Abstract

Mosquito-borne orthoflaviviruses such as dengue and Zika viruses, and alphaviruses such as chikungunya viruses continue to pose global health threats, necessitating innovative vector control strategies. Small antibodies (sAb) such as single-chain variable fragments (scFv) and single-domain antibodies (sdAb) against dengue and chikungunya viral proteins have been applied to neutralize viral infections in mouse and human primary cells. Here, we explored the use of these protective sAbs for the development of transgenic mosquito-based arboviral disease control strategies. We expressed scFv against orthoflaviviruses and sdAb against alphaviruses using a dual bloodmeal-inducible midgut-specific promoter, AeG12, achieving strong expression of both orthoflavivirus scFv and alphavirus sdAb in Aedes aegypti midguts. The presence of sAbs significantly reduced mosquito midgut infections with multiple orthoflaviviruses and alphaviruses, such as dengue, Zika, chikungunya and Mayaro viruses, thus compromising viral transmission by the transgenic mosquitoes. We further augmented virus-blocking by co-expression of sAbs and the siRNA pathway factor Dcr2, proving the utility of combinatorial virus targeting by mechanistically independent antiviral effectors. Our results demonstrate the potential of expressing broadly neutralizing sAbs in mosquitoes, particularly in combination with enhancing endogenous antiviral pathways, as a promising strategy to reduce arbovirus transmission by mosquitoes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Orthoflavivirus such as dengue virus (DENV) and Zika virus (ZIKV) in the family Flaviviridae, and alphaviruses such as chikungunya virus (CHIKV) and Mayaro virus (MAYV) in the family Togaviridae, represent two most important arthropod-borne virus (arbovirus) classes that cause severe diseases in humans1. These viruses are primarily transmitted and spread by Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus vectors and cause major public health and economic burdens worldwide. Climate change, globalization, and urbanization have enabled Aedes mosquitoes to expand their geographical range into previously unaffected areas, and they have re-emerged in endemic areas where they had previously been prevalent, thereby increasing the number of cases and outbreaks of mosquito-borne viral diseases2,3. Dengue is endemic in more than 120 countries and has expanded its range in recent decades, resulting in approximately 390 million infections annually4,5. Because of a lack of effective medication and vaccines to treat and prevent most arboviral diseases, vector control is still the most effective, and in some cases, the only method to prevent and control the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases. However, conventional vector control methods, such as the reduction of mosquito populations using chemical insecticides, are facing challenges because of widespread insecticide resistance in Aedes mosquitoes6,7. Therefore, alternative vector control strategies such as Wolbachia techniques, sterile insect techniques, and genetic control have all been proposed to fight human arboviral diseases8,9.

Both orthoflaviviruses and alphaviruses are positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses. The orthoflavivirus genome is approximately 10 to 12 kb in length and contains a single open-reading frame (ORF) that encodes one polyprotein, which can be processed into three structural proteins, the capsid (C), pre-membrane (prM), and envelope (E) proteins; and seven nonstructural proteins: NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS510,11. The alphavirus genome is approximately 11.7 kb long and contains two ORFs, one nonstructural and one structural, which encode for four nonstructural proteins (nsP1-4) and five structural proteins (capsid, E1-3, and 6 K), respectively12,13. To combat emerging orthoflaviviruses and alphaviruses, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against conserved viral proteins have been applied to neutralize virus infection and are crucial for the development of vaccines14,15,16,17. Several mAbs targeting various nonstructural and structural viral proteins have been developed and shown to protect mouse and human primary cells from infection with multiple viruses of either the Orthoflavivirus or Alphavirus genus14,16,18,19,20.

Mosquito transgenic-based strategies, including population replacement and suppression21,22, have emerged as promising future strategies for mosquito-borne disease control. The success of population replacement relies on generating pathogen-resistant (refractory) mosquitoes that are not infected by and/or incapable of transmitting mosquito-borne human pathogens8,21,22. Various effector genes, including components of the small interfering RNA (siRNA) and JAK/STAT pathways23,24, synthetic small RNAs of orthoflaviviruses25,26, and long hairpin RNA of orthoflaviviruses27,28, have been engineered in Ae. aegypti to generate refractory mosquitoes. Here, we generated a transgenic mosquito line that overexpresses small antibodies against both orthoflaviviruses and alphaviruses under one endogenous midgut-specific, bloodmeal-inducible promoter. These transgenic mosquitoes conferred strong resistance to both orthoflaviviruses and alphaviruses, including DENV-2, DENV-4, ZIKV and CHIKV, and MAYV, respectively. We further proved the utility of blocking viruses with two independent mechanisms by co-expressing small antibodies with the siRNA pathway factor Dcr2.

Results

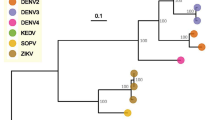

Small antibodies with broad neutralization of orthoflavivirus and alphavirus infection

We searched for small antibodies that were able to neutralize orthoflavivirus or alphavirus infection in mammalian cells or in vivo. The criteria that we used for this search were: 1) small-size antibodies, such as single-chain variable fragment (scFv) or single-domain antibodies (sdAb); 2) broad-spectrum antibodies capable of neutralizing multiple medically important arboviruses of the same genus; 3) antibodies with amino acid sequences readily available. Based on these criteria, we found one small antibody for orthoflaviviruses, anti-DENV NS1 scFv of 2B7 (DENV scFv), and one for alphaviruses, anti-CHIKV sdAb CC3 (CHIKV sdAb). Anti-DENV NS1 mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb) 2B7 was first identified as an inhibitor of NS1-induced endothelial hyperpermeability in mice18, further confirming that scFv of 2B7 could bind tightly to NS1 from multiple orthoflaviviruses such as DENV1-4, ZIKV, and WNV29. Anti-CHIKV sdAb CC3 was cloned from peripheral white blood cells immunized with CHIKV virus-like particles30 and further shown to be capable of neutralizing multiple alphaviruses, including CHIKV, MAYV, and Ross River virus (RRV)19. The amino acid and nucleotide sequences of DENV scFv and CHIKV sdAb optimized to Drosophila are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Identification of a midgut-specific promoter with the ability to drive strong dual gene expression in both directions

To generate a transgenic mosquito line that can inhibit the infection of both orthoflaviviruses and alphaviruses, we expressed DENV scFv and CHIKV sdAb concurrently in the same mosquito, specifically in the midgut, which is the first tissue to be infected by an arbovirus. According to the published transcriptome data for the midguts of blood-fed mosquitoes31, we found that two genes, AAEL009165 and AAEL013118, are significantly upregulated in the midguts of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes at 3–24 h after blood-feeding (Supplementary Fig. 2). These two genes are highly conserved and closely related to the An. gambiae G12 gene (Supplementary Fig. 3). Interestingly, the two genes are separated by a sequence of 1777 bp and are translated in opposite directions, indicating that the 1777-bp sequence is the promoter for both genes (Fig. 1a). Thus, the promoter (AeG12) meets the requirement of driving the expression of both small antibodies concurrently in the same tissue. Next, we cloned this promoter, alongside the sequences of both small antibodies, into a piggyBac-EGFP-borne plasmid (Fig. 1b). To monitor the expression of transgenes, we added an HA tag and a V5 tag to DENV scFv and CHIKV sdAb, respectively.

a Scheme showing the AeG12 promoter driving the expression of two G12-like genes in opposite directions. b Scheme of the donor plasmid (piggyBacG12sAb-EGFP) containing the anti-DENV NS1 scFv, anti-CHIKV sdAb CC3, and AeG12 promoter. The numbers indicate the size of the genes. 2B7-HV and 2B7-LV: heavy variable (HV) and light variable (LV) domains of 2B7 monoclonal antibodies; scFv: single-chain variable fragment; sdAb: single-domain antibodies; SV40, polyadenylation signal of simian virus 40 VP1 gene; 3xP3, eye tissue-specific promoter. c Transgenic male and female mosquitoes with fluorescent green eyes. d Effect of expressing small antibodies on infection with Mayaro (MAYV) and dengue viruses (DENV) in midguts. Wild-type (WT) and various pools of heterozygous transgenic mosquitoes were infected with MAYV or DENV-2, and virus titer was determined in midguts by plaque assay at 2 days post-infection (dpi) with MAYV and 7 dpi with DENV-2, respectively. The infection prevalence is indicated below the graph. The significance of virus titers between transgenic mosquitoes and WT was determined by an unpaired two-sided Mann-Whitney test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. For MAYV infection, n = 40 (WT), n = 24 (P1), n = 40 (P2), n = 32 (P3), n = 18 (P4), and n = 29 (P11). For DENV-2 infection, n = 35 (WT, P1 and P2), n = 31 (P3), n = 26 (P4), and n = 30 (P11). e–i Fitness parameters of G12sAb mosquitoes as compared to those of WT mosquitoes. e larval development and pupation rate, n = 4. f Body weight of adult females and males, n = 8. g Blood-feeding capability of females. n = 8. h Fecundity and fertility. n = 34. i Longevity of blood-fed females and sugar-fed males. The P value was determined by a Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test for (e) and a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test for (i). Male: n = 85 (WT), n = 78 (G12sAb); female: n = 85 (WT), n = 73 (G12sAb). Statistical significance between WT and G12sAb was determined by an unpaired two-sided t-test for (f) and (g) and an unpaired two-sided Mann-Whitney test for (h). ns, not significant. Source data are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Generation of transgenic mosquitoes expressing anti-orthoflavivirus and anti-alphavirus small antibodies in the midgut

The final plasmids (piggyBacG12sAb-EGFP) were injected with piggyBac transposase mRNA into the newly laid eggs of Higgs’s white eye (WHE) mosquitoes. A total of five pools of transgenic mosquitoes were recovered with fluorescent green eyes (Fig. 1c). Then, we infected different pools of transgenic mosquitoes with MAYV and DENV-2. The midguts were dissected from transgenic and WT females at 2 days post-infection (dpi) for MAYV and 7 dpi for DENV-2, and the virus titers from individual midgut samples were determined by plaque assay. As compared to WT midguts, midguts from four of the five and three of the five transgenic mosquito pools, respectively, exhibited a significant inhibition against MAYV and DENV-2 infection (Fig. 1d). Considering inhibition of both MAYV and DENV-2, we selected P1 (hereafter named G12sAb) for future studies. Then we used inverse PCR to determine that the insertion site of the transgene into the G12sAb line was located at AaegL5_3:380278350 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

After in-crossing for another five generations, a homozygous transgenic line was established with over 95% of offspring possessing green, fluorescent eyes. Multiple fitness parameters, including larval development, pupation rate, adult body weight, blood-feeding capacity, fecundity, fertility, and longevity, were compared between G12sAb and WT mosquitoes. The results showed that only female longevity was significantly shortened in G12sAb, which had a median survival of 22 days versus 32 days for WT. All other tested parameters showed no difference between G12sAb and WT (Fig. 1e–i). Therefore, AeG12 promoter-driven expression of small antibodies in midguts caused a slight decline in fitness that nevertheless would further decrease virus transmission potential.

High induction of small antibodies in the midguts of transgenic mosquitoes after ingestion of a bloodmeal

To confirm the expression of DENV scFv and CHIKV sdAb in the midguts of transgenic mosquitoes, we used Western blotting and immunofluorescence assays (IFAs), together with their respective tag antibodies and qPCRs to check the protein and mRNA levels, respectively, of the transgenes. The Western blot results showed that DENV scFv was highly prevalent in the midguts between 12 and 24 h after blood-feeding (BF) (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 5a), and CHIKV sdAb was highly expressed in the midguts between 24 and 36 h post-BF (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 5b-c). We did not detect DENV scFv or CHIKV sdAb in the midguts of blood-fed WT at 24 h post-BF, in the midguts of sugar-fed transgenic mosquitoes, or in the carcasses of blood-fed transgenic mosquitoes at 24 h post-BF, suggesting that small antibodies are specifically expressed in the midguts of transgenic mosquitoes after the ingestion of a bloodmeal. The IFA results further confirmed DENV scFv and CHIKV sdAb were highly expressed in most of the midgut cells of G12sAb mosquitoes at 24 h post-BF (Fig. 2c) but were only detected in a few of midgut cells at 36 h post-BF (Fig. 2d). qPCR data also showed that DENV NS1 2B7-HV and 2B7-LV were specifically expressed in G12sAb mosquitoes after the ingestion of a blood meal and were highly induced in midguts at 12 and 24 h post-BF (Fig. 2e), consistent with the protein levels of DENV scFv detected by Western blotting (Supplementary Fig. 6). The expression of CHIKV sdAb was significantly increased in the midguts of G12sAb mosquitoes at 24 and 36 h post-BF (Fig. 2e). Taken together, our data demonstrates that G12sAb mosquitoes express a large amount of DENV scFv and CHIKV sdAb in midgut cells after a bloodmeal is taken.

Western blot detection of DENV NS1 scFv (a) and anti-CHIKV sdAb (b) protein in midguts (MG) and carcasses (CA) of wild-type (WT) and transgenic mosquitoes (G12sAb) at various times post-blood-feeding (BF). β-actin was used as a loading control, and numbers on the left of images indicate the molecular size (kDa). IFA detection of DENV NS1 scFv (red) and anti-CHIKV sdAb (green) in midgut cells of mosquitoes at 24 h (c) and 36 h (d) post-BF. The zoomed areas are indicated as white boxes and shown in the correspondingly lower panels. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). e qPCR detection of orthoflavivirus NS1 2B7-HV and 2B7-LV, and CHIKV sdAb expression in midguts of WT and G12sAb mosquitoes at various times post-BF. f comparison of orthoflavivirus NS1 2B7-HV and 2B7-LV expression to AAEL01318 (left) and CHIKV sdAb expression to AAEL009165 (right) in midguts of WT and G12sAb mosquitoes at various times post-BF. Gene expression was detected by qPCR and normalized to the ribosome S7 expression. n = 3. Significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Source data are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

To determine the influence of the transgene on the expression of endogenous genes (AAEL009165 and AAEL01318) with the same promoter sequence, we measured the expression of these two genes in the midguts of G12sAb mosquitoes. Our data showed that the expression of both AAEL009165 and AAEL01318 was significantly induced in the midguts of WT and transgenic mosquitoes after ingestion of a bloodmeal, and about a 100,000-fold and 50,000-fold increase in AAEL01318 and AAEL009165, respectively, were observed in the midguts at 12 and 24 h post-BF (Supplementary Fig. 7). There was no difference in expression between AAEL009165 and AAEL01318 in the midguts at 24 h post-BF between WT and G12sAb mosquitoes (Fig. 2f). As compared to the expression of AAEL009165 and AAEL01318, the expression of both DENV scFv and CHIKV sdAb was slightly reduced in the midguts of G12sAb mosquitoes (Fig. 2f). These findings indicate that the AeG12 promoter efficiently drives the expression of two endogenous genes or two recombinant genes in opposite directions, and the presence of the transgenes does not affect the expression of endogenous genes that have the same promoter sequence.

The simultaneous expression of anti-orthoflavivirus and anti-alphavirus small antibodies in midguts suppresses multiple arboviruses

G12sAb homozygotes were infected with MAYV, ZIKV, DENV-2 and DENV-4, and the resulting virus titers were measured in the midguts and carcasses by plaque assay. The data show that G12sAb mosquitoes exhibited significantly reduced DENV-2, DENV-4, and ZIKV titers in the midguts at 7 dpi, as compared to the corresponding virus-infected WT midguts, but there was no difference in infection prevalence between the G12sAb and WT mosquitoes (Fig. 3a–c). In terms of the viral infection in carcasses (the mosquito body excluding the midgut) at 14 dpi, G12sAb mosquitoes had a significantly lower DENV-2 titer and infection prevalence (Fig. 3a) and DENV-4 titer (Fig. 3b), and there was no difference in the ZIKV titer or infection prevalence between the G12sAb and WT mosquitoes (Fig. 3c). In terms of MAYV infection, both the virus titer and infection prevalence were significantly lower in midguts at 2 dpi, as was the infection prevalence in carcasses at 7 dpi (Fig. 3d), when compared to the corresponding virus-infected WT midguts and carcasses.

Viral titer of DENV-2 (a), DENV-4 (b), ZIKV (c), and MAYV (d) in midguts and carcasses of wild-type (WT) and transgenic mosquitoes (G12sAb), as measured by plaque assay on various days post-infection (dpi). Infection prevalence and sample sizes for each virus are shown on the top panel of each graph. P values were determined by an unpaired two-sided Mann-Whitney test for virus titer or an unpaired two-sided Fisher’s exact test for infection prevalence. e IFA detection of CHIKV sdAb and MAYV in midgut cells of G12sAb mosquitoes at 2 days post-infection. Yellow arrows indicate cells with abundant small antibodies, and white arrows indicate MAYV-positive cells. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Source data are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

To determine whether the influence of small antibodies on viral infection occurs in the same midgut cells, we looked for co-localization of the CHIKV sAb and MAYV in the midguts of G12sAb mosquitoes at 2 dpi by using IFA. The results showed that CHIKV sAb-abundant cells were not infected by MAYV, and most MAYV-infected cells had less CHIKV sAb (Fig. 3e). Only a few midgut cells were positive for CHIKV sAb at 2 days after BF, as compared to 1 day post-BF, when most midgut cells were stained by antibody (Fig. 2c), consistent with the decreased level of CHIKV sAb protein and gene expression at 2 days post-BF (Fig. 2a,b,e). Altogether, our results suggest that inhibition of viral infection by small antibodies occurs through interference with viral replication in midgut cells.

In summary, small antibody-induced inhibition of orthoflaviviruses and alphaviruses is mainly seen in the midgut, and the lesser virus infection in carcasses may be a result of the virus blocking in midguts.

Co-expression of small antibodies and the siRNA pathway factor Dcr2 in the midgut inhibits arbovirus infection and enhances transmission-blocking of both orthoflaviviruses and alphaviruses

We have previously reported that overexpression of Dcr2, a ribonuclease and key component of the siRNA pathway, in Ae aegypti midguts (CpDcr2) significantly inhibits infection with multiple arboviruses23. To determine whether co-expression of G12sAb and CpDcr2 would produce a greater resistance to arboviral infection, we crossed G12sAb females with CpDcr2 males and generated a G12sAb-CpDcr2 line (named sAbDcr2) (Fig. 4a). After continuous crossing for four generations, we infected sAbDcr2, G12sAb, and LVP (WT) mosquitoes with DENV-2, CHIKV, and MAYV, and the virus titers and infection prevalences were compared between WT and transgenic mosquitoes. The results showed that sAbDcr2 and G12sAb midguts exhibited a significantly lower virus titer of DENV-2, CHIKV, and MAYV than did WT midguts, and sAbDcr2 also showed a lower MAYV titer in the midguts than did G12sAb (Fig. 4b). The DENV-2 infection prevalence in the midguts of sAbDcr2 was also significantly lower than that in the WT mosquitoes. Therefore, expression of small antibodies in conjunction with overexpression of the siRNA pathway can strengthen resistance to arbovirus infection in mosquito midguts.

a Flowchart showing generation of transgenic mosquitoes (sAbDcr2) expressing both small antibodies and Dcr2 by crossing G12sAb females and CpDcr2 males and experimental design. BF, blood-feeding; dpi, days post-infection. b Effect of co-expression of small antibodies and Dcr2 on virus infection in midguts. The virus titer was determined by plaque assay at 2 dpi for MAYV, 3 dpi for CHIKV, and 7 dpi for DENV-2, respectively. c Effect of a second BF on MAYV and DENV-2 titer in midguts of WT, G12sAb, and sAbDcr2. Mosquitoes were fed on blood-virus mix and then provided with a naïve blood meal at 4 dpi and after oviposition. At 2 days and 3 days, respectively, after a second BF, MAYV and DENV-2 titer were determined at 6 dpi and 7 dpi, respectively. Infection prevalence and sample sizes for each virus are shown on the top panel of (b) and (c). d Flowchart showing the experimental design for the viral transmission assay. Saliva was collected from a group of five females by probing in 100 µl of feeding solution (equal volumes of human serum and DMEM with a 10 mM final concentration of ATP) in an artificial feeding system. e MAYV titer and infection prevalence in feeding solution collected from 7 dpi-infected WT, G12sAb, and sAbDcr2 mosquitoes. n = 12 (WT), n = 15 (G12sAb), and n = 13 (sAbDcr2). f DENV-2 titer and infection prevalence in feeding solution collected from 14 dpi-infected WT, G12sAb and sAbDcr2 mosquitoes. n = 13. Virus titer was determined by plaque assay. P values were determined by an unpaired two-sided Mann-Whitney test for virus titer or an unpaired two-sided Fisher’s exact test for infection prevalence. Illustrations in a and d were created with BioRender.com. Source data are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Aedes mosquitoes usually feed multiple times on blood if blood sources are available. Since both the AeG12 and Dcr2-driving carboxypeptidase promoters are induced by the ingestion of a bloodmeal, we asked whether additional blood-feeding would augment virus suppression in transgenic mosquitoes. For this purpose, we infected transgenic and WT mosquitoes with various arboviruses, then provided a second naïve blood-feeding at 4 dpi and after oviposition, and measured the virus titers in the midguts and carcasses thereafter (Fig. 4a). The results showed that both the DENV-2 and MAYV titers in the midguts and carcasses of sAbDcr2 and G12sAb were significantly lower than those in the WT mosquitoes; sAbDcr2 also exhibited significantly lower DENV-2 and MAYV titers in the midguts and carcasses than did G12sAb (Fig. 4c; Supplementary Fig. 8), suggesting that additional blood meals do not affect the inhibition of virus infection in transgenic mosquitoes.

To assess the effect of the midgut expression of small antibodies and Dcr2 on orthoflavivirus and alphavirus transmission by mosquitoes, we infected sAbDcr2, G12sAb, and WT mosquitoes with DENV-2 and MAYV, and then examined salivary gland infections and the levels of virus particles released from the proboscis of a group of infected mosquitoes (5 females/group) during feeding at 7 dpi for MAYV and 14 dpi for DENV-2 (Fig. 4d). As compared to the WT mosquitoes, sAbDcr2 and G12sAb mosquitoes exhibited a significantly reduced MAYV titer and infection prevalence in salivary glands (Supplementary Fig. 9) and released a significantly lower quantity of viral particles (Fig. 4e). MAYV infection prevalence was also significantly reduced in sAbDcr2 mosquitoes, and 5 of 12 samples collected from sAbDcr2 were not infected by MAYV, whereas all of the 13 samples collected from the WT mosquitoes were infected. Transmission of DENV-2 was also significantly reduced in sAbDcr2 mosquitoes (Fig. 4f). Only 3 of 13 samples collected from sAbDcr2 mosquitoes were infected, whereas 10 of 13 samples collected from the WT mosquitoes were infected by DENV-2.

In summary, co-transgenic expression of small antibodies and the siRNA pathway factor Dcr2 that block viruses through independent mechanisms can significantly augment arbovirus suppression, resulting in a significant reduction in arbovirus transmission.

Discussion

A major advance in the development of mosquito population replacement-based disease control strategies has involved identifying effectors that efficiently reduce vector’s capacity to transmit pathogens8,21. Multiple antiviral effector genes have been engineered in Ae. aegypti to generate pathogen-resistant (refractory) mosquitoes, and these refractory mosquitoes can be classified into two groups. The first group is the virus-type-specific effectors, such as small RNAs of ZIKV26, DENV-325, and CHIKV25; inverted repeat sequence of DENV-227,28; and DENV-targeting scFv32. These effectors target one specific or several closely related viral species in the same genus, such as the genus Orthoflaviviridae. The second group of effectors has a broad spectrum of antiviral activity, and these effectors usually boost elements of mosquito antiviral immunity, such as the JAK/Stat pathway24 and the siRNA pathway23. This second group of effectors has the advantage of targeting multiple viruses in different families, but their antiviral activity may be somewhat lower than that of members of the first group. Here, we generated a transgenic mosquito line that expresses antiviral effectors (small antibodies) against both orthoflaviviruses and alphaviruses, the viruses that include the most important arboviruses from a global public health perspective, DENV and CHIKV. This dual targeting provides a significant advantage over recently developed lines that target only one of these viral groups32,33, providing a broader spectrum of antiviral protection, which is crucial for practical applications.

We have identified a blood-inducible, midgut-specific promoter that drives the expression of two endogenous G12-like gene expressions in opposite directions. The G12 promoter has a small size (1777 bp) and similar expression pattern to that of the Carboxypeptidase (Cp) promoter24,25,26,27,32, but it can concurrently drive the expression of two genes, an important attribute for expressing multiple effectors in the same mosquito. More importantly, although the G12 promoter highly stimulates the expression of both endogenous genes and transgenes, the expression of the effector genes does not affect the expression of endogenous genes with the same promoter sequence34,35,36, thus, the associated fitness cost is likely minimal. Although we observed a significant negative impact of small antibody expression on female longevity (median survival: 32 days for wild type vs. 22 days for G12sAb, p = 0.0004), this shorter lifespan could be beneficial for limiting viral spread, given that peak transmission occurs at and after 14 dpi for DENV and 7 dpi for CHIKV.

The immune systems of mosquitoes differ drastically from those of mammals. Because mosquitoes don’t produce antibodies and lack antibody-mediated immune responses to infection by pathogens37,38, the inhibition of viral infection in mosquitoes by small antibodies must employ a different mechanism. The fact that small antibodies can efficiently bind to viral proteins in vitro and in vivo18,19,29,30 suggests that small antibodies can bind to viral proteins produced by mosquito cells as well inhibit viral replication; this assertion is supported by the fact that less MAYV infection is observed in cells that have abundant CHIKV sdAb. Therefore, inhibition of viral infection by small antibodies in mosquitoes likely results from blocking the function of viral proteins, subsequently affecting virus assembly and maturation. Although the virus titer in transgenic mosquitoes is lower in midguts than that in WT mosquitoes, once viruses are disseminated into the hemocoel, there is no small antibody-mediated resistance, and virus replication proceeds unimpeded. The reduced viral titer in the midgut, however, likely influences both the timing of viral dissemination to other tissues and the quantity of viral particles escaping the midgut. These factors could subsequently affect viral infection and production in the carcass, ultimately impacting viral infection of the salivary glands and impairing virus transmission.

Orthoflavivirus such as DENV infection in mosquitoes begins in midgut epithelial cells as early as 2 dpi by IFA39, disseminating to the hemocoel by 4–7 dpi and reaching salivary glands by 10–14 dpi40, with peak midgut propagation at 2–7 dpi39,41. In contrast, alphaviruses such as CHIKV and MAYV usually infect midgut cells as early as 1 dpi, disseminate into the hemocoel by 2–4 dpi, and reach salivary glands by 4–7 dpi, with peak midgut propagation at 1–4 dpi42. The presence of DENV NS1 scFv in the midguts of G12sAb transgenic mosquitoes peaks at 12–24 h after blood-feeding, while CHIKV sdAb peaks at 24–36 h. This timing correlates better with alphavirus replication, potentially explaining the more efficient inhibition of alphaviruses compared to orthoflaviviruses.

Although large quantities of small antibodies are present in the midguts of transgenic mosquitoes, infection with either orthoflaviviruses or alphaviruses cannot be completely abolished in both midguts and salivary glands, resulting in incomplete blocking of virus transmission. Consistent with our findings, a recent study demonstrated that expression of CHIKV sdAb achieved significant reductions, but not complete inhibition, of MAYV and CHIKV infections33. This incomplete suppression may be attributable to several factors, including inefficient binding between small antibodies and viral protein in mosquitoes, the time difference between the expression of small antibodies and virus replication in the midgut, and the expression of small antibodies and infection with arboviruses in different midgut cells. In contrast, another recent study reported that the expression of DENV scFv via the Ae. aegypti carboxypeptidase promoter in mosquito midguts leads to complete refractoriness to DENV infection32.

Major concerns regarding the development of arbovirus-resistant transgenic mosquitoes are the possible emergence of virus resistance to the engineered blocking mechanism and whether the resistance level will be sufficient to mediate an epidemiologically significant impact. A way to mitigate these concerns is through the simultaneous targeting of the viruses through multiple independent virus-suppressing mechanisms which also would achieve a greater suppression than using each of the two antiviral effectors independently. While our findings indicate that expression of small antibodies alone has limitations for practical application due to a marginal effect on virus transmission, co-expression with the siRNA pathway gene Dicer-2 resulted in a significant reduction in transmission of both orthoflaviviruses and alphaviruses. Therefore, given their small size and ease of engineering, these antibodies are a valuable component of a combined transgenic approach for arbovirus control.

Field deployment of these transgenic mosquitoes could be facilitated by integrating gene-drive strategies43, utilizing male mosquitoes to disseminate the small antibody transgenes. Male mosquitoes, which do not exhibit the observed fitness cost associated with antibody expression, would remain competitive in natural environments and effectively propagate the desired trait. Future research investigating the potential for arboviral resistance development, testing inhibition against recently isolated arboviruses from endemic areas, and implementing robust gene-drive systems will be crucial for the successful release of antibody-carrying mosquito populations into the wild.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and the institutional Ethics Committee (permit number M006H300). The protocol (permit # MO15H144) was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Johns Hopkins University. BALB/c mice (6–12 weeks old) were only used for mosquito blood feeding, therefore, gender-based analysis was not relevant to the study. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. Commercial, anonymous human blood was used for virus infection assays in mosquitoes, and informed consent and ethical approval by an institutional review board were therefore not applicable.

Mosquitoes

The Liverpool IB12 (LVP) strain, Higgs’ white eye (WHE) strain, and CpDcr2 line23 of Ae. aegypti were reared and maintained at 27 °C under 85% relative humidity and a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle in the insectary of Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute. All the transgenic mosquitoes were reared under the same conditions in a walk-in chamber. Mosquito larvae were fed on TetraMin tablets, and female mosquitoes were maintained on a 10% sucrose solution and blood-fed on ketamine-anesthetized Swiss Webster mice (Charles River Laboratories) for colony maintenance.

Construction of small antibody-expressing plasmids and generation of transgenic Ae. aegypti mosquitoes

The construct containing the Ae. aegypti G12 promoter and the orthoflavivirus NS1 scFv and anti-CHIKV sdAb sequences were synthesized by GenScript and then cloned into a piggyBac-3xP3-EGFP backbone plasmid24. The plasmid was chemically transformed into E. coli DH5α cells and then purified using the Endofree Maxi Prep kit (Qiagen, Germantown, USA). The final plasmid was air-dried and re-suspended in nuclease-free water.

The piggyBac transposase mRNA was produced by in vitro-transcription (IVT). The template for the IVT was prepared by PCR from a plasmid containing the piggyBac transposase and pBac forward and reverse primers with T7 promoter sequences44. IVT was performed with a HiScribe® T7 ARCA mRNA Kit (New England Biolabs, NEB), and mRNA was purified with RNAClean XP beads (Beckman) and re-suspended in nuclease-free water.

For the germ-line transformation, the donor small antibody-expressing plasmid and piggyBac transposase mRNA were mixed with nuclease-free water to yield a final concentration of 300 ng/μL of each. The mix was then injected into the newly laid eggs of HWE mosquitoes via a FemtoJect Express (Eppendorf) and quartz needles23. The injected eggs were hatched in distilled water at 3 days post-injection, and hatched larvae (G0) were reared in distilled water and fed on TetraMin tablets. The 2nd instar larvae were screened with a fluorescent microscope and reared according to standard mosquito-rearing protocols. The surviving adults were mated to the opposite sex wild-type LVP mosquitoes, and the larvae (G1) from the G0 adults were screened for the same fluorescent eyes. The positive G1 pupae were sexed, and different pools were established. After another four generations of crossing with WT mosquitoes, the heterozygous mosquitoes were inbred for another four generations to generate homozygous lines for the downstream experiments.

Inverse PCR

To ascertain the insertion site of the transgene in the G12sAb transgenic line, genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from five adult females using a blood and tissue DNA extraction kit (Qiagen) and then eluted in 50 μl of molecular-grade water. The gDNA concentration was measured using Nanodrop II. Two μg of gDNA were incubated with Sau3AI (New England Biolabs, NEB) to digest the 5’ end and HinIII (NEB) to digest the 3’ end, respectively, for 2 h at 37 °C. The digested product was purified using a DNA clean and concentrator kit (Zymogen) and eluted in 10 μl of water. A 20 μl reaction mixture containing 10 μl of digested gDNA product was ligated using the T4 ligase (NEB) overnight at 16 °C.

The ligated products from the 5’ digestion and the 3’ digestion were amplified with their respective primers (Supplementary Table 1)32. The PCR conditions were as follows: denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; amplification for 40 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 3 min; and final extension at 68 °C for 5 min. The second round of PCR was performed on the amplified products from the 5’ and 3’ digestions with specific primers (Supplementary Table 1). The amplified products from the second round of PCR were run on an agarose gel, and the bands with a size between 2000 and 3000 bp were excised and purified using a DNA clean and concentrator kit (Zymogen). The purified DNA was sequenced by Sanger sequencing with the second-round PCR primers. The sequenced products were analyzed for transgene insertions using the BLAST tool from VectorBase by overlapping the sequences covering the 5’ and 3’ flanking regions of the transgene with the Ae. aegypti genome (AaegL5).

Assessment of larval development, adult body weight, and female blood-feeding capacity

For the larval development assay, a group of 50 G12sAb transgenic or WT (Liverpool strain) 1st instar larvae were reared in a container with TetraMin tablets according to standard mosquito rearing protocols, and the number of pupae was recorded each day to determine the larval development time. Each line had at least three biological replicates, with two technical repeats.

To measure the body weight, a group of five newly emerged males or females were transferred to a 16-oz paper cup and starved for 4 h, and then the mosquitoes were anesthetized using carbon dioxide. The weight of every five mosquitoes were measured on a fine balance (Ohaus).

To determine the blood-feeding capacity, 10 1-week-old WT and G12sAb transgenic females were transferred to a small paper cup and starved overnight, then fed on an anesthetized mouse for 20 min. The blood-fed mosquitoes in each cup that were identified as fully engorged were counted. The weight of each group of mosquitoes was determined before and after blood-feeding. The amount of blood-meal taken by each female was calculated by subtracting the weight of the group of mosquitoes before blood-feeding from the weight afterwards45.

Assessment of fecundity, egg hatchability, and longevity

For the fecundity assay, one-week-old WT and G12sAb transgenic females were fed on anesthetized Swiss Webster mice, and fully engorged mosquitoes were sorted on ice and transferred to a 32-oz paper cup. At 3 days post blood-feeding (PBF), females were individually placed for 48 h in a well of a 24-well plate with 500 μl of 2% agarose on the bottom as a wet surface for egg laying46. After egg laying, each well was photographed under a microscope equipped with a camera, and the number of eggs in each image was counted using Image J software. To measure the hatching rate, the eggs were kept in the insectary for another 3 days, and then about 1 ml of deionized water was added to each well to hatch the eggs; the plates were then sealed with parafilm to prevent water evaporation. The hatching rate was calculated by dividing the number of larvae by the number of eggs laid per female. After an additional 4 days, each well with hatched larvae was photographed again, and the hatched larvae were counted as described above.

To measure the longevity of blood-fed females, one-week-old WT and G12sAb transgenic females were fed on mice, and fully engorged females were transferred to a 16-oz paper cup. Each cup had 20 females, with four replicates for each line. Mosquitoes were monitored daily to check for mortality over the next 2 months, with dead mosquitoes removed regularly to minimize mosquito exposure to microorganisms in mosquito carcasses23. Cups were also changed every week to prevent contamination from mosquito excreta and sucrose droplets. Sucrose was replenished regularly to prevent death from dehydration. The longevity of the sugar-fed WT and G12sAb transgenic males was also measured as described above.

Virus infection in mosquitoes and titration by plaque assay

DENV serotype 2 (DENV-2; New Guinea C strain), ZIKV (Cambodia, FSS13025), MAYV (Iquitos, IQT, gifted from Dr. Alexander W.E. Franz at University of Missouri), and CHIKV (attenuated strain, 181/25, gifted from Dr. Diane Griffiths at Johns Hopkins University) were each propagated in C6/36 cells42,45. The virus-infected cell culture medium was harvested at 5 dpi for DENV-2 or ZIKV and 3 dpi for MAYV or CHIKV, then mixed with an equal volume of commercial human blood supplemented with 10% human serum containing 10 mM ATP. Approximately 60 one-week-old females of the transgenic lines or WT were transferred to a 32-oz paper cup and starved overnight, then fed for 30 min with the blood-virus mixture on a single glass artificial feeder. Fully engorged females were sorted in a cold room (4 °C), put back into a new cup, and maintained on 10% sterile sucrose solution in the insectary. The midgut and carcass were dissected from each individual female in sterile PBS on ice, transferred to an Eppendorf tube containing 300 µl DMEM and a small portion of glass beads and kept it at −80 °C. Each experiment had at least two biological replicates, and each replicate included at least 18 individual females.

Midgut and carcass samples were homogenized using a Bullet Blender (Next Advance, Inc., Averill Park, NY) at speed 3 for 3 min, and centrifuged at 7000 × g for 3 min. Supernatants were filtered with 0.22 µm syringe filters. Vero cells (for ZIKV, MAYV, or CHIKV) or BHK 21 cells (for DENV-2 and DENV-4) were seeded into 24-well plates and grown to >80% confluence. Cells were infected with either 50 μl (for midgut samples) or 20 μl (for carcass samples) of 10-fold serial dilutions of filtered supernatants. The virus-infected plates were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 3 days for MAYV and CHIKV, 4 days for ZIKV, and 5 days for DENV-2. Viral plaques were visualized using 1% crystal violet staining and counted under a microscope.

Virus transmission assays

Viral transmission in mosquitoes was assayed using an artificial glass feeder45. In brief, six transgenic or wild-type females at 7 dpi with MAYV or 14 dpi with DENV-2 were transferred to a 16-oz paper cup, starved for 6 h, and then fed using a sterilized glass feeder containing 200 μl of feeding solution (equal volumes of human serum and DMEM with a 10 mM final concentration of ATP) for 30 min. After feeding, the solution from each feeder was collected into a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube, immediately placed on dry ice, and stored at −80 °C until further analysis. Viral titer in the feeding solution was determined using plaque assay, as described above. Each experiment had two biological replicates, with each replicate consisting of at least six samples each line.

RT-qPCR

Midguts were dissected from transgenic and wild-type mosquitoes in sterile PBS on ice, with each sample consisting of 10 midguts. Samples were homogenized in 300 μl TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and total RNA was extracted according to the standard protocol. First-strand cDNA was synthesized by using 0.5 μg total RNA of each sample with a QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was conducted using gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table 1) and ABI SYBR Green Supermix using the StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK)45. The final reaction volume of qPCR was 20 μl, and the PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. The specificity of the amplified products was verified by melting curve analysis at the end of each run. The relative abundance of the gene transcripts was normalized and calculated by comparison to the ribosomal protein S7 gene using the comparative 2−ΔΔCT or 2−ΔCT method. Each sample had at least three independent biological replicates.

Western blot and immunofluorescence assays (IFA)

Midguts and carcasses were dissected from transgenic and WT mosquitoes in PBS on ice, and each sample had 15 midguts or 6 carcasses. The samples were homogenized in PBS containing proteinase cocktail (Roche) and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were boiled for 5 min with 2x Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) and loaded onto a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using a Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS: 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) for 1 h, and then incubated with anti-V5 (Invitrogen, cat#: R960-25; 1:2,000 dilution) or anti-HA monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen, cat#: 26183; 1:10,000 dilution) overnight at 4 °C. After four washes with TBST (TBS with 0.1% Tween 20), the membrane was incubated with anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Cell Signaling Technology) in 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature. Chemiluminescent signals were detected by using Amersham ECL Prime Western blotting detection reagents and exposed to an X-ray film. Anti-β-actin-peroxidase antibody (Sigma, cat#: A5316; 1:100,000 dilution) was used as a loading control. The protein sizes on the X-ray film were estimated by aligning the bands with the Precision Plus Protein™ Standards, Dual Color (Bio-Rad, Cat# 161-0374) visualized on the transferred membrane.

For IFA, midguts were dissected from G12sAb females 1 day post naive blood-feeding or 2 days post MAYV infection. Midgut samples were fixed in a PCR tube containing 100 μl of 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) overnight at 4 °C. After fixation, the samples were permeabilized with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBT). To detect MAYV infection, midgut samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-MAYV E2 antibody (Sigma, cat#: MABF3046; 1:2000 dilution) after three washes with PBST (PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100), and then incubated with the secondary antibody, AlexaFluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) in PBT for 2 h at 37 °C in the dark. To detect expression of small antibodies, midgut samples were incubated with V5-tagged monoclonal antibody Alexa FluorTM 555 (Invitrogen, cat#: 37-7500-A555; 1:200 dilution), V5 Tag Monoclonal Antibody DyLight™ 488 (Invitrogen, cat#: MA5-15253-D488; 1:100 dilution), or HA-tagged monoclonal antibody Alexa FluorTM 647 (Invitrogen, cat#: 26183-A647; 1: 200 dilution) in PBT for 2 h at 37 °C in the dark. DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) was added to each sample to stain the nuclei. Samples were viewed and photographed under a Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Microscope Facility or Leica STELLARIS 8 FALCON at the Microscopy Core of the Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Statistics and reproducibility

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 10. Differences in the virus titer, fecundity, and hatching rate between transgenic and wild-type mosquitoes were assessed by an unpaired two-sided Mann–Whitney test and infection prevalence by a two-sided Fisher’s exact test. P values for differences in larval development and survival rate between transgenic and wild-type mosquitoes were determined by a Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test and a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test, respectively. The significance of the differences in gene expression was determined by one-way ANOVA. Student’s t-test was used for the determination of the significance of differences in body weight and blood-feeding capability.

Sample sizes and the number of biological replicates for each experiment are indicated in the corresponding figure legends. Specifically, to enhance data reproducibility, virus infection assays in mosquito midguts and carcasses were conducted with 2–3 biological replicates, each containing 10–24 samples. For the virus transmission assay, two biological replicates were performed, with 6–8 samples per replicate.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All source data for all graphs and figures in the paper can be found in the Supplementary Data 1. All other data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Complete sequence maps and plasmids and Ae. aegypti transgenic lines generated in this study are available upon request to G.D.

References

Schmaljohn, A. L. & McClain, D. in Medical Microbiology (ed Baron, S.) (1996).

Ryan, S. J., Carlson, C. J., Mordecai, E. A. & Johnson, L. R. Global expansion and redistribution of Aedes-borne virus transmission risk with climate change. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 13, e0007213 (2019).

Ebi, K. L. & Nealon, J. Dengue in a changing climate. Environ. Res 151, 115–123 (2016).

Bhatt, S. et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496, 504–507 (2013).

Colon-Gonzalez, F. J. et al. Projecting the risk of mosquito-borne diseases in a warmer and more populated world: a multi-model, multi-scenario intercomparison modelling study. Lancet Planet Health 5, e404–e414 (2021).

Dusfour, I. et al. Management of insecticide resistance in the major Aedes vectors of arboviruses: Advances and challenges. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 13, e0007615 (2019).

Vontas, J. et al. Insecticide resistance in the major dengue vectors Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 104, 126–131 (2012).

Wang, G. H. et al. Combating mosquito-borne diseases using genetic control technologies. Nat. Commun. 12, 4388 (2021).

Caragata, E. P. et al. Prospects and Pitfalls: Next-Generation Tools to Control Mosquito-Transmitted Disease. Annu Rev. Microbiol 74, 455–475 (2020).

Fishburn, A. T., Pham, O. H., Kenaston, M. W., Beesabathuni, N. S. & Shah, P. S. Let’s get physical: flavivirus-host protein-protein interactions in replication and pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 13, 847588 (2022).

Li, Q. & Kang, C. Structures and dynamics of dengue virus nonstructural membrane proteins. Membranes. 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes12020231 (2022).

Tomar, S. & Aggarwal, M. Structure and function of proteases. Viral Proteases Their Inhib. 105–135 (2017).

Rupp, J. C., Sokoloski, K. J., Gebhart, N. N. & Hardy, R. W. Alphavirus RNA synthesis and non-structural protein functions. J. Gen. Virol. 96, 2483–2500 (2015).

Kim, A. S. & Diamond, M. S. A molecular understanding of alphavirus entry and antibody protection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 396–407 (2023).

Torres-Ruesta, A., Chee, R. S. L. & Ng, L. F. P. Insights into antibody-mediated alphavirus immunity and vaccine development landscape. Microorganisms 9, ARTN 899 https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9050899 (2021).

Dowd, K. A. & Pierson, T. C. Antibody-mediated neutralization of flaviviruses: a reductionist view. Virology 411, 306–315 (2011).

Pierson, T. C., Fremont, D. H., Kuhn, R. J. & Diamond, M. S. Structural insights into the mechanisms of antibody-mediated neutralization of flavivirus infection: Implications for vaccine development. Cell Host Microbe 4, 229–238 (2008).

Beatty, P. R. et al. Dengue virus NS1 triggers endothelial permeability and vascular leak that is prevented by NS1 vaccination. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 304ra141 (2015).

Liu, J. L. et al. Stabilization of a broadly neutralizing anti-chikungunya virus single domain antibody. Front. Med. 8, 626028 (2021).

Smith, S. A. et al. The potent and broadly neutralizing human dengue virus-specific monoclonal antibody 1C19 reveals a unique cross-reactive epitope on the bc loop of domain II of the envelope protein. mBio 4, e00873–00813 (2013).

Alphey, L. et al. Genetic control of Aedes mosquitoes. Pathog. Glob. Health 107, 170–179 (2013).

Dong, S., Dong, Y., Simoes, M. L. & Dimopoulos, G. Mosquito transgenesis for malaria control. Trends Parasitol. 38, 54–66 (2022).

Dong, Y. et al. The Aedes aegypti siRNA pathway mediates broad-spectrum defense against human pathogenic viruses and modulates antibacterial and antifungal defenses. PLoS Biol. 20, e3001668 (2022).

Jupatanakul, N. et al. Engineered Aedes aegypti JAK/STAT pathway-mediated immunity to dengue virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11, e0005187 (2017).

Yen, P. S., James, A., Li, J. C., Chen, C. H. & Failloux, A. B. Synthetic miRNAs induce dual arboviral-resistance phenotypes in the vector mosquito Aedes aegypti. Commun. Biol. 1, 11 (2018).

Buchman, A. et al. Engineered resistance to Zika virus in transgenic Aedes aegypti expressing a polycistronic cluster of synthetic small RNAs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 3656–3661 (2019).

Franz, A. W. et al. Engineering RNA interference-based resistance to dengue virus type 2 in genetically modified Aedes aegypti. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 4198–4203 (2006).

Mathur, G. et al. Transgene-mediated suppression of dengue viruses in the salivary glands of the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Insect Mol. Biol. 19, 753–763 (2010).

Biering, S. B. et al. Structural basis for antibody inhibition of flavivirus NS1-triggered endothelial dysfunction. Science 371, 194–200 (2021).

Liu, J. L., Shriver-Lake, L. C., Zabetakis, D., Anderson, G. P. & Goldman, E. R. Selection and characterization of protective anti-chikungunya virus single domain antibodies. Mol. Immunol. 105, 190–197 (2019).

Bonizzoni, M. et al. RNA-seq analyses of blood-induced changes in gene expression in the mosquito vector species, Aedes aegypti. BMC Genomics 12, 82 (2011).

Buchman, A. et al. Broad dengue neutralization in mosquitoes expressing an engineered antibody. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008103 (2020).

Webb, E. M. et al. Expression of anti-chikungunya single-domain antibodies in transgenic Aedes aegypti reduces vector competence for chikungunya virus and Mayaro virus. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1189176 (2023).

Pinkerton, A. C., Michel, K., O’Brochta, D. A. & Atkinson, P. W. Green fluorescent protein as a genetic marker in transgenic. Insect Mol. Biol. 9, 1–10 (2000).

Anderson, M. A. E., Gross, T. L., Myles, K. M. & Adelman, Z. N. Validation of novel promoter sequences derived from two endogenous ubiquitin genes in transgenic. Insect Mol. Biol. 19, 441–449 (2010).

Carpenetti, T. L. G., Aryan, A., Myles, K. M. & Adelman, Z. N. Robust heat-inducible gene expression by two endogenous hsp70-derived promoters in transgenic Aedes aegypti. Insect Mol. Biol. 21, 97–106 (2012).

Lee, W. S., Webster, J. A., Madzokere, E. T., Stephenson, E. B. & Herrero, L. J. Mosquito antiviral defense mechanisms: a delicate balance between innate immunity and persistent viral infection. Parasit. Vectors 12, 165 (2019).

Cheng, G., Liu, Y., Wang, P. & Xiao, X. Mosquito defense strategies against viral infection. Trends Parasitol. 32, 177–186 (2016).

Salazar, M. I., Richardson, J. H., Sanchez-Vargas, I., Olson, K. E. & Beaty, B. J. Dengue virus type 2: replication and tropisms in orally infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. BMC Microbiol 7, 9 (2007).

Abduljalil, J. M. & Abd Al Galil, F. M. Molecular pathogenesis of dengue virus infection in Aedes mosquitoes. J. Insect Physiol. 138, 104367 (2022).

Raquin, V. & Lambrechts, L. Dengue virus replicates and accumulates in Aedes aegypti salivary glands. Virology 507, 75–81 (2017).

Dong, S. et al. Infection pattern and transmission potential of chikungunya virus in two New World laboratory-adapted Aedes aegypti strains. Sci. Rep. 6, 24729 (2016).

Williams, A. E., Franz, A. W. E., Reid, W. R. & Olson, K. E. Antiviral effectors and gene drive strategies for mosquito population suppression or replacement to mitigate arbovirus transmission by Aedes aegypti. Insects 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11010052 (2020).

Hacker, I. et al. Improved piggyBac transformation with capped transposase mRNA in pest insects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242015155 (2023).

Dong, S. & Dimopoulos, G. Aedes aegypti Argonaute 2 controls arbovirus infection and host mortality. Nat. Commun. 14, 5773 (2023).

Tsujimoto, H. & Adelman, Z. N. Improved fecundity and fertility assay for Aedes aegypti using 24 well tissue culture plates (EAgaL Plates). J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/61232 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health / National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease R01AI141532 and the Bloomberg Philanthropies. The founders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We thank the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute Insectary for providing the mosquito-rearing facility and the Parasitology Core facilities for providing the naive human blood. We thank Dr. Deborah McClellan for editorial assistance. We thank the Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology Microscopy Facility at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health for use of their instruments, including the Leica STELLARIS 8 FALCON confocal microscope (supported by NIH Grant 1S10OD036404-01). The illustrations in the figures were created with BioRender.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D. and G.D. conceived and designed the experiments. S.D., M.T., and Q.D. performed the experiments. S.D. and G.D. analyzed the data, and S.D., M.T., and G.D. wrote the paper, with input from all authors. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: David Favero.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, S., Tavadia, M., Dong, Q.A. et al. Engineered antibody-mediated broad-spectrum suppression of human arboviruses in the Aedes aegypti vector. Commun Biol 8, 709 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08133-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08133-5