Abstract

Global patterns of intraspecific genetic diversity are key to understanding evolutionary and ecological processes. However, insights into the distribution and drivers of genetic diversity remain limited, particularly for marine species. Here, we explain and predict the genetic diversity of cold and temperate brown macroalgae using genetic data from 29 species and a machine-learning algorithm that incorporates contemporary and past climate conditions during the Last Glacial Maximum (~20,000 years ago) based on the niche centroid hypothesis. We apply this model to the distribution of 280 species and predict their global genetic diversity. Our results show reduced genetic diversity away from the niche centroid, identifying past climate conditions as key drivers of contemporary genetic diversity. Regions with high genetic diversity for multiple species emerge, matching biogeographic patterns of species richness. The mapped diversity hotspots establish timely baselines for brown macroalgae biogeography, evolutionary potential and conservation, contributing to the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intraspecific genetic diversity is a dynamic outcome of long-term evolutionary and demographic processes, often linked to climatic fluctuations1. Consequently, genetic diversity levels are not homogeneous across the geographic distribution of species, often displaying pockets of high diversity surrounded by landscapes of lower and more homogeneous diversity2. One hypothesis seeking to explain the observed genetic patterns is the niche centroid hypothesis, proposing that populations living within their optimal niche conditions tend to exhibit higher abundance and fitness-related attributes, consequently accumulating higher genetic diversity over time3,4,5,6. Under this hypothesis, the niche is defined as a multidimensional hypervolume, whose dimensions are the fundamental variables essential for species’ long-term persistence7. The niche has an internal structure such that its centroid represents theoretically optimal conditions for species survival, progressively decreasing to suboptimal at its periphery, and reaching zero probability of survival outside it7. Under this paradigm, the relative distance from the niche centroid can be linked to fitness-related attributes and genetic diversity levels, with recent studies reporting higher genetic diversity closer to the niche centroid (central populations) compared to less suitable conditions (peripheral populations)4,6,8. However, considering that conditions and species ranges are not stable over time, populations presently regarded as central might have been peripheral in the past, and vice versa. In this context, populations may hold higher genetic diversity today due to their historical exposure to long-term optimal conditions (i.e., climatic refugia), contrary to where bottlenecks and founder effects linked to range expansions might have occurred9,10. Such imprints reflecting past distribution changes are particularly evident in the genetic diversity patterns of low-dispersive cold and temperate species11,12. Integrating for the effects of both historical and contemporary climatic influences into a unified theoretical model could provide an unprecedented understanding of how genetic diversity is distributed across species and regions13,14.

Despite the fundamental role of intraspecific genetic diversity in driving evolutionary potential and climate adaptability15,16, global estimates remain limited17,18, especially for marine species. Existing studies predominantly focus on fish19, while other ecologically critical groups, such as brown macroalgae, remain largely overlooked. These low-dispersive ecosystem-structuring species can form productive marine forests, providing essential habitats and invaluable ecological services to numerous associated species20,21,22. Recognizing their ecological importance, international conventions have long prioritized marine forests as conservation targets (e.g., Barcelona Convention 1975, Convention on Biological Diversity 2010, OSPAR Convention 2021), with a growing emphasis on the conservation of their genetic diversity23. Studies on the genetic diversity of marine forest species remain fragmented, often limited to case-by-case approaches (e.g.,11,24,25) or lacking a biogeographic perspective26, leaving significant gaps in our understanding of their evolutionary and ecological dynamics.

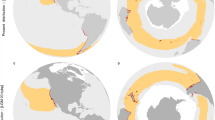

Here, we address this gap by developing a unified model based on the niche centroid hypothesis to explore how marine forest genetic diversity relates to environmental conditions, considering both contemporary and Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, ~20,000 years ago)—a period of extreme climatic cooling that drove extensive distribution shifts, leaving strong imprints on the genetic diversity of cold and temperate marine forest species11,12,27,28. We hypothesize that genetic diversity peaks at the niche centroid, where conditions are optimal, and declines towards the periphery (Fig. 1). To test this hypothesis, we used genetic diversity data of 29 brown macroalgae and a set of six environmental variables under both time periods, identifying the drivers and predicting genetic diversity patterns. We then apply the developed model to the available distribution range maps of 280 marine forest species29 and predict their global biogeographical patterns of genetic diversity. By mapping hotspots of high genetic diversity and revealing long-term climate drivers, we offer insights into the patterns and processes mediating marine forest genetic diversity across all oceans.

A Inferring the environmental niche of a hypothetical species and its centroid from its contemporary distribution. The environmental distance of each sampled population from the niche centroid is calculated. B Species distribution under Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and contemporary conditions, highlighting range shifts over time. We hypothesize that genetic diversity decreases with increasing environmental distance from the niche centroid. The environmental distances of each sampled population from the niche centroid are estimated under both LGM and contemporary conditions.

Results

Genetic diversity data collection

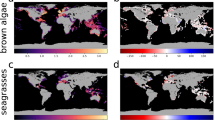

The literature review initially identified 1956 potential studies from which 64 reported genetic diversity estimates for brown macroalgae. Removing duplicate species and regions resulted in a final dataset comprising 40 studies, which collectively covered 29 brown macroalgae species and a total of 669 populations collected at 583 sites (Fig. 2; Supplementary Data 1; Supplementary Data 2). Most species had either cold (6 species) or temperate (22 species) thermal affinities, with genetic data being available only for one tropical species (Fig. 2; Supplementary Data 3). The most reported diversity measures were allelic richness (28 studies, 25 species, 463 populations) and expected heterozygosity (36 studies, 27 species, 534 populations), measured using microsatellites (32 studies), mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA; 2 studies) and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; 7 studies) genetic markers (Supplementary Data 2).

Map depicting the locations of marine forest sampled populations. The species, number of sampled populations, genetic index, genetic marker, number of studies and temperature affiliation inferred from existing species’ distribution range maps are shown. Species were characterized as cold when the 95th percentile of temperature along their range was below 15 °C, temperate when between 15 and 25 °C and tropical above 25 °C. Abbreviations stand for allelic richness (Ar), expected heterozygosity (He), microsatellites (Mic), mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP).

Genetic diversity modelling

A unified machine learning model grounded in niche centroid theory hypothesizing reduced genetic diversity away from the niche centroid (Fig. 1) was developed to predict genetic diversity measured as allelic richness (Ar) and expected heterozygosity (He). The models retrieved high performance both in cross-validation with independent test data and in final predictions (Supplementary Table 1). The final model explained 78% of the deviance with a correlation coefficient of 0.883 for allelic richness and 77.5% of deviance with a correlation coefficient of 0.880 for expected heterozygosity (Fig. 3). Overall, models underpredicted genetic diversity estimates by an average of 8.2% for allelic richness and 22.4% for expected heterozygosity when compared to observed data (Fig. 3). The inclusion of distances from the niche centroid during LGM and contemporary conditions improved the null model (only study, species and genetic marker as predictors), explaining an additional 27.2% of genetic variability for allelic richness and 22% for expected heterozygosity (Supplementary Table 1). Distance to the niche centroid during LGM contributed more than double compared to contemporary conditions (Supplementary Table 2), suggesting that past climate conditions have a stronger impact on observed levels of genetic diversity than contemporary conditions.

Predicting global marine forest genetic diversity

We transferred the developed model to the distribution range maps of 280 cold and temperate marine forest species (Supplementary Data 3) and mapped the potential genetic diversity patterns per species (See Data Availability Statement). Stacking and averaging the individual predictions of genetic diversity provided a global overview of diversity hotspots, with patterns of allelic richness and expected heterozygosity largely overlapping (correlation coefficient 0.953, p-value < 0.001). Hotspots of high genetic diversity for both metrics were found in regions of the north-eastern Pacific, north-eastern Atlantic and the south coast of Australia (Fig. 4). High genetic diversity was also found in regions along the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea, New Zealand, and Japan (Fig. 4). Regions of low genetic diversity were found worldwide, with the largest areas located in the high latitudes of the Arctic, such as along the coasts of Canada and Russia (Fig. 4).

Lastly, genetic diversity had a positive and significant relationship with species richness (correlation coefficient 0.797, p-value < 0.001 for Ar and 0.945 and p-value < 0.001 for He, respectively; Fig. 5). Regions with the highest genetic diversity overlapped with highest species richness worldwide and the opposite (Fig. 5). Notably, there were no regions with high species richness and low genetic diversity (Fig. 5).

A Global estimates of species richness for 280 marine forest species. B Colour scale for the classification of cells based on genetic and species diversity quantile combinations. Global maps depicting quantile combinations of genetic and species diversity and their regression for C, D allelic richness and E, F expected heterozygosity, respectively.

Discussion

By coupling empirical genetic data with a machine learning model to show that the genetic diversity of brown macroalgae marine forests aligns with the niche centroid hypothesis4, we revealed thet present diversity is shaped by past niches. Past climatic conditions (during the Last Glacial Maximum) shaped the present biogeography of genetic diversity of marine forests more than contemporary climate, with regions of past climatic optimum holding higher genetic diversity for multiple species. This global analysis supports case-by-case studies focusing on long-term persistence11,24,30,31,32 and evolutionary theory1,10. The development of a unified predictive model allowed the reconstruction of genetic patterns for multiple species, mapping for the first time the global hotspots of temperate and cold-water marine forest genetic diversity. The predicted biogeographical patterns for allelic richness and expected heterozygosity were consistent and matched the biogeography of species richness33, highlighting how persistence over geological time scales can be a common driver of diversity for genes and species10,34.

The genetic diversity models retrieved high performance when tested against independent datasets through cross-validation, with a final deviance explained of 0.78 and a significant Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.883 for allelic richness and 0.775 and 0.880 for expected heterozygosity, respectively. Despite the high model performance and linear trend, predictions of genetic diversity were underestimated by 8.2% for allelic richness and 22.4% for expected heterozygosity when compared to observed data. Study and species-specific aspects (null model) were crucial components of genetic diversity, explaining up to 56% of genetic variance. Indeed, the sampling design, the number of sampled populations, the geographic extension of the study, unique species traits, the selection of genetic markers and their respective resolution, as well as laboratory conditions can influence the estimates of genetic diversity35,36,37,38. Yet, the inclusion of the niche centroid distances explained an additional 27.2% of genetic variability for allelic richness and 22% for expected heterozygosity. Specifically, LGM climate conditions emerge as a key driver shaping the genetic diversity of marine forest species, with contemporary dynamics playing a secondary role, and predicting higher diversity in regions of climatic optimum. These regions represent climatic refugia of long-term persistence, as conditions were optimal in the past and populations continue to persist there today10. High genetic diversity in long-term climatic refugia has been previously hypothesized for individual species11,24,30,31,32, but here we provide a global unified hypothesis that applies to multiple cold and temperate marine forest species and regions. Further, by disentangling the role of LGM and contemporary climate conditions, we build upon previous global studies that used simplistic latitudinal models to predict diversity for different ecological groups17,19,26. Such simplistic models are unable to unravel the potential underlying drivers of genetic diversity that may be operating at the latitudinal level39. Our findings of primarily LGM conditions shaping diversity are in line with global studies for terrestrial mammals18 but contrast those on terrestrial plant and animal diversity, which found contemporary conditions being the main driver of diversity8. The contrasting results among different ecological groups and between terrestrial and marine environments could potentially be attributed to variations in ecological traits (e.g., dispersal), life history characteristics (e.g., reproduction) and distinct biogeographic histories8, as well as different levels of exposure to anthropogenic pressures that may have influenced genetic diversity17. These differences further emphasize the importance of accounting for both historical and contemporary climatic influences when estimating genetic diversity13,14. Nevertheless, species have complex biogeographic and evolutionary histories and additional drivers may further contribute to the genetic diversity patterns observed today40. For instance, although not considered in the models, oceanographic connectivity can influence the genetic diversity patterns of marine forest species globally41.

The prediction of genetic diversity patterns for 280 cold and temperate marine forest species permitted mapping the global genetic diversity hotspots. Overall, model estimates were consistent, and biogeographical predictions of allelic richness matched those of expected heterozygosity. High-diversity hotspots were mainly predicted at mid-latitudes of the north-eastern Pacific, north-eastern Atlantic and southern Australia, in line with previous studies2,42,43,44 and corroborating expectations of LGM climate refugia regions for marine forest species9,10. Indeed, for species whose distributions extended from mid to high latitudes, the highest genetic diversity was commonly predicted at lower latitudes (see individual maps in Supplementary Information). Yet, regional hotspots of genetic diversity were also predicted in high-latitude regions, such as the coasts of Norway, Iceland and the Aleutian Islands. Note that, species with exclusively high latitude/polar distributions (e.g., Laminaria solidungula) are expected to have high diversity at polar latitudes. Further, recent studies have challenged the notion of generalized low diversity in high-latitude populations due to bottlenecks in post-LGM recolonizations. Instead, insights based on genetic diversity data and hindcasts of LGM ice coverage indicate the potential existence of regional high-latitude periglacial refugia, that could have supported the long-term persistence of marine forest species42,44. Such refugia would have contributed to increased genetic diversity, as predicted by our models and confirmed for multiple Arctic species42,44. Some marine forest taxa also display unexpectedly high genetic diversity in polar regions due to admixture during post-glacial expansions from multiple genetically distinct sources45,46. In contrast, at lower tropical latitudes, LGM effects are hypothesized to have been less impactful on the distribution of species. However, the lack of intraspecific genetic diversity data for tropical marine forest species (literature review; Supplementary Data 1) precludes any robust conclusions on potential genetic diversity imprints. Several studies have highlighted a significant underestimation of species diversity of dominant tropical brown seaweeds47,48, but it is unclear whether species richness translates to genetic diversity in tropical latitudes. At least for marine fishes, patterns are not that clear, with mitochondrial genetic diversity being highest near the equator, while nuclear genetic diversity did not follow a geographic pattern19,49.

For cold and temperate species, the predictions of genetic diversity largely overlapped the previously inferred species richness patterns33, suggesting common underlying drivers shaping both genetic and species diversity. Long-term persistence over geological times in combination with high speciation rates could have contributed to the congruence of genetic and species diversity10,34. Such spatial covariation between genetic and species diversity has been previously demonstrated for many different ecological groups26, suggesting that eco-evolutionary processes can act simultaneously on genetic and species diversity. The better correlation of species richness and gene diversity more than allelic richness might reflect the latter being more affected by recent bottlenecks. Specifically for marine forests, the highest genetic diversity was consistently predicted in regions of high species richness. The opposite pattern of high species richness and low genetic diversity was not predicted.

While our study provides key insights into the global genetic diversity patterns of marine forest species, it is subject to several limitations that should be acknowledged. These limitations arise from both data-related and conceptual aspects. First, the genetic data used to develop the predictive models were collected from existing literature, carrying potential spatial and species biases26. For example, the oversampling of certain regions (e.g., northeastern Atlantic compared to South America; Fig. 2) may have influenced diversity predictions37,38. Additionally, genetic diversity data were also unbalanced between species with temperate (22 species) and cold distributions (only 6 species), highlighting the need for more comprehensive sampling, both geographically and taxonomically. Another limitation may lie in the resolution of the genetic markers used, with future uses of more advanced genomic techniques potentially providing a more comprehensive understanding of genetic diversity and the evolutionary processes shaping it. Further, genetic diversity estimates are not directly comparable among studies, due to different study designs, methodological approaches, and research scopes50, impacting predictions, as indicated by the substantial part of genetic variability explained by study-related aspects. Specifically, our model is unable to predict the effects of such study-related aspects, with diversity estimates inferred exclusively from species-specific niche centroid distances. Additional uncertainties may arise from the quality of environmental data for LGM conditions (e.g., nutrient availability estimates). However, temperature, the primary environmental driver defining marine forest niches33, has shown a good agreement for LGM estimates when tested against independent data51. Lastly, the environmental niche of each species was captured from available distribution range maps that have been produced with species distribution modelling. It is important to note that these maps may not fully represent the entire species niche, given the inherent limitations of this approach29,33.

The global relationships here found are especially remarkable considering all the uncertainties above mentioned. Despite those shortfalls, our study establishes new baseline information on the global genetic diversity patterns of marine forest species, that are provided openly and in high resolution (0.08°). These insights can be used in multiple applications for sustainability52 and can be particularly beneficial for countries that may lack the resources, capacity or funding required to conduct extensive genetic analyses. Specifically, the identification of genetic diversity hotspots can guide spatial conservation and prioritization, in alignment with the Post-2020 Global Framework for Biodiversity53. Conservation of rich gene pools may contribute to the preservation of genes responsible for species adaptation and evolution9, potentially increasing populations’ resilience under climate change15,16. In this scope, our results can guide stakeholders and managers in the implementation of marine protected areas (MPAs), to mitigate anthropogenic threats (e.g., degradation, overexploitation) on populations with high genetic diversity54,55. These MPAs could be integrated into networks that maximize connectivity, thus, promoting gene flow and further enhancing population resilience56,57, a mandate often overlooked in marine spatial planning but integral to the Post-2020 Global Framework for Biodiversity53,58. The geographical variation in genetic patterns revealed disproportional roles of individual countries in the preservation of rich genetic pools. Notably, countries such as the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Ireland, Norway and Australia, emerged as key custodians of major genetic diversity hotspots. As such, they bear an increased responsibility for conserving the rich genetic pools for multiple marine forest species. Moreover, our baseline estimates on genetic diversity patterns can be coupled with range shift projections to anticipate future climate change impacts on the genetic diversity pools of marine forest species42. Lastly, our results can also be used to inform restoration actions, by promoting the restoration of genetically rich populations while maintaining their genetic traits by the selection of both non-divergent and similarly diverse populations as donors, thereby increasing the likelihood of restoration success59,60. Yet, it also shows the challenge in recovering high diversity by restoration, as once ancient persistent populations that evolved in past climate optima are lost, the reconstruction of their previous evolutionary potential levels is not easily feasible within desirable time scales of human generations.

In conclusion, this study highlights the importance of long-term population persistence in creating biodiversity hotspots by showing how past climatic optima can be the main drivers of present biodiversity patterns, more than present population conditions. Furthermore, our estimates provide a global overview of the biogeographic genetic diversity patterns of marine forest species. This is also timely in improving the information for planning the allocation of conservation resources to safeguard biodiversity in the face of climate change.

Methods

Intraspecific genetic data

A literature review was conducted in the “Web of Science” platform (accessed in July 2023) to compile intraspecific genetic diversity data for species of brown macroalgae, regardless of marine forest formation traits. The combination of the words “genetic diversity”, “genetic differentiation” or “phylogeography” with “algae”, “macroalgae”, “seaweed” or “heterokontophyta” were used to retrieve a list of potential studies. As initial selection criteria, studies were retained when reporting at least one genetic diversity metric (e.g., allelic richness, expected heterozygosity, observed heterozygosity, etc.) of wild, native populations, specifying the species name, geographic location (longitude and latitude), sample size and genetic marker used (e.g., microsatellite, mitochondrial DNA, etc.).

Considering that regional studies are not expected to enable the detection of genetic and climatic variability (e.g., LGM effects), further filtering retained studies reporting genetic data spanning at least two marine ecoregions61 (Suplementary Data 1). Additionally, when multiple studies reported genetic diversity for the same species, the study covering the largest geographic area was retained (i.e., spanning a larger number of marine ecoregions61). When multiple studies reported genetic diversity for the same species, but sampling spanned different ecoregions, all genetic data were retained. When studies reporting genetic diversity for the same species spanned the same ecoregions but reported different genetic markers and/or genetic diversity metrics, all genetic data were retained. When multiple studies reported genetic diversity for the same species, ecoregions, genetic diversity metrics and genetic markers, the study with more sampling sites (n) was retained. A list of the revised studies and justifications for their selection or rejection are shown in Supplementary Data 1. Lastly, the genetic diversity dataset of Macrocystis pyrifera along its global distribution32 was divided into two subsets in light of recent findings of extreme genetic divergence between the two morphs of M. pyrifera and M. integrifolia62,63. Accordingly, in the northern hemisphere, M. integrifolia was considered to occur from Stillwater Cove, USA (36.56°N, 121.94°W) northwards and M. pyrifera southwards62,64. In the southern hemisphere, M. integrifolia was considered to occur from La Boca, Chile (33.90°S, 71.83°W) northwards and M. pyrifera southwards62,64. M. integrifolia distribution was considered only in the Americas, contrary to M. pyrifera which is distributed across the Antarctic and subantarctic islands, including New Zealand, Australia and South Africa64. Note that the taxonomic names used in the original studies were retained here for clarity, to allow easy tracking of the data sources, despite taxonomical updates (e.g., Cystoseira tamariscifolia updated to Ericaria selaginoides), because the goal was to describe global biogeographic patterns and not species-specific information.

Environmental data

A set of environmental variables was selected as potential predictors defining the niche of marine forest species based on their biological relevance33 and their availability for contemporary and LGM climatic conditions. Namely, the variables of long-term temperature (minimum and maximum), nitrate, phosphate, salinity, and sea ice coverage were extracted from Bio-ORACLE V2 for contemporary conditions65,66. The same variables for LGM conditions were accessed from previously developed datasets found in two publications32,51.

Capturing environmental niche and centroid

Since species distributions are shaped by their environmental niches—the range of suitable conditions for their survival—we used available contemporary distribution range maps29 to estimate the environmental niche and its centroid (Fig. 1) for each species with genetic data (29 species in total; see results). To this end, we extracted environmental data for the six pre-selected environmental predictors across the species distribution range and performed a Principal Component Analysis. This approach allowed us to address potential collinearity among predictors and define the species’ niche. The niche centroid (NC), representing optimal conditions for the species, was calculated as the mean value of each environmental predictor across the species range. Although species distributions may change over time, we assumed the niche centroid to be stable due to niche conservatism67, reflecting the species’ fundamental environmental preferences.

To explore the relationship between genetic diversity and environmental conditions, we calculated the Euclidian distance between the niche centroid and the local environmental conditions of each population for which genetic data was compiled. These distances were computed for both contemporary environmental conditions and those during LGM, allowing us to evaluate how the sampled populations were positioned relative to their niche centroid in both time periods (Fig. 1).

This process was repeated for all species for which genetic data was available, resulting in a comprehensive matrix that includes information on the study ID, species name, coordinates of the sampled population, genetic marker, genetic diversity metric (e.g., allelic richness) and its measure, and the distances between populations and the niche centroid under contemporary and LGM conditions (Supplementary Data 2).

Modelling genetic diversity

The machine learning algorithm Boosted Regression Trees (BRT) was chosen to model the genetic diversity (allelic richness and expected heterozygosity) of marine forest species because of its ability to handle nonlinear relationships and its high predictive performance68. This algorithm fitted a “Gaussian” distribution between genetic diversity estimates and five predictors, namely, the distance from the niche centroid under contemporary and past LGM conditions, and, as random effect variables, the study, the species and the genetic marker used. Monotonicity constraints, based on the expected outcomes of each predictor effect on genetic diversity, were also implemented to reduce overfitting and improve spatial transferability and interpretability69. Specifically, we implemented a negative monotonicity effect for niche centroid distances under contemporary and LGM conditions and an arbitrary effect for the study, species and genetic markers. Model hyperparametrization was optimized through tenfold cross-validation33,68. In this process, the “grid search” approach trained all hyperparameter combinations of number of trees (from 50 to 500, by step of 50), tree complexity (2 to 5, by step of 1), learning rate (from 0.1 to 1, by step of 0.1) and the fraction of training set observation (0.25 to 1, by step of 0.25). The model’s predictive performance was evaluated with deviance explained in one independent fold withheld at a time. Optimal hyperparameters were selected as those producing the highest deviance explained in cross-validation. The relative contribution of each predictor to the model was also computed70. A null model using the study, the species and the genetic marker as predictor variables was developed to allow estimating the relative contribution of distance from the niche centroid under contemporary and LGM conditions on the model’s predictive performance.

Predicting global marine forest genetic diversity

The developed BRT model was transferred to available distribution range maps of marine forest species29 to predict genetic diversity (allelic richness and expected heterozygosity) patterns beyond the species for which genetic data was available. We restricted the model application on cold and temperate brown macroalgae species because (1) genetic data were mostly available for cold and temperate species, with data reported only for one tropical species (Sargassum liebmannii, Fig. 2), and (2) LGM effects are expected to be less profound on tropical species2,10,12. Therefore, a subset of the available marine forest distribution range maps29 was selected to exclude tropical species based on the temperature range of species distributions. The temperature ranges for each species were inferred by overlaying their distribution with the long-term average temperature from 2010–202065. Species were defined as cold when the 95th percentile of their distribution was below 15 °C, as temperate between 15 and 25 °C, and as tropical above 25 °C (Supplementary Data 3)71.

Genetic diversity was predicted with the previously produced BRT model, using the distances from the niche centroid as predictors and by fixing the study, the species and genetic marker effects to zero, in line with common practices for mixed effect modelling72. Distribution maps reflecting the potential patterns of genetic diversity were developed per species. Global hotspots of diversity were inferred by summing individual species predictions and estimating the average diversity per pixel33,73. The correlation between the predicted genetic diversity as allelic richness and expected heterozygosity was tested through a two-sided Pearson correlation test. Further, species richness per pixel was estimated from available distribution range maps29 and its correlation with genetic diversity was tested through a two-sided Pearson correlation test. Lastly, a global classification based simultaneously on species richness and genetic diversity was produced by dividing species richness and genetic diversity into quartiles, forming 16 categories of quartile combinations19,74.

All analyses were performed in R75. The data, the R code and the produced predicted genetic diversity layers are openly available in a permanent repository76.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Code availability

The R code used for this study is available in a permanent repository76.

References

Ellegren, H. & Galtier, N. Determinants of genetic diversity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 422–433. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.58 (2016).

Maggs, C. A. et al. Evaluating signatures of glacial refugia for North Atlantic benthic marine taxa. Ecology 89, S108–S122 (2008).

Osorio-Olvera, L., Soberón, J. & Falconi, M. On population abundance and niche structure. Ecography 42, 1415–1425 (2019).

Lira-Noriega, A. & Manthey, J. D. Relationship of genetic diversity and niche centrality: a survey and analysis. Evolution 68, 1082–1093 (2014).

Martínez-Meyer, E., Díaz-Porras, D., Peterson, A. T. & Yáñez-Arenas, C. Ecological niche structure and rangewide abundance patterns of species. Biol. Lett. 9, 20120637 (2013).

Ochoa-Zavala, M. et al. Reduction of genetic variation When far from the niche centroid: prediction for mangrove species. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2021.795365 (2022).

Hutchinson, G. E. Concluding remarks. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 22, 415–427 (1957).

De Kort, H. et al. Life history, climate and biogeography interactively affect worldwide genetic diversity of plant and animal populations. Nat. Commun. 12, 516 (2021).

Hampe, A. & Petit, R. J. Conserving biodiversity under climate change: the rear edge matters. Ecol. Lett. 8, 461–467 (2005).

Hewitt, G. M. Genetic consequences of climatic oscillations in the quaternary. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 359, 183–195 (2004).

Assis, J., Serrão, E. A., Claro, B., Perrin, C. & Pearson, G. A. Climate-driven range shifts explain the distribution of extant gene pools and predict future loss of unique lineages in a marine brown alga. Mol. Ecol. 23, 2797–2810 (2014).

Neiva, J. et al. Climate oscillations, range shifts and phylogeographic patterns of North Atlantic Fucaceae. In Seaweed Phylogeography: Adaptation and Evolution of Seaweeds under Environmental Change 279–308 (Springer, 2016).

Eckert, C. G., Samis, K. E. & Lougheed, S. C. Genetic variation across species’ geographical ranges: the central-marginal hypothesis and beyond. Mol. Ecol. 17, 1170–1188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03659.x (2008).

Pironon, S. et al. Geographic variation in genetic and demographic performance: new insights from an old biogeographical paradigm. Biol. Rev. 92, 1877–1909 (2017).

Vásquez, C., Quiñones, R. A., Brante, A. & Hernández-Miranda, E. Genetic diversity and resilience in benthic marine populations. Rev. Chil. Historia Nat. 96, 4 (2023).

Wernberg, T. et al. Genetic diversity and kelp forest vulnerability to climatic stress. Sci. Rep. 8, 1851 (2018).

Miraldo, A. et al. An Anthropocene map of genetic diversity. Science 353, 1532–1535 (2016).

Theodoridis, S. et al. Evolutionary history and past climate change shape the distribution of genetic diversity in terrestrial mammals. Nat. Commun. 11, 2557 (2020).

Manel, S. et al. Global determinants of freshwater and marine fish genetic diversity. Nat. Commun. 11, 692 (2020).

Teagle, H., Hawkins, S. J., Moore, P. J. & Smale, D. A. The role of kelp species as biogenic habitat formers in coastal marine ecosystems. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 492, 81–98 (2017).

Wernberg, T., Krumhansl, K., Filbee-Dexter, K. & Pedersen, M. F. Status and trends for the world’s Kelp forests. in World Seas: an Environmental Evaluation, 57–78 (Elsevier Ltd., 2019).

Eger, A. M. et al. The value of ecosystem services in global marine kelp forests. Nat. Commun. 14, (2023).

Convention on Biological Diversity. Decision Adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity at Its Tenth Meeting. Decision X/2. The Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 and the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-10/cop-10-dec-02-en.pdf (2010).

Neiva, J. et al. Genes left behind: climate change threatens cryptic genetic diversity in the canopy-forming seaweed Bifurcaria bifurcata. PLoS One 10, e0131530 (2015).

Song, X. H. et al. Climate-induced range shifts shaped the present and threaten the future genetic variability of a marine brown alga in the Northwest Pacific. Evol. Appl 14, 1867–1879 (2021).

Figuerola-Ferrando, L. et al. Global patterns and drivers of genetic diversity among marine habitat-forming species. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13685 (2023).

Assis, J. et al. Past climate changes and strong oceanographic barriers structured low-latitude genetic relics for the golden kelp Laminaria ochroleuca. J. Biogeogr. 45, 2326–2336 (2018).

Bringloe, T. T. et al. Phylogeny and evolution of the brown algae. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 39, 281–321 (2020).

Gouvêa, L., Fragkopoulou, E., Legrand, T., Serrão, E. A. & Assis, J. Range map data of marine ecosystem structuring species under global climate change. Data Brief. 52, 110023 (2024).

Neiva, J., Assis, J., Fernandes, F., Pearson, G. A. & Serrão, E. A. Species distribution models and mitochondrial DNA phylogeography suggest an extensive biogeographical shift in the high-intertidal seaweed Pelvetia canaliculata. J. Biogeogr. 41, 1137–1148 (2014).

Assis, J. et al. High and distinct range-edge genetic diversity despite local bottlenecks. PLoS One 8, 1–11 (2013).

Assis, J. et al. Past climate-driven range shifts structuring intraspecific biodiversity levels of the giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) at global scales. Sci. Rep. 13, 12046 (2023).

Fragkopoulou, E. et al. Global biodiversity patterns of marine forests of brown macroalgae. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 31, 636–648 (2022).

Fine, P. V. A. Ecological and evolutionary drivers of geographic variation in species diversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 46, 369–392 (2015).

Zimmerman, S. J., Aldridge, C. L. & Oyler-Mccance, S. J. An empirical comparison of population genetic analyses using microsatellite and SNP data for a species of conservation concern. BMC Genom. 21, 382 (2020).

Borah, R. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure assessment using molecular markers and SPAR approach in Illicium griffithii, a medicinally important endangered species of Northeast India. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 19, 118 (2021).

Gloss, A. D., Steiner, M. C., Novembre, J. & Bergelson, J. The design of mapping populations: Impacts of geographic scale on genetic architecture and mapping efficacy for defense and immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2023.102399 (2023).

Aguirre-Liguori, J. A., Luna-Sánchez, J. A., Gasca-Pineda, J. & Eguiarte, L. E. Evaluation of the minimum sampling design for population genomic and microsatellite studies: an analysis based on wild maize. Front. Genet. 11, 870 (2020).

Procheş, Ş., Watkeys, M. K., Ramsay, L. F. & Cowling, R. M. Why we should be looking for longitudinal patterns in biodiversity. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2023.1032827 (2023).

Nielsen, E. S., Beger, M., Henriques, R. & von der Heyden, S. Neither historical climate nor contemporary range fully explain the extant patterns of molecular diversity in marine species. J. Biogeogr. 48, 2629–2644 (2021).

Legrand, T. et al. Unravelling the role of oceanographic connectivity in the distribution of genetic diversity of marine forests at the global scale. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 33, e13857 (2024).

Assis, J., Araújo, M. B. & Serrão, E. A. Projected climate changes threaten ancient refugia of kelp forests in the North Atlantic. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, e55–e66 (2017).

Provan, J. The effects of past, present and future climate change on range-wide genetic diversity in northern North Atlantic marine species. Front. Biogeogr. 5, 60–66 (2013).

Bringloe, T. T., Verbruggen, H. & Saunders, G. W. Unique biodiversity in Arctic marine forests is shaped by diverse recolonization pathways and far northern glacial refugia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 22590–22596 (2020).

Neiva, J. et al. Trans-Arctic asymmetries, melting pots and weak species cohesion in the low-dispersal amphiboreal seaweed Fucus distichus. Front. Ecol. Evol. 12, 1356987 (2024).

Neiva, J. et al. Glacial vicariance drives phylogeographic diversification in the amphi-boreal kelp Saccharina latissima. Sci. Rep. 8, 1112 (2018).

Vieira, C. et al. Global biogeography and diversification of a group of brown seaweeds (Phaeophyceae) driven by clade-specific evolutionary processes. J. Biogeogr. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14047 (2021).

Yip, Z. T., Quek, R. Z. B. & Huang, D. Historical biogeography of the widespread macroalga Sargassum (Fucales, Phaeophyceae). J. Phycol. 56, 300–309 (2020).

Clark, R. & Pinsky, M. Global patterns of genetic diversity in marine fishes. Authorea https://doi.org/10.22541/au.168726266.68173061/v1 (2023).

Skrbinšek, T. et al. Using a reference population yardstick to calibrate and compare genetic diversity reported in different studies: an example from the brown bear. Heredity 109, 299–305 (2012).

Assis, J. et al. Ocean currents shape the genetic structure of a kelp in southwestern Africa. J. Biogeogr. 49, 822–835 (2022).

Thomson, A. I. et al. Charting a course for genetic diversity in the UN Decade of Ocean Science. Evol. Appl. 14, 1497–1518 (2021).

Convention on Biological Diversity. Draft of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. Accessed at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/409e/19ae/369752b245f05e88f760aeb3/wg2020-05-l-02-en.pdf (2022).

Andrello, M., Manel, S., Vilcot, M., Xuereb, A. & D’Aloia, C. C. Benefits of genetic data for spatial conservation planning in coastal habitats. Cambridge Prisms: Coast. Futures 1–38 https://doi.org/10.1017/cft.2023.16 (2023).

Andrello, M. et al. Evolving spatial conservation prioritization with intraspecific genetic data. Trends Ecol. Evol. 37, 553–564 (2022).

Magris, R. A. et al. Biologically representative and well-connected marine reserves enhance biodiversity persistence in conservation planning. Conserv. Lett. 11, 1–10 (2018).

Abecasis, D., Fragkopoulou, E., Claro, B. & Assis, J. Biophysical modelling and graph theory identify key connectivity hubs in the Mediterranean marine reserve network. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 1000687 (2023).

Assis, J. et al. Weak biodiversity connectivity in the European network of no-take marine protected areas. Sci. Total Environ. 773, 145664 (2021).

Reynolds, L. K., McGlathery, K. J. & Waycott, M. Genetic diversity enhances restoration success by augmenting ecosystem services. PLoS One 7, e38397 (2012).

Wood, G. et al. Using genomics to design and evaluate the performance of underwater forest restoration. J. Appl. Ecol. 57, 1988–1998 (2020).

Spalding, M. D. et al. Marine ecoregions of the world: a bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. Bioscience 57, 573–583 (2007).

Gonzalez, S. T., Alberto, F. & Molano, G. Whole-genome sequencing distinguishes the two most common giant kelp ecomorphs. Evolution 77, 1354–1369 (2023).

Gonzalez, S. T. & Raimondi, P. T. Experimental assessment of environmental versus genetic influences on Macrocystis morphology. Ecosphere 15, e4959 (2024).

Schiel, D. R. & Foster, M. S. Introduction to giant kelp forests worldwide in the biology and ecology of giant Kelp forests. https://doi.org/10.1525/j.ctt14btfvw.6 (2015)

Tyberghein, L. et al. Bio-ORACLE: A global environmental dataset for marine species distribution modelling. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 21, 272–281 (2012).

Assis, J. et al. Bio-ORACLE v2.0: Extending marine data layers for bioclimatic modelling. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 27, 277–284 (2018).

Wiens, J. J. et al. Niche conservatism as an emerging principle in ecology and conservation biology. Ecol. Lett. 13, 1310–1324 (2010).

Elith, J. & Leathwick, J. Boosted regression trees for ecological modeling. R documentation. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=3fa2b8826c881d732169995869b9d356c6996029 (2017).

Hofner, B., Müller, J. & Hothorn, T. Monotonicity-constrained species distribution models. Ecology 92, 1895–1901 (2011).

Elith, J., Leathwick, J. R. & Hastie, T. A working guide to boosted regression trees. J. Anim. Ecol. 77, 802–813 (2008).

Pessarrodona, A. et al. Global seaweed productivity. Sci. Adv. 8, 2465 (2022).

Welham, S., Cullis, B., Gogel, B., Gilmour, A. & Thompson, R. Prediction in linear mixed models. Aust. N.Z. J. Stat. 46, 325–347 (2004).

Guisan, A. & Rahbek, C. SESAM—a new framework integrating macroecological and species distribution models for predicting spatio-temporal patterns of species assemblages. J. Biogeogr. 38, 1433–1444 (2011).

Fragkopoulou, E. et al. Marine biodiversity exposed to prolonged and intense subsurface heatwaves. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 1114–1121 (2023).

R Development Core Team, 2018. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

Fragkopoulou, E. et al. Global intraspecific diversity of marine forest of brown macroalgae predicted by past climate conditions. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25713651 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study received Portuguese national funds from FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology through projects UIDB/04326/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04326/2020), UIDP/04326/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDP/04326/2020), LA/P/0101/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0101/2020), PTDC/BIA-CBI/6515/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/PTDC/BIA-CBI/6515/2020) and the EU BiodivRestore-253 (FCT: DivRestore/0013/2020), the grant SFRH/BD/144878/2019 (https://doi.org/10.54499/SFRH/BD/144878/2019) to E.F. and the Scientific Employment Stimulus 2022.00861.CEECIND (https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.00861.CEECIND/CP1729/CT0003) to J.A., and Pew Marine Fellowship to E.A.S. This study was funded by the European Union under iCULTURE Project GA number 101082010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.F. and J.A. conceived the project and developed the methodology. E.F. did the analyses and visualization with the supervision of J.A., E.A.S., and O.D.C. E.F. wrote the original draft, and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Sara Melo-Merino and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Eoin O’Gorman and Michele Repetto. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fragkopoulou, E., Serrão, E.A., De Clerck, O. et al. Global intraspecific diversity of marine forests of brown macroalgae predicted by past climate conditions. Commun Biol 8, 726 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08023-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08023-w