Abstract

Resting-state functional connectivity (FC) studies have predominantly centered on gray matter (GM), largely overlooking the functional contributions of white matter (WM). However, emerging evidence indicates WM blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals actively shape large-scale brain networks. Current methods to integrate WM face limitations, including challenges in assessing global network properties from bipartite GM-WM connections or the nascent stage of unified connectome models. Here, we introduce the Gray-White Matter Heterogeneous Fusion Network (GWM-HFN), a framework that defines GM-GM functional links via the covariance of their interaction profiles with WM bundles defined by a standardized atlas. Validated across six independent datasets, GWM-HFN demonstrates fair short-term (ICC ~ 0.36) and slight-to-fair long-term (ICC ~ 0.20) test-retest reliability, comparable to conventional GM-based FC. GWM-HFN exhibits distinct topological features, including small-worldness and enhanced modular segregation compared to GM-GM networks, capturing over 40% unique variance and a unique sensitivity to the connectivity patterns that differentiate individuals. Lifespan analyses reveal global linear declines and complex non-linear age effects in GWM-HFN connectivity, with peak connectivity in early adulthood ( ~ 34 years). Clinically, individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) show GWM-HFN-specific hyperconnectivity, which correlates with symptom severity and offers greater sensitivity than GM-GM FC. Furthermore, GWM-HFN connectivity patterns predict individual differences in cognitive performance, notably in language tasks. The GWM-HFN framework provides a robust and more comprehensive approach to understanding WM-mediated neural communication, integrating functional signals across both GM and WM, and offers promising avenues for developing neuroimaging biomarkers for aging and neuropsychiatric disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last twenty years, resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) has emerged as a pivotal tool for mapping synchronized neural activity across various brain regions, mapping synchronized neural activity, commonly termed functional connectivity (FC)1,2. This innovative imaging technique has significantly enriched our understanding of the brain’s functional connectome, which provides a network-level perspective on the interconnections among brain regions. As a result, researchers have gained deeper insights into the large-scale organizational structure of the brain, the trajectories of development and aging, and the alterations associated with neuropsychiatric disorders3,4,5,6.

Historically, the majority of studies focusing on the functional connectome have centered on gray matter (GM), where it is commonly assumed that neural activity drives blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals. This GM-centric focus has inadvertently led to a relative neglect of white matter (WM) in connectivity analyses, primarily due to its lower BOLD signal amplitude and its traditional classification as a mere structural conduit facilitating communication between GM regions7,8,9. However, a growing body of evidence is challenging this long-held perspective. The successful detection of WM functional signals, despite their lower amplitude compared to GM signals, is largely attributable to recent methodological advancements. These include specialized preprocessing pipelines that, for instance, apply separate spatial smoothing to WM and GM to prevent signal leakage, and avoid regressing out the WM signal as a nuisance variable10,11. Such techniques have enabled the reliable characterization of WM functional networks, suggesting that WM plays a more active role in the dynamics of functional networks than previously acknowledged10,12,13,14,15,16.

Recent research, aiming to incorporate WM, has explored several avenues, including WM-only networks, GM-WM interactions, and more unified connectomes, each with its own set of advancements and unresolved challenges. The first approach investigates WM-only functional networks, treating WM parcels as independent nodes and analyzing their intrinsic functional interactions. These studies have demonstrated that WM possesses unique functional connectivity patterns, establishing stable networks that are comparable to those found in GM13. Moreover, alterations in WM functional connectivity have been identified in various neurological and psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia17 and nicotine dependence18. However, analyzing WM in isolation may obscure its broader contributions to the coordination of large-scale brain communication. To address this limitation, researchers have introduced a GM-WM network approach, which explicitly models the functional interactions between GM and WM nodes, each defined by distinct atlases14,19. This paradigm has revealed significant functional disruptions in psychiatric populations20,21, while also providing new insights into how WM contributes to the dynamics of GM networks22. Nevertheless, these networks remain structurally constrained, as they primarily capture GM-to-WM connections and lack closed-loop interactions23. This structural limitation complicates the application of conventional network analyses, such as assessments of global efficiency or modularity. Additionally, differences in signal amplitude and dynamic properties between WM-WM and GM-GM connections can lead to inconsistencies12 when analyzed within a unified framework, ultimately affecting the biological interpretation of network topology.

To overcome these challenges, a third approach—the unified functional connectome—has emerged, aiming to integrate both GM and WM connectivity into a cohesive framework that can capture closed-loop interactions and elucidate comprehensive mechanisms of network integration24,25,26. However, this area of research is still in its infancy, lacking a standardized modeling paradigm. Several promising methods have been put forth, each presenting unique advantages while grappling with methodological hurdles. For instance, Gao et al. introduced a projection-based mapping strategy that mathematically transforms GM-WM functional connections into an equivalent GM-only network, termed the “WM-mediated GM functional connectivity network.” By calculating its global efficiency, they discovered a negative correlation between network efficiency and age24 as well as a reduction in efficiency among individuals with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease27. This innovative approach partially addresses the absence of triangular pathways in bipartite GM-WM networks and highlights distinct topological properties. While this innovative approach enables the calculation of global properties like efficiency, the resulting network is directed and non-reciprocal (i.e., the connectivity from region A to B is not equal to that from B to A), which creates considerable interpretational ambiguity from both methodological and neurobiological standpoints. Another avenue of research has focused on the modulation of GM network organization by WM. Wang et al. developed an edge-centric network analysis approach that illustrates how WM signals significantly regulate GM functional organization, with evidence suggesting that this modulation is impaired in disease populations26. Although this elegantly quantifies WM’s modulatory influence, it does not produce an explicit, integrated connectome that can be subjected to further network analysis. More recently, Zu et al. proposed a three-way correlation model that treats WM BOLD signals as a third component within traditional GM functional networks, thereby providing a more comprehensive representation of WM’s mediation of GM interactions25. While this offers a rich depiction of the underlying architecture, its three-dimensional structure is incompatible with the vast majority of standard graph-theoretical toolboxes, which require a 2D adjacency matrix, and thus does not resolve the fundamental challenge of analyzing network topology in GM-WM systems; moreover, its mathematical complexity may pose a barrier to broader clinical application. As research in this area continues to evolve, the integration of GM and WM connectivity promises to enhance our understanding of the brain’s complex functional dynamics, ultimately paving the way for improved insights into neuropsychiatric conditions and their underlying mechanisms.

To address these distinct limitations, we propose the Gray-White Matter Heterogeneous Fusion Network (GWM-HFN). This framework constructs a unified and weighted GM-GM connectome by defining the functional connectivity between any two GM regions as the covariance of their respective interaction profiles with all WM bundles. This approach uniquely produces a symmetric, intuitive, and fully analyzable 2D network matrix that retains critical information about WM-mediated communication, thereby bridging the gap between descriptive models of WM influence and the practical need for a topologically coherent connectome. To validate our framework, our study rigorously examines the test-retest reliability and topological organization of the GWM-HFN. We juxtapose our findings against those derived from conventional GM-GM connectivity analyses, providing a comprehensive comparison that highlights the unique contributions of our model. Furthermore, we delve into the practical implications of GWM-HFN by investigating age-related changes in connectivity patterns, assessing its clinical relevance, and exploring its correlations with various cognitive and behavioral measures. Through these multifaceted analyses, we aspire to establish a robust and comprehensive framework that not only enhances our understanding of the brain’s functional architecture but also effectively bridges the existing divide between traditional GM-centric methodologies and the active, communicative role of white matter in inter-regional connectivity.

Results

General description of analytical methods, datasets and research questions

In this research, we presented GWM-HFN, a network framework aimed at merging functional data from two heterogeneous brain structures (GM and WM) by deliberately integrating WM signals into rs-fMRI connectivity evaluations. Figure 1 illustrates a schematic representation of this method. In summary, following preprocessing, time-series signals were gathered from 90 GM regions (Anatomical Automatic Labeling, AAL atlas; refer to Supplementary Table 1 for specifics) and 48 WM bundles (JHU-ICBM 48 atlas; refer to Supplementary Table 2 for specifics). Subsequently, we developed a bipartite GM-WM correlation matrix, where each row represents the functional connectivity profile of a GM region with various WM bundles. Considering that WM acts as the main pathway for long-distance communication between GM regions, we also calculated the covariance of GM-WM connectivity profiles, converting the bipartite matrix into a GM-centered representation that indirectly reflects WM-mediated interactions. The resulting GWM-HFN encapsulates the functional communication strength among GM regions, which is informed by the covariance of their interaction profiles with the brain’s WM bundles. This modification retains WM-derived functional information within a GM-aligned network framework, allowing for the exploration of both global and local network characteristics while incorporating the impact of WM functional connectivity profiles on brain activity.

A Development of the gray-white matter heterogeneous fusion network (GWM-HFN). This phase initiated with the extraction of gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) signals from preprocessed rs-fMRI datasets to create a GM-WM connectivity matrix B. Following this, the values were standardized row-wise to generate a Z-score matrix, highlighting the relative interaction profile of each region within its connectivity framework. Ultimately, the covariance matrix C, which was obtained from Z, functioned as a GM FC matrix mediated by WM, also referred to as the GWM-HFN. B Analysis of GWM-HFN Characteristics. The research evaluated the test-retest reliability of the GWM-HFN network alongside its topological characteristics using graph theoretical metrics. Additionally, comparative assessments between GWM-HFN and conventional GM-GM connectivity networks were carried out. C Utilization of GWM-HFN. The practical relevance of the GWM-HFN was investigated across three areas. First, examining its age-related trends, which included both linear and quadratic effects; second, evaluating its use in clinical settings; and third, applying partial least squares (PLS) regression to assess its predictive ability for cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Icon elements in this figure were sourced from iSlide (islide.cc) and Freepik.com.

We meticulously assessed GWM-HFN through various independent datasets to evaluate its dependability, network characteristics, and functional significance, which encompassed test-retest reliability (TRT), structural organization, comparisons to GM-GM connectivity, age-related variations, clinical significance, and cognitive/behavioral associations. In particular, the Southwest University Longitudinal Imaging Multimodal (SLIM) dataset (https://doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.retro.slim) was utilized to analyze network patterns, structural organization, and long-term reliability, while the Beijing Normal University (BNU-3) (https://doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.bnu3) offered measurements for short-term reliability. The Southwest University Adult Lifespan (SALD) dataset (https://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/retro/sald.html) was employed to examine age-related trajectories of GWM-HFN connectivity within a cross-sectional population. To investigate clinical relevance, we focused on disorder-specific changes in GWM-HFN using the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange II (ABIDE-II) project (https://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/abide/abide_II.html), with an emphasis on autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Lastly, the Brain Genomics Superstruct Project (BGSP) dataset (https://www.neuroinfo.org/gsp/) facilitated partial least squares (PLS) regression to connect GWM-HFN connectivity with cognitive and behavioral metrics. A comprehensive description of these datasets is available in the Supplementary information (the “Study Datasets” section), with Supplementary Table 3 providing a summary of essential demographic details.

To facilitate cross-network comparisons and interpretability, GM nodes were organized into seven functional networks. This was achieved by adapting the Yeo-7 cortical parcellation using a “winner-takes-all” mapping, followed by adjustments based on established anatomical and functional literature. Within this framework, key subcortical regions such as the hippocampus and amygdala were assigned to the Limbic Network (LN) based on established anatomical and functional literature28, while the caudate, putamen, pallidum, and thalamus were grouped into a distinct Basal Ganglia Network (BGN). The final seven networks include the Visual Network (VN), Sensorimotor Network (SMN), Attention Network (AN), LN, Frontoparietal Network (FPN), Default Mode Network (DMN), and BGN (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table 1). This categorization facilitated a more structured evaluation of GWM-HFN connectivity trends among functionally diverse systems. Additional information regarding node assignments and the relevant methods can be accessed in the Supplementary information (the “Mapping AAL Atlas to Macroscopic Networks” section).

Gray-White Matter heterogeneous fusion network patterns (SLIM Dataset)

For every one of the 572 younger healthy individuals (ages 17–27) from the SLIM dataset (baseline), we developed GWM-HFN and traditional GM-GM networks. Figure 2B illustrates the mean connectivity matrices at the group level for the constructed GWM-HFN and traditional GM-GM networks. Generally, the connectivity matrices revealed consistently higher intra-network connectivity among large-scale functional subnetworks (such as visual and frontal-parietal networks) and moderately strong inter-network connections, regardless of whether GWM-HFN or GM-GM was analyzed. A visual inspection of the group-average connectivity matrices suggests that the GWM-HFN framework captures connections—both within and between networks—that appear stronger in magnitude compared to those in the GM-GM framework. Rigorous statistical comparisons of network properties derived from these matrices are detailed in Section 2.5. This suggests a fundamental difference in the network topology captured by the two methods.

Multi-level test-retest reliability assessment (BNU-3 and SLIM Datasets)

The BNU-3 dataset was used to assess short-term TRT reliability, with each participant undergoing three scanning sessions within a single day. In contrast, the SLIM dataset was employed to evaluate long-term TRT reliability. Participants in this dataset underwent up to three scanning sessions, although only a subset completed the second and third sessions. For the purposes of this study, only the first two time points—separated by an average interval of 304.14 days—were used to assess long-term TRT reliability. To provide a comprehensive evaluation and a direct comparison with conventional methods, we assessed reliability using three distinct approaches: (i) pattern similarity via Pearson correlation, (ii) conventional edge-wise reliability via the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), and (iii) a more advanced connectome-level identifiability framework.

Pattern similarity using pearson correlation

As illustrated in Fig. 3A, B, the GWM-HFN exhibited stable and consistent connectivity patterns across time points at the group level in both datasets. Group-averaged connectivity networks showed strong correlations across sessions, with a mean Pearson correlation of r = 0.955 for short-term reliability (BNU-3) and r = 0.897 for long-term reliability (SLIM). However, this high group-level consistency masks considerable variance at the individual level, where correlations were more modest. In the SLIM dataset, the average individual-level correlation was 0.37 (±0.13), as shown in the lower-right corner of Fig. 3A. Similarity, the BNU-3 dataset, the average correlation across time points was approximately 0.53 (\({r}_{{\mathrm{1,2}}}=0.57{{;r}}_{{\mathrm{1,3}}}=0.52{{;r}}_{{\mathrm{2,3}}}=0.50\)), as shown in the lower-right corner of Fig. 3B. This discrepancy highlights the necessity of individual-level reliability analyses, as high group-level stability does not guarantee that individual-specific connectivity patterns are reliably captured.

A, B Group-level pattern stability versus individual-level similarity for the GWM-HFN. The main scatterplots show the high correlation between group-averaged GWM-HFN connectivity strengths across two sessions for the long-term (A, SLIM dataset) and short-term (B, BNU-3 dataset). The red line indicates the identity line (y = x), and dot color indicates the density of overlapping points. The inset raincloud plot in each panel illustrates the more modest distribution of Pearson correlation coefficients calculated at the individual subject level. C, D Edge-wise Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) matrices. Heatmaps display the ICC value for every connection for both the GWM-HFN (left) and the conventional GM-GM (right) network. Results are shown for the long-term (C, SLIM dataset) and short-term (D, BNU-3 dataset) reliability assessments, with brighter colors indicating higher reliability. E Direct comparison of edge-wise ICC values between methods. Scatterplots compare the ICC of each edge from the GWM-HFN (y-axis) against the GM-GM network (x-axis) for the SLIM (left) and BNU-3 (right) datasets. The dashed black line is the identity line, and the red line is the linear fit. The inset violin plots provide a summary comparison of the ICC distributions, confirming the significantly higher mean ICC for the GM-GM method in both datasets. F Connectome-level assessment using the identifiability framework. Box plots compare the GWM-HFN and GM-GM networks on three key metrics: mean intra-individual similarity (Reliability, µintra), mean inter-individual similarity (Uniformity, µinter), and the summary Identifiability Score. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (paired t-tests for Reliability and Uniformity; bootstrap test for Identifiability). n = 237 biologically independent participants for the SLIM test-retest dataset and n = 46 biologically independent participants for the BNU-3 dataset.

Edge-wise Reliability using Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC)

We quantified the TRT reliability of individual connections using the ICC. To benchmark our method, we compared the edge-wise ICC of GWM-HFN with that of the conventional GM-GM network (Fig. 3C, D). First, we observed a significant positive correlation between the edge-wise ICC values from the two methods across both datasets (see Fig. 3E), suggesting a shared spatial pattern of reliability. Following this, as shown in Fig. 3E, the GM-GM network exhibited a significantly higher mean edge-wise ICC in both short-term (GM-GM: 0.44 ± 0.11; GWM-HFN: 0.36 ± 0.12; t(4004) = 57.52, p < 2.2 × 10-16) and long-term datasets (GM-GM: 0.24 ± 0.08; GWM-HFN: 0.20 ± 0.08; t(4004) = 42.19, p < 2.2 × 10-16). These results indicate that conventional GM-GM connectivity is more stable at the single-edge level, likely reflecting its sensitivity to strong, generic signals from primary sensory-motor regions that are highly consistent within and across individuals. Notably, and consistent with previous observations, long-term reliability was generally lower than short-term reliability, likely due to increased variability introduced by longer intervals between measurements (e.g., physiological changes and day-to-day fluctuations)29,30.

Connectome-level assessment using the identifiability framework

To provide a more comprehensive assessment of individual-level stability and uniqueness, as suggested by recent literature31, we implemented an identifiability framework, which evaluates a connectome’s stability (Reliability, µintra), its distinctiveness from others (Uniformity, µinter), and its overall utility for individual identification (Identifiability). This analysis revealed a critical trade-off between stability and individual specificity (Fig. 3F).

Consistent with the ICC results, the GM-GM network showed higher Reliability (mean intra-individual similarity) in both long-term (GM-GM: 0.64 vs. GWM-HFN: 0.40; t(571) = 44.26, p < 2.2 × 10-16) and short-term datasets (GM-GM: 0.71 vs. GWM-HFN: 0.53; t(45) = 21.86, p < 2.2 × 10−16). However, the GWM-HFN demonstrated a striking advantage in Uniformity, exhibiting significantly lower mean inter-individual similarity (µinter) in both long-term (GM-GM: 0.54 vs. GWM-HFN: 0.30; t(571) = 490.77, p < 2.2 × 10−16) and short-term datasets (GM-GM: 0.55 vs. GWM-HFN: 0.34; t(45) = 129.74, p < 2.2 × 10−16). This indicates that while GM-GM networks are more stable on average, GWM-HFN networks are more sensitive to the unique connectivity patterns that differentiate one individual from another. Finally, we computed the overall Identifiability scores for both methods. The GM-GM network yielded significantly higher identifiability scores in both the long-term (GM-GM: 1.59 vs. GWM-HFN: 1.12; p = 0, bootstrap test) or short-term datasets (GM-GM: 2.30 vs. GWM-HFN: 1.86; p = 0, bootstrap test). This indicates that the greater stability (µintra) of the GM-GM network provides it with an advantage in this specific composite metric. Taken together, these results reveal a nuanced reliability profile, which will be interpreted in the Discussion.

Topological Organization of the GWM-HFN (SLIM dataset)

For the GWM-HFNs derived from the 572 younger healthy participants from the SLIM time1 dataset, we calculated a set of graph-based network measures across varying sparsity thresholds (0.10–0.34, step = 0.01) to study their topological organization, including small-world organization, modularity architecture, degree distribution, and hubs.

Small-world properties and modularity

The GWM-HFN consistently demonstrated characteristics indicative of a classic small-world network configuration. This was evidenced by normalized clustering coefficients exceeding 1, alongside characteristic path lengths approximating 1, as illustrated in Fig. 4A. Such properties suggest a network topology that facilitates efficient information transfer and integration among disparate brain regions. Moreover, the modularity coefficient (Q) consistently remained above 0.3 across a wide threshold range (Fig. 4B), suggesting that explicit WM inclusion produces well-segregated community structures that may capture local clustering mechanisms.

A Small-world properties—sigma (σ), normalized clustering coefficient (γ), and normalized characteristic path length (λ)—of the GWM-HFN across a range of sparsity thresholds, presented as mean ± standard deviation. B Modularity coefficient (Q) of the GWM-HFN across varying sparsity thresholds, also shown as mean ± standard deviation, indicating robust modular organization. C Degree distribution of the group-averaged GWM-HFN, best fitted by an exponentially truncated power-law model, revealing the existence of highly connected brain regions. D Identification of 14 hub nodes within the group-averaged GWM-HFN, highlighting their central roles in the brain’s functional connectivity architecture. E Hub nodes identified in the benchmark group-averaged GM-GM network, allowing for a direct comparison of the central network architecture revealed by each framework. n = 572 biologically independent participants (SLIM dataset).

Hub distribution and degree

The degree distribution observed in the group-level mean GWM-HFN was best represented by an exponentially truncated power law model, achieving a high goodness-of-fit (R² = 0.959), as shown in Fig. 4C. This particular form of degree distribution is indicative of the presence of highly connected regions, commonly referred to as hubs, within the GWM-HFN. To identify central regions, we defined hubs as the top 15% of nodes with the highest degree32,33. This data-driven approach identified 14 hub nodes. The specific anatomical locations and network affiliations of these 14 hubs are detailed in Supplementary Table 4 and visualized in Fig. 4D. These hubs are predominantly located in higher-order association cortices and primary sensory areas, including key regions within the default mode, visual, and limbic networks.

Comparison with traditional GM-GM Networks (SLIM Dataset)

Similarity assessment

To evaluate the added value of incorporating white matter in connectivity modeling, we compared the GWM-HFN with traditional GM-GM networks at the edge, network, and global levels using the SLIM dataset. At the edge level, the two network types exhibited strong similarity, with an average Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.77 (±0.038). As shown in Fig. 5FA, a representative participant’s data revealed a high correlation between GWM-HFN and GM-GM connection strengths (r = 0.743, p < 2.2 × 10−16). Nevertheless, this suggests that more than 40% of the variance remains unique to each network type. To better understand these differences, we identified the 5% of edges with the highest and lowest correlations between the two networks, illustrated in Fig. 5B, C. Edges with low correlations were primarily intra-network connections within specific functional systems such as the VN, FPN, and DMN. In contrast, highly correlated edges were predominantly inter-network connections, especially between the BGN and other systems like the VN, SMN, LB, and DMN. This trend was consistent at the network level: inter-network correlations across large-scale functional networks were stronger (mean r = 0.84) than intra-network correlations (mean r = 0.79), as depicted in Fig. 5D. At the global level, GWM-HFN and GM-GM connectivity profiles showed robust consistency across participants, with a global correlation coefficient of 0.857 (p < 2.2 × 10−16). Thus, these findings collectively reveal a critical pattern: while the two methods agree on broad, inter-system communication, the key contribution of GWM-HFN lies in uncovering a more divergent topological structure within functional systems, providing complementary insights into white matter-mediated integration.

A Scatterplot illustrating the relationship between GWM-HFN and GM-GM connection strengths for a representative participant, showing a high correlation (r = 0.743). B, C Heatmaps highlighting edges with the lowest (<5th percentile) and highest (>95th percentile) correlations between the two network types, respectively. D Network-level correlation analysis revealing stronger inter-network correlations (mean r = 0.84) than intra-network correlations (mean r = 0.79) between GWM-HFN and GM-GM connectivity. E Violin plots comparing the magnitude of “true” inter-subject variability between the two frameworks after correcting for intra-subject measurement noise (N). No significant difference was found (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.73). F Scatter plot illustrating the moderate correlation of node-wise “true” inter-subject variability between the GWM-HFN (y-axis) and GM-GM (x-axis) frameworks across 90 brain regions. The dashed line represents identity (y = x), and the solid red line is the linear regression fit. G Lateral views of the top 20% (18 out of 90) nodes with the highest “true” inter-subject variability for the GWM-HFN framework (top row) and the GM-GM framework (bottom row). The minimal overlap (Jaccard index = 0.125) highlights the distinct spatial topographies of variability captured by each method. H Line plot of average Jaccard coefficients across sparsity thresholds (0.01–0.50), with shaded regions representing standard deviation, demonstrating consistency across thresholds. I Box plots comparing the area under the curve (AUC) for global topological properties—including clustering coefficient, assortativity, characteristic path length, global efficiency, and small-worldness—across the 0.10–0.34 sparsity range, indicating significant differences between GWM-HFN and GM-GM networks. n = 572 biologically independent participants (SLIM dataset).

Variability assessment

To compare the inter-individual variability captured by each framework while accounting for potential differences in signal quality, we applied variance decomposition method proposed by the Mueller et al. using our test-retest SLIM dataset34. This approach models the observed between-subject variability (Y) as a function of the intra-subject (session-to-session) variability (N), thereby allowing us to derive a residual measure of inter-subject variability that has been statistically corrected for measurement noise.

The analysis revealed that while the raw between-subject variability was initially higher in the GWM-HFN framework (mean Y = 0.711) than in the GM-GM framework (mean Y = 0.454), this was largely explained by a correspondingly higher level of intra-subject variability (i.e., noise; mean N = 0.631 vs. 0.368). After rigorously correcting for this intra-subject variability, the remaining “true” inter-subject variability was not significantly different in magnitude between the two frameworks (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.73, Fig. 5E).

Despite this comparable overall magnitude, the spatial topographies of this true variability were largely distinct. The node-wise variability maps were only moderately correlated (r = 0.479, 95% CI [0.302, 0.624], p = 1.80 × 10⁻⁶, Fig. 5F), and the overlap between the top 20% most variable nodes was minimal (4 of 18 nodes; Jaccard index = 0.125, Fig. 5G). Neuroanatomically, GWM-HFN’s high-variability nodes were concentrated in the DMN and SMN networks. In contrast, the GM-GM framework’s variability was highest in higher-order association systems, including the AN and FPN.

Network organization assessment

To evaluate the organizational similarity between GWM-HFN and GM-GM networks, we computed Jaccard coefficients across a range of sparsity thresholds (0.01–0.50). The average coefficients ranged from 0.39 to 0.66, with values increasing at higher sparsity levels (Fig. 5H), indicating greater structural alignment at higher network densities. At lower sparsity thresholds, notable discrepancies emerged, reflecting amplified structural differences between the two network types. This pattern was further nuanced across functional modules (Supplementary Fig. 1). Specifically, inter-network connections demonstrated lower baseline similarity, which progressively increased with sparsity, while intra-network connections showed higher baseline similarity but followed a U-shaped trajectory, reaching a minimum around 0.05 sparsity. These results suggest that WM-mediated interactions introduce distinct network architectural features, particularly in sparse functional networks, emphasizing the complementary contributions of GWM-HFN connectivity to traditional gray matter-based analyses.

To more comprehensively assess topological differences, we performed a graph-theoretical analysis using area under the curve (AUC) metrics calculated from the 0.10–0.34 sparsity range, with statistical comparisons based on paired t-tests. Results revealed that GWM-HFN networks are topologically distinct, exhibiting enhanced modular segregation but reduced global integration compared to GM-GM networks. GWM-HFN networks showed significantly higher Clustering Coefficient (Cp) and Assortativity, reflecting increased local cohesiveness and node-type homogeneity (Fig. 5I). Specifically, after correcting for multiple comparisons, Nodal Clustering Coefficient and Subgraph Centrality in the GWM-HFN framework were significantly higher across a majority of brain areas. We found that 60 of 90 nodes for Clustering Coefficient and 76 of 90 nodes for Subgraph Centrality showed significantly greater values (paired t-test, PFDR < 0.001), with detailed node-wise results presented in Supplementary Fig. 2. Lower Participant Coefficient in GWM-HFN networks suggested stronger modular boundaries, implying that white matter-informed connectivity preserves distinct community structures more rigidly (Supplementary Fig. 2). In contrast, GWM-HFN networks demonstrated significantly longer Characteristic Path Lengths (Lp) and lower Global Efficiency (Eglob), consistent with reduced capacity for rapid and efficient global information transfer (Fig. 5I). This was associated with reduced Small-Worldness (Sigma), reflecting a diminished balance between segregation and integration. While Betweenness Centrality was significantly elevated in many GWM-HFN nodes, indicating increased control over information flow, other metrics—including Degree, Eigenvector Centrality, PageRank Centrality, and Nodal Efficiency—exhibited bidirectional changes across brain regions, suggesting a complex reorganization of functional hubs and peripheral nodes (Supplementary Fig. 2). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that GWM-HFN networks encode a distinct functional topology, marked by heightened modularity and segregation but less efficient global integration, suggesting a functional architecture that prioritizes specialized, modular processing over efficient global integration.

To directly compare the central network architectures, we applied the identical hub identification procedure (top 15% degree) to the conventional GM-GM networks (Fig. 4E). As detailed in Supplementary Table 4, this comparison revealed a substantial overlap, with 11 hubs being common to both methods (Dice coefficient = 0.786). These common hubs, including key regions in the bilateral middle temporal gyrus and lingual gyrus, form a robust core set of highly connected nodes identifiable by both approaches. Critically, the analysis also revealed method-specific hubs. The GWM-HFN uniquely identified three hubs in higher-order association areas: the right inferior frontal orbital gyrus (ORBinf.R), the left superior temporal gyrus (STG.L), and the right superior temporal pole (TPOsup.R). Conversely, the conventional GM-GM method uniquely identified three hubs located primarily in primary sensory and attention networks: the right superior frontal gyrus (SFGdor.R), the left calcarine cortex (CAL.L), and the right fusiform gyrus (FFG.R). In summary, this direct comparison demonstrates that while both frameworks identify a core set of shared hubs, they also reveal distinct topological priorities, with GWM-HFN highlighting unique hubs in higher-order association cortices and the conventional method in sensory and attention networks.

Age-related patterns in GWM-HFN (SALD datasets)

Using the SALD datasets, which include a broad adult age range from 19 to 80 years, we examined how GWM-HFN connectivity evolves across the adult lifespan. To comprehensively evaluate the unique characteristics of GWM-HFN, we benchmarked our findings against a parallel analysis of traditional GM-GM functional connectivity. Linear and quadratic regression models were applied to assess the relationship between age and connectivity strength, with head motion and sex controlled as covariates. At the global level, GWM-HFN connectivity showed a significant negative linear association with age (r = −0.252, p = 1.0 × 10-07; Fig. 6A), while the quadratic term was not statistically significant (p = 0.296), indicating a predominantly linear age-related decline. In contrast, the benchmark GM-GM analysis revealed a significant inverted U-shaped quadratic relationship with age at the global level (βqud = −0.017, p = 0.030; Fig. 6D), with peak age of 37.2 years.

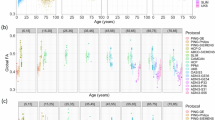

A, D Scatter plot illustrating the negative linear correlation between mean GWM-HFN connectivity and age (r = -0.252, p = 1.0 × 10⁻07), while (D) shows the contrasting inverted U-shaped quadratic relationship for the benchmark GM-GM network. In both plots, each dot represents an individual, and its color indicates the density of overlapping data points. The red line depicts the fitted linear regression, and the shaded region represents the 95% confidence interval of the linear fit. B, E Circular connectograms depicting edge-level age effects for GWM-HFN and GM-GM networks, respectively. For each, the left panel shows linear effects (blue: negative, red: positive), and the right panel shows quadratic effects (green: inverted U-shaped, purple: U-shaped), with line thickness representing effect magnitude. Brain regions are color-coded according to their associated functional networks. C Clustered bar chart showing the proportion of significant age-related edges for the GWM-HFN framework, distributed across the seven functional networks and separated into within-network and between-network connections. F Heatmap illustrating the overlap of significant age-sensitive edges between the two frameworks. Red indicates edges significant in both methods (overlap), yellow indicates edges specific to GWM-HFN, and green indicates edges specific to GM-GM. G Scatterplots showing the significant positive correlation between the effect sizes (t-values) of overlapping age-sensitive edges for negative linear effects (left panel) and inverted U-shaped quadratic effects (right panel). H Scatter plot showing the positive correlation between age and the similarity of GWM-HFN and GM-GM connectivity patterns (r = 0.311, p = 3.0 × 10⁻11), indicating greater convergence between the two methods in older individuals. n = 440 biologically independent participants (SALD dataset).

At the edge level, our GWM-HFN framework identified that over half of all connections (2044 out of 4005; 51.04%) were significantly modulated by age after FDR correction \(({P}_{{\mathrm{FDR}}} < 0.05)\). Notably, 78.47% of these age-sensitive edges (1604 connections) exhibited negative linear associations, suggesting widespread weakening of GWM-HFN connectivity with aging. A smaller proportion (1.96%, 40 edges) showed positive linear trends, indicating a limited set of connections that strengthen over time (Fig. 6B, left panel). In addition to linear effects, quadratic age-related patterns were identified in 400 edges (19.57%). Of these, 96% (384 edges) followed inverted U-shaped trajectories, peaking before declining, whereas 4% (16 edges) followed U-shaped curves with initial decline followed by later-life increases (Fig. 6B, right panel). The average peak age for connections with significant quadratic effects was 33.84 years, suggesting a critical window of maximal GWM-HFN in early adulthood. At the large-scale functional network level, we further investigated whether age-related effects preferentially targeted connections within or between functional networks by comparing the proportions of affected edges in each category. Overall, we observed that a substantial proportion of both within-network (55.4%) and between-network (51.5%) connections were significantly modulated by age, indicating a widespread impact. However, the analysis revealed network-specific patterns. For instance, the SMN and LB showed a higher proportion of affected within-network connections (62.6% and 61.7%, respectively) compared to their between-network counterparts (49.6% and 61.1%). Conversely, the AN exhibited a greater proportion of affected between-network connections (50.4%) relative to its within-network connections (42.2%). These findings, detailed in Fig. 6C, suggest a heterogeneous pattern of age-related changes across the connectome rather than a uniform targeting of between-network links.

The benchmark GM-GM analysis, in turn, identified 1550 connections with significant age-related effects (\({P}_{{\mathrm{FDR}}} < 0.05\)), as illustrated in Fig. 6E. Of these, 656 edges showed a linear relationship (499 negative, 157 positive), while a larger proportion (894 edges) followed a quadratic trajectory (889 inverted U-shaped, 5 U-shaped), with an average peak age of 38.44 years. A direct comparison of the age-sensitive edges identified by both methods revealed a substantial overlap of 938 connections (Jaccard index = 0.3532; Fig. 6F). Within this overlap, consistency was high: 412 edges were linear (with 411, or 99.8%, showing the same direction of association) and 287 were quadratic (all sharing the same shape). Furthermore, the effect sizes of these common connections were significantly correlated between the two frameworks for both negative linear (r = 0.553, p = 1.1 × 10-33) and inverted U-shaped effects (r = 0.467, p = 7.2 × 10-17; Fig. 6G). When categorizing effects more broadly into declining (negative linear, inverted-U) versus inclining (positive linear, U-shape) patterns, we found that 921 of the 938 overlapping edges (98.2%) showed this general consistency, indicating that when both frameworks detect an age-related change, they are often capturing a shared underlying biological process.

Finally, beyond the specific overlap in age-sensitive edges, we examined the overall similarity between the two connectome types across all subjects. We observed a high correlation between GWM-HFN and traditional GM-GM connectivity across subjects (mean r = 0.735), which intensified with increasing age (r = 0.311, p = 3.0 × 10−11; Fig. 6H). This finding suggests that the convergence between GWM-HFN and gray matter-based functional networks becomes more pronounced in older individuals.

Clinical relevance: insights from patient cohorts

To test the clinical utility of the GWM-HFN framework, ASD was selected as the primary clinical exemplar for this study. This choice was motivated by several key theoretical and empirical considerations. First, ASD has long been conceptualized as a disorder of atypical brain connectivity, or a ‘disconnection syndrome,’ with numerous studies reporting altered functional connectivity patterns during tasks related to complex cognitive and social processing35. Second, there is extensive and well-documented evidence from neuroimaging studies demonstrating widespread alterations in white matter microstructure in individuals with ASD36,37. These established structural abnormalities provide a strong a priori basis for hypothesizing that WM-mediated functional connectivity, as captured by GWM-HFN, would also be affected. Finally, the publicly available ABIDE-II project offers a large-scale, multi-site dataset with rich clinical phenotyping, providing the necessary statistical power for a robust validation of our method and for exploring crucial brain-behavior relationships. To assess these potential alterations, we constructed networks for individuals with ASD and TC individuals using the ABIDE-II dataset, a large-scale, multi-site repository that integrates neuroimaging data from diverse international cohorts.

Prior to analysis, we applied the ComBat method for harmonization to minimize the impact of sites38. While a visual inspection of the distributions before and after harmonization suggests a reduction in site-related variance (Fig. 7A), we performed a rigorous quantitative analysis to confirm the complete removal of site effects. Before harmonization, a Type III ANOVA revealed a highly significant site effect on global mean connectivity (F(12, 623) = 9.65, p < 2.2 × 10−16). At the edge-level, 93.8% of all connections showed a significant site effect (\({P}_{{\mathrm{FDR}}} < 0.05\)), with a median effect size (partial η2) of 0.086. After ComBat harmonization, the site effect was no longer significant at the global level (F(12, 623) = 0.67, p = 0.783). Critically, at the edge level, the proportion of connections with a significant site effect dropped to 0, and the median partial η2 was reduced to 0.002. These quantitative results confirm that the ComBat procedure effectively and comprehensively removed site-specific biases from our data.

A Boxplot illustrating the global mean GWM-HFN connectivity across 13 acquisition sites before and after harmonization. The red diamond indicates the mean connectivity within each site, while the gray line represents the overall mean connectivity across all sites. B Raincloud plot comparing the global-averaged GWM-HFN and GM-GM connectivity strengths between the ASD and TC groups. C Left panel: Brain network depicting the significantly different GWM-HFN connections identified between the ASD and TC groups, with all significant connections showing greater connectivity in the ASD group (ASD > TC), indicated by red. Right panel: Brain network illustrating the significantly different GM-GM connections identified between the ASD and TC groups, with the majority of connections exhibiting greater connectivity in the ASD group (ASD > TC), indicated by red. Connections showing decreased connectivity in the ASD group (ASD < TC) are indicated by blue. Line thickness corresponds to the magnitude of the effect size. D Scatterplot comparing the p-values of group differences for GWM-HFN and GM-GM functional connections. The two red dashed lines indicate the threshold for significance after FDR correction (\({P}_{{\mathrm{FDR}}} < 0.05\)). Data points are color-coded based on the significance of the connection: light yellow for connections significant in both the GWM-HFN and GM-GM analyses, light red for connections significant only in the GWM-HFN analysis, and light blue for connections significant only in the GM-GM analysis. E Brain connectivity map visualizing connections that were significant only in the GWM-HFN analysis, significant only in the GM-GM analysis, and significant in both analyses. F Bar plots quantifying the distribution of significant edges from the ASD versus TC group comparison, comparing the number of altered within-network and between-network connections for both the GWM-HFN and GM-GM frameworks. G Scatterplot showing the significant negative Pearson correlation between the mean connectivity strength of the altered edges and the ADOS-G total scores for both the GWM-HFN and GM-GM frameworks. The red line depicts the fitted linear regression, and the shaded region represents the 95% confidence interval of the linear fit. n = 368 TC and n = 272 ASD biologically independent participants.

We first conducted group comparisons, controlling for age, sex, and mean FD as covariates. Results revealed that individuals with ASD exhibited significantly stronger global mean GWM-HFN connectivity compared to TC (\(t=2.020,p=0.044\)). In contrast, no significant differences were observed in mean GM-GM connectivity between the groups, as illustrated in Fig. 7B. At the edge level, 310 GWM-HFN connections showed significant group differences, all indicating increased connectivity in the ASD group (Fig. 7C). In comparison, the GM-GM connectivity network revealed only 106 significant edges, of which 102 also showed stronger connectivity in ASD. Remarkably, about 80% (83 out of 106) of these significant GM-GM connections overlapped with the GWM-HFN connections (Fig. 7D, E), underscoring both the heightened sensitivity and the convergent validity of GWM-HFN in detecting ASD-related alterations. To confirm that these findings were not solely driven by the younger participants in this wide age-range cohort, we performed a validation analysis on a subsample of adolescents and adults (age ≥ 16). The spatial pattern of edge-wise group differences in this older subsample was highly correlated with that of the full sample (r = 0.719, p < 2.2 × 10-16; see Supplementary Fig. 3), and over half of the significant edges from the full analysis were replicated despite the reduced statistical power. This confirms that the observed hyperconnectivity pattern is a stable feature across adolescence and adulthood.

Subsequently, we compared the proportions of significant connections to provide an unbiased assessment of within- versus between-network effects. This analysis revealed that ASD-related abnormalities were not predominantly between-network, but were instead highly concentrated within specific functional systems. This pattern was most pronounced in the BGN, where the proportion of affected intra-network connections was dramatically higher than between-network connections for both GWM-HFN (60.7% vs. 31.1%) and GM-GM networks (46.4% vs. 12.3%). These findings indicate that ASD-related hyperconnectivity is primarily characterized by a disruption of intra-network integrity, particularly within the basal ganglia—an effect to which the GWM-HFN framework showed heightened sensitivity (Fig. 7F).

Finally, we investigated whether the identified significant connections were associated with the severity of autistic symptoms, as measured by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic (ADOS-G). Specifically, we calculated the correlation between the total ADOS-G score (ADOS_G_TOTAL) and the mean connectivity strength of the identified GWM-HFN and GM-GM connections. This association was significant for the GWM-HFN framework (r = −0.154, p = 0.042) and was notably more robust for the conventional GM-GM network (r = −0.255, p = 72 × 10-06), as illustrated in Fig. 7G.

GWM-HFN correlations with cognitive and behavioral measures

The BGSP dataset included a broad array of behavioral and cognitive measures, enabling exploration of phenotypic correlates of GWM-HFN connectivity. To investigate these associations, we employed PLS regression to evaluate whether GWM-HFN connectivity could explain interindividual differences in four cognitive-behavioral phenotypes: Shipley vocabulary score, matrix reasoning scores, and estimated IQ derived from both Shipley-Hartford T-scores and the OPIE3 formula. A parallel PLS analysis was conducted using the conventional GM-GM networks as a direct baseline comparison.

Our analysis focused on the first PLS component (PLS1), which represents the linear combination of GWM-HFN connectivity features most strongly associated with the behavioral data. Using permutation testing with 10,000 permutations, we found that PLS1 scores explained a significant proportion of variance in both the Shipley-Hartford estimated IQ (\(9.09 \% ,{P}_{{\mathrm{permutation}}}=0.0186\), Fig. 8A) and the Shipley vocabulary task (\(8.95 \% ,{P}_{{\mathrm{permutation}}}=0.0229\), Fig. 8B). For the benchmark GM-GM analysis, PLS1 scores showed a significant association only with the Shipley vocabulary task (\(13.05 \% ,{P}_{{\mathrm{permutation}}}=0.0060\), Fig. 8C). No significant associations were found for the matrix reasoning score or IQ estimated using the OPIE3 formula for either framework. Notably, the GWM-HFN was unique in identifying a significant link to the Shipley-Hartford estimated IQ, an association that was not detected by the conventional GM-only analysis.

A–C Scatterplots illustrating the significant correlations between PLS1 scores and cognitive measures. A Correlation between GWM-HFN PLS1 scores and the estimated IQ derived from Shipley-Hartford Age-Corrected T-Scores. B Correlation between GWM-HFN PLS1 scores and the Shipley vocabulary task scores. C Correlation between the benchmark GM-GM PLS1 scores and the Shipley vocabulary task scores. The color of the data points in the scatterplots indicates the density of overlapping points, with warmer colors representing higher density. D–F Brain visualizations of the stable, high-weight connectivity patterns driving the significant PLS associations shown in A–C, respectively. Edges displayed are those with absolute standardized PLS1 weights exceeding 3σ and confirmed to be stable via bootstrap analysis. G Density plots of 10,000 permutation tests for the correlation coefficient (r) between connectome data and Shipley vocabulary task scores using the BBS modeling method. The results demonstrate significant individual-level prediction for both the GWM-HFN (left panel) and GM-GM (right panel) frameworks. Circos plots visualizing the key connectivity patterns with the highest contributions ( | z | > 3σ) to the significant BBS predictions for the GWM-HFN (H) and GM-GM (I) vocabulary models. Positive weights are shown in red, and negative weights are in blue. n = 1564 biologically independent participants from the BGSP dataset.

To identify the most robust connectivity patterns driving these effects, we examined the standardized PLS1 weights and assessed the stability of all edge weights using a bootstrap analysis. For subsequent interpretation and visualization, we focused on high-weight connections (absolute standardized weight ( | z | > 3σ) that were also confirmed to be highly stable (Bootstrap Ratio |BSR | > 2). For the GWM-HFN framework, the stable, high-weight connectivity patterns underlying both the Shipley vocabulary and the Shipley-Hartford estimated IQ associations were remarkably consistent (Fig. 8D, E). They were characterized by predominantly negative weights within the DMN and positive weights between the DMN and the VN, with a high overlap between the contributing edges for both measures (Jaccard index = 0.62). Intriguingly, the benchmark GM-GM network’s significant association with vocabulary was driven by the same neurobiological pattern—negative intra-DMN and positive DMN-VN connectivity (Fig. 8F). A direct comparison revealed that half (5/10) of the high-weight edges from this GM-GM analysis were also identified by the GWM-HFN for the vocabulary task, indicating a shared substrate captured by both methods.

To further validate these associations, we applied the brain bias set (BBS) modeling method39 to predict individual scores in the cognitive domains identified as significant in the PLS analysis. Briefly, this approach uses principal component analysis to reduce the dimensionality of the connectivity data before fitting a linear regression model within a cross-validation framework. Results showed that GWM-HFN connectivity significantly predicted individual scores in the Shipley vocabulary task (\({\mbox{mean}}r=0.0785,{P}_{{\mathrm{permutation}}}=0.0327\), Fig. 8G), while no significant prediction was found for IQ estimated using the Shipley-Hartford T-scores. The benchmark GM-GM network also significantly predicted vocabulary scores (\({\mbox{mean}}r=0.124,{P}_{{\mathrm{permutation}}}=0.0017\)). Finally, we visualized the connectivity patterns with the highest contributions ( | z | > 3σ) to these significant predictions for the GWM-HFN and GM-GM frameworks, as depicted in Fig. 8H, I, respectively.

Discussion

This study introduces and rigorously validates the GWM-HFN, a framework that reliably integrates WM BOLD signals into functional connectome analysis. Our multi-dataset validation demonstrates GWM-HFN’s robust test-retest reliability, distinct topological features, and relevance in capturing age-related and clinical alterations. Such comprehensive characterization across reliability, topology, and diverse applications addresses a critical need in the evolving field of unified GM-WM functional connectomics, where extensive validation of emerging models24,25 is still developing. By providing a validated means to incorporate WM’s functional contributions, GWM-HFN directly challenges the traditional GM-centric view in neuroimaging2,7. Specifically, its GM-centered representation, derived from GM-WM covariance, overcomes limitations of WM-only approaches13,17 and bipartite GM-WM models that hinder conventional global network analyses due to absent closed-loop interactions24. GWM-HFN therefore offers a more holistic and interpretable model of whole-brain functional architecture, significantly advancing our capacity to map complex neural communication.

A cornerstone of establishing the GWM-HFN framework’s utility lies in its methodological viability, particularly its test-retest reliability. Our analyses yielded mean edge-wise ICCs of approximately 0.36 for short-term (BNU-3 dataset) and 0.20 for long-term (SLIM dataset) GWM-HFN connectivity. According to benchmarks such as those proposed by Landis and Koch40, these ICCs position GWM-HFN reliability in the ‘fair’ (ICC = 0.21–0.40) and ‘slight’ to ‘fair’ (ICC ≈ 0.20) categories, respectively. These values must be interpreted within the challenging context of rs-fMRI research, where achieving high test-retest stability for any individual FC measure is non-trivial due to inherent physiological noise, ongoing unconstrained cognitive processes, and cross-study analytical variability29,30.

Our comprehensive validation now provides crucial context for these values through a direct comparison with conventional GM-GM networks. We found that the ICCs for GWM-HFN, while within the spectrum reported for many GM-based connectivities29, are significantly lower than those of the GM-GM network. To understand the implications of this finding, we adopted a more comprehensive assessment framework31 which revealed a critical trade-off between raw stability and individual specificity. While the GM-GM network demonstrated higher raw stability (i.e., higher ICC and Reliability, µintra), our GWM-HFN framework showed a marked advantage in its ability to capture individual uniqueness. This was evidenced by its significantly lower Uniformity (µinter), indicating that GWM-HFN connectomes are more distinct from one another across the population. Although the superior stability of the GM-GM network resulted in a significantly higher overall Identifiability score, this finding highlights a critical neurobiological trade-off.

We propose that the superior stability of GM-GM networks is largely driven by strong, generic signals from primary sensory-motor regions that are highly consistent both within and across individuals. In contrast, GWM-HFN, by design, leverages the covariance of interaction profiles with all WM bundles, a method that is more sensitive to the subtle and variable—yet more individually-specific—connectivity patterns of higher-order association networks. The assessment of reliability in methodologies incorporating WM signals is an area of active development. For instance, Wang et al. investigated the robustness and reliability of direct WM functional connectivity41, finding that while static FC in GM networks was stronger than in WM networks, WM networks exhibited greater dynamism. The GWM-HFN approach, by deriving connectivity from shared WM bundles utilization, possesses distinct reliability characteristics. Our findings suggest that its strength lies not in maximizing raw signal stability, but in its enhanced sensitivity to the trait-like, neurobiological variations that differentiate individuals.

Furthermore, the pursuit of enhanced reliability underscores the critical importance of standardized preprocessing pipelines, as highlighted by the development of specialized toolboxes like WhiFuN11. Therefore, the reliability profile demonstrated by GWM-HFN is a crucial validation. It establishes that our framework, while exhibiting lower raw stability than GM-GM networks, successfully captures a rich source of individual-specific variance. This superior ability to characterize individual differences provides a necessary foundation for employing GWM-HFN in longitudinal studies and for investigating its potential in biomarker development, where tracking unique individual features is paramount10,14,15.

The GWM-HFN framework not only demonstrates reliability but also unveils a unique topological signature for WM-mediated functional networks. These networks inherently possess characteristics of efficient organization, such as small-worldness, modularity, and hub structures, as established by our graph-theoretical analyses. More critically, when contrasted with conventional GM-GM networks, GWM-HFNs exhibit a distinct profile: enhanced functional segregation alongside reduced global integration efficiency. This topological shift is a direct consequence of the GWM-HFN methodology, which defines GM-GM functional links based on their shared covariance profiles with WM tracts. Such an approach naturally groups GM regions that functionally ‘resonate’ with the same WM bundles, thereby strengthening intra-modular cohesion and revealing a functional architecture more explicitly sculpted by the brain’s WM scaffolding42,43,44. The resulting increase in modularity and local clustering suggests that GWM-HFN can delineate functional communities whose integrity is fundamentally tied to specific WM conduits.

The observed reduction in global efficiency and increased path length in GWM-HFNs, relative to GM-GM networks, likely signifies the multi-step nature of WM-mediated communication (GWM-HFN paths) versus potentially more direct GM-GM BOLD synchrony. This implies that while WM bundles facilitate specific and organized communication, the overall information transfer across the entire GWM-HFN might appear less direct or rapid when primarily channeled through these anatomically constrained routes24,25. This trade-off results in a modified small-world architecture, potentially favoring specialized processing within modules at the cost of global broadcasting efficiency.

Furthermore, the GWM-HFN framework reshapes the functional importance of nodes; our direct comparison revealed that while both frameworks identify a core set of shared hubs in regions like the middle temporal gyrus, GWM-HFN uniquely identified hubs in higher-order association areas (e.g., inferior frontal orbital gyrus) that were not prominent in the GM-GM network. Conversely, the conventional method highlighted hubs primarily in sensory and attention networks. This suggests that the elevated betweenness centrality of certain GWM-HFN hubs makes them critical control points for inter-modular communication specifically within this WM-mediated system, distinct from hubs identified in GM-GM networks that may simply reflect high overall synchrony. Thus, the topological characteristics of GWM-HFN provide a more mechanistic view of functional organization, emphasizing how WM bundles structure and constrain neural communication.

While the GWM-HFN framework introduces a distinct perspective by incorporating WM signals, its relationship with traditional GM-GM functional connectivity provides crucial context. Our findings indicate a considerable overlap (mean edge-level r ≈ 0.77, SLIM dataset), affirming that GWM-HFN captures fundamental patterns of synchronous neural activity. However, the more than 40% of unique variance captured by GWM-HFN underscores its capacity to reveal aspects of functional organization not apparent in GM-only analyses. This is particularly evident in the divergent similarity patterns between the two frameworks across network sparsity thresholds. The U-shaped similarity for intra-network connections suggests that while both methods capture the strongest ‘core’ links, they diverge on moderately-strong connections. In contrast, the progressive increase in inter-network similarity suggests that the frameworks converge on capturing broader patterns of inter-system communication after initially differing on the most specific long-range links. This highlights GWM-HFN’s unique sensitivity to specific WM-mediated pathways, particularly at sparse network densities.

A key contribution of GWM-HFN lies in its ability to capture distinct patterns of inter-individual variability. Our initial analyses suggested heightened variability in GWM-HFN, particularly in connections involving the basal ganglia and limbic system. However, a more rigorous variance decomposition analysis, which corrected for session-to-session measurement noise, revealed a more nuanced picture34. After accounting for noise, the overall magnitude of “true” inter-subject variability was not significantly different between the GWM-HFN and GM-GM frameworks. Critically, though, the spatial topographies of this true variability were largely distinct. GWM-HFN’s high-variability nodes were concentrated in the DMN and SMN, whereas the GM-GM framework’s variability was highest in higher-order association systems like the AN and FPN. This finding strongly suggests that the unique variance captured by GWM-HFN is not simply attributable to higher noise but rather taps into a genuine and spatially distinct source of biological differences related to individuals’ WM-mediated communication profiles45,46,47. Such sensitivity is paramount for fields like developmental neuroscience and clinical research, where understanding individual trajectories and susceptibility is key48.

These differences in captured variance and sensitivity to individual differences are also reflected in the distinct network topology of GWM-HFN compared to GM-GM networks, as detailed previously (enhanced modular segregation and reduced global integration efficiency). Such topological distinctions are a natural consequence of a network model that explicitly accounts for WM-mediated interactions, aligning with emerging perspectives that WM signals actively contribute to the organization and potential ‘rewiring’ of GM functional communities26. Thus, GWM-HFN provides not just a similar picture to GM-GM networks but a complementary one, enriched by the functional information carried by WM functional connectivity profiles and offering a more nuanced understanding of brain-wide communication.

Applying the GWM-HFN framework across the adult lifespan (SALD dataset) revealed significant age-related dynamics, predominantly characterized by a linear decline in global mean connectivity strength. This overarching negative trajectory aligns well with the established literature documenting widespread age-related degradation in both structural WM integrity49,50 and conventional GM functional connectivity5. It also resonates with findings from related WM-GM network models, such as the reduced global efficiency observed with increasing age in bipartite WM-GM networks24. This contrasts with the benchmark GM-GM analysis, which revealed an inverted U-shaped global trajectory, suggesting that WM-mediated connectivity may follow a more direct path of age-related decline.

Beyond this global trend, GWM-HFN demonstrated sensitivity to more complex, edge-specific age trajectories. While the majority of affected connections exhibited linear decreases, reinforcing the theme of age-related weakening, a notable subset displayed inverted U-shaped quadratic patterns, despite the global quadratic term being non-significant. These connections typically peaked in early adulthood (mean peak age ~34 years) before declining. The complexity of WM age-related changes is further highlighted by recent studies that reported both U-shaped patterns in static WM network connectivity strength and inverted U-shapes in the temporal variability of WM-GM connectivity across the adult lifespan22. This non-linear pattern is particularly compelling, as this peak age roughly coincides with the culmination of protracted maturation processes for certain cognitive functions and for WM microstructural properties, such as myelination51. The GWM-HFN may thus be capturing a critical window of maximal efficiency in WM-mediated functional communication during early to middle adulthood, followed by senescence potentially linked to the known microstructural deterioration of WM pathways later in life50. This finding supports the notion that certain localized functional systems undergo distinct developmental trajectories, a critical neurodevelopmental process that is obscured by global-level metrics.

Intriguingly, our findings (SALD dataset) also indicated that GWM-HFN and traditional GM-GM connectivity patterns become significantly more similar with advancing age52. This convergence could reflect several underlying processes. One possibility is age-related neural dedifferentiation, where diminished functional specialization of brain networks53,54 blurs the distinctions between connectivity reflecting direct GM synchrony and WM-mediated interactions, perhaps due to reduced specificity of WM-guided pathways or compensatory, more diffuse brain activity55. Alternatively, a ‘shared vulnerability’ scenario might explain this convergence, whereby common aging mechanisms like vascular or metabolic decline, and diffuse microstructural wear in both GM and WM24,49,50, could globally degrade both direct GM coupling and WM-pathway integrity, causing their functional signatures to appear more alike. Disentangling these potential contributors requires further research, but the GWM-HFN’s capacity to capture this age-related shift in network relationships, alongside broader linear declines and nuanced non-linear trajectories, highlights its value in comprehensively studying age-related functional brain changes and the evolving role of WM-mediated communication.

This observed GWM-HFN functional hyperconnectivity likely relates to the atypical WM neurodevelopment and microstructure frequently reported in ASD56,57. While diffusion MRI studies often indicate reduced microstructural integrity (e.g., lower FA) across widespread WM tracts58,59, and morphometric analyses show heterogeneity but potential aggregation of volume reductions in common pathways60, the relationship between these structural characteristics and functional connectivity is intricate. The functional hyperconnectivity captured by GWM-HFN might signify compensatory mechanisms attempting to overcome less efficient signaling along structurally atypical pathways, or perhaps reflect altered excitatory/inhibitory balances specific to WM-mediated communication routes. The validity of these findings is strengthened by two key observations. First, these hyperconnectivity patterns show high convergence with those identified by conventional GM-GM methods, indicating that GWM-HFN captures a core, recognized aspect of ASD pathophysiology. Second, our validation analysis on an adolescent and adult subsample confirmed that this hyperconnectivity pattern is a stable feature across development and not merely an effect driven by younger participants. This demonstrates the robustness of the GWM-HFN framework and its ability to capture core, age-invariant biological signatures of the disorder, even within a highly heterogeneous cohort. The additional alterations uniquely detected by GWM-HFN can thus be interpreted as complementary insights into the WM-mediated aspects of the condition. The prominent involvement of BGN connections in our GWM-HFN findings aligns with reports of altered structural network topology involving the BGN even in preschool ASD61, hinting at early developmental atypicalities in cortico-striatal circuits relevant to ASD symptomatology62,63.

Crucially, the clinical relevance of these GWM-HFN alterations was substantiated by a significant negative correlation between the mean hyperconnectivity strength and total ADOS-G scores. While seemingly counterintuitive, this complex relationship (greater GWM-HFN hyperconnectivity associating with less severe symptoms) may reflect a successful compensatory mechanism rather than a primary pathological feature. Given the well-documented structural WM deficits in ASD58,59, this increased functional coupling could represent an adaptive neural response to overcome underlying inefficiencies. In this context, individuals with more severe symptoms may be those who fail to mount this compensatory response, a possibility consistent with the profound heterogeneity of the disorder60. Further research is needed to explore this connection across different symptom domains and developmental stages59.

While our current study focused on ASD, the established vulnerability of WM pathways across a range of psychiatric disorders45 suggests that sensitive functional probes like GWM-HFN could be valuable more broadly. For ASD specifically, GWM-HFN’s ability to detect robust functional alterations potentially missed by GM-GM analysis, coupled with its association with clinical severity, highlights its promise for complementing structural MRI and advancing our understanding of WM network dysfunction in this complex condition.

The functional significance of GWM-HFN was further underscored by its ability to explain interindividual variance in cognitive performance within the BGSP dataset. Initial PLS regression analyses revealed that GWM-HFN connectivity patterns were significantly associated with Shipley vocabulary scores and Shipley-Hartford estimated IQ. In a direct benchmark comparison, the conventional GM-GM network also showed a significant association with vocabulary but failed to detect a link to estimated IQ, highlighting the unique sensitivity of our WM-informed framework.

For the GWM-HFN framework, the stable, high-weight connectivity patterns underlying both associations were remarkably consistent. They were characterized by predominantly negative weights within the DMN and positive weights between the DMN and the VN, with a high overlap between the contributing edges for both measures (Jaccard index = 0.62)64,65,66. Intriguingly, the benchmark GM-GM network’s significant association with vocabulary was driven by the same neurobiological pattern—negative intra-DMN and positive DMN-VN connectivity. This indicates that both methods capture a shared, fundamental substrate for language-related cognition, while GWM-HFN provides additional sensitivity to broader cognitive functions like IQ.

To more rigorously test these brain-behavior relationships at an individual level, we employed the BBS modeling method, an approach designed to assess the predictive capacity of connectomic features for individual phenotypes39. Our application of BBS modeling provided crucial nuanced validation: GWM-HFN connectivity significantly predicted individual Shipley vocabulary scores, identifying specific edge contributions. This robust individual-level prediction for vocabulary, surviving cross-validation, strongly suggests that certain WM-mediated functional pathways captured by GWM-HFN are indeed tightly linked to this specific cognitive skill.

Interestingly, while the initial PLS analysis indicated an association with Shipley-Hartford estimated IQ, this did not translate into significant individual-level prediction under the BBS framework. This divergence is informative. PLS identifies broad patterns of covariance at the group level, whereas BBS provides a stricter test of individualized predictive utility. The lack of significant IQ prediction via BBS could suggest that either the true effect size for this particular IQ measure, while detectable by PLS, is insufficient for robust individual prediction with the current GWM-HFN feature set, or that the relationship between GWM-HFN connectivity and this IQ estimate is more complex and perhaps less directly linear than that observed for vocabulary. Sripada et al. themselves discuss how resting-state connectomes contribute to inter-individual variation39; it’s plausible that GWM-HFN features relevant to IQ are more diffusely represented or interact in a manner not fully captured by the specific BBS implementation used. Nevertheless, the successful individual prediction of vocabulary scores via GWM-HFN strongly indicates that this framework captures behaviorally relevant variance tied to specific WM-mediated communication pathways, highlighting its potential beyond group-level associations and underscoring that WM functional signals, as integrated by GWM-HFN, are indeed meaningfully related to cognitive function.