Abstract

5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) is a stable epigenomic mark associated with gene regulation and tumorigenesis. To evaluate its potential for multi-cancer detection, epigenomic distribution of 5hmC was analyzed in tumor tissues (n = 217), normal tissues (n = 50), and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from cancer (n = 1009) and non-cancer subjects (n = 1678) across breast, colon, lung, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers. Differential analysis revealed extensive redistribution of 5hmC in early-stage tumors that persisted into the late-stage, while global 5hmC abundance decreased in all tumors. Two distinct patterns of hydroxymethylation distribution were identified: one common across cancers and another tissue specific. Differential hydroxymethylation regions (DhmRs) that were tumor tissue specific had significantly improved cancer prediction in cfDNA. A multinomial logistic regression model was trained on tissue-specific DhmRs to predict Tissue of Tumor Origin (TOTO) of cfDNA with 85.2% accuracy. These findings demonstrate that stable, cancer-specific 5hmC signatures appear to be established early in tumorigenesis persist throughout disease progression, suggesting 5hmC as a potential pan-cancer marker for early and late-stage tumor detection via liquid biopsy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

DNA 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and its oxidized form, DNA 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) are prevalent epigenetic markers that play crucial roles in regulating gene expression within the human genome1. 5mC is commonly associated with regions that are transcriptionally inactive, while 5hmC levels in gene bodies and enhancers are strongly correlated with transcriptional activity2,3,4. Recent technical advances have enabled the characterization of 5mC and 5hmC distribution in the human genome across different tissue origins2,5,6. Analysis of 5mC patterns has identified methylation signatures in cell free DNA (cfDNA) that correlate with a number of cancers at various stages, inspiring the development of a multi-cancer screening test7,8,9. Various biotechnology applications have demonstrated promising result in predicting the tissue of tumor origin (TOTO) based on methylation signatures in cfDNA analyte10; however, no study as of date has investigated the correlation of 5hmC signals in tumor tissues and cancer cfDNA on a genomic scale.

Ongoing studies have continued to contribute to our understanding of 5hmC modifications in regulating transcriptional dynamics during cellular, developmental, and pathological processes2,11. In particular, tissue-specific genomic variation of 5hmC levels have been observed in the course of normal tissue development as well as during tumorigenesis12. It is thought that bloodborne cfDNA are partially digested DNA fragments that originate from tissues and circulatory blood cells, creating a mixture of DNA with epigenomic patterns that can reflect their cellular origins. This complex mixture has been shown to be a dynamic representation of tissue health within the body, enabling routine screening tests due to its availability and ease of access13,14. By isolating 5hmC-modified cfDNA fragments from blood plasma, several studies have identified 5hmC patterns that are associated with distinct cancer types and demonstrated the feasibility in constructing a predictive model for classifying cancer patients15,16,17,18. However, it remains unclear the extent to which the genomic distribution of 5hmC in cfDNA reflects their tumor tissue origins. Investigation of tissue-specific 5hmC patterns in tumor and normal tissues can thereby reveal cancer-specific features that forms the basis of a multi-cancer prediction test based on cfDNA profiling, in addition to elucidating the physiological changes that underlie different types of cancer formation.

This study expands on previous work to elucidate differences in 5hmC dynamics between tumor and normal tissues and their relationship to 5hmC dynamics in cfDNA. The stability of tumor tissue-specific 5hmC patterns was assessed across all disease stages. To determine the extent to which 5hmC features in cfDNA reflect the tumor tissue of origin, the concordance of differential hydroxymethylation regions (DhmRs) was quantified between tissues and cfDNA across different cancer types. We present a proof of concept approach for the prediction of TOTO in cfDNA samples by implementing a two-step prediction model based on tissue-specific 5hmC features. First, a binomial model was trained to distinguish cancer and non-cancer status in cfDNA samples. Second, a multinomial model leveraging tumor tissue-derived features was trained to predict TOTO in cancer-positive cases. Cross-fold validation of the final model indicates promising predictive accuracy in cfDNA samples, highlighting the potential of 5hmC measurements for future clinical applications in multi-cancer diagnostics.

Methods

Clinical cohorts and study design of tumor tissues

Fresh-frozen malignant and benign tissue samples (267) representing five tissue types (breast, colon, lung, ovary, and pancreas) were obtained by autopsy or surgery from individual donors. Of the total 267 specimens, 50 samples were taken from benign tissues as follows: 28 were benign tissues from healthy patients and 22 were benign tissue adjacent to the tumor tissues (NAT) from cancer patients. For colon, lung, and pancreas tissues, donor biological sex is balanced (54% male, 46% female). All tissue donors were adults of European ancestry with an average age of 62 years old (range 22–91). For a more detailed breakdown of donor information, please refer to Supplemental Table 1. Patient samples were obtained through a combination of prospective collections and pre-existing biorepository materials. Specifically, samples collected by contract research organizations (CROs) were prospectively acquired under institutional review boards (IRB)-approved protocols for this study. In contrast, samples obtained from biorepository vendors were pre-collected under IRB-approved protocols and made available for research use. All specimens were de-identified prior to transfer to ClearNote Health. Tissue samples were obtained from MT Group (Sterling IRB), iProcess Global (Advarra IRB), Crown Biosciences, and DX Biosamples. Each organization operated under IRB-approved protocols with informed consent or under an IRB-approved waiver of consent, as applicable. Per contractual agreements, sites using local IRBs (Crown Biosciences and DX Biosamples) could not disclose IRB names to ClearNote Health to preserve blinding. All vendors obtained IRB approval and informed consent from participants for research use. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

Clinical cohorts and study design of cfDNA samples

Cancer (n = 1009) and non-cancer control (n = 1678) cfDNA samples used in this study were derived from subjects that were recruited into a case-control study (NCT03869814) from June 2018 to May 2022 across 146 sites in the United States. All subjects provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the institutional review boards responsible at each site. The study protocol submission, institutional review board approval, and specimen handling across all sites were managed by several CROs as mentioned previously. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed. Details related to inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in the NCT03869814 trial page on www.clinicaltrials.gov and more details are provided in the Supplementary Methods from a previous publication19. Whole blood specimens were obtained by routine venous phlebotomy at the time of enrollment. Whole blood (2 × 10 mL) was collected in cell-free DNA (cfDNA) BCT tubes (Streck, La Vista, NE) per manufacturer’s protocol and maintained at 15–25 °C for shipment to the laboratory and processed within 72 h of venipuncture. To separate plasma, tubes were centrifuged at 1600 × g for 10 min, and the plasma was transferred to new tubes for further centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min. The final plasma was aliquoted for frozen storage at −80 °C before cfDNA isolation.

DNA processing and library construction

All tissue samples were stored in H media for the interval between surgical resection and laboratory processing. Each sample was weighed and aliquoted into sections of approximately 35 mg. Each resulting subsection was briefly incubated on dry ice, then homogenized in 500 µl RLT Buffer Plus using a Tissue Lyser LT (QIAGEN Germantown, MD) at 50 Hz for 2 min. Resulting homogenates were stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer instructions. Genomic DNA (gDNA) eluates were quantified using the Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and stored at −20 °C until further processing. Prior to sequencing library construction, gDNA was fragmented to a modal 150 base pair size using an ME220 focused ultrasonicator (Covaris, Woburn, MA). Modal fragmented DNA sizes were quantified using the TapeStation 2200 dsDNA high sensitivity assay (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Plasma sample preparation and cfDNA isolation were described previously19. DNA were normalized to 10 ng (plasma cfDNA) or 20 ng (tissue gDNA) input amount prior to library construction. Protocols to prepare 5hmC-enriched and whole genome sequencing libraries were described previously19.

DNA sequencing and read alignment

DNA sequencing was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations with 75 base-pair, paired-end sequencing using a Novoseq 6000 instrument with version 2 reagent chemistry (Illumina, San Diego, CA) on either S1 or S2 flow cell. Sequencing data were collected with NovaSeq Control Software v1.7.0 (Illumina). Raw data processing and demultiplexing was performed using the Illumina BaseSpace Sequence Hub to generate sample-specific FASTQ output. Sequencing reads were aligned to the human GRCh38 (hg38) genome reference using BWA-MEM2 (v2.2.1) with default parameters20. Sequencing data quality was assessed using Picard. The quality control ensures that each sample has: (1) greater than 107 unique fragments; (2) less than 30% duplicated fragments (fragments with identical start and end alignment coordinates); (3) less than 6.4% fragments with no CpG dinucleotide in the 5hmC-enriched library; (4) less than 800 genes with no overlapping fragments. Any sample that failed to meet these quality control metrics were excluded from the analysis. To mitigate the effect of PCR bias, we “de-duplicated” fragments that share identical genomic start and end sites for all downstream analyses. To mitigate sex-dependent bias, we removed fragments that did not map to the autosomal regions (chromosome 1–22).

Peak detection

BWA-MEM2 (v2.2.1)20 read alignments were employed to identify regions or peaks of dense read accumulation that mark the location of a hydroxymethylated cytosine residue. Prior to identifying peaks, BAM files containing the locations of aligned reads were filtered for poorly mapped (MAPQ < 30) and unpaired reads using samtools and HTSlib. 5hmC peak calling was carried out using MACS2 (v2.1.1.20160309) (https://github.com/taoliu/MACS)21 with a p value cut off = 10−5. Identified 5hmC peaks residing in “blacklist regions” as defined elsewhere (https://sites.google.com/site/anshulkundaje/projects/blacklists) and residing on chromosomes X, Y, and the mitochondrial genome were also removed using bedtools (v2.27.1) (https://github.com/arq5x/bedtools2)22. Genomic annotation and enrichment analysis of 5hmC peaks were performed using the Homer (v4.11) toolkit (http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/)23 with default parameters.

Differential hydroxymethylation analysis

To perform differential hydroxymethylation region (DhmR) analysis, we performed data pre-processing and model fitting using R (v4.1.2) package “edgeR” (v3.36) (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/edgeR.html)24 as follows: (1) filter for features that had greater than 3 CPM (counts per million) in at least 8 samples; (2) calculate normalization factors; (3) estimate dispersions; (4) fit the data to a generalized linear model (“glmFit”); (5) perform likelihood ratio test (“glmLRT”) to evaluate significant differences between two groups; (6) apply Benjamini’s and Hochberg’s procedure25 to correct for multiple hypothesis testing and to quantify false discovery rate (FDR). In this article, we use the words “adjusted p value” and “FDR” interchangeably. In comparing early- and late-stage samples, we excluded cancer samples that had unknown stage information from the analysis (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for a detailed numerical breakdown).

Low dimensional embedding of gene body 5hmC levels in tissue samples

To project the samples onto a lower dimensional embedding, we first filtered out genes that have zero read count in any sample, and then standardized the CPM normalized read count to be mean centered with unit variance. We applied principal components analysis to the rescaled count matrix and kept the top 50 principal components as input to Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP)26, yielding a two-dimensional embedding of 5hmC distributions in tissue samples. Sample processing for dimensionality reduction was performed using the Scanpy package (v1.8.2) in Python (v3.9.13)27.

Tumor fraction estimate

To quantify the tumor fraction in each sample, we applied ichorCNA (https://github.com/broadinstitute/ichorCNA)28. Briefly, we constructed two panels of normal reference using either normal tissues or control cfDNA samples, with 1 Mb window size, GC wig file, mappability wig file, and centromere location files for hg38 provided by the package. Then we executed ichorCNA with default parameters on the whole genome sequencing library of each sample in cfDNA or tissue samples against the corresponding normal reference panel.

Identification of tissue variant genes

To identify tissue variant genes, raw gene counts in tumor (n = 217) and normal (n = 50) tissue samples were first normalized to CPM and log2 transformed. We then performed a two-way ANOVA to quantify the effect sizes of tissue type, cohort, and their interaction on the normalized 5hmC levels of each gene, with statistical significance evaluated by an F-test. Genes that had a significant tissue type effect (FDR < 0.05), but no significant cohort effect (tumor versus normal) and tissue/cohort interaction, were then selected. To further reduce noise, we removed genes that had high variability or high levels of 5hmC levels in an internal set of control cfDNA samples (n = 1691). Raw counts in these filtered genes were first transformed to FPKM in the control cfDNA sample set. Genes with mean FPKM above the 75th percentile and standard deviation greater than the 75th percentile were then removed. This resulted in the identification of 5268 tissue variant genes, available in Supplementary Data 1, which are used as input features for training the TOTO model.

Predictive modeling

To predict cancer and non-cancer samples, we built a logistic regression classifier with elastic net as implemented in the R package, glmnet29. Models were trained and evaluated using nested cross-fold validation, such that the data was first divided into 20 folds. For each fold, 95% of the data were set aside for model training and 5% of the data for performance evaluation (held-out set). During model training, we optimized the elastic net mixing ratio α and regularization parameter λ using only the training set (95% of the data) with five-fold cross-validation. Model performance was then assessed using the held-out set. Paired, two-sided DeLong test30 was used to compare the performance of two classifiers. To optimize the performance of the TOTO prediction model using tissue variant genes as features, the training samples were restricted to cfDNA plasma samples with a binomial cancer prediction score higher than the 99% specificity probability threshold. We trained multinomial logistic regression models similarly using R package glmnet and a 20-fold nested cross-validation strategy, where within each sub-fold, 95% and 5% of the data were used for training and testing. Performance of the model was evaluated using the left-out sample set in each outer loop. TOTO accuracies were calculated using the first-ranked prediction or both the first and second-ranked predictions.

5hmC mass fraction estimation

We constructed eight sets of amplicon spike-ins based on non-overlapping regions of lambda phage genome, with each amplicon being 150 bp in length. Each spike-in consists of plain and 5hmC containing DNA at various 5hmC percentages of 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 25, 50 or 100%. The final spike-in cocktail is a mixture of these eight-amplicon spike-ins with equal concentration. One picogram amount of the spike-in mixture was added to each sample after cfDNA extraction, and processed along with library preparation, PCR and sequencing for both 5hmC and WGS libraries. The lambda spike-ins with 5hmC modification are captured and detected in our 5hmC enrichment assay. The read count ratio of lambda spike-ins relative to the human cfDNA fragments is proportional to the concentration of spike-ins in the input DNA. Given that the input mass of spike-ins is a known quantity, we can calculate the mass fraction of human 5hmC cfDNA in each sample15:

\({r}_{H,{{\mathrm{hg}}}}\) and \({r}_{W,{{\mathrm{hg}}}}\) are the human fragment counts in the 5hmC and WGS library, respectively. \({\bar{L}}_{H,{{\mathrm{hg}}}}\) and \({\bar{L}}_{W,{{\mathrm{hg}}}}\) are the average length of human fragments in the 5hmC and WGS library, respectively. \({r}_{H,\lambda }\) and \({r}_{W,\lambda }\) are the read counts of lambda cocktail spike-in in the 5hmC and WGS library, respectively. \({M}_{\lambda }\) and \({m}_{\lambda }\) are the input mass of 5hmC modified and plain lambda spike-ins, respectively.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

To compute gene set enrichment scores, we ranked the genes based on fold change in 5hmC levels between groups and provided the rank order as input to Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (v4.2.3)31. Pre-ranked GSEA was executed with the following parameters: “mode = Abs_max_of_probes, norm = meandiv, nperm = 1000, rnk_seed = timestamp, scoring_scheme = weighted, set_max = 500, set_min = 15”. MSigDB gene sets (i.e., biological hallmark, c6 oncogenic pathways) were downloaded from the official GSEA website. To generate the concordance analysis result in Supplementary Data 2, we constructed custom gene sets by filtering for genes that are the most differential between tumor (n = 217) and normal (n = 50) tissues as determined by DhmR analysis: FDR less than 0.05 and absolute fold-change greater than 1.2. We then ranked these genes in descending order based on their average CPM levels across all tissue samples and created gene sets that consist of 50–500 of the top genes. This created a total of six gene sets which were tested for significant enrichment of DhmR genes in the cfDNA samples (cancer versus control). Pre-ranked GSEA was executed to compute the statistical significance and enrichment scores of each of the six custom gene sets to evaluate concordance in pan-cancer 5hmC signatures between tumor tissues and cancer cfDNA samples.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analysis can be reproduced with source data and code provided in the repository32. DhmR and GSEA statistical analysis can be reproduced following description provided in previous method sections. Multiple hypothesis correction has been calculated using Benjamini–Hochberg procedure whenever appropriate. A total of 217 tumor tissue and 50 normal tissue samples from across five tissues were analyzed. Each tissue had at least 10 normal tissue samples from different subjects. A detailed breakdown of the number of tumor samples in each tissue: Breast (n = 37), Colon (n = 63), Lung (n = 33), Ovary (n = 42), and Pancreas (n = 42). A total of 1009 cancer cfDNA samples and 1678 control cfDNA samples were analzyed. A detailed breakdown of the number of samples by cancer types: Breast (n = 89), Colon (n = 280), Lung (n = 346), Ovary (n = 91), and Pancreas (n = 203). Further details on sample size are available in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Genome profiling of 5hmC reveals tumor- and tissue-specific epigenetic changes

A total of 267 fresh frozen tissue samples representing 5 tissue types (breast, colon, lung, ovary, and pancreas) were collected from individual donors. The samples consist of both tumor tissues, normal tissues, as well as normal tissues adjacent to the tumor (NAT) and form the basis of a 5hmC tumor tissue reference atlas for the study (Supplemental Table 1; more clinical attributes available in Supplementary Data 3). This tissue atlas covers the 5 cancer types that are responsible for 45% of cancer-related mortality in the US33. 52.1% of the cancer samples are clinically diagnosed with early stage (I and II) disease. A breakdown of the patients by tissue type and cancer stage is shown in Supplemental Table 1. At least 10 non-cancer tissue samples were collected from each tissue type. These include both normal tissues from healthy patients and NAT from cancer patients. Genomic 5hmC signal was profiled using a click-chemistry based genome-wide method that enriches 5hmC-modified fragments in sheared genomic DNA (see “Methods”). Both 5hmC-enriched and non-enriched (WGS) libraries were sequenced to an average depth of 32.5 million read pairs (Supplementary Data 3). 5hmC signals were assessed and found to be not significantly different between normal and NAT samples based on hierarchical clustering, therefore both are referred to as “normal tissues” in the remainder of the article (Fig. S1A).

To quantify the absolute difference in global 5hmC abundance between tumor and normal tissue samples, we added a set of hydroxymethylated spike-ins with orthogonal sequences to human reads during the processing of each sample (see “Methods”) to measure the fraction of DNA that is hydroxymethylated (5hmC mass fraction). We found that tumor samples have decreased 5hmC mass fractions compared to normal samples across all tissues (Fig. 1A). Multi-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) results indicated that both cohort and tissue type had significant effects on 5hmC mass fraction (p « 0.001); while sex (p = 0.230) and age (p = 0.209) did not affect 5hmC mass fraction significantly. This is expected as age-dependent decrease of 5hmC levels occurs primarily before 40 years old34. Since most of our tissue cohort (~93%) is above 40 years old, we do not expect age to be a significant covariate in our analysis. Within tumor tissues, we performed linear regression of 5hmC mass fraction against age and detected no significant correlation between the two variables (adjusted R2 = 0.0068, one-sided F-test p = 0.230) (Fig. S1B).

A Boxplot of 5hmC mass fractions estimated from non-human spike-in control, with red and blue boxes indicating tumor (n = 217) and normal (n = 50) tissues, respectively. Two-group rank sum test significance shown as *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001. Center line represents median. Box bounds represent 25th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers are Tukey whiskers. B Proportion of 5hmC fragment peaks that mapped to genomic features. Outer and inner donut plots illustrate the proportions in normal and tumor tissues, respectively. C Boxplots of 5hmC peak enrichment across genomic features per tissue type in both tumor tissues (red) and normal tissues (blue). Peak enrichment values are calculated using Homer tools (see “Methods”). Center line represents median, bounds of box represent 25th and 75th percentiles and whiskers are Tukey whiskers. Two-group rank sum test significance of the enrichment value between tumor and normal tissues is shown as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. D MYC locus exhibits increased 5hmC signal intensity in tumor samples (colored tracks) compared to normal samples (gray tracks).

As reported previously, 5hmC is enriched in the promoter and gene body regions but depleted in transcription start sites (TSS) in normal tissues2. Given that hydroxymethylation is a marker for chromatin accessibility and transcriptional expression35,36, we wondered if a similar distribution of 5hmC is observed near the gene bodies in tumor tissues. After collapsing 5hmC-enriched fragments, we observed a similar pattern of 5hmC density near the gene body regions across different tissues, with 5hmC depleted at TSS and enriched in promoter and gene body regions (Fig. S1C). This suggests that the global difference in 5hmC abundance between tumor and normal tissues is likely driven by variation of 5hmC modification in a subset of the genomic features.

To obtain a detailed comparison of the 5hmC landscape between tumor and normal tissues, we identified 5hmC enriched loci, as measured by increased read density and subsequent peak detection by MACS2 (see “Methods”). On average, we detected 185,129 peaks in each tissue sample (Supplementary Data 3). Peaks were pooled together for all tumor and normal tissue samples after removing those that were detected in only one sample, leading to a total of distinct 1,134,610 peaks. Most peaks were located in SINE, intron, intergenic, and LINE regions, with less than 10% of the peaks detected in exon and promoter regions (Fig. 1B); however, after accounting for the random distribution of regions across the genome, we found that 5hmC density was significantly enriched in genic regions (e.g., exons, promoters, and CpG islands) in both tumor and normal tissues. To evaluate the difference between tumor and normal tissues, we computed the statistical significance in 5hmC peak enrichment between the two groups for each genomic feature (Fig. 1C). Our analysis showed genic regions (3UTR, TTS, Exon, CpG Island, and Promoter) were significantly more hypo-hydroxymethylated in tumor tissues than in normal tissues; however, non-genic regions (LINE and Intergenic) showed the opposite trend and were significantly hyper-hydroxymethylated in tumor tissues (Fig. 1C). Some genes known to be epigenetically regulated in cancer context showed significant differences in 5hmC density between tumor and normal tissues. For example, MYC, a gene over-expressed in cancer, was hyper-hydroxymethylated in tumor tissues37 (Fig. 1D), while GATA4, a tumor suppressor gene frequently silenced in cancer, was hypo-hydroxymethylated8 (Fig. S1D).

5hmC changes in gene bodies reveal tissue-concordant and tissue-specific changes during tumorigenesis

Comparisons of 5hmC occupancy in the gene bodies between tumor and normal tissues can capture epigenomic changes that are tissue-specific or tissue-concordant. After removing weakly represented genes (see “Methods”), we included a total of 17,521 genes for differential hydroxymethylation region (DhmR) analysis. In contrast to measuring absolute abundance, DhmR analysis quantifies the change in relative density of 5hmC in gene bodies between tumor and normal tissues. Through DhmR analysis, we identified genes with significant difference in 5hmC occupancy between tumor and normal tissues in each tissue type (FDR < 0.05, Fig. 2A). Across all tumor tissues, a greater number of genes was found to increase in 5hmC occupancy, suggesting that 5hmC density was re-distributed in gene bodies during tumorigenesis. DhmR analysis identified marker genes for cell types that are known to undergo significant alterations in pancreatic tumors (Fig. S1E), implicating the role of 5hmC re-modulation in their pathophysiology38.

A Log2 fold-change (FC) of hydroxymethylation levels in gene features are compared as a function of their average log2 counts per millions (CPM) between tumor (n = 217) and normal (n = 50) samples for each tissue type. Red and blue colors denote significant hyper or hypo-differentially hydroxymethylated region (DhmR) genes with FDR (Benjamini–Hochberg method) less than 0.05, respectively. Numbers on the top and bottom of the plots reflect the number of DhmR genes. B Pairwise linear regression analysis of tumor (n = 217) versus normal (n = 50) log2 fold change in each tissue type, or all tissue types in aggregate. Coefficients of determination and best fit regression models are shown for each pairwise comparison. Distributions of fold change are shown in the off-diagonal panels. Five-way Venn diagram shows the intersect of DhmR genes with concordant hyper-hydroxymethylation (C) or hypo-hydroxymethylation (D) between tumor and normal samples among the five tissue types. E GSEA of biological hallmark pathway based on log2 fold change of 5hmC level in all genes between tumor and normal samples across five tissue types (columns) or all tissue types in aggregate (all). Color reflects normalized enrichment score (NES).

To assess the concordance of 5hmC changes between different tumor types, we performed pairwise analysis of log2 fold change (tumor versus normal) for all 17,521 genes across five tumor types and all tumor vs all normal (Fig. 2B). Strikingly, all tumor tissues shared significant correlations amongst each other, except for pancreatic tumor which exhibited the lowest correlation with respect to other tumor tissue types (R2: 0.020–0.058) (Fig. 2B). We observed that the fold change of 5hmC level in pan-tumor (all) DhmR genes was correlated to every tumor tissue (R2: 0.267–0.572), which was expected, as this comparison would encompass the common differences in 5hmC occupancy between all tumor and normal samples (Fig. 2B).

We further examined the set of DhmR genes that exhibited concordant changes in all tumor types: 140 genes exhibited concordant changes in 5hmC occupancy (Supplementary Data 4), including 111 hyper-hydroxymethylated genes (Fig. 2C) and 29 hypo-hydroxymethylated genes (Fig. 2D), respectively. Although only a small subset of DhmR genes was shared across all tumors (~3.3% of the total number of DhmR genes per tumor type), most DhmR genes were detected in at least 1 to 3 other tumor types. On average, 63% of the DhmR genes were detected with concordant changes in more than one tumor tissue type (i.e., genes that were concordantly hyper- or hypo-hydroxymethylated in several tumor tissue types). This suggests there exist common epigenomic changes that underlie the transcriptional regulation of different tumor types.

GSEA of the MSigDB Hallmark collection39 identified the following pathways as enriched in most tumor types (FDR < 0.05) (Fig. 2E): “HALLMARK_IL2_STAT5_SIGNALING”, “HALLMARK_KRAS_SIGNALING_UP”, “HALLMARK_ALLOGRAFT_REJECTION”, “HALLMARK_INTERFERON_GAMMA_RESPONSE”, “HALLMARK_INFLAMMATORY_RESPONSE”, “HALLMARK_TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB”. As DhmR genes were significantly enriched in cancer-related pathways, this analysis supported the hypothesis that genomic hydroxymethylation underlies transcriptional dysregulation during tumorigenesis. As a control, we performed GSEA of combined tumor tissues vs normal tissues and found that the enriched pathways were also shared among the GSEA of individual tumor types (Fig. 2E). Our analysis thus suggests both a common theme of 5hmC changes among different tumor types during tumorigenesis and unique changes in line with known expression differences between tissues.

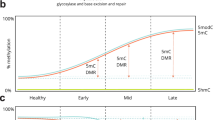

Tumor-specific changes in 5hmC modification remains stable through disease progression

We were interested in the distribution of 5hmC levels in tumor tissues over the course of disease progression. It was unclear whether tumor tissues undergo substantial changes in epigenomic state and tumor density as early-stage cancer progresses into late-stage. We found that 5hmC mass fraction, the fraction of cfDNA that is hydroxymethylated, did not show significant association with clinical stage of the tumor (excluding two tumor samples with unknown stage) nor sex of the subjects (ANOVA test, p > 0.05; Supplemental Table 3). Furthermore, in comparing the 5hmC level of gene bodies between early-stage (I + II) and late-stage (III + IV) tumor samples (Fig. 3A), we found that almost all genes exhibited significant correlation between early-stage and late-stage tumors regardless of tissue origin, with the coefficients of determination for a linear regression model ranging from 0.68 (lung tumor) to 0.89 (colon tumor). This suggests that tumor tissue-specific changes of 5hmC levels in the gene body regions were largely independent of cancer progression. DhmR analysis comparing early- and late-stage tumor samples further supported this observation, as it revealed few, if any, DhmR genes that passed the significance threshold for statistical difference (Fig. 3B). Additional analysis of non-gene body regions (CpG-Island, enhancer, promoter, SINE, etc.) showed a similar trend (Fig. S2A). Our results were consistent with previous report that found similar distribution of 5mC methylation between pairs of primary breast carcinoma and matched metastatic tumor40. Finally, by comparing tumor fraction estimate between early and late-stage tumor tissues28 using the whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data (non-5hmC-enriched), our analysis showed that the composition of tumor-derived DNA remained stable over the course of disease progression (Fig. 3C), suggesting that tumor cell density was similar between early- and late-stage tumors despite an increase in total tumor mass or metastatic events. As copy number variation tends to accumulate over the course of tumor development, we speculated that IchorCNA underestimated tumor fraction for very early-stage tumor samples that were driven by point mutations rather than structural variations of the genome. While the difference was not statistically significant, we noticed that early-stage pancreatic tumors had a lower average tumor fraction than late-stage pancreatic tumors. This observation is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that the most common genetic drivers in pancreatic cancer are point mutations in oncogenic genes (such as KRAS and TP53)41,42. Therefore, large-scale copy number variation events may occur late-stage and are under-represented in pancreatic tumors during the early stage compared to other cancer types. Taken together, our analysis results suggest that the tumor tissue-specific hydroxymethylation patterns were detectable in situ in early-stage tumors and remained stable over the course of disease progression. This stability is consistent with the model that epigenomic changes underlying tumor formation occur at an early step of the process. We therefore reasoned our profiling technology could capture tumor-specific 5hmC signals in bloodstream cfDNA, providing a unique fingerprint of the tumor origin as tumor cells or other tumor-associated cells shed their DNA during cellular turnover.

A Density plots of log2 fold change in gene features between early-stage tumor (I + II) vs normal tissues (x-axis), and that of late-stage tumor (III + IV) vs normal tissues (y-axis). Linear regression models and the coefficient of determination, R2, are shown in the inset of each panel. Cancer samples with unknown stage (n = 2, one colon tumor and one pancreatic tumor) were excluded for all analysis that compared early- versus late-stage samples. B Log2 fold-change (FC) of hydroxymethylation levels in gene features are compared as a function of their average log2 CPM between late-stage (III + IV) and early-stage (I + II) tumor tissues. Red and blue colors denote significant hyper or hypo-differentially hydroxymethylated region (DhmR) genes with FDR (Benjamini–Hochberg method) less than 0.05, respectively. Numbers on the top and bottom of the plots reflect the number of DhmR genes. C Tumor fraction estimates of early- and late-stage tumor tissues based on copy number variation (IchorCNA algorithm; see “Methods” for computation). “n.s.” indicates no significant difference between the two groups in each cancer type as determined by two-sided Wilcoxon test (FDR > 0.05).

Comparative analysis of hydroxymethylation patterns across tumor tissues and cfDNA samples

To determine whether 5hmC signals of tumor tissues are detectable in cfDNA, we first analyzed a total of 2687 cfDNA samples that were collected from 1678 healthy subjects and 1009 patients who were diagnosed with cancer types that correspond to the tumor tissue cohort that we analyzed (collection described in “Methods”) (Supplemental Table 2; cohort description in Supplementary Data 3). DhmR analysis detected a variable number of genes with significant changes in 5hmC occupancy across different cancer types (Fig. 4A): specifically, cfDNA from pancreatic cancer subjects exhibited the most dramatic change in 5hmC occupancy (~45.8% hyper-hydroxymethylated and ~44.7% hypo-hydroxymethylated genes) while those from breast cancer subjects had the least significant changes (~12.7% hyper-hydroxymethylated and ~9.4% hypo-hydroxymethylated genes). When aggregating all cancer types together, we identified 44.8% (7791) hyper-DhmR and 37.8% (6573) hypo-DhmR genes in the cfDNA samples (FDR < 0.05), respectively (Fig. 4A).

A Log2 fold-change (FC) of hydroxymethylation levels in gene features are compared as a function of their average log2 counts per millions (CPM) between cancer (n = 1009) and control (n = 1678) cfDNA samples for each cancer type. Red and blue colors denote significant hyper or hypo-differentially hydroxymethylated region (DhmR) genes with FDR (Benjamini–Hochberg method) less than 0.05, respectively. Numbers on the top and bottom of the plots reflect the number of DhmR genes. B Tumor fraction estimates of early- and late-stage cancer cfDNA samples. “n.s.” indicates no significant difference between the two groups in each cancer type based on two-sided Wilcoxon test (FDR > 0.05). Cancer samples with unknown stage (n = 19) were excluded for all analysis that compared early- versus late-stage samples. C Density plots of log2 fold change in gene features between early-stage cancer (I + II) vs control cfDNA (x-axis), and that of late-stage cancer (III + IV) vs control cfDNA (y-axis). Linear regression models and the coefficient of determination, R2, are shown in the inset of each panel. D Percentage of DhmR genes that exhibit concordant changes between tumor tissues and cancer cfDNA at early-stage (I + II) and late-stage (III + IV) progression for each cancer type and all cancer combined. Asterisks above each bar denote statistically significant differences (FDR < 0.05) in the proportion of concordant features between early- and late-stage cancer samples, as determined by chi-square test. E GSEA reveals significant concordance in the enrichment (red) or depletion (blue) of C6 oncogenic pathways between cancer cfDNA and tumor tissues relative to control. Color reflects normalized enrichment score (NES).

We also evaluated the cancer stage-dependence of 5hmC level in cfDNA. IchorCNA analysis revealed that tumor fraction estimates increased significantly from early- to late-stage for all cancer types in cfDNA (Fig. 4B). Consistent with this trend, we also detected an increase in plasma cfDNA concentration for all cancer types between early- and late-stage cohort (Fig. S3A). These results suggest that tumor-associated or tumor-derived DNA continues to increase in the bloodstream as cancer progresses due to increased tumor mass and tumor DNA shedding. To test this hypothesis, we compared the fold change in 5hmC level of gene bodies in cfDNA between early-stage and late-stage cancer patients. In contrast to tumor tissues, we found that cfDNA exhibited greater variability of 5hmC occupancy between stages for all cancers (R2 ranging from 0.24 to 0.73), except pancreatic cancer which had a R2 of 0.91 (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, hyper-hydroxymethylated genes in cfDNA samples of early-stage cancer (relative to control cfDNA) became even more dramatically hyper-hydroxymethylated in the late-stage samples of the same cancer type (Fig. 4C). To test whether cancer-specific signals become more pronounced in late-stage cfDNA samples, we trained a binomial classifier to distinguish cancer cfDNA from control group using the 5hmC levels in gene body features. As expected, cancer prediction probability score followed a monotonic increase with respect to cancer stage of the cfDNA samples (Fig. S4A). Taken together, our analysis suggests that cancer-specific 5hmC changes are detectable in cfDNA analyte across five cancer types at early stage and their signal increases in abundance over the course of disease progression.

To determine the concordance in 5hmC changes between tumor tissues and cancer cfDNA, we compared the DhmR analysis results between the two datasets. We stratified the samples based on stage and quantified the fraction of DhmR genes that were concordant in hydroxymethylation patterns (i.e., genes that were significantly hyper- or hypo-hydroxymethylated in the cancer group of both tissue and cfDNA) (Fig. 4D). As expected, concordance significantly increased when comparing early- to late-stage cancer samples. A significant overlap in DhmR genes was detected when comparing all cancer cfDNA and tumor tissue samples independent of individual cancer type and tumor stage (Fisher’s exact test, p « 0.01), indicating pan-cancer 5hmC signatures are detectable in blood (Figs. 4D, S3B and Supplementary Data 5). Many of the same cancer pathways were identified by GSEA in the 5hmC signals of both tumor tissues and cancer cfDNA samples (Fig. 4E), suggesting common biological origins. For example, “KRAS.600.UP.V1_UP”, “KRAS.300_UP.V1_UP” pathways, thought to be common drivers of many cancer types, were identified in our analysis. Other cancer type-specific pathways, including “BRCA1_DN.V1_UP”, “KRAS.LUNG.BREAST_UP.V1_UP”, were also enriched in the cfDNA samples of cancer subjects. A hypergeometric test further confirms the statistical significance in the overlap of pan-cancer pathway enrichment between tumor tissues and cancer cfDNA samples (Fig. S3C). Evaluating individual cancer type, we found that many oncogenic pathways were enriched or depleted in concordance between cancer cfDNA and their corresponding tumor tissues (Figs. 4E and S3C).

Our previous study demonstrated that pancreatic tumor and normal tissue-originated 5hmC fragments were detectable in cfDNA using genome-wide 5hmC profiling method17. We wanted to determine if this could be validated across all five cancer types. First, we investigated whether top DhmR genes obtained from tumor tissues were significantly enriched in cancer cfDNA signal using GSEA analysis (see Methods). Our analysis showed that the top 200–500 tissue DhmR genes (both hyper- and hypo-hydroxymethylated) were significantly enriched in cfDNA of cancer subjects, while the least tumor tissue differential genes (non-DhmR) exhibited no significant enrichment between cancer and control subjects compared to null distribution (Supplementary Data 2). Secondly, we explored if these DhmR genes could significantly improve classification of cancer and control subjects better than non-DhmR genes in cfDNA. Using a 20-fold cross-validation scheme, we used the top 200 hyper-DhmR and hypo-DhmR genes obtained from tumor tissues to train a binomial model that can classify cancer and control cfDNA samples (see “Methods”). We assessed the performance using the prediction score of test samples from each outer fold (Fig. S4B). The binomial model predicted cancer status with an AUC of 0.843 (95% confidence interval 0.827–0.859) using the top 200 hyper-DhmR genes, and 0.833 (95% confidence interval 0.817–0.849) using the top 200 hypo-DhmR genes. In contrast, a prediction model utilizing the 200 least DhmR genes led to significantly worse performance (Fig. S4B), with an AUC of 0.755 (95% confidence interval 0.735–0.774), compared to hyper-DhmR genes (DeLong test p value: 8.9 × 10−21) or hypo-DhmR genes (DeLong test p value: 3.1 × 10−17). Taken together, our analysis suggests that DhmR genes in tumor tissues improve cancer detection in cfDNA samples.

Multinomial modeling for prediction of tissue of tumor origin (TOTO) in cfDNA using tissue-variant 5hmC features

5hmC modifications have been previously shown to be highly tissue-specific3. We show in the following that our method captured tissue-specific 5hmC signatures that could be used to classify the tumor origins in cfDNA samples. An unsupervised projection of 5hmC level in gene body regions revealed that tissue samples from the same tissue origin clustered together regardless of cancer status and tumor stage (Fig. 5A). This was most evident for breast and ovary samples. Colon and lung samples were less clustered within the tissue type, suggesting their global 5hmC patterns were more variable both within normal samples and between tumor and normal samples. Furthermore, a two-way ANOVA analysis showed that 45.3% of the gene bodies were significantly different in their mean 5hmC levels between tissue types (FDR < 0.05, Benjamini–Hochberg method), but not between different disease states (i.e., tumor or normal, FDR > 0.05); in contrast, only 5.9% of the gene bodies significantly differed in their mean 5hmC levels between disease states (FDR < 0.05), but not between different tissue types (FDR > 0.05). As consistent with our previous analysis that only a small number of DhmR genes were shared by all tumor tissues (Fig. 2A), this analysis suggests that tissue-type identity contributes the dominant source of epigenomic variation in 5hmC levels across tumor tissues, leaving open the possibility of identifying the tissue origin of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) fragments based on 5hmC profiling.

A UMAP of normal and tumor tissue samples based on normalized 5hmC level in gene features. B Heatmap of TOTO prediction scores based on 20-fold nested cross-validation. TOTO Multinomial model is built from 5hmC signatures of tumor and normal tissue samples. C Receiver operating curve (ROC) of TOTO model trained and evaluated on cfDNA samples, with the area under ROC (auROC) for each class annotated in the legend. ROC is evaluated in the outer fold of cross-validation. D Confusion matrix of TOTO model in cfDNA samples. Performance is evaluated by considering the two most probable predictions in the outer fold of cross validation. Overall accuracy is 85.2%. E ROC of TOTO model trained on cfDNA data and evaluated on tumor tissue samples, with the auROC for each class annotated in the legend. ROC is evaluated in the outer fold of cross-validation. F Confusion matrix of TOTO model in tumor tissue samples. Performance is evaluated by considering the two most probable predictions in the outer fold of cross-validation. Overall accuracy is 92.2%. Dashed lines correspond to identity.

To quantitatively assess the similarities between tumor and normal samples, we sought to predict tissue origins using 5hmC gene body signatures. We determined whether 5hmC measurement in normal tissues alone might capture sufficient information to train a model that can classify tissue origins in tumor samples. To address this question, we trained a multinomial model based on tissue-specific 5hmC signatures that were identified in normal tissue dataset from a previous study2 (this dataset contained no tumor tissues) (Fig. S4C). The tissue origin prediction was accurate in normal samples except for colon samples. This may be due to differences in biopsy sites of colon samples between these two datasets (Fig. S4C). In contrast, and unsurprisingly, prediction accuracies of tumor tissues were reduced using this model when considering only the top prediction (cancer class with the highest prediction score): 40.5% for breast, 57.1% for colon, 78.8% for lung, 40.5% for ovary and 38.1% for pancreas. The overall accuracy was 50.7% when considering only the top prediction. Even when the second most probable prediction was considered, prediction accuracies for tumor samples remained unsatisfactory: 67.6% for breast, 81% for colon, 87.9% for lung, 66.7% for ovary and 47.6% for pancreas. The overall accuracy with the two most probable predictions was 70.5%. This suggests that 5hmC signatures of normal tissues alone do not contain complete information to discern tumor samples of different tissue origins. As we had shown, all tumor tissues underwent substantial tissue-specific changes in 5hmC distributions compared to the corresponding normal tissues. This implies training an accurate TOTO classifier requires consideration of tissue-specific 5hmC features while accounting for confounding effects of tumor-driven changes.

To improve TOTO prediction performance, we trained a multinomial model using both normal and tumor tissue data from this study and validated the performance using 20-fold nested cross validation43. TOTO prediction scores of the outer cross-validation loop showed that this multinomial model accurately classified tumor tissues from normal tissues (Figs. 5B and S5A). In evaluating the features that the model selected for TOTO prediction, we identified 409 genes with non-zero coefficients in the model (Supplementary Data 6). Pathway enrichment analysis (GSEA) indicated that these genes were highly enriched for cancer-related pathways such as “KRAS.600_UP.V1_UP”, “KRAS.300_UP.V1_UP” (Supplementary Data 7). This suggests that the model correctly identified features that are related to cancer biology, while preserving tissue-specific information. The overall accuracies of this model were 87.3% and 96.3% when considering the top and two most probable predictions, respectively (Fig. S5B), a substantial improvement over the model trained on the 5hmC dataset consisting of only normal tissues. The TOTO model achieved accuracies of tissue origin prediction for each tumor tissue type: 91.9% for breast, 98.4% for colon, 97.0% for lung, 95.2% for ovarian, and 92.9% for pancreas (Fig. S5B). Importantly, the model did not confuse tissue types of healthy samples and retained similar prediction accuracy as in cancer samples. We also found that tumor samples with the correct TOTO predictions had significantly higher tumor fractions in breast, ovary, and lung tumor tissues, while prediction accuracies in pancreatic and colon tumor samples did not significantly correlate with their tumor fraction estimates (Fig. S5C). Combined together, our model learned specific 5hmC signatures that differentiated tumor and normal tissues of distinct origins. As tissue biopsy operation recovers a variable mixture of tumor and normal cells, tumor samples that are incorrectly classified as “normal” by the model may reflect low tumor DNA contribution due to operational variation, which is consistent with our tumor fraction analysis.

Finally, we implemented a model for TOTO prediction in cfDNA samples by leveraging 5hmC signatures identified in the tumor tissue atlas. Given that the majority of cfDNA is from blood cells, we hypothesized that tumor tissue signals in cfDNA would be confounded by immune cell signals, hindering a direct application of a TOTO model trained on a tumor tissue dataset. We reasoned that genes with the most variant 5hmC density among tissue types contained relevant signals for TOTO prediction, and therefore selected 5,268 tissue variant genes (Supplementary Data 1) as input features for training a model to predict TOTO in cfDNA. A schematic of the cfDNA TOTO model that we developed is shown in Fig. S6A. For the cfDNA test set, we first built a binomial model to distinguish cancer and control cohorts using all 2687 cfDNA samples, then selected cancer samples with high cancer scores (predicted “cancer” at 99% model specificity) for training/evaluating the cfDNA TOTO prediction model (n = 546). Using a 20-fold cross-validation scheme, we measured TOTO model test scores from each outer fold to calculate overall model performance. We found that the model maintained elevated sensitivity and specificity for each tumor origin (Fig. 5C), with ovarian and colon tumor types achieving the highest and lowest area under Receiver Operating Characteristic curves, respectively. The TOTO model correctly predicted “breast”, “colon”, “lung”, “ovary”, and “pancreas” classes in cfDNA samples with specificities of 98.8%, 97.2%, 90.5%, 99.2%, and 93.7%, respectively. Prediction sensitivities for “breast”, “colon”, “lung”, “ovary”, and “pancreas” classes were 55.2%, 83.0%, 93.0%, 86.3%, and 81.1%, respectively (Fig. 5D). Overall model accuracies were 70.7% and 85.2% when considering the top one and top two ranked predictions, respectively (Fig. 5D and S5D). Cancer progression had no statistically discernible impact (chi-square test p value = 0.265) on the TOTO model performance in cfDNA samples, as about 67% of stage I and II, 66% of stage III, and 74% of stage IV subjects were correctly predicted (Fig. S5E). To demonstrate that the cfDNA TOTO model made predictions based on tumor tissue signals, we also applied the model, which had been trained on cfDNA samples, to predict labels in tissue samples (Fig. 5E). The model correctly predicted the tumor types of tissue samples with overall accuracies of 81.1% and 92.2%, when considering the top one and top two ranked predictions, respectively (Figs. 5F and S5F). Taken together, we show that epigenomic profiling of 5hmC in tumor tissues captures relevant biological information that can enable development of a predictive model to classify TOTO in cfDNA analytes.

Discussion

5hmC is an epigenetic modification in the genome that modulates transcriptional expression and undergoes dynamic changes during cellular development. In this study, we set out to explore the genomic distributions of 5hmC across multiple tumor types and case controlled cfDNA samples. We profiled their dynamics and quantified the degree to which 5hmC changes concur between cfDNA and tissues in the context of cancer staging. Our study concludes with a collection of tissue-specific 5hmC signatures that can be leveraged to accurately predict the tumor origin in cfDNA samples.

Using synthetic spike-ins, we quantified 5hmC mass fraction in tumor tissues. Our findings revealed a consistent and global reduction of hydroxymethylation across breast, colon, pancreatic, lung, and ovary tumors when compared to their respective normal tissues. This supports the notion that transcriptional dysregulation in tumorigenesis is partially driven by the redistribution of 5hmC level throughout the genome44,45. This observation aligns with existing studies indicating a general reduction in genomic 5hmC content in cancer cells and solid tumor tissues46. The percentage reduction in 5hmC mass fraction varies across tissues, ranging from 70.5% (breast) to 41.8% (pancreas) with respect to the corresponding normal tissues. ANOVA results indicate a significant impact on global 5hmC by both cohort (tumor/normal) and tissue type, suggesting that there are tissue-specific variations in 5hmC abundance. In contrast to prior research47,48, our study found no significant correlation between age and 5hmC levels in tumor tissue samples (R2 = 0.0068, F-test p value = 0.230). This discrepancy can be attributed to differences in age distributions among the studies, as approximately 93% of the subjects in our study are over the age of 40. Quantification of 5hmC content in the genomic DNA of human blood revealed that most changes occur before the age of 4034. Additionally, Buscarlet and their colleagues identified significant differences in the genomic distribution of 5hmC between young (ages 0–30) and old (ages 70–90) subjects, but not amongst individuals within the older group47. Immunohistochemical measurement of global 5hmC levels in colorectal cancer patients also agrees with our finding49. Therefore, the absence of significant correlation between age and 5hmC level in our study reflects the predominantly older individuals, whose 5hmC alterations are less pronounced.

We noticed a decrease in 5hmC density in genic regions of tumors, whereas non-genic regions, such as LINE elements, exhibited an increase in 5hmC. This pattern aligns with the established methylation pattern of LINE elements in human cancer, known for being hypo-methylated and considered a hallmark of cancer50. At the pathway level, genes related to inflammatory and immune responses displayed high levels of hyper-hydroxymethylation across all tumor types. This hyper-hydroxymethylation in inflammatory response pathways is consistent with the well-established association between inflammation and cancer51. Additionally, key cancer-related pathways, such as “KRAS,” “TNFA-NFKB,” “hypoxia,” and “apoptosis,” showed hyper-hydroxymethylation in almost all tumor types, aligning with cancer biology52,53,54,55. Notably, the “EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION” pathway exhibited higher hyper-hydroxymethylation in pancreatic tumor samples compared to other tumor types, indicating the more aggressive nature of pancreatic tumors compared to others56.

In comparing tumor to normal tissues, we identified a total of 5241 and 3706 gene bodies that are hyper-hydroxymethylated and hypo-hydroxymethylated in tumor tissues, respectively. Compared to other tissue types, pancreatic tumor tissues underwent the most dramatic 5hmC changes during tumorigenesis. In pancreatic tumor tissue, 56.2% of the DhmR genes were unique and not found in other tumor types, while other tissues have an average of 30.1% unique DhmR genes. Existing study provides evidence that the cellular composition of pancreas undergoes changes during tumor development57, which might explain the dramatic 5hmC changes in pancreatic tumors we observed in this study. Our differential hydroxymethylation analysis supports this, as we discovered that pancreatic tumor tissues have increased hydroxymethylation in gene sets that are typically associated with mesenchymal stromal cells, myeloid cells, and lymphoid cells (Fig. S1E).

We observed a stable distribution of 5hmC across genic regions in tumor tissues over the course of tumor progression. Through both correlation and differential analysis, we found that the majority of gene body features exhibited concordant changes between early and late stages of the same tumor tissue type, suggesting that 5hmC changes primarily occur during the initial step of tumorigenesis and undergo minimal alterations over stage. Using WGS data, we utilized the IchorCNA algorithm to estimate tumor fractions in both tumor tissues and cfDNA samples based on genomic copy number variation28. Our observations revealed that the tumor fraction also remains stable in tumor tissues between early and late-stage cancer patients (Fig. 3C). In contrast, cfDNA tumor fractions and concentrations increase as cancer progresses from early to late stages across all cancer types (Figs. 4B and S3A). Our results suggest there is an increase in the detectable level of tumor-derived or tumor-associated DNA in plasma cfDNA during cancer progression leading to a corresponding increase in cancer prediction scores in cfDNA samples between early and late-stage cohort (Fig. S4A). We also detected a highly variable number of DhmR genes in cfDNA between cancer types, which likely reflected a variability in ctDNA. It is not well-understood why different tumors lead to different amount of ctDNA, but it has been thought to be due to a combination of factors such as tumor burden, apoptotic rate, cellular secretion, and proximity to the circulatory system58.

A stable 5hmC signature specific to tumor tissues is highly valuable for developing a predictive model to determine the presence of cancer and its tumor origin in circulating cfDNA. Previous studies have utilized tissue-derived 5hmC features to predict presence of cancer using cfDNA from pancreatic cancer patients17. In our study, we identified a significant overlap in cancer-associated 5hmC signatures between cancer cfDNA and tumor tissues, supported by the concordant enrichment of oncogenic pathways. The concordance in DhmR genes between cfDNA and tumor tissues is further increased as cancer progresses, as expected by the change in tumor fraction estimates. This overlap indicates that the cfDNA DhmR genes reliably represent the tumor DhmR genes. Further examination of the comparison between the 8595 differential gene bodies in tumor tissues and the 14,364 differential gene bodies in cfDNA revealed an overlap of 2174 hyper- and 1180 hypo-hydroxymethylated gene bodies, showing concordance in enrichment and direction of change. Furthermore, models based on top hyper-DhmR and hypo-DhmR genes derived from tumor tissues predicted presence of cancer in cfDNA with significantly higher sensitivity than the non-DhmR genes, suggesting 5hmC signatures originating from tumor tissues improves cancer prediction in cfDNA.

We also measured some discrepancies in 5hmC changes between breast tumor tissues and breast cancer cfDNA. Breast cancer samples show fewer shared changes in oncogenic pathways between tissues and cfDNA compared to other cancer types (Figs. 4D and S3C). This suggests that the 5hmC modifications driving breast tumor progression are not well represented in blood cfDNA. We also observed that, although all cancer samples exhibit increased cfDNA concentrations during tumor progression, breast cancer cfDNA samples have the lowest increase in cfDNA concentration compared to other cancer types (Fig. S3A). Other groups that measured the mutational load of cfDNA across different cancer types also observed similar findings: breast cancer led to lower abundance of ctDNA compared to colorectal, lung, and ovarian cancers59,60. This implies that breast tumors may release less tumor-derived or tumor-associated cfDNA into the bloodstream compared to other cancer types, which provides an explanation for the lower concordance in 5hmC signatures between breast cancer cfDNA and breast tumor tissues. The discordance between breast tumor tissue and cfDNA, driven by the lower ctDNA level in blood, may render the task of detecting breast cancer in cfDNA particularly more challenging compared to other cancer types, as previously reported61,62,63,64.

For the cfDNA TOTO model, true positive samples tend to have a higher tumor fraction at the late stage (Fig. S5C); however, the overall accuracy remains stable across stages (Fig. S5E). This indicates that while tumor tissue-specific 5hmC signals are detectable at all stages, individual cfDNA samples may differ in their content due to nuanced differences in the pathophysiology of the patients. We also demonstrated that 5hmC signatures of tumor tissues are essential for developing a predictive model that can accurately classify TOTO in cfDNA samples. By identifying tissue variant genes and incorporating them as features, we developed a TOTO prediction model in cfDNA analytes with an average prediction accuracy of 85.2% (ranging from 55.2 to 93%) and an average specificity of 95.9% (ranging from 90.5 to 99.2%). Our study demonstrates a proof-of-concept approach for an accurate, non-invasive multi-cancer detection test based on 5hmC profiling of cfDNA. We show here that epigenomic profiling of tumor tissues captures cancer-specific 5hmC signals that are predictive of cancer origins in cfDNA over different disease stages.

Currently, early cancer detection guidelines are only available for individuals with known familial or genetic risk, leaving a large portion of the population without effective early testing options. As a result, most diagnoses are made only after symptoms appear, which typically indicate a late-stage disease. Our study suggests that early cancer detection and TOTO can be predicted using cfDNA 5hmC signatures. A key limitation of our study is the reliance on internal cross-validation within a single cohort from 146 U.S. sites with limited population diversity (predominantly European ancestry). This design may overestimate model performance as it cannot account for batch effects across cohorts, population heterogeneity, or differences between our enriched cancer cohort and real-world screening populations. External validation in independent, prospectively collected cohorts—particularly those including diverse ethnicities, geographic regions, and comorbid conditions—is essential to determine whether our observed TOTO prediction accuracy and cancer detection performance translate to clinical utility. In the clinical settings, we envision this assay can be implemented as a non-invasive diagnostic tool by utilizing a standard blood draw, with samples processed in certified laboratory facilities and analyzed in a secure computing environment. Administered as part of a recurrent health examination, a non-invasive 5hmC test can provide further guidance on diagnostic or treatment decisions based on the specific epigenetic profiles65. Future clinical studies could readily consider modeling the potential effect of genetic, non-genetic, and environmental factors in the patient population, which may further improve the specificity of the test. As presented, the 5hmC-based assay provides a simplified cancer score quantification that can be implemented as a clinically validated cancer diagnostic report to medical providers, contributing to other clinically actionable information for early cancer detection and patient care.

Data availability

Instructions for data access are available at https://github.com/ClearNoteHealth-OpenAccess/ClearNoteHealth_TOTO_nature_comm_bio_analysis_code. The data and code provided therein include all underlying data used to generate figures and Supplementary Figures. This is inclusive of genes and pathway information supporting the differential genes sets used to train models in this study. Due to ethical regulations and patient privacy, we are unable to make the raw sequencing data publicly available; however, to access the sequencing data, interested party can submit written request to the corresponding author (S.L.), which will be reviewed by the corresponding IRB at participating sites (wcgIRB, Sterling, Advarra, or local Institutional Review Boards) for approval.

Code availability

Analysis code is available at https://github.com/ClearNoteHealth-OpenAccess/ClearNoteHealth_TOTO_nature_comm_bio_analysis_code. An archive of the analysis code has been deposited at Zenodo repository (10.5281)32.

References

Song, C.-X. & He, C. The hunt for 5-hydroxymethylcytosine: the sixth base. Epigenomics 3, 521–523 (2011).

Cui, X.-L. et al. A human tissue map of 5-hydroxymethylcytosines exhibits tissue specificity through gene and enhancer modulation. Nat. Commun. 11, 6161 (2020).

Song, C.-X. et al. Selective chemical labeling reveals the genome-wide distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 68–72 (2011).

Yu, M. et al. Base-resolution analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the mammalian genome. Cell 149, 1368–1380 (2012).

Song, C.-X., Yi, C. & He, C. Mapping recently identified nucleotide variants in the genome and transcriptome. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 1107–1116 (2012).

He, B. et al. Tissue-specific 5-hydroxymethylcytosine landscape of the human genome. Nat. Commun. 12, 4249 (2021).

Lian, C. G. et al. Loss of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is an epigenetic hallmark of melanoma. Cell 150, 1135–1146 (2012).

Gao, P. et al. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine profiling from genomic and cell-free DNA for colorectal cancers patients. J. Cell Mol. Med. 23, 3530–3537 (2019).

Wang, J., Su, Y., Tian, Y., Ding, Y. & Wang, X. Characterization of DNA hydroxymethylation profile in cervical cancer. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 47, 2706–2714 (2019).

Schrag, D. et al. Blood-based tests for multicancer early detection (PATHFINDER): a prospective cohort study. Lancet 402, 1251–1260 (2023).

Nakauchi, Y. et al. The cell type-specific 5hmC landscape and dynamics of healthy human hematopoiesis and TET2-mutant preleukemia. Blood Cancer Discov. 3, 346–367 (2022).

Li, W. et al. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine signatures in circulating cell-free DNA as diagnostic biomarkers for human cancers. Cell Res. 27, 1243–1257 (2017).

Ranucci, R. Cell-free DNA: applications in different diseases. Methods Mol. Biol. 1909, 3–12 (2019).

Rafalko, J. et al. Genome-wide cell-free DNA screening: a focus on copy-number variants. Genet. Med. 23, 1847–1853 (2021).

Song, C.-X. et al. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine signatures in cell-free DNA provide information about tumor types and stages. Cell Res. 27, 1231–1242 (2017).

Applebaum, M. A. et al. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine profiles in circulating cell-free DNA associate with disease burden in children with neuroblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 1309–1317 (2020).

Guler, G. D. et al. Detection of early stage pancreatic cancer using 5-hydroxymethylcytosine signatures in circulating cell free DNA. Nat. Commun. 11, 5270 (2020).

Cai, J. et al. An integrative analysis of genome-wide 5-hydroxymethylcytosines in circulating cell-free DNA detects noninvasive diagnostic markers for gliomas. NeuroOncol. Adv. 3, vdab049 (2021).

Haan, D. et al. Epigenomic blood-based early detection of pancreatic cancer employing cell-free DNA. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 1802–1809.e6 (2023).

M. Vasimuddin, S. Misra, H. Li & S. Aluru. Efficient architecture-aware acceleration of BWA-MEM for multicore systems. In Proc. 2019 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS) 314–324 https://doi.org/10.1109/IPDPS.2019.00041 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010).

Heinz, S. et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38, 576–589 (2010).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

McInnes, L., Healy, J. & Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1802.03426 (2020).

Wolf, F. A., Angerer, P. & Theis, F. J. SCANPY: large-scale single-cell gene expression data analysis. Genome Biol. 19, 15 (2018).

Adalsteinsson, V. A. et al. Scalable whole-exome sequencing of cell-free DNA reveals high concordance with metastatic tumors. Nat. Commun. 8, 1324 (2017).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–22 (2010).

DeLong, E. R., DeLong, D. M. & Clarke-Pearson, D. L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44, 837–845 (1988).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 (2005).

ClearNote Health. 5-hydroxymethylcytosine analysis reveals stable epigenomic changes in tumor tissue that enable cancer detection in cell-free DNA. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16953151 (2025).

SEER Cancer Statistics Factsheets: Common Cancer Sites. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/common.html.

Xiong, J. et al. DNA hydroxymethylation age of human blood determined by capillary hydrophilic-interaction liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Clin. Epigenetics 7, 72 (2015).

Iqbal, K., Jin, S.-G., Pfeifer, G. P. & Szabó, P. E. Reprogramming of the paternal genome upon fertilization involves genome-wide oxidation of 5-methylcytosine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 3642–3647 (2011).

Ficz, G. et al. Dynamic regulation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mouse ES cells and during differentiation. Nature 473, 398–402 (2011).

Du, Y. & Grandis, J. R. Receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatases in cancer. Chin. J. Cancer 34, 61–69 (2014).

Muraro, M. J. et al. A single-cell transcriptome atlas of the human pancreas. Cell Syst. 3, 385–394.e3 (2016).

Liberzon, A. et al. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 1, 417–425 (2015).

Reyngold, M. et al. Remodeling of the methylation landscape in breast cancer metastasis. PloS ONE 9, e103896 (2014).

Jones, S. et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science 321, 1801–1806 (2008).

Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature 531, 47–52 (2016).

Zhong, Y., He, J. & Chalise, P. Nested and repeated cross validation for classification model with high-dimensional data. Rev. Colomb. Estad. 43, 103–125 (2020).

Bradner, J. E., Hnisz, D. & Young, R. A. Transcriptional addiction in cancer. Cell 168, 629–643 (2017).

Hu, H. et al. Epigenomic landscape of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine reveals its transcriptional regulation of lncRNAs in colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 116, 658–668 (2017).

Pfeifer, G. P., Xiong, W., Hahn, M. A. & Jin, S.-G. The role of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in human cancer. Cell Tissue Res. 356, 631–641 (2014).

Buscarlet, M., Tessier, A., Provost, S., Mollica, L. & Busque, L. Human blood cell levels of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) decline with age, partly related to acquired mutations in TET2. Exp. Hematol. 44, 1072–1084 (2016).

Borkowska, J. et al. Alterations in 5hmC level and genomic distribution in aging-related epigenetic drift in human adipose stem cells. Epigenomics 12, 423–437 (2020).

Tian, Y. et al. Global changes of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and 5-methylcytosine from normal to tumor tissues are associated with carcinogenesis and prognosis in colorectal cancer. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 18, 747–756 (2017).

Burns, K. H. Transposable elements in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17, 415–424 (2017).

Greten, F. R. & Grivennikov, S. I. Inflammation and cancer: triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity 51, 27–41 (2019).

Wajant, H. The role of TNF in cancer. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 49, 1–15 (2009).

Wang, R.-A. et al. Apoptosis drives cancer cells proliferate and metastasize. J. Cell Mol. Med. 17, 205–211 (2013).

Labi, V. & Erlacher, M. How cell death shapes cancer. Cell Death Dis. 6, e1675–e1675 (2015).

Knijnenburg, T. A. et al. Genomic and molecular landscape of DNA damage repair deficiency across the Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell Rep. 23, 239–254.e6 (2018).

Yeung, K. T. & Yang, J. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition in tumor metastasis. Mol. Oncol. 11, 28–39 (2017).

Chen, K. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic change in tumor microenvironment during pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma malignant progression. eBioMedicine 66, 103315 (2021).

Thierry, A. R., El Messaoudi, S., Gahan, P. B., Anker, P. & Stroun, M. Origins, structures, and functions of circulating DNA in oncology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 35, 347–376 (2016).

Phallen, J. et al. Direct detection of early-stage cancers using circulating tumor DNA. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaan2415 (2017).

Bettegowda, C. et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 224ra24 (2014).

Liu, M. C. et al. Plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA) assays for early multi-cancer detection: the circulating cell-free genome atlas (CCGA) study. Ann. Oncol. 29, viii14 (2018).

Chen, Y.-H. et al. Next-generation sequencing of circulating tumor DNA to predict recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. npj Breast Cancer 3, 24 (2017).

Cohen, J. D. et al. Detection and localization of surgically resectable cancers with a multi-analyte blood test. Science 359, 926–930 (2018).

Alba-Bernal, A. et al. Challenges and achievements of liquid biopsy technologies employed in early breast cancer. eBioMedicine 62, 103100 (2020).

Sjöström, M. et al. The 5-hydroxymethylcytosine landscape of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 82, 3888–3902 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Elizabeth Stewart and Margaret Freitag and funded by ClearNote Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X., Y.N., S.L., W.V., G.D.G. and A.B. wrote the manuscript. S.L., W.V., A.B., Y.X. and Y.N. conceived and designed the study. Y.X. and Y.N. performed computational analyses and developed machine learning models with inputs and assistance from V.F., D.H., W.G. and R.C. T.P., E.M., C.K.E., R.M., A.N., V.L., S.C. and M.P. curated clinical metadata, performed tissue sample processing, DNA extraction, cfDNA sample processing, library construction and sequencing operations. A.B., M.P. and J.S. coordinated clinical sample collection and managed institutional review board approvals. K.H. developed the data processing pipelines. A.S. maintained sample databases. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Ana Rita Grosso and Johannes Stortz.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article