Abstract

Root-knot nematodes (RKNs) of the genus Meloidogyne pose the most significant threats to global food security due to their destructive nature as plant-parasitic nematodes. Although significant attention has been devoted to investigating the gene transcription profiling of RKNs, our understanding of the translational landscape of RKNs remains limited. In this study, we elucidated the translational landscape of Meloidogyne incognita through the integration of translatome, transcriptome and quantitative proteome analyses. Our findings revealed numerous previously unannotated translation events and refined the genome annotation. By investigating the genome-wide translational dynamics of M. incognita during parasitism, we revealed that the genes of M. incognita undergo parasitic stage-specific regulation at the translational level. Interestingly, we identified 470 micropeptides (containing fewer than 100 amino acids) with the potential to function as effectors. Additionally, we observed that the effector-coding genes in M. incognita exhibit higher translation efficiency (TE). Further analysis suggests that M. incognita has the potential to regulate the TE of effector-coding genes without simultaneous alterations in their transcript abundance, facilitating effector synthesis. Collectively, our study provides comprehensive datasets and explores the genome-wide translational landscape of M. incognita, shedding light on the contributions of translational regulation during parasitism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The assessment of transcript abundance has long served as the predominant method for monitoring changes in gene expression levels1,2,3. However, because of most biological processes are ultimately carried out by proteins, the accuracy of transcript abundance as a predictor of protein abundance has been a topic of debate4, and increasing studies have illustrated that translational regulation can result in a low correlation between transcription levels and protein levels5,6,7. Acting as a pivotal process in decoding genetic information into functional proteins, translation is meticulously regulated at multiple levels8,9. These intricate regulatory processes ensure precise timing, accuracy, and efficiency in protein synthesis, ultimately determining the function and fate of the resulting proteins within the organism10. Additionally, translational regulation has been recognized as crucial in swiftly and reversibly modifying gene expression in response to developmental and environmental cues11.

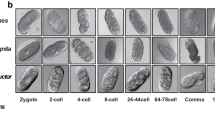

Polyphagous root-knot nematodes (RKNs, Meloidogyne spp.) are the most damaging soil-borne pests that cause significant yield losses in agriculture and pose a threat to global food security12,13. After hatching from the eggs of RKNs, the second-stage juveniles (J2s) use a hollow protrusive stylet to penetrate plant roots, enter the vascular cylinder and become sedentary, where they establish feeding sites and develop into third-stage (J3), fourth-stage (J4) and adult nematodes14,15,16. The successful parasitism of RKNs involves complex gene expression regulation, prompting extensive research into their parasitism mechanisms, particularly at the transcriptional level17,18,19. For instance, comparative transcriptome analysis has provided important insights into the expression regulation of genes involved in the parasitism process20,21, identifying a series of effectors that participate in suppressing host defense, such as MiSGCR115, MiISE622 and Mi-gst-123. Meanwhile, advancements of mass spectrometry (MS) have enabled precise profiling of protein content. For instance, proteomic analysis has been used to refine the genome annotation of RKNs24 and identified abundant proteins secreted by Meloidogyne incognita25,26. However, it is worth noting that proteomic analysis has inherent limitations, often capable of detecting only a subset of highly expressed proteins7,27. Furthermore, proteomics data primarily offers insights into the global protein abundance rather than translation dynamics. Significantly, accumulating evidence have emphasized the importance of translational regulation for metabolism, regulation, and virulence in pathogens28,29,30. Therefore, while transcriptome and proteome analysis have yielded valuable insights into the parasitism mechanisms of RKNs, they offer only a partial perspective, neglecting the crucial aspect of translational regulation.

Ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq), a recently developed technology, provides an innovative strategy to monitor genome-wide translational dynamics at nucleotide resolution by sequencing ribosome-protected RNA fragments (RPFs)31. By capturing RNAs bound to the ribosome, Ribo-seq can accurately determine the translation events in RNAs, including small open read frames (sORF) containing fewer than 100 amino acids32,33,34,35,36,37. When integrated with corresponding RNA-seq data, Ribo-seq further enables the quantification of the gene’s translational efficiency (TE) by normalizing ribosome footprint density with RNA abundance38. Notably, investigation of TE dynamics has yielded significant insights into translational regulation in various biological processes. For instance, reduced TE of genes involved in pathogenesis and filamentation was discovered in Candida albicans during morphogenesis39; TE of genes is frequently controlled by changing usage in uORFs during retinal development in mouse40. Thus, this powerful approach provides great opportunities to investigate the translational landscape comprehensively and to gain a deeper understanding of the parasitism mechanisms of RKNs.

M. incognita is recognized as one of the most harmful species of this genus, causing global annual losses of approximately $100 billion16. In this study, we established an integrated approach that combines Ribo-seq, RNA-seq and quantitative proteomics data for the in-depth analysis of the translational landscape of M. incognita during parasitism. We uncovered numerous previously unannotated translation events and demonstrated that the genes in M. incognita are regulated at the translational level in a parasitic stage-specific manner during parasitism. Notably, we identified 470 micropeptides encoded by sORF with the potential to function as effectors. Furthermore, we observed that the effector-coding genes in M. incognita not only exhibit higher TE, but also that M. incognita can selectively enhance the TE of effector-coding genes without concurrent changes in transcript abundance. These findings not only unveil the translational landscape on genome-wide scale but also provide valuable insights into the critical role of translational regulation in orchestrating effector synthesis in M. incognita.

Results

Characterization of translational datasets based on transcriptome, translatome and proteome

To investigate the translational dynamics of genes in M. incognita before and after parasitism, we generated the Ribo-seq data in conjunction with RNA-seq and quantitative proteomics data from pre-parasitic second-stage juveniles (Pre-J2), parasitic third stage/fourth stage (J3/J4) and parasitic adult female stage (Female) (Fig. 1A). The quality of these multi-omics datasets was evaluated by mapping them to the reference genome (Mi_assembly_v1)41. After stringent quality filtering of sequencing reads and mapping, a total of 71.9 and 515.2 million (M) clean reads were yielded from Ribo-seq libraries and RNA-seq libraries, respectively (Supplementary Tables 1, 2). For the proteomic study, a total of 49,563 peptides were obtained and 4891 proteins were identified and quantified.

A Schematic overview of the experimental design in this study, depicting the investigated of translational dynamics at Pre-J2, J3/J4, and Female stages of M. incognita. B Length distribution of RPFs with a peak at 28 nt. C The proportion of RPFs mapped to different genomic features. D Length distribution of RPFs mapped to CDS regions. E Representative bar plots showing the peptidyl-site (P-site) positions derived from 28-nt RPFs, with the P-site positions color-coded according to the frame. F The proportion of RPFs mapped to the primary ORF and other possible frames. G–I Principal component analysis (PCA) of the transcriptome, translatome, and proteome data at Pre-J2, J3/J4, and Female stages of M. incognita.

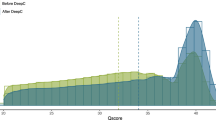

Subsequently, the characteristics of RPFs were initially examined as they are closely linked to the quality of Ribo-seq libraries. We found that the RPFs in M. incognita are approximately 28 nt long (Fig. 1B), and predominantly mapped to the coding sequence (CDS) (Fig. 1C), consistent with previous studies in free-living Caenorhabditis elegans42. Meanwhile, the length of RPFs that mapped in the CDS region also is around 28 nt (Fig. 1D). Corresponding to codon triplets, we found that the RPFs with 28 nt showed a clear 3-nt periodicity from their 5’ end to the start and stop codons (a key metric for confident ORF identification), and their P-site positions were mainly at +12 (Fig. 1E). Reading frame analysis for the mapped RPFs indicated that most of them are enriched in the first frame of the CDS (Fig. 1F). These results demonstrated similar features to previous studies in other organism43, and suggested the high quality of Ribo-seq data were obtained in this study. Correlation analysis indicated that the replicates of the three types of libraries (transcriptome, translatome, and proteome) exhibited a high degree of correlation, with each set of replicates clustering together as anticipated (Supplementary Fig. 1). The principal component analysis (PCA) of multi-omics data showed a high repeatability between replicates and clear stage-specific clustering (Fig. 1G-I). Together, these results suggested that the high-quality multi-omics data were obtained in this study and suitable for further analysis.

Integrative analysis of multi-omics identifies extensive unannotated translation events in M. incognita

To comprehensively catalog actively translated ORFs in M. incognita on a genome-wide scale, we performed transcript assembly using RNA-seq data to identify the novel transcripts that could potentially encode for proteins (Fig. 2A). By comparing with the reference genome annotation of M. incognita, we identified 2,713 novel transcripts, which were classified into 5 classes: intergenic (class code “u”, 1,274), intronic (class code “i”, 626), cis-natural antisense transcripts (class code “x”, 648), and others (class code “y”, 54; and class code “o”, 111). In addition, we utilized a common method44 (described in the Methods section) to predict lncRNAs in the 5 classes of novel transcripts, which led to the identification of 1,764 putative lncRNAs (Fig. 2A). Subsequently, we used RiboCode45 in conjunction with Ribo-seq data to identify the actively translated ORFs among the 5 classes of novel transcripts, resulting in the identification of 820 actively translated ORFs, and 51 of which were validated and quantified by proteomic data (Fig. 2B). Notably, among the 820 newly discovered ORFs, 401 of them are coding micropeptides (containing fewer than 100 amino acids). Additionally, we further observed that 29.7% of the novel translated ORFs were derived from the putative lncRNAs (Fig. 2C).

A Analysis workflow for novel transcript discovery and lncRNA prediction, the class codes of novel transcripts were adapted from gffcompare73, class code “u”: intergenic, class code “i”: novel transcript fully contained in an annotated intron, class code “x”: exon match on the opposite strand, class code “y”: contains a reference within its introns, and class code “o”: other same strand overlap with reference exons. The transcripts with no hits against the eggNOG database were retained and subsequently filtered by LGC tool75 and coding potential calculator (CPC2)76 to remove the transcripts with coding potential. B Number of actively translated ORFs identified from novel transcripts. C Proportion of actively translated ORFs identified from putative lncRNAs. D Number of actively translated ORFs identified from reference genome annotation: annotated ORFs, ORFs overlapping with annotated CDS with the same start and stop codon; internal ORFs, ORFs located within annotated CDS but in different reading frame; overlapped ORFs, ORFs located upstream or downstream of annotated CDS and overlapping with them; dORFs, ORFs located downstream of annotated CDSs but not overlapped with annotated CDSs; uORFs, the ORFs located upstream of annotated CDS but not overlapping with them. E Visualization of read coverage on actively translated ORFs at transcriptional and translational levels using Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV).

Meanwhile, the detection of actively translated ORFs in the reference genome of M. incognita were also performed, we identified 27,867 annotated ORFs with translational activity, with 4,834 being verified and quantified through proteomic data (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, we also identified 129 downstream ORFs (dORFs), 51 upstream ORFs (uORFs), 81 internal ORFs, and 55 overlapped ORFs from the genome of M. incognita and verified 11 stable proteins generated from these ORFs through proteomic data (Fig. 2D). By visualizing the read coverage of the actively translated ORFs at transcriptional and translational levels, the reliability of our translational datasets we further verified (Fig. 2E). Additionally, a search of the newly discovered ORFs against the recently published M. incognita genome46 revealed that only 159 of these ORFs were present in the updated genome. Therefore, these results confirmed that the approach of identifying actively translated ORFs in this study is robust, and a vast array of unannotated ORFs with translational activity refined the genome annotation of M. incognita.

M. incognita regulates gene translation in a parasitic stage-specific manner during parasitism

To achieve a comprehensive understanding of the translational dynamics of genes in M. incognita before and after parasitism, we performed deltaTE analysis47 using Pre-J2 stage as the control and integrated Ribo-seq and RNA-seq datasets to categorize genes into differentially transcribed genes (DTGs, regulated by transcriptional abundance) and differential TE genes (DTEGs, regulated by TE) (Fig. 4A). We revealed that, compared to the pre-parasitic stage, only 9% (975) of the total regulated genes were attributed to changes in TE (DTEGs) at J3/J4 stages, comprising 447 up-regulated DTEGs and 528 down-regulated DTEGs (Fig. 3B, D). Conversely, approximately 17.5% (2,756) of the total regulated genes exhibited changes in TE (DTEGs) at Female stages, consisting of 1,632 up-regulated DTEGs and 1124 down-regulated DTEGs (Fig. 3C, E). Notably, 52 DTEGs at the J3/J4 stage and 185 DTEGs at the Female stage were further validated at the protein levels by proteomic analysis, suggesting that changes in TE directly contribute to corresponding changes in protein abundance (Supplementary Data 2). Furthermore, through Venn analysis, we demonstrated that only 5.8% (204) of DTEGs were simultaneously regulated at the translational level at the J3/J4 and Female stages when compared to the Pre-J2 stage (Fig. 3F). To gain insights into the potential function of DTEGs during M. incognita parasitism, we conducted Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis on the DTEGs at J3/J4 and Female stages and found that these DTEGs were enriched in several molecular function related to ‘cell adhesion molecule binding’, ‘protein binding’, ‘catalytic activity’ and ‘hydrolase activity’ (Supplementary Fig. 2). Overall, these results suggest that the functional genes are regulated at the translational levels by M. incognita in a parasitic stage-specific manner.

A Categories of gene expression regulation based on translational and transcriptional changes. B, C Scatter plot showing log2(foldchange) values of DTGs and DTEGs at J3/J4 and Female stages compared to Pre-J2 stage. D, E Scatter plot displaying up- and down-regulated DTEGs at J3/J4 and Female stage compared to Pre-J2 stage. Red and blue dots represent mRNAs with up- and down-regulated TE, respectively. Genes under statistical threshold not shown in volcano plots. F Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of DTEGs between J3/J4 and Female stages.

M. incognita harbors a repertory of micropeptides with potential to function as effector

As pivotal components for successful parasitism, the secretion of effectors is crucial for establishing feeding site and manipulating host immune defense during M. incognita parasitism48. Recently, there is growing interest in the role of peptide effectors (amino acids < 100) during the parasitic process of plant-parasitic nematodes49. Based on the deep-sequencing for RPFs, Ribo-seq provides key information of ribosome positions and thereby has the tremendous potential and advantage to identify translated sORFs50,51. In this study, we identified 1,932 actively translated sORFs encoding micropeptides (less than 100 amino acids). Among these, 470 micropeptides were found to have potential secretory capabilities, as they contain a signal peptide but lack transmembrane domains. These micropeptides are referred to as potential small secretory peptides (PSSPs). Of these, 52 were further confirmed through proteomic data, indicating the effective translation of these PSSPs (Fig. 4A). The exon number distribution of the PSSPs showed that 79.8% (375) are encoded by 2–3 exons (Fig. 4B). Length distribution of the PSSPs revealed that most are concentrated between 60 and 100 amino acids (Fig. 4C). In addition, we investigated the localization of a specific PSSP-coding gene (Mi_25001) in M. incognita through in situ hybridization. As expected, we detected strong signals (Mi_25001) in the esophageal gland of J3/J4 stage, which is known to be the primary site for effector synthesis in plant-parasitic nematodes (Fig. 4D, F). These results provide evidence that M. incognita harbors a repertory of micropeptides with the potential to function as effector.

A Number of PSSP identified in M. incognita and the proportion of PSSP verified by proteomics. B Distribution of exon number in genes encoding PSSP. C Length distribution of PSSP in M. incognita. D–F Detection of transcripts for PSSP (Mi_25001) using in situ hybridization (ISH) in M. incognita adult females. D No ISH signal observed in the sense probe. Bar = 100 µm. E, F) ISH signal detected in the esophageal gland (G) of M. incognita J3/J4 stage using digoxingenin-labeled antisense probe. Bar = 100 µm.

The effector-coding genes of M. incognita exhibit higher TE

To investigate the translational regulation of effector-coding genes of M. incognita during parasitism, a total of 3,168 potential secretory protein (including 470 potential small secretory peptides) from the actively translated ORFs were identified (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Among these, 7.04% (223) were encoded by the newly discovered translated ORFs (Supplementary Fig. 3B). We then compared the expression divergence between potential secretory protein-coding genes and non-secretory protein-coding genes at both the translational and transcriptional levels. Surprisingly, we observed higher expression variances in potential secretory protein-coding genes compared to non-secretory protein-coding genes at both levels. (Fig. 5A, B). These results indicate that potential secretory protein-coding genes are subject to broader regulation. Interestingly, further analysis revealed a higher TE in potential secretory protein-coding genes compared to non-secretory protein-coding genes (Fig. 5C), signifying an accelerated rate of protein synthesis. This finding implies that the effectors of M. incognita may undergo regulation at the translational level, facilitating their rapid synthesis and secretion.

A, B Distribution of expression value for potential secretory protein-coding genes and non-secretory protein-coding genes at translational and transcriptional levels across Pre-J2, J3/J4 and Female stages. C Comparison of TE between potential secretory protein-coding genes and non-secretory protein-coding genes. D Comparison of TE between published effector-coding genes and non-secretory protein-coding genes. The asterisks ‘***’ represent significantly different, p < 0.001, Wilcoxon tests).

To validate our hypothesis, previously published effectors in RKNs were compiled. Through a homolog search (identity > 90) with these published effectors, 28, 42, and 43 effectors were identified from the Pre-J2, J3/J4, and Female stages, respectively. We further calculated the TE divergence between the published effector-coding genes and the potential secretory protein-coding genes, the results revealed a relatively low difference in TE divergence between these two groups (Supplementary Fig. 4). Notably, we compared the TE of the published effector-coding genes with non-secretory protein-coding genes, we found that the M. incognita effectors exhibit higher TE (Fig. 5D). These findings confirm that the regulation of M. incognita effectors can indeed occur at the translational level.

M. incognita has the potential to regulate the TE of effector-coding genes without simultaneous alterations in their transcript abundance

To gain deeper insights into the translational regulation of M. incognita effectors during before and after parasitism, we identified the potential secretory protein-coding genes that exhibited differential regulation in TE or transcriptional abundance at the J3/J4 and Female stages compared to the Pre-J2 stage. These potential secretory protein-coding genes were categorized into four distinct regulatory classes: forwarded (where both mRNA and RPF abundances were regulated at similar rates, resulting in no significant change in TE), buffered (where changes in TE counterbalanced changes in mRNA levels), intensified (where changes in translational efficiency amplified the effect of mRNA regulation), and exclusive (where significant changes in RPF occurred without corresponding mRNA changes, leading to substantial alterations in TE) (Fig. 6A). As a result, we found that the majority (82.2%, 1147) of potential secretory protein-coding genes with differential regulation at the J3/J4 stage, compared to the Pre-J2 stage, were classified into the forwarded category. Notably, among the potential secretory protein-coding genes showing differential regulation at the Female stage compared to the Pre-J2 stage, the majority were classified into the forwarded and buffered category. Specifically, 50.1% (836) were categorized as forwarded, and 39.4% (658) as buffered (Fig. 6B).

A Log-fold changes in ribosome occupancy and mRNA levels, exemplified by the comparison between J3/J4 and Pre-J2 stages. Translationally forwarded genes (in blue), exclusive genes (in red), buffered genes (in yellow), and intensified genes (in yellow) are highlighted. B Number of differentially expressed secretory protein-coding genes categorized at J3/J4 and Female stages into four categories. C, D Comparison of log-fold changes at translational and transcriptional levels for potential secretory protein-coding genes in the exclusive class.

Interestingly, our findings also revealed that 56 and 120 potential secretory protein-coding genes with differential regulation at the J3/J4 and Female stages were classified into the exclusive category (Fig. 6B). Among these exclusive genes, 39 exhibited significant up-regulation in TE at the J3/J4 stage, and 102 (including 2 previously published effectors) showed similar TE up-regulation at the Female stage without corresponding changes in transcriptional abundance (Fig. 6C, D). Furthermore, quantitative proteomic analysis confirmed that the protein abundance of 3 potential secretory protein-coding genes increased significantly at the Female stage, despite no changes in their transcript levels compared to the Pre-J2 stage, further emphasizing the critical role of translational regulation in protein production. These findings highlight the importance of TE modulation in rapidly altering protein production, as regulating TE is faster than initiating new RNA synthesis and increasing transcript abundance. Overall, these results suggest that M. incognita has the potential to regulate the TE of effector-coding genes without simultaneous alterations in their transcript abundance, facilitating their synthesis.

Discussion

RKNs are notorious for infecting nearly all major crops, leading to significant losses, and are considered the most economically important plant-parasitic nematodes52. Although substantial progress in understanding the transcriptional regulation involved in RKN parasitism, the role of translational regulation in this process is poorly understood, necessitating further investigation to unravel its intricacies. In this study, we conducted translatome, transcriptome, and quantitative proteome analyses at different parasitic stages of M. incognita (Fig. 1), these multi-omics data enabled us to uncover key insights into the translational landscape of M. incognita during parasitism.

Ribo-seq, by deep-sequencing RPFs, allows for genome-wide monitoring of translation events and has opened avenues for re-evaluation of the coding potential of ORFs previously presumed to be non-translating53. For instance, an increasing number of actively translated ORFs have been discovered within nonclassical RNA molecules, including those previously categorized as lncRNAs36,54,55. To uncover previously unannotated events in M. incognita, we prepared RNA-seq libraries in this study by excluding ribosomal RNA, enabling the capture of all RNA types with translational potential. Consequently, we identified 1764 putative lncRNAs along with 244 actively translated ORFs within these lncRNAs (Fig. 2A, C). These results suggested that the accurate annotation of the M. incognita genome necessitates consideration of the actively translated ORFs located in all types of RNAs. Recent evidence also suggests that the lncRNA-encoded peptides play important roles in the development, for instance, the small peptide encoded by pri, previously identified as a lncRNA in Drosophila, has essential roles in epithelial morphogenesis56, and the peptide LINC01116 from cytoplasmic lncRNA in human contributes to neuronal differentiation57. Therefore, the discovery of widespread unannotated events in M. incognita not only refines the genome annotation but also suggests that these protein products may have important functions.

In recent years, the roles of peptide effectors (amino acids < 100) of plant-parasitic nematodes in the parasitism process have gained increasing attention. For instance, 16D10, a 13-aa peptide effector, has been reported to interact with plant SCARECROW-like family transcription factors and is required for RKN parasitism58,59. Recently, RAPID ALKALINIZATION FACTOR (RALF)-like peptide effectors (42-54 aa) were identified in RKNs, demonstrating that these RALF-like peptide effectors not only possess the typical activities of plant RALFs but also directly bind to the extracellular domain of FERONIA to modulate specific steps of nematode parasitism-related immune responses, thereby facilitating parasitism60. In this study, we harnessed the advantages of Ribo-seq to detect actively translated sORFs, revealing the presence of 470 PSSPs (Fig. 3). Notably, our analysis shows that nearly 80% of these PSSPs are encoded by genes containing 2–3 exons. This observation suggests a streamlined genomic structure that may be functionally significant for the rapid production of these micropeptides during parasitism. As a proof of concept, we further confirmed the specific expression of a given PSSP within the nematode secretory organs-esophageal gland (Fig. 3D, F). Although the function of most PSSP in M. incognita remains unknown, the identification of PSSPs repertoire provides a valuable resource for the identification of peptide effectors in M. incognita.

TE, quantifying ribosome occupancy in each mRNA molecule, represents a genome-wide measurement of translational dynamics. In this study, we unveiled the dynamic alterations of TE in functional genes and found that DTEGs contributed 0.09–17.5% of the regulatory changes in a parasitic stage-specific manner during M. incognita parasitism (Fig. 4). Notably, the importance of regulating TE in functional genes has been validated in various contexts. For instance, differential TE in orthologous genes has been shown to contribute to phenotypic differences among yeast species61. Additionally, TE differences between healthy and tumor tissues have been linked to proliferation62. Hence, the identification of TE regulation in numerous functional genes within this study strongly suggests that translational regulation likely plays a significant role in the parasitism of M. incognita.

Using various effectors to suppress host immune responses and establish feeding sites has been identified as the main strategy for RKNs63,64. Thus, the rapid synthesis and secretion of effectors are critical for the parasitism of M. incognita. In this study, we demonstrated that potential secretory protein-coding genes in M. incognita not only have higher TE compared to non-secretory protein-coding genes (Fig. 5), but also some of them experience an increase in TE alone, with no changes in their transcription abundance (Fig. 6). The genetic information stored in the genome undergoes a series of complex processes, including transcription, mRNA splicing, transport, localization, and translation, to produce the proteins65. Regulating TE can avoid global perturbations from transcription to translation, save time and energy consumption, and thereby provide a faster way to produce proteins than to regulate RNA abundance. This observation underscores the importance of considering translational regulation, as solely focusing on changes in transcript abundance may result in overlooking crucial effectors primarily controlled at the translational level. Together, our study provides a comprehensive exploration of the genome-wide translational landscape in M. incognita.

Methods

Nematode sample collection

M. incognita was propagated on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum cv. Jinpeng No. 3) in pots containing soil and sand (1 : 1) and grown under photoperiod conditions of 16 h : 8 h, light : dark, at 25 °C conditions.

The egg masses of M. incognita were collected from tomato roots and hatched in water at 25 °C to collect the fresh-hatched J2s (Pre-J2). After the removal of the egg masses, the tomato roots were crushed to collect J3/J4 (sausage shaped) and adult female (pear shaped) of M. incognita under a microscope. The collected Pre-J2, J3/J4, and adult female were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Three independent biological replicates were conducted for RNA-seq, Ribo-seq, and proteomic library construction at the three different developmental stages of M. incognita.

Ribo-seq library construction and sequencing

The Ribo-seq libraries were constructed following a previously established method with adjustments42. Briefly, the worm pellets were then cryogenically pulverized and lysed with lysis buffer consisting of 0.1 mg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma). The lysates were treated with RNase I to digest the fragments that are not protected by ribosome and then transferred into a MicroSpin S-400 column to enrich the ribosome-RNA complex (monosomes). The ribosome-protected fragments (RPFs) were then extracted and used to prepare the library with the NEBNext Small RNA Library Prep Set according to the description of the manufacturer. Finally, the prepared libraries were sequenced and SE50 reads were generated on Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform.

RNA-seq library construction and sequencing

The J2s, J3/J4 and adult female of M. incognita were collected as described above and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The ribosome RNA was firstly removed from total RNA and the strand-specific RNA-seq libraries were constructed with NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit. The prepared libraries were sequenced and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated on Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform.

Total protein preparation and label-free MS

The J2s, J3/J4, and adult female of M. incognita were collected as described above and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The worm pellets were then cryogenically ground and lysed with lysis buffer (8 M urea, 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8). The lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatants were subsequently reduced by being treated with 10 mM DTT at 56 °C for 1 h. The samples were then alkylated with sufficient iodoacetamide for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. After washing with the cold acetone, the protein samples were collected and dissolved by dissolution buffer (8 M Urea, 100 mM TEAB, pH 8.5). Subsequently, the protein quantity and quality were evaluated using Bradford Protein Assay Kit (BioRad) and SDS-PAGE, respectively. The proteins were then digested with trypsin and submitted for MS detection on the Thermo Scientific Q Exactive platform by the label-free method.

All of the detected spectra were matched with the protein database of M. incognita using the Proteome Discoverer 2.2 (PD 2.2, Thermo) search engine with following parameters: mass tolerance for precursor ion 10 ppm, mass tolerance for product ion 0.02 Da, carbamidomethyl was specified as a fixed modification, oxidation of methionine as a dynamic modification, acetylation as an N-terminal modification, and up to two missed cleavage sites were allowed. The results were then further improved with the following criterion: peptide spectrum matches (PSMs) with over 99% credibility, identified proteins with at least one unique peptide, and retaining PSMs and proteins with a false discovery rate (FDR) no greater than 1.0%. The protein quantitation results were statistically analyzed by T-test and Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated using the quantitation results to assess the consistency between replicates. The differentially expressed proteins were identified by the criteria (Pvalue < 0.05 and |log2FC | >1) by comparing the quantitation difference in the two conditions.

Ribo-seq data analysis

Adapter, low-quality reads, and the low-quality bases at the ends of reads in Ribo-seq data were filtered by Fastp (version=0.20.1)66. The rRNA in Ribo-seq data were filtered by matching reads to the SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database (release 138)67 using bowtie (version=2.4.2)68. After filtering, the clean reads of Ribo-seq data were mapped to the genome of M. incognita (Mi_assembly_v1)41 using the STAR aligner (version= 2.7.6a, --outFilterMismatchNmax 2, --outFilterMatchNmin 16, --alignEndsType EndToEnd)69. The RSEM software (version = 1.3.1)70 was used to generate the count tables. The abundance_estimates_to_matrix.pl script within the Trinity suite was used to generate a merged counts table and the matrix of transcripts per million (TPM)-normalized expression values. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated using the expression values to assess the consistency between replicates. The nucleotide resolution of the coverage around start and stop codons, the ribosome P-site triplet periodicity, and the RPF-based ORF identification were analyzed according to the manual of RiboCode (v.1.2.11)45. The ORFs identified by RiboCode can be classified into five types as follows: annotated ORFs, the ORFs overlap with annotated CDSs and have the same start and stop codon with annotated CDSs; internal ORFs, the ORFs located in internal regions of annotated CDSs, but in a different reading frame; overlapped ORFs, the ORFs located upstream or downstream of annotated CDSs and overlapping with annotated CDSs; dORFs, the ORFs located downstream of annotated CDSs but not overlapped with annotated CDSs; uORFs, the ORFs located upstream of annotated CDSs but not overlapped with annotated CDSs. The statistics and length distribution of RPFs were analyzed in R (version=4.1.1).

RNA-seq data process, transcript assembly, and lncRNAs prediction

Adapter and low-quality reads of RNA-seq data were filtered by Trimmomatic software (version = 0.36)71 and the rRNA were filtered as described above. The STAR aligner (version = 2.7.6a)69 was used to align clean reads of RNA-seq data to the genome of M. incognita (Mi_assembly_v1)41. The expression levels of genes in reference genome annotation were generated as described above and Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated using the expression values to assess the consistency between replicates. The mapped reads were used to perform the reference-guide transcript assembly with StringTie (version=2.1.2)72. The gffcompare (version=0.11.2)73 was utilized to compare the newly assemble gtf files with the reference annotation. Novel transcripts, categorized as intergenic (class code “u”), intronic (class code “i”), cis-natural antisense transcripts (class code “x”), and others (class code “y” and class code “o”) were extracted from the comparison result. The description and nomenclature of these novel transcripts were adapted based on the gffcompare73. The novel transcript lengths longer than 200 bp and with a TPM > 1 were used for the prediction of lncRNAs. The putative longest ORFs were extracted from the novel transcripts using ORFfinder (version=0.4.3) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/) and then submitted to orthology-based annotation with eggNOG-mapper webtool (HMMER mapping mode)74. The transcripts with no hits against the eggNOG database were retained and subsequently filtered by LGC tool75 and coding potential calculator (CPC2)76 to remove the transcripts with coding potential. The retained transcripts were considered putative lncRNAs.

Differential expression and gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis

The differential expression analysis was conducted with the deltaTE47 method, which introduces an interaction term to the DESeq2 statistical model to determine the DTGs (|log2FC | > 1 and FDR < 0.05) and DTEGs (|log2FC | > 0.58 and FDR < 0.05) with read counts generated by RSEM from Ribo-seq and RNA-seq as input. The Gene Ontology (GO) annotation of genes was performed by eggNOG-mapper v2 (http://eggnog-mapper.embl.de/). GO enrichment analysis was performed based on a hypergeometric test (P < 0.05).

Secretory protein identification, calculation of expression variances and TE, and differential expression analysis

Proteins with secretory signal peptide and no transmembrane domain were defined as secretory proteins. In this study, the secretory signal peptide was predicted with the SignalP (version=5.0b)77, a SignalP score greater than 0.5 was considered indicative of the presence of a signal peptide, and the transmembrane domain was predicted with TMHMM (version=2.0, https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/service.php?TMHMM-2.0). The expression variances were calculated from the expression matrix in R. TE was calculated as TPM from Ribo-seq divided by TPM from RNA-seq. The differentially expressed secretory protein genes were identified using the deltaTE method and further categorized into four classes: buffered, intensified, forwarded, and exclusive.

In situ hybridization of potential small secretory peptides

Using a modified version of the in situ hybridization method78, the DIG-labeled specific probe for the potential small secretory peptide (Mi_25001) was amplified with the following primers: sense primer (TGTACATGTCCTAATGCTTC) and anti-sense primer (ATAAGATCCCCATAATTTCT). In situ hybridization was conducted on the J3/J4 stage of M. incognita utilizing the MyLab DIG Labeling and Hybridization Detection System-DIG DNA PCR Labeling Kit (MyLab Corp., Beijing) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the nematode bodies were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 24 h and then chopped on a glass slide. The chopped nematodes were digested with proteinase K (1 mg/mL) for 2 h. Subsequently, the nematode bodies were hybridized with the DIG-labeled specific probe at 40 °C for 16 h. Finally, the hybridization signal was detected using an anti-DIG antibody and observed under a microscope.

Statistics and reproducibility

In this study, each experiment was conducted with three independent biological replicates, which were subsequently analyzed. Statistical analyses and data visualization were carried out using R (version 4.3.0). The Wilcoxon test was employed to compare the TE between different types of protein-coding genes, with significance levels defined as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The source data supporting the graphs in this paper are available from the Supplementary Data 1 and 2. The Ribo-seq and RNA-seq data generated in this study have been submitted to the NCBI BioProject database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/) under accession number PRJNA957683. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the iProX partner repository79,80 with the dataset identifier PXD046565.

Code availability

In this study, all software utilized was open-access, with parameters clearly outlined in the Methods section. When specific software parameters were not detailed, the default settings recommended by the developers were applied.

References

Morris, C. E. & Moury, B. Revisiting the concept of host range of plant pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 57, 63–90 (2019).

Petre, B., Lorrain, C., Stukenbrock, E. H. & Duplessis, S. Host-specialized transcriptome of plant-associated organisms. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 56, 81–88 (2020).

Enguita, F. J., Costa, M. C., Fusco-Almeida, A. M., Mendes-Giannini, M. J. & Leitão, A. L. Transcriptomic crosstalk between fungal invasive pathogens and their host cells: Opportunities and challenges for next-generation sequencing methods. J. Fungi 2, 7 (2016).

Zhang, D. et al. Global and gene-specific translational regulation in Escherichia coli across different conditions. PLoS Comp. Biol. 18, e1010641 (2022).

Zhang, C., Wang, M., Li, Y. & Zhang, Y. Profiling and functional characterization of maternal mRNA translation during mouse maternal-to-zygotic transition. Sci. Adv. 8, eabj3967 (2022).

Vogel, C. & Marcotte, E. M. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 227–232 (2012).

Jiang, L.-G. et al. Characterization of proteome variation during modern maize breeding. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 18, 263–276 (2019).

Sawyer, E. B., Phelan, J. E., Clark, T. G. & Cortes, T. A snapshot of translation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis during exponential growth and nutrient starvation revealed by ribosome profiling. Cell Rep. 34, 108695 (2021).

Hershey, J. W. B., Sonenberg, N. & Mathews, M. B. Principles of translational control: An overview. CSH Perspect Biol 4, a011528 (2012).

Teixeira, F. K. & Lehmann, R. Translational control during developmental transitions. CSH Perspect Biol 11, a032987 (2019).

Sajeev, N., Bai, B. & Bentsink, L. Seeds: a unique system to study translational regulation. Trends Plant Sci. 24, 487–495 (2019).

Warmerdam, S. et al. Genome-wide association mapping of the architecture of susceptibility to the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita in Arabidopsis thaliana. N. Phytol. 218, 724–737 (2018).

Forghani, F. & Hajihassani, A. Recent advances in the development of environmentally benign treatments to control root-knot nematodes. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 1125 (2020).

Abad, P. et al. Genome sequence of the metazoan plant-parasitic nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 909 (2008).

Nguyen, C. N. et al. A root-knot nematode small glycine and cysteine-rich secreted effector, MiSGCR1, is involved in plant parasitism. N. Phytol. 217, 687–699 (2018).

Subedi, S., Thapa, B. & Shrestha, J. Root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita) and its management: a review. J. Agric. Nat. Resour. 3, 21–31 (2020).

Choi, I., Subramanian, P., Shim, D., Oh, B.-J. & Hahn, B.-S. RNA-seq of plant-parasitic nematode Meloidogyne incognita at various stages of its development. Front. Genet. 8, 190 (2017).

Li, X., Yang, D., Niu, J., Zhao, J. & Jian, H. De novo analysis of the transcriptome of Meloidogyne enterolobii to uncover potential target genes for biological control. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 1442 (2016).

Shukla, N. et al. Transcriptome analysis of root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita)-infected tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) roots reveals complex gene expression profiles and metabolic networks of both host and nematode during susceptible and resistance responses. Mol. Plant Pathol. 19, 615–633 (2018).

Haegeman, A., Bauters, L., Kyndt, T., Rahman, M. M. & Gheysen, G. Identification of candidate effector genes in the transcriptome of the rice root knot nematode Meloidogyne graminicola. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14, 379–390 (2013).

Petitot, A.-S. et al. Dual RNA-seq reveals Meloidogyne graminicola transcriptome and candidate effectors during the interaction with rice plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 17, 860–874 (2016).

Shi, Q. et al. The novel secreted Meloidogyne incognita effector MiISE6 targets the host nucleus and facilitates parasitism in Arabidopsis. Frontiers in Plant Science 9, 252 (2018).

Dubreuil, G., Magliano, M., Deleury, E., Abad, P. & Rosso, M. N. Transcriptome analysis of root-knot nematode functions induced in the early stages of parasitism. N. Phytol. 176, 426–436 (2007).

Mbeunkui, F., Scholl, E. H., Opperman, C. H., Goshe, M. B. & Bird, D. M. Proteomic and bioinformatic analysis of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne hapla: the basis for plant parasitism. J. Proteom. Res. 9, 5370–5381 (2010).

Bellafiore, S. et al. Direct identification of the Meloidogyne incognita secretome reveals proteins with host cell reprogramming potential. PLoS Path 4, e1000192 (2008).

Wang, X. R. et al. Proteomic profiles of soluble proteins from the esophageal gland in female Meloidogyne incognita. Int. J. Parasitol. 42, 1177–1183 (2012).

Drew, K. et al. Integration of over 9,000 mass spectrometry experiments builds a global map of human protein complexes. Mol. Syst. Biol. 13, 932 (2017).

Laczkovich, I. et al. Discovery of unannotated small open reading frames in Streptococcus pneumoniae D39 involved in quorum sensing and virulence using ribosome profiling. mBio 13, e01247–01222 (2022).

Vasquez, J.-J., Hon, C.-C., Vanselow, J. T., Schlosser, A. & Siegel, T. N. Comparative ribosome profiling reveals extensive translational complexity in different Trypanosoma brucei life cycle stages. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 3623–3637 (2014).

Parsons, M. & Myler, P. J. Illuminating parasite protein production by ribosome profiling. Trends Parasitol. 32, 446–457 (2016).

Ingolia, N. T., Ghaemmaghami, S., Newman, J. R. S. & Weissman, J. S. Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science 324, 218–223 (2009).

Wu, H.-Y. L., Song, G., Walley, J. W. & Hsu, P. Y. The tomato translational landscape revealed by transcriptome assembly and ribosome profiling. Plant Physiol. 181, 367–380 (2019).

Zhang, H. et al. Genome-wide maps of ribosomal occupancy provide insights into adaptive evolution and regulatory roles of uORFs during Drosophila development. PLoS Biol. 16, e2003903 (2018).

Martinez, T. F. et al. Accurate annotation of human protein-coding small open reading frames. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 458–468 (2020).

Hadjeras, L. et al. Unraveling the small proteome of the plant symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti by ribosome profiling and proteogenomics. microLife, 4, uqad012 (2023).

Zhu, X. T. et al. Ribosome profiling reveals the translational landscape and allele-specific translational efficiency in rice. Plant Commun. 4, 100457 (2022).

Ruiz-Orera, J., Villanueva-Cañas, J. L. & Albà, M. M. Evolution of new proteins from translated sORFs in long non-coding RNAs. Exp. Cell Res. 391, 111940 (2020).

Hsu, P. Y. et al. Super-resolution ribosome profiling reveals unannotated translation events in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 113, E7126–E7135 (2016).

Mundodi, V., Choudhary, S., Smith, A. D. & Kadosh, D. Global translational landscape of the Candida albicans morphological transition. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 11, jkaa043 (2020).

Chen, K. et al. Widespread translational control regulates retinal development in mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 9648–9664 (2021).

Dai, D. et al. Unzipped chromosome-level genomes reveal allopolyploid nematode origin pattern as unreduced gamete hybridization. Nat. Commun. 14, 7156 (2023).

Aeschimann, F., Xiong, J., Arnold, A., Dieterich, C. & Großhans, H. Transcriptome-wide measurement of ribosomal occupancy by ribosome profiling. Methods 85, 75–89 (2015).

Xu, W. et al. TP53-inducible putative long noncoding RNAs encode functional polypeptides that suppress cell proliferation. Genome Res. 32, 1026–1041 (2022).

Maciel, L. F. et al. Weighted gene co-expression analyses point to long non-coding RNA hub genes at different Schistosoma mansoni life-cycle stages. Front. Genet. 10, 823 (2019).

Xiao, Z. et al. De novo annotation and characterization of the translatome with ribosome profiling data. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, e61–e61 (2018).

Mota, A. P. Z. et al. Unzipped genome assemblies of polyploid root-knot nematodes reveal unusual and clade-specific telomeric repeats. Nat. Commun. 15, 773 (2024).

Chothani, S. et al. deltaTE: detection of translationally regulated genes by integrative analysis of Ribo-seq and RNA-seq data. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 129, e108 (2019).

Rutter, W. B., Franco, J. & Gleason, C. Rooting out the mechanisms of root-knot nematode-plant interactions. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 60, 43–76 (2022).

Mitchum, M. G. & Liu, X. L. Peptide effectors in phytonematode parasitism and beyond. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 60, 97-119 (2022).

Brar, G. A. & Weissman, J. S. Ribosome profiling reveals the what, when, where and how of protein synthesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 651–664 (2015).

Duffy, E. E. et al. Developmental dynamics of RNA translation in the human brain. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 1353–1365 (2022).

Trudgill, D. L. & Blok, V. C. Apomictic, polyphagous root-knot nematodes: exceptionally successful and damaging biotrophic root pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 39, 53–77 (2001).

Choudhary, S., Li, W. & D. Smith, A. Accurate detection of short and long active ORFs using Ribo-seq data. Bioinformatics 36, 2053–2059 (2019).

Guo, Y. et al. The translational landscape of bread wheat during grain development. Plant Cell 35, 1848–1867 (2023).

Anderson, D. M. et al. A micropeptide encoded by a putative long noncoding RNA regulates muscle performance. Cell 160, 595–606 (2015).

Kondo, T. et al. Small peptide regulators of actin-based cell morphogenesis encoded by a polycistronic mRNA. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 660–665 (2007).

Douka, K. et al. Cytoplasmic long noncoding RNAs are differentially regulated and translated during human neuronal differentiation. RNA 27, 1082–1101 (2021).

Huang, G. et al. A root-knot nematode secretory peptide functions as a ligand for a plant transcription factor. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact.® 19, 463–470 (2006).

Joshi, I. et al. Host delivered-RNAi of effector genes for imparting resistance against root-knot and cyst nematodes in plants. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 118, 101802 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Nematode-encoded RALF peptide mimics facilitate parasitism of plants through the FERONIA receptor kinase. Mol. Plant 13, 1434–1454 (2020).

Man, O. & Pilpel, Y. Differential translation efficiency of orthologous genes is involved in phenotypic divergence of yeast species. Nat. Genet. 39, 415–421 (2007).

Hernandez-Alias, X., Benisty, H., Schaefer, M. H. & Serrano, L. Translational efficiency across healthy and tumor tissues is proliferation-related. Mol. Syst. Biol. 16, e9275 (2020).

Jagdale, S., Rao, U. & Giri, A. P. Effectors of root-knot nematodes: an arsenal for successful parasitism. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 800030 (2021).

Vieira, P. & Gleason, C. Plant-parasitic nematode effectors—insights into their diversity and new tools for their identification. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 50, 37–43 (2019).

Zhu, W. et al. Large-scale translatome profiling annotates the functional genome and reveals the key role of genic 3′ untranslated regions in translatomic variation in plants. Plant Commun. 2, 100181 (2021).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2012).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2012).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 12, 323 (2011).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295 (2015).

Pertea, G. & Pertea, M. GFF Utilities: GffRead and GffCompare. F1000Research 9, 304 (2020).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. Fast genome-wide functional annotation through orthology assignment by eggNOG-Mapper. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 2115–2122 (2017).

Wang, G. et al. Characterization and identification of long non-coding RNAs based on feature relationship. Bioinformatics 35, 2949–2956 (2019).

Kang, Y. J. et al. CPC2: a fast and accurate coding potential calculator based on sequence intrinsic features. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W12–W16 (2017).

Almagro Armenteros, J. J. et al. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 420–423 (2019).

Jaouannet, M. et al. In situ hybridization (ISH) in preparasitic and parasitic stages of the plant-parasitic nematode Meloidogyne spp. Bio-Protoc. 8, e2766 (2018).

Ma, J. et al. iProX: an integrated proteome resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D1211–D1217 (2018).

Chen, T. et al. iProX in 2021: connecting proteomics data sharing with big data. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D1522–D1527 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank funding provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32470070 and U20A2040).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. performed the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. B.D., X.C., and D.D. assisted with the data analysis and participated in the material preparation. P.D. S.M. provided valuable feedback and participated in manuscript revisions. Z.J. conceived and designed the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Marc Bailly-Bechet, Chidam Mahadevan, Shiyang He and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Shahid Mukhtar and David Favero.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Z., Bo, D., Xie, C. et al. Integrative multi-omics analysis reveals the translational landscape of the plant-parasitic nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Commun Biol 8, 140 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07533-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07533-x