Abstract

The most common cyanotoxin microcystin is a cyclic heptapeptide produced by non-ribosomal peptide-polyketide synthetases and tailoring enzymes. The tailoring enzyme McyI, a 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase, converts (3-methyl)malate into (3-methyl)oxaloacetate to produce the non-proteinogenic amino acid (3-methyl)aspartate. The reaction is NAD(P)-dependent but the catalytic mechanism remains unclear. Here we describe the crystal structures of McyI at three states: bound with copurified NAD, cocrystallized with NAD/NADP, and cocrystallized with malate or the substrate analogue citrate. An McyI protomer has unusual three nicotinamide cofactor-binding sites, named the NAD-prebound, NADP specific, and non-specific sites. Biochemical studies confirmed the NADP preference during oxidoreductase reaction. Molecular basis for McyI catalysis was revealed by the structures of McyI-NAD binary complex, McyI-NAD-NADP and McyI-NAD-malate ternary complexes, which demonstrate different opening angles between the substrate-binding domain and the nucleotide-binding domain. These findings indicate that McyI is a unique member of the 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase superfamily and provide detailed structural insights into its catalytic mechanism. In addition, the structural ensemble representing various binding states offers clues for designing enzyme for bioengineering applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cyanobacterial blooms cause serious environmental and ecological problems such as deterioration of water quality and fishery damage1. Cyanopeptides, a diverse group of metabolites, are released during blooms and are often toxic to most eukaryotic organisms2. The cyanotoxin microcystins cause liver injury and are the most intensively characterized cyanopeptides3. Microcystins are cyclic heptapeptides synthesized via a non-ribosomal pathway that employs the modular peptide-polyketide synthetases and additional tailoring enzymes, which are encoded by the microcystin biosynthesis (mcy) gene cluster as annotated in Microcystis aeruginosa4,5. The mcy gene clusters with high sequence differences have been found in a wide range of cyanobacteria6,7,8,9,10,11, consistent with the chemical diversity of the microcystin variants from different strains12.

The primary structure of microcystins is cyclo(-d-Ala-X-d-MeAsp-Z-Adda-d-Glu-Mdha-), with X and Z at positions of 2 and 4 representing any l-amino acids (Fig. 1A). Residues at positions 1, 3, and 5-7 are the non-proteinogenic amino acids d-Ala, 3-methylaspartate (MeAsp), 3-amino-9-methoxy-2,6,8-trimethyl-10-phenyl-4,6-decadienoic acid (Adda), d-Glu, and N-methyldehydroalanine (Mdha), respectively. MeAsp at position 3 is derived from pyruvate and acetyl-CoA by four-step reactions: condensation, isomerization, dehydrogenation, and transamination13,14. The microcystin tailoring enzyme McyI catalyzes the dehydrogenation step (Fig. 1B), where the hydrogen at the 2-hydroxyl of 3-methylmalate is removed to yield 3-methyloxaloacetate (MeOAA). Heterologous expression of the mcy gene cluster of M. aeruginosa in Escherichia coli resulted in the production of two microcystin variants, which differ by the presence or absence of the 3-methyl group, corresponding to MeAsp or d-Asp15. MeAsp and d-Asp are suggested to be heterologously synthesized in E. coli from the initial substrates 3-methylmalate and malate, respectively16. While the enzymatic reactions for MeAsp/d-Asp synthesis await further elucidation, it becomes clear that McyI functions as a 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase (2HADH) to produce MeOAA or oxaloacetate (OAA) in the microcystin biosynthetic pathway17.

A The MeAsp moiety within microcystin. B Interconversion of 3-methylmalate and MeOAA by removing/adding a hydrogen to the 2-hydroxyl/2-oxo group. C Phylogenetic tree of the 2HADH family members. The prefix abbreviations are: Hs, Homo sapiens, Mt Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Ph Pyrococcus horikoshii, As Anabaena sp. 90, Ns Nostoc sp. 152, Cb Candida boidinii, Sa Staphylococcus aureus, Hm Hyphomicrobium methylovorum, Pf Pyrococcus furiosus, Tt Thermus thermophiles, Aa Aquifex aeolicus, Tp Treponema pallidum, Ld Lactobacillus delbrueckii.

The 2HADH family members share two conserved domains: the substrate-binding (SB) domain with a flavodoxin-like fold and the nucleotide-binding (NB) domain with a Rossmann fold18. The known structures of 2HADH family include d-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PGDH)19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26, d-lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)27,28,29, d-glycerate dehydrogenase (GDH)30,31, formate dehydrogenase (FDH)32,33,34, and glyoxylate reductase/hydroxypyruvate reductase (GRHPR)35,36. Phylogenetic analysis of the 2HADH family shows that McyI is more closely related to PGDH (Fig. 1C), an enzyme catalyzing the first step in the serine biosynthetic pathway and having been extensively studied37. Structural characterization of these members has shown that the active site is located in the interdomain cleft. However, despite similarities in the overall structure, the conformation of the active site varies depending on the substrate difference and composition of catalytic residues.

McyI is likely to have evolved functions specific to hepatotoxin biosynthesis and diverged early in the evolution of PGDHs, and the hepatotoxin-associated proteins form a phylogenetically distinct subgroup in the 2HADH family (Fig. 1C). In addition, McyI lacks PGDH activity, suggesting that it is distant from PGDH and belongs to a separate clade of enzymes that uniquely present in the hepatotoxic cyanobacteria14. The conserved Gly-X-Gly-XX-Gly motif in McyI indicates the canonical nucleotide-binding site of McyI is more inclined to bind NAD rather than NADP (Fig. S1). However, the catalysis rates with NAD(H) were significantly lower than with NADP(H)14. Therefore, indeterminate function for McyI in hepatotoxin production needed to be explored.

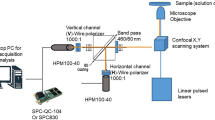

In this study, we investigated the structure and catalytic mechanism of McyI from one of the most common bloom-forming cyanobacteria, Anabaena sp. 909,10. We resolved a series of crystal structures of McyI (of the wild type and site-directed mutants) in binary or ternary complexes with the nicotinamide cofactors and malate/citrate, and identified three nucleotide-binding sites: one for NAD, one for NADP, and one without preference. The NADP-specific binding site is located in SB domain and overlapped with substrate binding site. Three different conformations were revealed: “opened”, “semi-closed”, and “closed” with respect to the inter-domain cleft. The active site and catalytic mechanism are addressed based on structural analyses.

Results

Structure of McyI with prebound NAD

The recombinant McyI (UniProt Q7WRR2) was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified by affinity column and then size exclusion chromatography (SEC). The SEC elution profile showed a single peak that corresponds to a dimer and the peak fraction was collected and crystallized (Fig. S2). The crystal diffracted to 2.8 Å and the structure was solved by molecular replacement (Table 1). As expected, the McyI dimer (chains A and B) binds two NAD cofactors (Fig. 2A). The electron densities in both chains are continuous except the N-terminal 16 residues and C-terminal three residues, which all belong to the SB domain. In the primary structure, the NB domain (residues 112-303) interrupts the SB domain (residues 1-111 and 304-337). The SB domain consists of five α-helices (αA-αD and αL) and a five-stranded β-sheet (β2-β1-β3-β4-β5), and the NB domain consists of seven α-helices (αE-αK), two η-helices (η1 and η2), and a seven-stranded β-sheet (β3-β2-β1-β4-β5-β6-β7) (Fig. S3). Dimerization interactions are primarily between the NB domains (Fig. 2B). A hydrophobic core is formed within the bundle constituted by αE and αG from both protomers. Residues constituting the core include Leu121, Leu125, Ile174, and Leu179. Inter-protomer hydrogen bonds and salt bridges occur among the side chains of Glu118–Lys129, Gln153–Thr302, and Lys157–Glu304, and include side chain–backbone hydrogen bonds of Glu118–L154, Glu118–Glu155, Asn135–Phe294, Lys139–Tyr287, Lys139–Phe289, Arg146–Pro296, Arg146–His297, and Tyr287–Val138. These interactions have a 2-fold pseudo-symmetry except the hydrogen bonds to Tyr287, for which only the chain A-to-chain B bonds were observed.

A Domain arrangement. Domain scheme is shown on top, and the bar width is scaled to match the domain length. Protein is in ribbon representation and cofactor is shown as sticks. The SB and NB domains of chain A are in sky blue and magenta, respectively; chain B is in gray. For the cofactor atoms, carbon is in yellow, nitrogen is in blue, oxygen is in red, and phosphorus is in orange. B Dimerization interface. The side chains of Glu118, Leu121, Leu125, Lys129, Lys139, Asn135, Arg146, Gln153, Lys157, Ile174, Leu179, Tyr287, Thr302, and Glu304, and the backbones of Val138, L154, Glu155, Tyr287, Phe289, Phe294, Pro296, and His297 are shown as sticks. Inter-protomer hydrogen bonds and salt bridges are shown as black dashed lines. Colored shades correspond to the regions shown in insets (right panel), where ribbons are in transparency.

The cofactor NAD is situated at the canonical NAD-binding site on the NB domain (Fig. 3A and Fig. S4). The characteristic Gly-X-Gly-XX-Gly motif and a conserved bridging water molecule are well defined (Fig. 3B). The C4 atom of the nicotinamide points towards the SB domain, suggesting that the structure represents an open state of the enzyme. As it was reported that the NAD/NADP ratio in cyanobacteria ranges from 0.27 to 0.1538 and McyI prefers NADP14, we inspected the structural basis for cofactor specificity, which can be attributed to the 2’-position of the adenine ribose. Typically, negatively charged residues nearby the position repulse the 2’-phosphate of NADP and form hydrogen bonds with 2’-OH of NAD, while positively charged residues prefer NADP by forming electrostatic interaction with 2’-phosphate39. In the structure of McyI in complex with prebound NAD, Asp187 forms hydrogen bonds to the 2’- and 3’-OH of the adenine ribose. This aspartate is conserved in McyI (Figure S1) as well as in PGDH and LDH that are known to use NAD for catalysis18, but variations exist in GDH, FDH and GRHPR, which prefer NADP or have dual cofactor specificity. The structure supports that the canonical nucleotide-binding site of McyI selectively binds NAD rather than NADP.

A Chain A in ribbon and surface representations. The color scheme is same as in Fig. 2. B The interaction of prebound NAD with McyI. The side chains of Arg166, Asp187, Glu225, and Asp273, and the backbones of Gly163, Gly165-Gly168, His219-Glu221, Thr247, and Gly300 are shown as sticks. The structurally conserved water is shown as a red sphere. Hydrogen bonds and salt bridges are shown as black dashed lines. Ribbons are in transparency.

NADP serves as the cofactor for recombinant McyI

Because the prebound NAD could not be removed by dialysis or ultrafiltration, all experiments were done in its presence with its absorbance at 340 nm being subtracted as background. The oxidoreductase activity assays confirmed that NADP, instead of NAD, serves as the cofactor for recombinant McyI (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Data 1). These data were fitted to the Michaelis–Menten equation, and the calculated KM value is 56 μM and the Vmax is 42 μmol·min−1 (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Data 2). In addition, we measured NADPH binding by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), and the apparent Kd value between McyI and NADPH is 16.0 μM (Fig. 4C). The stoichiometry (1: 1.75) should indicate an approximate 1: 2 molar ratio between McyI and NADPH (Fig. 4C and Figure S5). The non-integer stoichiometry may arise from dynamic behavior for NADPH binding or the concentration setup. We next tested whether NADP competes with NAD to bind McyI. We soaked the crystals in solution containing NADPH, collected the 2.2-Å diffraction data, and solved the structure of McyI in complex with NADPH (8WPI). The dimeric structure has three NADP and two prebound NAD molecules (Fig. 5A). Among the three NADPH molecules, two are bound to the second nucleotide-binding site in the NB domain. The nicotinamide moiety inserts into a small pocket and is stabilized by hydrogen bonds between Ala126 and Thr132 (Fig. 5B). The adenine-ribose-phosphate moiety of the NADPH at the site is missing in the electron density map (Figure S6A). The Cα atoms of the NADP-bound McyI have a root-mean-square deviation of less than 0.28 Å with those of McyI bound with NAD, indicating only slight conformational difference of the protein structure (Fig. 5C). The third NADPH molecule is unexpected. It is adjacent to the canonical NAD-binding site clamped by the NB and SB domains (Fig. 5D).

A Reductase activity assay. The enzyme, OAA, and the nicotinamide cofactor (filled square, NADP; open square, NAD) were at 1.6 μM, 1 mM, and 0.2 mM, respectively. Each error bar indicates the standard deviations of three replications. B Reaction velocity vs. [NADPH]. OAA was supplied at 1 mM, and NADPH was set at concentrations of 0 to 300 μM, and the interval was 25 μM. The fitted curve yielded Vmax of 42 μmol·min-1 and KM of 56 μM. Each error bar indicates the standard deviations of three replications. C ITC analysis of NADPH binding. Titration of McyI with NADPH: 19 injections of 2 μL substrate (1.5 mM NADPH) were added to 300 μL protein (110 μM).

A The McyI-NAD-NADP ternary structure (PDB 8WPI). Carbons of NADP are in green. B NADP bound to the second nucleotide-binding site. Only the nicotinamide-ribose-pyrophosphate moiety was observed (left panel). Superimposition with the NAD-bound structure (with PDB 8WPJ) was shown in the right panel. C Superimposition of the three McyI structures. The backbones are shown as tubes. Color scheme for PDB entries: yellow, 8WPH; cyan, 8WPJ; green, 8WPI. D Chain A of the NADP-bound McyI structure in surface and ribbon representations. Compared with Fig. 6A (upper panel), the structure is reoriented 150° along x-axis to show the interdomain NADP. E The interaction between the interdomain NADP and McyI. The side chains of Tyr26, Thr85, Ser86, and Arg249, and the backbones of Gly87-Gly89, Gly300, and Thr302 are shown as sticks. The water molecule is shown as a red sphere.

The NADP specific site

The interdomain NADP-binding site has conserved features of a canonical nucleotide-binding site (Fig. 5E). The loop (Thr85-Gly89) following β4 contains a Gly-X-Gly consensus, binds a water molecule, and interacts with the pyrophosphate moiety both directly and via the bridging water. Tyr26 also participates in pyrophosphate binding via its side-chain hydroxyl group. The nicotinamide-ribose-pyrophosphate moiety of the bound NADP has double conformations (Figure S6B, C). The amide group of the nicotinamide forms hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of either Gly300 or Thr302. The adenine-ribose-phosphate moiety is stabilized by Arg249, whose guanidino group essentially fixes the 2’-phosphate. This arginine should act as the selectivity determinant for NADP over NAD. Although such an arginine is conserved in the 2HADH family, the aforementioned tyrosine and the Gly-X-Gly consensus-containing loop are only found in McyI sequences (Figure S1). Thus, the NADP-binding site should be unique for McyI.

To test the specificity of the NADP-binding site, we soaked the McyI crystals in the crystallization solution with excess amount of NADH before data collection. The crystals diffracted to 2.8 Å resolution (8WPJ). The solved structure shows only two more NAD molecules were found in the second nucleotide-binding site of NB domain besides the two prebound ones (Fig. 6A and Figure S6D). The nicotinamide-ribose moiety of the NAD can be overlaid well with its NADP counterpart (Fig. 5B), suggesting a conserved mode for nicotinamide binding. The rest atoms of NAD are outside of the pocket, and the 2’-OH of adenine ribose interacts with the side-chain amide of Gln148 (Fig.6B). No significant conformational difference was observed for the McyI protein.

A Overall structure. The color scheme is same as in Fig. 2 except that the carbons of soaked NAD are in cyan. B The non-canonical NAD-binding site in ribbon and surface representations. The overall structure is reoriented (90° along y-axis and then 20° along x-axis) to show the binding site. Insets show the zoomed-in views of the site. The side chains of Thr132 and Gln148 and the backbone of Ala126 are shown as sticks. Inter-molecular hydrogen bonds and salt bridges are shown as black dashed lines.

The active site and catalytic mechanism

To test the roles of NAD and NADP in McyI catalytic activity, we generated site-directed mutations including: R166M, R166A, D273A, D187A, R166A/D187A, and R166A/D187A/D273A mutants associated with NAD binding, R249M, R249A, Y26F, S86A mutants associated with NADP specific binding, and T132A mutant associated with the non-specific binding site. We obtained soluble mutant proteins except D187A, R166A/D187A, R166A/D187A/D273A (all in the NAD binding site). Compared with the wild-type McyI, the Y26F mutant showed a small decrease of the reductase activity as reflected by the changes of absorbance at 340 nm; S86A, R249A, R249M and D273A mutants almost lost activity; R166M and R166A shows about 50% decrease of catalysis activity (Fig. 7A and Supplementary Data 3). We further determined the kinetics of Y26F, R166M and R166A, and found that Y26F has similar KM and Vmax, but the KM values of R166M and R166A increase obviously (Table 2, Figure S7 and Supplementary Data 4). These results confirmed that both NAD and NADP are necessary to maintain the enzyme structure and activity.

A Reductase activity assay. The setup was as described for Fig. 4A and the reaction time was 20 min. Each error bar indicates the standard deviations of five replications. B The R166A-NAD-malate ternary structure. Carbons of NAD and malate are in yellow and violet purple, respectively. C The interaction between the malate and McyI. The side chains of His297, and the backbones of Ser86-Phe88, and His297 are shown as sticks. D Superimposition of R166A-NAD-malate ternary structure (blue and hotpink) and chain-A of McyI-NAD (gray).

To explore the role of Arg166 in NAD binding and reductase activity, we resolved the crystal structures of the R166M and R166A mutants. Both crystallization conditions contain citrate, which binds in the substrate binding site of McyI (Figure S8A). Then we cocrystallized OAA, d-malate and NADP with R166M and R166A mutants, respectively. We only obtained the crystal structures of R166M/A-malate complex, and malate was fitted in the substrate binding site instead of citrate (Fig. 7B). The backbone of Ser86-Phe88 and side chains of Ser86 and His297 form hydrogen bonds with malate (Fig. 7C). Malate overlapped with the NADP-specific binding site, and two residues (Ser86 and His297) participate in both substrate and NADP binding. It could be the reason that we could not obtain the crystal structure of McyI-NAD-NADP-substrate. These four structures (R166M/A-NAD-malate/citrate) show only slight conformational difference (Figure S8B). However, when compared with the substrate-free structure (McyI-NAD), the conformations of R166M/A-NAD-malate/citrate change with respect to the position of the catalytic domain (Fig. 7D).

To allocate the reported structures to certain state, we superposed the protomers of McyI-NAD, McyI-NAD-NADP and R166A-NAD-malate. Chain-B of McyI-NAD-NADP shows a most open conformation, which cannot bind NADP; NADP-bound chain-A is in semi-closed conformation; R166A-NAD-malate is in the closest state (Fig. 8A). Arg166 could be the key residue determining the different conformations, as the conformation change of side chain guanidyl causes the transformation from “opened” to “semi-closed”, and deletion of the side chain (R166A) results in greater mobility and instability. This may be the reason for the decreased activity of R166A/M. Based on these results, we suggest an McyI working model (Fig. 8B). NAD is permanently bound in the active site and is recharged by NADP for catalysis. At the opened state, the prebound NAD-McyI is inactive; at the semi-closed state, the NAD-NADP-McyI ternary complex forms when NADPH levels are high in the environment and facilitates charging to McyI; then, NADP+ releases and substrates enter, and the active site closes tightly. During the whole reaction process, the highly conserved Arg249 transpositionally binds substrate and NADP (Figure S1). His297 acts as the catalytic acid/base in McyI and this is consistent with d-lactate dehydrogenase27.

A Superimposition of chain-B of McyI-NAD (limon), chain-A of McyI-NAD-NADP (deepteal) and R166A-NAD-malate (blue). The interactions between Arg166 and SB domain are labeled in black dash and the relevant residues are shown in sticks, including the side chain of Tyr328 and the backbones of Pro109-Gly110. B The supposed catalytic process of the oxidation-reduction reactions. Chain-B of McyI-NAD is in an open conformation; when NADP enters, the McyI-NAD-NADP ternary complex is in a “semi-closed” state, and NADP charges NAD+; when NADP+ releases with OAA entering, OAA is reduced to malate, and R166A-NAD-malate is in a closed state.

Discussion

Our structural data have shown that the McyI protomer has three nicotinamide cofactor-binding sites. The canonical nucleotide-binding site in the NB domain is occupied by a tightly bound NAD. The second nucleotide-binding site in the NB domain is distant from the canonical site and does not discriminate between NADP and NAD. NAD(P) in the second site might play a regulatory role for catalysis or be a stored cofactor. The third nucleotide-binding site is formed by both NB and SB domain, with the latter contributing the majority of the interacting residues. It is also possible that crystal packing facilitates the binding to the non-canonical site. Only chain A binds an NADP molecule, suggesting an asymmetric reduction of the cofactor during catalysis (Fig. 7B). We observed that NAD does not compete with NADP for McyI activity, and a standard Michaelis-Menten model was used to fit the v vs. [NADP] curve (Fig. 4B). However, multiple cofactor-binding sites complicate the calculation of its parameters, and thus the simplified model can only reflect the kinetic characters qualitatively. Like EcPDGH23, recombinant McyI was purified with the prebound NAD, whose molecular basis has been decribed in this study. While NAD appears to play a structural rather than catalytic role, it should be noted that the enzyme was heterologously expressed. Whether such scenario exists in Anabaena sp. 90 requires in vivo studies. Nevertheless, this might be true for the engineered E. coli strains designed for microcystin synthesis16.

The distance between the two C4 atoms of NAD and NADP is 7.9 Å based on the crystal structures, which is not sufficient for direct hydride transfer from NADPH to NAD+ as the dominant distance for hydride transfer is about 3 Å40. Certain conformation rearrangement should bring them close enough to allow hydride transfer. A similar hydrogen transfer event between NAD and NADP occurs in the transhydrogenase41,42. Double conformation of the nicotinamide mononucleotide moiety in NADPH observed in McyI probably supports this hypothesis.

As with most of the 2HADH family members, McyI has a promiscuous catalytic activity. In addition to the oxidation-reduction between OAA and malate, McyI is also able to catalyze the reduction of ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate14. The higher catalytic efficiency of OAA is consistent with the hypothesis that the native substrate of McyI, 3-methyl oxalacetate (3-MeOAA), is a structural analog of OAA. McyI has been identified only from strains that are capable of producing [D-MeAsp] microcystin, so it may be specific to these strains but not critical for all types of microcystin producing strains. However, we could not obtain the native substrate 3-MeOAA to test the effect of methylation. The substrate binding pocket is approximate 10×6×4 Å3 in the inter-domain cleft, which should be sufficient to accommodate the methylated substrates (Figure S8C).

The evolutionary status of McyI and its structures reported here indicate that McyI is singled out in the 2HADH family. The 2HADH family members have provided versatile building blocks for the synthesis of a variety of significant chiral compounds ranging from antimicrobial compounds, antitumour antibiotics, biodegradable polymers, to angiotensin-converting inhibitors. The previously unreported regulatory mechanism of McyI reported here offers a scaffold for designing the nicotinamide cofactor-binding site. The stereospecific redox reaction endorsed by the nicotinamide cofactor can allow engineering the biocatalysist for certain non-natural amines.

McyI belongs to the tailoring enzymes associated with the peptide-polyketide synthetase system. It participates in the synthesis of non-proteinogenic amino acids, and therefore is a candidate for bioengineering applications. In this work, we have presented the structural and biochemical data of McyI, demonstrated that NADP acts as the efficient nicotinamide cofactor, and mapped the active site. These findings identify McyI as a unique member of the PGDH superfamily and provides new insights into the function of a classic NAD(P)-dependent oxidoreductase.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

The full-length mcyI gene from Anabaena sp. 9043 was codon-optimized for expression in Escherichia coli, synthesized, and cloned into the pUC57 vector by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). The gene was PCR-amplified and inserted between the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites of the expression vector pET-28a(+) (Novagen). The site-directed mutation of McyI was made using PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (TaKaRa) with pET-28a(+)-mcyI as template. All plasmids were sequenced to verify their identity.

Protein expression and purification

The pET-28a(+)-mcyI plasmid, encoding the 337-residue McyI protein with additional 20 residues at the N-terminus (MGSSHHHHHHSSGLVPRGSH), was transformed into BL21(DE3) cells for expression. Cells were grown at 37 °C in lysogeny broth medium containing 50 μg·mL-1 kanamycin, and 0.2 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside was added for induction when the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.8. The cells were grown for 16 hours at 16 °C before harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellets were resuspended in buffer A (150 mM NaCl and 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) plus 20 mM imidazole, and then the cells were lysed by sonication in an ice bath. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 1 hour at 4 °C. The supernatant was incubated with buffer A-equilibrated nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose resin (QIAGEN) for 1 hour at 4 °C, packed, washed, and then eluted with 200 mM imidazole. The elute was further concentrated by ultrafiltration and applied onto buffer A-equilibrated HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) for size exclusion chromatography. Peak fractions were collected and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Fractions containing purified McyI were pooled, concentrated by ultrafiltration, and stored at −80 °C. The procedure for purification of the mutated proteins was the same as that of the wild type.

Oxidoreductase activity assay

For kinetic analysis of McyI, the procedure described by Pearson et al14. was followed with modifications. The assay was performed in the direction of NADP oxidation. Briefly, NADP at set concentrations of 0 to 300 μM and substrate OAA at 1 mM were added in 1 mL buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 200 mM NaCl at 25 °C. The reaction was started by adding 2 μL of 30 mg·mL-1 McyI, equal to final molar concentration of 1.6 μM, and the absorbance at 340 nm was recorded using a spectrophotometer (UV-1500, Shanghai Macy Instrument). NADP oxidation was monitored by the decrease in 340-nm absorbance. Vmax and the Michaelis constant KM were obtained from the fitted curve of the Michaelis-Menten equation using Origin software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA).

Isothermal titration calorimetry

ITC experiments were performed on a MicroCal PEAQ-ITC calorimeter at 20°C. The buffer was 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol. The ITC experiment comprised 19 injections of 2 μL substrate (1.5 mM NADPH) into 110 μM McyI and with a 120 s interval between injections. Control experiments were carried out by injecting each NADPH into the buffer, and the resulting heat of dilution was subtracted from the binding-isotherm data. The first injection was ignored in the final analysis. The raw data were processed using the Origin software (OriginLab, Northampton, Massachusetts, USA) and were fitted to a one-site binding model.

Crystallization

Protein concentration was 20 mg·mL-1 for crystallization. Initial trials were performed using commercial crystallization kits from Hampton Research and QIAGEN. The sitting-drop vapor-diffusion experiments were set up at 4 °C and 16 °C using 1 μL protein plus 1 μL reservoir. After 4 days, crystals were found at 16 °C in 0.2 M trimethylamine N-oxide, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, and 20% (w/v) PEG 2000 MME. The crystals were transferred stepwise into reservoirs containing 5%, 10%, and 15% (v/v) glycerol for cryo-protection, and then flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen for data collection. To characterize the potential nicotinamide cofactor-binding site, the McyI crystals were soaked in the reservoirs containing 15 mM NAD or NADP and 15% (v/v) glycerol for 5 hours before cooled in liquid nitrogen. The crystals of the two R166 mutants (R166A and R166M) were found in the reservoir solution containing 0.2 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M trisodium citrate, pH 5.6, and 15% (w/v) PEG 4000. The malate-bound R166A and R166M complexes were crystallized in the reservoir solution containing 0.2 M diammonium tartrate and 20% (w/v) PEG 3350 with a 50-fold molar excess of malate.

Diffraction and structural determination

X-ray diffraction data were collected on the BL19U1 beamline of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility at wavelength of 0.979 Å44. The data were processed and scaled using the HKL-3000 package45. The structure of McyI was determined by molecular replacement using Phaser46 from the CCP4 suite47. The structure of P. horikoshii PGDH (PDB ID 1WWK) was used as search model. Manual corrections and refinements were carried out using Coot48 and phenix.refine49. The structures of McyI in complex with soaked NAD or NADP were determined using the solved McyI structure as template. The quality of the final model was evaluated by MolProbity50. All structure figures were prepared with PyMOL51.

Statistics and reproducibility

Sample numbers, reproducibility for the experiments, and the type of error bars are indicated in the figure legends. Biochemical, spectroscopy, and chromatography data were collected at least three times for each protein variant, and the most typical results were presented (no significant outliers were observed in any case).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Protein model coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with the following accession codes: McyI with prebound NAD (8WPH), McyI with soaked NAD (8WPJ), McyI with soaked NADP (8WPI), R166M with citrate (8WPQ), R166A with citrate (8WPO), R166M with malate (8WPS) and R166A with malate (8WPR). The other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files.

References

Huisman, J. et al. Cyanobacterial blooms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 471–483 (2018).

Dittmann, E., Fewer, D. P. & Neilan, B. A. Cyanobacterial toxins: biosynthetic routes and evolutionary roots. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 23–43 (2013).

Svirčev, Z. et al. Toxicology of microcystins with reference to cases of human intoxications and epidemiological investigations of exposures to cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins. Arch. Toxicol. 91, 621–650 (2017).

Tillett, D. et al. Structural organization of microcystin biosynthesis in Microcystis aeruginosa PCC7806: an integrated peptide-polyketide synthetase system. Chem. Biol. 7, 753–764 (2000).

Nishizawa, T. et al. Polyketide synthase gene coupled to the peptide synthetase module involved in the biosynthesis of the cyclic heptapeptide microcystin. J. Biochem. 127, 779–789 (2000).

Dittmann, E., Neilan, B. A. & Börner, T. Molecular biology of peptide and polyketide biosynthesis in cyanobacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 57, 467–473 (2001).

Kaebernick, M., Dittmann, E., Börner, T. & Neilan, B. A. Multiple alternate transcripts direct the biosynthesis of microcystin, a cyanobacterial nonribosomal peptide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 449–455 (2002).

Christiansen, G., Fastner, J., Erhard, M., Börner, T. & Dittmann, E. Microcystin biosynthesis in Planktothrix: genes, evolution, and manipulation. J. Bacteriol. 185, 564–572 (2003).

Rantala, A. et al. Phylogenetic evidence for the early evolution of microcystin synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa. 101, 568–573 (2004).

Rouhiainen, L. et al. Genes coding for hepatotoxic heptapeptides (microcystins) in the cyanobacterium Anabaena strain 90. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 686–692 (2004).

Jungblut, A. D. & Neilan, B. A. Molecular identification and evolution of the cyclic peptide hepatotoxins, microcystin and nodularin, synthetase genes in three orders of cyanobacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 185, 107–114 (2006).

Bouaïcha, N. et al. Structural diversity, characterization and toxicology of microcystins. Toxins 11, 714 (2019).

Moore, B. S. Biosynthesis of marine natural products: microorganisms and macroalgae. Nat. Prod. Rep. 16, 653–674 (1999).

Pearson, L. A., Barrow, K. D. & Neilan, B. A. Characterization of the 2-hydroxy-acid dehydrogenase McyI, encoded within the microcystin biosynthesis gene cluster of Microcystis aeruginosa PCC7806. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 4681–4692 (2007).

Liu, T. et al. Directing the heterologous production of specific Cyanobacterial toxin variants. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 2021–2029 (2017).

Liu, T., Mazmouz, R., Pearson, L. A. & Neilan, B. A. Mutagenesis of the microcystin tailoring and transport proteins in a heterologous cyanotoxin expression system. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 1187–1194 (2019).

Cullen, A. et al. Heterologous expression and biochemical characterisation of cyanotoxin biosynthesis pathways. Nat. Prod. Rep. 36, 1117–1136 (2019).

Matelska, D. et al. Classification, substrate specificity and structural features of D-2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenases: 2HADH knowledgebase. BMC Evol. Biol. 18, 199 (2018).

Schuller, D. J., Grant, G. A. & Banaszak, L. J. The allosteric ligand site in the Vmax-type cooperative enzyme phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2, 69–76 (1995).

Bell, J. K., Grant, G. A. & Banaszak, L. J. Multiconformational states in phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 43, 3450–3458 (2004).

Ali, V., Hashimoto, T., Shigeta, Y. & Nozaki, T. Molecular and biochemical characterization of D-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase from Entamoeba histolytica. A unique enteric protozoan parasite that possesses both phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated serine metabolic pathways. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 2670–2681 (2004).

Dey, S., Grant, G. A. & Sacchettini, J. C. Crystal structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase: extreme asymmetry in a tetramer of identical subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14892–14899 (2005).

Burton, R. L., Hanes, J. W. & Grant, G. A. A stopped flow transient kinetic analysis of substrate binding and catalysis in Escherichia coli D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29706–29714 (2008).

Singh, R. K., Raj, I., Pujari, R. & Gourinath, S. Crystal structures and kinetics of Type III 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase reveal catalysis by lysine. FEBS J. 281, 5498–5512 (2014).

Kumar, S. M. et al. Crystal structures of type IIIH NAD-dependent D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase from two thermophiles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 451, 126–130 (2014).

Xu, X. L. & Grant, G. A. Determinants of substrate specificity in D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase. Conversion of the M. tuberculosis enzyme from one that does not use α-ketoglutarate as a substrate to one that does. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 671, 218–224 (2019).

Razeto, A. et al. Domain closure, substrate specificity and catalysis of D-lactate dehydrogenase from Lactobacillus bulgaricus. J. Mol. Biol. 318, 109–119 (2002).

Shinoda, T. et al. Distinct conformation-mediated functions of an active site loop in the catalytic reactions of NAD-dependent D-lactate dehydrogenase and formate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17068–17075 (2005).

Jia, B. et al. Catalytic, computational, and evolutionary analysis of the D-lactate dehydrogenases responsible for D-lactic acid production in lactic acid bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 8371–8381 (2018).

Goldberg, J. D., Yoshida, T. & Brick, P. Crystal structure of a NAD-dependent D-glycerate dehydrogenase at 2.4 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 236, 1123–1140 (1994).

Ali, V., Shigeta, Y. & Nozaki, T. Molecular and structural characterization of NADPH-dependent d-glycerate dehydrogenase from the enteric parasitic protist Entamoeba histolytica. Biochem. J. 375, 729–736 (2003).

Lamzin, V. S., Dauter, Z., Popov, V. O., Harutyunyan, E. H. & Wilson, K. S. High resolution structures of holo and apo formate dehydrogenase. J. Mol. Biol. 236, 759–785 (1994).

Shabalin, I. G. et al. Structures of the apo and holo forms of formate dehydrogenase from the bacterium Moraxella sp. C-1: towards understanding the mechanism of the closure of the interdomain cleft. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 65, 1315–1325 (2009).

Partipilo, M. et al. Biochemical and structural insight into the chemical resistance and cofactor specificity of the formate dehydrogenase from Starkeya novella. FEBS J. 290, 4238–4255 (2023).

Booth, M. P., Conners, R., Rumsby, G. & Brady, R. L. Structural basis of substrate specificity in human glyoxylate reductase/hydroxypyruvate reductase. J. Mol. Biol. 360, 178–189 (2006).

Kutner, J. et al. Structural, biochemical, and evolutionary characterizations of glyoxylate/hydroxypyruvate reductases show their division into two distinct subfamilies. Biochemistry 57, 963–977 (2018).

Grant, G. A. Contrasting catalytic and allosteric mechanisms for phosphoglycerate dehydrogenases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 519, 175–185 (2012).

Tamoi, M., Miyazaki, T., Fukamizo, T. & Shigeoka, S. The Calvin cycle in cyanobacteria is regulated by CP12 via the NAD(H)/NADP(H) ratio under light/dark conditions. Plant J. 42, 504–513 (2005).

Chánique, A. M. & Parra, L. P. Protein engineering for nicotinamide coenzyme specificity in oxidoreductases: attempts and challenges. Front. Microbiol. 9, 194 (2018).

Liang, Z. X. et al. Structural bases of hydrogen tunneling in enzymes: progress and puzzles. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14, 648–655 (2004).

Cotton, N. P. et al. The crystal structure of an asymmetric complex of the two nucleotide binding components of proton-translocating transhydrogenase. Structure 9, 165–176 (2001).

Jackson, J. B. Proton translocation by transhydrogenase. FEBS Lett. 545, 18–24 (2003).

Wang, H. et al. Genome-derived insights into the biology of the hepatotoxic bloom-forming cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain 90. BMC Genomics 13, 613 (2012).

Zhang, W. Z. et al. The protein complex crystallography beamline (BL19U1) at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 170 (2019).

Minor, W., Cymborowski, M., Otwinowski, Z. & Chruszcz, M. HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution–from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 859–866 (2006).

McCoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 (2007).

Winn, M. D. et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 235–242 (2011).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Afonine, P. V. et al. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 68, 352–367 (2012).

Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 (2010).

DeLano, W. L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Schrödinger, LLC. (2002)

Acknowledgements

We thank the beamline scientists at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for technical support during data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L. and X.W. conceived and designed the research. Y.Y., W-L.C., Y-F.D., Y-S.L., J.W. and M.W. performed the experiments. X.W., Y.Y., H-E.D and L.L analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Laura Rodriguez Perez A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Yin, Y., Cheng, WL. et al. Structural insights into the catalytic mechanism of the microcystin tailoring enzyme McyI. Commun Biol 8, 578 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08008-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08008-9