Abstract

ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) inhibitors emerge as a promising anti-cancer strategy, yet their causal effects across various cancer types remain unclear. Here, we employ a drug-target Mendelian randomization (MR) approach using four cis-expression quantitative trait loci for blood ACLY gene expression as genetic instruments to mimic ACLY inhibition. We utilize genetic data from the eQTLGen consortium (N = 31,684) for ACLY expression, the deCODE study (N = 35,559) for plasma proteome, and large-scale cancer genome-wide association studies consortia (N from 49,708 to 417,127) to investigate the association of genetically mimicked ACLY inhibitors with 17 cancers and identify potential mediating proteins. Genetically proxied ACLY inhibition is strongly associated with reduced melanoma risk (odds ratio [95% confidence interval (CI)]: 0.85 [0.78, 0.92]) in a combined analysis of two independent outcome datasets. Proteome-wide MR screening 1517 plasma proteins identifies 3 proteins associated with melanoma, with Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 (PARP1) showing strong colocalization support. Mediation analysis further suggests PARP1 as a mediator in the protective effect of ACLY inhibition on melanoma (mediated proportion [95% CI]: 51.52% [5.45%, 97.58%]). Follow-up and validation analyses support the robustness of these results. This study illuminates the therapeutic potential of ACLY inhibition in melanoma, with PARP1 implicated as a potential mediator, offering avenues for targeted interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) is a pivotal cytosolic enzyme that links heightened glycolysis to increased lipogenesis by catalyzing the conversion of mitochondria-derived citrate into acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA)1,2. Initially, ACLY inhibitors were investigated for their ability to reduce the synthesis of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), leading to their potential application in treating dyslipidemia and cardiovascular diseases3,4. However, as the role of metabolic reprogramming in cancer pathogenesis has become increasingly recognized, ACLY has emerged as a promising target for cancer therapy5. Aberrant ACLY upregulation has currently been observed in various cancers, including colorectal, lung, prostate, hepatocellular and pancreatic cancer, and melanoma6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Despite this prevalence, the therapeutic efficacy of ACLY inhibitors remains insufficiently studied and contentious across distinct cancer types14.

Recent studies have unveiled the immunological functions of ACLY inhibitors beyond their role in de novo lipogenesis. For example, ACLY inhibitors demonstrated the capacity to influence macrophage M1/M2 polarization, impacting both local and systemic inflammatory profiles15. Elevated ACLY levels in sepsis patients show correlations with pro-inflammatory markers, like interleukin-6, soluble E-selectin, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and lactic acid, indicating that inhibiting ACLY could potentially amplify the pro-inflammatory response of endothelial cells16. Moreover, ACLY regulation in upregulating programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in cancer cells has been linked to immunosuppression, compromising antitumor efficacy17. These studies explored the crucial mediating role of proteins in the intricate interplay of ACLY inhibitors on cancer pathophysiology. However, observational studies in this domain face inherent challenges, including biases stemming from confounding factors and the potential for reverse causation.

Mendelian randomization (MR) is a methodology employed to assess the causal effects of potential exposures on diseases by leveraging naturally allocated genetic variants at conception18,19,20. By exploiting genetic variants associated with drug-target messenger RNA (mRNA) expression, MR allows for the simulation of the long-term effects of drugs, analogous to a prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT)21,22,23. This method has been widely applied to estimate the clinical impact of pharmacological interventions, including lipid-modifying drugs on coronary heart disease, and is now extended in this study to assess the long-term effects of ACLY inhibition on the risk of common cancers24. Concurrently, large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have provided extensive datasets on plasma proteome, facilitating the systematic identification of candidate protein mediators25. The integration of proteome-wide MR analysis amplifies our ability to delve into the complex molecular landscape that underlies cancer pathophysiology. Utilizing a two-sample drug-target MR approach, our study seeks to assess the long-term effects of ACLY inhibition on cancer risks. Then, we integrated proteome-wide MR, multiple sensitivity analyses, colocalization, and mediation analysis to unravel the mediating roles of proteins in the intricate pathway from ACLY inhibition to specific cancer types.

Results

Study overview

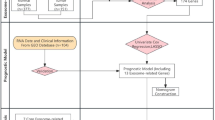

The study unfolded in two stages, as illustrated in Fig. 1. In the first stage, a drug-target MR method was applied to explore the relationship between ACLY inhibitors and the risk of 17 site-specific cancers. To genetically proxy ACLY inhibitors, cis-expression quantitative traits (cis-eQTLs) of blood ACLY expression served as genetic instrumental variables (IVs). We further investigated the effect of genetically proxied ACLY inhibition on lipid traits to confirm the validity of IVs. Cancer outcome data were obtained from two independent samples, namely the UK Biobank & Genetic Epidemiology Research on Adult Health and Aging (GERA) cohorts, as well as the FinnGen consortium. Results from these two outcome datasets were then combined using fixed-effects meta-analysis method. At this stage, evidence supporting the association between genetic mimicry of ACLY inhibition and melanoma was observed. Several sensitivity MR methods and explorations into the relationships of ACLY inhibitors with subtypes of melanoma and melanoma in situ were conducted.

ACLY ATP-citrate lyase, MR Mendelian randomization, MR-RAPS MR-robust adjusted profile score, MR-PRESSO MR-pleiotropy residual sum and outliers, PARP1 poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1. This figure was created with https://www.biorender.com/.

In the second stage, the focus shifted to identifying plasma proteins mediating the association between genetically proxied ACLY inhibition and melanoma. A two-step MR method was employed, where we first investigated the associations between 1517 circulating plasma proteins and the risk of melanoma using cis-pQTLs as genetic IVs of proteins (step 1 MR). The fixed-effect meta-analysis method was also employed to combine the estimated effects of proteins on melanoma from two melanoma datasets. Subsequently, we used the drug-target MR method to evaluate the relationships of genetically proxied ACLY inhibition with melanoma-associated proteins (step 2 MR). Two-step MR suggested that Poly [ADP-ribose] Polymerase 1 (PARP1) was a potential mediator. Multiple follow-up and validation analyses were performed to bolster the robustness of the result while mediation MR analysis quantified the proportion of the effect of genetically proxied ACLY inhibition on the risk of melanoma mediated via PARP1.

Validation for genetic IVs of ACLY inhibitors

As expected, our positive control analysis confirmed a robust association between genetically proxied ACLY inhibition and lipid profiles. Genetically proxied ACLY inhibition was linked to decreased levels of LDL-C (β [95% CI] per one standard deviation (SD) decrease in blood ACLY expression: −0.036 [−0.055, −0.017]; P = 2.08 × 10−4), triglycerides (TG; −0.041 [−0.059, −0.022]; P = 1.77 × 10−5), and apolipoprotein B (ApoB; −0.039 [−0.052, −0.026]; P = 9.80 × 10−9), coupled with increased levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C; 0.021 [0.009, 0.033]; P = 6.57 × 10−4) and apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1; 0.029 [0.016, 0.042]; P = 1.28 × 10−5; Supplementary Data 1). This association remained consistently strong, as seen in the scatterplot (Supplementary Fig. 1), and was reaffirmed through various MR methods, including weighted median, MR-robust adjusted profile score (MR-RAPS), and MR-pleiotropy residual sum and outliers (MR-PRESSO) methods (Supplementary Data 1).

Genetically proxied ACLY inhibition and cancer risks

Our primary analysis revealed a strong association between genetically proxied ACLY inhibition and melanoma risk (OR [95% CI] per one SD decrease in blood ACLY expression: 0.84 [0.75, 0.94]; P = 0.003). Additionally, suggestive associations were observed with pancreatic cancer (0.67 [0.46, 0.95]; P = 0.027), and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (0.81 [0.67, 0.98]; P = 0.027; Fig. 2A). The protective association between ACLY inhibitors and melanoma was independently replicated in FinnGen consortium (0.85 [0.75, 0.97]; P = 0.013; Fig. 2B). In the combined analysis of two outcome datasets, genetically proxied ACLY inhibition demonstrated a significant association with melanoma risk after Bonferroni correction (0.85 [0.78, 0.92]; P = 1.49 × 10−4; Fig. 2C), with no observed association with other site-specific cancers. Visual inspection of the scatterplot further supported the association between decreased blood ACLY expression and decreased melanoma risk in primary analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2). Scatterplots for other cancers can be found in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4. Concordant associations were observed using weighted median, MR-RAPS, and MR-PRESSO methods. Moreover, no evidence of heterogeneity for these analyses was observed (Supplementary Data 2).

A Primary analysis utilized the summary statistics of 17 cancers obtained from the UK Biobank and Genetic Epidemiology Research on Adult Health and Aging (GERA) cohorts. B Replication analysis utilized the summary statistics of 17 cancers from the FinnGen consortium (R9 version), the International Lung Cancer Consortium (ILCCO), the endometrial cancer association consortium (ECAC), and the deCODE genetic study. C Meta-analysis combined the ORs from primary analysis and replication analysis using fixed-effect model. OR [95% CI] represents the odds ratio for 17 common cancers per 1 SD decrease in blood ACLY expression. The dots represent OR from the two outcome datasets, while the diamonds represent OR from the combined dataset. I2 was used to measure the heterogeneity in the analysis. I2 values under 25% indicate mild heterogeneity, values over 50% suggest severe heterogeneity and between 25% and 50% the heterogeneity can be described as moderate.

To further explore the associations between ACLY inhibitors and melanoma, we investigated the effect of genetically proxied ACLY inhibitors on cutaneous melanoma, uveal melanoma, and melanoma in situ. Genetic mimicry of ACLY inhibition was associated with a reduced risk of cutaneous melanoma (0.73 [0.62, 0.86]; P = 0.0002) and melanoma in situ (0.73 [0.62, 0.86]; P = 0.017), but no significant association was observed with uveal melanoma (Supplementary Data 3).

Genetic profiling identified melanoma-associated proteins and pathways

In order to identify proteins associated with melanoma, we investigated the associations between 1517 circulating plasma proteins and melanoma. Genetic IVs for proteins associated with melanoma were detailed in Supplementary Data 4. In the combined analysis, genetically predicted levels of 123 proteins were nominally significant associated with melanoma (P < 0.05; Supplementary Data 5). After applying the Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (P < 3.18 × 10−5), genetically predicted levels of 3 plasma proteins exhibited strong evidence of association with melanoma (Fig. 3A). Specifically, genetically predicted protein O-glucosyltransferase 3 (POGLUT3; OR [95% CI] per 1-SD increase in protein levels: 0.81 [0.74, 0.88]; P = 2.97 × 10−6) and microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha (MAP1LC3A; 0.30 [0.17, 0.52]; P = 1.95 × 10−5) levels were inversely associated with melanoma, while genetically predicted PARP1 levels were positively associated with melanoma (4.23 [2.37, 7.56]; P = 1.12 × 10−6; Fig. 3A, B).

A Volcano plot of MR analysis of 1517 plasma proteins with the risk of melanoma. The black dashed line represents the Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold (P-value = 3.18 × 10−5), equivalent to Bonferroni cutoff of 0.05. The red dots represent the plasma proteins was significant positively associated with the risk of melanoma. The orange dots represent the plasma proteins was significant inversely associated with the risk of melanoma. B Forest plot of MR analysis of the associations between significant proteins and the risk of melanoma. C Colocalization analysis of the associations between significant proteins and melanoma. Two phenotypes were considered to have a strong support of colocalization if the PP.H4 was greater than 0.8. Medium colocalization indication was defined as 0.6 < PP.H4 < 0.8. GERA Genetic Epidemiology Research on Adult Health and Aging, POGLUT3 protein O-glucosyltransferase 3, MAP1LC3A microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha, OR odds ratio, PARP1 poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1, PP.H4 posterior probability of hypothesis 4.

In the GeneMANIA-constructed protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, the 3 MR-identified proteins and 20 potentially interacting genes were primarily connected through physical interactions and co-expressions (Supplementary Fig. 5). These genes enriched 18 pathways, with the top five being pentosyltransferase activity, double-strand break repair, SMAD binding, protein ADP-ribosylation, and DNA recombination (false discovery rate (FDR) corrected P-value < 0.05; Supplementary Data 6).

Among 3 proteins, only PARP1 had support of colocalization with melanoma (posterior probability for hypothesis 4 (PP.H4) = 64.10% for UK Biobank & GERA cohorts and PP.H4 = 88.91% for FinnGen consortium; Fig. 3C and Supplementary Data 7). The regional plot confirmed that rs1433574, the lead cis-pQTL for PARP1, was a causal variant for melanoma with a PP.H4 exceeding 60% for both outcome datasets (Fig. 4). Colocalization analysis of PARP1 cis-pQTL and eQTL within a ±500 kb windows around rs1433574 demonstrated a high probability of these pQTL and eQTL sharing a single causal variant (PP.H4: 97.4% for eQTLGen and 75.7% for GTEx; Supplementary Fig. 6).

Two phenotypes were considered to have a strong support of colocalization if the PP.H4 was greater than 80%. Medium colocalization indication was defined as 60% < PP.H4 < 80%. GERA Genetic Epidemiology Research on Adult Health and Aging, PARP1 poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1, pQTL protein quantitative trait loci.

For melanoma subtypes and melanoma in situ, genetically predicted levels of PARP1 were positively associated with cutaneous melanoma and melanoma in situ, while genetically predicted levels of POGLUT3 and MAP1LC3A were inversely associated with cutaneous melanoma (Supplementary Data 8).

Genetically proxied ACLY inhibition modulates PARP1 levels

Among 3 melanoma-associated proteins, drug-target MR showed that genetically mimicry of ACLY inhibition was associated with the levels of PARP1 (β [95% CI] per 1-SD decrease in blood ACLY expression: −0.059 [−0.107, −0.012]; P = 0.013; Fig. 5). No evidence of the relationships of genetically proxied ACLY inhibition with levels of POGLUT3 and MAP1LC3A were observed (Fig. 5). Scatterplots of the genetic associations with the proteins against the genetic associations with ACLY expression were provided in Supplementary Fig. 7. Other MR sensitivity analyses provided similar results (Supplementary Data 9).

The effects of genetically proxied ACLY inhibitors on 3 melanoma-associated proteins were represented as Beta [95% CI] per 1-SD decrease in blood ACLY expression. POGLUT3 protein O-glucosyltransferase 3, MAP1LC3A microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha, PARP1 poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1.

The ACLY inhibitor is a medication that lowers LDL-C levels26. To evaluate whether lower LDL-C could impact the levels of plasma POGLUT3, PARP1, and MAP1LC3A, we investigated the associations between LDL-C and levels of POGLUT3, PARP1, and MAP1LC3A. We found that genetically predicted lower LDL-C was associated with lower levels of PARP1 (β [95% CI] per 1-SD decrease in LDL-C levels: −0.060 [−0.113, −0.008]; P = 0.025; Supplementary Data 10).

Spearman correlation coefficients between ACLY and PARP1 mRNA expression levels were calculated across whole blood, skin not sun-exposed (suprapubic), and skin sun-exposed (lower leg) using genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) v8 datasets27. The analysis showed a strong positive correlation between ACLY and PARP1 expression levels in all three tissues (all r ≥ 0.60, all P < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 8).

PARP1 partially mediates the effect of ACLY inhibition on melanoma

Employing mediation MR analysis, we delved into the extent to which genetically proxied ACLY inhibition’s total effect on melanoma was mediated through plasma PARP1 (Fig. 6A). Figure 6B showed that PARP1 partially mediated the association between genetically mimicked ACLY inhibition and melanoma across two distinct outcome datasets: the UK Biobank and GERA cohorts, and the FinnGen consortium. Combing the outcomes from both datasets, we observed that plasma PARP1 levels accounted for a partial mediation of the total effect of ACLY inhibitors on melanoma risk (mediated proportion [95% CI]: 51.52% [5.45%, 97.58%]; P = 0.028; Fig. 6B).

A The principles of mediation MR analysis illustrated via directed acyclic graph. The black line represents the total effect of genetically proxied ACLY inhibitor on the risk of melanoma. The red line represents the effect of genetically proxied ACLY inhibitor on melanoma mediated via PARP1. The product of coefficients method was used to estimate the mediated effect and mediated proportion. To be specific, the mediated effect is calculated by multiplying the effect of ACLY expression on PARP1 (βACLY-PARP1) by the effect of PARP1 on melanoma (βPARP1-melanoma). The mediated proportion is calculated by dividing the mediated effect by the total effect (βACLY-melanoma). B The results of mediation MR analysis. The standard errors (SEs) of mediated effect were estimated using delta method.

The relationships of ACLY and PARP1 gene expression with melanoma in bulk and single-cell RNA-sequencing data

We analyzed bulk RNA-sequencing data from 461 skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM) cases and 558 healthy controls sourced from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and GTEx cohorts28. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed significantly higher mRNA expression levels of ACLY (Supplementary Fig. 9A) and PARP1 (Supplementary Fig. 9B) in SKCM skin tissues compared to normal skin tissues.

To further explore the roles of ACLY and PARP1 in melanoma, we analyzed single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from 3 acral melanoma cases, 2 cutaneous melanoma cases, and 2 healthy adults (datasets GSE215121 and GSE202352)29,30. After quality control, normalization, and integration using Seurat, the dataset included 43,158 cells and 45,823 genes. A total of 13 clusters was identified, including melanocytes, activated T cells, dendritic cells, dermal fibroblast-like cells, epidermal stem cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, endothelial cells, monocytes, melanocyte precursor cells, plasma cells, natural killer T cells and monocyte-derived dendritic cells (Supplementary Fig. 10A). Expression analysis revealed that ACLY (Supplementary Fig. 10B) and PARP1 (Supplementary Fig. 10C) were consistently expressed at lower levels in all cell types from healthy skin tissues compared to acral and cutaneous melanoma. This indicates aberrant upregulation of ACLY and PARP1 in melanoma, underscoring their potential roles in melanoma pathogenesis.

Discussion

ACLY emerges as a promising therapeutic target due to its strategic role in regulating fatty acid, cholesterol, and carbohydrate metabolism. This study is the first to assess the impact of ACLY inhibition on cancer risk, utilized cis-eQTLs as genetic instruments within a drug-target MR framework. Our findings indicate a protective effect of genetically mimicked ACLY inhibition on melanoma risk, consistently observed across two independent datasets, as well as in analyses of cutaneous melanoma and melanoma in situ. By employing proteome-wide MR, we expanded the limited research on melanoma-related target proteins, identifying PARP1, POGLUT3, and MAP1LC3A as potential candidates. Subsequent colocalization and mediation analyses highlight PARP1 as a key mediator in the pathway connecting ACLY inhibitors to melanoma susceptibility, suggesting its role in cellular processes could explain the protective effect of ACLY inhibition. These findings were validated through both bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing analyses. Together, they highlight the therapeutic potential of ACLY inhibitors and their downstream pathways in the treatment and prevention of melanoma.

The most extensive investigation into pharmacological ACLY inhibition in the clinical landscape is exemplified by the cholesterol-lowering trial using Bempedoic acid, involving 2230 individuals at high vascular risk with LDL-C levels surpassing 70 mg/dL. Administering Bempedoic acid daily over 52 weeks resulted in a significant reduction in mean LDL-C levels, demonstrating efficacy without adverse outcomes26. Building on these clinical insights, our study revealed that genetically proxied ACLY inhibition was consistently associated with lower LDL-C levels and improved lipid profiles, reinforcing the validity of these genetic instruments. The identified protective effect of ACLY inhibition on melanoma risk corroborates prior animal experiments by Guo et al., showcasing the upregulation of ACLY expression in melanoma and its role in promoting melanoma growth, along with the adaptive resistance to mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition6. Additionally, Chowdhury et al. reported that interleukin-12-stimulated CD8+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment rely on an ACLY-dependent glucose-citrate-acetyl CoA circuit to sustain function under nutrient-deprived conditions, further underscoring the metabolic significance of ACLY31. Despite in vivo and in vitro experiments hinting that ACLY’s antitumor effects through multiple pathways, population-based studies exploring its role in cancer have been notably scarce. Leveraging data from two independent cohorts, our study provided genetic evidence supporting the protective role of ACLY inhibition in melanoma, including melanoma in situ and cutaneous melanoma. Melanoma in situ represents the initial stage of skin cancer, while cutaneous melanoma is recognized as the most prevalent and aggressive form. This multifaceted evidence not only demonstrates the robustness of the association but also underscores the crucial role of ACLY inhibitors in combatting melanoma at various stages.

The second stage of our analysis, using cis-acting genetic variants among 1517 proteins, pinpointed PARP1, POGLUT3, and MAP1LC3A as melanoma-associated proteins. Functional analysis using the GeneMANIA tool revealed enriched pathways, including transferase activity, double-strand break repair, SMAD binding, protein ADP-ribosylation, and non-recombinational repair. As an abundant nuclear protein, PARP1 plays a well-established role in DNA damage recognition and repair32. Cellular processes such as apoptosis or necrosis, especially under pathological conditions or within the tumor microenvironment, will release intracellular contents into the extracellular space33,34. A possible explanation for the observed DNA repair effects and changes in plasma PARP1 levels in the mediation analysis is that ACLY inhibition disrupts metabolic reprogramming, leading to reduced oxidative stress and DNA damage35,36. This reduction in DNA damage decreases nuclear PARP1 levels, thereby attenuating its nuclear functions and simultaneously decreasing the amount of PARP1 released into the plasma during cell lysis37. Existing research supports the notion that lipid molecules can modulate PARP1 activity and expression, wherein oxidized cholesterol derivatives (e.g., 7-ketocholesterol and 15a-hydroxycholestene) and oxidized LDL promoting PARP1 induction via oxidative stress38,39. Elevated PARP1 levels have been implicated in carcinogenesis, as they are associated with key processes such as sustained proliferative signaling, tumor-promoting inflammation, and activation of invasion and metastasis through NF-κB pathway activation40,41. The observed positive association between PARP1 level and melanoma risk in our study aligns with previous allele-specific expression analyses identifying PARP1 as a susceptibility gene at the melanoma risk locus on chromosome band 1q42.142. Additionally, PARP inhibitors have shown efficacy in modulating vasculogenic mimicry melanoma characteristics and reduce metastatic spread43. These nuanced explorations offer preliminary insights into the intricate molecular pathways linking PARP1 protein functions to melanoma risk.

Concerning the other two proteins, POGLUT3 primarily functions in regulating protein quality and trafficking within the endoplasmic reticulum and has demonstrated inhibitory effects on glioblastoma stem cells44. However, its precise relationship with melanoma risk remains elusive, with a singular study suggesting that POGLUT3 may act as an essential gene in promoting the infiltration of M2 macrophages in melanoma45. Similarly, MAP1LC3A, a key autophagy molecule, has been implicated in cancer biology through transcriptional silencing caused by epigenetic changes in gastric cancer, osteosarcoma, and glioma46,47,48, as well as its roles in ferroptosis induction49,50. Nonetheless, colocalization analysis suggested the associations for POGLUT3 and MAP1LC3A might be confounded by linkage disequilibrium (LD). Thus, the protective role of these two proteins in melanoma still requires exploration.

This study exhibits several strengths, including the use of large-scale GWAS consortia for blood ACLY expression, proteome, and cancer outcomes, with robust results replicated across two independent outcome datasets. The extensive pool of plasma proteins and analyses of melanoma subtypes and melanoma in situ, further strengthen the results. Methodologically, the use of cis-acting variants in genes encoding ACLY helps minimize bias from directional horizontal pleiotropy, while drug-target MR accelerates clinical trial timelines and facilitates rapid pre-screening. In addition, summary-data MR and colocalization analyses, leveraging large-scale GWAS consortia, enhance statistical power and precision in estimating causal effects and posterior probability of colocalization. The inclusion of multiple sensitivity analyses rigorously assesses potential violations of MR assumptions, reinforcing the overall reliability of the study’s findings.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. Firstly, since genetic variants are typically fixed at conception, the genetic mimicry of ACLY inhibition is conventionally interpreted as reflecting the effects of decades-long ACLY inhibitor use. Therefore, drug-target MR estimates may not fully reflect the real-world effects of short-term drug treatments on cancer outcomes51. Second, while consistent cancer outcomes were retained in both cohorts during the preliminary screening, the study does not eliminate the possibility that ACLY inhibitors play distinct roles across various cancer subtypes and stages of progression. Third, the source of the IVs is limited by data availability. While liver tissue cis-eQTLs would provide better insight into the molecular mechanisms of ACLY inhibitors, the small liver sample size (N = 226) in the GTEx project yielded no significant cis-eQTLs. For solid tumors, ACLY IVs in various tissues may reflect associated lesions, but these were also constrained by limited tissue-specific data. Given that drugs typically exert their effects systemically, we used whole-blood ACLY expression (N = 31,684) as a proxy for ACLY inhibitor activity. Fourth, the PARP1-associated pathway may partially explain the link between ACLY inhibition and melanoma risk. Despite incorporating a broad range of blood proteins in this research, we may have unintentionally overlooked critical proteins lacking appropriate genetic instruments. For instance, the tumor suppressor gene CDKN2A, which encodes p16(INK4A) and p14(ARF), plays an important role in melanoma progression but their pQTL data was unavailable from the data source25. Future analyses are warranted when such data becomes available in larger-scale proteomics studies. Fifth, although we perform MR analysis across two independent datasets, the possibility of horizontal pleiotropy cannot be excluded due to the small number of IV and infeasibility to conduct MR-Egger test or MR-PRESSO global test. Finally, as the study used summary-level data from participants of European descent to avoid confounding by population heterogeneity across different ancestries, further validation was needed when generalized our results to other ethnicities.

Conclusions

In summary, this study illuminated the promising therapeutic potential of ACLY inhibition in combatting melanoma, supporting by evidence of a protein-mediated mechanism involving PARP1 in the pathway linking ACLY inhibition to melanoma risk. Further research should focus on rigorous evaluations through well-designed cohort studies spanning different stages of melanoma progression, as well as validation of the underlying mechanistic pathways using in vitro and animal model experiments.

Methods

Selection for genetic IVs of ACLY inhibitor

The exposure was blood ACLY gene expression. Summary statistics for the association between eQTLs and blood ACLY expression were derived from a large-scale meta-analysis of 31,684 blood samples by the eQTLGen consortium, with gene expression levels pre-processed using standardized methods (Supplementary Data 11)52.

MR analysis requires genetic IVs to meet three criteria: (1) association with the drug target (e.g., levels of drug-targeted protein or expressions of the encoding gene); (2) independence from confounders of the drug target-outcome relationship; and (3) influence on the outcome exclusively through the drug target21,53. Based on these criteria, we selected 9 cis-eQTLs associated with blood ACLY expression, with a genome-wide significant threshold of P < 5 × 10−8 and LD clumping at R2 < 0.1. 4 cis-eQTLs located within or near (±100 kb) the ACLY gene region were retained54 after excluding variants with cis-eQTLs with minor allele frequency (MAF) < 1% and F-statistics <10, ensuring minimal weak instrument bias55 (Supplementary Data 12).

Selection for genetic IVs of plasma proteins

For cancers significantly impacted by ACLY inhibitors, we investigated the specific plasma proteins that may mediate this association. Genetic association datasets for plasma protein levels were sourced from a GWAS in 35,559 Icelanders (mean age [SD]: 55 years [17 years]; 57% women) conducted by the deCODE study (Supplementary Data 11)25. Protein levels were measured using SomaScan version 4 assay (SomaLogic), which employs 4907 aptamers to quantify 4719 proteins. The protein levels were standardized using rank-inverse normal transformation25.

To minimize horizontal pleiotropy, we further used cis-pQTLs located within 1 Mb of the gene encoding the protein as genetic IVs to predict protein levels25. Common (MAF > 0.01) and independent (LD R2 < 0.001) cis-pQTLs genome-wide significantly (P < 5 × 10−8) associated with the levels of proteins were selected. Variants with F-statistics <10 were excluded. After harmonization, 3297 cis-pQTLs for 1517 plasma proteins were included in the analysis (Supplementary Data 13).

Study outcomes

The primary outcomes were 17 site-specific cancers, with lipids and apolipoproteins (LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, ApoA1, and ApoB) serving as positive control outcomes. Genetic association data for lipids or apolipoproteins were derived from a GWAS in the UK Biobank (N = ~400,000; Supplementary Data 11)56. Since melanoma was influenced by ACLY inhibitors, we considered cutaneous melanoma, uveal melanoma, and melanoma in situ as secondary outcomes to better explore the ACLY inhibitors’ relationship with melanoma.

For primary analysis, summary statistics for 15 site-specific cancers were obtained from a meta-analysis of cancer GWASs in the UK Biobank and GERA cohorts (N = 475,312)57. Genetic association estimates for liver cancer and colorectal cancer were obtained solely from the UK Biobank cohort (N = ~410,000)58,59. Cancer cases in the UK Biobank cohort were defined by International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 or ICD-10 codes, while GERA cancer cases were identified using the KPNC Cancer Registry based on ICD-O-3 codes57,58. For replication, summary statistics of 15 site-specific cancers were from individuals of European ancestry in FinnGen consortium (N = 377,277; R9 release data)60, while genetic estimates for lung cancer, endometrial cancer, and liver cancer were from international lung cancer consortium (N = 27,209)61, endometrial cancer association consortium (N = 121,885)62, and deCODE genetic study (N = 49,708)58, respectively. Cancer case definitions in replicated datasets were based on self-reported, doctor-diagnosed, ICD-8, ICD-9, ICD-10, and ICD-O-3 codes58,60,61,62. Controls were restricted to individuals who had no record of any cancer in both primary and replicated outcome datasets. Detailed information on cases and controls and description of data sources are available in Supplementary Data 11.

For secondary outcomes, summary-level dataset on the associations between SNPs and cutaneous melanoma was obtained from a GWAS in 456,348 individuals of European ancestry from UK Biobank cohorts (2824 cases and 453,524 controls)63. Data for melanoma in situ (887 cases and 286,876 controls) and uveal melanoma (242 cases and 299,884 controls) were from FinnGen consortium (Supplementary Data 11)60.

If a genetic IV (i.e., SNP) was missing in the mentioned outcome GWAS, it was replaced with a high LD proxy SNP (r2 > 0.8) identified using LDlink (https://ldlink.nci.nih.gov/). SNPs without suitable proxies were excluded. There was no sample overlap between GWASs of the ACLY expression, plasma proteins, and melanoma.

Validation for genetic IVs of ACLY inhibitors

Building on RCT findings that ACLY inhibitors reduce LDL-C and ApoB26,64, we conducted an MR analysis of genetically proxied ACLY inhibition on lipids and apolipoproteins to confirm that our IVs of ACLY inhibitor replicate the anticipated effects. Because of weak LD among the IVs of ACLY inhibitors (Supplementary Text 1), inverse-variance weighted (IVW) adjusted for correlation matrix between IVs was applied as primary method to assess the effects of genetically proxied ACLY inhibition on lipids and apolipoproteins. Additionally, a series of sensitivity MR methods were employed, including weighted median, MR-RAPS, and MR-PRESSO. Scatterplots depicting the genetic associations with the outcomes against the genetic associations with the ACLY expression were provided. Cochran’s Q test and I2 were performed to measure heterogeneity.

MR analysis of ACLY inhibitors on cancer risks

We employed the IVW method, incorporating a correlation matrix among the IVs of ACLY inhibitors, to examine the relationships between genetically proxied ACLY inhibition and risks of 17 site-specific cancers in both primary and replicated outcome datasets. Then, the results from two outcome datasets were meta-analyzed using the fixed-effect model. To better mimic ACLY inhibitors, the associations were expressed as ORs [95% CI] of cancers per one SD decrease in blood ACLY expression. To account for multiple testing, we applied the Bonferroni correction, with strong evidence determined when the combined association with a P-value below the threshold of 0.003 (0.05/17 site-specific cancers). Scatterplots illustrating genetic associations with cancer risks versus ACLY expression were presented. Weighted median, MR-RAPS, MR-PRESSO, and evaluation of heterogeneity were served as sensitivity methods.

MR analysis of plasma proteins on melanoma

To gain a deeper understanding of the impact of ACLY inhibitors on the risk of melanoma, we employed a two-step MR approach to identify plasma proteins mediating the effect of genetically mimicked ACLY inhibitors on melanoma. A proteome-wide MR was conducted to assess the causal effects of 1517 plasma proteins on melanoma risk across two outcome datasets (Fig. 1). For proteins with two or more IVs, we used the IVW method, while the Wald ratio method was applied to proteins with a single IV. The results from the two datasets were combined using a fixed-effect meta-analysis, with effects scaled to a one SD increase in plasma protein levels. To account for multiple testing using Bonferroni correction, the combined effect with a P-value < 3.18 × 10−5 (0.05/1517 proteins) was deemed significant. For proteins significantly associated with melanoma, we explored their associations with 3 secondary melanoma outcomes.

Colocalization analysis of melanoma-associated proteins with melanoma

We conducted Bayesian colocalization to test whether identified causal associations between proteins and melanoma were driven by LD. This analysis involved creating ±500 kb windows around the top cis-pQTL used as instruments for the identified proteins and integrating their summary statistics with melanoma within this region. Posterior probabilities of five hypotheses were quantified using approximate Bayes factor computation with default prior probabilities (p1 = 1 × 10−4, p2 = 1 × 10−4, and p12 = 1 × 10−5). We focused on hypothesis 4, which posits that both protein and melanoma share the same causal genetic variant within this region65. A PP.H4 ≥ 80% was deemed as high support of colocalization, while 60% < PP.H4 < 80% suggested medium support of colocalization. For protein colocalized with melanoma, we further assessed whether cis-pQTLs were influenced by eQTLs. Summary statistics for eQTL of PARP1 in whole blood were derived from eQTLGen consortium (N = 31,864) and GTEx v8 dataset (N = 670)27,52.

Function and network prediction among melanoma-associated proteins

GeneMANIA (http://genemania.org) was used to predict the networks and functions of genes encoding melanoma-associated proteins66,67. Briefly, GeneMANIA extends a list of query genes by incorporating functionally similar genes based on extensive genomics and proteomics data. Networks were then built with corresponding weights66,67. Enriched Gene Ontology classifications within this list were analyzed to infer gene functions66,67. Enriched function pathways with FDR-corrected P-values < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

MR analysis of ACLY inhibitors on melanoma-associated proteins

After identifying 3 proteins linked to melanoma, we explored the effects of genetically proxied ACLY inhibition on these proteins using IVW method incorporating correlation matrix method in step 2 MR. Findings with P-values < 0.017 (0.05/3 melanoma-associated proteins) were considered significant. Additionally, scatterplots, three MR sensitivity methods, and heterogeneity tests were also performed.

Given that ACLY inhibitors have been used in clinical trials to reduce LDL-C levels26,64, we investigated the effects of LDL-C on melanoma-associated proteins to validate the observed relationships between ACLY inhibition and the identified proteins. LDL-C was instrumented using independent (LD r2 < 0.001) and genome-wide significant variants from a GWAS of LDL-C in the UK Biobank cohort (N = 440,546)56. Results were scaled to one SD decrease in LDL-C levels.

Mediation MR analysis

When a protein influences melanoma risk and is also affected by ACLY inhibitor, it may play a potential mediating role in the association between ACLY inhibitor and melanoma. Mediation analysis was performed to estimate the proportion of the effect of ACLY inhibitors on melanoma mediated via PARP1 using network MR68. The product of coefficients method was employed to calculate the PARP1-mediated effect (Fig. 6A). This involved first estimating the effect of ACLY inhibitors on PARP1 (βACLY-PARP1) and then multiplying this by the effect of PARP1 on melanoma (βPARP1-Melanoma). The proportion of the total effect of ACLY inhibitors on melanoma (βACLY-Melanoma) mediated by PARP1 was then calculated by dividing the PARP1-mediated effect by the total effect. Standard errors (SEs) of mediated effect were estimated using delta method69. Since both primary and replication GWAS datasets for melanoma were available, mediated effects and proportions were estimated separately in the two datasets and subsequently combined for overall estimates. Further details regarding the mediation MR analysis can be found in Supplementary Text 1.

Validation analyses in bulk RNA-sequencing and single-cell RNA-sequencing datasets

To enhance the robustness of the findings, we performed validation analyses using bulk RNA-seq and scRNA-seq datasets. First, we validated the association between ACLY mRNA expression levels and PARP1 mRNA expression levels by calculating Spearman correlation coefficients for their mRNA levels in three tissue types from GTEx v8 dataset: whole blood (N = 670), non-sun-exposed skin (suprapubic; N = 517), and sun-exposed skin (lower leg; N = 605)27.

Next, we compared the expression levels of ACLY and PARP1 between SKCM and healthy skin samples. Bulk RNA-seq data from UCSC Xena (recomputed datasets from TCGA and GTEx cohorts) comprised 461 SKCM samples from TCGA and 558 normal skin samples from both TCGA and GTEx28,70. Briefly, the UCSC Xena platform processes RNA-seq data from TCGA and the GTEx project through a standardized pipeline to ensure consistency and comparability. This process involves aligning raw RNA-seq reads to the human reference genome using tools like STAR, followed by quantification of gene expression levels with software such as RSEM and Kallisto. The resulting data are normalized, often employing log2 transformation of FPKM values (log2(FPKM + 1)), to facilitate comparative analyses. Additionally, batch effect correction methods are applied to minimize technical variations between different projects and sequencing platforms. Differential expression was analyzed using ANOVA through the widely utilized GEPIA2 online tool (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index).

To further explore the expression patterns of ACLY and PARP1, we performed scRNA-seq analyses on skin biopsies from 3 acral melanoma cases, 2 cutaneous melanoma cases, and 2 healthy individuals. Single-cell transcriptomic data for 3 untreated acral melanoma sole samples, 1 untreated cutaneous melanoma neck sample, and 1 untreated cutaneous melanoma face sample were obtained from the GSE215121 dataset. Data from 2 healthy adult sole samples were retrieved from GSE202352. Cells with fewer than 300 or more than 4500 genes, over 20% mitochondrial genes, over 5% hemoglobin genes, or over 50% ribosomal protein genes were removed71. Subsequently, we performed integrated analysis of the 7 datasets from log-normalizing separately for each dataset, selected 3000 informative features, and performed integration using the FindIntegrationAnchors function. Subsequently, principal component analysis (PCA) method was used to reduce the dimensionality of gene expression data, capturing the most significant variations among cells. Cells were visualized using uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) algorithm. Then, Louvain algorithm was applied to unsupervised cluster cells with similar expression profiles and main cell types were annotated based on established marker genes. ACLY and PARP1 expression levels were visualized on a log2-transformed transcripts per 10 thousand +1 (TP10K + 1) scale using violin plots to compare expression levels across acral melanoma, cutaneous melanoma, and healthy control groups. Additionally, Kruskal–Wallis test was performed to compare the ACLY and PARP1 expression level among three groups.

Results from all analyses, except those mentioned before with multiple corrected P-value threshold, were considered significant if their P-values were less than 0.05. The analyses were performed using TwoSampleMR (v0.5.6), MendelianRandomization (v0.7.0), coloc (v5.1.0.1), MRPRESSO (v1.0), and Seurat (v5.1.0) packages in R software (v4.2.2), with all tests being two-sided. Reporting of the manuscript follows the STROBE-MR statement.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Summary statistics of eQTLs associated with blood ACLY gene expression were obtained from the eQTLGen consortium (https://eqtlgen.org/). In primary analysis, summary-level data of 17 site-specific cancers in primary analysis were obtained from publicly available GWASs (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/publications/32887889) and summary genetic data estimates for liver cancer were obtained from the UK Biobank cohort and deCODE genetic study (https://www.decode.com/summarydata). In replication analysis, summary genetic data estimates for 14 site-specific cancers were derived from the FinnGen consortium (https://www.finngen.fi/en/access_results) and summary statistics of lung cancer were derived from GWAS of ILCCO consortium (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets/ieu-a-966/). Additionally, summary statistics of endometrial cancer were obtained from the ECAC consortium (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/studies/GCST006464). Summary genetic data of proteome were obtained from deCODE genetic study (https://www.decode.com/summarydata/). Detailed sources of data were described in Supplementary Data S11. Bulk RNA-sequencing datasets were obtained from the UCSC Xena website (https://xenabrowser.net/). Single-cell RNA-sequencing data were obtained from GEO datasets (GSE202352 and GSE215121). Further information is available from the corresponding author upon request (zhenqian.wang@connect.polyu.hk).

Code availability

This manuscript used public software those are available online. The names of the software are presented in the “Methods” and the detailed statistical codes can be found in the related resources. Mendelian randomization analyses were conducted using the TwoSampleMR (version 0.5.6; https://mrcieu.github.io/TwoSampleMR/) and MendelianRandomization (version 0.7.0; https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MendelianRandomization/index.html) packages and genetic colocalization analyses were conducted using the coloc package (version 5.1.0.1; https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/coloc/index.html) in R version 4.2.2. Pathway enrichment analyses were conducted using GeneMANIA software (http://genemania.org/). Bulk RNA-seq analyses were performed using GEPIA2, while single-cell RNA-seq analyses were performed using Seurat package (version 5.1.0) in R version 4.2.2. The figure of study design was plotted in the biorender website (https://www.biorender.com/).

References

Bauer, D. E., Hatzivassiliou, G., Zhao, F., Andreadis, C. & Thompson, C. B. ATP citrate lyase is an important component of cell growth and transformation. Oncogene 24, 6314–6322 (2005).

Zhao, S. et al. ATP-citrate lyase controls a glucose-to-acetate metabolic switch. Cell Rep. 17, 1037–1052 (2016).

Pinkosky, S. L., Groot, P. H. E., Lalwani, N. D. & Steinberg, G. R. Targeting ATP-citrate lyase in hyperlipidemia and metabolic disorders. Trends Mol. Med. 23, 1047–1063 (2017).

Pinkosky, S. L. et al. Liver-specific ATP-citrate lyase inhibition by bempedoic acid decreases LDL-C and attenuates atherosclerosis. Nat. Commun. 7, 13457 (2016).

Jha, V. et al. Discovery of a new ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) inhibitor identified by a pharmacophore-based virtual screening study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 39, 3996–4004 (2021).

Guo, W. et al. ATP-citrate lyase epigenetically potentiates oxidative phosphorylation to promote melanoma growth and adaptive resistance to MAPK inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 2725–2739 (2020).

Hatzivassiliou, G. et al. ATP citrate lyase inhibition can suppress tumor cell growth. Cancer Cell 8, 311–321 (2005).

Qiao, C. et al. IGF1-mediated HOXA13 overexpression promotes colorectal cancer metastasis through upregulating ACLY and IGF1R. Cell Death Dis. 12, 564 (2021).

Wen, J. et al. ACLY facilitates colon cancer cell metastasis by CTNNB1. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38, 401 (2019).

Han, J. H. et al. Snail acetylation by autophagy-derived acetyl-coenzyme A promotes invasion and metastasis of KRAS-LKB1 co-mutated lung cancer cells. Cancer Commun. 42, 716–749 (2022).

Gao, Y., Islam, M. S., Tian, J., Lui, V. W. Y. & Xiao, D. Inactivation of ATP citrate lyase by Cucurbitacin B: a bioactive compound from cucumber, inhibits prostate cancer growth. Cancer Lett. 349, 15–25 (2014).

Husain, A. et al. Ephrin-A3/EphA2 axis regulates cellular metabolic plasticity to enhance cancer stemness in hypoxic hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 77, 383–396 (2022).

Carrer, A. et al. Acetyl-CoA metabolism supports multistep pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Discov. 9, 416–435 (2019).

Stine, Z. E., Schug, Z. T., Salvino, J. M. & Dang, C. V. Targeting cancer metabolism in the era of precision oncology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 141–162 (2022).

Lauterbach, M. A. et al. Toll-like receptor signaling rewires macrophage metabolism and promotes histone acetylation via ATP-citrate lyase. Immunity 51, 997–1011.e7 (2019).

Li, R. et al. ATP-citrate lyase controls endothelial gluco-lipogenic metabolism and vascular inflammation in sepsis-associated organ injury. Cell Death Dis. 14, 401 (2023).

Xiang, W. et al. Inhibition of ACLY overcomes cancer immunotherapy resistance via polyunsaturated fatty acids peroxidation and cGAS-STING activation. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi2465 (2023).

Sanderson, E. et al. Mendelian randomization. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2, 6 (2022).

Ference, B. A. et al. Mendelian randomization study of ACLY and cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1033–1042 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Women’s reproductive traits and ischemic stroke: a two‐sample Mendelian randomization study. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 10, 70–83 (2023).

Gill, D. et al. Mendelian randomization for studying the effects of perturbing drug targets. Wellcome Open Res. 6, 16 (2021).

Chauquet, S. et al. Association of antihypertensive drug target genes with psychiatric disorders: a Mendelian randomization study. JAMA Psychiatry 78, 623–631 (2021).

Wang, Z., Lu, J. & Hu, J. Association between antihypertensive drugs and hepatocellular carcinoma: a trans-ancestry and drug-target Mendelian randomization study. Liver Int. 43, 1320–1331 (2023).

Schmidt, A. F. et al. Genetic drug target validation using Mendelian randomisation. Nat. Commun. 11, 3255 (2020).

Ferkingstad, E. et al. Large-scale integration of the plasma proteome with genetics and disease. Nat. Genet. 53, 1712–1721 (2021).

Ray, K. K. et al. Safety and efficacy of bempedoic acid to reduce LDL cholesterol. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1022–1032 (2019).

GTEx Consortium. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 369, 1318–1330 (2020).

Goldman, M. J. et al. Visualizing and interpreting cancer genomics data via the Xena platform. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 675–678 (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. A single-cell analysis reveals tumor heterogeneity and immune environment of acral melanoma. Nat. Commun. 13, 7250 (2022).

Wiedemann, J. et al. Differential cell composition and split epidermal differentiation in human palm, sole, and hip skin. Cell Rep. 42, 111994 (2023).

Chowdhury, S. et al. Intracellular acetyl CoA potentiates the therapeutic efficacy of antitumor CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res. 82, 2640–2655 (2022).

Krishnakumar, R. & Kraus, W. L. The PARP side of the nucleus: molecular actions, physiological outcomes, and clinical targets. Mol. Cell 39, 8–24 (2010).

Mashimo, M. et al. The 89-kDa PARP1 cleavage fragment serves as a cytoplasmic PAR carrier to induce AIF-mediated apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100046 (2021).

Martí, J. M. et al. The multifactorial role of PARP-1 in tumor microenvironment. Cancers 12, 739 (2020).

Forrester, S. J., Kikuchi, D. S., Hernandes, M. S., Xu, Q. & Griendling, K. K. Reactive oxygen species in metabolic and inflammatory signaling. Circ. Res. 122, 877–902 (2018).

Chatzidoukaki, O., Goulielmaki, E., Schumacher, B. & Garinis, G. A. DNA damage response and metabolic reprogramming in health and disease. Trends Genet. 36, 777–791 (2020).

Kanai, M. et al. Inhibition of Crm1-p53 interaction and nuclear export of p53 by poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 1175–1183 (2007).

Mukhopadhyay, P. et al. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 is a key mediator of liver inflammation and fibrosis. Hepatology 59, 1998–2009 (2014).

Szántó, M., Gupte, R., Kraus, W. L., Pacher, P. & Bai, P. PARPs in lipid metabolism and related diseases. Prog. Lipid Res. 84, 101117 (2021).

Hochegger, H. et al. Parp-1 protects homologous recombination from interference by Ku and Ligase IV in vertebrate cells. EMBO J. 25, 1305–1314 (2006).

Hoesel, B. & Schmid, J. A. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol. Cancer 12, 86 (2013).

Choi, J. et al. A common intronic variant of PARP1 confers melanoma risk and mediates melanocyte growth via regulation of MITF. Nat. Genet. 49, 1326–1335 (2017).

Fernández-Cortés, M. et al. PARP inhibition promotes endothelial-like traits in melanoma cells and modulates pericyte coverage dynamics during vasculogenic mimicry. J. Pathol. 259, 318–330 (2023).

Tsai, Y.-L. et al. Molecular mechanisms of KDELC2 on glioblastoma tumorigenesis and temozolomide resistance. Biomedicines 8, 339 (2020).

Yan, K., Wang, Y., Lu, Y. & Yan, Z. Coexpressed genes that promote the infiltration of M2 macrophages in melanoma can evaluate the prognosis and immunotherapy outcome. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 6664791 (2021).

Bai, H., Inoue, J., Kawano, T. & Inazawa, J. A transcriptional variant of the LC3A gene is involved in autophagy and frequently inactivated in human cancers. Oncogene 31, 4397–4408 (2012).

Giatromanolaki, A. et al. Autophagy and lysosomal related protein expression patterns in human glioblastoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 15, 1468–1478 (2014).

Zhang, H. et al. Curcumin-loaded layered double hydroxide nanoparticles-induced autophagy for reducing glioma cell migration and invasion. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 12, 2051–2062 (2016).

Hou, W. et al. Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy 12, 1425–1428 (2016).

Zhou, B. et al. Ferroptosis is a type of autophagy-dependent cell death. Semin. Cancer Biol. 66, 89–100 (2020).

Gill, D. et al. Common pitfalls in drug target Mendelian randomization and how to avoid them. BMC Med. 22, 473 (2024).

Võsa, U. et al. Large-scale cis- and trans-eQTL analyses identify thousands of genetic loci and polygenic scores that regulate blood gene expression. Nat. Genet. 53, 1300–1310 (2021).

Yarmolinsky, J. et al. Genetically proxied therapeutic inhibition of antihypertensive drug targets and risk of common cancers: a Mendelian randomization analysis. PLoS Med. 19, e1003897 (2022).

Richardson, T. G. et al. Characterising metabolomic signatures of lipid-modifying therapies through drug target Mendelian randomisation. PLoS Biol. 20, e3001547 (2022).

Burgess, S. & Thompson, S. G. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40, 755–764 (2011).

Richardson, T. G. et al. Evaluating the relationship between circulating lipoprotein lipids and apolipoproteins with risk of coronary heart disease: a multivariable Mendelian randomisation analysis. PLoS Med. 17, e1003062 (2020).

Rashkin, S. R. et al. Pan-cancer study detects genetic risk variants and shared genetic basis in two large cohorts. Nat. Commun. 11, 4423 (2020).

Sveinbjornsson, G. et al. Multiomics study of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Genet. 54, 1652–1663 (2022).

Mbatchou, J. et al. Computationally efficient whole-genome regression for quantitative and binary traits. Nat. Genet. 53, 1097–1103 (2021).

Kurki, M. I. et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature 613, 508–518 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Rare variants of large effect in BRCA2 and CHEK2 affect risk of lung cancer. Nat. Genet. 46, 736–741 (2014).

O’Mara, T. A. et al. Identification of nine new susceptibility loci for endometrial cancer. Nat. Commun. 9, 3166 (2018).

Jiang, L., Zheng, Z., Fang, H. & Yang, J. A generalized linear mixed model association tool for biobank-scale data. Nat. Genet. 53, 1616–1621 (2021).

Nissen, S. E. et al. Bempedoic acid and cardiovascular outcomes in statin-intolerant patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 1353–1364 (2023).

Giambartolomei, C. et al. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004383 (2014).

Franz, M. et al. GeneMANIA update 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W60–W64 (2018).

Warde-Farley, D. et al. The GeneMANIA prediction server: biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W214–W220 (2010).

Burgess, S., Daniel, R. M., Butterworth, A. S. & Thompson, S. G. Network Mendelian randomization: using genetic variants as instrumental variables to investigate mediation in causal pathways. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 484–495 (2015).

Carter, A. R. et al. Understanding the consequences of education inequality on cardiovascular disease: Mendelian randomisation study. BMJ 365, l1855 (2019).

Vivian, J. et al. Toil enables reproducible, open source, big biomedical data analyses. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 314–316 (2017).

Clarke, Z. A. et al. Tutorial: guidelines for annotating single-cell transcriptomic maps using automated and manual methods. Nat. Protoc. 16, 2749–2764 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and investigators who contributed to the eQTLGen Consortium, deCODE genetic study, FinnGen consortium, UK Biobank cohort, Genetic Epidemiology Research on Adult Health and Aging (GERA) cohort, International Lung Cancer Consortium (ILCCO), Endometrial Cancer Association Consortium (ECAC), the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) program, and GTEx consortium. This research is supported by funding from the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province for Youths (2022JJ40689).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W.L., G.H.Y.L., Z.Q.W. and J.Y.H. contributed to the research questions and study design. J.W.L. and Z.Q.W. contributed to the data curation. Z.Q.W. and J.W.L. contributed to methodology development. J.W.L. and Z.Q.W. conducted statistical analyses. Z.Q.W., J.W.L. and J.Y.H. helped validation and performed sensitivity analyses. J.W.L., Z.Q.W. and G.H.Y.L. interpreted the results and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. Z.Q.W., J.W.L., G.H.Y.L. and J.Y.H. helped review and edit the final draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study is an analysis using publicly available bulk RNA-sequencing datasets, single-cell RNA-sequencing datasets, and summary-level data from genome-wide association studies (GWASs). All these studies had been approved by the relevant institutional review boards and participants had provided informed consents.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Rebecca Richmond and Christina Karlsson Rosenthal. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, J., Li, G.HY., Hu, J. et al. Genetic insights support PARP1 as a mediator in the protective association of ATP-citrate lyase inhibitors with melanoma. Commun Biol 8, 777 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07860-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07860-z