Abstract

We report the realization of the first planar optical trap and imaging system using a sheet of light that allows interrogation of living specimens in a plane. An orthogonal widefield detection is employed to directly visualize the trapping of the target object (dielectric beads/cells) in a plane. The planar trap is realized on an inverted optical stage with illumination from the bottom. The system uses a combination of a cylindrical lens and a high NA objective lens to generate a tightly focused diffraction-limited sheet of light. For trapping objects in a selective XZ-plane, the sample (beads/cells suspended in a solution) is illuminated by a sheet of light (along the Z-axis with coverslip along XZ), whereas the detection is carried out perpendicular to the coverslip (along the Y-axis). Orthogonal detection allows direct visualization of the trapped object in the 2D plane illuminated by the lightsheet. The generated PSF has a dimension of 2073.84 μm2 (along XZ), which defines the active trap region/zone. To estimate the trap stiffness, both variance-based equipartition and video-based object tracking methods are employed. Results (image and video) show real-time trapping of dielectric beads and live cells in the trap zone (2D plane). Prolonged exposure shows objects getting trapped and builds up a 2D layer of beads/cells, demonstrating stable trapping in a selective layer. The technique is furthered by successfully trapping fluorescently labeled live cells in a single plane and simultaneously performing fluorescence imaging on the go with sub-cellular resolution. The potential of the planar trap lies in its ability to confine objects (such as dielectric beads and cells) in a selective 2D plane and allow interrogation, thereby opening up the possibility of new kinds of studies in optical manipulation, fluorescence microscopy and biotechnology.

Statement of Significance: The ability to confine and interrogate living specimens (cells) in a plane is an incredible feat that paves the way for new kinds of studies. Currently, there is no available technique that can trap microscopic living objects in a 2D plane. The successful trapping of live cells in a plane, and high-resolution fluorescence imaging on the go, have applications in the broad field of fluorescence microscopy, optical physics and biotechnology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optical manipulation of minuscule objects in a selective 2D plane is crucial for conducting studies restricted to two dimensions. An optical trap system that is capable of trapping cells in a plane has applications across the wide spectrum of biological and physical sciences. Although the existing optical manipulation systems that are primarily point-traps can trap and study a single object at any given point in time, there exist systems with several point traps. These traps are generated using a variety of techniques such as acousto-optic deflectors, spatial light modulators, or a combination1,2,3,4. These techniques allow study and manipulation of multiple particles (e.g., colloidal particles). Such setups often require multiple laser beams or intricate beam-shaping optics to create an array of point traps. In comparison, the proposed 2D trap uses a single beam to generate a two-dimensional trapping zone, which is capable of trapping multiple objects simultaneously. This approach significantly reduces the system complexity and optical alignment requirements, offering an alternate platform for trapping multiple microscopic particles. Moreover, the proposed technique allows studies requiring many particle interactions in a single thin layer. In this context, 2D trap can elevate the constraint faced by point-based optical traps and may enable trapping several particles (e.g, beads, cells, etc.) simultaneously in a single plane, thereby giving an opportunity to study their interactions and collective dynamics constrained to two dimensions. Overall, a planar trap system that can facilitate studies limited to a 2D plane is of utmost need for advancing touch-free manipulation of both living and non-living objects.

The first ever optical trap was realized by Arthur Askhin in the year 19705. The technique was successfully used to trap both living and non-living objects with sizes as small as a few microns (dielectric beads, bacteria, red blood cell) to as large as a few millimeters (multicellular organisms)6,7. Subsequently, the technique has grown into a major investigation tool in multidisciplinary sciences. For example, the technique is used to investigate, short-range colloidal interactions, and cellular-liposome interactions8. In another study, the technique is used for manipulating microscopic objects such as rotation of microscopic objects, liposome biomechanics, and single-molecule force spectroscopy9,10,11,12. To carry out diverse studies involving forces in the pico-Newton range, several important variants of point trap have emerged over the years13,14,15,16,17. This includes ring-vortex traps, shape-phase holography, scanning point traps, beam shaping, and hyperbolic meta-materials18,19,20,21,22,23,24. In the year 2022, our group proposed the first light sheet-based optical trap that demonstrated capturing objects in a line25. This was the first time a non-traditional PSF was used to trap objects. However, the proposed light sheet PSF can trap objects in a plane. This is largely due to the shape of PSF that resembles a thin sheet of light. Such a capability may facilitate new kinds of studies restricted to two dimensions, allowing trapping of freely moving objects in a plane. The technique may be useful to investigate particle dynamics constrained to two dimensions, and study their collective behavior.

To circumvent the limitations of existing point-based optical traps and enable new capabilities, we demonstrate a new kind of optical trap powered by lightsheet26. The objects (dielectric beads/cells) are trapped in a single 2D plane. Since trapping is limited to two dimensions, the proposed planar trap allows the study of particle-particle interaction in a single layer. In principle, the technique may allow layer-by-layer deposition of objects (dielectric beads, cells, etc.) in a controlled manner or allow the study of many particles interacting in a single layer. In cell biology, the technique can be used to arrange or trap cells in a single layer and study cell–cell interaction. Overall, the capability of 2D-constrained trapping and manipulation may find applications in diverse research disciplines ranging from optical imaging to cell biology.

Results

Planar trap system

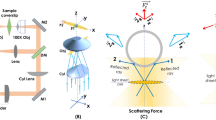

The schematic diagram of the developed planar trap system is shown in Fig. 1. The system consists of a trapping sub-system, a customized sample holder, a brightfield illumination module, and a 4f widefield detection sub-system. The trapping sub-system utilizes a 1064 nm continuous-wave laser source, a 1.7X beam-expander, a cylindrical lens (fCL= 75 mm), and an objective lens (0.5 NA, 50X) to generate a tightly focused sheet of light. The system operates in an upright configuration, with a pair of mirrors strategically placed, one before the beam expander and another before the objective lens to guide the beam into the sample plane. Brightfield illumination is provided by a broadband white light LED source, collimated using a biconvex lens L3 (f = 50 mm), and directed through a low numerical aperture objective lens (10X, 0.3 NA) for uniform sample illumination (in the sample holder). The sample holder is custom-built using a pair of coverslips and a glass slide. These coverslips are affixed to the top and bottom surfaces of the glass slide, with half of it, and the remaining half creates a gap of around 1 mm, in which the sample (particles suspended in a solution) is injected using a syringe (see Fig. 1). This customized sample holder is mounted on a high-precision 3-axis Nano-positioning stage for accurate spatial movement. The detection sub-system is orthogonal to the trapping sub-system and faces the lightsheet (along Y-axis) which is perpendicular to the lightsheet plane (XZ) (see the inset in Fig. 1A). Detection is essentially a 4f optical configuration that consists of an objective lens (20X, 0.4 NA), tube lens (f = 200 mm) and a fast sCMOS camera (Zyla 4.2, Andor Inc., UK)). This gives a resultant magnification of M = (fTL/fObj) = 200 mm/10 mm = 20, i.e, 20X. This magnification ensures that the image formed on the camera sensor is 20 times larger than the object in the sample plane, enabling better visualization and high-resolution imaging. The dielectric beads trapped in the selective light sheet plane (XZ) are directly visualized in the camera. Alongside, the picture of the actual system and the sub-systems therein are also shown (see Fig. 1B).

Schematic diagram and actual planar trap system. A The system consists of a lightsheet trapping sub-system, a sample-holder, a white light illumination sub-system, and a detection sub-system. The trapping sub-system uses a 1064 nm IR laser, a beam-expander (BE), along with a combination of cylindrical lens (CL) and objective lens (Obj1, 50X) lens for generating a diffraction-limited lightsheet PSF to realize 2D planar optical trap. A separate white light illumination system (consisting of white LED light, 10X objective lens (Obj2), and a biconvex lens (L3)) is used to visualize the specimen. The detection is achieved by an orthogonal detection system (placed perpendicular to the trapping sub-system) using a third objective (Obj3, 20X) and tube lens (TL) to directly visualize objects being trapped in the lightsheet PSF. The insets show the sample holder with the beads trapped in the lightsheet PSF, and the detection along the y-axis. B Picture of the actual planar trap system. Alongside, key sub-systems (trapping/illumination, sample holder, white light illumination, nano-positioning stage, and detection) are also shown.

Calibration of pLOT system and lightsheet PSF characterization

The light sheet PSF generated by the trapping sub-system was characterized for quality trapping. Figure 2A shows the schematic diagram of the optical setup used for characterizing the lightsheet PSF. A CCD camera is placed in the beam path and scanned about the focus of the objective lens. The data (image of the field) is recorded at a sampling distance of 2 μm along the z-axis. The images are then stacked together to reconstruct the 3D field. The corresponding volume view along with the sectional views (XZ and YZ) of the light sheet field is shown in Fig. 2B. The sheet of light generated by the trapping sub-system is quite apparent. In addition, the thickness of the field (measured in terms of FWHM along the Y-axis) is determined at varying distances along beam propagation (Z-direction) as shown in Fig. 2C (intensity plots). This characterizes the spread of light sheet field along the propagation direction. Finally, intensity plots are carried out to determine the approximate dimension of the light sheet PSF or the effective trapping region/zone. Note that the intensity profiles were extracted directly from the same images that were used to construct the 3D intensity fields. The size of the trap zone realized by the light sheet is calculated to be 40.41 μm×51.32 μm (Lx×Lz) in the XZ plane, and has a thickness of 4.12 μm. This is the effective planar zone that can be used for trapping the objects (dielectric bead/cell). To access the effect of drift, we have used two different kinds of beads of varying sizes (2 μm silica beads and 5 μm polystrene beads). The beads were followed over time and the values are calculated separately for X and Z. The same is shown in Fig. 2D. The mean is calculated to be 0.42 ± 0.16 μm and 0.41 ± 0.11 μm, for X and Z, respectively. In addition, we have carried out a computational study to determine localized heating. We considered a light of wavelength 1064 nm focused by an objective lens (50X, 0.5 NA) onto the specimen (beads suspended in water). Three different samples are considered for the computational study: Silica beads (refractive index 1.444 and thermal conductivity 1.4 W/mK of size 2 μm) and polystyrene beads (refractive index 1.580 and thermal conductivity 0.12 W/mK of sizes 1.5 and 5 μm). The suspension medium is milliQ water of thermal conductivity ~0.6 W/mK. The study is conducted following the model reported by Erwin J. G. Peterman et al.27. The study is carried out over a power range (at the focus) of 25–250 mW, as shown in Fig. 2E. It is evident that the change in temperature is nearly linear over the study range. The maximum experimental power (at the focus) used in the study is 103.4 mW. The trap laser induces heating at a rate of 2.83 K/mW, 2.17 K/mW, 4.81 K/mW for 1.5 μm polystyrene, 2 μm silica and 5 μm polystyrene beads, respectively. To facilitate a better understanding of how the gradient forces are acting on an object trapped in a light sheet trap, we have shown a pictorial representation in Fig. 2F. This may help better understand the working of 2D planar trap.

Light sheet PSF characterization. A Schematic of the optical setup used for recording the light field at and about the focal plane. B The 3D lightsheet field was obtained by stacking all the recorded intensity images at regular Z-interval of 2 μm. Alongside two different views (XZ and YZ) of the field are also shown. C Light intensity plots determine the size of the sheet of light to be 51.32 μm × 40.41 μm (Lz × Lx) with a thickness (Ly) of 4.12 μm. In addition, the thickness (measured in terms of FWHM) of the lightsheet PSF at different distances from the focus (−20 μm, −10 μm, 0, +10 μm, +20 μm) is also calculated. D Drift correction (using 2 μm silica beads and 5 μm polystrene beads) along X and Z axes along with calculated mean values. E Computational modeling of thermal load with incident laser power for three different beads (2 μm silica, and polystrene beads (1.5 μm and 5 μm)). The actual experimental power (at the sample) is also indicated. F A pictorial representation of the gradient force acting on an object in a light sheet trap.

Trap stiffness along X and Z axes

Efficient trapping depends on several factors, including the strength of the optical field. Since it is a two-dimensional trap, the stiffness needs to be calculated along both X and Z axis. To calculate the stiffness values, we have used a technique similar to that in LOT25, where camera frames are used to identify a sudden pull caused by the 2D trapping potential zone. In general, the beads exhibit free Brownian motion in the medium. Turning ON the trap laser at t=0 causes the nearby beads to move towards the trap zone. The journey from time t = 0 to the trap potential zone is recorded by a sensitive high-speed sCMOS camera (Zyla 4.2, Andor Inc, UK). The time and the distance traveled by the bead for the entire journey are calculated from the number of frames recorded. From the video, several free beads are identified and tracked to the trap zone.

Since trap stiffness is desired at larger displacements, determining the region over which the stiffness is constant requires the bead to fall under the pull of the trap. This video-based technique records data continuously, giving the time and the distance over which the particle is pulled to the trap zone. Similar techniques are used to estimate trap-stiffness at large displacements25,28,29,30. More details can be found in the method section. Existing calibration methods based on thermal fluctuations provide trap-stiffness near the equilibrium position of the trap and may not be applicable over large regions as required by the 2D light sheet trap31,32,33. One such method is the variance-based equipartition method that relies on thermal fluctuation. The details are discussed in the methods section, and the results are shown in Fig. 3E–L.

Trap stiffness along X and Z direction in the Trap-zone: a typical dielectric bead tracked as it crosses from free zone (no-potential) to the trap-zone (potential) along (A) X-direction, and (B) Z-direction. C Average distance tyravelled by the particles in free zone, trap zone and at transition. D The bar-plot shows corresponding average trap stiffness (kx = 0.78 ± 0.021 pN/μm, and kz = 1.173 ± 0.034 pN/μm) is calculated from tracked particles as it cross-over from free zone to trap zone. (E–L) The track-plot of the Brownian motion of few beads (of different kind and size) and cells are shown along with the calculated trap-stiffness for all the bead and cell types (HeLa, HEK, NIH3T3). ANOVA statistical analysis is carried out to determine the mean, variance and statistical significance. The sample size is 15.

Near the trap-zone, the force can be approximately modeled by Hooke’s law, and the restoring/gradient force is given by, FG = − kx, where k is the trap stiffness (N/m) and x is the distance. The other force acting on the bead during its directed motion to the potential zone is the viscous force experienced by the bead moving through the medium, i.e, FV = 6πηrbv where, η, rb and v are the medium viscosity, bead radius (assuming spherical) and velocity, respectively. The bead experiences these forces (gradient force and viscous drag force) which are opposite to each other. Balancing these forces produces k = 6πηrb/t, where t = x/v, with x as the displacement of the bead and t as the time taken for the journey. Note that this is an approximate formula where buoyancy and the effect of gravity are neglected, thereby ruling out forces due to weight.

From the particle–track plots, it is apparent that the beads approaching the boundary (between free zone and trap zone) undergo a sudden pull towards the trap zone. Once inside the zone, the beads do not feel any net force, which is due to the negligible gradient force as a result of uniform intensity. The time taken during the process, i.e., the particle experiencing the gradient force and ultimately reaching the trap zone, determines the trap stiffness. This is true for particles crossing from both X and Z directions for which the trap stiffnesses are kx and kz, respectively. During the process, the dielectric beads are tracked as they move from the free-zone to the trap-zone (see Supplementary Video 1). Figure 3A, B shows a typical dielectric particle being suddenly trapped by the trap zone while crossing the boundary along X and Z directions, respectively. The time-taken for the journey is determined from the number of recorded frames (4 frames along X and 3 frames along Z) which is calculated to be, 57.1 ms and 28.5 ms for X and Z, respectively (see Fig. 3C for average distance). For our case, the beads are assumed spherical and have a diameter of 2 μm, and a density of ~2000 kg/m3. So, the mass of the bead is m = ρV where the volume of the bead can be calculated using the formula \(V=4/3\pi {r}_{b}^{3}\). Given the viscosity of deionized water to be η = 0.8925 × 10−3 Pas, the approximate trap-stiffness is calculated to be, kx = 0.78 pN/μm along X-axis and kz = 1.17 pN/μm along the Z-axis (see Fig. 3D).

In addition, we employed a variation-based equipartition method to determine the trap stiffness. The details of the method are discussed in the section “Variance based Equipartition Method”. Figure 3E–G shows the track-plots of a particle trapped in light sheet. Using the equipartition method, the trap-stiffness is calculated for two different kinds (silica and polystrene) of beads of three different sizes, 1.5 μm, 2 μm, and 5 μm, as shown in Fig. 3H. The same experiment is carried out for HeLa, NIH3T3 and HEK cells and the track plots along with the calculated trap-stiffness are shown in Fig. 3I–L. Overall, the study reveals a trap-stiffness in the range, 0.34–0.38 pN/μm for beads and 0.33–0.52 pN/μm for cells. This is close to the trap-stiffness values obtained using video-based methods.

Trapping dielectric beads and cells in a plane

To validate the working of the system, two different objects (living and non-living) are trapped in a plane. First, we choose to trap microscopic dielectric silica beads (spherical, size ~2 μm) suspended in deionized water, and live HEK 293T cells (nearly spherical, size ~ 10–17 μm) in a cell medium. Figure 4A shows the trapping of beads in an effective potential zone/region generated by light sheet PSF (see white rectangle). The size of the trap-zone is found to be approximately, Lz × Lx = 51.32 μm × 40.41 μm = 2073.84 μm2 in the ZX plane. To trap beads, the trap-laser is turned ON, and the video of the entire trapping process is recorded (see Supplementary Video 1). We have chosen to show images at a few chosen time-points beginning from t = 1.2–348.95 s (see Fig. 4A). At time t = 1.2 s, only 4 beads appear to be in the trapping zone. The subsequent frame at t = 72.9 s shows several beads trapped in the zone. With increasing time, more beads (>50) are seen trapped in the trap zone. Finally, at t = 348.95 s, the beads can be seen trapped in a selective single layer/plane. Turning off the trap laser shows a sudden fall of dielectric beads. The entire process is captured in Supplementary Video 1. To further test the trapping process in a dynamic environment, the trapping laser was switched ON/OFF several times, the results of which are shown in Fig. 4B. It is evident that the beads are gradually getting trapped in the trap-zone (roughly shown by the yellow rectangle) during ON cycle (trap laser ON). However, they no longer stay in the trap zone during OFF cycle. The ON/OFF experiment is repeated several times and optical 2D trapping is confirmed. The corresponding imaging data showing the repeated trapping process is shown in Supplementary video 2. In addition, trapping was carried out at varying bead concentrations ranging from low (1/20th) to high (1/5th) of the stock concentration (104 beads/μL) (see Fig. 5). In all the cases, trapping is quite evident although the rate at which the beads are trapped by the light sheet differs. Moreover, we noticed that the beads form line-like patterns at high bead concentration, which is surprising. Alongside, bead tracking is carried out on its way to the region of influence (defined by light sheet PSF). This shows the characteristic nature of the trap induced by light sheet PSF. Overall, these experiments conclusively show the two-dimensional stable trap realized by the light sheet PSF.

A Trapping dielectric beads in a lightsheet plane: a drop of dielectric beads suspended in deionized water is injected into a closely spaced sample holder (see schematic diagram). The sample is then subjected to a sheet of light causing a trap potential region/zone (marked by a white rectangle). The beads (size ~ 2 μm) are attracted by the potential. Over time (from 1.2–349.95 s), a single 2D layer of beads appears to form. The enlarged region is also shown. B Repeated 2D trapping and release of dielectric beads by the lightsheet PSF. ON and OFF state correspond to switching state of trap laser. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Concentration studies on dielectric beads: The dielectric beads were trapped at varying concentrations ranging from 0.05C to 0.2C of the stock solution (C = 104 beads/μL). The full-frame, along with the enlarged trap region (marked by a white dotted rectangle), is also shown. The corresponding tracking data for the trapped beads are also shown on the right side. Scalebar = 10 μm.

Subsequently, we have chosen to work with live specimens such as live 293T cells, as shown in Fig. 6A. In the initial frame at t = 4.24 s, only two cells are seen trapped in the light sheet trap zone. Subsequent frames show an increase in the number of cells trapped in the trap zone, with a maximum of 6 cells at t = 60.9 s. Compared to dielectric beads, the number of trapped cells is less, which can be attributed to its large size (approximately 5 times larger than the beads). In addition, the cells were tracked on their way to the trap zone. It is observed that the average distance traveled by the cell from the initial position in the free zone (at t = 4.24 just outside the trap zone) to the trap zone is longer (~68.24 ± 10.68 μm) as compared to average distance inside the trap-zone (see Fig. 6A). Once the cells are trapped, they continue to exhibit constrained Brownian motion as apparent from the short random displacements (~8.84 ± 4.23 μm) between time-points. At the end (t = 60.9 s), all the cells were clearly seen trapped in a single plane/trap-zone, realized by light sheet PSF. The entire process of cell getting trapped in the trap zone is shown in Supplementary video 3. The same process is carried out to trap other kinds of cells such as NIH3T3 and cancerous HeLa cells. Figure 6B, C shows stable trapping of NIH3T3 and HeLa cells in the trap-zone realized by light sheet. The cells were subjected to ON/OFF state of trapping laser light. During the ON state, the cells were seen pulled to the trapping zone (marked by red square). The process is rather slow compared to dielectric beads. It took almost 47 s and 42 s for trapping 6 NIH3T3 and HeLa cells to enter the trap-zone. Note that trapping strongly depends on the concentration of cells in the solution, as the number of cells approaching the vicinity of the trap matters. As soon as the trapped laser is switched off (OFF state), the cells rapidly fall to the bottom of the trap, as shown in Fig. 6B, C. This demonstrates efficient trapping of live cells in a selective light-sheet plane. The entire trapping process is captured in Supplementary videos 4 and 5.

Trapping HEK 293T cells in a Lightsheet Plane: (A) 293T cells suspended in the medium are subjected to the sheet of light (marked by a white rectangle). With time, the cells get randomly trapped in a 2D plane (realized by the sheet of light). The enlarged region, along with time, is also shown. Alongside, track plot and distance bar-plot are also shown for t = 4.24–60.9 secs. The long-distance (68.24 ± 10.68 μm) indicates sudden pull by the trap zone, whereas the short distance (8.84 ± 4.23 μm) within the trap zone suggests Brownian motion exhibited by the object (cell). B, C In addition, the trapping of NIH3T3 and HeLa cells in the lightsheet plane is realized. The cells suspended in the culture medium were subjected to the sheet of light (marked by a red rectangle). With time, the cells get randomly trapped in the 2D plane (realized by the sheet of light). Scale bar = 20 μm.

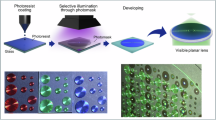

Trapping and fluorescence imaging on the Go

Carrying out high-resolution imaging of freely moving live cells is key to understanding their behavior and has wide implications in biology. This allows behavioral studies and constraint-free interrogation of live species. To accomplish this, the planar trap is operated in fluorescence mode where live NIH3T3 cells in the medium were trapped and imaged on the go. Figure 7A shows the modified optical trap system where an additional optical arm is coupled to the existing system for fluorescence imaging. There are two arms, first the white light illumination sub-system for visualizing trapped objects (beads or cells) and second, the fluorescence sub-system for exciting fluorescently labeled organelles in the trapped cell. Specific filters (notch (NF) and bandpass (B)) are introduced in the detection arm to eliminate background and the source light (473 nm). The picture of the actual optical setup and related details are discussed in Supplementary Note 6. The lipid droplets in the NIH3T3 cells were labeled with Bodipy (Molecular Probes, USA) using the developed protocol as discussed in the section “Labeling Lipids in a Cell”. Figure 7B shows the simultaneous trapping and imaging of multiple cells. The frame at 3.40s shows a single cell being trapped while other cells are in the vicinity of the trap. With time, more and more cells get trapped in the selected plane (realized by light sheet) as shown in images taken at t = 7.43 s, 13.3 s, 15.77 s, 23.63 s (see Fig. 7B). An approximate region of interest (trap-zone) is marked by a yellow rectangle. In addition, an enlarged view of trapped cells is also displayed. The images clearly show the spatial distribution of lipid droplets in the cell membrane, revealing the sub-cellular resolution of the system. The entire video of selective plane trapping and fluorescence imaging of NIH3T3 cells is shown Supplementary video 6. It is evident that cells can be trapped and imaged on the go. Such a capability will push the limits of cell manipulation and its interrogation in their natural environment.

Trapping and imaging on the go. A Optical setup for trapping and imaging. B NIH3T3 cells suspended in the medium are subjected to the sheet of light (marked by a yellow rectangle). With time, the cells get trapped in a 2D plane (illuminated by the sheet of light), which is followed by fluorescence imaging using a dedicated fluorescence module integrated into the trap system. A few enlarged images of cells (marked by a white arrow) are also shown. The entire trapping process is shown in Supplementary video 6. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Conclusion and discussion

Trapping cells in a selective plane is an incredible development that brings in new possibilities both in physical and biological sciences. To achieve this feat, a new kind of optical trap system (called planar optical trap) is developed26. Unlike existing point-based traps, the developed system allows trapping objects in a 2D plane. The technique facilitates touch-free manipulation of several objects in a plane. To demonstrate this, the system is used to trap objects such as dielectric beads and live cells (NIH3T3, HEK 293T, and HeLa cells) in a single plane, allowing for the study of their physical and biological interactions.

Here, we report the first two-dimensional planar optical trap realized by a sheet of light. The technique allows interrogation of multiple non-living (such as dielectric beads) and living (such as Cells) specimens in their natural environment. A 1064 nm infrared light focused by a combination of cylindrical and objective lens is used to generate a diffraction-limited light sheet. The system uses an orthogonal optical configuration with the detection sub-system perpendicular to the trapping sub-system (see Fig. 1). Such a configuration helps direct visualization of the objects trapped in a selective plane.

The advantage of the planar trap system lies in its ability to trap several objects in a selective 2D plane. The resultant light sheet can be better visualized in the volume view as shown in Fig. 2. The size of the light sheet closely resembles a rectangle with a dimension of 51.32 × 40.41 μm2 in the ZX plane. Unlike the existing point-traps, the stiffness has two components for the planar trap, with kz along the propagation direction and kx along X in the lightsheet plane (ZX). To determine the trap-stiffness, video-based technique is employed where particles are tracked from their initial free position to the particle crossing over to the potential zone (see Fig. 3). Near the trap zone, the particle gets suddenly pulled due to the gradient force generated by the intensity difference, causing a directed movement to the trap zone. From the recorded frames, both the travel distance and the time taken are determined, giving an approximate estimate of trap stiffness. Accordingly, the trap-stiffness is calculated to be, kz = 1.17 ± 0.034 pN/μm and kx = 0.78 ± 0.021 pN/μm along Z and X axes. This shows slightly different stiffness along the propagation (Z) axis and other (X) axis. Overall, this demonstrates a selective plane stable 2D trap.

Note that video-based techniques offer accurate determination of trap-stiffness28,29,34,35. In our case, that involves both 2D trapping of multiple beads and fluorescence imaging, which requires video-based position detection. Specifically, the experimental condition (internal flow and cell dynamics) for the present study makes the proposed technique suitable for estimating the trap stiffness. Moreover, video-based techniques allow real-time estimation of trap stiffness across the 2D trap while collecting the data during active experimentation. In short, digitally processing the data (image) obtained from the camera, and the knowledge of single pixel size (obtained by calibrating the video image with a known micrometer ruler), allows the determination of the position of the object with sub-pixel accuracy. On the other hand, the real-time implementation of object tracking using high-speed video cameras improves the time resolution. This ensures accurate estimation of trap-stiffness as per the method discussed in Supplementary Note 7. Overall, this makes video-based techniques among the most accurate techniques. In addition, a comparison of trap-stiffness with other established approaches is shown in Table 1.

Two different kinds of objects are trapped to demonstrate the working of the planar trap system: dielectric beads and live cells. The functioning of the system is shown in a brightfield mode where the trapping is achieved by trap-laser and detection is carried out perpendicular to the trapping sub-system using a separate white light illumination (see Fig. 1). The images of the beads are taken at different time-points beginning from its location in the free-zone (exhibiting Brownian motion) to its travel to the trap-zone (see Fig. 4). The same experiment is carried out for live NIH3T3, HEK and HeLa cells (see Figs. 5 and 6). It is noted that the cells take relatively large time to enter the trap-zone as compared to dielectric beads, which is predominantly due to its large size and mass. The corresponding recorded videos show the entire trapping process of the dielectric bead and live cells, see Supplementary videos 1–5.

The technique is demonstrated by trapping freely moving cells in a selective plane and fluorescence imaging is carried out on the go (see Fig. 7). This is achieved by integrating a separate fluorescence arm to the existing system and using the same widefield detection (with additional emission filters). The recorded video shows freely moving cells in a medium getting trapped in the lightsheet PSF and imaged in a selected plane. More importantly, the images display sub-cellular resolution (see intensity plots in Supplementary Note 6). This is incredible since it allows the interrogation of live cells in their natural environment. To our understanding, the developed system is the first of its kind that allows selective-plane trapping (in a 2D plane) and fluorescence imaging of live cells on the go.

We anticipate that the new planar trap system may find potential applications in biotechnology research. In particular, the technique enables touch-free manipulation of several objects (dielectric beads/cells) confined to a single plane and allows interrogation with sub-cellular resolution.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation and cell culture

Silica beads

Silica dielectric beads in a 5% concentration of 5 ml aqueous solution were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, Germany. The bead size is 2 μm with a standard deviation of 0.2 μm. The beads are diluted in deionized water to 1/10th of the original concentration for carrying the trapping experiment.

Cells

HEK293T (human cells), NIH3T3 (mouse fibroblast cells) and HeLa (cancer cells) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The cells were seeded at a density of 105 cells in 35 mm dishes and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h. The dishes were observed for 70−80% confluency and washed twice with 1X PBS to remove debris. Subsequently, the cells were detached from the dishes using a diluted trypsin solution (1% trypsin in PBS) and collected in a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube, followed by centrifugation for 2 min at 3000 RPM. The pelletized cells were resuspended in 1 ml of cell medium and used for trapping experiments.

Image acquisition and data processing

A fast scientific Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor (sCMOS) camera (Zyla 4.2, Andor Technology Ltd., UK) is integrated into the fluorescence imaging module to collect images of the trapped object. The camera was coupled to the imaging system via a 200 mm focal length tube lens, and image was acquired using the Andor Solis software suite, which provides a graphical user interface (GUI) for precise configuration of imaging parameters including exposure time, gain, frame rate, and region of interest (ROI). For image acquisition, the camera was operated at high exposure time (30 ms) with a quantum efficiency of 0.84 for enhanced sensitivity and minimal background. To increase acquisition speed and reduce data throughput, the image is captured on a camera pixels window size of 550 × 1088 pixels. This limits the sensor readout area while preserves relevant spatial information. Time-lapse fluorescence movies were recorded at a frame rate of 70 frames per second (fps), enabling visualization of cell organelles (lipid droplets) in multiple cells as they enter the trap zone. The fluorescence is collected by the objective lens (0.4 NA, 20X), and focused by the tube lens to the detector (placed at the image plane). On its way, the fluorescence is filtered by a set of filters (bang-pass filter B, ET525/50 M, Chroma, USA and notch-filter, NL, ZET473NF, Chroma, USA). Acquired images were saved in a lossless format (.tif) and processed using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ/Fiji or MATLAB).

Tracking dielectric beads and cells

In general, tracking an object is performed in two steps: (1) Detection and identification of the object’s position, (2) linking of detected objects from frame to frame to estimate their trajectories. Cells and Beads undergoing Brownian motion were tracked using Trackmate GUI available in Fiji36,37. The DoG (Difference of Gaussian) and Simple LAP tracker modules within TrackMate are used for the detection of the cells in individual frames and linking them, respectively. To track the cells, frames were extracted from the trapping video with an average time of 12.77 s between consecutive frames. The acquired frames then undergo background subtraction for better detection. The location of cells on each frame is generated by setting an estimated object diameter of 10 μm for cells and 2 μm using a threshold of 0.5 in DoG filter. Post-detection, the cells need to be linked from frame to frame to acquire the entire track. For this, the LAP tracker (with a linking max distance = 80 μm, gap closing max distance = 10 μm, gap closing max frame = 2 frames) was used.

Detection and identification using DoG filter module

The detection is based on the DoG filter. In this method, an approximate expected particle diameter (d) is fed to the module. It generates two Gaussian filters with standard deviations, σ1, σ2 (with σ2 > σ1) which are used to filter the image stack. This is followed by subtraction, giving a smoothened image with sharp local maxima at particle locations. Each of these maximum acts as a detection spot. This spot is assigned a quality feature by taking the smoothened image value at the maximum. Between two spots with an expected object radius less than d/2, the one with the lowest quality is discarded.

Linking of detected objects using LAP tracker

The linking of detected objects is determined in terms of linking cost. The linking of a spot i (representing a detected object) at frame t and spot j in the consecutive frame t + 1 has a cost. This cost is proportional to the squared distance between the linked spots. In the LAP tracker, the costs of all links between the two frames are minimized as a total and then the objects are linked between the frames. Additionally, links are discarded if the mean object intensity differs largely between two frames. An allowed size of the gap (say 2 frames) specifies if the objects in the subsequent frames appear or disappear.

Labeling lipids in a cell

For the staining of NIH3T3 cells, we chose BODIPY (D3922, Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, Calif, USA) (excitation wavelength 480 nm, emission maxima 515 nm), a lipophilic fluorescent dye specifically designed to stain non-polar lipids. BODIPY was diluted in PBS and a stock concentration of 2 mg/mL was prepared. This stock solution was further diluted 1:250 in PBS to obtain the working concentration needed for staining.

BODIPY interacts with lipid droplets within the cell membranes, allowing for effective visualization of lipid droplets. For the experimental procedure, NIH3T3 cells, which are derived from mouse embryonic fibroblasts, were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Gibco™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The cells were seeded at a density of 100,000 cells per 35 mm dish and were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h. After 24 h, the dishes were monitored until the cells reached 70−80% confluency. The media were then carefully discarded, and the cells were washed twice with 1X PBS to remove any debris. Following the wash, the cells were stained with the prepared BODIPY staining solution and incubated at 37 °C for 45 min to allow the dye to bind effectively to the lipid droplets.

To improve the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) during imaging, a thorough wash with 1X PBS was performed post-staining. Subsequently, the cells were detached from the dishes using a diluted trypsin solution (1% trypsin in PBS) and collected in a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. The cells were then centrifuged at 3000 RPM for 2 min to pelletize them. Finally, the pellet was re-suspended in 1 mL of 1X PBS and prepared for subsequent trapping experiments.

Variance-based equipartition method

The trap potential in an optical tweezer system can also be measured using equipartition theorem which relates particle’s potential energy to its thermal energy31,32,33. This technique allows the determination of trap stiffness, which is a measure of the trap potential’s curvature. In this method, the stiffness of the optical trap was quantified using the variance-based equipartition method, which estimates the trap stiffness from the thermal fluctuations of a trapped bead. This approach relies on the equipartition theorem, which states that, at thermal equilibrium, each quadratic degree of freedom contributes an average energy of \(\frac{1}{2}{K}_{B}T\), where KB = 1.38 × 10−23 J/K is the Boltzmann constant and T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin. In an optical tweezer setup, the optical potential near the center of the trap can be approximated as harmonic. Thus, in one dimension, the potential energy is, \(U(x)=\frac{1}{2}k{x}^{2}\), where x is the displacement of the particle from the equilibrium position, and k is the trap stiffness. Applying the equipartition theorem to this system yields,

where 〈x2〉 is the variance of the bead’s position, representing the mean squared displacement from the equilibrium position.

Trapping experiments were performed using 1.5 μm and 5 μm diameter polystyrene beads, and 2 μm silica beads suspended in aqueous media. The Brownian motion of the trapped beads within the trap was recorded using a sCMOS camera (Andor Zyla 4.2 sCMOS), and particle trajectories were analyzed using the TrackMate plugin in Fiji/ImageJ36,37. The x−z coordinates of individual trapped particles were extracted over time to compute the displacement from the mean position. To calculate the variance, the mean squared displacement (MSD) of each bead relative to its trap center was computed from the recorded video. Specifically, the displacement vector (xi) at several time points, and the corresponding variance x2 was calculated,

where 〈x〉 is the time-averaged position and N is the number of observations (particle displacements during Brownian motion) obtained from the total number of frames. The calculated variance was then substituted into the equipartition equation to determine the trap stiffness k in units of pN/μm. All measurements were performed at room temperature (T ~ 298 K), and care was taken to ensure that drift and external noise sources were minimized.

System calibration protocol

Accurate alignment of the optical system is critical to ensure optical stability of the trapping system. An orthogonal configuration is used to integrate illumination and detection sub-systems. For flexible and precision alignment of the illumination beam, the mirrors and beam-splitters are placed on XY adjustable mounts. This allows easy maneuvering of the trap beam. Once the trap beam is realized and characterized, it is the stage system that requires precision movements. To accomplish this, the sample holding chamber is mounted on a high-precision three-axis nanopositioning stage. This stage enabled fine translational control along the z-axis (depth into the sample) and y-axis (lateral movement perpendicular to the light sheet and along the imaging plane). Translation along the z-axis allowed focusing at different depths, while y-axis movement enabled lateral repositioning of the trapping plane to access different regions of interest. The detection objective itself was mounted on a translation stage, allowing axial (z-axis) adjustments to fine-tune the imaging focal plane and ensure precise alignment with the trapping plane. Subsequently, the sample was illuminated with broadband white light from orthogonal to the trapping arm, transmitted through the coverslip assembly (see Fig. 1). The sCMOS camera (Andor Zyla 4.2 sCMOS) on the detection side was switched on to visualize the focused beads within the sample. Fused silica beads of 2 μm were used as a sample for system calibration. Subsequently, fine tuning was carried out using the nano-positioning stage to align the light sheet with the central plane of the sample fluid, typically situated near the midplane between the two coverslips. The goal was to ensure that the maximum intensity region of the light sheet coincided with the imaging focal plane and the desired trapping region. This step was critical for achieving optical stability of the trapping and detection subsystems, thereby maximizing trapping efficiency and ensuring high spatial resolution during experiments.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Datasets generated and analyzed in this manuscript are given as Supplementary Data 1. The raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Tian, Y. et al. Multi-trap optical tweezers based on composite vortex beams. Opt. Commun. 485, 126712 (2021).

Preece, D. et al. Independent polarisation control of multiple optical traps. Opt. Exp. 16, 15897–15902 (2008).

Wang, R. et al. Optical trapping of mesoscale particles and atoms in hollow-core optical fibers: principle and applications. Light Sci. Appl. 14, 146 (2025).

Martínez, I. A. & Petrov, D. Force mapping of an optical trap using an acousto-optical deflector in a time-sharing regime. Appl. Opt. 51, 5522–5526 (2012).

Ashkin, A. Acceleration and trapping of particles by radiation pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 24, 156 (1970).

Ashkin, A., Dziedzic, J. M., Bjorkholm, J. E. & Chu, S. Observation of a single-beam gradient force optical trap for dielectric particles. Opt. Lett. 11, 288 (1986).

Ashkin, A., Dziedzic, J. M. & Yamane, T. Optical trapping and manipulation of single cells using infrared laser beams. Nature 330, 769 (1987).

Spyratou, E. et al. Measurements of liposome biomechanical properties by combining line optical tweezers and dielectrophoresis. J. Lipid Res. 25, 202–210 (2014).

Rogers, W. B. & Crocker, J. C. A tunable line optical tweezers instrument with nanometer spatial resolution. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 85, 043704 (2014).

Biancaniello, P. L. & Crocker, J. C. Line optical tweezers instrument for measuring nanoscale interactions and kinetics. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 77, 113702 (2006).

Bustamante, C., Alexander, L., Maciuba, K. & Kaiser, C. M. Single-molecule studies of protein folding with optical tweezers. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 89, 443 (2020).

Zaltron, A. et al. Optical tweezers in single-molecule experiments. Eur. Phys. Jl. 135, 896 (2020).

Stigler, J., Ziegler, F., Gieseke, A., Gebhardt, J. C. & Rief, M. The complex folding network of single calmodulin molecules. Science 334, 512–516 (2011).

Cecconi, C., Shank, E. A., Bustamante, C. & Marqusee, S. Direct observation of the three-state folding of a single protein molecule. Science 309, 2057–2060 (2005).

Maillard, R. A. et al. ClpX(P) generates mechanical force to unfold and translocate its protein substrates. Cell 145, 459–469 (2011).

Aubin-Tam, M. E., Olivares, A. O., Sauer, R. T., Baker, T. A. & Lang, M. J. Single-molecule protein unfolding and translocation by an ATP-fueled proteolytic machine. Cell 145, 257–267 (2011).

Avsievich, T. et al. The advancement of blood cell research by optical tweezers. Rev. Phys. 5, 100043 (2020).

Lee, S.-H., Roichman, Y. & Grier, D. G. Optical solenoid beams. Opt. Express 18, 6988–6993 (2010).

Shanblatt, E. R. & Grier, D. G. Extended and knotted optical traps in three dimensions. Opt. Express 19, 5833–5838 (2011).

Roichman, Y. & Grier, D. G. Projecting extended optical traps with shape-phase holography. Opt. Lett. 31, 1675–1677 (2006).

Faucheux, L., Bourdieu, L., Kaplan, P. & Libchaber, A. Optical thermal ratchet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 1504–1507 (1995).

Woerdemann, M. Alpmann, C., Esseling, M. & Denz, C. Advanced optical trapping by complex beam shaping. Las. Phot. Rev. 7, 839–854 (2013).

Rodrigo, J. A., Alieva, T., Abramochkin, E. & Castro, I. Shaping of light beams along curves in three dimensions. Opt. Exp. 21, 20544–20555 (2013).

Paralı, U., Üstün, K. & Giden, I. H. Enhancement of optical levitation with hyperbolic metamaterials. Sci. Rep. 14, 1734 (2024).

Mondal, P. P., Baro, N., Singh, A., Joshi, P. & Basumatary, J. Lightsheet optical tweezer (LOT) for optical manipulation of microscopic particles and live cells. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–10 (2022).

Baro, N. & Mondal, P. P. Planar optical tweezer trap (2D-LOT) system realized by light sheet illumination and orthogonal widefield detection. BioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.04.15.589441v1 (2024).

Peterman, E. J., Gittes, F. & Schmidt, C. F. Laser-induced heating in optical traps. Biophys. J. 84, 1308–1316 (2003).

Lugowski, R., Kolodziejczyk, B. & Kawata, Y. Application of laser-trapping technique for measuring the three-dimensional distribution of viscosity. Opt. Commun. 202, 1 (2002).

Pesce, G., Sasso, A. & Fusco, S. Viscosity measurements on micron-size scale using optical tweezers. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 76, 115105 (2005).

Sarshar, M., Wong, W. T. & Anvari, B. Comparative study of methods to calibrate the stiffness of a single-beam gradient-force optical tweezers over various laser trapping powers. J. Biomed. Opt. 19, 115001 (2014).

Visscher, K., Gross, S. P. & Block, S. M. Construction of multiple-beam optical traps with nanometer-resolution position sensing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2, 1066–1076 (1996).

Jun, Y. et al. Calibration of optical tweezers for in vivo force measurements: how do different approaches compare. Biophys. J. 107, 1474–1484 (2014).

Neuman, K. C. & Nagy, A. Single-molecule force spectroscopy: optical tweezers, magnetic tweezers and atomic force microscopy. Nat. Methods 5, 491 (2008).

Liu, S., Qu, Z., Zhao, X. & Wang, J. L. Fast and versatile optical force measurement with digitally modulated stimulus in holographic optical tweezers. Opt. Laser Tech. 167, 109809 (2023).

Bustamante, C. J., Chemla, Y. R., Liu, S. & Wang, M. D. Optical tweezers in single-molecule biophysics. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 1, 25 (2021).

Tinevez, J. Y. et al. TrackMate: an open and extensible platform for single-particle tracking. Methods 115, 80–90 (2017).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Bhebhe, N. et al. A vector holographic optical trap. Sci. Rep. 8, 17387 (2018).

Andrade, U. M. S., Garcia, A. M. & Rocha, M. S. Bessel beam optical tweezers for manipulating superparamagnetic beads. Appl. Opt. 60, 3421–3429 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the parent institute (Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.P.M. conceived the idea. N.B, P.P.M. carried out the experiments. N.B. prepared the samples. N.B. and P.P.M. analyzed the results and prepared the figures. P.P.M. wrote the paper by taking inputs from N.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Marco Fritzsche and Kaliya Georgieva.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baro, N., Mondal, P.P. Planar lightsheet optical tweezer pLOT for 2D trapping and imaging of freely-moving live cells. Commun Biol 8, 1763 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09147-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09147-9