Abstract

Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68), a member of the Picornaviridae family, causes respiratory illness and can lead to acute flaccid myelitis in children. No specific treatment or vaccine is available. Here, we determine cryo-EM structures of EV-D68 virus-like particles (VLPs), inactivated virus particles (InVPs), and altered virus particles (A-particles) from B3 and A2 subclades. The B3 VLP is a current vaccine candidate, which we show closely resembles its InVP counterpart, particularly at the 5-fold axis of symmetry, the target of potent neutralizing antibodies. Similar structural conservation was observed in the A2 subclade. Sequence variation between B3 and A2 mainly occurred in flexible loops displayed on the particle surface. A canyon-filling pocket factor was present in B3 InVP but absent in A2 InVP. A-particles were predominant in β-propiolactone-inactivated virus at longer but not shorter incubation. Overall, our findings highlight EV-D68 similarities and subclade-specific differences, offering structural insights that relate to vaccine development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) belongs to the Picornaviridae family and the genus Enterovirus with infectious particles comprising a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome packaged into a non-enveloped icosahedral capsid. The enterovirus genus includes medically important human pathogens such as enteroviruses (EV), polioviruses (PV), rhinoviruses (HRV), and coxsackieviruses (CV). While EV-D68 primarily causes childhood respiratory infections, it has also been linked to neurological disease1,2,3. EV-D68 is classified into three clades—A, B, and C, and multiple clades can circulate simultaneously during outbreaks. For instance, during the large outbreaks in 2014, a novel B1 subclade occurred in the background of existing A and B subclade circulation4,5. Since the 2014 outbreak, EV-D68 has further evolved, including a novel B3 subclade that emerged in China in 2014 and then became the dominant disease-causing virus in 2016 and 20186,7. This has led to speculation that the increased prevalence of EV-D68 relates to mutations that altered its antigenicity. This change in antigenicity could sidestep antiviral immunity, leading to increased EV-D68 infection rates. B3 and A2 are the currently circulating clades. The capsid sequence identities in different clades are over 90% identical, with most amino acid differences found in variable antigenic loops8.

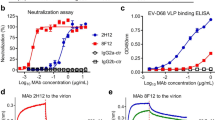

The virions of enteroviruses are icosahedral and approximately 27–32 nm in diameter. The capsid consists of 60 copies of four viral proteins: VP1-VP4. VP1, VP2, and VP3 form the outer surface of the capsid, and VP4 is located along the inner capsid surface. The virus particle is arranged in a pseudo T = 3 arrangement containing fivefold axes, threefold axes, twofold axes, and quasi-threefold axes, where T represents the triangulation number4,9. Nearby the central symmetry axis (fivefold axis), a recessed “canyon” is considered important for receptor binding10,11,12. A host-derived lipid-like “pocket factor” contributes to particle stability, and is encased at the base of canyon in the VP1 subunit13,14,15. Phylogenetic analysis suggests that variations in the epitopes of the VP1 BC loop, DE loop, C-terminus, and VP2 EF loop play a crucial role in the evolutionary divergence of EV-D68 subclades, which may lead to changes in viral tropism or escape from population-level immunity8,16. A recent study of EV-D68 monoclonal antibodies from infected humans discovered antibodies that bound to distinct areas on the virion that had differing capability to bind to and neutralize various EV-D68 subclade viruses17. The determination of the binding sites for the potently neutralizing monoclonal antibodies further defines critical regions of the virion that are sites of vulnerability. For example, the most potent antibody, mAb EVD-228, binds to the 5-fold axis of the viral particle and interacts with surface structures on three of the viral capsid proteins, including the VP1 DE loop and the VP2 EF loop near the canyon17.

The entry process for EV-D68 is thought to begin by virus binding to receptors (possibly sialic acid or heparin sulfate) on the surface of host cells, and the bona fide receptor for EV-D68 has been recently identified as MFSD61,4,5,13,18,19,20. After attachment, the pocket factor is thought to be released, and the virion internalized in the cytoplasm via receptor-mediated endocytosis. The ensuing endosomal vesicle containing the virion is acidified, causing capsid destabilization and conformational changes into an altered virus particle (A-particle), in which the VP1 N-terminus is externalized and VP4 is released from the A-particle and forms hexameric membrane pores to facilitate viral RNA release from the capsid into the cytoplasm. Upon release, the viral RNA is translated by host cell machinery to synthesize the viral polyprotein, which is cleaved by viral proteases into individual viral proteins, including structural proteins (VP1, VP0, and VP3) and non-structural proteins (2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D). The capsid proteins assemble into an immature virus procapsid. Procapsids that contain viral RNA undergo a maturation event that results in the proteolytic cleavage of VP0 into VP2 and VP4, which is myristoylated and lines the interior of the mature virion4.

Currently there are no licensed EV-D68 vaccines, although several under preclinical development use a traditional approach of inactivated virus particles to elicit neutralizing responses21,22,23. Several studies24,25 have demonstrated that virus-like particles (VLPs) are sufficient to effectively elicit cross-clade neutralizing antibodies that inhibit infection and block dissemination. Enterovirus VLPs, indistinguishable from immature virus procapsids, are composed of structural proteins that self-assemble into particles resembling viruses but are non-infectious since they lack the viral genome. VLP vaccines have been developed for various viruses, including human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis E virus (HEV), rotavirus (RV), Norwalk virus (Norovirus), and influenza A virus26,27,28. These vaccines have demonstrated safety, efficient production, and high effectiveness in preventing viral infections and associated diseases. Studying VLP structures provides critical information for understanding viral assembly and immune responses and for designing effective vaccines and antiviral strategies.

Several structural studies on EV-D68 have been conducted using live virus, including the prototype Fermon strain14 and B1 viruses from the 2014 outbreaks17,29,30. Currently, there are two co-circulating EV-D68 subclades, B3 and A2, with distinct capsid differences in immunologically dominant epitopes, suggesting that potential vaccines must elicit subclade cross-protection4,31. Despite the immunological similarities between inactivated virus and virus-like particles, structural details are needed to define similarities/differences between VLP candidate vaccine antigens and the structural state of the vaccine immunogen. To address this important vaccine issue, we determined the cryo-EM structures of β-propiolactone inactivated B3 and A2 virus particles along with their VLP counterparts.

Results

Cryo-EM structure of EV-D68 candidate vaccine from the B3 subclade

The predominant circulating EV-D68 subclade is B3 (Fig. 1a), and a B3 subclade vaccine is therefore desired32,33. A B3 VLP has recently been evaluated preclinically as an EV-D68 vaccine candidate24, which was produced by transfecting mammalian Expi293 cells with plasmids expressing the P1 polyprotein (VP4, VP2, VP3, and VP1) and 3CD protease from EV-D68 US/2018-23209 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The cryo-EM structure of B3 VLP was determined at 2.42-Å resolution using 72,000 particles and icosahedral averaging (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2, and Table 1). As expected, 3CD did not mediate cleavage between VP4 and VP2, and the VLP did not contain viral RNA. The VLP resembled the viral procapsid, consisting of 60 copies of VP0, VP1 and VP3 with pseudo T = 3 icosahedral symmetry (Fig. 1b). The fivefold axis was formed by VP1, while the twofold and threefold axes were formed by VP0-VP3 dimers, and the quasi-threefold axis comprised a VP0, VP1, and VP3 asymmetric unit (Fig. 1c). The B3 VLP was porous at the twofold axes, with a radius ranging from 116-168 Å and an average diameter of ~284 Å (Fig. 1d).

a EV-D68 phylogeny tree shows a prevalence of B3 and A2 subclades (https://nextstrain.org/enterovirus/d68/genome?c=clade_membership). b Surface-rendered representation showing the overall structure of EV-D68 B3 VLP. The VP0, VP1, and VP3 are colored red, forest green, and blue, respectively. c Outlined icosahedral asymmetric unit of EV-D68 B3 VLP, showing the icosahedral symmetry axes (i2, i3, and i5) and quasi-symmetry axis (q3). d B3 VLP density maps are colored by radius from the particle center. The color key shows the radius range from 116 Å to 168 Å, with the particle mean diameter of 284 Å.

EV-D68 B3 VLP is structurally similar to inactivated virus particles

Inactivated virus particles (InVPs) have been traditionally used as enterovirus vaccines, and VLPs have been recently evaluated as a vaccine candidate for EV-D68. To gain insights into the structural similarities and differences between B3 subclade VLP and InVP, we also determined the cryo-EM structure of the InVP from EV-D68 B3 subclade.

B3 InVP was purified by ultracentrifugation and inactivated using β-propiolactone as described in the methods. Lysates of US/MO/2018-23087-infected A549 cell culture were purified by two ultracentrifugation steps (Materials and Methods). Cryo-EM analysis of B3 InVP revealed 85% partially opened A-particles and 4% fully closed inactivated virus particles, and their structures were determined at 2.86-Å resolution using 37,000 particles and at 2.73-Å resolution using 1700 particles, respectively (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3, and Table 1). The dominance of A-particles in the preparation was unexpected and may be indicative of a pH decrease during the inactivation process with β-propiolactone29. EV-D68 InVPs shared a similar subunit organization with VLPs, but the final cleavage of VP0 during maturation resulted in 60 copies of VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4 with pseudo T = 3 icosahedral symmetry (Fig. 2a). Mature InVPs also had fivefold, twofold, threefold, and quasi-threefold axes (Fig. 2b) with a radius ranging from 100–155 Å and a mean diameter of approximately 255 Å (Fig. 2c), which was smaller than the VLP (~284 Å in mean diameter). Compared to VLPs, mature InVPs adopted a more compact conformation, likely due to the presence of encapsulated RNA within the particle. VP4 (residues N28-V58) was resolved on the inner surface of the InVP, where it may interact with the encapsulated RNA. In contrast, VP4 residues were not observed in the empty VLP, where VP0 remained in its immature, uncleaved state, or in the A-particle, from which VP4 had been expelled (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 4a).

a Surface-rendered representation showing the overall structure of EV-D68 B3 InVP. The VP1, VP2, and VP3 are forest green, orange red, and blue, respectively. b Outlined icosahedral asymmetric unit of EV-D68 B3 InVP, showing the icosahedral symmetry axes (i2, i3, and i5) and quasi-symmetry axis (q3). c B3 InVP density maps are colored by radius to particle center. The color key shows the radius range from 100 Å to 155 Å. The particle mean diameter is 255 Å. d Alignment of icosahedral asymmetric unit. B3 VLP is colored in gray. VP4 was present in B3 InVP but not captured in B3 VLP. e Alignment with B3 InVP and VLP VP1 domain. RMSD is calculated based on the C-alpha atom pairs after alignment. f B3 InVP and VLP VP1 alignment at fivefold axis. Black dashed box highlights the DE loop different organization in B3 InVP and VLP. g Alignment with B3 InVP and VLP VP2-VP3 domain. h B3 VLP and InVP VP0 and VP3 alignment at threefold axis. Black dashed box highlights the similar HI loop organization in B3 InVP and VLP.

Alignment of the B3 InVP and VLP VP1 subunits at the fivefold axis showed a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) around 1.0 Å (Fig. 2e). The DE loop occupied the center of fivefold axis of the VLP but the fivefold axis was more opened in the InVP (Fig. 2f). Alignment of the B3 InVP and VLP VP2-VP3 dimer at the threefold axis resulted in an RMSD around 0.7 Å (Fig. 2g). Three VP2-VP3 dimers, assembled at the threefold axis, and the HI loop at the center were nearly identical in the B3 InVP and VLP (Fig. 2h).

Structural differences between EV-D68 B3 InVP and VLP

The flexible regions in the B3 VLP, including the VP0 N-terminus, the VP0 C-terminus, and the VP1 C-terminus, are thought to be immunogenic sites targeted by neutralizing antibodies17,30,34. To validate the structural characteristics of these flexible regions, several structural comparisons were performed among subunits. VP3 was used to align the InVP and VLP, as it yielded the minimal RMSD (Fig. 3a). The RMSD between structures was calculated based on the alignment of equivalent Cα atoms, and several flexible regions in the B3 VLP are summarized in Fig. 3b. For internal regions, partial VP4 (a.a 28–58), VP1 (a.a 1–53), VP2 N-β-hairpin (a.a 11–28), VP2 BC loop (a.a 40–60), and VP2 C-terminus (a.a 241–246) were visible in the InVP, but not captured in the VLP structure (Fig. 3b). VP4 plays a crucial role in the infection process by aiding in the attachment and entry of the virus into host cells1. The whole VP4 and N-terminal of VP2 (a.a 1–28), which belong to the VP0 region, were not captured in VLP (Fig. 3c). For surface regions, VP1 C-terminus (a.a 269–295) and VP3 GH loop (a.a 180–187) were well-ordered in InVP capsid surface regions but not observed in VLP (Fig. 3d). These data were consistent with greater flexibility in the variable antigenic loops in the VLP than in the inactivated virus.

a Superimposition of EV-D68 B3 InVP and B3 VLP showing the detailed conformational difference. b Summary of EV-D68 B3 VLP structural flexible regions. c Temperature map showing the B3 InVP inner conformational changes between B3 InVP and B3 VLP. B3 InVP is colored by RMSD between two samples. RMSD is calculated based on the C-alpha atom pairs after alignment using VP3 as the reference. Color bar is labeled. Regions highlighted in green represent the flexible parts in B3 VLP. d Similar to c, showing the conformational changes from the B3 InVP surface view.

EV-D68 A2 VLP and InVP are also structurally similar

The other currently circulating EV-D68 subclade is A2 (Fig. 1). To gain insights into the structural similarities and differences between B3 and A2 subclades, we determined cryo-EM structures of the VLP and InVP from EV-D68 A2 clade for direct comparison.

A2 VLP was made by transfecting mammalian Expi293 cells with plasmids expressing the capsid (VP4, VP2, VP3, and VP1) and 3CD protease from EV-D68 US/KY/2014-18953 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The cryo-EM structure of the A2 VLP was determined at 2.43-Å resolution using 37,000 particles (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Table 1) The A2 VLP composition and global structural characteristics are similar to the B3 VLP (Fig. 4a), with VP1 forming the fivefold axis, twofold, and threefold axes formed by VP0-VP3 dimer, and quasi-threefold axis formed by VP0, VP1, and VP3 asymmetric unit (Fig. 4b). The A2 VLP particle radius ranged from 116-168 Å with an average diameter of ~284 Å (Fig. 4c).

a Surface-rendered representation showing the overall structure of EV-D68 A2 VLP. The VP0, VP1, and VP3 are colored magenta, gold, and cyan, respectively. b Outlined icosahedral asymmetric unit of EV-D68 B3 VLP, showing the icosahedral symmetry axes (i2, i3, and i5) and quasi-symmetry axis (q3). c A2 VLP density maps are colored by radius from the particle center. The color key shows the radius range from 116 Å to 168 Å. The A2 VLP particle diameter is 284 Å. d Surface-rendered representation showing the overall structure of EV-D68 A2 InVP. The VP1, VP2, and VP3 are hot pink, gold, and cyan, respectively. e Outlined icosahedral asymmetric unit of EV-D68 A2 InVP, showing the icosahedral symmetry axes (i2, i3, and i5) and quasi-symmetry axis (q3). f A2 InVP density maps are colored by radius to the particle center. The color key shows the radius range from 100 Å to 155 Å. The A2 InVP particle diameter is 255 Å. g Alignment of icosahedral asymmetric unit. A2 InVP is colored in gray. VP4 is present in A2 InVP but not captured in A2 VLP. h Alignment with A2 InVP and VLP VP1 domain. VLP is colored in gray. RMSD is calculated based on the C-alpha atom pairs after alignment. i A2 InVP and VLP VP1 alignment at fivefold axis. VLP is colored in gray. Black dashed box highlights the DE loop different organizations in A2 InVP and VLP. j Alignment with A2 InVP and VLP VP2-VP3 domain. VLP is colored in gray. k A2 VLP and InVP VP0 and VP3 alignment at threefold axis. A2 InVP is colored in gray. Black dashed box highlights the similar HI loop organization in A2 VLP and InVP.

Based on the prevalence of A-particles in the B3 inactivated virus preparation, we shortened the second-round inactivation with β-propiolactone for A2 InVP to only 90 min (compared to 20 h for B3 second-round inactivation). The result was an A2 InVP preparation comprised of 86% fully closed inactivated mature virus particles and 7% expanded A-particles (Supplementary Fig. 3), which were determined at 2.64-Å resolution using 10,000 particles and at 3.96-Å resolution using 859 particles, respectively (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 3 and Table 1). The mature EV-D68 A2 InVP showed similar subunit organization to the A2 VLP (Fig. 4d) including fivefold, twofold, threefold, and quasi-threefold axes (Fig. 4e). The A2 InVP particle radius ranged from 100–155 Å with an average diameter of ~255 Å (Fig. 4f). Again, VP4 (a.a N28-V58) was resolved in the A2 InVP but not in the VLP (Fig. 4g). As seen in our comparisons of the B3 structures, alignment of the A2 InVP and the VLP VP1 monomer at the fivefold axis showed an RMSD of around 1.0 Å (Fig. 4h), and the DE loop in the center of the pentamer was closed in VLP but open in InVP (Fig. 4i). Alignment of A2 InVP and VLP VP2-VP3 dimer at threefold axis showed the RMSD of around 0.7 Å (Fig. 4j). Triple VP2-VP3 dimers assembled at the threefold axis. The HI loop in the center of the threefold axis exhibited the same organization in the A2 InVP (Fig. 4k).

Subclade comparisons of EV-D68 VLP/procapsid and InVP/mature virion

The two vaccine candidates, VLP and InVP, were structurally similar to the viral procapsid and mature virion, respectively. To gain insights into the structural similarities among different maturation states, we compared the cryo-EM structures of B3 and A2 VLP, InVP, and A-particle with previously published EV-D68 B1 subclade procapsid, mature virion, and A-particle structures30. The pores around the twofold axis were similar between the B1 subclade procapsid (about 17 × 33 Å) and the B3 subclade VLP (about 14 × 36 Å) (Fig. 5a–c), measuring from the Cα of VP0 Gln94 and Cα of VP3 Pro141. These pores may serve as sites for genomic RNA trafficking, partly because a single-stranded RNA, assuming no secondary structures, had a cross-section of slightly less than 8 × 10 Å29. There was no internal density in the VLP or procapsid structures as shown in the central sections (Fig. 5d–f). B3 and A2 subclade InVP structures had a similar subunit organization as the mature B1 subclade virion. The pores around the twofold axis were fully closed on mature virion (with a size of about 8 × 36 Å) and InVP (with a size of about 7 × 34 Å) (Fig. 5g–i) and with central density representing the encapsidated genomic RNA (Fig. 5j–l). As anticipated, B3 and A2 subclade A-particle exhibited a high degree of structural similarity to the B1 subclade A-particle. Partially opened pores around the twofold axis were observed on the B1 A-particle (with a size of about 14 × 35 Å), the B3 A-particle (with a size of about 11 × 33 Å) and the A2 A-particle (with a size of about 11 × 33 Å) (Supplementary Fig. 4c–e). These structural similarities—particularly in the pores around the twofold axis and in the central section composition—could be related to the observed cross-clade protection against infection with enterovirus B1, B3, and A2 subclades, as demonstrated by B3 VLP vaccination of non-human primates24.

a–c Zoomed-in view of the icosahedral twofold axis of corresponding maps. Distances are measured by the C-α of VP0 Gln94 and the C-alpha atom of VP3 Pro141. d–f Central sections of the corresponding maps. The inside densities are absent in B1 procapsid (d), B3 VLP (e), and A2 VLP (f). g–i Zoomed-in view of the icosahedral twofold axis of corresponding maps. Distances are measured by the C-alpha atom of VP2 Gln94 and C-α of VP3 Pro141. j–l Central sections of the corresponding maps. The densities of encapsidated genomic RNA are present in B1 mature virion (j), B3 InVP (k), and A2 InVP (l).

Additionally, encapsidated genomic RNA was present in B1, B3, and A2 A-particles as shown in central sections (Supplementary Fig. 4f–h). Unlike B3 and A2 A-particles following β-propiolactone inactivation, B1 A-particles were induced by ICAM-5 triggering30. The encapsidated genomic RNA appeared better preserved in B1 A-particle than in B3 and A2 A-particles (Supplementary Fig. 4f–h).

In many enterovirus structures, a hydrophobic pocket within the VP1 canyon accommodates a fatty acid-like molecule (the “pocket factor”) that regulates viral stability35,36,37. In both the B1 virus particle and B3 InVP, a limited density of pocket factor was observed in the VP1 hydrophobic pocket. However, in A2 InVP, no detectable pocket factor density was present (Fig. 6a). An overlay of the VP1 GH loop revealed that the side chain of I216 in A2 InVP is oriented towards the pocket factor’s position, potentially causing a steric clash with the pocket factor observed in B1 virus particle and B3 InVP (Fig. 6b). While we cannot rule out the possibility that A2 subclade virus bound the pocket factor in vivo, or that the factor was lost during the purification or inactivation procedures, this difference appeared to be linked with the potential steric hindrance by I216 in A2 InVP, preventing pocket factor binding.

a Cryo-EM density of pocket factor shown in B1 virus particle and B3 InVP, but absent from A2 InVP. Overlay of the local pocket factor density map in B1 virus particle, B3 InVP, and A2 InVP. Red dashed box highlights the pocket factor density. b VP1 GH loop is shown in both the model and cryo-EM map. Pocket factor density and surrounding amino acids are presented. In B1 virus particle and B3 InVP, the pocket factor densities are indicated by the black arrow. The side chain of I217 was close to the pocket factor. For A2 InVP, I216 occupied similar position as I217 in B1 virus particle and B3 InVP. Pocket factor density was not observed. Red dashed box highlights the overlay of pocket factor density and I216 (A2 InVP) and I217 (B1 virus particle and B3 InVP) in the VP1 GH loop model.

Sequence variations between EV-D68 circulating B3 and A2 subclades

EV-D68 is known to exhibit genetic diversity, with different strains or subclades circulating over time. The classification of EV-D68 into clades is based on the sequencing of viral isolates, enabling the tracking of viral evolution and spread. B3 is the dominant subclade, with A2 having lower penetrance in the population. B3 and A2 subclade capsids differ in sequence in several antigenic regions spread between all subunits.

Several major antigenic loops, including VP1 BC loop, VP1 DE loop, VP1 C-terminus, and VP2 EF loop, have multiple variations. These loops have been localized into four distinct classical picornavirus neutralizing immunogenic sites (NIms) (NIm-IA, NIm-IB, NIm-II, and NIm-III)11. VP1 BC loop harbors the NIm-IA. Variations D78N, T83E, and Q85R are in the VP1 BC loop, which surround the fivefold axis. VP1 DE loop is around NIm-IB. Variations N128G, N133S, and V136M are in the VP1 DE loop, which are all on the particle surface around the fivefold axis. VP1 DE loop is partially closed in VLP but forms an open pore in InVP (Figs. 2f and 4i). VP1 C-terminus is around NIm-III. Variations S285E and N293D are in the VP1 C-terminus, which cross over VP3 and belong to the flexible region in VLP. VP2 EF loop belongs to NIm-II. Variation A151E is in VP2 EF loop, which is on the particle surface (Figs. 3a–d and 7a–c).

a EV-D68 A2 substitutions are mapped in B3 InVP, which are highlighted in yellow. b One icosahedral asymmetric unit of EV-D68 B3 InVP. Detailed outward facing A2 substitutions are indicated as yellow dots. c Table for EV-D68 A2 strain substitutions and related structural positions. Substituted residues for VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4 are numbered by the B3 strain.

VP1 shares 95.3% amino acid identity between B3 and A2 subclades among the four subunits. Differences in VP2 are mainly found in loop regions exposed on the particle surface. Notably, R67K, A73T, and T74E are located in the VP2 BC loop, which serves as the epitope for threefold axis-targeting antibodies. In VP3, the substitutions S60N and E65Q in the AB loop, A73V in the BC loop, and D208N in the HI loop are positioned on the particle surface around the threefold axis, forming epitopes for threefold axis-targeting antibodies. Additionally, I236L, D237E, and G241E are located in the VP3 C-terminus, which interacts with VP1 and constitutes a major site of vulnerability to fivefold axis-targeting antibodies. The only substitution in VP4 is V18I, located in the AB loop, which is not detected in either VLP or InVP (Fig. 7a–c). This VP4 substitution may influence the initial stages of viral attachment to host cells or viral entry.

Discussion

Enterovirus D68 is a reemerging enterovirus capable of causing both serious respiratory disease and life-threatening neurological consequences2,3, prompting the development of safe and effective countermeasures22,23. Enterovirus D68 continues to circulate within the human population following a sharp decline in cases due to COVID-19 pandemic countermeasures. During the 2014 and 2018 outbreaks, the dominant virus changed from the B1 subclade to the B3 subclade. Despite the detection of B3 subclade isolates as early as 2014, no structures of this virus or corresponding VLP have been described. Inactivated virus and virus-like particle vaccines are being developed, and a better understanding of their structure could aid the development and use of vaccines for EV-D68 as well as other non-polio enteroviruses of concern. Here, we determined the structures of B3 and A2 subclade EV-D68 inactivated viruses, along with the structures of the corresponding A-particles and VLPs for both viruses. These structures highlight differences between the B3 and A2 viruses in pocket factor binding as well as similarities in important antigenic sites between the InVPs and VLPs for each virus, offering insights into subclade differences that could impact the generation of cross-reactive and durable immune responses and viral features that may impact stability or susceptibility to antivirals.

Compared to InVP, several critical epitope regions in B3 VLP remain flexible and are not structurally captured. For instance, VP1 C-terminus exhibits structural flexibility and serves as the antigenic site for the fivefold axis antibody EV68-22817. VP2 BC loop is flexible and recognized by threefold axis antibody 15C530. The externalization of VP1 N-terminus and VP4 is associated with the fusion process, facilitating the formation of a pore in the endosomal membrane38. In InVP, VP1 N-terminus and VP4 are hidden and inaccessible, whereas in VLP, their flexibility may expose cryptic epitopes. These structural differences could contribute to the generation of immune responses targeting concealed antigenic sites.

We noted subclade-specific differences in the canyon-associated pocket factor. Binding of a fatty acid pocket factor in the hydrophobic pocket of VP1 is known to contribute to virus stability, and displacement after receptor binding triggers the uncoating process for picornaviruses36,37. VP1 GH loop connecting residues between β-strands G and H forms the floor of the canyon. When a receptor binds to the VP1 canyon, the binding pocket is squeezed to expel the pocket factor observed in Fermon strain14. Capsid binding antiviral compounds (e.g., pleconaril, pirodavir, and BTA-188) displace the pocket factor in enteroviruses. They fill the pocket and stabilize the virus to inhibit uncoating and prevent the release of the genome into the infected cell. Also, they can alter the canyon surface to prevent cell attachment39,40. The structure of the prototype strain Fermon shows a 10-carbon fatty acid pocket factor. Limited density corresponding to 4-carbon fatty acid pocket factors is found in both the published B1 virus particle structure and in the structure of the current B3 subclade InVP but is absent in the A2 subclade InVP. While we cannot rule out that A2 subclade virus contains a binding pocket factor in vivo, or that pocket factor loss during the purification or inactivation procedures, or that physical properties such as thermal stability are different in B1, B3, and A2 subclades, we observed amino acid changes in the A2 subclade that potentially introduce a clash with pocket factor. Differences in pocket factor occupancy could impact A2 subclade virion stability or susceptibility to antivirals.

One unexpected finding from the structural analysis of EV-D68 vaccine candidates was the presence of an A-particle. Both B3 and A2 viruses underwent a 20-hour inactivation in the first round. In the second round, B3 was treated for another 20 hours, whereas A2 underwent a shorter 90-minute treatment due to the presence of approximately 10 PFUs (plaque forming units) remaining in the batch, as confirmed by inactivation testing. Comparing the second-round inactivation process, the 90-minute β-propiolactone inactivation of A2 resulted in a lower percentage of expanded A-particles. While we cannot rule out that the abundance of A-particles may be influenced by the intrinsic differences between A2 and B3 isolates, in addition to the treatment duration, our results suggest that a drop in pH during the β-propiolactone inactivation process promotes A-particle conversion due to the acid sensitivity of EV-D6823,29,41. Shortening the inactivation time for the A2 virus substantially lowered the fraction of the preparation that exhibited a structure consistent with A-particle. Importantly, the balance of InVP present as mature viral particles versus A-particles cannot be assessed using negative staining-EM or other approaches and could be a determinant of the quality of the immune responses elicited by vaccination. It is unclear whether the immunogenicity is comparable between A-particle and inactivated virus, as there are clear structural differences between the two species, although two neutralizing antibodies, 1G11 and 15C5, are able to bind A-particle30. Based on our observations, one potential concern of an EV-D68 inactivated virus vaccine is the maintenance of the particles in the mature virion conformation rather than promoting conversion to the A-particle. However, different InVP preparations may yield a different ratio of A-particle to mature virus, depending on the inactivation chemical, such as formalin, β-propiolactone, and H2O2, and time, which can affect the pH of the reaction. Formalin has been widely used to maintain the capsid structure during inactivation and is used in commercial vaccines for picornaviruses such as poliovirus and hepatitis A virus. As reported in a recent study, β-propiolactone treatment resulted in some damaged and empty EV-D68 virus particles, and H2O2 treatment was shown to disrupt most of the inactivated virus particles23.

In summary, we determined cryo-EM structures of VLP, InVP, and A-particle based on the currently circulating B3 and A2 subclades of EV-D68. VLP for both subclades exhibit a high degree of structural similarity to their mature InVP counterparts, particularly at the target of the most potent neutralizing antibodies - the 5-fold axis of symmetry. The 5-fold axis and 3-fold axis structural similarities between the B3 EV-D68 VLP and mature InVP explain the finding of their similar immunogenicity in mice. Both elicit neutralizing activity, which provides protection in a murine passive transfer and respiratory challenge model24. Cryo-EM has become a powerful tool, accelerating vaccine development and antibody characterization. In this study, cryo-EM analysis aids EV-D68 vaccine development by describing structural features of the EV-D68 VLP that suggest the mechanism by which the VLP elicits similar immunogenicity as inactivated virus vaccines. Overall, our results highlight the similarities and differences between mature viral particles and VLPs for the two contemporary EV-D68 subclades and suggest that further studies on the contribution of both inactivation methods and pocket factor binding to the immunogenicity of InVP preparations, viral stability, and susceptibility to antivirals are warranted. As EV-D68 is a ubiquitous virus with a global impact, these findings will be useful for further development of EV-D68 countermeasures.

Method details

VLP and inactivated virus production and purification

Virus-like particles were produced and purified as follows24. Briefly, plasmids expressing the EV-D68 P1 capsid polyprotein and 3CD protease were transfected into Expi293 cells using Expifectamine (ThermoFisher), and cells were frozen 4 to 5 days post-transfection. After thaw, the cells and media were clarified by centrifugation and filtered, then loaded on 20% sucrose cushions and ultracentrifuged at 72,000 × g for 3 h. VLP pellets were resuspended in buffer, loaded on 15–45% sucrose density gradients, and ultracentrifuged at 49,600 × g for 18 h. A band corresponding to the VLP was visualized, and capsid proteins were confirmed in fractions by SDS/PAGE analysis. Gradient fractions were buffer exchanged to PBS, and the VLP was stored at −80 °C before use.

Inactivated virus particles were produced and purified as follows24. A549 cells were infected with EV-D68 at an MOI of 0.05 TCID50 per cell and incubated at 37 °C until the cytopathic effect reached 95%. Infected cells and media were frozen and thawed, then clarified and filtered. Supernatants were loaded on 30% sucrose cushions and ultracentrifuged at 72,000 × g for 3 h. Virus pellets were resuspended in buffer, loaded on 15–45% sucrose density gradients, and ultracentrifuged at 49,600 × g for 18 h. A band corresponding to the virus was visualized, and capsid proteins were confirmed in fractions by SDS/PAGE analysis. Gradient fractions were buffer exchanged to PBS, then inactivated with β-propiolactone (1:4000, SelleckChem) for 20 h at 4 °C, then residual β-propiolactone was neutralized at 37 °C for 1 h. Complete inactivation was confirmed by two sequential blind passages of 10% of the inactivation mixture on A549 cells. If either of these cell cultures demonstrated a cytopathic effect, another β-propiolactone inactivation cycle was performed.

Electron microscopy

For cryo-grids preparation, aliquots (4 μL) of samples were applied to glow-discharged C-flat grids R1.2/1.3 Au, 400 mesh (Protochip, NC) inside the chamber of an FEI Vitrobot Mark IV set to 4 °C and 100% humidity (Thermo Fisher Scientific, OR), followed by instant vitrification in a liquid ethane bath. The datasets were acquired on an FEI Titan Krios microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, OR) operated at 300 keV. 20 eV energy filtered image stacks were recorded by a BioQuantum-K3 camera (Gatan, CA) with SerialEM42 in the super-resolution counting mode. A magnification of 105,000× was used, which renders a final pixel size of 0.830 Å at object scale (0.415 Å in super-resolution). 50 frames were collected for each image stack at a defocus range of −1 to −2.5 μm. Each image stack had a total electron exposure of 54.5 e–/Å2.

Image processing

For B3 VLP and A2 VLP datasets, 4173 and 4014 qualified movie stacks were selected for image processing, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2). Data processing workflow, including motion correction, CTF estimation, particle picking and extraction, 2D classification, ab-initio reconstruction, homogeneous refinement, heterogeneous refinement, and non-uniform refinement with icosahedral symmetry applied was carried out in cryoSPARC 3.343. The overall resolution of the B3 VLP density map is 2.42 Å (72,000 particles). The overall resolution of the A2 VLP density map was 2.43 Å (37,000 particles).

For B3 InVP and A2 InVP datasets, 3491 and 5418 movie stacks were collected, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3). After the first round of 2D classification, 44,291 particles and 11,895 particles were selected for further ab-initio reconstruction and heterogeneous refinement, respectively. A-particle and InVP were observed in both datasets. In the B3 InVP dataset, 37,761 A-particles were used to reconstruct 2.86 Å density map. 1,741 InVPs were refined to generate a global density map at an overall resolution of 2.73 Å. In the A2 InVP dataset, 859 A-particles were used to reconstruct 3.96 Å density map. 10,194 InVPs were refined to generate a global density map at an overall resolution of 2.64 Å.

The resolution estimation was based on gold-standard FSC at the cutoff of 0.143. Structural analysis was done with UCSF Chimera 1.11.244 and Pymol (http://pymol.org).

Model building

The coordinate of the EV-D68 inactivated virus particle (PDB: 6WDT) was used as an initial model for fitting the cryo-EM map (Table 1). Each subunit was manually fitted into the density map in Chimera, followed by manual rebuilding using Coot 0.9.545. The models were refined using Phenix.real_space_refine46 with secondary structure restraints and geometry restraints imposed. The final models were evaluated by MolProbity 1.19.247, and statistics are presented in Table 1.

Statistics and reproducibility

Validation statistics presented in Table 1 are output by MolProbity 1.19.247.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Cryo-EM maps of EV-D68 B3 VLP, A2 VLP, B3 InVP, B3 A-particle, A2 InVP, and A2 A-particle have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) with accession codes EMD-45171, EMD-45179, EMD-45306, EMD-45303, EMD-45304, and EMD-45305, respectively. Atomic coordinates of EV-D68 B3 VLP, A2 VLP, B3 InVP, B3 A-particle, A2 InVP, and A2 A-particle have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession codes 9C3J, 9C4A, 9C8I, 9C8F, 9C8G, and 9C8H, respectively.

References

Baggen, J., Thibaut, H. J., Strating, J. & van Kuppeveld, F. J. M. The life cycle of non-polio enteroviruses and how to target it. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 368–381 (2018).

Palacios, G. & Oberste, M. S. Enteroviruses as agents of emerging infectious diseases. J. Neurovirol. 11, 424–433 (2005).

Muehlenbachs, A., Bhatnagar, J. & Zaki, S. R. Tissue tropism, pathology and pathogenesis of enterovirus infection. J. Pathol. 235, 217–228 (2015).

Elrick, M. J., Pekosz, A. & Duggal, P.Enterovirus D68 molecular and cellular biology and pathogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100317 (2021).

Grizer, C. S., Messacar, K. & Mattapallil, J. J. Enterovirus-D68—a reemerging non-polio enterovirus that causes severe respiratory and neurological disease in children. Front. Virol. 4 https://doi.org/10.3389/fviro.2024.1328457 (2024).

Midgley, S. E. et al. Co-circulation of multiple enterovirus D68 subclades, including a novel B3 cluster, across Europe in a season of expected low prevalence, 2019/20. Euro Surveill. 25 https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.2.1900749 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Genetic changes found in a distinct clade of Enterovirus D68 associated with paralysis during the 2014 outbreak. Virus Evol. 2, vew015 (2016).

Fang, Y. et al. The role of conformational epitopes in the evolutionary divergence of enterovirus D68 clades: a bioinformatics-based study. Infect. Genet. Evol. 93, 104992 (2021).

Caspar, D. L. & Klug, A. Physical principles in the construction of regular viruses. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 27, 1–24 (1962).

Hogle, J. M., Chow, M. & Filman, D. J. Three-dimensional structure of poliovirus at 2.9 A resolution. Science 229, 1358–1365 (1985).

Rossmann, M. G. et al. Structure of a human common cold virus and functional relationship to other picornaviruses. Nature 317, 145–153 (1985).

Sherry, B., Mosser, A. G., Colonno, R. J. & Rueckert, R. R. Use of monoclonal antibodies to identify four neutralization immunogens on a common cold picornavirus, human rhinovirus 14. J. Virol. 57, 246–257 (1986).

Liu, Y. et al. Sialic acid-dependent cell entry of human enterovirus D68. Nat. Commun. 6, 8865 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. Structure and inhibition of EV-D68, a virus that causes respiratory illness in children. Science 347, 71–74 (2015).

Rossmann, M. G. The canyon hypothesis. Hiding the host cell receptor attachment site on a viral surface from immune surveillance. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 14587–14590 (1989).

Hodcroft, E. B. et al. Evolution, geographic spreading, and demographic distribution of Enterovirus D68. PLoS Pathog. 18, e1010515 (2022).

Vogt, M. R. et al. Human antibodies neutralize enterovirus D68 and protect against infection and paralytic disease. Sci. Immunol. 5 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aba4902 (2020).

Wei, W. et al. ICAM-5/telencephalin is a functional entry receptor for enterovirus D68. Cell Host Microbe 20, 631–641 (2016).

Varanese, L. et al. MFSD6 is an entry receptor for enterovirus D68. Nature 641, 1268–1275 (2025).

Liu, X. et al. MFSD6 is an entry receptor for respiratory enterovirus D68. Cell Host Microbe. 33, 267–278.e4 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Immunogenicity and safety of inactivated enterovirus A71 vaccines in children aged 6-35 months in China: a non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 16, 100284 (2021).

Sutter, R. W., Eisenhawer, M., Molodecky, N. A., Verma, H. & Okayasu, H. Inactivated poliovirus vaccine: recent developments and the tortuous path to global acceptance. Pathogens 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13030224 (2024).

Senpuku, K., Kataoka-Nakamura, C., Kunishima, Y., Hirai, T. & Yoshioka, Y. An inactivated whole-virion vaccine for Enterovirus D68 adjuvanted with CpG ODN or AddaVax elicits potent protective immunity in mice. Vaccine 42, 2463–2474 (2024).

Krug, P. W. et al. EV-D68 virus-like particle vaccines elicit cross-clade neutralizing antibodies that inhibit infection and block dissemination. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg6076 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. Enterovirus D68 virus-like particles expressed in Pichia pastoris potently induce neutralizing antibody responses and confer protection against lethal viral infection in mice. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 7, 3 (2018).

Verardi, R. et al. Disulfide stabilization of human norovirus GI.1 virus-like particles focuses immune response toward blockade epitopes. NPJ Vaccines 5, 110 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. The C-terminal arm of the human papillomavirus major capsid protein is immunogenic and involved in virus-host interaction. Structure 24, 874–885 (2016).

Dong, H., Guo, H. C. & Sun, S. Q. Virus-like particles in picornavirus vaccine development. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 4321–4329 (2014).

Liu, Y. et al. Molecular basis for the acid-initiated uncoating of human enterovirus D68. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E12209–E12217 (2018).

Zheng, Q. et al. Atomic structures of enterovirus D68 in complex with two monoclonal antibodies define distinct mechanisms of viral neutralization. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 124–133 (2019).

Moss, D. L., Paine, A. C., Krug, P. W., Kanekiyo, M. & Ruckwardt, T. J. Enterovirus virus-like-particle and inactivated poliovirus vaccines do not elicit substantive cross-reactive antibody responses. PLoS Pathog. 20, e1012159 (2024).

Eshaghi, A. et al. Global distribution and evolutionary history of enterovirus D68, with emphasis on the 2014 outbreak in Ontario, Canada. Front. Microbiol. 8, 257 (2017).

Shi, Y., Liu, Y., Wu, Y., Hu, S. & Sun, B. Molecular epidemiology and recombination of enterovirus D68 in China. Infect. Genet. Evol. 115, 105512 (2023).

Dai, W., Li, X., Liu, Z. & Zhang, C. Identification of four neutralizing antigenic sites on the enterovirus D68 capsid. J. Virol. 97, e0160023 (2023).

Smith, T. J. et al. The site of attachment in human rhinovirus 14 for antiviral agents that inhibit uncoating. Science 233, 1286–1293 (1986).

Filman, D. J. et al. Structural factors that control conformational transitions and serotype specificity in type 3 poliovirus. EMBO J. 8, 1567–1579 (1989).

Smyth, M., Pettitt, T., Symonds, A. & Martin, J. Identification of the pocket factors in a picornavirus. Arch. Virol. 148, 1225–1233 (2003).

Elrick, M. J., Pekosz, A. & Duggal, P. Correction: Enterovirus D68 molecular and cellular biology and pathogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100587 (2021).

Egorova, A., Ekins, S., Schmidtke, M. & Makarov, V. Back to the future: advances in development of broad-spectrum capsid-binding inhibitors of enteroviruses. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 178, 606–622 (2019).

Sun, L. et al. Antiviral activity of broad-spectrum and enterovirus-specific inhibitors against clinical isolates of Enterovirus D68. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 7782–7785 (2015).

Oberste, M. S. et al. Enterovirus 68 is associated with respiratory illness and shares biological features with both the enteroviruses and the rhinoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 85, 2577–2584 (2004).

Mastronarde, D. N. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol. 152, 36–51 (2005).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera-a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010).

Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Stuckey for assistance with figures, and members of the Structural Biology Section and Structural Bioinformatics Core, Vaccine Research Center, for discussions or comments on the manuscript. We thank the cryo-EM facilities at NIAID, NIDDK, and NIH IRP CryoEM Consortium (NICE) for assistance with cryo-EM sample preparation, screening, and final collection. We thank Y. Tsybovsky from the Vaccine Research Center Electron Microscopy Unit, Cancer Research Technology Program, NCI at Frederick, for NS-EM data analysis and cryo-EM data collection. This research, including publication costs, was funded by the Vaccine Research Center, an intramural Division of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C., P.W.K., D.L.M., T.C.P., T.Z., T.J.R., and P.D.K. conceived and designed experiments. J.C., P.W.K, H.L., D.L.M., Z.C.L., A.J.M, C.S., S.P., R.K.H., T.C.P., T.Z., T.J.R., and P.D.K. performed experiments, analyzed data, and prepared figures. J.C., P.W.K., T.C.P., T.Z., T.J.R., and P.D.K. prepared the first draft of the manuscript, which all authors reviewed and edited. All authors agreed to submit the manuscript, read and approve the final draft, and assume full responsibility for its content.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Anna Urbanowicz, Juan Jose Lopez-Moya, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Laura Rodríguez Pérez.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, J., Krug, P.W., Lei, H. et al. Structural insights from vaccine candidates for EV-D68. Commun Biol 8, 860 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08253-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08253-y