Abstract

Adult cardiomyocytes are embedded within a highly organized myocardial microenvironment that imposes critical geometric cues essential for the alignment and distribution of organelles and the shaping of their unique, rectangular cellular morphology. Despite the association of cardiomyocyte disarray with human heart disease, the functional consequences of this cellular disorganization remain poorly understood. Here, we leveraged micropatterned substrates to promote structural alignment in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs), contrasting the effects of mechanical alignment on mitochondrial form and function with hiPSC-CMs cultured under standard unconstrained conditions. Cardiomyocytes cultured under unconstrained conditions exhibited misaligned sarcomeres and a perinuclear mitochondrial distribution while micropatterned hiPSC-CMs developed linear myofibrils and reconfigured sarcomere and mitochondrial organization, which increased mitochondrial respiration without augmenting mitochondrial mass. Notably, micropatterned hiPSC-CMs exhibited an increased number of mitochondria-associated membranes, as determined by proximity ligation assays and transmission electron microscopy, suggesting enhanced interactions between the sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Together, these findings demonstrate that mitochondrial-sarcoplasmic architecture and geometry are critical spatial features that ensure bioenergetic efficiency of cardiomyocytes. This work underscores the importance of cellular organization in cardiomyocyte metabolism and function, providing insights into the pathophysiology of cardiac diseases marked by cellular disarray.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The human cardiac muscle tissue presents a complex anisotropic architecture characterized by the helical arrangement of linear myocardial fibers, which is critical for its mechanical performance and the propagation of electrical signals within the myocardium1,2. This structure is formed during embryonic development and is supported by a highly structured microenvironment that imposes specific physical boundary conditions on cardiomyocytes. As a consequence, healthy cardiomyocytes are typically rod-shaped and aligned along a major elongation axis3. This geometry configures the linear alignment of myofibrils and sarcomeres along the long axis of cells, ensures the intracellular organization of organelles, and the polarization of cardiomyocytes for proper cellular function4,5.

Disruption of this organized architecture, referred to as myocardial disarray, is observed in many cardiac diseases. Myocardial disarray generally refers to disorganized cardiomyocyte spatial distribution, with loss of physiological fiber alignment and orientation at the histological level. Myocardial disarray was originally described as an archetypal feature of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)6,7, but has also been found in other cardiac conditions including congenital heart disease, myocardial remodeling in ischemic heart diseases, genetic and acquired cardiomyopathies8,9. At the cellular level myofibrillar disarray, within cardiomyocytes, disrupts sarcomere. In patients with HCM, it was recently reported that myofibril disorganization was associated with mitochondrial dysfunction due to an improper organization around myofibrils10. To ensure an efficient contraction of cardiomyocytes, mitochondria and the sarcoplasmic reticulum must be positioned in close vicinity of the contractile apparatus to provide the necessary ATP and calcium cycling required to power myofilament function. While various genetic, infectious, and mechanical insults are associated with defects in these structural networks, the causal and functional relationships between cardiomyocyte architecture and function in humans remain incompletely understood.

One barrier to addressing these questions has been the limitations of human cellular cardiomyocyte models, which often fail to recapitulate the geometry and organization observed in adult cardiomyocytes, thereby limiting the study of structure-function relationships. To address this limitation, techniques, such as micropatterning methods, help in guiding the spatial organization of cardiomyocytes into a precise cell adhesion pattern11,12,13. Here, we developed a novel method for promoting sarcomere alignment and organization by culturing cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC-CMs) on bespoke micropatterned substrates composed of repeated lines of 30 µm-width separated with a cell repellent to impose specific geometric features. We then compared hiPSC-CMs cultured under these micropatterned conditions, which promote architectural alignment, to hiPSC-CMs cultured under standard unconstrained conditions which lack such alignment. Rather than modeling pathological remodeling directly, our approach provides a controlled experimental framework to investigate how differences in cellular architecture influence cardiomyocyte structure and function, offering insights into mechanisms that may contribute to contractile dysfunction observed in diseases characterized by myocardial disarray. We notably found that architecture organization was a key driver of the efficiency of cardiomyocytes’ mitochondrial respiration, which was explained by enhanced mitochondrial/sarcoplasmic interactions and increased ion and lipid transfer between organelles.

Results

The culture of hiPSC-CMs as linear microfibers improves structural organization

We first generated ventricular hiPSC-CMs using the Wnt modulation protocol with glucose starvation14,15. The expression of pluripotency markers was validated by immunostaining and RT-qPCR (Supplementary Fig. 1A-C). Approximately 10 days after cardiac induction, cultures began displaying a contractile phenotype, and flow cytometry analysis on day 21 indicated an average proportion of 94.8 ± 6.0% TNNT2-positive cells (Supplementary Fig. 1D). The hiPSC-CM displayed typical expression of cardiac and sarcomere proteins (Supplementary Fig. 1E-F).

At 35 days of differentiation, the cells were enzymatically detached and replated onto micropatterned or unconstrained control (i.e., without linear micropatterning or non-patterned) coverslips coated with Matrigel (Fig. 1A). Briefly, the micropatterned coverslips consist of repeated lines of 30 µm-width surrounded by a polymer with oxidation resistance and anti-adhesive properties (Fig. 1B). On these micropatterned coverslips, Matrigel can only coat areas without the anti-adhesive agent thus creating boundaries for the generation of linear myofibrils as observed during embryogenesis. Otherwise, the culture condition is identical between micropatterned and control hiPSC-CMs.

A Schematic overview of the study. On day 35 of differentiation, hiPSC-CMs were seeded onto micropatterned or non-patterned slides for 7 days before functional phenotyping. Created in BioRender. B Schematic representation of the profile (left) and top (right) view of the adhesive micropatterns. Created with Biorender.com. C Representative phase-contrast images of non-patterned cells (left) and micropatterned-cells (right), scale bar 400 µm. D Representative immunofluorescence images of non-patterned and micropatterned hiPSC-CMs, for alpha-sarcomeric actinin (green), cardiac Troponin T2 (red) at day 7 after seeding. DAPI (blue) was used to stain nuclei. The insert represents a zoomed view of sarcomeres. Global scale bar 100 µm, insert scale bar 10 µm. E Automated measures of sarcomere organization and sarcomere length. (Left) Immunofluorescence images of non-patterned (top) and micropatterned (bottom) hiPSC-CMS. Scale bar 25 µm. (Right) Haralick correlation metric computed at multiple offset distances and angles to determine sarcomere organization and sarcomere length. Sarcomere organization score is the maximum amplitude of the decaying sinusoidal trace. Sarcomere length is the distance to the first peak. Scatter plots show quantification data for length-to-width ratio (F), sarcomere organization (G) and cell-sarcomere misalignment (H) and sarcomere length (I). n = 138 non-patterned cells, n = 120 micropatterned cells; N = 3–4 differentiations. Results, mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses: Unpaired t-test was used for F–I. **P < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 for the comparisons indicated.

Remarkably, the linear micropatterning substrate was able to spatially regulate the attachment and growth of hiPSC-CMs and promote multiple cardiomyocytes to form end-to-end connections, generating linear and aligned cardiac microfibers exhibiting a geometry comparable to that of primary adult cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. 2A). In comparison, hiPSC-CMs cultured under standard unconstrained conditions showed a round to polygonal shape uncharacteristic of healthy, primary adult cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1C). Seven days after replating, we assessed the cell morphology and sarcomere organization by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1D). While all cells expressed the sarcomere protein cardiac troponin T2 and the cardiac Z-disk protein α-actinin (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Fig. 2B), micropatterned hiPSC-CMs displayed an organized contractile machinery, characterized by an increase in the alignment of myofibrils throughout the cytoplasm of the cell and a better directionality within the microfiber. In contrast, hiPSC-CMs cultured under standard unconstrained conditions also showed sarcomere formation but with a lower degree of alignment and strikingly larger disorganization, consistent with previous reports16 and characteristic of myocardial disarray.

To further characterize the organization of sarcomeres under both conditions, we used SarcOmere Texture Analysis method17, a pixel-based image analysis for assessing sarcomere structure with alpha-actinin immunofluorescence (Fig. 1E and Supplementary Fig. 3A). The cell elongation (measured by the ratio of the major axis length to the minor axis length) was largely increased in micropatterned hiPSC-CMs (p < 0.0001, Fig. 1F), which reciprocally had a lower cell circularity index (Circularity = 4π x Area x Perimeter−2) (Fig. S3B). Notably, micropatterned cardiomyocytes had a far greater number of aligned myofibrils, as evidenced by an increase in sarcomere score organization (p < 0.0001, Fig. 1G and Supplementary Fig. 3A) and a decrease in the cell-sarcomere misalignment (p < 0.0001, Fig. 1H). Finally, we observed an increase in the resting sarcomere length in micropatterned hiPSC-CMs (p < 0.01, Fig. 1I).

Altogether, these data showcase the impact of micropatterning on the linear architectural organization and its ability to force sarcomere alignment in hiPSC-CMS.

RNA-sequencing identifies changes in metabolic genes

We then asked whether the architectural changes could influence cardiomyocyte gene expression and performed mRNA-sequencing analysis. We first compared the native hiPSCs and the differentiated hiPSC-CMs by hierarchical clustering and tSNE analysis of their transcriptomes and confirmed a clear separation between their expression profiles (Supplementary Fig. 4A–C). Reactome gene set analysis (ReactomeGSA), a pathway analysis package, detected a down-regulation of pluripotency and proliferation, and an up-regulation of muscle formation and contraction in hiPSC-CMs, and confirmed a similar efficiency of the differentiation process in both micropatterned and non-patterned culture conditions (Supplementary Fig. 4D).

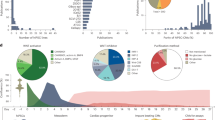

Despite marked structural differences between micropatterned and non-patterned hiPSC-CMs, the transcriptomic comparisons between micropatterned and non-patterned hiPSC-CMs showed no differential expression at the single-transcript level (Supplementary Fig. 4B). However, gene set analysis with ReactomeGSA detected 40 altered pathways involved primarily in metabolism and signal transduction (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 4E–F). Among these, four pathways indicated significant up-regulation of the lipid metabolism in micropatterned hiPSC-CMs (Fig. 2B). More specifically, a significant up-regulation of genes involved in the metabolism of triglycerides and carnitines was observed (Fig. 2C). Concordant with a change in metabolic pathways in micropatterned hiPSC-CMs, other up-regulated pathways including fatty acid oxidation, TCA, and respiratory electron transport pathways were observed (Fig. 2C). On the other hand, genes associated with glycolysis were significantly down-regulated (Fig. 2D). Given that cardiac energy metabolism relies primarily on fatty acid oxidation to fuel the bioenergetic needs of cardiomyocytes, we further focused on the carnitine pathway (Supplementary Table 1) and studied the protein expression of three major components of the pathway, including Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and the carnitine palmitolytransferase (CPT1). We found that while total ACC and AMPK steady were not different between conditions, the levels of the fatty acid mitochondrial transporter CPT1 were increased in micropatterned vs. non-patterned hiPSC-CMs (Fig. 2E–F). In line, we found a significant increase in the pACCSer79:ACCtotal in micropatterned hiPSC-CMs (Fig. 2G), suggesting a lower conversion of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA which is a known inhibitor of fatty acid transport into mitochondria.

A Pie chart summarizing the classification of all the significantly changed pathways (FDR < 0.01) in micropatterned vs. non-patterned hiPSC-CMs as found with ReactomeGSA. B Voronoi diagram displaying the significantly altered lipid metabolism pathways (FDR < 0.01) in micropatterned vs. non-patterned hiPSC-CMs (generated by ReactomeGSA). The upregulated pathways are colored yellow, while the downregulated pathways are colored blue. C Upregulated energy metabolism pathways identified by ReactomeGSA comparing micropatterned vs non-patterned hiPSC-CMs showing their corresponding p-value as -Log10(p-value). D Downregulated energy metabolism pathways identified by ReactomeGSA comparing micropatterned vs non-patterned hiPSC-CMs showing their corresponding p-value as -Log10(p-value). E Representative Western blot images showing the expression of ACC (total and phosphorylated at Ser79), AMPK (total and phosphorylated at Thr172), and CPT1 on non-patterned (NP) and micropatterned (M) hiPSC-CMs. Vinculin was used as loading control. F Quantification of total proteins ACC, AMPK, and CPT1 in micropatterned hiPSC-CMs (n = 8, expressed as fold change relative to non-patterned for each cardiac differentiation). G Quantification of p-ACCSer79/ACC and p-AMPKThr172/AMPK ratio in micropatterned hiPSC-CMs (n = 8, expressed as fold change relative to non-patterned for each cardiac differentiation). Results, mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses: Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for F, and G. *p < 0.05, ns not significant for the indicated comparisons.

Altogether, these changes point to a shift in substrate preference in the micropatterned hiPSC-CMs and support that the architectural organization of hiPSC-CMs drives their metabolic rewiring.

Changes in respiratory functions according to sarcomere organization

As our RNA-sequencing data indicated a significant change in pathways related to energy metabolism, we tested whether the architectural manipulation led to changes in respiratory functions. We characterized mitochondrial respiration by measuring oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in micropatterned vs. non-patterned hiPSC-CMs in basal conditions and after the addition of oligomycin (an inhibitor of ATP synthase), FCCP (a mitochondrial electron uncoupler), rotenone and antimycin A (complexes I and III inhibitors) (Fig. 3A). We found that micropatterned hiPSC-CMs displayed a strong increase in OCRs associated with basal respiration, ATP production (coupled respiration), and maximal respiration as compared to non-patterned hiPSC-CMs (Fig. 3A–B). We observed no changes in spare respiratory capacity and proton leak, suggesting that the observed overall increase in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) capacity is not the result of uncoupling (Supplementary Fig. 5A). We observed no differences in the ECAR values between micropatterned-CMs and non-patterned-CMs in response to the addition of glucose, indicating that mitochondrial utilization of pyruvate derived via glycolysis is equally efficient in both cell types. Similarly, the subsequent addition of oligomycin yielded a commensurate and comparable increase in ECAR, demonstrating that the inhibitory effect on ATPase activity is equivalent (Fig. 3C–D and Supplementary Fig. 5B). When comparing the energy phenotype from micropatterned-CMs and non-patterned-CMs, we observed that micropatterned cells adopted a more aerobic profile due to an increased capacity to consume oxygen, whereas non-patterned cells were more glycolytic (Fig. 3E).

A Real-time oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measurements of micropatterned and non-patterned hiPSC-CMs by Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer. Cells were treated with the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin, the respiratory uncoupler FCCP, and the respiratory chain blockers rotenone and antimycin A. B Scatter plots show basal respiration, production of ATP, and maximal respiration. N = 8–11 differentiations. C Real-time extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) measurements of hiPSC-CMs non-patterned and micropatterned by Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer. Cells were treated with glucose, ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin, and glucose analog 2-DG. D Scatter plots show glycolysis, non-glycolytic acidification, and glycolytic capacity. N = 4–12 differentiations. E Cell energy diagram showing normalized oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and normalized extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) of micropatterned and non-patterned hiPSC-CMS at the basal (circle points) and stressed (FCCP exposed, square points) conditions. F Representative profiles of oxygen consumption of non-patterned (top) and micropatterned (bottom) hiPSC-CMs measured in permeabilized cells with complex protocol using Oxygraph-2k high resolution respirometry (generated by DatLab). Digitonin (Dig, 10 µg/ml), pyruvate (P, 1 mM) and malate (M, 4 mM), ADP (2 mM), succinate (10 mM), amytal (2 mM), oligomycin (10 µM), and TMPD (0.5 mM) combined with ascorbate (2 mM) were added sequentially. Blue line stands for decreasing oxygen concentration in the oxygraphy chamber containing permeabilized cells. Red line stands for the changes of oxygen flux per volume. G Oxygen flux (attomol/sec/cell) quantified in non-patterned and micropatterned hiPSC-CMs. n = 7 in each group from 3 independent differentiation. Results, mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses: Mann–Whitney was used for B and D, two-way ANOVA was used for G. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ns: not significant for the indicated comparisons.

To determine whether the intrinsic organization of mitochondria within patterned cardiomyocytes is responsible for the increased OXPHOS capacity observed in micropatterned cells, we measured oxygen consumption rates by high-resolution respirometry in digitonin-permeabilized cells using the Oroboros system (Fig. 3F–G). We found similar oxygen flux rates in the presence of pyruvate, malate and ADP (state 3) and succinate in both groups. As in intact cells, we observed no differences in state 4 respiration (addition of oligomycin) indicating that mitochondria are equally coupled. Finally, the activity of cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal enzyme of the respiratory chain that consumes oxygen in mitochondria, was measured by injecting TMPD and Ascorbate, revealing indistinguishable levels of activity.

Taken together, our data indicate that the linear architectural organization of sarcomeres drives increase bioenergetic efficiency by creating an intracellular environment that can maximize mitochondrial respiration without altering the expression of the components of the OXPHOS system. In the absence of structural remodeling of hiPSC-CMs, cells retain a more glycolytic preference due to an inability to boost OXPHOS activity.

Effect of linear micropatterning on mitochondria organization

To explore the cellular basis of increased OXPHOS capacity of mitochondria, we used MitoTrackerTM dye as an indicator to assess the mitochondrial network morphology from micropatterned and non-patterned hiPSC-CMs. As shown in Fig. 4A, the mitochondrial network from micropatterned hiPSC-CMs appeared to be more homogeneously distributed and organized along the myofibrils, compared to the non-patterned hiPSC-CMs where mitochondria accumulated around the nucleus (Supplementary Fig. 6A). This was evidenced by an increase in mitochondrial directionality within the microfiber (Fig. 4B). IMARIS analysis revealed that global mitochondrial volume was increased in the micropatterned condition compared to the non-pattern condition albeit modestly (1.065%) (Fig. 4C–D), without a significant change in cardiomyocyte cell surface (Supplementary Fig. 6D). The distribution of mitochondrial volume was identical to the non-patterned condition (Supplementary Fig. 6E). No difference was found in the number of mitochondria by imaging analysis (Fig. 4E) or by quantification of mtDNA content (Fig. 4F). Mitochondrial Orange signal labeling actively respiring cells (Supplementary Fig. 6B) and Mitotracker mitochondrial mass (Supplementary Fig. 6C) were similar in both conditions. Concordant with the Seahorse and Oroboros respiration measurements (Fig. 3) and in line with the RNA-sequencing data, the steady state levels of OXPHOS proteins and subunits of mitochondrial complexes required for mitochondrial biogenesis (ATP5A, UQCRC2, SDHB, I-NDUFB8, TOMM40, VDAC, OPA1, and SDHA) were not significantly different between micropatterned and non-patterned hiPSC-CMs (Fig. 4G). Taken together, our data indicate that increased OXPHOS capacity driven by structural reorganization of micropatterned hiPSC-CMs is not the result of increased mitochondrial biogenesis nor in changes in mitochondrial content.

A Mitochondrial distribution stained by MitoTrackerTM Orange (red) and DAPI (blue) and analysed by confocal microscopy. The insert represents a zoomed view of mitochondrial network. Global scale bar 50 µm, insert scale bar 10 µm. B Quantitative analysis of mitochondrial direction measured with Fiji software. n = 18 non-patterned cells, n = 16 micropatterned cells; N = 2 differentiations. C Representative pictures obtained with MitoTrackerTM Orange and IMARIS software. Each mitochondrion is identified by a color in accordance with its volume (the smallest mitochondria are blue and the largest are red). D Total mitochondrial volume quantified by IMARIS. n = 28,675 non-patterned cells, n = 64,919 micropatterned cells; N = 3 differentiations. E Scatter plots show the number of mitochondria per cell. n = 18 non-patterned cells, n = 20 micropatterned cells; N = 3 differentiations. F Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content in non-patterned (n = 17) and micropatterned (n = 11) hiPSC-CMs, quantified by amplification of the mitochondrial Mttl1 gene relative to nuclear gene b-Actin. N = 3 differentiations. G Cardiac level of ATP5A, UQCRC2, SDHB, I-NDUFB8, TOMM40, VDAC, OPA1, and SDHA were analysed by western blot in non-patterned and micropatterned hiPSC-CMs. Total Histone3 was used as loading control (n = 6). Results, mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses: Unpaired t-test was used for C, Mann–Whitney was used for D through G. *p < 0.05, ns: not significant for the indicated comparisons.

Increased interactions between sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria following linear organization of sarcomeres

To gain insights in the mechanism underlying increased bioenergetic output in micropatterned cardiomyocytes, we turned our attention on the spatial organization and interaction of myofilaments, mitochondria, and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). In line with the immunostaining results, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses uncovered an ultrastructural improvement in micropatterned hiPSC-CMs with an organization of the mitochondrial network relative to the myofibrils and the SR closer to the one observed in primary adult cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Fig. 7A). Under micropatterned conditions, mitochondria were found to be significantly longer and more elongated (Fig. 5B).

A Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the cellular structure of non-patterned (top) and micropatterned (bottom) hiPSC-CMS in transverse cross-sections; scale=1 µm. Mf indicates myofibril; Mt mitochondria; and SR sarcoplasmic reticulum. B Quantitative measurement of mitochondria surface (left) and circularity (right) on the TEM images. n = 10 fields per conditions with 5 to 15 mitochondria per field, N = 3 differentiations. C Schematic representation of the VDAC1/GRP75/IP3R1 complex at MAM interface. Created with Biorender.com. D Left: representative PLA images. The insert represents a zoomed view of PLA signal. Each white dot corresponds to a positive PLA signal. Right: quantitative analysis of VDAC1-IP3R1, GRP75-IP3R1 and VDAC1-GRP75 interactions signal in non-micropatterned and micropatterned hiPSC-CMs. n = 10 images/conditions, N = 3 differentiations. Scale bar 100 µm. E Representative images of Rhod-2 AM (green) and MitoTrackerTM Deep Red (red) staining in non-patterned and micropatterned hiPSC-CMs. Scale bar 10 µm. F Quantitative analysis of Rhod-2 AM intensity of loaded non-patterned and micropatterned hiPSC-CMs with Fiji software. n = 25-27 fields from 4 differentiation, expressed as fold change relative to non-patterned for each cardiac differentiation. Results, mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses: Student t-test was used for B Mann–Whitney test was used for D Unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction was used for F. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant for the indicated comparisons.

As the SR interacts physically and functionally with mitochondria through mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs), we tested proteins that tether the two organelles together (Fig. 5C). IP3R1 on the SR interacts with VDAC1 on the outer mitochondrial membrane through the molecular chaperone glucose-regulated protein 75 (GRP75)18. We first checked that the expression levels of IP3R1, VDAC1 and GRP75 proteins were not significantly different between the two conditions (Supplementary Fig. 7B). We then assessed whether the interconnection between SR and mitochondria is modified and whether it may be linked to the increased mitochondrial oxidative function in linear architectural pattern. We evaluated the contact point between the two organelles using the in situ PLA assay (Supplementary Fig. 7C) as previously described19,20. The IP3R1-VDAC1, IP3R1-GRP75 and VDAC1-GRP75 interactions were significantly increased in micropatterned hiPSC-CMs, indicating that the physical SR-mitochondria interconnections are enhanced (Fig. 5D and Supplementary Fig. 7C).

The increased IP3R1-GRP75-VDAC1 interaction is proposed to enhance the direct channeling of Ca2+ from the SR to the mitochondria. To cross the inner mitochondrial membrane, Ca2+ passes through the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) complex creating an IP3R1-GRP75-VDAC-MCU Ca2+ transfer axis21. We thus evaluated mitochondrial calcium ion levels in non-patterned and micropatterned hiPSC-CMs by using Rhod-2, AM fluorescence probe. Analysis of Rhod-2 fluorescence intensity revealed a significant increase in mitochondrial calcium content in micropatterned cells (Fig. 5E-F), whereas MCU and MICU1 expression were not different between both conditions (Supplementary Fig. 8). These results demonstrate that linear architectural reorganization enhances SR-mitochondria interactions, leading to increased mitochondrial calcium uptake.

Discussion

Many cardiac diseases are associated with remodeling processes that profoundly alter the architecture of myocardial tissue22. Myocardial disarray was initially observed at the histological level8, but the disorganization also occurs at the cellular level. The spatial organization of the sarcomere is known to be critical for proper tension generation during myocyte excitation. However, the relationships between architectural changes in inter-organelle interactions and their functional consequences during heart failure in humans are poorly understood. This is partly due to the lack of human in vitro models that enable the systematic study of the cellular disorganization relevant to myocardial dysfunction in patients.

Here, we used a micropatterning strategy to induce architectural organization and sarcomere alignment as observed in normally formed human cardiomyocytes23, enabling direct comparison with cardiomyocytes cultured under unconstrained conditions that lack such organization. While other studies have employed micropatterning to improve cardiomyocytes cellular organization, they have used different designs and have varied in the extent of structural and functional characterization12,13,24. Strikingly, we found that enforcing linear architectural organization in human cardiomyocytes enhances the bioenergetic efficiency of mitochondria. Our data indicate that the improved mitochondrial respiration following linear architectural organization is not explained by an increase in the mitochondrial mass or biogenesis, but rather by a cellular organization of the mitochondrial network relative to the myofibrils that recapitulate the organization observed in isolated mammalian primary cardiomyocytes with mitochondria in micropatterned hiPSC-CMs that were mainly located in intrafibrillar regions of the cardiomyocyte. This leads to higher SR-mitochondria interactions, leading to higher exchanges between organelles, including increased mitochondrial calcium uptake. Conversely, reduced mitochondrial respiration in disorganized cardiomyocytes was not associated with a reduced number of mitochondria or abnormal expression of mitochondrial proteins, highlighting the importance of the quality and organization of mitochondria in facilitating optimal respiratory capacity.

Mitochondria are symbiotic partners with the other cellular components. Cross-talk between the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and mitochondria is essential for several cellular processes, including lipid synthesis and transport25, mitochondrial function26 and regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis27. The SR physically and functionally interacts with mitochondria through mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs). MAMs are microdomains that allow efficient transfer of calcium and lipids between the SR and mitochondria, further regulating metabolism25,28. These interactions are mediated by tethering proteins, including the voltage-dependent ion channel (VDAC1) on the outer mitochondrial membrane, the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor (IP3R)-1 complex on the SR and the molecular chaperone glucose-regulated protein 75 (GRP75)18. While the expression levels of IP3R1, VDAC1 and GRP75 proteins were not affected by the architectural constraints, in situ proximity ligation assay showed that the integrity of MAMs was disrupted in disorganized non-patterned hiPSC-CMs, indicating a reduction in the number of SR-mitochondria contact sites. In addition, measurements with Rhod-2 fluorescent probe indicate lower mitochondrial calcium levels in the non-patterned hiPSC-CMs. The importance of MAMs in the pathogenesis of heart failure is increasingly recognized, but the mechanisms regulating MAM formation and their function in cardiomyocytes remain elusive. Our findings highlight the key role of the anisotropic structure of the myofibrils in the correct formation of MAMs. Whether our micropatterning approach would further help to understand the role of MAMs in the failing hearts or in cardiomyopathies (e.g., using mutant hiPSC-CMs) deserves further investigation.

Our data support the notion that altering cellular morphology and structural organization of human cardiomyocytes is sufficient to modulate mitochondrial energy metabolism, which helps reconcile the long-standing yet unexplained observation of cardiomyocyte dysmorphology and mitochondrial dysfunction that manifests in preclinical models of heart failure and human patient alike29,30,31,32. Previous animal studies have demonstrated that cardiomyocyte-specific ablation of mitochondrial proteins that control mitochondrial energy metabolism, mitochondrial dynamics, or inter-organellar contacts with mitochondria trigger heart failure characterized by cardiomyocyte dysmorphology and dysfunction32,33,34,35,36,37. A transgenic mouse model with a cardiac-specific ablation of the mitochondrial peptidase YME1L showed mitochondrial fragmentation and progressive development of dilated cardiomyopathy, heart failure and reduced lifespan38. Similarly, mitochondrial complex I-deficient animals showed impaired systolic function and reduced cardiac output39. These mouse studies indicated that mitochondrial dysfunction in heart failure is not only a consequence, but rather a contributor to cardiac dysfunction. While mutations in mitochondrial genes can cause heart failure in a subset of patients with mitochondrial disease, they account for only a small portion of all inherited cardiomyopathies and of heart failure in humans40,41. Conversely, mitochondrial dysfunction is observed in cardiomyocytes from hearts with common cause of heart failure. Our data support the notion that altering cellular morphology and structural organization of human cardiomyocytes is sufficient to modulate mitochondrial energy metabolism, which helps reconcile the discrepancy between the abundance of mitochondrial dysfunction observed in idiopathic and non-mitochondrial inherited cardiac diseases and the paucity of primary mitochondrial mutations that result in cardiac dysfunction in humans. This would yield a model in which genetic, infectious, or chemical lesions that primarily disrupt cardiomyocyte architecture would lead to defects in mitochondrial bioenergetics. Our findings add to this concept by showing a sequence in which changes in mechanical constraints primarily lead to the disorganization of the mitochondrial network and impaired mitochondrial oxidation.

Finally, a metabolic switch away from fatty acid oxidation and towards glucose utilization is often observed in the failing heart42,43. Here, we found that organized micropatterned hiPSC-CMs had a higher metabolic preference for oxidation over glycolysis compared with non-patterned hiPSC-CMs, which had proportionally higher use of glycolysis. In addition, we found higher mitochondrial calcium uptake in the micro-patterned condition, while the expression of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) was unaffected. This could be supported by the increased integrity of MAMs, which are also known to facilitate lipid trafficking between the two organelles44 and mitochondrial calcium uptake27,28,45. Taken together our results indicate that architectural disorganization of the mitochondrial network in cardiomyocytes primarily leads to disruption of the MAMs, reduced lipid metabolism and calcium homeostasis and lower mitochondrial respiration. Consistently, nutritional interventions with high-fat diet in transgenic mice with the mutations associated with mitochondrial cardiomyopathies resulted in improved substrate utilization and regression of the dilated cardiomyopathy phenotype, while mitochondrial fragmentation was still observed38,46.

Our experimental model was designed to specifically study the role of geometric constraints on cardiomyocyte biology, which may be a limitation in recapitulating the complexity of pathological stimuli that occur during heart failure. While our approach does not replicate the sequential process of pathological remodeling seen in patients, it provides a controlled framework to investigate how differences in cellular architecture impact mitochondrial function and bioenergetics. Mitochondrial function is dependent on other stress factors such as ER stress, oxidative stress, or cell apoptosis. Future experiments combining our micropatterning approach with additional stressors will provide further insight into this issue.

In conclusion, architecture drives the efficiency of mitochondrial respiration in cardiomyocytes through a more efficient mitochondrial/sarcoplasmic structural organization and increased ion and lipid transfer.

Methods

hiPSC culture and maintenance

The human induced pluripotent stem cell SKiPSC-31.3 line from a healthy male adult volunteer, has been used here and was previously reported47,48,49,50. hiPSCs were seeded on stem cell-qualified Matrigel-coated (354277 Corning, Corning®, NY, USA) plates and maintained in mTeSRTM Plus medium (100-1130 STEMCell Technologies) in a humidified incubator (5% CO2, 37 °C). When reaching 70 to 80% confluency, cells were passaged in clumps by scraping with a pipette tip. Pluripotency was assessed by immunostaining and PCR with reverse transcription (RT-qPCR) (Supplementary Fig. 1) and routinely tested for mycoplasma. Genomic stability was assessed by the detection of recurrent genetic abnormalities using the iCS-digitalTM PSC test, provided as a service by Stem Genomics (https://www.stemgenomics.com/)51.

Cardiac differentiation

When hiPSCs reached a 90% confluency, differentiation was carried out according to a protocol adapted from Garg, et al.52. Briefly, mTeSRTM Plus was re-placed with RPMI-1640 supplemented with B27 supplement minus insulin (A18956-01 Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 6 µM CHIR-99021 (ab120890 Abcam) and maintained in a 5% CO2/air environment for 48 h. The medium was then changed to RPMI-1640/B27 minus insulin for 24 h and switched to RPMI-1640/B27 minus insulin supplemented with 5 µM IWR-1 (I0161 Sigma-Aldrich, St. Quentin Fallavier, France) for 48 h. On day 5, the medium was changed back to basal medium for 48 h. From day 7 onwards, cells were placed in RPMI-1640 with B27 supplement plus insulin (17504-044 Thermo Fisher Scientific). On day 11, beating hiPS-CMs were subjected to glucose starvation in RPMI-B27 without glucose (11879-020 Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 3 days. Cells were then dissociated using 0.05% trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min and seeded at 0.3 × 106 cells/cm2 in RPMI-1640/B27 plus insulin for 24 h. Then the cells were subjected to a second round of glucose starvation for 3 days. These two rounds of glucose starvation have been shown to increase dramatically the percentage of cardiomyocytes obtained15. By day 18, cells were cultured in RPMI-1640/B27 plus insulin and the medium was changed every two days.

Growing cells on micropatterned surface

18 mm round micropatterned coverslips were purchased from 4Dcell (Montreuil, France), with custom shape (repeated lines of 30 µm-width separated with a cell repellent). On day 35 hiPSC-CMs were seeded onto Matrigel-coated micropatterned coverslips at a density of 75 × 103 cells/cm2 for all experiments, except for seahorse assays, where a density of 125 × 103 cells/cm2 was used. Cells were then cultured for 7 to 10 days with RPMI-1640/B27 plus insulin at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. hiPSC-CMs cultured under standard unconstrained conditions were used as control (non-patterned condition).

Flow cytometry

hiPSC-CMs were dissociated into single cells with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA and stained with the fixable Zombie NIRTM Viability Kit (423105 BioLegend®) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Then, collected cell pellets were fixed and permeabilized using Inside Stain kit (130-090-477 Miltenyi Biotech) for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were incubated with fluorescent labeled antibodies (Supplementary Table 2) for 10 min at room temperature. Analysis was performed on BD Biosciences FACS LSR Fortessa X-20 instrument with at least 30,000 cells. Results were processed and plotted using FlowJo v10 software (FlowJo, LLC).

For quantification of mitochondrial content, mitochondria of dissociated non-patterned and micropatterned hiPSC-CMs (day 42) were stained using 200 nM MitoTrackerTM Green FM (M7514 Thermo Fisher Scientific). Live cells were incubated with the dyes in Ca2+/Mg2+-rich HBSS for 30 min at 37 °C and 5% CO2, followed by a PBS wash. Acquisition processing and analysis were performed as described above.

Immunostaining and imaging

hiPSC-CMs were cultured on Matrigel-coated micropatterned or standard unconstrained coverslips. After 1 week, cells were sequentially fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 10 min and then permeabilized and blocked with 0.5% Triton X-100, 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS (blocking solution) for 1 h. Subsequently, primary antibody incubation was performed overnight at 4 °C in 1:10 diluted blocking solution (Supplementary Table 2). Subsequently, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 546-conjugated goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Supplementary Table 2) for 1 h at room temperature and counter-stained with DAPI nuclear dye (1:10,000). Coverslips were mounted with Dako Faramount Aqueous Mounting (S3023 Agilent) and dried for 24 h. Fluorescent images were captured on a Cam mounted on a Leica TSC SP8 microscope. Image processing and analysis were performed using Fiji software.

Cell morphology and sarcomere organization metrics

The sarcomere structure of micropatterned hiPSC-CMs or non-patterned was labeled with alpha-actinin antibody. Fluorescent images were acquired using a Cam mounted on a Leica TSC SP8 microscope, and confocal images were processed using Fiji. Morphological features and internal organization of sarcomeres were analyzed with an adapted MATLAB interface of SarcOmere Texture Analysis (SOTA) coded by Sutcliffe, et al.17. A total of 120 to 150 cells were analyzed per condition from three independent experiments.

Mitochondrial morphology analysis

For mitochondrial network staining, live hiPSC-CMs from micropatterned or non-patterned condition (day 42) were labeled with 250 nM MitoTrackerTM Orange CMTMRos (M7510 Thermo Fisher Scientific) in RPMI-1640/B27 plus insulin for at least 45 min at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were then fixed and stained with alpha-actinin antibody as described above (Supplementary Table 2). Fluorescent images were captured on a Cam mounted on a Leica SPE microscope with a 63x oil (n = 1.3) objective. Z-stacks were deconvolved using Autoquant X software (MediaCybernetics, Bethesda, MD). Volumes of cells and individual mitochondrion were obtained with IMARIS software (Bitplane Company, Zurich, Switzerland), using Imaris MeasurementPro module. Fluorescence emitted from mitochondria was analyzed by the software allowing by surface segmentation methods, to identify individual objects corresponding to individual mitochondrion. Mitochondria segmented based on MitoTrackerTM intensity were subject to single cell-quantification of surface area and volume in IMARIS and data were exported and categorized in Excel.

The alignment of mitochondrial network was visualized from MitoTrackerTM Orange CMTMRos staining and confirmed using directionality analysis in Fiji software.

Mitochondrial DNA quantification

Mitochondrial DNA content was quantified as described previously32. Genomic and mitochondrial DNA was extracted with the NucleoSpin Tissue (740952 Macherey-Nagel) from micropatterned and non-patterned hiPSC-CMs. The relative content of mtDNA was detected by quantitative real-time PCR using mitochondrially encoded tRNA leucine 1 (MT-TL1) primers and normalized b-Actin. All primers are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Proteins extraction and Western Blotting

Total proteins were extracted from micropatterned or non-patterned conditions hiPSC-CMs (day 42) using RIPA buffer supplemented with a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (P8340, P5726, P0044, Sigma). Each sample was subjected to electrophoresis on 4–12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gradient gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and proteins were transferred to Nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-rad). After blocking with 5% non-fat milk, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 2). The next day membranes were incubated in secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Supplementary Table 2) at room temperature for 1 h. Finally, membranes were incubated with SuperSignal West Pico Plus Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 5 min and luminescence was detected using the Amersham ImageQuantTM 800. Vinculin or Histone H3 were used as loading control protein. Densiometric analysis of the immunoblots was performed using ImageQuantTL Software (v.10.1.401, Cytiva).

Mitochondrial and glycolysis bioenergetic analysis

hiPSC-CMs from micropatterned or non-patterned conditions (day 42) were seeded into VN-coated Seahorse 96 assay plates (Seahorse Bioscience, Agilent Technologies France, Les Ulis, France) at a density of approximately 30,000 cells/well and allowed to grow for 4 days in RPMI-1640/B27 plus insulin medium. Mitochondrial oxidation and glycolytic function were evaluated by analysis of oxygen consumption rate (OCR, pmol/min/µg of protein) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR, mpH/min/µg of protein) using the Seahorse XF96 extracellular flux analyser (Seahorse Bioscience), respectively. One hour prior, the culture medium was changed with the assay medium contained unbuffered DMEM supplemented with 10 mM glucose, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 2 mM L-glutamine for mitochondrial oxidation assay or 4 mM L-glutamine for glycolysis assay (all from Agilent). Cells were maintained at 37 °C without supplemental CO2 starting 1 h before assay. For the mitochondrial oxidation assay, OCRs were obtained from the slope change in oxygen concentration over time. After measurements of the baseline OCR, selective inhibitors were sequentially injected during the measurement (5 µM oligomycin, 1 µM FCCP and 1 µM antimycinA/rotenone, all from Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For normalization, cells were lysed in the XF96 plates using a protein lysis buffer (20 µL/well), and protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method.

For the glycolysis assay, Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR) was obtained from the slope of change in H+ concentration over time. After measurements of the baseline ECAR, selective inhibitors were sequentially injected during the measurements (10 mM glucose, 5 µM oligomycin, 50 mM 2-DG) following manufacturer’s instructions. All calculated values of ECAR parameters were normalized to quantified protein content.

Mitochondrial oxygen consumption

Mitochondrial respiration was measured in digitonin-permeabilized hiPSC-CMs from micropatterned or non-patterned conditions (day 42) in an Oxygraph high-resolution respirometer chamber (Oroboros Oxygraph-2k, Innsbruck, Austria). Briefly, hiPSC-CMs were dissociated into single cells, counted, and washed with 1 mL of R solution (2.77 mM CaK2EGTA, 7.23 mM K2EGTA, 1.38 mM MgCl2, 3 mM KH2PO4·H2O, 20 mM imidazole, 20 mM taurine, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 90 mM K-methanesulfonate, 10 mM Na-methanesulfonate, 2 g/L FFA-free BSA; pH 7.1). After centrifugation, cells were transferred to 540 µL of R solution and inserted into chamber (O2k-sV-Module) to determine the rates of oxygen consumption at 37 °C with continuous stirring as previously described53. Reagents were added into the closed chamber using Hamilton syringes (Oroboros Instruments). For permeabilization of the cell membrane, 10 µg/ml of digitonin (Sigma) was added to the chamber at the start of the protocol until leak respiration (L) is stabilized. Mitochondrial electron transfer capacity (ECT) was then assessed following the sequential addition of 1 mM pyruvate/4 mM malate, 2 mM ADP, 10 mM succinate, 2 mM amytal, 10 µM oligomycin, and 0.5 mM TMPD combined with 2 mM ascorbate (all from Sigma-Aldrich). The respiration rates were expressed in attomoles of O2 per second per cell.

Duolink® proximity ligation in situ assay

Duolink® in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) enables the detection, visualization, and quantification of protein-protein interactions ( < 40 nm) as individual fluorescent dots by microscopy. Cell fixation and permeabilization were performed as described for immunostaining. Blocking (1 h at RT) and incubation with primary (Supplementary Table 2) and secondary antibodies (1/5, 1 h at 37 °C) using anti-rabbit MINUS (DUO92005) and anti-mouse PLUS (DUO92001) kits, followed by ligation and amplification steps using the detection reagents orange kit (DUO92007), were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Sigma-Aldrich). Coverslips were counter-stained with DAPI nuclear dye (1:10,000) and mounted with Dako Faramount Aqueous Mounting. Fluorescence was analysed on a Leica TSC SP8 microscope, 8-10 fields per condition for each experiment were acquired and the number of interactions per cell was then analyzed using Fiji software.

Fluorescence intensity detection of Rhod-2 AM

Live hiPSC-CMs from micropatterned or non-patterned condition (day 42) were simultaneously loaded with 2.5 µM Rhod-2 AM (HY-D0989 MedChemTronica) and 250 nM MitoTrackerTM Deep Red (M22426 Thermo Fisher Scientific) in RPMI-1640/B27 plus insulin for 1 h at room temperature in the dark to enhance loading of Rhod-2 AM into the mitochondria54,55. To allow for de-esterification, cells were washed in 1.8 mM CaCl2 Tyrode solution for at least 30 min at 37 °C prior to imaging. Images were captured using a 40 x objective on a Leica TCS SP8 LSCM at 37 °C incubation where Rhod-2 fluorescence was recorded by excitation at 552 nm and measurement of the emitted light at 562-610 nm. MitoTracker was excited at 638 nm and fluorescence emission at 648-700 nm. Each recording was made using electric filed stimulation at 1 Hz with the C-dish electrode plate (CLD12WF Ionoptix). Postacquisition analyses of mitochondrial [Ca2+] were performed on Fiji software by creating an image mask of the mitochondrial staining and applying this mask on the Rhod-2 staining to obtain the mean fluorescence intensity on a standardized region of interest.

Transcriptomic analysis

We used hiPSC cells, non-patterned and micropatterned hiPSC-CMs at 42 days of differentiation to perform RNA-sequencing. Total RNA was extracted with a NucleoSpin RNA mini Kit (740955 Macherey-Nagel), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Library prep and RNA sequencing were conducted by Integragen as described below.

Quantification of gene expression

STAR was used to obtain the number of reads associated to each gene in the Gencode v31 annotation (restricted to protein-coding genes, antisense and lincRNAs). Raw counts for each sample were imported into R statistical software. The extracted count matrix was normalized for library size and coding length of genes to compute FPKM expression levels.

Unsupervised analysis

The Bioconductor edgeR package was used to import raw counts into R statistical software and compute normalized log2 CPM (counts per millions of mapped reads) using the TMM (weighted trimmed mean of M-values) as normalization procedure. The normalized expression matrix from the 1000 most variant genes (based on standard deviation) was used to classify the samples according to their gene expression patterns using principal component analysis (PCA), hierarchical clustering and consensus clustering. PCA was performed by FactoMineR::PCA function with “ncp = 10, scale.unit = FALSE” parameters. Hierarchical clustering was performed by stats::hclust function (with Euclidean distance and ward.D method). Consensus clustering was performed by ConsensusClusterPlus::ConsensusClusterPlus function to examine the stability of the clusters. We established consensus partitions of the data set in K clusters (for K = 2, 3, …, 8), on the basis of 1,000 resampling iterations (80% of genes, 80% of sample) of hierarchical clustering, with Euclidean distance and ward.D method. Then, the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of the consensus matrices were used to determine the optimal number of clusters (K = 3 for instance), considering both the shape of the functions and the area under the CDF curves.

tSNE analysis was performed with the Bioconductor Rtsne package applied to the PCA object (theta=0.0, perplexity = , max_iter=1000).

Differential expression analysis

The Bioconductor edgeR package was used to import raw counts into R statistical software. Differential expression analysis was performed using the Bioconductor limma package and the voom transformation. To improve the statistical power of the analysis, only genes expressed in at least one sample (FPKM >=) were considered. A qval threshold of <= 0.05 and a minimum fold change of 1.2 were used to define differentially expressed genes.

Differential pathway analysis

Differential pathway analysis was performed with the ReactomeGSA browser using the PADOG algorithm (Reactome version 82 on Nov, 2022). PADOG: Pathway Analysis with Down-weighting of Overlapping Genes (PADOG) computes a gene set score based on gene weights designed to emphasize the genes appearing in few gene sets, versus genes that appear in many gene sets (uniqueness of genes)56. Differentially expressed pathways with an adjusted p-value below 0.05 were considered significantly regulated.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA preparations were extracted with the NucleoSpin RNA Kit (740955 Macherey-Nagel) from the cells and quantified using a NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific). One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the SuperScript™ IV VILO™ kit (11756050 Thermo Fisher Scientific) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using amplified cDNA, gene-specific primers, and a SYBR Select Master Mix (4472908 Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). RPL32 was used as the housekeeping gene. The relative gene expression was calculated by the 2^ − ΔΔCT method. All primers are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Transmission electron microscopy

The cells were fixed by addition of glutaraldehyde (G5882 Sigma-Aldrich) in RPMI-1640-B27 with insulin media (final concentration 2.5% glutaraldehyde) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by a second fixation with 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer overnight at 4 °C. Fixed cells were washed three times with PBS. A post-fixation was performed for 1 h in a reduced osmium solution containing 1% osmium tetroxide, 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide in PBS 1x followed by incubation with a 1% thiocarbohydrazide solution in water for 20 min at room temperature, followed by 1% aqueous uranyl acetate at 4 °C overnight. The samples were then subjected to en bloc Walton’s lead aspartate staining and placed in a 60 °C oven for 30 min. Then samples were dehydrated in graded series of ethanol for 10 min each. The samples were infiltrated with 50% Agar low viscosity resin (Agar Scientific Ltd) for 2 h and 100% Agar low viscosity resin overnight. The resin was then changed by 100% Agar low viscosity for 1 h, two times and the samples were further incubated for 1 h before polymerization for 18 h at 60 °C. Sections with a thickness of 70 nm were cut using an EM UC6 ultramicrotome (Leica) and collected on formvar coated copper slot grids. Sections were observed at 120 kV with a Tecnail12 transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a 4Kx4K Oneview camera (Gatan). A set of images were taken at x2900 magnification for both conditions (10 images per replicate, with 3 replicates per condition). The segmentation of mitochondria and contact sites between mitochondria and sarcoplasmic reticulum was performed manually for each condition using IMOD software. On average, about ten representative mitochondria per image were segmented. Quantitative parameters from models were extracted using IMOD imodinfo prior to statistical analysis57.

Statistics and reproducibility

All numerical results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests were used for normally distributed data, with Welch’s correction applied when variances were unequal; Mann–Whitney U tests were used otherwise. Paired data were analyzed with Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. For multiple group comparisons, one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s or Sidak’s post-hoc tests were used when assumptions of normality were met, or Kruskal–Wallis tests with Dunn’s correction otherwise. P < 0.05 were considered significant for all statistical tests. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software (V10.3.0).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The RNA-Seq data used in this study are available in the NCBI GEO, accession number GSE303313. Uncropped blot images are available in the Supplementary Fig. 9. Source data underlying the graphs and charts in the main figures are provided in Supplementary Data 1. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Buckberg, G., Hoffman, J. I., Mahajan, A., Saleh, S. & Coghlan, C. Cardiac mechanics revisited: the relationship of cardiac architecture to ventricular function. Circulation 118, 2571–2587 (2008).

Dhein, S. et al. Remodeling of cardiac passive electrical properties and susceptibility to ventricular and atrial arrhythmias. Front Physiol. 5, 424 (2014).

Zimmermann, W. H. Biomechanical regulation of in vitro cardiogenesis for tissue-engineered heart repair. Stem Cell Res Ther. 4, 137 (2013).

Bray, M. A., Sheehy, S. P. & Parker, K. K. Sarcomere alignment is regulated by myocyte shape. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 65, 641–651 (2008).

Bursac, N., Parker, K. K., Iravanian, S. & Tung, L. Cardiomyocyte cultures with controlled macroscopic anisotropy: a model for functional electrophysiological studies of cardiac muscle. Circ. Res. 91, e45–e54 (2002).

Maron, B. J. & Maron, M. S. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet 381, 242–255 (2013).

Maron, B. J., Wolfson, J. K. & Roberts, W. C. Relation between extent of cardiac muscle cell disorganization and left ventricular wall thickness in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 70, 785–790 (1992).

van der Bel-Kahn, J. Muscle fiber disarray in common heart diseases. Am. J. Cardiol. 40, 355–364 (1977).

Finocchiaro, G. et al. Arrhythmogenic potential of myocardial disarray in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: genetic basis, functional consequences and relation to sudden cardiac death. Europace 23, 985–995 (2021).

Nollet, E. E. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is linked to cardiomyocyte architecture disruption and corrected by improving NADH-driven mitochondrial respiration. Eur. Heart J. 44, 1170–1185 (2023).

Thery, M. Micropatterning as a tool to decipher cell morphogenesis and functions. J. Cell Sci. 123, 4201–4213 (2010).

Salick, M. R. et al. Micropattern width dependent sarcomere development in human ESC-derived cardiomyocytes. Biomaterials 35, 4454–4464 (2014).

Ribeiro, A. J. et al. Contractility of single cardiomyocytes differentiated from pluripotent stem cells depends on physiological shape and substrate stiffness. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 12705–12710 (2015).

Lian, X. et al. Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical Wnt signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E1848–E1857 (2012).

Sharma, A. et al. Derivation of highly purified cardiomyocytes from human induced pluripotent stem cells using small molecule-modulated differentiation and subsequent glucose starvation. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/52628 (2015).

Lundy, S. D., Zhu, W. Z., Regnier, M. & Laflamme, M. A. Structural and functional maturation of cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 22, 1991–2002 (2013).

Sutcliffe, M. D. et al. High content analysis identifies unique morphological features of reprogrammed cardiomyocytes. Sci. Rep. 8, 1258 (2018).

Szabadkai, G. et al. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J. Cell Biol. 175, 901–911 (2006).

Paillard, M. et al. Depressing mitochondria-reticulum interactions protects cardiomyocytes from lethal hypoxia-reoxygenation injury. Circulation 128, 1555–1565 (2013).

Tubbs, E. & Rieusset, J. Study of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria interactions by in situ proximity ligation assay in fixed cells. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/54899 (2016).

Lee, S. & Min, K. T. The interface between er and mitochondria: molecular compositions and functions. Mol. Cells 41, 1000–1007 (2018).

Burchfield, J. S., Xie, M. & Hill, J. A. Pathological ventricular remodeling: mechanisms: part 1 of 2. Circulation 128, 388–400 (2013).

Guo, Y. & Pu, W. T. Cardiomyocyte maturation: new phase in development. Circ. Res. 126, 1086–1106 (2020).

Al Sayed, Z. R. et al. Rod-shaped micropatterning enhances the electrophysiological maturation of cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 19, 1417–1431 (2024).

Vance, J. E. MAM (mitochondria-associated membranes) in mammalian cells: lipids and beyond. Biochim Biophys. Acta 1841, 595–609 (2014).

van Vliet, A. R., Verfaillie, T. & Agostinis, P. New functions of mitochondria associated membranes in cellular signaling. Biochim Biophys. Acta 1843, 2253–2262 (2014).

Patergnani, S. et al. Calcium signaling around Mitochondria Associated Membranes (MAMs). Cell Commun. Signal 9, 19 (2011).

Marchi, S., Patergnani, S. & Pinton, P. The endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria connection: one touch, multiple functions. Biochim Biophys. Acta 1837, 461–469 (2014).

Civiletto, G. et al. Opa1 overexpression ameliorates the phenotype of two mitochondrial disease mouse models. Cell Metab. 21, 845–854 (2015).

Song, M., Mihara, K., Chen, Y., Scorrano, L. & Dorn, G. W. Mitochondrial fission and fusion factors reciprocally orchestrate mitophagic culling in mouse hearts and cultured fibroblasts. Cell Metab. 21, 273–286 (2015).

Antonicka, H. et al. Mutations in COX15 produce a defect in the mitochondrial heme biosynthetic pathway, causing early-onset fatal hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet 72, 101–114 (2003).

Donnarumma, E. et al. Mitochondrial Fission Process 1 controls inner membrane integrity and protects against heart failure. Nat. Commun. 13, 6634 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Mitofusin 2-containing mitochondrial-reticular microdomains direct rapid cardiomyocyte bioenergetic responses via interorganelle Ca(2+) crosstalk. Circ. Res. 111, 863–875 (2012).

Ikeda, Y. et al. Endogenous Drp1 mediates mitochondrial autophagy and protects the heart against energy stress. Circ. Res. 116, 264–278 (2015).

Narula, N. et al. Adenine nucleotide translocase 1 deficiency results in dilated cardiomyopathy with defects in myocardial mechanics, histopathological alterations, and activation of apoptosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 4, 1–10 (2011).

Ahola, S. et al. OMA1-mediated integrated stress response protects against ferroptosis in mitochondrial cardiomyopathy. Cell Metab. 34, 1875–1891.e1877 (2022).

Song, M., Franco, A., Fleischer, J. A., Zhang, L. & Dorn, G. W. 2nd. Abrogating mitochondrial dynamics in mouse hearts accelerates mitochondrial senescence. Cell Metab. 26, 872–883.e875 (2017).

Wai, T. et al. Imbalanced OPA1 processing and mitochondrial fragmentation cause heart failure in mice. Science 350, aad0116 (2015).

Ke, B. X. et al. Tissue-specific splicing of an Ndufs6 gene-trap insertion generates a mitochondrial complex I deficiency-specific cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 6165–6170 (2012).

Gorman, G. S. et al. Mitochondrial diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2, 16080 (2016).

Suomalainen, A. & Nunnari, J. Mitochondria at the crossroads of health and disease. Cell 187, 2601–2627 (2024).

Neubauer, S. The failing heart–an engine out of fuel. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 1140–1151 (2007).

Lopaschuk, G. D., Karwi, Q. G., Tian, R., Wende, A. R. & Abel, E. D. Cardiac energy metabolism in heart failure. Circ. Res. 128, 1487–1513 (2021).

Degechisa, S. T., Dabi, Y. T. & Gizaw, S. T. The mitochondrial associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes: a platform for the pathogenesis of inflammation-mediated metabolic diseases. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 10, e647 (2022).

Marchi, S. et al. Mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum calcium homeostasis and cell death. Cell Calcium 69, 62–72 (2018).

Southwell, N. et al. High fat diet ameliorates mitochondrial cardiomyopathy in CHCHD10 mutant mice. EMBO Mol. Med. 16, 1352–1378 (2024).

Galende, E. et al. Amniotic fluid cells are more efficiently reprogrammed to pluripotency than adult cells. Cell Reprogram 12, 117–125 (2010).

Karakikes, I. et al. Small molecule-mediated directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells toward ventricular cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 3, 18–31 (2014).

Vermersch, E. et al. hsa-miR-548v controls the viscoelastic properties of human cardiomyocytes and improves their relaxation rates. JCI Insight 9, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.161356 (2024).

Seguret, M. et al. A versatile high-throughput assay based on 3D ring-shaped cardiac tissues generated from human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Elife 12, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.87739 (2024).

Assou, S. et al. Recurrent genetic abnormalities in human pluripotent stem cells: definition and routine detection in culture supernatant by targeted droplet digital PCR. Stem Cell Rep. 14, 1–8 (2020).

Garg, P. et al. Genome editing of induced pluripotent stem cells to decipher cardiac channelopathy variant. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 62–75 (2018).

Kuznetsov, A. V. et al. Analysis of mitochondrial function in situ in permeabilized muscle fibers, tissues and cells. Nat. Protoc. 3, 965–976 (2008).

Kosmach, A. et al. Monitoring mitochondrial calcium and metabolism in the beating MCU-KO heart. Cell Rep. 37, 109846 (2021).

Cyganek, L. et al. Deep phenotyping of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes. JCI Insight 3, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.99941 (2018).

Griss, J. et al. ReactomeGSA—efficient multi-omics comparative pathway analysis. Mol. Cell Proteom. 19, 2115–2125 (2020).

Kremer, J. R., Mastronarde, D. N. & McIntosh, J. R. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 116, 71–76 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the French National Research Agency (NADHeart ANR-17-CE17-0015-02, NADINCARD ANR-22-CE92-0034-02), the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (EQU201903007852), and by a grant from the Leducq Foundation (18CVD05). This work benefited from expertise and support from the iPSC technical facility at PARCC. We thank Camille Knops and Yunling Xu from the Flow Cytometry and the Microscopy platforms, respectively, from Université de Paris Cité, Paris Cardiovascular Research Center, Paris, France. We thank the ImagoSeine core facility of Institut Jacques Monod, member of France-BioImaging (ANR-10-INBS-04) and GIS-IBiSA, and Catherine Durieu for her help in the TEM analysis. We thank Daniel Balvay for his help with Rhod-2 image quantification. We would also like to thank Jérome Piquereau and Valérie Nicolas for helpful assistance with IMARIS analysis. We thank 4Dcell staff for the discussion about the cell repellent and design of the linear-shaped micropatterns. We thank Karima Ichegour for excellent administrative assistance. Figures 1A, 5C and S7C were Created in BioRender, with the following publication licence: Hulot, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/y8s4cj8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.J., A.R.-V., E.D., R.L-B., I.M., C.P., M.S., E.VH., E.VT., and I.N. performed the experiments, acquired and interpreted the data. C.J. performed the metabolic experiments with the help of I.M., C.P., and I.N.; A.R.-V. performed bioinformatics analysis on the transcriptome data. E.D. and E.VT. performed the quantifications on mitochondria proteins. R.L-B. and J-M.V. performed the TEM experiments and analyses. T.W., L.B., and M.M. reviewed the manuscript and helped in interpreting the data. J.-S. H designed the study, acquired the fundings, supervised the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript with C.J.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.S.H. has received speaker, advisory board or consultancy fees from Alnylam, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Boerhinger Ingelheim, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, all unrelated to the present work. Other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Luca Scorrano and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Dario Ummarino. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jouve, C., Ruiz-Velasco, A., Donnarumma, E. et al. Myocardial disarray drives metabolic inefficiency in human cardiomyocytes. Commun Biol 8, 1445 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08842-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08842-x