Abstract

Deficiency of short-chain enoyl-CoA hydratase (ECHS1), a crucial enzyme in fatty acid metabolism through the mitochondrial β-oxidation pathway, has been strongly linked to various diseases, especially cardiomyopathy. However, the structural and biochemical mechanisms through which ECHS1 recognizes acyl-CoAs remain poorly understood. Herein, cryo-EM analysis reveals the apo structure of ECHS1 and structures of the ECHS1-crotonyl-CoA, ECHS1-acetoacetyl-CoA, ECHS1-hexanoyl-CoA, and ECHS1-octanoyl-CoA complexes at high resolutions. The mechanism through which ECHS1 recognizes its substrates varies with the fatty acid chain lengths of acyl-CoAs. Furthermore, crucial point mutations in ECHS1 have a great impact on substrate recognition, resulting in significant changes in binding affinity and enzyme activity, as do disease-related point mutations in ECHS1. The functional mechanism of ECHS1 is systematically elucidated from structural and biochemical perspectives. These findings provide a theoretical basis for subsequent work focused on determining the role of ECHS1 deficiency (ECHS1D) in the occurrence of diseases such as cardiomyopathy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Short-chain enoyl-CoA hydratase (ECHS1) is a crucial enzyme involved in the mitochondrial β-oxidation pathway of fatty acid metabolism, where it contributes to fatty acid metabolism and to energy production in cells by catalyzing the reversible hydration of trans-2-enoyl-CoA intermediates into corresponding 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA products1,2. In addition, ECHS1 plays a significant role in isoleucine and valine catabolism by catalyzing the hydration of methacrylyl-CoA, as well as the conversion of acryloyl-CoA to 3-hydroxypropionyl-CoA3. Abnormalities in these reactions can disrupt the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) and the electron transport chain, resulting in metabolic and neurological disorders because both methacrylyl-CoA and acryloyl-CoA can spontaneously react with ECHS14,5. Furthermore, ECHS1 is also related to the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and ECHS1 deficiency (ECHS1D) can cause secondary OXPHOS dysfunction6.

Mutations in ECHS1 have been strongly linked to various diseases, especially ECHS1D. ECHS1D typically manifests at birth or in early childhood, and in some cases results in death within the first two days of life4,7. Notably, the neonatal onset/primary lactic acidosis phenotype has an extremely high mortality rate8,9. ECHS1D clinically presents as Leigh syndrome or Leigh-like syndrome with symptoms including hypotonia, metabolic acidosis, respiratory insufficiency, dystonia, epilepsy, optic atrophy, and developmental delay9,10,11,12,13. ECHS1 has wide substrate specificity, with the highest activity observed for crotonyl-CoA14. Thus, ECHS1 plays a vital role in vivo in regulating histone crotonylation (Kcr) and Kcr is relevant to cardiac disease. Therefore, ECHS1 contributes to cardiac homeostasis15,16. Some patients with mutations in ECHS1 also suffer from cardiomyopathy2,15,16. One of the reasons is the breakdown of normal histone acylation. In addition to playing a role in crotonylation, ECHS1 can also cause cardiomyopathy by enhancing histone acetylation17. Besides, many patients with primary mitochondrial disease of various types are prone to cardiomyopathy. Of course, some patients with ECHS1D were not reported to have cardiomyopathy, possibly due to different pathogenic mechanisms in patients with various mutations18,19. Additionally, ECHS1 has been identified as an oncogene or a biomarker in various human cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, gastric cancer and prostate cancer, and as a tumor suppressor in clear cell renal cell carcinoma20,21,22,23,24,25. Therefore, further research on ECHS1 is essential for providing more valuable insights into these diseases.

The crystal structure of rat liver mitochondrial ECHS1 in complex with acetoacetyl-CoA has been elucidated, revealing a hexameric assembly comprising six identical subunits26. This study provides a reference for the elucidation of the substrate recognition mechanism of human ECHS1. Moreover, this study confirms the importance of the glutamate residues at positions 164 and 144 (E164 and E144), which function as a catalytic acid that provides α-protons and as a catalytic base for the activation of water molecules in hydratase reactions, respectively26. Furthermore, this structure revealed a key spiral fold that functions as the CoA-binding pocket and preliminarily determines the substrate specificity of ECHS126,27. However, although the crystal structure of the human ECHS1–crotonyl-CoA complex has been solved (PDB: 2HW5), the binding ratio of ECHS1 and crotonyl-CoA is incorrect, which is the presence of only a single substrate molecule per ECHS1 hexamer. Therefore, the structural mechanism through which human ECHS1 functions remains largely unexplored, which limits our understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms associated with ECHS1D and diseases related to ECHS1D.

In this study, we employed cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to elucidate the apo form of human ECHS1 and ECHS1 in a complex with crotonyl-CoA. In addition, to further elucidate the mechanisms through which ECHS1 recognizes its substrates and through which substrate specificity is conferred, we determined the structures of ECHS1 in complex with various potential acyl-CoAs with fatty acid chains of different lengths, acetoacetyl-CoA, hexanoyl-CoA, and octanoyl-CoA, respectively. Based on a structural analysis, we engineered and purified ECHS1 mutants with point mutations at the site of substrate binding determined on the basis of the ECHS1 complex structures. Enzyme activity and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assays were conducted to evaluate the impact of these mutations on enzyme activity and substrate binding affinity. Moreover, we generated additional mutants based on variants observed in patients with ECHS1D and compared their enzyme activities with those of the wild-type enzyme. In conclusion, these data provide valuable and potential insights into the mechanism of disease occurrence related to ECHS1.

Results

Overall architecture of ECHS1

Mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) is the primary fatty acid metabolism pathway in the human body and plays a key role in maintaining energy homeostasis in the liver, heart, and skeletal muscle26. The FAO process consists of four essential steps: dehydrogenation, hydration, oxidation, and thiolysis. ECHS1 is involved in the FAO hydration step and converts enoyl-CoA to 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA through hydration. This step is important as it provides an avenue through which acetyl-CoA can enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Fig. 1a).

a ECHS1 catalyzes the hydration of trans-2-enoyl-CoA to 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA, the second step of the β-oxidation pathway. b, c Apo ECHS1 is shown in cartoon representation (b) or surface representation (c) from different orientations. The six monomers of ECHS1 are presented in different colors. d Diagram of the secondary structure of the ECHS1 monomer. The α-helices are marked as orange arrows, and the β-sheets are shown as blue cylinders. The boundaries between secondary structural elements are indicated by residue numbers. e Composition of the ECHS1 monomer. ECHS1 is composed of a spiral domain (yellow), two trimerization domains (orange), and a connecting domain (hot pink). The catalytic sites and signal peptides are indicated in the diagram. f Symmetry views of the ECHS1 monomer colored by domain are shown. The colors of each domain correspond to the colors in (e). Green represents the location of the amino-terminal starting region.

To mitigate the interference of the ECHS1 signal peptide sequence on the expression of human ECHS1 in Escherichia coli, we designed a construct containing amino acids 28–290, which was expressed and purified. Then we used a prokaryotic expression system to acquire the pure ECHS1. (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Static light scattering (SLS) analysis revealed that the size of the purified protein was ~160 kDa, which is consistent with the size of the ECHS1 hexamer. Notably, certain samples appeared to contain proteins of ~96 kDa in molecular weight, suggesting that ECHS1 may exist in a trimeric form in these samples (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1c). These results prompted us to conduct cryo-EM analysis to further clarify the actual composition of ECHS1.

Using a high-quality cryo-EM density map, the final ECHS1 structural model was built at a resolution of 2.18 Å. This structural model revealed that apo ECHS1 consists of six monomers (Supplementary Fig. 2), which interact tightly with each other, forming a stable conformation of a “dimer of trimers” (Fig. 1b, c). Furthermore, each ECHS1 monomer is composed of 8 β-sheets and 14 α-helixes (Fig. 1d), giving rise to distinct domains, such as a spiral domain and trimerization domain. The combination of secondary structure has more differences from the previous crystal structure (PDB:2HW5). The two trimerization domains are located at the C-terminus and connected by an α-helix connecting domain (Fig. 1e). Residues E144 and E164 serve as the catalytic sites of ECHS1 (Fig. 1e)26. Examination of the ECHS1 monomer domain structure revealed that it resembled a horse (Fig. 1f), with the C-terminal trimerization domain resembling the horse head. These findings suggest that ECHS1 comprises a “dimer of trimers” and further exerts hydratase activity.

The recognition mechanism of crotonyl-CoA and ECHS1

Crotonyl-CoA has been implicated in various crotonylation processes, especially histone crotonylation, which plays a vital role in more processes such as embryonic development in vivo28,29. Additionally, ECHS1 is essential for maintaining cardiomyocyte homeostasis in the heart by regulating crotonyl-CoA levels15.

Given that preliminary research, we next sought to investigate the structural and biochemical mechanisms through which kinetics of ECHS1 catalysis with crotonyl-CoA as a substrate (Fig. 2a). We employed SPR assay to assess the binding affinity of ECHS1 for crotonyl-CoA and established an enzyme activity assay to further confirm that crotonyl-CoA is an ECHS1 substrate. Using LC‒MS/MS, the reaction between ECHS1 and crotonyl-CoA was confirmed through the observation of corresponding hydration products (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Moreover, we verified that ECHS1 exhibits a binding affinity of 863 nM for crotonyl-CoA (Fig. 2b) and displays high enzyme activity toward this substrate (Fig. 2c).

a Chemical formula of crotonyl-CoA. b The binding affinity of ECHS1 for crotonyl-CoA was measured using surface plasmon resonance (SPR). The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) was determined to be 863 nM and is shown at the blue line. c ECHS1 enzyme activity assays were performed, and the results are shown as curves, with Kcat and Km calculated. d Structure of the ECHS1–crotonyl-CoA complex. The ECHS1 contains six pockets for crotonyl-CoA binding. The location of each crotonyl-CoA molecule is indicated with a red circle. e The crotonyl-CoA binding sites of ECHS1 are shown in detail. Residues that participate in hydrogen bond formation are highlighted in the window. Pale green and purple represent two adjacent monomers, and the crotonyl-CoA molecule is shown in wheat. f The amino acid residues involved in the formation of hydrophobic pockets around crotonyl-CoA are shown in detail. The residues in the hydrophobic pocket are shown in pale green and light blue, and the residues in the crotonyl-CoA pocket are shown in wheat.

Building upon these experimental findings, we incubated ECHS1 with crotonyl-CoA and prepared samples for cryo-EM analysis. Subsequent electron density data collection enabled us to construct a model that revealed the structure of the ECHS1–crotonyl-CoA complex at a resolution of 2.23 Å (Supplementary Fig. 3), where the product of 3-hydroxy form was not found. While a crystal structure of the ECHS1–crotonyl-CoA complex is available in the PDB database (PDB: 2HW5), the six ECHS1 monomers in this structure are bound to only one crotonyl-CoA molecule. Moreover, interactions at the acyl position are not visible in the crystal structure. Therefore, we hypothesize that this structure was prepared by soaking crotonyl-CoA into ECHS1 crystals. According to our structure, ECHS1 forms a 1:1 complex with crotonyl-CoA (Fig. 2d), which is a more plausible configuration than the previous crystal structure.

To identify the specific recognition mechanism between a single monomer of ECHS1 and crotonyl-CoA, we scrutinized the structure and identified that ECHS1 residues, K56, A96, A98, and I100, that interact with crotonyl-CoA through hydrogen bonds (Fig. 2e). Furthermore, we examined the interactions of the remaining five ECHS1 monomers with crotonyl-CoA and observed that each displayed distinct interactions with crotonyl-CoA such as hydrogen bonds between the ECHS1 residues K101, G141, and R197 and the substrate (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Notably, these interaction residues are conserved across different species (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Additionally, crotonyl-CoA engages in hydrophobic interactions with specific ECHS1 amino acid residues within a hydrophobic pocket in each ECHS1 monomer involved in crotonyl-CoA recognition and a neighboring ECHS1 monomer (Fig. 2f). Collectively, these observations elucidated the structural mechanism governing crotonyl-CoA recognition by ECHS1 and the kinetics of catalysis with this substrate.

Mechanism by which ECHS1 recognizes acyl-CoAs with different carbon chain lengths

ECHS1, which functions as a hydratase involved in short-chain enoyl-CoA metabolism, is expected to react with not only crotonyl-CoA but also other acyl-CoAs of different carbon chain lengths1.

To elucidate the mechanisms through which ECHS1 recognizes acyl-CoAs with different carbon chain lengths, we examined the binding affinity of ECHS1 with acetoacetyl-CoA, hexanoyl-CoA, octanoyl-CoA, and decanoyl-CoA, respectively. The SPR results revealed that ECHS1 exhibited slightly weaker binding affinities for these acyl-CoAs than for crotonyl-CoA, with KDs of 2.69, 2.57, and 2.64 μM observed for acetoacetyl-CoA, hexanoyl-CoA, and octanoyl-CoA, respectively. Interestingly, ECHS1 showed no binding affinity for decanoyl-CoA, indicating that ECHS1 predominantly interacts with acyl-CoAs <10 carbon atoms in length (Fig. 3a, b).

a The substrate molecules with different fatty acid chain lengths that were explored in this study. These include acetoacetyl-CoA, hexanoyl-CoA, octanoyl-CoA, and decanoyl-CoA. b ECHS1 shows a high binding affinity for the tested substrates with the exception of decanoyl-CoA. c–e The details of acyl-CoA recognition by ECHS1. The residues involved in hydrogen bond formation are indicated. Light blue represents the ECHS1 monomer, and purple represents the interacting residues. c Cyan represents acetoacetyl-CoA, d Green represents hexanoyl-CoA, e Dirty violet represents octanoyl-CoA. f The electron density of these substrates in the ECHS1–acyl-CoA complexes is shown. Wheat represents crotonyl-CoA, pink represents acetoacetyl-CoA, light pink represents hexanoyl-CoA, and pale green represents octanoyl-CoA. g Superimposed view of ECHS1 bound to different acyl-CoAs. Pale green represents the catalytic sites, light pink represents the surface of the monomer, yellow represents crotonyl-CoA, and purple represents octanoyl-CoA. Acetoacetyl-CoA and hexanoyl-CoA are shown in the same colors used in (c) and (d). h The electrostatic potential of the ECHS1 monomer surface and the binding conditions of ECHS1 with acyl-CoAs. Blue represents a positive charge potential, and red represents a negative charge potential. The colors of the substrates are the same as those in (g). N.D.: not determined.

Therefore, we next incubated ECHS1 with acetoacetyl-CoA, hexanoyl-CoA, and octanoyl-CoA and prepared samples for cryo-EM analysis. Subsequent model construction based on the electron density yielded the structures of these complexes at resolutions of 2.27, 2.55, and 2.29 Å, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 5–7). Analysis of this three ECHS1–acyl-CoA structures revealed that acetoacetyl-CoA formed hydrogen bonds with A98, I100, and G141 of the ECHS1 monomer; hexanoyl-CoA with K56, A96, A98, and I100; and octanoyl-CoA with A96, A98, I100, and G141 (Fig. 3c–f). These results suggest that these acyl-CoAs interact with ECHS1 in a pattern similar to that of crotonyl-CoA.

Further exploration of the specific interactions between ECHS1 and acyl-CoAs with different carbon chain lengths revealed that these ligands occupy similar positions when bound to ECHS1, notably between the catalytic sites E144 and E164. Although the conformations of these acyl-CoAs outside the pocket differ, their conformation within the interior of the pocket is conserved, with the only difference being the carbon chain length (Fig. 3g). Moreover, the negative electrostatic potential of the pocket increases the stability of acyl-CoAs within the pocket due to the interaction of ECHS1 with acyl-CoAs (Fig. 3h). This is because the ECHS1–acyl-CoA interaction mainly comes from the formation of hydrogen bonds, and the carbonyl oxygen of ECHS1 backbone and the hydroxyl oxygen of acyl-CoA participate in the formation of hydrogen bonds. This formation of hydrogen bonds can lead to a change in the charge distribution of the carbonyl carbon, and the electrons move to the oxygen of the carbonyl group, making the electronegativity of the carbonyl carbon increase, which leads to the formation of a negative potential at the recognition pocket. Enzyme activity assays showed that although ECHS1 bound these acyl-CoAs, no enzyme activity was observed, indicating that they are not enzymatic substrates of ECHS1, which was also consistent with the metabolic β-oxidation pathway (Supplementary Fig. 8). These data indicated that crotonyl-CoA is the active substrate of ECHS1 and that ECHS1 recognizes acyl-CoAs with a carbon chain length of <10.

Recognition-associated point mutations strongly affect ECHS1 function

Various factors influence the function of ECHS1, among which substrate recognition is crucial. Changes in the CoA-binding pocket in ECHS1 can lead to aberrant crotonyl-CoA recognition, directly impacting enzyme activity.

To investigate the effect of abnormal substrate recognition on ECHS1 function, we performed a structural comparison of the apo form of ECHS1 and the ECHS1–crotonyl-CoA complex. Structural alignment revealed a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.4 Å (Fig. 4a). Notably, the electrostatic interaction between crotonyl-CoA and ECHS1 causes the CoA-binding pocket to contract inward and adopt a “contracted” state. Interestingly, compared to crotonyl-CoA, octanoyl-CoA induces more pronounced conformational changes upon binding to ECHS1, particularly affecting residues K115–K118 (Fig. 4b). Comparison to the ECHS1–crotonyl-CoA complex revealed that residues F116 and L117 are pointed in the same direction in both complexes, whereas K115 and K118 are pointed opposite each other in the ECHS1–octanoyl complex. These structural differences influence the ECHS1 pocket conformation and potentially explain the lack of enzyme activity observed with octanoyl-CoA as a substrate (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, residues K115–K118 are similar in the ECHS1–acetoacetyl-CoA complex and the ECHS1–crotonyl-CoA complex. These results could also explain why ECHS1 cannot bind to decanoyl-CoA.

a Comparison of the three-dimensional structures of ECHS1 in its apo form and in complex with crotonyl-CoA. Pink represents the apo ECHS1 form, cyan represents the ECHS1–crotonyl-CoA complex form, and orange represents crotonyl-CoA. b Comparison of the three-dimensional structures of ECHS1 in its apo form and in complex with octanoyl-CoA. Residue-related conformational changes are shown as black dotted lines with arrows. Pale green represents the ECHS1–octanoyl-CoA complex, and light blue represents the apo form of ECHS1. c–h The binding affinity of ECHS1 with six different point mutations located around the CoA-binding pocket was assessed. The red line indicates the lack of an appropriate fitting result. i The enzyme activity assay results for each mutation are shown in the table with the calculated Km, Kcat, and activity relative to wild-type (WT). j The enzyme activities of the mutants are shown in the figure and compared with that of wild-type ECHS1. (n = 3, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. The data are presented as the means ± s.e.m.). WT wild-type, N.D.: not determined.

Leveraging the structural insights gleaned from our analysis of the ECHS1–crotonyl-CoA complex, we engineered ECHS1 with point mutations in amino acids crucial for crotonyl-CoA recognition and evaluated their impact on binding affinity and enzyme activity. We selected three different kinds of point mutations: K56A, A98G, and I100A, which are associated with hydrogen bond interactions; K101A and K282A, which are associated with salt bridge formation; and L117A, W120A, and F263A, which are associated with hydrophobic interactions. SPR assays demonstrated that mutations in these amino acid residues significantly affected the binding affinity between ECHS1 and crotonyl-CoA, rendering the binding affinity undetectable (Fig. 4c–h). Enzyme activity assays further revealed that the K56A, A98G, I100A, and L117A-W120A-F263A mutations reduced ECHS1 enzyme activity levels (Fig. 4i, j). Notably, the mutations K101A and K282A resulted in increased enzyme activity compared to that of the wild-type protein.

To explain these observations, we propose two hypotheses. First, the results of structural comparisons indicated that when ECHS1 binds crotonyl-CoA, the pocket constricts outward; mutations to alanine at these amino acid positions enlarge the pocket, which facilitates crotonyl-CoA entry and exit. Second, the electrostatic interactions of K101 and K282 with crotonyl-CoA stabilize its presence in the pocket, and mutations at these locations result in weakened interactions, promoting the easier expulsion of crotonyl-CoA. To test these hypotheses, we individually mutated K101 and K282 to glutamine and performed enzyme activity experiments. ECHS1 with the K101Q mutation exhibited reduced enzyme activity than that with the K101A mutation, while that with the K282Q exhibited increased activity than that with the K282A mutation. These activity levels were greater than those observed for wild-type ECHS1 (Fig. 4i, j). In conclusion, these findings indicate the effects of recognition-associated point mutations on ECHS1 function and the effect of epigenetic modification for ECHS1.

Mechanism for disease-associated point mutations on ECHS1 function

ECHS1 is intricately linked to various diseases, including Leigh syndrome and cardiac hypertrophy5,15, where ECHS1D arises due to mutations in crucial residues that impact ECHS1 expression or function, such as substrate recognition and enzyme activity30.

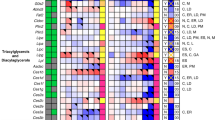

To elucidate how these disease-related point mutations influence ECHS1 levels, we scrutinized the ECHS1D mutations that have been reported and those identified in our own previous investigations (Fig. 5a). Among these mutations, V82L, A98T, Q104E, and G155S were identified through our previous studies, while the remainder have been reported in the literature. These mutations can be categorized into two groups: those located near the CoA-binding pocket in ECHS1 (N59S, A98T, Q104E, A138V, Q159R, and G195S) and those located away from this region (V82T and G155S) (Fig. 5b).

a The location of mutations identified in patients with ECHS1 deficiency. b Disease mutations labeled in the ECHS1 monomer. Pale cyan represents the ECHS1 monomer, and red represents the disease-related point mutations. The CoA-binding pocket is shown inside the square. c–h The binding affinity of ECHS1 with point mutations identified in patients with ECHS1 deficiency for crotonyl-CoA was assessed. The red line indicates that there is no appropriate fitting result. The KD value is shown as a blue line. i The enzyme activities of the six mutants identified from patients are shown compared to that of wild-type ECHS1 (n = 3. ns: not significant, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001. The data are shown as the means ± s.e.m.). N.D.: not determined.

These point mutations were subjected to biochemical characterization via SPR and enzyme activity assays to clarify their effects on ECHS1 and crotonyl-CoA recognition. We observed that mutations proximal to the CoA-binding pocket led to a substantial decrease in binding affinity to crotonyl-CoA, with some mutations completely eliminating binding to crotonyl-CoA (Fig. 5c–h). Enzyme activity of these mutates also markedly decreased (Fig. 5i). The relatively weaker impact of A98T on binding affinity could be attributed to its limited influence on the interactions between other residues of ECHS1 and crotonyl-CoA, which may preserve the CoA-binding pocket conformation. In contrast, other mutations induced conformational changes in the pocket, impeding the ability of ECHS1 to interact with crotonyl-CoA and execute its functions. The mutations V82T and G155S, which are located far from the CoA-binding pocket in ECHS1, had a less pronounced effect on substrate binding. However, enzyme activity was significantly decreased with these mutations, suggesting that these mutations may have altered the protein conformation surrounding the catalytic sites, thereby impeding ECHS1 function (Supplementary Fig. 9a, b). These results indicated that ECHS1D is associated with not only reduced ECHS1 expression levels but also reduced substrate binding efficiency and a reduction in the ability of the catalytic sites to perform their enzymatic function.

Discussion

ECHS1 is a pivotal enzyme that functions in the mitochondrial β-oxidation pathway of fatty acid metabolism and catalyzes the reversible hydration of trans-2-enoyl-CoA intermediates into corresponding 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA products, thereby facilitating the breakdown of fatty acids and cellular energy production. ECHS1 is strongly associated with various diseases, including Leigh syndrome and myocardial hypertrophy1. Here, to further explore the significance of ECHS1, the cyro-EM structure of ECHS1 was solved. ECHS1 has strong interactions between each monomer. And each ECHS1 monomer is composed of a spiral domain, trimerization domain, and connecting domain. Furthermore, ECHS1 can be viewed as a dimer of trimers. The ECHS1 monomer resembles a “horse”, with the C-terminal trimerization domain serving as the “horse head”. This reveals the overall structure of ECHS1 and the composition of the ECHS1 monomer using cryo-EM.

We examined the specific mechanism of ECHS1 substrate recognition and observed that while several acyl-CoA molecules can bind to ECHS1, ECHS1 can carry out catalysis with crotonyl-CoA. Other acyl-CoAs, such as acetoacetyl-CoA, hexanoyl-CoA, and octanoyl-CoA can also bind ECHS1 to form a complex, but decanoyl-CoA cannot. This is because the length of the carbon chain affects the ECHS1 function. If the acyl-CoA carbon chain is too long, the conformation of the CoA-binding pocket in ECHS1 may be affected. Notably, the enoyl-CoAs are not as stable as substrates in vitro; thus, they cannot be used for our enzyme activity assay. Totally, crotonyl-CoA is among the most specific substrates for ECHS1.

Another factor in addition to carbon chain length that can affect ECHS1 function is the presence of specific point mutations. To explore the factors that affect ECHS1 function by investigating point mutations in residues related to ECHS1 recognition. After mutating ECHS1 residues involved in the formation of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with crotonyl-CoA, ECHS1 lost the ability to bind crotonyl-CoA. The ECHS1 enzyme activity toward crotonyl-CoA also decreased significantly in these mutants. Furthermore, mutations at K101 and K282, which are involved in the formation of salt bridges, also resulted in the loss of ECHS1 binding to crotonyl-CoA, but the ECHS1 enzyme activity of these mutants was significantly elevated. Based on these results, we clarify the recognition mechanism of ECHS1 and acyl-CoAs and verify the effect of crucial residues by constructing point mutation. Notably, after K101 and K282 are mutated to alanine, the electrostatic interaction is weakened, and the binding affinity of crotonyl-CoA to ECHS1 is reduced, thus enhancing the “entry” and “exit” efficacy. Subsequently, we generated the point mutations K101Q and K282Q to simulate the acetylation and observed the enzyme activity increase. This condition suggested that the recognition between ECHS1 and acyl-CoAs is mainly related to epigenetic modification and steric hindrance. In summary, the recognition mechanism of ECHS1 and substrates is crucial and provides a kind of potential form for the connection of metabolism and epigenetics.

ECHS1D is associated with a variety of diseases, all of which are caused by point mutations in ECHS1. To explore how these mutations affect ECHS1 function from a structural and biochemical perspective, we constructed ECHS1 proteins with several pathogenic point mutations at the CoA-binding pocket and far from the CoA-binding pocket and analyzed the effects of these mutations on enzyme activity and substrate binding. The results showed that pathogenic point mutations at the CoA-binding pocket significantly decrease the binding affinity of ECHS1 for crotonyl-CoA and the corresponding enzyme activity. However, an increase in steric hindrance may reduce the efficiency of crotonyl-CoA. For the two disease-related point mutations V82L and G155S that are located further from the CoA-binding pocket, the binding affinity of ECHS1 for crotonyl-CoA was not affected, and the observed decrease in enzyme activity may be related to catalytic site inactivation triggered by conformational changes around the point mutation. In conclusion, there are many reasons why disease-related point mutations affect the function of ECHS1, and these data provide a theoretical basis for conducting drug design and treatment for potential targets of ECHS1D.

In this study, we mainly put forward high-resolution structure data about ECHS1 and complexes with other key acyl-CoAs. Furthermore, we also investigate the binding affinity and activity of ECHS1 with the fatty acid oxidation pathway substrates. This study systematically elucidates the functional mechanism through which ECHS1 functions from structural and biochemical perspectives, providing theoretical insight into how ECHS1D leads to the occurrence of diseases such as Leigh syndrome. Of course, ECHS1 also plays an important role in the valine metabolism pathway, with methacrylyl-CoA serving as its indispensable substrate within this process. It is meaningful that subsequent studies further emphasize the role of ECHS1 in the valine metabolism pathway, as this will also provide a more robust research basis for the exploration of the underlying causes of ECHS1D.

Methods

Cloning, expression, and purification of WT and mutant ECHS1 proteins

The ECHS1 gene sequence encoding residues 28–290 was chemically synthesized and optimized for codon usage. It was inserted into the pET-28a vector. The construct consisted of a 5’ ATG starting sequence, an Octa-histidine (8×) tag, a SUMO tag, and a terminal tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease site at the N-terminus. Other mutants were prepared based on the constructed plasmid. These plasmids were extracted from Escherichia coli DH5α cells and transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells for expression. The cells were cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium at a temperature of 37 °C until they reached an optical density of 0.6–0.8 at 600 nm. To induce ECHS1 expression, isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. The cells were then incubated at a lower temperature of 16 °C for 16–20 h to allow protein expression. To induce the expression of ECHS1, IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. The cells were then incubated at a lower temperature of 16 °C for 16–20 h to allow protein expression.

After the incubation period, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000 r/min for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting cell pellet was then resuspended in a lysis buffer consisting of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 500 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol. To lyse the cells, a high-pressure homogenizer operating at 700–900 bar was used. The lysates were cleared of cellular debris by centrifugation at 17,000 r/min for 1 h at 4 °C. The cleared supernatant containing the expressed protein was loaded onto Ni-NTA beads and washed with lysis buffer containing 50 mM imidazole to remove nonspecifically bound proteins. The bound protein was then eluted from the beads using a lysis buffer containing 500 mM imidazole. To remove the 8× His and SUMO tags, the eluted protein was incubated with TEV protease at 4 °C overnight. Subsequently, the protein solution was incubated with Ni-NTA beads again to remove the tags. The protein, which was free of SUMO and 8× His tags, was concentrated using a 10 kDa Centrifugal Filter Unit. Size separation of the protein was achieved using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column in SEC buffer (phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 2 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.67 mM KCl). The protein purity was assessed using 4–20% sodium dodecyl sulfate‒polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‒PAGE). Finally, the purified protein was concentrated for future use.

Cryo-EM sample preparation

For sample preparation, a total of 3 µL of the purified ECHS1 and ECHS1–acyl-CoA complex sample was applied to freshly glow-discharged 300 mesh R 1.2/1.3 holey carbon film Au grids. (The concentration of ECHS1 is 5.757 mg/ml, the incubation ratio is 1:5, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature) To remove excess samples, the grids were carefully blotted using Whatman No. 1 filter paper. A blot force of 2, a blot time of 4–5 s, and a wait time of 5 s were used during the blotting process to produce a thin protein sample layer on the grid. After blotting, the grids were rapidly frozen by plunge freezing into liquid ethane, which had been precooled with liquid nitrogen. The plunge freezing process was performed using a Vitrobot Mark IV. Plunge freezing allows rapid cooling of the sample, preserving its structural integrity in a vitreous ice state for subsequent cryo-EM analysis.

Cryo-EM data acquisition

The prepared grids containing the vitrified samples were clipped and loaded onto a 300 kV Titan Krios electron microscope equipped with an autoloader. Images were recorded using the EPU software, and raw movies were collected at a nominal magnification of 165,000×, which corresponds to a pixel size of 0.824 Å. A K3 camera31 was used for data acquisition. To exclude inelastically scattered electrons and improve the signal-to-noise ratio, a GIF Quantum energy filter with a slit width of 15 eV was utilized during image acquisition. The movies were acquired with the focal plane intentionally shifted slightly away from the optimal focus position with a defocus range of −1.0 to −3.0 μM. This defocus range helps to enhance the protein structure contrast and resolution. The total dose was 50 e–/Å2. Micrographs were collected for data acquisition. These micrographs were automatically selected by a blob picker, resulting in a dataset of particles.

Cryo-EM data processing, model building, and refinement

All dose-fractionated images were subjected to motion correction and dose weighting using MotionCor2 software32. The contrast transfer functions (CTFs) of the images were estimated using CTFFIND4 in CryoSPARC V4.3.133. The particles were automatically picked and subjected to two-dimensional (2D) classification. Subsequently, particles with suitable 2D averages obtained from the classification were subjected to ab initio classification, which categorized them into four distinct classes. Heterogeneous refinement was then carried out using the initial models generated from ab initio classification. Particles exhibiting high-resolution three-dimensional averages were selected and individually subjected to nonuniform refinement. Model building, refinement, and validation were performed using Coot34 and CCP-EM35. The results of cryo-EM data collection, model refinement, and statistical validation are shown in Table 2.

SPR assays

The binding affinities of ECHS1 and ECHS1 mutants for acyl-CoAs were verified using a Biacore 8K Plus instrument. ECHS1 and ECHS1 mutants were immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip. The channels of the experimental group contained acyl-CoAs that were diluted to different concentrations with PBS and allowed to flow through the chip. The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) values were calculated and analyzed by Biacore 8K Plus analysis software.

ECHS1 enzyme activity assay

ECHS1 enzyme activity was assessed using published methods36. Briefly, 1 ng of ECHS1 was added to a reaction mixture containing 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), 0.1 mg/ml BSA, and crotonyl-CoA. The progress of the reaction was monitored by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 263 nm.

SLS experiments

Static light scattering experiments were performed in PBS using a Superdex-200 10/300 GL size exclusion column (GE Healthcare). The concentration of AcrlF5 used was 0.6 mg/ml. The chromatography system was connected to a Wyatt DAWN HELEOS laser photometer and a Wyatt Optilab T-rEX differential refractometer. Wyatt ASTRA 7.3.2 software was used for data analysis.

LC‒MS/MS

The LC‒MS/MS system consisted of a 6500 plus QTrap mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, USA) coupled with an ACQUITY UPLC H-Class system (Waters, USA). An ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (2.1 × 100 mM, 1.8 μM, Waters) was used with mobile phase A (water with 5 mM ammonium bicarbonate) and mobile phase B (methanol). The linear gradient was as follows: 0 min, 0% B; 1.5 min, 0% B; 6 min, 95% B; 7.4 min, 95% B; 7.5 min, 0% B; and 10 min, 0% B. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min. The column chamber and sample tray were maintained at 40 and 10 °C, respectively. Data were acquired in multiple reaction monitoring modes for crotonyl-CoA and 3-hydroxybutanoyl-CoA with transitions of 836.0/329.2 and 854.0/347.1, respectively, in positive mode. The ion transitions were optimized using chemical standards. The nebulizer gas (Gas1), heater gas (Gas2), and curtain gas were set at 55, 55, and 30 psi, respectively. The ion spray voltage was 500 V. The optimal probe temperature was determined to be 500 °C, and the column oven temperature was set to 35 °C. The SCIEX OS 1.6 software was used for metabolite identification and peak integration.

Statistics and reproducibility

Experiments and statistical analyses were performed using the software Graphpad Prism 8.0. Detailed quantification methods and statistical analyses performed are described in the figure legends.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are included in the article and its Supplementary information files. And the PDB codes generated in this article are 8ZRU, 8ZRV, 8ZRW, 8ZRX, and 8ZRY. The supplementary information document contains all Supplementary Figs. (Supplementary Figs. 1–9), and original uncropped protein SDS–PAGE gel for Supplementary Fig 1b. Supplementary Data 1 presents the source data of Fig. 2b and c. Supplementary Data 2 contains the source data of Fig. 3b. Supplementary Data 3 presents the source data of Fig. 4c–h and j. Supplementary Data 4 contains the source data of Fig. 5c–i. All other data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Agnihotri, G. & Liu, H. Enoyl-CoA hydratase: reaction, mechanism, and inhibition. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 11, 9–20 (2003).

Haack, T. B. et al. Deficiency of ECHS1 causes mitochondrial encephalopathy with cardiac involvement. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2, 492–509 (2015).

Wanders, R. J. A., Duran, M. & Loupatty, F. J. Enzymology of the branched-chain amino acid oxidation disorders: the valine pathway. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 35, 5–12 (2012).

Bedoyan, J. K. et al. Lethal neonatal case and review of primary short-chain enoyl-CoA hydratase (SCEH) deficiency associated with secondary lymphocyte pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 120, 342–349 (2017).

Peters, H. et al. ECHS1 mutations in Leigh disease: a new inborn error of metabolism affecting valine metabolism. Brain 137, 2903–2908 (2014).

Burgin, H. J. & McKenzie, M. Understanding the role of OXPHOS dysfunction in the pathogenesis of ECHS1 deficiency. FEBS Lett. 594, 590–610 (2020).

Al Mutairi, F., Shamseldin, H. E., Alfadhel, M., Rodenburg, R. J. & Alkuraya, F. S. A lethal neonatal phenotype of mitochondrial short-chain enoyl-CoA hydratase-1 deficiency. Clin. Genet. 91, 629–633 (2017).

Ganetzky, R. D. et al. ECHS1 deficiency as a cause of severe neonatal lactic acidosis. JIMD Rep. 30, 33–37 (2016).

Ferdinandusse, S. et al. Clinical and biochemical characterization of four patients with mutations in ECHS1. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 10, 79–94 (2015).

Sakai, C. et al. ECHS1 mutations cause combined respiratory chain deficiency resulting in Leigh syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 36, 232–239 (2015).

Sun, D. et al. Novel ECHS1 mutations in Leigh syndrome identified by whole-exome sequencing in five Chinese families: case report. BMC Med. Genet. 21, 149 (2020).

Tetreault, M. et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies novel ECHS1 mutations in Leigh syndrome. Hum. Genet. 134, 981–991 (2015).

Yang, H. & Yu, D. Clinical, biochemical and metabolic characterization of patients with short-chain enoyl-CoA hydratase (ECHS1) deficiency: two case reports and the review of the literature. BMC Pediatr. 20, 50–60 (2020).

Yamada, K. et al. Clinical, biochemical and metabolic characterisation of a mild form of human short-chain enoyl-CoA hydratase deficiency: significance of increased N-acetyl-S-(2-carboxypropyl)cysteine excretion. J. Med. Genet. 52, 691–698 (2015).

Tang, X. et al. Short-chain enoyl-CoA hydratase mediates histone crotonylation and contributes to cardiac homeostasis. Circulation 143, 1066–1069 (2021).

Yuan, H. et al. Lysine catabolism reprograms tumour immunity through histone crotonylation. Nature 617, 818–826 (2023).

Cai, K. et al. Nicotinamide mononucleotide alleviates cardiomyopathy phenotypes caused by short-chain enoyl-CoA hydratase 1 deficiency. JACC: Basic Transl. Sci. 7, 348–362 (2022).

Marti-Sanchez, L. et al. Delineating the neurological phenotype in children with defects in the ECHS1 or HIBCH gene. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 44, 401–414 (2021).

Ozlu, C. et al. ECHS1 deficiency and its biochemical and clinical phenotype. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 188, 2908–2919 (2022).

Du, Z., Zhang, X., Gao, W. & Yang, J. Differentially expressed genes PCCA, ECHS1, and HADH are potential prognostic biomarkers for gastric cancer. Sci. Prog. 104, 1–14 (2021).

Li, R. et al. ECHS1, an interacting protein of LASP1, induces sphingolipid-metabolism imbalance to promote colorectal cancer progression by regulating ceramide glycosylation. Cell Death Dis. 12, 911 (2021).

Lin, J. F. et al. Identification of candidate prostate cancer biomarkers in prostate needle biopsy specimens using proteomic analysis. Int. J. Cancer 121, 2596–2605 (2007).

Shi, Y., Qiu, M., Wu, Y. & Hai, L. MiR-548-3p functions as an anti-oncogenic regulator in breast cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 75, 111–116 (2015).

Zhu, X. et al. Knockdown of ECHS1 protein expression inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation via suppression of Akt activity. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 23, 275–282 (2013).

Wang, L. et al. ECHS1 suppresses renal cell carcinoma development through inhibiting mTOR signaling activation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 123, 109750 (2020).

Engel, C. K., Mathieu, M., Zeelen, J. P., Hiltunen, J. K. & Wierenga, R. K. Crystal structure of enoyl-coenzyme A (CoA) hydratase at 2.5 angstroms resolution: a spiral fold defines the CoA-binding pocket. EMBO J. 15, 5135–5145 (1996).

Engel, C. K., Kiema, T. R., Hiltunen, J. K. & Wierenga, R. K. The crystal structure of enoyl-CoA hydratase complexed with octanoyl-CoA reveals the structural adaptations required for binding of a long chain fatty acid-CoA molecule. J. Mol. Biol. 275, 847–859 (1998).

Fang, Y. et al. Histone crotonylation promotes mesoendodermal commitment of human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 28, 748–763 (2021).

Sabari, B. R. et al. Intracellular crotonyl-CoA stimulates transcription through p300-catalyzed histone crotonylation. Mol. Cell 69, 533 (2018).

Nair, P. et al. Novel ECHS1 mutation in an Emirati neonate with severe metabolic acidosis. Metab. Brain Dis. 31, 1189–1192 (2016).

Thompson, R. F., Iadanza, M. G., Hesketh, E. L., Rawson, S. & Ranson, N. A. Collection, pre-processing and on-the-fly analysis of data for high-resolution, single-particle cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Protoc. 14, 100–118 (2019).

Zheng, S. Q. et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Burnley, T. Introducing the proceedings of the CCP-EM Spring Symposium. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 73, 467–468 (2017).

Stern, J. R., Delcampillo, A. & Raw, I. Enzymes of fatty acid metabolism. I. General introduction—crystalline crotonase. J. Biol. Chem. 218, 971–983 (1956).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC2703100 and 2023YFC3605504), the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Initiative for Innovative Medicine (2021-I2M-1-003), the National High-Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-D-002 and 2022-PUMCH-B-098), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82225007, 92149305 and 82030017). We thank Z.Y. and Z.X.W. for providing facility support at the Protein Preparation and Identification Facilities at the Technology Center for Protein Science, Tsinghua University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L., S.Z., and H.C. designed and supervised the study. G.S. performed the Static light scattering. G.S. and K.J. performed the protein purification, and B.C. performed the enzyme activity assay and LC–MS/MS. G.S., K.J., and B.C. performed the SPR assay. X.L. and Y.X. performed cryo-EM sample preparation and data collection. Y.X. processed cryo-EM data, built and refined the atomic model. G.S. performed structure analysis. K.J. assisted G.S. in finishing the manuscript writing and figure preparation. Y.J. participated in the manuscript and figure preparation. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Can Ozlu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Tuan Anh Nguyen and Laura Rodríguez Pérez. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, G., Xu, Y., Chen, B. et al. Structural and biochemical mechanism of short-chain enoyl-CoA hydratase (ECHS1) substrate recognition. Commun Biol 8, 619 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07924-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07924-0