Abstract

Female crickets reared in traffic noise have been reported to be faster or slower to locate male song than those reared in silence across species. We reared female Teleogryllus oceanicus in traffic noise and silence, and had adult females locate male song broadcast amidst traffic noise or silence. We recorded activity of two auditory interneurons in a subset of individuals under identical acoustic conditions. Regardless of rearing treatment, crickets were slower to leave their shelter when presented with male song in silence than in traffic noise, while crickets reared in traffic noise were also slower to leave overall. Crickets reared in traffic noise also had higher baseline AN2 activity, but rearing condition did not affect hearing thresholds or auditory response to male song. Our results demonstrate behavioural and auditory effects of long-term exposure to anthropogenic noise. Further, they support the idea that silence itself is a potentially aversive acoustic condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anthropogenic noise is now prevalent and persistent in many ecosystems, its rise coinciding with an increasingly large and noisy human population1,2,3. Evidence mounts that anthropogenic noise has detrimental effects on animals4 and the potential for anthropogenic noise to interfere with the detection of important environmental cues and communication signals was long suspected5,6,7,8. Anthropogenic noise has now been shown to hinder finding mates9,10,11, avoiding predators12,13,14 and locating prey15,16,17,18,19. Such impediments to detecting, identifying, or locating sounds of interest in noisy environments could be due to interference with sensory encoding of information, cognitive processing of information (e.g., distraction), or both20,21,22. Few, if any, studies, have teased apart how the sensory, cognitive (i.e., neuronal) and behavioural processes are influenced by both lifetime exposure to noise and real-time overlap of human-noise and signals of interest.

Moreover, most research on the effects of anthropogenic noise on animals has focused on terrestrial and aquatic vertebrates4,23,24. However there has recently been more interest in how it might affect insects25,26. Many orthopterans (e.g., crickets and katydids) use sound for finding mates27. The extent to which anthropogenic noise affects mate finding in orthopterans is ambiguous. Different gryllid cricket species have responded differently to anthropogenic noise when locating mates, showing increased difficulty in locating mates in some cases11,28 and not in others29,30. For field crickets we expect road noise in particular to be the most prevelant source of anthropogenic noise (see also ref. 31) and there is some evidence of flexibility in behavioural responses to road noise in orthopterans32,33 and also of genetic adaptation34,35. Similarly, whether lifespan and fecundity are affected by traffic noise is unclear36,37,38.

Consequently, while anthropogenic noise changes behaviour in some eared animals (for review see ref. 24), it is difficult to determine whether this is due to changes at the sensory information processing level of the nervous system. To the best of our knowledge, no published study has considered how the auditory systems of eared insects process anthropogenic sound or how this correlates with their behavior. Crickets are an ideal system in which to examine these relationships as these singing insects have a well-studied auditory system involved in detecting conspecific calling song and predator sounds39,40,41,42,43. Neural recordings have shown masking by—and filtering of—interference sounds in several eared insects44,45,46,47. Gomes and colleagues48 suggest that many of these filtering mechanisms are for naturally occurring noise. In general, orthopterans have developed multiple behavioural and physiological responses to noise, resulting in a resilience to it49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56. Perhaps as a result, some orthopterans are more often found near anthropogenic noise than not33,57,58.

In our study, we aimed to determine (i) if exposure to traffic noise over development impacts a cricket’s ability to perceive or locate the source of male song, and (ii) if simultaneous exposure to traffic noise and male song interferes with a cricket’s ability to perceive or locate the source of male song. If traffic noise interferes with the natural development of cricket hearing, we predicted that crickets reared in such noise would be slower to locate a speaker playing male song and their auditory interneurons would be less responsive to the song compared to crickets reared in silence. Alternatively, if crickets are resilient to nymphal exposure to road noise, we predicted that there would be no difference in their speed in reaching a ‘male’ or in the responsiveness of their auditory interneurons to male song. Similarly, if road noise interferes with the ability of crickets to detect or locate the source of male song, we predicted that in the presence of such noise, crickets would take longer to reach the ‘male’, and auditory interneurons would encode male song less reliably, than when noise is not present.

To test these hypotheses, we used the oceanic field cricket Teleogryllus oceanicus (Orthoptera: Gryllidae). T. oceanicus have sensory structures in their forelegs containing 60–70 receptor cells. Individual receptor cells vary in the frequency to which they are most sensitive (1 kHz to 50 kHz) and their axons project through the leg nerve to the central nervous system, where they synapse with several interneurons59. Two of these interneurons relay information to the brain: ascending neuron 1 (AN1) is narrowly tuned to the dominant frequency of the male call, and ascending neuron 2 (AN2) is broadly tuned to higher frequencies59. The ability to identify AN1 and AN2 action potentials in extracellular recordings from this species has been well-described over decades of research42,43,60,61 allowing us to measure interneuron activity in extracellular recordings. This species is also commonly found near roadsides in its native habitat and has been used in previous behavioral work on the impact of traffic noise30,56. In the study we report here, we used a complete 2 × 2 factorial design to test the developmental and immediate effects of road noise on auditory sensitivity and mate-finding ability, and their potential interaction. Our study considers for the first time the impact of traffic noise on adult female crickets at the neural and behavioural levels, in real time and over development, providing the first integrated study on this timely topic.

Results

Behaviour

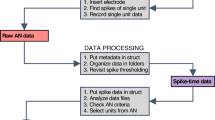

We video recorded adult female crickets in the presence of a speaker playing male song either with no background noise (silence) or with road noise (see Methods, Fig. 1B for experimental set-up; Fig. 2F and Supplementary Fig. 1 for power spectra). Within each group, approximately half the crickets were reared in silence and half were reared in road noise (see Methods, Fig. 1A for rearing conditions). Of the 143 adult female crickets tested across all treatments, 115 reached the focal speaker playing male song. We found no significant effect of rearing condition (χ = 1.03, P = 0.311, n = 143 crickets) or playback condition (χ = 1.39, P = 0.239, n = 143 crickets) on which crickets reached this speaker. While we found no significant interaction effect between rearing and playback condition on the time it took to leave the shelter (β = 0.068, P = 0.746, d.f. = 108, n = 114 crickets; Fig. 2A), we found significant main effects of rearing condition and playback condition. Specifically, female crickets reared in traffic noise took longer to leave the shelter than those reared in silence (β = 0.403, P < 0.001, d.f. = 109, n = 114 crickets), and crickets from both developmental groups took longer to leave the shelter during the silent than the traffic noise treatment (β = −0.282, P = 0.008, d.f. = 109, n = 114 crickets; Fig. 2A).

A Diagram of the rearing chamber set-up, showing the central omnidirectional speaker surrounded by wire mesh containers holding individual female crickets. B Diagram of the experimental arena for testing phonotaxis, showing the 8 sections, central shelter, main speakers playing male song (yellow top) and flanking speakers playing either a silent track or traffic noise (black top).

A Time from the start of the experiment to when the female left the central shelter (n = 114), B Time from when cricket left the shelter until she reached the speaker (n = 114), C Total distance travelled by cricket, as measured by the path length (n = 110), D Total number of times that the female paused walking for more than 0.5 s (n = 109), E Average speed of walking, measured as the total path length divided by the time spent walking (n = 110). Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Values are means, error bars are SE. F Power spectrum (red) of traffic noise overlayed the predominant frequencies of T. oceanicus song (dark grey). We high pass filtered the road noise and cricket song at 200 Hz to exclude <200 Hz internal noise we isolated to the GRAS 4-channel power amplifier and/or Avisoft 8-channel UltraSoundGate (data available at Dryad Deposition).

With respect to the time adult females spent searching for the speaker playing male song after leaving the shelter, we found no significant interaction effect between rearing and playback condition (β = 0.041, P = 0.670, d.f. = 108, n = 114 crickets) and no significant main effect of rearing condition (β = 0.016, P = 0.739, d.f. = 109, n = 114 crickets). There was, however, a significant main effect of playback condition, with crickets spending more time searching during the silent than the traffic noise treatment (β = −0.104, P = 0.032, d.f. = 109, n = 114 crickets; Fig. 2B). There was no significant interaction (β = 0.0005, P = 0.993, d.f. = 104, n = 110 crickets) or main effect (rearing condition: β = 0.023, P = 0.404, d.f. = 105, n = 110 crickets; playback condition: β = 0.010, P = 0.722, d.f. = 105, n = 110 crickets) in the path length the crickets travelled (Fig. 2C). We found, however, a significant interaction effect in the number of pauses females made while walking to the focal speaker (β = 1.159, P < 0.001, d.f. = 103, n = 109 crickets; Fig. 2D): crickets reared in silence and tested in traffic noise paused the least, compared to those crickets reared in silence and tested in silence (β = −1.339, P < 0.001, n = 109 crickets; Fig. 2D), those reared in traffic noise and tested in traffic noise (β = −1.165, P < 0.001, n = 109 crickets; Fig. 2D), and those reared in traffic noise and tested in silence (β = −1.346, P < 0.001, n = 109 crickets; Fig. 2D). There was no significant interaction (β = −4.728, P = 0.639, d.f. = 104, n = 110 crickets) or main effect (rearing condition: β = 8.028, P = 0.111, d.f. = 105, n = 110 crickets; playback condition β = 7.568, P = 0.131, d.f. = 105, n = 110 crickets) in average walking speed (Fig. 2E).

AN1 activity

Individual AN1 spikes were difficult to identify in many of our recordings due to their small size relative to background noise. Therefore, we removed the AN2 spikes from the recordings and measured the difference in amplitude of neural activity before and after sound pulses of increasing amplitudes (see Methods, Fig. 3 for details). Prior to Bonferroni correction, we found apparent significant differences at several points: 4 kHz at 48 dB SPL (t = 2.315, d.f. = 8.927, P = 0.046, n = 14 crickets) and 64 dB SPL (t = 2.504, d.f. = 11.290, P = 0.029, n = 14 crickets), and 6 kHZ at 48 dB SPL (t = −2.707, d.f. = 6.525, P = 0.032, n = 12 crickets) and 54 dB SPL (t = −2.665, d.f. = 7.997, P = 0.029, n = 13 crickets; Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 1). After Bonferroni correction (63 tests, alpha = 0.0008) these significant differences between rearing conditions in RMS dB values did not remain (Supplementary Table 1). When we compared RMS dB values before and after male song in the silent background condition, we found no significant difference in RMS dB values (t = −0.226, d.f. = 8.724, P = 0.827, n = 12 crickets), with and without Bonferroni correction (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 1). Thus, between adult females raised in silence versus those raised in constant road noise, after Bonferroni correction, we found no statistical difference in our indirect measures of AN1 activity across frequencies from 2 kHz to 30 kHz at 2 kHz increments and therefore no evidence of developmental impact of road noise on AN1.

AN2 action potentials (marked with stars) were large enough to be identified individually. AN1 action potentials were often obscured by other neural activity. Minimum AN1 latency was assumed to be 10 ms, and AN1 activity was measured by comparing the root mean square (RMS) amplitude from for 50 ms post-latency with the RMS amplitude for 50 ms pre-latency (data available at Dryad Deposition).

Difference in RMS amplitude of neural activity before and after sound pulses of different frequencies (4 kHz: top panel; 6 kHz: middle panel; 30 kHz: bottom panel). AN2 action potentials were removed prior to RMS measurements. Values are means, error bars are SE (n = 12 to 14 crickets) (data available at Dryad Deposition).

AN2 activity

For AN2 thresholds we excluded the 2 kHz recordings due to lack of response from the majority of crickets. There was no interaction effect between the rearing and playback condition for any sound frequency. There was an apparent effect of rearing treatment on the response threshold at 6 kHz (P = 0.039, n = 18 crickets) and 20 kHz (P = 0.045, n = 18 crickets) before Bonferroni correction but this did not remain after correction (28 tests, alpha = 0.0018) and we noted no significant differences with or without correction at any other frequencies (n = 12 crickets, Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 2). With or without Bonferroni correction, there was no significant effect of playback treatment on AN2 threshold (n = 12 crickets, Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 2). Thus, between adult females raised in silence versus those raised in constant road noise, after Bonferroni correction, we found no statistical difference in our direct measues of AN2 activity across frequencies from 2 kHz to 30 kHz at 2 kHz increments and therefore no evidence of developmental impact of road noise on AN2.

Sound pulses at different frequencies were played back in silence (blue circles) or in traffic noise (red circles) using crickets reared in either silence (top graph) or traffic noise (bottom graph). Crickets reared in silence and tested in traffic noise did not show any response at 2 kHz. Values are means, error bars are SE (n = 18 crickets) (data available at Dryad Deposition).

In baseline AN2 activity, we found an interaction between the rearing and playback condition. Crickets reared in traffic noise had higher baseline AN2 activity but only during the silent playback (β = −0.282, P < 0.001, n = 19 crickets; Fig. 6). After the onset of male song, we no longer found an interaction effect but saw a main effect of playback condition (β = −8.483, P = 0.021, n = 19 crickets), where crickets had higher AN2 spike counts when exposed to traffic noise playback (Fig. 6). There was no significant interaction (β = −0.461, P = 0.713, n = 19 crickets) or main effects of rearing (β = −0.406, P = 0.880, n = 19 crickets) or playback condition (β = −1.981, P = 0.102, n = 19 crickets) in AN2 spike counts 30 s after the onset of male song (Fig. 6). We also found no significant interaction effect (β = 15.332, P = 0.506, n = 19 crickets) or main effect of rearing (β = −9.246, P = 0.817, n = 19 crickets) or playback (β = −5.842, P = 0.480, n = 19 crickets) on instantaneous spike rate immediately after song onset (Fig. 6).

Baseline activity in silence or traffic noise (top panel), during the first 1.3 s of male song (middle panel), and after continuing to hear male song for 30 s. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Values are means, error bars are SE (n = 16 to 19 crickets) (data available at Dryad Deposition).

Discussion

We found that adult female T. oceanicus exposed to traffic noise over juvenile development took longer to leave their shelter and begin searching than those females raised in silence. However, such long-term noise exposure did not influence the time the adult female crickets spent searching after leaving the shelter, nor the total path length they traveled. These results are consistent with previous work on this species30 indicating that long term-exposure to anthropogenic noise can increase, and thus negatively impact, the time females take to locate a potential mate. We also found a striking short-term effect of silence on phonotaxis. In real-time, adult female crickets exposed to male song in an otherwise silent background (as opposed to male song in background traffic noise) take longer to reach the speaker, take longer to leave the shelter, spend more time searching in the arena, and pause more frequently. These results are the opposite of what we might expect if traffic noise directly impedes an adult female cricket’s ability to detect and locate a singing male conspecific.

The AN1 interneuron is the primary interneuron responsible for detecting male song in female crickets. It is tuned to the carrier frequency of the song (4 kHz to 6 kHz in most cricket species), reliably reproduces the syllable pattern of the song, and provides input to brain regions that recognize species-specific song patterns42,62. While we were unable to count individual AN1 spikes, we found that the amplitude of neural activity (with AN2 spikes removed) increased after sound pulses at frequencies corresponding to male song (4 kHz and 6 kHz) but not after sound pulses at 30 kHz, demonstrating that this method quantified AN1 activity levels. We found no significant difference in AN1 activity between crickets reared in traffic noise or silence in response to sound pulses or male song, suggesting that long-term exposure to traffic noise does not affect AN1 responsiveness to sound. These results match those of our phonotaxis experiments, which show that neither traffic noise during development nor simultaneous exposure to traffic noise during phonotaxis had a negative impact on the time a female took to reach the focal speaker once she left her shelter. Taken together, these results show that traffic noise does not impede responses to conspecific song.

The AN2 interneuron in T. oceanicus is broadly tuned from 10 kHz to 50 kHz with a secondary notch of sensitivity around 5 kHz40,63. AN2 responds not only to high frequency predator indicators, but to male song in a way that positively correlates with phonotaxis62,64,65,66,67. Audiograms made with and without background traffic noise revealed no significant differences in hearing thresholds in the crickets, nor between females from different rearing treatments. Therefore, like the AN1 interneuron, AN2 activity is not impaired by traffic noise in real-time. We also found no effect of rearing treatment on the responses of AN2 to male song. After the onset of male song, only crickets in the presence of traffic noise had higher AN2 spike counts, but this effect was no longer present 30 s later. We found that crickets reared in traffic noise, however, had significantly higher baseline AN2 activity than those reared in silence, meaning spontaneous AN2 activity in the absence of acoustic stimulation is apparently higher for crickets reared in traffic noise. Crickets reared in traffic noise also took longer to leave their shelter than those raised in silence. Previous studies with crickets have shown that the time taken to leave a shelter in a novel environment is related to predation pressure68,69. Given that the AN2 interneuron plays a prominent role in predator detection39,40, we suggest higher baseline activity levels could be related to the observed extra caution in novel environments. Overall, these results indicate that long-term traffic noise exposure changes AN2 activity, but not in a way that should impair females’ detection of singing males.

It is often difficult to disentangle the mechanisms by which anthropogenic noise affects animals48. Here, using a design to control for equivalent sound pressure level exposure and to minimize vibration across subjects, we confirm that long-term exposure to road noise causes changes at both the behavioural and auditory system levels. While long term exposure to traffic noise over development appears to delay adult female mate-searching behaviour, we found it has no discernable effect on whether, nor how much, the AN1 or AN2 interneuron responds to male song. The difference in behaviour seen in earlier studies is thus likely a result of cognitive differences (i.e., interneuronal activity differences, here upstream of AN1 and AN2, sensu70,71), rather than a reduced (or improved) ability to hear conspecific male song.

That anthropogenic noise does not stop female crickets from detecting male song is not entirely surprising. For many orthopterans the ability to isolate conspecific song is necessary because in many habitats there are heterospecific species competing for acoustic space. Choruses of singing insects can reach ambient noise levels of >60 dB SPL in neo-tropical forests with a mean of around 55 dB SPL72. This is not as high as the background noise levels often found in urban cores73,74 but higher than that typical of rural communities73. Crickets that call in these highly noisy choruses possess a variety of adaptations to compensate for interference noise at the neural26,47,75, morphological54,76 and behavioural levels26,50,77. There is no obvious reason to assume that these adaptations would not also function in urban environments nor that they could not evolve to do so78. Long-term evolutionary changes to adapt to louder soundscapes are clearly possible as crickets from tropical forests are better able to filter out background noise levels than European field crickets from less acoustically competitive environments47.

These differences in noise tolerance between species are important when considering the effect of anthropogenic noise on orthopterans in general and between species. Much of the conflicting information about the effect of anthropogenic noise in these insects may be, at least partially, the result of little overlap in the species used in published work11,29,30,37,49,52. Species-specific evolutionary and life histories could result in different responses to anthropogenic noise, making broad inferences about this insect order difficult. In the study we report here we used T. oceanicus, a species which had been used before by Gurule-Small and Tinghitella30 and we found similar behavioural results to theirs, with phonotaxis taking longer when the crickets were reared in traffic noise. T. oceanicus has evolved in the presence of another cricket with a similar frequency song, T. commodus, and due to interbreeding avoidance, both species have evolved different auditory filtering mechanisms79. That T. oceanicus has neuronal filters that distinguish between conspecific and heterospecific songs of similar frequency might explain why anthropogenic noise playback had little effect on searching behaviour or auditory activity, as a sensitivity filter able to separate two songs of similar frequency should also be able to filter out the more divergent frequency content of traffic noise.

Intriguingly, the slower phonotaxis behaviour we saw in response to the silent background condition may result from crickets interpreting their environment as riskier than in the presence of background noise. Silence is not a natural state for many habitats, and background noises can themselves indicate safety (e.g., their cessation indicating predator presence)80. Many animals use silence as an indication of threat or higher risk level and, indeed, are more likely to forage12, move81 and produce mating displays82,83 when in the presence of sounds from either conspecifics or innocuous heterospecifics than when in silence. We thus suggest that the increase in time to leave the shelter, longer search times, and greater number of pauses without increase in path length could reflect a fear response to silent environments. That is, adult female crickets were not covering greater total distances in silence but simply pausing more frequently, an established indicator of fear in many prey species84. Interestingly, males of some Hawaiian T. oceanicus populations experience a conspecific chorus silence: males have lost the ability to sing due to the high risk of attracting a phonotactic parasitoid fly species85. Females in these populations may experience more difficulty in finding a mate not only because conspecific males are mainly those of the silent morph, but also, given our results of the effects of silence on female behaviour, individual females seeking out males may be more vigilant. However, the difficulties females have in finding males may be offset because both sexes in the Hawaiian populations move more than individuals in populations where males sing86.

Overall, our results indicate that although long-term road noise can cause behavioural and auditory system level changes in developing crickets, adult females’ ability to perceive and locate males is resilient to these pressures. That is, it does not appear that road noise prevents crickets from finding mates, but that such noise does cause changes in decision making and some auditory activity. Future work should determine why anthropogenic noise and silence influence the observed levels of caution in crickets, whether these time delays are long enough to have fitness consequences, and why this apparently differs between orthopteran species.

Methods

Sound recordings

We recorded traffic noise from the highway on-ramp at the Hurontario Street and Queen Elizabeth Way 400-series highway intersection (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Specifically, 12 meters away from the intersection on a grassy knoll, we mounted a recorder (Song Meter Mini Bat, Wildlife Acoustics, Maynard) and recorded a full uninterrupted week (168 h) of traffic noise (sampled at 24 kHz from July 25-Aug 2, 2021; for power spectra see Fig. 2F and Supplementary Fig. 1). We downloaded the calling song of T. oceanicus from the Orthoptera Species File Website87 recorded in 1993 using a Sony WM-D3 at 96 kHz and modified it according to protocols described in ref. 30,88 to create one full repeat of the song that is expected to be attractive to females (for power spectra see Fig. 2F).

Animals, rearing conditions, and acoustic environments

We used T. oceanicus crickets from a colony maintained at the University of Toronto Mississauga. The colony was started in 2005 from two populations of eggs collected from wild-caught females from Mo’orea, French Polynesia and Darwin, Australia, which were then combined in 2011. The crickets to be used in our experiments were hatched and reared in plastic boxes (Width: 0.35 m, Length: 0.5 m, Height 0.40 m; partially filled with cardboard egg cartons) and provided food (1:1 ratio of cat food and fish food) and water ad libitum. They were kept at 23 °C on a 14/10 h light/dark cycle and checked daily to identify females. Crickets were sexed at their penultimate instar and we removed identified females from their box and placed them in individual containers. These containers consisted of a closed top aluminum mesh cylinder (Height: 10 cm, Diameter: 9.5 cm) placed over an upside-down clear plastic container covered in cotton batting. Inside the container, we provided each cricket with water, the same food blend, and an overturned egg carton cup as a shelter. We then transferred these females and their individual containers to a custom acoustic chamber (Width: 1.73 m, Length: 2.03 m, Height: 2.03 m) that was lined with acoustic foam (ceiling, walls) and had a floor of corkboard and carpet (Fig. 1A). Eighty six female crickets were successfully reared in 2021 and 77 in 2022 for a total of 163 female crickets.

We split the penultimate instar female crickets into two even groups and each group was placed into one of the two identical acoustic chambers described above. In each chamber, we placed an omnidirectional loudspeaker (Free Space 51, Bose) in the center of the room on a circular disk cork (Diameter: 0.45 m, 6.25 mm thick). We placed the cricket containers equidistantly around the speaker, on top of a separate ring of cork flooring (outside Diameter: 1.52 m; hole Diameter: 0.61 m), with each container 60 cm away from the speaker and with the aluminum mesh cylinder in line with the mid-line of the speaker membrane (Fig. 1A). Each chamber contained one lamp (OttLite T81G5T-SHPR 18-watt, Tampa) on a 14 h/10 h light/dark cycle with temperature ranging from 23 to 25 °C. To control for potential room effects, crickets were switched between rooms every week, and each time their order was randomized around the speaker.

The two groups of developing crickets experienced different acoustic treatments. We exposed one group to a looping track of the full week of traffic noise described above, played from the central speaker in the room (the “traffic noise” group). We chose an average of ~70 dBA SPL for the road noise at each cricket’s container to roughly match that reported by Gurule-Small and Tinghitella30. To this end, for the traffic noise group the sound level at each cricket container averaged ~70 dBA SPL and ranged from 59 to 97 dB SPLA (range corresponding to minimums during lulls in traffic and maximums when emergency vehicles with sirens on passed nearby). At the on-ramp recording site, this range of amplitudes matched those measured in dBA SPL at ~7 metres from the nearest curb of the same on-ramp using the same weigthing as the same sound level meter (R8060, REED Instruments). For both of the above measures we set the REED sound level meter to both 125 ms and 1 s for time weightings and neither the averages nor the ranges differed between these time weightings. We also tested this REED sound level meter, which has a ½” microphone, using a B&K Type 4231calibrator (1 kHz tone, 94 dB SPL relative to 20 μPa) with its ½” microphone adapter in place, and determined the REED sound level meter was measuring dBA SPL accurately at 1 kHz for 125 ms and 1 s time weightings (i.e., as 94 dB).

The second group of developing crickets had the speaker on, but it did not play a sound file (the “silence” group). For this group, we measured the ambient noise in the room to be below 30 dBC SPL (1 s time weighting) using the same REED sound level meter, the digital display output of which we video recorded with a smartphone camera, which allowed us to leave the room. We determined that the ambient noise level in the room was less than 30 dBC SPL for the silence group, since this was the lowest reading that the sound level meter registered and it did not register sound when the recordings were not being played. As we did for the dBA settings above, we determined that the REED was measuring a 94 dB, 1 kHz tone accurately at the dBC 125 ms and 1 s time weighting settings as well.

Of the one hundred and forty three crickets that reached maturity under the two acoustic conditions described above there was no significant difference in the time to reach maturity between the two groups (mixed linear model: β = −1.4036, P = 0.0878, d.f. = 150). For each of the two years, the number of crickets raised under each acoustic condition was roughly equal. In 2021, we raised 37 adult females in traffic noise and 34 in silence, while in 2022, we raised 35 in traffic noise and 37 in silence.

Experimental trials: behaviour

To compare the effect of the two rearing treatments on adult female phonotaxis, we randomly assigned crickets at fourteen days after final moult to a background acoustic condition of traffic noise or silence (speaker on but no sound) during male song playback. In the center of the experimental trial room (Height: 2.3 m, Width: 2.6 m, Length: 4.6 m), we placed a circular arena made of cork (Diameter: 1.22 m, 6.25 mm thick) on the floor, the arena was marked with a circle of 1.2 m diameter. The circle was divided into 8 segments of equal arc (45°; Fig. 1B). We randomly assigned two focal speakers (Ultrasonic Dynamic Speakers, Vifa, Avisoft, Berlin) to opposite sides of the arena for each trial, positioned on the dividing line between two segments. Each of these focal speakers was flanked by two paired speakers (Companion 20, Bose, Framingham) 25 cm to either side of it along the circumference of the arena. All 6 speakers faced the arena center. We calibrated our Bose Companion 20 speakers using a Shure 57 instrument microphone (Shure, Eppingen) (flat from <150 Hz to >15 kHz) and found them relatively flat (± 4 dB) from 150 Hz to 15 kHz. Focal speakers only ever played cricket song, while flanking speakers only played road noise or silence.

For each trial, we placed an adult female cricket under an egg carton cup in the center of the arena and then covered the cup with a darkened plastic container to constrain the cricket. The four flanking Bose speakers played either a 3-min repeating segment of traffic noise, selected for its low variability in amplitude (~ 70 dBA SPL average, 68–78 dBA SPL range), or a silent sound file. For both of the preceding acoustic treatments, we randomly selected one of the focal speakers to play the modified calling song of T. oceanicus (~70 dBA SPL average, 68–72 dBA SPL range). These dBA measures were taken from the REED sound level meter at a 125 time weighting, which had been calibrated and determined accurate as described above. These dBA values of road noise and cricket song were selected to match those used by Gurule-Small and Tinghitella30 in their similar phonotaxis experiment and are similar to previously reported road noise power spectra89.

The amplitudes of the road noise and the cricket song were also calibrated using a ¼” free-field microphone (type 46BE, GRAS, Holt, Denmark) and calibrator (type 4231; Brüel and Kjær) and recorded by GRAS microphone connected via a GRAS 12AX 4-channel power module and UltraSoundGate 816H data acquisition board to a laptop computer running Avisoft Recorder software. For this calibration routine, we separately recorded (i) this same 3-min segment of the road noise and also (ii) 5 repetitions of the full cricket song. The road noise from the Bose speakers, the cricket song from the Avisoft speakers. The GRAS microphone was placed at the same location as starting position of the crickets and was pointed directly at the speakers (Avisoft, Bose) which, as for behavioural and neural trials (see below) were 60 cm away. Using the same equipment and settings, we also recorded a calibration tone (1 kHz, 94 dB SPL) and used this as a reference in using the Avisoft SASLab Pro software. Road noise measurements were taken from 36 sequential samples of 5 s duration. T. oceanicus song measurements were taken from 5 repetitions of the song. For each sample, we measured the root mean square (rms) amplitude of the sound and the power spectrum as dB values per frequency relative to a maximum of zero. The rms amplitude of the calibration tone was used as a reference to determine the sound amplitude of each sample and the peak of each power spectrum was set to this amplitude with the amplitudes of the other frequencies being measured relative to peak (i.e., 94 dB SPL + 20*log10(rms of sample/rms of calibration tone) + amplitude of frequency relative to peak). We determined that both road noise and cricket song were on average 70 dB SPL rms at 60 cm from the speakers for road noise (peak: 1 kHz) and cricket song (peak: 5.3 kHz; see Fig. 2F for further details).

After the acoustic playbacks commenced, the crickets were given 60 s to acclimatise to their physical and acoustic environment before the plastic container covering the egg cup was removed, which marked the beginning of the trial. The observer (E.A.E.) was in adjacent room separated by a door. We videorecorded all trials at 15 frames per second using an HD 1080 P CCTV dome camera (Avalonix, New York) mounted 2.45 m overhead. Each trial lasted five minutes and was considered complete if the cricket reached the edge of the circle or failed to reach it by the five-minutes mark. We first scored crickets based on whether they successfully reached the focal speaker playing the male song (i.e., exiting from one of the two segments on either side of the focal speaker). For crickets that exited the arena, we determined how long they took to (a) emerge from the egg carton shelter (start latency). We then calculated (b) search time, that is the time from emergence to the completion of the trial. We weighed each cricket after the trial to later control for potential size-based variation in our statistical analyses. All trials were conducted at ~21 °C.

Video footage of the trials was further analyzed using video tracking software (Ctrax ver 0.5.18). We took a series of coordinates indicating the position of the cricket for each frame of the video from Ctrax and, using the R package “trajr”, used these coordinates to calculate the total distance travelled for each cricket, henceforth referred to as (c) path length. Following Schmitz and colleagues90, we also counted how often crickets paused during the search period, treating any period in which the cricket did not move for >7 video frames (i.e., over 0.53 s) as a single pause. The total of these pauses is henceforth referred to as the (d) pause number. Finally, we divided the (d) path length by the amount of time spent moving during search time (b) to get the (e) average speed of each cricket, where time spent moving was set as equal to (b) search time subtract time spent paused.

Experimental trials: auditory activity

We recorded neural responses to conspecific song under the same acoustic conditions used in the phonotaxis experiments to assess the possible impact of traffic noise on auditory development. To do so, we first randomly selected 20 crickets used in the phonotaxis experiment, 10 of which had been reared under traffic noise and 10 reared in silence. To prepare crickets for the neurophysiological recordings, we pinned them ventral side up to a block of modelling clay and removed the cuticle on the ventral surface between the head and thorax. This exposed the cervical connectives that contain the axons of the AN1 and AN2 auditory interneurons. We then draped one of the cervical connectives over a hook-shaped tungsten recording electrode and placed a reference electrode in the abdomen. Electrodes were connected to a differential amplifier (DP-301, Warner Instruments, Hamden) and the output was passed to a data acquisition board (Avisoft UltrasoundGate 816H) for digital recording on a computer.

The neurophysiological recordings were made in one of the two acoustic chambers. We used the same arenas and speakers used in and as described for the behavioral/phonotaxis trials, the only exceptions being a lack of shelter in the center where the cricket neural preparation was placed and that only one pair of Bose speakers (which, as for the behavioral trials, were used only for road noise) flanked a single Avisoft focal speaker (which, as for behavioral trials, was used only for cricket song and, additionally, for these neural recordings the 20 ms pure tones used to generate the audiograms). We also placed a microphone (Avisoft CM16) one meter from the center of the arena opposite the speakers. The microphone was connected to a different channel of the same data acquisition board as the differential amplifier. We placed the cricket neural preparation in the center of this arena, with the ear ipsilateral to the recorded connective facing towards, and 60 cm away from, the focal speaker.

To measure AN2 thresholds and AN1 activity across frequencies (i.e., to produce audiograms), we played increasingly loud sound pulses from 2 kHZ to 30 kHz at 2 kHz intervals from the focal speaker. Frequencies were presented in random order. For each frequency, sound pulses increased in amplitude from 30 dB SPL to 80 dB SPL in 2 dB steps. Sound pulses were 20 ms in duration (including 1 ms rise/fall times) and broadcast at 500 ms intervals to avoid neural adaptation. The total time taken for each audiogram was 3 min and 8 s. Not all crickets were able to complete all conditions before expiring. The amplitudes of the audiogram sound pulses were calibrated using a ¼” free-field microphone (type 4939, Brüel and Kjær) and calibrator (type 4231, Brüel and Kjær). For this calibration routine, the sound pulses were played from the focal Avisoft speaker and recorded by the Brüel and Kjær microphone, which was placed at the same location as the neural preparation and was pointed directly at the speaker with all other equipment in place. The microphone was connected via an Avisoft power module 40017 and an UltraSounGateSG 116Hme data acquisition board to a laptop computer running Avisoft Recorder software. Using the same equipment and settings, we also recorded a calibration tone (1 kHz, 94 dB SPL) and used this as a reference to adjust the sound pulses to the correct amplitudes using Avisoft SASLab Pro software. Sound pulses were recorded again after calibration to ensure they were the correct amplitude in the setup. To compare the insects’ hearing sensitivity between silent and road noise background acoustic conditions, audiograms were run twice, in silence and with traffic noise from the flanking speakers calibrated to be ~70 dBA (range: 68–78 dBA SPL) at the cricket.

Last, to measure interneuron activity in response to cricket song under the conditions crickets experienced during the phonotaxis experiment, we played T. oceanicus song from the focal speaker to the neural preparations under two noise conditions: silence or traffic noise from the flanking speakers calibrated to be ~70 dBA (range: 68–78 dB SPL) at the cricket. We first recorded neural activity in the background noise condition (silence or traffic noise) for one minute to establish a baseline response to the background condition. After a minute, we began playback of the T. oceanicus song from the focal speaker alongside the background acoustic condition for another minute, totaling 2 min for the entire sequence. Between individuals, crickets were exposed to the two acoustic conditions in a random order. Not all crickets were able to complete all conditions before expiring.

As for the road noise and cricket song playbacks used in our phonotaxis/behavioral experiments, we also calculated the the average dB SPL rms amplitude of the 3-min segment of road noise and 5 cricket song sequences at the neural preparation and, as for the behavioral trials, determined them to be ~70 dB at ~1 kHz and 5.3 kHz, respectively. We did so using the routine described for the behvioural trials (i.e., GRAS not Brüel and Kjær microphone).

Statistics and Reproducibility

Data analysis: behaviour

We used a Chi-squared test (n = 143 crickets) to determine if the number of crickets successfully reaching the focal speaker differed based on the rearing and/or playback treatment. Including only the crickets that successfully reached the correct speaker, we then used linear models to examine the effects of rearing and playback treatments on the measured behavioural variables. Models included rearing treatment, playback treatment and the interaction between them as effects, and insect weight and room temperature as controls. Models had one of (a) start latency (n = 114 crickets) or (b) search time (n = 114 crickets) or (c) path length (n = 110 crickets) or (d) number of pauses (n = 109 crickets) or (e) average speed (n = 110 crickets) (calculated as the distance travelled divided by the difference between the time to search and time spent paused) as the response variable. Search time and start latency were log normal transformed to correct for skew in the data and the model for number of pauses used a Poisson family link function. Pairwise comparisons for the number of pauses model were done using Tukey HSD test on the effective marginal means.

Data analysis: auditory activity for AN1

We used sound analysis software (SASLab Pro, Avisoft Bioacoustics) to visually inspect the neural recordings. We found that individual AN1 action potentials (spikes) could not be reliably identified in many of the recordings to count spikes. Therefore, we looked for evidence of AN1 activity in response to sound pulses by comparing the amplitude of the neural activity before and after each pulse of sound. For the audiograms recorded in silence (no background noise), the start time of each pulse in the recording was measured in SASLabPro acoustic analysis software (Avisoft Bioacoustics) for the 4 kHz, 6 kHz, and 30 kHz sequences. The first two frequencies are closest to the typical male calling song’s dominant frequency of ~5 kHz and are those most likely to elicit AN1 spikes. The 30 kHz stimulus is in the range of bat echolocation calls and will not elicit AN1 spikes, but is effective at eliciting AN2 spikes.

Neural recordings were bandpass filtered between 300 Hz and 10 kHz in Avisoft SASLab Pro (zero phase, Hamming Window, 1024 taps). Because the AN2 neuron also responds to 4 kHz and 6 kHz sound pulses, we used the Pulse Train Analysis feature to label AN2 spikes in each recording for removal. To remove these AN2 spikes, we then used the Change Volume feature to render their amplitude zero. A minimum latency of 10 ms was assumed for the AN1 cell to respond to a sound pulse. We used a custom R script to measure the root mean square (RMS) amplitude of the neural recordings from 40 ms before to 10 ms after the start of each sound pulse (50 ms pre-latency) and from 10 ms to 60 ms after the start of each sound pulse (50 ms post-latency) (Fig. 3). Sections with significant neural noise were excluded from analysis. To compare neural activity pre- and post-latency, we calculated the amplitude difference in dB (20*log(post-latency RMS/pre-latency RMS)). We used t-tests (n = 12 to 14 crickets) to compare RMS amplitude between crickets reared in silence or traffic noise for the audiograms and responses to song.

Data analysis: auditory activity for AN2

AN2 spikes were identified based on their large size relative to other neural activity on the recordings and their lower thresholds for high frequency sounds. To create neural audiograms, we measured AN2 threshold (dB SPL) for each frequency as the lowest amplitude sound pulse to elicit a burst of AN2 spikes. We classified it as a burst/response to the sound pulse if (i) the latency of the first spike was less than 50 ms after the start of the sound pulse, and (ii) more than one spike was present with intervals <20 ms between them. This was done for recordings made in both silence and with background traffic noise. The gain settings for recording neural activity were adjusted to maximize the amplitude of the AN2 spike in recordings, and thus the absolute background noise level varied across recordings. For each frequency in the audiogram, we then ran within subject mixed ANOVA’s with the amplitude at threshold as the response variable, and rearing treatment, playback treatment, and their interaction as main effects (n = 18 crickets). Pairwise t-tests were conducted for each frequency when no interaction effect was found. Due to the number of tests (28), we applied a Bonferroni correction to the results.

To assess neural responses to T. oceanicus song, we counted the number of AN2 spikes at three points in time over the course of the song recordings: 30 s after the background noise condition had begun (silence or traffic noise), at the start time of the T. oceanicus song, and 30 s after the T. oceanicus song had started. In all three cases, we counted the number of spikes in 1.3 s, which is the duration of the repeated pulse sequence of the T. oceanicus song. For each time point, we ran linear mixed models with the number of AN2 spikes as the response variable, and rearing treatment, playback treatment, and their interaction as main effects, and individual crickets as random effects (n = 16 to 19 crickets). We used a Poisson family distribution for the background noise condition due to significant rightward skew of the data. Type III Wald Chi-square tests were used to estimate P-values. We also measured the minimum instantaneous spike rate for AN2 (inverse of time between two spikes) at each time point and ran linear mixed models with minimum instantaneous spike rate as the response variable, and rearing treatment, playback treatment, and their interaction as main effects, with individual cricket as a random effect. Type III Wald Chi-square tests were used to estimate P-values.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data, including the source data for the graphs in Figs. 2–6, have been deposited at Dryad at the following url: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.tb2rbp09r91.

Code availability

Scripts have been deposited at Dryad at the following url: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1275199392.

References

Barber, J. R., Crooks, K. R. & Fristrup, K. M. The costs of chronic noise exposure for terrestrial organisms. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 180–189 (2010).

Slabbekoorn, H. et al. A noisy spring: the impact of globally rising underwater sound levels on fish. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 419–427 (2010).

Buxton, R. T. et al. Noise pollution is pervasive in U. S. protected areas. Science 356, 531–533 (2017).

Shannon, G. et al. A synthesis of two decades of research documenting the effects of noise on wildlife. Biol. Rev. 91, 982–1005 (2016).

Brumm, H. & Slabbekoorn, H. Acoustic communication in noise. Adv. Stud. Behav. 35, 151–209 (2005).

Francis, C. D., Ortega, C. P. & Cruz, A. Noise pollution changes avian communities and species interactions. Curr. Biol. 19, 1415–1419 (2009).

Slabbekoorn, H. & Ripmeester, E. A. P. Birdsong and anthropogenic noise: implications and applications for conservation. Mol. Ecol. 17, 72–83 (2008).

Tyack, P. L. Implications for marine mammals of large-scale changes in the marine acoustic environment. J. Mammal. 89, 549–558 (2008).

Habib, L., Bayne, E. M. & Boutin, S. Chronic industrial noise affects pairing success and age structure of ovenbirds Seiurus aurocapilla. J. Appl. Ecol. 44, 176–184 (2007).

Gordon, S. D. & Uetz, G. W. Environmental interference: impact of acoustic noise on seismic communication and mating success. Behav. Ecol. 23, 707–714 (2012).

Schmidt, R., Morrison, A. & Kunc, H. P. Sexy voices - no choices: male song in noise fails to attract females. Anim. Behav. 94, 55–59 (2014).

Hughes, R. A., Mann, D. A. & Kimbro, D. L. Predatory fish sounds can alter crab foraging behaviour and influence bivalve abundance. Proc. B 281, 20140715 (2014).

Simpson, S. D. et al. Anthropogenic noise increases fish mortality by predation. Nat. Comm. 7, 10544 (2016).

Wale, M. A., Simpson, S. D. & Radford, A. N. Noise negatively affects foraging and antipredator behaviour in shore crabs. Anim. Behav. 86, 111–118 (2013).

Allen, L. C., Hristov, N. I., Rubin, J. J., Lightsey, J. T. & Barber, J. R. Noise distracts foraging bats. Proc. B 288, 1–7 (2021).

Bunkley, J. P. & Barber, J. R. Noise reduces foraging efficiency in pallid bats (Antrozous pallidus). Ethology 121, 1116–1121 (2015).

Luo, J., Siemers, B. M. & Koselj, K. How anthropogenic noise affects foraging. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 3278–3289 (2015).

Mason, J. T., McClure, C. J. W. & Barber, J. R. Anthropogenic noise impairs owl hunting behavior. Biol. Conserv. 199, 29–32 (2016).

Siemers, B. M. & Schaub, A. Hunting at the highway: traffic noise reduces foraging efficiency in acoustic predators. Proc. B 278, 1646–1652 (2011).

Chan, A. A. Y. H. & Blumstein, D. T. Attention, noise, and implications for wildlife conservation and management. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 131, 1–7 (2011).

Naguib, M. Living in a noisy world: indirect effects of noise on animal communication. Behaviour 150, 1069–1084 (2013).

Wiley, R. H. Signal detection, noise, and the evolution of communication. In Animal Communication and Noise (ed. Brumm, H.) 7–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41494-7 (Springer, 2013).

Duquette, C. A., Loss, S. R. & Hovick, T. J. A meta-analysis of the influence of anthropogenic noise on terrestrial wildlife communication strategies. J. Appl. Ecol. 58, 1112–1121 (2021).

Slabbekoorn, H., Dooling, R. J., Popper, A. N. & Fay, R. R. Effects of anthropogenic noise on animals. In Handbook on Auditory Research, Vol. 66. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-8574-6 (Springer, 2018).

Morley, E. L., Jones, G. & Radford, A. N. The importance of invertebrates when considering the impacts of anthropogenic noise. Proc. B 281, 20132683 (2013).

Schmidt, A. K. D. & Balakrishnan, R. Ecology of acoustic signalling and the problem of masking interference in insects. J. Comp. Physiol. A 201, 133–142 (2015).

Alexander, R. D. Acoustical communication in arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 12, 495–526 (1967).

Bent, A. M., Ings, T. C. & Mowles, S. L. Anthropogenic noise disrupts mate choice behaviors in female Gryllus bimaculatus. Behav. Ecol. 32, 201–210 (2021).

Costello, R. A. & Symes, L. B. Effects of anthropogenic noise on male signalling behaviour and female phonotaxis in Oecanthus tree crickets. Anim. Behav. 95, 15–22 (2014).

Gurule-Small, G. A. & Tinghitella, R. M. Developmental experience with anthropogenic noise hinders adult mate location in an acoustically signalling invertebrate. Biol. Lett. 14, 20170714 (2018).

Welsh, G. T. et al. Consistent traffic noise impacts few fitness-related traits in a field cricket. BMC Ecol. Evol. 23, 78 (2023).

Gallego-Abenza, M., Mathevon, N. & Wheatcroft, D. Experience modulates an insect’s response to anthropogenic noise. Behav. Ecol. 31, 90–96 (2020).

Rebrina, F., Reinhold, K., Tvrtković, N. & Brigić, A. Motorway proximity affects spatial dynamics of orthopteran assemblages in a grassland ecosystem. Insect Conserv. Diver. 15, 213–225 (2022).

Kuriwada, T. Differences in male calling song and female mate location behaviour between urban and rural crickets. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 139, 275–285 (2023).

Lampe, U., Reinhold, K. & Schmoll, T. How grasshoppers respond to road noise: developmental plasticity and population differentiation in acoustic signalling. Funct. Ecol. 28, 660–668 (2014).

Ichikawa, I. & Kuriwada, T. The combined effects of artificial light at night and anthropogenic noise on life history traits in ground crickets. Ecol. Res. 38, 446–454 (2023).

Rebar, D., Bishop, C. & Hallett, A. C. Anthropogenic light and noise affect the life histories of female Gryllus veletis field crickets. Behav. Ecol. 33, 731–739 (2022).

Gurule-Small, G. A. & Tinghitella, R. M. Life history consequences of developing in anthropogenic noise. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 1957–1966 (2019).

Fullard, J. H., Ratcliffe, J. M. & Guignion, C. Sensory ecology of predator-prey interactions: responses of the AN2 interneuron in the field cricket, Teleogryllus oceanicus to the echolocation calls of sympatric bats. J. Comp. Physiol. A 191, 605–618 (2005).

Fullard, J. H. et al. Release from bats: genetic distance and sensoribehavioural regression in the Pacific field cricket, Teleogryllus oceanicus. Naturwissenschaften 97, 53–61 (2010).

Nolen, T. G. & Hoy, R. R. Initiation of behavior by single neurons: the role of behavioral context. Science 226, 992–994 (1984).

Schöneich, S., Kostarakos, K. & Hedwig, B. An auditory feature detection circuit for sound pattern recognition. Sci. Adv. 1, 1–7 (2015).

ter Hofstede, H. M., Killow, J. & Fullard, J. H. Gleaning bat echolocation calls do not elicit antipredator behaviour in the Pacific field cricket, Teleogryllus oceanicus (Orthoptera: Gryllidae). J. Comp. Physiol. A 195, 769–776 (2009).

Fullard, J. H., Ratcliffe, J. M. & Jacobs, D. S. Ignoring the irrelevant: auditory tolerance of audible but innocuous sounds in the bat-detecting ears of moths. Naturwissenschaften 95, 241–245 (2008).

Hartbauer, M., Radspieler, G. & Römer, H. Reliable detection of predator cues in afferent spike trains of a katydid under high background noise levels. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 3036–3046 (2010).

Römer, H. Matched filters in insect audition: tuning curves and beyond. In The Ecology of Animal Senses: Matched Filters for Economical Sensing (eds. von der Emde, G. & Warrant, E.) 83–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25492-0 (Springer, 2016).

Schmidt, A. K. D., Riede, K. & Römer, H. High background noise shapes selective auditory filters in a tropical cricket. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 1754–1762 (2011).

Gomes, D. G. E., Francis, C. D. & Barber, J. R. Using the past to understand the present: coping with natural and anthropogenic noise. BioScience 71, 223–234 (2021).

Einhäupl, A., Stange, N., Hennig, R. M. & Ronacher, B. Attractiveness of grasshopper songs correlates with their robustness against noise. Behav. Ecol. 22, 791–799 (2011).

Greenfield, M. D. Interspecific acoustic interactions among katydids Neoconocephalus: inhibition-induced shifts in diel periodicity. Anim. Behav. 36, 684–695 (1988).

Faulkes, Z. & Pollack, G. S. Effects of inhibitory timing on contrast enhancement in auditory circuits in crickets (Teleogryllus oceanicus). J. Neurophysiol. 84, 1247–1255 (2000).

Reichert, M. S. Effects of noise on sound localization in male grasshoppers, Chorthippus biguttulus. Anim. Behav. 103, 125–135 (2015).

Römer, H. Neurophysiology goes wild: from exploring sensory coding in sound proof rooms to natural environments. J. Comp. Physiol. A 207, 303–319 (2021).

Römer, H. & Bailey, W. Strategies for hearing in noise: peripheral control over auditory sensitivity in the bushcricket Sciarasaga quadrata (Austrosaginae: Tettigoniidae). J. Exp. Biol. 201, 1023–1033 (1998).

Schul, J. Neuronal basis of phonotactic behaviour in Tettigonia viridissima: processing of behaviourally relevant signals by auditory afferents and thoracic interneurons. J. Comp. Physiol. A 180, 573–583 (1997).

Zuk, M., Tanner, J. C., Schmidtman, E., Bee, M. A. & Balenger, S. Calls of recently introduced coquí frogs do not interfere with cricket phonotaxis in Hawaii. J. Insect Behav. 30, 60–69 (2017).

Bunkley, J. P., McClure, C. J. W., Kawahara, A. Y., Francis, C. D. & Barber, J. R. Anthropogenic noise changes arthropod abundances. Ecol. Evol. 7, 2977–2985 (2017).

Rebrina, F., Reinhold, K., Tvrtković, N., Gulin, V. & Brigić, A. Vegetation height as the primary driver of functional changes in orthopteran assemblages in a roadside habitat. Insects 13, 1–18 (2022).

Huber, F., Moore, T. E. & Loher, W. Cricket Behavior and Neurobiology https://doi.org/10.7591/9781501745904 (Cornell University Press, 1989).

Moiseff, A., Pollack, G. S. & Hoy, R. R. Steering responses of flying crickets to sound and ultrasound. Mate attraction and predator avoidance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75, 4052–4056 (1978).

Pollack, G. S. et al. Representation of behaviorally relevant sound frequencies by auditory receptors in the cricket, Teleogryllus oceanicus. J. Exp. Biol. 201, 155–163 (1998).

Schildberger, K. & Hörner, M. The function of auditory neurons in cricket phonotaxis. II. Modulation of auditory responses during locomotion. J. Comp. Physiol. A 163, 633–640 (1988).

Nolen, T. G. & Hoy, R. R. Phonotaxis in flying crickets: II. Physiological mechanisms of two-tone suppression of the high frequency avoidance steering behavior by the calling song. J. Comp. Physiol. A 159, 441–456 (1986).

Jeffery, J., Navia, B., Atkins, G. & Stout, J. Selective processing of calling songs by auditory interneurons in the female cricket, Gryllus pennsylvanicus: possible roles in behavior. J. Exp. Zool. Part A 303, 377–392 (2005).

Samuel, L., Stumpner, A., Atkins, G. & Stout, J. Processing of model calling songs by the prothoracic AN2 neurone and phonotaxis are significantly correlated in individual female Gryllus bimaculatus. Physiol. Entomol. 38, 344–354 (2013).

Schöneich, S. Neuroethology of acoustic communication in crickets - from signal generation to song recognition in an insect brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 194, 101882 (2020).

Stout, J., Stumpner, A., Jeffery, J., Samuel, L. & Atkins, G. Response properties of the prothoracic AN2 auditory interneurone to model calling songs in the cricket Gryllus bimaculatus. Physiol. Entomol. 36, 343–359 (2011).

Hedrick, A. V. Crickets with extravagant mating songs compensate for predation risk with extra caution. Proc. B 267, 671–675 (2000).

Hedrick, A. V. & Kortet, R. Hiding behaviour in two cricket populations that differ in predation pressure. Anim. Behav. 72, 1111–1118 (2006).

Dukas, R. & Ratcliffe, J. M. Introduction. In Cognitive Ecology II (eds. Dukas, R. & Ratcliffe, J. M.) 1–4. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226169378.001.0001 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

Ratcliffe, J. M., Fullard, J. H., Arthur, B. J. & Hoy, R. R. Adaptive auditory risk assessment in the dogbane tiger moth when pursued by bats. Proc. B 278, 364–370 (2011).

Ellinger, N., Hodl, W. & Ellinger, N. Habitat acoustics of a neotropical lowland rainforest. Bioacoustics 13, 297–321 (2003).

Albert, D. G. & Decato, S. N. Acoustic and seismic ambient noise measurements in urban and rural areas. Appl. Acoust. 119, 135–143 (2017).

Lee, E. Y., Jerrett, M., Ross, Z., Coogan, P. F. & Seto, E. Y. W. Assessment of traffic-related noise in three cities in the United States. Environ. Res. 132, 182–189 (2014).

Schmidt, A. K. D. & Römer, H. Solutions to the cocktail party problem in insects: Selective filters, spatial release from masking and gain control in tropical crickets. PLoS One 6, 28593 (2011).

Morley, E. L. & Mason, A. C. Active auditory mechanics in female black-horned tree crickets (Oecanthus nigricornis). J. Comp. Physiol. A 201, 1147–1155 (2015).

Greenfield, M. D. Inhibition of male calling by heterospecific signals artifact of chorusing or abstinence during suppression of female phonotaxis? Naturwissenschaften 80, 570–573 (1993).

Raboin, M. & Elias, D. O. Anthropogenic noise and the bioacoustics of terrestrial invertebrates. J. Exp. Biol. 222, jeb178749 (2019).

Bailey, N. W., Moran, P. A. & Hennig, R. M. Divergent mechanisms of acoustic mate recognition between closely related field cricket species (Teleogryllus spp.). Anim. Behav. 130, 17–25 (2017).

Luttbeg, B., Ferrari, M. C. O., Blumstein, D. T. & Chivers, D. P. Safety cues can give prey more valuable information than danger cues. Am. Nat. 195, 636–648 (2020).

Pereira, A. G., Cruz, A., Lima, S. Q. & Moita, M. A. Silence resulting from the cessation of movement signals danger. Curr. Biol. 22, 627–628 (2012).

Huang, B., Lubarsky, K., Teng, T. & Blumstein, D. T. Take only pictures, leave only fear? The effects of photography on the West Indian anole Anolis cristatellus. Curr. Zool. 57, 77–82 (2011).

Symes, L. B., Page, R. A. & ter Hofstede, H. M. Effects of acoustic environment on male calling activity and timing in Neotropical forest katydids. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 70, 1485–1495 (2016).

Eilam, D. Die hard: A blend of freezing and fleeing as a dynamic defense - implications for the control of defensive behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 29, 1181–1191 (2005).

Zuk, M., Rotenberry, J. T. & Tinghitella, R. M. Silent night: adaptive disappearance of a sexual signal in a parasitized population of field crickets. Biol. Lett. 2, 521–524 (2006).

Schneider, W. T., Rutz, C. & Bailey, N. W. Behavioural plasticity compensates for adaptive loss of cricket song. Ecol. Lett. 27, e14404 (2024).

Cigliano, M. M., Braun, H., Eades, D. C. & Otte, D. Teleogryllus Oceanicus Song. Orthoptera Species File. https://Orthoptera.SpeciesFile.org (2021).

Bailey, N. W. Love will tear you apart: different components of female choice exert contrasting selection pressures on male field crickets. Behav. Ecol. 19, 960–966 (2008).

Okada, Y., Sakamoto, S. & Fukushima, A. Field measurements of sound power spectrum for predicting road traffic noise. Acoust. Sci. Technol. 41, 622–625 (2020).

Schmitz, B., Scharstein, H. & Wendler, G. Phonotaxis in Gryllus campestris L. (Orthoptera, Gryllidae) I. Mechanism of acoustic orientation in intact female crickets. J. Comp. Physiol. A 148, 431–444 (1982).

Etzler, E. A. Data from: anthropogenic noise exposure over development increases baseline auditory activity and decision-making time in adult crickets [Dataset]. Dryad. https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.tb2rbp09r (2024).

Etzler, E. A. Data from: anthropogenic noise exposure over development increases baseline auditory activity and decision-making time in adult crickets. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12751993 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank R. N. Sarkar for maintaining the cricket colony, G. K. Morris for use of his space and contributions to design, A. R. Hasan and A. Chowdhury for advice on coding and statistics, P. M. Kotanen and B. C. McMeans for discussion, and R. Holland and two anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript. Funded by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada grants to J.M.R. and H.M.tH and NSERC and Ontario Graduate Scholarships to E.A.E.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M.R. oversaw the project. E.A.E. conducted the behavioural work. H.M.H. and E.A.E. performed the neural recordings. Analyses and interpretations were made by E.A.E., J.M.R., H.M.H., and D.T.G. E.A.E. wrote the paper with input given and editing done by J.M.R., H.M.H., and D.T.G.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Richard Holland and Manuel Breuer.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Etzler, E.A., ter Hofstede, H.M., Gwynne, D.T. et al. Road noise exposure over development increases baseline auditory activity and decision-making time in adult crickets. Commun Biol 8, 280 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07643-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07643-6

This article is cited by

-

Many ways for sensory systems to stumble and fail in the Anthropocene

Journal of Biosciences (2025)