Abstract

Geleophysic dysplasia (GD) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by severe cardiorespiratory dysfunction and poor prognosis. With no cure available, current treatments focus on symptomatic management. Using a cellular model of ADAMTSL2 p.A165T variant, our screening of 2,321 FDA-approved drugs identified several glucocorticoids, particularly betamethasone dipropionate (BMD), which significantly enhance secretion of two crucial proteins for GD, ADAMTSL2 and FBN1 while improving extracellular matrix organization. In a mouse model carrying the Adamtsl2 p.A165T variant, we observed a high early mortality rate, mirroring the short lifespan seen in GD patients. Around only 60% of homozygous p.A165T mice survived beyond two days after birth, while hemizygous p.A165T/- mice had an even lower survival rate of 40%. Notably, BMD administration at birth significantly improved survival rates to 80% and 69%, respectively. These findings suggest that BMD offers a promising therapeutic approach to prevent early mortality in GD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Geleophysic dysplasia is a rare and progressive inherited disorder characterized by skeletal abnormalities, short stature, joint limitations, thick skin, and a distinguishing facial appearance. Additional clinical characteristics include cardiorespiratory dysfunction with a poor prognosis. Patients with GD often have a short lifespan, with one-third of patients dying before age five years1,2. Most common manifestations reported include a combination of cardiac, upper airway, and pulmonary dysfunction1,2, with an urgent unmet need to identify means for preventing immature death.

Three genes have been associated with GD, resulting in clinically indistinguishable forms of the disorder. Geleophysic dysplasia type-1 (GD1, GPHYSD1, OMIM ID 231050) is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous variants in the ADAMTSL2 gene (OMIM ID 612277), likely resulting in the loss of function1,3. Geleophysic dysplasia type-2 (GD2, GPHYSD2, OMIM 614185) is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by variants in exon 41 or 42 of FBN1 (OMIM 134797)4. Geleophysic dysplasia type-3 (GD3, GPHYSD3, OMIM 614185) is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by LTBP3 variants (OMIM 602090)5. All three genes encode proteins involved in the tissue microfibrillar network, which is a core component of the extracellular matrix (ECM)1. Studies have shown that the poor secretion of ADAMTSL2 or FBN1 variants affects the organization of ECM3,6 and also the availability of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) in fibroblasts from affected individuals3,4,7,8. All these studies suggest the disruption of the microfibrillar network as a possible cause of GD; however, the underlying molecular mechanism for GD has not yet been elucidated. There is no cure for GD, and treatments are focused on managing specific symptoms, including cardiac and respiratory dysfunctions1.

A genotype-phenotype correlation within patients with GD1 has not been reported. However, our recent study showed that the clinical severity of GD1 is correlated with the abundance of ADAMTSL2 in the ECM9. Although GD1 and GD2 are clinically and genetically heterogeneous disorders, to date, no significant differences in major clinical or radiological features have been observed between patients carrying ADAMTSL2 variants and those with FBN1 variants1. Researchers and medical professionals have deposited 352 different variants, only for the ADAMTSL2 gene, into ClinVar, a central and public database hosted by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Most of them are single-nucleotide variations, totaling 294, and 194 with uncertain significance. Only 58 variants have been classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic. The functional consequences of pathogenic ADAMTSL2 variants have been investigated using cellular models transfected with mutated ADAMTSL2 constructs. Mutated proteins have been expressed at normal intracellular levels, but with impaired secretion to the extracellular media1. This impaired protein secretion and the regulation of the TGF-β pathway have been suggested as the molecular mechanisms for GD, but a direct link to the pathophysiology of the disease has not been described in ref. 1.

We recently reported a cellular and mouse model of GD designed to replicate the genetic profile of a GD patient who is compound heterozygous for two ADAMTSL2 variants. The patient is a 6-year-old boy with a prenatal history of polyhydramnios, delivered at term with short stature at birth. After delivery, he was diagnosed with a ventricular septal defect along with mild pulmonary valve stenosis and patent ductus arteriosus, which subsequently evolved to mild pulmonary stenosis only. Clinical evaluation at 1 year old showed short stature, brachydactyly, and bilateral fifth finger clinodactyly. His continuing findings are tip-toe walking with short fingers and toes. He has thickened ear helices and slightly underdeveloped alae nasi. A cardiac echocardiogram shows mild pulmonary valve stenosis9. He has experienced episodes of upper airway disease, but no pulmonary abnormalities have been identified. The two ADAMTSL2 variants, p.R61H and p.A165T, exhibited impaired secretion not only in the HEK-293T overexpression cells, but also in the patient-derived dermal fibroblasts9. Additionally, we found that the p.A165T variant caused a more severe impairment in protein secretion and negatively impacted the secretion of the less pathogenic p.R61H variant9. We also developed and characterized mouse models carrying various allelic combinations of the p.R61H and p.A165T variants. Our results revealed a spectrum of phenotypic severity, ranging from lethality in knockout homozygous mice to mild growth impairment in adult p.R61H homozygous mice, pointing out this variant as the least pathogenic. The homozygous and hemizygous p.A165T mice showed a more severe respiratory and cardiac dysfunction.

This study recognized impaired secretion of mutant ADAMTSL2 as a key defect in Geleophysic Dysplasia and showed that the glucocorticoid betamethasone dipropionate (BMD) significantly improves ADAMTSL2 secretion and ECM protein levels in patient cells. In GD mouse models, BMD treatment improved early survival. These findings support BMD as a potential supportive therapy for GD in particularly in the newborn period.

Results and discussion

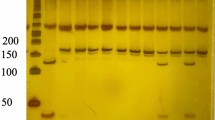

In this study, we established stable expressions of ADAMTSL2 WT and the variants p.R61H and p.A165T in HEK-293 cells. Intracellular and secreted forms of ADAMTSL2 were detected as single bands around 100 kDa and 130 kDa, respectively. The difference in molecular weight is attributed to glycosylation and O-fucosylation required for protein secretion10. Consistent with previous transient expression experiments9, both variants were expressed intracellularly; and reduced secretion into the conditioned media (CM) was observed for the pathogenic variants. Secretion of the p.R61H and p.A165T proteins was reduced to 50.8% and 24.8%, respectively, compared to the WT control (Fig. 1A). The p.A165T variant emerged as the most severe variant in all experiments, and is a prime example of a variant that can lead to severe manifestation in GD.

A HEK-293 cells stably overexpressed ADAMTSL2 (WT) and the p.R61H and p.A165T variants [all fused with a DYKDDDDK (DDK) tag]. All proteins were expressed intracellularly, but a reduced secretion to the CM was observed for the pathogenic variants p.R61H and p.A165T. Original uncropped blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8). Densitometry analysis for 4 independent experiments showed that secretion for the p.R61H and p.A165T proteins was reduced to 50.8 and 24.8%, respectively. Significance was measured using a 1-way Anova test, and values were compared vs ADAMTSL2-WT (*p < 0.05 and ****p < 0.0001). B The DiscoveryProbe™ FDA-approved Drug Library (APExBIO) with 2321 compounds was screened for their ability to increase secretion of p.A165T-DDK to the CM, in a HEK-293-A165T model (Round-1). Secretion of p.165T-DDK was evaluated by an indirect ELISA. A cut-off of 1.5-fold change (FC) revealed 252 compounds that were able to increase p.A165T-DDK secretion. C One hundred and twenty compounds were re-evaluated in Round-2. Red dots indicate compounds with glucocorticoid activity. D BMD and other glucocorticoids strongly up-regulated ADAMTSL2, FBN1, and fibronectin in GD1 patient fibroblasts. E BMD increased the secretion and organization of ECM proteins in GD1 patient fibroblasts. F BMD treatment improves survival in Adamtsl2 mutant mice. Kaplan-Meier survival curve of mice with p.A165T allelic variant in Adamtsl2 with and without BMD treatment during the first 3 months. G The curves were compared with the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test to determine significance. A significant reduction in survival during the first 3 months was expected in Adamtsl2 p.A165T hemizygous (p < 0.0001) and homozygous (p = 0.001) mice vs WT mice. The survival was improved with BMD treatment in Adamtsl2 p.A165T hemizygous (p = 0.002) and homozygous p = 0.3 vs WT mice) and homozygous (p = 0.21 vs untreated and p = 0.22 vs WT mice) (N = number of animals) (WT = Black line, p.A165T homozygous (blue line), p.A165T hemizygous (orange line). No treatment (Continue line) and BMD (discontinued double line). Bars and error bars represent the average and the standard error of the mean (SEM) for all values, respectively.

We reasoned that finding a means to promote ADAMTSL2 secretion could potentially alleviate GD symptoms, especially premature death. For this, we screened 2321 compounds from an FDA-approved drug library (APExBIO The DiscoveryProbe™) for their ability to increase p.A165T secretion. HEK-293 cells overexpressing the p.A165T-DDK variant were used (p.A165T fused with a DDK tag). The ELISA-based detection of p.A165T-DDK in the CM revealed that 252 compounds induced > 1.5-fold increases in p.A165T-DDK secretion, accounting for 10.8% of all drugs tested. To validate this ELISA-based screening method, six compounds that increased p.A165T-DDK secretion were selected. Western blot (WB) analysis of p.A165T-DDK expression in both cell lysates and CM showed a strong increase in secretion of p.A165T-DDK into the CM, with a range of 3.1–6.4-fold changes (Supplementary Fig. 1). Intracellular ADAMTSL2-A165T-DDK was only affected by two drugs (Supplementary Fig. 1).

A total of 120 drugs were selected based on their ability to increase p.A165T-DDK secretion and maintain good cell viability (≥70%) after 7 days of treatment (Fig. 1B). The effect on secretion for these drugs was confirmed or discarded in a second round. Results showed good cell viability, with an average of 90.4%. Proliferation remained unaffected, with an average of 95.2%. Interestingly, 13.3% of the selected drugs (16 out of 120) were found to have glucocorticoid activity. Once again, most of the drugs increased p.A165T-DDK secretion in the HEK-293 overexpression model (Fig. 1C).

The results from both rounds were combined, and the top 50 drugs that increased p.A165T-DDK secretion are shown in Supplemental Table 1. Notably, 30% of all these drugs (15 out of 50) were found to have glucocorticoid activity, highlighting these compounds as potential treatments to increase ADAMTSL2 secretion.

We then tested the top 43 drugs in GD1 patient fibroblasts, and total cell lysates were analyzed to assess the levels of ADAMTSL2 and FBN1, key proteins involved in GD1 and GD2, respectively, as well as fibronectin, which plays a critical role in ECM organization. Immunoblot analyses showed that ADAMTSL2, FBN1, and fibronectin were up-regulated by compounds with glucocorticoid activity (Supplementary Fig. 2A). In total lysates, ADAMTSL2 appeared as three bands where band-1 and band-2 corresponded to the intracellular forms, while band-3 represented the ECM form9. Compounds with glucocorticoid activity, including fluticasone, BMD, and betamethasone valerate, were found to up-regulate the extracellular form of ADAMTSL2 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Interestingly, eight glucocorticoid compounds also up-regulated FBN1, with BMD showing the most significant effect (Supplementary Fig. 2). While ADAMTSL2 and other ADAMTSL proteins are known to interact with FBN1, further studies are needed to fully understand the mechanism underpinning their interactions11. Additional evidence suggests that this interaction may enhance microfibril biogenesis, which would be a beneficial outcome for GD. Fibronectin was also up-regulated by multiple drugs, particularly those with glucocorticoid activity (Supplementary Fig. 2). Since fibrillin assembly requires fibronectin12, up-regulation of this protein may contribute to their therapeutic potential in GD patients. To assess the overall impact of all these drugs on ECM components, we calculated a score based on the fold-change upregulation of these three key proteins. Remarkably, the top ten drugs were all compounds with glucocorticoid activity, with BMD ranking first. Given its strong effect, BMD was selected for further studies in GD patient fibroblasts (Fig. 1D).

We determined the effect of different concentrations of BMD on control and GD1 fibroblasts. BMD strongly up-regulated the ECM organization (Fig. 1E). A more detailed analysis of the ECM proteins showed a significant down-regulation of ADAMTSL2 in the ECM of patient fibroblasts when compared with control cells, while intracellular ADAMTSL2 showed no difference, suggesting an impaired secretion for the p.R61H and p.A165T variants. However, BMD treatment strongly up-regulated ADAMTSL2 in the ECM of patient fibroblasts, while exerting no obvious effect on the intracellular protein (Supplementary Fig. 3), suggesting an improvement in the mechanism related to the secretion and/or incorporation of ADAMTSL2 into the ECM network. Similarly, GD1 patient fibroblasts showed a strong down-regulation of FBN1 protein, which correlated with a poor secretion and/or organization of this key protein in the ECM. BMD strongly up-regulated FBN1, not only intracellularly but also in the ECM (Supplementary Fig. 3). We also studied fibronectin in both control and GD1 patient fibroblasts. No difference was found for the intracellular expression of fibronectin, but a strong down-regulation of this protein was found in the ECM of GD1 patient fibroblasts, which suggests an impaired secretion of fibronectin in these cells. BMD not only up-regulated fibronectin protein level in both control and GD1 patient cells intracellularly but also increased the incorporation of fibronectin in the ECM from GD1 patient fibroblasts (Supplementary Fig. 3).

BMD has been used in humans for the treatment of asthma, Crohn's disease, arthritis, psoriasis, preterm infants, and other diseases. Our drug screening indicates that BMD, among other glucocorticoids, is a possible treatment for GD. To test the effects of BMD injection in vivo, we took advantage of our previously generated GD animal models. Mice that are homozygous or hemizygous for the p.A165T missense variant were selected for treatment due to their phenotypic severity, i.e., significantly reduced survival, abnormal growth, and cardiopulmonary manifestation9. BMD (5 g/kg) was injected subcutaneously to newborn mice and monthly thereafter. To test the efficacy of the treatment, survival was considered as the primary endpoint, while weight and cardiac outcome were secondary endpoints. A detailed calendar for animal studies is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. Significantly reduced survival, with increased mortality in the first month, was present in homozygous (59%, p = 0.001) and hemizygous (44%, p < 0.0001) p.A165T mice when compared to WT. However, survival increased in treated mice to 80%, p = 0.22 and 75%, p = 0.30 in homozygous and hemizygous mice, respectively, as shown in Fig. 1F. In addition, mortality rates for all genotypes were stable in the following months with no differences between genotypes nor treatment status for more than 6 months, suggesting that BMD injection was enough to overcome the newborn lethality in GD mouse model. To test if prenatal treatment could further improve the survival, hemizygous mice p.A165T mice were treated at E18 by subcutaneously injecting a single dose of BMD (2.5 g/kg) into their dams. During the first 20 days, the survival was 81% (Supplementary Fig. 5). Growth was monitored by weekly weight recordings during the first month and monthly thereafter. Homozygous and hemizygous p.A165T animals showed significantly reduced weight, starting from 3 to 4 weeks of age, when compared to WT, regardless of the treatment status (p = 0.015, p < 0.001, and p < 0.001 in male A165T homozygous at 22, 66 and 96 days, and p < 0.0001, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001 in male A165T hemizygous at 22, 66 and 96 days) (Supplementary Fig. 6A). However, during the first 3 weeks, all BMD-treated mice (WT, p.A165T hemizygous, and homozygous male mice) showed further reduction in weight gain that was significant when compared with non-treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 6B) (p = 0.03, for WT, p < 0.001 for A165T homozygous, and p = 0022 for A165T hemizygous at 22 days of age). This reduction of body weight is likely due to a unique effect of glucocorticoids in rodents. A recent meta-analysis study of 202 studies done with newborn rodents (mice, rats, and guinea pigs) showed a reduced body weight with corticosteroids, more noticeable in animals treated before 15 days of age13. The weight reduction normalized to their respective WT mice was less severe in mice treated with BMD than non-treated animals (Supplementary Fig. 6B). This suggests a modest effect of BMD on the body weight of mutant animals.

Cardiac valvular dysfunction in GD is common in humans2. Our previous echocardiogram data showed that homozygous p.A165T mice presented with progressive cardiac dysfunction9. We performed echocardiograms on our treated and non-treated p.A165T homozygous mice at 6 months of age. We found that the mitral, aortic, and pulmonary valves had dysfunction regardless of the BMD treatment, as indicated by the significant changes in mitral valve E/E’, aortic valve diameter, and pulmonary valve peak pressure (Supplementary Fig. 7G, I, K), suggesting that cardiac valve abnormalities in surviving animals continue under BMD treatment.

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the potential therapeutic opportunities for GD in particularly in the newborn period. We demonstrated that the impaired secretion of ADAMTSL2 and other ECM components, including FBN1 and fibronectin, in GD1 patient fibroblasts can be rescued by glucocorticoid compounds, particularly BMD, which was identified through an extensive drug screening. BMD injections in p.A165T homozygous and hemizygous mice show an improvement in early postnatal survival. Prenatal treatment at E18 in p.A165T hemizygous mice also shows an improvement in early postnatal survival. However, we did not see a significant improvement with the cardiac manifestation or growth after BMD treatment, suggesting that BMD is unable to prevent these manifestations or that the treatment was too late in development to prevent any damage. Another possibility is that in vivo, an increased secretion of ADAMTSL2 by BMD is not what is causing the improvement in survival, but instead is doing it by other well-known properties like immunosuppression, anti-inflammation, acceleration of lung maturation, or by increased secretion of surfactant. The positive effects of postnatal corticosteroids on lung development are well described14,15. Thus, improvement of lung abnormalities may be a reasonable explanation for the reduction of mortality in our Adamtsl2 mutant mouse models. It is possible that BMD supports pup survival through a vulnerable postnatal phase characterized by pulmonary and cardiac compromise, rather than directly ameliorating the dysfunction of mutant Adamtsl2. Our results strongly suggest that BMD can be a life-saving treatment to overcome early lethality in GD1 and should be considered in patients with severe manifestations of GD1 in the neonatal period.

Methods

Study approval

All studies were reviewed and approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board (IRB) and by the University of Miami Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (AICUC), according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines (NIH). We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. Unaffected (control) and GD1 individuals were phenotypically evaluated at the University of Miami. Written informed consents were obtained from parents prior to enrollment into the study. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

Materials

BMD from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). BMD injections have been tested in humans, dogs, rabbits, and rats14,16,17. Long-term pharmacokinetic studies in humans have shown that the drug is still detected 28 days after injection13,14. A single dose of 0.1 mg subcutaneous BMD has been shown to have a long-term effect on the offspring of a mouse model for lung maturation14. Based on these previous studies, we decided to inject BMD subcutaneously (5 g/kg) into newborn mice. With the animals treated at E18, we found that this concentration caused large ulcers in the injection site of the dams, so the concentration was reduced (2.5 g/kg) to avoid this side effect. Diluted to 0.5 µg/µL and injected into newborn subcutaneously using the NanoFill Sub-Microliter Injection System (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL).

HEK-293 transfection

HEK-293 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, CRL-1573) (Manassas, VA). Cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 atmosphere, using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) high glucose, pyruvate, containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL of penicillin, 100 μg/mL of streptomycin. The media was changed every 2–3 days. HEK-293 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine3000 following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, one million cells were cultured in 6-well plates and transfected after 24–48 h with 70-80% confluency. ADAMTSL2-WT or mutated ADAMTSL2-R61H and ADAMTSL2-A165T constructs (all in pCMV6, Origene) (0.5 µg), P3000 reagent (2 µL), and Lipofetamine3000 (4 µL) were mixed in 500 µL DMEM (no additives) and incubated at RT for 30 min. Cells were transfected using the DNA/lipid/DMEM mixture for 6 h (500 µL total). Then, 1 mL of DMEM high glucose, pyruvate, 10% Fetal Bovine Serum, 100 units/mL of Penicillin, and 100 µg/mL of Streptomycin was added to the transfected cells. For stable transfection, cells were selected with increasing concentration of geneticin (G418) up to 1 µg/mL. For expression/secretion experiments, half a million cells were cultured in 12-well plates for 72 h. Intracellular lysates (RIPA buffer, Sigma-Aldrich) and CM were used for western blot analysis.

Control and GD1 patient dermal fibroblasts

All dermal fibroblasts were isolated from skin biopsies, following the explant technique. The unaffected individual was a 1-month-old boy, and the GD1 patient was a 23-month-old boy by the time of the skin biopsies. Briefly, tissues were cut into small 1 × 1 mm explants and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 atmosphere, using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) high glucose, pyruvate, containing 20% FBS, 100 U/mL of penicillin, 100 μg/mL of streptomycin, and 200 μg/mL of Primocin. The medium was carefully changed every day until cells migrated from the explants and grew as a monolayer in 6-well plates. Dermal fibroblasts were cryopreserved as passage P2. Thawed fibroblasts for all experiments were cultured in T75 flasks and used in a range from P4-P10 passages. We completed all experiments using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) high glucose, pyruvate, 10% FBS, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin. For protein analysis, half a million cells were cultured in 12-well plates for 7 days, untreated or with the corresponding drug concentration. Total lysates, intracellular lysates, and the ECM protein lysates were used for experiments.

Protein lysates

Protein lysates were prepared using different approaches depending on the experiment goal: total lysates (Total), intracellular lysates (IC), and ECM lysates. Total lysates (Total): were prepared by adding 2× Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad, 1610747) directly to the cells in the wells, previously washed with PBS. Cells were scraped and cell lysates were cleared at maximum speed (14,000 rpm) for 5 min. Intracellular lysates (IC): were prepared using 1× RIPA lysis buffer (Millipore-Sigma, R0278) containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, with 150 mM sodium chloride, 1.0% Igepal CA-630 (NP-40), 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), plus a 1× protease inhibitor mixture (C0mplete™ Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Roche, 11697498001). RIPA was added directly to the cells, and then the cells were scraped and incubated on ice for 15 min. Cell lysates were cleared at maximum speed (14,000 rpm) for 5 min. Protein concentration was determined using a Bradford colorimetric assay kit (Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit-II Bio-Rad, 500-0002). ECM protein lysates: were prepared using the Ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH)/Triton-X100 protocol. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and removed from the plate with 20 mM NH4OH, 0.05% Triton-X100 in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. The remaining ECM proteins attached to the plate were washed with PBS and dissolved in 2× Laemmli buffer as 138.9 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 22.2% (v/v) glycerol, 2.2% LDS, and 0,01% bromophenol blue containing 10% 2-Mercaptoethanol (Sigma).

Western blot analysis

Eight to ten µg of proteins were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), using the appropriate gel, and transferred to a 0.22 µm PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, 1620112). After blocking with 5% BSA in Tris Buffered Saline (TBS-T20, 25 mM Tris, 140 mM Sodium Chloride, and 3.0 mM Potassium Chloride, and containing 0.1% Tween-20), the membranes were incubated with the corresponding primary antibody overnight at 4 °C (Table 1S). We used a polyclonal antibody against the C-terminus of ADAMTSL2 (C3) from GeneTex, and it is the best available antibody. Additional antibodies are described in Table S2. Primary antibodies were detected by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked Antibody, Cell Signaling Technology #7076 and anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked Antibody, Cell Signaling Technology #7074), and the immunocomplexes were visualized by chemiluminescence (Super Signal™ West, Thermo-Fisher Scientific, 34577 and 34096). The membranes were stripped using Restore™ PLUS Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Scientific, 46430) at room temperature, for 15 min, extensively washed with TBS-T20, blocked with 5% BSA in TBS-T20, and reprobed with the corresponding antibodies following a similar protocol.

FDA-approved drug library screening

The DiscoveryProbe™ FDA-approved Drug Library (L1021) was purchased from APExBIO, USA, which consists of 2321 compounds, in twenty-seven 96-well plates, prepared at 10 mM in DMSO, Ethanol, or Methanol. Compounds from plate-1 were initially screened at concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 µM, for 7 days, to assess toxicity on HEK293T-A165T and using EX-CELL™ 293 Serum-Free Medium (Sigma, 21571 C). The viability and proliferation were determined using the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity assay. We first assessed the toxicity of 144 compounds using an LDH assay after treating the cells for 7 days at concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 µM. A concentration of 1 µM was selected, as it resulted in an average cell viability of 73.9% across the tested drugs. In round-1, all 2321 drugs were tested at 1 µM for 7 days. The results showed good cell viability, with an average of 87.8%. Proliferation was unaffected either, with an average of 88.7%.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell viability and proliferation were evaluated using the LDH activity assay (Cytotoxicity Detection Kit PLUS, Roche, 04744926001), a colorimetric test that measures the amount of LDH with the reduction of a yellow tetrazolium salt into a red formazan dye. Cell viability was determined as the percentage of released LDH in the CM compared to the total LDH content in the well. Cell proliferation was determined as total LDH content per well after complete lysis of cells. LDH content at time 0 was considered 100% and the percentage of total LDH per well was calculated.

DDK indirect ELISA

CM were mixed in a ratio of 1:1 with BupH Carbonate-Bicarbonate Buffer (Thermo Scientific, 28382), containing 0.2 M Na2CO3/NaHCO3, pH 9.4. Nunc MaxiSorp™ flat-bottom 96-well micro-plates (Thermo Scientific, 44-2404-21) were coated with 100 µL of the mixture, heated at 75 °C for 15 min, and then overnight at 4 °C. Microplates were blocked with 200 µL of 1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, A9647) in PBS (Thermo Scientific, 46430), at room temperature for 2 h, and washed three times with 200 µL of PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich, P9416), PBS-T20. A165T-DDK was detected with 100 µL of a 1:1000 dilution of the primary antibody anti-DDK rabbit polyclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 14793S), diluted in 1% BSA-PBS, at 37 °C for 2 h and then washed 3 times with 200 µL of PBS-T20. Anti-DDK antibody was detected using 100 µL of a 1:10,000 dilution of anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked antibody (Cell Signaling, 7074) diluted in 1% BSA-PBS, at 37 °C for 1 h and then washed 3 times with 200 µL of PBS-T20. The HRP was detected using 100 µL of 3,3’,5,5’ tetramethylbenzidine from Pierce TMB Substrate Kit (Thermo Scientific, 34021) at room temperature for 30 min, and the reaction was stopped with 100 µL of 2 M sulfuric acid. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured for calculations.

Transgenic mice

For the generation of Adamtsl2 p.A165T missense variant, we developed a knock-in mouse model carrying the variant by conventional embryonic stem cell-mediated knock-in technology using the service of Taconic-Cyagen Model generation Alliance (Germantown, NY), as previously described in ref. 9. Adamtsl2 p.A165T heterozygous mice were crossed between them to obtain homozygous animals or with heterozygous mice carrying a knock-out allele of Adamtsl2 (PMID: 25762570), to obtain hemizygous mice. Mice were genotyped as previously described and housed under a 12-h light-dark cycle at 20–23 °C in specific pathogen-free facilities and supplied with food and water ad libitum. All animal studies and experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. In addition, all reports were in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. All litter, excluding the first one, from different types of matings, were included in these studies until ten animals per group were reached. Adamtsl2 p.A165T/p.A165T and Adamtsl2 p.A165T/- were compared with WT mice. Whole litters were treated with BMD or designated as control, untreated mice.

Survival and growth curves

The survival until 6 months was recorded for all mice. A Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to visualize the survival rate during the first 3 months. To determine significant differences, the curves were analyzed with the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test, which is better at determining significant differences in early time points. For growth curves, the weights at specific time points were recorded and plotted. Graph and Student's T-test done in Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA). The number of animals is indicated in parentheses in the figure.

Echocardiography

Echocardiogram was performed using the Vevo2100 imaging system (VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada) with an MS400 linear array transducer, as done in previous work9. Mice were shaved with depilatory cream one day before the experiments. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 2.5–3% isoflurane at a 0.8 L/min flow rate and maintained with 1–1.5% isoflurane. Following anesthesia, mice were fixed in a supine position on a pad with an integrated temperature sensor, heater, and ECG electrodes. A corneal lubricant will be used to prevent damage due to a lack of blink reflex under anesthesia. Both heart rate and body temperature were monitored constantly (maintained around 37 °C and a heart rate above 450 bpm) during measurement. We used parasternal short (at the level of midpapillary muscles) and long-axis views to obtain two-dimensional B-mode, M-mode, pulse–wave (PW) Doppler, and tissue Doppler images. All data were analyzed using VevoLab 3.3.3 software (Visual Sonics, Toronto, ON, Canada). The number of animals tested at week 24 is indicated in the figure, a few animals died before completion of the test. Graph and one-way ANOVA test done in GraphPad Prism (Boston, MA).

Statistics and reproducibility

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and all graphs were performed in Microsoft Excel. The number of replicates for experiments are indicated in each figure, and statistical differences were tested using the 1-way or 2-way ANOVA test when comparing a group with the corresponding control. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. Replicates represent samples from independent experiments.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the ClinVar repository. Submission IDs for reported gene variants include: ADAMTSL2 c.182 G > A as SUB15022370, ADAMTSL2 c.493 G > A as VCV000524194.4. Uncropped and unedited blot/gel images are included as Supplementary Fig.(s) in the Supplementary Information PDF. All source data underlying the graphs and charts presented in the figures are available as Supplementary Data 1.

References

Marzin, P. & Cormier-Daire, V. Geleophysic dysplasia. In: GeneReviews (eds Adam, M. P. et al.) (University of Washington, Seattle, 1993–2024).

Marzin, P. et al. Geleophysic and acromicric dysplasias: natural history, genotype-phenotype correlations, and management guidelines from 38 cases. Genet. Med. 23, 331–340 (2021).

Le Goff, C. et al. ADAMTSL2 mutations in geleophysic dysplasia demonstrate a role for ADAMTS-like proteins in TGF-beta bioavailability regulation. Nat. Genet. 40, 1119–1123 (2008).

Le Goff, C. et al. Mutations in the TGFβ binding-protein-like domain 5 of FBN1 are responsible for acromicric and geleophysic dysplasias. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89, 7–14 (2011).

McInerney-Leo, A. M. et al. Mutations in LTBP3 cause acromicric dysplasia and geleophysic dysplasia. J. Med. Genet. 53, 457–464 (2016).

Piccolo, P. et al. Geleophysic dysplasia: novel missense variants and insights into ADAMTSL2 intracellular trafficking. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 21, 100504 (2019).

Rypdal, K. B. et al. The extracellular matrix glycoprotein ADAMTSL2 is increased in heart failure and inhibits TGFβ signalling in cardiac fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 11, 19757 (2021).

Chaudhry, S. S. et al. Fibrillin-1 regulates the bioavailability of TGFbeta1. J. Cell. Biol. 176, 355–367 (2007).

Camarena, V. et al. ADAMTSL2 mutations determine the phenotypic severity in geleophysic dysplasia. JCI Insight 9, e174417 (2024).

Zhang, A. et al. O-Fucosylation of ADAMTSL2 is required for secretion and is impacted by geleophysic dysplasia-causing mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 15742–15753 (2020).

Hubmacher, D. & Apte, S. S. Genetic and functional linkage between ADAMTS superfamily proteins and fibrillin-1: a novel mechanism influencing microfibril assembly and function. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68, 3137–3148 (2011).

Sabatier, L. et al. Fibrillin assembly requires fibronectin. Mol. Biol. Cell. 20, 846–858 (2008).

Roberts, D., Brown, J., Medley, N. & Dalziel, S. R. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3, CD004454 (2017).

Stewart, J. D., Sienko, A. E., Gonzalez, C. L., Christensen, H. D. & Rayburn, W. F. Placebo-controlled comparison between a single dose and a multidose of betamethasone in accelerating lung maturation of mice offspring. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 179, 1241–1247 (1998).

Lok, I. M. et al. Effects of postnatal corticosteroids on lung development in newborn animals. A systematic review. Pediatr. Res. 96, 141–1152 (2024).

Kopylov, A. T. et al. Quantitative assessment of betamethasone dual-acting formulation in urine of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis after single-dose intramuscular administration and its application to long-term pharmacokinetic study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 149, 278–289 (2018).

Collins, E. J., Aschenbrenner, J. & Nakahama, M. Biologic action of betamethasone 17,21-dipropionate in rat and dog. Steroids 20, 543–554 (1972).

Acknowledgements

We are immensely grateful to the patients for their participation in this study. This study was supported by a gift from the Al Rashid Family.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.M. designed and conducted cell experiments, acquired and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. V.C. designed and conducted animal experiments, acquired and analyzed data, and reviewed the manuscript. K.W. designed animal experiments, analyzed data, and reviewed the manuscript. G.W. analyzed data and reviewed the manuscript. M.T. designed the research study, analyzed data, reviewed, and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Kaliya Georgieva.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morales, A.A., Camarena, V., Walz, K. et al. Glucocorticoid treatment rescues early lethality in a mouse model of geleophysic dysplasia. Commun Biol 8, 1707 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09148-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09148-8