Abstract

Membrane proteins are crucial in cellular processes like signal and energy transduction and are influenced by the properties of the surrounding lipid bilayer. Fatty acids, key components of phospholipids, adjust membrane properties in response to environmental changes; however, their direct effect on membrane protein activity is poorly understood. Cyclopropane fatty acids (CFAs) are produced by a cyclopropane fatty acid synthase (Cfa) by adding a methylene group to unsaturated fatty acids. CFAs are abundant in the membranes of Escherichia coli, particularly during the stationary phase or stress conditions, and are believed to contribute to modulating membrane rigidity and permeability, yet their functional role in membrane protein regulation remains unclear. Here, we examined the effect of CFAs on the activity of NhaA, a Na+/H+ antiporter in E. coli, using Δcfa mutants deficient in CFA synthesis. NhaA activity exhibits a strong negative correlation with the ratio of cyclopropane to saturated fatty acids. Molecular dynamics simulations showed that CFA reduces NhaA-phospholipid interactions, restricting the conformational change needed for activation. These results suggest that membrane protein activity can be regulated by fatty acid composition, with CFAs playing a significant role.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The lipid bilayer of Escherichia coli cell membranes is composed of phospholipids, which comprise head groups and fatty acids. The primary phospholipids in E. coli are phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and cardiolipin (CL), with respective ratios of approximately 70%, 20%, and 10%1. Phospholipids play a critical role in modulating membrane protein activity through structural stabilization and dimerization2,3. The relationship between phospholipid head groups and membrane protein activity has been the focus of most research. However, studies specifically examining the relationship between fatty acid composition and membrane protein activity are limited4,5,6.

The fatty acids within E. coli membrane lipids are broadly categorized into three types: saturated fatty acids (SFA) like palmitic acid (C16:0); unsaturated fatty acids (UFA) such as palmitoleic acid (C16:1) and cis-vaccenic acid (C18:1); and cyclopropane fatty acids (CFA), which contain a cyclopropane ring on the carbon chain, like cis-9,10-methylene hexadecenoic acid1(Fig. 1a). CFAs are found in certain bacteria, including Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Escherichia, and Salmonella7,8,9. These fatty acids are formed when cyclopropane fatty acid synthase (cfa) adds a methylene group, derived from the methyl group of S-adenosylmethionine, across the double bond of UFAs10,11. Generally, cell membrane fatty acid composition affects membrane fluidity, often changing in response to environmental conditions. CFA synthase is a cytoplasmic enzyme that modifies phospholipids primarily in the inner membrane. Furthermore, lipids from the inner membrane can be translocated to the inner leaflet of the outer membrane in E. coli. Therefore, CFAs may also be present in the outer membrane, particularly in its inner leaflet. Additionally, CFAs contribute to tolerance against various stresses, including ethanol exposure12,13, high osmotic pressure14,15, low pH16,17, and repeated freeze-thaw cycles18,19 (Fig. 1a). Despite these established roles, the mechanisms by which they confer stress tolerance remain unclear.

a Schematic representation of the synthetic pathway and physiological role of fatty acids in E. coli. b Fatty acid composition of wild type, ∆cfa, ∆fabR single disruptants, and ∆cfa∆fabR double disruptant strains. Black bars represent the proportion of SFA, grey bars indicate UFA, and white bars indicate CFA within the total fatty acid composition. Representative results of three independent experiments are shown.

To explore the relationship between fatty acid composition and membrane protein activity, particularly the role of CFAs in cell membranes, we focused on Na⁺/H⁺ antiporters, which transport ions in opposite directions across the membrane. Na⁺/H⁺ antiporters are essential for maintaining intracellular pH, Na⁺ concentration, and cell volume20. E. coli has three recognized Na⁺/H⁺ antiporters—NhaA, NhaB, and ChaA21. NhaA can adapt to high salinity at alkaline pH22, while the ΔnhaB strain exhibits a similar phenotype to that of the wild type (WT), suggesting NhaA as the primary Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter in E. coli23. Recent research indicates that lipids surrounding Na⁺/H⁺ antiporters provide structural support, enabling the large-scale conformational changes necessary for transport24. Additionally, in CL-deficient strains, the NhaA dimer ratio and dimer stability decrease25. CL can stabilize the dimeric form of NhaA by interacting at the dimer interface, where two monomers face each other, affecting growth under high salinity, although antiporter activity remains unchanged under those conditions25. These observations underscore the broader significance of membrane lipids in regulating Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter function. However, the influence of membrane phospholipid fatty acid composition on Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter activity remains unclear. In this study, we examined the correlation between fatty acid composition and NhaA activity by comparing NhaA functionality across strains with varying fatty acid profiles and analyzed the interaction between fatty acids and NhaA through molecular dynamics simulation.

Results

Fatty acid composition of cfa and fabR disruptants

To investigate the relationship between fatty acid composition and Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter activity, we engineered E. coli strains with varying fatty acid profiles. We disrupted the cfa gene, which is essential for converting UFAs into CFAs, to examine the role of CFAs. As expected, the disruption of cfa eliminated CFAs from the membrane lipids of E. coli26. The fabR gene, which encodes a transcriptional repressor of genes for UFA synthesis, was disrupted to explore the importance of UFAs (Fig. 1a). Previous studies indicate that fabR disruption increases the UFA proportion in membrane lipids27. Additionally, we constructed a ΔcfaΔfabR double disruptant strain to assess the combined contributions of SFAs, UFAs, and CFAs to Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter activity. We analyzed the fatty acid composition of these strains when cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium. As anticipated, CFAs were entirely absent in the Δcfa strain, while the proportion of UFAs and CFAs in the total fatty acid content increased from 50% to 70% in the ΔfabR strain. FabR is a transcriptional repressor that inhibits the expression of fabA and fabB, which are involved in converting SFAs to UFAs. In the ΔfabR strains, repression of fabA and fabB is relieved, likely resulting in increased UFA levels. The ΔcfaΔfabR strain exhibited characteristics of Δcfa and ΔfabR strains (Fig. 1b, Table 1). In the ΔcfaΔfabR strain, a small amount of CFA signal was detected using gas chromatography despite the disruption of the cfa gene. One possible explanation is that methylene-hydroxymyristic acid, which is present in lipid A and elutes at a similar retention time, may have been detected instead.

Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter activity measurement in fatty acid composition mutants

Subsequently, we assessed the Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter activity in the cfa and fabR disruptant strains. Antiporter activity was measured using inside-out membrane vesicles from E. coli cells, with activity normalized against membrane-bound lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity. To verify that LDH activity was unaffected by the fatty acid composition changes in the cfa and fabR disruptants, we measured LDH “quench” values using acridine orange fluorescence (a pH-sensitive fluorescence dye). In this assay, quenching refers to the loss of acridine orange fluorescence resulting from the acidification of E. coli inverted membrane vesicles. LDH activity drives this acidification, which transfers electrons from lactate oxidation to cytochromes in the respiratory chain, resulting in H+ translocation across the membrane (Fig. 2a). The quench values did not significantly differ among the strains (Supplementary Fig. 1a), confirming that LDH activity was consistent across all samples regardless of fatty acid composition. Furthermore, to directly assess LDH protein levels, we introduced a His-tag at the C-terminus of the chromosomal dld gene and performed Western blotting. The results showed comparable LDH expression across all strains, supporting the validity of using LDH activity as an internal reference (Supplementary Fig. 1b and c). Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter activity was measured using E. coli inverted membrane vesicles containing NhaA. In addition, pH changes inside the vesicles were monitored using acridine orange. When Na⁺ is added, active NhaA transports Na⁺ into the vesicles in exchange for H⁺, leading to an alkalinization of the vesicle interior. This activity reduces the quenching of acridine orange fluorescence, which can be measured over time. The rate and extent of this fluorescence change reflect the activity of the Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter (Fig. 2b). The Δcfa and ΔcfaΔfabR strains exhibited significantly higher antiporter activity, approximately 1.4-fold than that of the WT strain. Conversely, the ΔfabR strain showed a 0.5-fold decrease in activity. We plotted the fatty acid composition ratios—such as CFA, UFA, SFA, CFA/SFA, CFA/UFA, and SFA/UFA—against the antiporter activity for each strain. Among these, the CFA/SFA ratio showed the strongest relationship to NhaA activity. Pearson correlation analysis revealed a strong negative correlation between the CFA/SFA ratio and antiporter activity (r = −0.98) (Fig. 2c), indicating that higher proportions of CFAs relative to SFAs are associated with reduced NhaA activity. These findings suggest that CFAs may exert an inhibitory effect on the antiporter, whereas SFAs may contribute positively to its function. The correlation appeared strong; nonetheless, the analysis was based on four data points, and thus, the result should be interpreted with caution. E. coli possesses three Na⁺/H⁺ antiporters: NhaA, NhaB, and ChaA, with NhaA serving as the primary Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter21. Consequently, the observed changes in antiporter activity due to fatty acid composition may primarily reflect NhaA activity. This hypothesis was further investigated in the following experiment.

a Schematic diagram of NhaA activity assay. b Bars display the ratio of fluorescence dequenching upon NaCl addition and fluorescence quenching upon lactic acid addition. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analysis was conducted using a two-sample t-test (*: P < 0.05). c Correlation between Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter activity and the CFA/SFA ratio, with the R² value of a linear trendline shown.

Effect of fatty acid composition changes on NhaA activity

To investigate whether the CFA/SFA ratio influences NhaA activity, we constructed a Δ3 strain with disruptions in nhaA, nhaB, and chaA. To enable NhaA expression in this strain, we cloned the nhaA gene into the pMW118 vector and introduced it into the Δ3 strains. Initially, we verified NhaA functionality by assessing Na⁺ tolerance (Fig. 3a). As expected, the Δ3 strain carrying an empty vector (EV) displayed Na⁺ sensitivity, consistent with previous findings21. However, the strain expressing NhaA exhibited robust growth similar to that of the WT, indicating successful NhaA expression and its ability to complement the Na⁺-sensitive phenotype of the Δ3 strain.

a Growth of WT/EV (mean: grey circle, individual data point: grey dot), Δ3/EV (mean: blue circle, individual data point: blue dot), and Δ3/ nhaA (mean: red circle, individual data point: red dot) strains in LB medium with 0.7 M NaCl. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Small error bars are covered by symbols. b Bars represent the dequenching-to-quenching ratio for Δ3-based ∆cfa and ∆fabR single disruptants. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analysis was conducted using a two-sample t-test (*P < 0.005, **P < 0.01). c Western blot analysis of His-tagged NhaA expressed from the genome: left lane, NhaA-His in WT strain; middle lane, NhaA-His in Δcfa strain; right lane, NhaA-His in ΔfabR strain. d Digitized fluorescence intensity of the NhaA-His band. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analyses was conducted using two-sample t-tests (P ≥ 0.05). n.s. indicates non-significance.

Next, we disrupted the cfa or fabR gene in the Δ3 strains and introduced nhaA to assess the Na⁺/H⁺ transport activity of NhaA. We also evaluated whether LDH activity was affected in the Δ3Δcfa and Δ3ΔfabR disruptants (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 2). The Δ3/nhaA strain showed Na⁺/H⁺ transport activity similar to the WT, confirming that the plasmid-expressed NhaA was functioning effectively. In contrast, the Δ3Δcfa/nhaA strain exhibited 2.2-fold higher activity than the Δ3/nhaA strain, while the Δ3ΔfabR/nhaA strain displayed only 0.7-fold the activity of the Δ3/nhaA strain. These results aligned with those obtained in analyses based on the WT strain (Fig. 2b). Thus, we concluded that changes in Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter activity in WT strains are primarily due to modifications in NhaA activity.

Quantification of membrane-embedded NhaA in WT, Δcfa, and ΔfabR strains

We examined NhaA expression in WT, Δcfa, and ΔfabR cells to determine whether the observed differences in fluorescence intensity between the Δ3/nhaA strain and the Δ3ΔfabR/nhaA strain were caused by changes in the CFA/SFA ratio rather than differences in NhaA expression levels. Since expression of NhaA in all strains is driven by the same promoter, transcription levels should be consistent across all strains. However, variations in membrane lipid fatty acid composition could potentially impact the amount of NhaA embedded in the membrane. To quantify membrane-embedded NhaA, we expressed His-tagged NhaA from the genome and performed Western blotting (Fig. 3c, d). The results indicated that the membrane-embedded NhaA did not significantly differ between the WT, Δcfa, and ΔfabR strains, suggesting that the fatty acid composition of membrane lipids does not affect the quantity of NhaA incorporated into the membrane.

Phospholipid composition analysis

We analyzed whether the phospholipid headgroup composition differed among E. coli mutant strains by extracting lipids from each strain and examining their phospholipid headgroup composition (Fig. 4a, b, and Supplementary Fig. 3). Lipids extracted from the ∆3, ∆3∆cfa, and ∆3∆fabR strains were analyzed using thin-layer chromatography (TLC). In all strains, PE was the dominant lipid species, accounting for 70–85% of the total phospholipids, followed by PG at 15–25%, while CL constituted only a few percent. The ∆3∆cfa strain showed a tendency toward slightly higher PE and lower PG than that of the ∆3 strain. These small shifts are unlikely to account for the changes in activity. Consistent with our molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), the Δcfa membrane—corresponding to the ∆3∆cfa strain—showed stronger overall NhaA–membrane interactions and enhanced PG contacts at the loops flanking transmembrane helix 5 (TM5).

a Phospholipids were extracted from mutants of E. coli, and TLC analysis was performed. b Phosphorus assay was performed for each of the following: CL, PE, PG, and PS. ∆3/nhaA (white bar), ∆3∆cfa/nhaA (grey bar), ∆3∆fabR/nhaA (black bar). Data represent mean ± SE (n = 3). Statistical analyses was conducted using two-sample t-tests (P ≥ 0.05). n.s. indicates non-significance.

Effect of fatty acid composition on NhaA-mediated sodium tolerance

We examined whether variations in fatty acid composition influence NhaA-mediated sodium tolerance. Na⁺/H⁺ antiporters are crucial for maintaining intracellular pH and Na⁺ homeostasis in E. coli20. Since NhaA activity is highly pH-dependent and operates optimally at high pH, we conducted growth experiments using a jar fermenter to maintain the pH at 8.0. Sorbitol (1.35 M, equivalent osmotic pressure to 0.7 M NaCl) was added to the growth medium as a control. Under these conditions, all three strains (Δ3/nhaA, Δ3Δcfa/nhaA, and Δ3ΔfabR/nhaA) displayed similar growth, indicating no significant differences in osmotic pressure resistance among them (Fig. 5a). We further conducted a growth experiment in a medium containing 0.7 M NaCl. In this setup, the Δ3Δcfa/nhaA strain exhibited a higher OD660 than the Δ3/nhaA strain, while the Δ3ΔfabR/nhaA strain showed a lower OD660 than the Δ3/nhaA strain (Fig. 5b). To further investigate whether fatty acid composition affects E. coli growth, we introduced a cfa-expressing plasmid into the ∆3/nhaA, ∆3∆cfa/nhaA, and ∆3∆fabR/nhaA strains and conducted growth experiments. The results showed that the growth of the ∆3∆cfa/nhaA strain carrying the cfa plasmid was reduced, reaching a level comparable to that of the ∆3/nhaA/cfa strain (Fig. 5c). These findings suggest that fatty acid composition influences cell growth in a manner likely mediated by NhaA activity, reflecting an in vivo effect of fatty acid composition on NhaA function.

Growth of NhaA-expressing E coli strains in culture media with a 1.35 M sorbitol and b 0.7 M NaCl. c Growth curves of Δ3-based strains harboring nhaA and cfa genes in culture media with 0.7 M NaCl. ∆3/nhaA and ∆3/nhaA/cfa (mean: grey circle, individual data point: grey dot), ∆3∆cfa/nhaA/ and ∆3∆cfa/nhaA/cfa (mean: red circle, individual data point: red dot), ∆3∆fabR/nhaA/ and ∆3∆fabR/nhaA/cfa (mean: blue circle, individual data point: blue dot). Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analyses performed using two-sample t-tests (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.1).

Molecular dynamics simulations

To investigate the effect of lipid composition on NhaA, we performed MD simulations of NhaA embedded in model membranes representing the Δcfa and WT strains. The lipid molecules used in these model membranes were selected based on the fatty acid composition ratios from our experiments, combined with known phospholipid head group ratios in E. coli1. In the model membrane, the PE:PG:CL ratio was set to 81.2:14.6:4.2. The lipid compositions of the Δcfa and WT strain model membranes are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4.

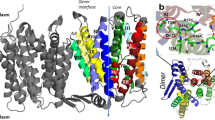

Initially, we calculated the interaction energies between NhaA and each of the membranes. For the NhaA and the WT strain membrane, the interaction energy was -3620 ± 120 kJ/mol, while the energy for the Δcfa strain membrane was -3820 ± 60 kJ/mol, indicating a stronger interaction between NhaA and the Δcfa membrane than with the WT membrane. To analyze the contribution of individual residues to this difference, we calculated the interaction energies between each NhaA residue and the entire membrane (Fig. 6). This analysis revealed that variations in interaction energy are primarily associated with amino acids in the periplasmic and cytoplasmic loops, located at the membrane-solvent interface. Focusing on TM5, which contains the Na⁺ binding site (Asp163, Asp164), we observed that the loops at both ends of TM5 include more amino acids with increased interaction energy in the Δcfa membrane than in other TM helices (Figs. 6 and 7a). The amino acid residues on the periplasmic loop interact with the phosphate and head groups of membrane lipid molecules (Fig. 7b), suggesting that these differences in interactions may contribute to specific biological activities. We further examined the contributions of individual lipid classes to the protein-membrane interaction energies. The total interaction energies with PE, PG, and CL were slightly higher in the Δcfa membrane; nonetheless, the differences were not statistically significant (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, in the TM5 loop region, PG exhibited a more pronounced increase in interaction energy under Δcfa conditions, implying a possible local enrichment or tighter association (Supplementary Table 2). These MD observations, obtained with fixed PE:PG:CL ratios, support that the minor headgroup shifts measured by TLC (Fig. 4) are unlikely to be the primary driver of the activity difference.

Grey and orange bars represent the average interaction energies for the NhaA-WT and NhaA-Δcfa systems, respectively. Open black and orange circles indicate values from individual simulations. Error bars denote the SE of the mean (n = 4). Because the data are derived from MD simulations, statistical tests were used only as descriptive indicators of variability among independent simulations. Although P-values for several residues were in the range of 0.05–0.15, non-overlapping error bars suggest consistent trends in interaction energies between the NhaA-WT and NhaA-Δcfa systems. Red arrows indicate residues with increased interaction energy, and blue arrows indicate residues with decreased interaction energy in the NhaA-Δcfa system compared with those in the NhaA-WT. Black, pink, and green horizontal bars indicate transmembrane segments, periplasmic loops, and cytoplasmic loops, respectively. Numbers above the bars correspond to helix or loop indices.

a Residues with significant interaction energy differences between NhaA-WT and NhaA-Δcfa systems were mapped onto the three-dimensional structure. Residues with stronger membrane interactions in the NhaA-Δcfa system are shown in orange, except for those in TM5, which are shown in magenta. Residues showing weaker interactions in the NhaA-Δcfa system are shown in blue. Residues in TM5 are highlighted in magenta. b Close-up of the interaction site between membrane lipid head groups and residues on the cytoplasmic loop of NhaA. c Comparison of TM5 helix bending between systems: TM5 of NhaA-Δcfa (cyan) was superimposed on TM5 of NhaA-WT (green) to demonstrate angle differences. (d) Cytoplasmic gate residues, with five hydrophobic residues (Val75, Ile134, Met157, Ala160, Ile161) shown in green and two aspartate residues (Asp163, Asp164) shown in orange.

Previous computational studies have shown that TM5, positioned between the core and dimerization domains, bends near Asp163 during the transition from the inward-facing to the outward-facing state within the transport cycle, with bending angles ranging from 5° to 22° across pH levels 7 to 1028. We compared the angles of the Cα atoms of Phe174, Asp163, and Leu152 in TM5 across the WT and Δcfa membrane systems (Fig. 7c). The NhaA structure used in our simulations corresponds to the inactive state at low pH, where TM5 is almost linear. Although no major conformational changes associated with the inward-to-outward transition were observed during the simulations, the bending angles calculated for the Δcfa membrane system (15.1° ± 2.2) were slightly larger than those in the WT membrane system (10.3° ± 2.4).

Following computational analysis of the TM5 bending angles, another critical structural feature of NhaA, the cytoplasmic gate29, was further examined in this study. This gate is composed of a series of hydrophobic residues that are essential for regulating access from the cytoplasm to the active site28. Notably, the deprotonation of Asp164, triggered by an increase in pH, initiates the opening of this gate, permitting water molecules and ions to flow into the core region. This pH-dependent structural transition is crucial for NhaA activation, aligning with its function in maintaining cellular ion balance under varying pH conditions. In comparing the gyration radius of this gate region, the Δcfa membrane showed a slightly larger value than that of the WT membrane (4.7 ± 0.2 nm vs. 4.2 ± 0.2 nm), and correspondingly, some amino acid residues were observed to be slightly shifted outward (Fig. 7d).

To explore the role of fatty acids in membrane structure, we calculated the deuterium order parameter (SCD), which can also be experimentally measured using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, for the predominant lipid species, PYPE (1-palmitoyl-2-palmitoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine) and PMPE (1-palmitoyl-2-cis-9,10-methylene-hexadecanoic-acid-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine), in each membrane (Fig. 8a). The SCD reflects the average orientation and order of lipid tails relative to the normal vector of the bilayer, with an SCD value of 0.5 indicating perfectly ordered lipid tails and values approaching 0 indicating a random distribution. SCD was assessed as a function of carbon atoms along the lipid tails. In the Sn-1 chain, both lipids have SFAs with a 16-carbon chain, resulting in minimal SCD differences. However, in the Sn-2 chain, the SCD value for C17 in PMPE is notably higher, suggesting significant steric hindrance due to the presence of cyclopropane rings (Fig. 8b). Such steric hindrance from large substituents restricts molecular flexibility and influences membrane packing. To further assess membrane packing, we determined the average area per lipid for both membranes. The Δcfa membrane displayed a value of 57.0 ± 0.1 Ų, while the WT membrane had a slightly larger value of 58.0 ± 0.2 Ų, indicating a looser lipid packing in the WT membrane than in the Δcfa membrane. Within the first solvation shell of NhaA, both membranes exhibited even smaller values, with 41.0 ± 0.5 Ų for Δcfa and 42.7 ± 0.8 Ų for WT. These results suggest that the larger average lipid area of the WT membrane is influenced by the presence of cyclopropane rings, whereas the tighter packing of the Δcfa membrane may enhance its interaction with NhaA.

a Lipid chemical structures of PMPE (black circle) and PYPE (orange square). b SCDs for PMPEs of the WT membrane system and for PYPEs of the Δcfa membrane system. The upper figure represents Sn-1, while the lower figure illustrates Sn-2. Orange lines with squares represent the PYPE of the Δcfa membrane system, and black lines with circles represent the WT membrane system. Standard errors are smaller than the symbols.

MD simulations revealed that the Δcfa membrane, lacking cyclopropane rings in its fatty acids, exhibits tighter packing than the WT membrane. This tighter packing results in stronger interaction energies between the membrane and NhaA. The increased membrane interaction energy could induce conformational changes in TM5, which contains Asp163 and Asp164—key residues in Na⁺ binding. These conformational changes may widen the pathway for Na⁺ and water. Collectively, these findings suggest that the enhanced activity of NhaA observed in the Δcfa membrane could be attributed to these structural and energetic interactions within the membrane.

Discussion

Bacteria adapt to environmental changes by modulating various cellular processes, including altering the fatty acid composition of membrane lipids. However, the specific impact of changes in fatty acid composition on membrane protein activity is unclear. While the interactions between membrane proteins and phospholipid head groups, another major component of phospholipids, have been explored in several studies2,3, fewer studies have addressed the relationship between fatty acid composition and membrane protein activity, despite the known influence of free fatty acids on protein function4,5,6,30,31,32,33. Notably, we further speculate that CFAs may influence bacterial stress tolerance by modifying global membrane properties, as well as by regulating the activity of key membrane proteins, such as NhaA. As NhaA plays an essential role in ion homeostasis, pH regulation, and survival under stress conditions, modulating its activity via CFA-induced changes in membrane packing could be one mechanism by which bacteria enhance adaptability. This raises the possibility that CFA biosynthesis contributes to the dynamic tuning of protein function in response to environmental stress.

We demonstrated that the activity of NhaA, the primary Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter in E. coli, varies with changes in membrane lipid fatty acid composition. We observed that antiport activity increased in the Δcfa strain and decreased in the ΔfabR strain (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). MD simulations of NhaA in WT and Δcfa membranes suggest that these activity changes result from alterations in membrane packing. Higher levels of SFAs, which are less bulky, decrease membrane fluidity, while higher levels of UFAs, which are bulkier, increase fluidity34. The direct effect of CFAs on membrane fluidity is not fully understood; nevertheless, some studies based on MD simulations suggest that converting cis-unsaturated fatty acids into CFAs increases fluidity compared with membranes containing trans-UFAs35, whereas spectroscopic observations have indicated that higher proportions of CFAs are associated with decreased fluidity due to a more rigid bilayer36. Our results indicate that converting UFAs to CFAs increases the area per lipid, thereby loosening membrane packing. Consequently, membrane packing in the Δcfa strain is tighter than in the WT strain. This tighter packing likely enhances membrane-protein interactions, potentially facilitating conformational changes required for protein transport. Indeed, our MD simulations support this hypothesis. However, future studies should employ structure-guided mutagenesis, such as more conservative amino acid substitutions, which may help clarify the specific contribution of these residues to CFA sensitivity, while minimizing the risk of impairing overall NhaA function.

NhaA typically forms a dimer in E. coli, and recent findings suggest that CL, an anionic phospholipid, is present at the dimer interface and contributes to dimer stability25,37,38. Additionally, phospholipids are believed to occupy positions between core and dimer domains, stabilizing flexible domain connections and promoting conformational shifts during transport24. Thus, interaction with phospholipids appears to be beneficial for NhaA activity. Based on our MD simulation and experimental results, we hypothesize that in the ∆cfa strain, which lacks cyclopropane rings and exhibits tighter lipid packing, enhanced Na⁺ transport activity was observed because of the bending of the TM5 region of NhaA, resulting in higher Na⁺ efflux than in the WT. In contrast, the WT, which shows lower NhaA activity than ∆cfa, exhibited delayed growth, likely due to reduced Na⁺ efflux from the cytoplasm (Fig. 9).

CFAs in E. coli are associated with stress tolerance, including exposure to ethanol, high osmotic pressure, low pH, and repeated freeze-thaw cycles12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. However, the relationship between CFAs and membrane protein activity has been examined in only a few studies. Here, we identified that CFAs can modulate membrane protein activity by altering membrane packing. As cells enter the stationary phase, changes in cellular states, such as gene expression and cell proliferation, occur dynamically, suggesting that CFA production may contribute to these changes by modulating the activity of membrane proteins. For instance, the transcription of the nhaA gene is tightly regulated by hns and nhaR, with Histone-like Nucleoid Structuring protein (H-NS) acting as a repressor in response to Na⁺, while NhaR acts as an activator in response to intracellular Na⁺39. Thus, changes in NhaA activity resulting from fatty acid composition provide an additional layer of NhaA regulation.

An important future direction will be to assess how regulating cfa expression under different physiological conditions influences NhaA activity. Since cfa is tightly regulated by transcriptional factors such as NhaR and H-NS, its expression level varies with growth phase and environmental stimuli. For example, CFA synthesis is typically low during the exponential phase and increases in the stationary phase. Evaluating NhaA activity in cells under different conditions—where CFA levels differ naturally—could provide further insight into how membrane fatty acid composition dynamically modulates antiporter function in response to environmental and physiological cues.

Methods

Strains, media, and strain construction

The E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Strain DH5α was used as the cloning host. Generally, E. coli cells were cultured in LB medium, consisting of 10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, and 10 g/L NaCl. When necessary, NaCl was replaced with KCl in the LB medium, and ampicillin was added at a concentration of 100 µg/mL as required. To test growth testing using a jar fermenter, a medium containing 20 g/L glucose (separately sterilized), 6 g/L Na₂HPO₄, 3 g/L KH₂PO₄, 1 g/L NH₄Cl₂, 5 g/L yeast extract, 10 mg/L MnSO₄·7H₂O, 10 mg/L thiamine·HCl, 2 g/L MgSO₄·7H₂O (separately sterilized), 200 mg/L FeSO₄·7H₂O (separately sterilized), and either 1.35 M sorbitol or 0.7 M NaCl was used. An overnight culture in 80 mL of LB medium in a 2 L Erlenmeyer flask at 30°C was transferred to a 6 L jar fermenter containing 1.6 L of medium. Cultivation proceeded at 30°C, with an agitation rate of 600 rpm and aeration at 1.6 L/min. The pH was maintained at 8.0 by adding 20% (w/v) NH₄OH.

We constructed several strains with distinct fatty acid compositions. The primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Supplementary Data 1. The Δcfa strain was constructed using a two-step homologous recombination process. First, the cfa gene was replaced with the sacB_cat cassette40. For homologous recombination, the 700-bp regions upstream (cfaup) and downstream (cfadn) of the cfa gene were amplified. These two fragments, along with the sacB_cat cassette, were used as templates for the subsequent polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify the cfaup-sacB_cat-cfadn fragment. This amplified fragment was introduced into competent wild-type cells harboring pKD46 via electroporation. Chloramphenicol-resistant transformants were selected on LB agar plates containing chloramphenicol. In the second step, the sacB_cat cassette was replaced by the cfa-deleted fragment. The cfaup and cfadn regions were again amplified and used as templates in PCR to produce the cfaup-cfadn fragment. This fragment was introduced into competent E. coli cfa::sacB_cat cells harboring pKD46 via electroporation. Transformants resistant to sucrose were then selected on LB agar plates containing sucrose. His-tagged NhaA-expressing strain was constructed following the same procedure as for Δcfa.

To quantify the protein production level of membrane-bound LDH, we introduced a His-tag at the C-terminus of the chromosomal dld gene, which encodes the membrane-bound LDH, using the Quick & Easy E. coli Gene Deletion Kit (Gene Bridges, Germany). Using a primer containing 50 bp upstream and 50 bp downstream of the stop codon of the dld gene, the kanamycin resistance cassette was amplified using PCR and introduced into the ∆3, ∆3∆cfa, and ∆3∆fabR strains.

Plasmid construction

We constructed a plasmid named pMW-nhaA using the pMW118 vector (NIPPON GENE, Japan) to produce NhaA. The primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Supplementary Data. The plasmid construction process was as follows: first, PCR amplification of the trp promoter was performed using the primers Ptrp_pMW118_InF_F and Ptrp_Ratg; second, the nhaA gene was amplified using the primers nhaA_Ptrp_F and nhaA_pMW118_InF_R. These two PCR fragments were subsequently used as templates for a subsequent PCR with primers designed for In-Fusion HD cloning (TaKaRa Bio, Japan). The resulting PCR product was purified via agarose gel electrophoresis and subsequently inserted into a linearized pMW118 vector using an In-Fusion HD cloning reaction.

The cfa gene was PCR-amplified from E. coli genomic DNA and inserted into the pSTV28 vector (TaKaRa Bio, Japan) using the In-Fusion HD seamless cloning method, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cfa gene was expressed from the lac promoter of the pSTV28 vector.

Analysis of fatty acid composition

Total lipids were extracted from E. coli using the Bligh and Dyer method41. The extracted lipids were subsequently methylated using a Fatty Acid Methylation Kit (Nacalai Tesque, Japan). The resulting fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were analyzed using gas chromatography (GC-2014; Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a flame-ionization detector and a capillary column (ULBON HR-SS-10, 0.25 mm diameter, 25 m length; Shinwa Kako, Bangkok, Thailand). The column temperature was held at 190°C for 10 min, with a carrier gas (nitrogen) flow rate of 0.89 ml/min. FAMEs were identified by comparing their retention times with those of standard FAMEs. To calculate fatty acid composition, palmitic acid, palmitoleic acid, cis-vaccenic acid, and cyclopropane fatty acids (C17 and C19) were defined as the major fatty acids in E. coli. The percentage of each fatty acid was calculated based on the peak area obtained from gas chromatography, using the total area of these defined fatty acids as 100%.

Assay of Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter activity

Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter activity was assessed using a fluorescence quenching method with everted membrane vesicles, following previously described protocols42,43. Everted membrane vesicles were prepared in Tris–Sucrose–Choline–Dithiothreitol buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 250 mM sucrose, 140 mM choline-Cl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, and pH 7.4) at 4 °C. The fluorescence assay was conducted in a 150 μL reaction mixture containing 20 μg of membrane protein, 0.8 μM acridine orange, 150 mM KCl, 50 mM Bis-Tris propane, and 5 mM MgCl₂, with the pH adjusted to 8.0 using HCl. After energizing the reaction with 2.7 mM D-lactate, fluorescence quenching was monitored until a steady state was reached. Subsequently, 13 mM NaCl was added to the mixture. The fluorescence of acridine orange was measured on a SpectraMax i3 (Molecular Devices, USA) with an excitation and emission wavelengths of 493 nm and 530 nm, respectively. To calculate the percentage of dequenching/quenching, the following formula was used.

\({F}_{{quench}}\) is fluorescence intensity after D-lactate addition, representing the quenched state due to proton accumulation. \({F}_{{quench}}\) is fluorescence intensity after Na⁺ addition, representing the dequenched state following proton efflux mediated by NhaA activity.

Western blotting

The membrane fraction was prepared by disrupting cells with a French press, followed by ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g, 1 h, 4 °C) for purification. The resulting pellet was dissolved in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), mixed with Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer containing 10% SDS, and loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel. Proteins were subsequently transferred to a Polyvinylidene Difluoride (PVDF) membrane, which was blocked with 3% (w/v) skim milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T). The PVDF membrane was probed with anti-His-tag antibodies (Medical & Biological Laboratories, Aichi, Japan) at a 1:1000 dilution as the primary antibody, followed by incubation with an anti-Rabbit IgG Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (Promega, Madison, USA) as the secondary antibody. Protein detection was performed using the Luminata™ Forte Western HRP Substrate (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and visualized on a LAS 4000 imaging system (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Molecular dynamics simulations

MD simulations were conducted using GROMACS version 2020.644. with the all-atom Fuji force field for proteins, lipids, and ions, and TIP3P water45,46,47. Temperature was maintained at 298 K using a Nosé–Hoover thermostat, and pressure was set at 1 bar using either the semi-isotropic Berendsen barostat or the Parrinello-Rahman barostat48,49,50,51. Electrostatic interactions were calculated with the particle mesh Ewald method, employing a real-space cut-off of 1.0 nm, while Lennard-Jones interactions were computed using the Lennard-Jones particle mesh Ewald method with geometric approximation for combination rules in reciprocal space52,53. The Verlet cut-off scheme was applied for the neighbor list, and the linear constraint solver algorithm with an order of 6 was used to constrain all bonds54. A virtual site model was implemented to remove bond-angle degrees of freedom in hydrogen atoms.

The initial coordinates for NhaA were taken from the x-ray crystal structure (PDB ID: 4AU5)55. A cardiolipin molecule, with or without a cyclopropane ring, was positioned at the NhaA dimer interface and optimized using the CDOCKER tool in Discovery Studio 2020. The lipid composition of the model membrane was based on experimental fatty acid composition ratios and the known proportions of phospholipid head groups in E. coli1, with a PE:PG:CL ratio of 81.2:14.6:4.2 in both systems. The E. coli model membrane for the WT strain comprised six lipid types: 1134 molecules of PMPE (1-palmitoyl-2-cis-9,10-methylene-hexadecanoic-acid-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine), 288 molecules of PMPG (1-palmitoyl-2-cis-9,10-methylene-hexadecanoic-acid-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol), 72 molecules of PVPE (1-palmitoyl-2-vacenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine), 108 molecules of HYPE (1-palmitoleoyl-2-cis-11,12-methylene-hexadecanoic-acid-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine), 180 molecules of PMHPE (1-palmitoyl-2-cis-11,12-methylene-hexadecanoic-acid-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine), and 72 molecules of cardiolipin (CDLP) [1-(1-palmitoyl-2-cis-9,10-methylene-hexadecanoic-acid-sn-3-phosphatidyl)-3-(1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-3-phosphatidyl)-sn-glycerol]. For the Δcfa model membrane, five lipid types were included: 1042 molecules of PYPE (1-palmitoyl-2-palmitoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine), 136 molecules of PYPG (1-palmitoyl-2-palmitoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylglycerol), 358 molecules of PVPE (1-palmitoyl-2-vacenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine), 134 molecules of PVPG (1-palmitoyl-2-vacenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylglycerol), and 70 molecules of cardiolipin without a cyclopropane ring (CDLd) [1,3-bis(1-palmitoyl-2-palmitoleoyl-sn-3-phosphatidyl)-sn-glycerol]. The lipid bilayers were prepared using the Memgen program56.

Using the LAMBADA program, proteins were embedded into the well-equilibrated E. coli and Δcfa model membranes obtained from 1 μs MD simulations57. Overlapping lipids, defined as those with heavy atoms within 0.12 nm of the protein’s heavy atoms, were removed. System energy minimized using alternating steepest-descent and conjugate gradient methods, followed by equilibration in an isothermal-isobaric ensemble. In this equilibration, a semi-isotropic Berendsen barostat was used, applying position restraints only to the protein’s heavy atoms (leaving lipid heavy atoms unrestrained) for 30 ns with a 2 fs time step. Subsequently, unconstrained simulations were run for an additional 20 ns using the semi-isotropic Berendsen barostat with a 4 fs time step.

Starting from these equilibrated structures, two unconstrained 400 ns simulations were conducted with distinct initial velocities corresponding to a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at 298 K, using a semi-isotropic Parrinello-Rahman barostat and a 4 fs time step. Well-equilibrated trajectories from the final 100 ns (300–400 ns) were selected for analysis. Interaction energies and the radius of gyration, focusing on the five hydrophobic cytoplasmic gate residues (Val75, Ile134, Met157, Ala160, and Ile161), were calculated using GROMACS tools gmx energy and gmx grate, respectively. The bending angles of TM5 helices were determined by measuring the deviation from linearity of the angle formed by the Cα atoms of Leu152, Asp163, and Phe174 with the gmx angle tool.

The acyl chain order parameter, SCD, was calculated as:

where θ represents the angle between the bilayer normal (z-axis) and the C–H bond vector, and 〈···〉 denotes the ensemble average over the simulation trajectory used for analysis. The average area per lipid for both membrane systems was computed using the APL@Voro software58.

Thin-layer chromatography of total lipids and quantification of phospholipids

The lipids used in the TLC analysis were extracted following the modified methods described in reference59. Harvested pellets (200 OD600 × volume (mL)) were dissolved in 400 µL of BUME solution (1-butanol:methanol = 3:1(v/v)). The suspensions were transferred to a 2 mL screw-cap tube, and an appropriate amount of 0.5 mm zirconia balls was added. Subsequently, cells were crushed using a FastPrep-24 5G (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) at 6 m/s for 30 s, repeated three times. After standing for 5 min at room temperature, 400 µL of a heptane-ethyl acetate solution (heptane:ethyl acetate = 3:1 (v/v)) was added, and the mixture was homogenized using a vortex mixer for 2 min. After standing for 5 min at room temperature, 400 µL of 1% acetic acid was added, and the mixture was homogenized using a vortex mixer for 2 min. After standing for 5 min at room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min, and the upper layer was collected. Next, 400 µL of heptane-ethyl acetate solution was added to the remaining lower layer, and the solution was homogenized using a vortex mixer for 2 min. After standing for 5 min at room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min, and the upper layer of the supernatant was collected. The extraction step employing a heptane-ethyl acetate mixture was repeated. The upper layers that were obtained were evaporated and used as extracted lipids. These lipid samples were dissolved in 200 µL of methanol.

TLC analysis for phospholipids was conducted following the methods described in a reference60. TLC plates (20 cm × 20 cm, Silica gel 60) were immersed in 2.3% boric acid in ethanol, dried, and activated at 160°C for 30 min. Lipid samples (equivalent to 20 OD600 × volume (mL)), 100 µg of 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (DOPS) (840035; Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL), 100 µg of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE) (850757; Avanti Polar Lipids), 100 µg of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1’-rac-glycerol) (POPG) (840457; Avanti Polar Lipids), 100 µg of 1’,3’-bis[1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho]-glycerol (18:1 CL) (710335; Avanti Polar Lipids) were applied to the TLC plates and the plates were developed with chloroform/ethanol/triethylamine/water (30/35/35/7). The plates were dried and immersed (the dried and developed plates) in 0.01% primuline in 80%(v/v) acetone, after which the plates were visualized under ultraviolet illumination at 365 nm. The spots corresponding to phospholipids were scraped from the TLC plates. Phosphorus assay was performed for each of the phospholipid species according to the method of Bartlett61.

Statistics and reproducibility

All experiments were independently repeated at least three times with similar results. The number of biological replicates (n) is indicated in each figure legend. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise stated. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel. Statistical significance was assessed using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. All MD simulations were performed in duplicate for both the NhaA-WT and NhaA-Δcfa systems, starting from independent initial configurations. Because NhaA forms a homodimer, analyses were conducted separately for each protomer in each trajectory, yielding a total of four independent data points (n = 4) for all quantitative analyses, including interaction energy and other measurements. Mean values and standard errors were calculated from these four independent measurements. No data were excluded from the analyses.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Uncropped scans of Western blots and TLC plates are provided in Supplementary Information. Numerical source data for the graphs in the manuscript are available in Supplementary Data 2. Additional data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.

References

Cronan, J. E. & Vagelos, P. R. Metabolism and function of the membrane phospholipids of Escherichia coli. BBA - Rev. Biomembr. 265, 25–60 (1972).

Ryabichko, S. et al. Cardiolipin is required in vivo for the stability of bacterial translocon and optimal membrane protein translocation and insertion. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–13 (2020).

Bogdanov, M., Heacock, P., Guan, Z. & Dowhan, W. Plasticity of lipid-protein interactions in the function and topogenesis of the membrane protein lactose permease from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa. 107, 15057–15062 (2010).

Rodrigo, R., Miranda-Merchak, A., Grau, R. V., Bachler, J. P. & Vergara, L. Modulation of (Na,K)-ATPase activity by membrane fatty acid composition: Therapeutic implications in human hypertension. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 36, 17–26 (2014).

Vitrac, H., Bogdanov, M. & Dowhan, W. Proper fatty acid composition rather than an ionizable lipid amine is required for full transport function of lactose permease from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 5873–5885 (2013).

Mavis, R. D. & Vagelos, P. R. The effect of phospholipid fatty acid composition in membranous enzymes in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 247, 652–659 (1972).

Grogan, D. W. & Cronan, J. E. Cyclopropane ring formation in membrane lipids of bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61, 429–441 (1997).

Karlinsey, J. E. et al. Cyclopropane fatty acids are important for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium virulence. Infect. Immun. 90, 1–13 (2022).

Hu, W. et al. Improving acid resistance of Escherichia coli base on the CfaS-mediated membrane engineering strategy derived from extreme acidophile. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1–13 (2023).

Taylor, F. R. & Cronan, J. E. Cyclopropane fatty acid synthase of Escherichia coli. Stabilization, purification, and interaction with phospholipid vesicles. Biochemistry 18, 3292–3300 (1979).

Wang, A. Y., Cronan, J. E. & Grogan, D. W. Cyclopropane fatty acid synthase of Escherichia coli:. Deduced amino acid sequence, purification, and studies of the enzyme active site. Biochemistry 31, 11020–11028 (1992).

Grandvalet, C. et al. Changes in membrane lipid composition in ethanol- and acid-adapted Oenococcus oeni cells: Characterization of the cfa gene by heterologous complementation. Microbiology 154, 2611–2619 (2008).

Teixeira, H., Gonçalves, M. G., Rozès, N., Ramos, A. & San Romão, M. V. Lactobacillic acid accumulation in the plasma membrane of Oenococcus oeni: A response to ethanol stress? Microb. Ecol. 43, 146–153 (2002).

Asakura, H. et al. Membrane topology of Salmonella invasion protein SipB confers osmotolerance. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 426, 654–658 (2012).

Guillot, A., Obis, D. & Mistou, M. Y. Fatty acid membrane composition and activation of glycine-betaine transport in Lactococcus lactis subjected to osmotic stress. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 55, 47–51 (2000).

Brown, J. L., Ross, T., McMeekin, T. A. & Nichols, P. D. Acid habituation of Escherichia coli and the potential role of cyclopropane fatty acids in low pH tolerance. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 37, 163–173 (1997).

Chang, Y. Y. & Cronan, J. E. Membrane cyclopropane fatty acid content is a major factor in acid resistance of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 33, 249–259 (1999).

Grogan, D. W. & Cronan, J. E. Characterization of Escherichia coli mutants completely defective in synthesis of cyclopropane fatty acids. J. Bacteriol. 166, 872–877 (1986).

Zavaglia, A. G., Disalvo, E. A. & De Antoni, G. L. Fatty acid composition and freeze-thaw resistance in lactobacilli. J. Dairy Res. 67, 241–247 (2000).

Padan, E. Functional and structural dynamics of NhaA, a prototype for Na+ and H+ antiporters, which are responsible for Na+ and H+ homeostasis in cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 1837, 1047–1062 (2014).

Ohyama, T., Igarashi, K. & Kobayashi, H. Physiological role of the chaA gene in sodium and calcium circulations at a high pH in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176, 4311–4315 (1994).

Padan, E., Maisler, N., Taglicht, D., Karpel, R. & Schuldiner, S. Deletion of ant in Escherichia coli reveals its function in adaptation to high salinity and an alternative Na+/H+ antiporter system(s). J. Biol. Chem. 264, 20297–20302 (1989).

Pinner, E., Kotler, Y., Padan, E. & Schuldiner, S. Physiological role of NhaB, a specific Na+/H+ antiporter in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 1729–1734 (1993).

Landreh, M. et al. Integrating mass spectrometry with MD simulations reveals the role of lipids in Na+/H+ antiporters. Nat. Commun. 8, (2017).

Rimon, A., Mondal, R., Friedler, A. & Padan, E. Cardiolipin is an optimal phospholipid for the assembly, stability, and proper functionality of the dimeric form of NhaA Na+/H+ antiporter. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–11 (2019).

Chen, Y. Y. & Gänzle, M. G. Influence of cyclopropane fatty acids on heat, high pressure, acid and oxidative resistance in Escherichia coli. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 222, 16–22 (2016).

Zhang, Y. M., Marrakchi, H. & Rock, C. O. The FabR (YijC) transcription factor regulates unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15558–15565 (2002).

Huang, Y., Chen, W., Dotson, D. L., Beckstein, O. & Shen, J. Mechanism of pH-dependent activation of the sodium-proton antiporter NhaA. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–10 (2016).

Gadsby, D. C. Ion channels versus ion pumps: The principal difference, in principle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 344–352 (2009).

Saito, S. et al. N -myristoylation and S -acylation are common modifications of Ca 2+ -regulated Arabidopsis kinases and are required for activation of the SLAC1 anion channel. N. Phytol. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15053 (2018).

Oepen, K. et al. Myristic acid inhibits the activity of the bacterial ABC transporter BmrA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (2021).

Börjesson, S. I., Hammarström, S. & Elinder, F. Lipoelectric modification of ion channel voltage gating by polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biophys. J. 95, 2242–2253 (2008).

Villanueva, C. E. & Hagenbuch, B. Palmitoylation of solute carriers. Biochem. Pharmacol. 215, 115695 (2023).

Mejía, R., Gómez-Eichelmann, M. C. & Fernández, M. S. Escherichia coli membrane fluidity as detected by excimerization of dipyrenylpropane: Sensitivity to the bacterial fatty acid profile. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 368, 156–160 (1999).

Poger, D. & Mark, A. E. A ring to rule them all: The effect of cyclopropane fatty acids on the fluidity of lipid bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 5487–5495 (2015).

Loffhagen, N., Härtig, C., Geyer, W., Voyevoda, M. & Harms, H. Competition between cis, trans and cyclopropane fatty acid formation and its impact on membrane fluidity. Eng. Life Sci. 7, 67–74 (2007).

Williams, K. A., Geldmacher-Kaufer, U., Padan, E., Schuldiner, S. & Kühlbrandt, W. Projection structure of NhaA, a secondary transporter from Escherichia coli, at 4.0 Å resolution. EMBO J. 18, 3558–3563 (1999).

Gerchman, Y., Rimon, A., Venturi, M. & Padan, E. Oligomerization of NhaA, the Na+/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli in the membrane and its functional and structural consequences. Biochemistry 40, 3403–3412 (2001).

Dover, N. et al. Na+-induced transcription of nhaA, which encodes an Na+/H+ antiporter in Escherichia coli, is positively regulated by nhaR and affected by hns. J. Bacteriol. 178, 6508–6517 (1996).

Mizoguchi, H., Tanaka-Masuda, K. & Mori, H. A simple method for multiple modification of the Escherichia coli K-12 chromosome. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71, 2905–2911 (2007).

Bligh, E. G. & Dyer, W. J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 (1959).

Rosen, B. P. Ion extrusion systems in Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 125, 328–336 (1986).

Goldberg, E. B. et al. Characterization of a Na+/H+ antiporter gene of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84, 2615–2619 (1987).

Abraham, M. J. et al. Gromacs: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1–2, 19–25 (2015).

Fujitani, H., Matsuura, A., Sakai, S., Sato, H. & Tanida, Y. High-level ab initio calculations to improve protein backbone dihedral parameters. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 5, 1155–1165 (2009).

Kamiya, N., Kayanuma, M., Fujitani, H. & Shinoda, K. A New Lipid Force Field (FUJI). J. Chem. Theory Comput. 16, 3641–3653 (2020).

Jorgensen, W. L., Chandrasekhar, J., Buckner, J. K. & Madura, J. D. Computer simulations of organic reactions in solution. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 482, 198–209 (1986).

Nosé, S. A molecular dynamics method for simulations in the canonical ensemble. Mol. Phys. 52, 255–268 (1984).

Hoover, W. G. Canonical dynamics: Equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A 31, 1695–1697 (1985).

Berendsen, H. J. C., Postma, J. P. M., Van Gunsteren, W. F., Dinola, A. & Haak, J. R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3684–3690 (1984).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 7182–7190 (1981).

Darden, T., York, D. & Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N -log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092 (1993).

Wennberg, C. L. et al. Direct-space corrections enable fast and accurate Lorentz-Berthelot combination rule Lennard-Jones lattice summation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 5737–5746 (2015).

Hess, B. P-LINCS: A parallel linear constraint solver for molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 116–122 (2008).

Lee, C. et al. Crystal structure of the sodium-proton antiporter NhaA dimer and new mechanistic insights. J. Gen. Physiol. 144, 529–544 (2014).

Knight, C. J. & Hub, J. S. MemGen: A general web server for the setup of lipid membrane simulation systems. Bioinformatics 31, 2897–2899 (2015).

Schmidt, T. H. & Kandt, C. LAMBADA and InflateGRO2: Efficient membrane alignment and insertion of membrane proteins for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52, 2657–2669 (2012).

Lukat, G., Krüger, J. & Sommer, B. APL@Voro: A Voronoi-based membrane analysis tool for GROMACS Trajectories. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 53, 2908–2925 (2013).

Löfgren, L. et al. The BUME method: A novel automated chloroform-free 96-well total lipid extraction method for blood plasma. J. Lipid Res. 53, 1690–1700 (2012).

Pinault, M. et al. A 1D High Performance Thin Layer Chromatography Method validated to quantify phospholipids including cardiolipin and monolysocardiolipin from biological samples. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 122, 1–12 (2020).

Bartlett, G. R. Phosphorus assay in column chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 234, 466–468 (1959).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a research fund from Kyowa Hakko Bio., and supported in part by grant JP20H05453 (K. S.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and by the MEXT program “Program for Promoting Research on the Supercomputer Fugaku” (Biomolecular Dynamics in a Living Cell) (K. S.). Computations were partially conducted at the Research Center for Computational Science, Okazaki, Japan (Projects: 22-IMS-C089, 23-IMS-C077). This work was also supported by grant 22K05425 (S. H) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI. This work has been supported by a grant-in-aid from IFO, Institute for Fermentation, Osaka, to H. K.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H. experiments, writing manuscript-original draft; S.H. methodology, data analysis, writing manuscript-original draft, project administration; K.S. MD simulations, writing manuscript-original draft; K.N. experiments; R.I. experiments; T.U. experiments, conceptualization, project administration; S.K. methodology; M.N. supervision, funding acquisition; H.K. conceptualization, data analysis, project administration, manuscript-review and editing; T.T. data analysis, project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.N. received research funding from Kyowa Hakko Bio. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Markus Seeger, José Antonio Poveda and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Janesh Kumar and Laura Rodríguez Pérez.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hori, K., Hamamoto, S., Shinoda, K. et al. Regulation of membrane protein activity by cyclopropane fatty acids in Escherichia coli lipid environment. Commun Biol 8, 1852 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09234-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09234-x