Abstract

HIV infection remains incurable as the virus persists within a latent reservoir of CD4+T cells. Novel approaches to enhance immune responses against HIV are essential for effective control and potential cure of the infection. In this study, we designed a novel tetravalent bispecific antibody (Bi-Ab32/16) to simultaneously target the gp120 viral protein on infected cells, and the CD16a receptor on NK cells. In vitro, Bi-Ab32/16 triggered a potent, specific, and polyfunctional NK-dependent response against HIV-infected cells. Moreover, addition of the Bi-Ab32/16 significantly reduced the latent HIV reservoir after viral reactivation and mediated the clearance of cells harboring intact proviruses in samples from people with HIV (PWH). However, the in vivo preclinical evaluation of Bi-Ab32/16 in humanized mice expressing IL-15 (NSG-Hu-IL-15) revealed a significant decline of NK cells associated with poor virological control after ART interruption. Our study underscores the need to carefully evaluating strategies for sustained NK cell stimulation during ART withdrawal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While antiretroviral therapy (ART) effectively suppresses HIV viremia, it is unable to completely eliminate the virus that persists in anatomical and cellular reservoirs1,2. The latent HIV reservoir represents the main barrier to reach a cure, and is mostly constituted by resting memory CD4+ T cells that do not produce viral particles, thus being invisible to the action of ART and the immune system3,4. Recent efforts to eliminate the latent reservoir have focused on the “shock and kill” strategy, which involves the reactivation of HIV gene expression with latency reversal agents (LRAs) followed by immune-mediated clearance of infected cells5. Despite progress, most LRAs are ineffective at reversing latency ex vivo, and have failed to reduce the size of the latent reservoir in vivo6,7, especially in anatomical reservoirs where the bioavailability of the drugs is distinct from plasma8. Moreover, both HIV infection and treatment with specific LRAs are known to compromise the function of key immune components involved in the clearance of HIV infected cells, including CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells9,10. Consequently, there is an urgent need for the development of novel therapeutic strategies to target persistent HIV in ART-treated individuals.

NK cells, as cytotoxic innate lymphoid cells, exhibit potent responses against infected and malignant cells11. Similar to CD8+ T cells, NK cells experience swift and dynamic alterations during early HIV infection, exerting direct cytotoxic responses independent of HLA class I restriction12. NK cell activation and effector functions hinge on interactions involving germline-encoded activating or inhibitory receptors and their corresponding ligands on target cells13,14. Notably, the activating receptor CD16, has been described as the sole receptor capable of activating cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion independent of additional signals15. During HIV infection, NK cells exhibit the capacity to suppress viral replication and regulate cells harboring HIV-DNA16. Furthermore, recent research reveals antigen-specific memory development in human NK cells exposed to HIV, primarily dependent on the NKG2C/HLA-E axis17. Additionally, NK cells can kill HIV-infected cells by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), where the CD16 receptor on NK cells interacts with the Fc portion of antibodies that are bound to HIV-infected cells, leading to their activation and cytotoxic response18,19. These diversified functions position NK cells as attractive players for immunotherapeutic interventions aimed to target the HIV reservoir. Thus, recruiting and activation of NK cells by targeting CD16a in close proximity to infected cells could be an effective strategy against HIV-infection.

Several studies provide compelling evidence that ADCC-mediating antibodies play an important role in the context of HIV and SIV infection20,21,22. These studies establish a correlation between ADCC responses and lower viral loads23, protection from infection24,25, and improved clinical outcome in linked transmission26. Several non-neutralizing antibodies have been described to promote ADCC during HIV infection27,28. Among them, A32 is a non-neutralizing antibody isolated from an individual with HIV that has been reported to recognize a conformational epitope involving the C1 and C4 regions of HIV-gp120 present in the membrane of HIV-infected cells, following Env binding to CD429. Importantly, the A32 antibody stands as a promising candidate for targeting HIV-infected cells as it presents important features, including broad reactivity against envelopes from all HIV-1 clades30, highly conserved epitope residues30, and no evidence of epitope escape mutations31. Importantly, the A32 antibody targets the earliest expressed epitope during the course of infection and at the time of virus budding32,33, a feature that may hold significance for shock and kill strategies29.

Immune-targeted therapies based on the use of antibodies to promote NK cell mediated immune responses against HIV have been previously explored. However, antibody therapies face some limitations, including the high dosage to induce a clinical response or the need to promote an efficient cell-to-cell contact between target and effector cells. In this regard, bispecific antibodies (BiAbs) can promote the specific recruitment of effector cells by engaging its receptors to a target. BiAbs are engineered immunoglobulins that contain the specificities and properties of two different monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) into a single molecule. Thus, BiAbs can elicit synergistic activities and enhance therapeutic efficacy and/or safety compared to conventional monospecific IgGs therapies34. Recent studies in the field of hematological malignancies have described bispecific formats aimed at redirecting NK-mediated immune responses towards leukemia/lymphoma targets35,36. Of note, this approach has progressed to clinical trials involving individuals with relapsed/refractory CD30+ malignancies (NCT01221571, NCT04101331). In addition, bispecific NK cell engagers (BiKE) have been previously developed to engage NK cells through the CD16a receptor and lyse HIV-infected cells37,38,39. Some strategies include bispecific antibodies directed to CD16a and gp4139 or to the CD4 extracellular domain 137. Further, a recent study has described two bispecific antibodies targeting the HIV envelope protein (Env) and CD16, promoting NK-mediated in vivo reduction of HIV-reservoir cells in a mouse model of HIV infection40. These studies provide evidence supporting the engagement of CD16a as a potent mechanism for favorably tilting the balance towards NK cell activation. Although bispecific formats have been explored, no study up to date has assessed the role of CD16-targeting bispecific antibodies on viral recrudescence after ART interruption.

Here, to enhance the NK cell immune response against HIV-expressing cells, we engineered a tetravalent bispecific antibody (Bi-Ab32/16) targeting the gp120 HIV protein (Ab A32) and the molecule CD16a. Our study provides proof-of-concept that Bi-Ab32/16 is capable of mediating potent elimination of HIV reservoir cells ex vivo, but the in vivo administration to humanized mice infected with HIV translates into a rapid viral rebound associated with the loss of NK cells. Thus, our data contributes important clues for the development of novel immunotherapies targeting NK cells.

Results

Bi-Ab32/16 promotes specific cell-to-cell contact between HIV-expressing CD4+ T and NK cells, and shifts the NK cell phenotype

We incorporated sequences of antibodies against Env and CD16a into Bi-Ab32/16 (Supplementary Table 1). Bi-Ab32/16 consists of a polypeptide chain encoding the full-length non-neutralizing A32 antibody (anti-HIVgp120) combined with a single-chain variable fragment (ScFv) domain from CD16a (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). The A32 antibody exhibits specificity towards the conformational epitopes C1 and C4 on the HIV-1 gp120 Env protein following its interaction with CD4. It has been described to recognize envelopes from all HIV-1 clades and eliminate HIV-1 infected cells through ADCC29,30. In addition, prior studies have indicated that CD16a plays a role in promoting NK cell activation and cytotoxicity18.

A Schematic illustrating the structure of the tetravalent bispecific antibody Bi-Ab32/16, comprising the IgG A32 antibody, targeting the gp120 target protein on HIV-infected CD4 + T cells, and the single-chain variable fragment (ScFv) CD16a directed towards the CD16 receptor expressed on NK cells. Created in BioRender. Genescà, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/m03t574. B Representative flow cytometry plots depicting the binding of anti-HIVgp120 (A32 antibody, 5 µg/ml) and Bi-Ab32/16 (0.2 µg/ml) to CEM NKR CCR5+ cells coated with the HIV-1 Bal gp120 recombinant protein after 20 min incubation. Recognition of the respective antigens by the antibodies was determined using an anti-human secondary antibody targeting the heavy chains on human IgG antibodies, including A32. C Representative flow cytometry plots illustrating the binding of anti-CD16 (3G8 antibody) and Bi-Ab32/16 to primary isolated NK cells. The ability of the antibodies to recognize their cognate antigens was assessed using an anti-mouse secondary antibody recognizing the 3G8 antibody. D Summary graph of n = 7 independent experiments depicting the binding of anti-HIVgp120 and Bi-Ab32/16 to CEM NKR CCR5+ cells coated with the HIV-1 Bal gp120 recombinant protein after 20 min incubation. E Summary graph showing the binding of anti-CD16 (3G8 antibody) and Bi-Ab32/16 to primary isolated NK cells. N = 7 independent experiments are shown. F Representative gating strategy employed to identify cell doublets using FSC-H and FSC-A parameters (left), and subsequent analysis of the frequency of cell doublets expressing CD4 and CD16 (right) upon incubation with Bi-Ab32/16. G Optimized t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (opt-SNE) representations displaying the distribution of NK cell clusters based on the expression of different phenotypic markers in total (CD56 + ) NK cells by condition. Two conditions are depicted: control (R10 medium) and Bi-Ab32/16 following 24 h stimulation. H Heatmap depicting variations in the mean fluorescence expression of distinct NK cell receptors between control (R10 medium) and Bi-Ab32/16 conditions, corresponding to the different cell clusters identified in Fig. 1G and represented in different colors. I Violin plots showing the frequency of the distinct NK cell clusters identified in Fig. 1G among the distinct conditions. Statistical comparisons were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test when required. Median with range (min-max) are shown. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

To evaluate the binding capacity of Bi-Ab32/16 to its corresponding targets (gp120 and CD16a), we stained primary isolated CD4+ T cells coated with gp120, and autologous isolated NK cells with the bispecific antibody. Parental single A32 and anti-CD16a antibodies were used as controls. Antibody binding to cell surface was detected using a secondary antibody directed to the heavy chain of human IgG, including A32 (IgG anti-HIV gp120) (Fig. 1B, C). Bi-Ab32/16 demonstrated percentages of binding to its target molecules similar to those of monospecific antibodies, both on gp120-expressing CD4+ T cells and NK cells (Fig. 1D, E). Once the binding of the Bi-Ab32/16 was confirmed, we investigated the potential of the antibody to target both molecules at the same time, and its capacity to bring closer both gp120-expressing CD4+ T and NK cells. Cell-to-cell contact experiments were performed by culturing both cell types in the presence of the Bi-Ab32/16. The frequency of double positive CD4+CD16+ (cell doublets) was analyzed by flow cytometry. We observed that Bi-Ab32/16 was able to induce the formation of cell-to-cell doublets, and within these doublets, we observed a considerable increase (mean 12-fold) in the frequency of specific CD4-NK doublets (Fig. 1F). Overall, our results show that the Bi-Ab32/16 binds to both targets simultaneously and induces the formation of cell doublets among gp120-expressing CD4+ T and CD16+ NK cells.

Subsequently, we studied if stimulation with the Bi-Ab32/16 for 24 h promoted a shift in the expression pattern of important receptors for NK cell activity. An example of the gating strategy used is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2A. For these analyses, we included NK receptors with activating or inhibitory potential upon interaction with ligands found on HIV-infected cells (CD16, NKG2C, NKG2A, NKG2D, NKp30, and KIR2DL2/L3 (CD158b)), the maturation marker CD57, the negative immune regulator KLRG1, and the chemokine receptor CXCR3. FMOs for markers with continuous expression are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2B. Upon stimulation with Bi-Ab32/16, NK cells exhibited higher levels of CD16, CD57, and CD158b, as well as co-expression of both NKG2C and CD57 markers (Supplementary Fig. 3). Reduction of dimensionality and unsupervised clustering analysis using FlowSOM algorithm allowed us to identify ten different NK cell clusters with a particular expression of the selected phenotypic markers (Fig. 1G). Specifically, clusters #PH2 and #PH4 identified subpopulations expressing the memory-like markers CD57 and NKG2C, while exhibiting low levels of NKG2A (Fig. 1H). Of note, cluster #PH4 presented high NKG2C levels and expressed the chemokine receptor CXCR3, while cluster #PH2 presented dim NKG2C expression and null or low CXCR3 expression (Fig. 1H). These populations were also characterized by an increased expression of CD16, NKG2D and the inhibitory receptor CD158b (Fig. 1H). Interestingly, frequencies of these clusters were higher after Bi-Ab32/16 treatment (Fig. 1I). In addition, upon Bi-Ab32/16 stimulation, higher frequencies of #PH8 were observed, which defined an NK cell NKG2CdimCD57- memory-precursor population with high expression of CD16 and Nkp30, as well as CD158b and KLRG1 (Fig. 1H, I). In contrast, Bi-Ab32/16 treatment resulted in the reduction of cluster #PH9, characterized by elevated NKG2A levels (Fig. 1H, I). Overall, our results show that stimulation with Bi-Ab32/16 may promote the generation of NK cells with fully mature memory-like features (NKG2C+CD57+), high expression of the inhibitory KIR CD158b and the activating receptor NKG2D, and low levels of the inhibitory NKG2A receptor.

Bi-Ab32/16 elicits robust NK cell activation and ADCC responses in the presence of HIV-expressing cells

As a next step, we defined whether the Bi-Ab32/16 promoted the activation and induction of cytotoxic NK cells in response to HIV-expressing cells. CEM NKR CCR5+ cells coated with gp120 recombinant protein were co-cultured with isolated NK cells for 4.5 h in the presence of Bi-Ab32/16 or the parental A32 antibody. PMA/Ionomycin was used as a positive control. Distinct functional markers were measured by flow cytometry, including early (CD69) and late (HLA-DR) activation markers and cytotoxicity markers, such as proinflammatory IFNγ and surrogate marker for degranulation CD107a. In general, we observed that in the presence of the Bi-Ab32/16, primary NK cells (CD3-CD56+) produced higher IFNγ and CD107a levels compared to cells treated with the A32 antibody (Supplementary Fig. 4A, B). In addition, Bi-Ab32/16 treatment induced an increase in polyfunctional IFNγ+CD107a+ NK cells compared to A32 (Supplementary Fig. 4C). Of note, Bi-Ab32/16 treatment did not significantly affect NK cell activation measured by the single expression of CD69 and HLA-DR, although a slight tendency to increased CD69+ NK cell frequencies was observed upon the addition of the Bi-Ab32/16 (Supplementary Fig. 4D, E). Dimensionality reduction analysis identified six clusters in the NK population based on the expression of activation and cytotoxicity markers. Among these activated clusters, #AC1, #AC2 and #AC5 were significantly expanded following Bi-Ab32/16 and PMA/Ionomycin stimulation (Fig. 2A, B). These clusters comprised cells with a strong cytotoxic profile, co-expressing CD107a and IFNγ, while cluster #AC5 included the expression of the activation marker CD69 (Fig. 2C, D). Importantly, these clusters were not present in A32-treated NK cell co-cultures, or in the presence of Bi-Ab32/16 lacking the gp120 target protein (no target condition) (Fig. 2A, E), demonstrating that the response was specific. In summary, our findings indicate that Bi-Ab32/16 is superior to A32 inducing cytotoxic NK cell responses against gp120-coated CD4+ T cells. These results are of significance as they underscore the specificity of the bispecific antibody, which by itself remains insufficient to elicit NK cell cytotoxicity, functioning only in the context of HIV-expressing cells.

A Reduction of dimensionality analysis displaying the distribution of NK cell clusters identified based on the expression of different activation and functional markers in total (CD56+) NK cells by condition (left to right): NK cells co-cultured with CD4+ T cells lacking the expression of the target protein (HIVgp120) with Bi-Ab32/16 (No target), and in the presence of CD4+ T cells expressing the target protein with A32, PMA/Ionomycin, and Bi-Ab32/16. B Volcano plots showing the statistically significant differences in the cluster compositions between Bi-Ab32/16 and control (R10 medium), anti-HIVgp120 (A32) or PMA/Ionomycin conditions. C Expression of CD107a and IFNγ on the different clusters identified in Fig. 2A by condition. D Heatmap depicting variations in the mean fluorescence expression of distinct activation and functional markers between study conditions, corresponding to the different cell clusters identified in (A). E Violin plots showing the frequency of the different cell clusters of NK cells identified in (A) by study condition. Statistical comparisons were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test when required. Median with range (min-max) are shown *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. F Representative flow cytometry plots for calculation of the ADCC activity of NK against HIV-expressing cells. CEM NKR CCR5+ cells were double-stained with PKH67 and eF670, and coated with the HIV-1 Bal gp120 recombinant protein. Cells were co-cultured with primary NK for 4 h at 1:10 target/effector ratio, and in the presence of anti-HIVgp120 (A32 antibody) or Bi-Ab32/16. Conditions without antibodies (R10 medium), without target cells (no target), and in the presence of HIV+ plasma, were included as controls. Loss of the eF670 marker was used to determine the percentage of dead cells in an eF670 versus PKH67 plot. ADCC was calculated by normalizing the proportion of dead cells observed within the PKH67 versus eFluor670 plot in the co-culture conditions with antibodies to that of the co-culture without antibodies (referred to as basal killing). G Dose response fitted nonlinear regression model and EC50 calculated values for Bi-Ab32/16 and anti-HIVgp120 (A32). H Summary graph of the ADCC activity mediated by NK cells from both healthy donors and PWH in the presence of the distinct antibodies. Normalization was performed by subtracting the percentage of killing observed in the basal condition (without ADCC-mediating antibodies) from the percentage of killing obtained in each experimental condition. Statistical comparisons were performed using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. Median with range (min-max) are shown *p < 0.05.

We next evaluated the ADCC activity of NK cells treated with Bi-Ab32/16 in response to HIV-expressing cells. To this end, CEM NKR CCR5+ cells coated with gp120 were co-cultured with primary isolated NK cells in the presence of Bi-Ab32/16 or the parental A32 antibody. Plasma from a viremic HIV+ participant containing a pool of antibodies targeting gp120 was used as a positive control. Cell killing was measured by the loss of the marker eFluor670 by flow cytometry (Fig. 2F and Supplementary Fig. 5A). Several antibody concentrations were employed to determine the EC50 value for both Bi-Ab32/16 and parental A32 antibodies in a dose-response curve. The results showed that the Bi-Ab32/16 induced a powerful ADCC response (EC50 = 0.01 µg/ml), with an EC50 fifty-five times lower than the parent A32 antibody (EC50 = 0.55 µg/ml) (Fig. 2G). Overall, Bi-Ab32/16 induced the killing of a higher percentage of gp120-coated target cells when compared to A32 antibody (Fig. 2H). Since NK from people with HIV (PWH) may be dysfunctional41, we also determined the capability of the Bi-Ab32/16 to promote ADCC by NK cells from PWH. Of note, in the presence of Bi-Ab32/16, NK cells from PWH exhibited similar ADCC responses relative to healthy donors (Fig. 2H). Therefore, our results provide evidence that Bi-Ab32/16 can effectively trigger a robust ADCC response in NK cells obtained from both healthy donors and PWH, which is far more potent than the parental A32 antibody.

Bi-Ab32/16 effectively binds and elicits a robust ADCC response against ex vivo HIV-infected cells

To evaluate Bi-Ab32/16 in a productive ex vivo HIV infection model, we initially assessed its binding capacity to HIV-infected cells. To this end, we performed ex vivo infection of isolated CD4+ T cells with HIVBaL (CCR5-tropic) strain, followed by flow cytometry analysis of p24+ expression after 5 days of culture. Cell surface antibody binding of Bi-Ab32/16 and A32 was detected using a secondary antibody targeting the heavy chain of human IgG. A representative gating strategy is depicted in Fig. 3A, with distinct populations analyzed: infected CD4+p24+cells (depicted in green, Fig. 3B), infected CD4-p24+cells (depicted in yellow, Fig. 3C), and uninfected CD4+p24- cells (depicted in blue, Fig. 3D). Predominantly, p24+ cells were CD4+ (Fig. 3A), and within this subset, Bi-Ab32/16 exhibited binding percentages akin to the A32 antibody alone (mean 78.7% vs 70.6%, respectively), which were significantly elevated compared to the condition without primary antibodies (Fig. 3B, E). Moreover, Bi-Ab32/16 binding to p24+ cells with downregulated CD4 mirrored that of A32 alone (Fig. 3C, E). However, binding frequencies were lower in CD4-p24+ cells compared to CD4+p24+ cells, expected due to antibodies targeting conformational gp120 epitopes exposed upon CD4 binding, which may be less exposed when CD4 is downregulated28. Additionally, minimal binding of Bi-Ab32/16 and A32 antibodies was observed in uninfected CD4+ T cells, suggesting a potential limited bystander killing upon treatment with either antibody (Fig. 3D, E). Overall, Bi-Ab32/16 bound ~52% of the total p24+ population, similar to A32 alone (Median binding = 51%) (Fig. 3F). Hence, Bi-Ab32/16 recognizes and binds to a significant proportion of the HIV-infected T cells.

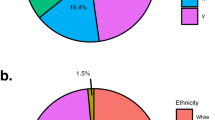

A Representative flow cytometry plots depicting ex vivo HIVBaL infection of CD4+ T cells through the detection of the viral protein p24. Plots demonstrate the expression of p24 and CD4 in uninfected, infected, Bi-Ab32/16-treated, or anti-HIVgp120 (A32)-stimulated cells. Three distinct cell populations are analyzed: CD4+p24- cells (depicted in blue), CD4+p24+ cells (depicted in green), and CD4-p24+ cells (depicted in yellow). B Representative flow cytometry plots illustrating the gating of anti-human IgG-expressing cells within the CD4+p24+ cell population under distinct conditions (from left to right): infected, treated with Bi-Ab32/16, or treated with A32. Similar plots are shown for (C) CD4-p24+ cells and (D) CD4+p24- cells. E Violin plots depicting the frequency of anti-human IgG+ cells quantified across various experimental conditions, including infected, Bi-Ab32/16-treated, or A32-stimulated cells, within the distinct cell populations analyzed (from left to right): CD4+p24+ cells, CD4-p24+ cells, and CD4+p24- cells. Statistical comparisons were performed using ANOVA Friedman test. Median with range (min-max) are shown. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. F Pie charts illustrating the median frequency of total p24+ HIV-infected cells bound to Bi-Ab32/16 (represented by dark blue) or A32 (represented by dark green) antibodies. G Representative flow cytometry plots showing HIV infection, as determined by the detection of the viral protein p24, following a 6-day infection period with HIVBal (upper) and HIVNL4.3 (lower) strains. Plots show the reduction of p24 expression upon co-culture of infected CD4+ T cells with NK cells stimulated with Bi-Ab32/16 or anti-HIVgp120 (A32) antibodies. HIV+ plasma was included as a positive control. H Violin plots depicting the reduction in p24 expression after co-culturing ex vivo HIVBal (left) or HIVNL4.3 (right) infected CD4+ T cells with NK cells previously treated with Bi-Ab32/16 or anti-HIVgp120 (A32) antibodies. Statistical comparisons were performed using 2way ANOVA followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. Median with range (min-max) are shown. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Next, we used the ex vivo HIV infection model to validate the ability of the bispecific antibody to induce ADCC responses in a productive HIV infection system. To this end, we performed ex vivo infection of isolated CD4+ T cells with two distinct viral strains: BaL (CCR5-tropic) and NL4.3 (CXCR4-tropic). After 5 days of culture, ex vivo HIV-infected CD4+ T cells were co-cultured with autologous isolated NK cells in the presence of Bi-Ab32/16 or A32 antibodies. Cell killing was assessed by the reduction of infected (p24+) CD4+ T cells by flow cytometry. Gating strategy is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5B. Representative flow cytometry plots showing CD4+ infection with HIVBaL and HIVNL4.3 strains over the distinct antibody conditions are depicted in Fig. 3G. NK cells treated with Bi-Ab32/16 displayed a robust ADCC response towards CD4+ T cells productively infected with HIVBaL or HIVNL4.3 compared to cells alone or to the A32 antibody condition (Fig. 3H). Specifically, Bi-Ab32/16 was able to reduce HIV infection by 75% for HIVBaL, and 62% for HIVNL4.3. Overall, our findings support the potential of Bi-Ab32/16 in eliciting a robust ADCC-mediated elimination of HIV-infected cells, surpassing the effects achieved by the A32 antibody alone.

Bi-Ab32/16 enhances the NK-mediated killing of latently HIV-infected cells from PWH following viral reactivation

Next, we assessed if treatment with Bi-Ab32/16 induced an NK-mediated cytotoxic response against viral-reactivated cells from the persistent natural HIV reservoir. Isolated CD4+ T cells from PWH with non-detectable viremia (2–6 years ART-treated) were subjected to PMA/Ionomycin reactivation, and subsequently incubated with autologous isolated NK cells. As previously reported, viral reactivation was measured by the intracellular expression of the viral protein p24 by flow cytometry42,43(Supplementary Fig. 6). NK cells stimulated with the Bi-Ab32/16 were able to reduce the pool of reactivated cells by a median of 55%, compared to NK cells alone (Fig. 4A). By contrast, cells treated with A32 presented a reduction of 12%, relative to NK cells alone. Moreover, we quantified the intact proviral DNA in CD4+ T cells following pharmacological reactivation in the presence of Bi-Ab32/16 and autologous NK cells in another set of PWH with non-detectable viremia. Reduction in the intact proviruses was observed in three out of five samples tested (Fig. 4B). Our results are consistent with a recent study describing the impact of two CD16-specific antibodies in promoting the NK-mediated elimination of cells harboring intact proviral DNA, observed in ~70% of the samples tested40. Overall, we show that the Bi-Ab32/16 enhances the killing of productively and reactivated HIV-infected cells via ADCC and, in some individuals, reduces the intact HIV reservoir after viral reactivation. Therefore, these properties of our Bi-Ab32/16 hold potential significance within the context of emerging shock and kill strategies.

A Violin plots showing the reduction in p24 expression in CD4+ T cells from ART-treated PWH upon latency reversal with PMA/Ionomycin and co-culture with NK cells treated with anti-HIVgp120 (A32) or Bi-Ab32/16. Statistical comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. *p < 0.05. B Intact proviral DNA assay (IPDA) in samples from five ART-treated PWH after performing the NK killing assay with primary ex vivo reactivated CD4+ T cells with PMA and ionomycin and autologous isolated NK cells. IgG2 was added as an isotype control.

Evaluation of the Bi-Ab32/16 in a humanized mice model expressing IL-15

We next performed the preclinical evaluation of the Bi-Ab32/16 using the Hu-NSG-Tg (IL-15) mouse model44 (Fig. 5A). A total of n = 33 Hu-NSG-Tg (IL-15) mice were challenged with 104 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infectious dose) of HIVBaL strain. Mice received ART from week 6 to 9 post-infection (WPI). From 8 – 10 WPI, they were randomized in three groups of animals (n = 6/group) that received A32 or Bi-Ab32/16 (500 µg/mouse) twice a week, or PBS as a vehicle control, a protocol selected based on prior evaluation of the plasma pharmacokinetics of Bi-Ab32/16 after a single injection (Supplementary Fig. 7A, B). Immune cell subsets and time to viral rebound were monitored from 11 until 13 WPI (Fig. 5A). Of note, mice did not show any evidence of toxicity, measured by changes in weight, during the course of the study (Supplementary Fig. 7C). As previously described, hCD3+ and hCD56+ cells represented relatively low frequencies among the total hCD45+ cell population at baseline, in contrast to hCD19+ cells, which constituted the predominant proportion44 (Supplementary Fig. 7D). NK cells, identified by CD56 expression, constituted a mean of 6% of the overall hCD45+ cell population, mirroring the ranges in human blood (2–18%) previously described45. Furthermore, NK cells exhibited a standard subset distribution at baseline, where the CD56dimCD16high subset predominated in peripheral blood, consistent with the pattern observed in human blood44 (Supplementary Fig. 7E).

A Schematic representation of the experimental design. 33 Hu-NSG-Tg (IL-15) mice were infected with 10,000 TCID50 of HIVBal, administered ART from weeks 6–9 post infection (WPI), randomized and injected intraperitoneally with 500 µg of Bi-Ab32/16, anti-HIVgp120 (A32) or vehicle from weeks 8 – 10, sampled for peripheral blood weekly, and euthanized in two groups at weeks 11 and 13 for collection of blood and splenic tissue. Created in BioRender. Genescà, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/z93u557. B Evolution of the frequency of CD56+ NK cells from peripheral blood of HIV-infected mice by condition. C Time to viral rebound expressed by HIV-1 RNA copies per ml of plasma from 0 – 4 weeks after ART interruption in Hu-NSG-Tg (IL-15) treated with Bi-Ab32/16, anti-HIVgp120 (A32) or vehicle. Data are shown as individual values (thin lines) and average values (dashed and thicker lines). D Spearman correlation between the frequency of CD56+ NK cells and viral load expressed as HIV-1 RNA copies/ml at 13 WPI. Statistical comparisons were performed using Mann-Whitney test. Median with range (min-max) are shown. *p < 0.05.

Based on previous reports44, we analyzed parameters associated with HIV infection at 3–6 WPI. Although HIV viral loads were detected at 3 WPI, ranging from 103 to 105 copies/ml, in 24 out of 34 animals (Supplementary Fig. 7F), all HIV-challenged Hu-NSG-Tg (IL-15) mice experienced a significant depletion of circulating hCD45+ and hCD4+ cells at 4 WPI, followed by a reduction in the CD4/CD8 ratio (Supplementary Fig. 7G–J). By contrast, an increase in CD56+ NK cell frequencies were observed at 3–5 WPI (Fig. 5B). Further, all these parameters were normalized at 9 WPI, after ART treatment administration (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Fig. 7G–J). Thus, we speculate that failure to detect HIV load in 10 animals before ART was due to the low numbers of CD4+ T cells, which most likely precluded the production of detectable viral particles. Consistent with this hypothesis is the observed dynamics of the immune cells, which is compatible with HIV infection in animals with undetectable viral load.

Subsequently, we monitored the time to viral rebound after treatment discontinuation (until 13 WPI). We observed that the entire group of animals treated with Bi-Ab32/16 (n = 6) presented viral rebound, with a mean rebound time of 16 days after ART interruption. In contrast, only 4 out of 6 A32-treated mice experienced viral rebound, with a mean duration of 22 days. All vehicle-treated animals (n = 5) showed viral rebound, occurring at a mean of 15 days. (Fig. 5C). Further, after Bi-Ab32/16 administration, reduced percentages of CD56+ NK cells were observed in mice compared to A32 or vehicle control conditions (Fig. 5B). Additionally, CD56+ NK cell frequencies displayed a trend of negative correlation with HIV infection levels at the end of the experiment (Fig. 5D), while no significant associations were observed between CD4 frequencies and HIV infection levels (Supplementary Fig. 7K). Of note, to enhance data integrity and reliability, CD16 expression was excluded from the analyses due to potential interference from the Bi-Ab32/16 in CD16 staining. (Supplementary Fig. 7L). Collectively, our data indicate that in vivo treatment with Bi-Ab32/16 fosters a decline in CD56+ NK cells, a phenomenon that is inversely associated with HIV infection, thus negatively impacting viral rebound.

Bi-Ab32/16 modulates NK cell dynamics in vivo

To better understand correlates of time to viral rebound in the three groups of challenged mice, we analyzed by flow cytometry the phenotype of both blood and splenic NK cells at 11 and 13 WPI. Reduction of dimensionality and unsupervised clustering analysis using FlowSOM algorithm allowed us to identify seven different NK cell clusters with a particular expression of the selected receptors in peripheral blood (Fig. 6A). In blood, clusters #BC1 and #BC2 exhibited an activated memory-like phenotype, marked by the expression of NKG2C, and the activation markers CD69 and IFNγ (Fig. 6B). Cluster #BC1 presented elevated NKG2C levels and constituted a minor cluster at 11 WPI, with no significant inter-group differences in frequency (Fig. 6C). Conversely, at 13 WPI, Bi-Ab32/16 mice showed lower #BC1 frequencies compared to A32 and control groups (Supplementary Fig. 8A). Cluster #BC2 presented slightly reduced frequencies in Bi-Ab32/16 treated mice, was defined by dim NKG2C expression and higher IFNγ levels compared to A32 and control conditions, and showed a potential inverse association with HIV infection across all groups (Fig. 6B–D). Conversely, Bi-Ab32/16 treated mice presented slightly elevated #BC3 frequencies at 11 WPI, characterized by CD69 expression, absence of IFNγ, and a trend towards a positive association with HIV infection, compared to A32 and control groups (Fig. 6B–D). Although group differences were not evident at 13 WPI, #BC3 frequencies positively correlated with HIV-1 RNA levels (Supplementary Fig. 8B). Moreover, clusters #BC5 and #BC6 exhibited dim IFNγ expression, and presented a tendency towards an inverse association with HIV control (Fig. 6B). Notably, cluster #BC7, characterized by robust CD69 expression, exhibited lower frequencies in Bi-Ab32/16 treated mice compared to the A32 group at 11 WPI (Fig. 6C). Of note, some of the associations presented in Fig. 6D did not achieve statistical significance, likely due to sample size limitations; therefore, while the results suggest a potential relationship, definitive conclusions cannot be drawn from the current dataset. Similarly, reduction of dimensionality and unsupervised clustering analysis on NK cells derived from splenic tissue allowed us to identify eight distinct NK cell subpopulations (Fig. 6E, F). Although no statistically significant differences were observed in the frequency of these clusters among the study groups at 11 WPI, a subtle tendency towards lower frequencies of spleen clusters #SC2 and #SC8 was noted in the Bi-Ab32/16 treated group compared to the A32 group (Fig. 6G). Both clusters exhibited a tissue-resident NK cell phenotype, characterized by the expression of CD49a, CD69, and NKG2C, and lacked IFNγ expression (Fig. 6F). Notably, cluster #SC8 displayed strong NKG2C expression (Fig. 6F). In addition, at 13 WPI clusters #SC5 and #SC7 were found in higher frequencies in the Bi-Ab32/16 treated group compared to A32 and control groups, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 8C). Cluster #SC5 was defined by elevated expression of the tissue-resident markers CD49a and CD69, while cluster #SC7 exhibited high CD49a expression while lacking CD69 (Fig. 6F). Furthermore, cluster #SC7 presented high levels of IFNγ expression (Fig. 6F). Importantly, at 13 WPI, the presence of cluster #SC8 inversely correlated with HIV infection (Supplementary Fig. 8D).

A Opt-SNE representations showing the distribution of peripheral blood NK cell clusters, based on the expression of diverse phenotypic and functional markers in total (CD56+) NK cells by condition. B Heatmap depicting variations in the mean fluorescence expression of distinct NK cell phenotypic and functional markers between study conditions, corresponding to the different cell clusters identified in Fig. 5A. C Violin plots showing the frequency of the different cell clusters of NK cells identified in Fig. 5A by study condition. D Spearman correlations between the frequency of clusters (left to right): #BC2, #BC3, #BC5, and #BC6 in total (CD56+) NK cells and viral load expressed as RNA copies per ml of plasma. E Reduction of dimensionality representations showing the distribution of splenic tissue NK cell clusters, based on the expression of distinct tissue and functional markers in total (CD56+) NK cells by condition. F Heatmap depicting variations in the mean fluorescence expression of the different tissue and functional markers between study conditions, corresponding to the distinct cell clusters identified in Fig. 5E. G Violin plots depicting the frequency of the different cell clusters identified in 5E by study condition. Statistical comparisons were performed using Mann-Whitney test. Median with range (min-max) are shown. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Collectively, our findings suggest that the administration of Bi-Ab32/16 to Hu-NSG-Tg (IL-15) mice perturbs the NK cell landscape. Specific NK cell subsets expressing NKG2C and CD69 exhibit an inverse correlation with HIV infection in both blood and spleen, underscoring their potential role in HIV control in vivo.

Discussion

The development of novel therapeutic strategies aimed at eradicating the latent HIV reservoir represents a current priority in the pursuit of an effective HIV cure. In this study, we have shown that Bi-Ab32/16, a tetravalent bispecific antibody directed against CD16a on NK cells and the gp120 HIV protein (Ab A32) on HIV-infected cells, boosts NK cell cytotoxicity and mediates elimination of HIV reservoir cells in vitro. Our analyses revealed that Bi-Ab32/16 was able to significantly enhance the generation of NK-target cell conjugates, and activate NK cells to induce a potent and cytotoxic response against HIV infected cells. Importantly, Bi-Ab32/16 efficiently reduced the pool of latent HIV-infected cells after pharmacological viral reactivation, supporting its application in future “shock-and-kill” strategies. However, despite these promising in vitro results, a lack of HIV control was observed in vivo when Bi-Ab32/16 was infused to HIV challenged humanized NSG hu-IL-15 mice. Bi-Ab32/16 influenced specific NK cell populations, reducing total CD56+ NK numbers, negatively impacting HIV control. Consequently, we believe that Bi-Ab32/16 may be more suitable for ex vivo cell therapies or for administration at different stages of the infection, rather than direct infusion of the bispecific format in the context of ART interruption.

NK cells exhibit a diverse array of inhibitory and activating cell receptors, and the induction of a cytotoxic immune response is contingent upon a precise equilibrium in the expression of these receptors. Among them, CD16 has been reported to mediate ADCC activity46. We proved that CD16 stimulation by Bi-Ab32/16 promotes a shift on the phenotype of NK cells in vitro, resulting in an increase in the expression of CD16, together with the NKG2C and CD57 receptors. Prior studies provide substantial support for the crucial involvement of ADCC in regulating HIV infection as well as impacting the composition of the viral reservoir during treated infection42,46. Additionally, NKG2C receptor plays a key role in modulating the tolerance or reactivity of NK cells towards target cells47. Further, the preferential expression of CD57 by a subset of NK cells with a mature phenotype implies that this molecule may identify clonally expanded NK cells due to infections48,49,50. Of note, the expression of both NKG2C and CD57 has been associated with memory-like features, particularly evident in the context of CMV infection50. We speculate that these cells may represent subsets of activated NK cells with memory-like features, suggesting that the expansion of such cells could confer potential benefits for HIV control during the course of infection.

We demonstrated that direct CD16 engagement by Bi-Ab32/16 achieved a potent anti-HIV cytotoxic response in NK cells from PWH. Additionally, the elicited response was specific, as it was exclusively generated in the presence of the target protein gp120. This observation is significant, as persistent HIV infection has been associated with the emergence of dysfunctional NK cells characterized by a reduced capacity to eliminate cellular targets51. Notably, this NK cell exhaustion endures even in the presence of ART52,53,54. Therefore, these features position Bi-Ab32/16 as an appealing tool capable of redirecting and enhancing NK cell responses towards the mitigation of HIV infection. Importantly, in vitro, Bi-Ab32/16 was able to promote a NK-mediated clearance of HIV-latently infected cells following pharmacological reactivation, mimicking “shock-and-kill” assays. Latently HIV-infected cells are expected to undergo efficient elimination by the immune system upon viral reactivation. However, the reactivation of viral expression alone has proven insufficient for the complete eradication of cellular reservoirs7,55. Hence, optimal potentiation of the immune system is needed for the complete elimination of the latent reservoir. Previous studies have proposed that NK cells could contribute to the comprehensive clearance of viral-reactivated cells56,57,58,59. Our study provides evidence that Bi-Ab32/16 significantly diminishes the pool of reactivated latently infected cells through the induction of a robust NK cell immune response. Our findings are consistent with previous studies highlighting the potential of A32-based bispecific molecules to target and eliminate latently infected cells from PWH upon latency reversal60. Notably, while previous studies have identified HIV-mediated CD4 downregulation as an immune evasion mechanism limiting the efficacy of A32-based antibodies61,62, our experimental data confirms that our approach effectively targets the early stages of HIV infection, prior to significant CD4 downregulation. Variability in susceptibility to A32-mediated ADCC across studies can likely be attributed to differences in viral strains and infection protocols, including culture duration, strain-specific dynamics of CD4 downregulation, and prior cell activation. In our system, the partial preservation of CD4 expression on productively infected cells underscores the potential efficacy of A32-based bispecific antibodies, particularly in addressing early phases of HIV infection. Moreover, Bi-Ab32/16 treatment can impact the natural HIV reservoir, as evidenced by the decrease in intact proviruses within samples derived from PWH subsequent to viral reactivation. This is of relevance since the majority ( >90%) of latent viruses have been reported to harbor cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) escape mutations, resulting in infected cells that are unresponsive to CTLs targeting common epitopes63,64,65,66.

The predominant approach in preclinical HIV studies involves the utilization of well-established humanized mouse models such as the BLT mice67,68. However, these models exhibit limited support for robust development of human NK cells derived from human hematopoietic stem cells engraftment69. A major obstacle to effective human NK cell reconstitution is the absence of signaling through human interleukin-15 (IL-15), given the suboptimal stimulation provided by murine IL-15 to the human IL-15 receptor70. In this study, the selected animal model was NSG mice expressing a transgene encoding human IL-15, resulting in mice with physiological levels of human IL-15, which facilitates engraftment of human NK cells. Notably, this model has been previously characterized to sustain HIV infection, leading to elicited human NK cell responses in HIV-infected mice44. Consequently, this model stands as a robust and innovative platform for investigating NK cell responses in the context of HIV.

Unexpectedly, despite its excellent in vitro performance, Bi-Ab32/16 did not improve HIV control in treated mice. Notably, we detected a reduction in total CD56+ NK cells following prolonged Bi-Ab32/16 stimulation (2 weeks). Furthermore, a direct inverse correlation between the presence of CD56+ NK cells and viral load was observed in HIV-infected mice, providing evidence for the substantial role of NK cells in HIV infection control. As previously described, CD16 engagement is a strong activator of NK cell function, facilitating antigen-specific recruitment of NK cell responses71. Moreover, CD16 binds to the constant Fc domain of IgG antibodies, thereby triggering the ADCC response. Our results are consistent with previous reports that describe the association between NK cell-mediated ADCC responses and diminished viral set points in PWH20,57,71,72. However, the observations presented in our study are noteworthy, suggesting that sustained in vivo stimulation with Bi-Ab32/16, in the context of detectable viremia, may lead to an unexpected adverse impact on NK cells. Of note, an in vitro study demonstrated that multivalent, high-affinity binding of antibodies to CD16 poses a risk of cross-linking the receptor across multiple NK cells73. This cross-linking can trigger CD16a-mediated cytotoxicity, resulting in the depletion of the NK cell population. While the study noted that fratricide is less likely with antibodies containing only a single binding site for CD16a, it also highlighted that the proportion and extent of NK cell fratricide could be influenced by the antibody format and the variable domain order of the anti-CD16a antibody. These findings and ours underscore the critical need to carefully evaluate the long-term in vivo effects of bispecific antibodies like Bi-Ab32/16, particularly their impact on NK cell dynamics, to ensure that therapeutic strategies leveraging CD16-mediated mechanisms do not inadvertently compromise immune control of HIV infection.

Furthermore, in our study, the A32-treated group exhibited a delayed viral rebound compared to the Bi-Ab32/16-treated group, contrasting with the findings observed in vitro and highlighting an intriguing and potentially significant observation. The extended rebound time suggests that A32 may induce a more physiological response, potentially avoiding the adverse effects linked to the robust stimulation caused by the Bi-Ab32/16. These findings underscore the complexity of translating in vitro results to in vivo contexts, where immune dynamics and tissue distribution significantly influence antibody function. Our results are in line with other studies that reported the in vivo antiviral effect of non-neutralizing antibodies18 and with the fact that non-neutralizing IgGs targeting V1V2 epitopes were associated with protection in the RV144 clinical trial57. Moreover, our findings align with the ongoing development of A32-based bispecific antibodies (A32-CD3) for HIV cure strategies, exemplified by MGD014, which has progressed to human clinical testing (NCT03570918)74. The completed first-in-human Phase 1 safety study (NCT03570918) demonstrated the safety and tolerability of MGD014 in PLWH on ART, supporting the potential of A32-based bispecific antibodies for further clinical development to target persistent HIV infection.

A recent study evaluating the efficacy of two bispecific antibodies based on broadly neutralizing antibodies targeting Env and CD16, revealed robust and specific NK cell activation and subsequent reduction of HIV-infected cells in vitro40. These findings align with the results presented in our study. By contrast, preclinical evaluation of one of the bispecific antibodies in a Hu-NSG-Tg (IL-15) mice model, soon after ART initiation, demonstrated increased NK cell activity and reduced reservoir size. The opposite outcomes observed in vivo between this study and the present study raise questions regarding the optimal timing of intervention and whether the interruption of ART presents an adequate context for the successful targeting of NK cells. Furthermore, in Board et al., study, discerning between effector functions driven by CD16 engagement and neutralizing functions of the bispecific antibody during the non-suppressive ART period may be challenging. We hypothesize that the concurrent presence of viral replication after ART interruption, together with the sustained CD16 stimulation by the Bi-Ab32/16, may have influenced NK cell dynamics. This modulation could potentially induce prolonged immune activation, consequently resulting in a reduction in CD16 expression and cytotoxic function, thus leading to an ineffective clearance of HIV-infected cells. Furthermore, the utilization of the IL-15 NSG mice model, incorporating implanted human fetal thymic and liver tissue fragments in the aforementioned study, fully reconstituted the immune environment, which may have positively influenced NK cell functionality during the study. Comparative analyses with other models, such as the SHIV-AD8 infected non-human primate model, where NK-mediated control of viral rebound is evident at the time of ART interruption, offer valuable insights into the intricate dynamics of NK cell-mediated therapeutic strategies75.

In addition, some studies have indicated that the conformational state of Env glycoprotein significantly influences both antibody recognition and ADCC responses76,77,78. Engagement of CD4 receptor leads to a transition of Env to an “open” conformation, thereby sensitizing HIV-infected cells to ADCC responses mediated by non-neutralizing CD4-induced antibodies. However, HIV restricts Env-CD4 interaction by reducing CD4 expression and limiting Env accumulation on the surface of infected cells. We hypothesize that this limitation could be more pronounced in vivo, where the dynamic microenvironment and reduced bystander cell interactions may heighten sensitivity to CD4 loss, compared to in vitro systems where higher cell densities allow more frequent interactions between CD4 and the viral envelope. In this regard, small CD4-mimetic compounds (CD4mc) have been identified to alter Env conformation on HIV-infected cell surfaces, thereby exposing CD4-induced epitopes on viral particles and enhancing susceptibility of infected cells to ADCC by non-neutralizing antibodies. Recent investigations have demonstrated that co-administration of CD4-induced non-neutralizing antibodies or HIV+ plasma with CD4mc in HIV-infected humanized mice resulted in notable reductions in viral reservoir size across various tissues and delayed viral rebound77. In addition, strategies to address the challenge of a narrow window of opportunity could include the combination of distinct non-neutralizing antibodies, as suggested by previous studies79. Administering appropriate combinations of mAbs with diverse specificities could maximize the recognition and effective elimination of infected cells.

Overall, we hypothesize that strategies involving intermittent administration of the antibody upon ART withdrawal, ex vivo preloading of NK cells with Bi-Ab32/16, followed by the infusion of the complexed product into the person with HIV, or the co-administration of this bispecific format with NK cells during ART interruption, along with the addition of CD4mc could mitigate NK cell depletion, enhance ADCC responses, and potentially lead to optimal NK cell-mediated killing of HIV-infected cells. Our results underscore the relevance of avoiding in vivo NK cell overstimulation to attain more favorable biological outcomes. Still, the results presented here provide evidence for the beneficial effects of the Bi-Ab32/16 platform in the elimination of HIV-infected cells in vitro, reinforcing the role of CD16 NK cells in the control of HIV and the value of therapies directed to enhance their function.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

PBMCs from healthy donors were obtained from the Blood and Tissue Bank (Barcelona, Spain). The study protocol was approved by the Comitè d’Ètica d’Investigació Clínica (Institutional Review Board number PR(AG)350/2017) of the Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron (Barcelona, Spain). Samples were obtained from adults, who all provided written informed consent, and were prospectively collected and cryopreserved in the Biobank (register number C.0003590). All samples received were totally anonymous and untraceable. PBMCs from PWH were also obtained from the HIV unit of the Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron (Institutional Review Board number PR(AG)350/2017). All participants gave written informed consent for their participation in these studies. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed. The characteristics of the study participants are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Cells, antibodies, and reagents

PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-Plaque density gradient centrifugation and cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen. PBMCs were cultured in RPMI medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Gibco), 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Fisher Scientific), and 100 U/ml penicillin (Fisher Scientific) (R10 medium), and maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The cell line CEM.NKR CCR5+ was obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program (Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, from Dr. Alexandra Trkola)80,81. HIVBaL gp120 recombinant protein was obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program. The A32 antibody was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Program, NIAID, NIH (Cat#11438) from Dr. James E. Robinson82,83. The Bi-Ab32/16 antibody was designed by Dr. María J. Buzón and purchased at Fusion Antibodies PLC (Belfast, N. Ireland). Supplementary Table 1 shows the sequences of CD16a and HIV-1 Env, and Supplementary Table 3 shows the purification measures of the bispecific antibody. Interleukin-2 (IL-2) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. The anti-CD16 clone 3G8 was purchased from Stemcell. The pan-caspase inhibitor named Q-VD-OPh quinolyl-valyl-O-methylaspartyl-[–2,6-difluorophenoxy]-methyl ketone was purchased from Selleckchem.

Cell binding assays

We assessed the binding capacity of Bi-Ab32/16, A32 (anti-HIVgp120) and 3G8 (anti-CD16) antibodies to their targets by flow cytometry. The bispecific antibody concentration employed in the following experiments was previously established through the determination of the effective concentration (EC50) in a dose-response curve (refer to Fig. 3B). Specifically, a concentration of 0.2 μg/ml of Bi-Ab32/16 was utilized. For evaluation of Bi-Ab32/16 and A32, we used the CEM.NKR CCR5+ cell line. Briefly, cells were coated with 1 μg of the HIV-1 BaL gp120 recombinant protein during 1 h at room temperature (RT). After incubation, cells were washed in ice-cold R10 medium and staining buffer (PBS containing 3% FBS). Subsequently, cells were incubated for 20 min at RT in R10 medium with Bi-Ab32/16 (0.2 μg/ml) or A32 (5 μg/ml) antibodies, and stained with an anti-human FITC-labelled secondary antibody (dil 1:100) directed to the heavy chains on human IgG (Thermo Fisher) for detection of both antibodies (20 min at RT). To assess the targeting capacity of Bi-Ab32/16 and 3G8, NK cells were obtained from PBMCs of healthy donors by negative isolation using magnetic beads (MagniSort™ Human NK cell Enrichment Kit, eBioscience). NK cells were then incubated in R10 medium containing Bi-Ab32/16 (0.2 µg/ml) or the anti-CD16 PE-labelled 3G8 antibody (5 µg/ml). For detection of Bi-Ab32/16, we used an anti-human FITC-labelled secondary antibody (dil 1:100) (ThermoFisher). Cells were then fixed with paraformaldehyde solution (PFA; Affymetrix) (2%) and acquired in an LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Results were analyzed with FlowJo v10 software.

NK cell phenotyping

NK cells were isolated from cryopreserved PBMCs of healthy donors using a commercial kit (MagniSort™ Human NK cell Enrichment; eBioscience). Then, cells were incubated in R10 with 0.2 μg/ml Bi-Ab32/16 for 24 h at RT. The next day, NK cells were stained with LIVE/DEAD AQUA viability (Invitrogen) for 20 min at RT. After washing once with PBS 1X, cells were stained with anti-CXCR3-BV650 (G025H7, Biolegend) for 30 min at 37 °C. Next, cells were washed with staining buffer and stained with anti-CD57-PerCP-Cy5.5 (HNK-1, Biolegend), anti-CD56-FITC (B159, Becton Dickinson), anti-CD3-PE-Cy7 (SK7, Becton Dickinson), anti-NKp30-PE-CF594 (P30-15, Biolegend), anti-NKG2C-PE (134591, R&D Systems), anti-NKG2D-APC-Cy7 (1D11, Biolegend), anti-CD4-AF700 (RPA-T4, Becton Dickinson), anti-NKG2A-APC (Z199, Beckman Coulter), anti-CD16-BV786 (3G8, Becton Dickinson), anti-CD158b-BV605 (CH-L, Becton Dickinson) and anti-KLRG1–BV421 (14C2A07, Biolegend) antibodies in brilliant stain buffer (Beckton Dickinson) for 20 min at RT. Cells were then washed with staining buffer and fixed with 2% PFA. Samples were acquired on a BD LSR Fortessa flow cytometer and data was analyzed using FlowJo V10 and OMIQ software from Dotmatics (www.omiq.ai, www.dotmatics.com).

Cell-to-cell contact assays

CD4+ T cells and NK cells were isolated from cryopreserved PBMCs of healthy donors by commercial kits (MagniSort Human CD4+ T Cell Enrichment; Affymetrix, and MagniSort™ Human NK cell Enrichment; eBioscience). CD4+ T cells were coated with 1 μg of recombinant gp120 protein during 1 h at RT. After washing, CD4+ T cells were co-cultured with NK cells in a 1:1 ratio with Bi-Ab32/16 (0.2 µg/ml) for 20 min at RT. After the incubation, cells were stained with anti-CD56 (FITC; Becton Dickinson), anti-CD3 (PE-Cy7; Becton Dickinson), anti-CD16 (PE; Biolegend) and anti-CD4 (AF700; Beckton Dickinson) antibodies for detection of CD4+ T and NK cells. After 20 min incubation at RT, cells were washed and fixed with PFA (2%). Samples were then acquired on an LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and data were analyzed using FlowJo V10 software.

NK cell activation and functional activity assays

The activation and cytotoxic response of NK cells after stimulation with Bi-Ab32/16 was evaluated. NK cell cytotoxicity was assessed by the expression of CD107a and IFNγ. Briefly, NK cells were isolated from cryopreserved PBMCs from healthy donors by negative isolation using magnetic beads (MagniSort™ Human NK cell Enrichment Kit, eBioscience). CEM.NKR CCR5+ cells were coated with 1 μg of the HIV-1 BaL gp120 during 1 h at RT. Cells were then cultured at 1:1 ratio in R10 medium containing Bi-Ab32/16 (0.2 μg/ml), A32 (5 μg/ml) or 10 ng/ml PMA plus 1 μM ionomycin (positive control) for 4.5 h in a U-bottom 96-well plate at 37 °C and 5% CO2. BD GolgiPlug Protein Transport Inhibitor (Beckton Dickinson), BD GolgiStop Protein Transport Inhibitor containing monensin (Beckton Dickinson), and CD107a-PE-Cy5 (H4A3; Becton Dickinson) were also added to each well at the recommended concentrations. After incubation, cells were washed and stained with a viability dye (LIVE/DEAD Fixable Violet dead cell stain; Thermo Fisher) for 20 min at RT. Cells were washed with PBS 1X and stained with anti-CD56-FITC (B159; Becton Dickinson), anti-CD3-PE-Cy7 (SK7; Becton Dickinson), anti-CD69-PECF594 (FN50; Beckton Dickinson) and anti-HLA-DR-SB600 (LN3; eBioscience) antibodies for 20 min at RT. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized with Fixation/Permeabilization Solution (Beckton Dickinson) for 20 min at 4 °C, washed with BD Perm/Wash buffer and stained with anti-IFNγ-AF700 (Life technologies) for 30 min at 4 °C. Cells were then washed, fixed with PFA (2%) and acquired on an LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (Beckton Dickinson). Data were analyzed using FlowJo V10 and OMIQ software from Dotmatics (www.omiq.ai, www.dotmatics.com).

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) assays

The ADCC assay was conducted as previously described with certain modifications84. Briefly, CEM.NKR CCR5+ cells were used as target cells after being double-stained with PKH67 (Sigma-Aldrich) and eF670 (Labclinics) dyes following manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then coated with 1 μg of the HIV-1 Bal gp120 recombinant protein for 1 h at RT and extensively washed in ice-cold R10 medium. Target cells were dispensed in U-bottom 96-well plates and incubated 15 min in R10 medium containing distinct Bi-Ab32/16 or A32 antibody concentrations (0.001 μg/ml, 0.005 μg/ml, 0.01 μg/ml, 0.05 μg/ml, 0.1 μg/ml, 0.5 μg/ml, 1 μg/ml and 5 μg/mL). Plasma (1:1000 dilution) from a viremic (high viral load in blood) HIV+ participant was used as a positive control. NK effector cells were isolated from PBMCs of healthy donors or antiretroviral therapy (ART) suppressed HIV+ participants and added at 1:10 target/effector ratio. Plates were centrifuged and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After washing, flow cytometry count beads (AccuCount Blank Particles, Cytognos) were added to normalize cell collection to a constant number of particles (1000 events). Finally, cells were fixed with PFA (2%) and acquired on a LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (Beckton Dickinson). Data were analyzed using FlowJo V10 software. Target cells were identified through analysis in a PKH67 versus side scatter (SSC) plot. The percentage of killing was determined by the loss of the eF670 marker in an eF670 versus PKH67 plot.

Ex vivo infection of CD4+ T cells and functional ADCC assay

PBMCs from ART-suppressed PWH were thawed and incubated overnight in R10 medium containing 40U/ml of IL-2. The next day, CD4+ T cells were isolated using a commercial kit (MagniSort Human CD4+ T cell Enrichment; Affymetrix) and infected by spinoculation at 1200 g for 2 h at 37 °C with HIVNL4.3 (TCID50 = 78.125) or HIVBaL (TCID50 = 625) viral strains. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and cultured at 1 million/ml in a U-bottom 96-well plate with R10 containing 100 U/ml of IL-2 for the next 5 days. Five days after HIV infection, cells were placed in U-bottom 96-well plates. Autologous NK cells, previously isolated by negative selection using magnetic beads (MagniSort Human NK cell Enrichment Kit, eBioscience) from PBMCs, were then added at a 1:1 ratio. Cells were incubated in R10 medium containing 0.2 μg/ml of Bi-Ab32/16, 5 μg/ml of A32 or plasma (1:1000 dilution) from a viremic (high viral load in blood) HIV+ participant (positive control) for 15 min at RT. Plates were then centrifuged at 400 g for 3 min and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After incubation, cells were washed with PBS and stained with a viability dye (LIVE/DEAD Fixable Violet Dead Cell Stain; Thermo Fisher) for 20 min at RT. After, cells were washed with staining buffer and stained with anti-CD56-FITC (B159; Beckton Dickinson), anti-CD3-Pe-Cy7 (SK7, Beckton Dickinson), anti-CD4-AF700 (RPA-T4, Beckton Dickinson) for 20 min at RT. Cells were then washed with staining buffer, fixed and permeabilized with Fixation/Permeabilization Solution (Beckton Dickinson) for 20 min at 4 °C, washed with BD Perm/Wash buffer and stained with anti-p24-PE (KC57-RD1, Beckman Coulter) for 30 min on ice and 30 min at RT. Finally, cells were washed and fixed with 2% PFA. Samples were acquired in an LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (Beckton Dickinson) and analyzed using FlowJo V10 software. Target cell killing was calculated as the decrease in the population of infected (p24+) cells.

Viral reactivation in ART-suppressed PWH samples

CD4+ T cells from ART-suppressed PWH were isolated from PBMCs using a commercial kit (MagniSort Human CD4+ T cell Enrichment; Affymetrix) and cultured in R10 medium with Q-VD-OPh (Selleckchem) for 2 h in the presence of Raltegravir (1 μM), Darunavir (1 μM), and Nevirapine (1 μM) to prevent new rounds of viral infection. After 2 h, PMA (Abcam; 81 nM) plus ionomycin (Abcam; 1 μM) were added to the cell culture as a latency reversal agent and left for 18 h to reactivate latent HIV. After the incubation, cells were subjected to ADCC assays as described above. After, cells were stained with LIVE/DEAD Far Red viability for 20 min at RT. Cells were then washed with staining buffer and stained with anti-CD56-FITC (B159; Becton Dickinson), anti-CD3-PerCP (SK7, Becton Dickinson), and anti-CD8-APC (RPA-T8; Beckton Dickinson) for 20 min at RT. After the incubation, cells were fixed and permeabilized with Fixation/Permeabilization Solution (Beckton Dickinson) for 20 min at 4 °C, washed with BD Perm/Wash buffer and stained with anti-p24-PE (KC57-RD1, Beckman Coulter) for 30 min on ice and 30 min at RT. Finally, cells were washed and fixed with 2% PFA. Samples were acquired in a FACSCalibur (Beckton Dickinson) and AURORA (Cytek) flow cytometers.

NK killing of cells harboring intact provirus

CD4+ T cells from ART-suppressed PWH were isolated from PBMCs using the Dynabeads CD4 Positive Isolation Kit (Affymetrix) and cultured in R10 medium containing Raltegravir (1 μM), Darunavir (1 μM), and Nevirapine (1 μM) to prevent new rounds of viral infection. PMA (Abcam; 81 nM) plus ionomycin (Abcam; 1 μM) were added to the cell culture as a latency reversal agent and left for 18 h to reactivate latent HIV. The negative fraction of cells remaining from the CD4+ T cell isolation kit was cultured overnight in R10 medium supplemented with 100 U/mL of IL-2 (Merck) at a concentration of 2 M/ml. The next day, NK cells were enriched from the CD4 negative fraction using a commercial kit (MagniSort Human NK cell Enrichment Kit, eBioscience), Autologous NK cells were then cultured in R10 medium containing Raltegravir (1 μM), Darunavir (1 μM), and Nevirapine (1 μM) plus DNAse (100 μg/mL, Merck) and incubated in the presence of 0.2 μg of Bi-Ab32/16, 5 μg/ml of A32 or IgG2a isotype control at 0.2 μg/ml (MOPC-173, Biolegend) for 15 min at RT in U-bottom 96-well plates. After 18 h, reactivated CD4+ T cells were added at a 1:1 ratio and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. After the incubation, the remaining viable CD4+ T cells were isolated from the coculture using a combination of the EasySep Dead Cell Removal (Annexin V) Kit (StemCell Technologies) and the MagniSort Human CD4+ T cell Enrichment Kit (Invitrogen). The cell pellet was then lysed with proteinase K-containing lysis buffer and incubated at 55 °C overnight, followed by a 95°C incubation for 5 min, to obtain DNA for the Intact Proviral DNA Assay (IPDA) described below.

Intact proviral DNA assay (IPDA)

IPDA was performed as previously described (Bruner et al., 2019). Primers and probes specific for the Ψ HIV gene (HIV-1 Ψ forward 5′-CAGGACTCGGCTTGCTGAAG-3′, HIV-1 Ψ reverse GCACCCATCTCTCTCCTTCTAGC and probe 5′ 6-FAM-TTTTGGCGTACTCACCAGT-MGBNFQ-3′) and env HIV gene (HIV-1 env forward 5′-AGTGGTGCAGAGAGAAAAAAGAGC-3′, HIV-1 env reverse 5′-GTCTGGCCTGTACCGTCAGC-3′, HIV-1 env intact probe 5′-VIC-CCTTGGGTTCTTGGGA-MGBNFQ-3′, and HIV-1 anti-Hypermutant env probe 5′-CCTTAGGTTCTTAGGAGC-MGBNFQ-3′) were employed. The hRPP30 gene was used for cell input normalization. Samples were analyzed in a QIAcuity One 2-plex System (Qiagen).

Animal model

Animal studies were approved and assessed by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experimentation from the CMCiB (CSB-22-001) and count with the authorization of the Generalitat de Catalunya (code: 11505). All mouse experiments were conducted in a Biosafety Level 3 (BSL3) facility at the Comparative Medicine and Bioimage Centre of Catalonia (CMCiB). Hu-NSG-Tg (IL-15) NOD-scid IL2Rgammanull (NSG) female mice 4 weeks old were procured from the Jackson Laboratory. All procedures involving experimental animals were carried out in compliance with pertinent institutional and national animal welfare laws, guidelines, and policies. Mice were infected with 1 × 104 TCID50 of HIVBaL strain. Then, from 6 to 9 weeks post-infection (WPI) mice were placed on a diet combined with ART (87.5 mg/kg/day emtricitabine (FTC), 131 mg/kg/day tenofovir (TDF), and 175 mg/kg/day raltegravir (RAL) and darunavir (DRV))85. Subsequently, animals were randomized in three groups of n = 6 animals and received 500 µg of immunotherapy intraperitoneally twice a week (A32, Bi-Ab32/16 or PBS as a vehicle control) from 8 to 10 WPI. The experimental endpoint was set at 11- and 13-WPI, at which point the mice were sacrificed. Throughout the study, mice were subjected to weekly blood extractions. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

In vivo sample processing

Briefly, plasma and PBMCs were isolated from blood samples by centrifugation at 2000g for 20 min at 4 °C. Plasma was collected from the supernatant and transferred to 1.5 ml conical tubes. Samples were then lysed with RAV1 buffer (NucleospinTM RNA Virus kit, Cultek) and preserved at -80°C for further analysis. Remaining red blood cells present in PBMCs were lysed using ACK Lysis buffer (Fisher Scientific) following manufacturer’s instructions. Spleens were excised, minced into small pieces, and processed through a 70 μm cell strainer (Falcon). The obtained cells were employed for flow cytometry analysis described below. Of note, two spleen samples, from 11 WPI, one from the A32-treated group and one from the Bi-Ab32/16-treated group, were excluded from the final analysis due to an insufficient number of cells obtained after the experimental procedure (<50 cells). This criterion was applied to ensure the reliability and consistency of the data.

Viral load determination

Plasma viral load (pVL) was measured weekly to evaluate the suppression of viral replication in Hu-NSG-Tg (IL-15) mice. HIV RNA was extracted from plasma using NucleospinTM RNA Virus kit (Cultek, Macherey-Nagel) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA was performed with SuperScriptTM III Kit (Invitrogen) in accordance with the instructions provided by the manufacturer, and cDNA was quantified by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using primers and probes specific for the 1-LTR HIV region (LTR forward 5′-TTAAGCCTCAATAAAGCTTGCC-3′ and LTR reverse 5′-GTTCGGGCGCCACTGCTAG-3′; LTR probe 5′-CCAGAGTCACACACCAGACGGGCA-3′), and TaqManTM Gene Expression Master Mix (Thermo Fisher). Samples were analyzed in an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio5 system. Quantification of DNA was performed using a standard curve, and values were normalized to 1 million CD4+ T cells.

Longitudinal analysis of immune populations and NK cell phenotype by flow cytometry in HIV-infected Hu-NSG-Tg (IL-15) mice

For immune populations evolution, lysed blood and tissue samples were transferred to a V-bottom 96 well plate, washed with PBS, and stained with a viability dye (LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain; Thermo Fisher) for 20 min at RT in the dark. After, cells were centrifuged at 2600 rpm for 5 min, washed with PBS 1X and stained in a volume of 50 ul/well with anti-CD56-FITC (B159; Beckton Dickinson), anti-CD3-PE-Cy5 (UCHT1, Biolegend), anti-CD45-AF700 (HI30, Biolegend), anti-CD8-APC (RPA-T8, BD Biosciences), anti-CD16-BV786 (3G8; Beckton Dickinson) and anti-CD4-BV605 (RPA-T4, BD Biosciences) for 20 min at RT. After the cell surface staining, cells were washed with staining buffer, fixed and permeabilized with Fixation/Permeabilization Solution (Beckton Dickinson) for 20 min at 4 °C, washed with BD Perm/Wash buffer, and stained with anti-p24 PE (KC57-RD1, Beckman Coulter) for 20 min on ice and 20 min at RT. Finally, cells were washed and fixed with 2% PFA. For NK cell phenotyping, lysed blood and tissue samples were transferred to a V-bottom 96 well plate, washed with PBS, and stained with a viability dye (LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain; Thermo Fisher) for 20 min at RT in the dark. Then, cells were centrifuged at 2600 rpm for 5 min, washed with PBS 1X, and stained in a volume of 50 ul/well with anti-CD56-FITC (B159; Beckton Dickinson), anti-CD49a-PE-Cy7 (BA5b, Biolegend), anti-CD3-PE-Cy5 (UCHT1, Biolegend), anti-CD69-PE-CF594 (FN50, BD Biosciences), anti-NKG2C-PE (134591, R&D systems), anti-CD16-BV786 (3G8; Beckton Dickinson), and anti-CD45-BV605 (HI30, BD biosciences) for 20 at RT. After, cells were washed with staining buffer, fixed and permeabilized with Fixation/Permeabilization Solution (Beckton Dickinson) for 20 min at 4ªC, washed with BD Perm/Wash buffer, and stained with anti-IFNγ -AF700 (B27, Invitrogen) for 30 min at RT. Finally, cells were washed and fixed with 2% PFA. Samples were acquired in an LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using FlowJo V10 and OMIQ software from Dotmatics (www.omiq.ai, www.dotmatics.com).

Dimensionality reduction analysis

Dimensionality reduction analysis of flow cytometry data was performed using the OMIQ software from Dotmatics (www.omiq.ai, www.dotmatics.com). All events within pre-gated CD56+ NK cells were concatenated for each group per culture condition and analyzed. For NK cell phenotyping assays, cell clusters were identified by Flow-Self Organizing Maps (FlowSOM) artificial intelligence algorithm based on the expression of CD57, NKp30, NKG2C, NKG2D, NKG2A, CD16, CXCR3, CD158b, and KLRG1. For NK cell activation assays, FlowSOM identified cell clusters based on the expression of CD107a, IFNγ, CD69, and HLA-DR. For in vivo analyses, cell clusters were identified based on the expression of CD16, CD49a, CD69, and NKG2C markers. Next, optimized T-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (optSNE) analysis was employed to depict the identified clusters. Marker expression was represented as Archsin-transformed medians within heatmaps generated via optSNE analysis.

Study approval

Informed consent for sample collection and the use of medical record information was obtained from all participants included in the study. This study was approved by the corresponding Ethical Committees of the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital (VHUH), Barcelona, Spain (Institutional Review Board number PR(AG)270/2015). Animal studies were approved and assessed by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experimentation from the CMCiB (CSB-22-001) and count with the authorization of the Generalitat de Catalunya (code: 11505).

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 8.3 for Windows (GraphPad Software) and are reported within each figure legend. Volcano plots were automatically produced by the OMIQ software. Nonparametric Mann–Whitney U tests, Wilcoxon rank and ANOVA Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used as appropriate. For correlations, Spearman’s correlation coefficient was calculated. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data associated with this study are provided within the paper or the supplemental information. The source data behind the graphs in the paper can be found in Supplementary Data 1. Any other data is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Finzi, D. et al. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat. Med. 5, 512–517 (1999).

Vittinghoff, E. et al. Combination antiretroviral therapy and recent declines in AIDS incidence and mortality. J. Infect. Dis. 179, 717–720 (1999).

Finzi, D. et al. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science 278, 1295–1300 (1997).

Siliciano, R. F. & Greene, W. C. HIV latency. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 1, a007096 (2011).

Sengupta, S. & Siliciano, R. F. Targeting the latent reservoir for HIV-1. Immunity 48, 872–895 (2018).

Grau-Expósito, J. et al. Latency reversal agents affect differently the latent reservoir present in distinct CD4+ T subpopulations. PLoS Pathog. 15, e1007991 (2019).

Rasmussen, T. A. et al. Panobinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, for latent-virus reactivation in HIV-infected patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy: a phase 1/2, single group, clinical trial. Lancet HIV 1, e13–e21 (2014).

Rothenberger, M. K. et al. Large number of rebounding/founder HIV variants emerge from multifocal infection in lymphatic tissues after treatment interruption. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, E1126–E1134 (2015).

Jones, R. B. et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors impair the elimination of HIV-infected cells by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004287 (2014).

Pace, M. et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors enhance CD4 T cell susceptibility to NK cell killing but reduce NK cell function. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005782 (2016).

Vivier, E., Tomasello, E., Baratin, M., Walzer, T. & Ugolini, S. Functions of natural killer cells. Nat. Immunol. 9, 503–510 (2008).

Alrubayyi, A., Rowland-Jones, S. & Peppa, D. Natural killer cells during acute HIV-1 infection: clues for HIV-1 prevention and therapy. AIDS 36, 1903–1915 (2022).

Rezvani, K., Rouce, R., Liu, E. & Shpall, E. Engineering natural killer cells for cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. 25, 1769–1781 (2017).

D’Andrea, A. & Lanier, L. L. Specificity, function, and development of NK Cells, NK cells: the effector arm of innate immunity. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 230, 25–39 (1998).

Bryceson, Y. T., March, M. E., Ljunggren, H.-G. & Long, E. O. Synergy among receptors on resting NK cells for the activation of natural cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion. Blood 107, 159–166 (2006).

Marras, F. et al. Control of the HIV-1 DNA reservoir is associated in vivo and in vitro with NKp46/NKp30 (CD335 CD337) inducibility and interferon gamma production by transcriptionally unique NK cells crossm. J. Virol. 91, e00647–17 (2017).

Jost, S. et al. Antigen-specific memory NK cell responses against HIV and influenza use the NKG2/HLA-E axis. Sci. Immunol. 8, eadi3974 (2023).

Horwitz, J. A. et al. Non-neutralizing antibodies alter the course of HIV-1 infection in vivo. Cell 170, 637–648.e10 (2017).

Wang, W., Erbe, A. K., Hank, J. A., Morris, Z. S. & Sondel, P. M. NK cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 6, 368 (2015).