and P. chinensis) in which we could observe clear escape behaviours were used for the subsequent analysis (Fig. 2a). We successfully obtained a total of 628 cricket escape trajectories (vs. T. tsushimae: 356; vs. P. noda: 197; vs. P. chinensis: 75). To objectively classify escape behaviours, we applied a shape-based clustering method to their trajectories. We revealed that the trajectories could be divided into two major clusters (Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 in Fig. 2b). To determine the validity of the number of clusters, we evaluated three internal clustering validation indexes. Lower values for the Davies-Bouldin Index and higher values for the other two indexes indicate better clustering results. All three indexes indicated that it was most reasonable to classify our data set into two clusters (Fig. 2c).

a Photograph of a Myrmecophilus tetramorii ant cricket, its host ant Tetramorium tsushimae, and non-host ants Pheidole noda and Pachycondyla chinensis. b Clustering dendrogram of cricket trajectories. Isolated clusters are coloured in orange and blue, respectively. The annotated numbers are the number of trajectories included in each cluster. c Values of three cluster validation indexes under different cluster numbers. The solid (blue), dashed (red), and dot-dash (purple) lines indicate the Silhouette coefficient index, Calinski-Harabasz index, and Davies-Bouldin index, respectively. d All cricket trajectories belonging to each cluster. Colours indicate the ant’s approaching directions to the cricket at the event time. e Examples of two individual traces of cricket (red) and ant positions (black) for each of the two clusters. f The cricket’s positions (green dots) and its density contour calculated by the Gaussian kernel density estimation (brown shaded) relative to the ant immediately before and after the event (left, middle). The origin of coordinates indicates the ant’s centroid, and the positive direction along the Y-axis indicates the front of the ant. The histogram (green) and the kernel density estimation (solid brown) of the cricket’s Y-positions immediately after the event (right) are shown.

Next, to identify the behavioural features of the classified trajectories, we summarized them in terms of the approaching direction of the ant to the cricket (Fig. 2d). In all cases, crickets tended to move in the opposite direction to the ant approach at the beginning of the event. The trajectories belonging to Cluster 1 had a relatively straight-line shape, while those in Cluster 2 had a more circular shape. Both types of trajectories caused a significant difference in the positional relationship between ants and crickets after the encounter event. In the case of Cluster 1, crickets moved in the same direction as the travelling ants. In contrast, in Cluster 2 crickets initially began moving in the same direction as the travelling ants, but then moved in the opposite direction in the latter half of their movement due to the arcing trajectory (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Video 2 and 3). As a result, after the encounter, crickets were still located in front of the ants in Cluster 1, whereas they were more likely to be located behind the ants in Cluster 2 (Fig. 2f). These results indicate that ant crickets employ at least two qualitatively different escape strategies. In this study, we named the behaviours classified into Cluster 1 “distancing” because the crickets move straight away from the ants in this strategy, and we named the behaviours classified into Cluster 2 “dodging” because the crickets run away from the ants in a circular movement so that they are eventually behind the ants in this strategy.

Ant crickets prioritize dodging behaviour against host ant species

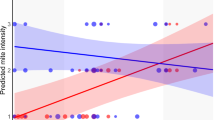

To examine how crickets use distancing and dodging depending on the situation, we focused on the ant species selectivity. We calculated the frequency of the two types of escape behaviours against each ant species (Fig. 3a). We found that dodging behaviour was more frequently elicited than distancing behaviour against host ant species (distancing: 23.0%; dodging: 77.0%, Pearson’s chi-square test for a fit of uniform distribution, p = 2.54 × 10−24). On the other hand, no significant difference was found against non-host ant species (P. noda, distancing: 49.7%, dodging: 50.3%, p = 0.94; P. chinensis, distancing: 42.7%, dodging: 57.3%, p = 0.20). Next, we focused on the relationship between behavioural selectivity and the aggressiveness of ant species. We determined the proportion of ant’s attacking behaviour during the encounter event in all five ant species. We found that host ant species were considerably less aggressive towards crickets than non-host species other than P. punctatus (Supplementary Table 2). This observation indicates that dodging behaviour are preferentially engaged against potential enemies that are less likely to attack. In other words, crickets might use the two different strategies according to a risk of harm. We hypothesized that dodging behaviour is an adaptive strategy to less dangerous situations.

a The ratios and the number of trajectories for each behaviour against the ant species. We performed Pearson’s chi-square test for a fit of uniform distribution. T. tsushimae: p = 2.54 × 10−24; P. noda: p = 0.94; P. chinensis p = 0.20. b The number of trajectories for each behaviour against the ant’s approaching direction at the event time. The trajectories for each ant species were integrated. Pearson’s chi-square test for statistical independence; p = 0.18. c Interindividual distances between the cricket and the ant at the encounter event. Dots represent data for individual events throughout subsequent panels. The centre line and box limits show median and the upper and lower quartiles, respectively. The whiskers show the rest of the distribution except for outliers. Sample sizes are as described in a. Repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test was used to verify differences: T. tsushimae, p = 3.64 × 10−4, Cohen’s d = 0.64; P. noda, p = 0.022, Cohen’s d = 0.33; and P. chinensis, p = 7.42 × 10−3, Cohen’s d = 0.63. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. d A cricket’s average movement speed during each behaviour against the ant species. Repeated measures ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc test: T. tsushimae, p = 1.67 × 10−17, Cohen’s d = 1.77; P. noda, p = 6.43 × 10−14, Cohen’s d = 1.16; P. chinensis, p = 2.26 × 10−4, Cohen’s d = 0.90. ***p < 0.001. e A time series of the interindividual distance between the cricket and the ant during behaviours. Mean distance is shown ±SEM (shaded regions).

To examine particular factors related to the choice of escape behaviour, we first focused on whether the direction in which ants approached crickets affected the frequency of the two escape behaviours. Since crickets detect enemies mainly with their head antenna and tail cerci, it is assumed that the severity and sensitivity of detection of the threat varies depending on the approaching angle of the ants. We found that both dodging and distancing behaviours were observed irrespective of the direction from which ants approached crickets (Fig. 3b, Pearson’s chi-square test for statistical independence, p = 0.18). The biases in behaviour selection by the angle of ant approach were not statistically significant. This result suggests that the ant’s approaching direction is not a determinant of the choice of escape behaviour in crickets. We next compared the interindividual distance at the occurrence of the encounter event between the two behaviours. In general, the shorter the distance between the attacker and the prey, the greater the risk of being attacked. We found that the interindividual distance at the beginning of dodging behaviour tends to be longer than that at distancing behaviour irrespective of ant species (Fig. 3c, Repeated measures ANOVA, T. tsushimae, p = 3.64 × 10−4; P. noda, p = 0.022; P. chinensis, p = 7.42 × 10−3. This result supports that dodging behaviour is selected over distancing when the risk of attack could be lower for crickets.

Next, we compared the locomotion velocity of crickets during escape behaviours. We found that the average speed of crickets during dodging behaviour was slower than that during distancing (Fig. 3d, Repeated measures ANOVA, T. tsushimae, p = 1.67 × 10−17; P. noda, p = 6.43 × 10−14; P. chinensis, p = 2.26 × 10−4). We also examined temporal changes in the ant–cricket interindividual distance. During distancing behaviour, the interindividual distance increased immediately, and the behavioural interaction ended more quickly. During dodging behaviour, on the other hand, the interindividual distance increased relatively slowly, and then reached a plateau level which tended to be maintained until the end of the interaction (Fig. 3e). These results suggest that crickets use distancing behaviour to move quickly away from ants as an emergency measure of avoidance under high-risk conditions. In contrast, under low-risk conditions, they reduce the probability of being attacked by hiding behind ants through dodging behaviour. We concluded that the ant cricket switches escape strategies based on the risk of being attacked.

Dodging behaviour helps ant crickets assimilate into the ant nest

Unlike common escape behaviours, dodging behaviour has the distinctive trait of relocating the cricket to a position behind its potential enemy. Does this unique trait contribute to the integration of crickets into ant nests? To tackle this question, we investigated how dodging behaviour is utilized in the ant colony. We observed an ant cricket locomotion that is already integrated into the host ant colony in laboratory conditions (Fig. 4a). Crickets did not uniformly move around the colony but tended to stay close to certain landmarks, such as debris, areas with wet paper or corners. We found that this incline to maintain proximity to a desirable location is produced by consecutive dodging behaviour (Fig. 4b–d and Supplementary Video 4). This behaviour was observed regardless of the arena shape (Supplementary Fig. 2). Previous studies have reported that M. tetramorii does not engage in begging behaviour toward its host ants as often seen in other ant cricket species. Instead, M. tetramorii feed on solid foods such as ant larvae, dead insects and nest debris on its own20,21. This implies that the behavioural trait of staying in place while avoiding potential enemies is critical for crickets to explore and forage for food or other attractive sources in their host’s nest. The unique trait of dodging behaviour might contribute to effectively staying in place while avoiding a succession of incoming ants. To determine the extent to which dodging behaviour contributes to foraging behaviour in the ant colony, it is necessary to assess what would happen if this behaviour was not taken. However, the difficulty of manipulating cricket behaviour makes it nearly impossible to evaluate this situation experimentally. To overcome this limitation, we next conducted numerical simulations of animal locomotion in a virtual space.

a Heat-map showing the cricket’s position during 30-minute observation in the colony of T. tsushimae overlaid on the snapshot of video images. The colour represents the cumulative time spent at that location on a logarithmic scale. A star, inverted triangle and diamond shapes indicate landmarks where the cricket tended to stay for an extended period. b–d i: Examples of cricket’s trajectory during consecutive dodging behaviour at each landmark. The colour represents the time. ii: Examples of sequential images at a part of the trajectories which are shown in (i). iii: Schematic illustrations of animal moving in the epoch shown in (ii). The coloured and grey arrows indicate cricket’s and ant’s moving respectively.

We built stochastic models which successfully reproduced the characteristics of actual cricket-movement trajectories from our experimental datasets (Fig. 5a). By using this model to simulate exploring and staying behaviour, we estimated the biological significance of the two escape strategies in ant nests. To check the effectiveness of the dodging strategy in the context of these behaviours, we compared the following two cases: (a) distancing only, and (b) dodging only. Particularly in the dodging-only case, the simulation model showed a locomotion trajectory in which the cricket searched closer to the attractive source (top panel in Fig. 5b and Supplementary Video 5). Multiple simulations confirmed that simulated crickets stayed closer to the attractive source for longer periods in the dodging-only case than in the distancing-only case (bottom panel in Fig. 5b), with the total stay time in the attractive area was significantly longer for the dodging-only than the distancing-only case (Fig. 5c, Welch’s t-test, p = 2.22 × 10−5). This result supports that dodging behaviour is an effective strategy for keeping the ant crickets in attractive areas while avoiding numerous potential enemies in the very limited space of the host’s ant nest. Taken together, these results led us to conclude that ant crickets switch their escape strategies to select dodging behaviour, a unique escape strategy elicited by low-threat conditions, and this switch facilitates the integration of ant crickets into host ant nests.

a Examples of observed (black) and simulated (red) trajectories for each behaviour. Each trajectory was aligned and displayed in the direction of the first frame to upward. b Examples of the whole trajectory in a single simulation for each escape strategy (upper panels). Red lines and blue cross marks are the simulated cricket’s trajectories and encounter events with simulated ants, respectively. Heat-maps showing the simulated cricket’s position calculated by 100 simulation runs (bottom panels). The colour represents the cumulative stay time at that location. A circle with black dashed line indicates the attractive area. An arrowhead indicates the initial position of the simulated cricket. c Quantification of the results in b as cumulative stay time in the attractive area. Dots indicate the results from individual simulations. Welch’s t-test; p = 2.22 × 10−5.

Discussion

Behavioural strategies of ant guests for integrating an ant colony may be as important as chemical strategies9, but they have received little attention in the field of myrmecophiles research. In this study, we revealed that the ant cricket M. tetramorii developed the particular behavioural escape strategies in order to live in ant nests while avoiding attacks. First, our GC-MS analysis showed the ant cricket M. tetramorii does not employ chemical mimicry (Fig. 1). Subsequently, in examining the behaviours of ant crickets attempting to escape from ant workers, we identified two qualitatively distinct escape behaviours: one was a linear, quick distancing behaviour, and the other was a relatively slow, arc-shaped dodging behaviour in which the crickets went behind the ants (Fig. 2). Interestingly, we found that dodging behaviour was dominantly elicited against the host ant species. Analysis of quantitative characteristics suggested that ant crickets employ these two behaviours depending on the risk of being attacked (Fig. 3). From observations of crickets living in an ant colony, we found that ant crickets engaged in dodging behaviour to stay in desirable locations (Fig. 4). Furthermore, our behavioural simulations confirmed that dodging behaviour is beneficial for ant crickets attempting to stay near an attractive source in a limited space with many potential enemies (Fig. 5). Since we analysed CHCs of isolated crickets, we can not rule out the possibility that the ant crickets passively receive host ant CHCs, resulting in achieving chemical camouflage. Although the CHC concentrations in the ant crickets appear to be relatively low in our analysis, quantitative comparison between species is useless because of the different number of individuals used for extraction (Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, it is not possible to decide whether the ant crickets resort to chemical insignificance. However, past observations have suggested that this cricket species does not groom an ant body, which leads to active chemical camouflage20. Moerover, the ant crickets are recognized and frequently attacked by host ants2,11. From these observations and our chemical analysis, we believe that the chemical strategy of M. tetramorii is considered poor. Our results show that switching the adaptive strategy of escape from the host species contributes to the survival of the ant guest in its parasitic life, as an alternative or complement to chemical strategies.

Previous studies have demonstrated that many animals engage in multiple escape strategies, ranging from reflex-like actions to actions implying cognitive processes14,15. The use of such escape strategies is known to involve a trade-off between benefits and costs15. For example, two-spotted crickets (Gryllus bimaculatus) exhibit distinct escape behaviours including running and jumping in response to the short airflow detected as a predator approaches22. Jumping is a quick response, allowing the cricket to escape forward at high speed against a threat. Although running is a slow-moving escape action, it allows the cricket to precisely escape in a different direction from the threat. It has been suggested that there is a trade-off between movement speed and flexibility to take subsequent action in selection between jumping or running23. Our results suggest that ant crickets also adopt dodging or distancing depending on a similar trade-off. To evaluate the benefits and costs of each of the escape strategies of ant crickets, it is necessary to consider that these animals coexist with many potential enemies in a small space, which non-ant-associated free-living crickets rarely experience. While distancing behaviour can quickly get crickets away from the approaching ant, such quick movements may alert surrounding potential enemies to the crickets’ presence, triggering an aggressive chase by another ant. Therefore, ant crickets benefit from a slow and precise reaction with dodging, which reduces the probability of being attacked by ants. Considering such a trade-off, it is reasonable for ant crickets to rely on these escape strategies depending on the degree of threat. In fact, our simulation study has shown that dodging behaviour is advantageous for staying in attractive areas while avoiding ants. This result would support the previously reported observation that M. tetramorii do not obtain food through intimate behaviour with host ants despite high host specificity but instead search for food in the host nest on their own20.

From the theoretical viewpoint, escape behaviour represents a strategy to reach a safety zone. Many mathematical models have been developed to explain or predict animal escape strategies24,25. Domenici’s model, focusing on the initial evasive response, suggests prey adjust escape angles based on speed relative to predators, aligning with the distancing behaviour of M. tetramorii crickets. Linear trajectories with large initial escape angles support the model predictions. This type of optimal escape strategy is common in various animals when a predator suddenly strikes a prey15. On the other hand, dodging behaviour, characterized by a curved trajectory, might apply to Howland’s turning gambit which proposing prey can escape to a lateral safety zone if they exhibit greater radial acceleration than predators26. Although this model has not been experimentally tested for a long time, a recent study was the first to validate the turning gambit using moth–bat interaction27. While estimating the radial acceleration of crickets and ants is challenging, dodging behaviour could be regarded as the turning gambit, aiming to reach the safety zone behind ants. To our knowledge, the turning gambit has yet to be reported in predator–prey interactions in terrestrial animals. The turning-gambit-like strategy in ant-crickets interaction may be attributed to the ant’s limited scouting ability, relying on antennation and chemo-sensation for detection nestmate recognition5,6. Due to their narrow sensory exploration range, ants may easily lose track of their prey compared to sight-reliant predators. Although the evolutionary origins of dodging behaviour require careful discussion as described below, we conjecture that the ant’s perceptual characteristics and the special environment in which many potential enemies coexist in a limited space prompted the establishment of such a unique escape strategy in M. tetramorii crickets.

In this study, we concluded that M. tetramorii crickets switch between two distinct escape strategies depending on the situation, resulting in behavioural preferences specific to host and non-host ant species. To consider the factors underlying these behavioural preferences, we first need to understand how ant crickets detect potential enemies in a dark nest. One of the possible candidates is air flow sensing. The cerci, a pair of abdominal appendages containing sensory hairs, is vital in many Gryllidea species for detecting a predator as an air current28,29. This organ is conserved in ant crickets and is well developed relative to their body size. This sensory organ allows ant crickets to detect the proximity of ants based on the intensity of air motion even in the dark nest. However, interestingly, we found that ant crickets do not elicit obvious escape behaviour against P. punctatus and L. japonicus. Since L. japonicus has a larger body and tends to move faster than P. noda, ant crickets should be able to detect the movements of L. japonicus by the cerci and exhibit escape behaviour. In contrast to this expectation, ant crickets showed little escape behaviour prior to physical contact with L. japonicus workers, leading to an attack and being killed in some cases. This observation supports the idea that the decision-making leading to escape behaviour is not solely dictated by the magnitude of stimuli reaching the sensory organs, but this is a multi-layered process underpinned by some factors that make crickets aware of the presence of a potential enemy.

What factors could lead to the emergence of such diversification in escape behaviour? One interesting scenario is that ant crickets change their threshold for behavioural selection depending on the ant species or the perceived risk. Our results indicate that host ants induce a high frequency of dodging behaviour in ant crickets, suggesting that the crickets perceive host ants as less threatening than non-host ants. One possibility is that crickets use their auditory system to detect the identity of ants or the degree of threat. It is known that many ant species can produce vibroacoustic signals to convey information among nestmates, and their temporal and spectral patterns vary according to species and behavioural contexts30,31. There is even a social parasite that takes advantage of acoustic signals to infiltrate ant colonies32. However, a previous study demonstrated that the tibial tympana, which is known as the auditory organ in the Ensifera clade, is secondarily lost in Mrymecophilidae species33. Given this, ant crickets may have difficulty in hearing sounds. Thus, vibroacoustic signals are unlikely to play a role in detecting ants. Another, stronger possibility is the recognition of ant species by chemo-sensation to adjust the threshold for behavioural selection. Our GC-MS analysis showed that each ant species used in the behavioural experiments has significantly different CHC compositions (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 1). Therefore, ant crickets may be able to sufficiently recognize ant species by chemical profiles of ants. Antipredator behaviour in a wide range of animal taxa, including non-parasitic free-living crickets, has been reported to be modulated by detecting the predator type via chemical cues34,35,36,37,38. In a similar manner, ant crickets may sense volatile and non-volatile substances specific to ant species (e.g., nest volatiles39, alarm pheromones40, and non-volatiles that limit aphid dispersal41) and adjust their “safety margin” for behaviour selection. For example, the smell of the host/non-host colony may desensitize/hypersensitize crickets to ants, making the dodging/distancing behaviour dominant, respectively. In contrast, the odours of L. japonicus and P. punctatus might considerably elevate the sensory threshold for recognizing the threat and prevent the crickets from engaging in appropriate escape behaviour. Alternatively, it is possible that the odours of L. japonicus and P. punctatus could significantly differ from that of other species, ant crickets do not recognize these species as a potential enemy.

The questions of which chemoreceptors detect the identity of ants and at what neural level this regulation occurs are fascinating ones, not only neurologically but also from an evolutionary ecological perspective. This is because these genetic and neural components provide the molecular basis for host specificity, which is a fundamental vantage point for understanding the ecological and evolutionary dynamics of symbionts. The factors that define their host specificity are not well understood yet, but since the host specificity and phylogenetic lineages of ant crickets are so well matched, it is presumed that genetic background is behind them42,43. Therefore, genome-wide exploratory studies of chemo-sensation receptors to identify ant-specific components involved in their physiological function would help to untangle the evolutionary roots of host specificity.

Myrmecophilic traits are found in a variety of arthropods but have repeatedly evolved in rove beetles44. In these species, the relatively small body size and defensive morphologies, such as the tergal gland, may have been preadaptations that facilitated the evolution of myrmecophily45. We speculate that ant-associated habits may have evolved from free-living species to strict myrmecophiles via facultative traits. In the order Orthoptera, which does not commonly have myrmecophily-prone profiles, behavioural strategies have more versatility to adjust flexibly to the traits of the different host species than chemical strategies, and these characteristics may be particularly important in the early phase of myrmecophily evolution. Dodging behaviour does not appear effective against sight-reliant predators; it may be a fine-tuned trait for symbiosis with ants. A prior study described a behaviour of Myrmecophila manni for avoiding ants that consists of moving in a circular trajectory similar to dodging behaviour19. This observation suggests that dodging-like behaviour emerged as a common adaptation to ant nests in Myrmecophilus crickets. This behavioural adaptation may have made Mrymecophilidae the only ant-guest family in the Orthoptera. But importantly, the possibility that dodging behaviour originally evolved solely as an ant-associative adaptation is left open. It remains possible that the behavioural trait of dodging arose as an adaptation to living under soil and humus, and subsequently was secondarily converted to an escape strategy for effectively invading ant nests. A further comprehensive study of escaping behaviours, including in Gryllotalpidae, a related species living in similar habitats of Myrmecophilidae33,46, would shed light on the evolutional trajectory of myrmecophily in the Orthoptera.

Materials and methods

Animals

Ant crickets (M. tetramorii), their host ant workers (T. tsushimae Emery) and non-host ant workers (Pheidole noda Smith; Pachycondyla chinensis Emery; Pristomyrmex punctatus Smith; Lasius japonicus Santschi) were collected at the Higashiyama Campus of Nagoya University (35°09′15.3′′N 136°58′15.8′′E) in Japan from April 2021 to June 2023. Ant crickets were collected from 3 different nests of T. tsushimae. All collected ant crickets seemed to be adult and showed no significant variation in body size between individuals. We selected four non-host ant species because of its similarity in body size and its sympatric habitat with the host species. After collection, animals were reared separately by species in Falcon tubes with moistened Kimwipes (ant crickets : two females; ants : 20-50 ants in each tube) at 22°C in 40% to 60% relative humidity under a 12-h light/dark (LD) cycle until CHC extraction or behaviour recordings. Ant cricket species were identified by sequencing the cytochrome b gene described in a previous study and comparing them to the GenBank sequence (GenBank: AB443897)42. Ant species were identified with reference to the Encyclopedia of Japanese Ants47.

CHC extraction

Individual ant crickets and ant workers were freeze-killed for about 10 min at −25 °C and then incubated in 6 mL glass vial containing 500 μL n-hexane (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) for 2 min to extract CHC. For two ant species (T. tsushimae and P. noda), we pooled 5 individuals to extract sufficient amounts of CHCs. We prepared 6–10 crude extract samples for each species (M. tetramorii and P. noda: 6 samples, L. japonicus: 8 samples, Others: 10 samples). Note that individual ant crickets used for CHC extraction were reared in isolation from the host ants for at least 10 days to remove the effects of chemicals derived from the ants. The extracts were transferred to fresh 1.5 mL glass vial and stored at −25 °C until the subsequent procedure. For each species, 500 μL of the crude extract was chromatographed on 0.5 g silica gel (C-200, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) in a column (6 mm inner diameter). CHCs were eluted with 2 mL n-hexane, and then the CHC fraction was concentrated without desiccation using a rotary evaporator to obtain a 10 μL fraction (equating to 0.1 or 0.5 individuals/μL). The CHC fraction was preserved at −25 °C.

GC-MS analysis

To determine the chemical profile of the CHC fractions, GC-MS analysis was performed using an Agilent Mass Spectrometer 5975C (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in conjunction with an Agilent GC 7890 A (Agilent Technologies). A sample volume of 2 μL was injected in splitless mode using an Agilent autosampler 7693 (Agilent Technologies) into a DB-5MS column (30 m, 0.25 mm inner diameter, 0.25 μm film thickness, Agilent Technologies) with nitrogen as the carrier gas (1.2 mL/min constant flow rate). The column temperature was held at 60 °C for 1 min, increased to 320 °C at 10 °C/min, and held at 320 °C for 10 min. The injection port was constantly held at 320°C. MS data acquisition conditions were as follows: 35 μA ionization current, 70 eV ionization energy, 1741.18 V accelerating voltage, and a scan range from 33 to 400 m/z. Both the gas chromatographic system and the mass spectrometer were controlled using Enhanced ChemStation software (v. E.02.01.1177, Agilent Technologies). Data interpretation was facilitated by the Openchrom software Lablicate Edition ver. 1.5.048. Candidate compounds were predicted from the Mass Bank database (NIST format, release version 2022.06)49. n-Alkanes were identified according to Kovats indices and mass spectra, in comparison with authentic standards (C7-C40 Saturated Alkane Mixture, Sigma-Aldrich Japan, Tokyo, Japan), and the other CHCs were estimated based on Kovats indices and mass spectra. Methyl branch positions of mono-, di-, tri-, and tetramethylalkanes were determined from characteristic mass fragments of their respective mass spectra50. The positions of double bonds were not determined.

Behaviour recordings

Behaviour recordings were performed during a Zeitgeber time (ZT) of 0–12 at 22 °C and 40–60% relative humidity. For the single animal experiments, one ant cricket female was transferred into a chamber (35 mm petri dish; Corning) and allowed to acclimate for 30 min. Then one ant worker was transferred into the chamber to meet an ant cricket female. The following numbers of individual crickets were deployed in behaviour observations (for T. tsushimae; n = 15, P. noda; n = 7, P. chinensis; n = 8, P. punctatus; n = 8, L. japonicus; n = 8). When observing interactions between crickets and host workers, individuals collected from the same nest were used. Note that some crickets were used in the experiment more than once if the tested ant species were different. For the behaviour recording of ant cricket in an ant colony, one ant cricket was kept in a plastic container (82 × 52 × 19 mm) with 20 host ants for 5 days prior to the video recording under laboratory conditions. Wet Kimwipes were added to plastic containers to supply moisture and 200 mM sucrose solution was provided as food. We recorded videos in all experiments for 30 min by a CMOS camera (DFK 33UP1300; The Imaging Source Asia Co.) equipped with a zoom lens (M0814-MP2; CBC Optics Co.).

Animal tracking and behaviour extraction

Animal positions and their body parts were tracked by DeepLabCut (DLC; version 2.2.0.2)51. Due to our limited computational resources, we downsampled the raw video data to 10 fps to reduce the analysis time. We tracked the animal positions for all video frames. A custom Python script was used to calculate the interindividual distance between a cricket and an ant in each frame. Then we extracted continuous frames in which the interindividual distance was less than 10 mm as candidates for video sequences containing encounter events. We reviewed all extracted video sequences and removed videos that did not record a cricket–ant contact. For all remaining videos, tracking accuracy was ensured by manually checking for mismatches or missing tracking points. The start and end frames of the cricket’s escape behaviour were manually defined based on the positional relationship between animals and the changes in the cricket’s movement. Finally, we tracked both cricket and ant body parts (heads and tails) on the frames of extracted videos using DLC.

Behaviour clustering

To quantitatively classify the behaviours of crickets, we utilized Ward’s method for hierarchical clustering52 based on the similarity of animal trajectory. In this study, we used a shape-based similarity measure called the Angular Metric for Shape Similarity (AMSS)53. This procedure treats time-series data as vector sequences and compares the shapes by a variant of cosine similarity. Briefly, first, a trajectory represented by a time series of XY values was transformed into a vector sequence. To classify behaviours in the shape of trajectories, rather than in the moving direction, each vector was aligned so that the direction of the first element was the same. Then, we calculated AMSS for every pair of aligned vectors, including against all ant species by a custom-made Python script. We performed the clustering analysis using the Python SciPy package.

Since clustering is an exploratory type of data analysis, the results must be subjectively interpreted in line with the purpose of the study. Therefore, the number of clusters had to be determined from an ethological perspective. To quantitatively verify and utilize this approach for interpretation, we evaluated three internal clustering validation indexes — the Silhouette, Calinski-Harabasz, and Davies-Bouldin indexes. These indexes were calculated using the Python scikit-learn package.

Simulation

By constructing multiple stochastic models of animal behaviours, we simulated the two escape behaviours of ant crickets defined in this study, and a free walking behaviour for both crickets and ants in a two-dimensional space. For simplicity, the animals were modelled as a point with no length. The simulation was run in a virtual 80 × 80 mm space on a Cartesian coordinate system where the origin is the centre of space. The zero direction was defined as the positive direction of the X-axis. The unit discrete time interval was 0.1 s, and the total simulated time length was 10 min (6000 steps) for each simulation.

The position of the simulated animal at time t+1, \(({x}_{t+1},{y}_{t+1})\) is updated from the position at time t, \(({x}_{t},{y}_{t})\) by obeying the following equations:

where θt and dt are a moving direction and a travel distance at time t, respectively, and φt is a turning bias described in detail later. The initial values of the parameters are listed in Table 1. In the case that an animal goes out of the virtual space during the simulation, it will be returned into the space by reflection.

From the observation of cricket positions before the encounter event (Fig. 2f), we set simulated crickets to initiate one of two escape behaviours when they entered less than 4 mm and ±45° in front of simulated ants. To formulate stochastic models of a cricket’s escape behaviours, we introduced probability densities of \(\Delta {\theta }_{t}\) and dt in the form of

and

where λ indicates a variable taking 0 or 1 to switch between the escape behaviours, and te is the time when the current encounter event occurred. The duration of each behaviour was determined by its probability density, which was calculated from the experimental data. That is, within that determined time, \({\Delta \theta }_{t}\) and \({d}_{t}\) of the simulated cricket were generated according to the above equations. The differential of direction at the time of the encounter event, \(\Delta {\theta }_{{t}_{e}}\), was uniformly randomized within [−20°, 20°] each time. The turning bias, \({\varphi }_{{t}_{e}}\) was set to an appropriate value so that \({\theta }_{{t}_{e}}-\Delta {\theta }_{{t}_{e}}\) was in the opposite direction from the encountered ant. The subsequent \({\varphi }_{t}\) was set to be zero during the behaviour. This modelled the behaviour of a cricket escaping in the opposite direction from the ants. The conditional probability density functions in the above equations, \(P\left(\Delta {\theta }_{t}\,,|,\mathop{\sum }_{i={t}_{e}}^{t-1}{\Delta \theta }_{i}\right)\) and \(P({d}_{t}|{\Delta \theta }_{t})\), for each escape behaviour are represented by an empirical density function of our experimental data. This means that \(\Delta {\theta }_{t}\) and dt are randomly resampled from a normalized cross-section of the two-dimensional empirical cumulative distribution function of the data at the occurrence of the values \(\mathop{\sum }_{i={t}_{e}}^{t-1}{\Delta \theta }_{i}\) and \({\Delta \theta }_{t}\), respectively. Because we found that \(\Delta {\theta }_{t}\) in the observed trajectory is strongly correlated with the cumulative difference in the moving direction, rather than the differential of direction at t-1, \(\Delta {\theta }_{t-1}\), we used the conditional probability that obeys the cumulative directional change mentioned above. This allowed us to generate a trajectory that closely resembled the actual observed trajectories (Fig. 5a).

In this simulation, we modelled animal locomotion as free walking at all times except when a cricket was exhibiting escape behaviour, as described above. We introduced probability densities of \(\Delta {\theta }_{t}\) and \({d}_{t}\) for free walking in the form of

and

In order to obtain the conditional probability density functions, \({P}_{{walking}}\left(\Delta {\theta }_{t}|\Delta {\theta }_{t-1}\right)\) and \({P}_{{walking}}({d}_{t}|{\Delta \theta }_{t})\), we performed additional experiments to analyse the walking behaviour of both crickets and ants (T. tsushimae). To observe free walking itself in the absence of interactions between animals, a single animal was placed in a petri dish (85 mm) and footage captured in AVI format (720 × 480 image size at 30 fps). We took a total of six and eight hours of video from 7 crickets and 9 ants, respectively. The positions of the animals were tracked in the same way as described above. We extracted trajectories of continuous movement that passed through the centre of the petri dish in order to avoid contaminating the data with an artificial bias caused by the shape of the petri dish.

To mimic a crowded situation, such as the inside of an ant nest, a total of 30 simulated ants were randomly placed in the virtual space. For simplicity, we did not consider any interactions between the animals, except for the cricket–ant encounter event described above. By simulating under these conditions, we can eliminate various factors which would otherwise exert complex influences on the behaviour of the animals in the actual environment, and directly assess only the effect of the difference between the two escape strategies. In this study, we focused on the behaviour of crickets attempting to stay in a particular place, as occasionally observed during foraging behaviour, for example. To model this, we introduced a continuous turning bias during the free walking in the form of

where \({\phi }_{t}\) is the direction of origin relative to the animal’s moving direction at time t. This is equivalent to placing a pseudo-attractive source at the origin of the simulated space. We defined the circular area with a radius of 5 mm from the origin as the attractive area and calculated the cricket’s total stay time in that area. For the cricket and 2 randomly selected ants out of the 30 simulated ants, we adopted the above turning bias, and for the other ants the turning bias was always zero.

We carried out numerical simulations under the following two conditions and compared the performances. (a) Distancing only (λ = 0): the simulated cricket always adopts a “distancing” strategy after the encounter event. (b) Dodging only (λ = 1): the cricket always adopts a “dodging” strategy after the encounter event.

Quantification of ant aggression

The following two patterns were defined as attacking behaviour of ants: (1) ants chase crickets without physical contact accompanied by mandibular spreading; (2) ants approach crickets with mandibular spreading and make physical contact with crickets.

Statistics and reproducibility

The sample size for each experiment is provided in the respective sections of Materials and Methods, and these were determined based on to ensure adequate statistical power and the number of animals we could collect from the field. Statistical results for each experiment can be found in the main text and figure legends.

For CHC profile analysis, we selected 42, 9, 21, 24, 39, and 40 relevant CHC peaks from M. tetramorii, T. tsushimae, P. punctatus, L. japonicus, P. chinensis, and P. noda, respectively, which were detected commonly in all extraction samples for each species. The CHC compositional data (i.e., percentages of CHC peak areas per sample) were analysed using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and pairwise permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) based on 999 permutations with Bray-Curtis similarities. For comparison of CHC profiles between male and female ant crickets, we performed PERMANOVA based on 999 permutations with Bray–Curtis similarities. All statistical analyses for CHCs were performed using R software ver. 4.4.054 with ‘vegan’ (Github, https://github.com/vegandevs/vegan) and ‘pairwiseAdonis’ (Github, https://github.com/pmartinezarbizu/pairwiseAdonis) packages.

The number of experimental replicates in Fig. 3 defined as behavioural observations conducted under the same conditions are as follows (vs T. tsushimae; 19, vs P. noda; 9, vs P. chinensis; 12, vs P. punctatus; 16, vs L. japonicus; 9). To calculate p-values and validate statistical significance in the behavioural and simulation analyses, we first conducted repeated measures ANOVA, including random effects for animals for the pairwise comparisons of behavioural data shown in Fig. 3c, d, to exclude the problem of pseudoreplication. Then we applied a Bonferroni post-hoc test at the appropriate significance level. Pearson’s chi-square test for uniformity and independence was used to validate differences in behavioural frequency in each ant species (Fig. 3a) and against the ant approaching angle (Fig. 3b), respectively. The use of the chi-square test for our data met Cochrane’s criteria. For comparisons using the simulation data, we performed Welch’s t-tests. To check the substantive significance of the observed difference between the two behavioural strategies, we calculated Cohen’s d as effect size. All effect sizes are described in the figure legends. All statistical analysis were performed using the Python and R lme4 libraries.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data of this study are available on FigShare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26940937.v1)55.

Code availability

The codes of this study are available on FigShare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26940937.v1)55.

References

Weinstein, S. B. & Kuris, A. M. Independent origins of parasitism in Animalia. Biol. Lett. 12, 1–5 (2016).

Kronauer, D. J. C. & Pierce, N. E. Myrmecophiles. Curr. Biol. 21, 208–209 (2011).

Lachaud, J. P., Lenoir, A. & Witte, V. Ants and their parasites. Psyche 2012, 1–5 (2012).

Parmentier, T. Guests of Social Insects. Encycl. Soc. Insects 1–15 (2020).

Sturgis, S. J. & Gordon, D. M. Nestmate recognition in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): A review. Myrmecological N. 16, 101–110 (2012).

Ozaki, M., Wada-katsumata, A. & Fujikawa, K. Ant Nestmate and Non-Nestmate Discrimination by a Chemosensory Sensillum. Science 309, 311–315 (2005).

Lenoir, A., D’Ettorre, P., Errard, C. & Hefetz, A. Chemical Ecology and Social Parasitism in Ants. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 46, 573–599 (2001).

Akino, T. Chemical strategies to deal with ants: a review of mimicry, camouflage, propaganda, and phytomimesis by ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and other arthropods. Myrmecol. N. 11, 173–181 (2008).

Parmentier, T., De Laender, F., Wenseleers, T. & Bonte, D. Prudent behavior rather than chemical deception enables a parasite to exploit its ant host. Behav. Ecol. 29, 1225–1233 (2018).

Stoeffler, M., Maier, T. S., Tolasch, T. & Steidle, J. L. M. Foreign-language skills in rove-beetles? Evidence for chemical mimicry of ant alarm pheromones in myrmecophilous Pella beetles (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 33, 1382–1392 (2007).

Komatsu, T., Maruyama, M. & Itino, T. Behavioral differences between two ant cricket species in nansei islands: Host-specialist versus host-generalist. Insectes Soc. 56, 389–396 (2009).

von Beeren, C. et al. Chemical and behavioral integration of army ant-associated rove beetles - a comparison between specialists and generalists. Front. Zool. 15, 1–15 (2018).

Witte, V., Foitzik, S., Hashim, R., Maschwitz, U. & Schulz, S. Fine tuning of social integration by two myrmecophiles of the ponerine army ant, Leptogenys distinguenda. J. Chem. Ecol. 35, 355–367 (2009).

Card, G. M. Escape behaviors in insects. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 22, 180–186 (2012).

Evans, D. A., Stempel, A. V., Vale, R. & Branco, T. Cognitive Control of Escape Behaviour. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 334–348 (2019).

Catania, K. C. Tentacled snakes turn C-starts to their advantage and predict future prey behavior. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 11183–11187 (2009).

Maruyama, M. Four New Species of Myrmecophilus (Orthoptera, Myrmecophilidae) from Japan. Bull. Natl. Sci. Mus., Tokyo, Ser. A 30, 37–44 (2004).

Akino, T., Mochizuki, R., Morimoto, M. & Yamaoka, R. Chemical Camouflage of Myrmecophilous Cricket Myrmecophilus sp. to be Integrated with Several Ant Species. Jpn. J. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 40, 39–46 (1996).

Henderson, G. & Akre, R. D. Biology of the Myrmecophilous Cricket, Myrmecophila manni (Orthoptera: Gryllidae). J. Kans. Entomol. Soc. 59, 454–467 (1986).

Komatsu, T., Maruyama, M. & Itino, T. Nonintegrated host association of Myrmecophilus tetramorii, a specialist myrmecophilous ant cricket (Orthoptera: Myrmecophilidae). Psyche 2013, 1–5 (2013).

Komatsu, T., Maruyama, M., Hattori, M. & Itino, T. Morphological characteristics reflect food sources and degree of host ant specificity in four Myrmecophilus crickets. Insectes Soc. 65, 47–57 (2018).

Tauber, E. & Camhi, J. M. The wind-evoked escape behavior of the cricket Gryllus bimaculatus: Integration of behavioral elements. J. Exp. Biol. 198, 1895–1907 (1995).

Sato, N., Shidara, H. & Ogawa, H. Trade-off between motor performance and behavioural flexibility in the action selection of cricket escape behaviour. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–13 (2019).

Domenici, P., Blagburn, J. M. & Bacon, J. P. Animal escapology I: Theoretical issues and emerging trends in escape trajectories. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 2463–2473 (2011).

Domenici, P., Blagburn, J. M. & Bacon, J. P. Animal escapology II: Escape trajectory case studies. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 2474–2494 (2011).

Howland, H. C. Optimal strategies for predator avoidance: The relative importance of speed and manoeuvrability. J. Theor. Biol. 47, 333–350 (1974).

Corcoran, A. J. & Conner, W. E. How moths escape bats: Predicting outcomes of predator-prey interactions. J. Exp. Biol. 219, 2704–2715 (2016).

Gottingen, U. Wind-evoked escape running of the cricket. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 189–214 (1992).

Landolfa, M. A. & Jacobs, G. A. Direction sensitivity of the filiform hair population of the cricket cereal system. J. Comp. Physiol. A 177, 759–766 (1995).

Ferreira, R. S., Poteaux, C., Delabie, J. H. C., Fresneau, D. & Rybak, F. Stridulations reveal cryptic speciation in neotropical sympatric ants. PLoS One 5, e15363 (2010).

Masoni, A. et al. Ants modulate stridulatory signals depending on the behavioural context. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–12 (2021).

Barbero, F., Thomas, J. A., Bonelli, S., Balletto, E. & Schönrogge, K. Queen ants make distinctive sounds that are mimicked by a butterfly social parasite. Science 323, 782–785 (2009).

Song, H. et al. Phylogenomic analysis sheds light on the evolutionary pathways towards acoustic communication in Orthoptera. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–16 (2020).

Lima, S. L. & Dill, L. M. Behavioral decisions made under the risk of predation: a review and prospectus. Can. J. Zool. 68, 619–640 (1990).

Kannan, K., Galizia, C. G. & Nouvian, M. Olfactory Strategies in the Defensive Behaviour of Insects. Insects 13, 1–20 (2022).

Binz, H., Bucher, R., Entling, M. H. & Menzel, F. Knowing the risk: Crickets distinguish between spider predators of different size and commonness. Ethology 120, 99–110 (2014).

Hoefler, C. D., Durso, L. C. & McIntyre, K. D. Chemical-Mediated Predator Avoidance in the European House Cricket (Acheta domesticus) is Modulated by Predator Diet. Ethology 118, 431–437 (2012).

Jędrzejewski, W., Rychlik, L., Jędrzejewska, B., Jedrzejewski, W. & Jedrzejewska, B. Responses of Bank Voles to Odours of Seven Species of Predators: Experimental Data and Their Relevance to Natural Predator-Vole Relationships. Oikos 68, 251 (1993).

Katzav-Gozansky, T., Boulay, R., Ionescu-Hirsh, A. & Hefetz, A. Nest volatiles as modulators of nestmate recognition in the ant Camponotus fellah. J. Insect Physiol. 54, 378–385 (2008).

Mizunami, M., Yamagata, N. & Nishino, H. Alarm pheromone processing in the ant brain: An evolutionary perspective. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 4, 1–9 (2010).

Oliver, T. H., Mashanova, A., Leather, S. R., Cook, J. M. & Jansen, V. A. A. Ant semiochemicals limit apterous aphid dispersal. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 274, 3127–3131 (2007).

Komatsu, T., Maruyama, M., Ueda, S. & Itino, T. mtDNA phylogeny of japanese ant crickets (Orthoptera: Myrmecophilidae): Diversification in host specificity and habitat use. Sociobiology 52, 553–565 (2008).

Komatsu, T., Maruyama, M. & Itino, T. Differences in host specificity and behavior of two ant cricket species (Orthoptera: Myrmecophilidae) in Honshu, Japan. J. Entomol. Sci. 45, 227–238 (2010).

Maruyama, M. & Parker, J. Deep-Time Convergence in Rove Beetle Symbionts of Army Ants. Curr. Biol. 27, 920–926 (2017).

Parker, J. Myrmecophily in beetles (Coleoptera): Evolutionary patterns and biological mechanisms. Myrmecological N. 22, 65–108 (2016).

Sanno, R. et al. Comparative Analysis of Mitochondrial Genomes in Gryllidea (Insecta: Orthoptera): Implications for Adaptive Evolution in Ant-Loving Crickets. Genome Biol. Evol. 13, 1–8 (2021).

Terayama, M., Kubota, S. & Eguchi, K. Encyclopedia of Japanese Ants Asakura Shoten, Tokyo, 278p (2014).

Wenig, P. & Odermatt, J. OpenChrom: A cross-platform open source software for the mass spectrometric analysis of chromatographic data. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 405 (2010).

Horai, H. et al. MassBank: A public repository for sharing mass spectral data for life sciences. J. Mass Spectrom. 45, 703–714 (2010).

Nelson, D. R., Sukkestad, D. R. & Zaylskie, R. G. Mass spectra of methyl-branched hydrocarbons from eggs of the tobacco hornworm. J. Lipid Res. 13, 413–421 (1972).

Mathis, A. et al. DeepLabCut: markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1281–1289 (2018).

Ward, J. H. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 58, 236–244 (1963).

Nakamura, T., Taki, K., Nomiya, H., Seki, K. & Uehara, K. A shape-based similarity measure for time series data with ensemble learning. Pattern Anal. Appl. 16, 535–548 (2013).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Core Team, 2016).

Tanaka, R. Mitaka, Y. Suzuki, Y. Data and Code on Escape behavior of ant cricket (figshare, 2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Naoto Idogawa for the identification of ant species; Dr. Nozomi Nishiumi, Dr. Kazushi Tsutsui and Dr. Matthew Paul Su for discussion. This study was supported by MEXT KAKENHI (grant no. JP21K15137 and grant no. JP22H05650 for R.T.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.T.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft; Y.M.; Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft; D.T.: Validation, Writing – review & editing; M.P.S: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing; A.K.: Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing; Y.S: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Thomas Parmentier and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Luke Grinham and David Favero.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, R., Mitaka, Y., Takemoto, D. et al. Switching escape strategies in the parasitic ant cricket Myrmecophilus tetramorii. Commun Biol 7, 1714 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07368-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07368-y