Abstract

Transporter engineering is an effective strategy for enhancing the transmembrane transfer of target substrates and alleviating feedback inhibition in microbial cells. The LysE transporter, a key indicator of both L-arginine (L-Arg) and L-lysine (L-Lys) secretion in Corynebacterium glutamicum, plays a crucial role in the efficient synthesis of these amino acids. Owing to its broad substrate specificity, a LysE mutant with high substrate specificity for L-Arg extrusion is essential for achieving high production. In this study, we constructed a structural model and identified that LysE possesses a simplified structure of the characteristic LeuT-fold pattern, including parallel discontinuous helices, three highly conserved motifs, and several critical residues within its substrate binding pocket. Molecular docking and virtual site-saturation mutagenesis identified key hotspot residues for modulating LysE transport activity, with the A156Y and A156V mutants exhibiting significantly enhanced L-Arg extrusion. Iterative saturation mutagenesis at site L49 yielded the A156VL49T mutant, which was characterized by a 32.4% increase in growth under 30 g L−1 L-canavanine and a 17.4% reduction upon exposure to 0.3 g L−1 H-Lys-Ala-OH. With altered substrate specificity and improved efficiency in L-Arg extrusion, the A156VL49T mutant holds promise for metabolic engineering of C. glutamicum to enhance L-Arg production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During microbial production, efficient secretion of the target product is beneficial for alleviating feedback inhibition and cytotoxicity caused by accumulated final products1. To date, numerous transporters from different superfamilies have been identified, as shown to facilitate the extrusion of various compounds, including amino acids, inorganic ions, and organic ions2,3. As an essential component of the synthetic pathway, an efficient transporter can prevent intracellular accumulation of target compounds and mitigate product-induced feedback inhibition. Overexpression or deletion of transporters has been widely exploited in microbial cell factories, demonstrating its effectiveness in enhancing microbial production of desired products4,5,6.

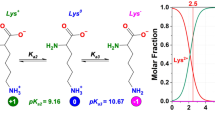

Corynebacterium glutamicum, a major producer of amino acids, is widely used owing to its biosafety, rapid growth, minimal nutrient requirements, and broad substrate spectrum7,8. Two transporters, LysE and CgmA, have been identified for L-arginine (L-Arg) extrusion in C. glutamicum, with LysE being the most important factor affecting this process6. In strain C. glutamicum with high L-Arg production, abundant L-Arg generally accumulates in the cells and causes serious feedback inhibition to the synthetic pathway. It has been demonstrated that enhanced L-Arg efflux efficiency via LysE overexpression can alleviate feedback inhibition by L-Arg, thereby increasing its production9,10. Alternatively, transporter engineering of the LysE transporter is another plausible way for enhancing L-Arg production. As a member of the L-Lys exporter superfamily (LysE), LysE naturally mediates the secretion of both substrates of L-lysine (L-Lys) and L-Arg. Therefore, designing a much specific transporter for L-Arg extrusion, i. e., reducing the efflux capacity of L-Lys and enhancing the efflux activity toward L-Arg, will be beneficial for the L-Arg extrusion and consequently boosting its production11.

The LysE superfamily in the Transporter Classification Database (TCDB) comprises 12 families, some of them involved in the transport of amino acids and/or their derivatives12. To date, solved structures of the LysE superfamily have revealed that the substrate-binding pocket is formed by a pair of discontinuous helices. For instance, the core of the substrate-binding site in the cytochrome C-type transporter (CcdA), a member of the disulfide bond oxidoreductase D family (DsbD) is comprised of two unwound segments in TMs 1 and 413. Despite the relatively simple structure of the six TMs and a pseudo-twofold symmetry axis formed by 3-TM repeats, this folding pattern closely resembles the well-characterized LeuT fold, which consists of 12 TMs, although the sequence identity is low14. Although with distinct differences in the protein length, these two parallel discontinuous helices have been demonstrated to be closely related to the substrate transport activity. Most prominently, some conserved motifs and sites were identified in these regions owing to their indispensable functions13,15,16,17,18,19.

Recently, transporter engineering has made significant contributions to improving transmembrane transfer efficiency and enhancing the production of target substrates20. Given the dual-substrate properties of the LysE transporter, this overexpression strategy may increase the accumulation of unintended byproducts. Alternatively, changing substrate specificity to generate more effective LysE mutants for L-Arg extrusion represents a promising strategy for enhancing L-Arg accumulation. In this study, a structural model with a concluding conformation is developed. Interestingly, the key structural feature of LysE is identical to the typical parallel discontinuous helices of the LeuT-fold pattern. Furthermore, several potential mutation hotspots were predicted using evolutionary conservation analysis and molecular docking, variants with improved L-Arg efflux activity and reduced L-Lys extrusion capacity were successfully generated.

Results

Growth complementation of Escherichia coli MG1655 deficient strains

Among the transporters identified in E. coli, ArgO mediates the extrusion of L-Arg, whereas LysO facilitates L-Lys transport21. To evaluate the ability of LysE to transport L-Arg or L-Lys, we first constructed two mutants lacking ArgO or LysO in the E. coli MG1655 strain. Furthermore, plasmid pEASY-P-LysE containing the native LysE promoter was constructed and transferred into the two knockout strains, resulting in the MG1655ΔargO-pEASY-P-LysE and MG1655ΔlysO-pEASY-P-LysE.

L-canavanine, a natural L-Arg analog, has been found to interfere with L-Arg utilization during protein synthesis and inhibit bacterial growth, including E. coli22. The ArgO transporter in E. coli mediates L-canavanine extrusion, effectively alleviating its inhibitory effects on cells. In this study, we used L-canavanine as the inhibitor to investigate the growth sensitivity of E. coli MG1655ΔargO-pEASY. Consistent with previous reports of impaired growth by L-canavanine22, E. coli MG1655ΔargO-pEASY exhibited a significantly inhibited growth as low as 0.03906 g L−1 of L-canavanine (Fig. 1a), while the wild-type strain of E. coli MG1655 grew well upon 1.25 g L−1 of L-canavanine. In contrast, transformation with the lysE gene conferred robust resistance to 5 g L−1 L-canavanine in the ArgO-deficient strains. For the complementary growth assay of L-Lys transport, we supplemented Medium A (MA medium) with H-Ala-Lys-OH, a dipeptide containing a readily catabolizable amino acid (L-Ala) and a non-catabolizable amino acid (L-Lys), which can lead to metabolic imbalance in cells when the L-Lys exporter is inactive6. As expected, strain MG1655ΔlysO was sensitive to 0.625 g L−1 H-Ala-Lys-OH (Fig. 1b) while LysE overexpression restored growth even at a high concentration of 10 g L−1 H-Ala-Lys-OH. These data indicated a markedly restored efflux capacity for L-Arg and L-Lys after introducing the LysE exporter and simultaneously confirming the suitability of these two strains for evaluating the efflux ability of subsequent LysE mutants.

Topological and three-dimensional structural models of LysE

For topological structure prediction of LysE, all software programs (TMHMM, HMMTOP, PHOBIUS, and SOSUI) suggested a structure comprising six TMs arranged in two sequence repeats, TM1–3 and TM4–6, connected by a 50-bp irregular coil (Fig. 2a). Subsequently, we used Alphafold2 for structure prediction and obtained a similar architectural arrangement for the six TMs. However, the predicted Local Distance Test (pLDDT) scores and Ramachandran plot quality for the full-length LysE model were relatively low (Supplementary Fig. S1). We suspected that the 100–136 fragment, which forms a long irregular coil between TM3 and TM4, contributes to this unreliability, as no analogous structures were found in homologous proteins (Fig. 2b). This fragment was then removed and a model with significantly improved reliability and accuracy was obtained (Supplementary Fig. S2). Notably, with two transmembrane-spanning discontinuous helices formed in TM1 and TM4 positioned parallel to each other, the LysE model appears to possess a typical structural pattern of the LeuT fold (Fig. 2b). Additionally, the orientations of these two discontinuous helices are consistent with the outward-occluded conformation of the LeuT fold, which is beneficial for further substrate docking analysis23.

Conservation analysis revealed key sites for substrate binding

To shed light into the key structural elements that mediate the transport of LysE substrates, we performed an evolutionary conservation analysis and identified a highly conserved region in each of the two inverse repeated domains of LysE (Supplementary Fig. S3). Consistent with the inaccurate region in the structural modeling, the irregular coil between TM3 and TM4 was the least conserved. Further analysis using WebLogo identified three conserved motifs, GxQN (Motif A, Fig. 3a), CxxSDxxL (Motif B, Fig. 3b), and TxLNP (Motif C, Fig. 3c), located in TM1, TM2, and TM4, respectively (Fig. 3d). In the structural model of LysE, Motif B is spatially close to Motifs A and C, collectively forming a substrate-binding pocket similar to that of CcdA, a cytochrome C-type transporter from the DsbD family within the LysE superfamily13. Notably, these positions are structurally identical to the residues responsible for leucine (Leu) and Na+ accommodation in the LeuT structure15, despite the lack of sequence identity between these two amino acid transporters. In the LeuT structure, most residues responsible for substrate recognition are located in TM1, TM3, and TM6, which are spatially analogous to the motifs identified in LysE, and many of these have been shown to participate in Leu binding and translocation16. Therefore, we propose that these three TMs, especially the three conserved motifs in the discontinuous helices, likely play an important role in substrate binding and translocation of the LysE exporter.

Molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation revealed critical sites for substrate binding

To identify potential substrate-binding sites in the LysE structural model, we initially utilized the CavityPlus web server to predict the active pocket for the accommodation of the substrate L-Arg or L-Lys. The predicted cavities for these two ligands were located within the discontinuous helices and were delimited by residues from TM1, TM2, and TM4. Furthermore, molecular docking was performed using Discovery Studio, and the stability of the resulting complex was validated through MD simulations. The root-mean-square-deviation (RMSD) and root-mean-square-fluctuation (RMSF) values both indicated that the complex was stable, supporting its suitability for further analysis (Supplementary Fig. S4). Superimposition of the CavityPlus-predicted pocket with the docked LysE structure showed high consistency, with the ligand fully embraced in the predicted cavity and all binding residues incorporated. In protein-ligand-anchored complexes, the main chain of L-Arg is exposed to the unwound region and anchored by multiple hydrogen bonds from TM1 and TM4 (Fig. 4a, b). Notably, most of these sites were adjacent to or even located within the three conserved motifs we identified, including residues Gly19 and Gln21 at Motif A, Asp46 at Motif B, and Asn153 at Motif C. Then, docking L-Lys into the LysE model revealed that the molecule adopts a similar orientation and shares many binding sites with those of L-Arg, merely with two additional sites at Leu15 and Asn22 that connect with the main chain of L-Lys, as well as the absence of an interaction between its lateral chain and Asp46 (Fig. 4c, d).

a, b Docked three-dimensional and topological complex of LysE with L-Arg. c, d Docked three-dimensional and topological complex of LysE with L-Lys. e Growth of mutants under various concentrations of L-canavanine. After being cultured at 37 °C for 24 h, the growth was monitored by measuring the OD600nm values. Data are from n = 3 independent experiments, Error bars represent SEM.

For the similar structural fold pattern of the LysE and LeuT transporters, we mapped the L-Arg-binding sites onto the LeuT structure (PDB 2A65), which is complexed with the Leu substrate23. Interestingly, the binding sites of L-Arg in LysE were conformationally identical to those of LeuT transporters, including the substrate orientation and structural locations. In the LeuT structure, the α-amino group of Leu accepts four hydrogen bonds from the TM1 broken helices (Ala22 of TM1) and TM6 (Phe253, Thr254, and Ser256)14. Correspondingly, the predicted residues interacting with the α-amino group of L-Arg are located at an equivalent position in LysE, including Leu14 in the TM1 broken helices, Ser17 in TM1a, and Asp159 of TM4a. Regarding the carboxyl group interaction, the predicted residues involved in L-Arg binding are contributed by the TM1 broken helices (Gly19) and TM4 residues (Asn153, Asn155, and Asp159). It is worth noting that the highly conserved residue Gly19 closely resembles Gly26 in the LeuT fold transporters by locating at the unwound region in the modest region of TM1 and forming a direct interaction with the carboxyl group of the substrate. Because Gly26 has been identified as a highly conserved residue in the signature motif GXG in the LeuT fold17, we proposed that this Gly may be designated as the signature residue in transporters with all LeuT-fold patterns, including LysE. In the lateral chain of L-Arg, we noticed that one α-amino group is anchored by a hydrogen bond from Asp46 of TM2, which is also a well-conserved residue in the LysE homologs. In the absence of such an interaction in the L-Lys molecule or at the corresponding position of LeuT, we hypothesized that this could be attributed to the long and polar side chain of L-Arg.

To investigate the functional roles of these putative sites in LysE transport, we performed site-directed mutagenesis of the sites involved in L-Arg binding and compared their resistance to L-canavanine toxicity. Interestingly, the efflux activity of the mutants derived from highly conserved residues (G19A, Q21A, D46A, N153A, and D159A) was significantly impaired, exhibiting a growth pattern similar to that of the strain carrying the empty plasmid (Fig. 4e). This indicates the indispensable functions of these sites and further confirms that they are likely involved in substrate binding, as predicted.

Saturation mutagenesis to improve the transport ability for L-Arg

Using L-Arg as the center, we selected residues within 0.4 nm of the ligand in the LysE-Arg complex and focused on 17 candidate amino acids (Leu14, Leu15, Ser17, Gly19, Pro20, Gln21, Asn22, Asp46, Leu49, Phe50, Asn153, Asn155, Ala156, Tyr157, Asp159, Ala160, Phe191). As anticipated, most of these residues were located within the three motifs identified in TM1, TM2, and TM4 or their peripheral regions. Using the Calculate Mutation Energy (Stability) module of Discovery Studio, alanine scanning revealed that most residues had the potential to alter the transport activity. Furthermore, virtual site-saturation mutagenesis based on these sites identified 11 residues: Leu15, Ser17, Pro20, Gln21, Asn22, Asp46, Leu49, Asn153, Asn155, Ala156, and Ala160 (Fig. 5a), which showed a high probability of enhancing protein stability. The site with the lowest mutation energy was selected for subsequent site-directed mutagenesis (Fig. 5b)24. After growth assay in the presence of L-canavanine, two mutants A156F and L49R, especially A156F, conferred E. coli MG1655ΔargO remarkably elevated resistance to high concentrations of L-canavanine (Fig. 5b).

a Mutated residues in the LysE structural model. b Growth of mutants in the MA medium containing various concentrations of L-canavanine. After being cultured at 37 °C for 24 h, the growth was monitored by measuring the OD600nm values. Data are from n = 3 independent experiments, Error bars represent SEM.

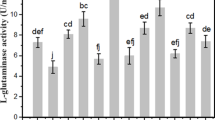

To further enhance the L-Arg efflux activity, site-saturation mutants involving site A156 were constructed, and their capacity for L-Arg transport was evaluated using an L-canavanine growth complementation assay. Of all the mutants, A156V, A156Y, A156F, A156W, and A156N showed significantly greater resistance to L-canavanine toxicity than wild-type LysE (Fig. 6a). Notably, the A156Y mutant exhibited the strongest resistance, with a 36.5% increase in growth relative to LysE, in the presence of 5 g L−1 L-canavanine (Fig. 6b). In contrast to A156Y, the growth of A156V upon 5 g L−1 L-canavanine treatment was identical to that of wild-type LysE, but became prominently robust at a lower concentration, with 46.9% increased growth in the presence of 2.5 g L−1 L-canavanine (Fig. 6a).

a Growth in the 96-well plate containing various concentrations of L-canavanine or b 5 g L−1 L-canavanine. c Growth in the 500-mL flask containing 5 g L−1 L-canavanine. d Growth in the 96-well plate containing various concentrations of H-Lys-Ala-OH. After being cultured at 37 °C for 24 h, growth was monitored by measuring the OD600nm values. Data are from n = 3 independent experiments, Error bars represent SEM.

To further determine the L-canavanine tolerance of these five mutants, we cultured them in a large-volume system of 500-mL flask containing 5 g L−1 L-canavanine (Fig. 6c). Consistent with the improved growth in the 96-well plate, A156V, A156Y, A156F, and A156W grew better and even much faster than wild-type LysE, with two prominent mutants, A156Y and A156V, which showed 71.4% and 48.7% growth increases after 36-h of cultivation. However, we also observed obvious discrepancies in the growth profiles of the A156F and A156N mutants. Mutant A156F exhibited faster growth than the others during the first 12-h of cultivation but decreased remarkably after 24-h. In contrast, the A156N mutation increased the sensitivity to L-canavanine toxicity and significantly decreased growth. Considering that these strains were cultured under high-speed conditions, and visible sediment was observed in the A156N and A156F cultures, we hypothesized that these two mutated proteins may be overexpressed under high dissolved oxygen conditions, which aggravates membrane protein toxicity to the cells25.

Because LysE transports both L-Arg and L-Lys, a LysE mutant with improved L-Arg specificity is attractive and beneficial for enhancing L-Arg productivity. We therefore transformed five positive mutations into the L-Lys transport deficient strain MG1655ΔlysO and evaluated their growth in the dipeptide-containing medium. Unlike their positive contribution to the transport activity of L-Arg, A156V, A156F, and A156N showed a 12.5%, 15.3%, and 10.5% reduction, respectively, in the presence of 10 g L−1 H-Lys-Ala-OH, implying a decreased ability of these mutants to transport L-Lys (Fig. 6d). As the A156F culture also produced visible debris and led to inaccurate OD values, we selected A156V, which showed enhanced transport activity for L-Arg and decreased activity for L-Lys, for further iterative saturation mutation (ISM). Also, A156Y was selected because of its excellent activity to extrude L-Arg.

A156Y- and A156V-based ISM of site L49

Among the 19 double mutants derived from A156V, A156VL49M, A156VL49T, A156VL49N, and A156VL49H displayed enhanced growth compared to LysE and A156V in the presence of 5 g L−1 L-canavanine (Fig. 7a, b). When the concentration of L-canavanine was increased to 30 g L−1, the four double mutants also conferred robust resistance to the strain, with A156VL49T being the most effective, showing a 32.4% increase in growth compared to that of the wild-type LysE (Fig. 7c). With the exception of the mutant A156VL49M, which exhibited improved growth in the presence of H-Lys-Ala-OH, the other three mutants showed a slight decrease in growth under a wide range of H-Lys-Ala-OH (Fig. 7d). Especially, under 0.3125 g L−1 concentration, the mutant A156VL49T displayed 8.3% and 17.4% growth reductions compared to A156V and LysE, respectively. Considering this decreased activity for L-Lys extrusion and considerably elevated activity in L-Arg transport, we hypothesized that this mutant would be plausible for engineering a strain with enhanced L-Arg production and simultaneously reduced L-Lys byproduct production. Compared to the enhanced activity of many combinatorial mutants of A156V, most A156Y-derived L49 mutations were detrimental to the efflux activity of many mutants, with identical growth compared to the control strain carrying the empty plasmid (Fig. 7e, f).

a, c Growth of A156VL49X mutants in the 96-well plate containing various concentrations of L-canavanine or b 5 g L−1 L-canavanine or d various concentrations of H-Lys-Ala-OH. e Growth of A156YL49X in the 96-well plate containing various concentrations of L-canavanine or f 5 g L−1 L-canavanine. After being cultured at 37 °C for 24 h, the growth was monitored by measuring the OD600nm values. Data are from n = 3 independent experiments, Error bars represent SEM.

Discussion

Structure-guided rational design is an effective method for generating ideal mutants with altered transport activities and substrate specificities. Owing to the unavailability of the LysE structure and its very low sequence identity with other structurally characterized transporters, a reliable LysE structural model would be valuable for the efficient engineering of target mutants. According to the TCDB database, the LysE transporter is assigned to the LysE superfamily, which comprises transporters from 12 families that primarily function in the transport of small molecules such as divalent ions, amino acids, or sugars2,3. Although the structural data for this superfamily are limited, the solved structures share a 3-TM repeat as the basic building block. In these structures, parallel discontinuous helices are located adjacent to the substrate-binding pocket and are critical for substrate binding and transport18,19. The structural architecture of LysE agrees well with these structural elements, including parallel discontinuous helices where Motif A and Motif C are located. These motifs spatially correspond to the PCxxP motif in the CcdA structure13, and mutations in some conserved residues of these motifs have shown to be detrimental to the transport activity of LysE.

In the structure of some transporters, discontinuous helices generally appear in the active pocket, but with different folding patterns, such as the classified X-type (NhaA fold)26,27, hairpin-type28,29,30, and parallel-type (LeuT fold)13,14 discontinuous helices discussed in this study. Notably, these discontinuous helices generally form an active pocket for substrate binding and are considered as key targets for engineering modifications15,16,31,32 because of the presence of hotspot residues in these unwound regions16. The parallel discontinuous helices identified in the LysE structure are conserved structural features of the LeuT-fold pattern found in many APC transporters33. Since LeuT fold transporters contain 12 TMs, in contrast to LysE, we further explored the consistency of conserved motifs and substrate-binding sites between these two types of transporters. Interestingly, the orientation of their amino acid substrates and the locations of their binding sites showed high similarity between the LysE and LeuT-fold transporters, particularly in the unwound region of the active pocket. Corresponding to the signature GXG motif recognized in LeuT homologs for substrate binding17, we identified a highly conserved Gly19 at an equivalent position in LysE transporters. Based on these structural similarities, we propose that the 6-TM LysE transporter operates in a similar, albeit simplified, LeuT-fold mode to that of 12-TM LeuT transporters.

In addition to the above-mentioned sites for substrate binding, two Na+ ions are generally solved in the core structure of Na+-coupled LeuT fold transporters and play important roles in stabilizing the architecture of the substrate-binding site14. In contrast, H+-coupled symporters such as NhaA, LacY, and FucP generally assemble negatively charged residues Asp and Glu in their transport path34,35,36. Protonation of these conserved residues lowers the energy barrier for substrate entry into the binding site and facilitates substrate translocation34,37. Notably, we also found two highly conserved acidic residues (Asp46 in TM2 and Asp159 in TM4) located in the substrate pocket of LysE; mutation of these two residues to Ala completely abolished transport activity, implying that the proton-driven transport of LysE complies with the protonation mechanism of H+-coupled transport processes.

With the aid of the identified critical fold pattern of LysE, molecular docking, and the Calculated Mutation Energy (Stability) module of Discovery Studio identified two sites, Leu49 and Ala156, that potentially influence LysE/L-Arg stability and transport activity. Both of these sites are located within the motifs recognized in LysE homologs, providing strong evidence for the critical functions of these motifs in substrate binding and transport13,16. Moreover, these sites exhibited different conservation levels among the LysE homologs. Leu49 in Motif B was highly conserved, whereas Ala156 in Motif C was typically occupied by either Ala or Val. Compared to Leu49, Ala156 was more flexible and performed better among the mutations constructed in this study, indicating that unconserved sites in the active pocket may serve as hotspot residues for protein engineering38. Among the several improved mutants, the double mutant A156VL49T was the most ideal, with increased L-Arg efflux activity and reduced L-Lys efflux activity. We further compared the stability of these protein-substrate complexes and found that mutants A156Y and A156VL49T exhibited much more stable RSMD curves than LysE (Supplementary Fig. S5a, b, d). Notably, the large fluctuations at 25 ns disappeared completely in the A156Y and A156VL49T curves. As for mutant A156V, the RMSD curve between 7.5–20 ns was more stable, but a variation around 2 Å was observed from 20 to 30 ns (Supplementary Fig. S5c). In agreement with the RMSD curves, the RMSF analysis also showed that these mutants had relatively lower RMSD values in the 100–140 region (Supplementary Fig. S6). These differences are consistent with the observed improved complementary growth of A156V as well as the more robust growth of A156Y and A156VL49T. Together, we hypothesized that these two mutations may conformationally alter the substrate pocket or conformational state of LysE, resulting in a more stable complex for L-Arg binding and consequently increasing the efflux activity of these mutants.

Methods

Strains and plasmids

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. All E. coli strains were cultured in LB medium containing 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, 10 g NaCl per liter, or LB agar at 37 °C. MA medium which comprises of 7.0 g K2HPO4, 3.0 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g sodium citrate dihydrate, 0.1 g MgSO4·7H2O, and 1.0 g (NH4)2SO4 per liter, was used for the complementary growth assay, with 2.0 g L−1 glucose supplementation before use.

Bioinformatics and structural modeling

The amino acid sequence of LysE was submitted to the UNIPROT database, and 300 amino acid sequences with 35–95% identity were selected for sequence analysis. The ConSurf server was used for evolutionary conservation analysis and WebLogo was used for motif analysis. The transmembrane structure of LysE was predicted using TMHMM, Tmpred, HMMTOP, and SOSUI software. Aphafold2 was used for the three-dimensional structure prediction. The structural model was visualized using PyMol software (http://www.pymol.org/).

Molecular docking and MD simulations

Using the three-dimensional structural model of LysE as the receptor protein and L-Arg or l-Lys as the small molecule ligands, molecular docking was performed using the CDOCKER module in Discovery Studio 4.1 with default parameters. The docking proteins and ligands were imported into Discovery Studio and the proteins were assigned to the CHARMM force field. The conformation with the lowest binding free energy was selected as the final molecular docking structure.

MD simulations were conducted in the Desmond module of Schrodinger 2019 software using the OPLS2005 force field and a predefined SPC model for water. To neutralize the system charge, an appropriate amount of Cl−/Na+ ions was added to balance the system charge and randomly placed in the solvated system. After constructing the solvated system, energy minimization was performed using the default protocol integrated within the Desmond module with OPLS2005 force-field parameters. The temperature and pressure were maintained at 300 K and 1 atm, respectively, using Nose-Hoover temperature coupling and isotropic scaling. Then, a 30/50 ns NPT simulation was executed, and the trajectory data were saved at 50 ps intervals. To predict the binding pocket for L-Arg accommodation, the whole LysE protein and Arg ligand were submitted to CavityPlus (http://pkumdl.cn:8000/cavityplus), and the complete pocket with the highest predicted average pKd value was selected. All results were imported into PyMOL to compare the active pocket with that predicted by molecular docking.

Construction of Arg- and Lys-transport deficient E. coli strains

For the construction of argO and lysO deficient strains in E. coli MG1655, the genome of E. coli MG1655 was retrieved from the NCBI database. For gene knockout, the kan gene with homologous arms and FRT sites was amplified from plasmid pKD4, using primers listed in Supplementary Table S2. The gene fragment was transformed into MG1655-pTKRed competent cells by electro-transformation and plasmid pCP20 was further transferred into it to eliminate the kan gene. The p-lysE fragment was amplified from the genome of C. glutamicum ATCC13032 and transformed into the defective strain E. coli MG1655ΔargO or E. coli MG1655ΔlysO, resulting in two recombinant strains E. coli MG1655ΔargO-pEASY-P-LysE and E. coli MG1655ΔlysO-pEASY-P-LysE. In the meanwhile, the empty plasmid was also transferred into the defective strains and served as the negative control (E. coli MG1655ΔargO-pEASY or E. coli MG1655ΔlysO-pEASY).

Mutant prediction and construction

Discovery Studio 4.1 was used to perform the saturation mutagenesis simulation. After applying the CHARMm force field to the protein, all amino acid sites within the 0.4 nm of the ligand were selected for analysis. Alanine scanning and virtual site saturation were performed using the single-point mutation mode in the calculated mutation energy (stability) module. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed via overlapping-extension PCR based on the plasmid P-LysE and the primers listed in Supplementary Table S2. The resulting mutated plasmids were transformed into transporter-deficient strains of E. coli MG1655ΔargO-pEASY or E. coli MG1655ΔlysO-pEASY.

Complementary growth assay

To evaluate the transport function of LysE mutants, recombinant strains were initially cultured in MA medium supplemented with 1 g L−1 of L-Arg and 100 μg mL−1 of kanamycin. After 24-h cultivation at 37 °C and 200 rpm, the cell culture was diluted to a concentration of 5 × 105 CFU mL−1 by fresh MA medium. The diluted cultures were then transferred to either 96-well plates or 300-mL flasks containing MA and various concentrations of L-canavanine22 or H-Ala-Lys-OH39. After 24-h cultivation at 37 °C and 200 rpm, the optical density of the culture was measured at 600 nm (OD600nm).

Statistics and reproducibility

All experiments of growth assay were performed in triplicates. Statistical data analysis was performed using Origin 2021 and Microsoft Excel. The statistical values are presented as mean value ± standard error of mean (SEM).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published paper and Supplementary Data. A reporting summary for this article is available as a Supplementary Information file. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are also available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Pérez-García, F. & Wendisch, V. F. Transport and metabolic engineering of the cell factory Corynebacterium glutamicum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 365, 16 (2018).

Wang, S. C. et al. Expansion of the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) to include novel transporters as well as transmembrane-acting enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1862, 13 (2020).

Padan, E., Venturi, M., Gerchman, Y. & Dover, N. Na+/H+ antiporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1505, 144–157 (2001).

Wang, H. D., Xu, J. Z. & Zhang, W. G. Reduction of acetate synthesis, enhanced arginine export, and supply of precursors, cofactors, and energy for improved synthesis of L-arginine by Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 107, 3593–3603 (2023).

Yin, L., Shi, F., Hu, X., Chen, C. & Wang, X. Increasing L-isoleucine production in Corynebacterium glutamicum by overexpressing global regulator Lrp and two-component export system BrnFE. J. Appl. Microbiol. 114, 1369–1377 (2013).

Lubitz, D., Jorge, J. M. P., Pérez-García, F., Taniguchi, H. & Wendisch, V. F. Roles of export genes cgmA and lysE for the production of L-arginine and L-citrulline by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 8465–8474 (2016).

Dong, X. Y., Zhao, Y., Hu, J. Y., Li, Y. & Wang, X. Y. Attenuating L-lysine production by deletion of ddh and lysE and their effect on L-threonine and L-isoleucine production in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 93-94, 70–78 (2016).

Zhao, N., Qian, L., Luo, G. & Zheng, S. Synthetic biology approaches to access renewable carbon source utilization in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 9517–9529 (2018).

Shimizu, K. & Matsuoka, Y. Feedback regulation and coordination of the main metabolism for bacterial growth and metabolic engineering for amino acid fermentation. Biotechnol. Adv. 55, 32 (2022).

Xu, M. J., Rao, Z. M., Yang, J., Dou, W. F. & Xu, Z. H. The effect of a LysE exporter overexpression on L-arginine production in Corynebacterium crenatum. Curr. Microbiol. 67, 271–278 (2013).

Man, Z. W. et al. Systems pathway engineering of Corynebacterium crenatum for improved L-arginine production. Sci. Rep. 6, 10 (2016).

Tsu, B. V. The LysE superfamily of transport proteins involved in cell physiology and pathogenesis. PLoS ONE 16, e0137184 (2015).

Zhou, Y. P. & Bushweller, J. H. Solution structure and elevator mechanism of the membrane electron transporter CcdA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 163–169 (2018).

Yamashita, A., Singh, S. K., Kawate, T., Jin, Y. & Gouaux, E. Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl− -dependent neurotransmitter transporters. Nature 437, 215–223 (2005).

Noskov, S. Y. & Roux, B. Control of ion selectivity in LeuT: two Na+ binding sites with two different mechanisms. J. Mol. Biol. 377, 804–818 (2008).

Loland, C. J. The use of LeuT as a model in elucidating binding sites for substrates and inhibitors in neurotransmitter transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1850, 500–510 (2015).

Ponzoni, L., Zhang, S., Cheng, M. H. & Bahar, I. Shared dynamics of LeuT superfamily members and allosteric differentiation by structural irregularities and multimerization. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 373, 10 (2018).

Cho, S. H. & Beckwith, J. Mutations of the membrane-bound disulfide reductase DsbD that block electron transfer steps from cytoplasm to periplasm in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188, 5066–5076 (2006).

Hiniker, A., Vertommen, D., Bardwell, J. C. A. & Collet, J. F. Evidence for conformational changes within DsbD: possible role for membrane-embedded proline residues. J. Bacteriol. 188, 7317–7320 (2006).

Zhu, Y., Zhou, C., Wang, Y. & Li, C. Transporter engineering for microbial manufacturing. Biotechnol. J. 15, e1900494 (2020).

Pathania, A. & Sardesai, A. A. Distinct paths for basic amino acid export in Escherichia coli: YbjE (LysO) mediates export of L-Lysine. J. Bacteriol. 197, 2036–2047 (2015).

Schwartz, J. H. & Maas, W. K. Analysis of the inhibition of growth produced by canavanine in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 79, 794–799 (1960).

Krishnamurthy, H. & Gouaux, E. X-ray structures of LeuT in substrate-free outward-open and apo inward-open states. Nature 481, 469–474 (2012).

Wei, L. N., Zhu, L. W. & Tang, Y. J. Succinate production positively correlates with the affinity of the global transcription factor Cra for its effector FBP in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Biofuels 9, 264 (2016).

Wagner, S. et al. Consequences of membrane protein overexpression in Escherichia coli. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 6, 1527–1550 (2007).

Mondal, R. et al. Towards molecular understanding of the pH dependence characterizing NhaA of which structural fold is shared by other transporters. J. Mol. Biol. 433, 167156 (2021).

Lv, P. W. et al. Structural basis for the arsenite binding and translocation of Acr3 antiporter with NhaA folding pattern. FASEB J. 36, e22659 (2022).

Mancusso, R., Gregorio, G. G., Liu, Q. & Wang, D. N. Structure and mechanism of a bacterial sodium-dependent dicarboxylate transporter. Nature 491, 622–626 (2012).

Su, C. C. et al. Structure and function of Neisseria gonorrhoeae MtrF illuminates a class of antimetabolite efflux pumps. Cell Rep. 11, 61–70 (2015).

Lv, P. W. et al. The pH sensor and ion binding of NhaD Na+/H+ antiporter from IT superfamily. Mol. Microbiol. 118, 244-257 (2022).

Vergara-Jaque, A., Fenollar-Ferrer, C., Mulligan, C., Mindell, J. A. & Forrest, L. R. Family resemblances: a common fold for some dimeric ion-coupled secondary transporters. J. Gen. Physiol. 146, 423–434 (2015).

Patiño-Ruiz, M., Ganea, C. & Calinescu, O. Prokaryotic Na+/H+ exchangers-transport mechanism and essential residues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 9156 (2022).

Edwards, N. et al. Resculpting the binding pocket of APC superfamily LeuT-fold amino acid transporters. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75, 921–938 (2018).

Dang, S. Y. et al. Structure of a fucose transporter in an outward-open conformation. Nature 467, 734–738 (2010).

Hunte, C. et al. Structure of a Na+/H+ antiporter and insights into mechanism of action and regulation by pH. Nature 435, 1197–1202 (2005).

Guan, L. & Kaback, H. R. Lessons from lactose permease. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 35, 67–91 (2006).

Shi, Y. G. Common folds and transport mechanisms of secondary active transporters. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 42, 51–72 (2013).

Moreira, I. S., Fernandes, P. A. & Ramos, M. J. Hot spots—a review of the protein-protein interface determinant amino-acid residues. Proteins 68, 803–812 (2007).

Vrljic, M., Sahm, H. & Eggeling, L. A new type of transporter with a new type of cellular function: L-lysine export from Corynebacterium glutamicum. Mol. Microbiol. 22, 815–826 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 42077214), the Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province (grant no. 2022CXGC020712), and the Science and Technology Projects of Yangzhou City (grant no. YZ2023043).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C.Z. and L.P.V. conducted experiments and wrote the manuscript. F.L.H., L.Y.X., Z.Y., and P.Y.S. analyzed the data; L.C.F. and Y.C.Y. designed the experiment, Y.C.Y. conceived the project and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Berna Sariyar Akbulut, Ekaitz Errasti-Murugarren, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Tobias Goris.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Lv, P., Feng, L. et al. Structure-based modeling and engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum LysE transporter for efficient extrusion of L-arginine. Commun Biol 8, 543 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07997-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07997-x