Abstract

It has been well established that Cornu Ammonis-(CA1) and subiculum (SUB) serve as the major output components of the entorhinal-hippocampal circuitry. Nevertheless, how the neuromodulators regulate the neurocircuitry in hippocampal formation has remained elusive. Cholecystokinin (CCK), is the most abundant neuropeptide in the central nervous system, which broadly regulates the animal’s physiological status at multiple levels, including neuroplasticity and its behavioral consequences. Here, we uncover that exogenous CCK potentiates the excitatory synaptic transmission in the CA1-SUB projections via CCK-B receptor. Dual-color light theta burst stimulation elicits heterosynaptic long-term potentiation in distal SUB region. Light activation of medial entorhinal cortex (MEC) derived CCK-positive neurons triggers the CCK release in the SUB. Neuronal activities of SUB-projecting MECCCK neurons are necessary for conveying and processing of navigation-related information. In conclusion, our findings prove a crucial role of CCK in regulating neurobiological functions in the SUB region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spatial navigation and memory are the essential functions of animals for survival in the external wild environment. The hippocampus consists of the dentate gyrus (DG), hippocampus proper and subiculum subfields1, which are crucially involved in conveying and processing of spatial information2. Through precise modulation of neuronal interactions with intra- and extrahippocampal circuitry, hippocampal neurons diversely represent various parameters of spatial navigation during environmental exploration, including the trajectory, place, speed, time and head direction3,4,5,6. Additionally, the spike timing of hippocampal neurons is precisely controlled and secured by multiple hippocampal neural oscillations, such as theta oscillations, gamma oscillations, and sharp-wave/ripples (SPW-Rs), thereby encoding and retrieving spatial information transmission between intra-and extra hippocampal regions6,7,8. The Cornu Ammonis-(CA1) and subiculum (SUB) serve as major neuronal output components of hippocampal proper, implying that both CA1 and SUB act as a functional hub by providing navigational information9. Moreover, Nakai et al. reported that the low-dimensional neural manifolds formed by the SUB encode various types of navigational details more accurately than the CA1, providing the neural basis for information processing in spatial navigation10. Moreover, compared with the CA1 in spatial behavioral tasks, SUB acts as a common and efficient component of navigational information10.

In recent years, several studies have demonstrated various aspects of the connectivity between the entorhinal cortex (EC) and the hippocampus proper, as well as intrinsic hippocampal connectivity, EC-DG, EC-CA2, EC-CA18,11,12. This multimodal association area conveys spatial and non-spatial sensory information to the hippocampus through its medial entorhinal cortex (MEC) and lateral entorhinal cortex (LEC) subdivisions, respectively. The SUB, like other hippocampal regions, receives its major neural inputs from the EC13. However, in contrast to the rest of the hippocampal formation, the SUB has received comparatively little empirical or theoretical investigation, although this situation has improved in recent years14,15,16,17. To date, the neuronal interaction between the EC and SUB in relation to neuroplasticity is still largely unknown. Moreover, it is not clear whether EC inputs are specifically involved in navigation memory in SUB.

Long-term potentiation (LTP) is considered as one of the major cellular mechanisms for learning and memory18, which has attracted tremendous attention from neuroscientists during the past several decades. LTP can be elicited by high-frequency electrical stimulation (HFS) or electrical theta burst stimulation (TBS) in the brain regions19. While electrical stimulation inevitably activate non-specifically neuronal components and compromises the conclusion, the well-established optogenetics technique allows for the precise targeting and control of neuronal activities via light-sensitive opsins, such as blue-light sensitive Channelrhodopsin-2 (chR2) and the yellow light-activated chloride pump halorhodopsin (eNpHR)20,21. Cholecystokinin (CCK) is a key peptide hormone involved in digestion and satiety in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. However, CCK also functions as a neuromodulator in the central nervous system (CNS). Although various forms of the peptide CCK (CCK-58, CCK-33, CCK-22, and CCK-8) are expressed in the GI tract, the octapeptide form (CCK-8) is the most abundant and plays a significant role in synaptic transmission within the CNS22,23,24. Neuronal CCK diversely modulates multiple aspects of an animal’s neurological and physiological status, including neuroplasticity and its behavioral implications. For instance, defects in neuronal CCK play an important role in several neuropsychiatric diseases, including anxiety and schizophrenia23,25. Our recent works have demonstrated that excitatory ECCCK projections facilitate the heterosynaptic LTP formation in the auditory cortex, amygdala and motor cortex, and further show influences on associative memory, trace fear memory and motor skill learning, respectively26,27.

Considering the SUB receives the neuronal inputs from the EC and most of the neurons in EC contain CCK. Thus, we hypothesize that ECCCK positive neurons might modulate the neurofunction in this critical brain region. To prove this hypothesis, we utilized transgenic mice, optogenetic manipulation, electrophysiological recording, GPCR-based sensor and fiber-photometry Ca2+ recording to elucidate how EC-derived CCK modulates the CA1-SUB circuitry and influences the performance of mice in diverse behavioral tasks. The extra-subicular CCK provides robust modulatory functions in the CA1-SUB circuitry, and thereby establishes a novel perspective of classic neuromodulators in the landscape of neuroscience at the neurophysiological and behavioral levels.

Results

Exogenous neuropeptide CCK potentiates the neuroplasticity of the CA1-SUB projections

To investigate the neural plasticity of the CA1-SUB pathway, we utilized the optogenetic technique to specifically target the CA1 pyramidal neurons (PNs). Thus, we injected the AAV9-mCamKIIa-ChrimsonR-mCherry (a variant of chR2) into the proximal CA1 (pCA1) region of the dorsal hippocampus to avoid the non-specific expression from CA1 to SUB region (Fig. 1A). Four weeks after the AAV expression (Fig. 1B, C), the sagittal slice was used for the field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) recording by using the multiple electrodes array (MEA) with a laser generator (Fig. 1D). Theta burst stimulation (TBS) is a classic protocol to induce long-term potentiation (LTP) both in vivo and in vitro under physiological conditions19 which typically consists of 10 high-frequency bursts (100 Hz, 5 pulses each) per second with an inter-trial interval (ITI) of 20 s. Considering the protein kinetic of the ChrimsonR during the electrophysiological recordings, we modified the TBS protocol and used light stimulus at 50 Hz per burst (Fig. 1E). A positive relationship was observed between the light intensity and the slope of the light-evoked fEPSPs (L- fEPSPs; Fig. 1F, G; Two-way mixed ANOVA (repeated-mersures), F6,7 = 1.26, p = 0.37, Bonferrori adjustment), implying a normal neural plasticity of the brain slice infected with the AAV. Intriguingly, no significant LTP was induced in distal subiculum (dSUB) by the red-light TBS (635 nm; RL-TBS) of CA1-SUB projections expressing ChrimsonR. Nevertheless, pairing with the exogenous neuropeptide CCK-4 with L-TBS remarkably potentiated the L-fEPSP of the CA1- SUB projections (Fig. 1H, I; Two-way mixed ANOVA, Bonferrori adjustment; F1,14 = 14.43, p = 0.002; L-TBS: Pre 100.74 ± 0.32% vs Post 99.66 ± 2.16%; p = 0.84; L-TBS + CCK: Pre 101.65 ± 2.04% vs Post 129.50 ± 2.04%; p < 0.001; Post L-TBS vs Post L-TBS, p = 0.003). These results indicate that neuropeptide CCK effectively enhances the homo-synaptic plasticity of CA1- SUB projections in the SUB region.

A Schematic diagram of virus injection. AAV9-mCaMKIIα-ChrimsonR-mCherry (5.0 E + 12 vg/ml, 100 nl) was injected into area proximal CA1 (pCA1) of wile-type (WT) mice. B Viral expression in the pCA1 area and its projections in the distal subiculum (dSub) area, scale bar: 1000 µm. C A magnified view of the square area (1; scale bar, 50 μm). D Schematic of the location of the stimulation fiber and recording electrodes. Red light was delivered via the 200 μm optical fiber above the dSub area. E The protocol of light TBS (L-TBS) for activating the ChrimsonR expressing pCA1-dSUB pathway of the WT mice. Scale, 0.2 mV by 20 ms. F A representative input-output (I/O) curve showing the L-fEPSP initial slope corresponding to the light intensity (Red: L-TBS + CCK, Dark: L-TBS). Scale, 0.5 mV by 10 ms. G Summary of the I/O responses of two groups. H CCK-4 (50 µM) potentiates the L-EPSPs responding to red light stimulation before and after L-TBS. Scale, 0.2 mV by 20 ms. I Quantitative data analysis for the L-fEPSP before and after manipulating L-TBS and CCK-4 (N = 4 animals, n = 8 recording sites in both two groups) *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns not significant. Data are reported as mean ± SEM.

Medial entorhinal cortex (MEC) exhibits the highest density of CCK source to dSUB PNs

Our previous works have shown that CCK-ergic projections from the ECCCK neurons are the major neuronal components for the induction of heterosynaptic long-term potentiation (hetero-LTP) in the auditory cortex and amygdala28,29. We thus deduced that EC may also send the most prominent CCK-ergic projections to the SUB region. We adopted retrograde labeling to validate this hypothesis. Cre-dependent AAV was injected into the dSUB region to specifically target CCK-positive inputs to dSUB in the whole-brain of CCK-Cre mice (Fig. 2A). After 4 weeks of AAV expression, the injection site was confirmed to be precisely localized in the dSUB region (Fig. 2B), and the neurons labeled with GFP were observed in various brain regions, including the CA1, CA3, dSUB and EC (LEC and MEC). Intriguingly, MEC showed the highest ration of GFP+/DAPI+ neurons compared to other regions (Fig. 2C). Additionally, to examine the neural characteristics of the CCK-ergic projection from the MEC to the dSUB region, we thus stained the excitatory neuronal marker anti-CamkIIα with the slices expressing the retrograde GFP in the MEC region (Fig. 2D). Unsurprisingly, most of the CCK-positive neurons were co-expressed with the anti-rabbit-594 (Fig. 2E), implying that excitatory CCK neurons in the MEC dominate the MECCCK-dSUB projections.

A Schematic diagram of retrograde virus (Retro AAV9-FLEX-Gcamp: 5.50E + 12 vg/mL, 50 nl) was injected into the dSUB area of CCK-Cre mice, and the retrograde labeling of neurons in the MEC area (1 and 2, scale bar: 1000 µm). B Distribution pattern of CCK positive inputs (GFP) to the dSub area in CCK-Cre mice. (CA1 cornu ammonis 1, CA3 cornu ammonis 3, Sub Subiculum, LEC Lateral entorhinal cortex, MEC Medial entorhinal cortex). Left images of injection site (scale bar: 500 µm) and retrograde areas (scale bar: 100 µm). C The ratio of GFP-labeled CCK-positive neurons to DAPI-labeled cells was assessed in various brain regions of CCK-Cre mice. D Co-immunofluorescent staining of CCK positive neurons with excitatory neuronal marker (CamKIIα) in MEC area. Scale bar: 100 μm. E Bar chart showing the proportion of CamKIIα positive neurons in GFP-labeled CCK positive neurons (N = 2 mice, n = 9 slices).

Light-TBS of the MECCCK-dSUB projections failed to induce LTP

To explore the neural plasticity of MECCCK-dSUB afferents in the SUB region, we thus injected the Cre-dependent virus (AAV9-hSyn-CaMKIIa-Flex-Chronos-GFP) into the MEC of the CCK-Cre mice (Fig. 3A). 4 weeks after AAV infection, both the injection site and the projection area showed strong AAV expression (Fig. 3B, C). Besides, we confirmed that GFP expressing excitatory MECCCK neurons are almost co-labeled with pro-CCK antibody (93.80%; Fig. 3D, E), indicating that the high specificity of AAV9-CamKIIα-FLEX-re [Chronos-GFP] for infecting the excitatory MECCCK neurons of CCK-Cre mice. Then, we utilized the 473 nm wavelength light (blue light) to specifically activate the MECCCK-SUB projections expressing Chronos (a variant of chR-2), which can evoke robust L-fEPSPs with increasing power intensity of the blue light in the dSUB region (Fig. 3F, G). After recording a stable baseline for 30 mins, the modified blue light -TBS (473 nm; BL-TBS) was given to the MECCCK-SUB projections in the dSUB area (Fig. 3H). Interestingly, no significant LTP was induced by high-frequency light manipulation (Fig. 3I, J; Paired samples t-test, df = 9.0, t = −1.03; Pre 99.26 ± 0.25% vs Post 102.14 ± 2.77%, p = 0.33). Additionally, we further confirmed this excitatory MECCCK-SUB projections using the pharmacological method. CNQX and APV are the AMPA and NMDA receptor antagonist, respectively19. The blue light evoked fEPSPs was almost diminished after infusion of CNQX (20 μM) and APV (100 μM; Fig. 3K, L; Paired two samples T- test; df = 5.0, t = 5.22, Before: 100.00 ± 18.37% vs After: 7.31 ± 0.66%, p = 0.003), suggesting that the glutamate components dominate the MECCCK-SUB circuits in the CCK Cre mice.

A Schematic diagram of virus injection. AAV9-CamKIIα-FLEX-re [Chronos-GFP] (5.0 E + 12 vg/ml, 300 nl) was injected into area MEC of CCK Cre mice. B Viral expression in the MEC area (left), scale bar: 1000 µm; A magnified view of the square area, right (1; scale bar, 50 μm). C MECCCK-SUB projections in the pCA1 and dSub area, scale bar: 1000 µm. D Co-immunofluorescent staining of Cre-dependent excitatory AAV-GFP with the anti-proCCK in MEC area of CCK-Cre mice (n = 9 slices of 3 mice). Scale bars,100 µm. E Bar chart displaying the percentage of excitatory GFP-labeled MECCCK neurons in pro-CCK positive neurons. F Schematic of the location of the stimulation fiber and recording electrodes. Blue light was delivered via the 200 μm optical fiber above the dSub area. G A representative input-output (I-O) curve showing the fEPSPs initial slopes corresponding to the light intensities. Scale, 0.5 mV by 20 ms. H The protocol of light TBS (L-TBS) for activating the Chronos expressing MECCCK-dSUB pathway of the CCK-Cre mice. Scale, 0.5 mV by 20 ms. I Normalized L-fEPSPs in the MECCCK-dSUB projections before and after 473 nm light TBS (N = 5 animals, n = 10 recording sites). Scale, 0.5 mV by 20 ms. J Quantitative data analysis for the L-fEPSP before and after manipulating L-TBS. K Representative L-fEPSP of MECCCK-dSUB projections by light stimulation before and after application of CNQX + APV. Scale, 0.2 mV by 20 msec. L Quantitative analysis of the glutamatergic transmission in MECCCK-SUB projections (N = 3 animals, n = 6 recording sites). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns not significant. Data are reported as mean ± SEM.

Robust LTP was induced by simultaneous activation of CA1-SUB inputs and MECCCK-SUB projections

Previous study shows that the co-activation of two different presynaptic inputs can induce a robust and persistent heterosynaptic long-term potentiation (hetero-LTP) in the postsynaptic neurons of the CA130. Considering that SUB PNs primarily receive neuronal inputs from the CA1 and MEC in the entorhinal-hippocampus network, we thus investigated whether specific co-activation of these presynaptic afferents could also elicit hetero-LTP in the SUB. To achieve this, we injected AAV9-mCamKIIa-ChrimsonR-mCherry and AAV9-hSyn-CaMKIIa-Flex-Chronos-GFP into the CA1 and MEC areas of CCK-Cre mice, specifically targeting the CA1-SUB projections and MEC-SUB terminals, respectively (Fig. 4A). After 4 weeks for both AAV expressions, we observed that both the CA1 PNs and MECCCK neurons convey strong projections in the dSUB area (Fig. 4B, C). For the two-channel-rhodopsin experiment, we utilized two-color light to activate these two projections expressing light-sensitive rhodopsins (Fig. 4D). We examined the cross-excitation between the ChrimsonR and Chronos expressing projections by red vs. blue light. The power of 473 nm wavelength for activation of Chronos exceeds 3.70 mW, which has a significant effect on the ChrimsonR. Therefore, the maximum power of the 473 nm light was limited to under 3.70 mW during the dual-color light-TBS (DL-TBS) protocols. Besides, the maximum power of red light for activation of ChrimsonR exhibited no effect on Chronos in our electrophysiology setup (Fig. 4E). Next, after the baseline of the CA1-SUB inputs was stably obtained for 20 min, DL-TBS was given to the recording region (Fig. 4F), and this manipulation significantly potentiated the L-fEPSPs and formed robust and persistent hetero-LTP in the CA1-SUB projections (red dots; Fig. 4G, H; Two way mixed ANOVA, Bonferrori adjustment; F2,27 = 16.33, p < 0.001; Pre 101.91 ± 0.76% vs Post 186.26 ± 19.42%, p < 0.001). Moreover, we noticed that hetero-LTP can be obtained from all array channels in the SUB region that receive responses from two light-evoked fEPSP signals.

A Viral injections were delivered to the pCA1 and MEC area of CCK Cre mice (pCA1: 6.50 E + 12 vg/ml, 200 nl; MEC: 6.15E + 12 vg/ml, 300 nl in each of two sites). B Viral expression in the pCA1 and MEC area. Green: Chronos-GFP expressed in MEC-dSUB projections. Red: ChrimsonR-Td protein expressed in the pCA1 neurons and their pCA1-dSUB projections (scale bar, 1,000 µm). C Viral expression in the pCA1area (1, scale bar: 100 µm); A magnified view of the square area (2; scale bar, 100 μm). D Two color - light for activation of both pCA1-dSUB projections and MECCCK-dSUB projections in the dSub area of the CCK-Cre mice. E Laser power determination of 473 nm and 635 nm to prevent cross-talk between the Chronos and ChrimsonR. Slices with either ChrimsonR expressing pCA1 area or Chronos expressing MEC area were prepared. 473 nm and 635 nm laser were both applied to stimulate their projections in the dSub area, and their corresponding L-fEPSPs were recorded. To minimize the non-specific activation, the maximum power of the 473 nm laser was controlled under 3.70 mW (arrow). F Two color L-TBS for simultaneous activation of pCA1-dSUB projections and MECCCK-dSUB projections. G Normalized slopes of L-fEPSPs of pCA1-dSUB projections responding to 635 nm light stimulation before and after two color L-TBS (Red dots). Normalized slopes of L-fEPSP of MEC-dSUB projections responding to 473 nm light stimulation before and after two color L-TBS (Green triangle). Normalized slopes of L-fEPSP of pCA1-dSUB projections responding to 635 nm light stimulation before and after two color L-TBS with perfusion of APV (Red dots); N = 5 animals, n = 10 recording sites in three groups. Scale, 0.2 mV by 20 msec. H Comparison of L-fEPSPs before and after different manipulations. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns not significant. Data are reported as mean ± SEM.

Additionally, we also delivered blue light to activate the MECCCK-SUB inputs and recorded the stable baseline of the L-fEPSPs for 20 min, while no obvious LTP was formed by the DL-TBS protocol (Pre 98.61 ± 1.02% vs Post 99.33 ± 3.82%, p = 0.95; Post MEC-SUB vs Post CA1-SUB, p < 0.001). Indicating that different dynamics exists between MECCCK-SUB and CA1-SUB pathways in the dSUB region, the latter projections can form hetero LTP with high-frequency light stimulation. Furthermore, it is well known that the electrical TBS or HFS-induced LTP was majorly controlled by the postsynaptic NMDA receptors5,29, which prompts us to examine if this kind of hetero-LTP was mediated by the NMDAR. Intriguingly, no significant LTP was generated by the two-color TBS protocol after perfusion of the NMDAR antagonist (100 µM APV; Pre 100.84 ± 0.31% vs Post 106.52 ± 2.50%, p = 0.63; Post NMDA vs Post CA1-SUB, p < 0.001), which hints light- evoked hetero-LTP was mediated by the NMDAR and might share a similar cellular mechanism with the E-TBS induced LTP.

Light-TBS triggers the CCK release from the MECCCK-SUB terminals

Our previous works demonstrated that hetero-LTP can be elicited when presynaptic projections and postsynaptic neurons are activated with the secretion of CCK from the CCK-ergic inputs28,29. In this study, we assumed that presynaptic components and postsynaptic SUB PNs were activated by DL-TBS along with releasing CCK from the terminals of MECCCK-SUB projections. Therefore, to verify whether the release of CCK can be triggered with high frequency light stimulation, we utilized the G protein-coupled receptor activation-based CCK sensor (AAV9-hSyn-CCK3.0-GFP) that can effectively monitor CCK secretion with high spatiotemporal resolution31. Briefly, extramembrane CCK combines the transmembrane CCK-BR receptor that causes conformational changes and increases the fluorescent intensity of the coupled protein (Fig. 5A). Therefore, we injected the AAV9-hSyn-CCK3.0-GFP and AAV9-mCaMKIIα-Flex-ChrimsonR-mCherry into the SUB and MEC region of the CCK-Cre mice respectively (Fig. 5B). After 4 weeks of AAVs expression, a robust expression of CCK sensor was detected in the SUB region. Concurrently, MECCCK neurons and its projections were also clearly labeled with ChrimsonR-mCherry (Fig. 5C, D). To reduce the behavioral effects on the fluorescent change, mice were fully anesthetized during the signal recording of the CCK sensor and controls. When stable baseline of CCK sensor was recorded, RL-TBS was given to the ChrimsonR-mCherry labeled MECCCK projections (Fig. 5E). Interestingly, increasing trend in fluorescent intensity of CCK sensor was observed in SUB region (Fig. 5F), and significant changes in Δ F/F were analyzed before and after the RL-TBS, while there was no obvious change in the control mice (Fig. 5G; Paired samples t-test, df = 6.0, t = −5.98; Δ F/F GFP: 0.02 ± 0.16% vs Δ F/F CCK Sensor 2.24 ± 0.37%, p = 0.001), implying CCK is released from the CCK vesicles in the MECCCK-SUB terminals by the high-frequency light stimulation. Intriguingly, the activity of the CCK sensor remains elevated for a prolonged period following the L-TBS protocol. This phenomenon may be attributed to the slow decay properties of the CCK-BR in the post-synaptic membrane32. Compare to classic neurotransmitters like the glutamate (Glu), several neuronal neuromodulators are released slowly via different mechanisms to regulate pre/ postsynaptic activity and reveal a significant delay in responding with their corresponding receptors1. This result is similar to our previous observations showing that high frequency light stimulation of CCK-positive neurons elicited CCK release in the auditory cortex and amygdala28,33. As previously mentioned in an earlier study34, the establishment of hetero-synaptic long-term plasticity relies on the concurrent activation of inputs from the CA1-SUB projections, CCK-positive projections, and endogenous CCK released from the post-synaptic terminals during the L-TBS period.

A Schematic depicting the neurological principle of the CCK sensor (consisting of the CCK BR and cpGFP). Ligand binding activates the sensor and then induces a change in fluorescence. B Schematic diagram showing injection of AAV9-hSyn-CCK sensor 2.3 (5.75E + 12 vg/ ml, 200 nl) and AAV9-CamKIIα-DIO-ChrimsonR-mCherry (5.65 E + 12 vg/ ml, 300 nl in each of two sites) into the SUB and MEC area, followed by laser stimulation and photometry recording. C CCK sensor expression in the SUB area around fiber tip (Left: scale bar: 1000 µm; right: scale bar: 200 µm), and ChrimsonR expressing CCK+ terminals in the SUB area of CCK-Cre mice. D ChrimsonR expressing CCK+ neurons in the MEC area (Left: scale bar: 1000 µm) and magnified image (Right: scale bar: 200 µm). E Hypothetical model depicting the neuronal activity-dependent CCK release from MEC pre-synapse in the SUB area. CCK is released and diffused from the presynaptic membrane to regulate postsynaptic activity. F Averaged fluorescence increases in response to optogenetic stimulation (635 nm L-TBS; N = 3 animals, n = 7 recording sites in two groups). G Quantification of averaged fluorescence in the CCK-Cre mice (averaged the Δ F/F after L-TBS within 100 s). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns not significant. Data are reported as mean ± SEM.

Synaptic plasticity of CA1-SUB projection was attenuated in the CCK gene knockout mice

The above experiments reveal that the entorhinal CCK plays an important role in neuronal plasticity in the CA1-SUB projections of the CCK-Cre mice. It would be interesting to investigate the plasticity of CA1-SUB pathway if the CCK gene was deleted from the brain. Thus, we utilized the CCK KO mice and the wild-type mice to examine the role of CCK in the CA1-SUB pathway. The genotype of these two mice was confirmed by the PCR analysis of tail DNA (Fig. 6A). For the electrophysiological recording in vitro, the sagittal brain slice was used to record the fEPSPs in the CA1-SUB projections of the CCK-KO mice and wild-type (WT) mice, respectively (Fig. 6B). The slope of the fESPSs exhibits a gradual increase with enhancing the intensity of the electrical stimulus (Fig. 6C). After a stable baseline was obtained by the electrical stimulation, then the E-TBS protocol was introduced to the stimulation electrode (Fig. 6D; Each burst includes five 0.5 ms pulses at 100 Hz, and each trial consists of 10 bursts at 5 Hz, for a total of 4 trains with an inter-block interval of 20 s19. Intriguingly, a robust and persistent LTP was elicited in the WT mice, while no obvious LTP was generated in the CCK-KO mice (Fig. 6E, F; Two way mixed ANOVA, Bonferrori adjustment; F1,18 = 45.18, p < 0.001; C57: Pre 101.44 ± 0.35% vs Post 147.10 ± 5.81%, p < 0.001; CCK-KO: Pre 101.20 ± 0.84% vs Post 108.00 ± 5.56%, p = 0.79; PostC57 vs PostCCK-KO; p < 0.001). Additionally, we did not observe differences in the amplitude of the evoked fEPSPs in CCK-KO mice and WT mice, indicating that deletion of the CCK gene likely did not change the basic synaptic transmission. These results suggest that endogenous CCK is an important neuronal chemical to support LTP formation in the CA1-SUB projection.

A Representative gel image for genotyping of animals before in-vitro recordings. B Schematic drawing of the brain slice recording in the CA1-SUB pathway. C A representative input-output (I-O) curve showing the fEPSPs initial slopes corresponding to the electrical intensities. Scale, 0.5 mV by 10 ms. D The protocol of electrical theta burst stimulation. Scale, 0.2 mV by 10 ms. E LTP was attenuated in the CCK-KO mice (N = 5, n = 11 recording sites) compared to controls (WT mice; N = 5, n = 9 recording sites). Scale, 0.2 mV by 10 ms. F Quantitative data analysis for the E-fEPSPs between the experimental group and controls. G The distribution profile of CCK-BR in the SUB (1, scale bar: 1000 µm). H An enlargement of the square area (2, scale bar: 200 µm). White triangles represent the signals of CCK-BR antibody in the SUB. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns not significant. Data are reported as mean ± SEM.

CCK-A receptor (CCK-AR) and CCK-B receptor (CCK-BR) are the two key receptors mediating the function of CCK35. CCK-BR is primarily expressed in the central nervous system (CNS), while CCK-AR majorly exist in the gastrointestinal system36. By using the IHC method, CCK BR was revealed to be widely distributed in the SUB region (Fig. 6G, H). These results imply that CCK modulates the neurobiological functions of CA1-SUB projections and this is likely mediated by the CCK-BR in the SUB region. Notably, recent studies have demonstrated that CCK analogues can effectively ameliorate Alzheimer’s disease in animal models by activating the CCK-BR-mediated signaling pathway in the hippocampus37. This activation can lead to improvements in synaptic components, cognition and memory, and protein pathway activation38. Additionally, endogenous CCK receptors (CCK-Rs) regulate the physiological levels of nigrostriatal and mesolimbic dopamine pathways, further controlling dopamine production and influencing the development of Parkinson’s disease24. These insightful investigations suggest that CCK receptor-modulating drugs could be promising therapeutic targets for the treatment of neurological diseases.

MECCCK neurons convey place-navigation to the SUB region

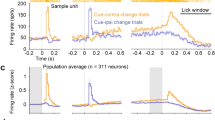

The subiculum is an output component of the hippocampus to the neocortex, and plays a vital role in processing spatial information. The object location task (OLT) has been widely used to explore the neural mechanisms that underlie spatial learning39. We thus utilized this paradigm to investigate the behavioral role of entorhinal CCK in SUB region (Fig. 7A). We injected the retrograde AAV-hSyn-Flex-GCamp7s into the dSUB of CCK-Cre mice to specifically label the SUB-projecting MECCCK neurons. After 4 weeks of AAV expression, virus-labeled neurons were majorly seen in layer II/III of the MEC region in CCK-Cre mice (Fig. 7B), which is consistent with previous findings that both layers of the MEC provide direct inputs to the SUB region13. The animals spent comparable time on exploring the two objects during the training period, while more time was occupied in exploring the object which was placed in the novel place (O2”) compared to the familiar one (Fig. 7C; Two way mixed ANOVA (repeated- measures), Bonferrori adjustment; F1,10 = 0.78, p = 0.39; Training: O1 7.00 ± 3.61 s vs O2 7.40 ± 2.53 s, p = 0.81; Testing, O1 5.58 ± 0.88 s vs O2” 7.85 ± 2.13 s, p = 0.03). Concurrently, we recorded the population Gcamp signals in the MEC region of the CCK-Cre mice during the object-place learning (Fig. 7D). Interestingly, we observed a quick and temporary increase in population Gcamp signals when animals executed the explorative events. We chose to score object exploration whenever the animal touched or sniffed the object40 and aligned the Ca2+ response to the onset of each explorative event and exhibited that activity of the SUB-projecting MECCCK neurons significantly increased during the object-exploration (Fig. 7E, F; Two way mixed ANOVA (repeated- measures), Bonferrori adjustment; F1,10 = 0.02, p = 0.88; Training: O1 1.01 ± 0.17% vs O2 1.13 ± 0.21%, p = 0.90; Testing, O1 1.13 ± 0.37% vs O2” 1.17 ± 0.16%, p = 0.74). Additionally, we observed that the activities of MECCCK neurons maintained a relatively high level in exploring the object in novel site compared with familiar ones (O1 1.16 ± 0.29% vs O2” 1.58 ± 0.64% in the last second), suggesting MECCCK neurons convey a robust novelty signal of place-navigation to SUB. Collectively, these results reveal an important neuromodulatory role of entorhinal CCK in the SUB region and its learning behaviors.

A Schema of the novel location task in this study. B Viral infection in the dSub area (upper: scale bar, 1000 μm) and the retrogradely labeled CCK+ neurons (bottom: scale bar, 200 μm) in the MEC of CCK-Cre mice (AAV Retro-syn-FLEX-GCamp7s-GFP, 5.00 E + 12 vg/ml, 200 nl). C The mice exhibited significantly more interactions with the newly placed object compared to the familiar object. D Heatmap shows the Δ F/F average traces from a single subject in the training and testing phase. E The Δ F/F average traces from all subject animals (N = 6 mice), aligned to the time of object interaction. F Group summary of GCaMP7s signals of dSUB-projecting MECCCK neurons during the object exploration in training and testing trial. G Verification of viral expression in the MEC area (left) and CCK+ terminals in the SUB area (right). Scale bar, 1000 μm. H 200 nl CTB-488 was delivered into the SUB region to mimic the diffusion profile of CNO in vivo. Scale bar: 500 µm. I Disturbance of the MECCCK-SUB projections impaired the capability of distinguish the difference between novel placed object and familiar object. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns not significant. Data are reported as mean ± SEM.

To further investigate the involvement of MEC-SUB projections in modulating the memory-guided task, we employed a chemogenetic tool to specifically inhibit the SUB-projecting neurons during the object-location task (Fig. 7G). A neuroanatomical tracer, cholera toxin subunit B (CTB-488), was used to mimic the diffusion profile of clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) within the SUB region. The delivery of 200 nL CTB was limited to the SUB region (Fig. 7H). Notably, CCK-Cre mice expressing AAV9-CamkIIα-DIO-HM4D (Gi)-mCherry and subjected to CNO (10 µM, 200 nL) administration failed to distinguish between the novel and familiar object locations during the test phase, contrasting with the control group (only expressing mCherry) (Fig. 7I; Two sample T-Test; t = 2.5, df = 18, DI Ctrl = 0.21 ± 0.07; DI HM4D(Gi) = −0.03 ± 0.06, p = 0.02). This outcome strongly suggests that the neural activity of the SUB-projecting MECCCK neurons is essential for successful completion of the memory-guided task.

Discussion

In the current study, we showed that entorhinal CCK effectively modulates the excitatory synaptic transmission in the CA1-dSUB projections through the CCK-BR in the wild-type mice. This finding is consistent with previous studies revealing exogenous CCK enhances the neuroplasticity in the hippocampal proper via the CCK-BR41. Additionally, CCK-AR is also widely distributed in the SUB regions42, hinting that CCK-AR might be involved in modulating the neurological functions in the SUB area. However, the coordinate mechanism between the CCK-AR and CCK-BR in the CA1-SUB projections needs further investigation. Besides, it is worth noticing that red and blue light- evoked population spikes and fEPSPs exhibit obvious attenuation during manipulation of the L-TBS protocol on the opsin expressing CA1-SUB projections compared to that in the electrical-TBS. This phenomenon may cause inefficient membrane depolarizations for the LTP induction both in CA1-SUB projections and MEC- SUB inputs by the high-frequency light stimulation. Previous reports have shown that light-evoked synaptic responses often exhibit artificial synaptic depression in the hippocampus and amygdala43,44. However, the mechanism underlying this phenomenon remains unknown, and further investigation is required. For instance, one approach to consider is optimizing the kinetic capabilities of chR2 to enable high-frequency light stimulation. Additionally, conducting whole-patch recordings or in vivo recordings under identical conditions could provide further validation of how light-TBS influences neuroplasticity in the CA1-SUB pathway. In the entorhinal -hippocampal system, SUB PNs majorly receive the neural inputs from the CA1 PNs and EC neurons. Our research further revealed that MEC neurons provide substantial excitatory CCK+ inputs to the dSUB region in CCK-Cre mice. These observations were similar with our previous works showing auditory receive most of excitatory ECCCK neural projection compared to other brain regions28,33.

Classic electrical stimulation (ES) can activate non-specific neuronal components in the stimulation site45, resulting in a compromised conclusion for the results of the experiment. For instance, ES stimulates/inhibits the presynaptic axons in all neuron types (excitatory and inhibitory) that are located around the electrode site. Nevertheless, well-established optogenetics protocol provides a high spatial, temporal, and neuron-specific activation in the central nervous system46. Previous studies have demonstrated that CCK-ergic projections from the EC facilitate the heterosynaptic LTP formation in the auditory cortex and amygdala region, and further facilitate the associative memory and fear trace memory formation, respectively28,29. Thus, we utilized Syn-ChrimsonR and DIO-Chronos to infect the CA1-SUB projections and MECCCK-SUB inputs. Interestingly, simultaneous activation of both opsins-expressing projections elicits a robust and persistent hetero-LTP by DL- TBS of both projections, and this novel type of LTP was majorly controlled by the NMDA receptors. An earlier study showed that high-frequency stimulation of two kinds of neuronal input induces heterosynaptic long-term synaptic plasticity in the CA1 area of the dorsal hippocampus30. An important cellular mechanism for this phenomenon is a large plateau potential produced by functional interactions between the shaffer collateral (SC) and perforant pathways (PP) in the CA1 region. Recently, Wong et al. reported that genetic depletion of the GluN1 components of presynaptic NMDA receptors in MECCCK-CA1 terminals could largely attenuate the axonal Ca2+ increment and affect the CCK release at the synaptic terminals47, hinting that presynaptic NMDA receptors control the release of CCK that induces heterosynaptic LTP. Intriguingly, Wozny et al. utilized whole-cell patch clamp recordings and depolarizing current injection, they found that paired-pulse facilitation showed that the site of LTP generation was postsynaptic in regular firing neurons, while presynaptic in burst firing neurons. This manipulation might significantly depolarize the post-synaptic neurons, and effectively elicited the LTP compare to the optogenetic stimulations in our study48. In another study, Cembrowski et al. elucidated that SUB pyramidal neurons (PNs) are divisible into proximal and distal subclasses, and these subclasses revealed different neurobiological functions at electrophysiological and behavioral levels49. For instance, both of regular spiking and bursting neurons were distributed in proximal-distal SUB, while distal SUB (dSUB) is selectively necessary for modulating spatial learning and memory. This is consistent with our findings, which demonstrate that the projections from the MEC to dSUB region play a role in modulating spatial-related behavioral performance.

Electrical high-frequency stimulation protocols possibly activate intra -and extra-subicular inputs, thus releasing other neuromodulators such as dopamine (DP), serotonin or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) which invariably modulate related behaviors. For instance, Glangetas et al. showed that high-frequency stimulation of ventral SUB promotes persistent hyperactivity of VTA dopamine neurons and regulates locomotor activity50. Similarly, Oleskevich et al. found that the SUB receives density of serotonergic afferents from raphe nuclei (RN), suggesting that the 5HT is an important modulator of SUB PNs51. Besides, Anders et al. demonstrated that activation of 5-HT2C receptors attenuates the bursting activities by inhibiting calcium current mediated by T-type Ca2+ channels in SUB PNs, and stimulation of the RN-SUB terminals decreases neural firing and the occurrence of epileptiform discharges52. Furthermore, Shor et al. revealed that cholinergic co-activation might be crucial for modulating the spatiotemporal pattern of Ca2+ signals required for neuroplasticity at CA1-SUB synapses53. Interestingly, Su et al. demonstrated that CCK sensor consistently monitored increases in CCK concentration in the dorsal hippocampus during exploration events19. This finding suggests that the release of endogenous CCK is involved in modulating behavioral performance. Thereby, it would be valuable to investigate how entorhinal CCK system interact with SUB to shape the synapse plasticity and modulate related-behavioral state.

Establishing a causal association between the neuronal activity in the SUB and navigation-related behaviors is crucial for understanding the influence of SUB-projecting MECCCK neurons on SUB. Our work revealed that the MECCCK neurons modulate CA1-SUB neural plasticity in a heterosynaptic manner. We showed that the activity of MECCCK projections to the dSUB region is required and sufficient to produce hetero-LTP in the CA1-dSUB projections. Besides, our results indicate that layer II/III MECCCK neurons may generally regulate the SUB state and neuroplasticity during behavioral exploration, this finding is in line with previous study showing that distal SUB majorly receives inputs from layer II/III neurons in the MEC, while LEC neurons project to the proximal SUB region13. Additionally, Qin et al. demonstrated that layer II MEC-DG neural inputs is required for spatial navigation11, and Bowler et al. showed that layer III MEC provides context/location-specific information to the hippocampal area CA154. Although these regions in the hippocampal proper are highly associated with environment exploration, different subfields that are tuned towards initial emergence, shifting, and stability of space show a distinct role in spatial memory processing and computation. Since we observed LTP deficiency in CCK KO mice, and MECCCK neurons densely innervate DG and CA1, therefore, MECCCK neurons likely modulate the NMDAR-dependent neuroplasticity in these hippocampal subfields. Finally, to systematically elucidate how the MECCCK neurons shape the intrahippocampal network and behaviors, further investigations are required to assess the neurological function of MECCCK neurons projecting to other hippocampal subregions.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. All experimental procedures obtained approval from the Animal Subjects Ethics Sub-Committee of the City University of Hong Kong.

Animals

In this study, we utilized adult (12 weeks) wild-type mice (C57BL/6J mice), CCK-Cre mice (Jackson lab stock #012706), and CCK-KO mice (Jackson lab stock# 012710). We exclusively used male mouse for conducting behavioral experiments and electrophysiological recording. All mice were kept under a controlled ambient condition with a dark and light cycle.

Viruses and antibodies

Taitool BioScience, Shanghai, China: AAV9-mCaMKIIa-DIO-ChrimsonR-mCherry-ER2-WPRE-pA (S0728-9); Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA: Retrograde-syn-FLEX-jGCaMP7s-WPRE (104491-AAVrg); Neurophotonics Center, Canada: AAV9-CamKIIα-FLEX-re [Chronos-GFP]; Vigene Biosciences Co., Ltd. China: AAV9-hSyn-CCK3.0-GFP; pAAV-CaMKIIa- DIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry; pAAV-CaMKIIa- DIO-mCherry.

Donkey-anti-rabbit-647 (Jackson Immuno Research, Cat# 711606152, RRID: AB_2340625); Anti-CCK BR (Thermo Fisher, Cat# PA3-201, RRID: AB_10979062); DAPI (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# sc-3598). Pro-CCK antibody (Frontier Institute, rabbit, RRID: AB_2571674).

AAV injection

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (Alfasan International B.V., Woerden, The Netherlands), Afterward, mice were fixed on a stereotactic instrument (RWD, China), then head skull of the mouse was cleaned and sterilized with 70% ethanol. To accurately locate the target brain region, the leveling of the mouse’ skull was adjusted and balanced by manual calibration via a digital device. To fully target the MEC area with AAV infection, two injection sites per hemisphere were determined for AAV injection. The microinjections were carried out by using a microinjector (World Precision Instruments, USA) and a glass pipette (World Precision Instruments, USA). For the CA1 coordinate: anteroposterior (AP), −1.75 mm from Bregma, mediolateral (ML), 1.35 mm, dorsoventral (DV), −1.25 mm from the brain surface: SUB: AP, −3.20 mm from Bregma, ML, 1.35 mm, DV, −1.80 mm from the brain surface. MEC, AP, −4.90 mm, ML, 3.0 mm, DV, −4.0/−3.5 mm. After the AAV injection, mouse’s skin was seamed with sterilized suture, and smeared with antibiotic ointment upon the incision to prevent bacterial infection and promote wound healing. Then, mice were placed into the heated blanked until the consciousness was recovered. Finally, mice were returned to the laboratory animals research unit for regular care.

Optogenetic manipulation and electrophysiological recording

In this study, mice were anaesthetized with 4% isoflurane and decapitated immediately. Brain was gently immersed in ice-cold (~0–4 °C) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) for 30 s, which contained 124 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1.25 mM KH2PO4, 1.25 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, and 10 mM D-glucose (saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, pH = 7.4). The excrescent region was removed with a sharp blade, and the target brain tissue was mounted on a 4% agar and transferred to the ice-cold stage of the microtome. Sagittal sections were cut into 300-μm-thick brain slices via a vibrating microtome (VT1200s, Leica, Germany), which were gently transferred into oxygenated ACSF and incubated for 2 h for recovery before conducting the electrophysiological recording and optogenetic manipulation.

The field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded using a 16-channel (2 × 8 alignment) microelectrode array probe/connectors system (MED64-Quad II, Panasonic Alpha-Med Sciences). Brain slice was carefully transferred into a microelectrode probe and the CA1-SUB region was positioned at the top of the electrode array via the optical microscopy. After the slice was settled, a fine-mesh anchor (Warner Instruments, Harvard) was carefully placed on the brain slice. Afterward, the microelectrode probe was connected to the connector and perfused with oxygenated ACSF at a rate of 2 mL/min using a peristaltic pump (Minipuls 3, Gilson). The electrophysiological recording temperature was maintained at 32 °C and electrical stimuli were outputted in biphasic constant current with a 0.2 ms width pulses. For the optogenetics manipulation, the laser generator (Inper, China) was connected to the MED system and the parameters of laser stimulation were controlled by the operation software of the laser machine.

In the experimental procedure, a stimulation fiber with a diameter of 200 µm was placed on the brain section expressing ChrimsonR or Chronos. A 2 ms light pulse was then delivered to evoke a typical light-evoked field excitatory post-synaptic potential (L-fEPSP). Subsequently, an input/output (I/O) curve was performed to assess the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) using the L-fEPSP slopes within the 10–90% range to quantify the responses, ensuring minimal contamination from population spikes. fEPSP slopes were normalized to the baseline mean, LTP amplitude was defined by the mean of fEPSPs recorded 50–60 min following induction55. The stimulation intensity for the baseline synaptic response recording was set at 40% of the saturation level, and the stimulation intensity for theta burst stimulation (TBS) was adjusted to elicit 80% of the saturated intensity56.

For electrical stimulation, one electrode was selected as the stimulating electrode, while the remaining channels were designated as recording electrodes. A 0.5 ms electrical pulse was applied to evoke a typical fEPSP (E-fEPSP). Then, an I/O curve was performed to measure LTP induction, utilizing the 10–90% range of E-fEPSP responses to quantify the results. The stimulation intensity for recording the baseline synaptic response was maintained at 40% of the saturation level, while the stimulation intensity for TBS was adjusted to elicit 80% of the saturated intensity.

To prepare the exogenous CCK-4 solution, we utilized a glass container filled with recording ACSF. The recording process was temporarily halted when the baseline of light-evoked fEPSP stabilized for a duration of 30 min. At this point, the CCK-4 solution was automatically administered into the multiple electrode array using a digitally controlled pump. After a five-minute period to ensure complete replacement of the ACSF with the CCK-4 solution, the brain sections underwent the light TBS (theta burst stimulation) protocol. Subsequently, the ACSF containing CCK-4 was removed and replaced with pure ACSF through perfusion. The fEPSP responses were continuously recorded for a minimum of 60 min following the TBS procedure.

Retrograde tracing

For retrograde labeling, 50 nl Cre-dependent AAV was injected into the SUB of the CCK-Cre mice (AP −3.2 mm, ML 1.35 mm and DV −1.8 mm). To quantify retrogradely labeled CCK-positive neurons, Cell counter plugin in Fiji was used in the analysis. For the calculation of cell in the various regions, the total number of manually identified GFP-labeled neurons divided by the area.

Sections (70 mm) with an interval of 420 mm were collected and mounted in an anterior to posterior order. Brain slice was scanned at 4× magnification (Ni-E, Tokyo, Japan) using the same laser intensity. Delineations of different brain areas were made according to the Allen Brain reference atlas, and Cell Counter plugin in Fiji was used to quantify retrogradely labeled neurons and DAPI number.

Optical fiber/cannular implantation and fiber-photometry recording

All the surgical procedures were described above. Once the AAV-Gcamp was injected into the subiculum area of the CCK-Cre mice. 200 µm optical fiber was prepared and fixed by the stereotactic apparatus, then the fiber was slowly inserted into the MEC area (20–50 um above the target region). Dental cement was used to cover the mouse’s skull and to fix the implanted fiber.

Drug cannulas (Guide cannula #62004, O.D. 0.41 mm; injector #62108, O.D. 0.21 mm, RWD Life Science; Shenzhen, China) were implanted in target locations (bilateral SUB areas: AP: −1.80 mm, DV: −1.60 mm; ML: +/−1.25 mm). The surgical procedures were same to those described above.

For the Ca2+ recording, we used the Fiber Photometry System (Doric Lenses Inc, Quebec, Canada) coupled with the RZ5D processor (TDT, Alachua, FL) in this study. Excitation light at 470 nm and 405 nm was generated from the LEDs (M470F3 and M405FP1, Thorlabs) and was sinusoidally modulated at 210 Hz and 330 Hz, respectively. The power of the excitation light was adjusted by the LED driver (LEDD1B, Thorlabs), and coupled with the RZ5D processor via the Synapse tool. Excitation light was emitted to the brain region via a dichroic mirror embedded in single fluorescence MiniCube (Doric Lenses, Quebec, QC, Canada) in a fiber-optic patch cord (200 μm, 0.37 NA, Inper, Hangzhou, China). The power of the excitation light was limited to 30 μW to elude the photobleaching effects. Then, the emission fluorescence was delivered through a bandpass filtered by a MiniCube device. Afterward, the calcium signal was collected and sequentially converted to an analog data through the photoreceiver (Doric Lenses). Lastly, the analog data was visualized by the RZ5D processor at 1 kHz with a 5 Hz low-pass filter and analyzed by Synapse tool in the recording system. For the data analysis, we utilized the pMAT tool in Matlab to calculate the Ca2+ signal data. Fluorescence change (ΔF/F) by calculating (F-F0)/F0, where F0 was the averaged baseline of the Ca2+ response before the explorative events.

Object location behavioral testing

We utilized 45 cm × 45 cm × 45 cm apparatus with geometric cues inside the wall to conduct the object location task for the experimental mice. Primarily, all mice were subjected to habituation task in the apparatus for 10 min on the first day. During training on day 2, all experimental mice were allowed to explore the two objects in different locations of the apparatus within 5 min. Afterward, each trained mouse was placed into the home cage for 1 h. Then, each mouse was replaced into the apparatus for 5 min in which one of the objects was moved to the novel site. Finally, the following formula was used to analyze the discrimination index (DI) for the behavioral task:

DI = (Time exploring the object in novel location − time on object in familiar location)/(Time exploring the object in novel location + time on object in familiar location).

Note: A positive DI value implies more time exploring the object in a novel site. A negative DI value means more time exploring the object in a familiar location.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were subjected to the intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium until fully anesthetized and perfused transcardially with 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% PFA solution (paraformaldehyde in 0.01 M PBS). Afterward, brains were extracted and immerged in 4% PFA for overnight. Brain tissues were fixed and sectioned at 50 µm thickness slices using a vibratome (Leica VT1000 S, Wetzlar, Germany). To verify AAV expression, brain sections were stained with DAPI solution (1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 5 min and mounted onto glass slides in 0.01 M PBS containing 70% glycerol (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

For the procedure of immunohistochemistry (IHC), brain sections were washed with 0.01 M PBS two times for 10 min each and reacted with blocking solution (10% goat serum and 0.2% Triton X-100 in 0.01 M PBS) at ambient temperature for 2 h. The primary antibody was diluted to the appropriate concentration in blocking solution and sequentially incubated with brain sections overnight in the incubation room at 4 °C. Then, brain sections were cleaned with 0.01 M PBS two times for 10 min each and stained with the secondary antibody (0.2% Triton X-100 in 0.01 MPBS) at appropriate concentration. The brain sections were incubated with secondary antibody at ambient temperature for 2–3 h. After the secondary incubation was completed, brain sections were washed with 0.01 M PBS two times for 10 min each and stained with DAPI solution for 5 min. Lastly, brain sections were mounted onto glass slides. Imaging was conducted via a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope (Zeiss, German).

Statistics and reproducibility

Group data are represented as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). Statistical analyses were conducted by SPSS 27 (IBM, Armonk, NY), including paired sample t-tests, and two-way mixed ANOVA, Figures were generated with Origin 2022 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) and cartoons were created in BioRender.com. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All raw data are available in the supplementary data file and are also available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. Numerical source data for all graphs in the manuscript can be seen in Supplementary Data File 1.

References

Chi, C. H., Yang, F. C. & Chang, Y. L. Age-related volumetric alterations in hippocampal subiculum region are associated with reduced retention of the “when” memory component. Brain Cogn. 160, 105877 (2022).

Ekstrom, A. D. & Hill, P. F. Spatial navigation and memory: A review of the similarities and differences relevant to brain models and age. Neuron 111, 1037–1049 (2023).

Frank, L. M., Brown, E. N. & Wilson, M. Trajectory Encoding in the Hippocampus and Entorhinal Cortex. Neuron 27, 169–178 (2000).

Dannenberg, H., Lazaro, H., Nambiar, P., Hoyland, A. & Hasselmo, M. E. Effects of visual inputs on neural dynamics for coding of location and running speed in medial entorhinal cortex. eLife 9, e62500 (2020).

Park, H., Popescu, A. & Poo, M. M. Essential Role of Presynaptic NMDA Receptors in Activity-Dependent BDNF Secretion and Corticostriatal LTP. Neuron 84, 1009–1022 (2014).

Oliva, A., Fernández-Ruiz, A., Fermino De Oliveira, E. & Buzsáki, G. Origin of Gamma Frequency Power during Hippocampal Sharp-Wave Ripples. Cell Rep. 25, 1693–1700.e4 (2018).

Nitzan, N., Swanson, R., Schmitz, D. & Buzsáki, G. Brain-wide interactions during hippocampal sharp wave ripples. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2200931119 (2022).

Lopez-Rojas, J., De Solis, C. A., Leroy, F., Kandel, E. R. & Siegelbaum, S. A. A direct lateral entorhinal cortex to hippocampal CA2 circuit conveys social information required for social memory. Neuron 110, 1559–1572.e4 (2022).

Baset, A. & Huang, F. Shedding light on subiculum’s role in human brain disorders. Brain Res. Bull. 214, 110993 (2024).

Nakai, S., Kitanishi, T. & Mizuseki, K. Distinct manifold encoding of navigational information in the subiculum and hippocampus. Sci. Adv. 10, eadi4471 (2024).

Qin, H. et al. A Visual-Cue-Dependent Memory Circuit for Place Navigation. Neuron 99, 47–55.e4 (2018).

Grienberger, C. & Magee, J. C. Entorhinal cortex directs learning-related changes in CA1 representations. Nature 611, 554–562 (2022).

Berns, D. S., DeNardo, L. A., Pederick, D. T. & Luo, L. Teneurin-3 controls topographic circuit assembly in the hippocampus. Nature 554, 328–333 (2018).

Huang, Y. Y. & Kandel, E. R. θ frequency stimulation up-regulates the synaptic strength of the pathway from CA1 to subiculum region of hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 232–237 (2005).

Imbrosci, B. et al. Subiculum as a generator of sharp wave-ripples in the rodent hippocampus. Cell Rep. 35, 109021 (2021).

Fei, F. et al. Discrete subicular circuits control generalization of hippocampal seizures. Nat. Commun. 13, 5010 (2022).

Bai, T. et al. Learning-prolonged maintenance of stimulus information in CA1 and subiculum during trace fear conditioning. Cell Rep. 42, 112853 (2023).

Huang, F., Bello, S. T., Baset, A., Chen, X. & He, J. Protocol for induction of heterosynaptic long-term potentiation in the mouse hippocampus via dual-opsin stimulation technique. STAR Protoc. 5, 102860 (2024).

Su, J. et al. Entorhinohippocampal cholecystokinin modulates spatial learning by facilitating neuroplasticity of hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapses. Cell Rep. 42, 113467 (2023).

Gunaydin, L. A. et al. Ultrafast optogenetic control. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 387–392 (2010).

Mous, S. et al. Dynamics and mechanism of a light-driven chloride pump. Science 375, 845–851 (2022).

Rehfeld, J. F. Cholecystokinin-From Local Gut Hormone to Ubiquitous Messenger. Front. Endocrinol. 8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00047 (2017).

Rehfeld, J. F. Cholecystokinin and Panic Disorder: Reflections on the History and Some Unsolved Questions. Molecules 26, 5657 (2021).

Reich, N. & Hölscher, C. Cholecystokinin (CCK): a neuromodulator with therapeutic potential in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 73, 101122 (2024).

Rehfeld, J. F. How to measure cholecystokinin in tissue, plasma and cerebrospinal fluid. Regul. Pept. 78, 31–39 (1998).

Sun, W. et al. Heterosynaptic plasticity of the visuo-auditory projection requires cholecystokinin released from entorhinal cortex afferents. eLife 13, e83356 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Cholecystokinin release triggered by NMDA receptors produces LTP and sound–sound associative memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 6397–6406 (2019).

Li, H. et al. Cholecystokinin facilitates motor skill learning by modulating neuroplasticity in the motor cortex. eLife 13, e83897 (2024).

Scimemi, A., Tian, H. & Diamond, J. S. Neuronal Transporters Regulate Glutamate Clearance, NMDA Receptor Activation, and Synaptic Plasticity in the Hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 29, 14581–14595 (2009).

Ahmed, M. S. & Siegelbaum, S. A. Recruitment of N-Type Ca2+ Channels during LTP Enhances Low Release Efficacy of Hippocampal CA1 Perforant Path Synapses. Neuron 63, 372–385 (2009).

Wang, H. et al. A tool kit of highly selective and sensitive genetically encoded neuropeptide sensors. Science 382, eabq8173 (2023).

Wu, Z. et al. Neuronal activity-induced, equilibrative nucleoside transporter-dependent, somatodendritic adenosine release revealed by a GRAB sensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2212387120 (2023).

Feng, H., Su, J., Fang, W., Chen, X. & He, J. The entorhinal cortex modulates trace fear memory formation and neuroplasticity in the mouse lateral amygdala via cholecystokinin. eLife 10, e69333 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Cholecystokinin from the entorhinal cortex enables neural plasticity in the auditory cortex. Cell Res. 24, 307–330 (2014).

Kim, K. S., Seeley, R. J. & Sandoval, D. A. Signalling from the periphery to the brain that regulates energy homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 185–196 (2018).

Dafalla, A. I., Mhalhal, T. R., Hiscocks, K., Heath, J. & Sayegh, A. I. Non-sulfated cholecystokinin-8 increases enteric and hindbrain Fos-like immunoreactivity in male Sprague Dawley rats. Brain Res. 1708, 200–206 (2019).

Zhang, N. et al. Cholecystokinin B receptor agonists alleviates anterograde amnesia in cholecystokinin-deficient and aged Alzheimer’s disease mice. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 16, 109 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Cholecystokinin Signaling can Rescue Cognition and Synaptic Plasticity in the APP/PS1 Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 60, 5067–5089 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. CA1-projecting subiculum neurons facilitate object–place learning. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 1857–1870 (2019).

Leger, M. et al. Object recognition test in mice. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2531–2537 (2013).

Yasui, M. & Kawasaki, K. CCKB-Receptor Activation Augments the Long-Term Potentiation in Guinea Pig Hippocampal Slices. Jpn J. Pharmacol. 68, 441–447 (1995).

Nishimura, S., et al. Functional Synergy between Cholecystokinin Receptors CCKAR and CCKBR in Mammalian Brain Development. PLOS ONE 10, e0124295 (2015).

Jackman, S. L., Beneduce, B. M., Drew, I. R. & Regehr, W. G. Achieving High-Frequency Optical Control of Synaptic Transmission. J. Neurosci. 34, 7704–7714 (2014).

Bazelot, M. et al. Hippocampal Theta Input to the Amygdala Shapes Feedforward Inhibition to Gate Heterosynaptic Plasticity. Neuron 87, 1290–1303 (2015).

Fontaine, A. K. et al. Optogenetic stimulation of cholinergic fibers for the modulation of insulin and glycemia. Sci. Rep. 11, 3670 (2021).

Zou, L. et al. Self-assembled multifunctional neural probes for precise integration of optogenetics and electrophysiology. Nat. Commun. 12, 5871 (2021).

Wong, Y., et al. Artificial fluorescent sensor reveals pre-synaptic NMDA receptors switch cholecystokinin release and LTP in the hippocampus. J. Neurochem. 168, 2621–2639 (2024).

Wozny, C., Maier, N., Schmitz, D. & Behr, J. Two different forms of long-term potentiation at CA1–subiculum synapses. J. Physiol. 586, 2725–2734 (2008).

Cembrowski, M. S. et al. Dissociable Structural and Functional Hippocampal Outputs via Distinct Subiculum Cell Classes. Cell 173, 1280–1292.e18 (2018).

Glangetas, C. et al. Ventral Subiculum Stimulation Promotes Persistent Hyperactivity of Dopamine Neurons and Facilitates Behavioral Effects of Cocaine. Cell Rep. 13, 2287–2296 (2015).

Oleskevich, S. & Descarries, L. Quantified distribution of the serotonin innervation in adult rat hippocampus. Neuroscience 34, 19–33 (1990).

Petersen, A. V., Jensen, C. S., Crépel, V., Falkerslev, M., Perrier, J. F. Serotonin Regulates the Firing of Principal Cells of the Subiculum by Inhibiting a T-type Ca2+ Current. Front. Cell Neurosci. 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2017.00060 (2017).

Shor, O. L., Fidzinski, P. & Behr, J. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and voltage-gated calcium channels contribute to bidirectional synaptic plasticity at CA1-subiculum synapses. Neurosci. Lett. 449, 220–223 (2009).

Bowler, J. C. & Losonczy, A. Direct cortical inputs to hippocampal area CA1 transmit complementary signals for goal-directed navigation. Neuron 111, 4071–4085.e6 (2023).

Yang, J. et al. proBDNF Negatively Regulates Neuronal Remodeling, Synaptic Transmission, and Synaptic Plasticity in Hippocampus. Cell Rep. 7, 796–806 (2014).

Li, X. et al. Interhemispheric cortical long-term potentiation in the auditory cortex requires heterosynaptic activation of entorhinal projection. iScience 26, 106542 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Hong Kong Research Grants Council, General Research Fund: 11103220 M, 11101521 M (GRF, JFH); Hong Kong Research Grants Council, Collaborative Research Fund: C1043-21GF(CRF, JFH); Innovation and Technology Fund: MRP/053/18X, GHP_075_19GD (ITF, JFH); Health and Medical Research Fund: 06172456, 09203656 (HMRF, XC, JFH). All cartoons are created with BioRender.com (https://app.biorender.com/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H. and F.H. designed and conceived this study. F.H. performed the experiments, collected and analyzed data. F.H., X.C., S.B., and A.B. contributed to data analysis and interpretation. F.H. wrote the paper and revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Christian Hölscher and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Benjamin Bessieres. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, F., Baset, A., Bello, S.T. et al. Cholecystokinin facilitates the formation of long-term heterosynaptic plasticity in the distal subiculum. Commun Biol 8, 153 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07597-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07597-9