Abstract

ER/PR+HER2- breast tumours are the most predominant subtype of breast cancer worldwide, including India. Unlike TNBCs, these tumours can be treated with anti-estrogens or aromatase inhibitors. Despite the success of endocrine therapy, a fraction of patients with ER/PR+ breast tumours do not respond to hormone-receptor-specific treatment and encounter disease recurrence contributing to their poor survival. The genomic underpinnings of therapy resistance in ER/PR+HER2- breast tumours are incompletely understood. We have performed whole genome sequencing (WGS) from tumour and normal tissue samples from endocrine-therapy resistant ER/PR+HER2- breast cancer patients who have relapsed on endocrine therapy and have conducted a comparative analysis of WGS data generated from tissues of endocrine therapy sensitive patients who remained free of disease during a minimum 5-year follow-up. Our analysis shows (a) a three-gene (PIK3CA-ESR1-TP53) resistance signature, and (b) impaired DNA double-strand break repair and homologous recombination pathways, were significantly associated with endocrine-therapy resistance and disease recurrence in ER/PR+HER2- tumours. Genome instability, contributing to high burden of copy-number, structural alterations and telomere-shortening identified as major markers of endocrine treatment resistance. Early prediction of endocrine-therapy resistance from the genomic landscape of breast tumours will aid therapeutics. Our finding also opens up the possibility of repurposing PARP inhibitors in treating endocrine therapy-resistant breast cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is a complex and heterogeneous disease with a reported incidence of 47.8 per 0.1 million women worldwide in 20201 and 46.8 in 20222 and in some rare instances, men1. Despite the decline in mortality of breast cancer patients due to early detection and better access to new drug molecules, it is still the most prevalent cancer in India with 178,361 new cases arising annually (as of 2020)1, accounting for 13.3% of all registered cancer cases. Breast cancer incidence and mortality rates vary widely across different regions, urban and rural areas, and socio-economic groups in India. Some factors influencing the risk of breast cancer in India are inherited germline genomic variants, reproductive history, obesity, physical activity, diet, alcohol consumption, tobacco use, other environmental factors, and access to screening and treatment facilities. Primarily based on the expression of estrogen receptor (ER, encoded by ESR1 gene), progesterone receptor (PR, encoded by PGR gene) and HER2 receptor (encoded by ERBB2 gene), breast cancer can be classified into three major categories, (a) hormone receptor-positive (ER/PR-positive), (b) HER2-positive, and (c) triple-negative (TNBC). Although the fraction of TNBC is higher in Indian breast cancer patients (~25–30%), ER/PR-positive breast cancer remains the most common subtype in our country (~50–60%)3,4,5. Unlike TNBC, most hormone-sensitive breast cancers respond to endocrine therapy, which includes anti-estrogens like tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors like, anastrozole, letrozole, etc.6,7 and generally show better survival8. Approximately 20–40% of all women diagnosed with primary breast cancer eventually develop recurrent/metastatic disease. Among ER-positive breast cancer patients, about 25% of those receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy develop recurrent/metastatic tumours9. A significant proportion of ER+ breast cancer patients eventually develop resistance to endocrine therapy and relapse10,11. ER-positive breast cancer patients who relapse due to endocrine therapy resistance account for a considerable fraction of deaths due to local recurrence (observed in 8–10%) and metastasis (11–30%)12. Substantially high molecular heterogeneity is observed among ER+HER2- breast tumours13. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms of relapse and endocrine therapy resistance in this sub-group of patients is critical for improving the outcome of patients with breast cancer. Over a decade, multiple studies14,15 have uncovered the mutational and transcriptional landscape of breast tumours including all major subtypes. Also, multiple initiatives5,16,17 have been taken to understand the genomic underpinnings of hormone-sensitive breast tumours to develop resistance to endocrine therapy. Studies have shown that (a) PIK3CA18 and ESR1 somatic mutations19,20,21,22,23, (b) ERBB3-EGFR signalling axis24, (c) AKT hotspot mutation25 to be associated with therapy resistance in hormone-positive breast cancers. Although these large-scale studies are primarily based on targeted sequencing, either from FFPE blocks or lack of paired tumour and normal tissue samples in some cases—which fails to capture genome-wide features that might contribute to therapy resistance.

We generated and analysed whole genome sequence (WGS) data from 40 prospectively sampled paired tumour and normal tissues from both (a) treatment-resistant (sampled from recurrent tumour), and (b) treatment-sensitive (sampled from treatment-naive primary tumour at diagnosis), ER/PR-positive HER2-negative breast cancer patients, who underwent endocrine therapy and were long-term followed up for at least 5 years at the Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India. Our study aimed to identify genomic factors that contribute to endocrine therapy resistance in ER/PR+HER2- breast cancer patients in India. Identification of genomic factors associated with treatment sensitivity may potentially prevent overtreatment of breast cancer patients.

Results

Oncogenic somatic mutations in PIK3CA, ESR1, and TP53 stratify endocrine therapy-resistant breast tumours that relapse

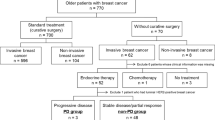

WGS data at about 73X median depth of coverage was generated from paired tumour and normal tissues of 40 ER/PR+, HER2- [Supplementary Table 1] breast cancer patients [20 endocrine treatment-sensitive primary tumour and 20 endocrine therapy-resistant recurrent tumour] [Fig. 1A] (raw data QC statistics are described in Supplementary Tables 2, 3). Focal somatic copy-number amplification of ESR1 (ER)/PGR (PR) was present in 32.5% and ERBB2 (HER2) deletion present in 27.5% tumours [Fig. 1A]. We have detected a total of 325,832 somatic mutations spanning the genome of these patient's tumours (median of 4901.5 per patient; range: 376–48,782), among which 2767 were nonsynonymous coding mutations (median of 40.5 per patient; range: 0–523) [see Supplementary Table 4 for details]. The median somatic mutation rate was determined to be 3.5 mutations per Mb of genome (range: 1.1–18.7/Mb). Treatment-sensitive primary and resistant recurrent tumours possessed median of 2605 (range: 376–20,506) and 7844 (390–48,782) somatic mutations, respectively. Between sensitive and resistant tumours, there was no statistically significant difference in (a) the mean number of (i) somatic mutations (p > 0.11, t-test) or (ii) nonsynonymous mutations (p = 0.14), or (b) the mutation rate (p > 0.32) [Fig. 1B, Fig. 2A and 2B]. We noted that, although not statistically significant, the average number of nonsynonymous mutations in the treatment-resistant group (93.5; median = 62) was greater than the sensitive group (45.3; median = 22); Supplementary Table 5. We detected nonsynonymous somatic mutations in previously known driver genes14,26,27, PIK3CA (27.5%), TP53 (27.5%), GATA3 (15%), ESR1 (10%), AKT1 (7.5%), RB1 (5%), AFF2 (7.5%), PTEN (7.5%), TBX3 (5%), CTCF (2.5%), PIK3R1 (2.5%), MAP3K1 (5%), CDH1 (5%) and NF1 (5%), in at least in 5% of patients [Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table 3]. Among these, ESR1 was significantly (p = 0.018, Chi-squared test) more frequently mutated among treatment-resistant (20%) compared to sensitive to treatment tumours (0%) and AKT1 was found to be significantly (p = 0.036, Chi-squared test) more frequently mutated among treatment-sensitive tumours (15%) compared to treatment-resistant tumours (0%) [Fig. 1B, and Supplementary Table 6]. TP53 was found to be mutated slightly more frequently among resistant (35%) as compared to the sensitive tumours (20%) although not statistically significant. 60% of sensitive and 75% of resistant tumours harboured at least one nonsynonymous mutation in the above-mentioned driver genes. We observed that, although there was no noticeable difference between PIK3CA mutation frequency between treatment-sensitive and resistant tumours, 66.7% (4 of 6) PIK3CA mutations in resistant were oncogenic (p.H1047R) whereas only 20% (1 of 5) was oncogenic among sensitive tumours [Patient P057S in sensitive group who harboured oncogenic p.H1047R5,28 PIK3CA mutation, also harboured another loss-of-function (LoF) mutations p.A1020E, possibly diminishing its oncogenic activity]. An oncogenic TP53 mutation (p.G245V29) was found in one patient of the therapy-resistant group; all other TP53 mutations found among sensitive or resistant tumours were LoF. ESR1 gene was found to be mutated only in the treatment-resistant group, and every patient in whom the gene was mutated harboured the p.Y537S30 hotspot mutation. Hotspot PIK3CA mutations, including p.H1047R5,28 and ESR1 mutation, particularly p.Y537S30, have been shown to be associated with the development of resistance to endocrine therapy16,17,30. On the other hand, AKT1 (p.E17K31 hotspot mutation) alteration was found only among the sensitive tumours. We observed that 40% of tumours (8 of 20) of the therapy-resistant group harboured oncogenic somatic mutations in PIK3CA, TP53 and ESR1 gene (either alone or in combination) which is significantly higher (p = 0.004) than among the sensitive group, 5% of patients (1 of 20 patients) [Fig. 1B].

A The top panel represents a 5-year clinical follow-up of patients showing local and distant metastasis status of endocrine therapy-sensitive and resistant breast cancer patients. The middle panel shows the rare germline alteration profiles of key DNA repair pathways among these patients. The bottom panel shows the somatic copy-number status [positive value for amplification and negative for deletion] of ER (ESR1), PR (PGR), HER2 (ERBB2) among these patients. B Somatic mutational landscape of therapy sensitive and resistant breast tumours describing numbers and characteristics of genome-wide and non-silent mutations, mutational status of known breast cancer driver genes [ms = missense, ns = nonsense, fsd = frameshift deletion, ifd = in frame deletion, fsi = frameshift insertion, spl = splice site mutations]. We have identified TP53-PIK3CA-ESR1 resistance signature to be associated with therapy resistance among these breast cancer patients. C The double-strand break repair (DSBR) failure mutational signature was found to be significantly higher among therapy-resistant recurrent breast tumours as compared to sensitive primary tumours. p53 signalling perturbation (TP53 mutation/≥2-copy deletion or MDM2 amplification), HDAC1 focal copy-number deletions and three homologous recombination (HR) repair pathway genes [POLD1, RAD54L and MUS81] were found to be significantly associated with endocrine therapy resistance.

The alteration profiles include, A genome-wide somatic mutational rate, B non-silent somatic mutational burden, C burdens of different types of structural variations (large deletions, duplications, inversion and translocations), D ratio of telomere length (in terms of log10 of tumour to normal (paired) telomere length), and E somatic copy-number burden landscape. Overall genome instability emerged as key signature of therapy resistance in ER/PR+HER2- breast tumours. The group-wise median for all types of genome alterations is shown individually for treatment-sensitive and resistant recurrent tumours.

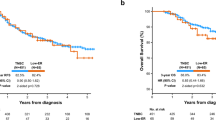

Further, we have assessed whether PIK3CA-TP53-ESR1 resistant signature found in our cohort is associated with recurrence (i.e., resistance to therapy) in the invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast in the TCGA study14,32. ER/PR-positive (Luminal-A and B) female breast cancer patients who have received endocrine therapy (Tamoxifen or Anastrazole) in the TCGA were stratified into two groups—(a) patients with PIK3CA-TP53-ESR1 resistant signature [having oncogenic mutations in PIK3CA (p.345K, p.E542K, p.E545K, p.H1047R, p.H1047L) and/or in TP53 (p.R175H, p.R245S, p.R245D, p.R248Q, p.R248W, p.R273H, p.R273C) and/or in ESR1 (p.Y537S)] (n = 84), and (b) with no presence of PIK3CA-TP53-ESR1 resistant signature [all of the remaining patients with wild-type/loss-of-function mutations of these genes] (n = 145). Presence of PIK3CA-TP53-ESR1 resistant signature significantly (p = 0.0136) increased the hazard ratio among patients in whom recurrence was observed within 5 years (2.483; 95% CI 1.206–5.111) even after jointly adjusting for other clinical covariates (age and tumour stage) [Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 7]. We also observed that AKT1 mutation (p.E17K) was only present in non-oncogenic group (5.5%); it was found only among therapy-sensitive tumours in the current study. These observations further support our finding on the association of PIK3CA-ESR1-TP53 oncogenic signature in treatment-resistant ER/PR+, HER2- breast tumours.

Double strand break repair (DSBR) failure emerges as a prominent feature in endocrine therapy-resistant breast tumours

Taking advantage of the WGS data, contributions of different mutagenic processes pertaining to specific somatic mutational signatures were estimated for endocrine therapy-sensitive and resistant patients. Utilising single nucleotide substitutions, we found COSMIC (version 2)33 signatures 1 (i.e., tumour ageing), 8 (unknown aetiology), 2 (APOBEC-activity), 3 (DNA double-strand break repair failure), 13 (APOBEC-activity), 16 (unknown), 5 (unknown), 9 (AID-activity) and 18 (unknown) in this cohort [Supplementary Fig. 2] by using the signal software package. Signature 3 which indicates failure of double strand break repair (DSBR) was detected in significantly (p < 0.03, Chi-squared test) frequently among endocrine therapy-resistant recurrent tumours (60%) than therapy sensitive tumours (30%). We also observed that Signature 9, which is associated with increased AID (activation-induced deaminase) activity, was present in a higher number of therapy-resistant tumours (25%) than sensitive (10%); however, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.1, Chi-squared test). APOBEC signature (Signatures 2 and 13 combined) was present in 17 tumours (8 sensitive and 9 resistant). An average of 39.31% (range: 6.06–88.20%) of somatic point mutations per patient contributed to the APOBEC signature. Signature 3 (DSBR failure) was detected in 18 tumours (6 sensitive and 12 resistant). An average of 27.18% (range: 6.0–47.17%) point mutations per patient was contributed by DSBR-failure signature [Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. 2]. It was known that DSBR-failure is expected to impact the somatic insertion-deletion (InDel) mutational pattern. We therefore reconstructed InDel signatures in treatment-sensitive and resistant patients through SignatureAnalyzer package using ‘COSMIC ID’ InDel reference signatures. Predefined InDel signatures ID4 (unknown), ID1 (replication slippage) and ID12 (unknown) were detected in treatment-sensitive tumours with cosine similarity of 0.58, 0.57 and 0.69 with reference-ID-signature; ID6 (DSBR failure), ID1 and ID12 (unknown) were detected in resistant tumours with cosine similarity 0.89, 0.54 and 0.7 with reference-ID-signatures. The InDel signature-ID6, which represents defective homologous recombination (HR) based DNA damage detected in the therapy-resistant group (with a high cosine similarity of 0.89 with the reference-ID-signature) but not in therapy-sensitive group of tumours, which is consistent with frequent DSBR failure identified from single nucleotide substitutions. The incidence of DSBR failure in breast tumours has been previously reported15. We analysed the WGS data for copy-number alteration signatures and found predefined signatures34 CX2, CX3 and CX5, which are associated with homologous recombination repair, combinedly contributed an average of 38% somatic CNAs in the therapy-resistant tumours (range: 9–60%) which is significantly (p = 0.01429 Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) higher than the average contribution of 25% (range: 0–55%) in the sensitive tumours [Supplementary Fig. 4]; this finding further validates that DSBR failure is associated with treatment resistance in ER/PR+HER2- breast tumours. Although the DSBR failure signature was frequent in therapy-resistant tumours, we found no significant difference in frequencies of rare germline alterations in HR DNA repair pathway among the two groups [see details in Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table 8]. On the other hand, three genes belonging to HR pathway—RAD54L, MUS81 and POLD1—were significantly (p < 0.01, Fisher’s exact test) frequently deleted (somatic copy number) among therapy-resistant tumours as compared to the sensitive group [Fig. 1C, Supplementary Table 9 and Supplementary Fig. 5]. Among 25 HR genes (curated from KEGG), an average of 22.4% genes were deleted among individual therapy-resistant tumours, which is significantly higher (p = 0.046, KS-test) than the tumours of the therapy-sensitive patients (12%) [Supplementary Fig. 5]. We found significant (p = 0.0003) correlation (Pearson’s coef. = 0.54) of presence of DSBR failure signature with p53 signalling perturbation (i.e., TP53 mutation or TP53 > 2 copy deletion, or MDM2 amplification) in the overall cohort [see Fig. 1C]. Interestingly, we found focal somatic copy-number deletion (1 copy) in HDAC1 (which encodes a chromatin-modifying enzyme and promotes DSBR) [Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. 3], to be significantly high (p = 0.0007, Chi-squared test) among therapy-resistant tumours (50%) compared to sensitive tumours (5%). The overall picture emerges as—(a) p53 pathway alteration, (b) copy-number deletion of HDAC1 and/or HR DNA repair pathway genes leading to DSBR failure—a marker for endocrine therapy resistance in ER/PR+HER2- breast tumours.

Genome instability pertaining to high copy-number alteration burden and structural alterations in therapy-resistant tumours correlates with DSBR failure signature

From WGS data, somatic arm-level and focal copy-number alterations were identified. We have detected significant arm-level amplification of 1q (q = 9.68 × 10−5) and deletions of 8p (q = 4.16 × 10−5), 11q (q = 0.0866), 13q (q = 0.003), 17p (q = 3.21 × 10−6) and 18q (q = 0.035) in the endocrine therapy-resistant ER/PR+HER2- recurrent tumours; among these 8q35, 11q36 and 18q37 arm-level deletions are previously implicated in breast tumours. Significant amplifications of 1q (q = 1.26 × 10−10) and 7p (q = 1.12 × 10−2) and deletions of 13q (q = 0.0344), 16p (q = 0.00919) and 17p (q = 0.00919) among patients sensitive to therapy were noted. We observed that 3011 genes (in 89 cytobands) were significantly (p < 0.05, Fisher’s exact test) frequently focally deleted in therapy-resistant tumours as compared to sensitive tumours, which includes ARID1A, CSMD2, ACOT7, HES2, HES3, TP73, HDAC1, CASP9 and MTOR and NF1. Many of these genes are involved in the regulation of cell proliferation38,39,40, DNA damage response38,41,42, chromatin modifications42, Notch-signalling43 and mTOR44 pathways which have previously been implicated in multiple cancer types. In addition, 443 genes (in 29 cytobands) were significantly (p < 0.05, Fisher’s exact test) frequently focally amplified in therapy-resistant patients as compared to therapy-sensitive patients, including CCND1, VMP1, PTRH2 and MIR21. These genes are previously found to have potential oncogenic functions45,46,47 in cancer development. The known breast cancer driver gene NF1 was found to be deleted in 50% treatment-resistant tumours, which is significantly (p < 0.048, Fisher’s exact test) higher than in the treatment-sensitive group in which it was deleted in 20% of patients. We have calculated copy-number alteration (CNA) burden—as proportion of genome amplified or deleted in each patient—and found that treatment-resistant tumours harboured significantly (p = 0.02, Wilcoxon rank sum test) higher CNA burden (median = 34.34%, range = 0.003–78.31%) than therapy sensitive tumours (median = 9.61%, range = 0.005–58.15%) [Fig. 2E]. The proportion of the genome amplified and deleted (computed individually) was significantly (p < 0.033, Wilcoxon rank sum test) higher in treatment-resistant tumours than among sensitive tumours [Supplementary Table 5]. Also, the total number of structural variants (SV) (considering inversion, and translocation) detected in endocrine therapy-resistant recurrent tumours (mean = 77.11) was significantly (p = 0.003, t-test) higher than in sensitive tumours (mean = 24.15) [Fig. 2C, Supplementary Table 5].

The total number of SVs found in all tumours was correlated (r = 0.686, p = 1.029E-06, Pearson correlation) with the CNA burden [Supplementary Fig. 6]. We observed that CNA burden was significantly higher (p < 0.01, Wilcoxon rank sum test) in tumours with DSBR failure mutational signature (mean = 32.77% genome altered) [which is predominantly found among therapy-resistant tumours] compared to tumours without the signature (mean = 18.31%) [Supplementary Fig. 6]. As the genomic instability—indicated by the high burden of copy-number alterations and structural alterations—emerged as major markers for therapy-resistant tumours, we further investigated the telomere length (TL-ratio of paired tumour-normal) in these breast cancer patients. With no surprise, we found “lower TL-ratio” (indicative of telomere shortening) in therapy-resistant tumours (median log10 TL-ratio = −0.064, range = −1.18 to 1.02) as compared to therapy-sensitive tumours (median = 0.01, range = −0.58 to 1.00) [Fig. 2D]. Through integrative analysis of the genome-wide SV and CNA data, we show that the number of chromothripsis48 (occurs from genome instability) events among the therapy-resistant tumours (mean = 6.7) were significantly (p = 0.002, t-test) higher than sensitive tumours (mean = 1.9) [Supplementary Fig. 7A and B] and it was significantly correlated with the p53 signalling perturbation (r = 0.738, p = 5.35E-08, Pearson correlation) as well as DSBR-failure mutational signature alteration (r = 0.646, p = 6.68E-06). Overall, we show several features of genome instability—(a) high burden of CNA and SV, (b) telomere shortening, (c) chromothripsis—in these tumours were correlated with DSBR failure that emerged as a key hallmark of endocrine therapy resistance.

Discussion

We have performed a comparative genomic profiling of ER/PR+HER2- breast cancer patients who showed resistance to endocrine therapy (tumour recurrence, metastasis, etc. within a follow-up period of 2 years after therapy) to endocrine therapy (Tamoxifen/Letrozole/Anastrozole; alone or in combination) with patients who had responded to the therapy from a minimum 5-year follow-up cohort. 39 of 40 patients were ER+, only one patient was found to be ER-PR+. By analysing whole genome sequence data generated on paired tumour (primary or recurrent) and normal tissue samples collected from each patient, we have identified—(a) a three-gene, TP53-PIK3CA-ESR1-resistance signature, and (b) impaired DNA double-strand break repair contributing to genome instability as a hallmark of endocrine therapy resistance and disease relapse in ER/PR-positive HER2- negative Indian breast cancer patients. The comprehensive summary of key molecular features associated with endocrine therapy resistance is presented with the time series relapse data for the therapy-resistant patients in Fig. 3. Among the 20 endocrine therapy-resistant patients who were provided a second round of endocrine therapy, we collected deep follow-up data for 9 individuals and found that 7 of them progressed or relapsed within a median time of 1.1 years (range: 0.5–7.2 years) after therapy (Table 1). The most frequent organs to which metastasis occurred among the therapy-resistant patients were bone (70%) and liver (55%). We noted that the mean age (at diagnosis) of endocrine therapy-resistant patients (44.05 years) who relapsed or progressed on therapy was significantly (p = 0.0005, t-test) lower than those who responded to therapy (sensitive patients, 54.10 years), which may be associated with an early onset of aggressive tumours.

The comprehensive time series data on disease relapse in endocrine therapy-resistant breast cancer patients is presented with associated key molecular features—oncogenic mutations, copy-number deletion of HDAC1 and HR pathway genes, p53 signalling perturbation, etc.—contributing to genome instability (DSBR failure, telomere shortening, etc.). The molecular data was generated from the first recurrent tumour for these therapy-resistant patients. The rare germline pathogenic alterations, if present in known susceptible genes, are indicated. Created in BioRender. Ghosh, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/i59t653.

We have not detected any somatic mutations in TERT-promoter region (up to 1000 bp upstream of transcription start site) among any of the patients. We found deleterious (predicted by SIFT, Polyphen2 and MutationTaster) rare germline alterations (AF < 0.001 in 1000Genomes populations and gnomAD AF < 0.001) in BRCA2, CDH1 and CHEK2 genes (among the widely known 11 breast cancer susceptibility genes by Wang et al.49) among 3 treatment-resistant [Fig. 3] and in BRCA2 in 1 treatment-sensitive patient (ID: P089S) [Supplementary Table 10].

There was no significant difference (p > 0.05, Chi-squared test) in proportions of patients having deleterious rare germline alterations in DNA repair pathways between the endocrine therapy-resistant and therapy-sensitive groups; the frequency of harbouring such germline alterations in base excision repair (BER) pathway was higher among the therapy-resistant patients (20%) than the sensitive patients (5%) [Supplementary Table 8]. Contrastingly, in somatic alteration landscape, we found the frequencies of copy-number deletions in three HR genes (POLD1, RAD54L and MUS81) were significantly greater in therapy-resistant tumours than sensitive tumours. We found BRCA2 to be deleted in 45% and 50% of the treatment-sensitive and resistant tumours, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5). Impaired DNA repair pathway has previously been associated with endocrine therapy resistance in hormone-positive breast cancer50. We also found one of the NHEJ repair pathway gene LIG4 to be significantly (p = 0.0421, Fisher’s exact test) more frequently deleted in resistant tumours (55%) than in sensitive tumours (30%). The therapy-resistant patients harboured frequent somatic copy-number deletion of the HDAC1 gene. HDAC1 plays a key role in histone deacetylation and was shown to participate in DNA damage repair42. We observed that 10 tumours (50%) in the therapy-resistant cohort harboured HDAC1 focal copy-number deletions among which DSBR failure (from somatic mutational signature analysis) was detected for 6 tumours. We also show a significant positive correlation between p53 signalling perturbation (through TP53 mutation or deep deletion or MDM2 amplification) with DSBR failure.

We were able to validate the three-gene resistance signature that we identified to be significantly associated with treatment resistance in our cohort using data from the TCGA cohort. The PIK3CA oncogenic hotspot mutations have been previously associated with endocrine therapy sensitivity in breast cancer patients18. The ESR1-Y537 ligand binding domain mutation has been functionally characterised and shown to be an activating mutation51 and previously found in endocrine therapy-resistant hormone-positive breast cancer patients52. We further utilised the paired gene expression data from TCGA and showed that infiltration of NK cells was ~6-fold lower (p < 0.015, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) among patients harbouring the resistance signature (mean infiltration = 0.05%) than among patients without this signature set of mutations (mean infiltration = 0.31%) [see immune cell deconvolution analysis results from TCGA in supplementary results]. Infiltration of anti-tumour immune cells (such as NK cells) has been previously associated with the prognosis of breast tumours53. In addition to identifying the three-gene resistance signature, our data also showed that failure of DSBR and concurrent genome instability is associated with endocrine therapy resistance in ER/PR+HER2- breast tumours. Preliminary insights drawn from the current study need to be replicated in larger Indian breast cancer cohorts in future.

We identify genome instability arising from (a) activation of oncogenic signalling and (b) somatic alteration in p53 and DNA double-strand break repair pathway as key hallmarks of endocrine therapy resistance in ER/PR+HER2- breast cancer patients who relapse. Various inhibitors targeting DNA repair defects, such as PARP inhibitors, are showing promising results in different cancers, including breast54, ovarian55, and prostate56, etc. This finding enables the opportunity to repurpose PARP inhibitors57 in therapy-resistant breast tumours.

Methods

Patient recruitment and sample collection

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Advanced Centre for Treatment, Research and Education in Cancer (ACTREC), India and registered in the Clinical Trials Registry—India (registration no. CTRI/2017/11/010553; registered on 17/11/2017) as previously described58. A patient was included in the study after obtaining written informed consent from her. Briefly, this was an ambispective study (prospective and retrospective) concerning sample and data collection. All patients in this study were histopathologically confirmed to have invasive breast cancer with ER and/or PR-positive and HER2-negative expression on immunohistochemistry (IHC) [Supplementary Table 1]. If IHC resulted in ambiguous determination of HER2 expression, confirmation was done using fluorescent in-situ hybridisation in cases. Patients with an absence of relapse for 2 years after initiating adjuvant or neo-adjuvant endocrine therapy (AI or Tamoxifen) were assigned to the sensitive cohort. Sensitive cohort patients whose primary tumour tissue was snap-frozen at the time of their diagnostic biopsy or surgical resection were included in this study. Patients were assigned to the endocrine therapy-resistant cohort if they had progressive disease (local or regional or distant) or relapsed disease (local or regional or distant) on any line of endocrine therapy (AI and/or tamoxifen and/or fulvestrant) within 2 years of therapy start. Tumour biospecimens from the first recurrence were preserved in RNAlater from the endocrine therapy-resistant cohort. In addition to these, patients with de-novo metastatic breast cancer who had progressed while on any line of endocrine therapy or within 3 months of completing a course of endocrine therapy (AI and/or tamoxifen and/or fulvestrant) were also assigned to the resistant cohort. Patients in the endocrine therapy-resistant cohort could have received chemotherapy prior to recruitment in the study.

These patients consented to undergo blood and buccal swab sampling to be used as normal tissue samples. Tumour tissue samples for these patients were obtained through the TMH tumour tissue repository. Briefly, 3–4 cores of fresh tumour biopsy were preserved in either RNAlater (Invitrogen) or All-protect (Qiagen) at 2–8 °C for 24 h followed by transfer to −80°C until further analysis. Finally, a random equal subset of (a) 20 endocrine therapy-sensitive, and (b) 20 endocrine therapy-resistant patients were chosen [described in Table 1] for WGS data generation from paired tumour and normal tissue (fresh-frozen) samples based on long-term follow-up data. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

Whole genome sequence data generation and detection of somatic and germline mutations and estimation of telomere length

High-quality DNA was isolated from 40-paired normal and tumour tissue samples, followed by determination of concentration and OD260/280 through NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) [OD exceeded 1.8 for each sample]. Paired-end 150bp WGS library (illumina TrueSeqNano) was prepared by multiplexing 40-paired samples and sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 at about 100X depth of coverage. The raw data QC was performed through FastQC (v 0.11.7)59 and multiqc (v 1.9)60 packages. Only high-quality (90% nucleotides with quality > 20 and < 5% N content) paired-end reads were included for WGS analysis. Reads containing sequencing adaptors were removed through trimmomatic (v 0.27)61. The filtered paired-end 150bp reads were aligned with GRCh37 (d5) human reference genome using BWA-MEM (v 0.7.17)62 [default parameters with –M and –T 1]. Duplicates were removed using PICARD63 (v 2.17.11) followed by local indel realignment and base quality score recalibration (utilising known SNP and InDels—1000Genomes, dbSNP.138, hapmap, Mills and 1000G gold standard indels included in GATK-bundle) using GATK (v 3.8)64. The aligned BAM files were further filtered to remove low-mapping-quality (< 40), unmapped, multi-mapped and reads that are not in proper pair using samtools (v 1.8)65. The BAM QC was performed using Qualimap (v 2.2.1)66 and coverage and insert-sizes were evaluated. The cross-sample contaminations were evaluated using GATK (v 4.0.11.0)64 CalculateContamination module (with gnomAD) to verify patient level concordance of tumour and normal samples. Germline variants were detected by joint genotyping of all 40 normal WGS by Haplotypecaller67 (GATK v 4.0.11.0). Somatic variants in all 40 tumours were identified by jointly analysing tumour-normal using Mutect2 caller (GATK v 4.0.11.0). Raw somatic variants were filtered for strand-biasness, homopolymer (variant base homopolymer > 5) and low-complexity regions (+50 bp reference sequence spanning the variant, mapped to multiple locations with > 98% sequence similarity using the ncbi-blast algorithm [v 2.7.1]). Further, high-confidence variants (depth in tumour > 10 and normal > 8, variant allele count > 3, variant allele frequency > 0.1) were selected for further analysis. Polymorphic germline loci (variant allele frequency > 0.01 in any of 1000Genomes68 and GenomeAsia100K69 populations) were removed from the list of somatic variants. Germline variants detected from the current cohort (joint genotyping of blood samples), i.e., panel-of-normal were further excluded from the somatic variants. Functional annotation for each somatic and germline variant was performed using Oncotator (v 1.9.9.0)67 with the latest available dataset. Further, nonsynonymous somatic mutations in pan-cancer driver genes were detected from this cohort and were manually verified through IGV visualisation by two independent informaticians. The somatic mutation rate for each tumour was determined by the MutSig2CV70 algorithm. The telomere length (TL) for paired tumour and normal samples was estimated through Computel (v 1.4)71 followed by TL-ratio computation as log10 of the ratio of telomere length of tumour and paired normal tissue as described by Barthel et al.72.

Detection of somatic copy-number alterations and structural variations from WGS data

To detect copy-number alteration (CNA), post alignment marked duplicate BAM files filtered for ‘MAPQ < 40’ and reads that are not in proper pair (using PICARD and samtools as described above). To carry out allele-specific somatic CNA detection, first, a panel-of-normal was formed from the normal samples and therefore, significantly amplified or deleted genome segments in tumour samples as compared to panel-of-normal were detected using the ascatNGS (v 4.4.1)73 package. Further, GISTIC (v 2.0.22)74 was used to detect tumour-specific significant focal and arm-level CNA events from sample-specific segments generated using ASCAT75. To sensitively and accurately delineate the genomic rearrangements (comprising inversions and translocation), the structural variation (SV) prediction algorithm DELLY (v 2)76 was used which utilises “paired-end split reads”. Further, the CNA and SV data were integrated through ShatterSeek48 algorithm to detect genome-wide chromothripsis events. The chromothripsis events were categorised into two buckets—(1) greater than or equal to 5 oscillations between two copy-number states within a chromothripsis region, and (2) less than 5 oscillations between two copy-number states within a chromothripsis region.

Detection of somatic mutational and copy alteration signatures

From the WGS data, somatic mutational signatures were detected using the algorithm encoded in the signal (v 2)77 package using single nucleotide changes [100 bootstraps and p < 0.05 for signature fitting]. The somatic mutational signatures based on tri-nucleotide context were fitted against the COSMIC (V2) reference signature, and the cosine similarity was determined to estimate the contributions of each detected signature in all 40 tumour tissues. The detected signatures were further validated using the orthogonal algorithm embedded in SignatureAnalyzer33. The indel signatures were detected using SignatureAnalyzer by computing cosine similarity with COSMIC-ID reference database. Further, the copy-number signatures from WGS data were extracted and estimated using SigProfileExtractor (v 1.1.4)78 package as described by Steele et al.34.

Survival analysis

To compare the 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) between oncogenic (resistant signature mutation present) and non-oncogenic groups of patients from the TCGA breast cancer cohort (as described in the “Results” section), Log-rank test was used. Using the Kaplan–Meier method, we have estimated the survival probability distribution for each group by utilising “survfit” module included with “survival” package in R (v 4.2.2). Further multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis (using “coxph” function) was performed along with clinical covariates, age, and pathological tumour stage to assess the significance of status of resistant signature mutations on 5-year PFS. We have considered Log-rank p < 0.05 to be statistically significant.

Tumour purity aware estimation of tumour infiltrating immune cells from gene expression data obtained from TCGA breast cancer cohort

Abundance of infiltrating immune cells (IIC) was analysed for TCGA breast tumours (included in the study) using CIBERSORTx79 (default parameters were used, additionally with 100 permutations) using LM22 reference signature matrix and gene expression data (TPM normalised). As overall tumour purity can have confounding effects on the estimation of absolute abundance of IIC types, we have first estimated the total immune infiltration using the ESTIMATE80 package and then only included the tumour’s positive immune score (i.e., immune infiltration present) while comparing abundance of IIC between groups of patients.

Statistics and reproducibility

The details of the sample collection and statistical analysis are described in appropriate subsections of the “Methods”. For statistical significance, we have considered a p-value < 0.05. Reproducibility of the analysis is ensured through depositing the raw data in the public domain (controlled access) and thorough description of the analytical methodology.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data is uploaded to Indian Biological Data Center (Indian Nucleotide Data Archive—Controlled Access) under controlled access (Accession ID: INCARP000300) due to patient privacy concerns.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024).

Nair, N. et al. Breast cancer in a tertiary cancer center in India—an audit, with outcome analysis. Indian J. Cancer 55, 16–22 (2018).

Kohler, B. A. et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2011, featuring incidence of breast cancer subtypes by race/ethnicity, poverty, and state. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 107, djv048 (2015).

Tolaney, S. M. et al. Clinical significance of PIK3CA and ESR1 mutations in circulating tumor DNA: analysis from the MONARCH 2 study of abemaciclib plus fulvestrant. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 1500–1506 (2022).

Fan, W., Chang, J. & Fu, P. Endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer: current status, possible mechanisms and overcoming strategies. Future Med. Chem. 7, 1511–1519 (2015).

Liu, S. et al. HER2 overexpression triggers an IL1a proinflammatory circuit to drive tumorigenesis and promote chemotherapy resistance. Cancer Res. 78, 2040–2051 (2018).

Chen, L., Linden, H. M., Anderson, B. O. & Li, C. I. Trends in 5-year survival rates among breast cancer patients by hormone receptor status and stage. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 147, 609–616 (2014).

Hongchao, P. et al. 20-year risks of breast-cancer recurrence after stopping endocrine therapy at 5 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 1836–1846 (2017).

Lei, J. T., Anurag, M., Haricharan, S., Gou, X. & Ellis, M. J. Endocrine therapy resistance: new insights. Breast 48, S26–S30 (2019).

Tolaney, S. M. et al. Overall survival and exploratory biomarker analyses of abemaciclib plus trastuzumab with or without fulvestrant versus trastuzumab plus chemotherapy in HR+, HER2+ metastatic breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 30, 39–49 (2024).

Bhattacharyya, G. S. et al. Overview of breast cancer and implications of overtreatment of early-stage breast cancer: an Indian perspective. JCO Glob. Oncol. 6, 789–798 (2020).

Selli, C., Dixon, J. M. & Sims, A. H. Accurate prediction of response to endocrine therapy in breast cancer patients: current and future biomarkers. Breast Cancer Res. 18, 118 (2016).

Koboldt, D. C. et al. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490, 61–70 (2012).

Nik-Zainal, S. et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature 534, 47–54 (2016).

Razavi, P. et al. The genomic landscape of endocrine-resistant advanced breast cancers. Cancer Cell 34, 427–438.e6 (2018).

Ahn, S. G. et al. Primary endocrine resistance of ER+ breast cancer with ESR1 mutations interrogated by droplet digital PCR. NPJ Breast Cancer 8, 58 (2022).

Schwartzberg, L. S. & Vidal, G. A. Targeting PIK3CA alterations in hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2–negative advanced breast cancer: new therapeutic approaches and practical considerations. Clin. Breast Cancer 20, e439–e449 (2020).

Oesterreich, S. & Davidson, N. E. The search for ESR1 mutations in breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 45, 1415–1416 (2013).

Toy, W. et al. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 45, 1439–1445 (2013).

Chandarlapaty, S. et al. Prevalence of ESR1 mutations in cell-free DNA and outcomes in metastatic breast cancer: a secondary analysis of the BOLERO-2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2, 1310–1315 (2016).

Fribbens, C. et al. Plasma ESR1 mutations and the treatment of estrogen receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 2961–2968 (2016).

Gu, G. et al. Hormonal modulation of ESR1 mutant metastasis. Oncogene 40, 997–1011 (2021).

Frogne, T. et al. Activation of ErbB3, EGFR and Erk is essential for growth of human breast cancer cell lines with acquired resistance to fulvestrant. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 114, 263–275 (2009).

Chen, Y. et al. Effect of AKT1 (p. E17K) hotspot mutation on malignant tumorigenesis and prognosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 573599 (2020).

Pereira, B. et al. The somatic mutation profiles of 2,433 breast cancers refine their genomic and transcriptomic landscapes. Nat. Commun. 7, 11479 (2016).

Martínez-Jiménez, F. et al. A compendium of mutational cancer driver genes. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 555–572 (2020).

Rasti, A. R. et al. PIK3CA mutations drive therapeutic resistance in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive breast cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol. 6, e2100370 (2022).

Baugh, E. H., Ke, H., Levine, A. J., Bonneau, R. A. & Chan, C. S. Why are there hotspot mutations in the TP53 gene in human cancers? Cell Death Differ. 25, 154–160 (2018).

Harrod, A. et al. Genomic modelling of the ESR1 Y537S mutation for evaluating function and new therapeutic approaches for metastatic breast cancer. Oncogene 36, 2286–2296 (2017).

Shrestha Bhattarai, T. et al. AKT mutant allele-specific activation dictates pharmacologic sensitivities. Nat. Commun. 13, 2111 (2022).

Campbell, P. J. et al. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature 578, 82–93 (2020).

Alexandrov, L. B. et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature 578, 94–101 (2020).

Steele, C. D. et al. Signatures of copy number alterations in human cancer. Nature 606, 984–991 (2022).

Lebok, P. et al. 8p deletion is strongly linked to poor prognosis in breast cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 16, 1080–1087 (2015).

Climent, J. et al. Deletion of chromosome 11q predicts response to anthracycline-based chemotherapy in early breast cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 818–826 (2007).

Dellas, A., Torhorst, J., Schultheiss, E., Mihatsch, M. J. & Moch, H. DNA sequence losses on chromosomes 11p and 18q are associated with clinical outcome in lymph node-negative ductal breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 1210–1216 (2002).

Ong, J. Z. L. et al. Requirement for TP73 and genetic alterations originating from its intragenic super-enhancer in adult T-cell leukemia. Leukemia 36, 2293–2305 (2022).

Mo, J., Moye, S. L., McKay, R. M. & Le, L. Q. Neurofibromin and suppression of tumorigenesis: beyond the GAP. Oncogene 41, 1235–1251 (2022).

Olsson, M. & Zhivotovsky, B. Caspases and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 18, 1441–1449 (2011).

Gong, H. et al. p73 coordinates with Δ133p53 to promote DNA double-strand break repair. Cell Death Differ. 25, 1063–1079 (2018).

Miller, K. M. et al. Human HDAC1 and HDAC2 function in the DNA-damage response to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1144–1151 (2010).

Iso, T., Kedes, L. & Hamamori, Y. HES and HERP families: multiple effectors of the notch signaling pathway. J. Cell Physiol. 194, 237–255 (2003).

Panwar, V. et al. Multifaceted role of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway in human health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 375 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Aberrant Cyclin D1 splicing in cancer: from molecular mechanism to therapeutic modulation. Cell Death Dis. 14, 244 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. An autoregulatory feedback loop of miR-21/VMP1 is responsible for the abnormal expression of miR-21 in colorectal cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 11, 1067 (2020).

Corpuz, A. D., Ramos, J. W. & Matter, M. L. PTRH2: an adhesion regulated molecular switch at the nexus of life, death, and differentiation. Cell Death Discov. 6, 124 (2020).

Cortés-Ciriano, I. et al. Comprehensive analysis of chromothripsis in 2,658 human cancers using whole-genome sequencing. Nat. Genet. 52, 331–341 (2020).

Wang, Y. A. et al. Germline breast cancer susceptibility gene mutations and breast cancer outcomes. BMC Cancer 18, 315 (2018).

Anurag, M. et al. Comprehensive profiling of DNA repair defects in breast cancer identifies a novel class of endocrine therapy resistance drivers. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 4887–4899 (2018).

Dustin, D., Gu, G. & Fuqua, S. A. W. ESR1 mutations in breast cancer. Cancer 125, 3714–3728 (2019).

Jeselsohn, R., Buchwalter, G., De Angelis, C., Brown, M. & Schiff, R. ESR1 mutations—a mechanism for acquired endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 12, 573–583 (2015).

Bense, R. D. et al. Relevance of tumor-infiltrating immune cell composition and functionality for disease outcome in breast cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 109, djw192 (2017).

Tutt, A. N. J. et al. Adjuvant olaparib for patients with BRCA1- or BRCA2-mutated breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 2394–2405 (2021).

Isabelle, R.-C. et al. Olaparib plus bevacizumab as first-line maintenance in ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 2416–2428 (2019).

Stone, L. PARP inhibitor response in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 20, 130 (2023).

Tung, N. & Garber, J. E. PARP inhibition in breast cancer: progress made and future hopes. NPJ Breast Cancer 8, 47 (2022).

Butti, R. et al. Development and characterization of a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft of therapy-resistant breast cancer. Oncol. Rep. 49, 1–10 (2023).

Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (2010).

Ewels, P., Magnusson, M., Lundin, S. & Käller, M. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 32, 3047–3048 (2016).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Vasimuddin, Md. et al. Efficient architecture-aware acceleration of BWA-MEM for multicore systems. In IEEE Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium https://doi.org/10.1109/IPDPS.2019.00041 (2019).

Broad Institute. Picard Tools. GitHub repository version 2.18.2. http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ (2018).

McKenna, A. et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

García-Alcalde, F. et al. Qualimap: evaluating next-generation sequencing alignment data. Bioinformatics 28, 2678–2679 (2012).

Ramos, A. H. et al. Oncotator: cancer variant annotation tool. Hum. Mutat. 36, E2423–E2429 (2015).

Auton, A. et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74 (2015).

Wall, J. D. et al. The GenomeAsia 100K Project enables genetic discoveries across Asia. Nature 576, 106–111 (2019).

Lawrence, M. S. et al. Discovery and saturation analysis of cancer genes across 21 tumour types. Nature 505, 495–501 (2014).

Nersisyan, L. & Arakelyan, A. Computel: computation of mean telomere length from whole-genome next-generation sequencing data. PLoS ONE 10, e0125201 (2015).

Barthel, F. P. et al. Systematic analysis of telomere length and somatic alterations in 31 cancer types. Nat. Genet. 49, 349–357 (2017).

Raine, K. M. et al. ascatNgs: identifying somatically acquired copy-number alterations from whole-genome sequencing data. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 56, 15.9.1–15.9.17 (2016).

Mermel, C. H. et al. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 12, R41 (2011).

Van Loo, P. et al. Allele-specific copy number analysis of tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 16910–16915 (2010).

Rausch, T. et al. DELLY: structural variant discovery by integrated paired-end and split-read analysis. Bioinformatics 28, i333–i339 (2012).

Degasperi, A. et al. A practical framework and online tool for mutational signature analyses show intertissue variation and driver dependencies. Nat. Cancer 1, 249–263 (2020).

Islam, S. M. A. et al. Uncovering novel mutational signatures by de novo extraction with SigProfilerExtractor. Cell Genomics 2, 100179 (2022).

Newman, A. M. et al. Determining cell type abundance and expression from bulk tissues with digital cytometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 773–782 (2019).

Yoshihara, K. et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 4, 2612 (2013).

Acknowledgements

N.K.B. acknowledges funding from the ICMR grant (No-2021-14057) and NSM grant (NPGDD), Meity. S.G., P.P.M. and A.M. acknowledge the Department of Biotechnology, Govt. of India, for funding via its BT/MED/30/VNCI-Hr-BRCA/2015 VNCI Multiomics of Endocrine Hormone Therapy Resistance in Breast Cancer Grant. T.M.H. acknowledges that biospecimens disbursed by the National Tumour Tissue Repository (NTTR), TMH, Mumbai, India, were utilised to conduct this translational research. P.P.M. acknowledges the National Science Chair Grant. A.G. acknowledges the ICMR-SRF fellowship (GENOMICS-BMS/2021-10619) and RCB (RCB/NIBMG-PhD/2022-23/A/394/1002). The NGS data was generated through the NIBMG-National Genomics Core platform. Some of the illustrations were created in https://BioRender.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G. and P.P.M. conceptualised the study. S.G., R.C., and P.P. carried out patient recruitment bio-banking collection, patient follow-up, and patient clinical data curation and annotation. A.M. coordinated the sequence data generation using genomics core. N.K.B. conceptualised the strategies of WGS and TCGA data analysis. A.G., C.D., S.D. and N.K.B. carried out whole genome sequence data analysis and analysis of publicly available datasets. A.G., R.C., C.D., P.P.M., S.G. and N.K.B. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Alexey Larionov and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Marina Holz and Mengtan Xing. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghosh, A., Chaubal, R., Das, C. et al. Genomic hallmarks of endocrine therapy resistance in ER/PR+HER2- breast tumours. Commun Biol 8, 207 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07606-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07606-x

This article is cited by

-

Concurrent genomic assessment of circulating tumour cells and ctDNA to guide therapy in metastatic breast cancer

BMC Cancer (2025)

-

Patient derived xenograft models of hormone receptor positive and HER2 negative breast cancer from Indian patients

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Combination chemotherapy and hormone therapy in patients with hormone receptor positive and HER2 negative metastatic breast cancer

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Genomic landscape of hormone therapy-resistant HR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2025)

-

The hormonal nexus in PIK3CA-mutated meningiomas: implications for targeted therapy and clinical trial design

Journal of Neuro-Oncology (2025)